1. Introduction

Clean water is essential for life, yet billions lack access to it. This crisis is particularly severe in developing countries where people rely on untreated surface water sources like rivers and dams. Unfortunately, these sources are often contaminated with pathogens and pollutants, causing gastrointestinal diseases like cholera, dysentery, and typhoid. According to the United Nations (UN), a staggering 2.1 billion people lack safe drinking water at home. This contamination disproportionately affects children under five, with over 700 dying daily from diarrhea linked to unsafe water. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that nearly 159 million people depend on surface water sources, and at least 2 billion people consume water contaminated with fecal matter. This situation places a tremendous burden on public health resources in developing countries [

1].

For this reason, treatment plants play a crucial role in transforming this water into a safe resource for communities. Water treatment facilities use various processes, with coagulation-flocculation being a key step. This physicochemical treatment process removes particles and clarifies the water, preparing it for sedimentation, another essential treatment method [

2]. Many impurities in water are tiny particles suspended due to electrical charges. Coagulation disrupts these charges, causing the particles to clump together into larger, heavier "flocs." These flocs are then easier to remove from the water through settling or filtration.

The most widely used coagulants and flocculants in the world are inorganic chemicals and the most common are aluminum-based and iron-based. Aluminum-based coagulants include aluminum chloride, aluminum sulfate, sodium aluminate and aluminum polychloride (PAC). Iron-based coagulants include ferric chloride, ferric sulfate and ferrous sulfate. The effectiveness of these chemicals is well known, but there are disadvantages associated with their use, such as high operating costs, negative impact on the environment, adverse effects on human health and the fact that they significantly affect the pH of treated water [

3].

Aluminum sulfate, a common coagulant, leaves traces of soluble aluminum in treated water. This form of aluminum can be absorbed by the human body, raising concerns about its potential long-term health effects [

4]. Some studies suggest a possible link between aluminum accumulation and nervous system disorders, including Alzheimer's disease [

5], or with neuropathological conditions [

6]. Aluminum can also accumulate in bones, causing excessive brittleness and softening. Other studies suggest a possible association between aluminum exposure and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinsonism with dementia [

7].

In this regard, researchers are evaluating alternatives for water treatment, such as the use of natural coagulants, which are considered safe for human health, environmentally friendly, sustainable and less polluting than chemicals due to their biodegradability. These coagulants are more accessible to emerging economies in developing countries and because they are organic the sludge produced can be used for safe fertilization [

8].

This study proposes the use of papaya (

Carica papaya), both the peel and the seeds, as sources of natural coagulant because it is a plant widely harvested in Mexico. With an estimated production of 1.1 million tons per year, Mexico is the fifth largest producer of papayas in the world. Most of the production is destined for the domestic market and the rest for export, being Mexico the largest exporter worldwide with 194,167 tons, which represents 52%. of global papaya exports in 2023 [

9]. Furthermore, papaya is one of the most produced tropical fruits in the world and can be produced at all times of the year. Furthermore, coagulants are obtained from the seeds and peel of the papaya, which are considered waste. Therefore, the production of coagulants does not affect or compete for raw materials with other markets. In this study, the Maradol variety has been considered because it is the most common one Mexico.

Previous studies with deshelled

Carica papaya seeds reported that bio-coagulant achieved a turbidity removal efficiency of 88% in polluted water [

5]. In another study, Kristianto and collaborators [

10], used papaya seeds powder as a natural coagulant for the removal of pollutants from synthetic textile wastewater showing an 84.77% color removal efficiency. Finally, Yimer and Dame [

11], tested the effectiveness of papaya seed extract for the removal of turbidity and total coliforms in raw water samples from the Tulte River in Ethiopia, reaching total coliform removal efficiencies of 96.32% and 96.19% for turbidity. These studies indicate that papaya is a viable alternative to treat surface water to obtain drinking water.

This study explores in deep the potential of Carica papaya (peel and seed) as a natural coagulant and compared with aluminum sulfate, the most widely used inorganic coagulant for water purification. Treatments with synthetic surface water were modeled (second order polynomials) and evaluated by varying relevant conditions such as initial turbidity, pH and dose of applied coagulant for a complete evaluation of them. These models can be optimized to obtain the best values to maximize the reduction of turbidity and total suspended solids, as well as to obtain the best floc formation.

The functional groups present in natural coagulants are determined which explain the coagulation and flocculation potential. The papaya-based coagulants were also tested with surface water from the Valsequillo dam in Puebla, Mexico, and this proves that papaya can be used as an eco-friendly alternative to aluminum sulfate in the treatment of surface water to obtain drinking water.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents

Aluminum sulfate was supplied by the company Autotransportes TYP, Mexico. Sulfuric acid 0.1 molar and 0.1 N caustic soda were both obtained from Hycel Mexico for pH adjustments.

2.2. Papaya Coagulants Preparation

The papaya (Carica papaya) was purchased in a local market in Cholula, Puebla. For the papaya peel coagulant, the papaya was peeled, and the pulp was removed. The peel was set to dry in the sun for 8 hours to remove moisture. The dried peel was dried at 60°C for 24 hours in an oven (FELISA model FE-291AD) and then crushed with a mortar until it was pulverized. The coagulant powder was reduced in size with a mill (Beaika model QL-002) and sieved (Sifting device W.S. Tyler Ro-Tap RX-29) to ensure a particle size of less than 75 m (8”-FH-BR-BR-US-200 Sieve). For the papaya seed coagulant, the seeds were removed and dried at 60°C for 24 hours and then crushed with a mortar and a mill until the material was pulverized. The seed coagulant powder was also sieved to ensure a particle size of less than 75 m.

2.3. Determination of Functional Groups in Carica Papaya

To determine the chemical functional groups, present in the papaya peel and seed coagulants Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used. The analysis was carried out at room temperature using the Agilent Cary 630 FTIR spectrometer and all spectra were recorded from 4000 to 400 〖cm〗^(-1) .The range chosen includes the mid-infrared region that consists of the “group frequency region”, 4000-1300 〖cm〗^(-1) (2.5-8 µm), and the “fingerprints region”, 1300-650 〖cm〗^(-1) (8.0-15.4 µm) [

12].

2.4. Preparation of Synthetic Surface Water

To simulate turbidity, a stock bentonite suspension was prepared by mixing 10 g of bentonite clay (Materias Primas Xiloxoxtla, S.A. de C.V., Mexico) with one liter of tap water. The suspension was stirred at 200 rpm for 1 h for complete mixing and dissolution and then the solution was left undisturbed for 1 h. The supernatant was then recovered, and the precipitate was discarded. To simulate organics, a humic acid stock solution was prepared by adding 1 g/L of Leonardite powder (Grupo TCDN, S.A. de C.V, México) to a liter of tap water. The suspension also was stirred at 200 rpm for 1 h for complete mixing and dissolution. The solution was then left undisturbed for 1 h and afterwards the supernatant was recovered, and the precipitate was discarded. To obtain the synthetic surface water for our experiments, both mother solutions were mixed in a 2:1 ratio and then tap water was added to obtain the desired turbidity. The prepared synthetic water contained turbidity values between low and medium, which are common for surface water.

2.5. Design of Experiments

For this study, the final turbidity (FT), the total suspended solids (TSS) and the characteristics of the floc (CF) formed are considered outputs of the clarification process. On the other hand, the inputs or parameters of the coagulation process are initial turbidity (IT), coagulant dosage (CD) and pH.

For turbidity the Formazine Attenuation Unit (FAU) is reported, which is equivalent to Nephelometric Turbidity Unit (NTU). TSS are reported in mg/L and CD is reported in parts per million (ppm). To define CF, the Willcomb index (WI) is used, a scale where the characteristics of the floc are translated into the following numerical values: 0 (colloidal floc, no sign of agglutination), 2 (floc visible, but very small), 4 (dispersed, well-formed floc, uniformly distributed, but slow settling), 6 (floc clearly distinguishable, well formed, relatively large, but precipitates slowly), 8 (good floc, which precipitates easily but not completely) and 10 (excellent floc sediments completely, leaving the water crystal clear).

2.6. Jar Test

Coagulation-flocculation experiments were carried out using surface synthetic water samples in a jar test apparatus model JLT (100-240 V / 50-60 Hz) Velp Scientifica. The jar test is a common laboratory procedure (based on the American Society of Testing Materials (ASTM) standard, D2035) used to estimate the removal efficiency of total suspended solids and turbidity by varying the conditions, amount and type of coagulant on a small scale to predict the performance of large-scale treatment operation.

Coagulation experiments were carried out as follows. After adding the coagulant, the solution was mixed at 200 rpm for 1 min, followed by a slow mix at 30 rpm for 15 min and sedimentation for an additional 30 min.

2.7. Analytical Methods

To evaluate the performance of the coagulants, the physicochemical characteristics of the water before and after the coagulation-flocculation process were determined for each run. The parameters that were measured in water include pH, turbidity (FAU) and total suspended solids (mg/L). Turbidity and suspended solids were measured with the HACH DR/890 portable colorimeter, and pH was measured with a Thermo Scientific Orion Star A3255 Multi Parametric Meter calibrated before starting the tests.

3. Results

The ranges of the coagulation process variables and their levels are presented in

Table 1.

After establishing the coagulation process parameters and levels, the design matrix was generated with Statgraphics Centurion Version 19.4.04 (32-bit) software. We used a randomized Box Behnken design without repetitions. To anticipate all possibilities and select the optimal clarification process, 15 experiments in 1 block were required in this case. The design matrix is presented in

Table 2.

After establishing the inputs or parameters of the coagulation process, the output variables of the process were determined experimentally, as can be seen in

Table 3. This was repeated three times in these conditions and the average values for FT, TSS and CF were calculated. Point values from all experiments with means and standard deviations are in

Appendix A.

The Response Surface Method (RSM) was used for optimizing the clarification process and determining the relationships between input variables and output variables. The statistical analysis of the results was carried out using the Statgraphics Centurion Version 19.4.04 (32-bit) software.

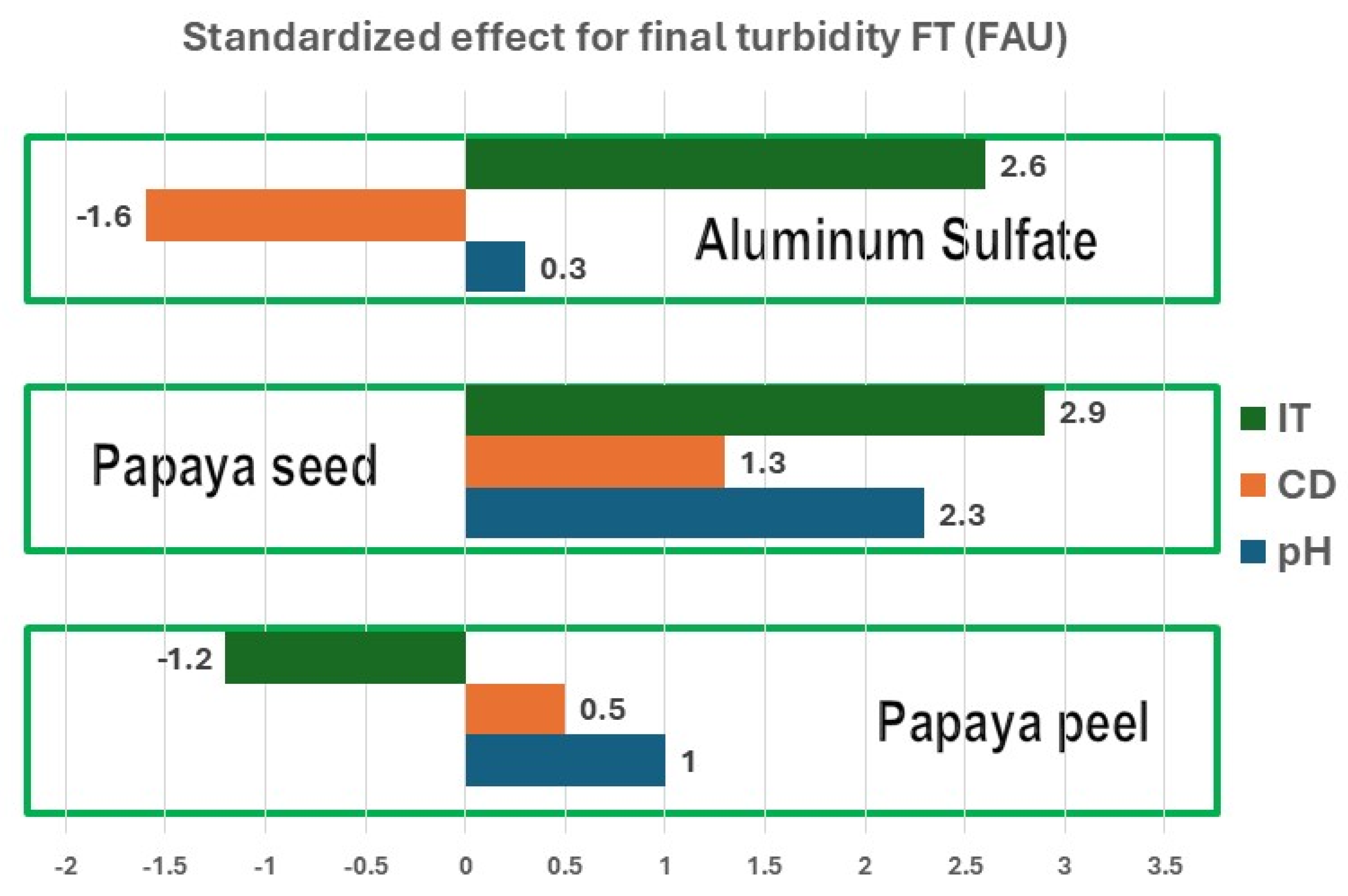

Pareto diagrams (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) illustrate the standardized effect of varying each input variable (IT, CD, and pH) by one unit on the output variables (FT, TSS and CF). Positive values indicate that increasing the input variable by one unit leads to an increase in the output variable, while negative values indicate a decrease.

Figure 1 presents Pareto diagrams for FT, where IT has the most significant impact. For papaya peel coagulants, increasing IT leads to a decrease in FT, while for papaya seed coagulant and aluminum sulfate, increasing IT results in an increase in FT. This suggests that the papaya seed coagulant is more effective in treating highly turbid water.

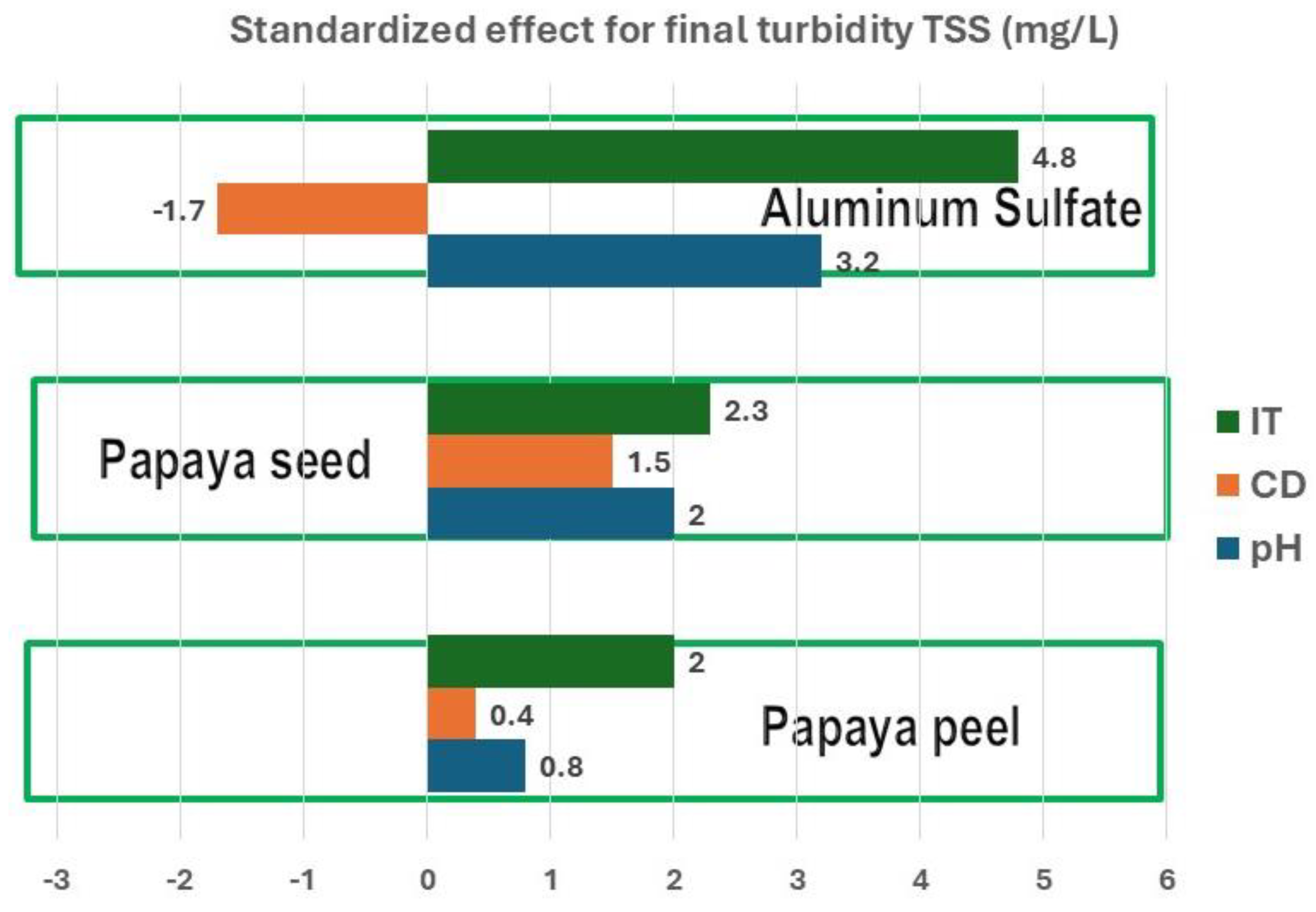

Pareto diagrams for TSS are presented in

Figure 2. Here it can be observed the important effect of IT on TSS, which is positive for the three coagulants. For aluminum sulfate the CD effect is negative, which implies that high doses must be used to obtain good results.

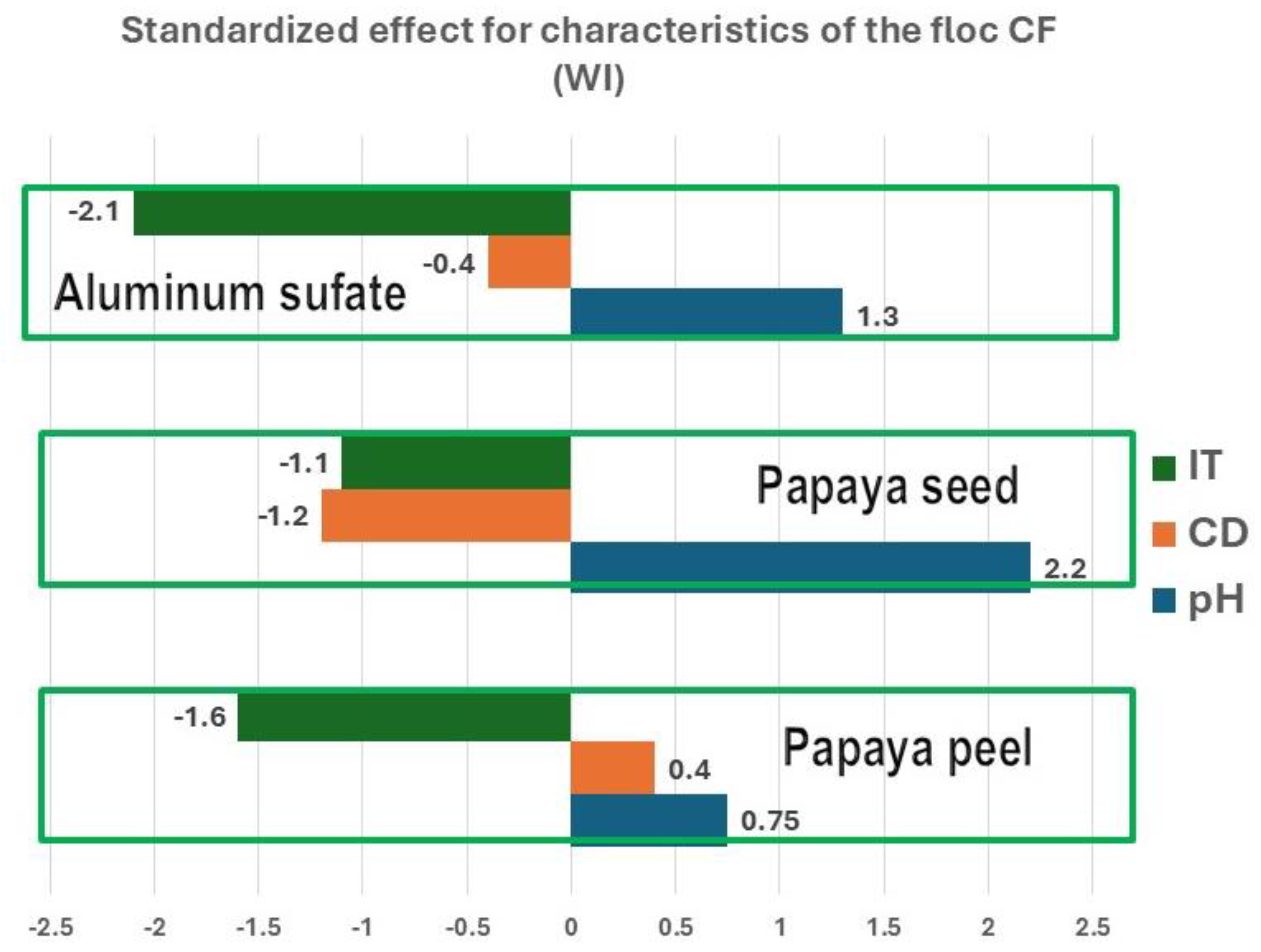

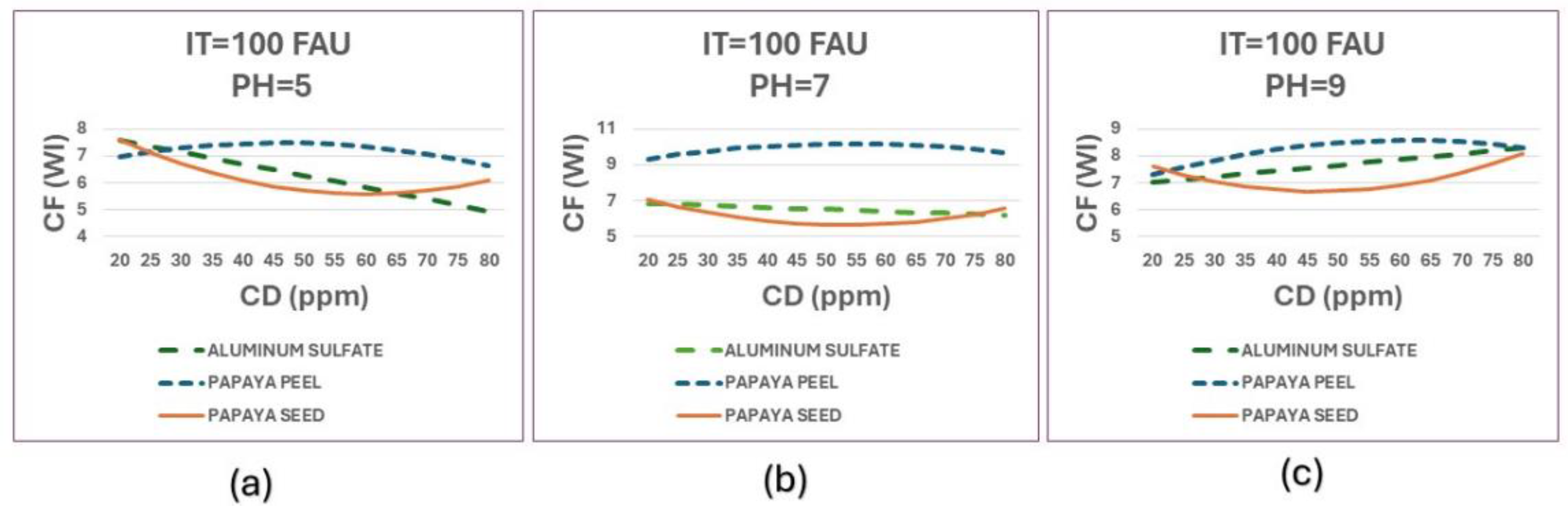

In

Figure 3, it is observed that IT significantly affects CF in a negative way which indicates that low turbid water will favor the formation of flocs. The pH affects positively in all three cases, which indicates that an alkaline pH will produce better flocs.

Through statistical techniques of RSM, quadratic polynomial equations were developed to predict the response as a function of the independent variables involving their interactions. Three equations were developed for each output variable, FT, TSS and CF, for each coagulant tested. These equations show how a combination of second order polynomials is formed by combining the input variables that provide the output.

The mathematical models have the following general forms:

The values for the variables from each equation can be seen in

Table 4.

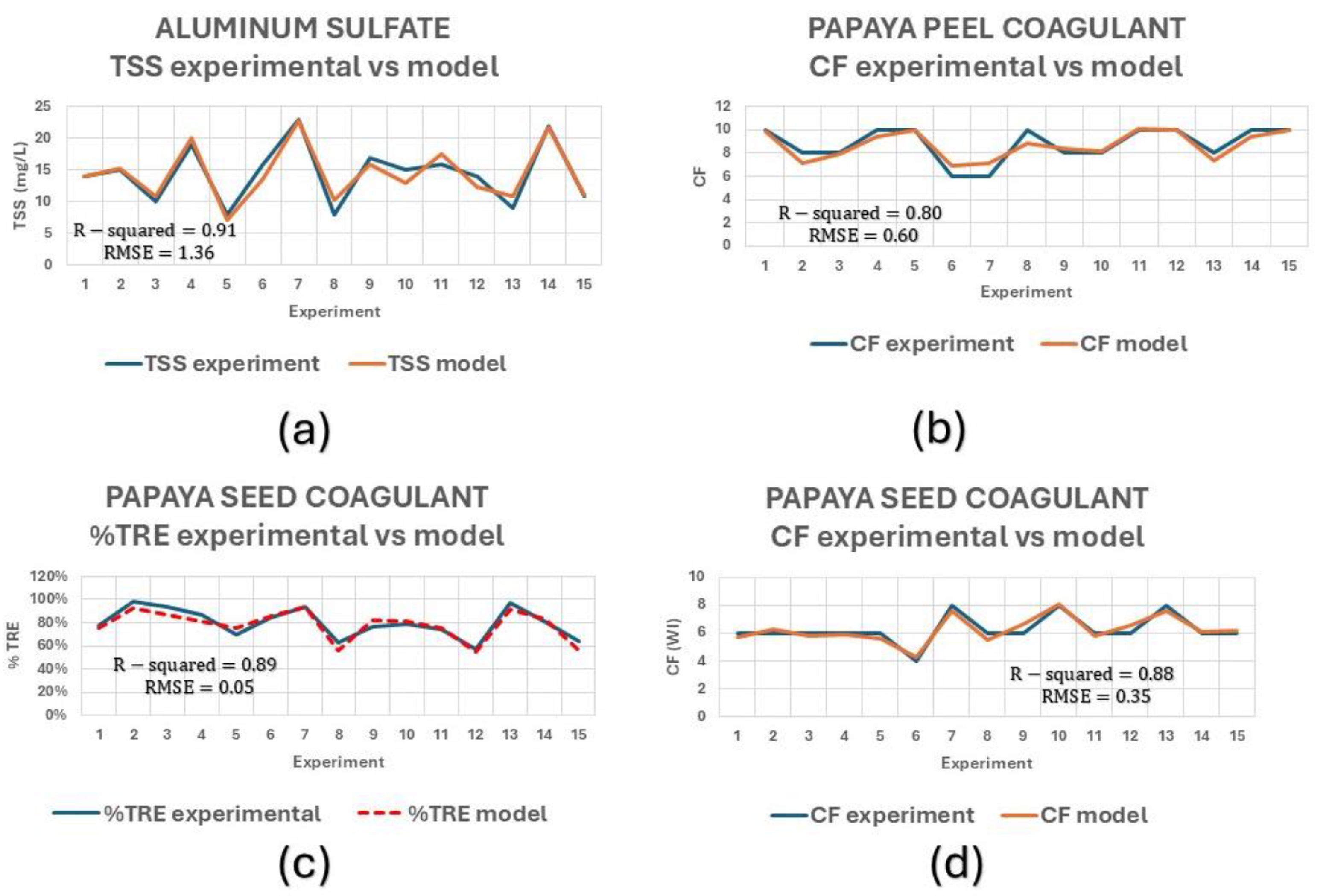

Comparisons between the obtained quadratic regression models and the experimental values are presented in

Figure 4, where a good fit can be seen between experimental and predicted data. The R-squared values from the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) values are presented in

Figure 4. Turbidity removal percentages (%TRE) were determined using IT and FT as presented in Equation (4).

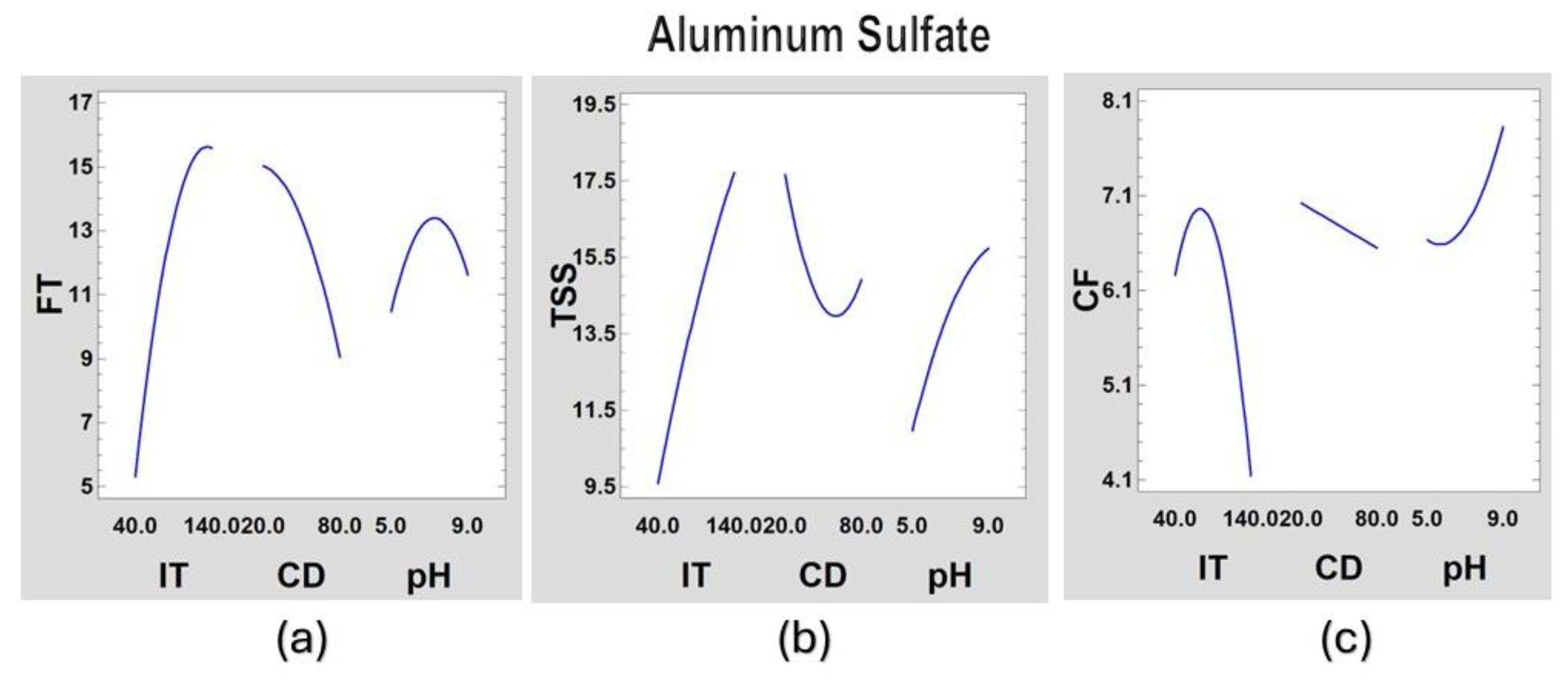

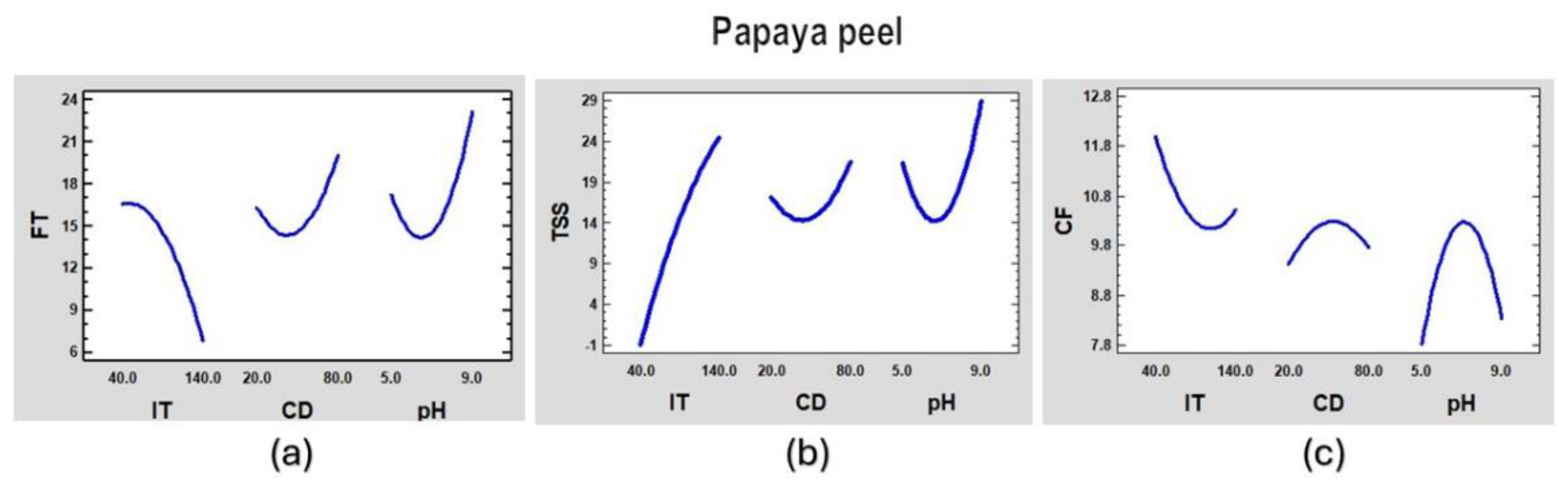

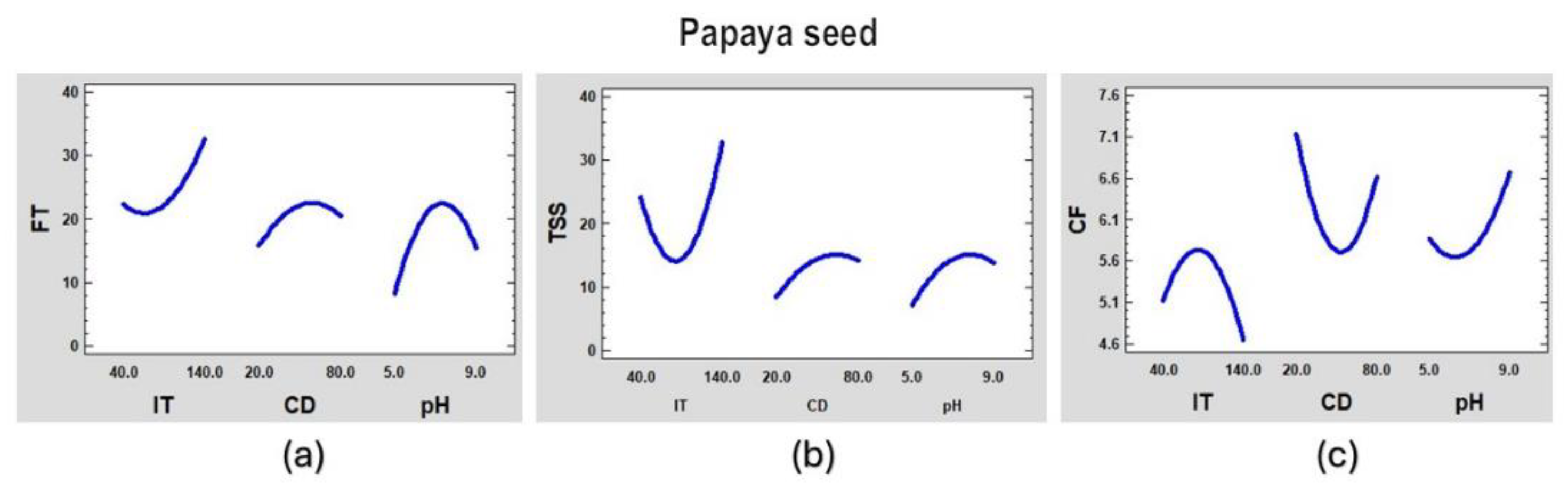

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 illustrate the effects of input variables (IT, CD and pH) on output variables (FT, TSS and CF) for each coagulant within the specified ranges. In these graphs, variables that are not being studied are held constant at their midpoint values. By analyzing these figures, we can identify optimal operating conditions for each coagulant.

From the figures above, we can observe that aluminum sulfate will work better with low turbidity and at a higher dose although there will not be good formation of the floc. The papaya peel will work better at medium doses, high turbidity and generally have good floc formation. The papaya seed coagulant works best with low doses and at extreme pHs.

These models can be optimized to obtain certain required values. For example, having fixed pH and initial turbidity (IT), the coagulant dose (CD) can be varied to obtain the best results for final turbidity (FT), total suspended solids (TSS) and the best formed flocs (CF).

4. Discussion

4.1. Coagulation and Flocculation Activity

Coagulation and flocculation are essential processes to separate and remove suspended and colloidal solids in water and improve water clarity and reduce turbidity. The following analysis evaluates the ability of coagulants to better understand the effectiveness of the treatment.

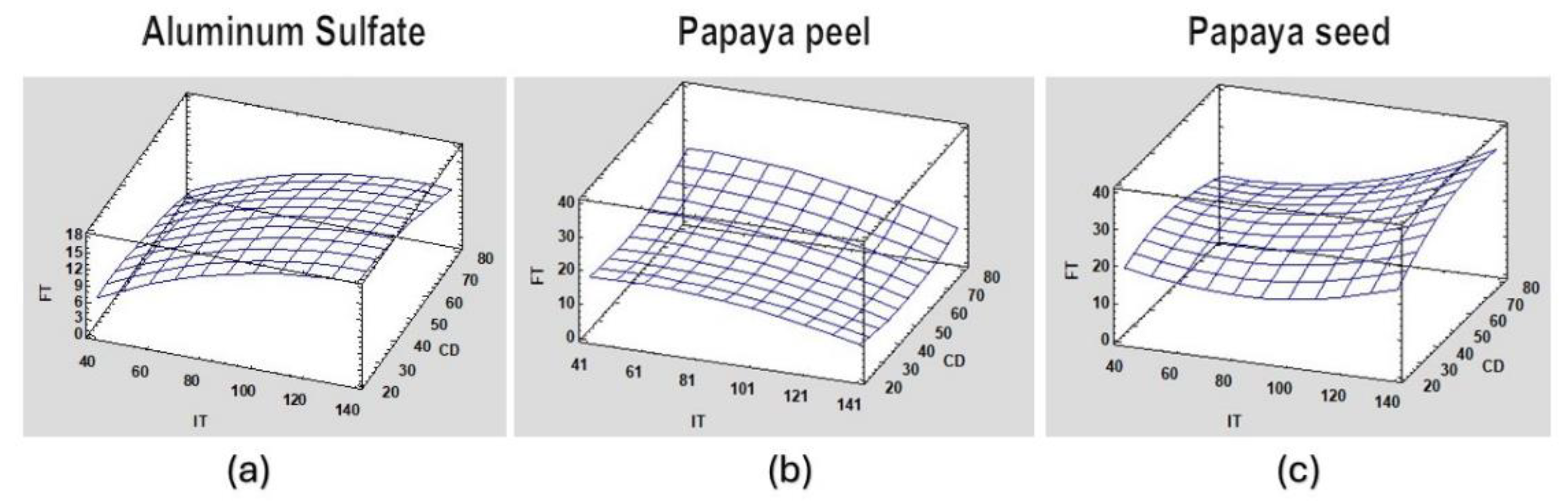

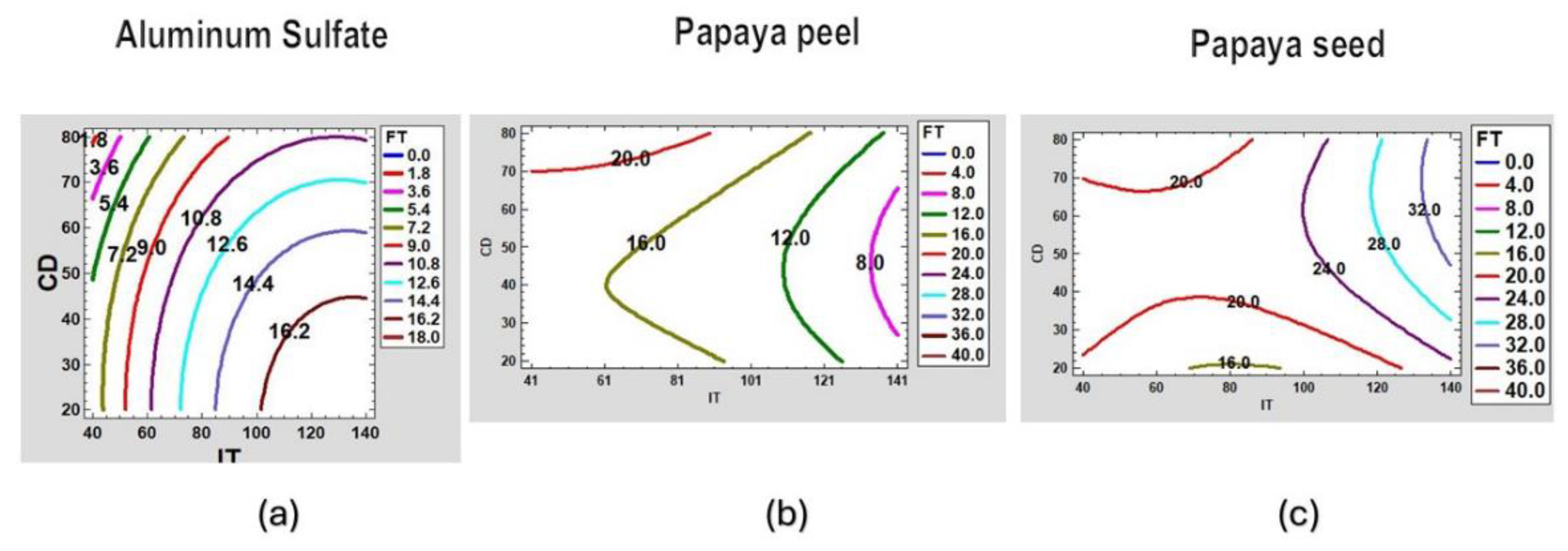

Figure 8 shows the FT response surface for aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulant at pH=7.0 which can be considered a common value in surface waters.

Good behavior is observed for the three coagulants but with some differences. Aluminum sulfate works best at low turbidity; the papaya peel coagulant works best at low doses and with high turbidity; and the papaya seed coagulant works best at low doses and medium turbidity.

Figure 9 shows the contour plots of the estimated FT response surface for aluminum sulfate, papaya peel coagulant and papaya seed coagulant at pH=7.0.

It can be clearly observed that the best results for aluminum sulphate are obtained at higher doses and at low water turbidity. However, for the papaya peel coagulant, medium doses and high turbidity are required, and for the papaya seed coagulant a low dose and medium turbidity are required to optimize its results.

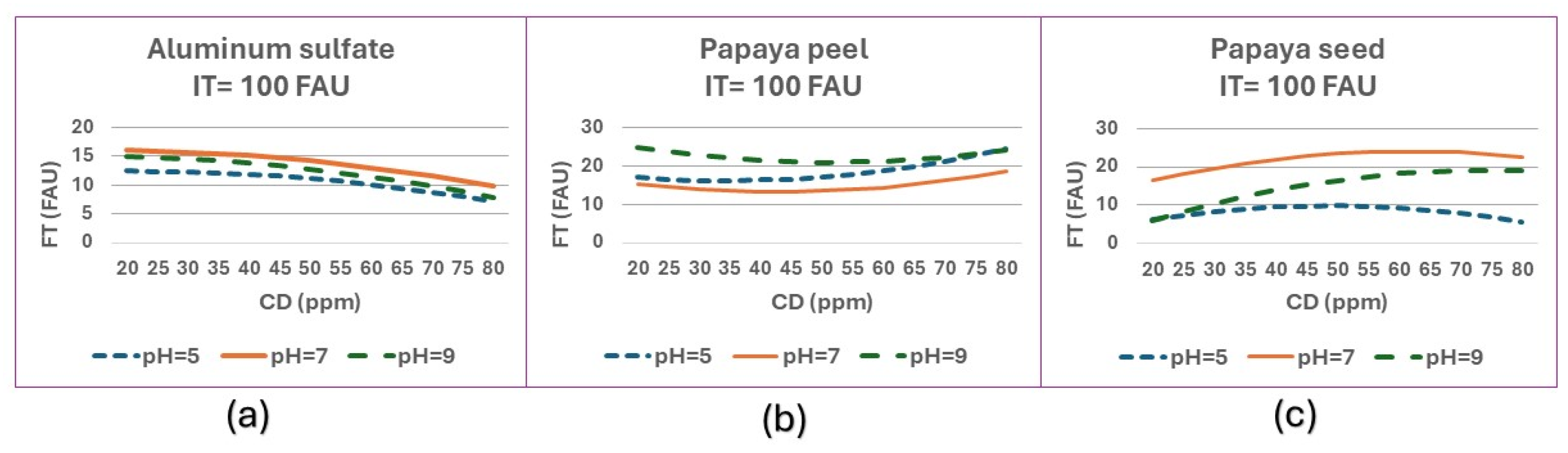

Figure 10 shows the behavior of FT at different pH values with a fixed IT of 100 FAU (medium turbidity) for aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Aluminum sulfate and papaya seed coagulant have the best results. Aluminum sulphate improves its results as the dose increases, while papaya peel has the opposite behavior. The papaya seed coagulant has the best results at an alkaline ph.

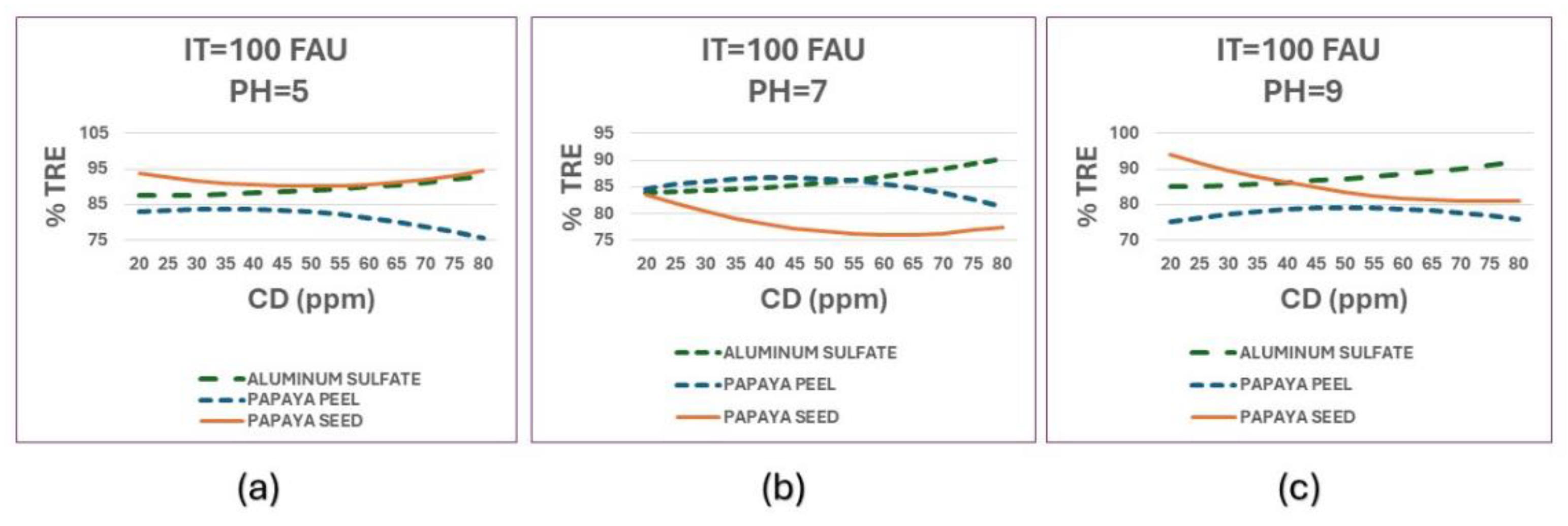

On the other hand, comparing the three coagulants in terms of the percentage of turbidity removal (%TRE) to see their effectiveness in purifying surface water, a comparison of the three at different pH values is shown in

Figure 11.

In general, the three coagulants show good results with turbidity removal percentages (%TRE) between 75% and 95%, with the best results for papaya seed coagulant, although at neutral pH it is not as effective. At neutral pH, aluminum sulfate and papaya peel coagulant have similar results.

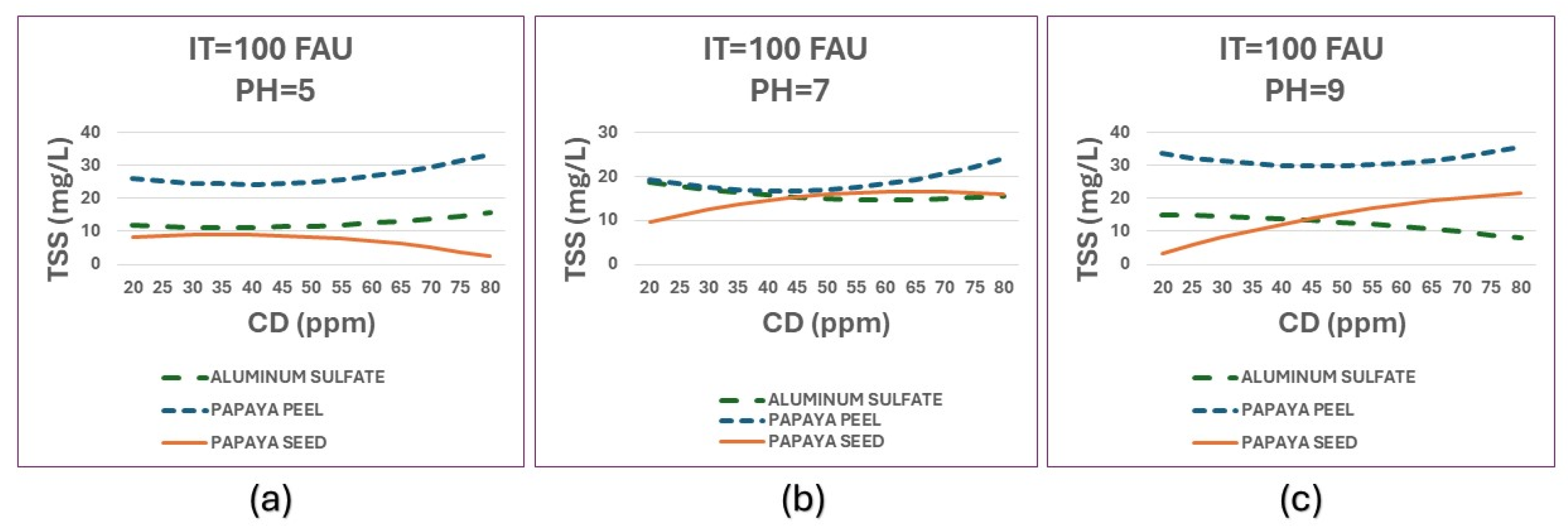

Figure 12 shows comparative graphs of TSS obtained by the three coagulants with TI=100 FAU at different pH values.

In general, good TSS removal is observed from all three coagulants, with papaya seed coagulant showing the best results at lower doses. The three coagulants have a similar behavior at neutral pH and medium doses. Considering an initial synthetic surface water with IT of 100 FAU and TSS around 101 mg/L, the turbidity removal efficiency range is between 65% and 98%.

Figure 13 presents a comparison of CF (WI) achieved by the three coagulants at an initial turbidity of 100 FAU and varying pH levels.

Natural coagulants form much better flocs at alkaline pH. The papaya seed coagulant is the best and is consistent at all three pH levels. Aluminum sulphate at pH 5 has very weak flocs and tends to disperse or resuspend again. This would require the use of an additional flocculant such as polyacrylamide to improve the flocs.

To better understand the mechanisms behind the floc formation for the nopal cladode and pricky pear peel, the following section discusses the results from the characterization of the coagulants.

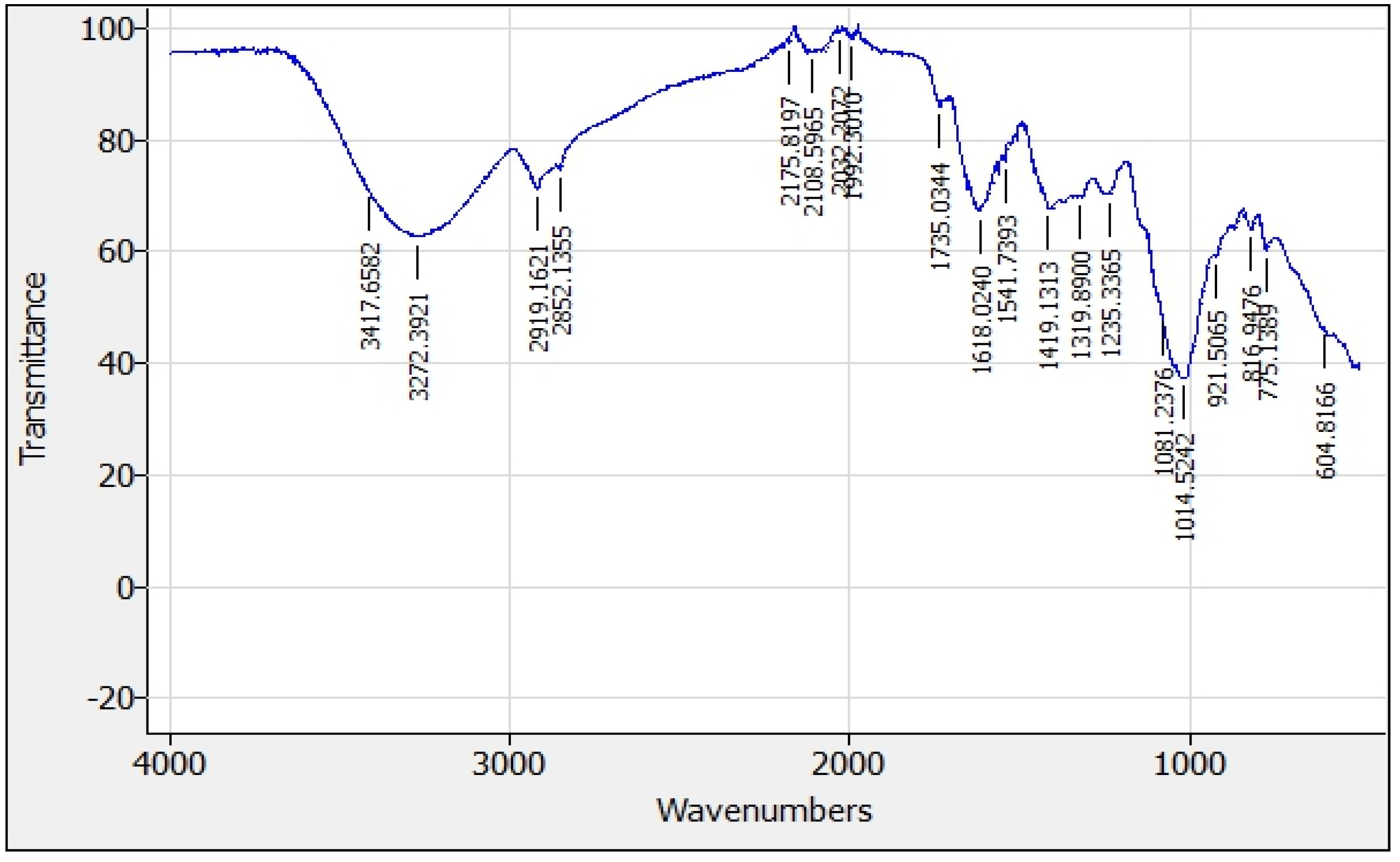

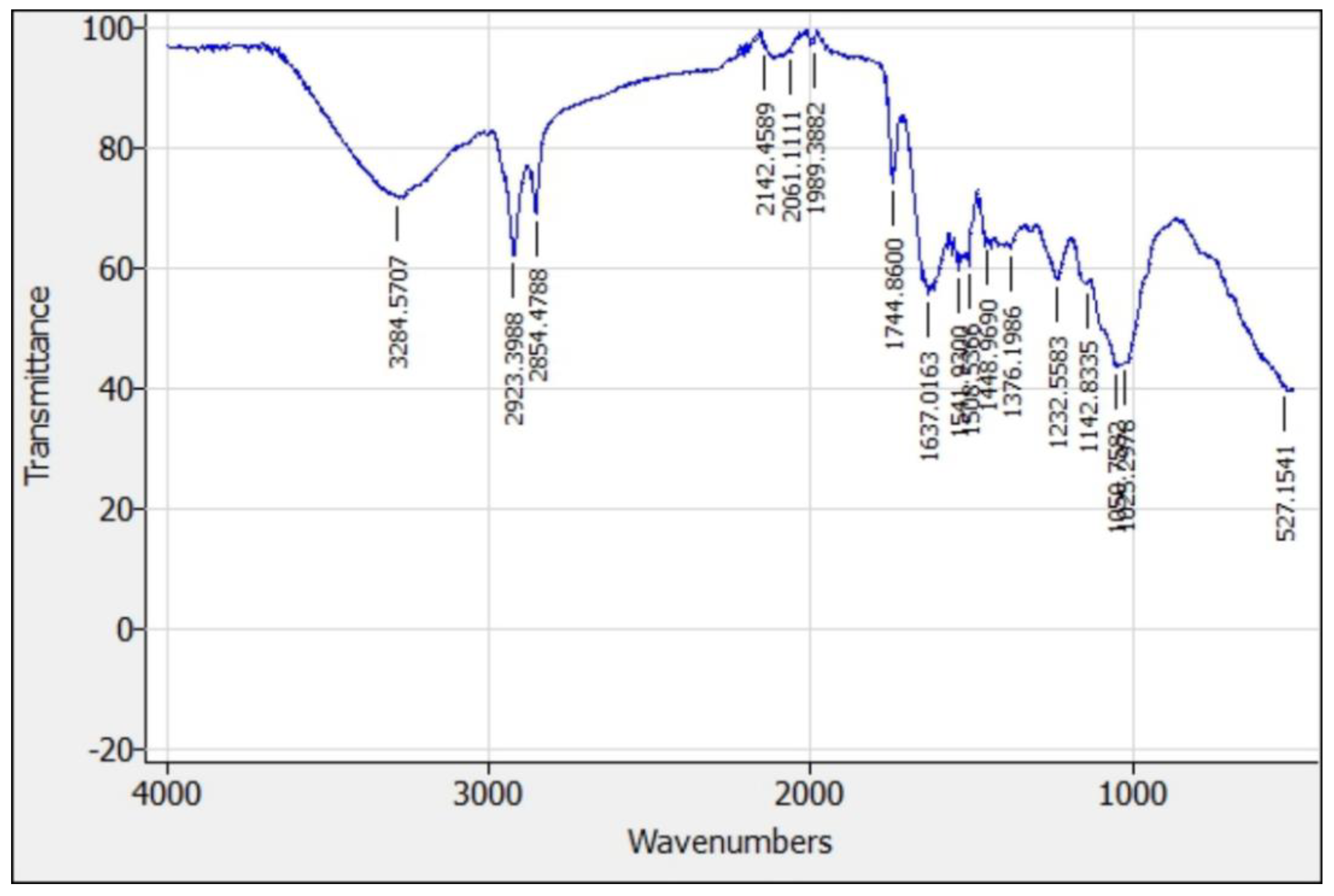

4.2. Functional Groups in Carica papaya

The above results show the behavior of the evaluated natural coagulants at different pHs, different values of initial turbidity and with different application doses. In the case of chemical coagulants, the main removal mechanism is charging neutralization mainly due to the characteristics of the chemical. However, natural coagulants mechanism depends on the different functional groups present in their structure, where polymer chains play an important role in the removal of pollutants from the water. The mechanisms of coagulation and flocculation are closely related to functional groups such as carbonyl, carboxyl, and hydroxyl, naturally occurring in molecules present in fruits such as polysaccharides and protein which promote bridging and adsorption mechanisms [

13]. Amines, carbonyl, carboxyl, methylene, and hydroxyl groups present can also participate in charge neutralization mechanism and amides, amines, carbonyl, and methylene are known to participate in the patch flocculation mechanism [

14].

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 present the FTIR spectrum and absorption bands for the functional groups present in papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

The identification of the main absorption bands and related functional groups for the papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants FTIR spectrums are presented in

Table 5.

Based on the above results, papaya peel and papaya seed work as coagulants due to the presence of various molecules and functional groups, mainly coming from positively charged proteins and carbohydrates which bind with negatively charged particles (silt, clay, bacteria, and toxins etc.) and could play an important role in the adsorption of target contaminants. The presence of pectin (1143-1233,1618-1735,3272-3284) and poly galacturonic acid (527-1051,1143-1233,1319-1376) largely explain the ability of the coagulant to reduce the turbidity of water.

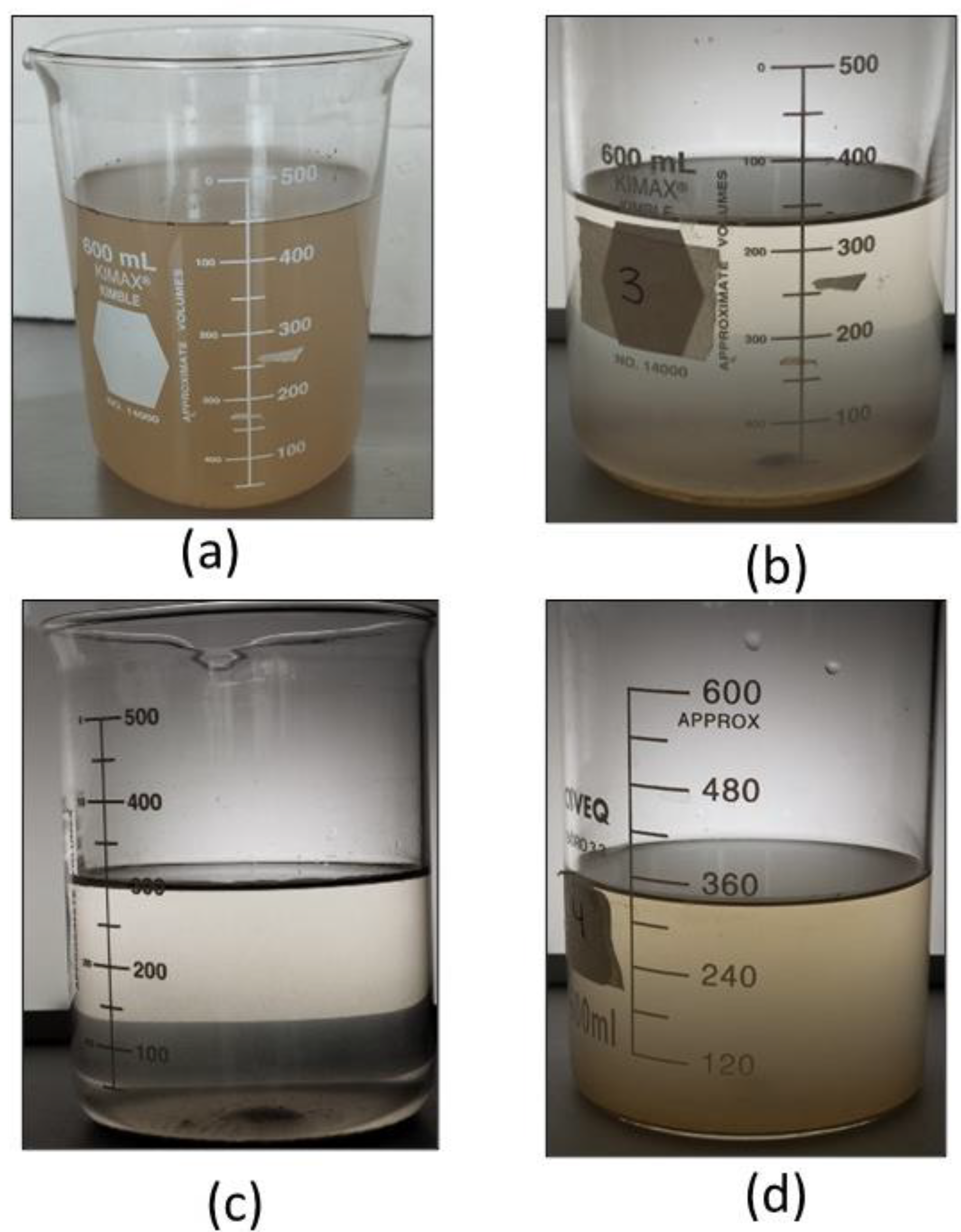

4.3. Coagulants Test with Real Surface Water

Finally, tests were carried out with real surface water to confirm the functioning of the coagulants. Water was taken from the Manuel Ávila Camacho dam, known as Valsequillo dam, located in the city of Puebla, Pue., Mexico, being the largest surface water source in the area and is located at the mouth of the Atoyac River which is heavily contaminated. Water samples were taken from three different points located at 18°56'53.3"N 98°15'23.3"W (point 1), 18°54'09.5"N 98°10'03.2"W (point 2) and 18°54'49.6"N 98°06'38.1"W (point 3), as shown in

Figure 16.

A proportional composite water sample was made with water collected from the three sites, which had the following characteristics: IT= 247 FAU, TSS= 281 mg/L and pH= 7.4.

Each of the coagulants was tested with this water at different doses, determining the most optimal dose for each one. The percentage of turbidity removal (%TRE) was calculated as well as the percentage of removal of total suspended solids (%TSSRE).

The results are presented in

Table 6.

The best results are observed for the papaya seed coagulant with a turbidity removal efficiency of 90.69%, followed by aluminum sulfate with 78.14% and then papaya peel coagulant with 69.23%. For the TSS removal efficiency, the results are similar, with the papaya seed coagulant obtaining 91.46% removal, being the best result of all.

To improve the results of aluminum sulfate and papaya peel we would need to add a flocculant as a treatment aid. Something very important to consider is that the optimal dosage for the papaya seed coagulant was 30 ppm, much lower than those of the other two coagulants, which makes it a very attractive alternative from an economic point of view. The optimal dosage for the papaya peel coagulant was also lower than the optimal dose for aluminum sulfate, indicating that the two natural alternatives are competitive.

Figure 17 shows pictures of the water from the Valsequillo dam before and after being treated with the three coagulants. Visually, it is evident that the papaya seed coagulant is the best option followed by papaya peel one.

These results confirm the coagulation-flocculation capacity of papaya-based coagulants, which even surpass aluminum sulfate for the treatment of surface waters.

5. Conclusions

Papaya seed and papaya peel (Carica papaya) coagulants were evaluated alongside aluminum sulfate, a common inorganic coagulant, for their effectiveness in treating synthetic surface water. The processes for the three coagulants were modeled, developing the polynomials that allow predicting the expected removal efficiencies from the initial parameters. The tests demonstrated high turbidity (%TRE) and total suspended solids removal efficiencies (%TSSRE), between 75 - 95%, and 65-98%, respectively. Furthermore, the analysis of floc characteristics, using the Willcomb index, indicated strong floc formation with values ranging from 8 to 10 for the natural coagulants.

By characterizing the materials, it was possible to identify molecules, and functional groups present in natural coagulants that participate in the coagulation-flocculation process and that allow them to form better flocs than aluminum sulfate.

The three coagulants were tested with surface water from the Valsequillo dam in Puebla, Mexico, showing very good results with %TRE between 69 and 92% and %TSSRE between 60 and 91%, with the papaya seed coagulant presenting the best results. It can be concluded that papaya-based coagulants can be used as an eco-friendly alternative to aluminum sulfate in the physicochemical treatment to purify surface water for human consumption.

Author Contributions

For Guillermo Díaz-Martínez contributed with conceptualization, methodology, software and writing-original draft preparation; Ricardo Navarro-Amador and Jose Luis Sánchez-Salas contributed with methodology, writing-review and editing and D. Xanat Flores-Cervantes contributed with conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing-review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external fundi.

Data Availability Statement

Any information related to the research is available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

Support provided by the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) with a scholarship number 780779. Additional support was received from the Universidad de las Américas Puebla (UDLAP) through a graduate fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Results of all the jar test experiments.

| |

Outputs Final Turbidity FT (FAU) |

| |

Aluminum Sulfate |

Papaya peel |

Papaya seed |

| E |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) (1) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) (2) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) (3) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) average |

Standard deviation (FAU) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) (1) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) (2) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) (3) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) average |

Standard deviation (FAU) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) (1) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) (2) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) (3) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) average |

Standard deviation (FAU) |

| 1 |

20 |

18 |

17 |

18 |

1.53 |

17 |

17 |

17 |

17 |

0.00 |

20 |

21 |

21 |

21 |

0.58 |

| 2 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

7 |

0.58 |

18 |

19 |

17 |

18 |

1.00 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1.73 |

| 3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

0.00 |

12 |

15 |

16 |

14 |

2.08 |

6 |

4 |

7 |

6 |

1.53 |

| 4 |

18 |

18 |

17 |

18 |

0.58 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

0.59 |

20 |

19 |

18 |

19 |

1.00 |

| 5 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

1.00 |

21 |

22 |

22 |

22 |

0.58 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

0.00 |

| 6 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

0.00 |

24 |

22 |

21 |

22 |

1.51 |

21 |

21 |

20 |

21 |

0.58 |

| 7 |

15 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

0.58 |

33 |

37 |

36 |

35 |

2.08 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

1.15 |

| 8 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

0.58 |

25 |

26 |

24 |

25 |

1.00 |

17 |

14 |

13 |

15 |

2.08 |

| 9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

0.00 |

28 |

28 |

28 |

28 |

0.00 |

23 |

21 |

18 |

21 |

2.52 |

| 10 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

0.00 |

29 |

30 |

27 |

29 |

1.53 |

19 |

18 |

20 |

19 |

1.00 |

| 11 |

12 |

10 |

9 |

10 |

1.53 |

16 |

17 |

15 |

16 |

1.00 |

36 |

35 |

36 |

36 |

0.58 |

| 12 |

6 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

1.53 |

17 |

22 |

23 |

21 |

3.21 |

18 |

17 |

19 |

18 |

1.00 |

| 13 |

16 |

17 |

14 |

16 |

1.53 |

12 |

11 |

13 |

12 |

1.00 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

1.00 |

| 14 |

15 |

12 |

12 |

13 |

1.73 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

0.00 |

26 |

26 |

25 |

26 |

0.58 |

| 15 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

1.00 |

28 |

28 |

27 |

28 |

0.58 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

0.00 |

| |

Outputs Final Total Suspended Solids TSS (mg/L) |

| |

Aluminum Sulfate |

Papaya peel |

Papaya seed |

| EXPERIMENT |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) (1) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) (2) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) (3) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) average |

Standard deviation (FAU) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) (1) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) (2) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) (3) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) average |

Standard deviation (FAU) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) (1) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) (2) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) (3) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) average |

Standard deviation (FAU) |

| 1 |

12 |

16 |

15 |

14 |

2.08 |

18 |

14 |

19 |

17 |

2.65 |

13 |

10 |

15 |

13 |

2.52 |

| 2 |

17 |

11 |

16 |

15 |

3.21 |

19 |

15 |

18 |

17 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1.15 |

| 3 |

8 |

11 |

10 |

10 |

1.53 |

14 |

18 |

13 |

15 |

2.65 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

7 |

1.00 |

| 4 |

22 |

16 |

20 |

19 |

3.06 |

18 |

12 |

19 |

16 |

3.79 |

28 |

33 |

24 |

28 |

4.51 |

| 5 |

12 |

5 |

6 |

8 |

3.79 |

13 |

9 |

13 |

12 |

2.31 |

23 |

20 |

25 |

23 |

2.52 |

| 6 |

19 |

18 |

12 |

16 |

3.79 |

45 |

54 |

41 |

47 |

6.66 |

20 |

22 |

25 |

22 |

2.52 |

| 7 |

21 |

20 |

28 |

23 |

4.36 |

52 |

43 |

45 |

47 |

4.73 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1.53 |

| 8 |

14 |

8 |

1 |

8 |

6.51 |

10 |

12 |

12 |

11 |

1.15 |

27 |

23 |

20 |

23 |

3.51 |

| 9 |

23 |

14 |

15 |

17 |

4.93 |

34 |

41 |

36 |

37 |

3.61 |

23 |

13 |

18 |

18 |

5.00 |

| 10 |

16 |

13 |

17 |

15 |

2.08 |

40 |

35 |

36 |

37 |

2.65 |

18 |

25 |

21 |

21 |

3.51 |

| 11 |

18 |

15 |

14 |

16 |

2.08 |

42 |

35 |

38 |

38 |

3.51 |

40 |

35 |

34 |

36 |

3.21 |

| 12 |

13 |

9 |

19 |

14 |

5.03 |

7 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

0.58 |

19 |

16 |

14 |

16 |

2.52 |

| 13 |

10 |

6 |

12 |

9 |

3.06 |

11 |

15 |

17 |

14 |

3.06 |

5 |

7 |

4 |

5 |

1.53 |

| 14 |

26 |

18 |

22 |

22 |

4.00 |

31 |

21 |

24 |

25 |

5.13 |

35 |

27 |

32 |

31 |

4.04 |

| 15 |

14 |

11 |

9 |

11 |

2.52 |

16 |

15 |

14 |

15 |

1.00 |

21 |

17 |

17 |

18 |

2.31 |

| |

Outputs Final Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) |

| |

Aluminum Sulfate |

Papaya peel |

Papaya seed |

| EXPERIMENT |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) (1) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) (2) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) (3) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) average |

Standard deviation (FAU) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) (1) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) (2) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) (3) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) average |

Standard deviation (FAU) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) (1) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) (2) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) (3) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) average |

Standard deviation (FAU) |

| 1 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

10 |

1.15 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

| 2 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

0.00 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

| 3 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

0.00 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

0.00 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

| 4 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

10 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

1.15 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

| 5 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

0.00 |

6 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

1.15 |

| 6 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

1.15 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

0.00 |

| 7 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

6 |

4 |

6 |

6 |

1.15 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

0.00 |

| 8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

0.00 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

10 |

1.15 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

| 9 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

1.15 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

0.00 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

| 10 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

0.00 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

1.15 |

8 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

1.15 |

| 11 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

1.15 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

0.00 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

| 12 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

1.15 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

| 13 |

8 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

1.15 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

1.15 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

1.15 |

| 14 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

0.00 |

6 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

1.15 |

| 15 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

10 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

1.15 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

0.00 |

References

- ONU -Agua. (2022, abril 9). Naciones Unidas. Agua de las Naciones Unidas. https://www.unwater.org.

- Saritha, V., Karnena, M. K., & Dwarapureddi, B. K. (2019). “Exploring natural coagulants as impending alternatives towards sustainable water clarification” – A comparative studies of natural coagulants with alum. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 32, 100982. [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, N. S., Muda, K., Loan, L. W., Sgawi, M. S., & Abdul Rahman, M. A. (2019). Potential of Fruit Peels in Becoming Natural Coagulant for Water Treatment. International Journal of Integrated Engineering, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Niquette, P., Monette, F., Azzouz, A., & Hausler, R. (2004). Impacts of Substituting Aluminum-Based Coagulants in Drinking Water Treatment. Water Quality Research Journal, 39(3), 303-310. [CrossRef]

- Amran, A. H., Zaidi, N. S., Syafiuddin, A., Zhan, L. Z., Bahrodin, M. B., Mehmood, M. A., & Boopathy, R. (2021). Potential of Carica papaya Seed-Derived Bio-Coagulant to Remove Turbidity from Polluted Water Assessed through Experimental and Modeling-Based Study. Applied Sciences, 11(12), 5715. [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Arias, J., Lugo-Arias, E., Ovallos-Gazabon, D., Arango, J., de la Puente, M., & Silva, J. (2020). Effectiveness of the mixture of nopal and cassava starch as clarifying substances in water purification: A case study in Colombia. Heliyon, 6(6), e04296. [CrossRef]

- Krupińska, I. (2020). Aluminium Drinking Water Treatment Residuals and Their Toxic Impact on Human Health. Molecules, 25(3), 641. [CrossRef]

- Czerwionka, K., Wilinska, A., & Tuszynska, A. (2020). The Use of Organic Coagulants in the Primary Precipitation Process at Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water, 12(6), 1650. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2024). Major Tropical Fruits Market Review. Preliminary Results 2023. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/markets-and-trade/commodities/tropical-fruits.

- Kristianto, H., Kurniawan, M. A., & Soetedjo, J. N. M. (2018). Utilization of Papaya Seeds as Natural Coagulant for Synthetic Textile Coloring Agent Wastewater Treatment. International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology, 8(5), 2071-2077. [CrossRef]

- Yimer, A., & Dame, B. (2021). Papaya seed extract as coagulant for potable water treatment in the case of Tulte River for the community of Yekuset district, Ethiopia. Environmental Challenges, 4, 100198. [CrossRef]

- Willard, Hobart H., Merritt, Lynne L., Dean, John A., & Settle, Frank A. (1988). Métodos Instrumentales de Análisis (Segunda impresión). Compañía Editorial Continental, S.A. de C.V.

- Othmani, B., Gamelas, J. A. F., Rasteiro, M. G., & Khadhraoui, M. (2020). Characterization of Two Cactus Formulation-Based Flocculants and Investigation on Their Flocculating Ability for Cationic and Anionic Dyes Removal. Polymers, 12(9), 1964. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, S. B., Imron, M. F., Chik, C. E. N. C. E., Owodunni, A. A., Ahmad, A., Alnawajha, M. M., Rahim, N. F. M., Said, N. S. M., Abdullah, S. R. S., Kasan, N. A., Ismail, S., Othman, A. R., & Hasan, H. A. (2022). What compound inside biocoagulants/bioflocculants is contributing the most to the coagulation and flocculation processes? Science of The Total Environment, 806, 150902. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Pareto diagrams for final turbidity (FT) of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Figure 1.

Pareto diagrams for final turbidity (FT) of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Figure 2.

Pareto diagrams for total suspended solids (TSS) of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Figure 2.

Pareto diagrams for total suspended solids (TSS) of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Figure 3.

Pareto diagrams for characteristics of the floc (CF) of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Figure 3.

Pareto diagrams for characteristics of the floc (CF) of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Figure 4.

Comparative of experimental results with the models for (a) TSS of aluminum sulfate; (b) CF of papaya peel coagulant; (c) %TRE of papaya seed coagulant; and (d) CF of papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 4.

Comparative of experimental results with the models for (a) TSS of aluminum sulfate; (b) CF of papaya peel coagulant; (c) %TRE of papaya seed coagulant; and (d) CF of papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 5.

Main effects graph of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for aluminum sulfate for (a) FT, (b) TSS and (c) CF.

Figure 5.

Main effects graph of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for aluminum sulfate for (a) FT, (b) TSS and (c) CF.

Figure 6.

Main effects graph of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for papaya peel coagulant for (a) FT, (b) TSS and (c) CF.

Figure 6.

Main effects graph of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for papaya peel coagulant for (a) FT, (b) TSS and (c) CF.

Figure 7.

Main effects graph of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for papaya seed coagulant for (a) FT, (b) TSS and (c) CF.

Figure 7.

Main effects graph of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for papaya seed coagulant for (a) FT, (b) TSS and (c) CF.

Figure 8.

Estimated response surface of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for FT at pH=7 for (a) aluminum sulfate; (b) papaya peel coagulant, and (c) papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 8.

Estimated response surface of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for FT at pH=7 for (a) aluminum sulfate; (b) papaya peel coagulant, and (c) papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 9.

Contour plots of the estimated response surface of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for FT at pH=7 for (a) aluminum sulfate; (b) papaya peel coagulant; and (c) papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 9.

Contour plots of the estimated response surface of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water for FT at pH=7 for (a) aluminum sulfate; (b) papaya peel coagulant; and (c) papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 10.

FT of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water at different pH values with initial value of IT=100 FAU for (a) aluminum sulfate; (b) papaya peel coagulant; and (c) papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 10.

FT of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water at different pH values with initial value of IT=100 FAU for (a) aluminum sulfate; (b) papaya peel coagulant; and (c) papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 11.

Percentage of turbidity removal (%TRE) of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water at different pH values with initial value of IT=100 FAU for aluminum sulfate, papaya peel coagulant, and papaya seed coagulant at (a) pH=5, (b) pH=7 and (c) pH=9.

Figure 11.

Percentage of turbidity removal (%TRE) of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water at different pH values with initial value of IT=100 FAU for aluminum sulfate, papaya peel coagulant, and papaya seed coagulant at (a) pH=5, (b) pH=7 and (c) pH=9.

Figure 12.

TSS of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water at different pH values with initial value of IT=100 FAU for aluminum sulfate, papaya peel coagulant, and papaya seed coagulant at (a) pH=5, (b) pH=7 and (c) pH=9.

Figure 12.

TSS of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water at different pH values with initial value of IT=100 FAU for aluminum sulfate, papaya peel coagulant, and papaya seed coagulant at (a) pH=5, (b) pH=7 and (c) pH=9.

Figure 13.

CF of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water at different pH values with initial value of IT=100 FAU for aluminum sulfate, papaya peel coagulant, and papaya seed coagulant at (a) pH=5, (b) pH=7 and (c) pH=9.

Figure 13.

CF of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water at different pH values with initial value of IT=100 FAU for aluminum sulfate, papaya peel coagulant, and papaya seed coagulant at (a) pH=5, (b) pH=7 and (c) pH=9.

Figure 14.

FTIR spectra of papaya peel coagulant.

Figure 14.

FTIR spectra of papaya peel coagulant.

Figure 15.

FTIR spectra of papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 15.

FTIR spectra of papaya seed coagulant.

Figure 16.

Sampling points in Manuel Avila Camacho dam (Valsequillo) in Puebla, Pue. México.

Figure 16.

Sampling points in Manuel Avila Camacho dam (Valsequillo) in Puebla, Pue. México.

Figure 17.

Results of the water treatment from the Valsequillo dam: (a) raw water; and after treatment with (b) aluminum sulfate; (c) papaya seed coagulant; and (d) papaya peel coagulant.

Figure 17.

Results of the water treatment from the Valsequillo dam: (a) raw water; and after treatment with (b) aluminum sulfate; (c) papaya seed coagulant; and (d) papaya peel coagulant.

Table 1.

Parameters of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water and levels.

Table 1.

Parameters of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water and levels.

| Input variable |

Notation |

Units |

Low level (-1) |

Medium level (0) |

High level (+1) |

| Initial turbidity |

IT |

FAU |

40 |

90 |

140 |

| Coagulant dosage |

CD |

ppm |

20 |

50 |

80 |

| pH |

pH |

|

5 |

7 |

9 |

Table 2.

Design matrix for coagulation process of synthetic surface water.

Table 2.

Design matrix for coagulation process of synthetic surface water.

| |

Parameters of the Coagulation Process |

| Experiment |

Initial Turbidity IT (FAU) |

Coagulant dosage

CD (ppm) |

pH |

| 1 |

90 |

50 |

7 |

| 2 |

90 |

80 |

5 |

| 3 |

90 |

50 |

5 |

| 4 |

140 |

50 |

9 |

| 5 |

40 |

50 |

5 |

| 6 |

140 |

50 |

5 |

| 7 |

90 |

20 |

9 |

| 8 |

40 |

50 |

9 |

| 9 |

90 |

50 |

9 |

| 10 |

90 |

80 |

9 |

| 11 |

140 |

80 |

7 |

| 12 |

40 |

20 |

7 |

| 13 |

90 |

20 |

5 |

| 14 |

140 |

20 |

7 |

| 15 |

40 |

80 |

7 |

Table 3.

Jar test results of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water with the coagulants aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed.

Table 3.

Jar test results of the coagulation process of synthetic surface water with the coagulants aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed.

| |

Outputs |

| |

Aluminum Sulfate |

Papaya peel |

Papaya seed |

| EXPERIMENT |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) |

Final turbidity FT (FAU) |

Total suspended solids TSS (mg/L) |

Characteristics of the floc CF (WI) |

| 1 |

18 |

14 |

6 |

17 |

17 |

10 |

21 |

13 |

6 |

| 2 |

7 |

15 |

6 |

18 |

17 |

8 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

| 3 |

4 |

10 |

8 |

14 |

15 |

8 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

| 4 |

18 |

19 |

6 |

2 |

16 |

10 |

19 |

28 |

6 |

| 5 |

3 |

8 |

6 |

22 |

12 |

10 |

12 |

23 |

6 |

| 6 |

14 |

16 |

2 |

22 |

47 |

6 |

21 |

22 |

4 |

| 7 |

16 |

23 |

6 |

35 |

47 |

6 |

6 |

1 |

8 |

| 8 |

2 |

8 |

8 |

25 |

11 |

10 |

15 |

23 |

6 |

| 9 |

9 |

17 |

8 |

28 |

37 |

8 |

21 |

18 |

6 |

| 10 |

5 |

15 |

8 |

29 |

37 |

8 |

19 |

21 |

8 |

| 11 |

10 |

16 |

4 |

16 |

38 |

10 |

36 |

36 |

6 |

| 12 |

5 |

14 |

6 |

21 |

7 |

10 |

18 |

16 |

6 |

| 13 |

16 |

9 |

8 |

12 |

14 |

8 |

3 |

5 |

8 |

| 14 |

13 |

22 |

6 |

12 |

25 |

10 |

26 |

31 |

6 |

| 15 |

4 |

11 |

6 |

28 |

15 |

10 |

15 |

18 |

6 |

Table 4.

Factors of the quadratic polynomials of the TF, TSS and CF response modeling of the treatment of synthetic surface water with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Table 4.

Factors of the quadratic polynomials of the TF, TSS and CF response modeling of the treatment of synthetic surface water with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

| |

FT (FAU) |

|

TSS (mg/L) |

|

CF (WI) |

| |

Papaya peel |

Papaya seed |

Aluminum sulfate |

|

Papaya peel |

Papaya seed |

Aluminum sulfate |

|

Papaya peel |

Papaya seed |

Aluminum sulfate |

| a1 |

31.3091 |

-101.797 |

-31.1236 |

b1 |

59.2165 |

25.5884 |

-22.9781 |

c1 |

-5.62815 |

18.5468 |

14.5525 |

| a2 |

-0.04655 |

-0.07433 |

0.138668 |

b2 |

-0.36183 |

-0.29648 |

0.171382 |

c2 |

0.040251 |

-0.19659 |

-0.092219 |

| a3 |

-11.6468 |

36.1297 |

7.65359 |

b3 |

-27.3304 |

8.9887 |

6.31391 |

c3 |

6.45544 |

-2.59667 |

-2.50787 |

| a4 |

0.507106 |

-0.30036 |

0.246193 |

b4 |

0.895681 |

-1.04993 |

0.0909228 |

c4 |

-0.16982 |

0.020056 |

0.0759597 |

| a5 |

0.004005 |

-0.00441 |

-0.001471 |

b5 |

0.005222 |

-0.0035 |

0.0023405 |

c5 |

-0.00075 |

0.001281 |

5.119E-07 |

| a6 |

-0.03395 |

0.056542 |

-0.007704 |

b6 |

-0.02261 |

0.0997456 |

-0.05779 |

c6 |

0.005549 |

0.008532 |

0.0163995 |

| a7 |

-0.00061 |

0.002215 |

-0.000414 |

b7 |

0.000769 |

0.0005044 |

-0.0005198 |

c7 |

1.18E-05 |

3.24E-06 |

-0.000339 |

| a8 |

1.39663 |

-2.57544 |

-0.578494 |

b8 |

2.61075 |

-0.977873 |

-0.210481 |

c8 |

-0.54785 |

0.137286 |

0.110931 |

| a9 |

-0.05251 |

-0.01234 |

0.0124483 |

b9 |

-0.06888 |

0.0150918 |

0.0079366 |

c9 |

0.011878 |

0.004975 |

0.0048158 |

| a10 |

-0.00115 |

0.002108 |

-0.001166 |

b10 |

-0.00111 |

0.0055889 |

-0.0002166 |

c10 |

0.000396 |

0.000332 |

-0.000633 |

Table 5.

Functional groups present in the papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Table 5.

Functional groups present in the papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Peak at wave numbers

(cm-1) |

Assignments |

527 – 1051 |

Galacturonic acid in peptic polysaccharides. Pyranose absorption vibrations |

1014 |

C6–O6H, C–O, C=O and C–C–O stretching, denoting phenols, alcohols, and esters |

1143 - 1233 |

Ether (R-O-R) and ring C-C bonds in pectin molecules. Peptic polysaccharides rich in galacturonic acid and Xylose that contains hemicellulosic polysaccharides |

1319 |

cellulose and hemicellulose |

1319 - 1376 |

Symmetrical stretching vibrations due to the COO- group of polygalacturonic acid |

1508 |

Carboxylic groups |

1618 |

presence of primary amide groups- protein content |

1618 - 1735 |

non-esterified and esterified carboxyl groups in pectin |

| 1735 |

C=O stretching vibration of groups such as carboxylic acids, aldehydes, acetyl, and ketones |

| 1992 – 2142 |

C=O stretching vibration of methyl ester |

2852 – 2919 |

aliphatic C-H stretching from carbonyl-containing (aldehydes) aromatic compounds |

2919 |

C-H stretching and CH2 asymmetrical stretching of alkane groups |

3272-3284 |

O-H and N-H stretching. Hydroxyl group in pectin |

Table 6.

Results of the water treatment from the Valsequillo dam with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

Table 6.

Results of the water treatment from the Valsequillo dam with aluminum sulfate, papaya peel and papaya seed coagulants.

| COAGULANT |

Optimal DC (ppm) |

TF (FAU) |

SST (mg/L) |

CF |

%TRE |

%TSSRE |

| Aluminum Sulfate |

110 |

54 |

59 |

6 |

78.14 |

79.00 |

| Papaya seed |

30 |

23 |

24 |

8 |

90.69 |

91.46 |

| Papaya peel |

60 |

76 |

75 |

6 |

69.23 |

73.30 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).