Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

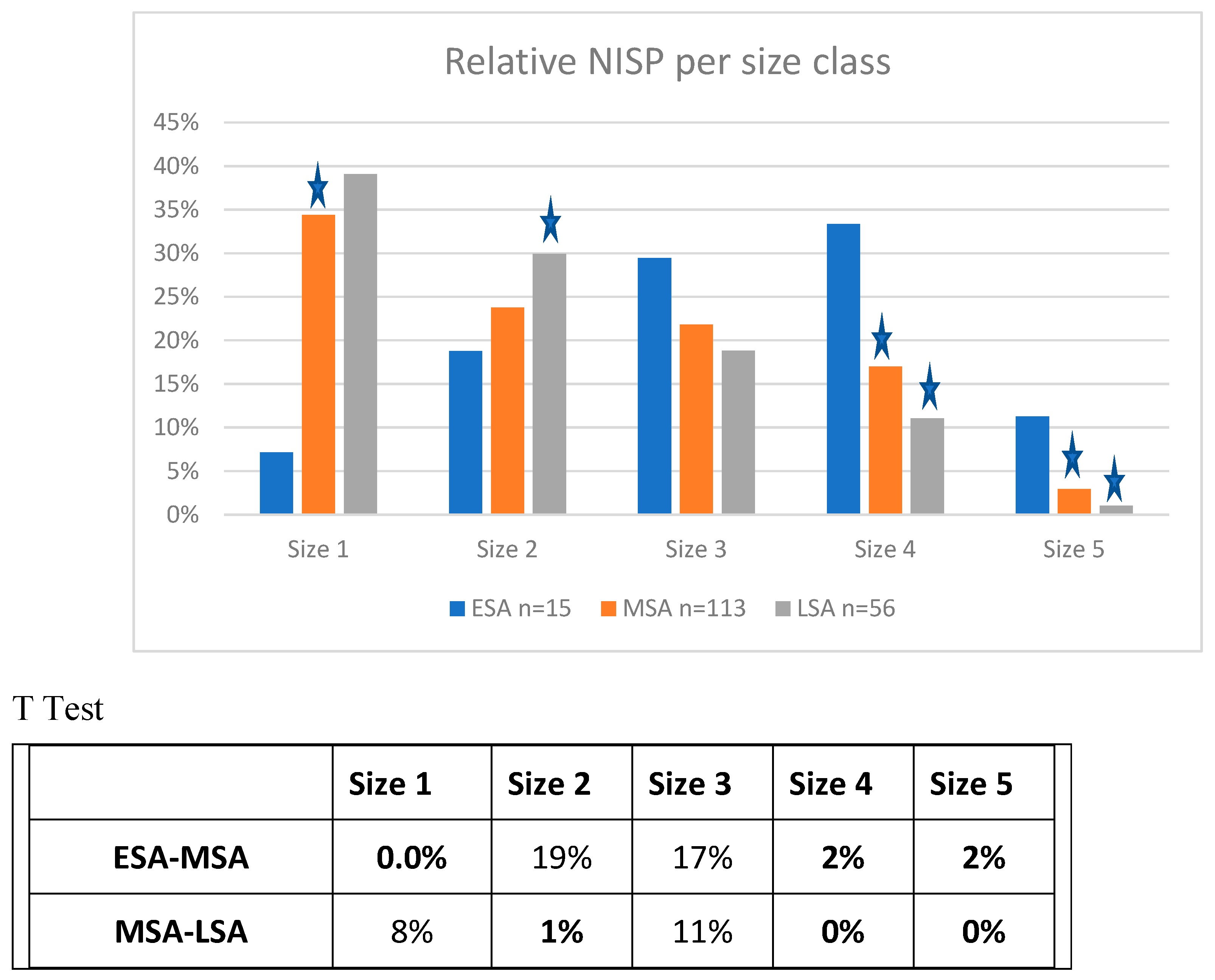

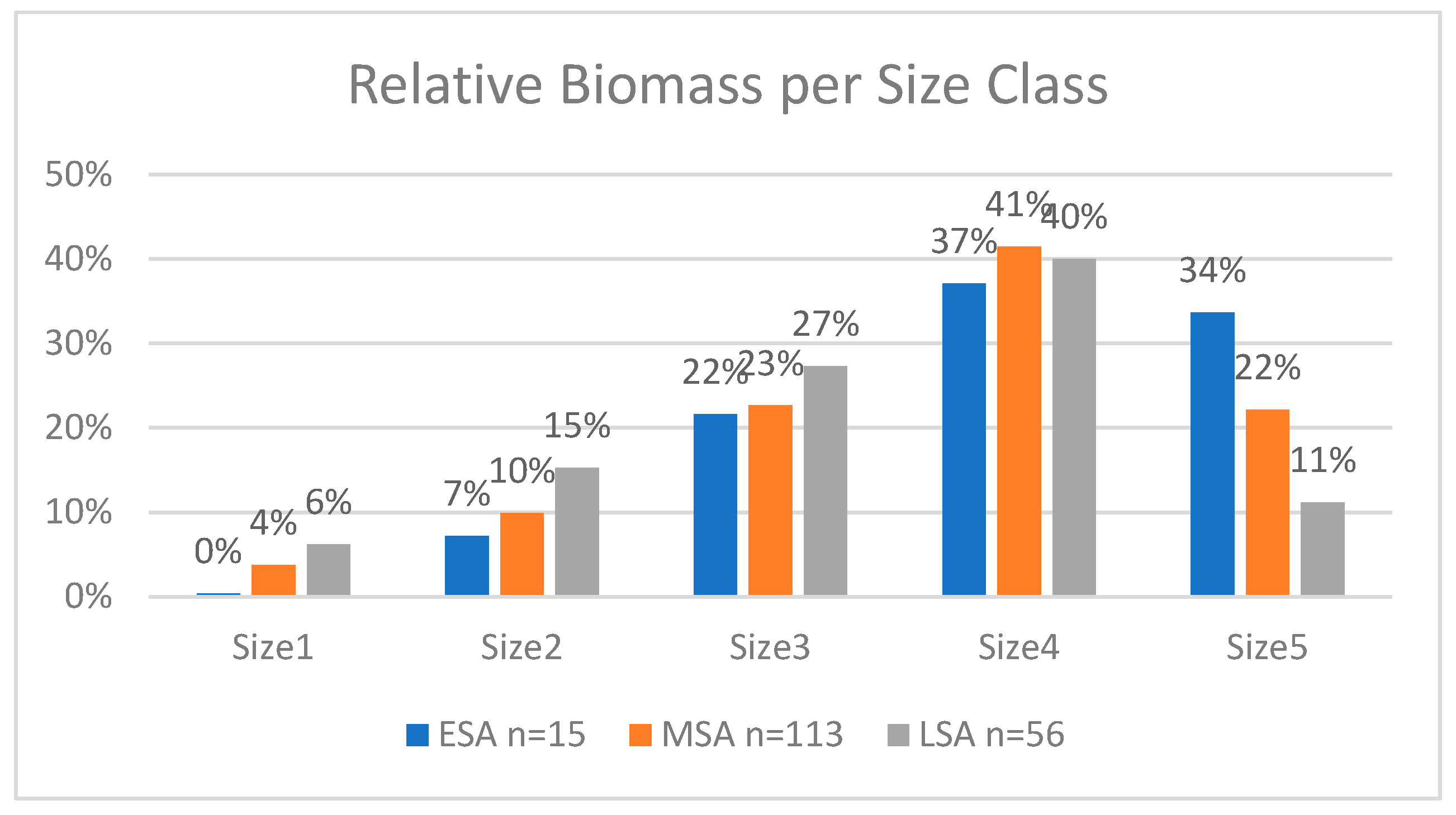

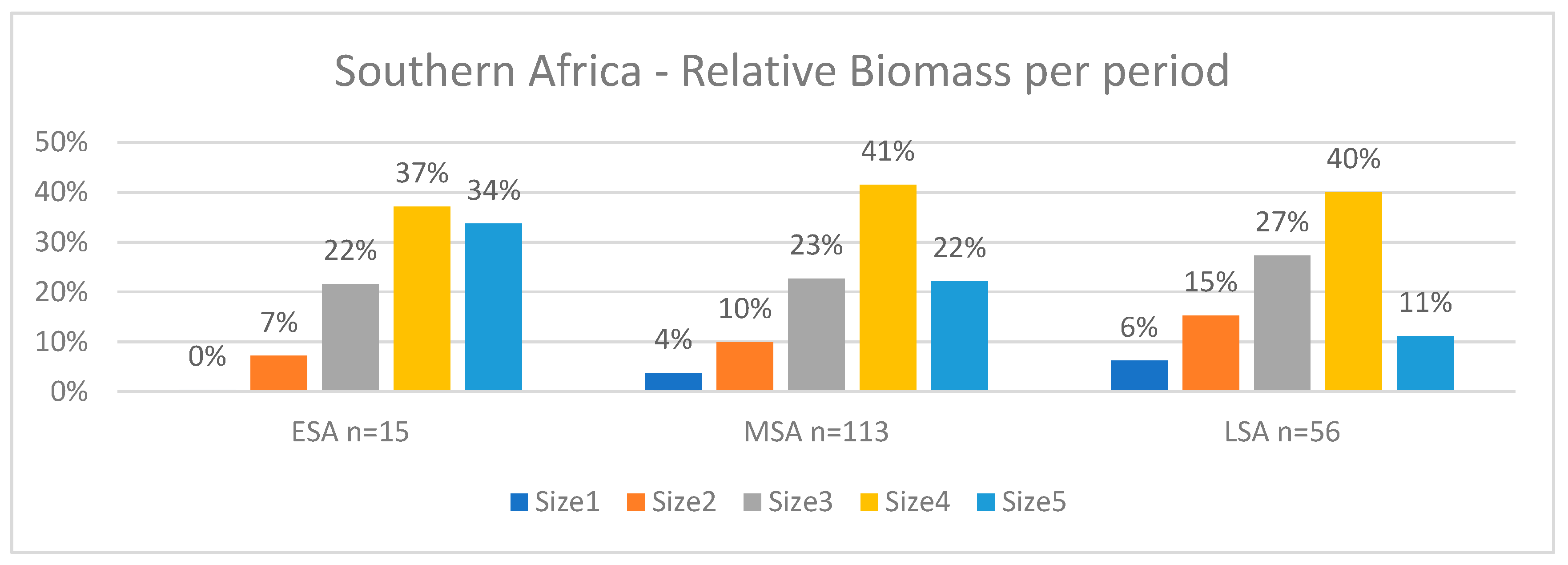

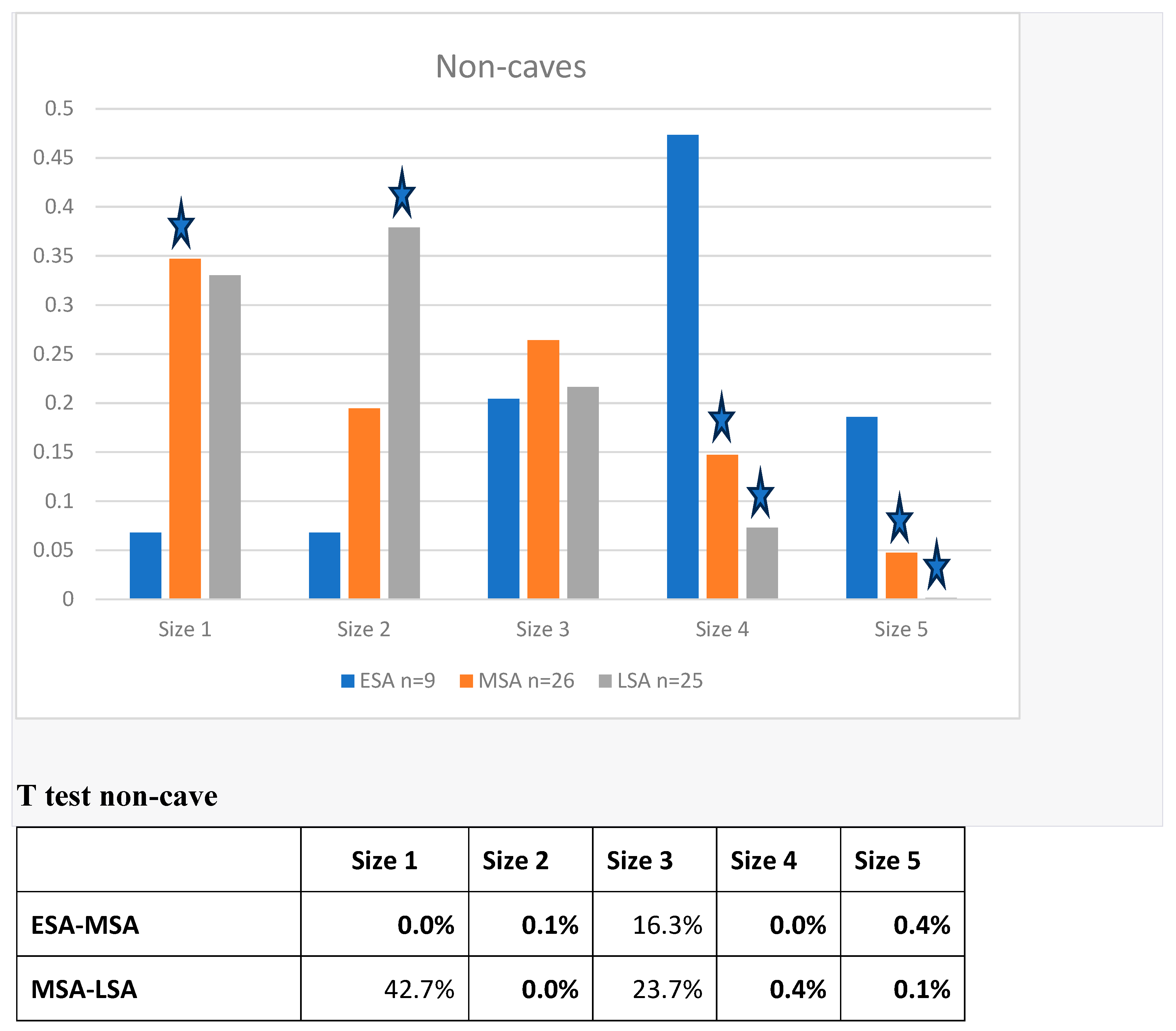

Megafauna extinctions are known from the Late Quaternary. This study analyzes trends in prey size from 184 contexts across 49 archaeological sites in southern Africa to assess changes in prey size during the Pleistocene, including the pre-Late Quaternary transition between the Early Stone Age (ESA) and the Middle Stone Age (MSA). Very large prey (>950kg) accounted for over 34% of the biomass in the ESA, declining to 22% in MSA and 11% in LSA, with a compensatory increase in the contribution of smaller (<295 kg) prey that increased from 7% in the ESA to 37% in the MSA and to 48% in the LSA. These trends persisted even when only non-cave sites were considered. We also hypothesize that targeting fat in prey because of a constraint on protein consumption by humans could have been a causal factor in the decline.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methodology

| Technocomplex | 2012 suggested durations | Revised age estimates | ||

| Median age | Mean age±SD | Most probable duration | ||

| LATER STONE AGE | ||||

| ceramic final Later Stone Age | <2 ka | AD 774 | AD 795± 698 | AD 1493-97 |

| final Later Stone Age | 0.1-4 ka | 546 BC | 658 BC±1290 | AD 632-1948 BC |

| Wilton | 4-8 ka | 4387 BC | 4260 BC±1574 | 2686-5834 BC |

| Oakhurst | 7-12 ka | 8814 BC | 8797 BC±2042 | 6755-10839 BC |

| Robberg | 12-18 ka | 13 705 BC | 14 584 BC±3389 | 11 195-17 973 BC |

| early Later Stone Age | 18-40 ka | 25 998 BC | 28 474 BC±8780 | 19 694-37 254 BC |

| MIDDLE STONE AGE | ||||

| final Middle Stone Age | 20-40 ka | 37.7 ka | 38.8 ±8.9 ka | 29.9-47.7 ka |

| post-Howiesons Poort | 45-58 ka | 55.1 ka | 53±6.6 ka | 46.4-59.6 ka |

| Howiesons Poort | 58-66 ka | 62.4 ka | 62.9±11.4 ka | 51.5-74.3 ka |

| Still Bay | 70-77 ka | 75.2 ka | 78.1±10.7 ka | 67.4-88.8 ka |

| Mossel Bay | 77-105 ka | 88.2 ka | 87.9±10.5 ka | 77.4-98.4 ka |

| early Middle Stone Age | 130-300 ka | 206.5 ka | 196.5±70 ka | 126.5-266.5 ka |

| EARLIER STONE AGE | ||||

| Fauresmith | 200-600 ka | 305 ka | 352.6± 118.9 ka | 233.7-471.5 ka |

| Acheulean | 300 ka-1.5 Ma | 770 ka | 834.2± 402.6 | 431.6 ka-1.23 Ma |

| Oldowan | 1.5-2 Ma | 1.61 Ma | 1.63 Ma± 546.5 ka | 1.08-2.18 Ma |

| Period | N sites | N layers | Avg. NISP/layer |

| LSA | 21 | 56 | 550 |

| MSA | 26 | 113 | 933 |

| ESA | 8 | 15 | 1459 |

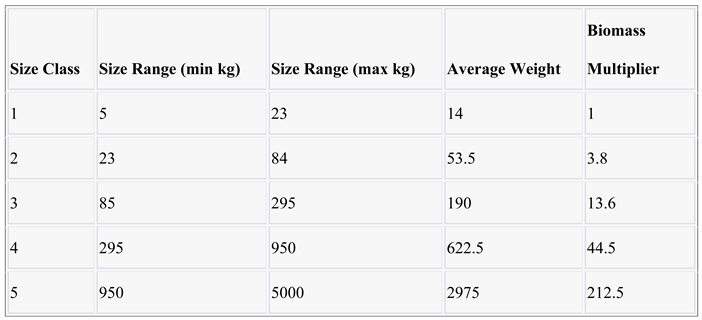

- We calculated the average weight within each size class.

- Taking the average weight of size class 1 as the reference, we divided the average weight of each size class by the average weight of size class 1 to determine the multiplier.

- The average relative presence of each size class within each period was multiplied by the corresponding relative size multiplier.

- To obtain the ratio of each size class within the period, we divided the result from step 3 by the sum of the multiplied size classes for that period.

|

Results

Biomass Contribution Analysis

Discussion

Climate and Prey size Decline

Was Human Predation a Factor in the Decline in Prey Size?

Hunting Very Large Prey

Preferential Hunting of Prime Adults

The Biased Transportation of Fatty Body Parts

A Possible Combined Fat-Targeting and Climatic Influence as a Cause of Prey Size Decline and Evolutionary and Cultural Changes

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, D. 2006. Ahead of the game. Current Anthropology 47(1):89-118.

- Agam, A. and Barkai, R 2016. Not the brain alone: The nutritional potential of elephant heads in Paleolithic sites. Quat Int 406:218-226. [CrossRef]

- Avery, DM. 2019. A fossil history of southern African land mammals: Cambridge University Press.

- Backwell, L. Bradfieldm, J. Carlson, K.J. Jashashvili, T. Wadley, L. and d’Errico F 2018 The antiquity of bow-and-arrow technology: evidence from Middle Stone Age layers at Sibudu Cave. Antiquity 92(362):289-303.

- Barnosky, AD. Koch, PL. Feranec, R.S. Wing, S.L. and Shabel AB 2004. Assessing the causes of Late Pleistocene extinctions on the continents. Science 306(5693):70-75. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dor, M. and Barkai, R 2020. The importance of large prey animals during the Pleistocene and the implications of their extinction on the use of dietary ethnographic analogies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 59:101192. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dor, M. and Barkai, R 2023 The Evolution of Paleolithic Hunting Weapons: A Response to Declining Prey Size. Quaternary 6(3):46. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dor, M. Gopher, A. and Barkai, R 2016 Neandertals’ large lower thorax may represent adaptation to high protein diet. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 160(3):367-378. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dor, M. Gopher, A. Hershkovitz, I. and Barkai, R 2011. Man the fat hunter: The demise of Homo erectus and the emergence of a new hominin lineage in the Middle Pleistocene (ca. 400 kyr) Levant. PLoS One 6(12):e28689. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E. Eves, H. Robinson, J. and Wilkie, D 2002 Why is eating bushmeat a biodiversity crisis. Conserv Biol Pract 3(1):28-29.

- Bibi, F. and Cantalapiedra, J.L 2023. Plio-Pleistocene African megaherbivore losses associated with community biomass restructuring. Science 380(6649):1076-1080. [CrossRef]

- Bilsborough, S. and Mann, N 2006. A review of issues of dietary protein intake in humans. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 16(2):129-152. [CrossRef]

- Blasco, R. and Fernández Peris, J 2012 A uniquely broad spectrum diet during the Middle Pleistocene at Bolomor Cave (Valencia, Spain). Quat Int 252:16-31. [CrossRef]

- Blasco, R. Rosell, J. Arilla, M. Margalida, A. Villalba, D. Gopher, A. and Barkai, R 2019. Bone marrow storage and delayed consumption at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel (420 to 200 ka). Science Advances 5(10):eaav9822. [CrossRef]

- Bodmer, R.E. Eisenberg, J.F. and Redford, K.H 1997. Hunting and the likelihood of extinction of Amazonian mammals: Caza y Probabilidad de Extinción de Mamiferos Amazónicos. Conservation Biology 11(2):460-466. [CrossRef]

- Bridgland, DR. Field, M.H. Holmes, J.A. McNabb, J. Preece, R.C. Selby, I. Wymer ,J.J. Boreham, S. Irving, B.G. and Parfitt, S.A 1999. Middle Pleistocene interglacial Thames–Medway deposits at Clacton-on-Sea, England: reconsideration of the biostratigraphical and environmental context of the type Clactonian Palaeolithic industry. Quat Sci Rev 18(1):109-146. [CrossRef]

- Broughton, J.M. Cannon, M.D. Bayham, F.E. and Byers, D.A 2011. Prey body size and ranking in zooarchaeology: Theory. empirical evidence, and applications from the northern Great Basin. American Antiquity 76(3):403-428. [CrossRef]

- Bunn, HT. 2006. Meat made us human. In: Ungar, P.S. editor. Evolution of the human diet: The known, the unknown, and the unknowable: Oxford University Press. p 191-211.

- Bunn, HT. 2019. Large ungulate mortality profiles and ambush hunting by Acheulean-age hominins at Elandsfontein, Western Cape Province, South Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science 107:40-49. [CrossRef]

- Bunn, H.T. and Ezzo, J.A 1993. Hunting and scavenging by Plio-Pleistocene hominids: Nutritional constraints, archaeological patterns, and behavioural implications. Journal of Archaeological Science 20(4):365-398. [CrossRef]

- Burke, A. 2006. Neanderthal settlement patterns in Crimea: a landscape approach. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 25(4):510-523. [CrossRef]

- Calder, W.A. 1984. Size, function and life history. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Caley, T. Extier ,T. Collins, JA. Schefuß, E. Dupont, L. Malaizé, B. Rossignol, L. Souron, A. McClymont, E.L. and Jimenez-Espejo, F.J 2018. A two-million-year-long hydroclimatic context for hominin evolution in southeastern Africa. Nature 560(7716):76-79. [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, M. Mace, G.M. Jones, K.E. Bielby, J. Bininda-Emonds, O.R. Sechrest, W. Orme, C.D.L. and Purvis, A 2005. Multiple causes of high extinction risk in large mammal species. Science 309(5738):1239-1241. [CrossRef]

- Churchill, SE. 1993. Weapon technology, prey size selection, and hunting methods in modern hunter-gatherers: Implications for hunting in the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic. Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 4(1):11-24. [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.L. and Plug, I 2008. Animal exploitation strategies during the South African Middle Stone Age: howiesons Poort and post-Howiesons Poort fauna from Sibudu cave. Journal of Human Evolution 54(6):886-898. [CrossRef]

- Coote, J. and Shelton, A 1992. Anthropology, Art, and Aesthetics: Clarendon Press.

- Court ,G. 1996. The seal’s own skin game. NATURAL HISTORY 105(8):36-41.

- Dembitzer, J. Barkai, R. Ben-Dor, M. and Meiri, S 2021. Levantine Overkill: 1.5 Million Years of Hunting Down the Body Size Distribution in the Paleolithic Southern Levant. Quat Sci Rev 276(107316). [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Rodrigo, M. Bunn, H.T. Mabulla, A.Z.P. Baquedano, E. Uribelarrea, D. Perez-Gonzalez, A. Gidna, A. Yravedra, J. Diez-Martin, F. Egeland, C.P. et al. 2014. On meat eating and human evolution: A taphonomic analysis of BK4b (Upper Bed II, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania), and its bearing on hominin megafaunal consumption. Quat Int 322:129-152. [CrossRef]

- Enloe, J.G. 1997. Seasonality and age structure in remains of Rangifer tarandus: Magdalenian hunting strategy at Verberie. Anthropozoologica 25(26):95-102.

- Faith, J.T. 2014. Late Pleistocene and Holocene mammal extinctions on continental Africa. Earth-Science Reviews 128:105-121. [CrossRef]

- Faith, J.T. Potts, R. Plummer, T.W. Bishop, L.C. Marean, C.W. and Tryon, CA 2012. New perspectives on middle Pleistocene change in the large mammal faunas of East Africa: Damaliscus hypsodon sp. nov.(Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from Lainyamok, Kenya. Palaeogeogr, Palaeoclimatol, Palaeoecol 361:84-93. [CrossRef]

- Faith, J.T. Rowan, J. and Du, A 2019. Early hominins evolved within non-analog ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences:21478-21483. [CrossRef]

- Faith, J.T. Rowan, J. Du, A. and Barr W.A 2020. The uncertain case for human-driven extinctions prior to Homo sapiens. Quatern Res 96:88-104. [CrossRef]

- Fantinou, A. Perdikis, D.C. Maselou, D. and Lambropoulos, P 2008. Prey killing without consumption: Does Macrolophus pygmaeus show adaptive foraging behaviour? Biol Control 47(2):187-193. [CrossRef]

- Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S. and Niven, L 2009. Hominin Subsistence Patterns During the Middle and Late Paleolithic in Northwestern Europe. In: Hublin, J.J. and Richards, M.P. editors. Evolution of Hominin Diets: Integrating approaches to the study of palaeolithic subsistence. Berlin: Springer Verlag. p 99-111. [CrossRef]

- Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S. and Roebroeks, W 2011. On Neanderthal Subsistence in Last Interglacial Forested Environments in Northern Europe. In: Conard, N.J. and Richter, J. editors. Neanderthal Lifeways, Subsistence and Technology. Dordrecht: Springer. p 61-71. [CrossRef]

- Goren-Inbar, N. Lister, A. Werker, E. and Chech, M 1994. A butchered elephant skull and associated artifacts from the Acheulian site of Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel. Paleorient:99-112.

- Gosling, W.D. Scerri, E.M. and Kaboth-Bahr, S 2022. The climate and vegetation backdrop to hominin evolution in Africa. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 377(1849):20200483.

- Grayson, D.K. and Meltzer, D.J 2015. Revisiting Paleoindian exploitation of extinct North American mammals. Journal of Archaeological Science 56:177-193. [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, K. Oconnell, J.F. Blurton, Jones N.G. Bell, D. Bird, R. Bird, D. Hames, R. Ivey, P. Judge, D. and Kazankov, A 2001. Hunting and nuclear families: Some lessons from the Hadza about mens work. Current Anthropology 42(5):681-709. [CrossRef]

- Haynes G, and Klimowicz J. 2015. Recent elephant-carcass utilization as a basis for interpreting mammoth exploitation. Quat Int 359:19-37. [CrossRef]

- Hempson, G.P. Archibald, S. and Bond, W.J 2015. A continent-wide assessment of the form and intensity of large mammal herbivory in Africa. Science 350(6264):1056-1061. [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.E. DeVault, T.L. and Belant, JL 2019. Cause-specific mortality of the world’s terrestrial vertebrates. Global Ecology and Biogeography 28(5):680-689. [CrossRef]

- Hoffecker, JF. 1999. Neanderthals and modern humans in Eastern Europe. Evol Anthropol 7(4):129-141.

- Jerozolimski, A. and Peres C.A 2003. Bringing home the biggest bacon: a cross-site analysis of the structure of hunter-kill profiles in Neotropical forests. Biological Conservation 111(3):415-425. [CrossRef]

- Jochim, MA. 1981. Strategies for survival: Cultural behavior in an ecological context. NY: Academic Press.

- Kelly, RL. 2013. The lifeways of hunter-gatherers: The foraging spectrum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kier, G. Mutke, J. Dinerstein, E. Ricketts, T.H. Küper, W. Kreft H. and Barthlott, W 2005. Global patterns of plant diversity and floristic knowledge. Journal of Biogeography 32(7):1107-1116. [CrossRef]

- Koch, P.L. and Barnosky, A.D 2006. Late Quaternary Extinctions : State of the Debate. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 37:215-252. [CrossRef]

- Kruuk, H. 1972. Surplus killing by carnivores. J Zool 166(2):233-244. [CrossRef]

- Ledger, HP. 1968. Body composition as a basis for a comparative study of some East African mammals. Symposium of the Zoological Society of London 21:289-310.

- Lee, RB. 1969. Eating Christmas in the Kalahari: American Museum of Natural History New York.

- Linares Matás, G.J. and Yravedra, J 2022. ‘We hunt to share’: social dynamics and very large mammal butchery during the Oldowan–Acheulean transition. World Archaeology:1-31. [CrossRef]

- Lindstedt, S.L. and Boyce, M.S 1985. Seasonality, fasting, endurance, and body size in mammals. American Naturalist 125:873-878. [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M. 2011. Quartz-tipped arrows older than 60 ka: further use-trace evidence from Sibudu, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of archaeological Science 38(8):1918-1930. [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M. 2020. The tip cross-sectional areas of poisoned bone arrowheads from southern Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 33:102477. [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M. 2021. Variation in hunting weaponry for more than 300,000 years: A tip cross-sectional area study of Middle Stone Age points from southern Africa. Quat Sci Rev 264:107021. [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M. Bradfield, J. Caruana, M.V. Makhubela, T.V. Dusseldorp, G.L. Kramers, J.D. and Wurz, S 2022. The Southern African Stone Age Sequence Updated (II). South African Archaeological Bulletin 77(217):172-212.

- Lomolino, M.V. 2023. The ecological and geographic dynamics of extinction: Niche modeling and ecological marginalization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120(3):e2220467120. [CrossRef]

- Lukich, V. and Ecker, M 2022. Pleistocene environments in the southern Kalahari of South Africa. Quat Int 614:50-58. [CrossRef]

- Mackay, A. Armitage SJ. Niespolo, E.M. Sharp, W.D. Stahlschmidt, M.C. Blackwood, A.F. Boyd, K.C. Chase, B.M. Lagle, S.E. and Kaplan, C.F 2022. Environmental influences on human innovation and behavioural diversity in southern Africa 92–80 thousand years ago. Nature Ecology & Evolution 6(4):361-369. [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, D.J. 2020. Overkill, glacial history, and the extinction of North America’s Ice Age megafauna. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences:202015032. [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.L. Gunn, A. and Broughton, E 1985. Surplus killing as exemplified by wolf predation on newborn caribou. Canadian Journal of Zoology 63(2):295-300. [CrossRef]

- Morin, E. 2012. Reassessing Paleolithic subsistence: the Neandertal and modern human Foragers of Saint-Césaire: Cambridge University Press.

- Morin, E. and Ready, E 2013. Foraging goals and transport decisions in western Europe during the Paleolithic and early Holocene. Zooarchaeology and Modern Human Origins: Springer. p 227-269.

- Mutke, J. and Barthlott, W 2005. Patterns of vascular plant diversity at continental to global scales. Biologiske skrifter 55(4):521-531. [CrossRef]

- Owen-Smith, R.N. 2002. Adaptive herbivore ecology: From resources to populations in variable environments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pitts, G.C. and Bullard, T.R 1967. Some interspecific aspects of body composition in mammals. Body Composition in Animals and Man: National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC. p 45-70.

- Potts, R. Dommain, R. Moerman, J.W. Behrensmeyer, A.K. Deino, A.L. Riedl, S. Beverly, E.J. Brown, E.T. Deocampo, D. and Kinyanjui, R 2020. Increased ecological resource variability during a critical transition in hominin evolution. Science advances 6(43):eabc8975. [CrossRef]

- Potts, R. and Faith, J.T 2015. Alternating high and low climate variability: The context of natural selection and speciation in Plio-Pleistocene hominin evolution. Journal of human evolution 87:5-20. [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, M.E. Yuan, J. and Bar-Yosef, O 2009. Resource intensification in the Late Upper Paleolithic: a view from southern China. Journal of Archaeological Science 36(4):1027-1037. [CrossRef]

- Redford, K.H. 1992. The empty forest. Bioscience 42(6):412-422. [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J. Wolf, C, Newsome, T.M. Betts, M.G. Ceballos, G. Courchamp, F. Hayward, M.W. Van Valkenburgh, B. Wallach, A.D. and Worm, B 2019. Are we eating the world’s megafauna to extinction? Conservation Letters 12(3):e12627. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A. Saladie, P. Olle, A. and Carbonell, E 2015. Hominin subsistence and site function of TD10. 1 bone bed level at Gran Dolina site (Atapuerca) during the late Acheulean. J Quat Sci 30(7):679-701. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J. Burjachs, F. Cuenca-Bescós, G. García, N. Van der Made, J. González, A.P. Blain, H-A. Expósito, I. López-García, J.M. and Antón MG 2011. One million years of cultural evolution in a stable environment at Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain). Quat Sci Rev 30(11-12):1396-1412. [CrossRef]

- Rudman, D. Difulco, T.J. Galambos, J.T. Smith, R.B. Salam, A.A. and Warren, W.D 1973. Maximal rates of excretion and synthesis of urea in normal and cirrhotic subjects. J Clin Invest 52:2241-2249.

- Sandom, C. Faurby, S. Sandel, B. and Svenning, J-C 2014. Global late Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climate change. Proc R Soc B: The Royal Society. p 20133254. [CrossRef]

- Scott, L. and Neumann, F.H 2018. Pollen-interpreted palaeoenvironments associated with the Middle and Late Pleistocene peopling of Southern Africa. Quat Int 495:169-184. [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.A. Smith, R.E.E. Lyons, S.K. and Payne, J.L 2018. Body size downgrading of mammals over the late Quaternary. Science 360(6386):310-313. [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.A. Smith, R.E.E Lyons, S.K. Payne, J.L. and Villaseñor, A 2019a. The accelerating influence of humans on mammalian macroecological patterns over the late Quaternary. Quat Sci Rev 211:1-16. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.M. Ruebens, K. Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S. and Steele, T.E 2019b. Subsistence strategies throughout the African Middle Pleistocene: Faunal evidence for behavioral change and continuity across the Earlier to Middle Stone Age transition. Journal of Human Evolution 127:1-20. [CrossRef]

- Speth, J.D. 1983. Bison kills and Bone counts: Decision making by ancient hunters. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [CrossRef]

- Speth, J.D. 2010. Big-Game Hunting: Protein, Fat, or Politics? The Paleoanthropology and Archaeology of Big-Game Hunting: Springer. p 149-161.

- Speth, J.D. 2012. Middle Palaeolithic subsistence in the Near East. Before Farming 2012(2):1-45. [CrossRef]

- Speth, J.D. and Spielmann K.A 1983. Energy source, protein metabolism, and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 2:1-31. [CrossRef]

- Stiner, M. 2012. Competition theory and the case for Pleistocene Hominin-Carnivore Co-evolution. J Taphon 10(3):129-145.

- Stiner, M.C. 1990. The use of mortality patterns in archaeological studies of hominid predatory adaptations. Journal of anthropological archaeology 9(4):305-351. [CrossRef]

- Stiner, M.C. Gopher, A. and Barkai, R 2011. Hearth-side socioeconomics, hunting and paleoecology during the late Lower Paleolithic at Qesem Cave, Israel. Journal of human evolution 60:213-233. [CrossRef]

- Stirling, I. and Guravich, D 1998. Polar Bears: University of Michigan Press.

- Surovell, T.A. and Waguespack, N.M 2009. Human prey choice in the Late Pleistocene and its relation to megafaunal extinctions. In: Haynes, G. editor. American megafaunal extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene: Springer Dordrecht. p 77-105.

- Tanner, A. 2014. Bringing home animals: Mistissini hunters of northern Quebec. Bringing Home Animals: Memorial University Press.

- Taylor Lemoine, R. Buitenwerf, R. and Svenning, J-C 2023. Megafauna extinctions in the late-Quaternary are linked to human range expansion, not climate change. Anthropocene. [CrossRef]

- Tindale, NB. 1972. The Pitjandjara. In: Bicchieri MG, editor. Hunters and gatherers today. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p 217-268.

- Trauth, M.H. Maslin, M.A. Deino, A.L. Junginger, A. Lesoloyia, M. Odada, E.O. Olago, D.O. Olaka, L.A. Strecker, M.R. and Tiedemann, R 2010. Human evolution in a variable environment: the amplifier lakes of Eastern Africa. Quat Sci Rev 29(23-24):2981-2988. [CrossRef]

- Wadley, L. 2010. Were snares and traps used in the Middle Stone Age and does it matter? A review and a case study from Sibudu, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution 58(2):179-192. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, J. Schoville, B.J. Brown, K.S, and Chazan, M 2012. Evidence for early hafted hunting technology. Science 338(6109):942-946. [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.M. and Marlowe, F.W 2013. Household and kin provisioning by Hadza men. Hum Nat 24(3):280-317. [CrossRef]

- Wroe, S. Field, J.H. Archer, M. Grayson, D.K. Price, G.J. Louys, J. Faith, J.T. Webb, G.E. Davidson, I. and Mooney, S.D 2013. Climate change frames debate over the extinction of megafauna in Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110(22):8777-8781. [CrossRef]

- Wurz, S. 2013. Technological trends in the Middle Stone Age of South Africa between MIS 7 and MIS 3. Current Anthropology 54(S8):S305-S319. [CrossRef]

- Wurz, S. 2014. Southern and east African Middle Stone Age: geography and culture. Encyclopedia of global archaeology 2014:6890-6912.

- Yravedra, J. 2001. Zooarqueología de la Península Ibérica: implicaciones tafonómicas y paleoecológicas en el debate de los homínidos del Pleistoceno Medio-Superior. BAR Int Ser 979.

- Ziegler, M. Simon, M.H. Hall, I.R. Barker, S. Stringer, C. and Zahn, R 2013. Development of Middle Stone Age innovation linked to rapid climate change. Nature communications 4(1):1905. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).