Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

3. Results

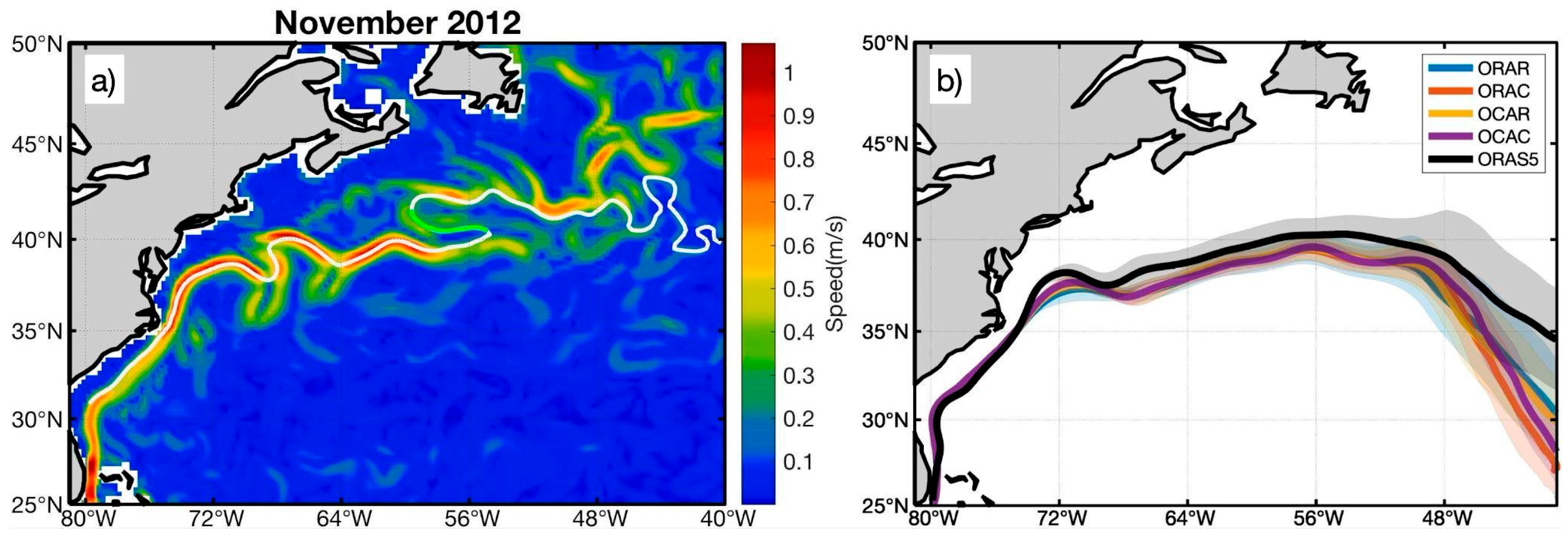

3.1. Trend in Retroflection Patterns

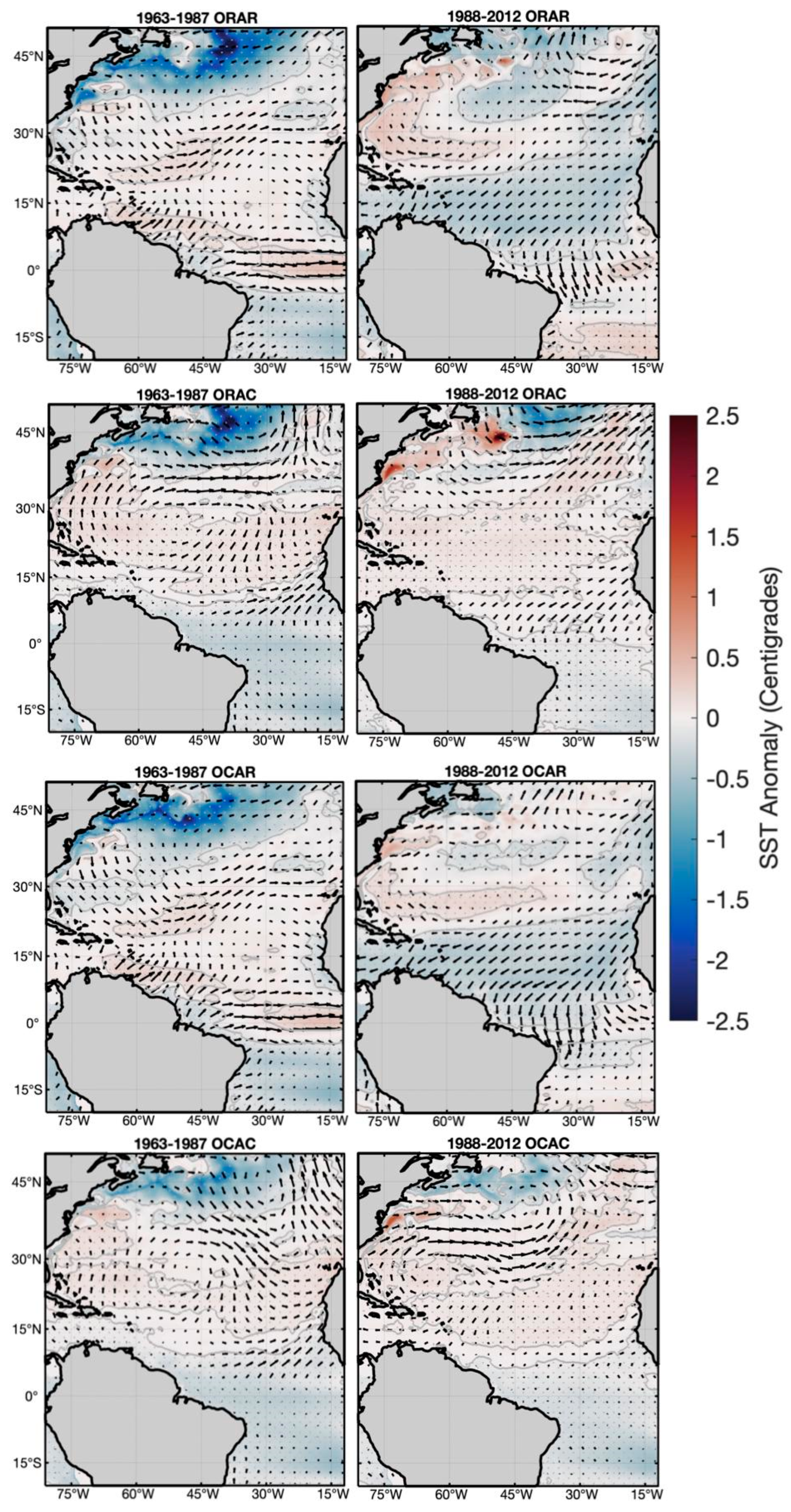

3.2. Potential Causes for the Retroflection Trend

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Acknowledgements

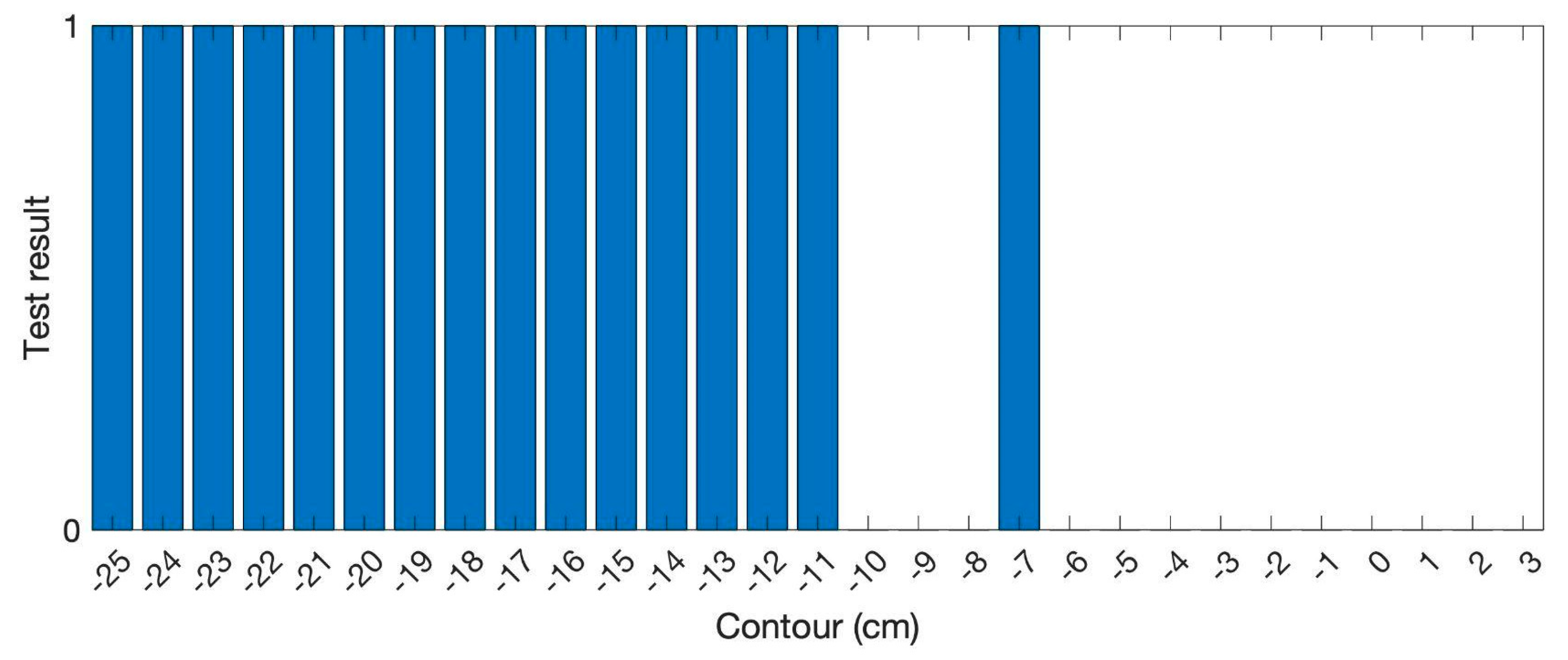

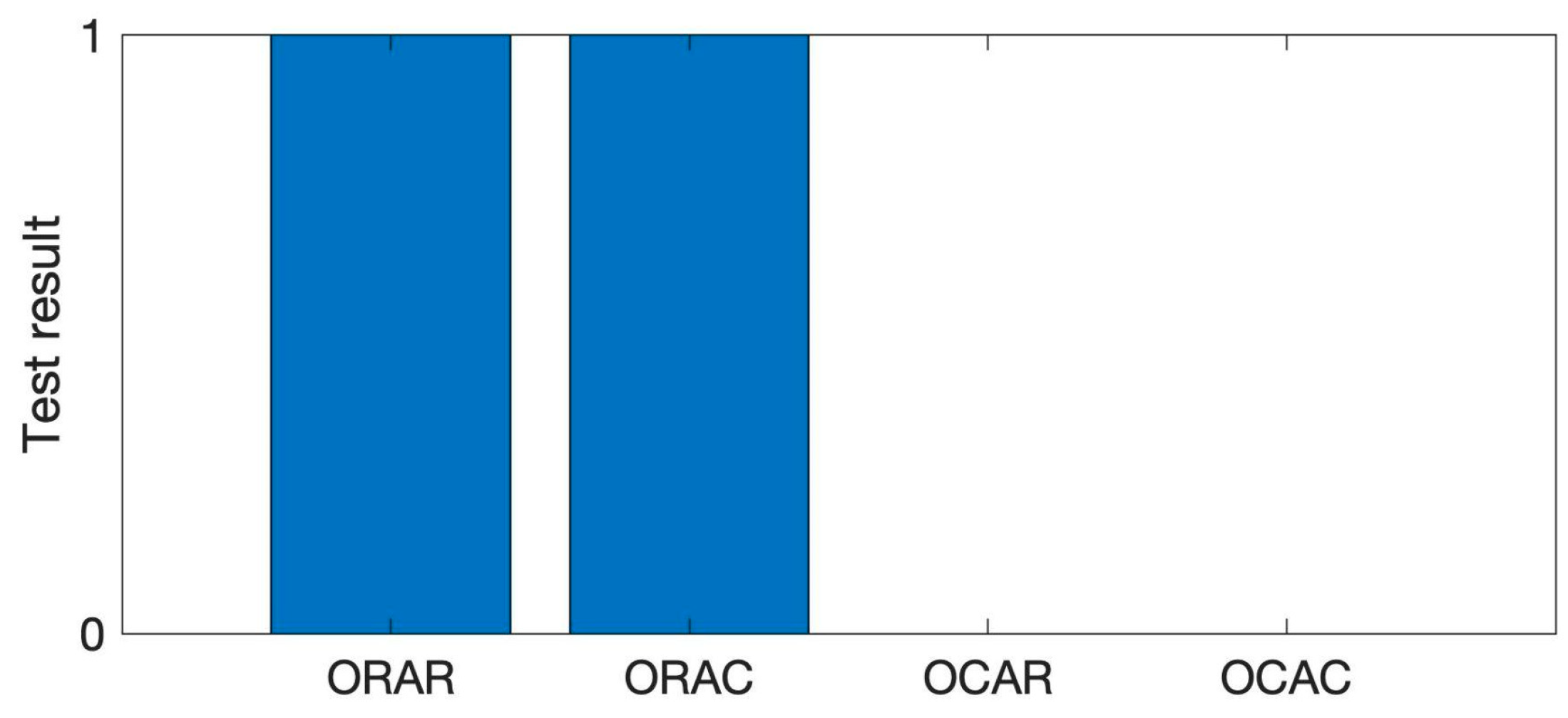

Appendix A. Sensitivity to the SSH Isoline

Appendix B. Composite Mean of Wind and SST Anomalies

References

- Hogg, N.G. On the transport of the Gulf Stream between Cape Hatteras and the Grand Banks. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 1992, 39, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, T.; Yamagami, Y.; Miura, H.; Kido, S.; Tatebe, H.; Watanabe, M. The Gulf Stream and Kuroshio Current are synchronized. Science 374 2021, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, R.E.; Ren, A.S. Warming and lateral shift of the Gulf Stream from in situ observations since 2001. Nature Climate Change 2023, 13, 1348–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J.A.; Joyce, T.M.; Kwon, Y.O.; Link, J.S. Silver hake tracks changes in Northwest Atlantic circulation. Nature communications 2011, 2, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, M. On the recent destabilization of the Gulf Stream path downstream of Cape Hatteras. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43, 9836–9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Román, A.; Gues, F.; Bourdalle-Badie, R.; Pujol, M.I.; Pascual, A.; Drévillon, M. Changes in the Gulf Stream path over the last 3 decades. State of the Planet 2024, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Baringer, M.O.; Goni, G.J. Slow down of the Gulf Stream during 1993–2016. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Z.; Chai, F.; Xue, H.; Oey, L.Y. Remote sensing linear trends of the Gulf Stream from 1993 to 2016. Ocean Dynamics 2020, 70, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, A.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Gawarkiewicz, G.; Silva, E.N.S.; Clark, J. Interannual and seasonal asymmetries in Gulf Stream Ring Formations from 1980 to 2019. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.; Andres, M.; Gawarkiewicz, G. Is the regime shift in Gulf Stream warm core rings detected by satellite altimetry? An inter-comparison of eddy identification and tracking products. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2024, 129, e2023JC020761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Hernández, M.D.; Joyce, T.M. Two modes of Gulf Stream variability revealed in the last two decades of satellite altimeter data. Journal of Physical Oceanography 2014, 44, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, A.; Cornillon, P.; Watts, D.R. A test of the Parsons–Veronis hypothesis on the separation of the Gulf Stream. Journal of Physical Oceanography 1992, 22, 1286–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Cornillon, P. Temporal variation of meandering intensity and domain-wide lateral oscillations of the Gulf Stream. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1995, 100, 13603–13613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.H.; Jordan, M.B.; Stephens, J.A. Gulf Stream shifts following ENSO events. Nature 1998, 393, 638–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, T.M.; Zhang, R. On the path of the Gulf Stream and the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Journal of Climate 2010, 23, 3146–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.H.; Stephens, J.A. The North Atlantic oscillation and the latitude of the Gulf Stream. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 1998, 50, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, A.; Chaudhuri, A.H.; Taylor, A.H. On the nature of temporal variability of the Gulf Stream path from 75° to 55°W. Earth Interactions 2016, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.O.; Joyce, T.M. Northern Hemisphere winter atmospheric transient eddy heat fluxes and the Gulf Stream and Kuroshio–Oyashio Extension variability. Journal of Climate 2013, 26, 9839–9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, T.M.; Kwon, Y.O.; Seo, H.; Ummenhofer, C.C. Meridional Gulf Stream shifts can influence wintertime variability in the North Atlantic storm track and Greenland blocking. Geophysical Research Letters 2019, 46, 1702–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampe, T.; Nakamura, H.; Goto, A.; Ohfuchi, W. Significance of a midlatitude SST frontal zone in the formation of a storm track and an eddy-driven westerly jet. Journal of Climate 2010, 23, 1793–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, D.; Nakamura, H. On the significance of the sensible heat supply from the ocean in the maintenance of the mean baroclinicity along storm tracks. Journal of Climate 2011, 24, 3377–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Sampe, T.; Tanimoto, Y.; Shimpo, A. Observed associations among storm tracks, jet streams and midlatitude oceanic fronts. Earth’s Climate: The Ocean–Atmosphere Interaction, Geophys. Monogr 2004, 147, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, R.; Czaja, A.; Minobe, S.; Kuwano-Yoshida, A. The atmospheric frontal response to SST perturbations in the Gulf Stream region. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, R.; Czaja, A.; Kwon, Y.O. The impact of SST resolution change in the ERA-Interim reanalysis on wintertime Gulf Stream frontal air-sea interaction. Geophysical Research Letters 2017, 44, 3246–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soster, F.; Parfitt, R. On objective identification of atmospheric fronts and frontal precipitation in reanalysis datasets. Journal of Climate 2022, 35, 4513–4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Mogensen, K.; Tietsche, S. OCEAN5: the ECMWF Ocean Reanalysis System and its Real-Time analysis component. ECMWF Technical Memorandum 2018, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Mogensen, K. The new eddy-permitting ORAP5 ocean reanalysis: description, evaluation and uncertainties in climate signals. Climate Dynamics 2017, 49, 791–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Adcroft, A.; Hill, C.; Perelman, L.; Heisey, C. A finite volume, incompressible Navier-Stokes model for studies of the ocean on parallel computers. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1997, 102, 5753–5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, W.K.; Parfitt, R.; Wienders, N. Routine reversal of the AMOC in an ocean model ensemble. Geophysical Research Letters 2022, 49, e2022GL100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamet, Q.; Dewar, W.K.; Wienders, N.; Deremble, B. Spatiotemporal patterns of chaos in the Atlantic overturning circulation. Geophysical Research Letters 2019, 46, 7509–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamet, Q.; Dewar, W.K.; Wienders, N.; Deremble, B.; Close, S.; Penduff, T. Locally and remotely forced subtropical AMOC variability: A matter of time scales. Journal of Climate 2020, 33, 5155–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, T.; Jamet, Q.; Dewar, W.K.; Le Sommer, J.; Penduff, T.; Balwada, D. Diagnosing the thickness-weighted averaged eddy-mean flow interaction from an eddying North Atlantic ensemble: The Eliassen-Palm flux. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 2022, 14, e2021MS002866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, T.; Jamet, Q.; Dewar, W.K.; Deremble, B.; Poje, A.C.; Sun, L. Imprint of chaos on the ocean energy cycle from an eddying North Atlantic ensemble. Journal of Physical Oceanography 2024, 54, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, T.; Jamet, Q.; Poje, A.C.; Wienders, N.; Dewar, W.K. Wavelet-based wavenumber spectral estimate of eddy kinetic energy: Application to the North Atlantic. Ocean Modelling 2024, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillibridge, I.I.I.; JL; Mariano, A. J. A statistical analysis of Gulf Stream variability from 18+ years of altimetry data. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2013, 85, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossby, T.; Flagg, C.N.; Donohue, K.; Sanchez-Franks, A.; Lillibridge, J. On the long-term stability of Gulf Stream transport based on 20 years of direct measurements. Geophysical Research Letters 2014, 41, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheremet, V.A. Inertial gyre driven by a zonal jet emerging from the western boundary. Journal of Physical Oceanography 2002, 32, 2361–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, L.V. On the north Atlantic circulation. John Hopkins Oceanographic Studies 1976, 6, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz Jr, W.J. On the eddy field in the Agulhas Retroflection, with some global considerations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1996, 101, 16259–16271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.V. Gulf stream meanders between Cape Hatteras and the Grand Banks. Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts 1970, 17, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, V.W.; Zhou, Y. (2014). Kolmogorov–smirnov test: Overview. Wiley statsref: Statistics reference online. [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, S.; Czaja, A.; Parfitt, R.; Dewar, W.K. (2024). Tropospheric response to Gulf Stream intrinsic variability: a model ensemble approach. Geophysical Research Letters. [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; O’Neill, L.W.; Bourassa, M.A.; Czaja, A.; Drushka, K.; Edson, J.B.; Wang, Q. Ocean mesoscale and frontal-scale ocean–atmosphere interactions and influence on large-scale climate: A review. Journal of climate 2023, 36, 1981–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megann, A.; Blaker, A.; Josey, S.; New, A.; Sinha, B. Mechanisms for late 20th and early 21st century decadal AMOC variability. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2021, 126, e2021JC017865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldama-Campino, A.; Döös, K. Mediterranean overflow water in the North Atlantic and its multidecadal variability. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 2020, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).