Submitted:

17 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

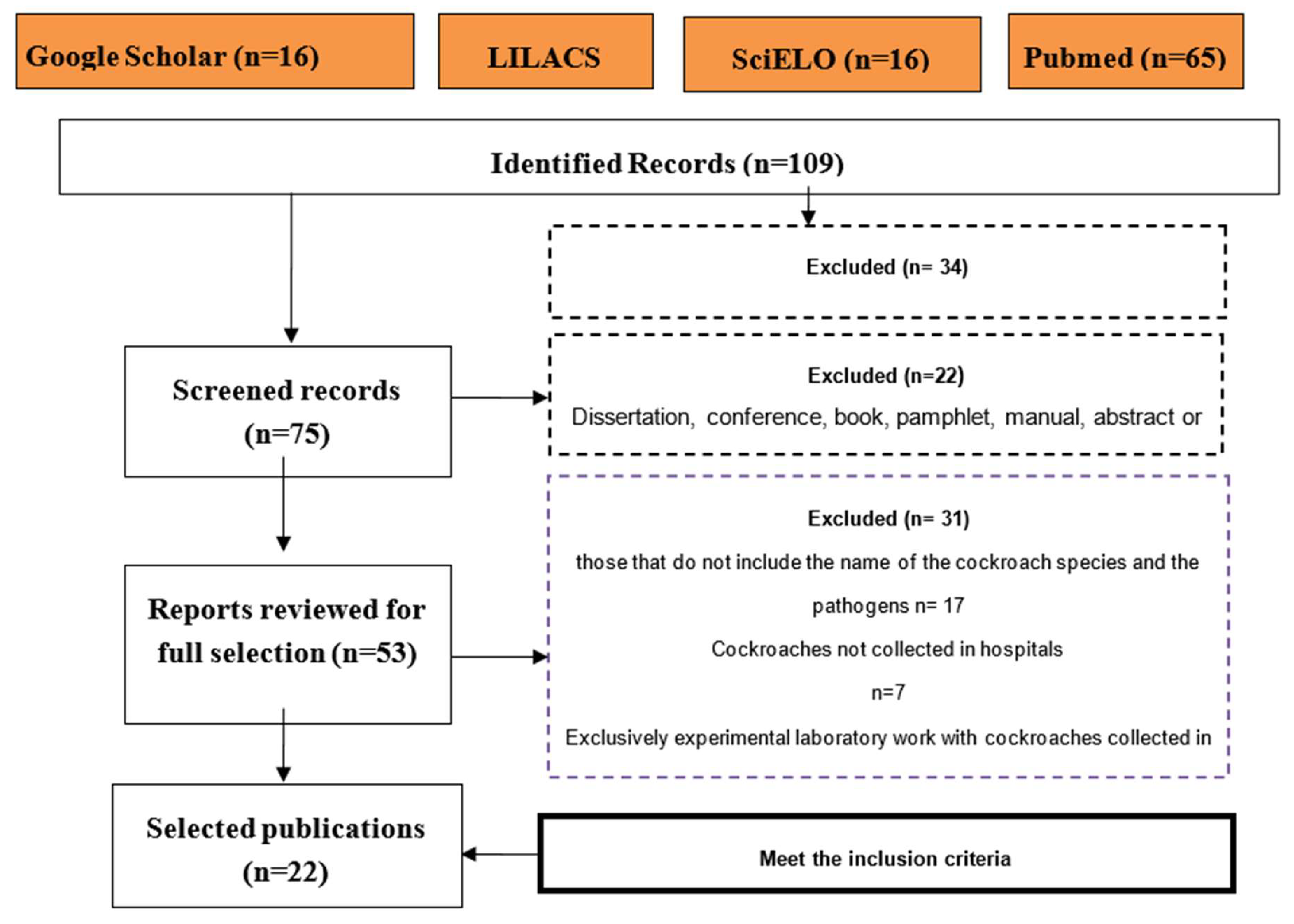

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Methodology Used in the Search for Relevant Studies

- The following keywords were established: cockroach, bacteria, hospital, pathogenic parasites, and antibiotic resistance. In order to optimize the retrieval of relevant information, the bibliographic citations of the articles examined were selected.

- The literature search was conducted using Google Scholar and electronic databases pertinent to the field of health, namely LILACS, the SciELO portal, and PubMed.

- The articles were identified based on their title, language, date of publication, and the time interval between January 2000 and April 2023 (the extreme years of the interval were included).

- Reports that met at least one of the exclusion criteria proposed by the authors of this study were excluded.

- The selected articles were found to meet all the inclusion criteria established by the authors of this work.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria for Studies

- Reports of isolation and identification of pathogenic organisms of medical importance from external or internal parts of cockroaches.

- Articles published in the period from January 1, 2000 to April 30, 2023. For the establishment of this period of time, we took into account what was described by Guzman et al.[6] who express that since 2000 there has been an increase in publications in Pubmed related to the topic of cockroaches and the pathogens identified from the body of these insects.

- Studies carried out with cockroaches collected in hospital environments, although the research also describes the capture of these insects in other places such as homes, hotels, markets, schools, or restaurants.

- Scientific reports from anywhere in the world that are published in the form of a thesis, scientific article or letter to the editor in English, Spanish or Portuguese.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria for Studies

- Articles in which the scientific name of the cockroach species collected is absent.

- Exclusively experimental research studies conducted in a laboratory setting on pathogens isolated from cockroaches collected in hospital settings.

- Publications that constitute review articles.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- Microsoft Office Excel 2007 version was used to present the results in tables and figures.

3. Results

3.1. Search for Information

3.2. Distribution of Articles by Continent and Country

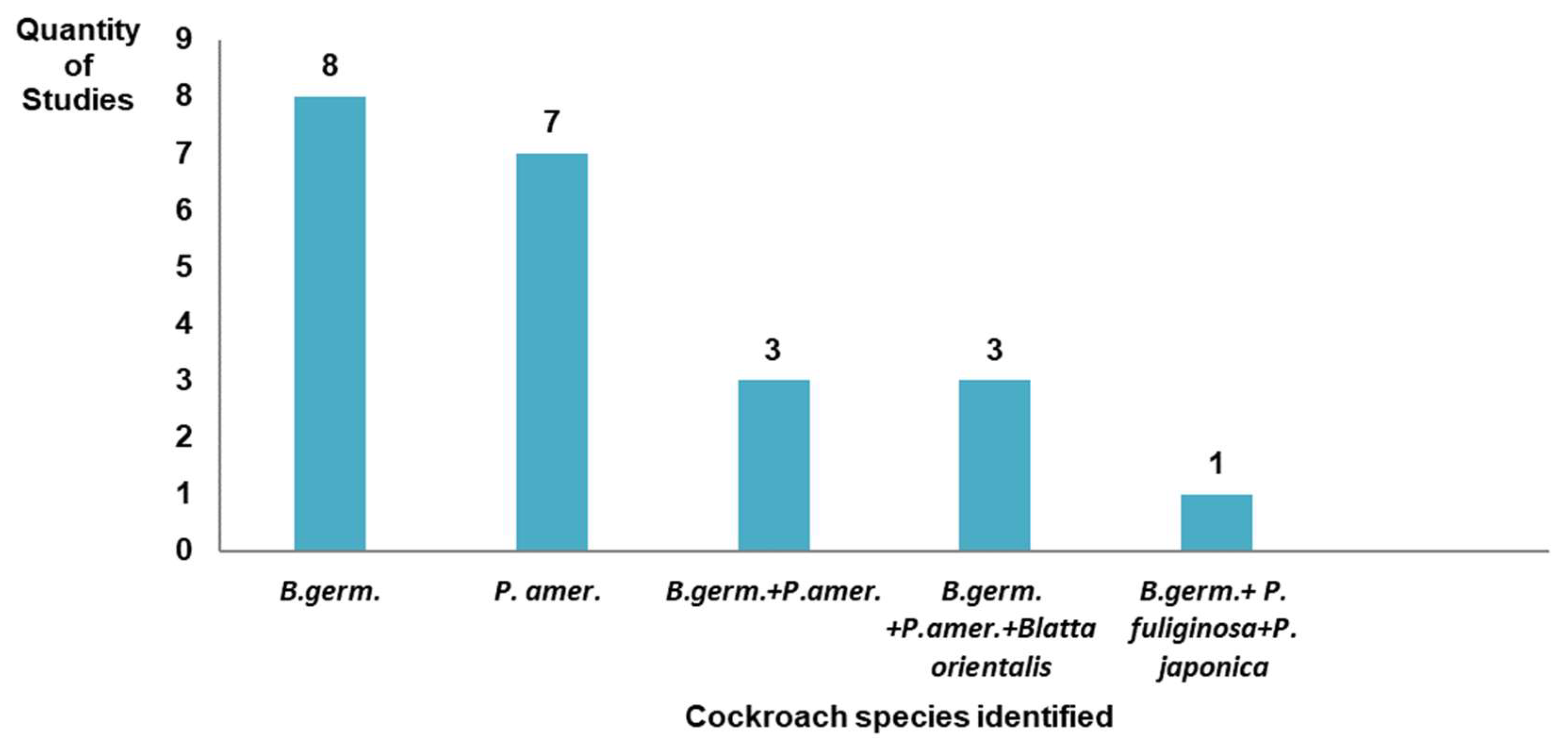

3.3. Cockroach Species Collected and Identified in the Studies Analyzed

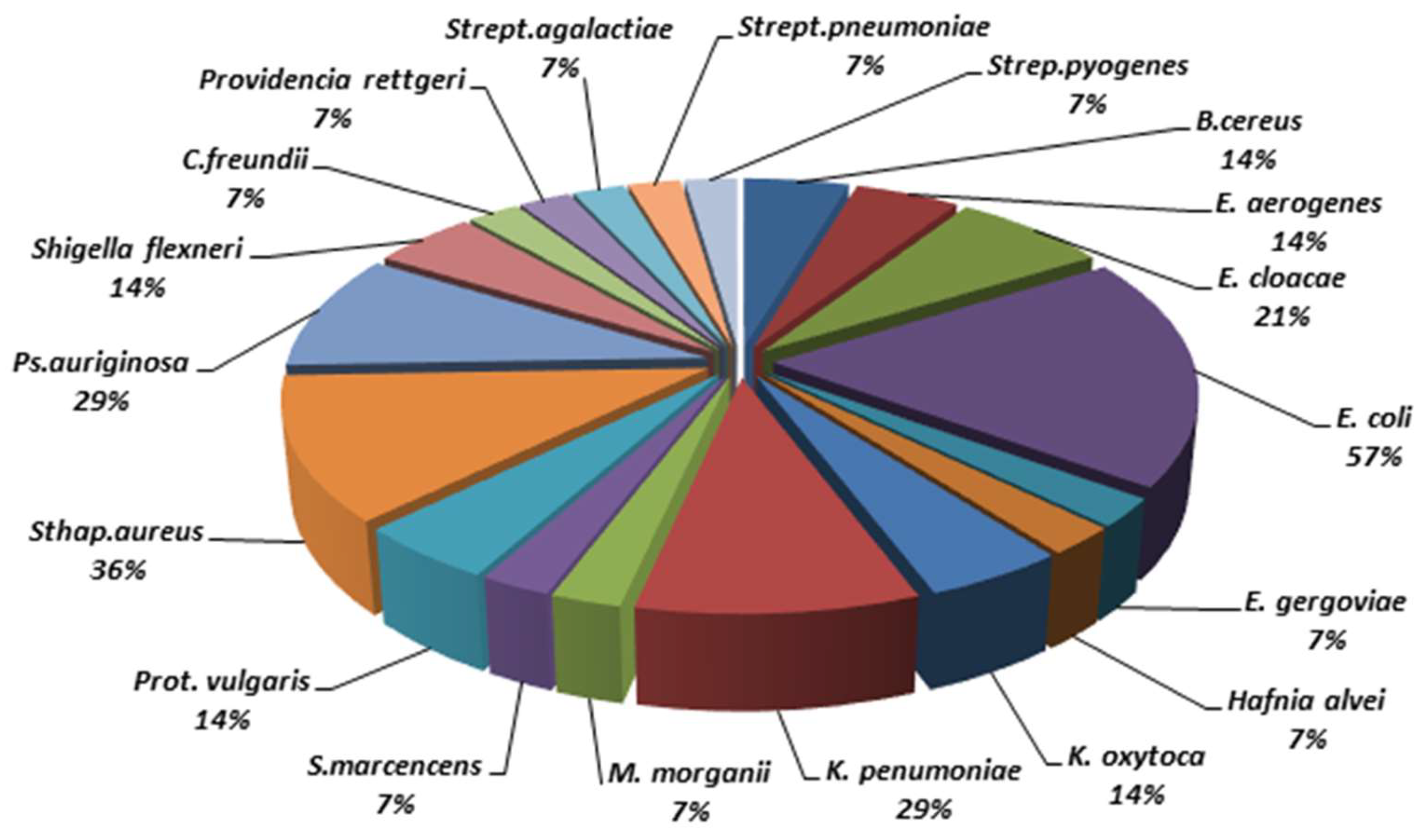

3.4. Microorganisms Isolated and Identified from Cockroaches Collected in Hospitals

3.5. Antibiotic Resistance and Mechanisms of Resistance in Bacteria Identified in Cockroaches

3.6. Methods Used in the Identification of Microorganisms Identified in Cockroaches

3.7. Methods Used to Detect Antibiotic Resistance and its Mechanisms in Bacteria Identified in Cockroaches

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cochran DG. Cockroaches their biology, distribution and control. World Health Organization, Communicable Diseases Prevention and Control and WHO Pesticide Evaluation Scheme [Internet]. 1999 [cited May 4, 2023]; (WHOPES)WHO/CDS/CPC/WHOPES/99.3:1-83. Avalaible in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Cochran DG. Blattodea. In: Resh HV, Cardé RT, editor. Encyclopedia of INSECTS [Internet]. 2a ed. California, Estados Unidos. 2009 [cited May 4, 2023];108-111. Avalaible in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Ponce G, Cantú PC, Flores A, Badii M, Barragán A, Zapata R, et al. Cucarachas: Biología e Importancia en Salud Pública. RESPYN [Internet]. 2005 [cited May 4, 2023];6 (3). Avalaible in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Majekodunmi A, HowardMT, ShahV.The perceived importance of cockroach infestation to social housing residents. J Environ Health Res. [Internet]. 2002 [cited May 4, 2023]; 1(2):27-34. Avalaible in: https://google.com.

- Atiokeng RJ, Tsila HG, Wabo J. Medically Important Parasites Carried by Cockroaches in Melong Subdivision, Littoral, Cameroon. J Parasitol. [Internet]. 2017 [cited May 4, 2023]. Avalaible in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Guzman J, Vilcinskas A. Bacteria associated with cockroaches: health risk or biotechnological opportunity? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol.[Internet].2020 [cited May 6, 2023]; 104:10369–10387. Avalaible in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Adenusi A, Akinyemi M, Akinsanya D. Domiciliary cockroaches as carriers of human intestinal parasites in lagos Metropoli, Southwest Nigeria: Implications for public health. J Arthropod-Borne Dis. [Internet].2018 [cited May 6, 2023]; 12(2): 141-151. Avalaible in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Nasirian H, Salehzadeh A. Control of Cockroaches (Blattaria) in Sewers: A Practical Approach Systematic Review. J Med Entomol. [Internet]. 2019 [cited May 6, 2023];56(1):181–191. Avalaible in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Maketon M, Hominchan A, Hotaka D. Control of American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) and German cockroach (Blattella germanica) by entomopathogenic nematodes. Rev Colomb Entomol. [Internet]. 2010 [cited May 6, 2023];6(2):249-253. Avalaible in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Concepción A. Estudio y evaluación de los patógenos de cucarachas (Insecta: Blattodea) urbanas en la Provincia de Buenos Aires, como potenciales agentes de control. [Tesis Doctoral en Internet]. Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional de La Plata; 2015 [cited May 7, 2023]. Avalaible in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Ramírez J. La cucaracha como vector de agentes patógenos. Bol of Sanit Panam. [Internet]. 1989 [cited May 7, 2023]; 107(1). Avalaible in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Talgi TY. Determinación de la presencia de ooquistes de Toxoplasma gondii en cucarachas Periplaneta americana que habitan en el Mercado Colón de la Ciudad de Guatemala. [Tesis de Grado en Internet]. Guatemala: Universidad de San Carlos; 2016 [cited May 7, 2023]. Avalaible in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Sramova H, Daniel M, Absolonova V, Dedicova D, Jedlickova Z, Lhotova H, et al. Epidemiological role of arthropods detectable in health facilities. J. Hosp.Infect. [Internet]. 1992 [cited May 7, 2023]; 20: 281-292. Avalaible in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Graczyk TK, Knight R, Tamang L. Mechanical transmission of human protozoan parasites by insects.Clin Microbiol Rev. [Internet]. 2005 [cited May 10, 2023];18 (1):128-132. Avalaible in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Moreano B Sh, Velásquez RA. Detección molecular por PCR de Giardia sp., Hymenolepis sp. y Entamoeba sp. en excreta de cucarachas de centro de abastos público en Cusco. [Tesis de Grado en Internet] Perú: Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco Facultad de Ciencias; 2018 [cited May 10, 2023]. . Available in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Camones M, Cabello AM. Perfil de susceptibilidad en bacterias colonizantes aisladas de cucarachas en un hospital de lima metropolitana. Rev Cient Alas Peruanas [Internet]. 2017 [cited May 19, 2023]; 3(2). Available in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Abdolmaleki Z, Mashak Z, Dehkordi FS. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antibiotic resistance in the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from hospital cockroaches. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control [Internet]. 2019 [citedad May 19, 2023]; 8:54. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Jaramillo GI, Pavas NC, Cárdenas JC, Gutiérrez P, Oliveros WA, Pinilla MA. Blattella germanica (Blattodea: Blattellidae) como potencial vector mecánico de Infecciones Asociadas a la Atención en Salud (IAAS) en un centro hospitalario de Villavicencio (Meta-Colombia). NOVA [Internet]. 2016 [cited May 19, 2023]: 19-25. Available in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Lemiech-Mirowska E, Kiersnowska ZM, Michałkiewicz M, Depta A, Marczak M. Nosocomial infections as one of the most important problems of the healthcare system. Ann Agric Environ Med. [Internet]. 2021 [cited May 23, 2023 ]; 28(3):361–366. Available in: https://www.aaem.pl.

- Xia J, Gao J, Tang W. Nosocomial infection and its molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. BioScience Trends. [Internet]. 2016 [cited May 23, 2023]; 10 (1):14-21. Available in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Hamu H, Debalke S, Zemene E, Birlie B, Mekonnen Z, Yewhalaw D. Isolation of Intestinal Parasites of Public Health Importance from Cockroaches (Blattella germanica) in Jimma Town Southwestern Ethiopia. J Parasitol Res. [Internet]. 2014 [cited May 22, 2023]. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Zarchi AA, Vatani H. A survey on species and prevalence rate of bacterial agents isolated from cockroaches in three Hospitals. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. [Internet]. 2009 [cited May 22, 2023];9(2):197–200. Available in: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Moges F, Esthetie S, Endris M, Huruy K, Muluye D, Feleke T, et al. Cockroaches as a Source of High Bacterial Pathogens with Multidrug Resistant Strains in Gondar Town, Ethiopia. Bio Med Res. Int. [Internet]. 2016 [cited May 22, 2023]. Available in: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Tamayo VR, Guevara AP, Cadena SA, Paz EA, Ruiz VA, Zambrano AK. Estudio de Revisión. Genes involucrados con resistencia antimicrobiana en hospitales del Ecuador. CAMbios. [Internet]. 2022 [cited May 22, 2023]; 21 (2): e863. Available in: https://revistahcam.iess.gob.ec/index.php/cambios/issue/archiv.

- Kebede B, Yihunie W, Abebe D, Tegegne BA, Belayneh. A Gram-negative bacteria isolates and their antibiotic-resistance patterns among pediatrics patients in Ethiopia: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med. [Internet]. 2022 [cited May 23, 2023]; 10:1–9. Available in.

- Arango A, López S, Vera D, Castellanos E, Rodríguez PH, Rodríguez MB. Epidemiología de las Infecciones Asociadas a la Asistencia Sanitaria. Acta Méd. Centro [Internet]. 2018 [cited May 23, 2023];12(3). Available in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Lupo A, Haenni M, Madec JY. Antimicrobial Resistance in Acinetobacter spp. and Pseudomonas spp. Microbiol. Spectr. [Internet]. 2018 [cited May 23, 2023]; 6(3). Available in. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. [Internet]. 2021 [cited May 23, 2023]; 372(71). Available in: http://www.bmj.com/.

- Países en vía de desarrollo. Datos Mundial.com [Internet]. [cited May 25, 2023]. Available in: https://www.datosmundial.com.

- Prado MA, Pimenta FC, Hayashid M, Souza MR, Pereira MS, Gir E. Enterobactérias isoladas de baratas (Periplaneta americana) capturadas em um hospital brasileiro. Pan American Journal of Public Health [Internet]. 2002 [cited May 25, 2023];11 (2). Available in: https://www.scielosp.org.

- Prado MA, Gir E, Pereira MS, Reis C, Pimienta FC. Profile of Antimicrobial Resistance of Bacteria Isolated from Cockroaches (Periplaneta americana) in a Brazilian Health Care Institution. BJID [Internet]. 2006 [cited May 25, 2023];10. Available in: https://www.scielosp.org.

- Elgderi RM, Ghenghesh KS, Berbash N. Carriage by the German cockroach (Blattella germanica) of multiple –antibiotic-resistant bacteria that are potentially pathogenic to humans, in hospitals and households in Tripoli, Libya. Annals Tropical Medicine. [Internet]. 2006 [cited May 26, 2023]; 100(1):55-62. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Tachbele E, Erku W, Gebre-Michael T, Ashenafi M. Cockroach-associated food-borne bacterial pathogens from some hospitals and restaurants in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Distribution and antibiograms. J Rural Health [Internet]. 2006 [cited May 26, 2023];5:34-41. Journal of Vector Borne Diseases: Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Salehzadeh A, Tavacolb P, Mahjub H. Bacterial, fungal and parasitic contamination of cockroaches in public hospitals of Hamadan, Iran. J Vector Borne Dis. [Internet]. 2007 [cited May 26, 2023]; 44:105–110. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Miranda RA, Silva JP. Enterobactérias isoladas de Periplaneta americana capturadas em um ambiente hospitalar. Ciência et Praxis [Internet]. 2008 [cited May 26, 2023];5(1). Available in: https://www.scielosp.org.

- Karimi AA, Vatani H. A survey on species and prevalence rate of bacterial agents isolated from cockoaches in three hospitals. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. [Internet]. 2009 [cited May 26, 2023];9(2):197-200. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Saitou K, Furuhata K, Kawakami Y, Fukuyama M. Isolation of Pseudomona aeruginosa from cockroaches captured in Hospitals in Japan, and their Antibiotic Susceptibility. Biocontrol Sci. [Internet]. 2009 [cited May 26, 2023]; 14(4):155-159. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Risco G, Díaz C, Fuentes O, Martínez MD, Fernández C, Cordoví R, et al. Blatella germanica as a possible cockroach vector of micro-organisms in a hospital. J Hosp Infec. [Internet]. 2010 [cited May 28, 2023];74(1):93-95. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Tilahun B, Worku B, Tachbele E, Terefe S, Kloos H, Legesse W. High load of multi-drug resistant nosocomial neonatal pathogens carried by cockroaches in a neonatal intensive care unit at Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Antimicrob. Resist Infect Control [Internet]. 2009 [cited May 25, 2023]; 1:12. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Tetteh-Quarcoo PB, Donkor ES, Attah SK, Duedu KO, Afutu E, Boamah I, et al. Microbial carriage of cockroaches at a tertiary care hospital in Ghana. Environ Health Insights. [Internet]. 2013 [cited May 25, 2023]; 7:59-66. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Motevali SF, Aghili SR, Gholami Sh, Salmanian B, Nikokar SH, Khangolzadeh M, et al. Isolation of medically important fungi from cockroaches trapped at hospitals of Sari, Iran. Bull Env Pharmacol Life Sci. [Internet]. 2014 [cited May 25, 2023]:29-36. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Menasria T, Moussa F, El-Hamza S, Tine S, Megri R, Chenchouni H. Bacterial load of German cockroach (Blattella germanica) found in hospital environment. Pathog Glob. Health [Internet]. 2014 [cited May 25, 2023]; 108 (39):141-147. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Suresh K, Mathiyazhagan N, Selvam R. Cockroach-associated food-borne bacterial pathogens from some hospitals and restaurants in Hosur, Tamilnadu: Distribution and antibiograms. Mesop Environ J. [Internet]. 2015 [cited May 28, 2023]; 2(1):87-99. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Cazorla D, Morales P, Navas P. Aislamiento de parásitos intestinales en la cucaracha americana (Periplaneta americana) en Coro, estado Falcón, Venezuela. Boletín de Malariología y Salud Ambiental. [Internet]. 2015 [cited May 28, 2023];55(2):184-19. Available in: https://www.scielosp.org.

- Ikechukwu O, Ifeanyichukwu I, Chika E, Okapi E, Ogbonnaya O. Cockroaches (Periplaneta americana) as possible reservoirs of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing pathogenic bacteria. Int J Res. Biosciences, [Internet]. 2017 [cited May 29, 2023]; 6(3), 41-49. Available in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Nazari S, Habibi F, Nazari S, Hosseini SM, Nazari M. Bacterial contamination of external surface of cockroaches and their antibiotic resistance in hospitals of Hamadan, Iran. J Postgrad. Med Inst [Internet]. 2020 [cited May 29, 2023];34(2):104-9. Available in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Khodabandeh M, Shirani-Bidabadi L, Madani M, Zahraei-Ramazani A. Study on Periplaneta americana (Blattodea: Blattidae) Fungal Infections in Hospital Sewer System, Esfahan City, Iran, 2017. J Pathog. [Internet]. 2020 [cited May 29, 2023]; 34(2). Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Chehelgerdi M, Reza Ranjbar R. Virulence factors and antibiotic resistance properties of Streptococcus species isolated from hospital cockroaches. Biotech [Internet]. 2021 [cited May 29, 2023];11:321. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Motevalli-Haghi SF, dian ASh, Nakhaei M, Faridnia R, Dehghan O, Shafaroudi M M. First report of Lophomonas spp. in German cockroaches (Blattella germanica) trapped in hospitals, northern Iran. J Parasit Dis [Internet]. 2021 [cited May 29, 2023]; 45(4):937–943. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Landolsi S, Selmi R, Hadjadj L, Haj AB, Romdhane KB, Messadi L, et al. First Report of Extended-Spectrum b-Lactamase (blaCTX-M1) and Colistin Resistance Gene mcr-1 in E. coli of Lineage ST648 from Cockroaches in Tunisia. Microbiol Spectr. [Internet]. 2022 [cited May 29, 2023];10(2). Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Castellano MJ, Perozo-Mena AJ. Mecanismos de resistencia a antibióticos ß-lactámicos en Staphylococcus aureus. Kasmera [Internet]. 2010 [cited May 29, 2023]; 38(1): 18 – 35. Available in: http://ve.scielo.org.

- Galarce NE. Detección de tres genes de resistencia a antimicrobianos en cepas de Staphylococcus coagulasa positivas aisladas desde gatos [Tesis de Grado en Internet] Chile: Universidad de Chile: Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias y Pecuarias. Escuela de Ciencias Veterinarias. 2011 [cited May 29, 2023]. Available in: https://repositorio.uchile.cl.

- Ugarte RG, Olivo JM, Corso A, Pasteran F, Albornoz E, Sahuanay ZP. Resistencia a colistín mediado por el gen mcr-1 identifcado en cepas de Escherichia coli y Klebsiella pneumoniae. Primeros reportes en el Perú. An Fac med. [Internet]. 2018 [cited May 29, 2023]; 79(3):213-7. Available in:. [CrossRef]

- Khamesipour F, Lankarani KB, Honarvar B, Kwenti TE. A systematic review of human pathogens carried by the housefly (Musca domestica L.). BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2018 [cited May 29, 2023]; 18:1049. Available in. [CrossRef]

- Molewa ML, Barnard T, Naicker N. A potential role of cockroaches in the transmission of pathogenic bacteria with antibiotic resistance: A scoping review. J Infect Dev Ctries. [Internet]. 2022 [cited May 30, 2023]; 16(11):1671-1678. Available in:. [CrossRef]

- Patel A, Jenkins M, Rhoden K, Barnes AN. A Systematic Review of Zoonotic Enteric Parasites Carried by Flies, Cockroaches, and Dung Beetles. Pathogens [Internet]. 2022 [cited May 30, 2023]; 11: 90. Available in. [CrossRef]

- Donkor ES. Nosocomial Pathogens: An In-Depth Analysis of the Vectorial Potential of Cockroaches. Trop Med Infect Dis. [Internet]. 2019 [cited May 30, 2023]; 4:14. Available in:. [CrossRef]

- Lucha contra vectores y plagas urbanas [Internet]. Ginebra, Suiza. Organización Mundial de la Salud; 1988 [cited May 30, 2023].767. Available in: http://apps.who.int/iris/.

- Le Guyader A, Rivault C, Chaperon J. Microbial organisms carried by brown banded cockroaches in relation to their spatial distribution in a hospital. Epidemiol Infect. [Internet].1989 [cited May 25, 2023];102: 485–492. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Gliniewicz A, Czajka E, Laudy AE, Kochman M, Grzegorzak K, Ziółkowska K, et al. German Cockroaches (Blattella GermanicaL.) as a potential source of pathogens causing nosocomialinfections. Indoor Built Environ [Internet] 2003 [cited May 30, 2023]; 12: 55–60. Available in: https://www.researchgate.net.

- Ejimadu LC, Goselle ON, Ahmadu YM, James-Rugu NN. Specialization of Periplaneta americana (American Cockroach) and Blattella Germanica (German cockroach) Towards Intestinal Parasites: A Public Health Concern. Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences [Internet]. 2016 [cited May 30, 2023]; 10(6). Available in: https://www.iosrjournals.org.

- Kramer A, Schwebke I, Kamp G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surface? A systematic review. BMC Infections Disease [Internet]. 2006 [cited May 30, 2023]; 6:130. Available in: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Leralta C. Infecciones nosocomiales, importancia de Pseudomonas aeruginosa. [Bachelor Thesis [Internet]. Madrid: Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad Complutense. 2017 [cited May 30, 2023]. Available in: https://eprints.ucm.es.

- Xia J, Gao J, Tang W. Nosocomial infection and its molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. BioScience Trends [Internet]. 2016 [cited May 30, 2023]; 10(1):14-21. Available in:. [CrossRef]

- Ortega LM, Duque M, Valdés J, Verdasquera D. Sepsis grave en la Unidad de Terapia Intensiva del Instituto de Medicina Tropical “Pedro Kourí". RCSP. [Internet]. 2018 [cited May 31, 2023]; 44(2):213-223. Available in: http://scielo.sld.cu.

- Tolera M, Abate D, Dheresa M, Marami D. Bacterial Nosocomial Infections and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Pattern among Patients Admitted at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia. Advances in Medicine [Internet]. 2018 [cited May 31, 2023]. Available in:. [CrossRef]

- De Florio L, Riva E, Giona A, Dedej E, Fogolari M, Cella E, et al. MALDI-TOF MS Identification and Clustering Applied to Enterobacter Species in Nosocomial Setting. Front Microbiology [Internet]. 2018 [cited May 31, 2023];19. Available in: https://www.frontiersin.org.

- Camargo-Assis F, Máttar S, González M. Lophomonas blattarum parásito de cucarachas que causa neumonías infrecuentes en humanos. Rev. MVZ Cordoba [Internet]. 2020 [cited May 31, 2023]; 25(1):e1948. Available in:. [CrossRef]

- Boucher H, Talbot G, Bradley J, Edwards J, Gilbert D, Rice L, et al. Bad Bugs, No Drugs: No ESKAPE!. An Update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infec Dis. [Internet]. 2009 [cited , 2023]; 48:112. [CrossRef]

- Pérez RM. Resistencia bacteriana a antimicrobianos: su importancia en la toma de decisiones en la práctica diaria. Inf Ter Sist Nac Salud. [Internet]. 1998 [cited May 31, 2023]; 22(3): 57-67. Available in: https://scholar.google.com.

- Garza-Ramos U, Silva-Sánchez J, Martínez-Romero E. Genética y genómica enfocadas en el estudio de la resistencia bacteriana. Salud Pública de México. [Internet]. 2009 [cited May 31, 2023]; 53(3). Available in: https://scholar.google.com.

| Author, year, reference number | Country | Microorganisms isolated and identified from cockroaches | Methods used in the identification of microorganisms, determination of antimicrobial susceptibility profile and antibiotic resistance mechanisms. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prado et al., 2002 (30) |

Brazil | Bacteria: E. coli, K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae, S. marcescens, H. alvei, E. gegorviae, Serratia spp., K. oxytoca, P. vulgaris, Morganella morganii |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), Gram stain (TG) and conventional biochemical tests (CBT). PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer). |

| Marinésia et al., 2006 (31) | Brazil |

Bacteria: S. coagulase-negative, E. aerogenes, S. marcescens, H. alvei, E. cloacae, E. gergoviae, Serratia spp. Fungi: Yeast and Filamentous fungi |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential) and PBC. PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer). IM (Fungi): Seeding in Sabouraud agar medium and observation of macro and microscopic morphological characteristics of the sample. |

| Elgderi et al., 2006 (32) |

Libya | Bacteria: E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, K. ornithinolytica, E. cloacae, E. aerogenes, Pantoea sp., C. freundii, C. braakii, C. youngae, C. amalonaticu, S. marcescens, S. liquefaciens, P. mirabilis, P. vulgaris, M. morganii, H. alvei, Buttiauxlla agrestis, Aeromonas hydrophila, Aeromonas caviae, P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter sp., Streptococcus.sp. | IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), PBC y API. PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer). |

| Tachbele et al., 2006 (33) |

Ethiopia | Bacteria: Shigella flexneri, E. coli O15717, S. aureus, Bacillus cereus. |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG, PBC and Serological Tests. PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer). |

| Salehzadeh et al., 2007 (34) |

Iran | Bacterias: E. coli, Haemophilus spp., S. hemolítico group A y B. Fungi: Candida spp., Mucor spp., Aspergillus niger, Rhizopus spp., Penicillium spp., Aspergillus fumigans Helminths: Enterobius vermicularis, Ascaris spp. |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG y PBC. PSA (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential) (Kirby Bauer). IM (Fungi): Seeding in Sabouraud agar medium and observation of macro and microscopic morphological characteristics of the sample. IM (Helminths): Direct parasitologic methods (saline and Lugol) and observation of the sample under the light microscope. |

| Aparecida et al., 2008 (35) |

Brazil | Bacteria: Salmonella spp., E. coli, C. freundii, H. alvei, S. aureus, E. aerogenes, Serratia spp. |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG y PBC. PSA (Bacteria): the method used is not shown. |

| Karimi et al., 2009 (36) |

Iran | Bacteria: E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, E. cloaceae, E. aerogenes, P. mirabilis, P. vulgaris, M. morganii, C. freundii. C. diversus, Edwardsiellae trada, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. saprophyticus, S. group D, P. eruginosa | IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG y PBC. |

| Saitou et al., 2009 (37) |

Japan | Bacteria: P. aeruginosa | IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), PBC y API. PSA (Bacteria): Using the Etest.MRA: PCR. |

| Risco et al., 2010 (38) | Cuba |

Bacteria: Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, Alcaligenes faecalis, C. diversus, C. freundii, E. aerogenes, E. agglomerans, E. cloacae, Enterococcus sp., E. coli, K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, P. vulgaris, P. stuartii, P. aeruginosa, S. marcescens, S. aureus, S. epidermidis. Fungi: Aspergillus spp., Mucor spp., Rizopus spp. |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG y PBC. IM (Fungi): Seeding in Sabouraud agar medium and observation of macro and microscopic morphological characteristics of the sample. |

| Tilahun et al., 2012 (39) |

Ethiopia | Bacteria: K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae, C. diversus, P. aeruginosa, Providencia rettgeri, K. ozaenae, E. aerogenes, S. aureus, E. coli, Shigella flexneri, Enterococcus faecalis. |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG y PBC. PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer). |

| Tetteh-Quarcoo et al., 2013 (40) |

Ghana |

Bact eria: K. pneumoniae, E. coli, P. vulgaris, C. ferundii, E. cloacae, P. aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, K. oxytoca. Helminths: Ancylostoma duodenale, Taenia spp. Virus: Rotavirus |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG y PBC. IM (Helminths): Staining of the sample with lugol and observation under a light microscope. IM (Rotavirus): ELISA PSA (Bacterias): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer). |

| Motevali et al., 2014 (41) |

Iran | Fungi: Candida spp., Rhodotorula spp., Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp., Penicillium spp. Geotrichum spp., Alternaria spp., Cladosporium spp., Trichoderma spp., Mucor spp., Chrysosporium spp. | IM (Fungi): Seeding in Sabouraud's dextrose agar with chloramphenicol, tube germination test (yeast) and observation of macro and microscopic morphological characteristics of the sample. . |

| Menasria et al., 2014 (42) |

Argelia | Bacteria: S. aureus, C. erundii, E. cloacae, E. aerogenes, K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens. | IM (Bacteria): PBC y API. |

| Suresh et al., 2015 (43) |

India | Bacteria: Salmonella B, Salmonella D, Salmonella E, Shigella B, E. coli, S. aureus. |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG, PBC y Pruebas Serológicas. PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer). |

| Cazorla et al., 2015 (44) |

Venezuela | Protozoans: Entamoeba blattae, Nycthoterus ovalis, Leptomonas spp., Cyclospora spp., Entamoeba coli, Cystoisospora spp., Lophomonas blattarum, Lophomonas striata Helminths: Enterobius vermicularis, Thelastoma spp., Hammerschmidtiella spp. |

IM (Protozoans and Helminths): Direct parasitologic methods: samples paired in saline, Lugol stained, then light microscoped. |

|

Ikechukwu et al., 2017 (45) |

Nigeria | Bacteria: E. coli, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp. |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG y PBC. PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer). MRA (Bacteria): DDST |

| Abdolmalek et al., 2017 (17) |

Iran | Bacteria: S. aureus |

IM (Bacterias): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG y PBC. PSA (Bacterias): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer) and PCR. MRA (Bacterias): PCR |

| Nazari et al., 2020 (46) |

Iran | Bacteria: E. coli, S. coagulasa-negativa, Proteus spp., Enterococcus spp., Micrococcus spp., Pseudomona spp., Serratia spp.,Streptococcus.B, Streptococcus A, S. aureus. |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG y PBC. PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer) |

| Khodabandeh et al., 2020 (47) |

Iran | Fungi:Aspergillus niger, Rhizopus spp., Penicillium spp., Mucor spp., Candida glabrata, Candida krusei | IM (Protozoans): Seeding in different culture media; observation of macro and microscopic morphological characteristics of the sample. |

| Chehelgerdi et al., 2021 (48) |

Iran | Bacteria: S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae |

IM (Bacterias): Seeding in culture media (general and differential), TG, PBC y PCR. PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer) and PCR. MRA (Bacteria): PCR |

| Farzad et al., 2021 (49) |

Iran | Protozoans: Gregarina sp., Lophomonas blattarum. Entamoeba sp. Blastocystis sp. Nyctotherus sp. | IM (Protozoans): Direct parasitologic methods: samples paired in saline, Lugol stained, then light microscoped. |

| Landolsi et al., 2022 (50) |

Tunisia | Bacteria: K. pneumoniae, E. coli, E. cloacae, C. sedlaki |

IM (Bacteria): Seeding in different culture media and mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF). PSA (Bacteria): Disc Diffusion Method (Kirby Bauer) and PCR. MRA (Bacteria): DDST and Real Time PCR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).