Introduction

Vimentin, a type III intermediate filament (IF) protein was found almost in all neural precursor cells. However, their differentiation into mature neurons is accompanied by the gradual replacement of vimentin IFs for neurofilaments, type IV IF proteins [

1]. The studies of the T. Shea’s laboratory demonstrated the involvement of vimentin IFs in the initial stages of neuritogenesis [

2] though their exact role remains unclear. The observed localization of vimentin in the growing axons suggested its participation in the process of neuronal differentiation [

3]. It was also shown that depletion of vimentin in cultured neuroblastoma cells and hippocampal neurons suppressed the formation of neurites [

2,

4].

Mitochondria play important role in neural differentiation as well as in functioning of mature neurons [

5]. Being the main source of energy in the form of ATP, mitochondria are transported to and localized at the sites of energy consumption by the elaborate transport system based on microtubules and actin cytoskeleton together with associated motor proteins [

6,

7]. The formation and the maintenance of the dynamic structures of actin microfilaments and microtubules by themselves require a lot of ATP not to mention the energy drain by transport of different cargoes by motor protein ATPases [

8]. This requires a reliable delivery and functioning of mitochondria at appropriate sites. Remarkably, the mitochondria positioning at growth cones and extensions is correlated with an active axonal elongation [

9], and the potential of mitochondria localized in distal parts of neurites was found to be more hyperpolarized than that in the soma and along the main shaft [

10].

By now, evidence has accumulated that IFs influence the shape, motility and, more importantly, functioning of mitochondria in different cell types [

11,

12]. Neurons are no exception: the interaction of mitochondria with neurofilament proteins was extensively studied [

13] and the involvement of this cytoskeleton component in mitochondrial functions was reliably proven. Besides, the available data suggest that binding of mitochondria to neurofilaments in axons and dendrites is under control of different regulatory signals [

14,

15]. At the same time, it is unknown if neurofilaments responsible for mitochondrial distribution regulate their functions, in particular, the mitochondrial membrane potential. Having shown that vimentin IFs in fibroblasts were involved in a maintenance of the mitochondrial potential [

16] we assumed that in developing neurons this protein could perform the similar role. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed mitochondrial membrane potential in the catecholaminergic neuronal cell line CAD that offers a convenient model to study neurogenesis. These cells actively divide in the full media but start neuronal differentiation when transferred to serum-free medium [

17]. The results of this work demonstrate that knockout of vimentin gene in CAD cells using CRIPR Cas9 system leads to the decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential in nascent neurites. However, reconstitution of vimentin IFs by transfection of these cells with plasmid encoding human vimentin caused the recovery of mitochondrial potential to the initial level.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

CAD cells (CATH.a, CRL-3595, ATCC) were cultured in DMEM/F12 (PanEco, Russia) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biolot, Russia), penicillin (100 µg/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) (Sigma, USA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Differentiation was induced by switching proliferating cells to a serum-free medium DMEM/F12. For microscopy, cells were seeded on sterile coverslips and incubated for 24 or 48 hours.

Gene Knockout

To knockout the vimentin gene in CAD cells, the CRISPR Cas9 system was used to induce nonhomologous end joining after double-strand breaks. The plasmid vector pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro [

18] (Addgene, Watertown, MA) was digested by BstV2I (Sibenzyme, Novosibirsk, Russia), and the duplex was provided by two annealed oligos: CACCGCGCCAGCAGTATGAAAGCG and AAACCGCTTTCATACTGCTGGCGC, which were inserted into the sequence encoding the guide RNA to provide a pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro-Vim plasmid. The cells were transfected with this plasmid and a selection of the CAD(Vim-/-) cells was performed in DMEM/F12 medium containing 2 µg/ml puromycin and 1 µg/ml verapamil.

Transfection

Transfection of cells with plasmids pVim(wt), Vim(P57R) [

19], pSpCas9(BB)-2a-puro-Vim, and pVB6-Chromobody [

20] was conducted using the Transfectin reagent (Evrogen, Russia). Briefly, 1 µg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 1 µl of the transfection reagent in 0.1 ml of DMEM without serum and antibiotics and added to cells in 1 ml of complete DMEM/F12 medium.

Fluorescent Microscopy of Live Cells

Mitochondria in CAD cells were stained with the membrane potential sensitive dye JC-1 (0.1 – 2.0 µg/ml (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) [

21,

22] for 30 minutes at 37°C. Following incubation, coverslips with cells were placed in a sealed chamber containing DMEM/F12 medium and imaged using a Keyence BZ-9000 microscope (USA), which was equipped with an incubator for live-cell imaging. The temperature within the incubator was maintained at 36 ± 2°C. Imaging was conducted with a PlanApo 63x objective and a 12-bit digital CCD camera. The acquired images were transferred to a computer using BZ II Viewer software (Keyence, USA) and saved as 12-bit graphic files for further analysis.

JC-1 [5,5’,6,6’-tetrachloro-1,1’,3,3’-tetraethyl-benzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide] is a lipophilic cationic dye that forms a potential- and concentration-dependent J-aggregates. JC-1 in its monomeric form exhibits a green color (525 nm) when excited at 490 nm, whereas J-aggregates exhibit a red color (590 nm) when excited at 490 nm. Depending on the level of membrane potential and the concentration of the dye in the medium JC-1 uptake into the mitochondrial matrix either reaches the high concentration and forms J-aggregates or remains monomeric when the concentration is low. We have selected conditions that helped to distinguish highly energized mitochondria having a red color from green mitochondria with a lower potential.

Transfected cells with restored vimentin IFs were detected by the expression of VB6-Chromobody that allowed identification of vimentin filaments in live cells.

Immunofluorescence

To stain IFs the cells were fixed with methanol at -20°C for 10 minutes. Indirect immunofluorescence was then performed using chicken polyclonal antibodies against vimentin (Poly29191, BioVitrum, Russia), mouse monoclonal antibodies V9 against vimentin (Sigma, USA), and mouse monoclonal antibodies RMd020 against neurofilaments (Sigma, USA). FITC- and TRITC-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Jackson, USA) were used for detection. Microphotographs were acquired using a Keyence BZ-9000 microscope (USA) with a PlanApo 63x objective and a 12-bit digital CCD camera.

Immunoblotting

SDS-PAGE was conducted according to Laemmli’s method [

23], followed by immunoblotting as previously described [

24]. Vimentin was detected with rabbit polyclonal antibodies RVIM-AT [

25], alfa-tubulin with monoclonal antibodies DM1A (Sigma, USA), and secondary anti-mouse antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson, USA). As a substrate for peroxidase, hydrogen peroxide and diaminobenzidine were used, giving a brown color. Uncropped blots showing all bands are presented in supplementary materials.

Evaluation of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

In the cells stained with JC-1 the mitochondrial membrane potential was evaluated by counting mitochondria with high potential showing red fluorescence of J-aggregates in the conditions that allowed to distinguish them from those with low potential. Cells were incubated with 1.0 µg/ml of JC-1 for 30 min. Using ImageJ software, mitochondrial contours were defined within the region of interest, and then using the “analyze particles” plugin. The average number of mitochondria with high potential per 10 µm of the neurite length was defined.

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean number of mitochondria per 10 µm region of neurite, with standard errors. To check for normality, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used. An F-test was used to check for homogeneity of variance. The significance of differences was estimated statistically by paired-sample Student’s t-test.

Results

Production of Cell Line CAD with Knockout of Vimentin Gene

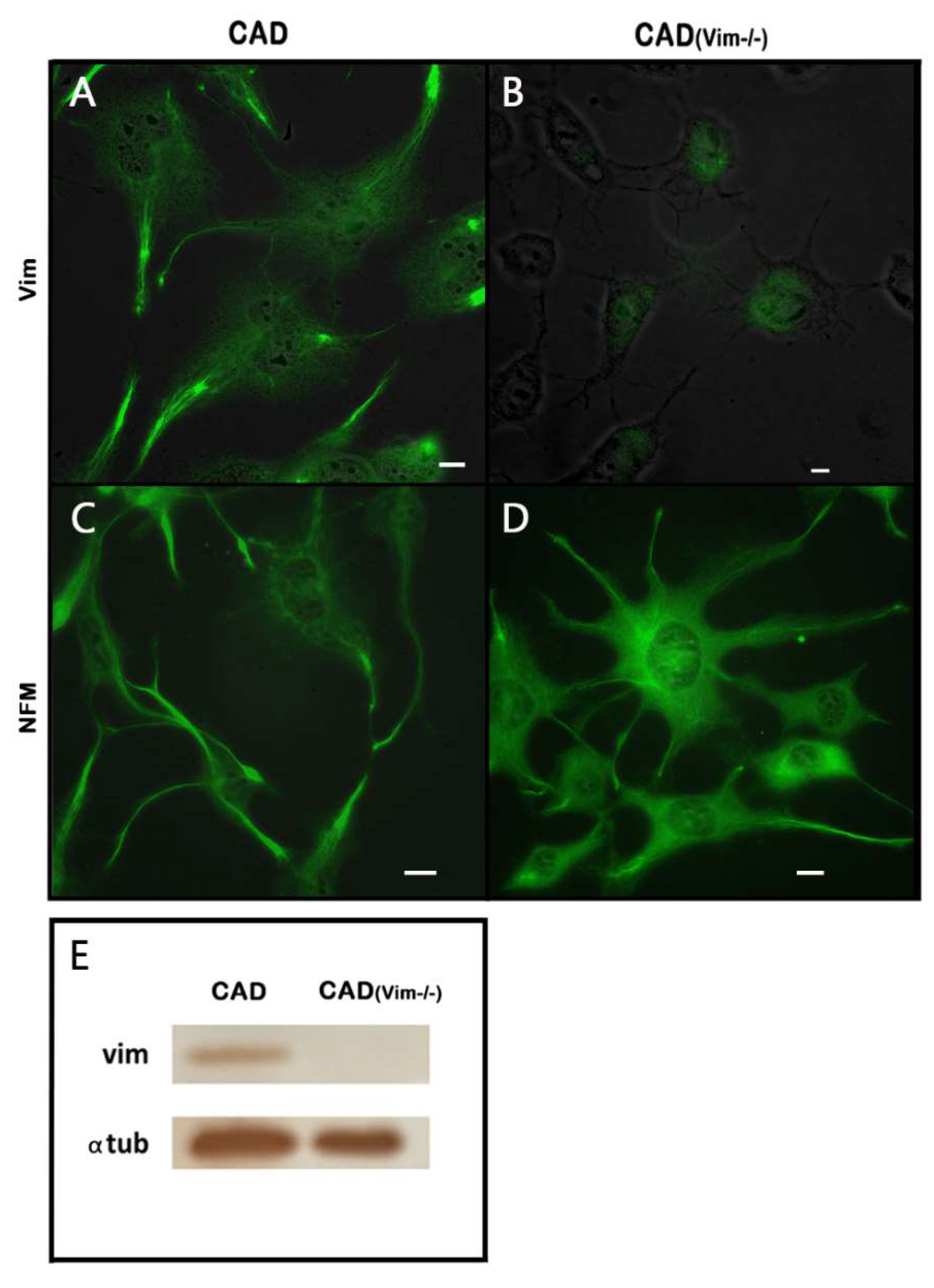

The catecholaminergic neuronal CAD cells represent a precursor cell line that undergoes neuronal differentiation when placed in the serum-free medium. Two types of IFs, vimentin and neurofilament triplet are characteristic of these cells. It can be seen in Figure1 that both networks are sparsely distributed in the cell bodies around the nuclei but show increased density in the processes.

It was shown earlier [

3] that vimentin IFs promote outgrowth of neurites, though their exact role is still unclear. To better understand the contribution of transitory expression of vimentin IFs in the formation of neuronal processes, we have produced CAD cells with knockout of vimentin gene and inspected their capacity to differentiate in serum-free medium. Using CRISPR Cas9 system we obtained CAD(Vim-/-) cells completely devoid of vimentin as show the results of immunoblotting (Figure1 E) and fluorescence microscopy (Figure1 B). These cells, however, contained neurofilaments (

Figure 1 D) and preserved the ability to form neurites though less effectively than wild type CAD cells (data not shown).

Vimentin-Null CAD Cells Contain Less Energized Mitochondria

We have found earlier that vimentin IFs increase membrane potential of mitochondria in fibroblasts [

16]. Since neurite extension of neural cells is an energy consuming process, the energetic state of mitochondria is of great importance [

5]. So, it could be supposed that a temporary expression of vimentin in developing neurons ensure the troubleproof function of mitochondria.

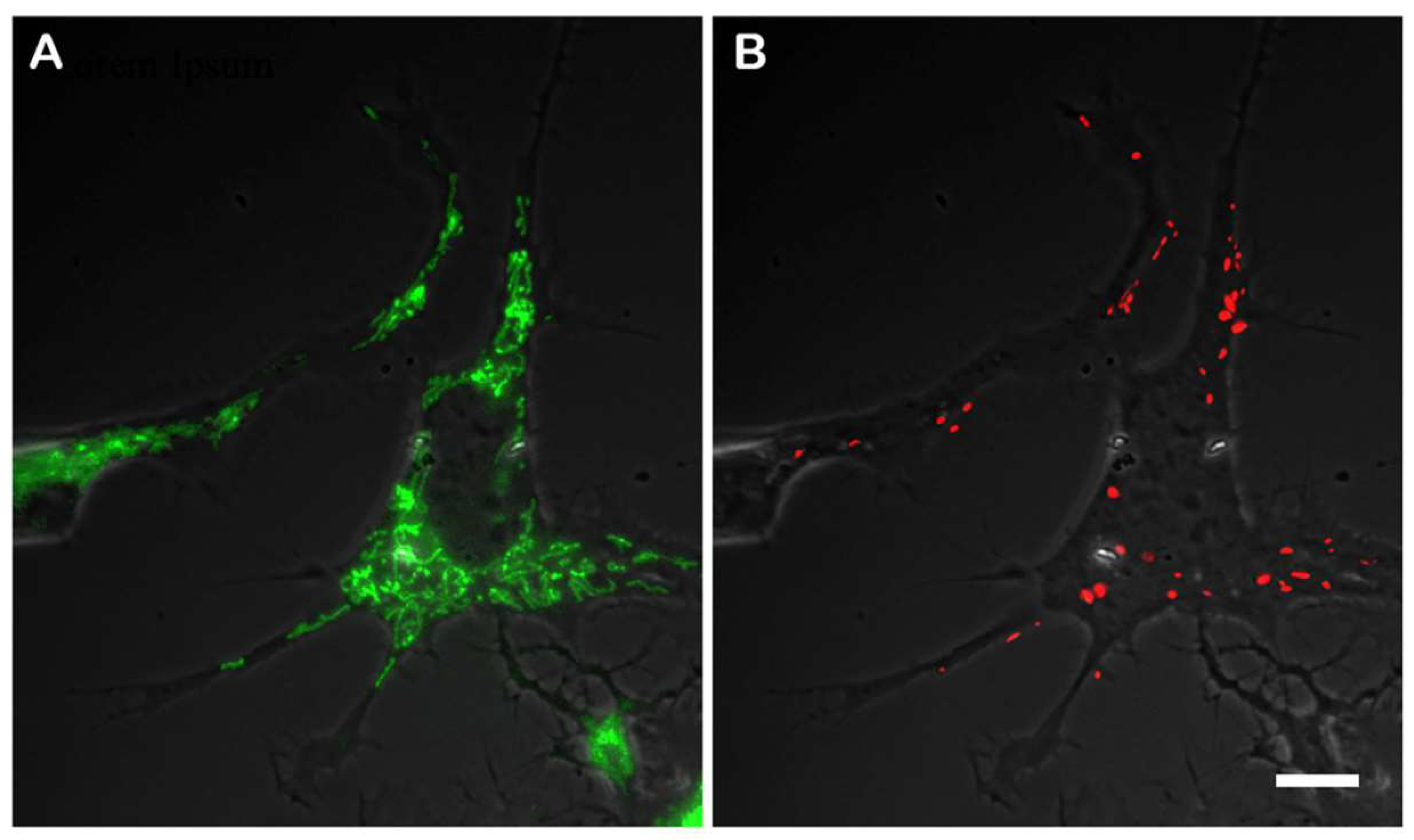

To compare the membrane potential in original CAD cells and the knockout CAD(Vim-/-) cells, we used mitochondria specific dye JC-1 to detect the highly energized mitochondria as those containing in the matrix J-aggregates having red fluorescence. The mitochondria with lower membrane potential remain of green color because the concentration of the dye is low. However, the probability of achieving a sufficient concentration of JC-1 to form red J-aggregates depends on the concentration of the dye added to the medium. Almost all mitochondria had green staining when the cells were incubated with 0.1 µg/ml of JC-1, whereas only few of them showed red staining. On the contrary, most mitochondria acquired red fluorescence when the cells were treated with 2.0 µg/ml of JC-1. Thus, we have chosen the intermediate concentration of JC-1 as the most convenient for quantification of proportion of mitochondria with higher potential. The

Figure 2 shows the CAD cells that was incubated with 1.0 µg/ml JC-1 that allows to reveal mitochondria with different levels of potential. It is clearly seen that among evenly distributed mitochondria with relatively low membrane potential those with higher potential localize at the periphery of the cell and in the processes. As far as vimentin IFs in differentiating CAD cells show increased density at the cellular periphery and in the processes (

Figure 1 A), it can be assumed that mitochondria with higher potential co-localize with vimentin.

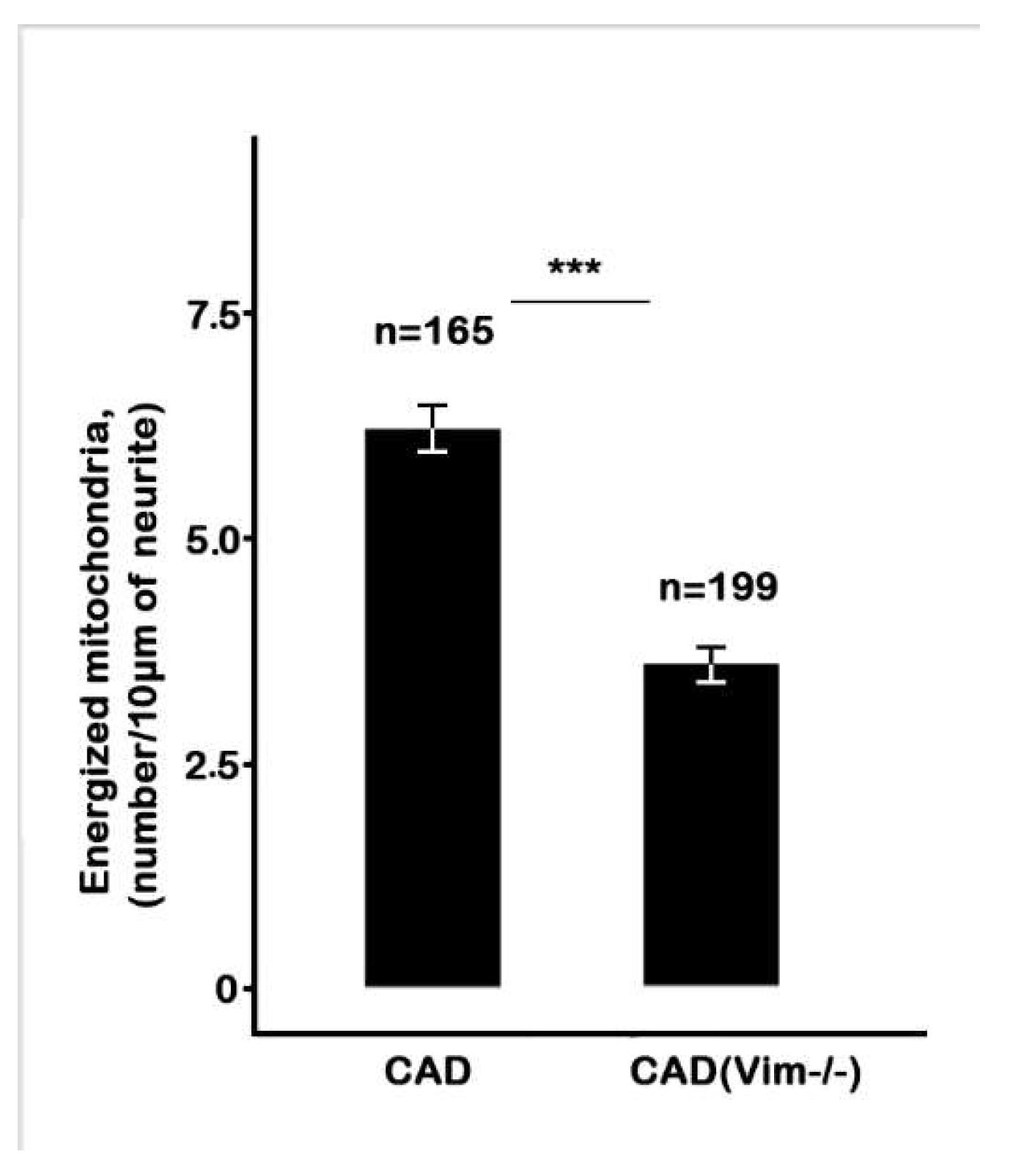

The staining of the CAD(Vim-/-) cells with JC-1 demonstrated that the number of mitochondria having higher potential is much lower than in vimentin-containing cells and such mitochondria are also localized in the processes more often than in cell bodies. The

Figure 3 shows that in cells containing vimentin IFs there are twice as much highly energized mitochondria than in vimentin-null cells.

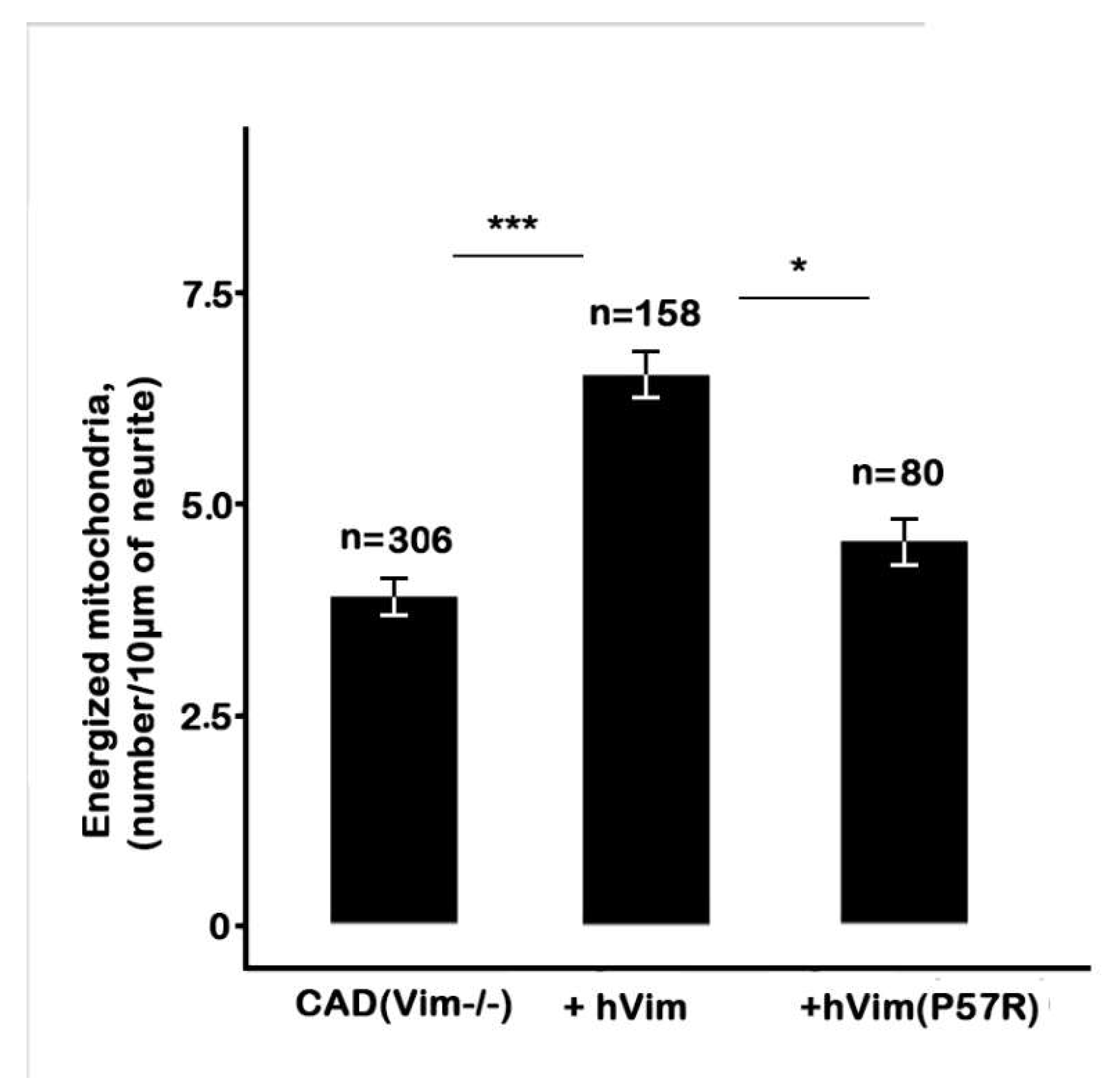

Recovery of Vimentin IFs in Knockout Cells Increases the Number of Energized Mitochondria

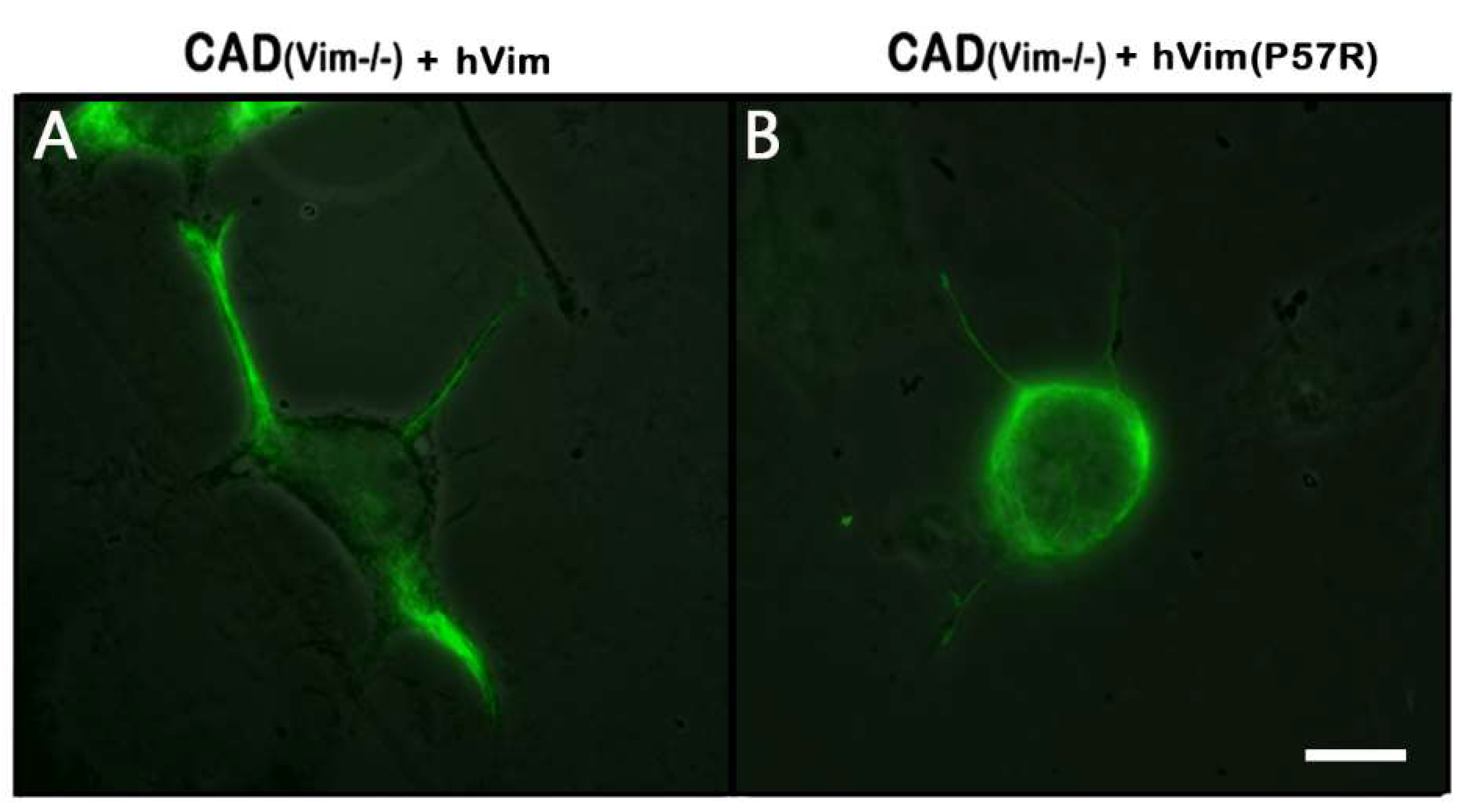

To make sure that the decrease of a mitochondrial potential in the CAD(Vim-/-) cells is in fact due to the absence of vimentin IFs, we transfected null cells with plasmid encoding human vimentin together with Chromobody against vimentin in order to detect transfected cells.

Figure 4 A shows that expression of recombinant protein fully restored vimentin IFs in CAD(Vim-/-) cells. The analysis of the mitochondrial membrane potential in transfected cells showed that an expression of vimentin caused increment in the number of mitochondria with high potential in contrast to cells expressing chromobody alone (

Figure 5). Interestingly, the expression of the mutated vimentin with replacement of Pro-57 with Arg which disrupts vimentin’s capacity to bind to mitochondria [

16] although reconstitutes filament network (

Figure 4 B), does not affect mitochondrial potential (

Figure 5).

Thus, our data show that vimentin is playing the role of the factor responsible for maintaining mitochondrial potential on the high level in the growing neurites independently from the other IFs, neurofilaments.

Discussion

The results obtained in this study support our initial hypothesis that vimentin plays a regulatory role in the maintenance of mitochondrial membrane potential in neurons. We have demonstrated that vimentin IFs are necessary for maintaining a higher mitochondrial potential in growing neurites, where energy demands are high. The absence of vimentin led to a decrease in mitochondrial potential in these neurites. Given that vimentin and neurofilaments are co-expressed in CAD cells, these results also suggest a unique role of vimentin in regulating of mitochondrial potential. These findings suggest that vimentin IFs are the integral factor for the regulation of the function of mitochondria within neurons, ensuring that energy production is efficiently matched to cellular needs.

Our findings provide further evidence that vimentin IFs play a significant role in mitochondrial dynamics, particularly in its ability to regulate mitochondrial membrane potential and their distribution within neurons. Interestingly, previous research has shown that the anchoring of mitochondria in neurons depends on the presence of a membrane potential and its interaction with neurofilaments, the major intermediate filaments (IFs) in neurons. Wagner with colleagues [

13] demonstrated that isolated mitochondria anchor to neurofilaments

in vitro, only when they maintain a stable membrane potential. Under conditions when the mitochondrial membrane potential was dissipated by the addition of uncoupling agents like valinomycin or FCCP, this anchoring was disrupted, and the neurofilaments detached from the mitochondria. This suggests that the interaction between IFs and mitochondria is closely tied to their bioenergetic status, particularly in the case of neurofilaments. Our study extends this concept to vimentin in CAD cells, where both neurofilaments and vimentin are co-expressed, indicating that vimentin may play a unique role in regulating mitochondrial function under conditions in which both types of IFs are present, such as during embryonic development or pathological states.

Furthermore, vimentin's ability to regulate the mitochondrial potential in the presence of neurofilaments raises important questions about the functional division between these intermediate filaments (IFs) in neurons. While neurofilaments are critical for maintaining axonal stability, especially in mature neurons, our study suggests that vimentin plays a more dynamic role in mitochondrial regulation, particularly in regions where rapid energy production is required in the growing neurites. Previous research has shown that fluctuations in mitochondrial potential are closely associated with essential processes such as synaptic activity and neuronal signaling [

26]. Our findings indicate that vimentin may help stabilize these fluctuations by ensuring that mitochondria with high potential are preferentially localized to areas with high metabolic demands, thus supporting key neuronal functions more effectively.

Finally, our study also reinforces earlier findings that mitochondrial dysfunction, particularly disruptions leading to dissipation of their potential, is a critical factor in neurodegenerative diseases. Pathological conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinson's disease are associated with impaired mitochondrial dynamics and neurofilament aggregation [

27]. In light of our results, vimentin could offer a protective mechanism in neurons by supporting mitochondrial function.

The implications of mitochondrial membrane potential in neuronal health and pathology are profound, as the threshold for its reduction that leads to apoptosis remains a critical point of investigation. Previous studies, such as those by Khodjakov and colleagues (2004) [

28], showed that partial mitochondrial depolarization in rat substantia nigra neurons—affecting 10-15% of mitochondria—did not immediately trigger apoptosis, even though mitochondrial damage occurred. Similarly, a reduction of mitochondrial potential from 158 mV to 108 mV in rat cortical neurons did not appear critical for cell survival [

29], while in other cell types, partial reduction of potential did lead to apoptotic signals [

30]. These findings suggest that heterogeneity of mitochondrial potential, both within single neurons and across cell populations, plays a role in determining the threshold for apoptosis.

In our study, we observed a significant drop in potential in vimentin-depleted neurons, particularly in neurites where energy demands are high. This reduction might not necessarily lead to immediate cell death but could impair mitochondrial efficiency and overall neuronal function. As highlighted in previous research, fluctuations in the level of mitochondrial potential are a normal physiological phenomenon [

31]; however, when these fluctuations are not properly regulated, such as in the absence of vimentin, the ability of neurons to sustain critical processes like synaptic transmission and axonal transport may be compromised. The observed potential drop in vimentin-depleted cells suggests that vimentin serves a protective role in maintaining mitochondrial function, particularly in regions of high metabolic demand. Without vimentin, mitochondria may be more susceptible to depolarization, which, if widespread or sustained, could lead to dysfunction or eventual cell death. This connection between mitochondrial potential and pathology has broad implications for understanding neurodegenerative diseases, where mitochondrial dysfunction and IF dysregulation is common. The reduced mitochondrial potential in vimentin-null cells may parallel the mitochondrial impairments seen in conditions like Parkinson's disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), where mitochondrial bioenergetics are often compromised.

Conclusion

Altogether, this study provide evidence for the important role of vimentin IFs in the growing neurons in the maintaining the appropriate level of mitochondrial membrane potential to meet the energy supply requirements throughout differentiation process.

Funding

This work was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (Grant No.23-74-00036 AAM).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Igor Kireev (Moscow University, Russia) for the help with the microscopy, and Natalia Minina for her skilled technical assistance.

References

- Cochard P, Paulin D. Initial expression of neurofilaments and vimentin in the central and peripheral nervous system of the mouse embryo in vivo. J Neurosci. 1984, 4, 2080–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boyne LJ, Fischer I, Shea TB. Role of vimentin in early stages of neuritogenesis in cultured hippocampal neurons. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1996, 14, 739–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, TB. Transient increase in vimentin in axonal cytoskeletons during differentiation in NB2a/d1 cells. Brain Res. 1990, 521, 338–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea TB, Beermann ML, Fischer I. Transient requirement for vimentin in neuritogenesis: intracellular delivery of anti-vimentin antibodies and antisense oligonucleotides inhibit neurite initiation but not elongation of existing neurites in neuroblastoma. J Neurosci Res. 1993, 36, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier JM, Rodrigues CM, Solá S. Mitochondria: Major Regulators of Neural Development. Neuroscientist. 2016, 22, 346–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris RL, Hollenbeck PJ. The regulation of bidirectional mitochondrial transport is coordinated with axonal outgrowth. J Cell Sci. 1993, 104, 917–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxton WM, Hollenbeck PJ. The axonal transport of mitochondria. J Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 2095–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gallo, G. The bioenergetics of neuronal morphogenesis and regeneration: Frontiers beyond the mitochondrion. Dev Neurobiol. 2020, 80, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruthel G, Hollenbeck PJ. Response of mitochondrial traffic to axon determination and differential branch growth. J Neurosci. 2003, 23, 8618–24 [PubMed: 13679431]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg J, Hollenbeck PJ. Mitochondrial membrane potential in axons increases with local nerve growth factor or semaphorin signaling. J Neurosci. 2008, 28, 8306–15 [PubMed: 18701693]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz N, Leube RE. Intermediate Filaments as Organizers of Cellular Space: How They Affect Mitochondrial Structure and Function. Cells. 2016, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alieva IB, Shakhov AS, Dayal AA, Churkina AS, Parfenteva OI, Minin AA. Unique Role of Vimentin in the Intermediate Filament Proteins Family. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2024, 89, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, O.I.; Lifshitz, J.; Janmey, P.A.; Linden, M.; McIntosh, T.K.; Leterrier, J.-F. Mechanisms of Mitochondria-Neurofilament Interactions. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 9046–9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leterrier, J.F.; Rusakov, D.A.; Nelson, B.D.; Linden, M. Interactions between brain mitochondria and cytoskeleton: Evidence for specialized outer membrane domains involved in the association of cytoskeleton-associated proteins to mitochondria in situ and in vitro. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1994, 27, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overly CC, Rieff HI, Hollenbeck PJ. Organelle motility and metabolism in axons vs dendrites of cultured hippocampal neurons. J Cell Sci. 1996, 109, 971–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernoivanenko I., S. , Matveeva E. A., Gelfand V. I., Goldman R. D., and Minin A. Mitochondrial membrane potential is regulated by vimentin intermediate filaments. FASEB J 2015, 29, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi Y, Wang JK, McMillian M, Chikaraishi DM. Characterization of a CNS cell line, CAD, in which morphological differentiation is initiated by serum deprivation. J Neurosci. 1997, 17, 1217–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013, 339, 819–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nekrasova OE, Mendez MG, Chernoivanenko IS et al. Vimentin intermediate filaments modulate the motility of mitochondria. Mol Biol Cell. 2011, 22, 2282–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maier J, Traenkle B, Rothbauer U. Real-time analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition using fluorescent single-domain antibodies. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 13402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Smiley ST, Reers M, Mottola-Hartshorn C et al. Intracellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial membrane potentials revealed by a J-aggregate-forming lipophilic cation JC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991, 88, 3671–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wagner OI, Lifshitz J, Janmey PA, Linden M, McIntosh TK, Leterrier JF. Mechanisms of mitochondria-neurofilament interactions. J Neurosci. 2003, 23, 9046–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laemmli U.K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–695.

- Dayal AA, Medvedeva NV, Nekrasova TM, Duhalin SD, Surin AK, Minin AA. Desmin interacts directly with mitochondria. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 8122. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Avsyuk AY, Khodyakov AL, Baibikova EM, Solovyanova OB, Nadezhdina ES (1997). Stability of vimentin intermediate filaments in interphasic cells. Dokl Rus Acad Nauk 357, 130–133.

- Miller KE, Sheetz MP. Axonal mitochondrial transport and potential are correlated. J Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 2791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israeli E, Dryanovski DI, Schumacker PT, et al. Intermediate filament aggregates cause mitochondrial dysmotility and increase energy demands in giant axonal neuropathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2016, 25, 2143–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khodjakov A, Rieder C, Mannella CA, Kinnally KW. Laser micro-irradiation of mitochondria: is there an amplified mitochondrial death signal in neural cells? Mitochondrion. 2004, 3, 217–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerencser AA, Chinopoulos C, Birket MJ, et al. Quantitative measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential in cultured cells: calcium-induced de- and hyperpolarization of neuronal mitochondria. J Physiol. 2012, 590, 2845–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gautier I, Geeraert V, Coppey J, Coppey-Moisan M, Durieux C. A moderate but not total decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential triggers apoptosis in neuron-like cells. Neuroreport. 2000, 11, 2953–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckman JF, Reynolds IJ. Spontaneous changes in mitochondrial membrane potential in cultured neurons. J Neurosci. 2001, 21, 5054–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).