1. Introduction

Hydrogen-induced damage is a phenomenon in which the mechanical properties of metals and alloys deteriorate significantly due to the presence and interaction of hydrogen atoms, one of the smallest atomic radii in the periodic table with 0.53 Å, within the material's structure [

1]. It can lead to unexpected and catastrophic component failures, especially in environments where hydrogen is present. When metals are exposed to hydrogen, such as during manufacturing, processing, or in service environments, hydrogen atoms can diffuse into the metal lattice [

2]. Once inside the lattice, hydrogen can accumulate at high concentrations in localized areas, weakening the metal's bonds and reducing its ductility and toughness. This makes the metal more susceptible to cracking and failure, even under relatively low-stress levels [

3].

Hydrogen-induced damage is a phenomenon where the mechanical properties of metals and alloys deteriorate significantly due to the presence and interaction of hydrogen atoms within the material's structure. Hydrogen, with one of the smallest atomic radii in the periodic table, can diffuse into metal lattices, leading to unexpected and catastrophic component failures. When metals are exposed to hydrogen during manufacturing, processing, or service environments, hydrogen atoms can accumulate in localized areas, weakening the metal’s bonds and reducing its ductility and toughness. This increases susceptibility to cracking and failure, even under relatively low-stress levels.

There are different types of hydrogen-induced damage to metallic materials in the literature, such as Hydrogen embrittlement, Hydrogen attack, Hydrogen-induced blistering, Cracking from precipitation of internal hydrogen, and Cracking from hydride formation [

4]. Understanding the mechanisms behind hydrogen-induced damage, such as hydrogen-induced blistering, is relatively straightforward as it involves a phase transformation process. For instance, blistering occurs when molecular hydrogen accumulates at internal defects, leading to pressure buildup and micro-crack formation [

5]. This damage is feasible by preventing atomic hydrogen from entering the material surface. However, comprehending hydrogen embrittlement is more sophisticated and challenging, making it difficult to avoid the catastrophic damage it can cause. Hydrogen embrittlement (HE) is a phenomenon wherein the mechanical properties of metals and alloys undergo significant degradation due to the introduction of atomic hydrogen into their crystalline structure. Atomic hydrogen, composed of a single proton and electron, is small, enabling it to readily dissolve and diffuse within the lattice structure of metals and alloys.

Several types of hydrogen-induced damage have been identified in the literature, such as hydrogen embrittlement (HE), hydrogen attack, hydrogen-induced blistering, cracking from internal hydrogen precipitation, and breaking from hydride formation. Hydrogen embrittlement is particularly challenging to prevent due to its complex mechanisms. Despite being well-known today, hydrogen embrittlement has a long history marked by decades of research and discovery. Since its discovery in 1875 by Johnson, who first observed the effects of hydrogen on iron, extensive studies have been conducted to understand and mitigate this phenomenon.

Hydrogen embrittlement, despite being a well-known phenomenon today, has a rich historical progression marked by decades of research and discovery. Since its discovery in 1875, hydrogen embrittlement has posed a continuous challenge in engineering materials across various industries, from naval vessels to aerospace technologies and nuclear facilities. The earliest observations of hydrogen-induced failures in metals can be traced back to the late 19th century. However, it was not until the early 20th century that significant progress was made in understanding the underlying mechanisms. In 1875, Johnson first noted the detrimental effects of hydrogen on the mechanical properties of metals while he investigated the effect of different acids on iron [

6]. Then, this phenomenon was confirmed by Reynolds [

7]. Subsequent studies by researchers like Longmuir, Andrew, Fuller, Coulson, Parr, Watts and Fleckenstein, Langdon and Grossman, and Edwards, etc., in the early 20th century provided further insights into hydrogen embrittlement, particularly concerning steel [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. In 1926, Pfeil et al. [

16] conducted tensile tests on specimens immersed in acid, showing phenomenal changes in strength and fracture characteristics. The effect of hydrogen on crystal boundaries varies with temperature. He also found that time and different acid strengths did not affect the results.

Significant progress was made in the mid-20th century with the development of advanced analytical techniques such as electron microscopy and fracture mechanics, allowing researchers to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of hydrogen embrittlement at the microstructural level that was mainly based on the mechanical test comparison of H-charged and non-charged specimens [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In 1967, Elsea et al. [

27] reviewed different cleaning, pickling, and electroplating processes, including treatments for hydrogen embrittlement relief to decrease the effect of hydrogen in high-strength steels. Understanding hydrogen embrittlement involves unraveling the complex mechanisms by which hydrogen interacts with metal surfaces, penetrates the lattice, interacts with microstructural properties, and influences deformation mechanisms and fracture modes. Beachem [

28] focused on elucidating how hydrogen alters the properties of dislocations, affects deformation mechanisms, and ultimately leads to various fracture modes. The study highlights the role of hydrogen in facilitating dislocation movement or formation and its dependence on the material's microstructure in determining fracture modes.

Gray et al. [

29] conducted a study by using ion and laser microprobes that revealed high concentrations of corrosion-produced hydrogen beneath fracture surfaces of titanium alloy specimens, supporting the theory that this hydrogen is responsible for stress corrosion embrittlement and cracking, with the potential for further quantitative mapping of hydrogen distribution at notch roots and crack tips. Nelson et al. [

30] contributed to understanding hydrogen's role in stress corrosion processes. He compared stress corrosion cracking of titanium in an aqueous chloride environment with embrittlement by gaseous hydrogen, showing similarities at low pressures but differences at higher pressures, with tests supporting hydrogen as the embrittling species in the aqueous environment. He found that the role of hydrogen in stress-corrosion cracking is complex, with different microstructures affecting embrittlement severity and failure modes. Jewett et al. [

31] researched how hydrogen environment embrittlement affects different metals and alloys under stress in a hydrogen atmosphere. Still, some materials, like aluminum alloys and stainless steel, are less susceptible to this phenomenon. So, the main factor controlling the transfer rate in hydrogen environments is likely the hydrogen adsorption onto the metal surface. Then Gray et al. [

32] tried to lay the groundwork for subsequent discussions of mechanisms and the details of test specimens and test techniques for hydrogen environment embrittlement research—both the effects of the experimental variables and test techniques used by previous investigators. Increasing the importance of hydrogen caused damage to the metals and alloys to determine hydrogen content in metals with non-destructive testing methods. Alex et al. [

33] patented a nondestructive system, and a method was developed to determine the presence and extent of hydrogen embrittlement in metals, alloys, and crystalline structures. Positron annihilation characteristics provide unique energy distribution curves for each material tested at different stages of embrittlement. Gamma radiation from these events is detected and summarized to show variations in electron activity caused by embrittlement. Both Oriani et al. [

34] and Hirth et al. [

35] provided comprehensive reviews of hydrogen embrittlement in steels, covering aspects such as hydrogen solubility, equilibrium, transport, ingress, and desorption from steel. They also discussed the impact of hydrogen on mechanical behavior, including tensile deformation and fracture. In the abovementioned study, Hirth additionally examined the fundamental interactions between hydrogen and dislocations at different temperatures. While, Oriani suggested several areas for future research, some of which remain unexplored to date, as well as the study of cohesive strength. Hirth evaluated various models explaining fracture phenomena in the presence of hydrogen. Both studies were highly cited in the academic papers.

In addition to the abovementioned studies, Lynch et al. [

36] summarized metallographic and fractographic studies of crack growth across various materials and environments, revealing similarities between hydrogen-assisted cracking, stress-corrosion cracking, and adsorption-induced liquid-metal embrittlement. He suggested that these forms of cracking result from hydrogen adsorption at crack tips, encouraging localized plastic flow and micro void coalescence, supported by high-voltage transmission-electron microscopy studies and theoretical work. In another study, Lynch et al. [

37] also discussed mechanisms of environmentally assisted cracking, emphasizing the importance of microstructural characteristics, fracture surfaces, slip planes, and strains associated with crack growth in understanding these processes. Metallographic and fractographic techniques for studying cracking are outlined, highlighting the advantages of analyzing single crystals. Lynch’s observations supported mechanisms such as repeated formation and fracture of brittle hydrides for specific materials like niobium and a localized slip process induced by adsorption in aluminum alloys and high-strength steels, while other proposed mechanisms received less support.

In the decade spanning from 1990 to 2000, research on hydrogen embrittlement (HE) experienced notable advancements and challenges due to the use of the Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). This period is called the Micro-Meso Approach. Researchers have witnessed a growing understanding of the mechanisms underlying HE, particularly in high-strength steels and aerospace alloys, driven by a combination of experimental investigations and theoretical modeling. Researchers delved into the role of hydrogen in altering the mechanical properties of metals at atomic and microstructural levels, shedding light on factors such as hydrogen diffusion kinetics, trapping sites, and the synergy between hydrogen and applied stress. Several studies, such as Lukito et al. [

38] found that microstructural heterogeneities in medium-strength steels (BHS-1, 4037, 1022 QT, and 1022 CN) act as trapping sites for hydrogen, with susceptibility to hydrogen embrittlement influenced by factors such as the amount of trapped hydrogen, entry kinetics, exposure time, and hydrogen transport mode, particularly in various steels utilized as fasteners in the automotive. Ferreira et al. [

39,

40] tried to explain how hydrogen modifies the mechanical characteristics of materials by diminishing elongation to failure and inducing a shift toward brittle fracture modes. Research outcomes exhibit disparities concerning hydrogen's impact on flow stress. Dislocations in aluminum and stainless steel exhibit distinct behaviors in the presence of hydrogen, with solute pinning observed in stainless steel. In-situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) straining experiments reveal that hydrogen reduces elastic interactions among dislocations. Several hypotheses posited to explain the increase of dislocation mobility induced by hydrogen.

In the latter half of the 20th century, researchers mostly identified two main mechanisms, hydrogen-enhanced decohesion (HEDE) [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47] and hydrogen-enhanced localized plasticity (HELP) [

28,

47,

48,

49], responsible for hydrogen embrittlement in metals that do not form hydrides. HELP, which increases dislocation mobility across a wide range of hydrogen concentrations, operates to varying extents depending on hydrogen levels. Meanwhile, HEDE requires reaching a critical hydrogen concentration to induce a sudden shift from ductile to brittle behavior by weakening atomic lattice cohesion. Additionally, other mechanisms like adsorption-induced dislocation emission (AIDE) have been proposed later, demonstrating hydrogen's complex role in altering material behavior [

50]. It suggests that hydrogen atoms adsorbed on metal surfaces facilitate the emission of dislocations, which are defects in the crystal lattice responsible for plastic deformation [

51]. This mechanism implies that the presence of hydrogen at the metal surface promotes dislocation movement, leading to localized plasticity and potentially contributing to embrittlement. These findings broaden our understanding of hydrogen embrittlement's complexities beyond traditional models.

From 2000 to the present, hydrogen embrittlement (HE) research has witnessed significant advancements driven by interdisciplinary collaborations and technological innovations. This period saw a continued focus on understanding the fundamental mechanisms of HE, including hydrogen diffusion, trapping, and its interaction with material microstructures at atomic scales. Experimental techniques such as in situ microscopy, electron microscopy, and advanced spectroscopic methods have enabled researchers to observe and analyze hydrogen behavior in remarkable detail. For instance, electrochemical nanoindentation allows simultaneous electrochemical hydrogen charging and nanomechanical testing in a small surface volume, enabling rapid, uniform hydrogen concentration [

52]. This technique has been applied to understand hydrogen embrittlement and its interaction with dislocations in various metals like aluminum, copper, nickel, and iron alloys [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61].

Computational modeling and simulations have also played a crucial role in predicting HE susceptibility and guiding material design such as atomistic modeling and simulation [

62,

63]. Multiscale Modelling [

64,

65,

66,

67], Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation and Monte Carlo Simulation [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77], Density Functional Theory (DFT) Simulation [

78,

79]. First-Principles Modeling are mostly used to understand the mechanism of HE on metals in the nanoscale [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85]. Furthermore, the application of novel materials, coatings, and surface treatments aimed at mitigating HE effects has gained prominence, with a focus on industries such as aerospace, automotive, renewable energy, and infrastructure. Standardization efforts have evolved, with the development of improved testing protocols and guidelines to ensure the reliability and safety of critical components. Despite significant progress, challenges remain, including the need for more accurate predictive models, cost-effective mitigation strategies, and increased awareness of emerging technologies like hydrogen fuel cells and additive manufacturing [

86,

87,

88,

89,

90]. Interdisciplinary research collaborations and ongoing technological advancements continue to drive innovation in addressing the complexities of HE in modern materials and engineering applications.

Looking ahead, the future of hydrogen embrittlement (HE) research holds promise for significant advancements and innovations. Continued interdisciplinary collaboration between materials scientists, engineers, and computational researchers will drive progress in understanding HE mechanisms across a wide range of materials and environmental conditions. Future research efforts are anticipated to focus on developing predictive models that account for the complex interplay between microstructural features, hydrogen diffusion kinetics, and mechanical loading conditions. Additionally, the emergence of advanced characterization techniques, such as in-situ imaging and spectroscopy, will enable real-time monitoring of hydrogen interactions at the nanoscale, providing invaluable insights for designing hydrogen-resistant materials and mitigating HE risks in critical applications. Furthermore, there is growing anticipation for integrating machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches to accelerate the discovery of novel mitigation strategies and optimize material design for enhanced resistance to HE. Overall, the trajectory of HE research is poised to address current challenges and pave the way for safer and more reliable materials in the future.

2. Hydrogen Embrittlement Phenomena

Hydrogen embrittlement (HE) represents a critical challenge in the field of materials science, particularly in industries that rely on metals and alloys exposed to hydrogen-rich environments. This phenomenon leads to the degradation of mechanical properties in otherwise strong and ductile materials, causing them to become brittle and susceptible to sudden failure. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of hydrogen embrittlement is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies, especially in high-stakes industries like aerospace, automotive, and energy. The following review highlights key mechanisms, including Hydrogen-Enhanced Local Plasticity (HELP), Hydrogen-Enhanced Decoherence (HEDE), Adsorption-Induced Dislocation Emission (AIDE), and others that contribute to hydrogen embrittlement.

One of the primary mechanisms associated with hydrogen embrittlement is Hydrogen-Enhanced Local Plasticity (HELP). HELP occurs when hydrogen atoms increase the mobility of dislocations within the crystal lattice of a metal, causing localized softening and a reduction in yield strength. This effect promotes planar slip and accelerates plastic deformation, making the material more susceptible to failure under applied stresses. Studies by Barrera et al. [

91], and Dwivedi & Vishwakarma et al. [

92] demonstrate that HELP plays a significant role in the embrittlement of metals such as steel, particularly in components used in high-pressure hydrogen environments like pipelines and pressure vessels.

In addition to HELP, Hydrogen-Enhanced Decoherence (HEDE) is another widely recognized mechanism contributing to hydrogen embrittlement. HEDE refers to the weakening of atomic bonds within a material, particularly at grain boundaries, due to the presence of hydrogen. This mechanism often leads to a brittle-to-ductile transition, particularly under high hydrogen concentrations, as the material becomes more prone to fracture. Oriani & Josephic et al. [

41] and Gnagloff et al. [

42] provide comprehensive studies on how HEDE affects the cohesive strength of materials, accelerating crack propagation and eventual failure.

The Adsorption-Induced Dislocation Emission (AIDE) mechanism is another critical factor in hydrogen embrittlement. Hydrogen atoms tend to adsorb at the surface of a material or at crack tips, facilitating the nucleation and emission of dislocations. This process alters the material's fracture behavior, often initiating cracks at regions of high hydrogen concentration. Research by Lynch et al. [

50] and Birnbaum & Sofronis et al. [

48] highlights the significant role of AIDE in metals exposed to hydrogen during processes such as electroplating and pickling, where hydrogen is absorbed into the material's surface, leading to embrittlement.

Other mechanisms, such as Hydrogen-Enhanced Strain-Induced Vacancy (HESIV), contribute to hydrogen embrittlement by promoting the formation and clustering of vacancies within the material’s lattice. These vacancies weaken interatomic bonds, reducing the material's fracture toughness and increasing its susceptibility to crack propagation under stress. This effect is further amplified in high-strength steels and alloys, as shown in studies by Hirth et al. [

35] and McPherson & Cataldo et al. [

93].

Overall, hydrogen embrittlement is a multifaceted phenomenon, with each mechanism playing a role depending on the material, hydrogen concentration, and stress conditions. By understanding the interplay between HELP, HEDE, AIDE, and other related mechanisms, engineers and materials scientists can develop more effective strategies to prevent hydrogen-induced failures in critical components. Advanced modeling techniques, such as those developed by Song & Curtin et al. [

75] combined with modern non-destructive testing methods, offer promising solutions for predicting and mitigating hydrogen embrittlement. Furthermore, computational tools such as density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics simulations have improved the accuracy of predictive models. These advancements are crucial for designing hydrogen-resistant materials, particularly for industries like aerospace and energy, where hydrogen exposure is inevitable.

3. Protection Mechanisms Against Hydrogen Embrittlement

Hydrogen embrittlement (HE) poses a significant challenge in various industrial applications, especially in high-strength steels and alloys used in environments prone to hydrogen exposure. To mitigate the risks associated with HE, several protection mechanisms have been developed, focusing on controlling hydrogen ingress and minimizing stress concentrations. These mechanisms include cathodic protection, anodic protection, surface coatings, material selection, and diffusion barriers.

Cathodic Protection Techniques play a critical role in reducing hydrogen embrittlement by preventing the electrochemical reactions that lead to hydrogen absorption. Galvanic Cathodic Protection (GCP) involves connecting the susceptible metal to a more anodic material, such as zinc or magnesium, which preferentially corrodes and protects the base material. Impressed Current Cathodic Protection (ICCP) offers more precise control by applying an external electric current, which helps counteract the corrosion process, preventing hydrogen from penetrating the material's surface et al. [

50,

79,

94,

95,

96,

97].

Anodic Protection Techniques, on the other hand, focus on passivating the metal surface. Passive anodic protection involves the natural formation of a stable oxide layer that acts as a barrier to hydrogen diffusion. This approach is commonly seen in stainless steels and aluminum, where the oxide layer minimizes hydrogen ingress. Active anodic protection employs external currents to further enhance oxide layer formation, offering precise control over the protective film’s morphology [

81,

91]. This method is particularly beneficial in environments where passive layers may degrade due to harsh conditions, such as variations in pH or temperature.

Surface Coatings and Protective Coating Methods form a physical barrier between the metal and the hydrogen-rich environment. Organic coatings, such as epoxy or polyurethane, and inorganic coatings, including zinc and aluminum, provide excellent protection. These coatings are applied using methods like spray coating, electroplating, or thermal spraying. Coating effectiveness is typically assessed through corrosion resistance tests, including salt spray and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, ensuring long-term durability and performance et al. [

92,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102].

Material Selection and Design Recommendations are fundamental strategies in combating hydrogen embrittlement. Selecting materials with high resistance to hydrogen diffusion, such as alloys with elements like nickel, chromium, and molybdenum, is critical in high-risk applications. These elements enhance the material’s ability to trap hydrogen and prevent it from diffusing into the microstructure, reducing the risk of embrittlement [

103]. In addition, designing components with minimal stress concentrations and smooth geometries reduces the likelihood of crack initiation in hydrogen-susceptible regions [

104].

Hydrogen Diffusion Control through barrier materials and coatings is another key protection mechanism. Ceramics and polymers can act as diffusion barriers, preventing hydrogen from entering the material’s matrix. These barriers are particularly effective in high-temperature applications where hydrogen diffusion rates increase. Furthermore, modeling and simulation techniques, such as finite element analysis (FEA), allow engineers to predict hydrogen diffusion pathways and optimize barrier placement to enhance protection [

91].

In conclusion, mitigating hydrogen embrittlement requires a multifaceted approach, combining cathodic and anodic protection methods, surface coatings, appropriate material selection, and advanced modeling techniques. By addressing both hydrogen ingress and stress concentrations, these strategies significantly enhance the longevity and reliability of components exposed to hydrogen-rich environments.

4. Discussion About Hydrogen Embrittlement in Aviation by Incident Reports

Hydrogen embrittlement is a critical phenomenon in the aviation industry that has been linked to several catastrophic failures in high-strength steels and alloys. This type of embrittlement occurs when hydrogen atoms penetrate into the metal's microstructure, weakening the material and making it susceptible to sudden, brittle fractures. Hydrogen embrittlement is particularly dangerous because it can remain undetected until the moment of failure. The affected metal may show no outward signs of damage or degradation, but under operational stresses, it can fail suddenly and catastrophically. Given the extreme stresses that aircraft components endure during operation, even a small amount of hydrogen contamination can have severe consequences.

Aviation components, particularly those made from high-strength materials such as landing gear cylinders, drive gears, and bolts, are especially vulnerable to hydrogen embrittlement. These components are often subjected to manufacturing and maintenance processes that can introduce hydrogen, such as electroplating, acid pickling, or surface cleaning. Although dehydrogenation treatments are often applied after these processes to remove absorbed hydrogen, residual hydrogen can sometimes remain trapped within the metal, leading to the potential for embrittlement over time. The failure typically occurs at stress concentration points, such as cracks or defects, where hydrogen accumulates and weakens the atomic bonds, causing the material to fracture under load.

The following incident reports highlight real-world examples where hydrogen embrittlement played a significant role in the failure of critical aviation components. These cases, including failures in helicopter drive systems and aircraft landing gears, demonstrate the widespread impact that hydrogen embrittlement can have on aviation safety. Each of these incidents underscores the need for stringent material control, enhanced quality assurance, and more advanced post-manufacturing treatments to mitigate the risks associated with hydrogen embrittlement. While current detection methods and preventive measures are effective to some extent, these reports show that hydrogen embrittlement remains a significant challenge that the aviation industry must continue to address to prevent future failures.

In many cases, hydrogen embrittlement has been linked to the electrochemical processes used during component manufacturing. Processes such as electroplating and acid cleaning can introduce hydrogen into the metal if not carefully controlled. Even with standard dehydrogenation procedures, small amounts of hydrogen can remain in the material, which, over time and under repeated stress, can cause microscopic cracks to form and propagate. These cracks often lead to sudden failure, as seen in several documented aviation incidents, where components like output drive gears or landing gear cylinders fractured due to hydrogen embrittlement. Such failures, often occurring without warning, pose serious safety risks and highlight the critical importance of maintaining rigorous quality control throughout the manufacturing and maintenance lifecycle of aviation components.

4.1. Failure of the Bell 412EP Helicopter (ERA10TA493)

On September 22, 2010, a Bell 412EP helicopter, operated by the New York City Police Aviation Unit, was involved in a critical incident during its final approach to Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, New York. The helicopter, carrying six crew members, experienced a sudden mechanical failure, forcing an emergency autorotation landing into Jamaica Bay. While all occupants sustained only minor injuries, the helicopter itself suffered significant damage, particularly to its powerplant system. As seen in

Figure 1, the helicopter's flotation devices deployed upon impact with the water, allowing it to remain afloat and preventing it from sinking, despite the substantial damage it sustained.

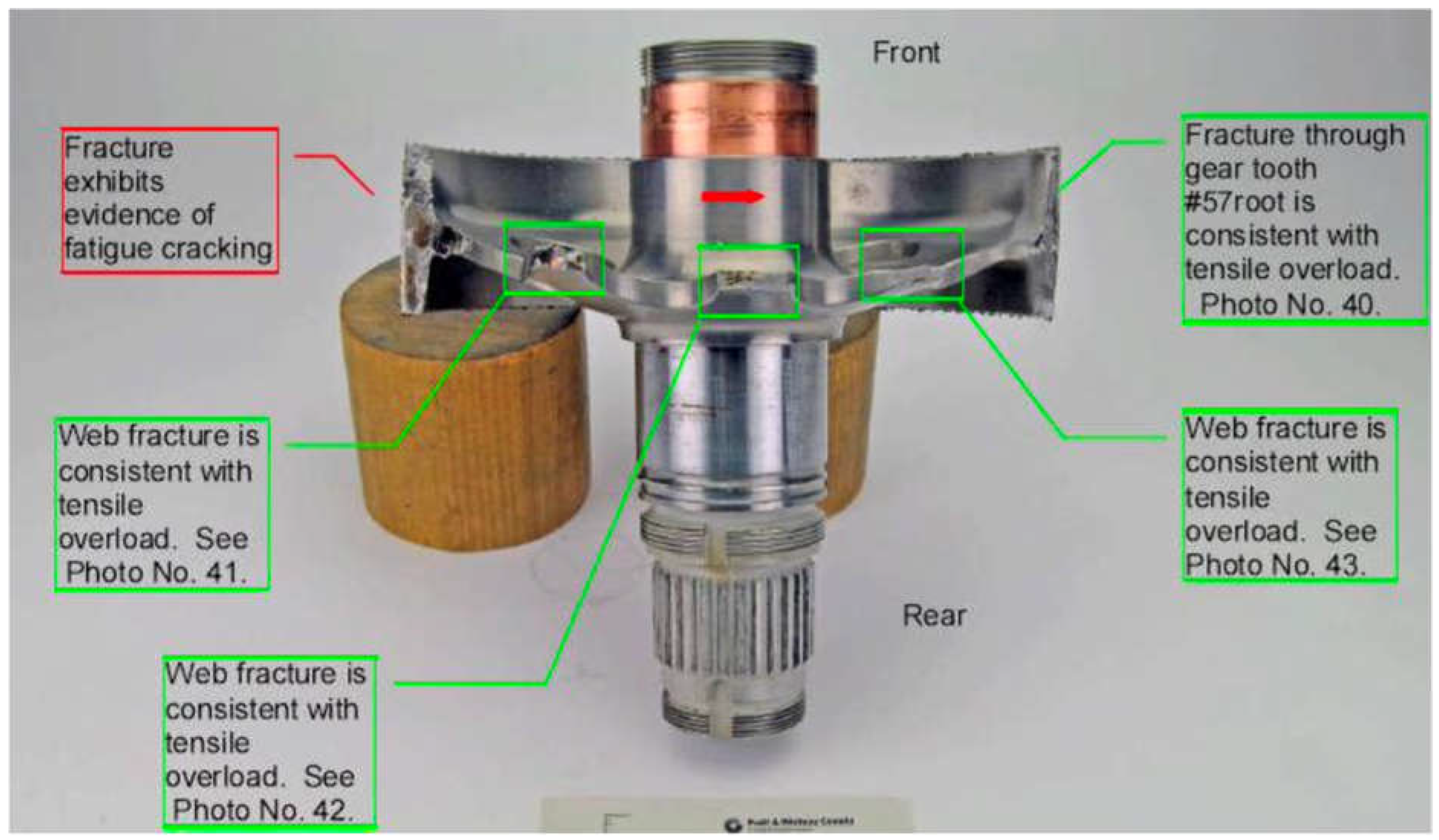

The flotation devices deployed upon water contact, preventing the helicopter from sinking. Subsequent investigations into the incident revealed that the failure originated from a fatigue fracture in the output drive gear (ODG) of the helicopter's reduction gearbox as seen in the

Figure 2. This fracture was traced back to a crack that initiated at the root of one of the gear teeth. Metallurgical analysis showed that this crack was a result of hydrogen embrittlement—a phenomenon where hydrogen atoms penetrate the metal, causing it to become brittle and susceptible to cracking. The crack initiation and its propagation, as observed in the metallurgical analysis, are consistent with both intergranular and transgranular cracking, which are characteristic signs of hydrogen embrittlement. the intergranular cracking initiated due to the presence of hydrogen atoms at the grain boundaries, which weakened the bonds between metal atoms, making the material more susceptible to cracking under stress.

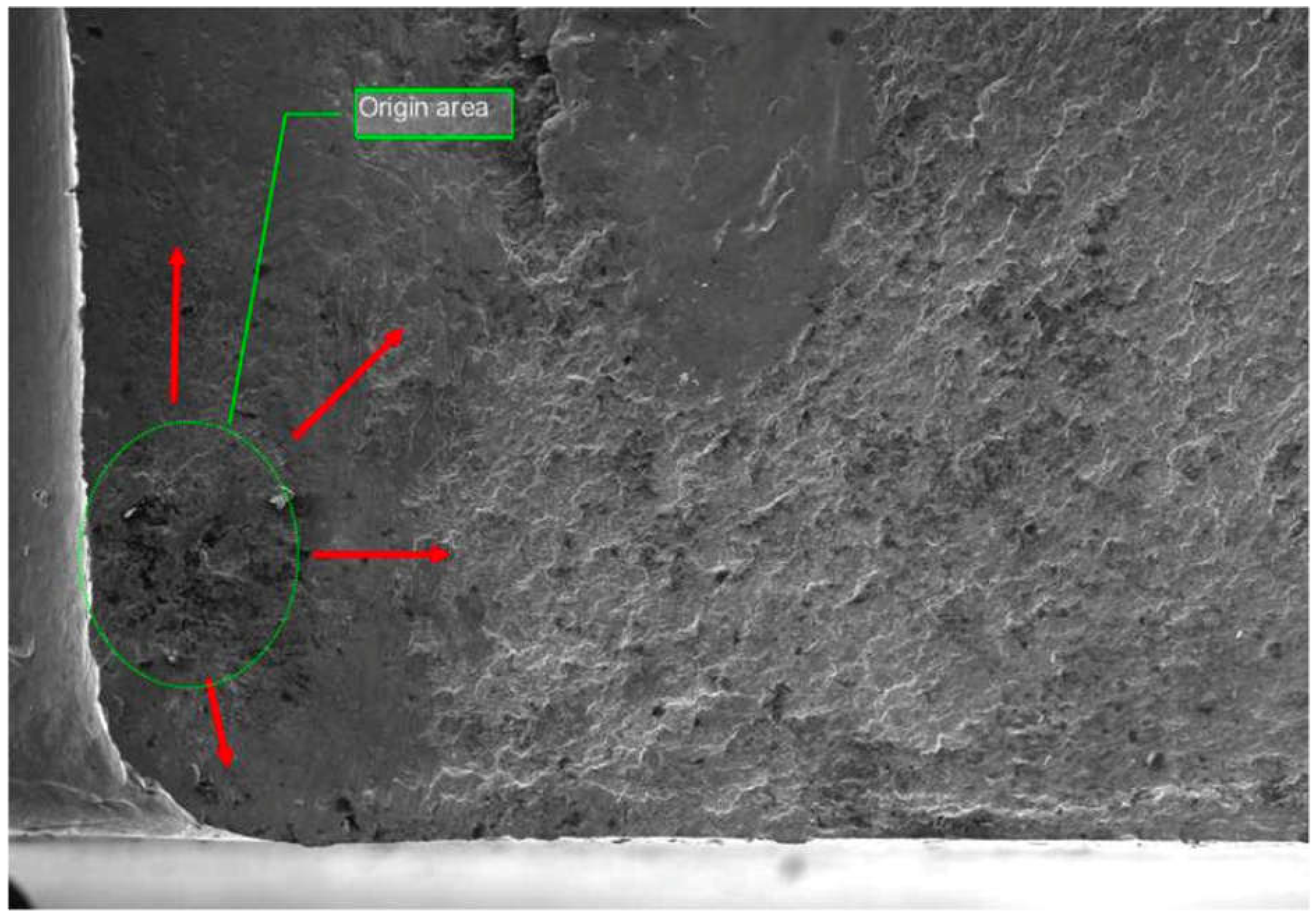

The crack, initiated at the root of a gear tooth, eventually led to the failure of the entire component. The microscopic examination of the fracture surface, as depicted in

Figure 3, highlighted the presence of intergranular cracking at the root of the gear tooth. This is a characteristic sign of hydrogen embrittlement, where cracks propagate along the grain boundaries of the metal. The analysis revealed both intergranular and transgranular crack propagation, further confirming the role of hydrogen embrittlement in the failure.

The output drive gear had undergone several electrochemical plating processes during its manufacture, followed by dehydrogenation steps designed to remove any absorbed hydrogen. Despite these precautions, the investigation found that residual hydrogen likely remained within the material, leading to the fatigue crack. The incident underscores the challenges associated with detecting and preventing hydrogen embrittlement, even with stringent manufacturing and maintenance practices.

During manufacturing, the output drive gear underwent multiple electrochemical plating processes, followed by dehydrogenation steps meant to remove any absorbed hydrogen. Despite these measures, the investigation found that residual hydrogen likely remained within the material, contributing to the fatigue crack formation. In

Figure 3, the microscopic examination of the fracture surface highlighted these effects, where the presence of intergranular cracking was notably evident.

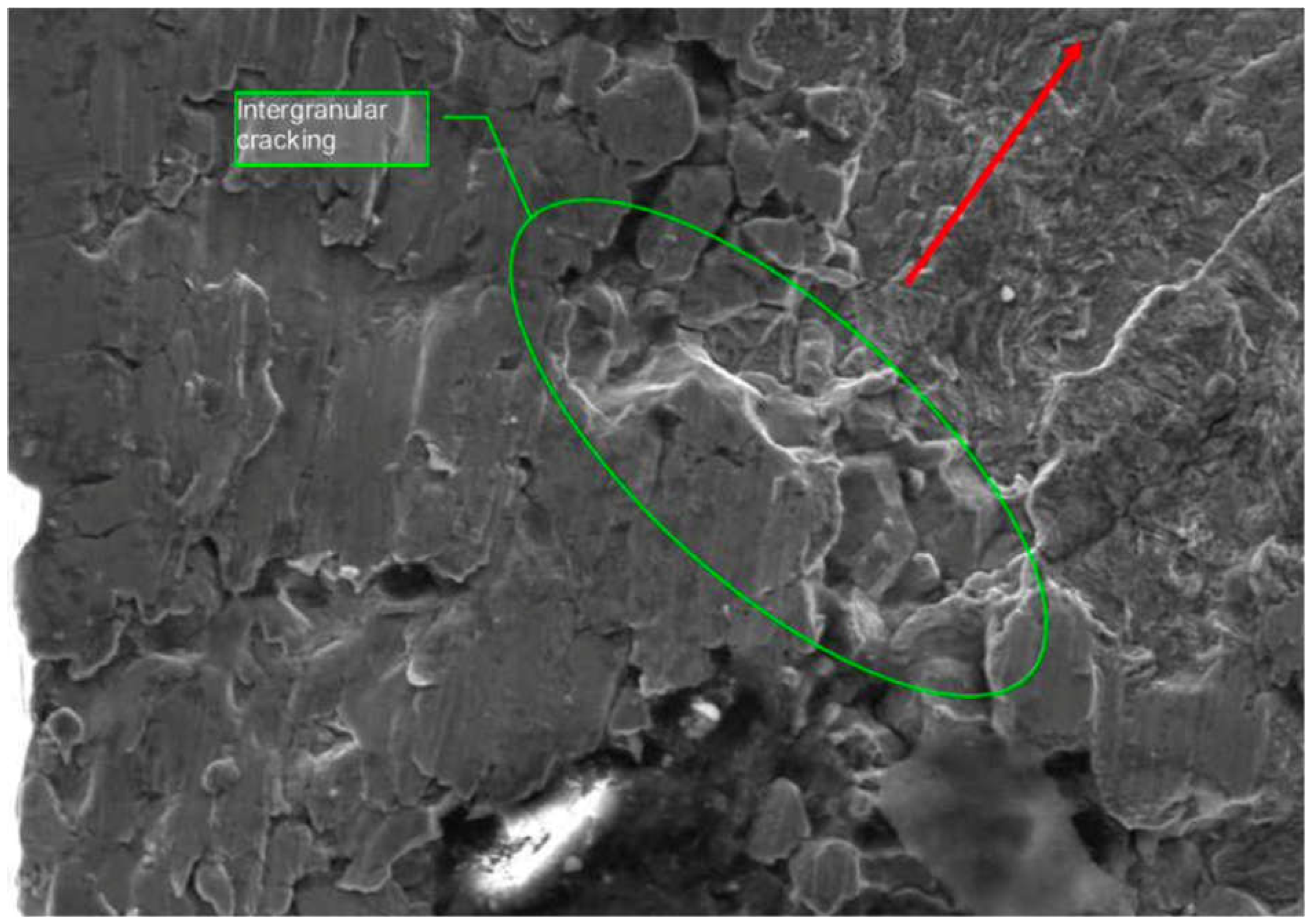

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined that the probable cause of the incident was the fatigue fracture of the ODG due to hydrogen embrittlement incurred during the manufacturing process, as seen in the microscopic view of the fracture surface in

Figure 4. This event highlighted the need for increased vigilance in material processing and quality control to prevent similar failures in aviation components. As a result of the incident, the affected components from the same manufacturing batch were recalled preventing further risks.

The hydrogen was likely introduced during the electrochemical plating process used in the gear's manufacturing. Although dehydrogenation treatments were applied to remove absorbed hydrogen, the analysis showed that these treatments were insufficient, leaving residual hydrogen that ultimately led to the component’s failure. The fatigue cracks that propagated from this region, leading to the final fracture, is consistent with the effects of hydrogen embrittlement.

The findings from the Bell 412EP helicopter incident are consistent with extensive literature on hydrogen embrittlement in high-strength steels and alloys. According to Lynch et al. [

50] hydrogen embrittlement occurs when hydrogen atoms enter the metal lattice, particularly at grain boundaries, leading to premature failure under stress

1. This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in components exposed to cyclic loading, such as gears in helicopter transmissions, where repeated stress can accelerate crack initiation and propagation.

Moreover, Birnbaum and Sofronis et al. [

48] highlight the role of electrochemical processes in introducing hydrogen into the metal. They explain that during processes such as electroplating, hydrogen ions can be reduced at the metal surface, leading to hydrogen absorption into the metal’s microstructure

2. The Bell 412EP’s output drive gear, which underwent electrochemical plating, is a prime example of how residual hydrogen can remain in the material, even after dehydrogenation treatments.

In conclusion, the microstructural evidence from the failed output drive gear and the extensive literature on hydrogen embrittlement strongly support the conclusion that hydrogen embrittlement was the primary cause of the component’s failure. This incident underscores the critical need for improved detection and prevention measures during the manufacturing process, as well as the importance of ongoing research into materials science to ensure the safety and reliability of aviation components.

4.2. Failure of the Bell 222U Helicopter (CEN10FA291)

On June 2, 2010, a Bell 222U helicopter, operated by CareFlite, experienced a catastrophic in-flight breakup during a post-maintenance flight near Midlothian, Texas. The helicopter, piloted by an airline transport pilot and accompanied by a mechanic, encountered structural failure that led to the separation of critical components, including the tail boom and main rotor hub. Witnesses reported seeing debris falling from the helicopter before it collided with the ground and erupted into flames, tragically killing both crew members.

Figure 4 shows the wreckage and first responders on the scene, as captured by the Midlothian Fire Department.

Figure 4.

Photo of first responders on-scene after the Bell 222U crash, with visible black smoke and the main wreckage (Courtesy: Midlothian Fire Department).

Figure 4.

Photo of first responders on-scene after the Bell 222U crash, with visible black smoke and the main wreckage (Courtesy: Midlothian Fire Department).

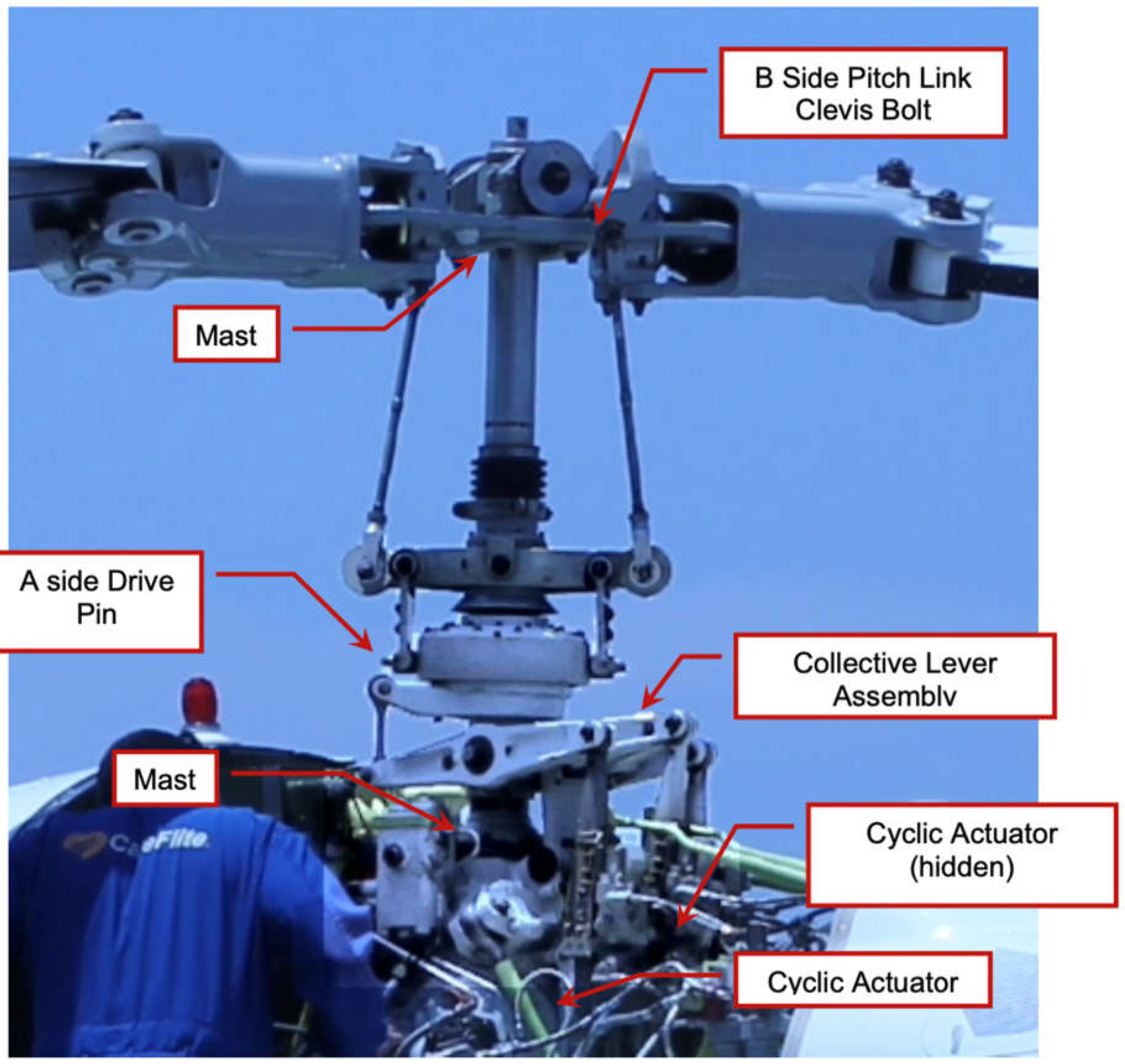

Before the incident, the rotor components of the helicopter were intact and fully operational.

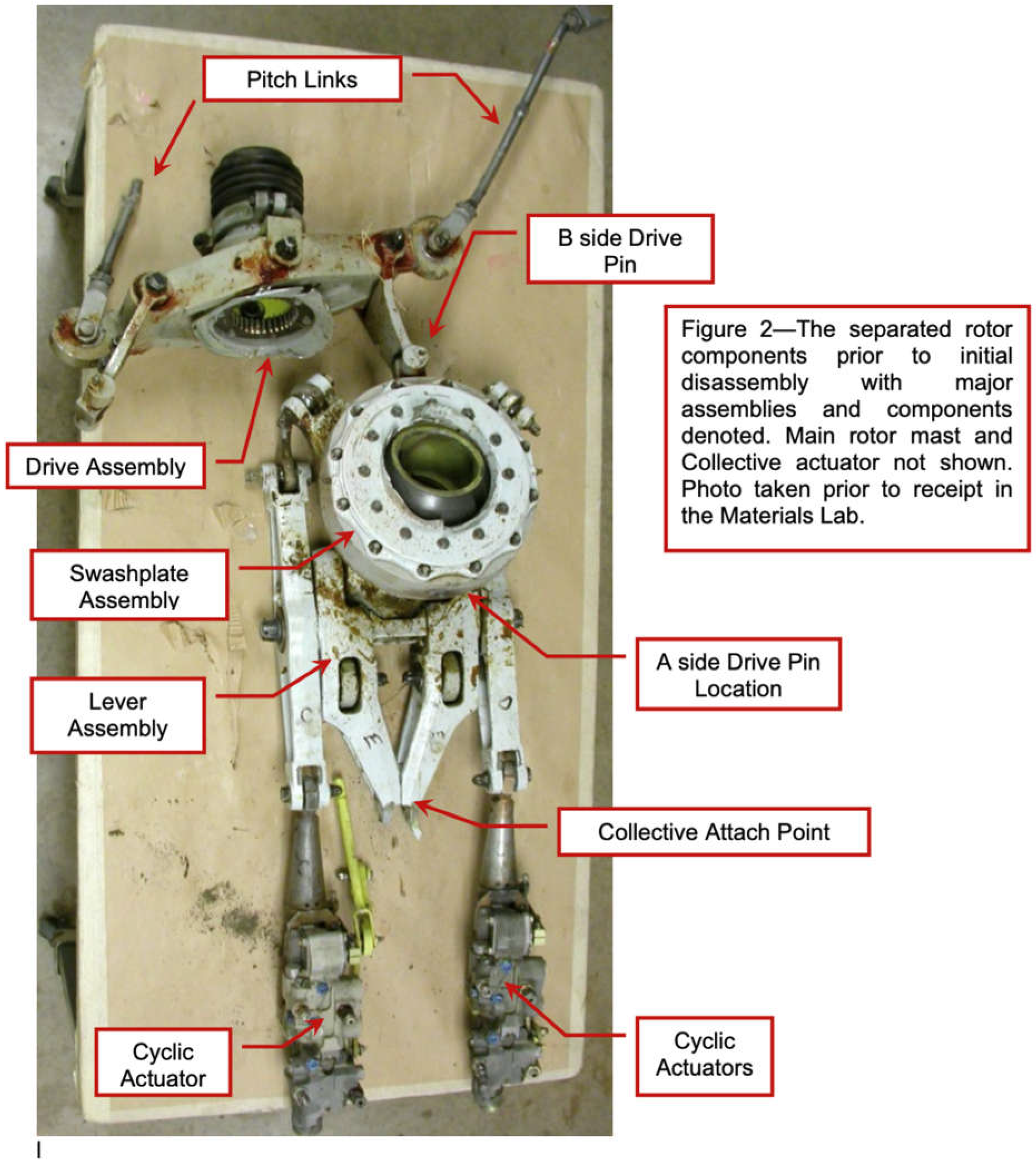

Figure 5 shows the rotor head of the Bell 222U helicopter before the accident, highlighting key components such as the A-side drive pin, the B-side pitch link, and the cyclic actuators.

The investigation identified the failure of the A-side drive pin in the swashplate assembly as the primary cause of the in-flight breakup. Metallurgical analysis revealed that the pin fractured due to overstress, but the fracture surface exhibited brittle cleavage features and intergranular separations, which are consistent with hydrogen embrittlement. Hydrogen levels measured in the fractured pin ranged between 8.7 and 9.3 ppm, confirming the involvement of hydrogen in weakening the material.

Figure 6 shows the rotor components after separation, highlighting the failure points, including the A-side drive pin.

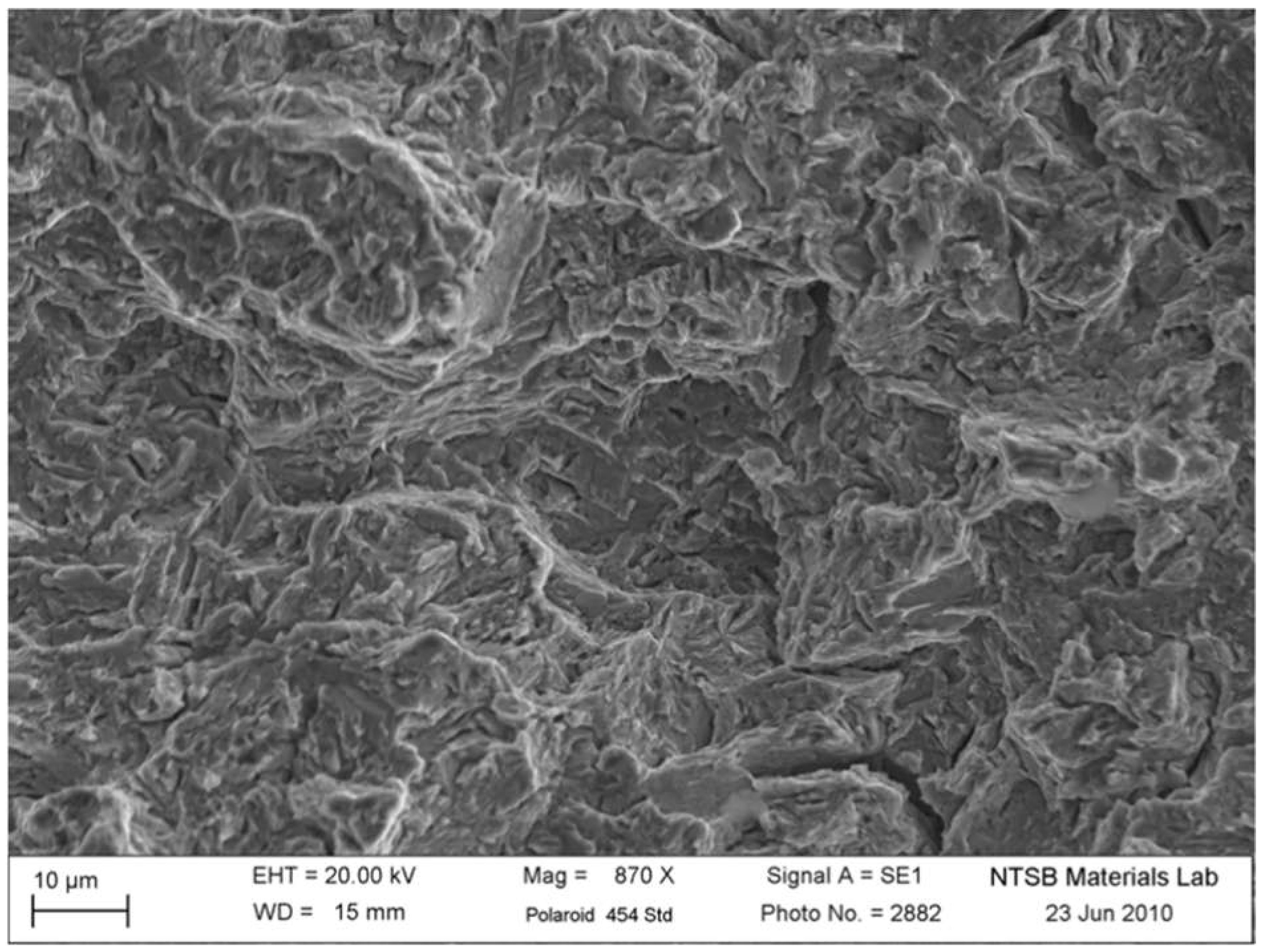

Further examination under a scanning electron microscope (SEM) provided critical evidence of the brittle failure mechanism.

Figure 7 shows the fractured surface of the A-side drive pin, with clear indications of brittle cleavage and intergranular separations. These SEM images highlight how hydrogen atoms migrated into areas of high stress within the material, causing the drive pin to fracture under conditions it would normally withstand.

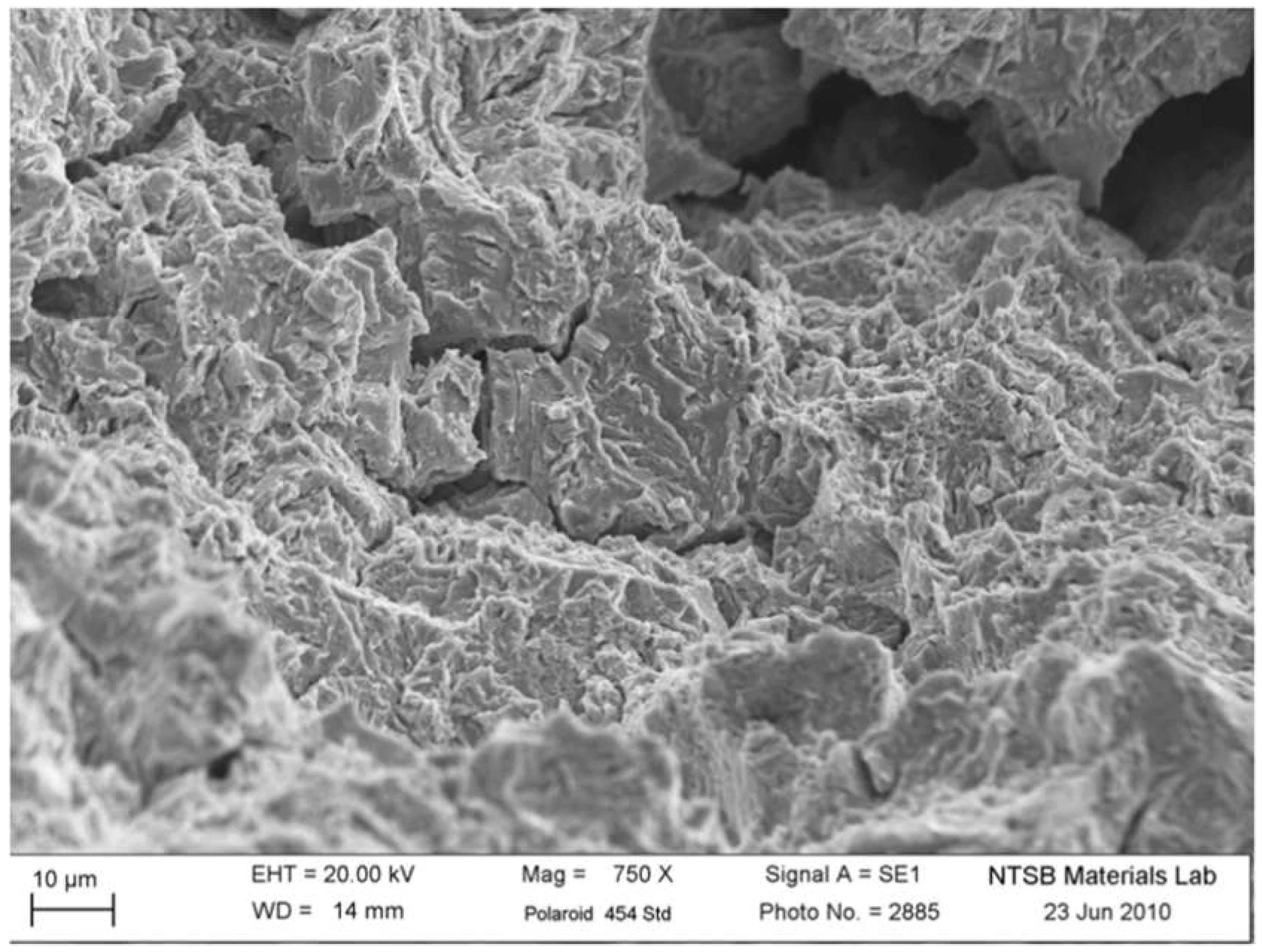

In addition to the primary fracture,

Figure 8 provides another SEM image showing multiple radial cracks on the washer face of the A-side pin. These cracks, observed at low magnifications, intersected the main fracture, further supporting the conclusion that hydrogen embrittlement played a significant role in the failure. This image underscores the localized plasticity near the fracture initiation sites, where hydrogen atoms likely accumulated.

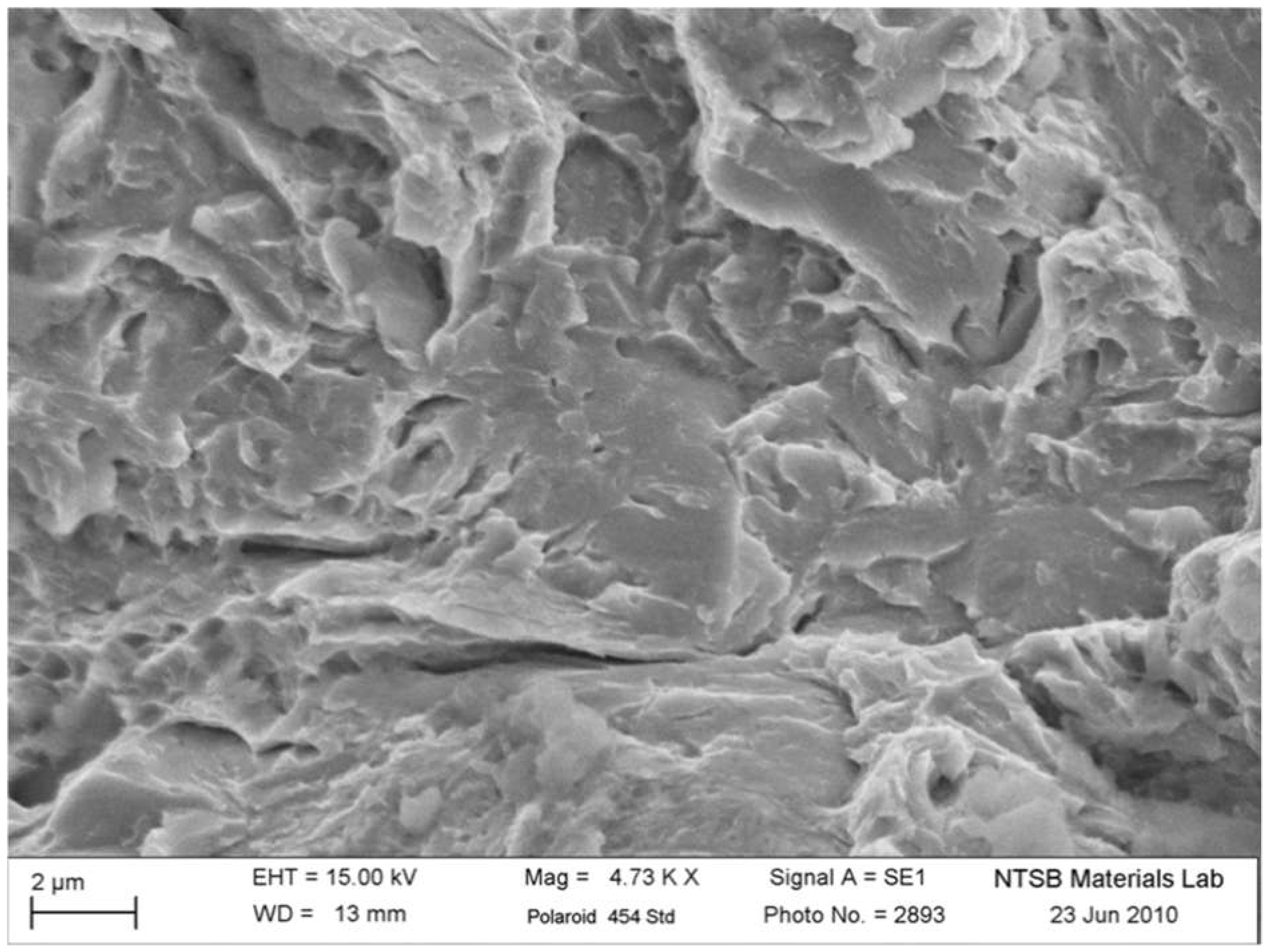

Moreover, SEM analysis at higher magnifications in

Figure 9 reveals ductile dimples adjacent to the main fracture, contrasting with the brittle cleavage areas. This observation shows that the fracture initiated in brittle areas due to hydrogen embrittlement and propagated until final failure, where localized ductility emerged in isolated regions.

The findings from the Bell 222U helicopter incident align with extensive research on hydrogen embrittlement in high-strength alloys. Lynch (2012) highlights how hydrogen embrittlement typically occurs when hydrogen atoms penetrate the metal lattice, particularly at grain boundaries, leading to brittle failure under operational stresses [

50]. This is especially common in components subjected to cyclic loading, like helicopter rotor systems, where repeated stress accelerates crack initiation and propagation. Birnbaum and Sofronis et al. [

48] also emphasize the role of electrochemical processes, such as cadmium plating, in introducing hydrogen into the metal. They explain that unless post-plating treatments like baking are applied, residual hydrogen can cause significant degradation in material properties, leading to failures like the one observed in the Bell 222U helicopter.

These findings emphasize the critical importance of hydrogen control during manufacturing and repair processes in aviation components. The failure of the Bell 222U highlights the need for rigorous post-treatment procedures, such as baking after cadmium plating, to ensure the removal of absorbed hydrogen and to prevent catastrophic failures in critical aerospace systems.

4.3. Failure of the Piper PA-32R-301T (IAD02FA091)

On September 8, 2002, a Piper PA-32R-301T (registration C-GKLY) suffered a catastrophic engine failure while cruising at 3,500 feet above Byram Township, New Jersey. The aircraft, operated by a private pilot, experienced a total loss of engine power due to the failure of the crankshaft gear retaining bolt. The failure led to a forced landing in wooded terrain, where the aircraft was destroyed on impact, killing the pilot and one passenger and seriously injuring two other passengers. Witnesses reported the aircraft maneuvering low over the trees before descending into the forest.

Figure 10 shows the crash site, with first responders on the scene following the incident.

The failure was traced to the engine’s crankshaft gear bolt, part number STD-2209, which was made of SAE J429 grade 8 steel. The bolt fractured due to hydrogen embrittlement; a failure mechanism linked to improper post-plating treatments of zinc-plated bolts. Prior to the incident, engines of this type were built with cadmium-plated bolts, but zinc-plated bolts had been substituted during production, leading to a known issue of bolt failures across various aircraft.

Figure 11 shows the crankshaft section of the Piper PA-32R-301T’s engine, including the fractured bolt and gear assembly as found during post-accident examination.

The Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) and metallographic analysis revealed key findings about the failure mode.

Figure 12 illustrates intergranular cracking and ductile failures present on the bolt’s fracture surface, highlighting the role of hydrogen embrittlement. The SEM image shows intergranular cracking along the fracture surface of the crankshaft bolt, indicating hydrogen-assisted cracking. The metallographic examination confirmed that the fracture initiated at the thread roots and propagated radially due to hydrogen accumulation.

The problem of hydrogen embrittlement in zinc-plated bolts was first identified by Lycoming in 1998, following similar failures in O-540-F1B5 engines installed in Robinson R44 helicopters. The bolts in those engines failed after as little as 19 hours of operation due to hydrogen embrittlement. As a precaution, Lycoming issued Special Service Advisory No. 48-798, which required operators to replace the zinc-plated bolts within 10 hours of operation. Despite these early warnings, the issue persisted in non-helicopter engines, such as the Piper PA-32R-301T involved in this accident.

By the time of the Piper accident, multiple failures of zinc-plated bolts had been documented in both helicopter and fixed-wing aircraft engines. In June 2002, a similar failure occurred in another Piper PA-32R-301 at 448 hours of operation. However, the extent of the issue was not fully realized until after the September 2002 crash, leading to an emergency Airworthiness Directive (AD) by the FAA, requiring the immediate replacement of all zinc-plated crankshaft gear retaining bolts.

The investigation into the Piper PA-32R-301T accident highlighted the severe consequences of hydrogen embrittlement in aerospace components. The substitution of cadmium-plated bolts with zinc-plated bolts, without adequate post-treatment baking to eliminate hydrogen, directly contributed to the catastrophic failure. This case emphasizes the need for rigorous material controls and thorough post-treatment procedures in the aviation industry to prevent hydrogen embrittlement-related failures in critical components.

The findings from this accident underscore the importance of implementing stringent post-plating treatments, including baking to remove hydrogen from zinc-plated components. Regular inspections of aerospace components known to be susceptible to hydrogen embrittlement should also be conducted. Furthermore, continuous communication between manufacturers, regulatory bodies, and operators is essential to ensure potential material issues are swiftly addressed. These preventive measures are crucial to safeguarding against future failures in high-strength alloy components used in critical aviation systems.

4.4. Failure of the Piper PA-32R-301 (MIA02LA108)

On June 7, 2002, a Piper PA-32R-301 (registration N697MA) suffered a catastrophic engine failure while conducting instrument approach practice at Key Field, Meridian, Mississippi. The aircraft, piloted by Dr. Mark Durelle Williams, was conducting a training flight under VFR conditions when a loud "pop" was heard, followed by a complete loss of engine power. The engine failure occurred at an altitude of approximately 500-600 feet, as the pilot was following the published missed approach for runway 01. Unable to maintain altitude, the pilot attempted to return to the runway but was forced to land in a field, where the aircraft impacted trees and flipped over. The pilot sustained serious injuries, and the aircraft was destroyed.

Figure 13 shows the aircraft wreckage after recovery to Meridian Aviation.

Subsequent investigation revealed that the engine failure was caused by the fracture of the crankshaft gear bolt, part number STD-2209, in the Lycoming IO-540-K1G5 engine (Serial No: L-25968-48A). The bolt failure led to the separation of the crankshaft gear from the rear of the crankshaft.

Figure 14 shows the disassembled components of the engine, including the failed crankshaft gear bolt, which was the primary cause of the engine failure.

A detailed examination of the crankshaft gear bolt by the Lycoming Materials Laboratory revealed that the failure was caused by hydrogen embrittlement. The bolt fractured through the second to fifth threads from the shank, and two additional cracks were found extending through the twelfth and thirteenth threads. These fractures exhibited intergranular separation, a hallmark of hydrogen-assisted cracking. The zinc plating on the bolt was identified as the source of the hydrogen, which penetrated the bolt material during the manufacturing process.

Figure 15 illustrates the SEM image of the fractured surface, showing intergranular separation caused by hydrogen embrittlement.

The investigation concluded that the most likely cause of the hydrogen embrittlement was inadequate post-plating treatments during manufacturing. Although the zinc plating conformed to the required thickness, the process may have induced hydrogen into the bolt material, which subsequently led to crack propagation under operational stresses. The crankshaft gear bolt failure resulted in the separation of the crankshaft gear, leading to a total loss of engine power.

This accident highlights the critical importance of quality control in manufacturing aviation components, particularly in preventing hydrogen embrittlement. The findings emphasize the need for stringent post-plating procedures, such as baking, to remove hydrogen from plated components. In addition to that, regular inspections of critical components, especially those subjected to cyclic loading, are essential to detect early signs of material degradation.

4.5. Failure of the Center Landing Gear on FedEx MD-11 (ENG08IA025)

On April 27, 2008, during a routine pre-flight inspection at Singapore Changi Airport (SIN), hydraulic fluid was discovered near the center landing gear (CLG) strut of a FedEx MD-11 aircraft (registration N595FE). A closer inspection revealed a vertical crack, approximately 33 inches long, along the aft side of the CLG strut cylinder. The crack was initially observed during a walkaround inspection and prompted an immediate investigation. The CLG strut cylinder was removed and sent to Hawker Pacific for teardown and further examination at the Boeing Southern California Materials Laboratory. The strut had accumulated 5,058 cycles since its reinstallation on February 22, 2001, and had a lifetime total of 9,379 cycles.

Figure 16 shows the initial findings from the inspection of the CLG strut, with the vertical crack clearly visible.

Metallurgical analysis revealed that the CLG strut cylinder failure was caused by intergranular (IG) cracking, which originated from surface contamination during a prior maintenance procedure. The failure was traced to improperly cleaning the surface before painting, where residual chemicals from paint removal solutions contributed to hydrogen embrittlement. The intergranular cracking extended deep into the wall of the cylinder, weakening the structure.

Figure 17 shows a cross-sectional view of the fracture origin area, highlighting the intergranular cracking.

During the teardown process, it was noted that cutting through the CLG cylinder with an abrasive wheel resulted in loud cracking noises, indicating a high level of residual stress in the material. This observation suggested that the failure was exacerbated by residual stresses in the cylinder wall. Visual and macroscopic examination confirmed that the fracture originated at the outer surface of the cylinder, approximately 18.2 inches from the bottom of the cylinder.

Figure 18 shows the fracture surface of the CLG cylinder after disassembly.

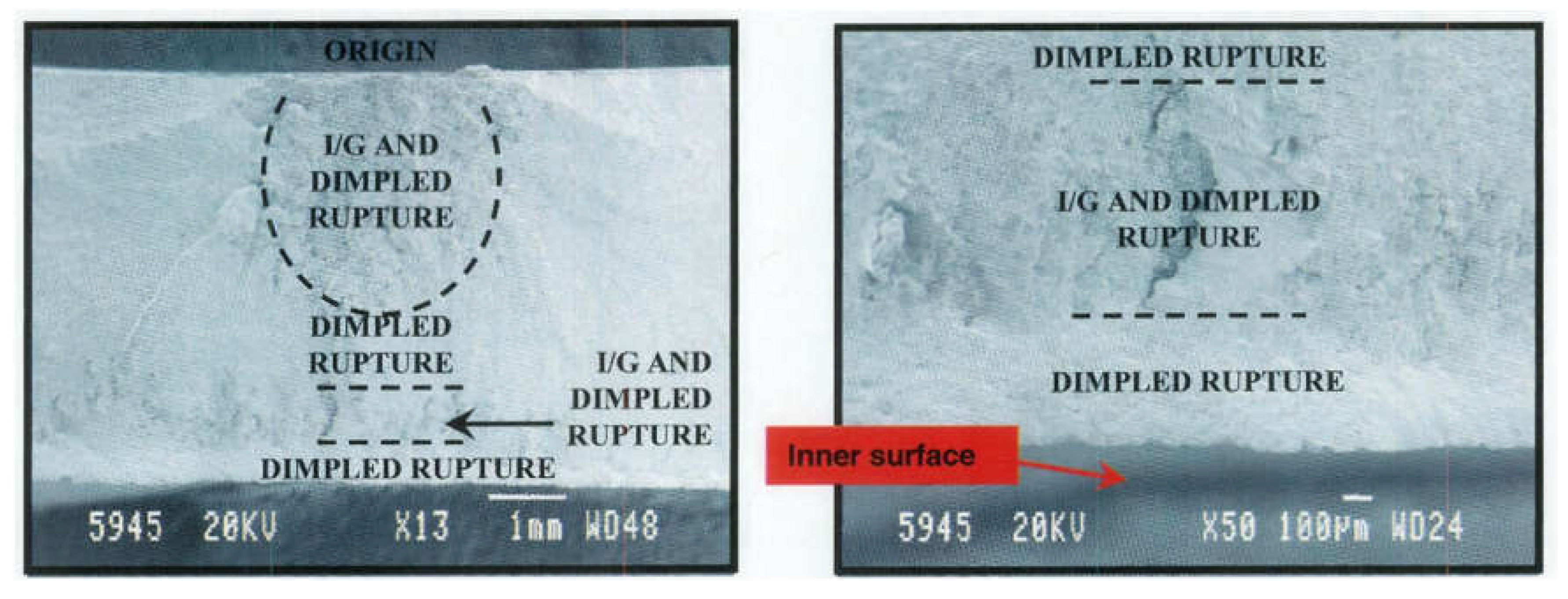

A more detailed Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) analysis revealed a mixed-mode failure. The fracture surface exhibited intergranular separation along the origin, and dimples indicated ductile overload in other areas. This mixed-mode fracture suggested that the initial failure occurred due to hydrogen embrittlement, which initiated the intergranular cracking. As the crack propagated, it transitioned into an overload failure mode.

Figure 19 illustrates the SEM image of the fracture surface, showing both intergranular facets and dimpled regions.

Further investigation into the paint layer on the CLG cylinder revealed evidence of surface sanding and paint repair in the region where the failure originated. It was concluded that the sanding and paint removal processes likely introduced chemical contamination, which contributed to the hydrogen embrittlement that caused the intergranular cracking. The improper handling of surface treatments during maintenance played a significant role in the structural failure of the CLG strut.

The analysis concluded that the failure of the center landing gear strut cylinder was due to hydrogen embrittlement, likely initiated by contamination from chemical cleaning agents used during a prior maintenance event. The hydrogen absorbed during the cleaning process, coupled with the stresses on the cylinder, led to the intergranular cracking that propagated through the structure.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations for the Future of Hydrogen Embrittlement in Aviation

As the aviation industry increasingly moves towards innovative materials and sustainable practices, addressing the challenges posed by hydrogen embrittlement (HE) has become a critical priority. One of the key areas of advancement is the development of hydrogen-resistant alloys specifically designed for aerospace applications. These advanced materials aim to enhance the mechanical properties of components exposed to hydrogen, such as high-strength steel and titanium alloys commonly used in aircraft structures and engines. Nanotechnology is also emerging as a game-changer, offering the potential to create coatings and materials with superior resistance to hydrogen penetration, which could significantly improve the durability and safety of aviation components operating in high-stress environments.

In addition to material innovations, modeling, and simulation technologies have shown promising developments for predicting and mitigating hydrogen embrittlement in aviation. Techniques such as finite element analysis (FEA) are now employed to model hydrogen diffusion and assess the structural integrity of critical aircraft systems under hydrogen exposure. Furthermore, multi-scale modeling advances our understanding of how hydrogen interacts with material microstructures at both atomic and macroscopic levels. These predictive tools are essential for designing next-generation aircraft that are both lightweight and resistant to HE-related failures, ensuring long-term safety and performance in the field.

Another significant advancement for aviation is the incorporation of real-time hydrogen monitoring systems. Sensors capable of detecting hydrogen concentrations with high accuracy can be integrated into aircraft systems, providing early warnings of embrittlement risks. Paired with predictive analytics, these technologies will enable proactive maintenance strategies, reducing the likelihood of catastrophic failures. Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods, such as high-frequency ultrasonic testing and acoustic emission monitoring, are also evolving to detect microscopic hydrogen-related damage before it can propagate and cause serious issues.

In the future, collaboration between materials scientists, aerospace engineers, and regulatory bodies will be crucial for overcoming the challenges of hydrogen embrittlement in aviation. Additive manufacturing holds great promise for producing components with tailored resistance to hydrogen, enabling the creation of complex, lightweight structures with enhanced durability. Furthermore, as hydrogen becomes an increasingly important energy source for aviation (through hydrogen fuel cells or hydrogen-powered engines), hydrogen storage and transportation technology advancements will play a vital role in ensuring hydrogen's safe and efficient integration into aerospace operations.

In conclusion, the aviation industry must continue to invest in hydrogen embrittlement research and development to ensure the safety and reliability of future aircraft. By adopting innovative materials, cutting-edge detection technologies, and advanced modeling tools, the industry can effectively manage the risks associated with hydrogen exposure, supporting the shift toward sustainable aviation technologies in the coming decades.

Figure 1.

The Bell 412EP helicopter resting in Jamaica Bay after the emergency landing.

Figure 1.

The Bell 412EP helicopter resting in Jamaica Bay after the emergency landing.

Figure 2.

Detailed view of the fractured output drive gear from the reduction gearbox.

Figure 2.

Detailed view of the fractured output drive gear from the reduction gearbox.

Figure 3.

Close-up of the origin region of the fatigue crack on the output drive gear, showing the initial intergranular cracking due to hydrogen embrittlement.

Figure 3.

Close-up of the origin region of the fatigue crack on the output drive gear, showing the initial intergranular cracking due to hydrogen embrittlement.

Figure 4.

Microscopic view of the fracture surface, showing the distinct patterns of fatigue crack propagation starting from the hydrogen-embrittled region.

Figure 4.

Microscopic view of the fracture surface, showing the distinct patterns of fatigue crack propagation starting from the hydrogen-embrittled region.

Figure 5.

Image showing the rotor head of the Bell 222U helicopter before the accident, with critical components identified.

Figure 5.

Image showing the rotor head of the Bell 222U helicopter before the accident, with critical components identified.

Figure 6.

Separated rotor components prior to disassembly, highlighting the critical assemblies (swashplate, drive assembly, and pitch links).

Figure 6.

Separated rotor components prior to disassembly, highlighting the critical assemblies (swashplate, drive assembly, and pitch links).

Figure 7.

SEM image showing the fractured A-side drive pin with brittle cleavage and intergranular separations.

Figure 7.

SEM image showing the fractured A-side drive pin with brittle cleavage and intergranular separations.

Figure 8.

SEM image of radial cracks on the washer face of the A-side pin, showing areas of localized plasticity.

Figure 8.

SEM image of radial cracks on the washer face of the A-side pin, showing areas of localized plasticity.

Figure 9.

Higher magnification SEM image showing the transition between brittle cleavage and ductile dimples on the A-side drive pin fracture surface.

Figure 9.

Higher magnification SEM image showing the transition between brittle cleavage and ductile dimples on the A-side drive pin fracture surface.

Figure 10.

Photo of first responders at the crash site of the Piper PA-32R-301T, showing wreckage and the fire that followed the forced landing (Byram Township Fire Department).

Figure 10.

Photo of first responders at the crash site of the Piper PA-32R-301T, showing wreckage and the fire that followed the forced landing (Byram Township Fire Department).

Figure 11.

Image of the crankshaft assembly and fractured crankshaft gear retaining bolt after disassembly.

Figure 11.

Image of the crankshaft assembly and fractured crankshaft gear retaining bolt after disassembly.

Figure 12.

SEM image showing intergranular cracking along the fracture surface of the crankshaft bolt, indicating hydrogen-assisted cracking.

Figure 12.

SEM image showing intergranular cracking along the fracture surface of the crankshaft bolt, indicating hydrogen-assisted cracking.

Figure 13.

Front view of the aircraft wreckage after recovery at Meridian Aviation.

Figure 13.

Front view of the aircraft wreckage after recovery at Meridian Aviation.

Figure 14.

Image of the disassembled engine components, highlighting the fractured crankshaft gear bolt (P/N STD-2209).

Figure 14.

Image of the disassembled engine components, highlighting the fractured crankshaft gear bolt (P/N STD-2209).

Figure 15.

SEM image under 1000x magnification showing intergranular separation on the fractured surface of the crankshaft gear bolt (P/N STD-2209), indicating hydrogen-assisted cracking.

Figure 15.

SEM image under 1000x magnification showing intergranular separation on the fractured surface of the crankshaft gear bolt (P/N STD-2209), indicating hydrogen-assisted cracking.

Figure 16.

Photograph of the cracked CLG strut cylinder, showing the longitudinal crack along the aft side.

Figure 16.

Photograph of the cracked CLG strut cylinder, showing the longitudinal crack along the aft side.

Figure 17.

Cross-sectional view of the CLG strut cylinder, showing the intergranular cracking that initiated the failure.

Figure 17.

Cross-sectional view of the CLG strut cylinder, showing the intergranular cracking that initiated the failure.

Figure 18.

The fracture surface of the CLG cylinder shows the location of the crack and the progression of failure.

Figure 18.

The fracture surface of the CLG cylinder shows the location of the crack and the progression of failure.

Figure 19.

SEM image of the fracture surface, showing a combination of intergranular cracking and ductile overload.

Figure 19.

SEM image of the fracture surface, showing a combination of intergranular cracking and ductile overload.