Introduction

Congenital femoral deficiency (CFD) is a rare genetic condition with an incidence of 1.1-2.0 in 100,000 live births[

1], which encompasses a variety of paediatric developmental deformities of the femur bone[

2]. This condition often results in significant leg length discrepancy, deformity, and functional deficits[

3]. These patients are often also found to have distal femoral valgus deformities, medial femoral condylar hypoplasia, soft tissue contractures and, most importantly, anteroposterior knee instability due to a congenital agenesis of the anterior (ACL) and posterior (PCL) cruciate ligament[

4].Patients affected by CFD are commonly treated with leg-lengthening procedures[

5] at an early stage, however the resulting anteroposterior knee instability is often overlooked and commonly not diagnosed or only treated if the patient was to become symptomatic. This is considered unacceptable with modern advances in imaging techniques (magnetic resonance imaging)[

6], especially as the results of the un-treated instability could lead to heavy meniscal damage and early osteoarthritis.

Case Report

An 8-year-old girl presented to a different hospital with a complaint of leg length discrepancy, right shorter than left. She was brought to local medical attention and promptly diagnosed with congenital femoral deficiency and ipsilateral tibial hypoplasia. At this time, the patient had an acquired leg length discrepancy of 75 mm (femoral 50 mm and tibial 25mm) (

Figure 1), she therefore underwent a proximal femoral osteotomy and placement of a LRS

TM Orthofix monolateral external fixator to the femur at a different hospital. The procedure was well tolerated with no complications and adequate surgical wound healing. Seven days post-operatively she began the lengthening procedure which consisted of 1/4 turn 4 times per day for a total of 1 mm per day. The patient was followed every two weeks for the first month and then monthly with physical examination and plain film radiographs.

The patient was instructed to start physical therapy for hip and knee range of motion immediately after surgery, while progressive weight-bearing was commenced on the last day of lengthening. At 12 weeks the lengthening goal, 60 mm, was achieved. At 5-months follow up, lower-limb weight-bearing plain radiographs demonstrated that the right femur was within 5 mm of length of the left femur and bone regeneration was visible in the osteotomy gap, however, the study was limited by the inability to fully extend the right knee (

Figure 2). Lateral projection radiographs of the right knee showed posterior subluxation of the tibia with respect to the femoral condyles (

Figure 3). No action was taken at the time.

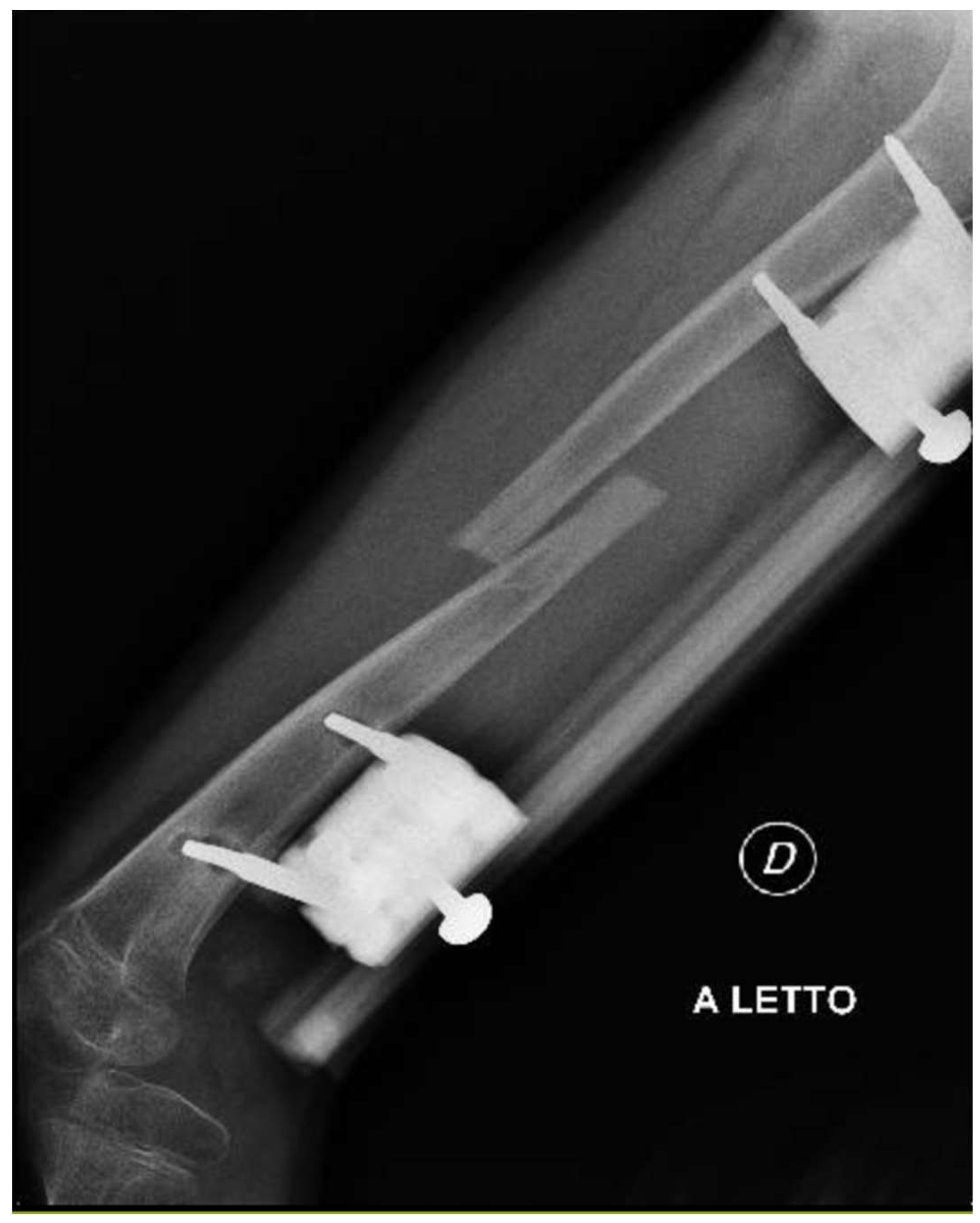

The patient presented to our attention at about 6 months post-surgery complaining of acute pain and deformity at the middle third of the thigh. Radiographs showed fracture of the femoral regenerate (

Figure 4). The patient underwent immediate external fixator removal, reduction of the knee dislocation and finally Elastic Stable Intramedullary Nailing (ESIN) of the femoral fracture prior attempt to ream the femoral canal losing 20 of the 60 mm lengthened (

Figure 5). Ten months after the procedure, the patient underwent nail removal for complete fracture consolidation.

At the age of 11, due to the persistent right femoral deficiency, the patient underwent temporary distal femur epiphysiodesis of the left lower limb thus allowing the length of the two femurs to be evened out in just over 2 years. Finally at the age of 14, due to the residual tibial hypoplasia (≅ 40 mm) and valgus knee (

Figure 6), she underwent a proximal right tibial osteotomy and placement of an antegrade PRECICE® expandable intramedullary nail and temporary femoral distal medial emiepiphysiodesis (

Figure 7) (

Figure 8).

2 years later, at the age of 16, the tibial intramedullary nail was removed and finally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee was acquired. This showed complete agenesis of both the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (

Figure 9) (

Figure 10).

After allowing for the patient to undergo complete recovery from the limb-lengthening procedure and carefully evaluating Tanner scale development of the patient, we decided to reconstruct both cruciate ligaments. The procedure was carried out by an experienced senior surgeon (EA) who reconstructed both ligaments in a single-sitting surgery.

The posterior cruciate ligament was the first to be reconstructed[

7].

Graft Harvesting:

Hamstring tendons were obtained through an incision over the pes anserinus, quadrupled on a graft preparation station, and secured with high-strength non absorbable suture (Orthocord no. 2, Mitek; or Fiberwire no. 5, Arthrex, Naples, FL). The proximal loop was then whip-stitched with vicryl no. 2 to form a tubular graft, and the four ends are prepared with vicryl no. 2. The graft was marked 30 mm from the loop apex using a surgical pen, and its diameter measured.

Portals:

The anteromedial parapatellar portal was established. The anterolateral portal was then formed slightly lower than normal in order to allow the femoral tunnel to be prepared with the in-out technique.

Joint Preparation:

The arthroscope was positioned through the anterolateral portal, while the shaver introduced through the anteromedial portal to clear any residual tissue from where the ideal femoral attachment site of the PCL should normally be located. The intercondylar fossa was found to be completely closed, with no remnants or malformations of neither the ACL nor PCL. Meniscal fibrocartilage was present, however there was total absence of menisco-femoral ligaments, contrary to what is commonly described in similar cases[

8].

Tibial Tunnel Drilling:

Using the TransTibial PCL guide and a cannulated reamer sized to match the graft diameter, the tibial tunnel was meticulously drilled. Additionally, a high-strength nonabsorbable passing suture was placed within the tibial tunnel.

Femoral Half Tunnel Drilling:

Identification of where the native PCL footprint would have been on the lateral surface of the medial femoral condyle initiated the femoral half tunnel drilling. The femoral aimer was then positioned through the lower anterolateral portal, and the in-out drilling technique with a cannulated reamer matching the graft diameter was employed. The femoral half tunnel was drilled to a depth of 27 mm to accommodate the curve guide, ensuring precision in the surgical process.

Fixation Preparation with Curve Cross-Pin System:

Inserting the curve guide frame through the lower anterolateral portal, the femoral rod was placed in the femoral half tunnel until the 27 mm marking was reached. Accurate placement of the guide block on the lateral femoral condyle is essential for trocar, sleeve, and pin insertion. This technique positions the guide block 2.5 cm anterior and 2.5 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle. The arc attachment was assembled, and bone stock evaluated using a bone gauge pin against the medial femoral condyle cortex. Trocars were inserted from the lateral femoral condyle downward and laterally. A passing suture through the femoral rod size was placed, and the bone gauge pin used through trocars for visual confirmation of correct positioning within the half tunnel.

Graft Passage:

Tibial and femoral passing sutures were retrieved through the anterolateral portal. A loop was created in the femoral passing suture, with the tibial passing suture threaded through. The loop, housing the tibial passing suture, was then pulled out of the femoral tunnel as a single passing suture. The graft was positioned on the passing suture at the tibial tunnel entrance and smoothly passed through with assistance from a blunt instrument in the posteromedial portal.

Femoral Fixation: The graft was secured on the femur using pins, ensuring alignment with the trocar, and verifying the laser line alignment.

Tibial Fixation: The knee underwent cycling through flexion and extension to condition the graft. At 70° of knee flexion, the graft was securely fixed using a 2 mm interference screw.

We then proceeded with reconstructing the anterior cruciate ligament.

Graft preparation

The graft was prepared for fixation by a suspensory mechanism with an ULTRABUTTON (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA) at one end.

Tibial Tunnel Drilling:

Using the TransTibial ACL guide and a cannulated reamer sized to match the graft diameter, the tibial tunnel was drilled. Additionally, a high-strength nonabsorbable passing suture was placed within the tibial tunnel.

Femoral Half Tunnel Drilling:

Identification of the ACL footprint on the neo-medial surface of the lateral femoral condyle. The femoral anteromedial aimer 5.5 mm was then positioned through the lower anteromedial portal, and with the knee flexed at 110° we passed a Kirschner guide wire. We used a 4.5mm reamer to perform a full tunnel for the femoral suspension fixation, the femoral half tunnel was then drilled to a depth of 23 mm to accommodate the graft with a 8.5mm reamer.

Graft Passage:

Tibial and femoral passing sutures were retrieved through the anteromedial portal. A loop was created in the femoral passing suture, with the tibial passing suture threaded through. The loop, housing the tibial passing suture, was then pulled out of the femoral tunnel as a single passing suture. The graft was positioned on the passing suture at the tibial tunnel entrance and passed through the tunnels.

Femoral Fixation: The graft was secured on the femur using the suspension fixation with ULTRABUTTON (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA).

Tibial Fixation: The knee underwent cycling through flexion and extension to condition the graft. At 30° of knee flexion, the graft was securely fixed using a 10x25 mm interference screw BIOSURE REGENESORB (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA).

A surgical drain was inserted through the AL portal and secured. Vicryl rapid sutures were used for skin closure. No intra-operative complications were reported, with a total surgical time of 63 minutes from incision to final suture. Total tourniquet time 45 minutes.

The patient underwent physical rehabilitation according to standard protocols and made a full recovery. Clinical follow-up showed complete knee range of motion and negative anterior and posterior drawer tests. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) at 6 months post-operation showed correct graft positioning and maturation (Figure 11) (Figure 12).

Discussion and Conclusion

ACL and PCL reconstruction in paediatric patients remains a highly controversial topic due to the supposed risks of damaging the physis when forming the tibial and femoral tunnels[

9]. However, recent literature has shown how early surgical intervention is to be preferred to delayed treatment as this carries more risks of knee instability, delayed return to sports and activities of daily living and, most importantly, meniscal damage and early cartilage wear[

10]. These principles should also be applied to young patients affected by congenital femoral deficiency. In the case we reported, the patient was a 16-year-old with Tanner stage IV, therefore there was no doubt about the necessity of immediate multi-ligament reconstruction.

Single-stage ACL and PCL reconstruction versus two-stage is debatable and much related to surgeon preference and experience however, where possible, single-stage should be preferred to avoid unnecessary anaesthesia on a paediatric patient and in order to allow for a prompt return to normal activities following a single period of intensive rehabilitation.

In very young patients with open-physis, the reconstruction should be carried out via physeal-sparing techniques such as over-the-top[

11] or all-inside[

12] surgical techniques to reduce the risk of physeal damage.

For patients affected by congenital femur deficiency, whether this has already been diagnosed or is suspected, a knee MRI (1.5 Tesla or superior) should always be requested to exclude ligamentous agenesis and to avoid knee subluxation during limb-lengthening procedures, this is also a safe diagnostic technique as it carries no added radiation risk for the young patient. In alternative, where requesting an MRI is not feasible, a full knee exam to exclude anterior-posterior knee instability (Anterior-drawer test, Lachman, Jerk test) should be performed in all paediatric patients’ candidates for limb-lengthening – these should always be done comparatively with the other limb and caution should always be taken as paediatric patients can often have a congenital knee laxity which could be mistaken for an incompetent cruciate ligament. Limb lengthening procedures should always take precedence over ligamentous reconstruction which should be carried out once these are complete and acceptable skeletal maturity (minimum Tanner 4) is reached.

When carrying out the limb lengthening procedures, extreme caution should be taken to avoid dislocating the knee joint. In severe cases of joint instability, the application of a hinged-knee external fixator could be considered with caution.

References

- Uduma, F.U.; Dim, E.M.; Njeze, N.R. Proximal femoral focal deficiency - a rare congenital entity: two case reports and a review of the literature. J. Med Case Rep. 2020, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udit Agrawal and Vivek Tiwari, (2023) ‘Congenital Femoral Deficiency’, StatPearls.

- Nossov, S.B.; Hollin, I.L.; Phillips, J.; Franklin, C.C. Proximal Femoral Focal Deficiency/Congenital Femoral Deficiency: Evaluation and Management. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 30, E899–E910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. F. Stanitski and S. Kassab., (1997) ‘Rotational Deformity in Congenital Hypoplasia of the Femur’, Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics 17, no. 4: 525–27.

- Hankemeier, S.; Pape, H.-C.; Wiebking, U.; Krettek, C.; Gösling, T. Verlängerung der unteren Extremität mit dem Intramedullary Skeletal Kinetic Distractor (ISKD). Oper. Orthopadie Und Traumatol. 2005, 17, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, D.D.; Epps, C.H. PROXIMAL FEMORAL FOCAL DEFICIENCY: EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT. Orthopedics 1991, 14, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriani, E.; Di Paola, B.; Alfieri, A.; De Fenu, E. Femoral Fixation With Curve Cross-Pin System in Arthroscopic Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Arthrosc. Tech. 2018, 7, e289–e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berruto, M.; Gala, L.; Usellini, E.; Duci, D.; Marelli, B. Congenital absence of the cruciate ligaments. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2012, 20, 1622–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Kwaees, T.A.; Accadbled, F.; Turati, M.; Green, D.W.; Nicolaou, N. Surgical techniques in the management of pediatric anterior cruciate ligament tears: Current concepts. J. Child. Orthop. 2023, 17, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, K.L.; Lam, K.C.; McLeod, T.C.V. Early Operative Versus Delayed or Nonoperative Treatment of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Pediatric Patients. J. Athl. Train. 2016, 51, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaffagnini, S.; Lucidi, G.A.; Macchiarola, L.; Agostinone, P.; Neri, M.P.; Marcacci, M.; Grassi, A. The 25-year experience of over-the-top ACL reconstruction plus extra-articular lateral tenodesis with hamstring tendon grafts: the story so far. J. Exp. Orthop. 2023, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuelle, C.W.; Balldin, B.C.; Slone, H.S. All-Inside Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2022, 38, 2368–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).