1. Introduction

Food safety is ensuring innocuousness in the products being consumed by populations. In more recent years, it has become a major health concern as it is what guarantees healthy populations. The development of Next Generation Sequencing technologies has revolutionized the analysis of food matrices and helped in the creation of safety applications for public health worldwide [

1]. Metagenomics is a branch of genomics that focuses on the direct analysis of whole genomes contained within a sample and it has reduced the need for culture-dependent techniques [

2]. In food safety and quality, this is particularly helpful as it aids in the detection and management of foodborne pathogens and spoilage microorganisms [

3,

4]. Metagenomics has contributed to the understanding of microbial diversity as it offers a thorough analysis of the bacterial consortia, mycobiome, and virome present in food products. In the same way, it can provide information on the presence and abundance of genes, whether it’d be virulence genes or those involved in spoilage activities [

4].

Despite the significant advancements in metagenomics, several challenges remain in its application to food analysis. One of the primary problems is the lack of bioinformatics expertise and sophisticated tools in industry and regulators. Another one being that live and dead organisms cannot be distinguished [

3]. Addressing these obstacles will be essential for the widespread adoption of these technologies in the food industry. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the capabilities and applications of metagenomics as an advanced meat analysis technique, with the goal of unlocking new possibilities for the future of food safety.

2. Metagenomics of Different Types of Edible Products

Metagenomics has been widely used in the food industry, from its applications for food safety and spoilage prevention to its use in food authentication and the study of the microbial composition un probiotics and fermented foods. Metabarcoding (16S rRNA, ITS, 26S rRNA) and shotgun sequencing has been primarily used to track contamination in food, detect pathogens, spoilage, and traceability, however, these same techniques have been used to study the role and diversity of microorganisms in different food groups [

3]. The use of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) has been used, especially in the assessment of microbial consortia used for fermentation or as probiotics using amplified marker-genes from genomic DNA or the identification of gene expression through RNA sequencing [

5].

2.1. Fresh Produce

Fresh produce, including fruits and vegetables, are an essential part of the human diet and known to harbor large bacterial populations [

6,

7]. Despite being a major source of nutrients and a balanced diet, since it is often consumed raw, fresh produce can cause widespread foodborne outbreaks [

8]. It has been shown that the microbiota influences the development and prevention of allergic diseases by modulating innate and acquired immune responses via various axes, including the gut–lung axis and the gut–skin axis [

9]. Common microbial spoilage agents of fruits and vegetables have been identified from the genera

Erwinia,

Pectobacterium,

Xanthomonas,

Listeria and

Pseudomonas [

10].

Studies related to the metagenomics of fresh fruits and vegetables microbiome are still scarce. Nevertheless, previous studies have proven the effect of refrigeration temperatures on the microbiome [

11]. The microbiomes of fresh fruits and vegetables share common members such as

Enterobacterales,

Burkholderiales, and

Lactobacillales [

12]. Studies using 16S rRNA gene amplicon HTS have shown how leaf microbiome can be influenced by season, irrigation, soil type, and other factors [

13]. [

14] demonstrated using Illumina 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing that the bacterial community composition changes during cold storage (8°C) of ready-to-eat (RTE) baby spinach and mixed-ingredient salads, with Pseudomonadales (primarily the genus

Pseudomonas) being the most abundant high-level taxonomic group across samples.

[

4] demonstrated that fresh produce harbor complex bacterial and fungal communities, dominated by the phyla

Bacteroidetes/

Proteobacteria and

Ascomycota/

Basidiomycota, respectively, with vegetables leaf morphology and type of edible fraction of fruits exerting the highest influence. This result is largely consistent with those found in previous studies.

Ascomycota and

Basidiomycota have been consistently identified as the prevailing phyla on grapes, tomatoes, cherries, and wild grasses [

15,

16,

17] whereas

Bacteroidetes and

Proteobacteria have been predominant on lettuce [

7]. The researchers deduced that the reduced diversity within the

Enterobacteriaceae family in fruits indicates that distinct interactions between vegetables and bacteria, potentially influenced by inherent factors [

18], may contribute to variations in the abundance of specific taxa, distinguishing different types of vegetables.

Metagenomic sequencing has also been used to identify functional traits associated with microbiota to understand how different management practices influence taxonomic diversification within epiphytic microbes of fresh produce. In the two separate studies of apple fruit, there have been reported high fungal and bacterial diversity, with a higher portion of fungal sequences [

19,

20]. The phylum

Ascomycota prevailed among fungi, while

Bacteroides and

Proteobacteria were dominant in the bacterial population. The use of shotgun metagenomic by [

20] revealed a functional shift in the microbiota of the fruit depending on the management practice. The functional analysis of the organic orchard revealed a higher enzymatic activity of the biosynthetic pathways related to plant defense mechanisms, such as the alkaloid and aromatic amino acid pathway, due to the absence of synthetic pesticides. On the other hand, the results of the conventional sites demonstrated greater activity and abundance of antibiotic-related metabolic pathways. The influence of crop management has also been seen in grapes, with the study of epiphytic and endophytic microbial communities of the phyllosphere from conventionally and organically managed grapevines. The research showed that structure and function of fungal community was affected by its management, while it had no significant effect on the bacterial community [

21]. In organic vineyards, the fungus,

Aureobasidium pullulans, demonstrated its potential as a biocontrol agent due to its antagonistic action against several fungal pathogens.

Researchers from recent years suggest that the microbiota and mycobiota of fresh produce are characterized by high biodiversity whose composition is extremely sensitive to the product. While the type of edible fraction and leaf morphology have been determined as key factors in the growth of specific microbial communities, the lack of information about the specific handling, washing, transport, and storage process prevents a complete assessment of microbial contamination. The association of fruit pathogens with specific metabolites using metagenomic data enhances the understanding of the microbiotas’ functional impact, which can guide targeted manipulations to apply specific conditions and/or trophic interactions to obtain the desired function within the community. It is crucial to comprehend the intricate microbial ecosystem unique to each product to implement targeted control measures during harvesting, handling, and distribution to the end consumer. Therefore, researchers and the food industry must collaboratively invest more effort in exploring the biodiversity and specific microbial communities of products to develop and validate these control measures.

2.2. Poultry Products and Meat

The safety of meat and poultry has become a major concern in the commercial food industry. The increase in apprehensiveness is due to several factors, including alterations in animal production, processing, and distribution methods; expanded international trade; a global increase in meat consumption; evolving consumer preferences and consumption habits, such as a preference for minimally processed foods; a higher number of consumers susceptible to infection; and increased consumer interest, awareness, and scrutiny [

22]. Through the development of next generation sequencing (NGS), safety and quality studies are not only using shotgun metagenomic techniques to identify specific pathogenic bacteria but are beginning to analyze the entire community of organisms in an environment. Currently the focus of metagenomic research, with respect to meat and poultry, has primarily been geared towards the detection and reduction of pathogenic organisms, as well as the development of safety applications for public health [

1].

Metagenomic analysis has been applied to detect bacteria causing food spoilage and pathogenic bacteria on processing surfaces and additionally, it provides a valuable capability for exploring the simultaneous presence of organisms [

23]. This analysis proves beneficial in managing pathogens and spoilage organisms as it allows the identification of organisms whose abundance correlates, either positively or negatively, with the pathogens or spoilage organisms of interest. The application of metagenomics extends beyond product food safety and abattoir sanitation. Many researchers have directed their efforts towards utilizing metagenomics to identify potential targets for influencing the microbiome of food animals before slaughter. The objectives of such studies include reducing pathogen levels within animals, modifying growth status, mitigating undesired outcomes like liver abscesses in cattle, and manipulating the nutrient profile of the produced meat.

2.2.1. Poultry Products and Meat

Poultry meat is characterized by high-quality proteins, vitamins, and essential minerals crucial for human nutrition [

24]. The multiple steps involved in poultry meat production and commercial egg industry, from breeder flocks and hatcheries to commercial layer and broiler flocks, increase the risk of microbial contamination.

In poultry farms, the combination of bedding material, chicken excrement, and feathers appears to play a crucial role in pathogen development, posing a threat to the food chain. Most studies centered on bacterial contamination of poultry production have frequently reported

Salmonella sp. and

Campylobacter sp. [

25]. The gastrointestinal tracts of poultry are major reservoirs for

Salmonella and

Campylobacter, which explains why these two organisms pose a significant public health risk in poultry-based food products [

26].

Microbial transmission can occur through various routes. Chicks are highly susceptible to

Salmonella sp. infection, leading to microbial colonization via vertical transmission or horizontal transmission [

27]. Horizontal transmission can occur through contaminated hatcheries, cloacal infection, transportation equipment, feed, bedding, air, unclean facilities, and vectors. The presence of bacterial endotoxins in poultry aerosols has been demonstrated, with airborne bacteria and their metabolites increasing significantly during a chicken’s growth [

28]. Dominant spoilage poultry meat bacteria include species such as

Pseudomonas spp.,

Bacillus spp., Crude

Typhimurium spp.,

Schwartzella spp., and

Aeromonas spp. which typically constitute the primary communities in cold meat and poultry packed under aerobic conditions. After 4 days at 8°C,

Pseudomonas fluorescens,

Aeromonas salmonicida, and

Serratia liquefaciens caused proteolytic activity in sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar proteins in poultry meat [

29]. [

30] demonstrated that, alongside

Salmonella sp.,

Campylobacter sp.,

Staphylococci sp.,

E. coli,

Enterococci, and

Listeria sp., were also frequently observed.

Listeria sp. outbreaks, specially, poses a significant threat, leading to various diseases in children, pregnant women, immune-compromised individuals, and the elderly.

The practice of antibiotics remains widespread for both prophylactic and curative purposes in animal breeding and food production. The issue of antibiotic residues in animal products, groundwater, soil, and feed has generated global concern and continues to do so, leading to significant costs associated with combating antibiotic resistance [

31]. In recent years, the deliberate elimination of antibiotics for therapeutic purposes in food animals has introduced additional complexities to bird management that has prompted the search for antibiotic alternatives [

32]. As a result, various feed additives, including probiotics, prebiotics, phytogenics, and chemicals like organic acids, have been incorporated into the poultry production sector [

33]. Unregulated exposure of animals to antimicrobial drugs (AMD) is implicated in the development of resistant infections in humans [

34] and contributes to the ongoing issue of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) across bacterial species. The mechanisms enabling resistance are varied, encompassing diverse genes, but the prevailing theory suggests that the spread of AMR is facilitated by the contamination of meat during the slaughter and harvesting stages, with antibiotic-resistant bacteria originating from the hide and gastrointestinal tracts of cattle [

35].

Besides identifying pathogenic microbes, metagenomic analysis has been extensively applied to study chicken gut microbiota for improving metabolism and health. [

36] utilized metagenomic assembled genomes (MAGs) from chicken gastrointestinal tract (GIT) samples, with detailed annotation of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) and genes involved in short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) production, to study how the metabolisms performed differently according to age. The investigation identified six phyla (

Firmicutes,

Proteobacteria,

Bacteroidota,

Verrucomicrobiota,

Actinobacteriota, and

Cyanobacteria), which corroborated previous results through different experimental approaches [

37,

38] and observed an increase in microbiome diversity which is attributed to developmental changes in the chicken GIT, changes in the diet, and even the development of the immune system. Significant changes in the composition of the gut microbiome were observed over time that reflected a change in biosynthetic pathways.

Faecalibacterium and

Clostridium, for instance, known for carrying enzymes necessary for butyrate production present from early development stages [

39], prove to colonize the intestine in the early on. Additionally, the research revealed significant correlations between specific bacteria and groups of CAZenzymes that indicate a division in the ability to digest different carbohydrates.

Another focus of metagenomic studies in poultry is chicken gut antibiotic resistomes and microbiomes, due to its threat to human and animal health worldwide. Antibiotic resistance is a global threat to public health and food safety and is currently the cause of thousands of deaths yearly [

40,

41]. The horizontal gene transfer (HGT) allows bacteria from various ecological niches to share genes and poses a threat in the dissemination and evolution of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and drug-resistant bacteria [

42]. In the intestinal microbiomes of poultry gut a significant number of ARGs have been identified [

43]. [

44] found significant differences in the composition of microbial communities and ARGs among six types of indigenous Chinese, yellow-feathered chickens. 989 ARGs conferring tetracycline, multidrug, and aminoglycoside resistance were identified, which represented more than 80% of the fecal resistomes and Xinghua chicken had the greatest abundance of resistance genes. The results of a broad-spectrum profile of ARG abundance showed a significantly higher diversity of these genes in Chinese chicken gut than that in Europe, which correlates with the overall livestock antimicrobial use [

43]. The genes tetX, mcr, and blaNDM, were detected in the Chinese samples and the abundance of ARGs was linearly correlated with that of mobile genetic elements (MGEs).

2.2.2. Meat and Derivates

Meat and its products represent a significant portion of daily human consumption, and it’s characterized by high protein content, richness in B vitamins and diverse micronutrients [

45]. However, meat contamination and its adulteration has become a global issue. On one hand, ARM genes and bacteria are most prevalent in meats and are sources of viral infections [

46]. On the other hand, meat is often detected mixed with cheaper chicken, duck, pork, and animal meat [

47] which disrupts market order [

48] and harms consumers’ rights and interests [

49]. Therefore, the identification of meat and its derivatives, as well as of viral and bacterial genomes present in these products is essential to improve food quality, safety and to avoid food fraud. Meats have been identified as a concern, given that animals in the food supply chain are susceptible to virus infections, raising the potential for cross-species transmission [

50]. Many viruses found in farms or wild animals, including noroviruses, rotaviruses, and hepatitis E virus (HEV), can lead to zoonotic infections [

46]. These food types and their derivatives are a source of enteric infections in humans, contaminates meat during slaughter and preparation by enteric viruses harbored by farm animals. With a notable presence of HEV found in pork, deer, and wild boar meat [

51,

52], and the associated risk as a potential origin for various HIV epidemics (HIV-1 groups M, N, O, P, and HIV-2 groups A–H) and Ebola virus outbreaks [

53,

54], there has been a substantial increase in efforts to characterize these viruses in recent years. [

55] obtained metagenomics-derived viral sequences detected in beef, pork and chicken purchase from San Francisco, United States. In beef samples, eukaryotic viral sequences related to parvovirus, polyomaviruses (BPyV2-SF being novel), anelloviruses and circoviruses were detected, with the presence of porcine hokovirus in beef indicated its ability to infect both species. In ground beef products of Brazil

Firmicutes and

Proteobacteria have been identified as the predominant phylia in the microbiome, with the most abundant taxa being the

Lactobacillales [

56]. Common spoilage genera like

Lactococcus,

Leuconostoc, and

Lactobacillus were also identified. The resistome of ground beef samples in this study was dominated by gene accessions conferring resistance to tetracycline drugs, consistent with studies by [

57] and [

1] who also studied different cattle environments.

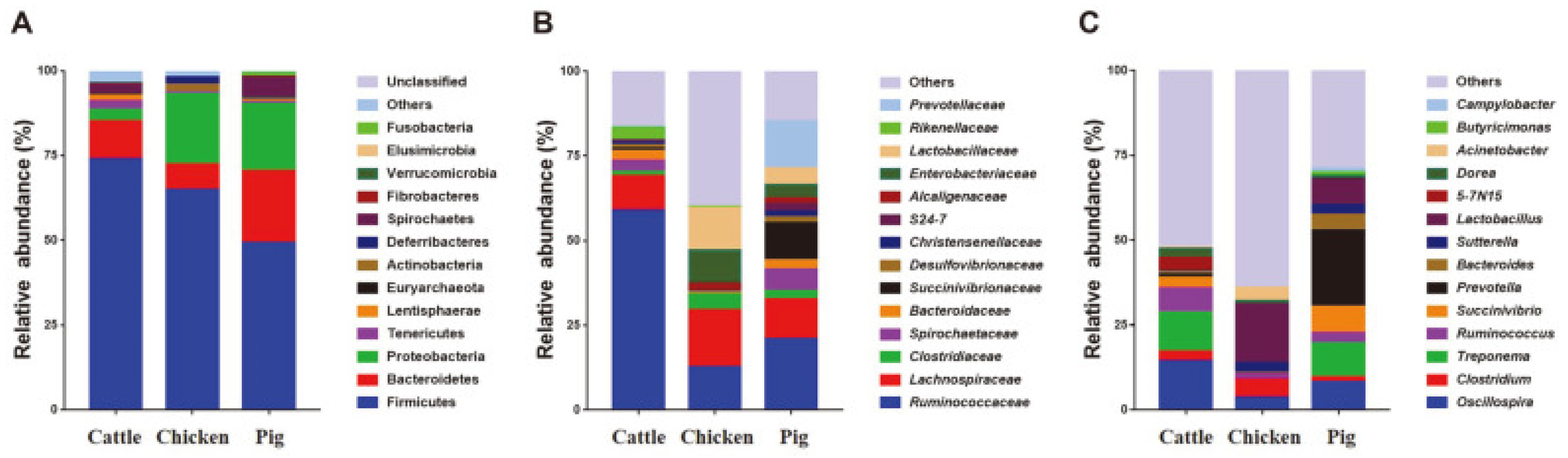

As mentioned before, metagenomics approaches have been used to detect the prevalence of foodborne pathogens in diverse samples, such as foods and feces. As shown in

Figure 1, the microbiota of cattle, chicken and pig feces have been characterized and analyzed. In pork sequences related to parvoviruses, anelloviruses and circoviruses were detected, and chicken meat presented a high number of gyrovirus, including a novel species (GyV7-SF). [

50] unveiled significant genetic diversity among CRESS-DNA viruses in chicken, pork, and beef samples from Brazil, with some genomes defying classification at the family level. Chicken and pork samples exhibited a variety of anelloviruses (gyroviruses in chicken and Torque teno viruses in swine). Furthermore, across all analyzed meat samples, the predominant viral sequences were identified as bacteriophages associated with

Acinetobacter and

Pseudomonas, genera commonly found in bacteria isolated from meat samples. In this study, however, the plethora of genome sequences representing known and novel viral entities identified in the meat samples were not linked to human diseases. In comparison to the viral makeup of meat samples obtain by [

54], Brazilian meat samples presented certain resemblances (anelloviruses and parvoviruses in pork, and gyroviruses in chicken), however, they exhibited no phylogenetic connection. The difference between the viruses reported in North America indicated that even with the high degree of globalization in agribusiness, the viral communities in the meat samples analyzed were characterized by their distinct geographic locations.

3. Conclusions

Metagenomics has emerged as a groundbreaking tool in food analysis, offering insights into the microbial communities of various products including fruits, vegetables, poultry and meat. This approach has enhanced our understanding of microbial diversity, functional properties, and interactions between food components and microbiota, playing a crucial role in food safety, quality, and disease control. Through the direct analysis of whole genomes within a sample, metagenomics has reduced the reliance on classic microbiology procedures, such as culture-dependent techniques, providing a more comprehensive understanding of microbial communities. Particularly, it has been beneficial in the identification and tracking of contamination, the detection of pathogens, and understanding the microbial composition of various food products.

In fresh produce, metagenomics studies have revealed the complex bacterial and fungal communities present, which highlights the influence of different factors such as season, irrigation, and soil type in the microbiome of these products. These insights are essential for the development of targeted control measures throughout the processes of harvesting, handling, and distribution to ensure food safety. Similarly, in poultry products, metagenomics has been crucial in identifying pathogenic bacteria and understanding microbial dynamics in poultry farms to ensure the development of safety applications for public health. In meat, the use of metagenomics has provided valuable information on the presence of pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and microbial communities involved in food spoilage. It has also highlighted the issue of antibiotic resistance in meat products, emphasizing the need for alternative strategies to manage microbial contamination, as well as prevent food fraud.

As a food analysis technique, metagenomics still faces several challenges, such as lack of bioinformatics expertise, the need of sophisticated tools, the inability to differentiate living organisms from dead ones, food matrix challenges, among many others. However, it has proven to be a powerful tool worth the addressing of these challenges for the widespread adoption of metagenomic technologies in the food industry for the continuation of research and investment to unlock new possibilities for the future of food safety.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.O.M. and E.F.F; methodology, T.M., B.R, M.R, J.A, E.F.F and L.O M.; validation, L.O.M. and E.F.F.; formal analysis, T.M., B.R, M.R and J.A.; investigation, T.M., B.R, M.R, and J.A.; resources, L.O.M. and E.F.F.; data curation, T.M., B.R, M.R and J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M., B.R, M.R and J.A.; writing—review and editing, L.O.M. and E.F.F; supervision, L.O.M. and E.F.F.; project administration, L.O.M. and E.F.F.; funding acquisition, L.O.M. and E.F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministerio de Eduacion Supeior Ciencia y Tecnologia (MESCYT) through Fondo Nacional de Innovación y Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDOCYT), grant number 2022-2A4-204: Una Sola Salud-Inocuidad Alimentaria. Evaluación De Riesgos Microbiológicos Patogénicos En Carnes De Cerdo Y Pollo, Y Subproductos.

Data Availability Statement

N/A

Acknowledgments

This research project was successfully conducted thanks to the support provided by the Research Vice-Rectory and the Deanship of Basic and Environmental Sciences at Instituto Tecnologico de Santo Domingo (INTEC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Weinroth, M. D., Noyes, N. R., Morley, P. M., & Belk, K. E. (2019). Metagenomics of Meat and Poultry. Food Microbiology: Fundamentals and Frontiers, 939–962. [CrossRef]

- Juszczuk-Kubiak, E., Greguła-Kania, M., & Sokołowska, B. (2021). “Food-Omics” Applications In The Food Metagenom Profiling. Postępy Mikrobiologii - Advancements of Microbiology, 60(1), 59–75. [CrossRef]

- Billington, C., Kingsbury, J. M., & Rivas, L. (2022). Metagenomics Approaches for Improving Food Safety: A Review. Journal of Food Protection, 85(3), 448–464. [CrossRef]

- Sequino, G., Valentino, V., Torrieri, E., & De Filippis, F. (2022). Specific Microbial Communities Are Selected in Minimally-Processed Fruit and Vegetables according to the Type of Product. Foods, 11(14), 2164. [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F., Parente, E., & Ercolini, D. (2017). Metagenomics insights into food fermentations. Microbial Biotechnology, 10(1), 91. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-the, C., & Carlin, F. (1994). The microbiology of minimally processed fresh fruits and vegetables. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition, 34(4), 371–401. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, G., Sbodio, A., Tech, J. J., Suslow, T. V., Coaker, G. L., & Leveau, J. H. J. (2012). Leaf microbiota in an agroecosystem: spatiotemporal variation in bacterial community composition on field-grown lettuce. The ISME Journal, 6(10), 1812. [CrossRef]

- Critzer, F. J., & Doyle, M. P. (2010). Microbial ecology of foodborne pathogens associated with produce. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 21(2), 125–130. [CrossRef]

- Peroni, D. G., Nuzzi, G., Trambusti, I., Di Cicco, M. E., & Comberiati, P. (2020). Microbiome Composition and Its Impact on the Development of Allergic Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Alegbeleye, O., Odeyemi, O. A., Strateva, M., & Stratev, D. (2022). Microbial spoilage of vegetables, fruits and cereals. Applied Food Research, 2(1), 100122. [CrossRef]

- Tatsika, S., Karamanoli, K., Karayanni, H., & Genitsaris, S. (2019). Metagenomic Characterization of Bacterial Communities on Ready-to-Eat Vegetables and Effects of Household Washing on their Diversity and Composition. Pathogens 2019, Vol. 8, Page 37, 8(1), 37. [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, W. A., Cernava, T., Wassermann, B., Abdelfattah, A., Soto-Giron, M. J., Toledo, G. V., Virtanen, S. M., Knip, M., Hyöty, H., & Berg, G. (2023). The edible plant microbiome: evidence for the occurrence of fruit and vegetable bacteria in the human gut. Gut Microbes, 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Fanning, S., Proos, S., Jordan, K., & Srikumar, S. (2017). A Review on the Applications of Next Generation Sequencing Technologies as Applied to Food-Related Microbiome Studies. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8(SEP). [CrossRef]

- Söderqvist, K., Ahmed Osman, O., Wolff, C., Bertilsson, S., Vågsholm, I., & Boqvist, S. (2017). Emerging microbiota during cold storage and temperature abuse of ready-to-eat salad. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology, 7(1), 1328963. [CrossRef]

- Kokaeva, L., Chudinova, E., Berezov, A., Yarmeeva, M., Balabko, P., Belosokhov, A., & Elansky, S. (2020). Fungal diversity in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) leaves and fruits in Russia. Journal of Central European Agriculture, 21(4), 809–816. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P., Santoni, S., Weber, A., This, P., & Péros, J. P. (2019). Understanding the phyllosphere microbiome assemblage in grape species (Vitaceae) with amplicon sequence data structures. Scientific Reports 2019 9:1, 9(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Stanevičienė, R., Lukša, J., Strazdaitė-žielienė, Ž., Ravoitytė, B., Losinska-sičiūnienė, R., Mozūraitis, R., & Servienė, E. (2021). Mycobiota in the carposphere of sour and sweet cherries and antagonistic features of potential biocontrol yeasts. Microorganisms, 9(7), 1423. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. S., Bae, J. W., & Park, E. J. (2018). Geographic and Host-Associated Variations in Bacterial Communities on the Floret Surfaces of Field-Grown Broccoli. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 84(8). [CrossRef]

- Angeli, D., Sare, A. R., Jijakli, M. H., Pertot, I., & Massart, S. (2019). Insights gained from metagenomic shotgun sequencing of apple fruit epiphytic microbiota. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 153, 96–106. [CrossRef]

- Bartuv, R., Berihu, M., Medina, S., Salim, S., Feygenberg, O., Faigenboim-Doron, A., Zhimo, V. Y., Abdelfattah, A., Piombo, E., Wisniewski, M., Freilich, S., & Droby, S. (2023). Functional analysis of the apple fruit microbiome based on shotgun metagenomic sequencing of conventional and organic orchard samples. Environmental Microbiology, 25(9), 1728–1746. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, F., Moser, G., Müller, H., & Berg, G. (2011). Functional and Structural Microbial Diversity in Organic and Conventional Viticulture: Organic Farming Benefits Natural Biocontrol Agents. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77(6), 2188. [CrossRef]

- Sofos, J. N. (2008). Challenges to meat safety in the 21st century. Meat Science, 78(1–2), 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Pothakos, V., Stellato, G., Ercolini, D., & Devlieghere, F. (2015). Processing Environment and Ingredients Are Both Sources of Leuconostoc gelidum, Which Emerges as a Major Spoiler in Ready-To-Eat Meals. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 81(10), 3529–3541. [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, F., Corsello, G., Cricelli, C., Ferrara, N., Ghiselli, A., Lucchin, L., & Poli, A. (2015). Role of poultry meat in a balanced diet aimed at maintaining health and wellbeing: an Italian consensus document. Food & Nutrition Research, 59, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A., De, J., & Schneider, K. R. (2020). Prevalence, Concentration, and Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Salmonella Isolated from Florida Poultry Litter. Journal of Food Protection, 83(12), 2179–2186. [CrossRef]

- Golden, C. E., Rothrock, M. J., & Mishra, A. (2021). Mapping foodborne pathogen contamination throughout the conventional and alternative poultry supply chains. Poultry Science, 100(7), 101157. [CrossRef]

- Shaji, S., Selvaraj, R. K., & Shanmugasundaram, R. (2023). Salmonella Infection in Poultry: A Review on the Pathogen and Control Strategies. Microorganisms, 11(11). [CrossRef]

- Dahshan, H., Merwad, A. M. A., & Mohamed, T. S. (2016). Listeria Species in Broiler Poultry Farms: Potential Public Health Hazards. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 26(9), 1551–1556. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. yu, Wang, H. hu, Han, Y. wei, Xing, T., Ye, K. ping, Xu, X. lian, & Zhou, G. hong. (2017). Evaluation of the spoilage potential of bacteria isolated from chilled chicken in vitro and in situ. Food Microbiology, 63, 139–146. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B., Pena, P., Cervantes, R., Dias, M., & Viegas, C. (2022). Microbial Contamination of Bedding Material: One Health in Poultry Production. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16508. [CrossRef]

- Treiber, F. M., & Beranek-Knauer, H. (2021). Antimicrobial Residues in Food from Animal Origin—A Review of the Literature Focusing on Products Collected in Stores and Markets Worldwide. Antibiotics, 10(5). [CrossRef]

- Kahn, L. H., Bergeron, G., Bourassa, M. W., De Vegt, B., Gill, J., Gomes, F., Malouin, F., Opengart, K., Ritter, G. D., Singer, R. S., Storrs, C., & Topp, E. (2019). From farm management to bacteriophage therapy: strategies to reduce antibiotic use in animal agriculture. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1441(1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Ricke, S. C., Lee, S. I., Kim, S. A., Park, S. H., & Shi, Z. (2020). Prebiotics and the poultry gastrointestinal tract microbiome. Poultry Science, 99(2), 670–677. [CrossRef]

- Weinroth, M. D., Thomas, K. M., Doster, E., Vikram, A., Schmidt, J. W., Arthur, T. M., Wheeler, T. L., Parker, J. K., Hanes, A. S., Alekoza, N., Wolfe, C., Metcalf, J. L., Morley, P. S., & Belk, K. E. (2022). Resistomes and microbiome of meat trimmings and colon content from culled cows raised in conventional and organic production systems. Animal Microbiome, 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013). ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE THREATS in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf.

- Segura-Wang, M., Grabner, N., Koestelbauer, A., Klose, V., & Ghanbari, M. (2021). Genome-Resolved Metagenomics of the Chicken Gut Microbiome. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12, 726923. [CrossRef]

- Glendinning, L., Stewart, R. D., Pallen, M. J., Watson, K. A., & Watson, M. (2020). Assembly of hundreds of novel bacterial genomes from the chicken caecum. Genome Biology, 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Medvecky, M., Cejkova, D., Polansky, O., Karasova, D., Kubasova, T., Cizek, A., & Rychlik, I. (2018). Whole genome sequencing and function prediction of 133 gut anaerobes isolated from chicken caecum in pure cultures. BMC Genomics, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Beauclercq, S., Nadal-Desbarats, L., Hennequet-Antier, C., Gabriel, I., Tesseraud, S., Calenge, F., Le Bihan-Duval, E., & Mignon-Grasteau, S. (2018). Relationships between digestive efficiency and metabolomic profiles of serum and intestinal contents in chickens. Scientific Reports, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J., Kristiansson, E., & Larsson, D. G. J. (2018). Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42(1), 68–80. [CrossRef]

- Nathan, C., & Cars, O. (2014). Antibiotic Resistance — Problems, Progress, and Prospects. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(19), 1761–1763. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Tong, C., Xiao, D., Xie, L., Zhao, R., Huo, Z., Tang, Z., Hao, J., Zeng, Z., & Xiong, W. (2022). Metagenomic Insights into Chicken Gut Antibiotic Resistomes and Microbiomes. Microbiology Spectrum, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Lyu, N., Liu, F., Liu, W. J., Bi, Y., Zhang, Z., Ma, S., Cao, J., Song, X., Wang, A., Zhang, G., Hu, Y., Zhu, B., & Gao, G. F. (2021). More diversified antibiotic resistance genes in chickens and workers of the live poultry markets. Environment International, 153, 106534. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Huang, Y., Guo, L., Zhang, S., Wu, R., Fang, X., Xu, H., & Nie, Q. (2022). Metagenomic analysis reveals the microbiome and antibiotic resistance genes in indigenous Chinese yellow-feathered chickens. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13, 930289. [CrossRef]

- Campagnol, P. C. B., Lorenzo, J. M., Dos Santos, B. A., & Cichoski, A. J. (2022). Recent advances in the development of healthier meat products. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, 102, 123–179. [CrossRef]

- Villabruna, N., Koopmans, M. P. G., & de Graaf, M. (2019). Animals as Reservoir for Human Norovirus. Viruses 2019, Vol. 11, Page 478, 11(5), 478. [CrossRef]

- Premanandh, J. (2013). Horse meat scandal – A wake-up call for regulatory authorities. Food Control, 34(2), 568–569. [CrossRef]

- Peng, G. J., Chang, M. H., Fang, M., Liao, C. D., Tsai, C. F., Tseng, S. H., Kao, Y. M., Chou, H. K., & Cheng, H. F. (2017). Incidents of major food adulteration in Taiwan between 2011 and 2015. Food Control, 72(Part A), 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., & Xue, J. (2016). Economically motivated food fraud and adulteration in China: An analysis based on 1553 media reports. Food Control, 67, 192–198. [CrossRef]

- Cibulski, S., Alves de Lima, D., Fernandes dos Santos, H., Teixeira, T. F., Tochetto, C., Mayer, F. Q., & Roehe, P. M. (2021). A plate of viruses: Viral metagenomics of supermarket chicken, pork and beef from Brazil. Virology, 552, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Akpoigbe, K., Culpepper-Morgan, J., Akpoigbe, O., & Santogade, P. (2023). Acute Hepatitis E Infection Associated With Deer Meat in the United States. ACG Case Reports Journal, 10(6), e01068. [CrossRef]

- Locus, T., Lambrecht, E., Willems, S., Peeters, M., Vanwolleghem, T., & Gucht, S. Van. (2023). The Effect of Meat Processing Techniques on Hepatitis E Virus Infectivity in Real-Life Pork Meat Matrices. IAFP. https://iafp.confex.com/iafp/euro23/onlineprogram.cgi/Paper/31833.

- Leroy, E. M., Rouquet, P., Formenty, P., Souquière, S., Kilbourne, A., Froment, J. M., Bermejo, M., Smit, S., Karesh, W., Swanepoel, R., Zaki, S. R., & Rollin, P. E. (2004). Multiple Ebola Virus Transmission Events and Rapid Decline of Central African Wildlife. Science, 303(5656), 387–390. [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Juarez, A., Frias, M., Martinez-Peinado, A., Risalde, M. A., Rodriguez-Cano, D., Camacho, A., García-Bocanegra, I., Cuenca-Lopez, F., Gomez-Villamandos, J. C., & Rivero, A. (2017). Familial Hepatitis E Outbreak Linked to Wild Boar Meat Consumption. Zoonoses and Public Health, 64(7), 561–565. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Li, L., Deng, X., Kapusinszky, B., & Delwart, E. (2014). What is for dinner? Viral metagenomics of US store bought beef, pork, and chicken. Virology, 468–470, 303–310. [CrossRef]

- Doster, E., Thomas, K. M., Weinroth, M. D., Parker, J. K., Crone, K. K., Arthur, T. M., Schmidt, J. W., Wheeler, T. L., Belk, K. E., & Morley, P. S. (2020). Metagenomic Characterization of the Microbiome and Resistome of Retail Ground Beef Products. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11, 541972. [CrossRef]

- Huebner, K. L., Martin, J. N., Weissend, C. J., Holzer, K. L., Parker, J. K., Lakin, S. M., Doster, E., Weinroth, M. D., Abdo, Z., Woerner, D. R., Metcalf, J. L., Geornaras, I., Bryant, T. C., Morley, P. S., & Belk, K. E. (2019). Effects of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product on liver abscesses, fecal microbiome, and resistome in feedlot cattle raised without antibiotics. Scientific Reports, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Cho, J. H., Song, M., Cho, J. H., Kim, S., Kim, E. S., Keum, G. B., Kim, H. B., & Lee, J. H. (2021). Evaluating the Prevalence of Foodborne Pathogens in Livestock Using Metagenomics Approach. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 31(12), 1701. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).