1. Introduction

Inadequate fluid intake or fluid restriction processes lead to core temperature values rising to ~40

o C in athletes [

1]. Increased core temperature causes physiological stress and a gradual decrease in body water through sweating rate. Hypohydration, defined by a 1–2% decrease in body weight during exercise, is widely acknowledged as the threshold where performance impairments in coordination, cognitive function, and reaction time.[

1,

2]. Previous study reports indicate that adolescent athletes can only meet 2/3 of BM their fluid needs if they don't prevent their body water loss during training and competition [

3]. This situation of the need to regulate fluid intake processes in adolescent athletes and to examine the effects of different fluid intake types and processes on different performance outcomes, especially under dehydration conditions. Few studies have examined fluid intake processes under exercise-associated dehydration conditions in the adolescent population.

High-intensity and intermittent sports activities, and sweat losses caused by an increased core temperature reduce body water by 1.0-1.6 L per hour (h.). These processes are most common in shooting-based sports such as handball, basketball, tennis, and cricket [

4,

5]. The literature, studies evaluating the shooting performance of adolescent athletes under hypohydration conditions showed that adolescent tennis players had decreases in service accuracy (~30%) and stroke accuracy (~69%) [

6]. In another study [

7], it was reported that the shooting accuracy and shooting speed of adolescent cricket players decreased in hypohydration conditions and similar hypohydration conditions negatively affected shooting accuracy in basketball players [

8]. In addition, studies recommend fluid intake such as water intake, sports drink intake, etc. in terms of general health and performance decline.

Fluid intake aims to prevent the performance-impairing effects of hypohydration that occurs by administering the fluid lost during exercise with preferred beverages in specified periods and to increase performance [

1,

3]. In this process, water intake creates a stabilizing effect, but it is less preferred by athletes due to its tastelessness. Flavored sports drinks prepared with carbohydrates and electrolytes are preferable [

1]. When the relationship between shooting accuracy and fluid intake is considered, water intake maintains the shooting accuracy and even provides low-level (3–4%) increases [

9]. Sports drink contributes to performance increases by delaying physiological deterioration with carbohydrates and electrolytes in their contents [

10,

11]. Adolescents have larger body surface area-to-mass ratios and variable sweat rates, requiring specialised hydration approaches, especially in high-intensity sports such as handball [

1] . In a small number of studies focusing on adolescent athletes; while shooting accuracy and velocity of adolescent basketball players did not change under hypohydration conditions, increased performance was observed with sports drink intake [

3]. In another study, it was reported that sports drinks consumed during the training session made an indirect contribution to the increase in shooting accuracy rate at the end of training [

12].

Although the number of adolescent handball players in Europe is approximately one million [

13,

14], the relationship between fluid intake, fluid loss, and performance in this population has been discussed to a limited extent. Especially there are no studies on the effect of fluid intake on shooting performance in adolescent handball players. For these reasons, this study aimed to investigate the effects of fluid restriction and different types of fluid intake on shooting performance and shooting speed in adolescent handball players.

Main hypotheses of this study; i) fluid restriction during training may impair shot accuracy and speed in adolescent handball players, ii) water and sports drink intake may positively affect shot accuracy and speed, iii) fluid restriction and fluid intake protocols may affect shot accuracy and speed at different levels according to shot performance level.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

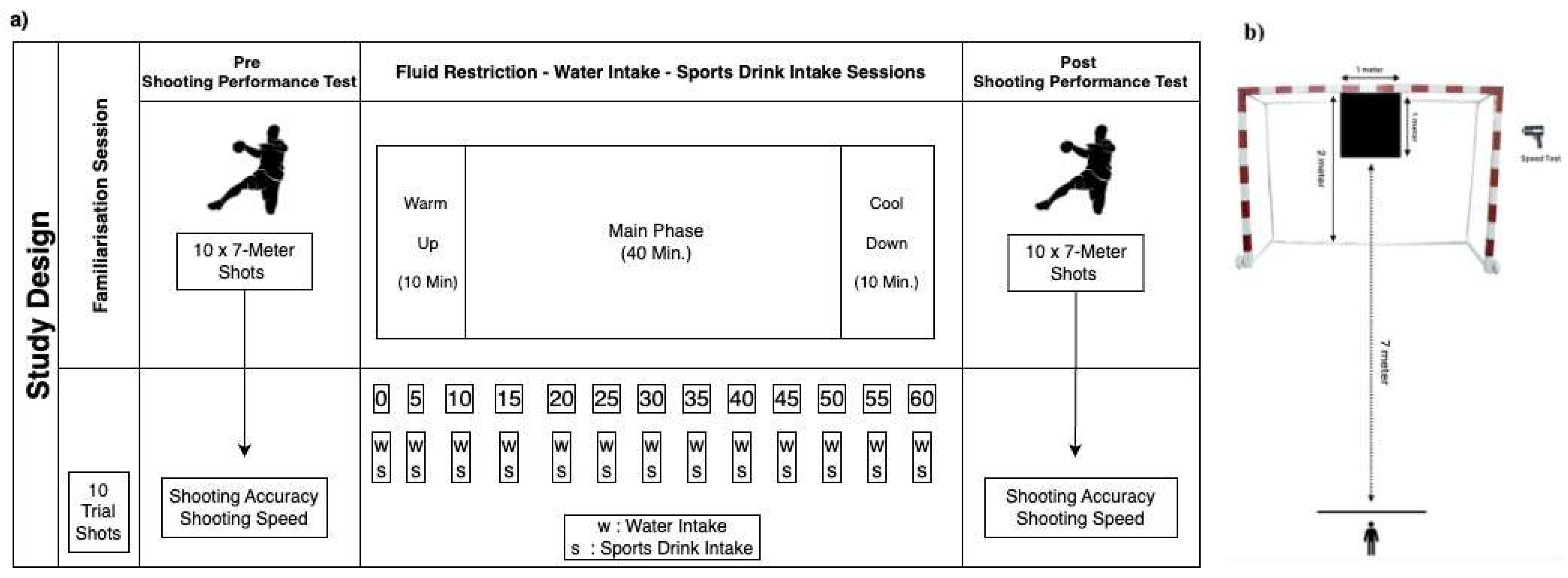

The study was conducted in four sessions (

Figure 1-a) including one familiarisation session and three experimental intervention conditions. In all sessions, temperature and humidity were controlled at 28.8 ± 0.5°C and 45.5% humidity, typical of competitive indoor environments, to ensure ecological validity in simulating match conditions. BM measurements were taken at the beginning of the fluid restriction, water intake, and sports drink intake sessions. After that, a 10- min. The warm-up period and the shooting performance test were started. In this process, the participants were shooting to make 10 shots on the plate hung on the handball goal, while remaining stationary on a 7 m. handball line (

Figure 1-b). Accuracy rate and speed were recorded simultaneously during the shots via the JUGS Gun. After the test, a 60-min. The Handball training program was applied to the participant group. In the water intake and sports drink intake sessions, participants were asked to consume 1% of their BM in five-minute intervals. During the water intake and sports drink intake sessions, participants were asked to consume 1% of their BM in five-minute intervals. Especially for sports drink intake, 5 min intervals were preferred in both conditions to facilitate consumption and reduce potential risks such as sudden increase in blood glucose levels [

18,

19]. The fluid levels that the participants should consume were determined in bottles specially labelled for them and they were warned not to exceed these levels. Immediately after the training session, BM was measured in all conditions and then the shooting performance test was administered again and the session ended. A rest period of at least 48 h. was given between the sessions.

2.2. Participants

The study included 47 healthy adolescent male handball players aged between 13 and 18 years (15.00 ± 1.49 years). The participants who engaged in handball training no less than three days a week, had an average of at least one year of training experience and had not suffered any upper extremity injuries in the earlier six months. The exclusion criteria included having an injury in the last six months [

15]. G-Power 3.1.9.4 software (Germany) was used to calculate the number of participants to be included in the study and to determine the required sample size. The sample size was determined as 45 participants based on an effect size of f = 0.5, an alpha (error) rate of 5%, and a power of 95% [

16,

17], and 47 participants were included by anticipating potential risks. All participants and their families were informed about the study and completed the informed consent form and their voluntary participation in the study was documented. The study was approved by Manisa Celal Bayar University Health Sciences Ethics Committee with a decision dated June 7, 2020, and number 20.487.486/1870. The Declaration of Helsinki guided the conduct of this study.

2.3. Pre-Session Standardisation

Participants were subjected to fluid and food restrictions 2-h. before each session. Hydration level was monitored by subjective method and body mass change because the study contains a precise and standardised temporal transition phase between pre-shooting performance test - handball training - post-shooting performance test and the reflection of fluid intake on biomarkers (urine or blood) is time-dependent [

51] and individualistic [

52]. At the beginning of each session, participants‘ subjective hydration levels were assessed using an analogue scale asking about thirst intensity, with categories ranging from 1 (’not thirsty at all‘) to 3 (’extremely thirsty'

) [

50]

. Standardisation was achieved by fully hydrating before the conditions [

22,

23].

2.4. Familiarisation Session

In the first stage, demographic information was collected after the experimental protocol of the study was explained. Following the anthropometric measurements, the shooting performance test was explained to the participants. After the explanation, the teaching and application of the shooting performance test was carried out by making 10 trial shots to be used in the test. In this section, it was aimed to familiarise the participants with the shooting performance protocol and to reduce possible performance variability in the initial measurements.

2.5. Anthropometric Measurements

The height of the participants was measured by the same person using a tape measure, standing upright barefoot with their backs against a wall, determining the top of their heads, and recorded in centimetres. BM was measured using via Fitsense AR 553 electronic weighing scale and recorded in kilograms (accuracy 0.1 kg) [

24,

27].

2.6. Measurement of Hydration Status

The BM of the participants was measured before and after the training sessions and the formula (post-BM-pre-BM / pre-BM) was used to calculate the degree of dehydration [

28,

29].

2.7. Shooting Performance Test

The chosen shooting performance test is widely validated in handball performance research, allowing for both inter- and intra-subject reliability due to its standardised distance and timing controls [

30,

33]. In the test (

Figure 1b); thne participants have 10 throws from behind the 7-m. line to a 1 m. x 1 m. plastic plate hung in the middle of the handball goal. The participants performed the test with the highest speed and accuracy they could with their dominant hand. The time between the throws was set as 5 seconds for the participant to maintain attention and concentration [

34]. During the throws, the speed of the handball leaving the hand and traveling to the goal was measured with a radar device branded ‘Bushell Velocity Speed Gun’, which can measure speeds between 10-331 km/h and has an accuracy of ±0.8 km/h [

35]. The measurements obtained were recorded in km/hour [

36,

37].

2.9. Handball Training Programme

Participants were subjected to a 60-min. session of low and medium-intensity actions designed by an expert coach. The session included;

-Warm-up (10 min.); low to moderate running, basic passing technique drills + dynamic exercises,

-Main phase (40 min.); technical passing, positional shots, and small-sided games with positional differences,

-Cool down (10 min.); 5 min. running + 5 min. stretching exercises were carried out.

In the main phase, passing and shooting techniques and tactical variations frequently used in the match were preferred.

Water and Sports Drink Intake Process

Participants received water and sports drink supplements at 5-min intervals (1% x body mass = 12 equal parts) during handball training [

3]. In the water intake condition, participants received ‘Natural Water’, commercial water [

38]. The sodium and carbohydrate content in the sports drink was selected to both replenish electrolytes and provide an immediate energy source, as recommended in intermittent sports contexts. The sports drink intake session included 'Isotonic Sports Drink', a commercial sports drink (Powerade) that is rich in water, carbohydrates, and electrolytes. This drink contains 170 kcal/L, 39 g/L carbohydrate (sugar), 0 g fat, 0 g protein, and 1.2 g/L sodium [

3,

39]. The temperature of the commercial water and sports drink was 10-12°C [

49].

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical package program JASP (version 0.16.4). The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to determine the normal distribution of all participants' data (BM, Body Mass Index; (BMI), delta differences, loss rate; LR, shooting accuracy, and shooting speed). It was determined that the data were normally distributed. A paired sample t-test was used to evaluate the differences before and after the training. In addition, an independent t-test was used to compare different groups (body mass, BMI, delta differences, LR, shooting accuracy, and shooting speed). Using Cohen’s d, determined the effect sizes between the data. The significance level was set as less than 0.05 [

40].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics Participants

The demographic information and shooting performance of the 47 participants can be seen in

Table 1. Descriptive statistics indicated no significant differences across groups for age, training experience, height, or body mass, confirming comparable baseline characteristics.

Table 2 presents the changes in the participants' hydration parameters. In the pre and post-measurement values of the fluid restriction sessions, all groups (p:<0.001, Δ:-0.64±0.32, LR-1.01%) there is a decrease. In the LP group, (p:<0.001, Δ:-0.7±0.24, LR:-1.12%) has a change. MP (p:0.65, Δ:-0.13±0.56, LR:-0.71%), but it was not statistically changed. In the HP group, (p:0.005, Δ:-0.69±0.47, LR:-1.03%) there is decrease.

3.2. Hydration Levels

At the pre and post-measurement values of the Water Intake session, all groups (p:<0.001, Δ:-0.23±0.34, LR:-0.36%) there is a statistical decrease. In the LP group, (p:0.003, Δ:-0.19±0.18, LR:-0.30%) has a significant change. MP (p: 0.011,Δ:-0.22±0.42, LR:-0.34%) there is a decrease. In the HP group, (p:0.023, Δ:-0.34±0.33, LR:-0.51%) there is a statistical change.

Pre and post-measurement results regarding the sessions of Sports Drink Intake, in all groups (p:<0.001, Δ:-0.33±0.53, LR:-0.51%) there is a decrease. In the LP group, (p:0.031, Δ:-0.32±0.48, LR:-0.51%) has a change. MP (Δ:-0.32±0.63, LR: -0.50%) decline is statistically. In the HP group, (p:0.001, Δ:-0.39±0.16, LR -0.58%) there is a decrease.

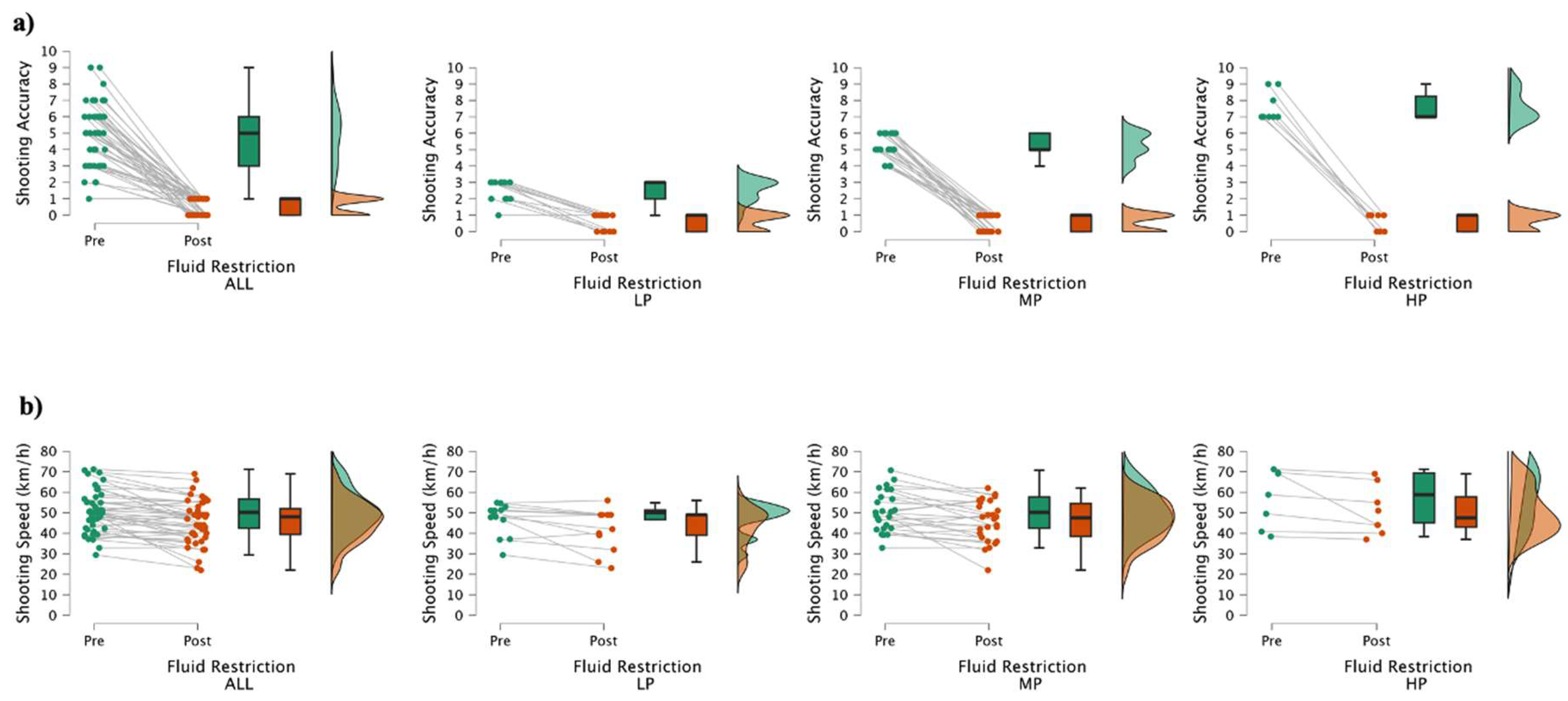

The changes for shooting accuracy parameters of the participants are given in

Table 3. In the Fluid restriction session, in pre and post-measurement values, all groups (p:<0.001, Cohen’s:2.194) there is a decrease. In the LP group, (p:<0.001 Cohen’s:2.532) there is a decline. MP (p:<0.001 Cohen’s:4.471), not decline. In the HP group (p:<0.001 Cohen’s:6.548) there is a decrease.

3.3. Shooting Accuracy Test

For the Water Intake session, in pre and post-measurements, all groups (p:0.502, Cohen’s:-0.099) there is a numerical increase. In the LP group, (p:0.057, Cohen’s:-0.391) there non-increase. MP (p:<0.001 Cohen’s:4.471). The HP group, (p:0.004, Cohen’s:6.548) there is an increase.

The pre and post-measurement values of the Sport Drink Intake session, all groups (p:0.09, Cohen's:0.167), there is an increase. In the LP group, (p:0.766, Cohen’s:0.297) there is a non-statistical increase. MP (p:0.045, Cohen’s:4.471) was a decrease. In the HP group, (p:0.009, Cohen’s:0.388) there is an increase (

Figure 2-a.).

The change in the shooting speed parameters of the participants is given in

Table 4. In the Fluid restriction session, the pre and post-measurements of all groups (p:<0.001, Cohen’s:0.551) there is a decrease. In the LP group, (p:0.019 Cohen’s:0.754) there is a decrease. MP (p:0.009 Cohen’s:0.557) were a reduction. In the HP group, (p:0.076 Cohen’s: 0.073) there is a decrease.

3.4. Shooting Speed Test

Throughout the Water Intake session, pre and post-measurement values, all groups (p:0.821, Cohen’s:0.033) there was a numerical decrease. In the LP group, (p:0.191, Cohen’s:0.384) there is a non-significant decrease. MP (p:0.851, Cohen’s:0.037), were non-statistically decreased. In the HP group, (p:0.004, Cohen’s:6.548) there is an increase.

The pre and post-measurement values of the Sports Drink Intake session, all groups (p:3.53±1.50, p: 0.024, Cohen’s:-0.340) there is an increase. In the LP group, (p:0.075, Cohen’s:0.540) there is a numerical increase. MP (p:0.023 Cohen’s:0.477) was an increase. In the HP group, (p:0.630, Cohen’s:0.178) there is a numerical increase (

Figure 2-b.).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the changes in shooting performance and speed of adolescent handball players under fluid restriction and different fluid intake conditions. The main findings of the study were i) fluid restriction during 60-min. of handball training negatively affected shooting accuracy and speed in all adolescent handball players associated with hypohydration (1%), ii) water intake protected shooting accuracy and speed performance, and iii) sports drink intake improved shooting accuracy and speed performance.

Fluid restriction had a negative effect on the post-session performance of all participants in shooting accuracy (p:<0.001) and shooting speed (p:<0.001). When the shooting accuracy values were declining in terms of the groups, it was seen that it was affected at the level of HP (p:<0.001), MP (p:<0.001), and LP (p:<0.001), respectively. In shooting speed values, LP (p:0.019), MP (p:0.009), and HP (p:0.076) were found to be affected. In a study conducted on sub-elite male basketball players, shooting accuracy levels were evaluated under fluid restriction and water intake conditions during 40-min. moderate-intensity training period, no difference in shooting performance was observed between conditions [

5]. Devlin et al. In sub-elite cricketers evaluated shooting performance under fluid restriction and fluid intake conditions induced by ~1-h. intermittent exercise. As a result, they reported gradual deterioration in shooting accuracy in the fluid restriction condition [

41]. Baker et al., sub-elite basketball players investigated the effects of fluid restriction on shooting performance in basketball. In the study, the athletes performed 3-h. intermittent walking exercise on a treadmill followed by free shootings from the foul line. As a result of the study, they found that the participants's shooting accuracy rate deteriorated under the hypohydration condition [

42]. The results of our study coincide with the information reported in the literature regarding adult athletes. In particular, the process we proceeded in common with the studies is that fluid restriction has a detrimental effect on shooting accuracy and speed. This suggests that the participants experienced additional stress due to fluid restriction in addition to the stress they were already experiencing due to exercise. In addition, adolescent athletes are known to excessively breathe and sweat due to their metabolic levels. This may affect the rate of fluid loss more negatively. Therefore, the handball training caused 1% hypohydration in all participants. Hypohydration is known to cause cognitive and motor coordination problems. Shooting accuracy and speed are closely related to cognitive and motor characteristics such as reaction time, visuomotor tracking, timing, and intermuscular coordination [

43]. Hypohydration has been shown to impair neuromuscular coordination, which is integral to accuracy in shooting sports, especially under the cognitive load imposed by the fast-paced demands of handball [

48]. In our study, hypohydration may have affected the shooting performance of adolescent athletes with little training experience by impairing the communication between the parts. Repeated shots in the throwing test protocol also revealed more clearly the potential for low conditioned adolescent handball players to be affected by the restriction (LP shooting speed p:0.075). With this information, it was thought that higher-order associations could explain the effects of this impairment.

The current study revealed that there was no decline in shooting accuracy (p:0.502) and shooting speed performance (p:0.821) among all participants at the water intake session. Furthermore, the shooting accuracy rate considerably improved in the HP group (p:0.004). Upon analysing the shooting accuracy values of the other groups, it was determined that the MP group had p:0.918 and Cohen’s value of -0.391. The LP group had a p:0.057 and a Cohen’s value of -0.029. The HP group had a Cohen’s value of -0.417. The LP group had a Cohen’s value of 0.384. The MP group had a Cohen’s value of 0.037. When the literature was examined, it was reported that water intake (as much as the BM lost) after each period of a 40-min. low-intensity basketball competition with national-level female basketball players improved the number of shootings by 5.3±2.8% and the overall shooting accuracy rate by 30-35%[

44]. In the Burke et al. study, a 2-h. simulated tennis competition was performed with tennis athletes. During the experiment, one group had a regular water intake of 505 millilitres. while the other group was subjected to fluid restriction. After the competition, a shooting performance test consisting of 50 shots was applied. As a result, the hit rate in the water intake condition was 49.45%, while the rate in the fluid restriction condition was 48.65% [

9,

45]. In adolescent athletes, electrolyte losses, especially sodium, occur at a high sweating rate independent of environmental conditions (temperature, humidity). The potential of these losses to decrease performance is known [

46]. In the handball training protocol applied in our study, intermittent water intake equal to BM loss protected shooting performance. The significant improvement in the HP group and the preserved performance in the other groups suggest that in this training protocol, shooting performance parameters are less affected by water intake, possibly slowing the deterioration of fluid-electrolyte balance.

The current study showed that both shooting accuracy (p:0.09) and shooting velocity (p:0.024) increased in all participants during the sports drink session. In the intergroup evaluation, it was found that the HP (p:0.042) and MP (p:0.045) groups improved, while the performance was maintained in the LP group and there was no significant change. In the shooting speed values, it was concluded that there was a significant improvement in the MP group (p:0.23), while no significant change occurred in the LP (p:0.075) and HP (p:0.630) groups. In the literature related to adolescent and late adolescent athletes; Carvalho et al. examined the effects of 90-min. training sessions performed under conditions of fluid loss, water intake (3.8 mg/L sodium), and sports drink (7.2% sugar, 0.8% maltodextrin, and 510 mg/L sodium) intake on a basketball shooting (2 and 3-point shootings and free shooting) performance [

3]. As a result of the study, it was reported that 2-point (55.0 ± 20.2%), 3-point (36.7 ± 19.7%), and free shooting (59.2 ± 22.8%) performances of adolescent basketball players(14.8 ± 0.45 years) were impaired in the fluid restriction condition. In the water intake condition, improvements were observed in 2-point (60.8 ± 12.4%), 3-point (37.5 ± 16.0%) and free shooting (62.5 ± 20.1%) values. However, the highest improvement in 2-point (60.0 ± 16.5 %), 3-point (42.5 ± 16.0 %) and free shooting (65.8 ± 20.2 %) values was obtained in the sports drink intake condition [

47]. In the other study, adolescent basketball players were subjected to a fluid restriction condition and given a sports drink with 6% carbohydrate content in the other condition during a 2-hour intermittent exercise session. As a result, while the free shooting accuracy percentage was 60±8% in the sports drink intake condition, this rate decreased to 45±9% in the fluid restriction condition. Baker et al. performed a 3-h. intermittent treadmill exercise in sub-elite basketball players (17±28 years) under fluid restriction and sports drink (0% carbohydrate and 18% sodium) intake conditions. Free shooting performance was evaluated immediately after the exercise [

44]. As a result of the study, while the hit rate was 86±6% in the sports drink intake condition, this rate was found to be 83±3% in the fluid restriction condition. Considering the information presented, it is seen that the positive results we obtained are highly compatible with the literature.

The best of our knowledge, this is the first study specific to adolescent handball athletes conducted with this research design. The carbohydrates and electrolytes in the sports drink may have a positive effect on handball shooting accuracy and shooting speed by improving the mechanisms related to cognitive and motor coordination, thus indirectly increasing shooting performance. Sports drink supplementation in an intermittent model in adolescent handball players has a high potential to positively affect shooting performance parameters.

5. Limitation

Performance fluctuations in shooting accuracy and speed values occurred in all sessions of the participants. Previous research has shown that fluctuations in accuracy and speed values in handball shooting performance are affected by training experience [

34]. The fact that possible accuracy decreases that may occur due to the increase in shooting speed was not observed in our study eliminates the possibility that speed fluctuations are caused by focusing on accuracy. On the other hand, the subjective hydration questionnaire we used in this study, although practical, may be prone to bias and lacks specificity. Future studies may consider including measures of urine osmolality or specific gravity to objectively monitor hydration status. Discuss possible confounding variables such as individual variability in sweat rates or previous hydration levels: Uncontrolled variables such as individual sweat rates and previous hydration status may introduce variability in results. A standardised pre-test hydration protocol or individual sweat rate monitoring may reduce these factors in future research. Finally, since our research was conducted in a controlled indoor environment, the findings may not be fully generalised to outdoor conditions where temperature and humidity are variable.

6. Conclusions

The findings of the study show that hypohydration of 1% negatively affects shooting performance in adolescent handball players, while intermittent water intake in the amount they lose protects performance. On the other hand, it was found that performance increased with commercial sports drink intake. It was also observed that this benefit obtained from water and sports drink intake was different according to the shooting performance level (HP vs LP) of adolescent handball players. Therefore, these findings revealed that hydration is a key factor in the shooting performance of adolescent handball players.

Based on the findings, adolescent handball players should be encouraged to consume small amounts of sports drinks during training and matches, especially during high-intensity periods, to maintain shooting performance. It is also recommended that handball field practitioners, nutritionists, coaches and athletes utilise the fluid intake protocols implemented in this study to maintain and improve shooting performance.

Author Contributions

EU: EG designed this study . EU, EM, EG researched data. EU, EM analysed the data. EU,EM,EG, NRS and CSB interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. CSB, EG supervised the study. All authors contributed to the review and revision of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed according to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Manisa Celal Bayar University Health Sciences (Approval Date/Number: 2020–07/20.487.486/187). All participants were agreed to take part in the study and provided informed written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability

All collected data in the current study are available after the permission of the whole writer. Written proposals can be addressed to the corresponding authors for appropriateness of use.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| BM |

Body Mass |

| Min. |

Minute |

| H |

Hours |

| % |

Rate |

References

- F. Meyer, Z. Szygula, And B. Wilk, Fluid Balance, Hydration And Athletic Performance. Crc Press Is An Imprint Of Taylor & Francis Group, 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Casa, P. M. Clarkson, And W. O. Roberts, “American College Of Sports Medicine Roundtable On Hydration And Physical Activity: Consensus Statements,” 2005. [Online]. Available: Http://Journals.Lww.Com/Acsm-Csmr. [CrossRef]

- P. Carvalho, B. Oliveira, R. Barros, P. Padrão, P. Moreira, And V. H. Teixeira, “Impact Of Fluid Restriction And Ad Libitum Water Intake Or An 8% Carbohydrate-Electrolyte Beverage On Skill Performance Of Elite Adolescent Basketball Players,” 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. Chryssanthopoulos, “Body Fluid Loss During Four Consecutive Beach Handball Matches In High Humidity And Environmental Temperatures,” 2007. [Online]. Available: https://www.Researchgate.Net/Publication/302878293.

- R. H. Hoffman Stavsky B Falk And I. R. Hornan H Stavsky, “The Effect Of Water Restriction On Anaerobic Power And Vertical Jumping Height In Basketball Players,” 1995. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Davey, R. D. Thorpe, And C. Williams, “Fatigue Decreases Skilled Tennis Performance,” J Sports Sci, Vol. 20, No. 4, Pp. 311–318, 2002 . [CrossRef]

- L. H. Devlin, S. F. Fraser, N. S. Barras, And J. A. Hawley, “Moderate Levels Of Hypohydration Impairs Bowling Accuracy But Not Bowling Velocity In Skilled Cricket Players. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Dougherty, L. B. Baker, M. Chow, And W. L. Kenney, “Two Percent Dehydration Impairs And Six Percent Carbohydrate Drink Improves Boys Basketball Skills,” Med Sci Sports Exerc, Vol. 38, No. 9, Pp. 1650–1658, Sep. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Burke Er. And Ekblom B., “Influence Of Fluid Ingestion And Dehydration On Precision And Endurance Performance In Tennis,” Curr Top Sports Med., Vol. 379, No. 88, 1984. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Deshayes, T. Pancrate, And E. D. B. Goulet, “Impact Of Dehydration On Perceived Exertion During Endurance Exercise: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis,” J Exerc Sci Fit, Vol. 20, No. 3, Pp. 224–235, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. F. Coyle, “Fluid And Fuel Intake During Exercise,” In Journal Of Sports Sciences, Jan. 2004, Pp. 39–55. Doi: 10.1080/0264041031000140545. [CrossRef]

- K. Barnes And L. Baker, “Hydration And Team Sport Cognitive Function, Technical Skill And Physical Performance,” Sports Science Exchange, Vol. 29, No. 210, Pp. 1–5, 2021.

- Ehf, “European Handball Federation,” https://www.Eurohandball.Com/.

- Sport Accord, “Sport Accord,” https://www.Sportaccord.Sport/.

- C. M. Patino And J. C. Ferreira, “Inclusion And Exclusion Criteria In Research Studies: Definitions And Why They Matter,” Mar. 01, 2018, Sociedade Brasileira De Pneumologia E Tisiologia. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Lahey, R. G. Downey, And F. E. Saal, “Intraclass Correlations: There’s More There Than Meets The Eye,” 1983. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Walter, M. Eliasziw, A. Donner, And J. P. The, “Sample Size And Optimal Designs For Reliability Studies,” 1998. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Armstrong, “Rehydration During Endurance Exercise: Challenges, Research, Options, Methods,” Nutrients, Vol. 13, No. 3, Pp. 1–22, 2021, Doi: 10.3390/Nu13030887. [CrossRef]

- D. Pizarro, G. Posada, N. Villavicencio, E. Mohs, And M. M. Levine, “Oral Rehydration In Hypernatremic And Hyponatremic Diarrheal Dehydration: Treatment With Oral Glucose/Electrolyte Solution,” American Journal Of Diseases Of Children, Vol. 137, No. 8, Pp. 730–734, 1983. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Cheuvront And R. W. Kenefick, “Dehydration: Physiology, Assessment, And Performance Effects,” Compr Physiol, Vol. 4, No. 1, Pp. 257–285, 2014, Doi: 10.1002/Cphy.C130017. [CrossRef]

- G. Travers, D. Nichols, N. Riding, J. González-Alonso, And J. D. Périard, “Heat Acclimation With Controlled Heart Rate: Influence Of Hydration Status,” Med Sci Sports Exerc, Vol. 52, No. 8, Pp. 1815–1824, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Eith, C. R. Haggard, D. M. Emerson, And S. W. Yeargin, “Practices Of Athletic Trainers Using Weight Charts To Determine Hydration Status And Fluid-Intervention Strategies,” J Athl Train, Vol. 56, No. 1, Pp. 64–70, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Zavvos, P. Miliotis, D. Stergiopoulos, M. Koskolou, And N. Geladas, “The Effect Of Caffeine Intake On Body Fluids Replacement After Exercise-Induced Dehydration,” Nutr Today, Vol. 55, No. 6, Pp. 288–293, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Ehlert And P. B. Wilson, “The Associations Between Body Mass Index, Estimated Lean Body Mass, And Urinary Hydration Markers At The Population Level,” Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci, Vol. 25, No. 2, Pp. 163–170, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Inese Pontaga And Janis Zidens, “Estimation Of Body Mass Index In Team Sports Athletes,” Lase Journal Of Sport Science, Vol. 2, No. 2, Pp. 33–44, 2011, [Online]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260385568.

- J. Walsh, I. T. Heazlewood, And M. Climstein, “Body Mass Index In Master Athletes: Review Of The Literature,” J Lifestyle Med, Vol. 8, No. 2, Pp. 79–98, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Arzum, “Fitsense Ar 553 Vücut Analiz Baskülü,” Https://Destek.Arzum.Com.Tr/Manuals/Arzum-Fitsense-Vucut-Analiz-Baskulu-Ar553.Pdf.

- M. P. Funnell, J. Moss, D. R. Brown, S. A. Mears, And L. J. James, “Perceived Dehydration Impairs Endurance Cycling Performance In The Heat In Active Males,” Physiol Behav, P. 114462, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Shirreffs, S. J. Merson, S. M. Fraser, And D. T. Archer, “The Effects Of Fluid Restriction On Hydration Status And Subjective Feelings In Man,” British Journal Of Nutrition, Vol. 91, No. 6, Pp. 951–958, Jun. 2004. [CrossRef]

- L. Gomboș, A. A. Gherman, A. Pătrașcu, And P. Radu, “Postural Balance And 7-Meter Throw’s Accuracy In Handball,” Timisoara Physical Education And Rehabilitation Journal, Vol. 10, No. 19, Pp. 103–108, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Terzis, G. Karampatsos, And G. Georgiadis, “Neuromuscular Control And Performance In Shot-Put Athletes,” Journal Of Sports Medicine And Physical Fitness, Vol. 47, No. 3, Pp. 284–290, 2007.

- A. G. G. Thomas A. Kyriazis, Gerasimos Terzis, Konstantinos Boudolos, “Muscular Power, Neuromuscular Activation, And Performance In Shot Put Athletes At Preseason And At Competition Period,” Vol. 23, No. 6, Pp. 1773–1779, 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. A. García, R. Menayo, And P. Del Val, “Speed-Accuracy Trade-Off In 7-Meter Throw In Handball With Real Constraints: Goalkeeper And The Level Of Expertise,” Journal Of Physical Education And Sport, Vol. 17, No. 2, Pp. 879–883, Jun. 2017, Doi: 10.7752/Jpes.2017.02134. [CrossRef]

- R. Van And G. Ettema, “A Comparison Between Novices And Experts O F The Velocity-Accuracy Trade-Off I N Overarm Throwing ’,” O Perceptual And Motor Skills, Vol. 103, Pp. 503–514, 2006 .

- R. Van Den Tillaar, M. Ma´, And M. C. Marques, “Reliability Of Seated And Standing Throwing Velocity Using Differently Weighted Medicine Balls’’. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Crotin And D. K. Ramsey, “An Exploratory Investigation Evaluating The Impact Of Fatigue-Induced Stride Length Compensations On Ankle Biomechanics Among Skilled Baseball Pitchers,” Life, Vol. 13, No. 4, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. B. Zhang, Q. Jiang, And A. Li, “The Impact Of Resistance-Based Training Programs On Throwing Performance And Throwing-Related Injuries In Baseball Players: A Systematic Review,” Heliyon, Vol. 9, No. 12, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Coca-Cola Tr, “Damla Doğal Kaynak Suyu,” Coca-Cola Tr. https://www.coca-cola.com/tr/tr/brands/damla.

- Coca-Cola Tr, “Powerade - İzotonik Spor İçecekleri ,” Coca-Cola Tr. https://www.coca-cola.com/tr/tr/brands/powerade.

- J. Love Et Al., “Jasp: Graphical Statistical Software For Common Statistical Designs,” J Stat Softw, Vol. 88, No. 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. H. Devlin, S. F. Fraser, N. S. Barras, And J. A. Hawley, “Moderate Levels Of Hypohydration Impairs Bowling Accuracy But Not Bowling Velocity In Skilled Cricket Players”. [CrossRef]

- L. B. Baker, K. A. Dougherty, M. Chow, And W. L. Kenney, “Progressive Dehydration Causes A Progressive Decline In Basketball Skill Performance,” Med Sci Sports Exerc, Vol. 39, No. 7, Pp. 1114–1123, Jul. 2007. [CrossRef]

- F. Meyer, K. A. Volterman, B. W. Timmons, And B. Wilk, “Fluid Balance And Dehydration In The Young Athlete: Assessment Considerations And Effects On Health And Performance,” Am J Lifestyle Med, Vol. 6, No. 6, Pp. 489–501, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Brandenburg And M. Gaetz, “Fluid Balance Of Elite Female Basketball Players Before And During Game Play,” 2012. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Burke, “Nutritional Approaches To Counter Performance Constraints In High-Level Sports Competition,” Exp Physiol, Vol. 106, No. 12, Pp. 2304–2323, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Petrie, E. A. Stover, And C. A. Horswill, “Nutritional Concerns For The Child And Adolescent Competitor,” Jul. 2004. [CrossRef]

- D. Dinu, E. Tiollier, E. Leguy, M. Jacquet, J. Slawinski, And J. Louis, “Does Dehydration Alter The Success Rate And Technique Of Three-Point Shooting In Elite Basketball?” Mdpi Ag, Feb. 2018, P. 202. [CrossRef]

- Distefano LJ, Casa DJ, Vansumeren MM, et al. Hypohydration and hyperthermia impair neuromuscular control after exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(6):1166-1173. [CrossRef]

- Millard-Stafford M, Snow TK, Jones ML, Suh H. The Beverage Hydration Index: Influence of Electrolytes, Carbohydrate and Protein. Nutrients. 2021;13(9):2933. Published 2021 Aug 25. [CrossRef]

- Wilk B, Timmons BW, Bar-Or O. Voluntary fluid intake, hydration status, and aerobic performance of adolescent athletes in the heat. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35(6):834-841. [CrossRef]

- Popowski LA, Oppliger RA, Patrick Lambert G, Johnson RF, Kim Johnson A, Gisolf CV. Blood and urinary measures of hydration status during progressive acute dehydration. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(5):747-753. [CrossRef]

- Perrier, E., Demazières, A., Girard, N. et al. Circadian variation and responsiveness of hydration biomarkers to changes in daily water intake. Eur J Appl Physiol 113, 2143–2151 (2013). [CrossRef]

- H. S. Liu, C. C. Liu, Y. J. Shiu, P. T. Lan, A. Y. Wang, and C. H. Chiu, “Caffeinated Chewing Gum Improves Basketball Shooting Accuracy and Physical Performance Indicators of Trained Basketball Players: A Double-Blind Crossover Trial,” Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 9, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).