Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

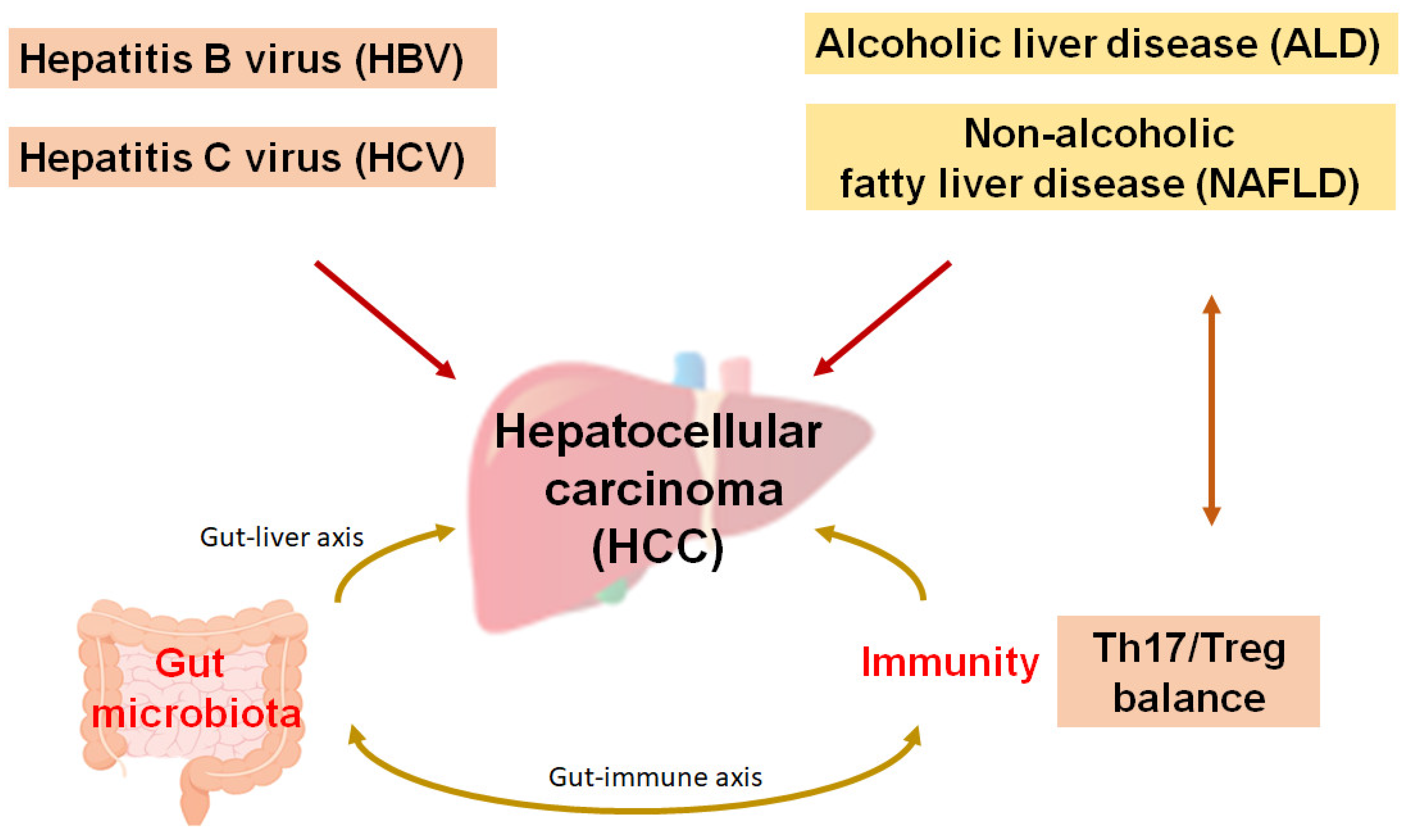

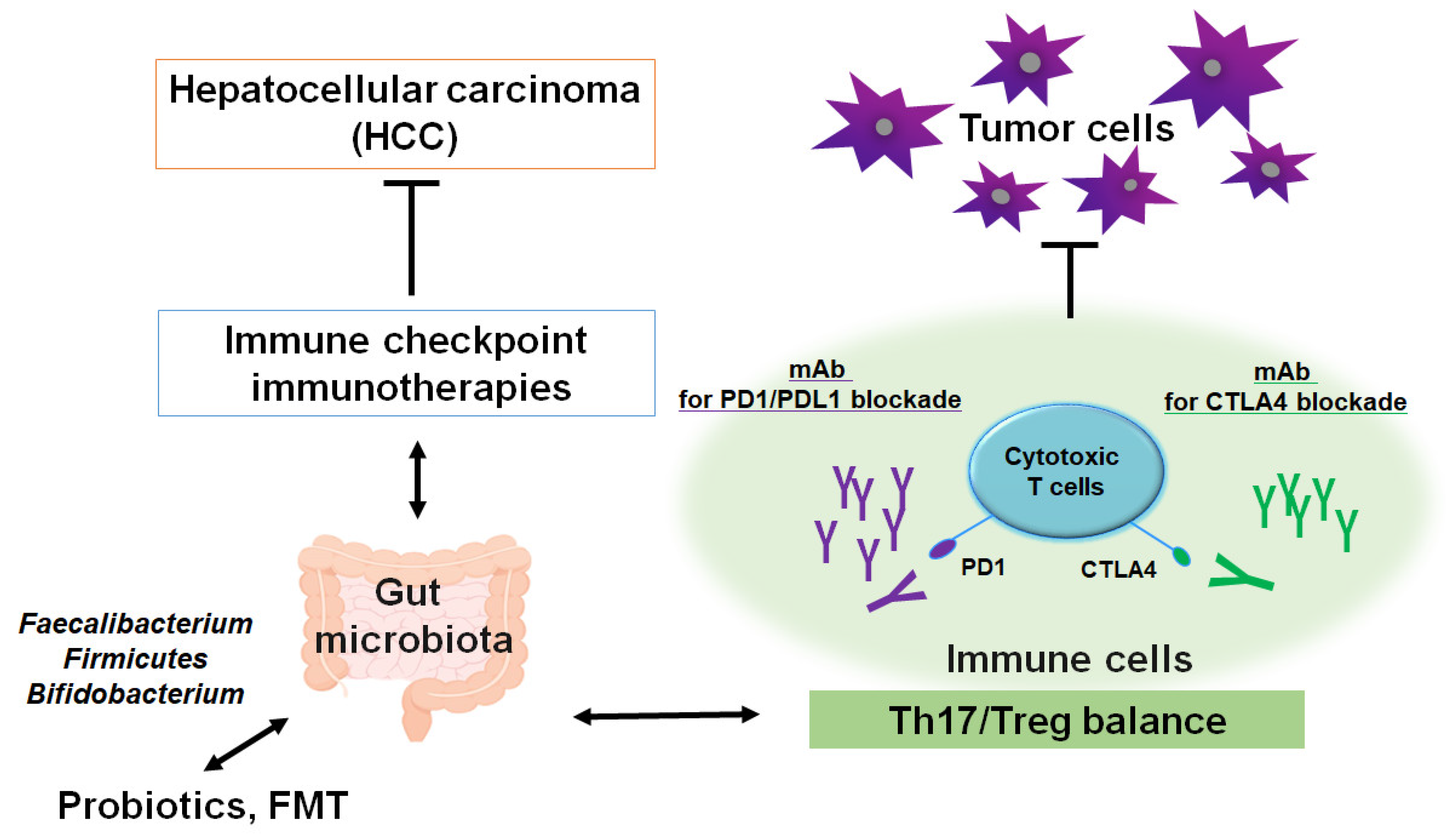

2. Possible Recent Cancer Therapies Against Hepatocellular Carcinoma

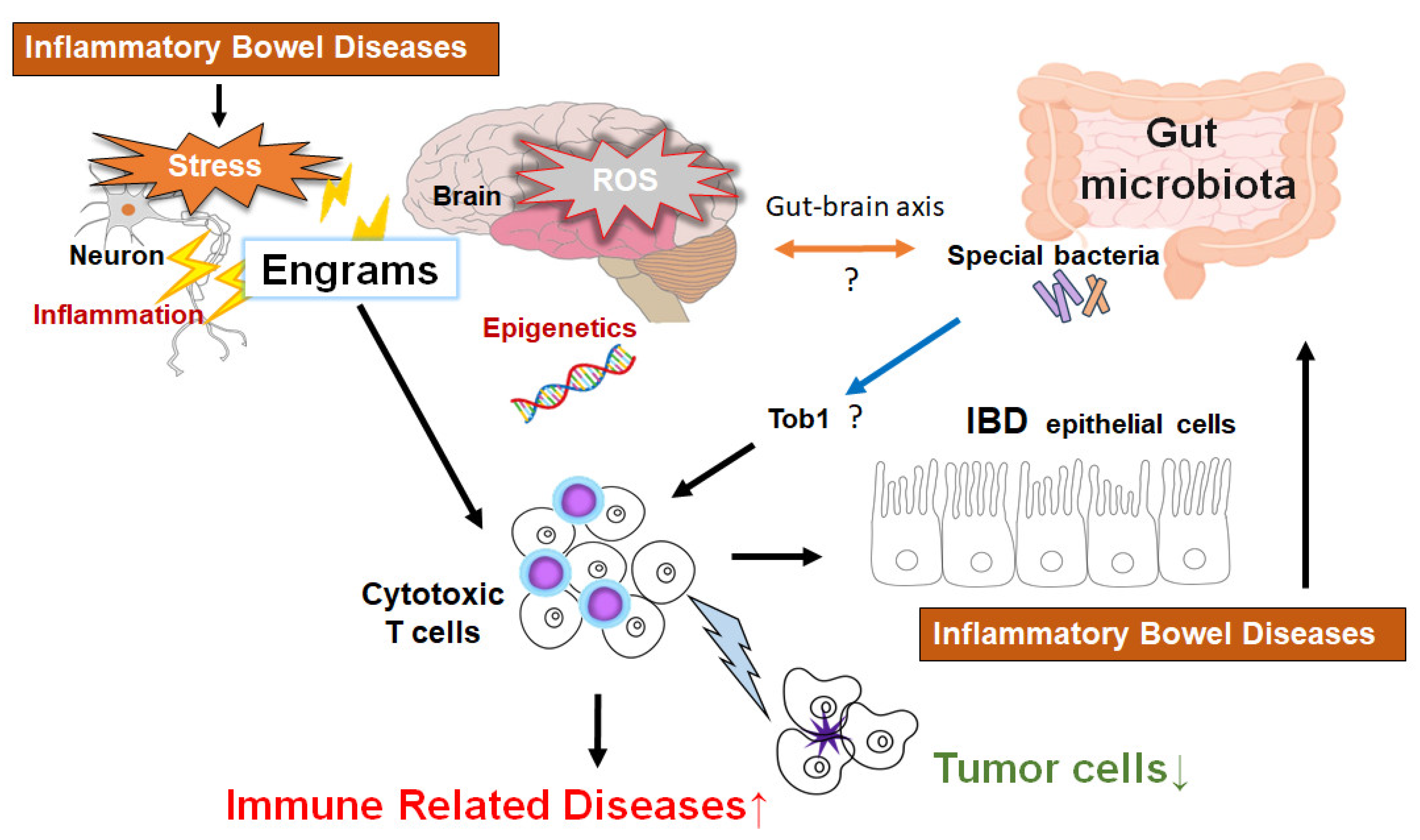

3. A New Concept for the Cancer Therapy

4. Epigenetics with Gut Microbiota Involved in Superior Cancer Therapy

5. Relationship Between Gut Microbiota and Epigenetics for the Superior Therapy Against HCC

6. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAR | chimeric antigen receptor |

| CTLA4 | cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| FMT | fecal microbiota transplantation |

| HBV | hepatitis B virus |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MHC | major histocompatibility complex |

| NAFLD | nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| PD-1 | programmed cell death protein-1 |

| PD-L1 | programmed cell death protein ligand-1 |

| PDT | photodynamic therapy |

| PTT | photothermal therapy |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SCFAs | short-chain fatty acids |

| STAT | signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| Th17 | T helper 17 cell |

| TLRs | toll-like receptors |

| Treg | regulatory T cell |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor A |

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018, 68(6), 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canale, M.; Ulivi, P.; Foschi, F.G.; Scarpi, E.; De Matteis, S.; Donati, G.; Ercolani, G.; Scartozzi, M.; Faloppi, L.; Passardi, A.; et al. Clinical and circulating biomarkers of survival and recurrence after radiofrequency ablation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018, 129, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, D.H.; Yoon, J.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yu, S.J.; Cho, E.J. Radiofrequency ablation using internally cooled wet electrodes in bipolar mode for the treatment of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after locoregional treatment: A randomized prospective comparative study. PLoS One. 2020, 15(9), e0239733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilagan, C.H.; Goldman, D.A.; Gönen, M.; Aveson, V.G.; Babicky, M.; Balachandran, V.P.; Drebin, J.A.; Jarnagin, W.R.; Wei, A.C.; Kingham, T.P.; et al. Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Complete Radiologic Response to Trans-Arterial Embolization: A Retrospective Study on Patterns, Treatments, and Prognoses. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022, 29(11), 6815–6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruix, J.; Qin, S.; Merle, P.; Granito, A.; Huang, Y.H.; Bodoky, G.; Pracht, M.; Yokosuka, O.; Rosmorduc, O.; Breder, V.; et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017, 389(10064), 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.Y.; Wei, H.Y.; Li, K.M.; Wang, R.B.; Xu, X.Q.; Feng, R. LINC00511 as a ceRNA promotes cell malignant behaviors and correlates with prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients by modulating miR-195/EYA1 axis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Kesarwala, A.H.; Eggert, T.; Medina-Echeverz, J.; Kleiner, D.E.; Jin, P.; Stroncek, D.F.; Terabe, M.; Kapoor, V.; ElGindi, M.; et al. NAFLD causes selective CD4(+) T lymphocyte loss and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature. 2016, 531(7593), 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehal, W.Z. The Gordian Knot of dysbiosis, obesity and NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013, 10(11), 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380(15), 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Desert, R.; Ge, X.; Han, H.; Song, Z.; Das, S.; Athavale, D.; You, H.; Nieto, N. The Matrisome Genes From Hepatitis B-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma Unveiled. Hepatol Commun. 2021, 5(9), 1571–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada-Vázquez, S.; Bone, C.; Saha, S.; Triguero, I.; Colom-Pellicer, M.; Aragonès, G.; Hildebrand, F.; Del Bas, J.M.; Caimari, A.; Beraza, N.; et al. Microbiota Dysbiosis and Gut Barrier Dysfunction Associated with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Are Modulated by a Specific Metabolic Cofactors' Combination. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23((22)), 13675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Okpara, E.S.; Hu, W.; Yan, C.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Chiang, J.Y.L.; Han, S. Interactive Relationships between Intestinal Flora and Bile Acids. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(15), 8343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tohme, S.; Simmons, R.L; Tsung, A. Surgery for Cancer: A Trigger for Metastases. Cancer Res. 2017, 77(7), 1548–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.R.; Mascitelli, L. Surgery and cancer promotion: are we trading beauty for cancer? QJM. 2011, 104(9), 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaverdian, N.; Lisberg, A.E.; Bornazyan, K.; Veruttipong, D.; Goldman, J.W.; Formenti, S.C.; Garon, E.B.; Lee, P. Previous radiotherapy and the clinical activity and toxicity of pembrolizumab in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: a secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18(7), 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiwert, T.Y.; Kiess, A.P. Time to Debunk an Urban Myth? The "Abscopal Effect" With Radiation and Anti-PD-1. J Clin Oncol. 2021, 39(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Verma, V.; Patel, R.R.; Barsoumian, H.B.; Cortez, M.A.; Welsh, J.W. Absolute Lymphocyte Count Predicts Abscopal Responses and Outcomes in Patients Receiving Combined Immunotherapy and Radiation Therapy: Analysis of 3 Phase 1/2 Trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020, 108(1), 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.; An, D.; Wan, C.; Yang, K. Radiotherapy: Brightness and darkness in the era of immunotherapy. Transl Oncol. 2022, 19, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, Y.; Ohsawa, I.; Terasaki, M.; Takahashi, M.; Kunugi, S.; Dedong, K.; Urushiyama, H.; Amenomori, S.; Kaneko-Togashi, M.; Kuwahara, N.; et al. Hydrogen therapy attenuates irradiation-induced lung damage by reducing oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011, 301(4), L415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundgren, S.; Karnevi, E.; Elebro, J.; Nodin, B.; Karlsson, M.C.I.; Eberhard, J.; Leandersson, K.; Jirström, K. The clinical importance of tumour-infiltrating macrophages and dendritic cells in periampullary adenocarcinoma differs by morphological subtype. J Transl Med. 2017, 15(1), 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryter, S.W.; Kim, H.P.; Hoetzel, A.; Park, J.W.; Nakahira, K.; Wang, X.; Choi, A.M. Mechanisms of cell death in oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007, 9(1), 49–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.J.; Singh, A.K.; Panipinto, P.M.; Shaikh, F.S.; Vinh, J.; Han, S.U.; Kenney, H.M.; Schwarz, E.M.; Crowson, C.S.; Khuder, S.A.; et al. Extracellular sulfatase-2 is overexpressed in rheumatoid arthritis and mediates the TNF-α-induced inflammatory activation of synovial fibroblasts. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022, 19(10), 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguz, S.; Yagüe, E. Resistance to chemotherapy: new treatments and novel insights into an old problem. Br J Cancer. 2008, 99(3), 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, H.; Kim, D.W. Chemotherapy and irradiation interaction. Semin Oncol. 2003, 30(4 Suppl 9), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, A.; Kelly, P.; Turkington, R.C.; Jones, C.; Coleman, H.G.; McCain, R.S. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2018, 24(43), 4846–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.S.; Verwilst, P.; Sharma, A.; Shin, J.; Sessler, J.L.; Kim, J.S. Organic molecule-based photothermal agents: an expanding photothermal therapy universe. Chem Soc Rev. 2018, 47(7), 2280–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Zhuang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 787780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lovell, J.F.; Yoon, J.; Chen, X. Clinical development and potential of photothermal and photodynamic therapies for cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020, 17(11), 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, X.; Liu, S.; Ge, N.; Liu, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Bao, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, H.; Cui, L. Photothermal effects of CuS-BSA nanoparticles on H22 hepatoma-bearing mice. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1029986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, A.; Leone, S.; Vaccaro, R.; Vivacqua, G.; Ceci, L.; Pannarale, L.; Franchitto, A.; Onori, P.; Gaudio, E.; Mancinelli, R. The Emerging Role of Ferroptosis in Liver Cancers. Life (Basel). 2022, 12(12), 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, S.H.E.; Dorhoi, A.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; Bartenschlager, R. Host-directed therapies for bacterial and viral infections. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018, 17(1), 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyck, L.; Mills, K.H.G. Immune checkpoints and their inhibition in cancer and infectious diseases. Eur J Immunol. 2017, 47(5), 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.C.; Duffy, C.R.; Allison, J.P. Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8(9), 1069–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas, A.; Wolchok, J.D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018, 359(6382), 1350–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korman, A.J.; Peggs, K.S.; Allison, J.P. Checkpoint blockade in cancer immunotherapy. Adv Immunol. 2006, 90, 297–339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bagchi, S.; Yuan, R.; Engleman, E.G. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for the Treatment of Cancer: Clinical Impact and Mechanisms of Response and Resistance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2021, 16, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.P.; Yano, H.; Vignali, D.A.A. Inhibitory receptors and ligands beyond PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA-4: breakthroughs or backups. Nat Immunol. 2019, 20(11), 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donisi, C.; Puzzoni, M.; Ziranu, P.; Lai, E.; Mariani, S.; Saba, G.; Impera, V.; Dubois, M.; Persano, M.; Migliari, M.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in the Treatment of HCC. Front Oncol. 2021, 10, 601240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, E.; Astara, G.; Ziranu, P.; Pretta, A.; Migliari, M.; Dubois, M.; Donisi, C.; Mariani, S.; Liscia, N.; Impera, V.; et al. Introducing immunotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients: Too early or too fast? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021, 157, 103167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greten, T.F.; Lai, C.W.; Li, G.; Staveley-O'Carroll, K.F. Targeted and Immune-Based Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019, 156(2), 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katariya, N.N.; Lizaola-Mayo, B.C.; Chascsa, D.M.; Giorgakis, E.; Aqel, B.A.; Moss, A.A.; Uson Junior, P.L.S.; Borad, M.J.; Mathur, A.K. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors as Therapy to Down-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma Prior to Liver Transplantation. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14(9), 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrahim, M.; Esmail, A.; Saharia, A.; Abudayyeh, A.; Abdel-Wahab, N.; Diab, A.; Murakami, N.; Kaseb, A.O.; Chang, J.C.; Gaber, A.O.; et al. Utilization of Immunotherapy for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Peri-Transplant Setting: Transplant Oncology View. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14(7), 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, D.B.; Rahnemai-Azar, A.A.; Pawlik, T.M. Potential experimental immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer of the liver. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2021, 30(8), 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tian, M.; Hu, X.; Wang, L.; Ji, J.; Liao, A. The altered PD-1/PD-L1 pathway delivers the 'one-two punch' effects to promote the Treg/Th17 imbalance in pre-eclampsia. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018, 15(7), 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.T.; Chu, Y.; Misoi, M.; Suarez-Almazor, M.E.; Tayar, J.H.; Lu, H.; Buni, M.; Kramer, J.; Rodriguez, E.; Hussain, Z.; et al. Distinct molecular and immune hallmarks of inflammatory arthritis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer therapy. Nat Commun. 2022, 13(1), 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okiyama, N.; Tanaka, R. Immune-related adverse events in various organs caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Allergol Int. 2022, 71(2), 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S, Na. Targeting interleukin-17 enhances tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in colorectal cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2022, 1877(4), 188758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, R.; Kozhaya, L.; McKevitt, K.; Djuretic, I.M.; Carlson, T.J.; Quintero, M.A.; McCauley, J.L.; Abreu, M.T.; Unutmaz, D.; Sundrud, M.S. Pro-inflammatory human Th17 cells selectively express P-glycoprotein and are refractory to glucocorticoids. J Exp Med. 2014, 211(1), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, A.; Routier, É.; Roy, S.; Pradere, P.; Le Pavec, J.; Pierre, T.; Chanson, N.; Scoazec, J.Y.; Lambotte, O.; Robert, C. Sarcoid-like Granulomatosis Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Melanoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14(12), 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs-Canner, S.; Berkey, S.; Delgoffe, G.M.; Edwards, R.P.; Curiel, T.; Odunsi, K.; Bartlett, D.L.; Obermajer, N. Suppressive IL-17A+Foxp3+ and ex-Th17 IL-17AnegFoxp3+ Treg cells are a source of tumour-associated Treg cells. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 14649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, S.A.; Local, A.; Carr, T.; Shakya, A.; Koul, S.; Hu, H.; Chourb, L.; Stedman, J.; Malley, J.; D'Agostino, L.A.; et al. Small molecule allosteric inhibitors of RORγt block Th17-dependent inflammation and associated gene expression in vivo. PLoS One. 2021, 16(11), e0248034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, T.; Verheij, J.; Gaudio, E.; Evert, M.; Guido, M.; Goeppert, B.; Carpino, G. Anatomical, histomorphological and molecular classification of cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 2019, 39 Suppl 1, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Harapan, B.N. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) immunotherapy: basic principles, current advances, and future prospects in neuro-oncology. Immunol Res. 2021, 69(6), 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Unity brings strength: Combination of CAR-T cell therapy and HSCT. Cancer Lett. 2022, 549, 215721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; Jung, H.; Noh, J.Y. Emerging Approaches for Solid Tumor Treatment Using CAR-T Cell Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(22), 12126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Yang, D.; Dai, H.; Liu, X.; Jia, R.; Cui, X.; Li, W.; Cai, C.; Xu, J.; Zhao, X. Eradication of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by NKG2D-Based CAR-T Cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019, 7(11), 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, A.; Bavetta, M.G.; Martinelli, E.; Bronte, F.; Giunta, E.F.; Manu, K.A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Therapeutic Algorithm for Localized and Advanced Disease. J Oncol. 2022, 2022, 3817724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, A.; Marelli, G.; Lemoine, N.R.; Wang, Y. Oncolytic Viruses-Interaction of Virus and Tumor Cells in the Battle to Eliminate Cancer. Front Oncol. 2017, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Wang, P.; He, S.; Zhu, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J. Progress and Prospect of Immunotherapy for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 919072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ying, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chen, K.; Ye, T.; Li, G. Effects of Oncolytic Vaccinia Viruses Harboring Different Marine Lectins on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(4), 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Xu, W.; Ying, Q.; Ni, J.; Jia, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, T.; Li, G.; Chen, K. Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus Carrying Aphrocallistes vastus Lectin (oncoVV-AVL) Enhances Inflammatory Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Mar Drugs. 2022, 20(11), 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Liu, Y.; Hussein, S.; Choi, G.; Kimchi, E.T.; Staveley-O'Carroll, K.F.; Li, G. The Species of Gut Bacteria Associated with Antitumor Immunity in Cancer Therapy. Cells. 2022, 11(22), 3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, S.; Wei, J.; Qu, L.; Pan, L.; Xu, K. The role of the gut microbiota and probiotics associated with microbial metabolisms in cancer prevention and therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1025860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Chen, X.; Gao, H.; Yang, F.; Chen, J.; Qiao, Y. Bacteria-mediated cancer therapy: A versatile bio-sapper with translational potential. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 980111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejman, D.; Livyatan, I.; Fuks, G.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Geller, L.T.; Rotter-Maskowitz, A.; Weiser, R.; Mallel, G.; Gigi, E.; et al. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type-specific intracellular bacteria. Scinence. 2020, 368(6494), 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Daca, A.; Fic, M.; van de Wetering, T.; Folwarski, M.; Makarewicz, W. Therapeutic methods of gut microbiota modification in colorectal cancer management - fecal microbiota transplantation, prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics. Gut Microbes. 2020, 11(6), 1518–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Taniguchi, K.; Yoshikawa, S.; Sawamura, H.; Tsuji, A.; Matsuda, S. A budding concept with certain microbiota, anti-proliferative family proteins, and engram theory for the innovative treatment of colon cancer. Explor Med. 2022, 3, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Qian, J.; Li, J. Saccharomyces boulardii alleviates ulcerative colitis carcinogenesis in mice by reducing TNF-α and IL-6 levels and functions and by rebalancing intestinal microbiota. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19(1), 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, L.Z.; Peng, K.; Wu, W.; Wu, R.; Liu, Z.Q.; Yang, G.; Geng, X.R.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.G.; et al. Specific immunotherapy in combination with Clostridium butyricum inhibits allergic inflammation in the mouse intestine. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 17651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchugonova, A.; Zhang, Y.; Salz, R.; Liu, F.; Suetsugu, A.; Zhang, L.; Koenig, K.; Hoffman, R.M.; Zhao, M. Imaging the Different Mechanisms of Prostate Cancer Cell-killing by Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35(10), 5225–5229. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; You, L.S.; Mao, L.P.; Jin, S.H.; Chen, X.H.; Qian, W.B. Combing oncolytic adenovirus expressing Beclin-1 with chemotherapy agent doxorubicin synergistically enhances cytotoxicity in human CML cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018, 39(2), 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Sui, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, C. Elemene injection as adjunctive treatment to platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis following the PRISMA guidelines. Phytomedicine. 2019, 59, 152787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Din, M.O.; Danino, T.; Prindle, A.; Skalak, M.; Selimkhanov, J.; Allen, K.; Julio, E.; Atolia, E.; Tsimring, L.S.; Bhatia, S.N.; et al. Synchronized cycles of bacterial lysis for in vivo delivery. Nature. 2016, 536(7614), 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNerney, M.P.; Doiron, K.E.; Ng, T.L.; Chang, T.Z.; Silver, P.A. Theranostic cells: emerging clinical applications of synthetic biology. Nat Rev Genet. 2021, 22(11), 730–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Luo, X.; Yang, D.; Li, Y.; Gong, T.; Li, B.; Cheng, J.; Chen, R.; Guo, X.; Yuan, W. Effects of probiotic supplementation on related side effects after chemoradiotherapy in cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 1032145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdelya, L.G.; Krivokrysenko, V.I.; Tallant, T.C.; Strom, E.; Gleiberman, A.S.; Gupta, D.; Kurnasov, O.V.; Fort, F.L.; Osterman, A.L.; Didonato, J.A.; et al. An agonist of toll-like receptor 5 has radioprotective activity in mouse and primate models. Science. 2008, 320(5873), 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, H. Beneficial effects of cellular autofluorescence following ionization radiation: hypothetical approaches for radiation protection and enhancing radiotherapy effectiveness. Med Hypotheses. 2015, 84(3), 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettegowda, C.; Dang, L.H.; Abrams, R.; Huso, D.L.; Dillehay, L.; Cheong, I.; Agrawal, N.; Borzillary, S.; McCaffery, J.M.; Watson, E.L.; et al. Overcoming the hypoxic barrier to radiation therapy with anaerobic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003, 100(25), 15083–15088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonacha, K.N.T.; Villa, T.G.; Notario, V. The Interplay among Radiation Therapy, Antibiotics and the Microbiota: Impact on Cancer Treatment Outcomes. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022, 11(3), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Cho, S.Y.; Yoon, Y.; Park, C.; Sohn, J.; Jeong, J.J.; Jeon, B.N.; Jang, M.; An, C.; Lee, S.; et al. Bifidobacterium bifidum strains synergize with immune checkpoint inhibitors to reduce tumour burden in mice. Nat Microbiol. 2021, 6(3), 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Q.; Yu, B.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Xie, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, S. Lysates of Lactobacillus acidophilus combined with CTLA-4-blocking antibodies enhance antitumor immunity in a mouse colon cancer model. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9(1), 20128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, Badi, S.; Moshiri, A.; Ettehad, Marvasti, F.; Mojtahedzadeh, M.; Kazemi, V.; Siadat, S.D. Extraction and Evaluation of Outer Membrane Vesicles from Two Important Gut Microbiota Members, Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Cell J 2020, 22(3), 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Vétizou, M.; Pitt, J.M.; Daillère, R.; Lepage, P.; Waldschmitt, N.; Flament, C.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Routy, B.; Roberti, M.P.; Duong, C.P.; et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science. 2015, 350(6264), 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Hong, N.; Yang, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, C. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii inhibits interleukin-17 to ameliorate colorectal colitis in rats. PLoS One. 2014, 9(10), e109146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Dorfman, R.G.; Liu, H.; Yu, T.; Chen, X.; Tang, D.; Xu, L.; Yin, Y.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Produces Butyrate to Maintain Th17/Treg Balance and to Ameliorate Colorectal Colitis by Inhibiting Histone Deacetylase 1. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018, 24(9), 1926–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Hupp, T.; Duchnowska, R.; Marek-Trzonkowska, N.; Połom, K. Next-generation probiotics - do they open new therapeutic strategies for cancer patients? Gut Microbes. 2022, 14(1), 2035659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behary, J.; Raposo, A.E.; Amorim, N.M.L.; Zheng, H.; Gong, L.; McGovern, E.; Chen, J.; Liu, K.; Beretov, J.; Theocharous, C.; et al. Defining the temporal evolution of gut dysbiosis and inflammatory responses leading to hepatocellular carcinoma in Mdr2 -/- mouse model. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21(1), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, F.R.; Bhoori, S.; Castelli, C.; Putignani, L.; Rivoltini, L.; Del Chierico, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; Morelli, D.; Paroni, Sterbini, F.; Petito, V.; et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Associated With Gut Microbiota Profile and Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2019, 69(1), 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Coker, O.O.; Chu, E.S.; Fu, K.; Lau, H.C.H.; Wang, Y.X.; Chan, A.W.H.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Dietary cholesterol drives fatty liver-associated liver cancer by modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Gut. 2021, 70(4), 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezasoltani, S.; Yadegar, A.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Reza, Zali, M. Modulatory effects of gut microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: A novel paradigm for blockade of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Med. 2021, 10(3), 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, L. Dynamic education of macrophages in different areas of human tumors. Cancer Microenviron. 2012, 5(3), 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, F.; Steele, J.C.; Herbert, J.M.; Steven, N.M.; Bicknell, R. Tumor stroma as a target in cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008, 8(6), 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.P.; Yan, J.; Xu, J.; Pang, X.H.; Chen, M.S.; Li, L.; Wu, C.; Li, S.P.; Zheng, L. Increased intratumoral IL-17-producing cells correlate with poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J Hepatol. 2009, 50(5), 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Hoechst, B.; Gamrekelashvili, J.; Ormandy, L.A.; Voigtländer, T.; Wedemeyer, H.; Ylaya, K.; Wang, X.W.; Hewitt, S.M.; Manns, M.P.; et al. Human CCR4+ CCR6+ Th17 cells suppress autologous CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol. 2012, 188(12), 6055–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Sun, J.; Wu, H.; Yi, Y.; Wang, J.X.; He, H.W.; Cai, X.Y.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, Y.F.; Fan, J.; et al. High expression of IL-17 and IL-17RE associate with poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013, 32(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, D.M.; Peng, C.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, Y.; Chen, M.S.; Zheng, L. Activated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of hepatocellular carcinoma promote expansion of memory T helper 17 cells. Hepatology. 2010, 51(1), 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelis, L.; Treß, M.; Löw, H.C.; Klees, J.; Klameth, C.; Lange, A.; Grießhammer, A.; Schäfer, A.; Menz, S.; Steimle, A.; et al. Gut Commensal-Induced IκBζ Expression in Dendritic Cells Influences the Th17 Response. Front Immunol. 2021, 11, 612336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.Y.; Lee, N.P.; El-Nezami, H. Regulation of T helper 17 by bacteria: an approach for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Hepatol. 2012, 2012, 439024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.M.; Li, Q.L.; Gao, Q.; Jiang, J.H.; Zhu, K.; Huang, X.Y.; Pan, J.F.; Yan, J.; Hu, J.H.; Wang, Z.; et al. IL-17 induces AKT-dependent IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 activation and tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2011, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Yuan, B.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. Utilizing Gut Microbiota to Improve Hepatobiliary Tumor Treatments: Recent Advances. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 924696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikó, E.; Vida, A.; Bai, P. Translational aspects of the microbiome-to be exploited. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2016, 32(3), 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, T.; Mikó, E.; Vida, A.; Sebő, É.; Toth, J.; Csonka, T.; Boratkó, A.; Ujlaki, G.; Lente, G.; Kovács, P.; et al. Cadaverine, a metabolite of the microbiome, reduces breast cancer aggressiveness through trace amino acid receptors. Sci Rep. 2019, 9(1), 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.X.; Schwabe, R.F. The gut microbiome and liver cancer: mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017, 14(9), 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, C.; Cui, J.; Lu, J.; Yan, C.; Wei, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, N.; Li, S.; Xue, G.; et al. Fatty Liver Disease Caused by High-Alcohol-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Metab. 2019, 30(4), 675–688.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapidot, Y.; Amir, A.; Nosenko, R.; Uzan-Yulzari, A.; Veitsman, E.; Cohen-Ezra, O.; Davidov, Y.; Weiss, P.; Bradichevski, T.; Segev, S.; et al. Alterations in the Gut Microbiome in the Progression of Cirrhosis to Hepatocellular Carcinoma. mSystems. 2020, 5(3), e00153–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Han, M.; Heinrich, B.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Sandhu, M.; Agdashian, D.; Terabe, M.; Berzofsky, J.A.; Fako, V.; et al. Gut microbiome-mediated bile acid metabolism regulates liver cancer via NKT cells. Science. 2018, 360(6391), eaan5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018, 359(6371), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; Prieto, P.A.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C.; et al. , Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018, 359(6371), 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, V.; Fessler, J.; Bao, R.; Chongsuwat, T.; Zha, Y.; Alegre, M.L.; Luke, J.J.; Gajewski, T.F. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science. 2018, 359(6371), 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, S.; Loo, T.M.; Atarashi, K.; Kanda, H.; Sato, S.; Oyadomari, S.; Iwakura, Y.; Oshima, K.; Morita, H.; Hattori, M.; et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature. 2013, 499(7456), 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapito, D.H.; Mencin, A.; Gwak, G.Y.; Pradere, J.P.; Jang, M.K.; Mederacke, I.; Caviglia, J.M.; Khiabanian, H.; Adeyemi, A.; Bataller, R.; et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell. 2012, 21(4), 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, D.; Jiang, W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, P.; Song, R.; et al. Gut microbiome affects the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7(1), 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, M.R.; Aggarwal, P.; Costa, R.G.F.; Cole, A.M.; Trinchieri, G. Targeting the gut microbiota for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022, 22(12), 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, E.; Zhu, Z.; Wahed, S.; Qu, Z.; Storkus, W.J.; Guo, Z.S. Epigenetic modulation of antitumor immunity for improved cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2021, 20(1), 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, M.L.; Sparbier, C.E.; Chan, K.L.; Chan Y.C.; Kersbergen, A.; Lam E.Y.N.; Azidis-Yates E.; Vassiliadis D.; Bell C.C.; Gilan O.; et al. An evolutionarily conserved function of polycomb silences the MHC class I antigen presentation pathway and enables immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019, 36(4), 385–401. e8.

- Greger, V.; Passarge, E.; Höpping, W.; Messmer, E.; Horsthemke, B. Epigenetic changes may contribute to the formation and spontaneous regression of retinoblastoma. Hum Genet. 1989, 83(2), 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Liang, G.; Egger, G.; Friedman, J.M.; Chuang, J.C.; Coetzee, G.A.; Jones, P.A. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2006, 9(6), 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senga, S.S.; Grose, R.P. Hallmarks of cancer-the new testament. Open Biol. 2021, 11(1), 200358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; He, X.; Wang, Q. Intratumoral bacteria are an important “accomplice” in tumor development and metastasis. Biochim. Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2023, 1878(1), 188846. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C.; Mai, Q.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lin, T.; et al. The gut microbiota mediates protective immunity against tuberculosis via modulation of lncRNA. Gut Microbes. 2022, 14(1), 2029997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niller, H.H.; Minarovits, J. Patho-epigenetics of Infectious Diseases Caused by Intracellular Bacteria. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016, 879, 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Luu, M.; Schütz, B.; Lauth, M.; Visekruna, A. The Impact of Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites on the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15(5), 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Gaboriau-Routhiau, V. The immune system and the gut microbiota: Friends or foes? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010, 10(10), 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledezma, D.K.; Balakrishnan, P.B.; Cano-Mejia, J.; Sweeney, E.E.; Hadley, M.; Bollard, C.M.; Villagra, A.; Fernandes, R. Indocyanine Green-Nexturastat A-PLGA Nanoparticles Combine Photothermal and Epigenetic Therapy for Melanoma. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2020, 10(1), 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachowska, M.; Gabrysiak, M.; Muchowicz, A.; Bednarek, W.; Barankiewicz, J.; Rygiel, T.; Boon, L.; Mroz, P.; Hamblin, M.R.; Golab, J. 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine potentiates antitumour immune response induced by photodynamic therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2014, 50(7), 1370–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachowska, M.; Muchowicz, A.; Golab, J. Targeting Epigenetic Processes in Photodynamic Therapy-Induced Anticancer Immunity. Front Oncol. 2015, 5, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifylli, E.M.; Koustas, E.; Papadopoulos, N.; Sarantis, P.; Aloizos, G.; Damaskos, C.; Garmpis, N.; Garmpi, A.; Karamouzis, M.V. An Insight into the Novel Immunotherapy and Targeted Therapeutic Strategies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Cholangiocarcinoma. Life (Basel). 2022, 12(5), 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014, 11(8), 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, F.; Macchini, F.; Massimo, Castagna, V. Safety of probiotics in humans: A dark side revealed? Dig Liver Dis. 2020, 52(9), 981–985. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.; Sinopoulou, V.; Gordon, M.; Akobeng, A.K.; Llanos-Chea, A.; Hungria, G.; Febo-Rodriguez, L.; Fifi, A.; Fernandez Valdes, L.; Langshaw, A.; et al. Probiotics for treatment of chronic constipation in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022, 3(3), CD014257. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. A potential species of next-generation probiotics? The dark and light sides of Bacteroides fragilis in health. Food Res Int. 2019, 126, 108590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, A.S.; Chow, A.W.; Betts, D.; Guze, L.B. Lactobacillemia--report of nine cases. Important clinical and therapeutic considerations. Am J Med. 1978, 64(5), 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickgiesser, U.; Weiss, N.; Fritsche, D. Lactobacillus gasseri as the cause of septic urinary infection. Infection. 1984, 12(1), 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.P.; Yang, M.; Ito, S. Activation of nuclear factor (erythroid-2 like) factor 2 by toxic bile acids provokes adaptive defense responses to enhance cell survival at the emergence of oxidative stress. Mol Pharmacol. 2007, 72(5), 1380–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiam-Galvez, K.J.; Allen, B.M.; Spitzer, M.H. Systemic immunity in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021, 21(6), 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, M.; Forner, A.; Rimola, J.; Ferrer-Fàbrega, J.; Burrel, M.; Garcia-Criado, Á.; Kelley, R.K.; Galle, P.R.; Mazzaferro, V.; Salem, R.; et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022, 76(3), 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, B.; Wu, C.; Guo, X. Advances in the Involvement of Gut Microbiota in Pathophysiology of NAFLD. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020, 7, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.L.; Wilson, I.D.; Teare, J.; Marchesi, J.R.; Nicholson, J.K.; Kinross, J.M. Gut microbiota modulation of chemotherapy efficacy and toxicity. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017, 14(6), 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaida, N. Intestinal microbiota: unexpected alliance with tumor therapy. Immunotherapy. 2014, 6(3), 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, N.; Dzutsev, A.; Stewart, C.A.; Smith, L.; Bouladoux, N.; Weingarten, R.A.; Molina, D.A.; Salcedo, R.; Back, T.; Cramer, S.; et al. Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2013, 342(6161), 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagadala, M.; Sears, T.J.; Wu, V.H.; Pérez-Guijarro, E.; Kim, H.; Castro, A.; Talwar, J.V.; Gonzalez-Colin, C.; Cao, S.; Schmiedel, B.J.; et al. Germline modifiers of the tumor immune microenvironment implicate drivers of cancer risk and immunotherapy response. Nat Commun. 2023, 14(1), 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, S.; Taniguchi, K.; Sawamura, H, Ikeda Y, Tsuji A, Matsuda S.Encouraging probiotics for the prevention and treatment of immune-related adverse events in novel immunotherapies against malignant glioma. Explor Target Antitumor Ther. 2022, 3(6), 817–827.

- Ayob, A.Z.; Ramasamy, T.S. Cancer stem cells as key drivers of tumour progression. J Biomed Sci. 2018, 25(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza, Treviño, E.N.; González, P.D.; Valencia, Salgado, C.I.; Martinez, Garza, A. Effects of pericytes and colon cancer stem cells in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, S.; Taniguchi, K.; Sawamura, H.; Ikeda, Y.; Tsuji, A.; Matsuda, S. A New Concept of Associations between Gut Microbiota, Immunity and Central Nervous System for the Innovative Treatment of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Metabolites. 2022, 12(11), 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).