Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

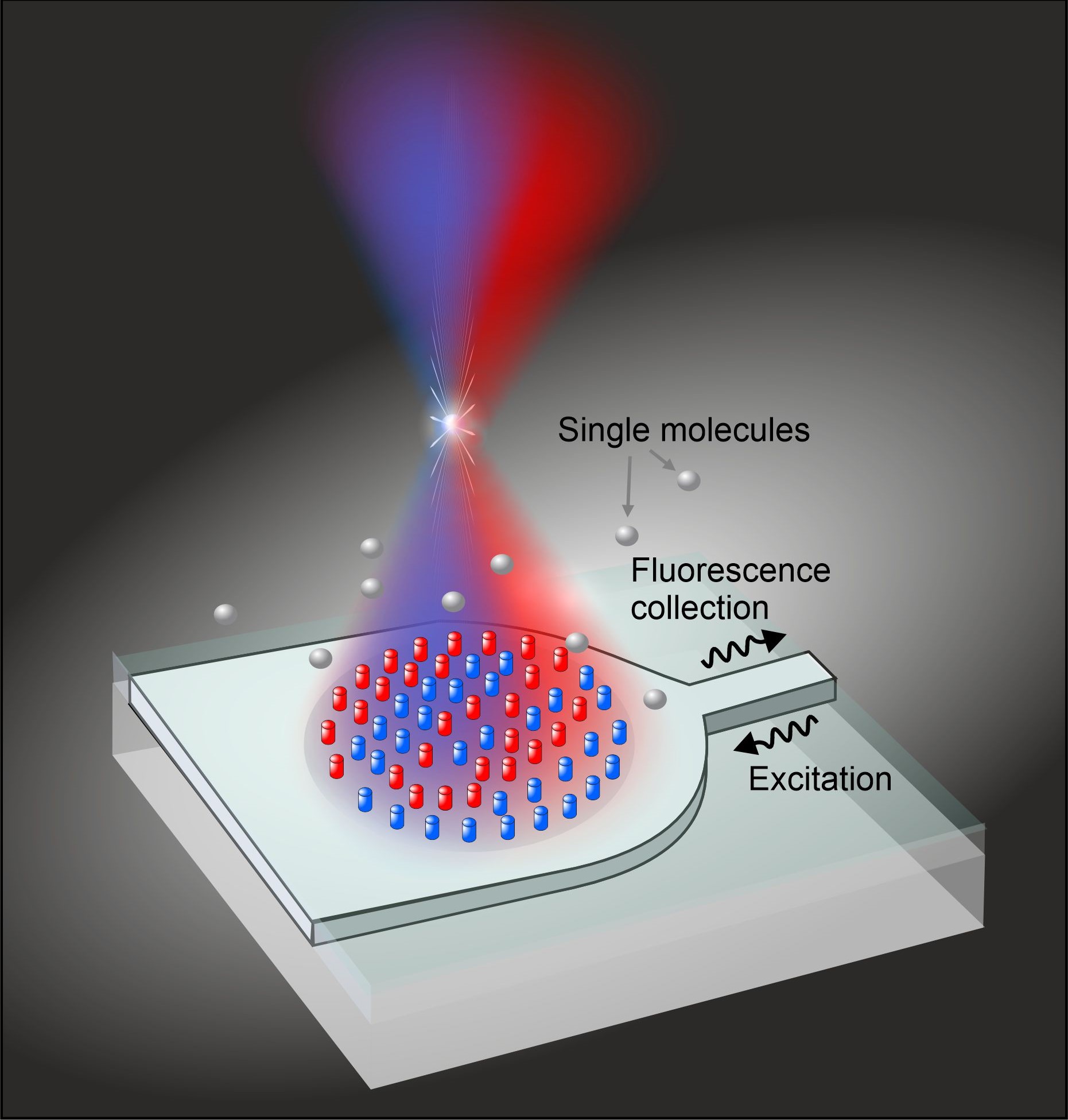

1. Introduction

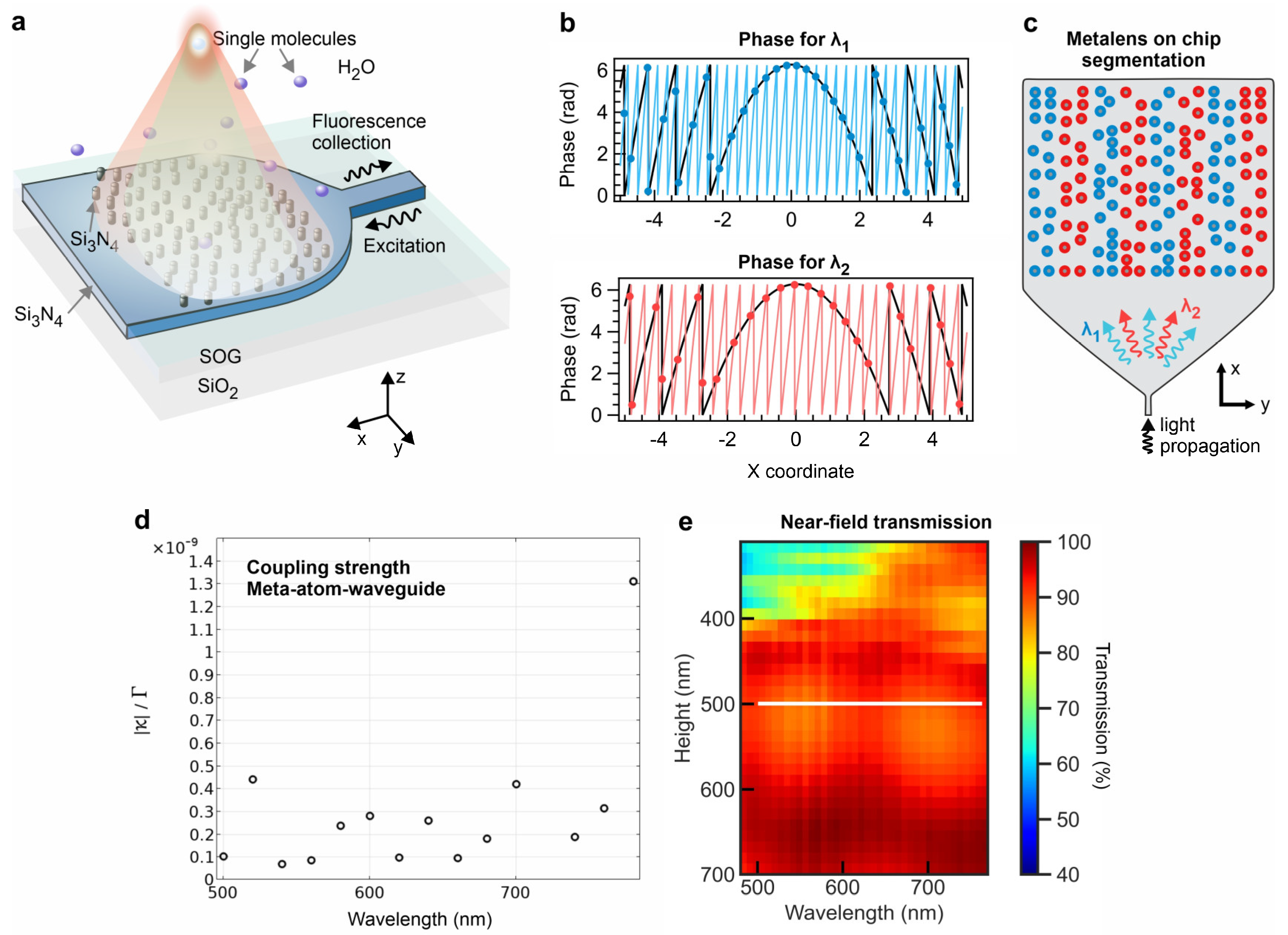

2. Materials and Methods

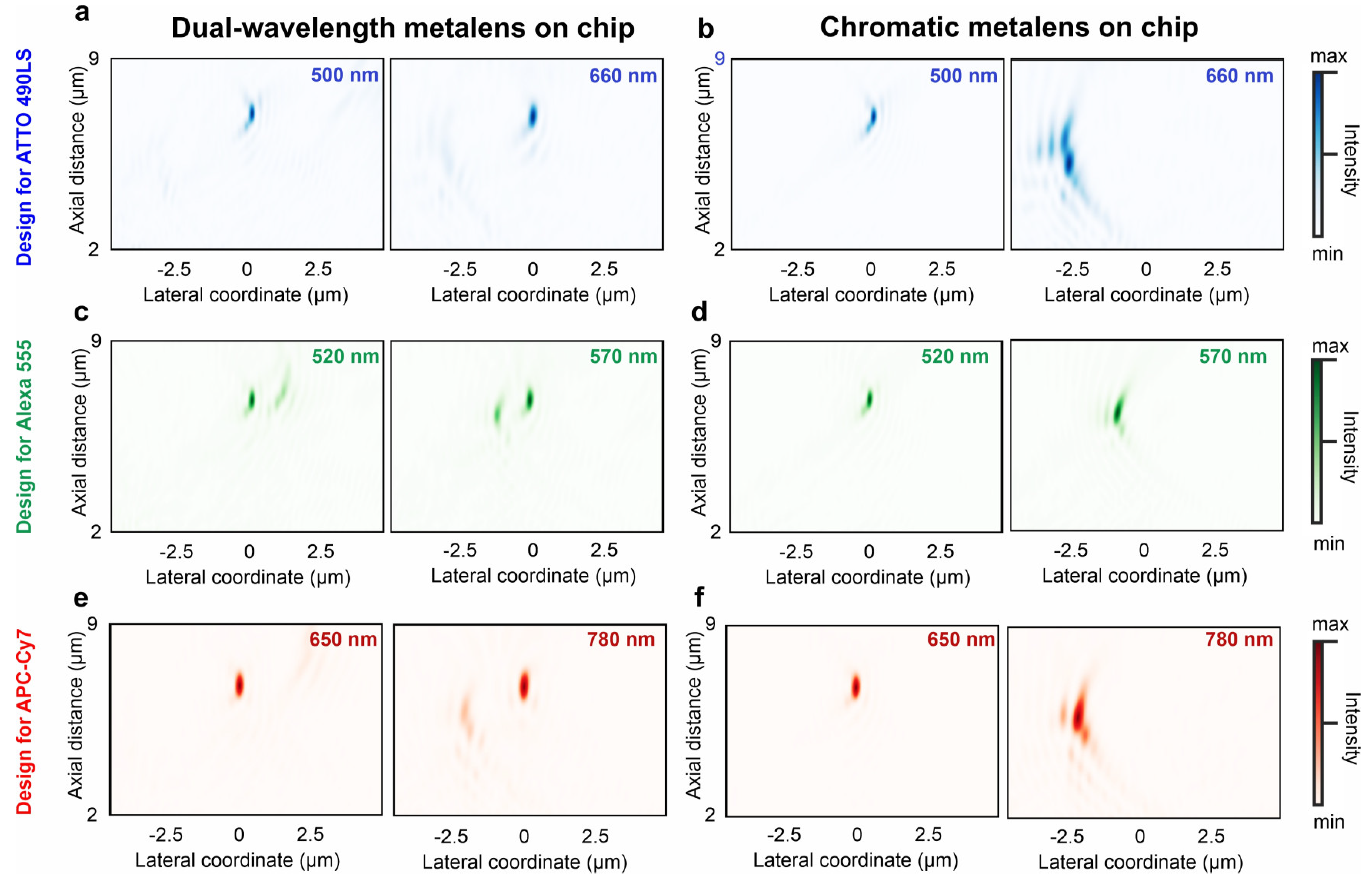

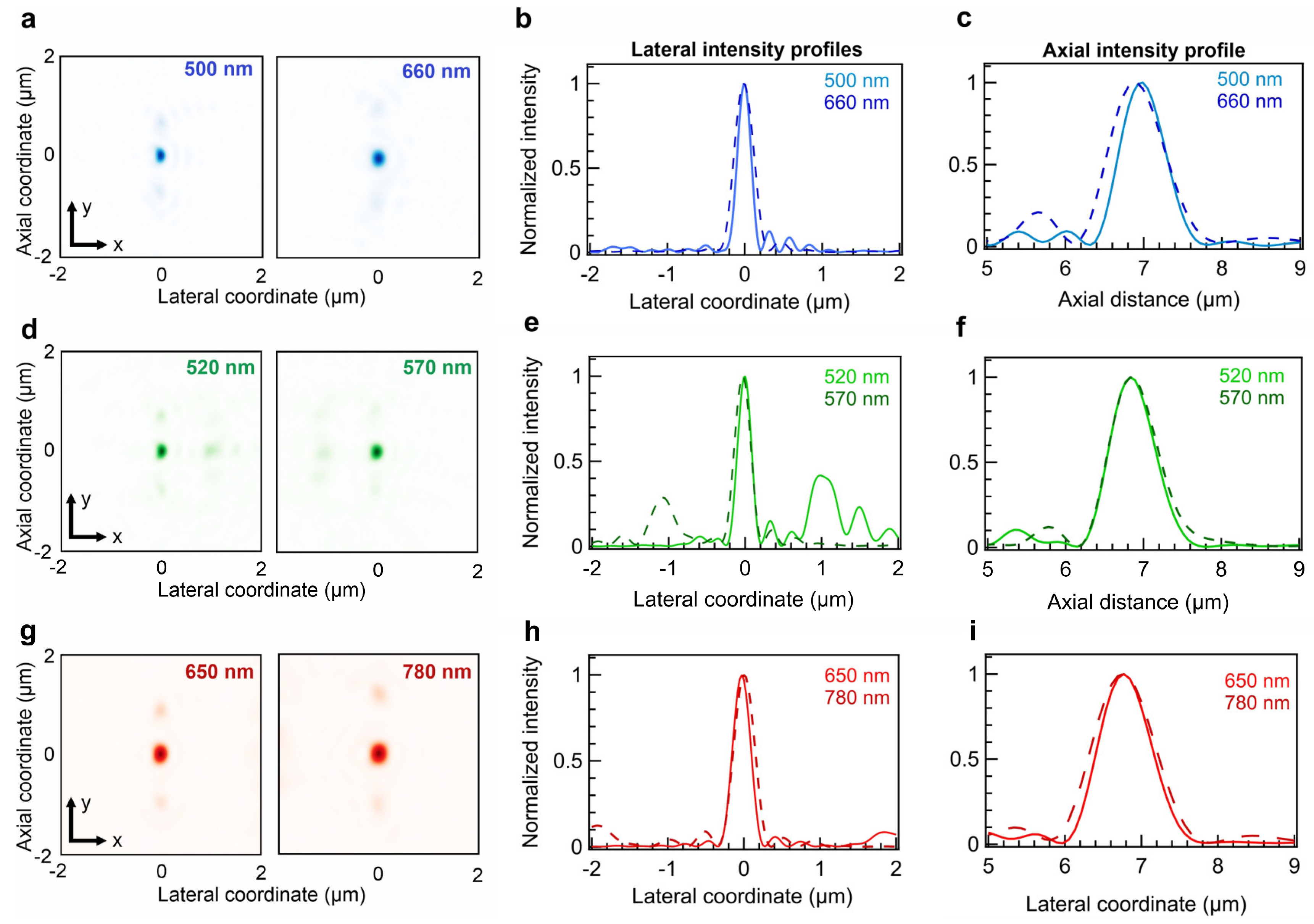

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barkai, E.; Jung, Y.; Silbey, R. THEORY OF SINGLE-MOLECULE SPECTROSCOPY: Beyond the Ensemble Average. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2004, 55, 457–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchia, E.; Torricelli, F.; Caputo, M.; Sarcina, L.; Scandurra, C.; Bollella, P.; Catacchio, M.; Piscitelli, M.; Di Franco, C.; Scamarcio, G.; et al. Point-Of-Care Ultra-Portable Single-Molecule Bioassays for One-Health. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, 2309705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Z.; Shang, Y.; Kang, S.H.; Lin, J.-M. Single-Molecule Detection-Based Super-Resolution Imaging in Single-Cell Analysis: Inspiring Progress and Future Prospects. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023, 117255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.; Torres, R.; Levene, M.J. Integrated Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy Device for Point-of-Care Clinical Applications. Biomedical Optics Express 2013, 4, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.W.; Bauer, A.; Polinkovsky, M.E.; Bhumkar, A.; Hunter, D.J.; Gaus, K.; Sierecki, E.; Gambin, Y. Single-Molecule Detection on a Portable 3D-Printed Microscope. Nature communications 2019, 10, 5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofymchuk, K.; Glembockyte, V.; Grabenhorst, L.; Steiner, F.; Vietz, C.; Close, C.; Pfeiffer, M.; Richter, L.; Schütte, M.L.; Selbach, F.; et al. Addressable Nanoantennas with Cleared Hotspots for Single-Molecule Detection on a Portable Smartphone Microscope. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Dolci, M.; Zijlstra, P. Single-Molecule Optical Biosensing: Recent Advances and Future Challenges. ACS Phys. Chem Au 2023, 3, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Capasso, F. Flat Optics with Designer Metasurfaces. Nature materials 2014, 13, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani, S.; Jacob, Z. All-Dielectric Metamaterials. Nature nanotechnology 2016, 11, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genevet, P.; Capasso, F.; Aieta, F.; Khorasaninejad, M.; Devlin, R. Recent Advances in Planar Optics: From Plasmonic to Dielectric Metasurfaces. Optica 2017, 4, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasaninejad, M.; Chen, W.T.; Devlin, R.C.; Oh, J.; Zhu, A.Y.; Capasso, F. Metalenses at Visible Wavelengths: Diffraction-Limited Focusing and Subwavelength Resolution Imaging. Science 2016, 352, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorasaninejad, M.; Capasso, F. Metalenses: Versatile Multifunctional Photonic Components. Science 2017, 358, eaam8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.Y.; Chen, W.-T.; Khorasaninejad, M.; Oh, J.; Zaidi, A.; Mishra, I.; Devlin, R.C.; Capasso, F. Ultra-Compact Visible Chiral Spectrometer with Meta-Lenses. Apl Photonics 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Divitt, S.; Fan, Q.; Zhu, W.; Agrawal, A.; Lu, Y.; Xu, T.; Lezec, H.J. Low-Loss Metasurface Optics down to the Deep Ultraviolet Region. Light: Science & Applications 2020, 9, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Ossiander, M.; Meretska, M.L.; Hampel, H.K.; Lim, S.W.D.; Knefz, N.; Jauk, T.; Capasso, F.; Schultze, M. Extreme Ultraviolet Metalens by Vacuum Guiding. Science 2023, 380, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Kravchenko, I.I.; Wang, H.; Nolen, J.R.; Gu, G.; Valentine, J. Multilayer Noninteracting Dielectric Metasurfaces for Multiwavelength Metaoptics. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 7529–7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Tian, Y.; Ma, W.; Gong, X.; Yu, J.; Zhao, G.; Yu, X. Transmissive Terahertz Metalens with Full Phase Control Based on a Dielectric Metasurface. Optics letters 2017, 42, 4494–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Ye, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wu, W.; Li, B.; Zheng, W. Dielectric Metalenses at Long-Wave Infrared Wavelengths: Multiplexing and Spectroscope. Results in Physics 2020, 18, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Park, H.; Yoon, H.; Kim, I. Advanced Biological Imaging Techniques Based on Metasurfaces. Opto-Electronic Advances, 2024; 240122–1. [Google Scholar]

- Yesilkoy, F. Optical Interrogation Techniques for Nanophotonic Biochemical Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Kim, C.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, J.; Choi, S.; Han, W.; Kim, J.; Lee, B. Dielectric Metalens: Properties and Three-Dimensional Imaging Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.-Y.; Fang, S.-L.; Lin, Y.-S.; Huang, W.-H.; Shieh, J.-M.; Yu, P.; Chang, Y.-C. Integrated Metasurfaces on Silicon Photonics for Emission Shaping and Holographic Projection. 2022, 11, 4687–4695. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Overvig, A.C.; Xu, Y.; Malek, S.C.; Tsai, C.-C.; Alù, A.; Yu, N. Leaky-Wave Metasurfaces for Integrated Photonics. Nature Nanotechnology 2023, 18, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ding, Y.; Chen, X.; Duan, Y.; Ni, X. Molding Free-Space Light with Guided Wave–Driven Metasurfaces. Science Advances, 6, eabb4142. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wan, S.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tang, J.; Li, Z. Immersive Tuning the Guided Waves for Multifunctional On-Chip Metaoptics. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2022, 16, 2200127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Wang, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhu, S.; Li, T. Manipulating Guided Wave Radiation with Integrated Geometric Metasurface. Nanophotonics 2022, 11, 1923–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, X.; Duan, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Chang, S.; Guo, X.; Ni, X. Metasurface-Dressed Two-Dimensional on-Chip Waveguide for Free-Space Light Field Manipulation. ACS Photonics 2022, 9, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qiao, Y.; Deng, R.; Shi, Y.; Li, Z. On-Chip Direction-Multiplexed Meta-Optics for High-Capacity 3D Holography. Adv Funct Materials 2024, 34, 2312705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K.K.; Bruzewicz, C.D.; McConnell, R.; Ram, R.J.; Sage, J.M.; Chiaverini, J. Integrated Optical Addressing of an Ion Qubit. Nature Nanotechnology 2016, 11, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, S.; Sorokina, A.; Grimpe, C.-F.; Du, G.; Gehrmann, P.; Jordan, E.; Mehlstäubler, T.; Kroker, S. Chip Integrated Photonics for Ion Based Quantum Computing. In Proceedings of the EPJ Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences, 2022; Vol. 266; p. 13032. [Google Scholar]

- Sonehara, T.; Anazawa, T.; Uchida, K. Improvement of Biomolecule Quantification Precision and Use of a Single-Element Aspheric Objective Lens in Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. Analytical chemistry 2006, 78, 8395–8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.T.; Zhu, A.Y.; Sanjeev, V.; Khorasaninejad, M.; Shi, Z.; Lee, E.; Capasso, F. A Broadband Achromatic Metalens for Focusing and Imaging in the Visible. Nature Nanotechnology 2018, 13, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.J.; Su, V.-C.; Wang, S.; Chen, M.K.; Chung, T.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Kuo, H.Y.; Chen, J.-W.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.-T.; et al. Achromatic Metalens Array for Full-Colour Light-Field Imaging. Nature Nanotechnology 2019, 14, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Martins, A.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Z.; Long, Y.; Martins, E.R.; Li, J.; Liang, H. RGB Achromatic Metalens Doublet for Digital Imaging. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 3969–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hao, C.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Lan, T.; Qiu, C.-W.; Jia, B. Generation of Super-Resolved Optical Needle and Multifocal Array Using Graphene Oxide Metalenses. Opto-Electronic Advances 2021, 4, 200031–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, K.; Sun, Y.; Shen, F.; Li, Y.; Qu, S.; Liu, S. Polarization-Independent Longitudinal Multi-Focusing Metalens. Optics express 2015, 23, 29855–29866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, R.; Hu, S.; Sun, C.; Wang, B.; Cai, Q. Broadband Achromatic Metalens in the Visible Light Spectrum Based on Fresnel Zone Spatial Multiplexing. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

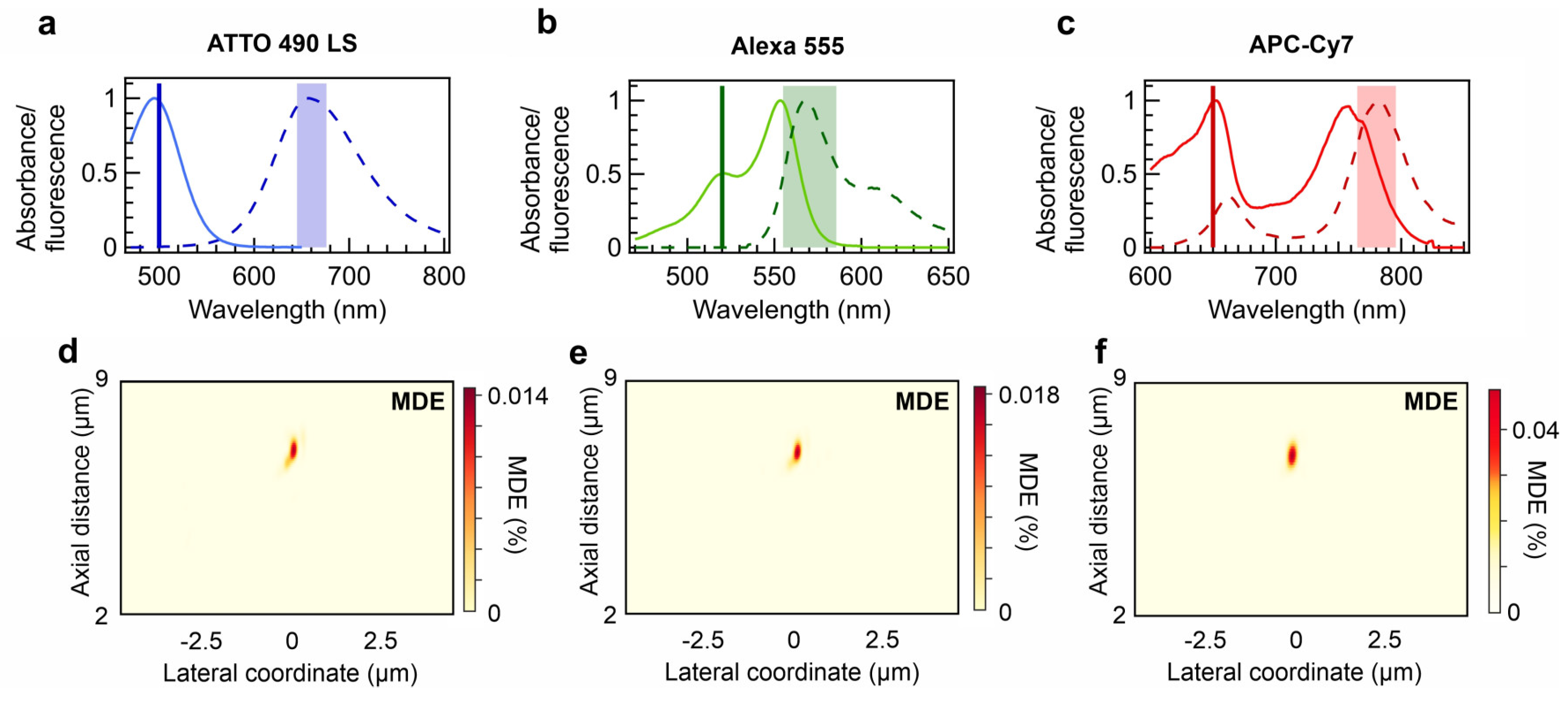

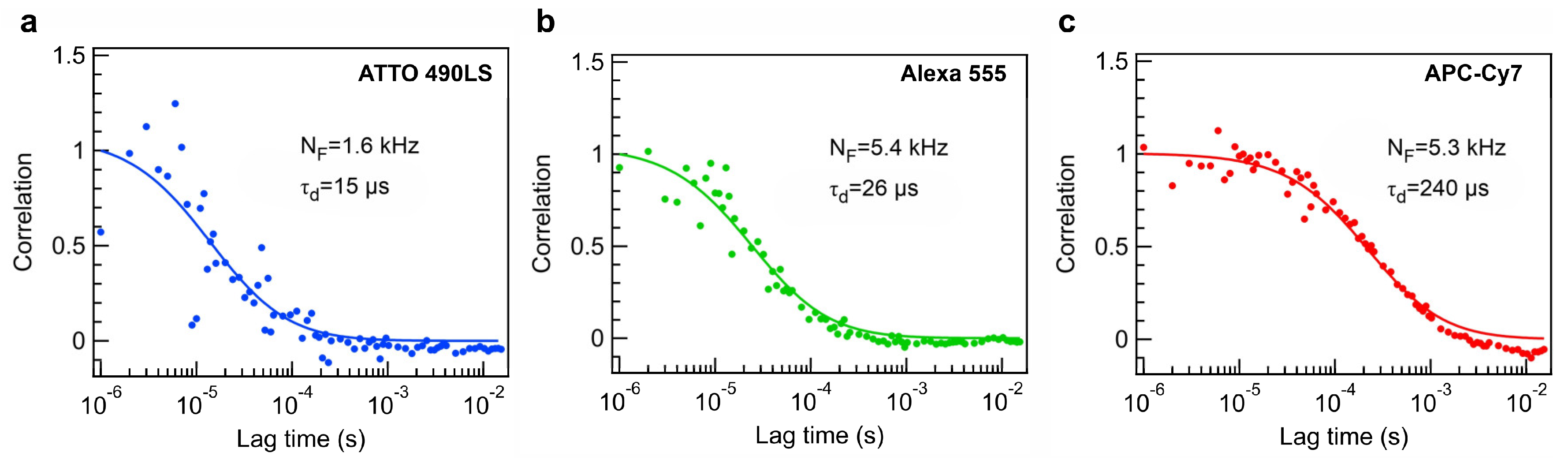

- Barulin, A.; Kim, Y.; Oh, D.K.; Jang, J.; Park, H.; Rho, J.; Kim, I. Dual-Wavelength Metalens Enables Epi-Fluorescence Detection from Single Molecules. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, H.R. Optical Properties of Silicon Nitride. Journal of the Electrochemical Society 1973, 120, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaouia, M.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Johnson, S.G.; Karalis, A. Quasi-Normal Mode Theory of the Scattering Matrix, Enforcing Fundamental Constraints for Truncated Expansions. Phys. Rev. Research 2021, 3, 033228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.-Y.; Fang, S.-L.; Lin, Y.-S.; Huang, W.-H.; Shieh, J.-M.; Yu, P.; Chang, Y.-C. Metasurfaces on Silicon Photonic Waveguides for Simultaneous Emission Phase and Amplitude Control. Optics Express 2023, 31, 12487–12496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potton, R.J. Reciprocity in Optics. Reports on Progress in Physics 2004, 67, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, R. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy: Simulations and Bio-Chemical Applications Based on Solid Immersion Lens Concept. ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE FÉDÉRALE DE LAUSANNE, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rigler, R.; Elson, E.S. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy: Theory and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012; Vol. 65; ISBN 3-642-59542-1.

- Moerner, W.E. High-Resolution Optical Spectroscopy of Single Molecules in Solids. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996, 29, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggeling, C.; Volkmer, A.; Seidel, C.A.M. Molecular Photobleaching Kinetics of Rhodamine 6G by One- and Two-Photon Induced Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy. ChemPhysChem 2005, 6, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstner, D.; Christensen, T.; Solanko, L.M.; Sage, D. Photobleaching Kinetics and Time-Integrated Emission of Fluorescent Probes in Cellular Membranes. Molecules 2014, 19, 11096–11130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H. On the Statistics of Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. Biophysical chemistry 1990, 38, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barulin, A.; Nguyen, D.D.; Kim, Y.; Ko, C.; Kim, I. Metasurfaces for Quantitative Biosciences of Molecules, Cells, and Tissues: Sensing and Diagnostics. ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Lee, S.; Kim, I. Recent Advances in Metaphotonic Biosensors. Biosensors 2023, 13, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Kim, H.; Han, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Eom, S.; Barulin, A.; Choi, I.; Rho, J.; Lee, L.P. Metasurfaces-Driven Hyperspectral Imaging via Multiplexed Plasmonic Resonance Energy Transfer. Advanced Materials 2023, 35, 2300229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).