1. Introduction

Elevated levels of glucose have a significant impact on maternal and fetal interactions as well as on the production of essential hormones that support pregnancy [

1]. Studies have shown that high glucose levels are linked to a decrease in the number of active mitochondria and reduced ATP production, which can negatively affect trophoblast function [

2,

3]. This may result in an increased incidence of pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, congenital malformations, and miscarriage, posing significant health risks to both pregnant women and fetuses [

4].

The placenta is a highly metabolically active organ fulfilling the bioenergetic and biosynthetic needs to support its own rapid growth and that of the fetus [

5]. Placental structures consist of specialized epithelial cell types known as trophoblast cells, which are located at the maternal-fetal interface [

6,

7]. Human trophoblasts arise from the trophectoderm, which, after implantation, differentiates into cytotrophoblast (CT), villous syncytiotrophoblast (VST), and extravillous trophoblast (EVT) cells [

6,

7]. VST cells form a multinucleated layer on the placental surface and play key roles in hormone secretion, nutrient transport, gas exchange, immunotolerance, and pathogen resistance [

8,

9]. EVT cells migrate, invade, and embed placental villi into the maternal decidua to anchor the placenta [

10,

11].

Trophoblasts use glucose as the primary energy substrate. In the absence of appreciable gluconeogenesis, placental glucose transport is the only supply for the fetus [

12]. In trophoblasts, glucose is metabolized through a multistep process. The first step, glycolysis, occurs in the cytoplasm and involves the conversion of one glucose molecule to two pyruvate molecules, resulting in a net gain of two ATP molecules [

1]. Under anaerobic conditions, pyruvate can be reversibly converted to lactate by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Pyruvate is typically transported into the mitochondria for further degradation in the TCA cycle, where it is oxidized to acetyl-CoA [

5]. This process occurs iteratively, generating one ATP molecule for each acetyl-CoA molecule produced, but also generating reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH+H

+) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH

2). These reduced cofactors act as electron carriers to generate a proton gradient that drives ATP production through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in the electron transport chain [

5].

Cellular glucose metabolism is regulated by complex signaling pathways that involve various biological factors. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1), a multifunctional cytokine, is one of these factors [

13]. It operates through the SMAD2/SMAD3 pathway to regulate the expression of genes involved in different cellular functions. According to previous research, TGFβ1 regulates the activity of essential enzymes and transporters, such as GLUT1 and the hexokinase HK2, which play crucial roles in glucose uptake and glycolysis in different cell types [

13]. However, TGFβ1 is also known to induce metabolic reprogramming by promoting mitochondrial ATP production in stromal cells [

14]. TGFβ1 expression is detected at the human maternal–fetal interface during early pregnancy, playing crucial roles in regulating immune cell function and maintaining immune homeostasis [

15]. Moreover, TGFβ1 plays significant roles in the regulation of trophoblast function, particularly trophoblast invasion and differentiation [

15].

Transcription factors, such as hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), are considered energy sensors that play significant roles in regulating cellular metabolism [

16,

17,

18]. HIFs are transcriptional heterodimer complexes, consisting of an inducible α subunit (HIF1α, HIF2α and HIF3α) and constitutively expressed β subunits [

16]. Under hypoxic conditions, the α/ꞵ heterodimer binds to the hypoxia response elements (HREs) of the target genes. Under normal oxygen levels, proline residues in HIF1α and HIF2α are hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) proteins, allowing their recognition by a ubiquitin ligase leading to proteasomal degradation [

17]. Studies have demonstrated that HIF1α is significantly expressed in the low-oxygen environment of the placenta during early gestation where it plays a crucial role in placental development and function [

18]. However, sustained HIF1α expression after 9 weeks of gestation can lead to trophoblast cells failing to differentiate from a proliferative to an invasive phenotype, shallow invasion of trophoblasts, and insufficient myometrial spiral artery transformation, which are strongly associated with pregnancy complications [

19]. On the other hand, AMPK functions as a primary regulator of energy metabolism. AMPK is activated in response to energy stress, which is characterized by increased levels of cellular AMP, ADP, or Ca

2+ and a decline in ATP production [

20]. Research has shown that AMPK plays a crucial role in maintaining the balance between trophoblast invasion and survival by controlling glucose metabolism [

21]. Furthermore, elevated blood glucose levels trigger AMPK activation in the placentas of pregnant women with gestational diabetes, indicating that AMPK plays a key role in regulating glucose metabolism to maintain energy balance [

22]. Finally, PPARγ is a crucial nuclear hormone receptor whose action is mediated through the heterodimerization of PPARγ with the retinoid-X-receptor (RXR) upon activation. According to previous studies, PPARγ is a crucial component for proper progression of pregnancy, as it encompasses placental formation, fetal development, and labor [

23]. Additionally, PPARγ activators, which include fatty acids and lipid metabolites, are elevated in normal pregnancies, suggesting that PPARγ may play a part in regulating maternal metabolism and immune functions during pregnancy [

24].

Studies suggest that HIF1α promotes glycolysis through regulation of the glycolytic enzymes hexokinase 2 (HK2) and pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), and the glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3, facilitating cellular glucose uptake [

25]. Furthermore, glycolysis and glucose uptake affect the stability and activation of HIF1α in human pharyngeal carcinoma and fibrosarcoma cells and rat cardiac myocytes [

25]. Conversely, AMPK activation leads to the activation of catabolic pathways that generate ATP while simultaneously inhibiting anabolic, biosynthetic pathways that consume ATP [

20]. When PPARγ is activated, it initiates a series of events that ultimately lead to the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolisms. Specifically, PPARγ regulates genes associated with glucose transporters, mitochondrial biogenesis, fat storage, and fat transport [

26].

The interactions between high-glucose levels and TGFβ1 have been investigated in various cell lines, and the results have demonstrated that TGFβ1 signaling affects glucose metabolism by increasing glucose uptake, controlling glycolytic enzymes, altering lactate production, and influencing oxidative phosphorylation [

13,

27]. However, there is no evidence regarding the effect of TGFβ1 on energy metabolism in trophoblast cells. Precisely, the interplay between TGFβ1 and the energy-sensing regulators: HIF1α, PPARγ, and AMPK.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the potential regulatory function of TGFβ1 in counteracting metabolic disruptions caused by high-glucose conditions in trophoblast cells. By examining the expression or activation levels of SMAD2, HIF1α, PPARγ, AMPK, GLUT1, GLUT3, and specific mitochondrial respiratory chain protein subunits, as well as assessing the levels of ATP and lactate production, we aimed to explore the extent to which TGFβ1 may play a role in regulating the effects of high-glucose conditions on trophoblast cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Cell culture media and reagents such as fetal bovine serum (FBS; #090-110) and Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, #311-512-CL) were obtained from Wisent (St-Bruno, QC, Canada). Cell culture plates and flasks were purchased from Corning Inc, (Corning, NY, USA). TGFβ1 cytokine was purchased from Peprotech (Montreal, QC, Canada). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and monoclonal peroxidase-conjugated mouse anti-β-actin antibody were from Sigma Chemical Company (Oakville, ON, Canada). Protease and phosphatase inhibitors cocktail EDTA-free and the Pierce™ NE-PER™ nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagent were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). VH 298, a cell-permeant inhibitor of von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor (VHL; #700410) was from Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Abs) targeting PPARγ (#2435), HIF1α (#36169), p-SMAD2 (pS465/467; #3108), SMAD2 (#5359), p-AMPKα (pThr172; #2531), AMPK (#2532), and Lamin B1 (#13435), GLUT1 (#12939) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The Total OXPHOS Rodent WB Antibody Cocktail (ab110413) was sourced from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), and the mouse monoclonal GLUT3 Abs (Sc-74399) from Santa Cruz biotechnology (Cambridge, MA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal β-tubulin Abs were purchased from Abcam (#Ab6046; Waltham, MA, USA). All Abs were used at a 1:1000 dilution except for GLUT3 (1:500) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution containing 5% BSA (PBS/5% BSA). The horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and goat anti-mousse IgG Abs (1:5000 dilution) were obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Mississauga, ON, Canada). The chemiluminescence detection kit was purchased from FroggaBio (#CCH365; Concord, ON, Canada).

2.2. Cell Culture

The human placental choriocarcinoma JEG-3 cell line (ATCC #HTB-36; Rockville, MD, USA) was grown in RPMI-1640 cell culture media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, and 50 μg/mL gentamicin. Cell culture workflow, cell passaging, and cell subculturing were performed as previously described [

8,

9,

10]. For further experimental needs, cells were detached using trypsin, counted, and subcultured in 24- or 96-well cell culture plates. All experiments were restricted to using JEG-3 cells from passages 8 to 15 to avoid any changes in cell behavior during the study.

2.3. ATP Detection

The metabolic activity of JEG-3 cells was evaluated via quantitative measurement of total cellular ATP levels and achieved using an ATP detection assay kit (#700410; from Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Briefly, at the indicated time points, cells were lysed in ATP sample buffer, and properly diluted to ensure the luminescence was within the linear range of the ATP standard curve. Cell lysates were incubated with a mixture containing D-Luciferin and Luciferase at room temperature for 20 min. The luminescence intensity was recorded at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy HT; BioTek® Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). According to the manufacturer protocol, total ATP concentration, expressed in nM, was determined using the ATP detection standard.

2.4. Lactate Detection

The glycolytic activity of JEG-3 cells was determined using the Lactate-Glo Assay (#J5021, from Promega, Madison, WI, USA). In this bioluminescent assay, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) utilizes extracellular lactate, derived from glycolysis, and NAD+ to produce pyruvate and NADH. In the presence of NADH, a pro-luciferin reductase substrate is converted by the reductase to luciferin, which is then used in a luciferase reaction to produce light. The light emitted in this reaction is directly proportional to the concentration of lactate in the culture medium sample. Briefly, at the indicated time points, 10 µL of cell-free culture medium samples were firstly diluted with 490 µL HBSS. Then, 50 µL diluted medium sample and 25 µL lactate detection reagent was mixed in 96-well plates and incubated for 60 min at room temperature. The luminescence intensity was recorded at 570 nm using the BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader. According to the technical manual, relative light unit and lactate titration curve were used to determine lactate concentration, expressed in nM.

2.5. Subcellular Fractionation

JEG-3 cells at a cell density of 450 × 103 cells/2 mL/well were seeded into 6-well plates in 10 % FBS-RPMI-1640 cell culture media overnight. Cells were starved without FBS overnight, and then cultured for 24 h. After incubation period, cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extracts were prepared according to the instructions of the Pierce™ NE-PER® nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (#78835) and analyzed by western blot.

2.6. Proteins Immunodetection

JEG-3 cells were seeded for 24 h at two different cell densities, 450 × 10

3 cells/2 mL/well into 6-well plates and 150 × 10

3 cells/500 μL/well into 24-well plates. Cells were starved in cell culture media without FBS overnight. Cells were then used in different experimental conditions. At the indicated time points, cells protein samples were resolved using SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, and then transferred into PVDF membranes as described [

8,

9,

10]. Blots were probed overnight at 4 °C with rabbit polyclonal primary Abs (1:1000 dilution) against total (t) or phosphorylated (p) forms of SMAD2, HIF1α, PPARγ, GLUT1, and AMPK proteins; and a mix of mousse polyclonal primary Abs against mitochondrial respiratory chain protein subunits, and mouse monoclonal Abs against GLUT3. Membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-mousse IgG Abs at 1:5000 dilution for 1 hour at room temperature. β-actin (1:40000 dilution), and β-tubulin and Lamin B1 (1:1000 dilutions) were used as loading controls. The detected proteins were visualized as described [

8,

9,

10].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data collection and statistical analysis were performed using Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA), as previously described [

8,

9,

10]. Briefly, data from at least three independent experiments were expressed as mean ± SD. A one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-tests were performed to assess the statistical correlation of data between groups. Tukey tests were performed to analyze the null hypothesis of no difference of means between two groups. A threshold of significance at

p ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

4. Discussion

The process of placental transport and metabolism of nutrients essential for fetal development is metabolically expensive and requires abundant oxygen consumption and ATP production, primarily synthesized through glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation [

34]. Glucose is principally the energy source for the placenta and fetus, and all the glucose supplied to the placenta-fetal unit originates from the maternal glucose pool, which is produced by maternal gluconeogenesis or ingested through the pregnant woman's diet [

35]. However, elevated glucose levels at the fetal-maternal interface have been linked to poor maternal and perinatal outcomes. In fact, hyperglycemia is the most common medical condition affecting pregnancy, and its occurrence is rising globally in tandem with the dual epidemics of obesity and diabetes [

36]. The potential outcomes of hyperglycemia in pregnancies with diabetes mellitus (DM) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) include preterm birth, preeclampsia, and stillbirth. However, fetal overgrowth and macrosomia are the most common adverse effects [

37]. Lipid metabolism is also altered in placentas from DM and GDM women. Thus, it is proposed that maternal hyperglycemia is a contributing factor to fetal macrosomia by enhancing substrate availability to the fetus, and stimulating adipose tissue formation and excessive growth [

38].

Hyperglycemia can impair spiral artery remodeling, increasing the risk of pregnancy complications, such as miscarriage, cardiac and renal malformations, and rare neural conditions, such as sacral agenesis [

2]. It negatively affects EVT cell function in uterine spiral artery remodeling by disrupting trophoblast proliferation, migration, invasion, hormone and angiogenic factor release, and communication between trophoblasts and immune cells [

2].

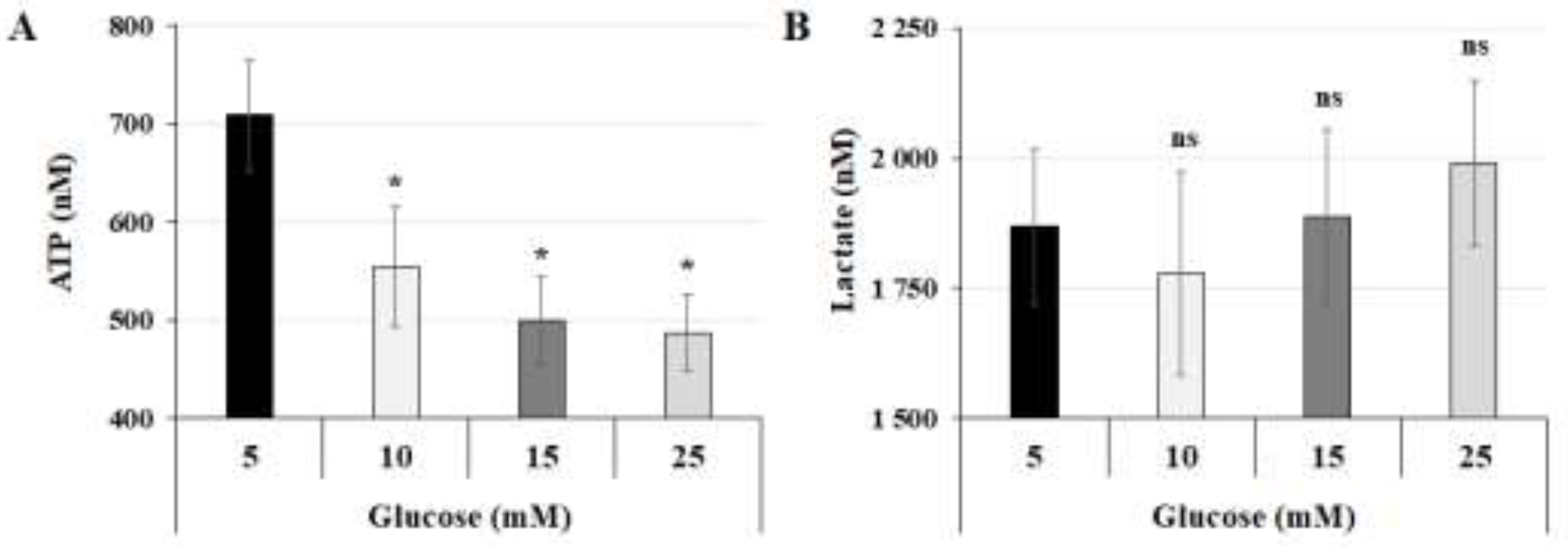

In this study, we showed that high-glucose concentrations induce alterations in the regulation of energy metabolism in human trophoblast JEG-3 cells, a model of placental EVT cells. Notably, these

in vitro hyperglycemic conditions reduce ATP synthesis and mitochondrial function without affecting lactate production via the glycolytic pathway. Previous research on trophoblast cells from normal and GDM placentas shows that a high glucose concentration (25 mM) significantly reduces the glycolytic capacity and ATP production of cytotrophoblasts, particularly EVT cells [

3]. EVT cells are noted for higher oxygen consumption and glycolysis compared to fusogenic VST cells. Additionally, the mitochondrial respiratory capacity of VST cells from both normal and GDM placentas remains unaffected by glucose level variations. However, VST cells from GDM placentas exhibit significantly lower levels of β-hCG and other syncytialization markers, including GCM1 and syncytin-1, compared to those from normal placentas [

3]. According to the results of the microarray transcriptome analysis, DM is associated with alterations in gene expression at critical stages of placental energy metabolism, with 67 % of the changes affecting lipid pathways and 9 % affecting glucose pathways [

39]. Furthermore, pregnant women with GDM show preferential activation of lipid genes [

39]. Human trophoblast BeWo cells, a model of placental VST cells, were cultured in 5- or 25-mM glucose to identify the functional biochemical pathways perturbed by high glucose levels [

40]. Among the pathway networks affected by high-glucose conditions, this study highlighted the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) cascade, glucose metabolism, peroxisomal lipid metabolism, phospholipid metabolism, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/SMAD2 cascade, regulation of lipid metabolism by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), and cellular response to stress [

40].

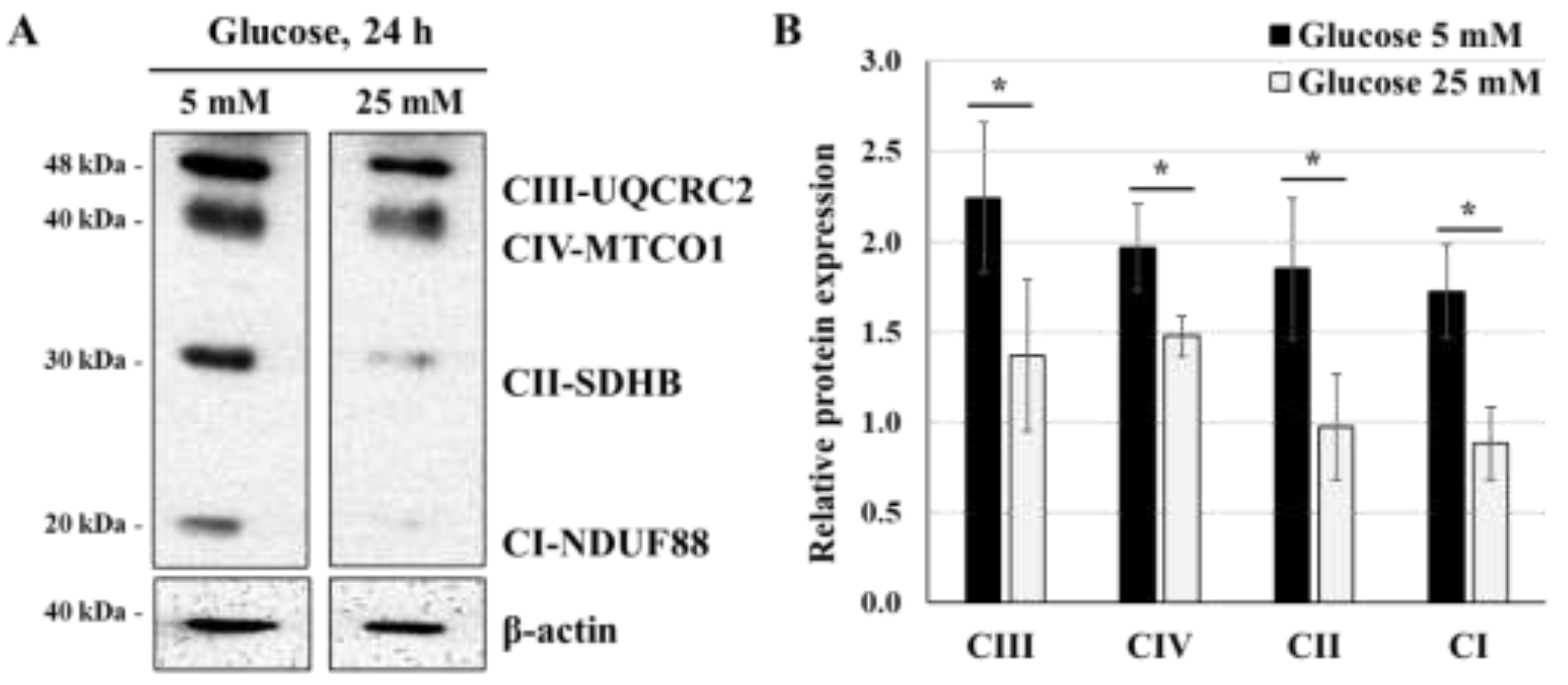

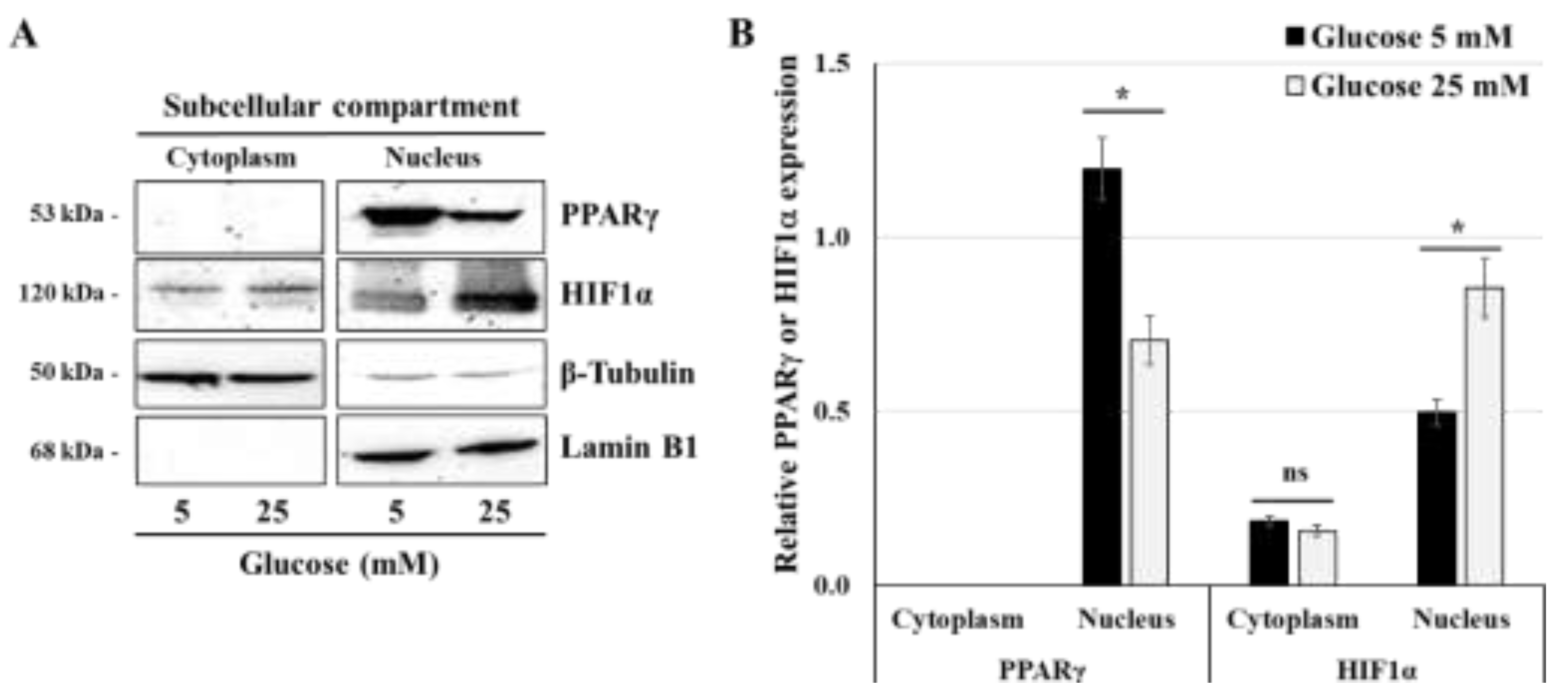

Although the precise mechanism by which high glucose concentrations in EVT suppress metabolic activity and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation remains largely unknown, our results suggest that these changes may be mediated by reduced expression levels of mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins and PPARγ, coinciding with increased HIF1α expression.

Then, because a critical role TGFβ1 play in multiple aspects of cell metabolism [

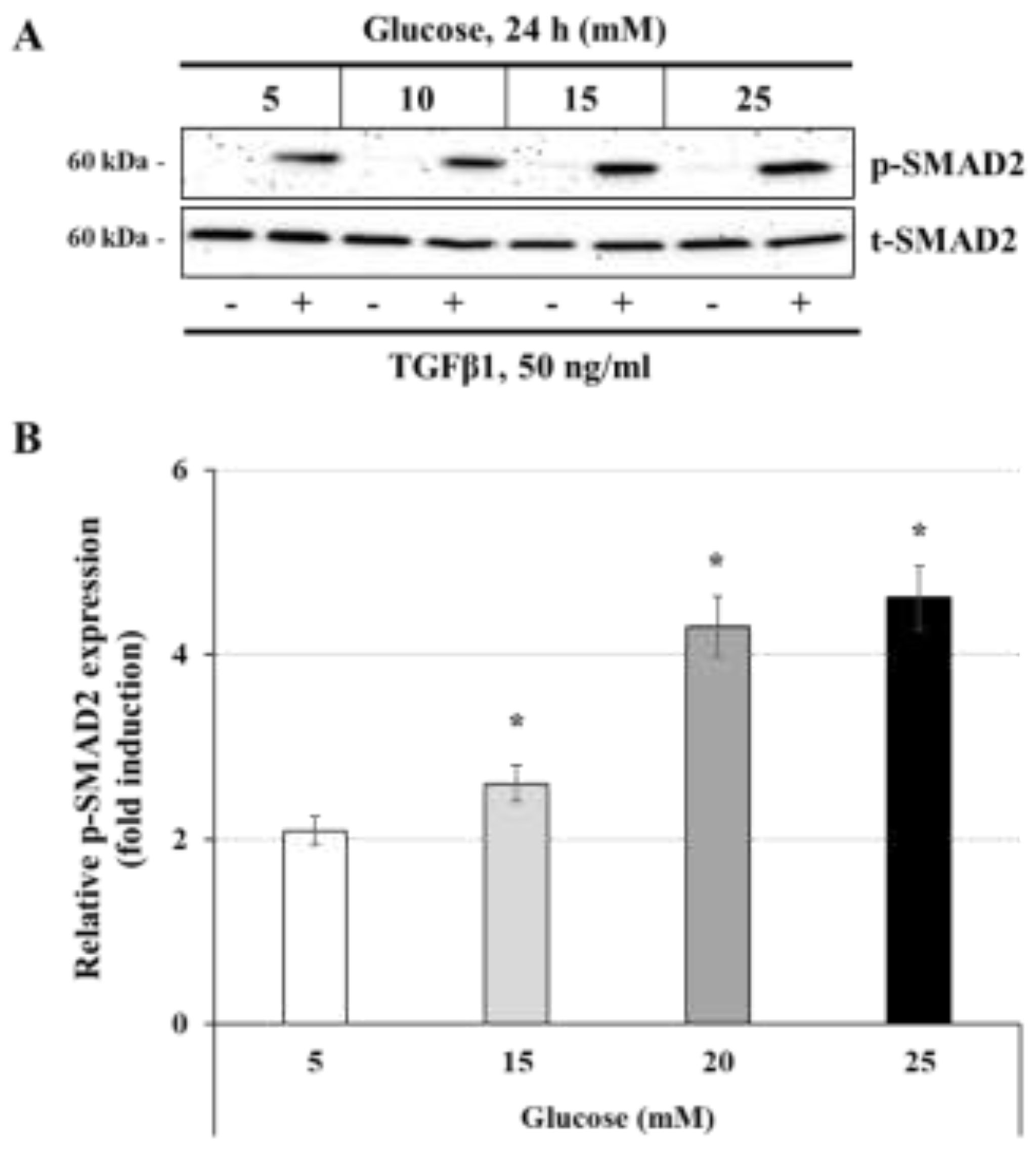

13], we hypothesized that this cytokine regulates energy metabolism in trophoblast cells by influencing the expression of key energy metabolic sensors, such as HIF1α, PPARγ, and AMPK, under high-glucose conditions. Our results showed that TGFβ1 stimulation led to increased levels of SMAD2 phosphorylation when the cells were incubated in high-glucose conditions (15 mM and 25 mM). This outcome aligns with prior research demonstrating that prolonged exposure to high glucose levels triggers a range of physiological and pathophysiological changes, activating various signaling pathways that often disrupt the function of cells, tissues, and organ systems [

41]. Hyperglycemia can activate protein kinase C (PKC) in malignant cells, leading to the activation of various pathways including Akt, TGFβ/SMADs, and NFκB. These pathways work together to control cancer cell metabolism and behavior such as proliferation, migration, invasion, and recurrence [

42]. As research suggests, elevated glucose levels have been found to boost the cell membrane concentrations of TβRI and TβRII, and to promote the activation of latent TGFβ by matrix metalloproteinases [

13]. This, in turn, triggers the Akt-mTOR pathway and leads to enlargement of fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Furthermore, TGFβ signaling plays a role in regulating other components of the glycolytic pathway [

13].

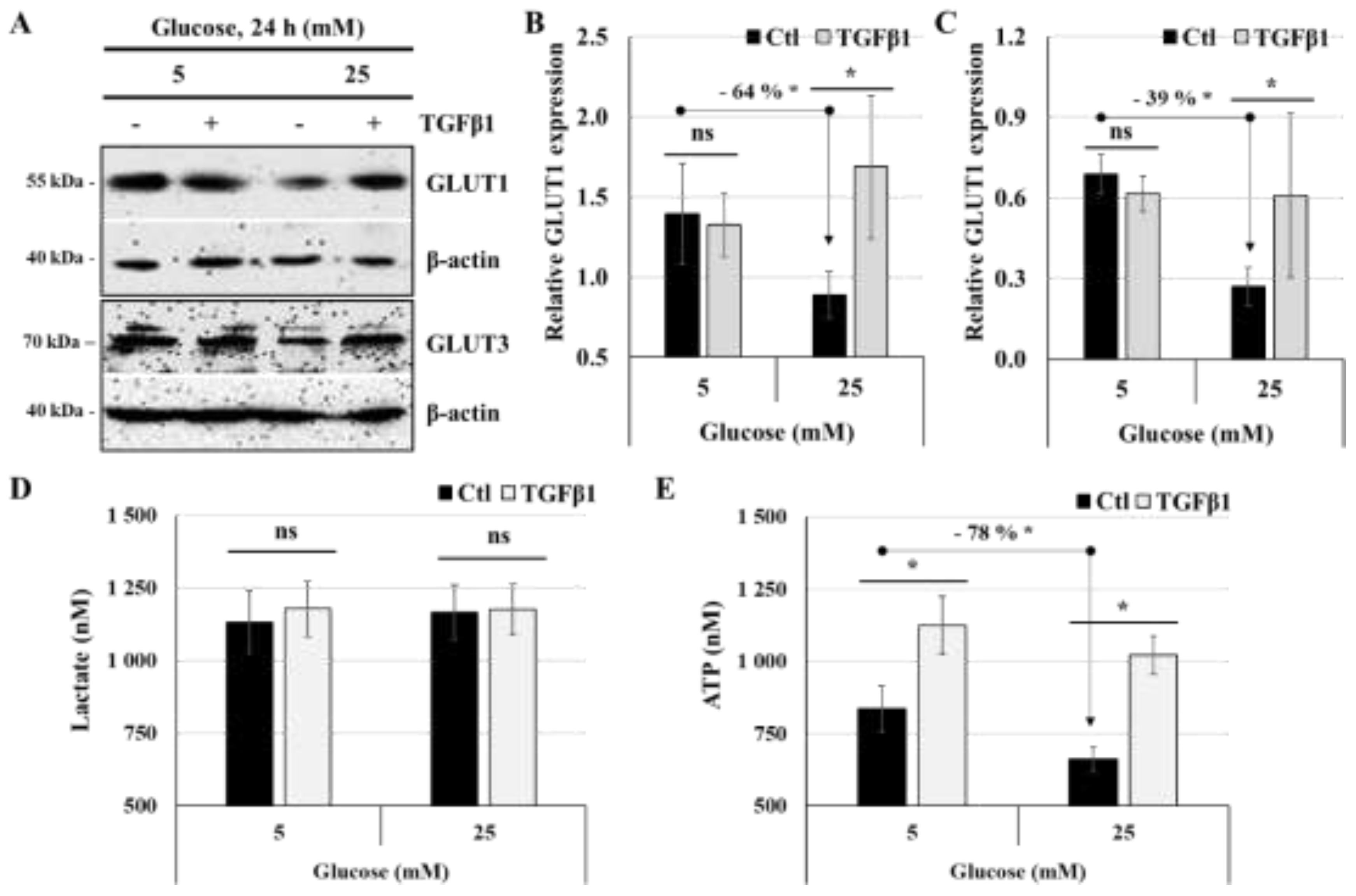

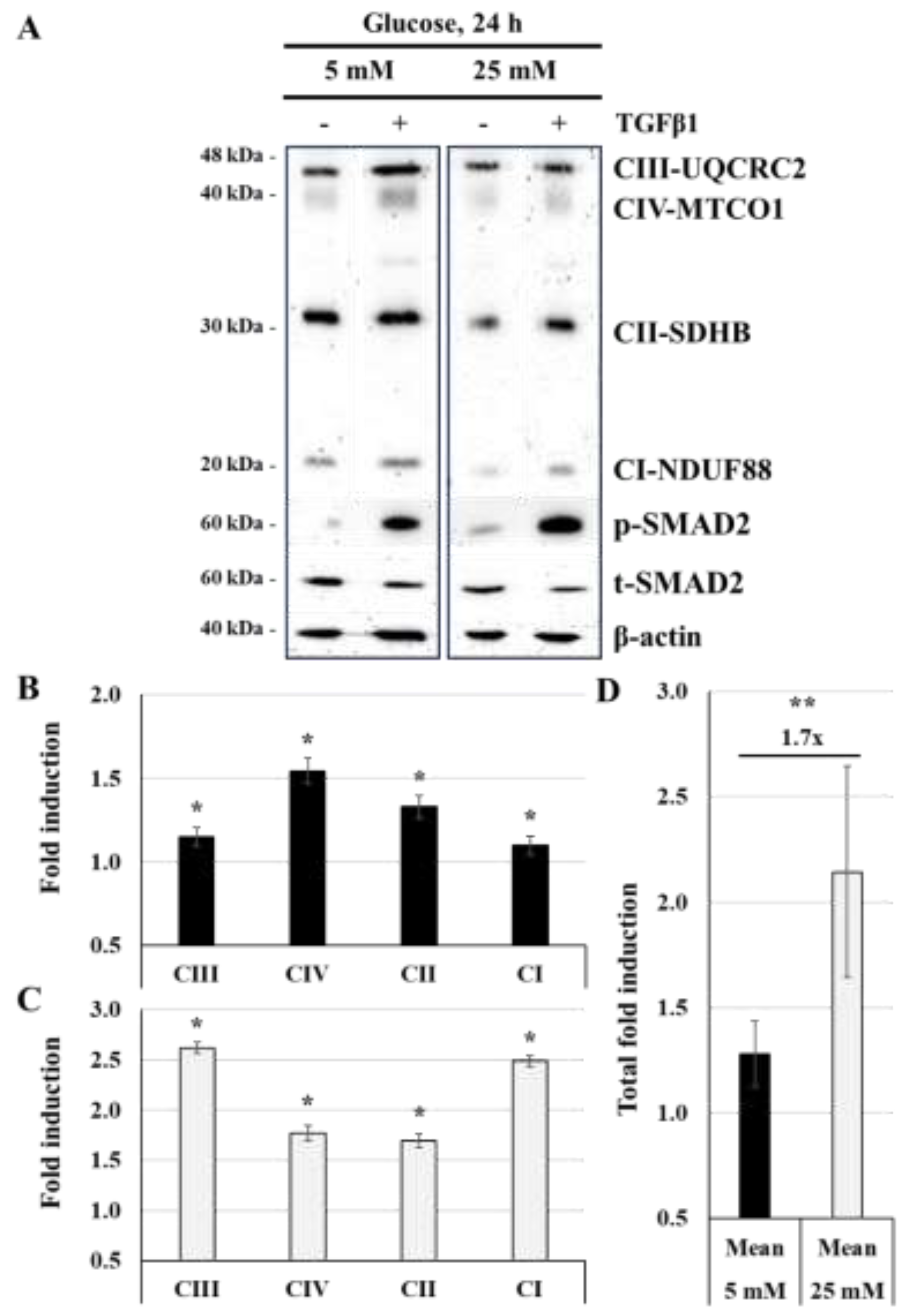

Our findings indicated that TGFβ1 restores the energy homeostasis of JEG-3 cells under high-glucose stress conditions. Specifically, TGFβ1 treatment enhances ATP production and mitochondrial respiratory chain protein expression under high-glucose concentrations. While stressing high-glucose condition does not affect lactate production, even after TGFβ1 stimulation, we found that TGFβ1 restore the expression levels of GLUT1 and GLUT3, at levels like that in normal-glucose conditions. These results are consistent with previous research showing that TGFβ1 improve the activity/expression of GLUT1 and HK2 in different cell types, thus favoring glucose capture and energy production [

13]. Moreover, it was established that TGFβ1 is responsible for significant metabolic reprogramming in normal and cancerous cells by promoting mitochondrial ATP production [

14], and increasing mitochondrial activity, as evidenced by the higher mitochondrial DNA copy number and ROS levels [

43]. Furthermore, TGFβ1 activates the AMPK pathway, which promotes fatty acid oxidation and inhibits anabolic pathways [

44]. It is proposed that this effect on mitochondrial metabolism can help normal and cancer cells maintain their energy requirements and metabolic adaptations through metabolic stressing conditions.

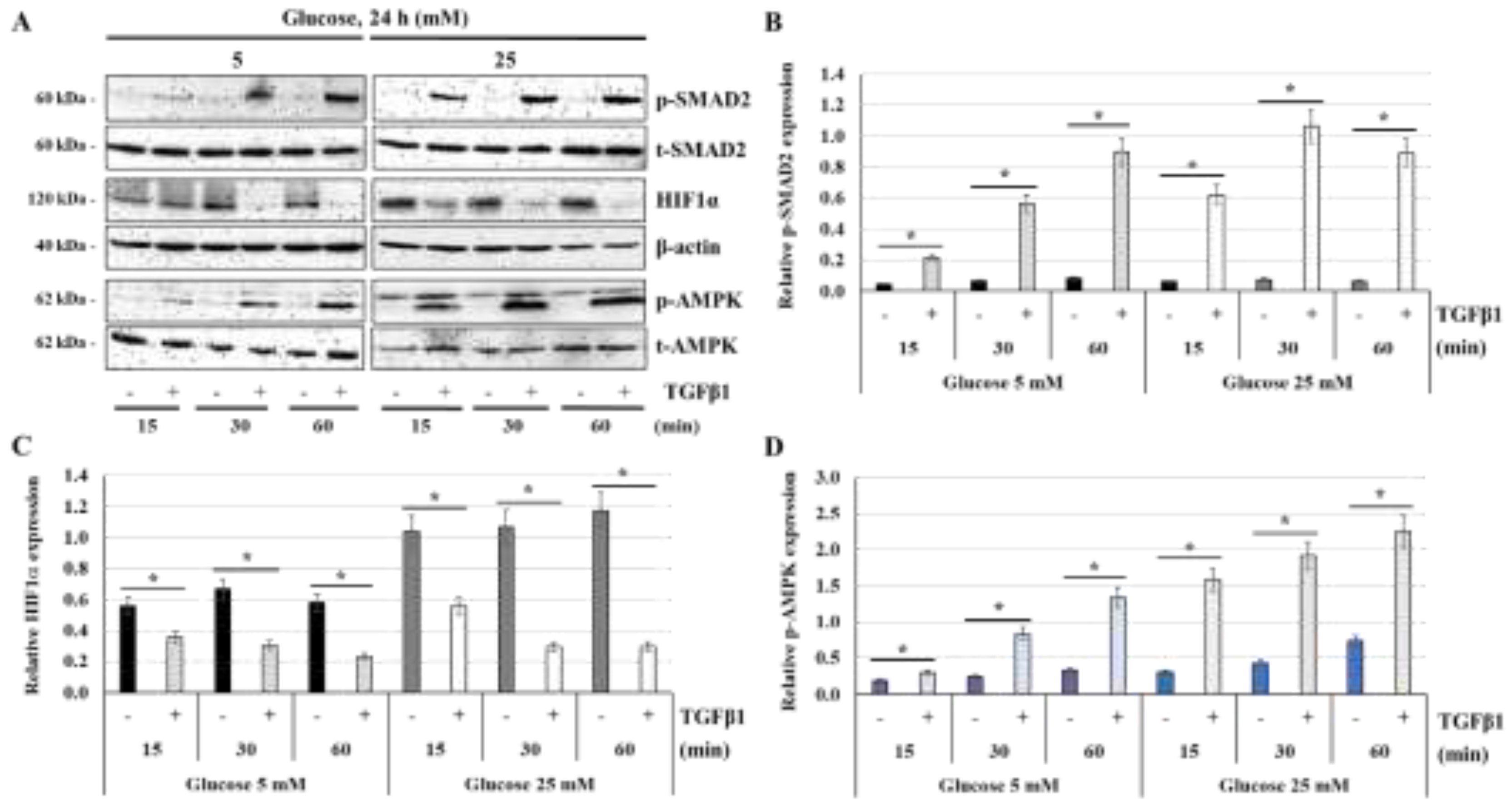

The impact of TGFβ1 on trophoblast metabolism is not extensively investigated. Here, we demonstrated that TGFβ1 treatment of trophoblast JEG-3 cells resulted in the degradation of HIF1α under normal- and high-glucose concentrations. Although prior studies have demonstrated that TGFβ1 induces HIF1α stability under hypoxic and normoxic conditions by inhibiting the prolyl hydroxylase domain protein PHD2, an oxygen sensor that typically promotes HIF1α degradation [

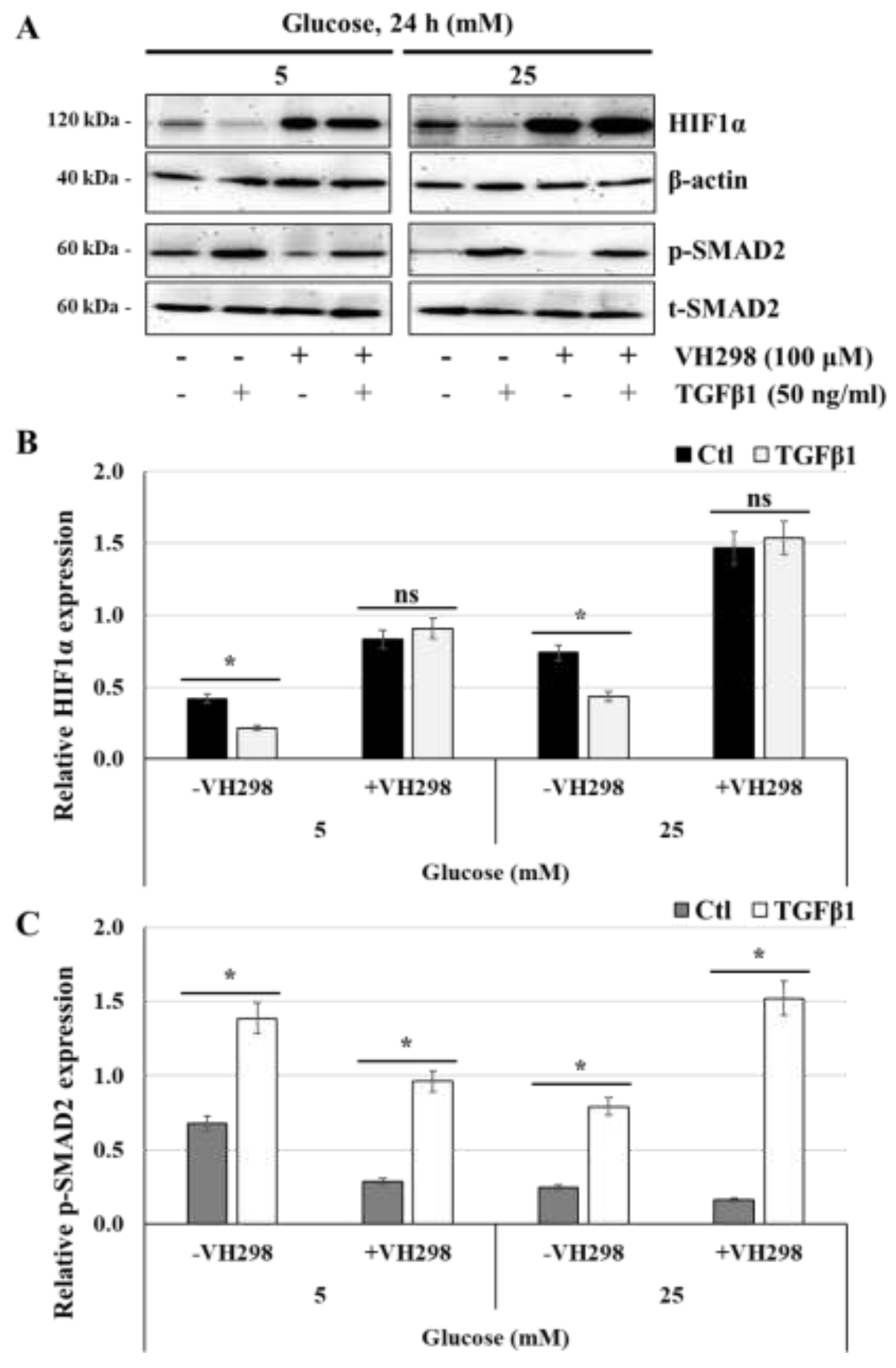

45]. Noticeable, the stability and function of HIF1α is also regulated by hyperglycemia through interference with the degradation of HIF1α triggered by PHD enzymes [

46]. The findings suggest the presence of dual effects of TGFβ1 on HIF1α stability and degradation in different physiological and pathological contexts. In this study, we demonstrated that TGFβ1-induced HIF1α degradation is blocked in the presence of VH298, a potent and specific VHL inhibitor that disrupt VHL: HIF protein–protein interaction and subsequent HIF1α proteasomal degradation, suggesting that TGFβ1 might induce HIF1α proteasomal degradation via enhanced VHL or PHD enzyme activities. Nonetheless, additional research is necessary to understand the precise mechanism by which TGFβ1 causes HIF1α degradation in JEG-3 cells.

The impact of TGFβ1 on HIF1α in JEG-3 cells was accompanied by the activation of AMPK, regardless of glucose concentration. This outcome aligns with research suggesting that TGFβ1 can indirectly activate AMPK through various signaling pathways [

47]. Particularly, IGF-I and IGFBP-2 have been shown to stimulate AMPK activation and assisting in modulating AMPK activity that plays a vital role in maintaining energy balance and metabolic regulation [

47].

Conversely, our findings demonstrated that glucose concentration affected the effect of TGFβ1 on PPARγ. Specifically, we found that TGFβ1 did not affect PPARγ expression under normal glucose levels. These results indicate a potential interaction between PPARγ and AMPK in relation to the effect of TGFβ1 on ATP production. AMPK activation enhances the expression of genes related to fatty acid oxidation (FAO) through interaction with PPARγ, thereby improving mitochondrial function and ATP production. Independent research indicates that combined activation of AMPK and PPARγ synergistically upregulates FAO genes, boosting ATP levels in macrophages [

48,

49]. The AMPK-PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) pathway is crucial for mitochondrial biogenesis and function, as it enhances PPARγ activity, thereby increasing the expression of mitochondrial genes and promoting ATP production. This pathway is vital for maintaining energy homeostasis in macrophages under metabolic stress [

48,

49].

Our results indicate that TGFβ1 restores PPARγ expression under high glucose concentrations, suggesting that PPARγ is involved in enhancing ATP production in JEG-3 cells under high glucose stress. Even though earlier investigations have revealed that the activation of PPARγ by agonists in β-cells can promote mitochondrial energy metabolism and improve ATP production. This regulation helps manage glucose-stimulated insulin secretion under lipotoxic conditions [

50,

51]. Investigations have revealed that activation of PPARγ in prostate cancer cells increased mitochondrial biogenesis and ATP levels by upregulating AKT3, which enhanced the nuclear localization of PGC1α [

50,

51].

5. Conclusions

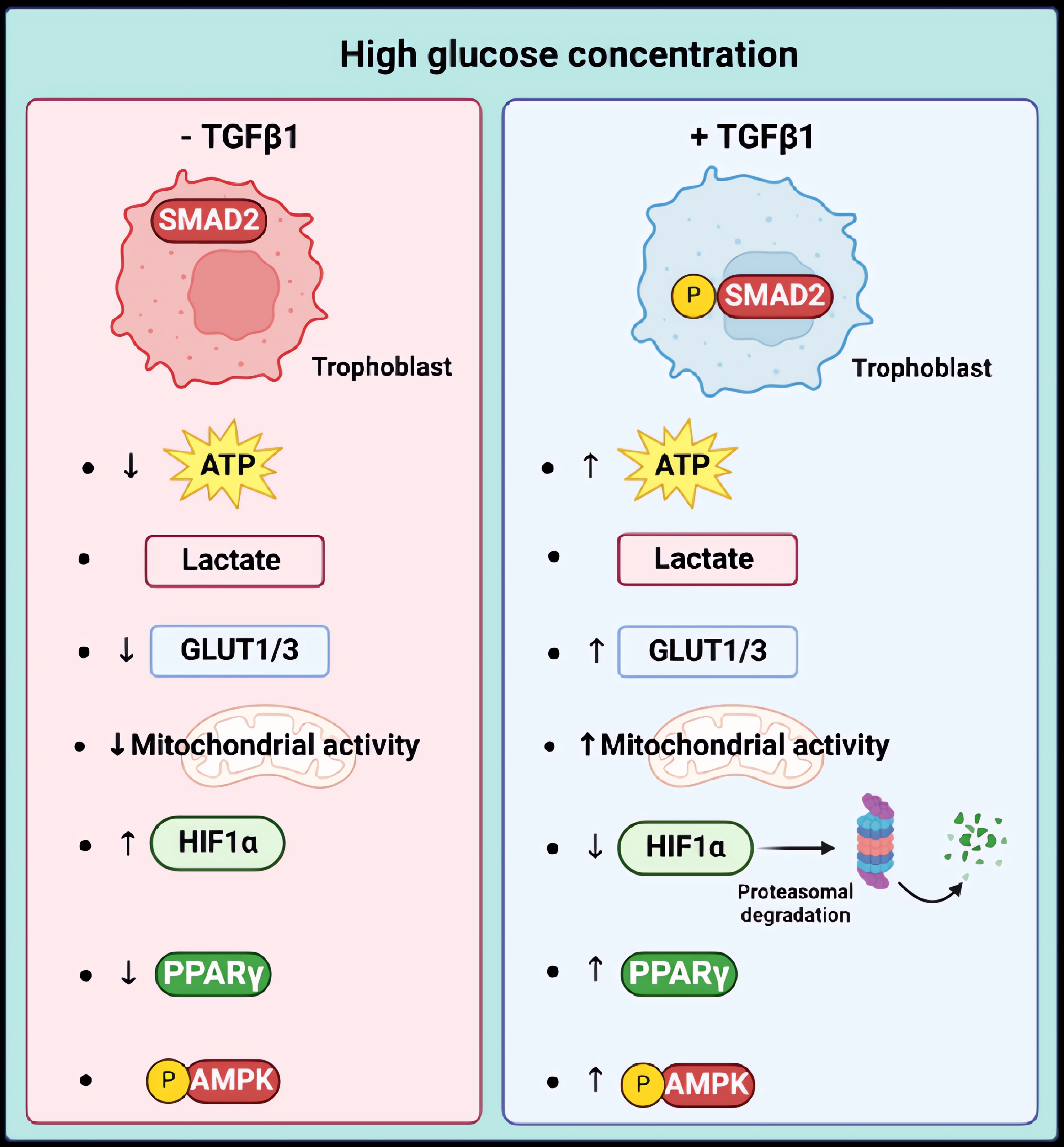

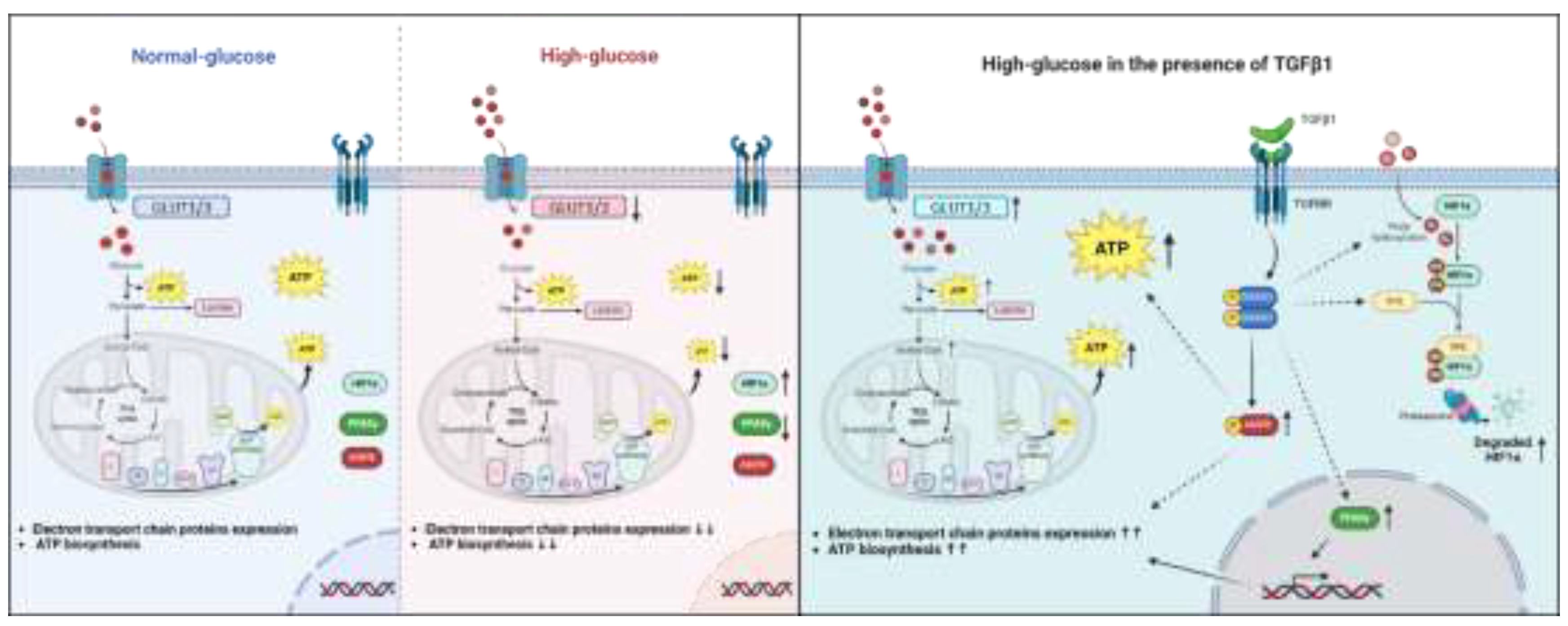

Elevated blood glucose levels at the fetal-maternal interface are associated with problems in placental trophoblasts and an increased risk of pregnancy-related complications. Our study suggests that TGFβ1 may play a protective role against the negative effects of high-glucose concentrations on trophoblast JEG-3 cells. Our results showed that high glucose treatments disrupted energy and mitochondrial metabolism, which was indicated by a decrease in ATP production without affecting lactate production. At the molecular level, this was demonstrated by an increase in HIF1α expression and nuclear localization, a decrease in PPARγ expression and nuclear localization, and a decrease in the expression of GLUT1 and GLUT3, and respiratory chain proteins. Our study is the first to demonstrate that TGFβ1 can have a protective effect by restoring ATP production under high-glucose stress conditions by inducing HIF1α degradation, AMPK activation, and restoring PPARγ and respiratory chain protein expression (

Figure 10).

These results are significant because they add to the list of TGFβ1's effects during pregnancy. TGFβ1 is essential for successful pregnancy by regulating immune tolerance, trophoblast invasion, and placental development. Dysregulation of TGFβ1 signaling, as observed in preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction, can lead to severe complications, emphasizing its crucial role in maintaining pregnancy health. However, further research is needed to better understand the role of TGFβ1 in regulating glucose metabolism and energy balance in the placenta and in trophoblast cells and its potential use in protection against gestational complications.

The trophoblast JEG-3 cell is a choriocarcinoma cell line, which presents a limitation in the study design that impact the ability to interpret and generalize from our research results. In fact, due to ethical restrictions and limited availability of human tissues, trophoblast cell lines are generally used to investigate many aspects of trophoblast biology and metabolism. According to a study by Lee et al. (2016), JEG-3 cells share some expression characteristics with primary human trophoblast cells, particularly the expression of C19MC miRNAs [

52]. Additionally, KRT7, GATA3, and TFAP2C are emphasized as reliable markers for identifying primary trophoblasts, supporting the characterization of JEG-3 cells. Additionally, a study by Weiss et al. (2001) showed that compared to other immortalized cell lines, JEG-3 cells showed higher expression of glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3, suggesting a greater capacity for glucose uptake [

53]. Future

in vitro investigations using human trophoblast stem cells or placental explants will further provide us insight into fundamental biological effects and the regulating role of TGFβ1 in different metabolic conditions. Moreover, we also plan to confirm whether these TGFβ1 mechanisms operate in an

in vivo model.

Figure 1.

High-glucose concentration decreases total ATP production without affecting lactate production: (A,B) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (10, 15, and 25 mM). (A) Quantitation of ATP production (n = 3) was assessed using ATP luminescence detection assay kit. (B) Quantitation of lactate production (n = 3) was assessed using Lactate-Glo™ assay kit. Data are expressed as nM of ATP and lactate. * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference compared to 5 mM-glucose group, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 1.

High-glucose concentration decreases total ATP production without affecting lactate production: (A,B) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (10, 15, and 25 mM). (A) Quantitation of ATP production (n = 3) was assessed using ATP luminescence detection assay kit. (B) Quantitation of lactate production (n = 3) was assessed using Lactate-Glo™ assay kit. Data are expressed as nM of ATP and lactate. * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference compared to 5 mM-glucose group, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 2.

High-glucose concentration decreases the expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins: (A,B) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM). (A) Representative images of OXPHOS complexes protein subunits detection and β-actin, as assessed by western blot. (B) Graphical analysis showing the expression of different mitochondrial complexes proteins subunits relative to β-actin at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). * p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 2.

High-glucose concentration decreases the expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins: (A,B) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM). (A) Representative images of OXPHOS complexes protein subunits detection and β-actin, as assessed by western blot. (B) Graphical analysis showing the expression of different mitochondrial complexes proteins subunits relative to β-actin at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). * p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 3.

High-glucose concentration differentially regulates the nuclear expression of PPARγ and HIF1α: (A,B) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentration (25 mM). (A) Representative images of PPARγ, HIF1α, β-tubulin, and Lamin B1 in the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments of JEG-3 cells, as assessed by western blot. (B) Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of HIF1α and PPARγ in the cytoplasm and the nucleus at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). * p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 3.

High-glucose concentration differentially regulates the nuclear expression of PPARγ and HIF1α: (A,B) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentration (25 mM). (A) Representative images of PPARγ, HIF1α, β-tubulin, and Lamin B1 in the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments of JEG-3 cells, as assessed by western blot. (B) Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of HIF1α and PPARγ in the cytoplasm and the nucleus at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). * p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 4.

Glucose concentration regulates TGFβ1-induced SMAD2 phosphorylation: (A,B) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (10, 15, and 25 mM), and then stimulated for 30 min with culture media alone (control) or with 50 ng/ml TGFβ1. (A) Representative images showing the expression of phosphorylated SMAD2 (p-SMAD2) and total SMAD2 (t-SMAD2) as evaluated by western blot. (B) Graphical analysis showing the expression levels of p-SMAD2 relative to t-SMAD2 for each glucose concentration (n = 3). * p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference compared to control.

Figure 4.

Glucose concentration regulates TGFβ1-induced SMAD2 phosphorylation: (A,B) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (10, 15, and 25 mM), and then stimulated for 30 min with culture media alone (control) or with 50 ng/ml TGFβ1. (A) Representative images showing the expression of phosphorylated SMAD2 (p-SMAD2) and total SMAD2 (t-SMAD2) as evaluated by western blot. (B) Graphical analysis showing the expression levels of p-SMAD2 relative to t-SMAD2 for each glucose concentration (n = 3). * p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference compared to control.

Figure 5.

TGFβ1 differentially regulates glucose transporters expression, lactate and ATP production: (A-E) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM) in the absence or the presence of TGFβ1 at 50 ng/ml. (A) Representative images of GLUT1, GLUT3 and b-actin protein detection, as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of GLUT1 (B) and GLUT3 (C) at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose. (D) Quantitation of lactate production was assessed using Lactate-Glo™ assay kit. (E) Quantitation of ATP production was assessed using ATP luminescence detection assay kit. Data are expressed as nM of ATP and lactate (n = 3). Each bar represents the mean ± SD from at least two independent experiments. * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the cell groups, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 5.

TGFβ1 differentially regulates glucose transporters expression, lactate and ATP production: (A-E) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM) in the absence or the presence of TGFβ1 at 50 ng/ml. (A) Representative images of GLUT1, GLUT3 and b-actin protein detection, as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of GLUT1 (B) and GLUT3 (C) at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose. (D) Quantitation of lactate production was assessed using Lactate-Glo™ assay kit. (E) Quantitation of ATP production was assessed using ATP luminescence detection assay kit. Data are expressed as nM of ATP and lactate (n = 3). Each bar represents the mean ± SD from at least two independent experiments. * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the cell groups, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 6.

TGFβ1 enhances the expression of the mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins at normal-glucose and high-glucose concentrations: (A,B,C,D) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM) in the absence or the presence of TGFβ1 at 50 ng/ml. (A) Representative images of OXPHOS complexes protein subunits detection, SMAD2 (p-SMAD2 and t-SMAD2), and β-actin, as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the expression of different mitochondrial complexes proteins subunits relative to β-actin at 5 mM (B) and 25 mM (C) glucose, and the summary of fold induction from all OXPHOS proteins subunits (D). (B,C) * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference compared to control (n = 3). (D) ** p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference between 5 mM and 25 mM glucose concentration, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 6.

TGFβ1 enhances the expression of the mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins at normal-glucose and high-glucose concentrations: (A,B,C,D) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM) in the absence or the presence of TGFβ1 at 50 ng/ml. (A) Representative images of OXPHOS complexes protein subunits detection, SMAD2 (p-SMAD2 and t-SMAD2), and β-actin, as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the expression of different mitochondrial complexes proteins subunits relative to β-actin at 5 mM (B) and 25 mM (C) glucose, and the summary of fold induction from all OXPHOS proteins subunits (D). (B,C) * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference compared to control (n = 3). (D) ** p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference between 5 mM and 25 mM glucose concentration, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 7.

TGFβ1 increases the expression of PPARγ at high-glucose concentration: (A,B,C) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM) in the absence or the presence of TGFβ1 at 50 ng/ml. (A) Representative images of PPARγ, β-actin, and SMAD2 (p-SMAD2 and t-SMAD2), as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of PPARγ (B) and p-SMAD2 (C) at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between control and TGFβ1 treatments, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 7.

TGFβ1 increases the expression of PPARγ at high-glucose concentration: (A,B,C) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM) in the absence or the presence of TGFβ1 at 50 ng/ml. (A) Representative images of PPARγ, β-actin, and SMAD2 (p-SMAD2 and t-SMAD2), as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of PPARγ (B) and p-SMAD2 (C) at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between control and TGFβ1 treatments, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 8.

TGFβ1 decreases HIF1α expression but enhances AMPK activation at normal-glucose and high-glucose concentrations: (A,B,C,D) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM), and then activated in the absence or the presence of TGFβ1 at 50 ng/ml for 15, 30, or 60 min. (A) Representative images of SMAD2 (p-SMAD2 and t-SMAD2), HIF1α, b-actin, and AMPK (p-AMPK and t-AMPK), as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of p-SMAD2 (B), HIF1α (C), and p-AMPK (D), at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 8.

TGFβ1 decreases HIF1α expression but enhances AMPK activation at normal-glucose and high-glucose concentrations: (A,B,C,D) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM), and then activated in the absence or the presence of TGFβ1 at 50 ng/ml for 15, 30, or 60 min. (A) Representative images of SMAD2 (p-SMAD2 and t-SMAD2), HIF1α, b-actin, and AMPK (p-AMPK and t-AMPK), as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of p-SMAD2 (B), HIF1α (C), and p-AMPK (D), at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 9.

TGFβ1-induced HIF1α degradation is blocked in the presence of VH298, a specific inhibitor of ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of HIF1α: (A,B,C) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM), and then activated for 60 min with TGFβ1 in the absence or the presence of VH298. (A) Representative images of HIF1α, β-actin, and SMAD2 (p-SMAD2 and t-SMAD2), as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of HIF1α (B) and p-SMAD2 (C) at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the cell groups, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 9.

TGFβ1-induced HIF1α degradation is blocked in the presence of VH298, a specific inhibitor of ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of HIF1α: (A,B,C) JEG-3 cells were cultured for 24 h in media containing normal-glucose (5 mM) or high-glucose concentrations (25 mM), and then activated for 60 min with TGFβ1 in the absence or the presence of VH298. (A) Representative images of HIF1α, β-actin, and SMAD2 (p-SMAD2 and t-SMAD2), as assessed by western blot. Graphical analysis showing the relative expression of HIF1α (B) and p-SMAD2 (C) at 5 mM and 25 mM glucose (n = 3). * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the cell groups, and ns = nonsignificant difference.

Figure 10.

Graphical representation suggesting a protective effect of TGFβ1/SMAD signaling pathways in trophoblast cells under high-glucose stress conditions by restoring ATP production via induction of HIF1α degradation, AMPK activation, and restoring PPARγ, GLUT1/3, and electron transport chain protein expression.

Figure 10.

Graphical representation suggesting a protective effect of TGFβ1/SMAD signaling pathways in trophoblast cells under high-glucose stress conditions by restoring ATP production via induction of HIF1α degradation, AMPK activation, and restoring PPARγ, GLUT1/3, and electron transport chain protein expression.