Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

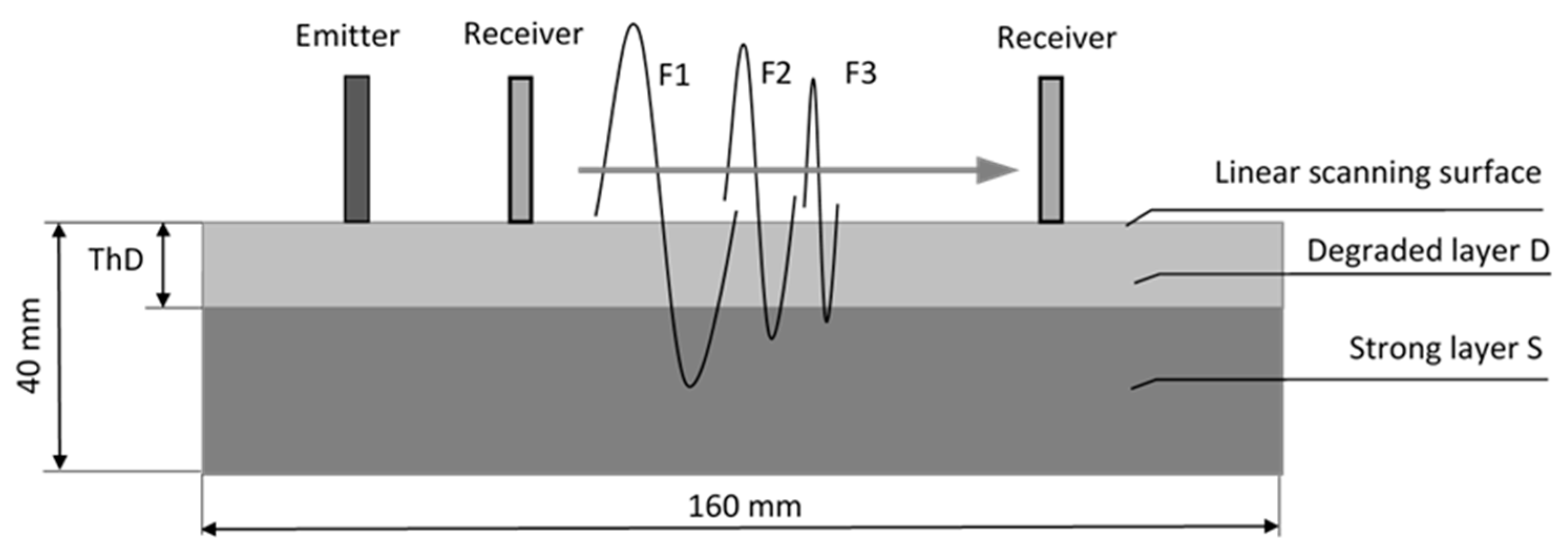

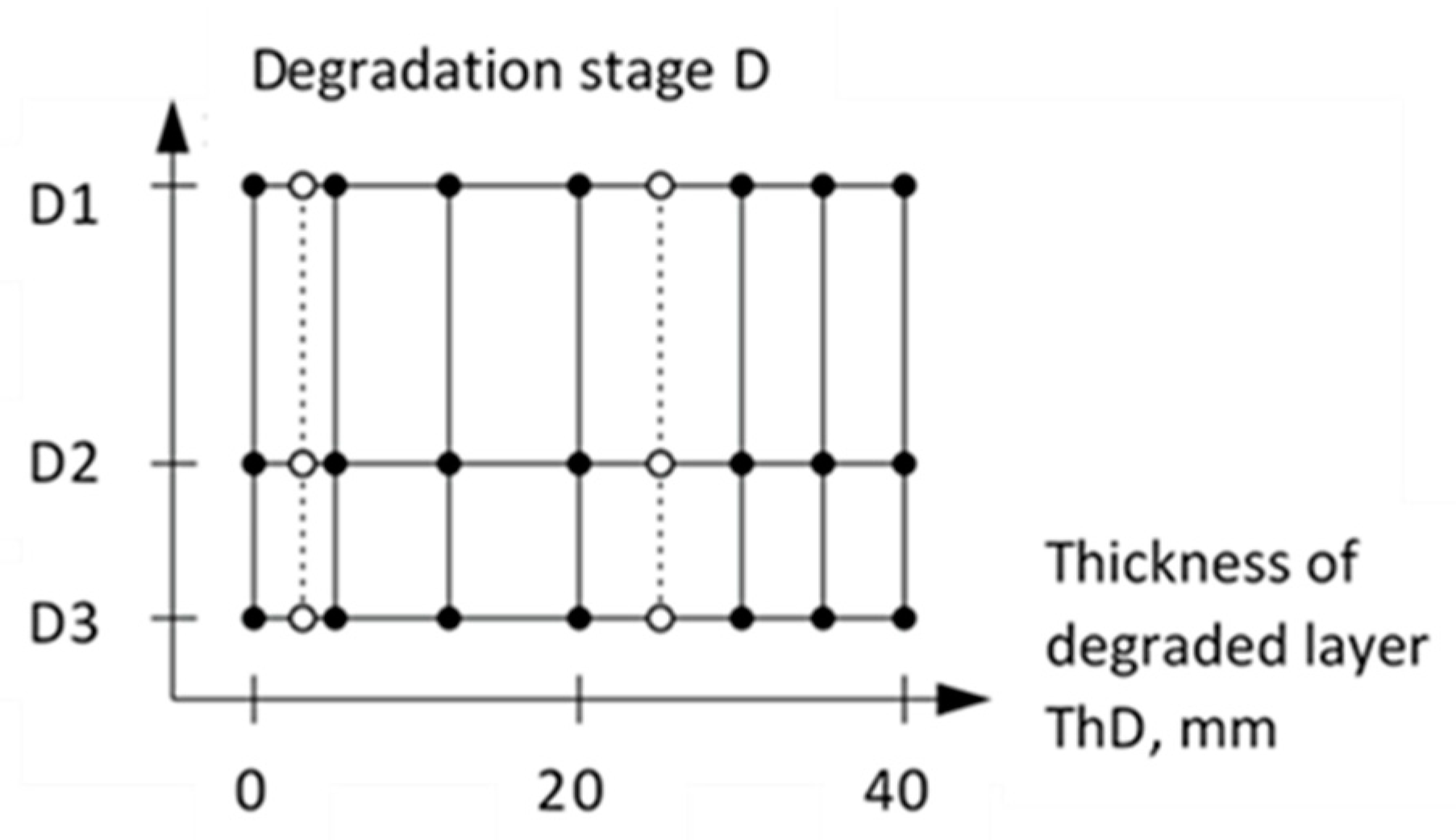

2.1. Concrete Specimens Modeling Degradation of Surface Layer

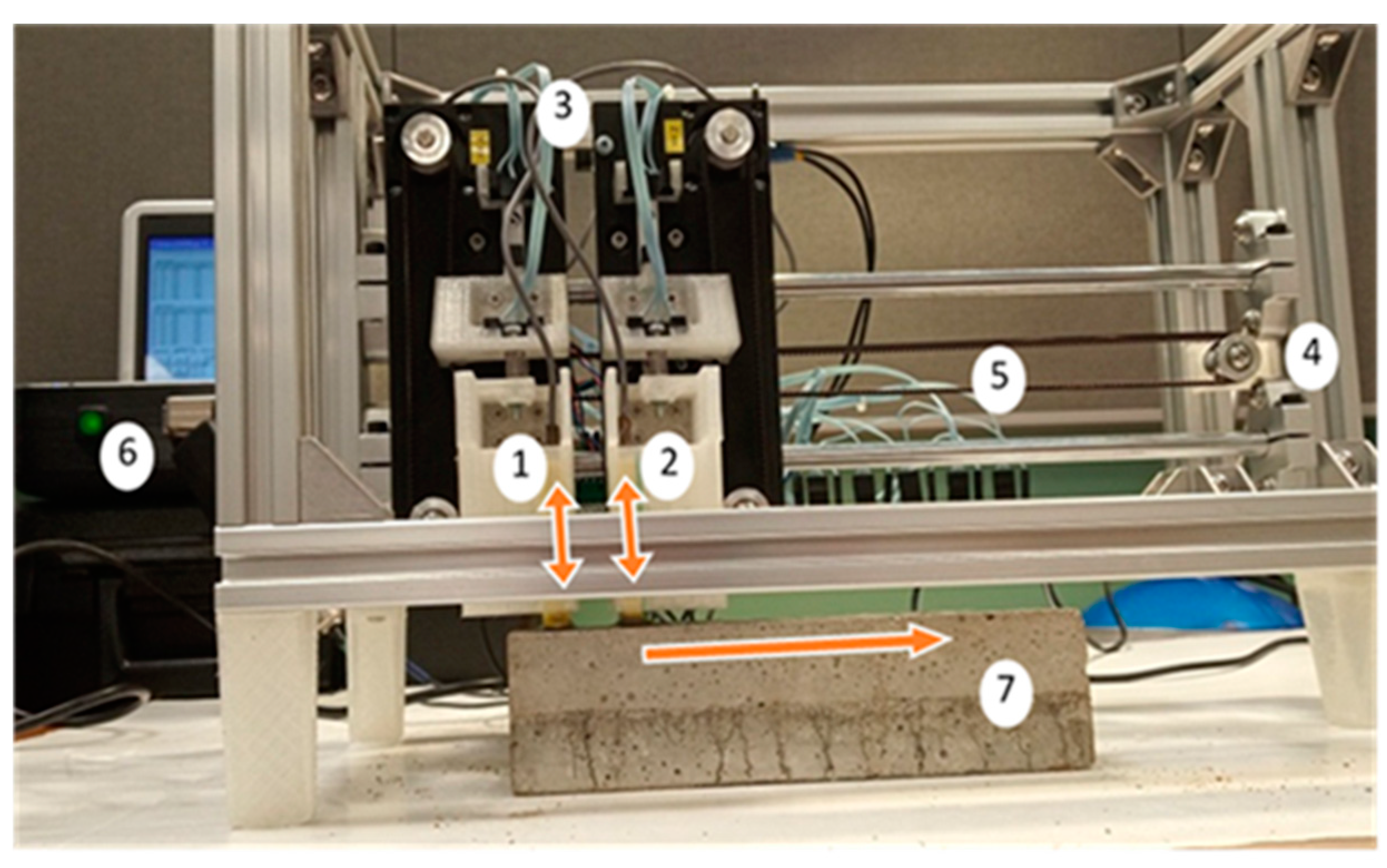

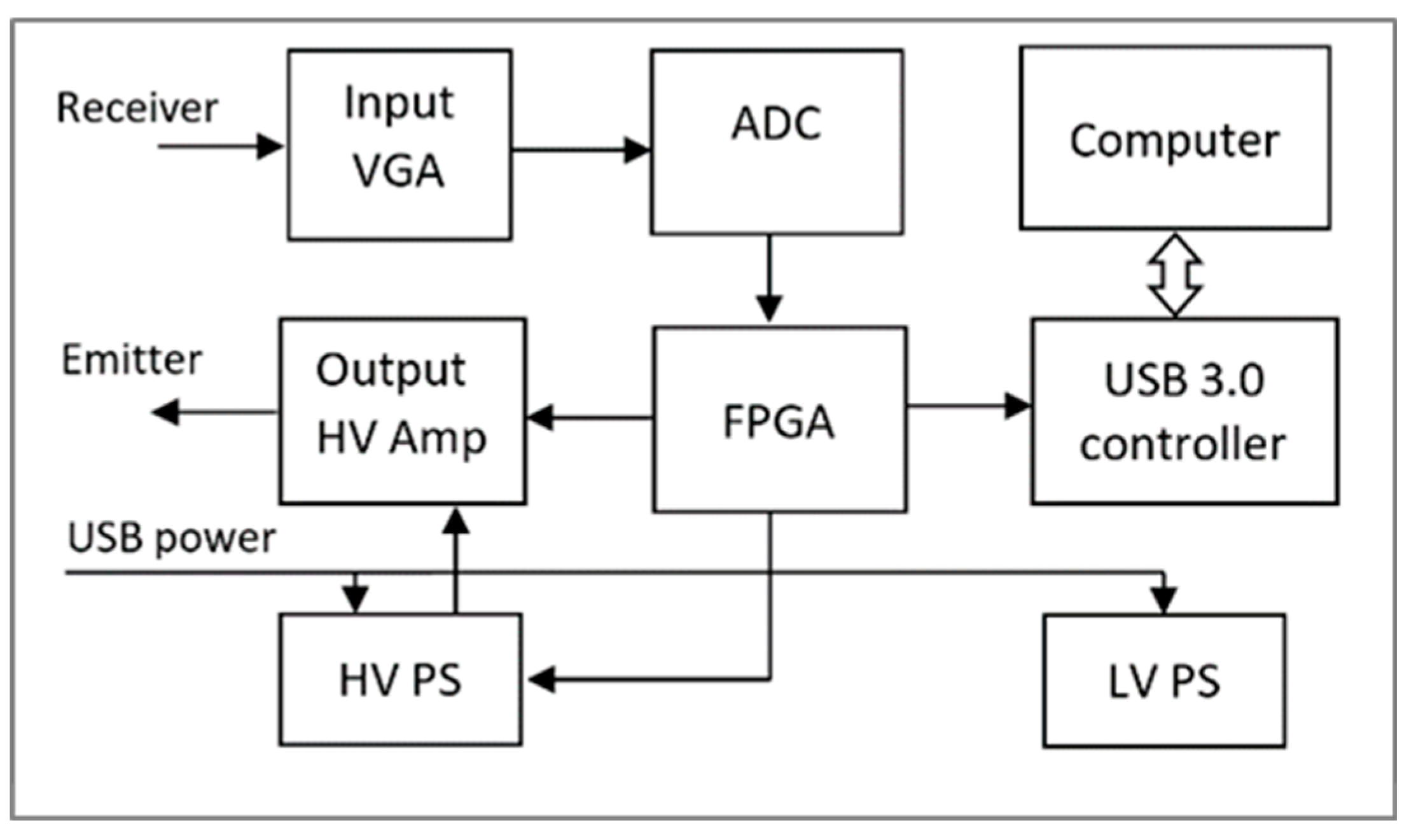

2.2. Ultrasonic Data Acquisition

2.2. Building Neural Networks Based on Signals Obtained during Ultrasonic Measurements on the Surface of Concrete Specimens

3. Results

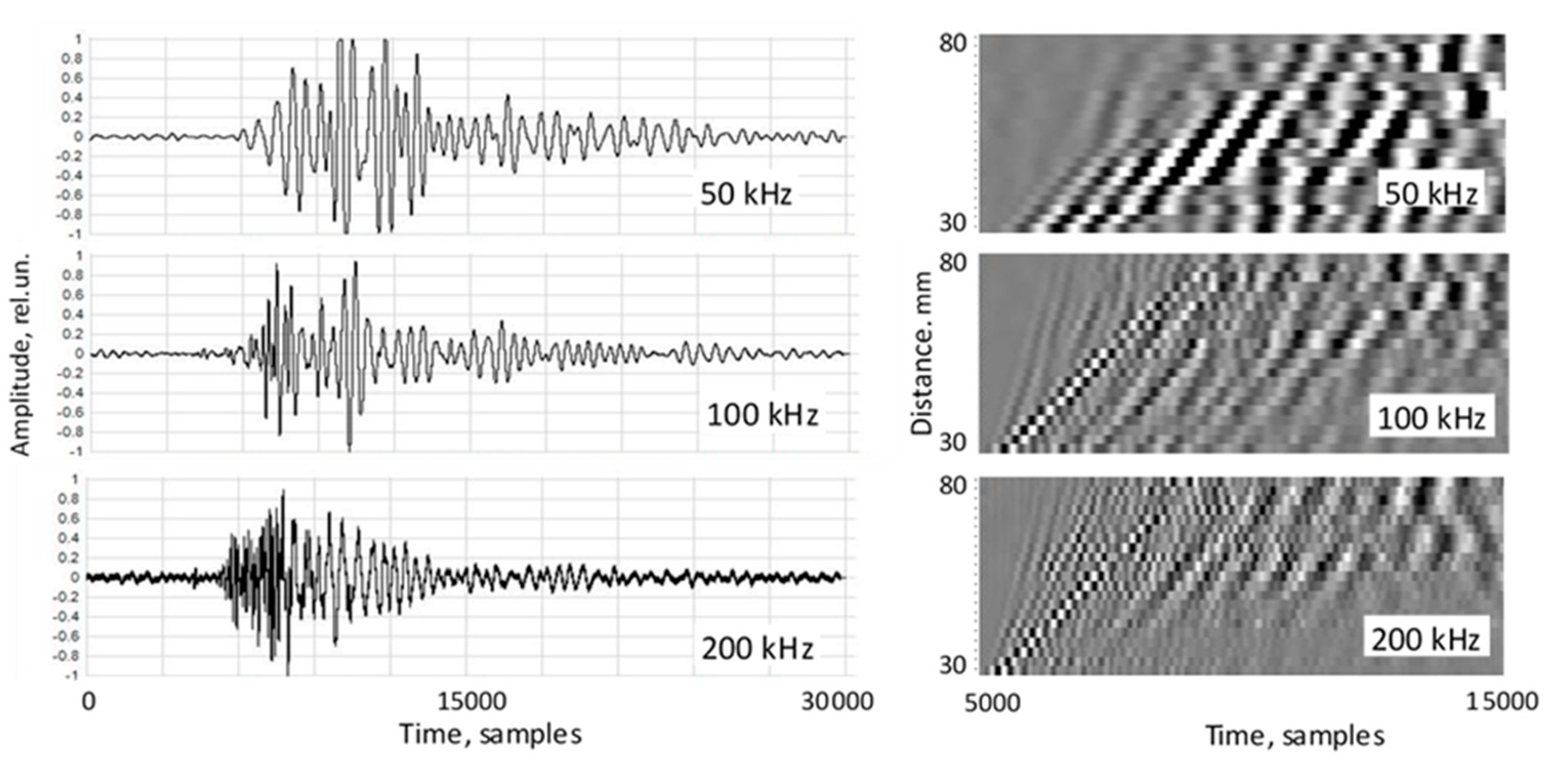

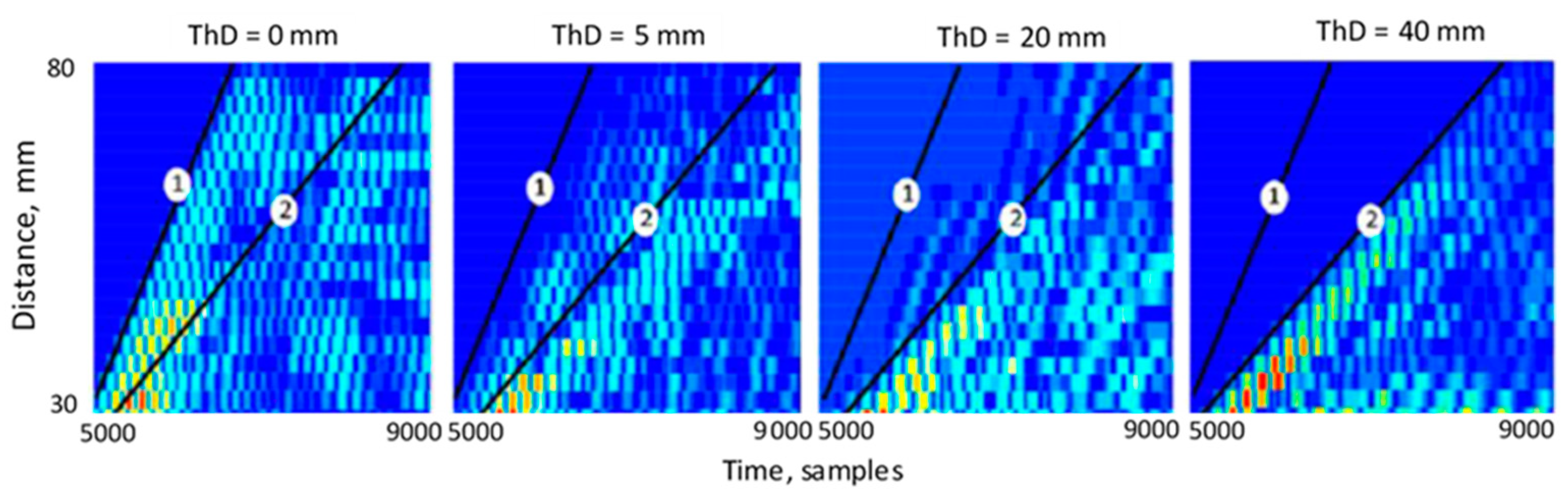

3.1. Spatiotemporal Waveform Profiles

3.2. Application of NN

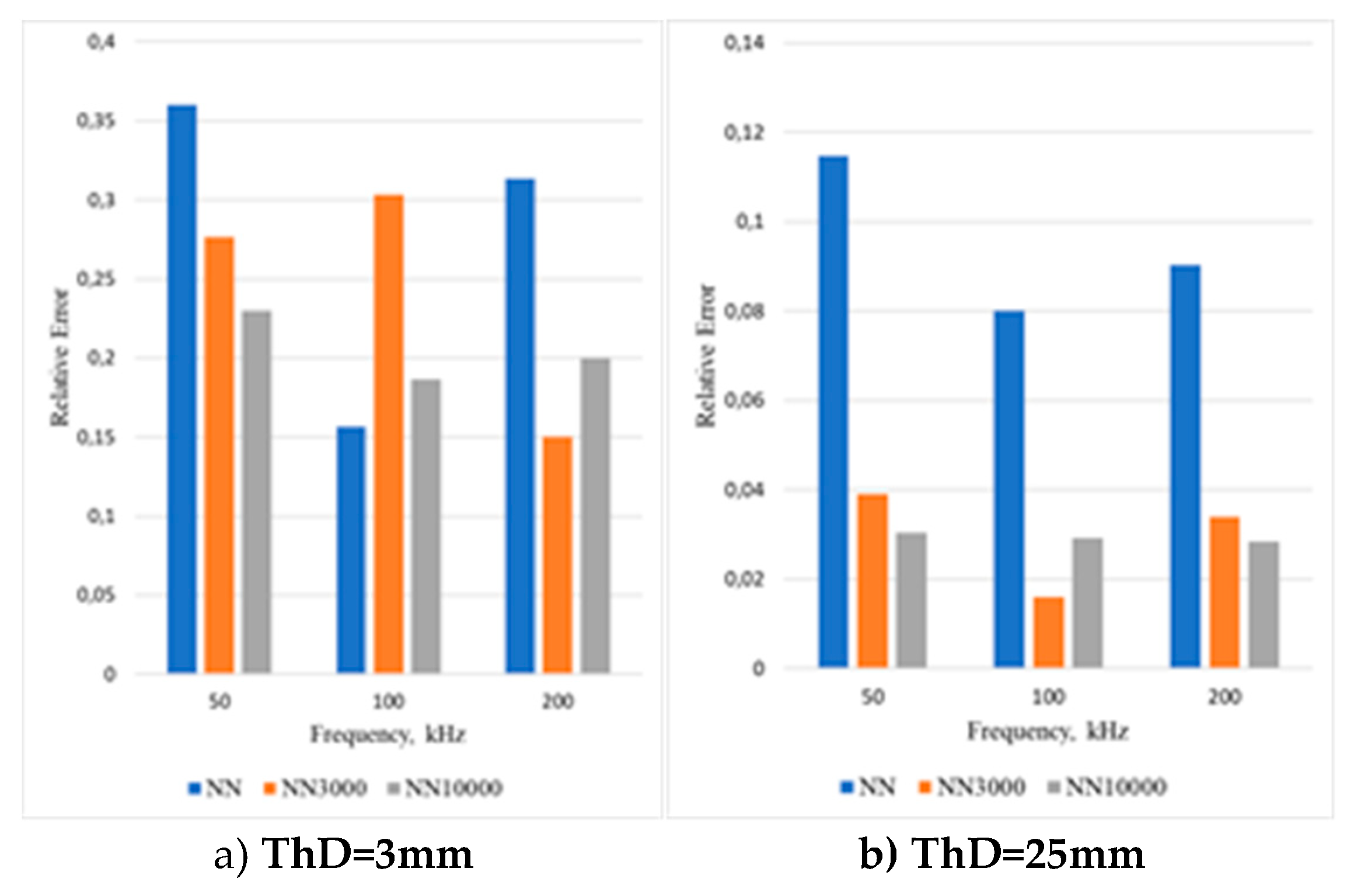

3.2.1. Classification Results for Ultrasonic Signals

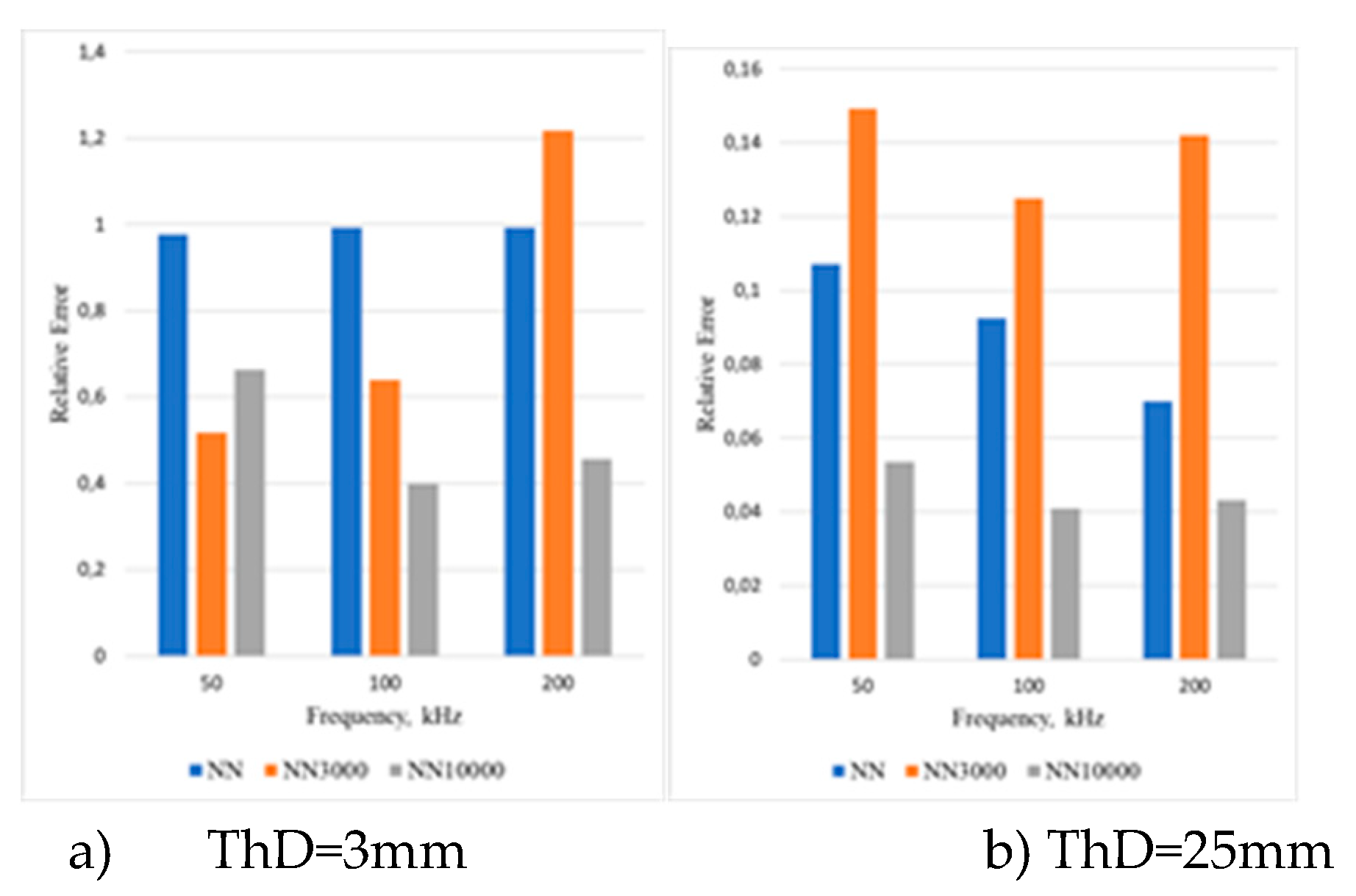

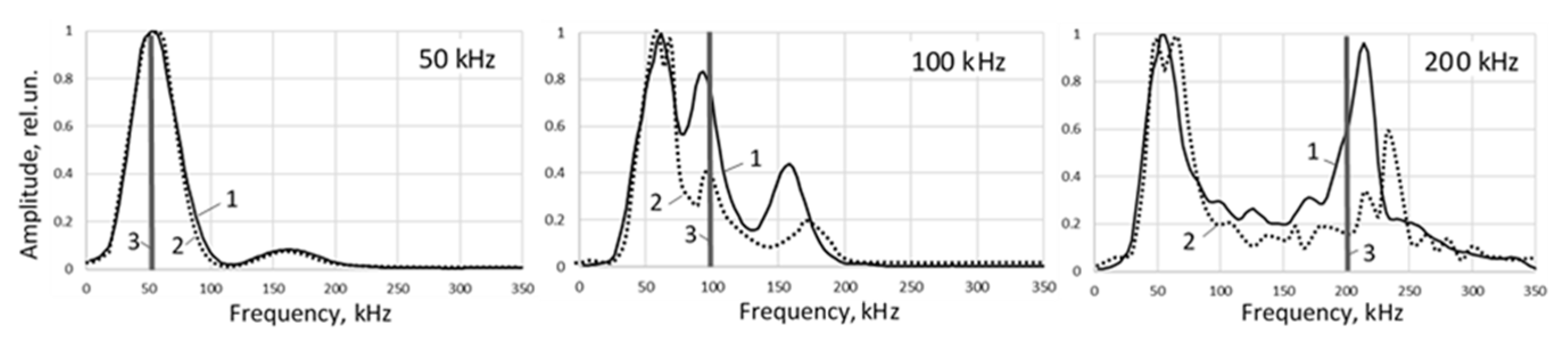

3.2.2. Classification Results for Ultrasonic Signals in Frequency Domain after FFT

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breugel, K. Societal burden and engineering challenges of ageing infrastructure. Procedia Engineering, 2017, 171, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Kajaste and M. Hurme, Cement industry greenhouse gas emissions e management options and abatement cost, J. Clean. Prod., 2016, 112, 4041–4052. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, DW. Concrete deterioration: causes, diagnosis, and minimising risk. International Materials Reviews, 2001, 46(3), 117-144.

- Rosenqvist M, Pham L-W, Terzic A, Fridh K, Hassanzadeh M. Effects of interactions between leaching, frost action and abrasion on the surface deterioration of concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 2017, 149, 849-860.

- Wang X, Yang Q, Peng X, Qin F. A Review of Concrete Carbonation Depth Evaluation Models, Coatings, 2024, 14(4), 386. [CrossRef]

- Bahafid S, Hendriks M, Jacobsen S, Geiker M. Revisiting concrete frost salt scaling: On the role of the frozen salt solution micro-structure. Cement and Concrete Research. 2022, 157, 106803. [CrossRef]

- ElKhatib LW, Khatib J, Assaad JJ, Elkordi A, Ghanem H. Refractory Concrete Properties - A Review. Infrastructures, 2024, 9, 137. [CrossRef]

- Malaiškienė J, Antonovič V, Boris R, Kudžma A, Stonys R. Analysis of the Structure and Durability of Refractory Castables Impregnated with Sodium Silicate Glass. Ceramics, 2023, 6, 2320–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabowicz K. Non-destructive testing of materials in civil engineering. Materials, 2019, 12(19):3237, 1-13.

- Guidebook on non-destructive testing of concrete structures. IAEC (International Atomic Energy Agency). Training Courses Series, 2002, Vol.17.

- Ultrasonic Non-destructive Evaluation. Engineering and Biological Material Characterization. Ed. by T. Kundu. Boca Raton, CRC Press. 2003.

- Komlos K, Popovics S, Niirnbergeroh T, Babd B, Popovics JS. Ultrasonic pulse velocity test of concrete properties as specified in various standards. Cement and Concrete Composites, 1996, 18, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencis U, Udris A, Kara De Maeijer P, Korjakins A. Methodology for determining the correct ultrasonic pulse velocity in concrete. Buildings, 2024, 14, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irrigaray MAP, Pinto R, Padaratz I J.. A new approach to estimate compressive strength of concrete by the UPV metho. Revista IBRACON de Estruturas e Materiais, 2016, 9(3), 395-402.

- Chakraborty J, Wang X, Stolinski M. Analysis of sensitivity of distance between embedded ultrasonic sensors and signal processing on damage detectability in concrete structures. Acoustics, 2022, 4, 89-110. [CrossRef]

- Victorov IA. Rayleigh and Lamb waves. Physical theory and applications. Plenum Press, New York, 1967.

- Li M, Anderson N, Sneed L, Maerz N. Application of ultrasonic surface wave techniques for concrete bridge deck condition assessment. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 2016, 126, pp.s 148-157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho YS. Non-destructive testing of high strength concrete using spectral analysis of surface waves. NDT&E Int, 2003, 36(4), 229-235.

- Tatarinov A, Sisojevs A, Chaplinska A, Shahmenko G, Kurtenoks V. An approach for assessment of concrete deterioration by surface waves. Procedia Structural Integrity, 2022, 37, pp. 453–461. [CrossRef]

- Roberto Miorelli, Anastassios Skarlatos, Caroline Vienne, Christophe Reboud, Pierre Calmon. Deep learning techniques fonon-destructive testing and evaluation. Maokun Li; Marco Salucci. Applications of deep learning in electromagnetics: Teaching Maxwell’s equations to machines, Scitech Publishing, pp.99-143, 2022, 978-1839535895. ff10.1049/SBEW563Eff. ffcea-04316587f.

- A L Bowler, M P Pound, N J Watson. A review of ultrasonic sensing and machine learning methods to monitor industrial processes. Ultrasonics, 2022, 124: 106776.

- Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A. Deep learning. MIT press, 2016.

- Kit Yan Chan, Bilal Abu-Salih, Raneem Qaddoura, Ala’ M. Al-Zoubi, Vasile Palade, Duc-Son Pham, Javier Del Ser, Khan Muhammad. Deep neural networks in the cloud: Review, applications, challenges and research directions”, Neurocom puting, 2023, Vol. 545, , 126327. [CrossRef]

- Taud, Hind and Jean-François Mas. “Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)”, 2018.

- Khotanzad, A., Chung, C. Application of multi-layer perceptron neural networks to vision problems. Neural Comput & Applic, 1988, 7, 249–259. [CrossRef]

- Haykin, S. Neural Networks: a comprehensive foundation. 2nd ed. Prentice Hall, 1998, 842 p.

- H Abdi, L J Williams. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 2010, 2(4), 433-459.

- D Salas-Gonzalez, J M Gorriz, J Ramirez, et al. Feature selection using factor analysis for Alzheimer’s diagnosis using 18F-FDG PET images. Medical Physics, 2010, 37(11), 6084-6095.

- K X Zhang, G L Lv, S F Guo, et al. Evaluation of subsurface defects in metallic structures using laser ultrasonic technique and genetic algorithm-back propagation neural network. NDT & E International, 2020, 116, 102339. [Google Scholar]

- J Liu, G Xu, L Ren, et al. Defect intelligent identification in resistance spot welding ultrasonic detection based on wavelet packet and neural network. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 2017, 90, 2581–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y Wang. Wavelet transform based feature extraction for ultrasonic flaw signal classification. Journal of Computers, 2014, 9(3), 725-732.

- M Mousavi, M S Taskhiri, D Holloway, et al. Feature extraction of woodhole defects using empirical mode decomposition of ultrasonic signals. NDT & E International, 2020, 114, 102282. [Google Scholar]

- Waszczyszyn Z, Ziemianski L. Neural networks in mechanics of structures and materials – new results and prospects of applications. Computers and Structures, 2001, 79(22–25), 2261–2276.

- Liu SW, Huang JH, Sung JC, et al. Detection of cracks using neural networks and computational mechanics. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2002, 191(25–26), 2831–2845. [CrossRef]

- Khandetsky V, Antonyuk I. Signal processing in defect detection using back-propagation neural networks. NDT&E International. 2002, 35(7), 483–488.

- Xu YG, et al. Adaptive multilayer perceptron networks for detection of cracks in anisotropic laminated plates. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 2001, 38, 5625–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang X, Luo H, Tang J. Structural damage detection using neural network with learning rate improvement. Computers and Structures, 2005, 83, 2150–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Gomez LH, Durodola JF, Fellows NA, et al. Locating defects using dynamic strain analysis and artificial neural networks. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 2005, 3-4, 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S. , Jin, S., Zhang, D. et al. Improving Ultrasonic Testing by Using Machine Learning Framework Based on Model Interpretation Strategy. Chin. J. Mech. Eng., 2023, 36, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G L Lv, S F Guo, D Chen, et al. Laser ultrasonics and machine learning for automatic defect detection in metallic components. NDT & E International, 2023, 133, 102752. [Google Scholar]

- G R B Ferreira, M G de Castro Ribeiro, A C Kubrusly, et al. Improved feature extraction of guided wave signals for defect detection in welded thermoplastic composite joints. Measurement, 2022, 198, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solov’ev, A.N. , Cherpakov A.V., Vasil’ev P.V., Parinov I.A., Kirillova E.V. Neural network technology for identifying defect sizes in half-plane based on time and positional scanning. Advanced Engineering Research, 2020, 20-3, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha A, Mahmood A. Review of deep learning algorithms and architectures. IEEE Access, 2019, 7, 53040–53065.

- Hu T, Zhao J, Zheng R, Wang P, Li X, Zhang Q. Ultrasonic based concrete defects identification via wavelet packet transform and GA-BP neural network. PeerJ Computer Science, 2021, Aug 31, e635.

- Shin HK, Ahn YH, Lee SH, Kim HY. Automatic concrete damage recognition using multi-level attention convolutional neural network. Materials, 2020, 13(23), 5549.

- Nyathi, M.A.; Bai, J.; Wilson, I.D. Deep Learning for Concrete Crack Detection and Measurement. Metrology, 2024, 4, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues LFM, Cruz FC, Oliveira MA, Filho EFS, Albuquerque MSC, da Silva IC, Farias CTT. Identification of carburization level in industrial HP pipes using ultrasonic evaluation and machine learning. Ultrasonics, 2018, 94, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Stone JV. The Fourier Transform: A Tutorial Introduction, Sebtel Press, Annotated edition. 2021, Sebtel Press, Annotated edition. 2021.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Applied ultrasonic frequencies | 50, 100, 200 kHz |

| Excitation waveform | 2-period sine tone-burst |

| Output voltage | 100 V p-t-p |

| ADC of received ultrasonic signals | 10-bit, 30 MHz |

| Length and step of scanning | 100 mm, 5 mm |

| Number of ultrasonic signals in a profile set | 21 |

| Ultrasonic frequency, kHz | Velocity, m/s | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | D1 | D2 | D3 | |

| 50 | 2287 | 1916 | 1676 | 1266 |

| 100 | 2300 | 1978 | 1784 | 1278 |

| 200 | 2353 | 2020 | 1780 | 1318 |

| Utrasonic frequency, kHz | Projected values | Predicted values with different networks | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “NN” | “NN3000” | “NN10000” | ||||||

| D, degree | ThD, mm | D, degree | ThD, mm | D, degree | ThD, mm | D, degree | ThD, mm | |

| 50 | D1 | 3.0 | D3** | 3.67 | D1 | 2.31 | D1 | 3.69 |

| 50 | D2 | 3.0 | D2 | 4.08 | D2 | 3.83 | D2 | 3.09 |

| 50 | D3 | 3.0 | D1** | 3.99 | D3 | 2.91 | D3 | 2.44 |

| 100 | D1 | 3.0 | D1 | 3.34 | D1 | 2.36 | D1 | 3.50 |

| 100 | D2 | 3.0 | D2 | 3.44 | D2 | 2.60 | D2 | 3.56 |

| 100 | D3 | 3.0 | D3 | 2.53 | D3 | 3.91 | D3 | 3.06 |

| 200 | D1 | 3.0 | D1 | 2.84 | D1 | 3.40 | D1 | 2.80 |

| 200 | D2 | 3.0 | D2 | 3.94 | D2 | 3.45 | D2 | 2.84 |

| 200 | D3 | 3.0 | D3 | 2.94 | D3 | 3.40 | D3 | 3.60 |

| 50 | D1 | 25.0 | D1 | 23.64 | D1 | 25.98 | D1 | 25.65 |

| 50 | D2 | 25.0 | D2 | 25.32 | D2 | 24.99 | D2 | 24.63 |

| 50 | D3 | 25.0 | D3 | 27.87 | D3 | 25.73 | D3 | 25.76 |

| 100 | D1 | 25.0 | D1 | 26.44 | D1 | 24.60 | D1 | 24.84 |

| 100 | D2 | 25.0 | D2 | 27.00 | D2 | 25.04 | D2 | 24.27 |

| 100 | D3 | 25.0 | D3 | 25.67 | D3 | 25.34 | D3 | 24.50 |

| 200 | D1 | 25.0 | D1 | 27.26 | D1 | 25.85 | D1 | 25.19 |

| 200 | D2 | 25.0 | D2 | 27.09 | D2 | 25.66 | D2 | 25.42 |

| 200 | D3 | 25.0 | D3 | 24.70 | D3 | 24.53 | D3 | 24.29 |

| Utrasonic frequency,kHz | Projected values | Predicted values with different networks | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “NNFT” | “NNFT3000” | “NNFT10000” | |||||||

| D, degree | ThD, mm | D, degree | ThD, mm | D, degree | ThD, mm | D, degree | ThD, mm | ||

| 50 | D1 | 3.0 | D2* | 0.99 | D3** | 3.92 | D1 | 4.99 | |

| 50 | D2 | 3.0 | D2 | 3.67 | D2 | 2.83 | D2 | 4.09 | |

| 50 | D3 | 3.0 | D1** | 5.93 | D3 | 4.55 | D3 | 1.37 | |

| 100 | D1 | 3.0 | D1 | 1.23 | D3** | 3.36 | D1 | 1.80 | |

| 100 | D2 | 3.0 | D3* | 0,024 | D3* | 4.34 | D2 | 1.87 | |

| 100 | D3 | 3.0 | D3 | 1.86 | D3 | 4.92 | D3 | 4.09 | |

| 200 | D1 | 3.0 | D1 | 3.95 | D3** | 6.65 | D1 | 2.19 | |

| 200 | D2 | 3.0 | D2 | 5.09 | D2 | 3.97 | D2 | 2.29 | |

| 200 | D3 | 3.0 | D2* | 5.98 | D3 | 4.87 | D2* | 4.37 | |

| 50 | D1 | 25.0 | D1 | 22.32 | D1 | 28.73 | D1 | 23.66 | |

| 50 | D2 | 25.0 | D3* | 22.89 | D2 | 27.47 | D3* | 25.00 | |

| 50 | D3 | 25.0 | D3 | 26.10 | D3 | 28.35 | D3 | 26.21 | |

| 100 | D1 | 25.0 | D1 | 24.91 | D1 | 26.88 | D1 | 23.98 | |

| 100 | D2 | 25.0 | D2 | 25.66 | D2 | 23.31 | D2 | 24.51 | |

| 100 | D3 | 25.0 | D1** | 22.69 | D3 | 28.12 | D1** | 24.55 | |

| 200 | D1 | 25.0 | D1 | 26.75 | D1 | 28.20 | D1 | 23.92 | |

| 200 | D2 | 25.0 | D2 | 23.42 | D2 | 28.55 | D2 | 24.47 | |

| 200 | D3 | 25.0 | D3 | 26.58 | D3 | 25.34 | D3 | 24.29 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).