Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Extended Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Protocol

2.3. Data Acquisition

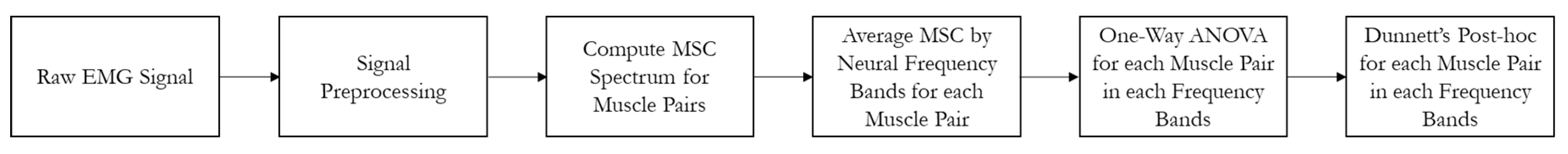

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

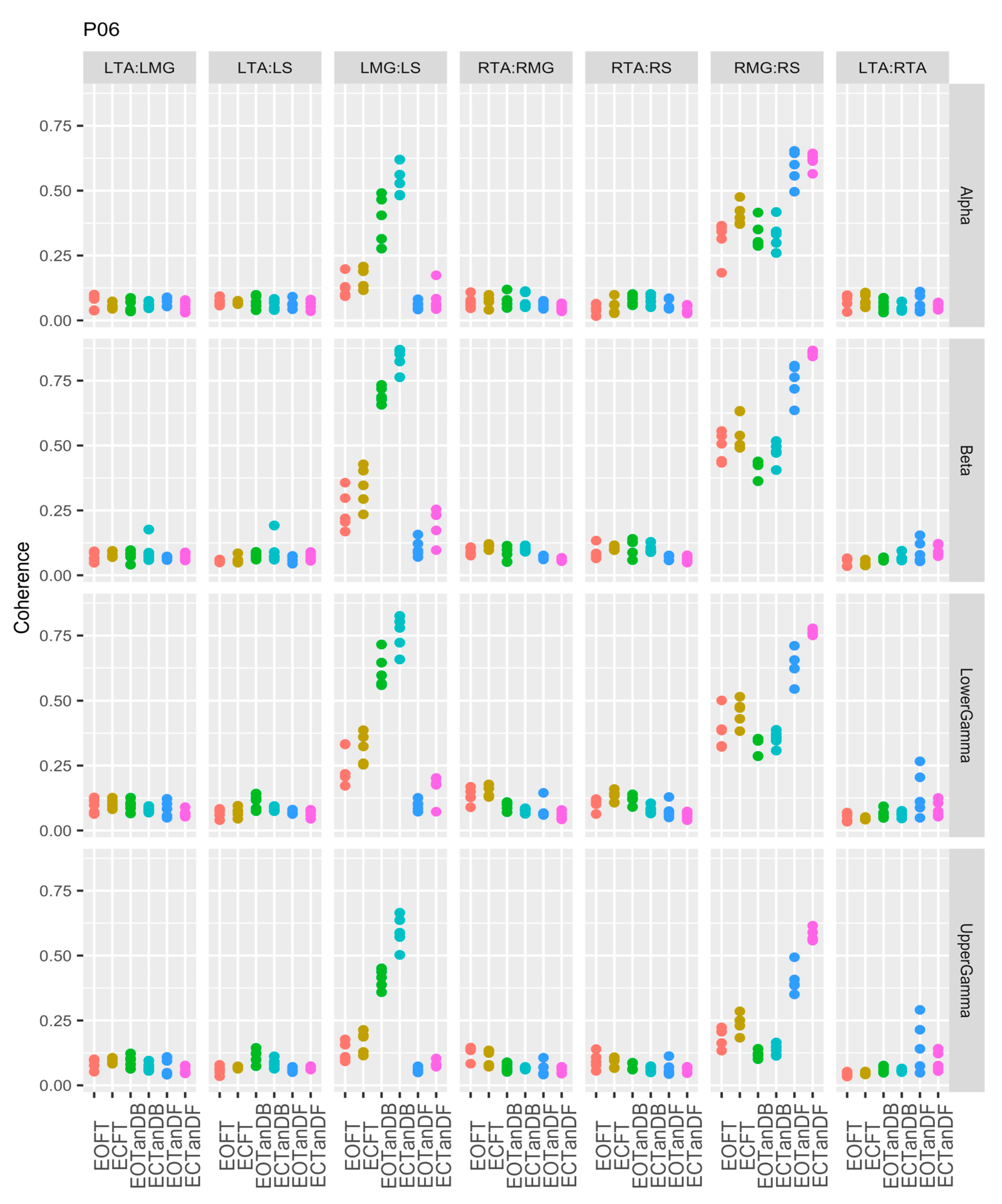

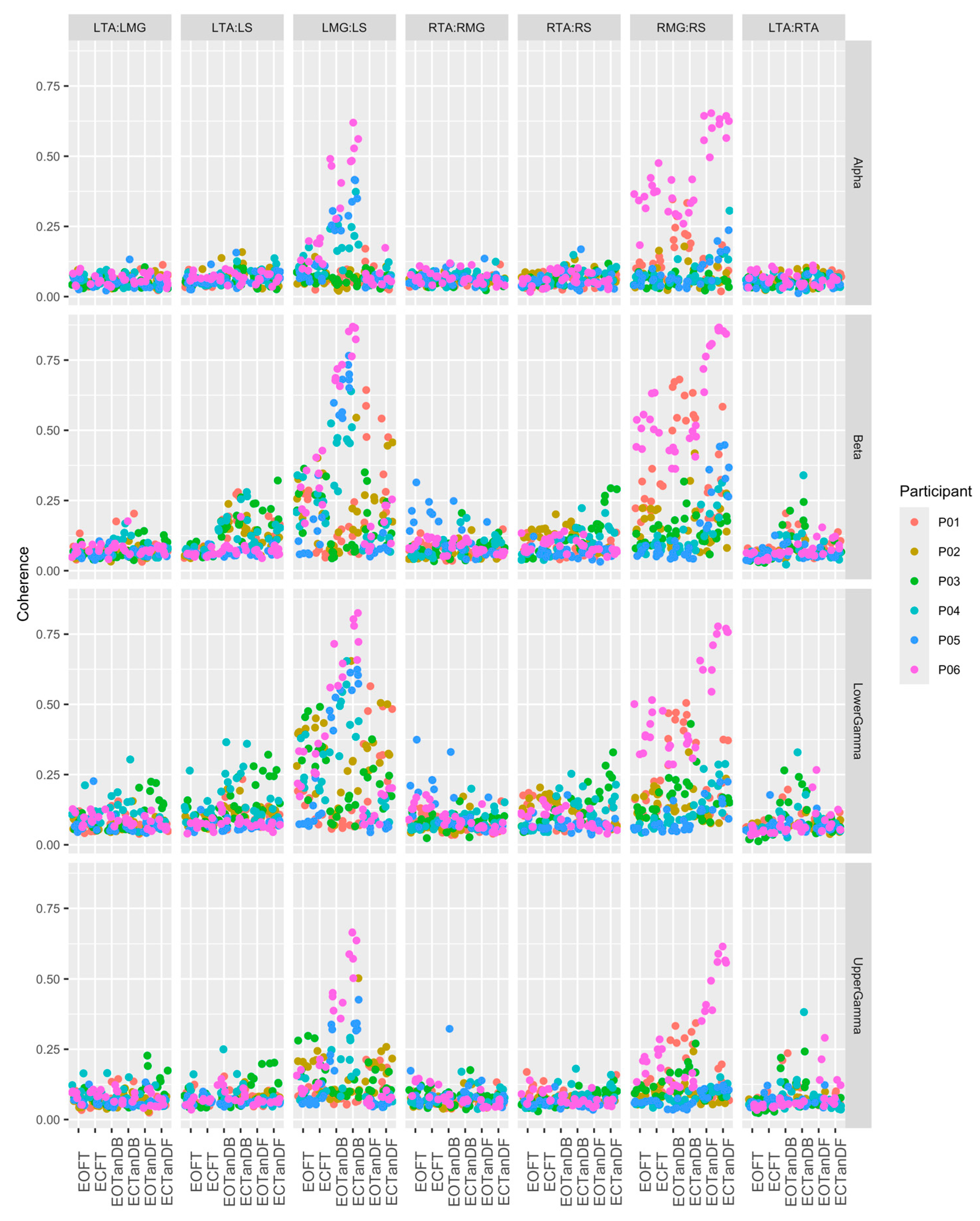

3.1. Overview of EMG-EMG Muscular Coherence Across Participants

- Consistently greater coherence between muscle pairs in the tandem stance postures compared to the feet together stance postures

- Consistently greater coherence in the LMG: LS and RMG: RS muscle pairs across the beta, lower gamma, and upper gamma frequency bands for tandem stance postures in both eyes open and closed conditions, without discernable differences between eyes open and eyes closed

- Demonstrable evidence of coherence between antagonistic muscle pairs, e.g., LTA: LS, primarily in the tandem stance postures.

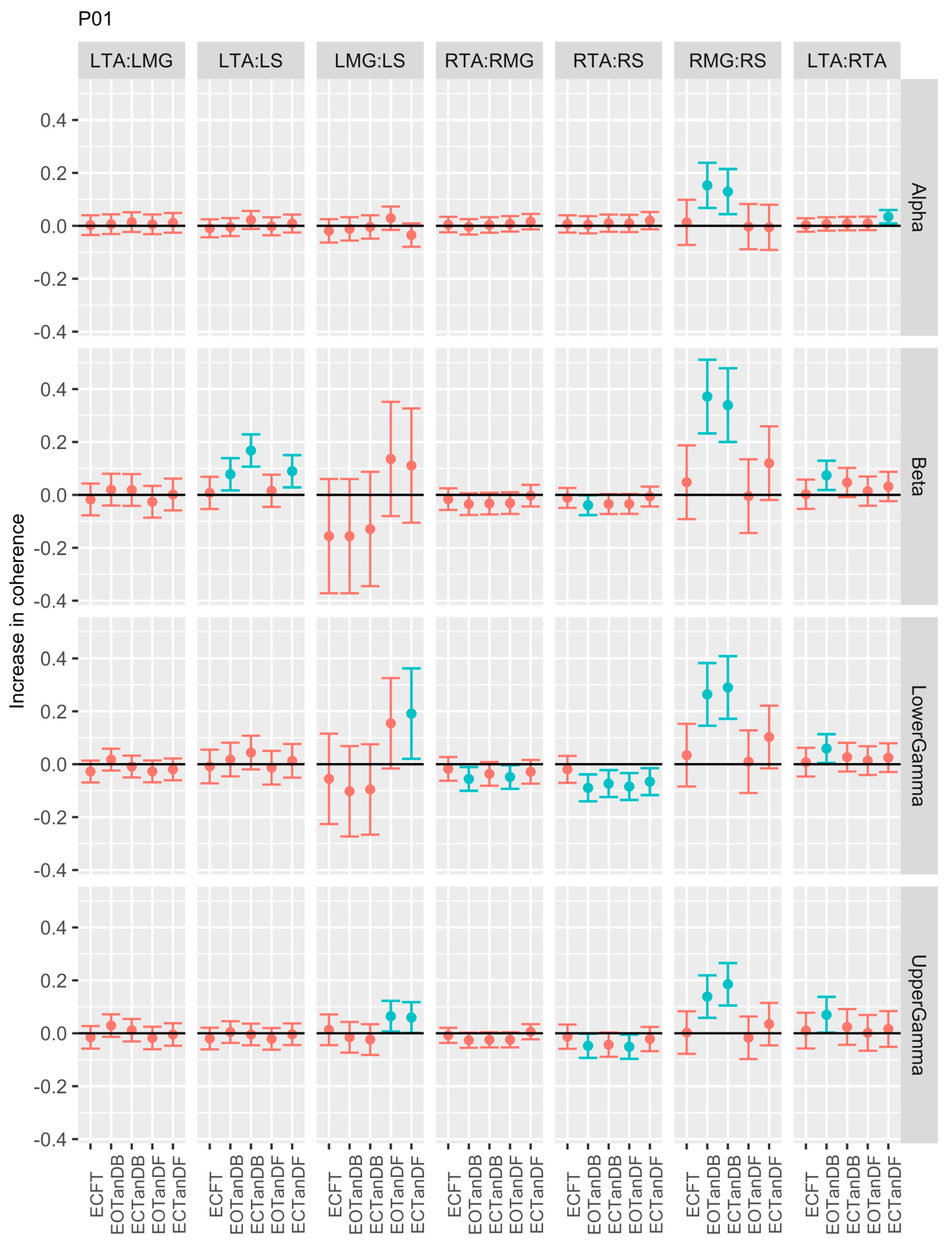

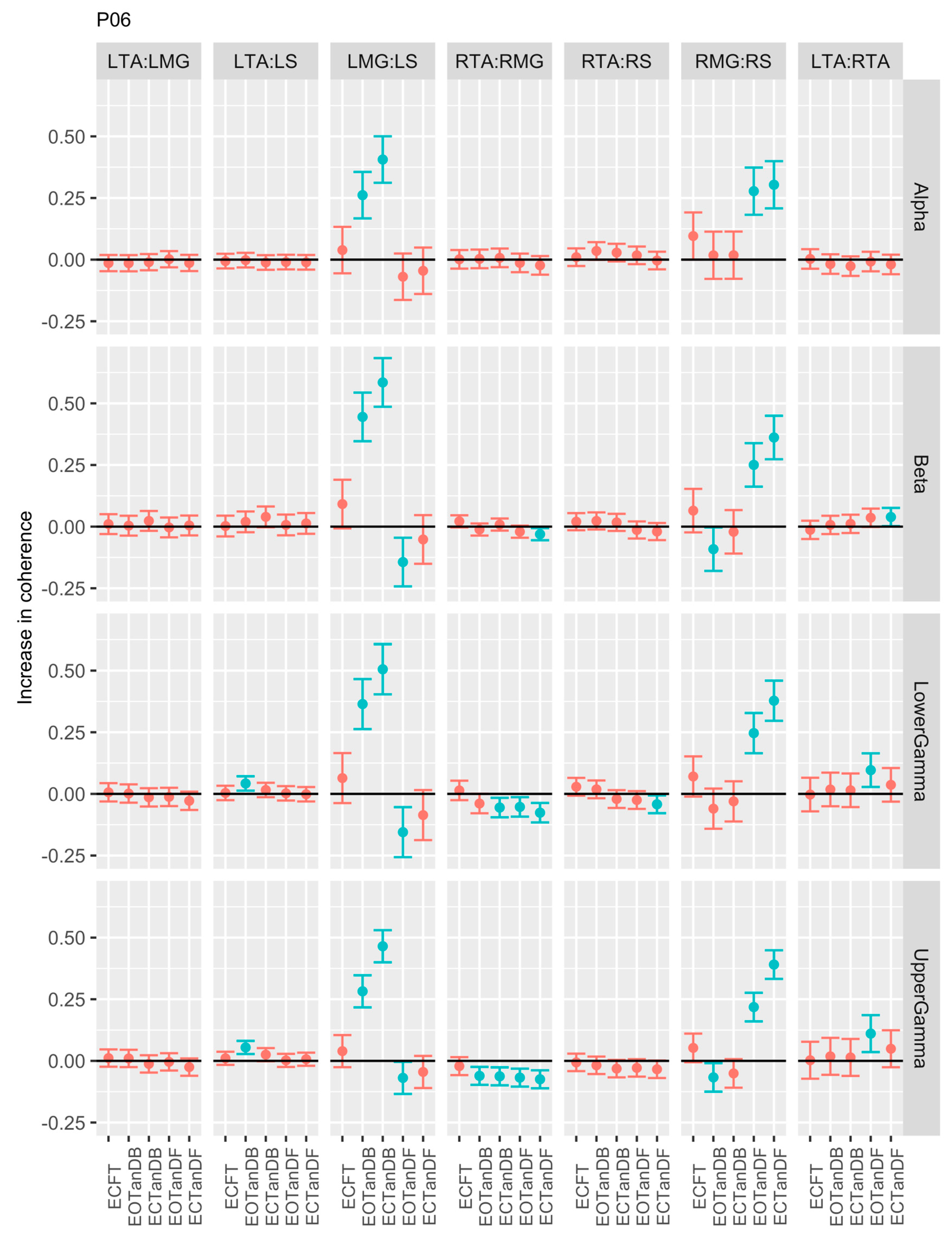

3.2. Comparison of EMG-EMG Muscular Coherence Across Conditions

3.3. Intertrial and Intersubject EMG-EMG Muscular Coherence Variability

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Masui, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; Matsuyama, Y.; Sakano, S.; Kawasaki, M.; Suzuki, S. ; Gender differences in platform measures of balance in rural-dwelling elders. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2005, 41, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman-Liu, D. Age-related changes in the range and velocity of postural sway. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2018, 77, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamont, R.M.; Morris, M.E.; Menz, H.B.; McGinley, J.L.; Brauer, S.G. Falls in people with Parkinson’s disease: a prospective comparison of community and home-based falls. Gait Posture 2017, 55, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazibara, T.; Tepavcevic, D.K.; Svetel, M.; Tomic, A.; Stankovic, I.; Kostic, V.S.; Pekmezovic, T. Near-falls in people with Parkinson’s disease: circumstances, contributing factors and association with falling. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2017, 161, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lima, F.; Melo, G.; Fernandes, D.A.; Santos, G.M.; Neto, F.R. Effects of total knee arthroplasty for primary knee osteoarthritis on postural balance: a systematic review. Gait Posture 2021, 89, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camicioli, R.; Morris, M.E.; Pieruccini-Farina, F.; Montero-Odasso, M.; Son, S.; Buzaglo, D.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Nieuwboer, A. Prevention of falls in Parkinson’s Disease: guidelines and gaps. Move Disord Clin Pract 2023, 10, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerdesteyn, V.; de Niet, M.; van Duijuhoven, H.J.R.; Geurts, A.C.H. Falls in individuals with stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev 2008, 45, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, A.F.; Paul, G.; Hausdorff, J.M. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas 2013, 75, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C.R.; Cooper, C. Sayer, A.A. Prevalence and risk factors for falls in older men and women: the longitudinal study of ageing. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutzouri. M.; Gleeson, N., Billis, E., Tsepis, E., Panoutsopoulou, I., Eds.; Gliatis, J. The effect of total knee arthroplasty on patient’s balance and incidence of falls: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017, 25, 3439–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Darvishi, N.; Ahmadipanah, M.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global prevalence of falls in older adults: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2022, 17, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporns, O.; Chialvo, D.R.; Kaiser, M.; Hilgetag, C.C. Organization, development and function of complex brain networks. Trends Cogn Sci 2004, 8, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berstein, N. The Coordination and Regulation of Movements, 1st ed., Pergamon Press Ltd, Oxford, UK, 1967.

- Wang, Z.; Ko, J.H.; Challis, J.H.; Newell, K.M. The degrees of freedom problem in human standing posture: collective and component dynamics. PloS One 2014, 9, e85414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruton, M. O’Dwyer, N. Synergies in coordination: a comprehensive overview of neural, computational, and behavioral approaches. J Neurophsyiol 2018, 120, 2761–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latash, M.L.; Scholz, J.P.; Schöner, G. Motor control strategies revealed in the structure of motor variability. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2002, 30, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latash, M.L. The bliss (not the problem) of motor abundance (not redundancy). Exp Brain Res 2012, 217, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latash, M.L. Motor synergies and the equilibrium-point hypothesis. Mot Contr 2020, 14, 294–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, V.; Goodman, S.; Zatsiorsky, V. Latash, M.L. Muscle synergies during shifts of the center of pressure by standing persons: identification of muscle modes. Biol Cybern 2003, 89, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, V.; Latash, M.L.; Scholz, J.P.; Zatsiorsky, V.M. Muscle synergies during shifts of the center of pressure by standing persons. Exp Brain Res 2003, 152, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Oviedo, G. and Ting, L.H. Muscle synergies characterizing human postural responses. J Neurophysiol 2007, 98, 2144–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, T.W.; Danna-Dos-Santos, A.; Xie, H.; Roerdink, M.; Stins, J.F.; Breakspear, M. Muscle networks: connectivity analysis of EMG activity during postural control. Sci Rep 2016, 5, 17830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, H.; Fujii, K.; Kouzaki, M. Intermittent muscle activity in the feedback loop of postural control system during natural quiet standing. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 10631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, L.H. and McKay, J.L. Neuromechanics of muscle synergies for posture and movement. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2007, 17, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, C.J.; Erim, Z. Common drive in motor units of a synergistic muscle pair. J Neurophysiol 2002, 87, 2200–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosse, P.; Cassidy, M.J.; Brown, P. EEG-EMG, MEG-EMG and EMG-EMG frequency analysis: physiological principles and clinical applications. Clin Neurophysiol 2002, 113, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, S.F.; Halliday, D.M.; Conway, B.A.; Stephens, J.A.; Rosenburg, J.R. A review of recent applications of cross-correlation methodologies to human motor unit recording. J Neurosi Methods 1997, 74, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.G. Rhythmicity, synchronization and binding in human and primate motor systems. J Physiol 1998, 509 (Pt 1) Pt 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzi, E.; Cheung, V.C.K. The neural origin of muscle synergies. Front Comput Neurosci 2013, 7–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, T.W. The potential of corticomuscular and intermuscular coherence for research on human motor control. Front Hum Neurosci 2013, 7–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, C.M. and Valero-Cuevas, F.J. Intermuscular coherence reflects functional coordination. J Neurophysiol 2017, 118, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkman, J.N.; Daffertshofer, A.; Gollo, L.L.; Breakshpear, M.; Boonstra, T.W. ; Network structure of the human musculoskeletal system shapes neural interactions on multiple time scales. Sci Adv 2018, 4, eaat0497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, G.; Semmler, J.G.; Ivanova, T.D.; Garland, S.J. Low-frequency common modulation of soleus motor unit discharge is enhanced during postural control in humans. Exp Brain Res 2006, 175, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki, G.; Ivanova, T.D.; Garland, S.J. Factors affecting the common modulation of bilateral motor unit discharge in human soleus muscles. J Neurophysiol 2007, 97, 3917–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, H.; Fujii, K, .; Kouzaki, M. Joint coordination and muscle activities of ballet dancers during tiptoe standing. Motor Control 2017, 21, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenville, R.; Maudrich, T.; Vidaurre, C.; Maudrich, D.; Villringer, A.; Ragert, P.; et al. Intermuscular coherence between homologous muscles during dynamic and static movement periods of bipedal squatting. J Neurophsiol 2020, 124, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hug, F.; Del Vecchio, A.; Avrillon, S.; Farina, D.; Tucker, K. Muscles from the same muscle group do not necessarily share common drive: evidence from the human triceps surae. J Appl Physiol 2021, 130, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formaggio, E.; Masiero, S. Volpe, D.; Demertzis, E.; Gallo, L.; Del Felice, A. Lack of inter-muscular coherence as axial muscles in Pisa Syndrome. Neurol Sci 2019, 40, 1465–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, D.A.; Prince, F.; Stergiou, P.; Powell, C. Medial-lateral and anterior-posterior responses associated with centre of pressure changes in quiet standing. Neursci Res Comm 1993, 12, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, D. Human balance and posture control during standing and walking. Gait Posture 1995, 3, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A.; Prince, G.; Frank, J.S.; Powell, C.; Zabjek, K.F. Unified theory regarding A/P and M/L balance in quiet stance. J Neurophysiol 1996, 75, 2334–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A.; Patla, A.E.; Prince, F.; Ishac, M.; Krystyna, G.-P. Stiffness control of balance in quiet standing. J Neurophysiol 1998, 80, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, D.A.; Patla, A.E.; Ishac, M.; Gage, W.H. Motor mechanisms of balance during quiet standing. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2003, 13, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.S.; Durward, B.R.; Rowe, P.J.; Paul, J.P. What is balance? Clin Rehabil 2000, 14, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanenko, Y.; Gurfinkel, V.S. Human postural control. Front Neurosci 2018, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, F.B. Postural orientation and equilibrium: what do we need to know about neural control of balance to prevent falls. Age Aging 2006, 35 (Suppl. S2), ii7–ii11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M.G.; Murnaghan, C.D.; Inglis, J.T. Shifting the balance: evidence of an exploratory role for postural sway. Neurosci 2010, 171, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, T.W.; Roerdink. M.; Daffertshofer, A.; van Vugt, B.; van Werven, G.; Beek, P.J. Low-alcohol doses reduce common 10- to 15-Hz input to bilateral leg muscles during quiet standing. J Neurophysiol 2008, 100, 2158–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danna-Dos-Santos, A.; Degani, A.M.; Boonstra, T.W.; Mochizuki, L.; Harney, A.M.; Schmeckpeper, M.M.; Tabor, L.C.; Leonard, C.T. The influence of visual information on multi-muscle control during quiet stance: a spectral analysis approach. Exp Brain Res 2015, 233, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojima, I.; Suwa, Y.; Sugiura, H.; Noguchi, T.; Tanabe, S.; Mima, T.; Watanabe, T. Smaller muscle mass is associated with increase in EMG-EMG coherence of the leg muscle during unipedal stance in elderly adults. Hum Mov Sci 2020, 71, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnica, M.J.; Weaver, T.B.; Prentice, S.D.; Laing, A.C. The influence of ankle muscle activation on postural sway during quiet stance. Gait Posture 2014, 39, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loram, I.D.; Lakie, M. Direct measurement of human ankle stiffness during quiet standing: intrinsic mechanical stiffness is insufficient for stability. J Physiol 2002, 545, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlutters, M.; Boonstra, T.A.; Scouten, A.C.; van der Kooij, H. Direct measurement of the intrinsic ankle stiffness during standing. J Biomech 2015, 48, 1258–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramake, Y.; Nozaki, D.; Masani, K.; Sato, T.; Nakazawa, K.; Yano, H. Reciprocal angular acceleration of the ankle and hip joints during quiet standing in humans. Exp Brain Res 2001, 136, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creath, R.; Kiemel, T.; Horak, F.; Peterka, R.; Jeka, J. A unified view of quiet and perturbed stance: simultaneous co-existing excitable modes. Neurosci Lett 2005, 377, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kiemel, T.; Jeka, J. The influence of sensory information on two-component coordination during quiet stance. Gait Posture 2007, 26, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinter, H.J.; van Swigchem, R.; van Soest, A.J.K.; Rozendaal, A. The dynamics of postural sway cannot be captured using a one-segment inverted pendulum model: a PCA on segment rotations during unperturbed stance. J Neuophysiol 2008, 100, 3197–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, M.; Grimmer, S.; Siebert, T.; Blickhan, R. All joints contribute to quiet stance: a mechanical analysis. J Biomech 2009, 42, 2739–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasagawa, S.; Ushiyama, J.; Kouzaki, M.; Kanehisa, H. Effect of hip motion on the body kinematics in the sagittal plane during human quiet standing. Neurosci Lett 2009, 450, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nomura, T.; Casadio, M.; Morasso, P. Intermittent control with ankle, hip, and mixed strategies during quiet standing: a theoretical proposal based on a double inverted pendulum model. J Theor Biol 2012, 310, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasagawa, S.; Shinya, M.; Nakazawa, K. Interjoint dynamic interaction during constrained human quiet standing by induced acceleration analysis. J Neurophysiol 2014, 111, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Sasagawa, S.; Oba, N.; Nakazawa, K. Behavioral effect of knee joint motion on body’s center of mass during human quiet standing. Gait Posture 2015, 41, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morasso, P.; Cherif, A.; Zenzeri, J. Quiet standing: the single inverted pendulum model is not so bad after all. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0213870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Smith, C.E.; Suzuki, Y.; Kiyono, K.; Tanahashi, T.; Sakoda, S.; Morasso, P.; Nomura, T. Universal and individual characteristics of posture sway during quiet standing in healthy young adults. Physiol Rep 2015, 3, 2015–e12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffer, M.; Kiemel, T.; Jeka, J. Coherence analysis of muscle activity during quiet stance. Exp Brain Res 2008, 185, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, S.R.; Rogers, M.W.; Howland, A.; Fitzpatrick, R. Lateral stability, sensorimotor function and falls in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999, 47, 1077–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, E.; Seiger, Å.; Hirschfeld, H. Postural steadiness and weight distribution during tandem stance in healthy young and elderly adults. Clin Biomech 2005, 20, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R.F. The ability to voluntarily control sway reflects the difficulty of the task. Gait Posture 2010, 31, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozzi, S.; Monti, A.; De Nunzio, A.M.; Do, M.-H.; Schieppati, M. Sensori-motor integration during stance: time adaptation of control mechanisms on adding or removing vision. Hum Mov Sci 2011, 30, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozzi, S.; Do, M.C.; Monti, A.; Schieppati, A.M. Sensorimotor integration during stance: processing time of active or passive addition or withdrawal of vision or haptic information. Neurosci 2012, 212, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozzi, S.; Honeine, J.-L.; Do, M.-C.; Schieppati, M. Leg muscle activity during tandem stance and the control of body balance in the frontal plane. Clin Neurophsiol 2013, 124, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Newell, K.W. Phase synchronization of foot dynamics in quiet standing. Neurosci Lett 2012, 507, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jordan, K.; Newell, K.M. Coordination patterns of foot dynamics in the control of upright standing. Motor Control 2012, 16, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Molenaar, P.M.C.; Newell, K.M. The effect of foot position and orientation on the inter- and intro-foot coordination in standing postures: a frequency domain PCA analysis. Exp Brain Res 2013, 230, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, D.; Negro, F.; Dideriksen, J.L. The effective neural drive to muscles is the common synaptic input to motor neurons. J Physiol 2014, 592 Pt 16, 3427–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, D.; Merletti, R.; Enoka, R.M. The extraction of neural strategies from the surface EMG: an update. J Appl Physiol 2014, 117, 1215–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanake, E.; Horiuchi, Y.; Nojima, I. EMG-EMG coherence during voluntary control of human standing tasks: a systematic scoping review. Front Neurosci 2023, 17, 1145751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, T.W.; Daffertshofer, A.; Roerdink, M.; Flipse, I.; Groenewoud, K.; Beek, P.J. Bilateral motor unit synchronization of leg muscles during a simple dynamic balance task. Eur J Neurosci 2009, 29, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danna-Dos-Santos, A.; Boonstra, T.W.; Degani, A.M.; Cardoso, V.S.; Magalhaes, T.; Mochizuki, L.; Leonard, C.T. Multi-muscle control during bipedal stance: an EMG-EMG analysis approach. Exp Brain Res 2014, 232, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obata, H. Abe, M.O.; Masani, K.; Nakazawa, K. Modulation between bilateral legs and within unilateral muscle synergists of postural muscle activity changes with development and aging. Exp Brain Res 2014, 232, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Massó, X.; Pellicer-Chenoll, M.; Gonzalez, L.M.; Toca-Herrera, J.L. The difficulty of the postural control task affects multi-muscle control during quiet standing. Exp Brain Res 2016, 234, 1977–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noé, F.; García-Massó, X.; Paillard, T. Inter-joint coordination of posture on a seesaw device. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2017, 34, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, T.; Hortobagyi, T.; van Keeken, H.G.; Salem, G.J.; Lamoth, C.J.C. Standing task difficulty related increase in agonist-agonist and agonist-antagonist common inputs are driven by corticospinal and subcortical inputs respectively. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Saito, K.; Ishida, K.; Tanabe, S.; Nojima, I. Fatigue-induced decline in low-frequency common input to bilateral and unilateral plantar flexors during quiet standing. Neurosci Lett 2018, 686, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, S.M.; Wildman, L.; Brummitt, C.; Ratchford, K.; Westbrook, G.M.; Aron, A. Effects of global postural alignment on posture-stabilizing synergy and intermuscular coherence in bipedal standing. Exp Brain Res 2022, 240, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.; Alderink, G.; Rhodes, S. Coherence between electromyographic (EMG) signals of anterior tibialis, soleus, and gastrocnemius during standing balance tasks. Front Hum Neurosci 2023, 17–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiouri, C.; Amiridis, I.G.; Kannas, T.; Varvariotis, N.; Sahinis, C.; Hazitaki, V.; Enoka, R.M. EMG coherence of foot and ankle muscles increases with a postural challenge in men. Gait Posture 2024, 113, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, M.M.; Myers, L.J.; Erim, Z. Coherence between motor unit discharges in response to shared neural inputs. J Neurosci Methods 2007, 163, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degani, A.M.; Leonard, C.T.; Danna-Dos-Santos, A. The use of intermuscular coherence analysis as a novel approach to detect age-related changes on postural synergy. Neurosci Lett 2017, 656, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degani, A.M.; Leonard, C.T.; Danna-Dos-Santos, A. The effects of aging on the distribution and strength of correlated neural inputs to postural muscles during unperturbed bipedal stance. Exp Brain Res 2020, 238, 1537–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Saito, K.; Ishida, K.; Tanabe, S.; Nojima, I. Coordination of plantar flexor muscles during bipedal and unipedal stances in young and elderly adults. Exp Brain Res 2018, 236, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Saito, K.; Ishida, K.; Tanabe, S.; Nojima, I. Age-related declines in the ability to modulate common input to bilateral and unilateral plantar flexors during forward postural lean. Front Hum Neurosci 12, 254. [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.; Piitulainen, H.; Manlangit, T.; Avela, J.; Baker, S.N. Older adults show elevated intermuscular coherence in eyes-open standing but only young adults increase coherence in response to closing the eyes. Exp Physiol 2020, 105, 1000–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minamisawa, T.; Chiba, N.; Suzuki, E. ; Intra- and intermuscular coherence and body acceleration control in older adults during bipedal stance. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotto, A.O. Anatomical guide for the electromyographer, 3rd ed.; Charles C. Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2011; pp. 154–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2000, 10, 361–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team (2024), R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. Htttps://www.R-project.org. (accessed 10 June 2024).

- Posit Team (2024), RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R.Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA. https://www.posit.co/. (accessed 10 June 2024). 10 June.

- Profeta, V.L.; Turvey, M.T. Bernstein’s levels of movement construction: a contemporary perspective. Hum Mov Sci 2018, 57, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, J.P.; Schöner, G. The uncontrolled manifold concept: identifying control variables for a functional task. Exp Brain Res 1999, 126, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, T.W.; Breakspear, M. Neural mechanisms of intermuscular coherence implications for the rectification of surface electromyography. J Neurophysiol 2011, 107, 796–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmler, J.G. Motor unit synchronization and neuromuscular performance. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2002, 30, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, T.; Fisher, B.E.; Hortobágyi, T.; Salem, G.J. Increasing mediolateral standing sway is associated with increasing corticospinal excitability, and decreasing M1 inhibition and facilitation. Gait Posture 2018, 60, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, N.; Alderink, G.; Rhodes, S. Approximate entropy and velocity of center of pressure to determine postural stability: a pilot study. Appl Sci 2023, 13, 9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Oviedo, G.; Ting, L.H. Subject-specific muscle synergies in human balance control are consistent across different biomechanical contexts. J Neurophysiol 2010, 103, 3084–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wave | Frequency (Hz) | Origin | Task Manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | 0.5 – 4 | Unknown | Isometric contraction, slow movements |

| Theta | 4 – 8 | Unknown | Isometric contraction, slow movements |

| Alpha | 8 – 13 | Unknown | Isometric contraction, slow movements |

| Beta | 13 – 30 | Motor cortex | Submaximal voluntary contraction |

| Lower Gamma | 30 – 60 | Motor cortex | Voluntary contraction, slow movements |

| Upper Gamma | 60 – 100 | Brainstem | Eye movement (60 – 90 Hz), respiration |

| Posterior Muscles | Anterior Muscles | Deep Anterior Muscles |

|---|---|---|

| Medial gastrocnemius (P) | Tibialis anterior (D) | Tibialis posterior (P) |

| Lateral gastrocnemius (P) | Fibularis longus (P) | Flexor digitorum longus (P) |

| Plantaris (P) | Extensor digitorum longus (D) | Flexor hallucis longus (P) |

| Soleus (P) | Fibularis brevis (P) | |

| Extensor hallucis longus (D) |

| Balance Condition | Description |

|---|---|

| EOFT | Eyes Open, Feet Together |

| ECFT | Eyes Closed, Feet Together |

| EOTanDF | Eyes Open, Feet Tandem, Dominant Foot Forward |

| ECTanDF | Eyes Closed, Feet Tandem, Dominant Foot Forward |

| EOTanDB | Eyes Open, Feet Tandem, Dominant Foot Back |

| ECTanDB | Eyes Closed, Feet Tandem, Dominant Foot Forward |

| Bands | Range (Hz) |

|---|---|

| Delta | 0 - 4 |

| Theta | 4 – 8 |

| Apha | 8 – 13 |

| Beta | 13 – 30 |

| Lower Gamma | 30 – 60 |

| Upper Gamma | 60 - 100 |

| Left Unilateral | Right Unilateral | Bilateral Homologous |

|---|---|---|

| LTA:LMG | RTA:RMG | LTA:RTA |

| LTA:LS | RTA:RS | LMG:RMG |

| LMG:LS | RMG:RS | LS:RS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).