Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Integrated infrastructure planning between two cities is a coordinated approach that aligns infrastructure systems such as transportation networks, waste management, water supply, and digital connectivity across municipal boundaries. This type of regional planning creates synergy between neighboring cities, helping achieve broader economic, environmental, and social objectives. In particular, it emphasizes improved connectivity, resource sharing, and resilience, all of which support regional growth, reduce redundancies, and ensure that infrastructure systems work efficiently for both cities. On the other hand, disjointed approaches to infrastructure development could lead to unsustainable urban sprawl, traffic jams, poor public service delivery, environmental degradation, inefficiencies, and inequality. The study used a mixed-methods approach, using convenience sampling techniques and collected data through questionnaires, surveys, interviews, and focus group discussions, which was analyzed using Microsoft Excel, ArcGIS, and SPSS. The study examines infrastructure systems and planning practices in Addis Ababa and Sheger, focusing on efficiency improvements in sewerage and drainage management, waste management, and transportation networks. It also analyzes challenges and provides recommendations for effective inter-city coordination.

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and method

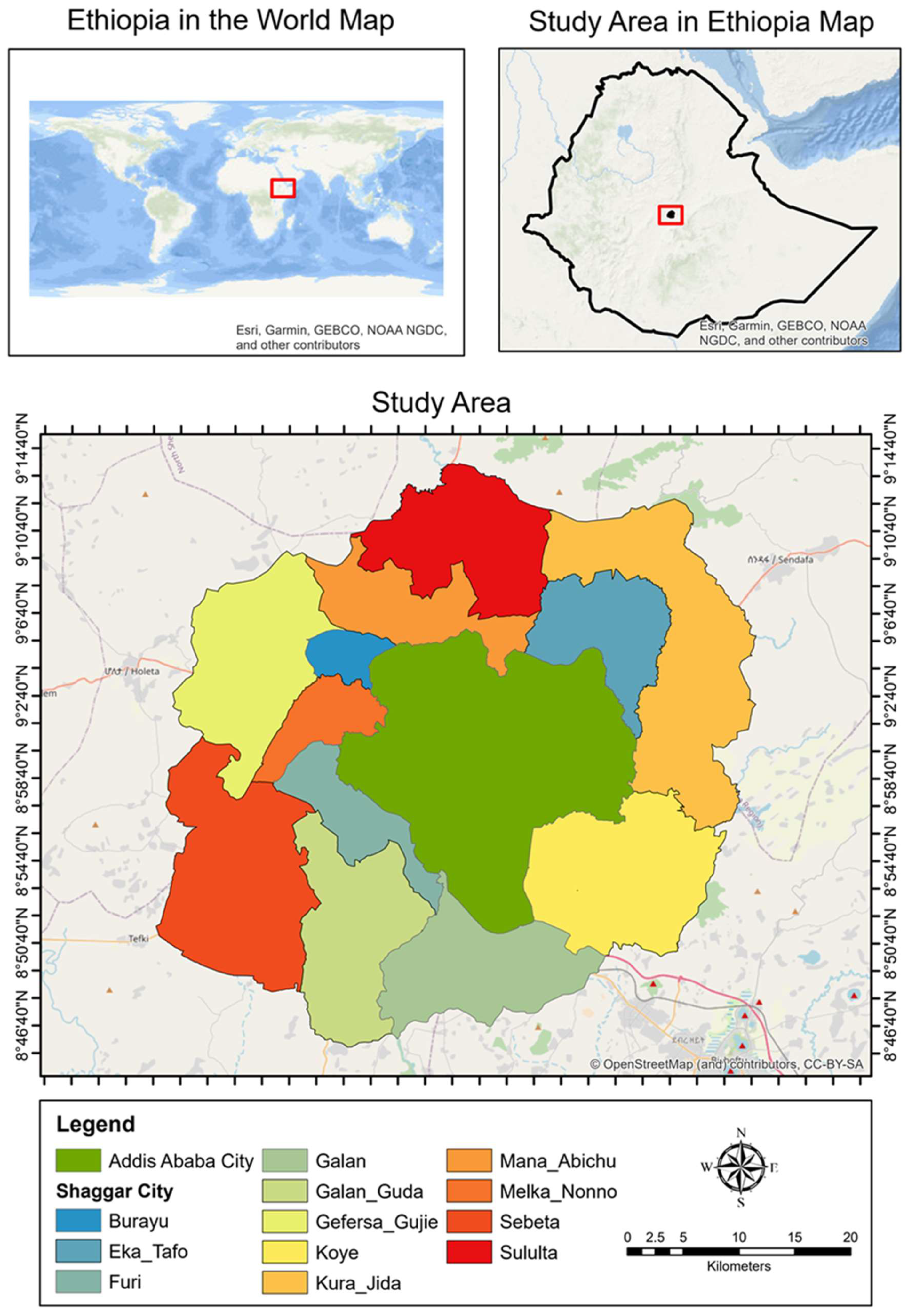

2.1. Study area

2.2. Research Methodology

- What is the current state of infrastructure and planning practices in Addis Ababa and Sheger, and where are the critical points of interdependence?

- How can integrated infrastructure planning contribute to resource efficiency and service improvement in both cities?

- What are the main challenges to implementing integrated infrastructure planning, especially regarding governance and policy coherence?

- How can Addis Ababa and Sheger practically adopt a framework for coordinated infrastructure planning, and what best practices could be adapted from other regions?

2.3. Data Types and sources

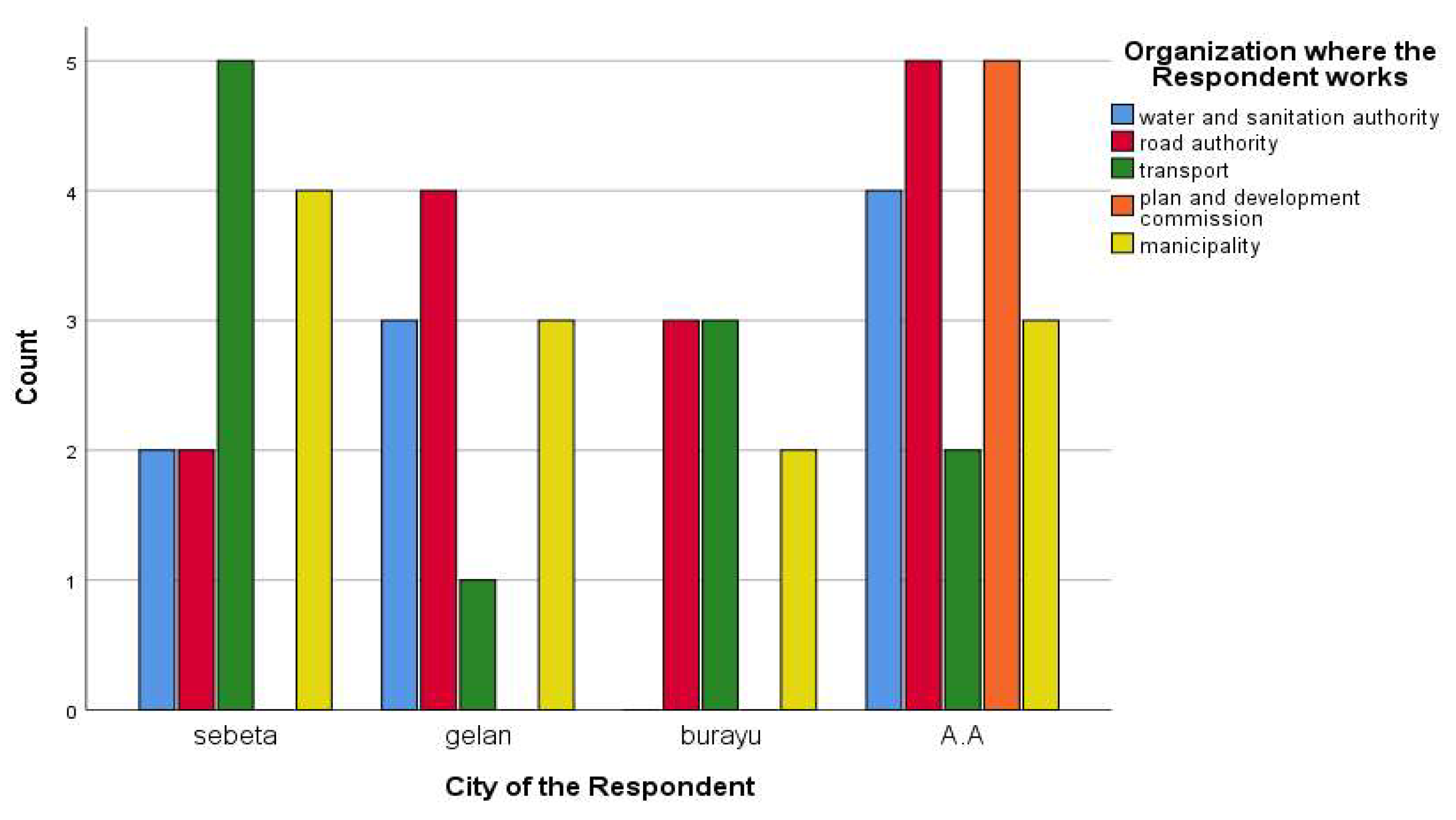

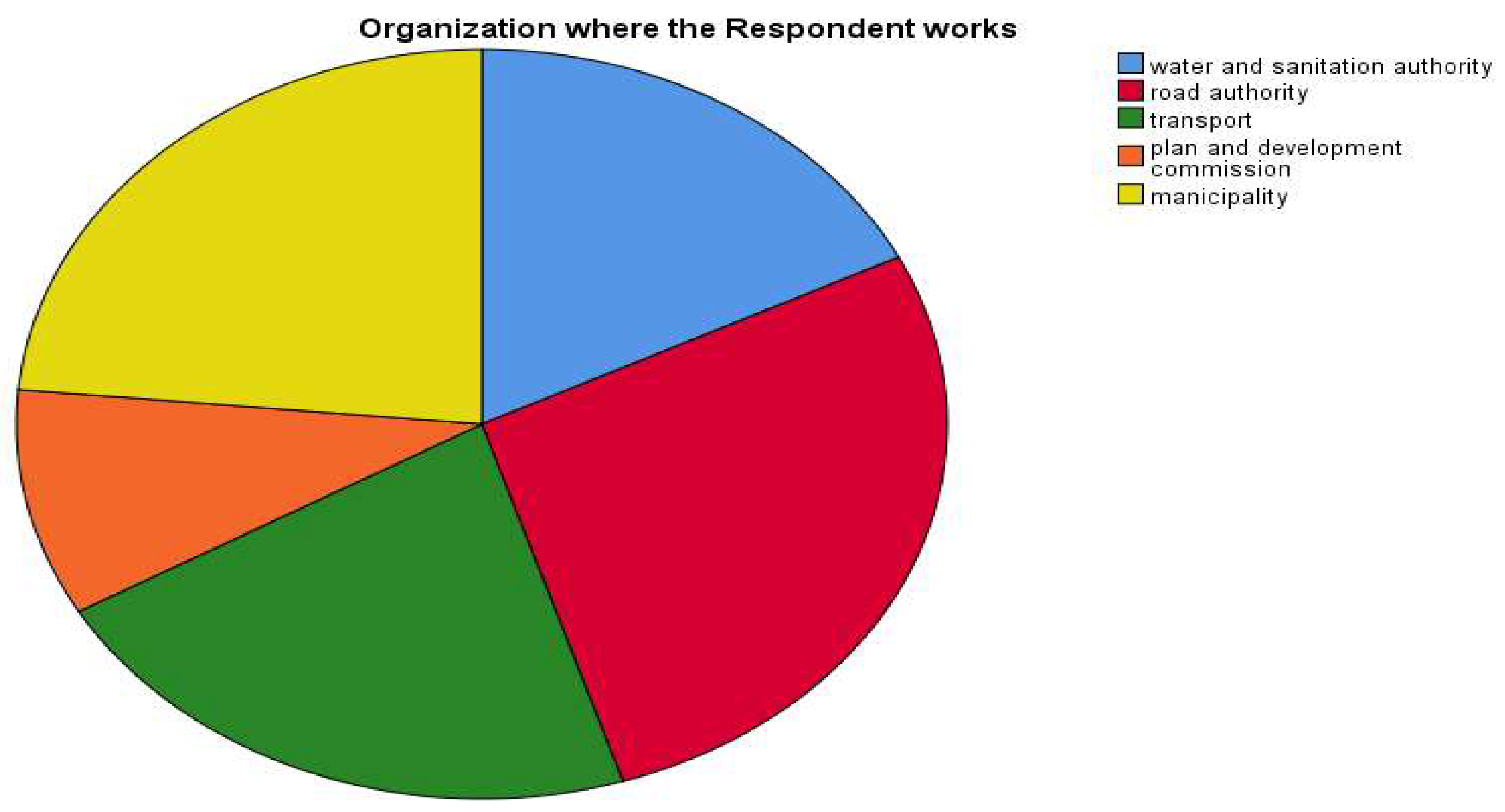

2.4. Sampling techniques and determining sample size

2.5. Data Collection Methods

2.7. Data Presentation

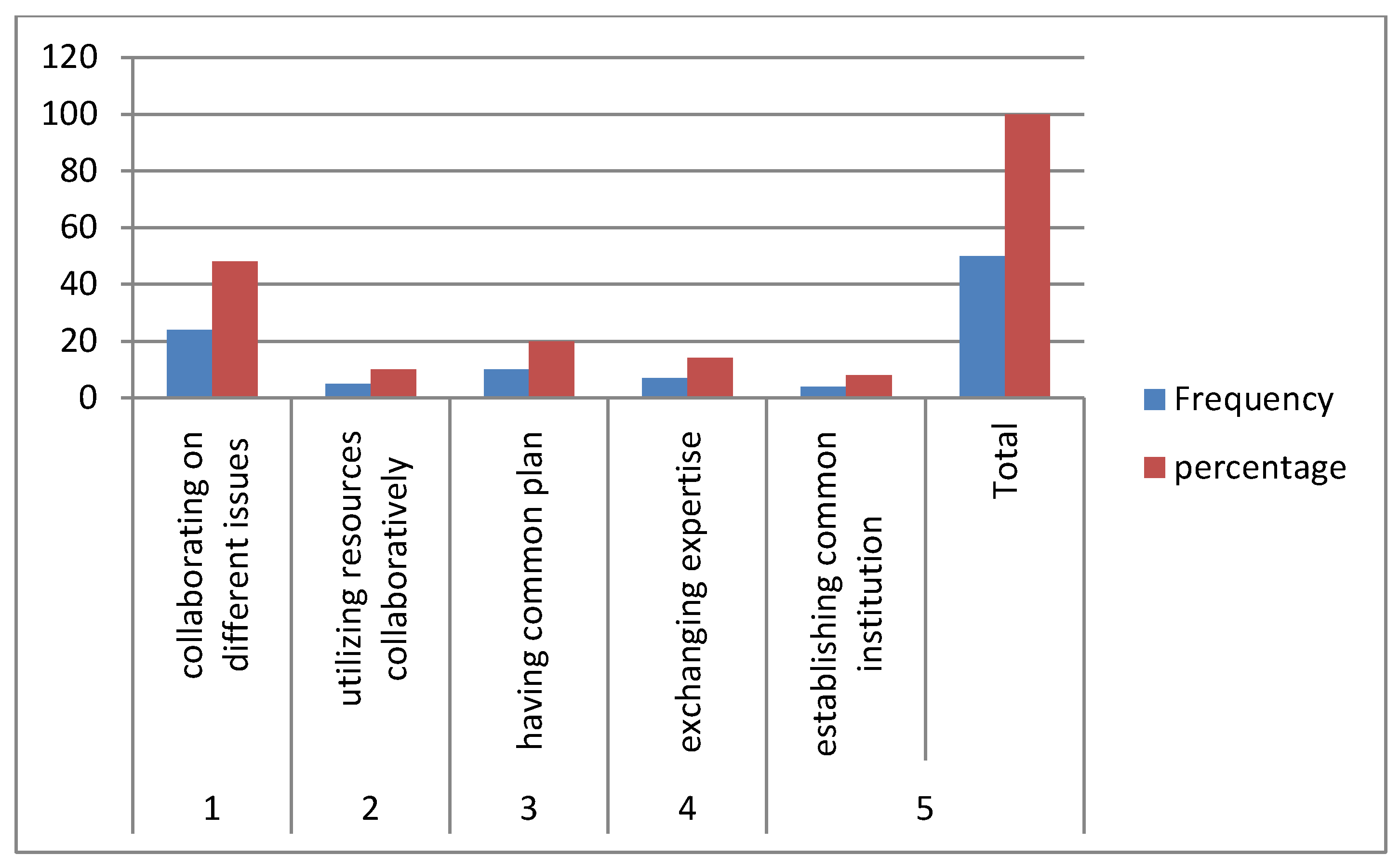

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Sewerage system

3.2. Drainage system

3.3 Solid waste management

3.4 Transport and road network system

4. Conclusion and recommendations

4.1. Conclusion

4.2. Recommendations

- ✓

- The concerned body, particularly the cities administration should establish a legal framework for cooperation

- ✓

- The cities administration planning institutes should develop integrated infrastructure plan for well-coordinated infrastructure management

- ✓

- The cities Road Authority should expand flood protection and stormwater management

- ✓

- The Federal Government and the cities administration should create institutional support for ongoing collaboration

- ✓

- The cities administration should encourage public and political support for integration

- ✓

- The cities administration and concerned body should improve transportation connectivity and infrastructure quality.

- ✓

- The Federal Government and the cities administration should address economic, political, and administrative barriers to integration.

- ✓

- The cities administration and concerned body should enhance infrastructure coordination levels

Declarations

References

- Bhattacharya, A.; Oppenheim, J.; Stern, N. Driving sustainable development through better infrastructure: Key elements of a transformation program. Brookings Global Working Paper Series 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidehpour, M.; Li, Z.; Ganji, M. Smart cities for a sustainable urbanization: Illuminating the need for establishing smart urban infrastructures. IEEE Electrification magazine 2018, 6, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinderhughes, R. Alternative urban futures: Planning for sustainable development in cities throughout the world; Rowman & Littlefield: 2004.

- Li, E. Governing Collaborative Planning Initiatives for Equitable Transit-oriented Development: A Case Study of the Purple Line Corridor Coalition in Maryland. Technische Universität Berlin, 2023.

- Brown, H. Next generation infrastructure; Springer: 2014.

- Silva, B.N.; Khan, M.; Han, K. Towards sustainable smart cities: A review of trends, architectures, components, and open challenges in smart cities. Sustainable cities and society 2018, 38, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, E.L. Assessment of transport infrastructure plans: A strategic approach integrating efficiency, cohesion and environmental aspects. Madrid University of Politics, Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adshead, D.; Thacker, S.; Fuldauer, L.I.; Hall, J.W. Delivering on the Sustainable Development Goals through long-term infrastructure planning. Global Environmental Change 2019, 59, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Cervero, R.; Iuchi, K. Transforming cities with transit: Transit and land-use integration for sustainable urban development; World Bank Publications: 2013.

- Cervero, R. Linking urban transport and land use in developing countries. Journal of transport and land use 2013, 6, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mooney, H.; Hull, V.; Davis, S.J.; Gaskell, J.; Hertel, T.; Lubchenco, J.; Seto, K.C.; Gleick, P.; Kremen, C. Systems integration for global sustainability. Science 2015, 347, 1258832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleta, J.; Mikulčić, H.; Klemeš, J.J.; Urbaniec, K.; Duić, N. Integration of energy, water and environmental systems for a sustainable development. Journal of cleaner production 2019, 215, 1424–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, K.; Kartha, S. Land-based negative emissions: risks for climate mitigation and impacts on sustainable development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 2018, 18, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storper, M. Keys to the city: How economics, institutions, social interaction, and politics shape development; Princeton University Press: 2013.

- Hall, P.V.; Hesse, M. Cities, regions and flows; Routledge Londres/Nueva New York: 2013; Vol. 439.

- Ravetz, J. City-region 2020: Integrated planning for a sustainable environment; Routledge: 2016.

- Davoudi, S. Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Urban Design and Planning 2008, 161, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranoff, R. Managing collaborative performance: Changing the boundaries of the state? Public Performance & Management Review 2005, 29, 18–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cleophas, C.; Cottrill, C.; Ehmke, J.F.; Tierney, K. Collaborative urban transportation: Recent advances in theory and practice. European Journal of Operational Research 2019, 273, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, K.S.; Feldman, M.S. Boundaries as junctures: Collaborative boundary work for building efficient resilience. Journal of public administration research and theory 2014, 24, 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margerum, R.D. Beyond consensus: Improving collaborative planning and management; Mit Press: 2011.

- Stebek, E.N. Vol. 10 No. 1: The Constitutional Right to Enhanced Livelihood in Ethiopia: Unfulfilled Promises and the Need for New Approaches. 2016.

- Weldeghebrael, E.H. Addis Ababa: City Scoping Study. African Cities Research Consortium, The University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Erena, D.; Berhe, A.; Hassen, I.; Mamaru, T.; Soressa, Y. City profile: Addis Ababa. Report prepared in the SES (Social Inclusion and Energy Management for Informal Urban Settlements) project, funded by the Erasmus+ Program of the European Union. 2017.

- YARED, A.A. QUALITY ASSESSMENT OF RAW AND PASTEURIZED MILK AMONG DAIRY PRODUCT VENDORS, ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA. 2024.

- Woldeamanuel, M. Urban Issues in Rapidly Growing Cities: Planning for Development in Addis Ababa; Routledge: 2020.

- Kasa, L.; Zeleke, G.; Alemu, D.; Hagos, F.; Heinimann, A. Impact of urbanization of Addis Abeba city on peri-urban environment and livelihoods. Sekota Dry land Agricultural Research Centre of Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institute: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Fetters, M.D.; Creswell, J.W. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. The Annals of Family Medicine 2015, 13, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almalki, S. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Data in Mixed Methods Research--Challenges and Benefits. Journal of education and learning 2016, 5, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiee, M.; Wang, S.C.; Creswell, J.W. Designing community-based mixed methods research. 2012.

- Akyıldız, S.T.; Ahmed, K.H. An overview of qualitative research and focus group discussion. International Journal of Academic Research in Education 2021, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofisi, C.; Hofisi, M.; Mago, S. Critiquing interviewing as a data collection method. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 2014, 5, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Weisner, T.S.; Kalil, A.; Way, N. Mixing qualitative and quantitative research in developmental science: uses and methodological choices. 2013.

- Schensul, J.J.; LeCompte, M.D. Essential ethnographic methods: A mixed methods approach; Rowman Altamira: 2012.

- Wehrmann, B. Land conflicts: A practical guide to dealing with land disputes; GTZ Eschborn: 2008.

- Kliot, N.; Shmueli, D.; Shamir, U. Institutions for management of transboundary water resources: their nature, characteristics and shortcomings. Water Policy 2001, 3, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.; Dickin, S.; Rosemarin, A. Towards “sustainable” sanitation: challenges and opportunities in urban areas. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TuCCi, C.E. Urban waters. estudos avançados 2008, 22, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyewunmi, T. Challenges and potential solutions to pluvial flood risk in urban tropical African communities, a case study using Ijebu-Ode, in South West Nigeria. University of Liverpool, 2023.

- Wahab, S. The role of social capital in community-based urban solid waste management: case studies from Ibadan metropolis, Nigeria. 2012.

- Duc, N.H.; Kumar, P.; Long, P.T.; Meraj, G.; Lan, P.P.; Almazroui, M.; Avtar, R. A Systematic Review of Water Governance in Asian Countries: Challenges, Frameworks, and Pathways Toward Sustainable Development Goals. Earth Systems and Environment 2024, 8, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaisen, F.S. The Politicization of Mobility Infrastructures in Vietnam-The Hanoi Metro Project at the Nexus of Urban Development, Fragmented Mobilities, and National Security. Advances in Southeast Asian Studies 2023, 16, 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Anebo, L.N. Assessing the efficacy of African boundary delineation law and policy: The case of Ethio–Eritrea boundary dispute settlement. 2016.

- Mumme, S.P. Border Water: The Politics of US-Mexico Transboundary Water Management, 1945–2015; University of Arizona Press: 2023.

- Swallow, B.; Kallesoe, M.; Iftikhar, U.; van Noordwijk, M.; Bracer, C.; Scherr, S.; Raju, K.; Poats, S.; Duraiappah, A.; Ochieng, B. Compensation and Rewards for Environmental Services in the Developing World.

- Muthama, R.W. A Research Paper on Solid Waste Management in Kenya: an Analysis of Legal and Institutional Frameworks. University of Nairobi, 2021.

- Muriithi, F.L. The Effects of Informal Urban Sprawl on the Provision of Infrastructure in Makongeni Neighbourhood of Thika Municipality, Kiambu County, Kenya. University of Nairobi, 2022.

- Keraita, B.; Drechsel, P.; Amoah, P. Influence of urban wastewater on stream water quality and agriculture in and around Kumasi, Ghana. Environment and Urbanization 2003, 15, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, K.; Castleden, H.; Jamieson, R.; Furgal, C.; Ell, L. Water systems, sanitation, and public health risks in remote communities: Inuit resident perspectives from the Canadian Arctic. Social Science & Medicine 2015, 135, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cele, A. An Assessment of the Effectiveness of Water Quality Monitoring and Drinking Water Quality Compliance by Environmental Health Practitioners at Selected Metropolitan and District Municipalities in South Africa during 2013-2014. 2018.

- Paramita, K.D. Space of Maintenance: A Situated Understanding of Maintenance Practices in Jakarta Contested Neighbourhoods. University of Sheffield, 2019.

- Lalasati, N.A. Sustainable Sanitation for Small Island Cities. 2022.

- Slack, E. Metropolitan governance: Principles and practice. 2019.

- Raju, K.; Ravindra, A.; Manasi, S.; Smitha, K.; Srinivas, R. Urban Environmental Governance in India. P. o. Springer International Publishing 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sarpotdar, A. Spatial Information Support for Inclusive and Integrative Planning in India A case study of Mumbai; The University of Manchester (United Kingdom): 2021.

- Francesch-Huidobro, M.; Dabrowski, M.; Tai, Y.; Chan, F.; Stead, D. Governance challenges of flood-prone delta cities: Integrating flood risk management and climate change in spatial planning. Progress in planning 2017, 114, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanfar, Z.; Sharma, A. Urban drainage system planning and design–challenges with climate change and urbanization: a review. Water Science and Technology 2015, 72, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, J.; Nedovic-Budic, Z. Integrating spatial planning and flood risk management: A new conceptual framework for the spatially integrated policy infrastructure. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2016, 57, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikundi, J. Planning for sustainable utilization and conservation of urban river corridors in Kenya: A Case Study of the Nairobi River. University of Nairobi, 2014.

- Mguni, P. Sustainability Transitions in the Developing World: Exploring the Potential for Integrating Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems in the Sub-Saharan Cities. University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Science, Department of Geosciences and …, 2015.

- Mguni, P.; Herslund, L.; Jensen, M.B. Sustainable urban drainage systems: examining the potential for green infrastructure-based stormwater management for Sub-Saharan cities. Natural Hazards 2016, 82, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Ariza, S.L.; Martínez, J.A.; Muñoz, A.F.; Quijano, J.P.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Camacho, L.A.; Díaz-Granados, M. A multicriteria planning framework to locate and select sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS) in consolidated urban areas. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, K.P.; Chevalier, L.R. Managing urban stormwater for urban sustainability: Barriers and policy solutions for green infrastructure application. Journal of environmental management 2017, 203, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadin, V.; Meng, M. Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning in Europe: The Relevance for Flood Risk Management in the Chinese Pearl River Delta. In Adaptive Urban Transformation: Urban Landscape Dynamics, Regional Design and Territorial Governance in the Pearl River Delta, China, Springer International Publishing Cham: 2023; pp. 63-80.

- Knopman, D.S.; Zmud, J.; Ecola, L.; Mao, Z.; Crane, K. Quality of life indicators and policy strategies to advance sustainability in the Pearl River Delta; Rand Corporation: 2015.

- Vásquez, A.; Giannotti, E.; Galdámez, E.; Velásquez, P.; Devoto, C. Green infrastructure planning to tackle climate change in Latin American cities. Urban Climates in Latin America 2019, 329–354. [Google Scholar]

- Lamond, J.; Stanton-Geddes, Z.; Bloch, R.; Proverbs, D. Cities and Flooding: Lessons in resilience from case studies of integrated urban flood risk management. Proceedings of CIB 2013 World Congress, Special Conference Session on Making Cities More Resilient, Brisbane, Australia.

- Song, J.; Yang, R.; Chang, Z.; Li, W.; Wu, J. Adaptation as an indicator of measuring low-impact-development effectiveness in urban flooding risk mitigation. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 696, 133764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.; Reiter, J.; Weiland, U. Assessment of urban vulnerability towards floods using an indicator-based approach–a case study for Santiago de Chile. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2011, 11, 2107–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, L.; Sinh, B.T. Risk reduction or redistribution? Flood management in the Mekong region. Asian Journal of Environment and Disaster Management 2009, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Moors, E.; Khan, M.S.A.; Warner, J.; Van Scheltinga, C.T. Tipping points in adaptation to urban flooding under climate change and urban growth: The case of the Dhaka megacity. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espina Jr, N.B. Planning for Climate Resilient Barangays in the Philippines: The Case of Barangay Tumana in Marikina City, Metro Manila. Consilience 2018, 130–162. [Google Scholar]

- Yarina, L. Your sea wall won’t save you. Places Journal 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unegbua, H.; Yawasa, D.S.; Dan-asabea, B.; Alabia, A.A. Sustainable Urban Planning and Development: A Systematic Review of Policies and Practices in Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable 2024, 1, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, O. Urban dynamics and vulnerability to disasters in Lagos State, Nigeria (1982–2012). 2014.

- Abbott, M.J.O. Fragile New Orleans, Fortress New Orleans: Navigating Flood Risk Management in a Below-Sea-Level City. Cornell University, 2024.

- Ferdinand, K. GOVERNANCE CONSIDERATIONS IN FLOOD MANAGEMENT: A CASE STUDY OF NEW ORLEANS. Chulalongkorn University, 2015.

- Cea, L.; Costabile, P. Flood risk in urban areas: Modelling, management and adaptation to climate change. A review. Hydrology 2022, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndtsson, R.; Becker, P.; Persson, A.; Aspegren, H.; Haghighatafshar, S.; Jönsson, K.; Larsson, R.; Mobini, S.; Mottaghi, M.; Nilsson, J. Drivers of changing urban flood risk: A framework for action. Journal of environmental management 2019, 240, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative platforms as a governance strategy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Meene, S.; Bettini, Y.; Head, B.W. Transitioning toward sustainable cities—Challenges of collaboration and integration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, M.S.; Wolfe, D.A. Local social knowledge management: Community actors, institutions and multilevel governance in regional foresight exercises. Futures 2004, 36, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S.; Epstein, G.; Anderies, J.M.; Apetrei, C.I.; Baggio, J.; Bodin, Ö.; Chawla, S.; Clements, H.; Cox, M.; Egli, L. Advancing understanding of natural resource governance: a post-Ostrom research agenda. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2020, 44, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Ostrom, V. Choice, rules and collective action: The Ostrom's on the study of institutions and governance; ECPR Press: 2014.

- Vogel, R.K.; Savitch, H.; Xu, J.; Yeh, A.G.; Wu, W.; Sancton, A.; Kantor, P.; Newman, P.; Tsukamoto, T.; Cheung, P.T. Governing global city regions in China and the West. Progress in Planning 2010, 73, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibert, J. Governing urban regions through collaboration: A view from North America; Routledge: 2016.

- Koppell, J.G. World rule: Accountability, legitimacy, and the design of global governance; University of Chicago Press: 2010.

- Koppell, J.G. Global governance organizations: Legitimacy and authority in conflict. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2008, 18, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, M.J.; Page, E.C. Changing government relations in Europe: from localism to intergovernmentalism; Routledge: 2010; Vol. 67.

- Bailey, N. Local strategic partnerships in England: the continuing search for collaborative advantage, leadership and strategy in urban governance. Planning Theory & Practice 2003, 4, 443–457. [Google Scholar]

- Lienert, J.; Schnetzer, F.; Ingold, K. Stakeholder analysis combined with social network analysis provides fine-grained insights into water infrastructure planning processes. Journal of environmental management 2013, 125, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. Decoding the newest “metropolitan regionalism” in the USA: A critical overview. Cities 2002, 19, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengston, D.N.; Fletcher, J.O.; Nelson, K.C. Public policies for managing urban growth and protecting open space: policy instruments and lessons learned in the United States. Landscape and urban planning 2004, 69, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, A.E.; Pincetl, S. Rescaling regions in the state: the new regionalism in California. Political Geography 2006, 25, 482–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, E.S. Regional sustainability planning by metropolitan planning organizations; University of California, Berkeley: 2016.

- Omenya, A.; Lubaale, G. Understanding the tipping point of urban conflict: the case of Nairobi, Kenya. 2012.

- Ståhlberg, T. COLLECTIVE ACTION DILEMMAS IN PUBLIC TRANSPORT REFORMS: A qualitative study of government officials and bus companies willingness and attitudes in Nairobi, Kenya and Kigali, Rwanda. 2024.

- Stensaker, B.; Vabø, A. Re-inventing shared governance: Implications for organisational culture and institutional leadership. Higher Education Quarterly 2013, 67, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCaro, D.A.; Chaffin, B.C.; Schlager, E.; Garmestani, A.S.; Ruhl, J. Legal and institutional foundations of adaptive environmental governance. Ecology and society: A journal of integrative science for resilience and sustainability 2017, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, D.A. Innovating in urban economies: economic transformation in Canadian city-regions; University of Toronto Press: 2014.

- Latham, J. Inter-city Cooperation on Local and Regional Development: A Comparative Study of Liverpool, Manchester and the Randstad; The University of Manchester (United Kingdom): 2007.

- Wei, Q.; Yang, W. Addressing uneven development through state-steered intercity cooperation? Insights from Shenzhen–Ganzhou cooperation plan-making. Regional Studies 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, S.; Bai, X. Positive inertia and proactive influencing towards sustainability: Systems analysis of a frontrunner city. Urban Transformations 2019, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follador, D. Institutional arrangements & collaborative governance in urban planning processes: a comparative case study of Curitiba, Brazil, and Montreal, Canada. Université Laval, 2017.

- Pfeffer, K.; Baud, I.; Denis, E.; Scott, D.; Sydenstricker-Neto, J. Participatory spatial knowledge management tools: empowerment and upscaling or exclusion? Information, Communication & Society 2013, 16, 258–285. [Google Scholar]

- May, P.J.; Winter, S.C. Collaborative service arrangements: Patterns, bases, and perceived consequences. Public Management Review 2007, 9, 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.L.; White, R.M. Collaboration in natural resource governance: Reconciling stakeholder expectations in deer management in Scotland. Journal of environmental management 2012, 112, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, F.; Devine-Wright, P. Partnership or placation? The role of trust and justice in the shared ownership of renewable energy projects. Energy Research & Social Science 2016, 17, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, V.; Rana, A.; Gorgulu, N. Understanding Public Spending Trends for Infrastructure in Developing Countries. Policy Research Working Paper 2022, 9903. [Google Scholar]

- Bluhm, R.; Dreher, A.; Fuchs, A.; Parks, B.; Strange, A.; Tierney, M.J. Connective financing: Chinese infrastructure projects and the diffusion of economic activity in developing countries. 2018.

- Serageldin, M.; Jones, D.; Vigier, F.; Solloso, E.; Bassett, S.; Menon, B.; Valenzuela, L. Municipal financing and urban development; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: 2008.

- Sachs, M. Fiscal dimensions of South Africa's crisis; Southern Centre for Inequality Studies, University of Witwatersrand: 2021.

- Kamutiba, F. Investigating the appropriateness of consolidation loans to mitigate household over-indebtedness in South Africa. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University, 2020.

- Floater, G.; Dowling, D.; Chan, D.; Ulterino, M.; Braunstein, J.; McMinn, T.; Ahmad, E. Global review of finance for sustainable urban infrastructure. Coalition for Urban Transitions: Washington, DC, USA.

- Regassa, N.; Sundaraa, R.D.; Seboka, B.B. Challenges and opportunities in municipal solid waste management: The case of Addis Ababa city, central Ethiopia. Journal of human ecology 2011, 33, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferronato, N.; Torretta, V. Waste mismanagement in developing countries: A review of global issues. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nor Faiza, M.; Hassan, N.A.; Mohammad Farhan, R.; Edre, M.; Rus, R. Solid waste: its implication for health and risk of vector borne diseases. Journal of Wastes and Biomass Management (JWBM) 2019, 1, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Krystosik, A.; Njoroge, G.; Odhiambo, L.; Forsyth, J.E.; Mutuku, F.; LaBeaud, A.D. Solid wastes provide breeding sites, burrows, and food for biological disease vectors, and urban zoonotic reservoirs: a call to action for solutions-based research. Frontiers in public health 2020, 7, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, J. Factors influencing solid-waste management in the developing world. 2015.

- Batista, M.; Caiado, R.G.G.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Lima, G.B.A.; Leal Filho, W.; Yparraguirre, I.T.R. A framework for sustainable and integrated municipal solid waste management: Barriers and critical factors to developing countries. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 312, 127516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.E.; Farahbakhsh, K. Systems approaches to integrated solid waste management in developing countries. Waste management 2013, 33, 988–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, J.P.; Véliz, K.; Vargas, M.; Busco, C. A systems-focused assessment of policies for circular economy in construction demolition waste management in the Aysén region of Chile. Sustainable Futures 2024, 7, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoann, V.; Fujiwara, T.; Seng, B.; Lay, C.; Yim, M. Assessment of public–private partnership in municipal solid waste management in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, C.P.C.; Ho, W.S.; Hashim, H.; Lim, J.S.; Ho, C.S.; Tan, W.S.P.; Lee, C.T. Review on the renewable energy and solid waste management policies towards biogas development in Malaysia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 70, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.C.; Velis, C.A.; Rodic, L. Integrated sustainable waste management in developing countries. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Waste and Resource Management; pp. 52–68.

- Memon, M.A. Integrated solid waste management based on the 3R approach. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management 2010, 12, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurbrügg, C.; Caniato, M.; Vaccari, M. How assessment methods can support solid waste management in developing countries—a critical review. Sustainability 2014, 6, 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukalang, N.; Clarke, B.; Ross, K. Solid waste management solutions for a rapidly urbanizing area in Thailand: Recommendations based on stakeholder input. International journal of environmental research and public health 2018, 15, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinthumule, N.I.; Mkumbuzi, S.H. Participation in community-based solid waste management in Nkulumane suburb, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Resources 2019, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurbrugg, C. Urban solid waste management in low-income countries of Asia how to cope with the garbage crisis. Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa 2002, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lissah, S.Y.; Ayanore, M.A.; Krugu, J.K.; Aberese-Ako, M.; Ruiter, R.A. Managing urban solid waste in Ghana: Perspectives and experiences of municipal waste company managers and supervisors in an urban municipality. PloS one 2021, 16, e0248392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.A.; Maas, G.; Hogland, W. Solid waste management challenges for cities in developing countries. Waste management 2013, 33, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbor, A.A. The ineffectiveness and inadequacies of international instruments in combatting and ending the transboundary movement of hazardous wastes and environmental degradation in Africa. African Journal of Legal Studies 2016, 9, 235–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Lee, S.-H.; Kumar, P.; Kim, K.-H.; Lee, S.S.; Bhattacharya, S.S. Solid waste management: Scope and the challenge of sustainability. Journal of cleaner production 2019, 228, 658–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyarra, E.; Gee, S. Transforming urban waste into sustainable material and energy usage: The case of Greater Manchester (UK). Journal of cleaner production 2013, 50, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, K.A.; LaPointe, M.; Hemsing, K.; Anderson, G.; Anderson, J.; de Jong, J. Inter-city collaboration: Why and how cities work, learn and advocate together. Global Policy 2023, 14, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmelter-Jarosz, A.; Rześny-Cieplińska, J.; Jezierski, A. Assessing resources management for sharing economy in urban logistics. Resources 2020, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollery, B.; Akimov, A. Are shared services a panacea for Australian local government? A critical note on Australian and international empirical evidence. International Review of Public Administration 2007, 12, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.; Tewdwr-Jones, M. Urban and regional planning; Routledge: 2019.

- Cyril Eze, U.; Guan Gan Goh, G.; Yih Goh, C.; Ling Tan, T. Perspectives of SMEs on knowledge sharing. Vine 2013, 43, 210–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Hettiarachchi, H. Collective action in waste management: A comparative study of recycling and recovery initiatives from Brazil, Indonesia, and Nigeria using the institutional analysis and development framework. Recycling 2020, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, G.; Mokhtarian, P.; Dijst, M.; Böcker, L. The dynamics of urban metabolism in the face of digitalization and changing lifestyles: Understanding and influencing our cities. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2018, 132, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, J.B.S.O.; Ribeiro, J.M.P.; Fernandez, F.; Bailey, C.; Barbosa, S.B.; da Silva Neiva, S. The adoption of strategies for sustainable cities: A comparative study between Newcastle and Florianópolis focused on urban mobility. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 113, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niger, M. Deficiencies of existing public transport system and a proposal for integrated hierarchical transport network as an improvement options: a case of Dhaka city. IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering 2013, 5, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, J. Intra-city access to inter-city transport nodes: The implications of high-speed-rail station locations for the urban development of Chinese cities. Urban Studies 2017, 54, 2249–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. Inter-city passenger transport connectivity: measurement and applications. University of British Columbia, 2017.

- Pojani, D.; Stead, D. Sustainable urban transport in the developing world: beyond megacities. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7784–7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wey, W.-M.; Huang, J.-Y. Urban sustainable transportation planning strategies for livable City's quality of life. Habitat International 2018, 82, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letnik, T.; Marksel, M.; Luppino, G.; Bardi, A.; Božičnik, S. Review of policies and measures for sustainable and energy efficient urban transport. Energy 2018, 163, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bofinger, H. Africa's transport infrastructure: Mainstreaming maintenance and management; World Bank Publications: 2011.

- Sohail, M.; Maunder, D.; Cavill, S. Effective regulation for sustainable public transport in developing countries. Transport policy 2006, 13, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, K.; Conway, D.; Bhattarai, K.; Conway, D. Urban growth. Contemporary Environmental Problems in Nepal: Geographic Perspectives.

- Seto, K.C.; Dhakal, S.; Bigio, A.; Blanco, H.; Carlo Delgado, G.; Dewar, D.; Huang, L.; Inaba, A.; Kansal, A.; Lwasa, S. Human settlements, infrastructure, and spatial planning; 2014.

- Manda, M.I. Towards “Smart Governance” through a multidisciplinary approach to E-government integration, interoperability and information sharing: A case of the LMIP project in South Africa. Proceedings of Electronic Government: 16th IFIP WG 8.5 International Conference, EGOV 2017, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2017, Proceedings 16, September 4-7; p. 36.

- Contu, A.; Girei, E. NGOs management and the value of ‘partnerships’ for equality in international development: What’s in a name? Human Relations 2014, 67, 205–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedentop, S.; Fina, S. Urban sprawl beyond growth: the effect of demographic change on infrastructure costs. Flux 2010, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. Designing and implementing cross-sector collaborations: Needed and challenging. Public administration review 2015, 75, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Loosemore, M. Risk allocation in the private provision of public infrastructure. International journal of project management 2007, 25, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, L. The Global Economic Trends and Their Impact on National Economies. International Journal of Accounting, Finance, and Economic Studies 2024, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyay, B.N. Infrastructure development for ASEAN economic integration; ADBI Working Paper: 2009.

- Benner, C.; Pastor, M. Collaboration, conflict, and community building at the regional scale: Implications for advocacy planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research 2015, 35, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshu, P.; Fernando, T.; Keraminiyage, K. Barriers to, and enablers for, stakeholder collaboration in risk-sensitive urban planning: a systematised literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, K.T.; Chapple, K.; Mattiuzzi, E.; Zuk, M. Collaboration and equity in regional sustainability planning in California: Challenges in implementation. California Journal of Politics and Policy 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, J.K.; Selviaridis, K.; Kalra, J.; Van der Valk, W.; Fang, F. Inter-organizational governance: a review, conceptualisation and extension. Production planning & control 2020, 31, 453–469. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, L. Effective Horizontal Coordination: Bridging the Barriers to Effective Supply Chain Management. ResearchSpace@ Auckland, 2010.

| S/N | Issues | Frequency | percentage |

| 1 | Lack of agreement between the cities | 7 | 24 |

| 2 | Disagreements on boundaries | 4 | 13.2 |

| 3 | Lack of a compensation mechanism | 6 | 20 |

| 4 | Lack of a legal framework | 12 | 42.9 |

| Total | 29 | 100 |

| S/N | Issues | Frequency | percentage |

| 1 | Lack of an integrated plan | 17 | 34 |

| 2 | Lack of agreement | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | Lack of Compensation mechanism | 8 | 16 |

| 4 | administrative problems | 24 | 48 |

| Total | 50 | 100 |

| S/N | Issues | Frequency | percentage |

| 1 | increased demand for infrastructure | 25 | 50 |

| 2 | the need for collaborative management | 24 | 48 |

| 3 | necessity of open finance | 29.2 | 58.4 |

| 4 | all these impacts were possible | 41.6 | 83.1 |

| Total |

| S/N | Issues | Frequency | percentage |

| 1 | Hesitancy among stakeholders | 5 | 10 |

| 2 | Lack of support from policymakers | 11 | 21.2 |

| 3 | Lack of leadership | 16 | 31.2 |

| 4 | Lack of attention | 18 | 36.1 |

| Total | 50 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).