Nipah virus (NiV) is an emergent and highly pathogenic zoonotic paramyxovirus in the genus: Henipavirus. NiV first emerged in Malaysia and Singapore in 1999. NiV was associated with an outbreak of severe febrile encephalitis associated with human deaths reported in Peninsular Malaysia beginning in late September 1998 (Chua et al., 2000). Later, NiV outbreaks led to many epidemics since 2001 in Bangladesh, India, Singapore, Malaysia, and other countries (Hsu et al., 2004). NiV targets vascular endothelial and neuronal cells causing severe encephalitic or respiratory syndrome with case fatality rates ranging from 40 to 100% in humans (Hsu et al., 2004; Eaton et al., 2006; Stone, 2011). Due to its high mortality and ease of transmission between species, NiV is categorized as a biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) pathogen. NiV requires the coordinated action of envelope glycoproteins G and F to recognize, bind, trigger and make entry into susceptible cells. NiV binds to ephrinB2 or ephrin B3 receptors that are expressed on microvascular endothelial cells to gain entry (Negrete et al., 2005 & 2006; Bonaparte et al., 2005). NiV G is responsible for the receptor binding resulting in conformational changes in G and triggering F glycoprotein. After triggering, the prefusion F will be activated to a post fusion F that harpoons itself into the adjacent cells causing the development of syncytium. Syncytium is a cellular structure formed due to multiple cell fusions of individual mononuclear cells (Aguilar and Iorio, 2012). Endothelial syncytium formation is a peculiar hallmark of NiV infection leading to cell destruction, inflammation, and hemorrhage. The syncytium leads to further spread, inflammation, and causing damage to the endothelial cells and neurons (Wong et al., 2002). There are no licensed treatments or vaccines available for treatment of NiV infections. As a result, NiV is listed in the World Health Organization (WHO) R&D Blueprint list of priority pathogens (WHO, 2022). Since 2001, India witnessed six nipah virus outbreaks so far and the first outbreak was reported in the state of West Bengal with a case fatality ratio (CFR) of 68%. Subsequently, outbreaks have been reported from West Bengal and Kerala with high CFR (WHO, 2023). To date, only limited data is available on NiV treatment strategies due to the pathogenic nature of the virus and experiments requiring BSL-4 facilities. No approved vaccines or treatments that specifically target NiV are available, and quarantine has been the predominant measure to limit the spread of the virus (Nahar et al., 2013).

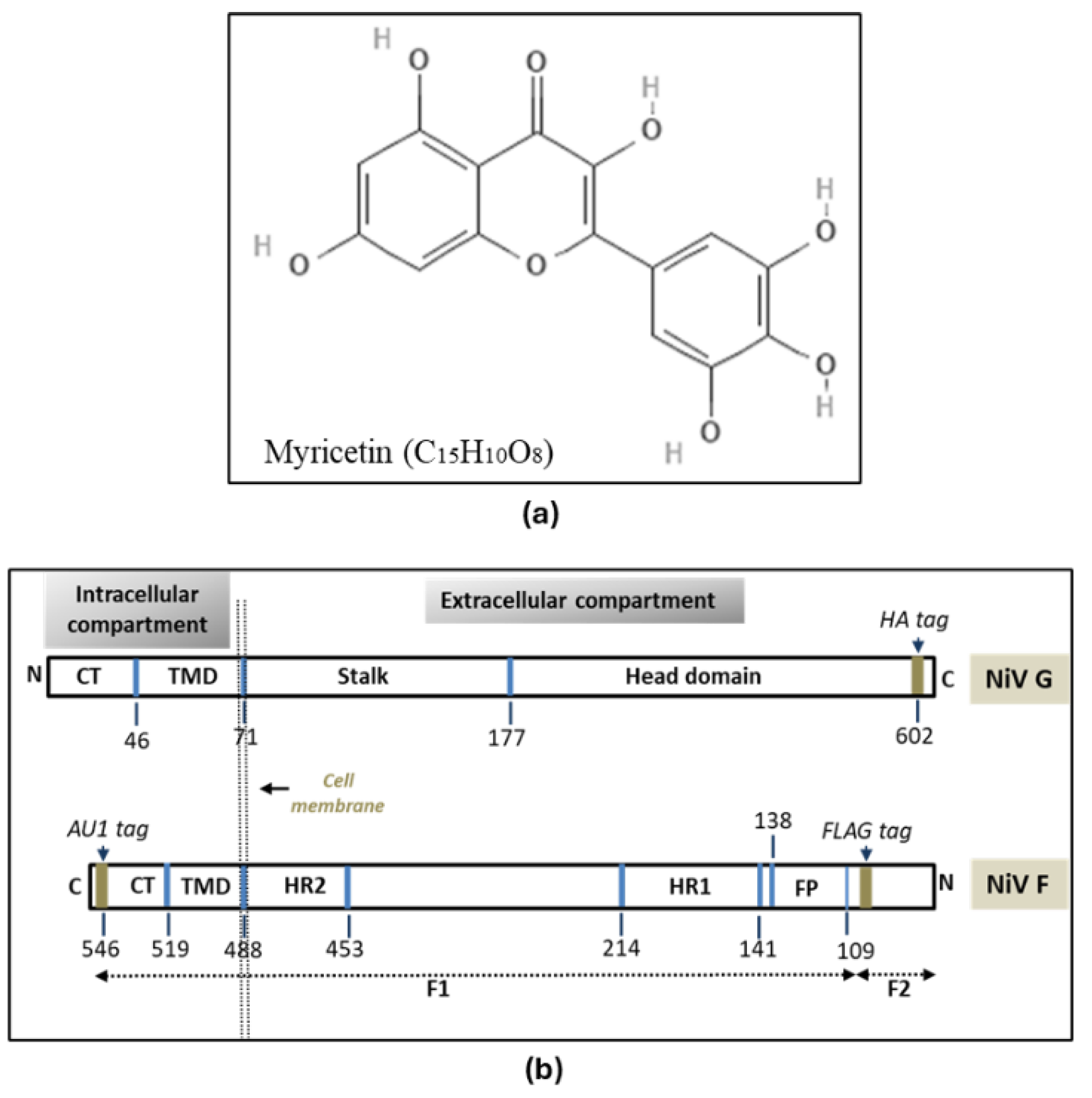

Substantial work has been carried out on the role of flavonoids as potential antivirals against several animal and human viruses, including COVID-19. Flavonoids were shown to exhibit their antiviral activity by (i) hindering the viral entry (ii) interfere with the host receptor binding (iii) inhibiting the function of the host-receptor itself (iv) hampering the viral replication process and/or viral assembly (v) block the release and cell-to-cell movement (vi) enhanced immune responses. (Wang et al., 2020; Kato et al., 2021; Gencsoy et al., 2022; Peng et al., 2022). Myricetin (MYR) is a flavonoid compound found in vegetables, fruits, and tea possess antioxidant properties (Ong and Khoo, 1997; Ross and Kasum, 2002; Semval et al., 2016), antimicrobial, anti-thrombotic, neuroprotective, and anti-inflammatory properties (Cushnie and Lamb, 2005; Gupta et al., 2014; Santhakumar et al., 2014). MYR has been shown to exhibit antiviral properties on several pathogenic viruses. Antiviral activity of MYR against HIV (Pasetto et al., 2014), HSV-1 (Lyu et al., 2005), SARS-CoV (Yu et al., 2012). In this study, the therapeutic potential of MYR as an antiviral agent and its role in mitigating the syncytial development triggered by NiV-F and -G envelope glycoproteins in-vitro was investigated.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Cell lines and Reagents

The cell lines used in this study was purchased from the National Center for Cell Sciences (NCCS, Pune, India). Two NiV permissive mammalian cell lines (express ephrinB2 receptor on cell surface) and a non-permissive cell line (very few ephrinB2 compared to 293Ts and veros) were used in this study. The NiV permissive cells lines are (i) human embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293T) and (ii) African green monkey kidney epithelial cells (Vero). The non-permissive cell line used in this study was the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line. 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco, USA) while CHOs and Vero cells were cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM) (Gibco, USA), both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermofisher Scientific, USA), 50 IU of penicillin ml

-1 (Sigma, USA), streptomycin ml

-1 (Sigma, USA), and 2 mM glutamine (Sigma, USA). Myricetin (3,3’,4’,5,5’,7-Hexahydroxyflavone) MW-318.23 g/mol (

Figure 1a) was purchased from the Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (TCI, India) was used in all the

in-vitro assays carried out in this study. MYR stock solution was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Five testing concentrations viz. 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, and 500 µM was used in the study to determine the optimal inhibitory potential of MYR on inhibiting syncytia development because of cell-to-cell fusion (fusogenicity).

2.2. Plasmid Constructs

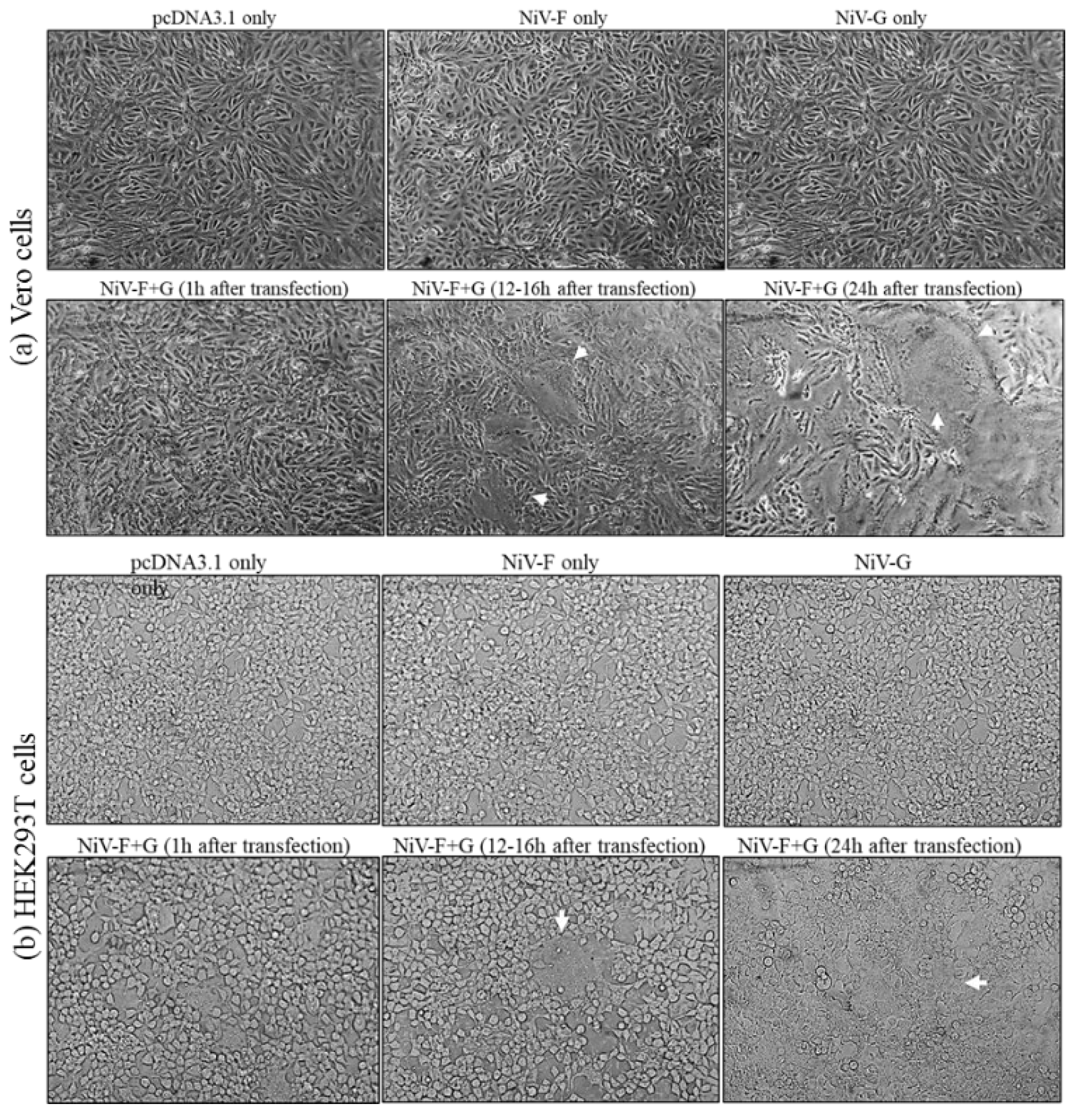

Codon-optimized wild-type (WT) nipah virus attachment G (NiV-G) and fusion glycoprotein F (NiV-F) used in the study were synthesized in pcDNA3.1 vector construct (GenScript, USA). The NiV-G is tagged at the C-terminus with hemagglutinin (HA) tag and the NiV-F was tagged at the C-terminus with AU1 tag and in the region when F is activated from the prefusion (F

0) to the post fusion (F

1) form (

Figure 1b). The construct design and organization of the plasmids were reported by Negrete et al., (2005). The NiV-G encodes a 602 amino acid attachment glycoprotein (~1.8kb nt) and the NiV-F encodes a 546 amino acid (~1.6 kb) fusion glycoprotein respectively. The inclusion of tags in the WT F and G plasmids facilitates the detection of the expressed viral proteins using SDS-PAGE, Western blotting and flow-cytometry with tag-specific primary and secondary antibodies.

2.3. Confirmation of NiV F and G Plasmids

The lyophilized wild type (WT) F and G in the pcDNA3.1 vector constructs were suspended in TE buffer and used for transformation into E. coli DH5-α competent cells following standard molecular biology protocols (Sambrook & Russel, 2001). After blue-white screening, plasmid F and G plasmid DNA was isolated from the bacterial cultures using Plasmid mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The confirmation of F and G sequence in the pcDNA3.1 vector (~5.4kbp) was carried out by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) with forward (CMV-Fwd) and reverse primers (BGH-Rev) flanking the multiple cloning site (MCS). The resulting PCR products were confirmed in 1% agarose gels.

2.4. MTT (Cell Viability) Assay

Cell viability (cytotoxicity) of MYR on the three cell lines used in this study was carried out using MTT assay (EZcount™ MTT Cell Assay Kit, Himedia, India) in 96-well immunoplates (Nunc, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Different concentrations of MYR (25, 50, 100, 250, 500 uM) were tested on the three cell lines to determine cytotoxicity. Briefly, cells at 70% confluency were treated MYR diluted in DMEM (100ul per well). Plates were incubated at 37°C in biological CO2 incubator (5%) for 24h. The multi-well plates were treated with 15ul of dye for the MTT assay and incubated for 4h. Later, the cell viability (cytotoxicity) was determined by spectrophotometric analysis at 570 nm using a microplate reader (uQuant BioTek Spectrophotometer, USA). Viability of MYR treated cells was calculated as a percentage relative to values obtained with DMSO treated cells.

2.4. Transfection with F and G Plasmids

To obtain a linear correlation between the amount of DNA transfected and the levels of observable and countable syncytia, NiV-F and -G plasmids were transfected into 293T or vero cells at ~70% confluence in different ratios (1:1, 2:1, 1:2 ratio of F and G at 2 µg/well in 6-well plates. The concentrations of F and G plasmids used for transfection in 12- or 24-well plates were used accordingly. Different combinations of NiV F and G plasmids were included in the study to determine the progress and inhibition of syncytia in permissive and non-permissive cell lines. The different transfection combinations are (i) NiV-F only (F+pC3.1); (ii) NiV-G only (G+pC3.1) (iii) NiV F+G (co-transfection). Positive controls are NiV F+G (co-transfected) without MYR treatment and negative controls consisting of only pCDNA3.1 transfected cells. CHOs are used as a non-permissive cell line and included as negative control in all the experiments along with HEK293T and vero cells (Supplementary Table-1). Cells that were transfected only with F or G alone, the final concentration in each well was adjusted with pcDNA3 as filler DNA. Briefly, on day zero, the 6-well plates were seeded separately with HEK-293T, VERO, or CHO cells (~2x106) respectively. The growth media used was either DMEM or MEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After the cells reached 70% confluence on Day-1, cells were transfected with NiV-F and(or) -G plasmids using Lipofectamine-3000 transfection reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Before the cells were fixed or treated with different concentrations of MYR, the growth medium was aspirated with an automatic aspirator and the cells were washed one time with phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 1% FBS.

2.5. Time-of-Addition (Time-Course) Assay of Antivirals

Time-of-addition experiments were designed to investigate the antiviral potential of MYR on syncytial (cell-to-cell fusion) progression in HEK293T, vero and CHO cells at two different stages after the completion of transfection. MYR was diluted in required concentrations in MEM or DMEM supplemented with 10% FMS and added to the cells with different combinations of F and G plasmids (Supplementary Table.1). Cells were treated with MYR (a) 1h and (b) 6h after transfection. The cells were washed one time with PBS containing 1% FBS before the addition of MYR diluted in the growth medium. All the experiments were carried out in 6-well plates (Nunc, USA) unless specified. Each concentration of the compound was tested in triplicates. Each of the experiments in this study was repeated at least three times to ascertain the effective concentration of MYR in inhibiting the formation and progression of syncytia.

2.6. Quantification of Syncytia

The multi-well plates with HEK293Ts and vero cells treated with different concentrations of MYR were observed at 100x magnification 18-24h post transfection for the enumeration of syncytial development due to the cell-to-cell fusion process of NiV F and G interactions. Ten fields per well of 6-well plates were observed under 100x magnification for enumerating the syncytial development. A total of 10 fields (triplicate) were observed for each treatment of MYR. Wells transfected with NiV F+G only (no MYR treatment) were considered as positive control while cells transfected with (i) pCDNA3.1 (ii) F only (iii) G only were considered as negative controls. Similar transfection combinations in CHO cells (non-permissive) are included as additional negative control. At 18-24h after the addition of MYR, the cells were fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde (PFA) to halt further syncytial development in the wells and to facilitate quantification of syncytia. The percentage of syncytial inhibition (arrest of cell-to-cell fusion) was measured as the reduction in the number of syncytia in each well in comparison to the positive and negative controls.

2.7. Protein Expression, SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) and Western Blotting

To determine if MYR could block or interfere with the expression of NiV G and F in HEK293Ts, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was carried out followed by western blotting. The non-transfected, transfected (without treatment with compound), and antiviral-treated cells were harvested 18h after treatment with MYR in 6-well plates (~30000 cells/well). Following transfection with NiV F and G plasmids, the cells were harvested from each well using cell lysis buffer (Genei, India) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal volumes of the protein lysate were loaded in 12% PAGE gels containing SDS followed by membrane transfer onto a nitrocellulose membrane (NCM) for probing with antibodies against F and G proteins. Primary and secondary antibodies were used for the detection of expressed F and G proteins in transfected cells by Western blotting. NiV-G glycoprotein was detected with anti-HA tag antibodies (1°Ab is rabbit anti-HA antibodies (1:500-1000 dilution) while 2°Ab are goat anti-rabbit antibodies (1:1000-2000 dilution) (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). The F protein was detected using anti-FLAG antibodies (primary Ab: mouse-anti FLAG) (1:500-1000 dilution) while the secondary are goat-anti-mouse-FLAG antibodies (1:1000-2000 dilution) (Thermofisher Scientific, USA) respectively. The band intensities from the same volume of each lysate were determined.

2.8. Flow Cytometry Quantification of NiV-F Cell Surface Expression (CSE)

The syncytia formation initiates with the binding of G glycoprotein to ephrin B2/B3 receptors followed by conformational changes in F glycoprotein leading to cell-to-cell fusion and syncytial development. In this study, flow cytometry was carried out to measure the cell surface expression (CSE) levels of NiV F glycoprotein on the surface of HEK293Ts (per well of a six-well plate, 70% confluence) since F is the fusogenic factor responsible for membrane fusion between the virus-cell after G triggers F. Since NiV G protein is a type-II membrane protein, the HA-tag sequence was seen in the cytoplasmic side of the cell and hence detection of G on cell surface using anti-HA fluorophores were not used. The flow cytometry quantification of G protein is only possible in the availability of antibodies to the ectodomain (G-head region) as the head region does not contain any tags for detection. However, since a linear correlation between the expression of F and G was already established, flow cytometry was confined to NiV F detection as it indirectly reflects the activity of interaction with G protein in-vitro assays. Cells were collected at 18-24h post-transfection treatment with different concentrations of MYR. All the steps in flow cytometry experiment were carried out on ice till the MFI values were generated. Cells expressing WT NiV-F glycoprotein were incubated with anti-FLAG antibodies (1°Ab: anti-DYKDDDDK recombinant rabbit polyclonal antibody) (Thermofisher Scientific, USA) at 4°C for 1h respectively. The cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% FBS and then incubated with a fluorescent secondary antibody (Goat anti-rabbit recombinant secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 488) (Thermofisher Scientific, USA) for 30 min at 4°C. Later, the cells were fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde, and the mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry (Guava EasyCyte-8; EMD Millipore, USA). The experimental results were analyzed using FLOWJO v10 (USA). Cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 only was considered as a negative control. NiV-F protein (Alexa Fluor™ 488) was detected using FL-1 channel specific for fusion protein. Resulting mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) values were calculated with Guava Easycyte software associated with the flow cytometer. The MFI values were normalized to 100% for NiV F+G cells and compared for the determination of CSE of F protein expression levels treated with MYR in HEK293T cells.

3. Results

3.1. Confirmation of NiV-F and G Plasmids

Each of the transformed recombinant F and G DH5α colonies were picked and plasmid DNA isolation was carried out. PCR was performed using F and G plasmid DNA and PCR products were analyzed on 1% agarose gels. PCR products yielded the expected size of F and G sequences. The NiV-F insert yielded ~1.6kbp and NiV-G insert generated a ~1.8kbp respectively (Supplementary

Figure 1a). The F and G plasmids were diluted in nanopure water are used for all the transfection studies in-vitro.

3.2. MTT Assay

Seven different concentrations of MYR (10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 & 1000 uM) were tested on 293T, vero and CHO cells in 96-well immunoplates. MYR exhibited a mild cytotoxicity (~10%) on the three cell lines at 250 uM while at higher concentrations viz. 500 uM in all the cell lines at 70-80% while 1000 uM was 100% cytotoxic to all the three cell types tested. While the remaining concentrations did not alter the morphology or the normal cellular functions (Supplementary

Figure 1b). Based on the results obtained from the MTT assay, in-vitro testing of MYR was limited to six concentrations 10, 25, 50, 100, 250 & 500.

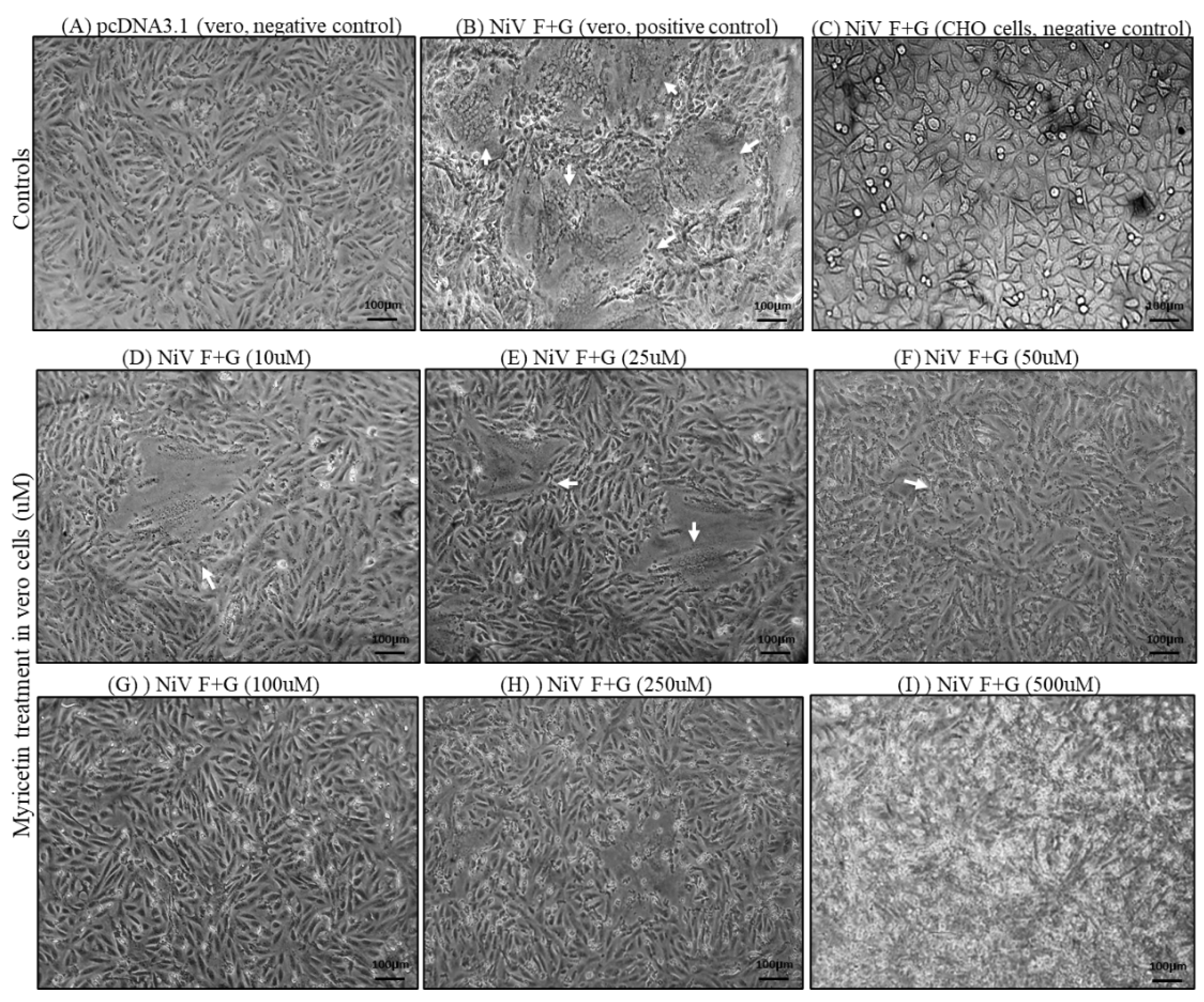

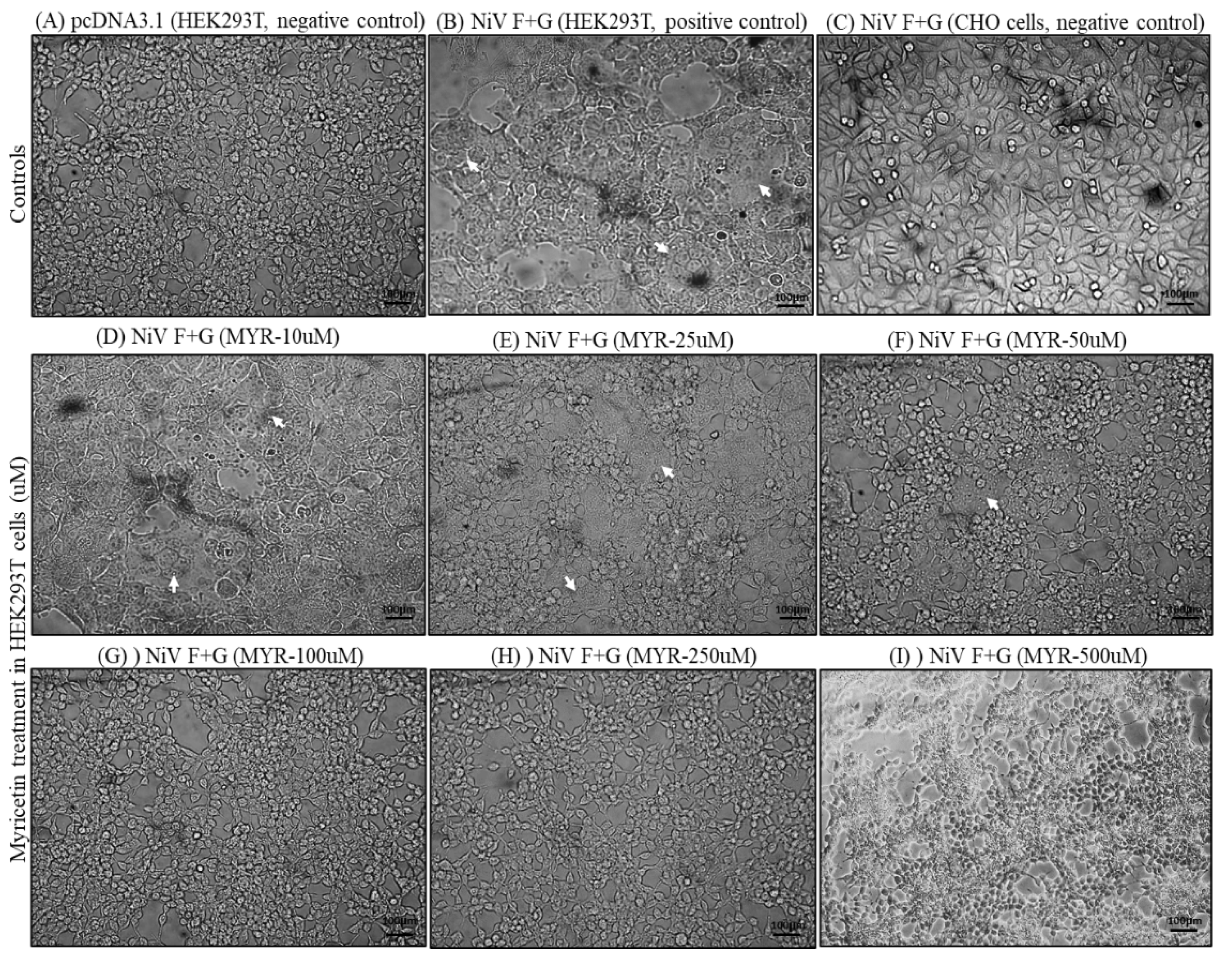

3.3. Transfection & Syncytia Development

To obtain a linear correlation between the amount of DNA transfected and the levels of observable and countable syncytia, WT NiV-F and -G expression plasmids were transfected into 293T or Vero cells (~70% confluence) at a 2:1 ratio (2 µg/well) in 6-well plates. Observable and measurable syncytia was observed with a 2:1 ratio of F and G. G expressed higher than F at 1:1 and 1:2 ratio of F to G. Therefore, a 2:1 ratio of F and G was used in all the

in-vitro experiments. Syncytium development initiated at 10-12h after transfection and later progressed to a point where the cells exhibited observable and countable syncytia at 16-18h. After 24h, the cells were profusely fused to form large syncytia which cannot be used for quantification measurements. Cells that were co-transfected with NiV F and G developed syncytia were used as positive controls. Cells transfected with NiV-F only, G only, or pcDNA3 only did not develop any syncytia and served as negative controls (

Figure 2). No syncytia were observed in non-permissive CHO cells and served as additional negative control.

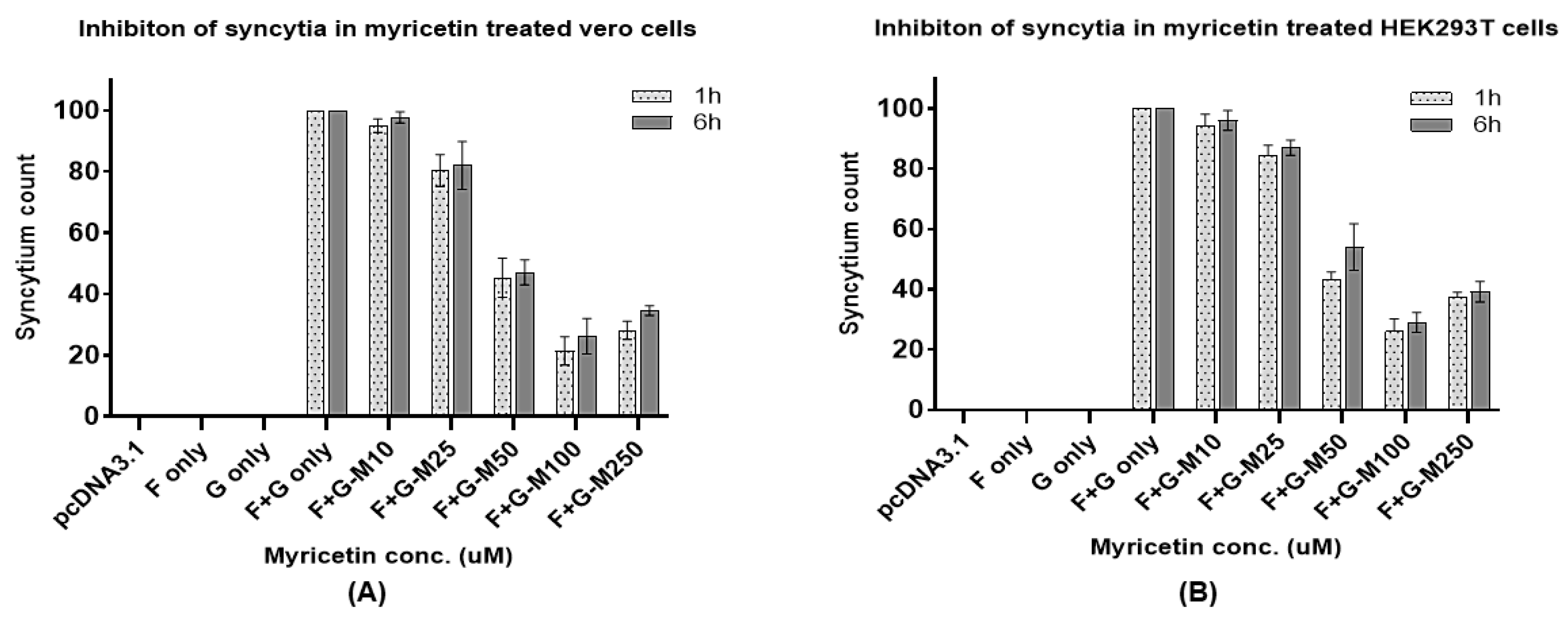

3.4. Inhibition of Syncytia and Quantification

The total number of syncytia was normalized to 100% based on F+G (positive) transfected cells. Syncytia was more prominent and measurable in vero cells compared to HEK293Ts. Though syncytia started to develop 6h after the transfection, the size and number of syncytia increased during a 12h period post-transfection. MYR was effective in restricting syncytial development at 1h and 6h addition of MYR after transfection. The inhibition of syncytial development (cell-to-cell fusion) was evident under microscopic observation from 50µM to 250uM with visible distinction and further effective at 100 µM in vero (

Figure 3) and HEK293T (

Figure 4) and vero cells. The percentage of syncytia inhibition was calculated by normalizing the positive control wells (F+G without MYR treatment) and compared the inhibition percentage with MYR treatments in HEK and vero cells. The highest percentage of syncytial inhibition was observed in 100uM at 74-80% in HEK and vero cells in 1h time-of-addition. The 6h time-of-addition results were comparable to the 1h outcomes but at ±2-5% reduction in the overall percentage of reduction in syncytial count. These results indicated that MYR was still effective in the 6h time-of-addition method that provided sufficient time for the F and G protein expression inside the cells after the transfection (

Figure 5 A and B). The 500uM results were excluded from the analysis due to cytotoxicity of MYR at higher concentrations determined with MTT assay.

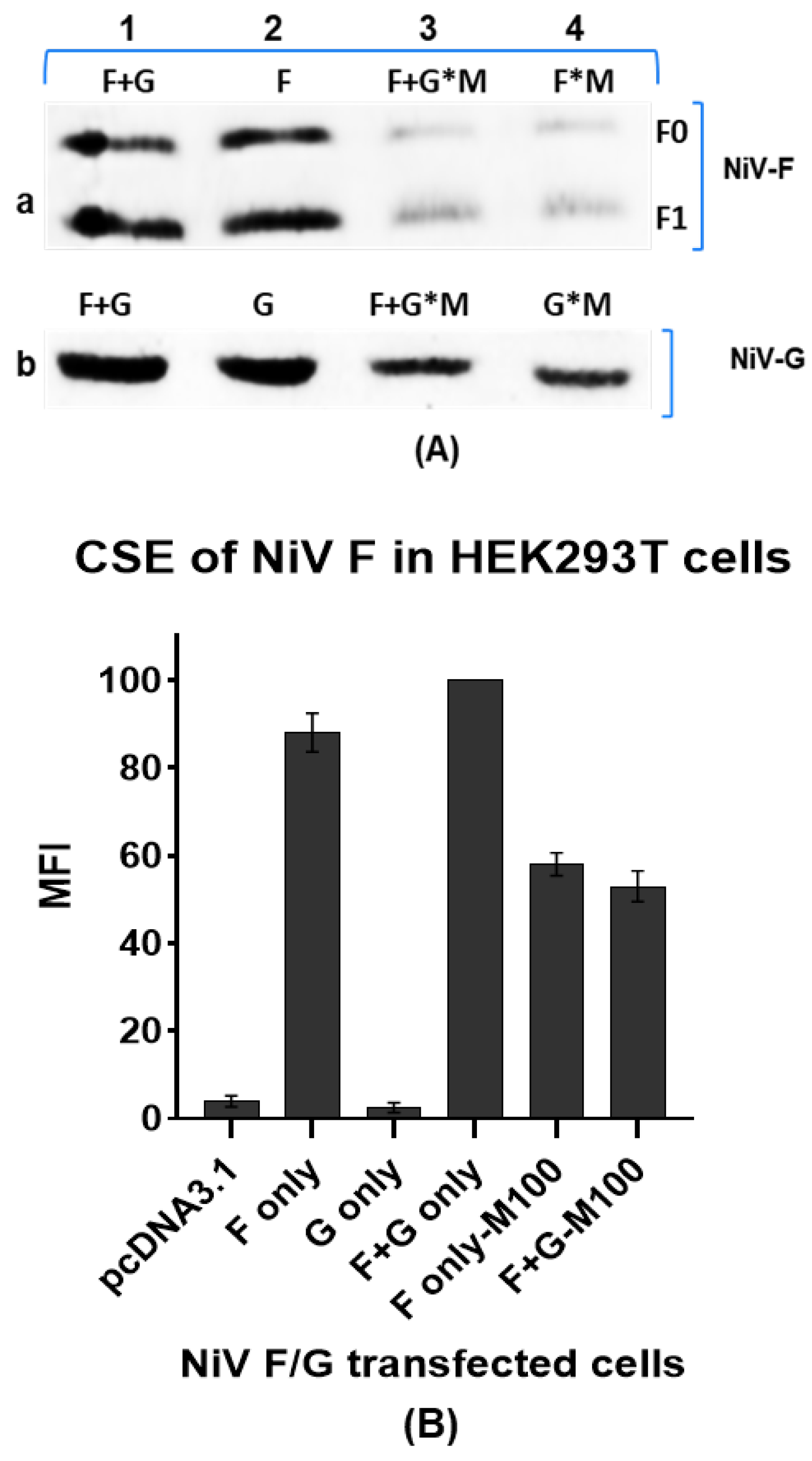

3.5. Western Blotting and Flow Cytometry

HEK cells were lysed using lysis buffer and equal volume of protein lysate from each of the F and G combinations was loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE gel followed by Western blotting of the separated protein samples. The SDS-PAGE separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and probing with primary and secondary antibodies. There is a marked reduction in the total amount of protein concentration that were treated with MYR (100uM) compared to the untreated F-only and F+G only (positive control) or G-only and F+G only samples. Based on the Western blots obtained from the samples, it can be implied that MYR had an effect either on the overall protein expression of the cell or the compound in some way interacted with the expressed proteins thereby reducing their detection with the respective protein tags. MYR could have played one or more roles on (a) reduced F and G expression levels inside the cell (b) minimize or mask the binding affinity of G to ephrinB2/B3 (c) masking the F and G interactions by interfering with F or G envelope glycoproteins that lead to the inhibition in the number of syncytia (fusion) development in each of the cell lines tested (

Figure 6A). The MFI values obtained in flow cytometry strengthen the inhibitory or interfering role of MYR on F and G proteins expression levels leading to a reduction in optimal levels of F and G on HEK cell surface. Lower MFI values were recorded in F-only and F+G only HEK cells that were treated with MYR 1h after the transfections. Higher MFI value was noticed in F only and F+G cells that were untreated with MYR. The CSE expression levels for MYR treated F only and F+G were 35-45% lower compared to the untreated combination (

Figure 6B). Lower levels of F and G expression were also observed in Western blotting analysis of F and G proteins.

4. Discussion

Studies on the understanding of nipah virus (NIV) F and G envelope glycoproteins and the syncytial development of Nipah virus (NiV) are of great interest in understanding pathogenesis of the disease and exploring potential antiviral strategies. In this study, the antiviral potential of MYR was established in two different mammalian cell lines, HEK293T and vero cells which are permissive cell lines for NiV infections. The role of MYR in inhibiting the progression of syncytial development was proved by different experimental approaches in-vitro. These observations are significant given the severity of virus infection in causing severe and acute life threatening NiV infections. Syncytium formation in virus susceptible cells is the pathological hallmark of NIV infections. NiV infections are known to be characterized by the formation of endothelial syncytium, which leads to inflammation and hemorrhage (Hauser et al., 2021). The coordinated interplay of NiV F and G result in cell-to-cell fusion of adjoining cells and eventually progressing to serious pathological symptoms such as meningitis and even death if untreated. The inhibition of syncytial development showed a dose-dependent response with seven different concentrations of MYR treatment (Supplementary

Figure 1b). MYR at 500uM concentration was cytotoxic in all the cells lines tested in this study. At 250uM, MYR exhibited a 5-10% cytotoxicity in HEK293T and vero cells were also reflected in the quantification of syncytia at higher MYR concentrations. In both the time-of-addition experiments (1h and 6h), MYR exhibited antiviral potential. A ~5-10% reduced activity of MYR in terms of syncytia inhibition was observed in the 6h time-of-addition experiment. These results indicate that MYR was effective even 6h after the co-transfection with F+G which provided sufficient window time for the expression and synthesis of F and G proteins in vero and HEK293T cells. MYR could have influenced the F and G expression levels which needs further investigation in future studies. But the fact that MYR exhibited an inhibitory influence could have resulted from (a) specific or stochastic interactions with F/G/F+G (b) masking the regions on G and F causing a failure to establish cell-to-cell fusion thereby inhibiting the syncytial development. Lower MFI values for the CSE of MYR treated NiV F HEK293T cells further proves the effects of MYR on F expression. Recently, flow cytometry-based methods for studying the CSE levels and understanding the interactions between NiV F and G proteins provided important insights into the molecular mechanisms of NiV F and G interactions (Stone et al., 2017). Flow cytometry is proven to a preferred choice over co-precipitation or immune-precipitation methods to study protein-protein interactions since the envelope glycoprotein interactions can be studied in real-time on the surface of live cells rather than investigating these interactions after cell lysis methods that involve harsh chemicals that require detergents which would have an influence on the protein-protein interactions (Stone et al., 2017; Tsurudome et al., 2018; Yeo, 2021; Wong et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2024). MYR was reported to block Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) infection by directly interacting with the viral gD protein. This interaction disrupts HSV gD to attach to host cells and its fusion with the host cell membrane (Li et al., 2020). MYR played an antiviral role in the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 via interfering with the virus spike protein from binding to its receptor ACE2 (Agrawal et al., 2023). In other reports, MYR demonstrated antiviral properties in inhibiting Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV) replication cycle through the upregulation of the transcription levels in the NF-kB and IRF7 pathways suggesting a modulating effect of host immune responses inside the cell (Peng et al., 2022). Additionally, MYR has shown antiviral activity against HIV-1 by significantly reducing the binding of HIV-1 virions to SEVI fibrils (Ren et al., 2018). Currently, there are no approved therapeutics available for treating NiV infection in humans. Another potential antiviral candidate, ALS-8112, has been tested against NiV and other paramyxoviruses. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the antiviral potential of MYR in mitigating the effects of syncytial progression which is a pathological hallmark of NiV infection. The outcome of this work needs to be reciprocated in experimental hosts to further the findings of the experiments. Therefore, our present study is quite essential to further the scope of work in investigating the antiviral scope of MYR and other flavonoid compounds as preventive line of defense against NiV infections.

5. Conclusion

Based on the given findings, it can be concluded that MYR exhibits strong antiviral potential in inhibiting the syncytial development of NiV in-vitro. The dose-dependent response and distinct syncytial formation in treated cultures indicate the effectiveness of MYR as an antiviral agent against NiV. Further studies are recommended to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the antiviral activity of MYR and its potential application in in-vivo models. Additionally, the evaluation of MYR’s cytotoxicity and safety profile is crucial for its progression towards clinical trials. The findings of this study contribute to the understanding of antiviral strategies against NiV and may pave the way for the development of novel therapeutics targeting NiV infection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Agrawal, P. K., Agrawal, C., & Blunden, G. Antiviral and Possible Prophylactic Significance of Myricetin for COVID-19. Nat. Prod. Comm. 18(4), 1934578X231166283, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, H. C., Matreyek, K. A., Filone, C. M., Hashimi, S. T., Levroney, E. L., Negrete, O. A., ... & Lee, B. N-glycans on Nipah virus fusion protein protect against neutralization but reduce membrane fusion and viral entry. J. Virol. 80(10), 4878-4889, (2006). [CrossRef]

- Ang, B. S., Lim, T. C., & Wang, L. Nipah virus infection. J. Clin. microbial. 56(6), 10-1128, (2018).

- Bishop, K. A., Hickey, A. C., Khetawat, D., Patch, J. R., Bossart, K. N., Zhu, Z., Wang, L. F., Dimitrov, D. S., and Broder, C. C. J. Virol. 82, 11398–11409, (2008).

- Carrasco-Hernandez, R., Jácome, R., López Vidal, Y., & Ponce de León, S. Are RNA viruses candidate agents for the next global pandemic? A review. ILAR J, 58(3), 343-358, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., Deb, B., Barbhuiya, P. A., & Uddin, A. Analysis of codon usage patterns and influencing factors in Nipah virus. Virus Res. 263, 129-138, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Sun M, Zhang H, Zhang X, Yao Y, Li M, Li K, Fan P, Zhang H, Qin Y, Zhang Z, Li E, Chen Z, Guan W, Li S, Yu C, Zhang K, Gong R, Chiu S. Potent human neutralizing antibodies against Nipah virus derived from two ancestral antibody heavy chains. Nat Commun. 2024 Apr 6;15(1):2987. PMID: 38582870; PMCID: PMC10998907. [CrossRef]

- Devnath, P., & Masud, H. M. A. A. Nipah virus: a potential pandemic agent in the context of the current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic. New Microb. New Inf., 41, 100873, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J. H., Anthony, S. J., Islam, A., Kilpatrick, A. M., Ali Khan, S., Balkey, M. D., & Daszak, P. Nipah virus dynamics in bats and implications for spillover to humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117(46), 29190-29201, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z., Li, T., Han, J., Feng, S., Li, L., Jiang, Y., ... & Li, C. Assessment of the immunogenicity and protection of a Nipah virus soluble G vaccine candidate in mice and pigs. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1031523, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Hans, N. Malik, A., & Naik, S. Antiviral activity of sulfated polysaccharides from marine algae and its application in combating COVID-19: Mini review. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 13, 100623, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hao, C., Yu, G., He, Y., Xu, C., Zhang, L., & Wang, W. Marine glycan–based antiviral agents in clinical or preclinical trials. Rev. Med. Virol. 29(3), e2043, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Harcourt, A. H., Parks, S. A., & Woodroffe, R. Human density as an influence on species/area relationships: double jeopardy for small African reserves?. Biodiv. Conserv. 10, 1011-1026, (2001). [CrossRef]

- Harit, A. K., Ichhpujani, R. L., Gupta, S., & Gill, K. S. (2006). Nipah/Hendra virus outbreak in Siliguri, West Bengal, India in 2001. Ind. J. Med. Res. 123(4), 553.

- Hauser, N., Gushiken, A. C., Narayanan, S., Kottilil, S., & Chua, J. V. Evolution of Nipah virus infection: past, present, and future considerations. Trop. Med. Infec. Dis. 6(1), 24, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kalbhor, M. S., Bhowmick, S., Alanazi, A. M., Patil, P. C., & Islam, M. A. Multi-step molecular docking and dynamics simulation-based screening of large antiviral specific chemical libraries for identification of Nipah virus glycoprotein inhibitors. Biophys. chem. 270, 106537 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Levroney, E. L., Aguilar, H. C., Fulcher, J. A., Kohatsu, L., Pace, K. E., Pang, M., Gurney, K. B., Baum, L. G., & Lee, B. Novel innate immune functions for galectin-1: galectin-1 inhibits cell fusion by Nipah virus envelope glycoproteins and augments dendritic cell secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. J. Immunol. 175: 413–420, (2005). [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Xu, C., Hao, C., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, S., Wang, W. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus by myricetin through targeting viral gD protein and cellular EGFR/PI3K/Akt pathway. Antiviral Res. 177: 104714, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lipin, R., Dhanabalan, A. K., Gunasekaran, K., & Solomon, R. V. Piperazine-substituted derivatives of favipiravir for Nipah virus inhibition: What do in silico studies unravel?. SN Appl. Sci. 3(1), 110, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. F., & Yu, H. Z. (2014). Research Progress on plant origins and extraction methods of Myricetin. J. Anhui Agric. Sci, 42, 4781-4783.

- Medina-Magües, E.S., Lopera-Madrid, J., Lo, M.K. et al. Immunogenicity of poxvirus-based vaccines against Nipah virus. Sci. Rep. 13, 11384, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A. L., Cuéllar, A. F., Arévalo, G., Santamaría, B. D., Rodríguez, A. K., Buendia-Atencio, C., & Losada-Barragán, M. Antiviral activity of myricetin glycosylated compounds isolated from Marcetia taxifolia against chikungunya virus. EXCLI J. 22, 716- 718, (2023).

- Nahar, N., Mondal, U.K., Hossain, M.J., Uddin Khan, M.S., Sultana, R., Gurley, E.S., Luby, S.P. Piloting the promotion of bamboo skirt barriers to prevent Nipah virus transmission through date palm sap in Bangladesh. Glob. Health Promot. Int. 28: 378 –386, (2013). http://doi.org/10.1093/heapro /das020. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H., He, J., Yang, Z., Yao, X., Zhang, H., Li, R., & Liu, L. Myricetin possesses the potency against SARS-CoV-2 infection through blocking viral-entry facilitators and suppressing inflammation in rats and mice. Phytomed., 116, 154858, (2023).

- Peng S, Fang C, He H, et al. Myricetin exerts its antiviral activity against infectious bronchitis virus by inhibiting the deubiquitinating activity of papain-like protease. Poultry Science. 2022 Mar;101(3):101626. PMCID: PMC8741506. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkin, A. G., & Hummel, J. J. LXXVI.—The colouring principle contained in the bark of Myrica nagi. Part I. J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 69, 1287-1294, (1896).

- Pillai, V., Krishna, G., & Valiya Veettil, M. Nipah virus: past outbreaks and future containment. Viruses, 12(4), 465, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ramharack, P., Devnarain, N., Shunmugam, L., & Soliman, M. E. Navigating Research Toward the Re-emerging Nipah Virus-A New Piece to the Puzzle. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 25(12), 1392-1401, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ren, R., Yin, S., Lai, B., Ma, L., Wen, J., Zhang, X., ... & Li, L. Myricetin antagonizes semen-derived enhancer of viral infection (SEVI) formation and influences its infection-enhancing activity. Retrovirology, 15(1), 1-24, (2018).

- Sambrook J. & Russell D. W. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual (3rd ed.). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, (2001)..

- Sazzad, H. M., Hossain, M. J., Gurley, E. S., Ameen, K. M., Parveen, S., Islam, M. S., ... & Luby, S. P. Nipah virus infection outbreak with nosocomial and corpse-to-human transmission, Bangladesh. Emerg. Inf. Dis. 19(2), 210, (2013). [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q., Guo, Q., Xu, W. P., Li, Z., & Zhao, T. T. Specific inhibitory effect of κ-carrageenan polysaccharide on swine pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza virus. PloS one, 10(5), e0126577 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Shariff, M. Nipah virus infection: A review. Epidem. Inf. 147, e95, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Kumar, R., Sharma, A., Hajam, Y. A., & Kumar, N. Nipah Virus: An Active Causative Agent For Respiratory And Neuronal Ailments. Epidem. Transm. Inf. dis. 78, (2020).

- Singh, N., Brar, R. S., Chavan, S. B., & Singh, J. Scientometric analyses and visualization of scientific outcome on Nipah virus. Curr. Sci. 117(10), 1574-1584, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Stone JA, Vemulapati BM, Bradel-Tretheway B, Aguilar HC. Multiple Strategies Reveal a Bidentate Interaction between the Nipah Virus Attachment and Fusion Glycoproteins. J Virol. 2016 Nov 14;90(23):10762-10773. PMCID: PMC5110167. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talarico, L. B., & Damonte, E. B. Interference in dengue virus adsorption and uncoating by carrageenans. Virology, 363(2), 473-485, (2007). [CrossRef]

- Tsurudome M, Ohtsuka J, Ito M, Nishio M, Nosaka T. The Hemagglutinin-Neuraminidase (HN) Head Domain and the Fusion (F) Protein Stalk Domain of the Parainfluenza Viruses Affect the Specificity of the HN-F Interaction. Front Microbiol. 2018 Mar 13;9:391. PMCID: PMC5859044. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong JJ, Chen Z, Chung JK, Groves JT, Jardetzky TS. EphrinB2 clustering by Nipah virus G is required to activate and trap F intermediates at supported lipid bilayer-cell interfaces. Sci Adv. 2021 Jan 27;7(5):eabe1235. PMCID: PMC7840137. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong KT, Shieh W-J, Kumar S, Norain K, Abdullah W, Guarner J, Goldsmith CS, Chua KB, Lam SK, Tan CT. Nipah virus infection: pathology and pathogenesis of an emerging paramyxoviral zoonosis. Am. J. Pathol. 161: 2153–2167, (2002). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T., Cui, M., Zheng, C., Wang, M., Sun, R., Gao, D., & Zhou, H. Myricetin inhibits SARS-CoV-2 viral replication by targeting Mpro and ameliorates pulmonary inflammation. Fron. Pharm. 12, 669642, (2021).

- Yeo YY, Buchholz DW, Gamble A, Jager M, Aguilar HC. Headless Henipaviral Receptor Binding Glycoproteins Reveal Fusion Modulation by the Head/Stalk Interface and Post-receptor Binding Contributions of the Head Domain. J Virol. 2021 Sep 27;95(20):e0066621. . Epub 2021 Jul 21. PMCID: PMC8475510. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).