1. Introduction

In materials science and engineering (MSE), having a well-thought-out, reliable, and consistent method for producing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) [

1] process and material data is crucial for accelerating material discovery. Adhering to FAIR principles improves the reproducibility and reduces the ambiguity of data, which is extremely important for a domain like MSE characterized by data scarcity and diversity. Adopting the W3C Semantic Web standards to transform materials data to knowledge graphs is one promising way to create FAIR data in MSE, facilitating direct linkage of data generated at different stages in materials process chains. In addition, with the advent of powerful large language models [

2], knowledge graphs could serve as a countermeasure to address its performance limitations identified [

3] in the MSE domain. For instance, strategies like grounding the output of LLMs on the facts in knowledge graphs could enhance their reliability [

4]. The present work is motivated by the need for a clear and systematic digitalization workflow that generates high-quality, semantically structured linked material data. The work presents a user-friendly approach for digitalizing material data, ensuring that the proposed solution can be implemented by not just IT experts, but also materials engineers and scientists from diverse backgrounds.

Different data sources come into consideration when prescribing a digitalization strategy in MSE, such as existing structured and unstructured data collections, as well as actively generated data in research and production. Looking at existing structured data sources serves to point out what is missing in the current digitalization strategies. Several publicly available datasets, such as the ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) [

5], the OQMD (Open Quantum Materials Database) [

6], the Materials Project [

7], the MDF (Materials Data Facility) [

8] or the NOMAD (Novel Materials Discovery) [

9], have been popular databases in the MSE domain in the past decades. However, most of these databases often contain incomplete and ambiguous data points, and they cannot be connected to each other. This is also the case for company-specific internal databases which are not interconnected unstructured data from literature or documents available in MSE. Semantic web technologies allow addressing these challenges, ensuring that material data is structured and connected to related data, not ambiguous, and interoperable.

In the stack of W3C-endorsed technologies, ontologies are fundamental in adding meaning to data, ensuring it is unambiguous and interoperable [

10,

11,

12]. They serve as ’machine-understandable’ representations of a domain, where knowledge is expressed as axioms that can be used to infer new insights from existing data, thereby improving data querying and analysis.

Numerous ontology development efforts have been undertaken to model different sub-domains as well as the general MSE domain. Most of these ontologies either do not adhere to a top-level ontology or utilize BFO [

13] or EMMO [

14] as the top-level. In the general MSE domain, ontologies like PMD-core [

15], MSEO [

16], and EMMO are currently popular. Additionally, ontologies have been developed for various subdomains and applications in MSE, such as mechanical testing [

17,

18,

19] and manufacturing [

20,

21]. Norouzi et al. [

22] highlight that despite numerous ontology design efforts in MSE, there is still a need to adopt ontology design patterns based on explicit competency question formulations in the MSE domain.

This work introduces a new mid-level ontology that models generic MSE concepts, along with a domain-level ontology focused on the permanent mold casting process for AlSi10Mg, and the manufacturing and material characterization processes. Importantly, the digitalization strategy is designed to be ontology-agnostic, allowing it to work alongside other ontology development efforts in MSE.

Despite numerous initiatives to develop ontologies in MSE, a lack of focus on practical methods for data annotation and user-friendly workflows that can assist materials scientists in utilizing Semantic Web technologies to produce FAIR data remains. While some related work has been discussed, including a well-documented example of a web-based data infrastructure for generating FAIR tribological data [

23], it is clear that a formalized knowledge extraction process is needed to improve communication between ontology developers and materials science experts. Bridging the gap between these disciplines is essential for increasing the acceptance of ontologies in materials science.

Moreover, demonstrating the feasibility and applicability of digitization methods through real-world examples is vital. These efforts not only validate and enhance existing ontologies and knowledge graph structures but also showcase the knowledge gained from digitizing materials science data using Semantic Web technology. A compelling application of generating semantically structured materials data lies in providing context-rich and historically informed data to AI models, which can significantly accelerate material design and optimization processes.

The main objective of this work is to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of digital mapping of chemistry-process-structure-property relationships along industrially relevant process chains through a clear and systematic digitization workflow that generates high-quality, semantically structured, linked materials data. A key focus is on building digital process chains, which are essential for managing the product life cycle of any object and ensuring effective quality control. A methodology for creating digital process chains is particularly critical in engineering, where existing literature has not adequately addressed this need. Consequently, significant efforts have been made to implement the necessary digitalization steps in a user-friendly manner, ultimately contributing to the advancement of digitalization in MSE data.

This work presents a methodology to uniformly structure and represent material data along real-world process chains.

Section 2 introduces the underlying experimental dataset for AlSi10Mg, along with the BWMD Ontology and a flexible methodology for digitalizing MSE domain knowledge, supported by representative examples. An interview template is also included to facilitate interaction with domain experts. The resulting data structures and datasets are summarized in

Section 3, presented through real-life use cases for knowledge extraction. A first step toward AI-assisted prediction of material properties is taken based on the generated knowledge base, demonstrating its machine readability. Finally, the results are discussed in

Section 4 and concluded in

Section 5 .

2. Materials and Methods

First, the experimental dataset for the cast material AlSi10Mg, developed within the framework of the MaterialDigital project [

24], is introduced, as well as the ontology providing the necessary vocabulary to describe the context of the mentioned material dataset. Second, the methodology for digitalizing process-generated data using Semantic Web technology, known as the ’Graph Designer Workflow’, is presented. This methodology will be illustrated with examples from the aforementioned experimental dataset, highlighting the various steps involved in the proposed approach.

2.1. Description of the Experimental Database for the cast AlSi10Mg

Within the framework of the BWMD project [

24] and out of the ’Use Case Metals’, a comprehensive database was generated for the cast aluminium material AlSi10Mg. To this end, different manufacturing routes were followed, aiming to improve the mechanical properties of the cast AlSi10Mg. Various process parameters were applied in the permanent mold casting process, as well as variations of the amounts of Si and Mg in the melt. After the permanent mold casting process, the batches of material produced were heat treated following two steps: first solution annealing, then artificial aging. Small variations were also introduced during these two steps, by modifying the duration and the maximum temperature applied during the solution annealing and aging heat treatment steps. The resulting different manufacturing routes followed, led to different material batches with different mechanical properties, such as tensile strength, ductility, and hardness.

To investigate and mechanically characterize the different material batches, the heat-treated cast parts, were finished as tensile test specimens and metallographic specimens. Those were used to perform tensile tests and Brinell hardness measurements. Additionally, component-like parts were cast, and their defect or porosity distribution was investigated via computer tomography.

The generated experimental database requires a data architecture capable of seamlessly linking the data produced by the different processes of the manufacturing process chain to each of the manufactured or investigated objects. Therefore, a Semantic Web solution was sought to provide interoperable data and design a general process structure pattern to enable the construction and retrieval of the digital process chain of an object. The aim is to digitalize the different production routes with all the relevant contextual data, from a different viewpoint, creating the possibility of storing process information about an object in terms of its chronological history.

2.2. The BWMD Ontology

The first step in generating semantically structured data is establishing a common vocabulary to be formalized in the form of an ontology and a data model, both of which are to be determined by the use case.

An ontology consists of a collection of classes (hierarchically organized following the class-subclass relation), properties and constraints, whereby an ontology aims to describe domain knowledge at a reasonable granularity for better reuse and understanding of the digitalized domain data. Hereafter, it is important to clarify that the classes of an ontology encapsulate a range of categories of objects or concepts that share similar attributes and behaviors. Meanwhile, the instances of a class represent a particular individual inside a given class.

Within the framework of the project MaterialDigital [

24], a domain ontology managing class hierarchy, object properties, and data properties, was designed and implemented. This domain ontology was the product of the united efforts and extensive communication between different MSE domain experts. The developed domain module was directly merged with the BFO 2.0 top-level ontology [

25] and received the name of ’BWMD Ontology’ [

26,

27]. The BWMD Ontology contains two layers, a mid-level ontology layer to model material-intensive process chains and a domain layer to model all process details related to the permanent mold casting process for AlSi10Mg, manufacturing and characterization processes (mechanical and analytical). The process chains modeled by the mid-level ontology concepts (classes and properties) include the processed objects and corresponding process-related data (raw data and analyzed properties), the involved process parameters, the involved machines, as well as the necessary research equipment, infrastructure and software. The BWMD Ontology, also enables a simple description of the material structure, which can be specified for the chemical composition, the material volume, and the material surface. The BWMD Ontology does not include axioms beyond subclassing and domains and range restrictions for object and data properties.

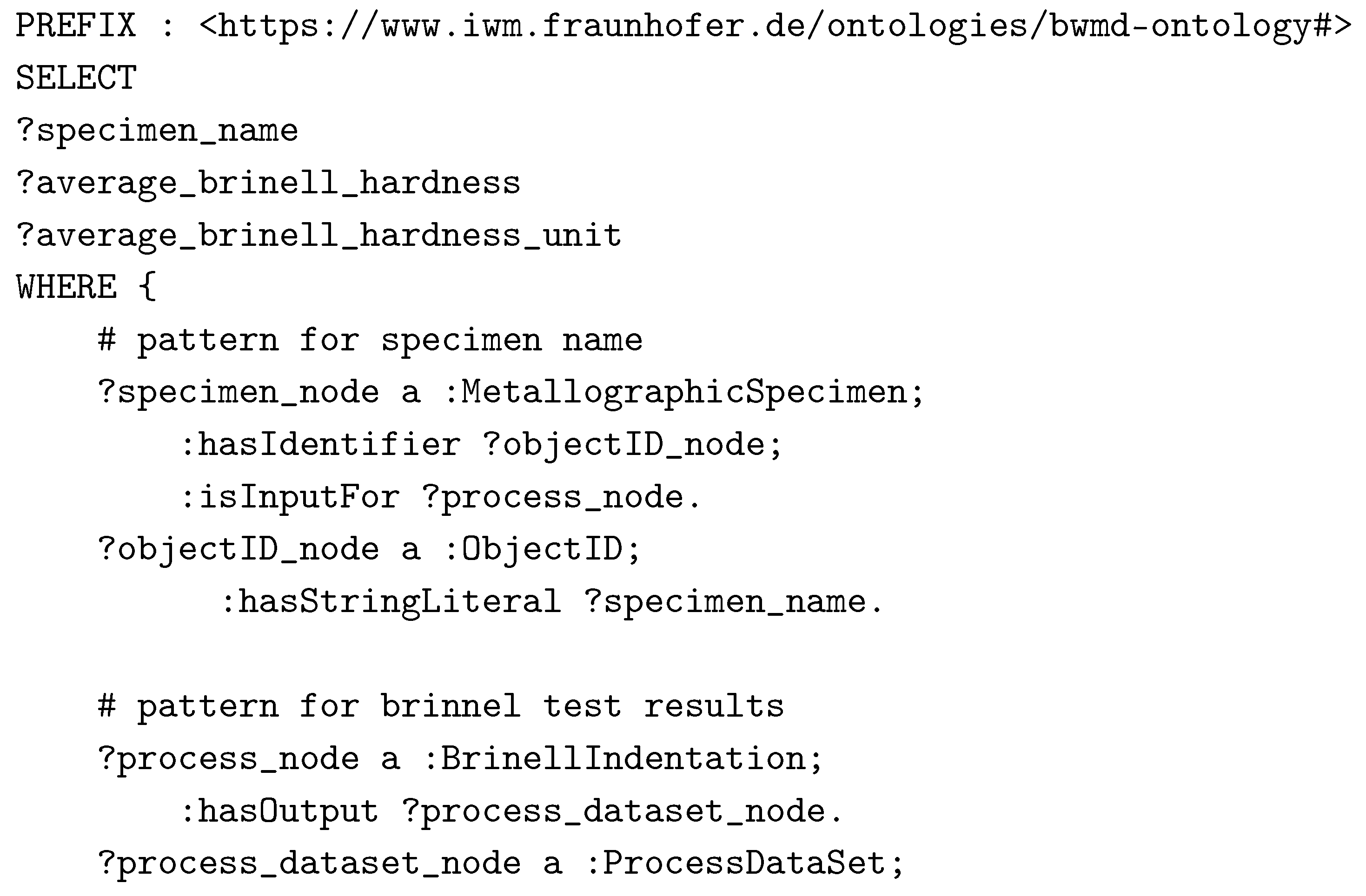

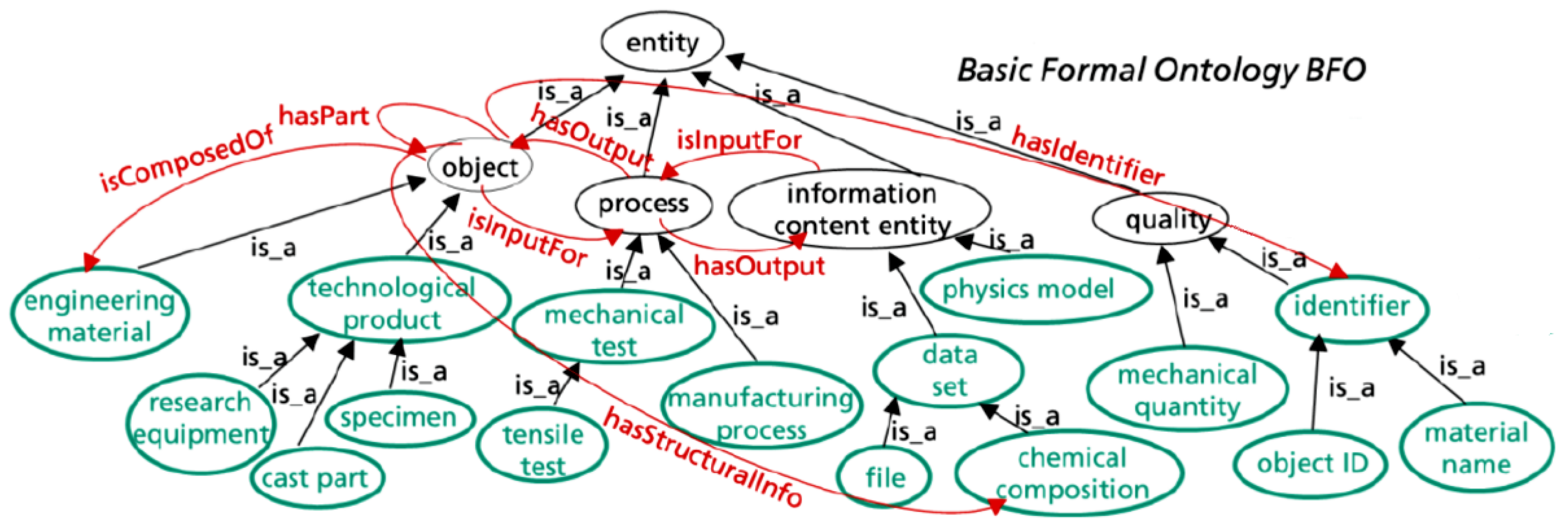

Figure 1 schematically shows how the BWMD ontology classes are linked to BFO classes. It exemplifies how the owl:class

engineering material from the BWMD Ontology is modeled as a subclass of (

) the BFO owl:class

object. The BFO classes are shown in black and the classes specific to the BWMD Ontology are displayed in green. Details about how instances of these classes are related are expressed by the object properties, depicted in red. This straightforward representation illustrates how an

object can interact with a process as an ’input’ or ’output’ instance. A

chemical composition could be associated with a particular

object through the object property

hasStructuralInfo, and each

object is associated with a specific object identifier through the object property

hasIdentifier, which points to an instance of the class

identifier, that could be more specifically represented by one of its subclasses, e.g.:

object ID (to identify an object) or

material name (to identify a material). On the other hand, the concept of

dataset (e.g., a

chemical composition) is modeled as a subclass of the IAO (Information Artifact Ontology [

28]) owl:class

information content entity, where an instance of

information content entity can be directly connected to a process, both as input and as output instance.

2.3. The Graph Designer Workflow

The Graph Designer Workflow is a generic digitalization workflow used to model the metadata of arbitrary processes as an interoperable manageable knowledge graph. It includes an ontology, a process data model or process graph template, a set of tools (the Graph Designer Tool), and a data pipeline. It is generic enough to work for different processes, ontologies, and data models, with the outcome being structured data presented as ontology-based knowledge graph(s).

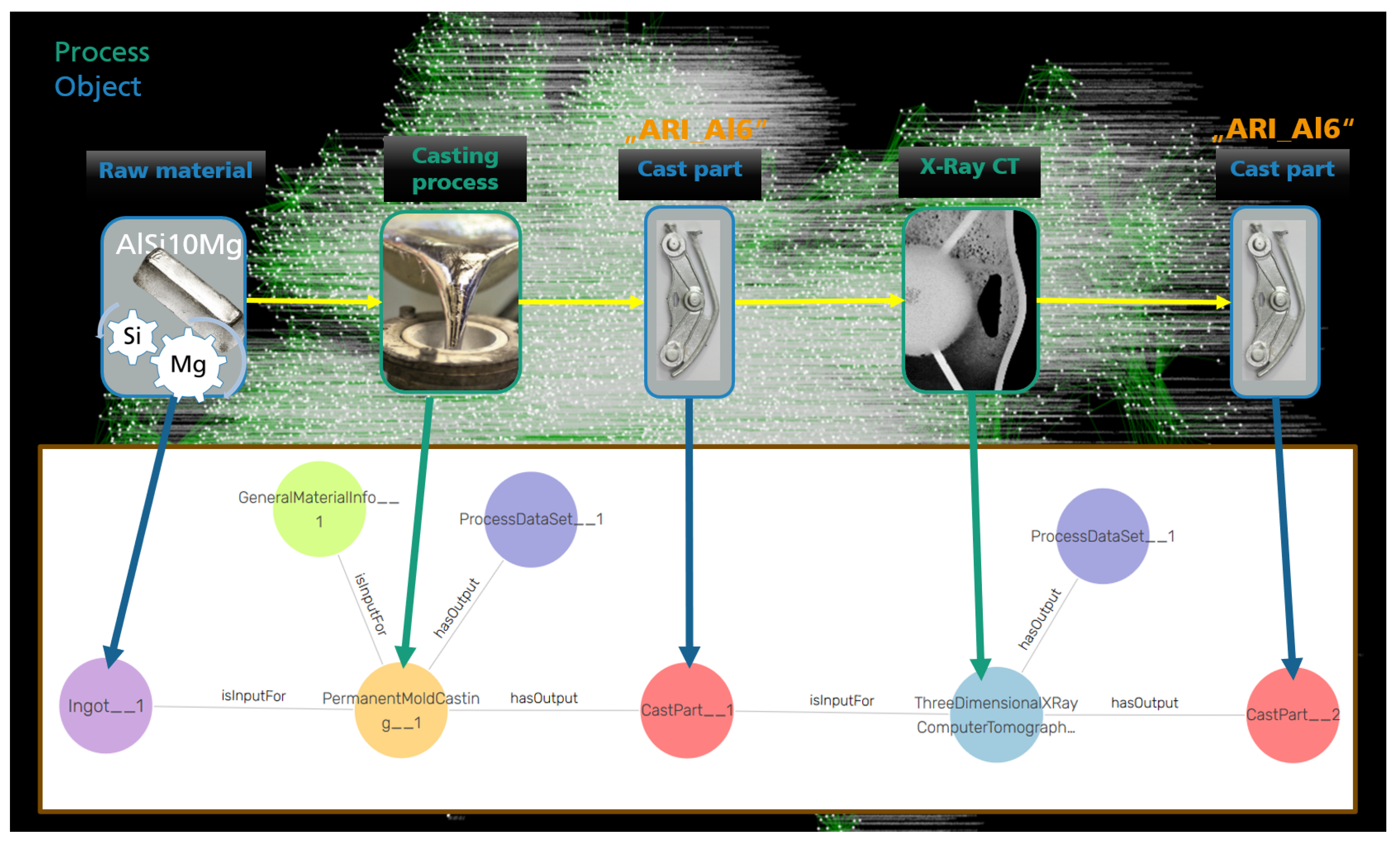

The Graph Designer Workflow is also coupled with a data modeling philosophy, which relies on the idea of creating a data model (or graph) for each impartible process part of the process chain of a labeled product, attaching to each single process its corresponding relevant metadata. In this context, ’process chain’ refers to the sequence of processes. An example of such an impartible process including the input and output objects is represented in

Figure 2.

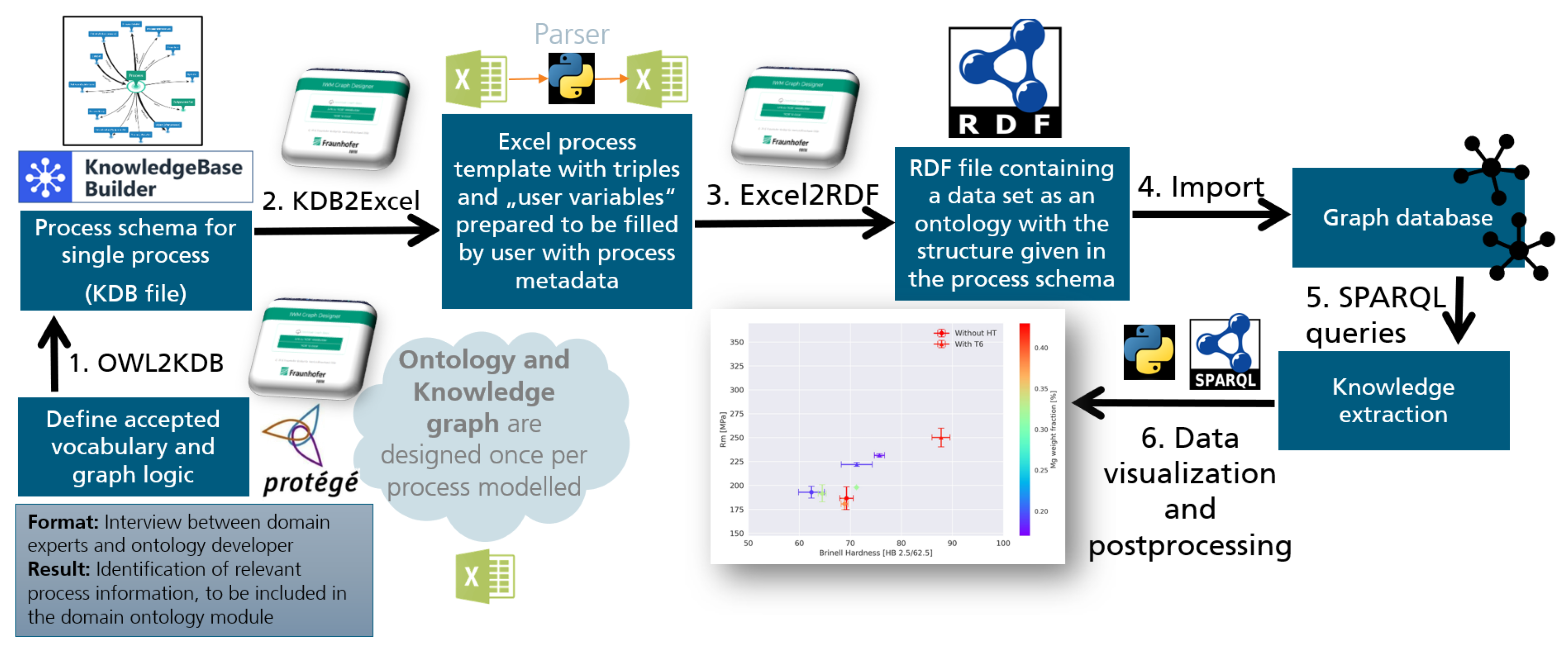

The introduced digital workflow for data structuring is illustrated in

Figure 3 and comprehends the following steps:

Domain knowledge extraction: the first step when semantically modeling a new process, is to establish the necessary vocabulary to describe the knowledge and data to be digitalized. This step is vital and will determine the quality and richness of the digitalized process data. The successful completion of the digitalization process is contingent on efficient communication between domain experts and ontology developers. To overcome the existing knowledge gap between these two involved parties an interview template was created. The interview template enables structured interviews and serves as an information exchange protocol. The output of this step results in the process-specific shared vocabulary, being integrated into the domain ontology selected for the concrete use case. The formalization of the new extracted domain-specific vocabulary into an existing ontology (or into a new domain ontology module) is then performed with the help of the software Protégé [

30] or a customized Python script;

Creation of impartible process graph templates: at this point, a single process step is generically represented as a knowledge graph (hereinafter denoted as ’Process Graph’). For this purpose, the software Inforapid KnowledgeBase Builder [

31] is used, which offers a graphical user interface for generating graphs. The Process Graph template generation of an impartible process consists of modifying a generic Process Graph template, based on the information gathered from the interview template filled in the previous step and consequent established domain-specific vocabulary (domain ontology). This step is accomplished with the help of the functionality

OWL2KDB of the ’Graph Designer Tool’ [

29], which allows the user to import concepts from an existing ontology into the graphing tool. Creating a process-specific Process Graph Template is an iterative process. It might take a few hours to days to semantically represent all relevant parts of the modeled process, depending on its level of description detail and complexity. The generated graph for describing the relevant metadata of the digitalized process is then converted into an Excel template. This substep is performed with the help of another functionality of the Graph Designer Tool, referred to as

KDB2Excel;

Acquisition of process datasets: the previously generated Excel template is duplicated and filled in by the domain experts of the respective process step. In principle, the filling can also be script-controlled. In addition to the captured metadata, the raw data is collected and linked in the filled or annotated Excel template;

RDF graph data generation: once the Excel templates have been filled with all the available process metadata, those are converted into RDF data via the Graph Designer Tool functionality Excel2RDF. The generated graphs follow the structure defined in the specific Process Graph template and are compatible with the semantic structure of the generic Process Graph template, used as a common pattern;

Linking of process datasets: this step comes in addition when aiming to build digital process chains out of the different semantic data generated by reproducing the Graph Designer Workflow for each digitalized process along the supply chain. In the last step of data structuring, the process steps are linked according to the sequence of the physical process chain.

At the end of the data structuring procedure, the entire knowledge graph of the process chain is available in a graph database (e.g. [

32]) and can be imported and exported using the standardized RDF format for knowledge graphs. Each of the mentioned steps will be explained in detail in the upcoming sections along with real-life examples extracted from the database introduced in

Section 2.1.

2.3.1. Systematic Extraction of Domain Expert Knowledge

The interview template supports the knowledge extraction process, which guides the information exchange between the ontology developer and the domain expert. The work of the ontology developer - from outlining the process to developing the ontology – is thus facilitated and errors can be minimized. A draft version of the interview template focused on the semantic description of an experimental process can be downloaded in [

33]. The interview template is based on the different phases of an experimental process - the setup, the execution, and the outcome. This structure is intended to assist the domain expert in completing the template.

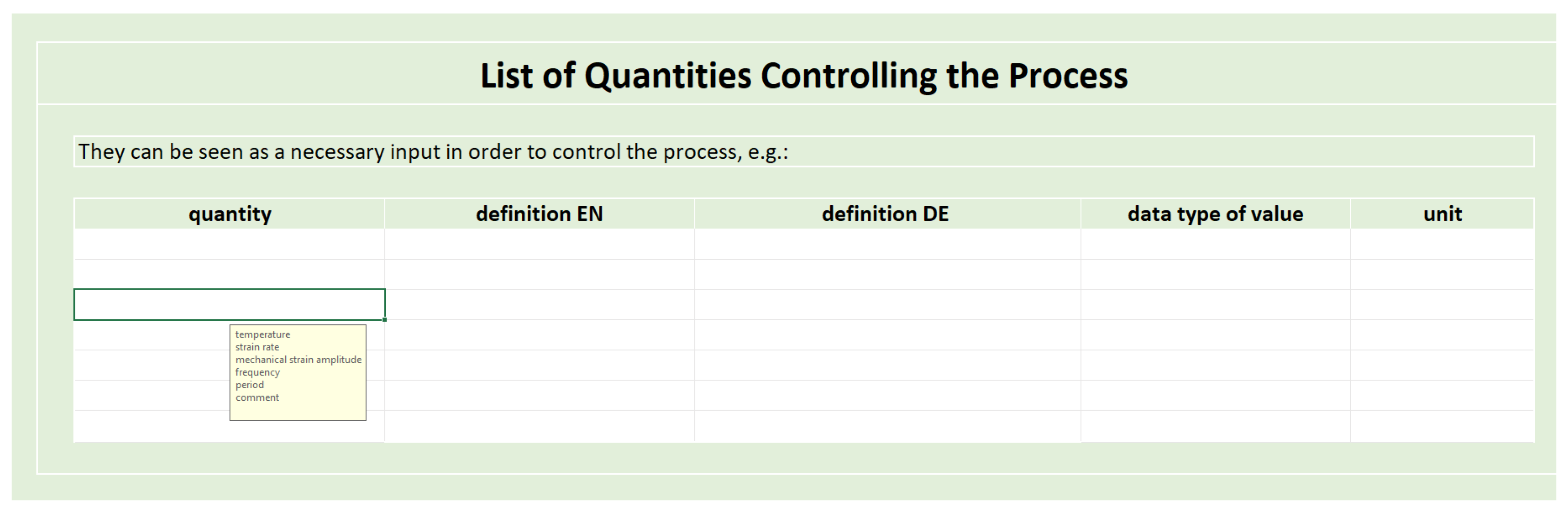

After a short introduction text for the domain expert in the first tab of the template, the process metadata, software and equipment tabs follow as part of the setup phase. Here, among other things, the contact information of the process owner, but also general information about the process, used software, and used equipment are requested. This is followed by process input and process control parameters as part of the execution phase. These tabs give the ontology developer a lot of important information about the test object (e.g. if preparation steps were performed) as well as information about all parameters controlling the process.

Figure 4 shows the table of process control parameters. The yellow hint box is intended to support the domain expert in selecting the control parameters. For each parameter, a definition in English (and for this case also in German), the data type (e.g. string, integer), and the unit (e.g. °C, %) are expected additionally. This list provides the ontology developer with all information about the process control parameters for direct integration into the domain ontology.

In the last phase, the results are handled. The process output and time stamp tabs are provided in the Excel sheet for this purpose. The process output describes, among other things, any changes undergone by the test object and all data generated during the process. The time stamp determines the start and end time of the process. Two additional tabs - input and output data description - allow the domain expert to insert screenshots of the respective data and add a short comment.

Formally, the template is structured so that yes/no questions are included in the first level. If there is a need for further questions for the corresponding answer, these only then unfold. This ensures a clear presentation.

2.3.2. Creating a Process Graph: The Semantic Data Model

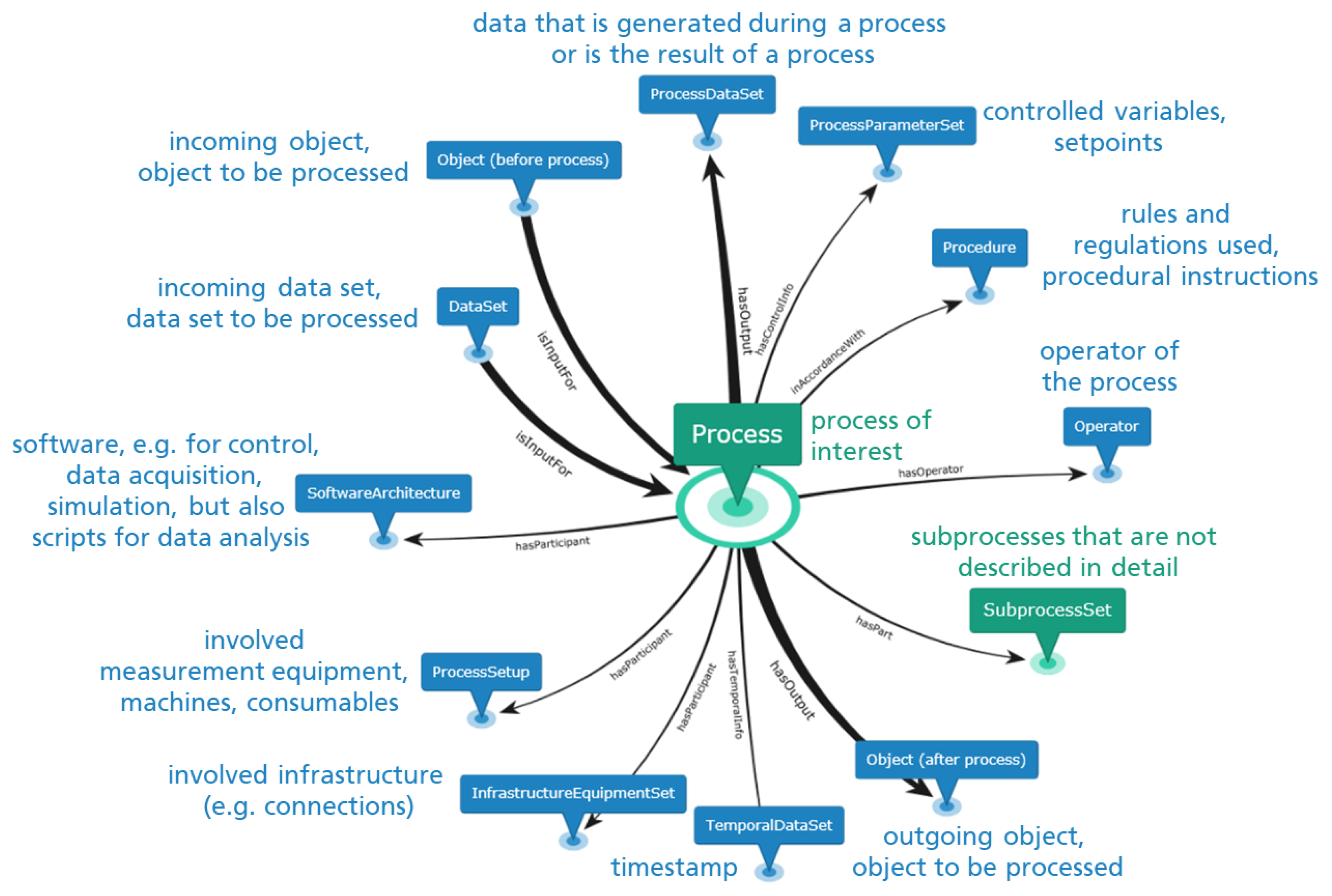

The design of the semantic data model is done based on the generic Process Graph template, illustrated in

Figure 5. Its core structure consists of 12 node types and 8 object properties directly connected to the Process. If irrelevant to the design of the Process, nodes, and associated object properties can be deleted. During the Process template design, the category of the Process node in

Figure 5 needs to be refined (e.g. by

PermanentMoldCasting). It is important to note, that the referred template is built on, based on BWMD ontology vocabulary. The nodes represent instances of BWMD classes connected to other instances through object properties from the BWMD ontology. In the following, the meaning of the core nodes and object properties are explained:

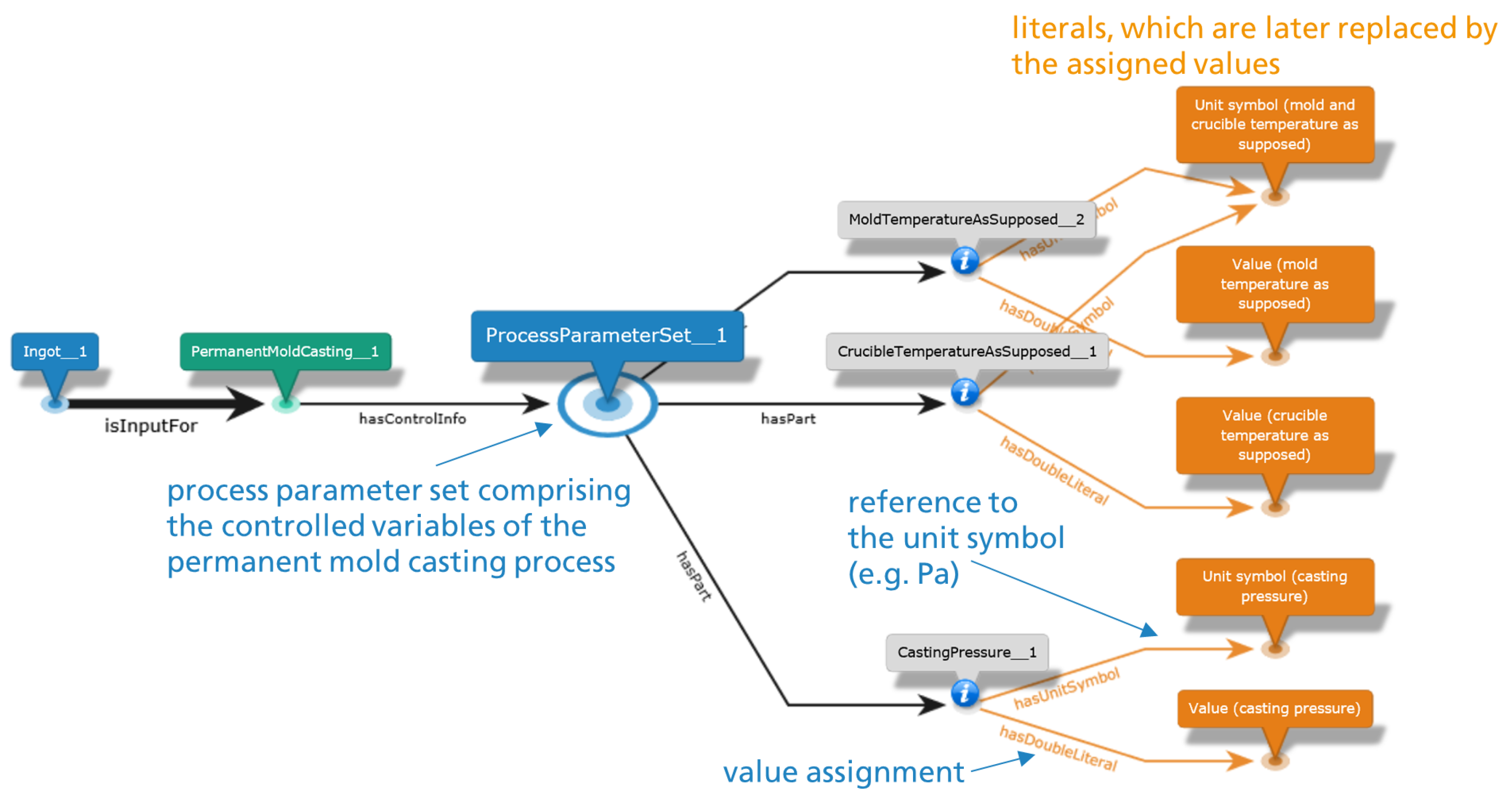

isInputFor and hasOutput are relations to describe the chronological order along the process chain and are attached to nodes, which are either the input for a process (Object and DataSet) or the output thereof (Object and ProcessDataSet). During process design, the categories of the ingoing and outgoing objects can be further specified/refined. The same holds for the ingoing DataSet. The node ProcessDataSet collects all data, that is either generated during the course of a process (e.g. raw data) or is the result thereof (e.g. analyzed material properties);

The setpoints and controlled variables of the process are assigned to the node ProcessParameterSet;

Machines, measurement equipment and consumables used within the process are allocated to the node ProcessSetup;

The node InfrastructureEquipmentSet merges the necessary infrastructure (e.g. connections for cooling water or compressed air);

Any kind of software (e.g. for data acquisition, unit control, simulation) and scripts (e.g. for data analysis) are assigned to the node SoftwareArchitecture;

The node Procedure is used, if the process is performed following some rules and standards;

the node Operator designates the operator of the process;

The node SubprocessSet integrates all subprocesses, which are helpful to refine the logic or sequence of the process, but do not need to be described in full detail.

The generic graph template is usually extended and modified but without changing the core structure. This is part of the semantic modeling strategy and is of great importance in generating interoperable linked data for the different digitalized processes and retrieving information based on these common patterns.

After the generic Process Graph template is adjusted to semantically describe the metadata generated by the specific modeled process, it is converted into an equivalent Excel template with the functionality KDB2Excel from the Graph Designer Tool.

2.3.3. Template for Metadata Acquisition

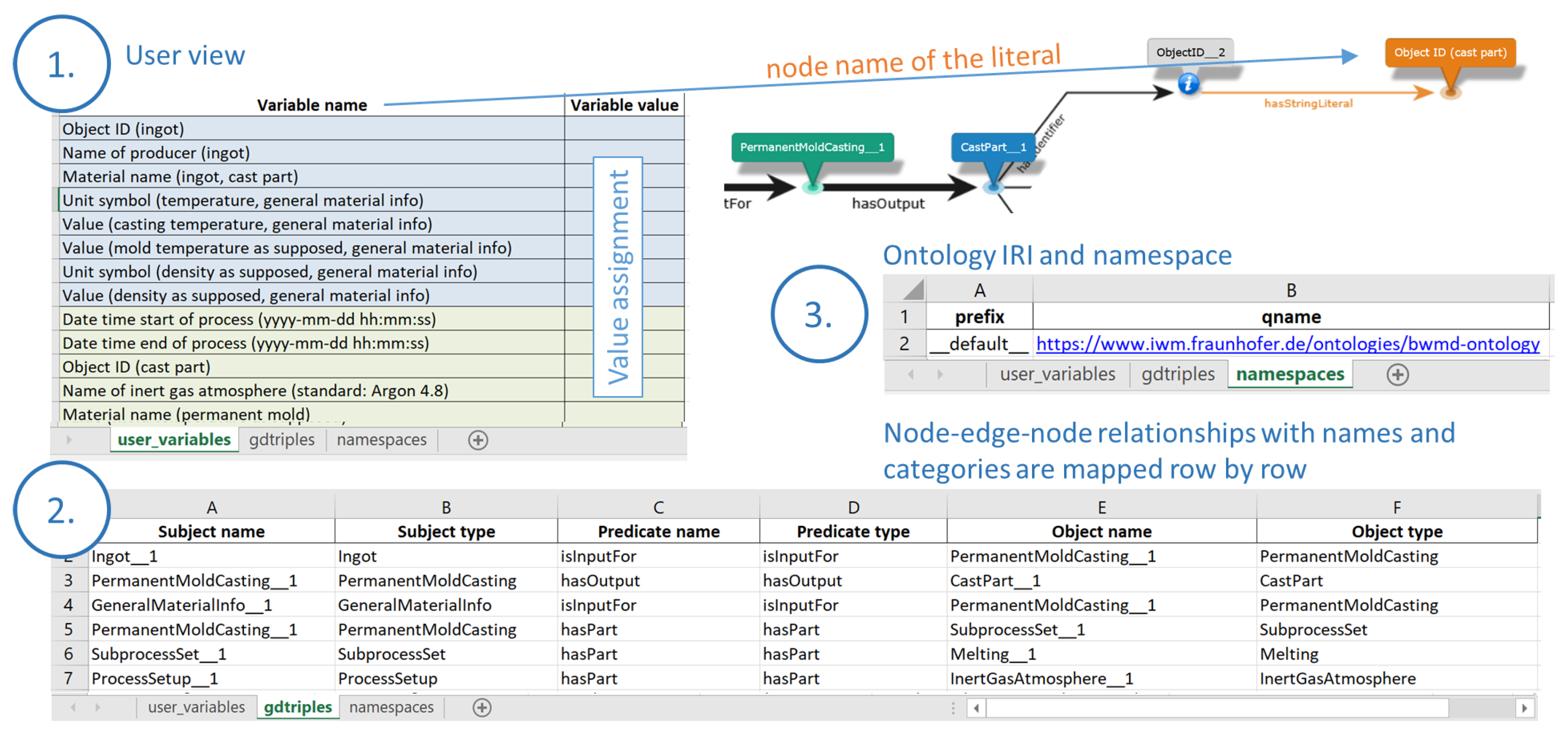

The Excel template for metadata acquisition is exemplary displayed for the

PermanentMoldCasting process in

Figure 6 and contains three sheets. The Spreadsheet

user_variables contains the user view for metadata acquisition. Here the value assignment or data annotation takes place. The names in the column

Variable name refer to the literal node names from the process graphs (more details later). At this point, it is expected that the domain experts can annotate their data by filling the column

Variable value of the Excel template with literal values.

In the gdtriples spreadsheet, the knowledge graph template structure is stored line by line using node names and categories (subject/object name/type) and edge names and categories (predicate name/type). This spreadsheet is not intended to be changed by the user.

In the last spreadsheet namespaces, the mapping of RDF namespace prefixes to namespaces is stored. It is also not intended to be changed by the user.

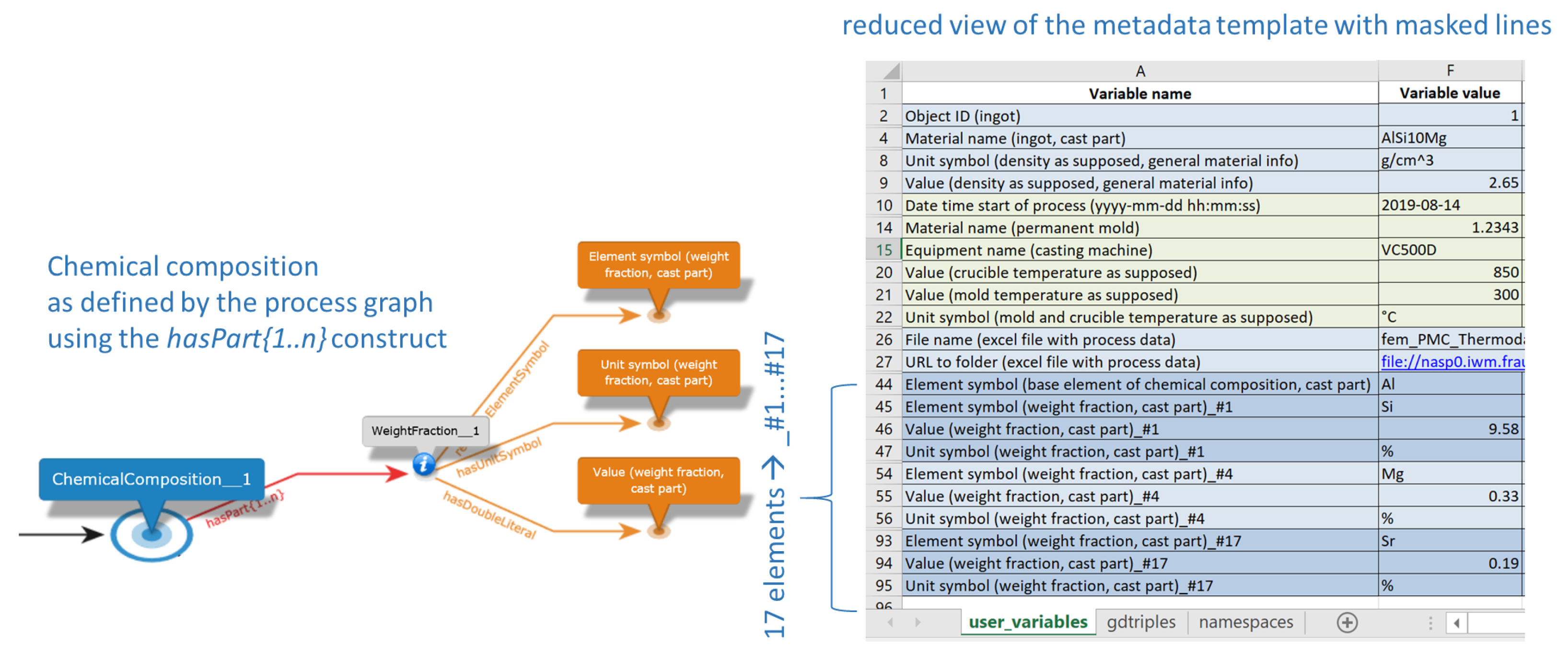

2.3.4. Handling Cardinalities in Process Graph Templates

In the generic modeling of processes as Process Graphs, one is regularly confronted with the problem that the number of e.g. outgoing objects from a separation process or the number of chemical elements with corresponding weight fractions can vary within a chemical composition. This problem is solved by adding a suffix to the edge name (e.g. hasOutput or hasPart) in the process graph. The suffix {1..n} means, that the following nodes occur at least once or n-times. Where n is a positive integer, thus allowing to model optional properties or relations. Example: Separating hasOutput{1..n} Object.

The curly brace is removed when the Process Graph template is converted to an Excel file. Literals that follow such a {1..n} construct are marked with the combination of ’# ’ and a sequence number within the Excel template in the user view. A variable-value pair marked in this way can be duplicated by the user in the Excel template section

user_variables as needed, as illustrated by

Figure 7.

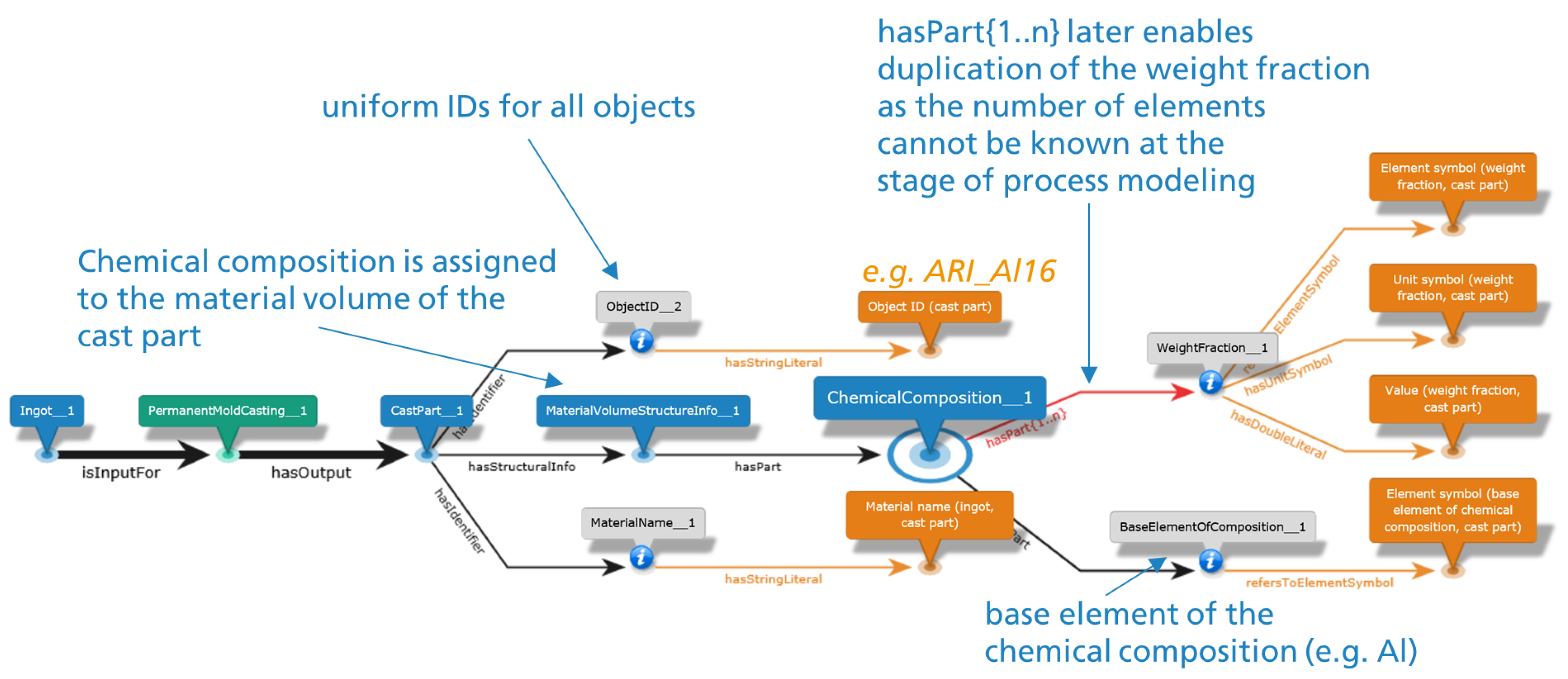

2.3.5. Conversion of Metadata Templates to RDF

The completed Excel templates are converted into RDF using the functionality Excel2RDF of The Graph Designer Tool. By assigning values in the Excel template, the Process Graph becomes a graph instance populated with process-specific literal values. All nodes, interpreted as instances of an ontology class, are assigned a unique resource identifier (URI) containing the original node name and a unique identifier. The original node names of the Inforapid KnowledgeBase Builder software are also retained in the RDF file as labels of the type rdfs:label. Similarly, the original node category is retained as rdf:type, which implies that the resource is an instance of an owl:class.

2.4. Linking of Process Datasets

Once all processes have been semantically modeled and all the generated RDF files have been uploaded into a graph database, the next step towards building digital process chains for all the digitalized objects is to link all the individual process graphs generated. The linking is done via the incoming and outgoing objects or datasets of the involved processes and is realized by SPARQL statements creating owl:same_as relations. This is achieved by locating all objects modeled as the output of one specific process using the pattern Process_x hasOutput Object_x, and stating that this object is indeed the same object modeled as inputFor the next chronological process, e.g. Process_y, within the physical process chain. However, it is represented as a different instance, e.g. Object_y. Consequently, the statements added to the graph database containing the disconnected process graphs will follow the pattern Object_x isSameAs Object_y. With the assistance of a reasoner, it can then be inferred, that Object_x was indeed inputFor Process_y.

4. Discussion

While many papers have focused on the development of material ontologies [

37,

38,

39,

40] and fewer on the design of knowledge graphs for structuring material data through knowledge graph patterns (e.g., [

41,

42]), there are no known investigations dedicated to presenting a generic approach for digitalizing material data via a semantic data model that emphasizes the creation of digital process chains. This work aims to design a digitalization strategy focused on developing semantic data models for impartible processes, as introduced in

Section 2. Despite existing material ontologies, a new ontology tailored to the digitalization strategy for creating digital process chains within the MSE domain was introduced in

Section 2.2. The BWMD ontology employs the BFO 2.0 as a top-level ontology, compatible with the ISO/IEC 19763 standard [

43], providing a solid foundation for developing interoperable domain and application ontologies.

The BWMD ontology is the product of a two-year collaborative effort among MSE experts from various German research institutes, initiated in 2018. Although this paper references its non-modularized version for simplicity, a modularized version exists and is published in [

44]. This modularized version includes a mid-level module for general concepts and a domain module for specific concepts related to mechanical testing procedures, microstructural features, and specimen preparation.

This article does not advocate for a specific ontology for modeling material data. Parallel developments of mid-level and domain-specific ontologies, such as the PMD-Core ontology [

15] from the Material Digital Platform initiative [

45], are equally suitable for modeling MSE data. The PMD-Core ontology was initially developed with a bottom-up approach to align with the EMMO [

14] and has since been adapted for interoperability with BFO [

46]. Another ontology, the MSEO [

16], developed within the Materials Open Laboratory initiative, also aligns with BFO principles. Additionally, a mechanical testing domain module [

18] was created within the Urwerk project [

47], partially covering the MSE domain. Creating mappings between these MSE ontologies can enhance interoperability and mutual benefits.

It is important to note that in addition to the Graph Designer Tool, other digitalization tools are available for material data. Tools like OpenRefine [

48], TARQL [

49], and Ontopanel [

50] offer different approaches for digitalizing and structuring material data. However, the advantages of the Graph Designer Workflow, as presented in this work, are significant. The Graph Designer Tool [

51] provides a user-friendly interface for uploading ontology vocabularies into a generic Process Graph template, managing multiple namespaces, and converting the Graph Template into a standard Excel Table for data annotation. This minimizes errors from misinterpreting domain vocabulary and allows domain experts to populate the Process Graph template with real data.

The proposed MSE data digitalization strategy successfully achieves the goal of bridging the existing knowledge gap between domain and ontology experts. While not technological, this challenge poses significant obstacles in digitalizing material science knowledge. Effective information exchange between domain and ontology experts is crucial for designing appropriate semantic models. Understanding the meaning of classes when incorporating new vocabulary into the domain ontology is essential for selecting suitable upper classes from mid-level or top-level ontologies. The quality of this exchange will determine the value of the generated semantically structured data, with a richer vocabulary providing deeper context and knowledge. The interview template introduced in

Section 2.3.1 facilitates efficient information exchange, guiding the classification of new concepts according to the semantic schema of the generic Process Graph template in

Section 2.3.2. This significantly aids ontology experts in adjusting templates and creating compliant data models. The challenges in knowledge extraction are often overlooked in literature, despite being well-known in the ontology development community. Additionally, using NLP (Natural Language Processing) to extract information from domain-specific literature is a powerful tool for semi-automated domain ontology creation.

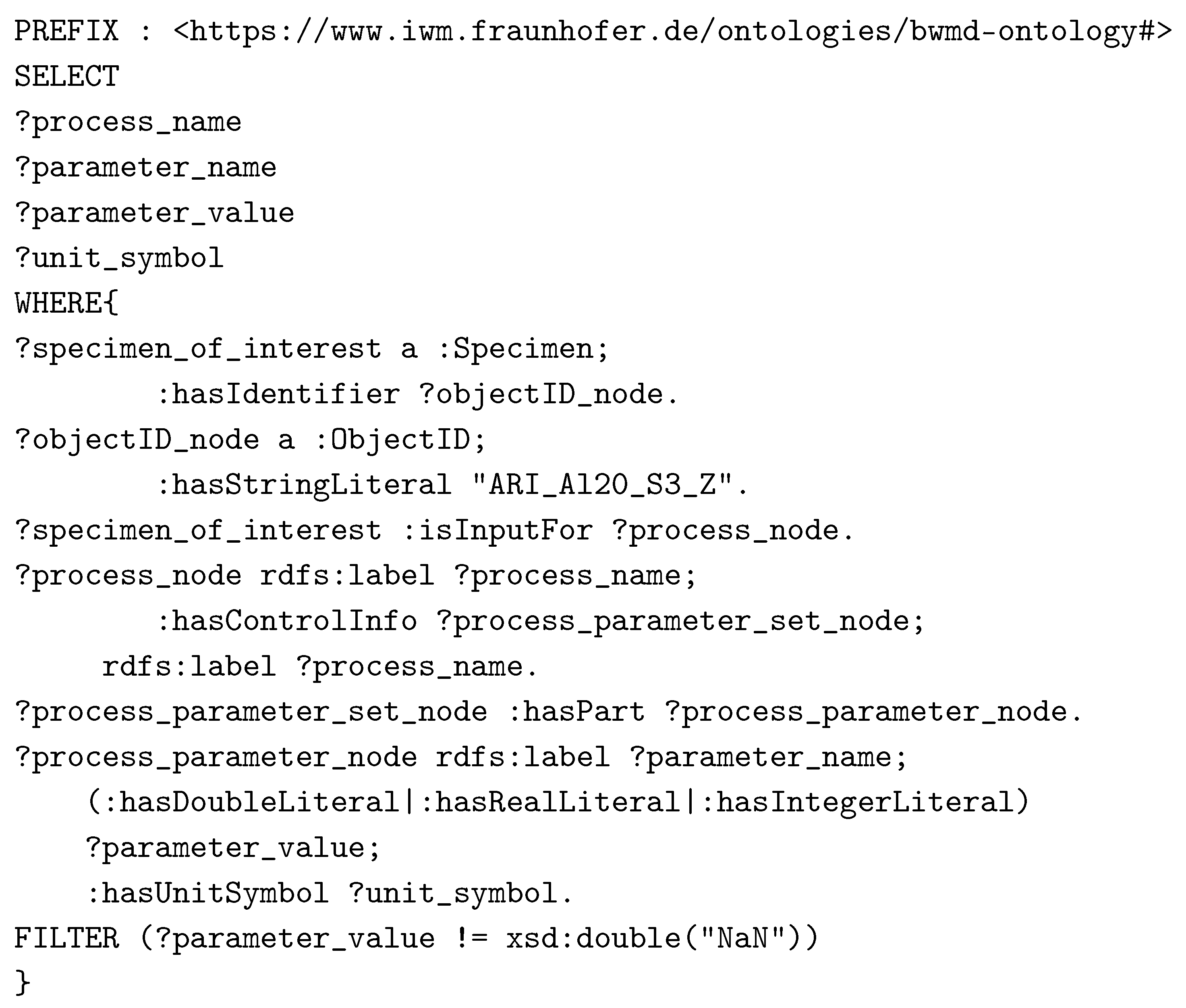

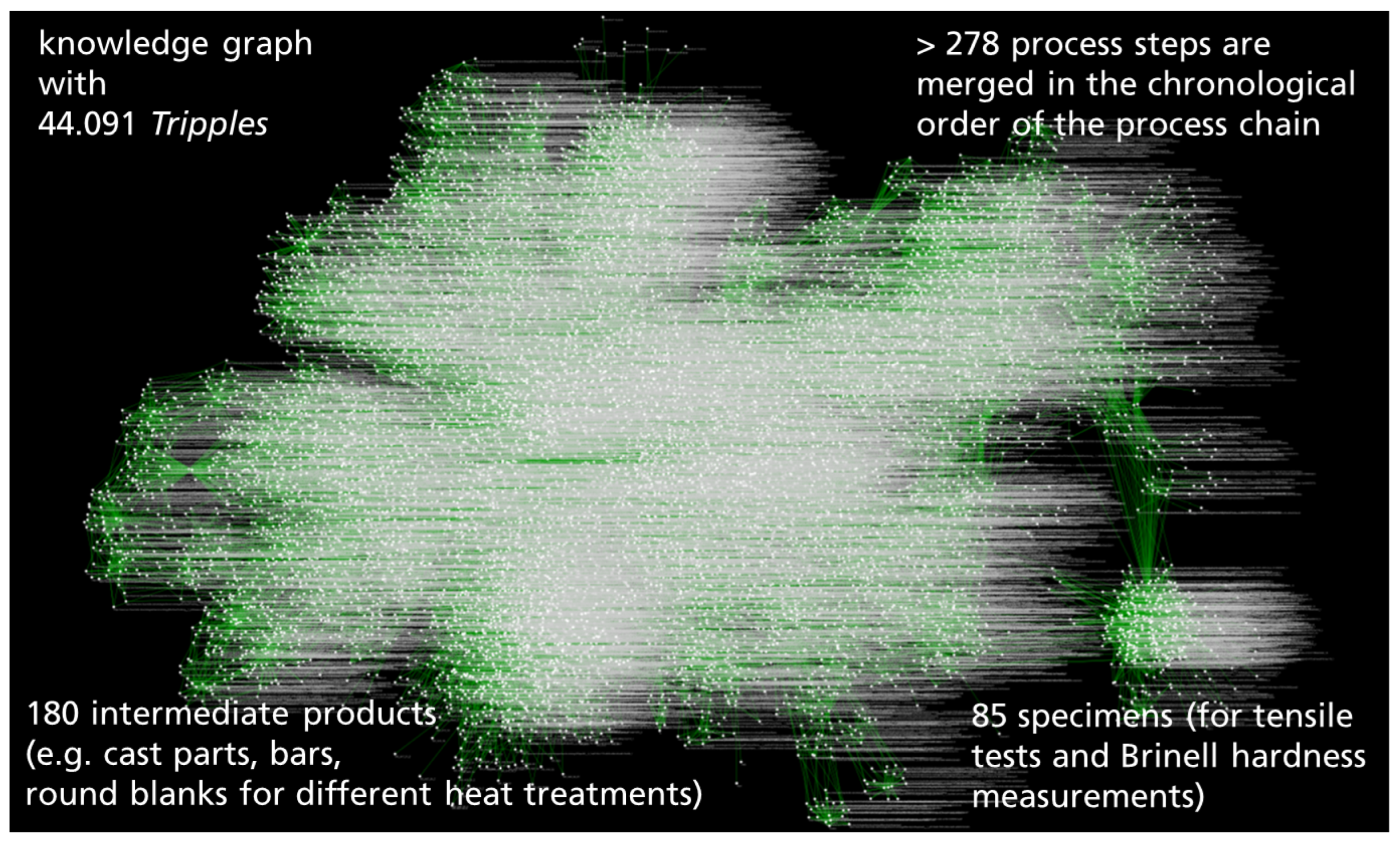

The generic aspect of the Graph Designer Workflow implies its possible application with other ontologies or semantic data models. However, the presented work demonstrates its applicability based on the BWMD ontology and the generic process graph template as a semantic data model to efficiently build digital process chains for the cast AlSi10Mg use case. The BWMD Dataset RDF graph, depicted in

Figure 10, has been introduced in

Section 3. This RDF graph is publicly available in the Fordatis database [

26]. The primary objective of this work is to present a generic digitalization method for semantically modeling various processes using different ontologies as base vocabularies and instantiating schemas or generic Process Graph templates. The proposed methodology is demonstrated across ten different processes (see

Table 1), showcasing the generality of the solution and the semantic depth of the BWMD ontology. As the disparity of modeled process data increases, more concepts are required to encapsulate the knowledge, leading to an enriched ontology vocabulary. In addition to the RDF graph, two Jupyter Notebooks are also accessible with the created knowledge base for the cast AlSi10Mg, including further SPARQL queries and data visualization features. This aims to add a dimension of user experience to the presented study, as this article intends to be informative and didactic [

26].

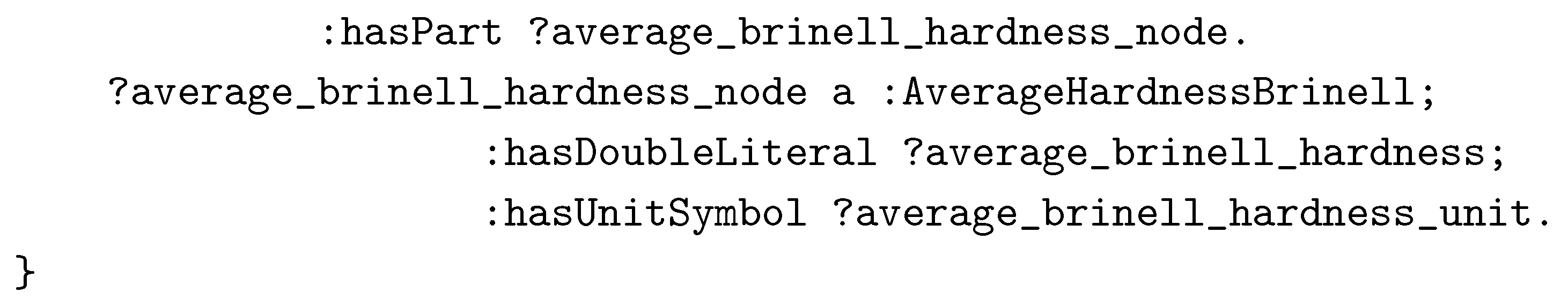

The advantages of the generic Process Graph template become apparent through the introduced SPARQL query examples in

Section 3.2. By following the core pattern of the generic process data model, generic query algorithms can be developed to efficiently and easily extract information stored in the RDF graph connecting all the different digitalized processes. The structure enables retrieval of specific material properties generated via one specific test (see

Section 3.2.1) and allows the extraction of other types of information, such as the controlled parameters applied to conduct one specific test (see

Section 3.2.2). Unlike traditional SQL databases, graph databases allow for extracting both tabular and graph data based on patterns, thanks to the

CONSTRUCT SPARQL query structure. This is illustrated in

Section 3.2.3, utilizing the SPARQL query example to retrieve the digital process chain of one specific object. The retrieved object is a piece of the complete RDF Graph and can be visualized as displayed in

Figure 13. This example shows the utility of the proposed methodology in creating a data infrastructure that enables a product traceability feature along its digitalized manufacturing process chain. Both the generic Process Graph template and the ’process chain’ query algorithm could be extended to include further process-related information details such as the

footprint or the cost associated with the conducted manufacturing step, which could later be used in conjunction with other object history information to find production routes for decreased environmental impact or for reducing production costs of a particular product.

Access to product history information enables the discovery of new production patterns, leading to optimized material properties, as illustrated in

Section 3.3. Feeding AI models with context-rich data enhances the material design process, helping to find optimal production paths and allowing for quick solutions to describe phenomena not considered in physical models. If an AI-trained model is fed with a high-quality database (as would be the case of a context-rich graph database), reliable predictions can be made. In the MSE field, this could imply significant cost reduction by creating reduced or optimized material testing programs. Another advantage would be developing robust hybrid models, which would better reproduce the dispersion of apparently similarly generated material experimental data, i.e., generated from similar testing conditions. In such cases, the material scatter can be explained by small differences detected in the control parameters along the digitalized process chain of each tested specimen, e.g., in one or several heat treatment steps, as showcased for the material AlSi10Mg regarding the impact of aging duration on the resulting tensile strength of the material. While this information is common knowledge for the material production expert, it is not necessarily shared by the material engineer who performs simulations with this material, and the information might remain hidden in the form of experimental scatter. Another hidden effect discussed in

Section 3.3 is the impact of the variation of the Mg amount in the melt on the tensile strength of the investigated material.

The presented Graph Designer Workflow and the BWMD ontology provide a robust framework for digitalizing material data and creating digital process chains. Furthermore, the digitalized context-rich semantic MSE data offer the perfect basis for training AI models and generating new reliable knowledge. The generic nature and the potential for further development make it a valuable tool for advancing material science and engineering digitalization efforts. While the Graph Designer Workflow offers numerous advantages, there are limitations inherent to working with graph databases, such as the complexity of semantic data models and SPARQL queries. However, advancements in text foundation models offer potential improvements in designing systems that interact with graph databases using natural language. Scalability issues of large graph databases also need to be addressed and approaches like Qlevel [

52] provide scalable interfaces. Future work will focus on addressing these challenges, improving user interfaces, and exploring the application of the methodology in other domains.

5. Conclusions

This work aims to accelerate materials discovery by digitalizing data from material process chains in a connected manner, exposing the composition-process-structure-property chain in MSE. Knowledge graphs link data from various processes within material process chains. Using a generic template for creating semantic models simplifies information retrieval, allowing for tracking the complete history of specific labeled objects. Additionally, the use of ontologies ensures unambiguous and interoperable data enriched with domain knowledge.

This work presents a robust methodology, the Graph Designer Workflow, for storing process-specific data and domain knowledge into linked knowledge graphs. A mid-level ontology is developed, and a generic process template is presented, along with instructions for adopting the methodology to specific process chains. The resulting machine-understandable data, stored in a graph database, adheres to the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable). The entire pipeline is presented in a didactic manner, making it easy for materials-domain experts to adopt the workflows for their digitalization problems.

The methodology is demonstrated through a use case involving the permanent mold casting of AlSi10Mg, including varied chemical composition, non-destructive characterization, specimen extraction, heat treatment, and mechanical testing. The resulting connected knowledge graph, or knowledge base, is used to retrieve and analyze data to investigate the influence of heat treatment and magnesium content on strength properties characterized by tensile tests.

From a scientific and technical point of view, the following increments were made concerning the digital mapping of material-intensive process chains:

The BWMD ontology was introduced, which is based on the Basic Formal Ontology and provides the necessary mid-level and domain-specific vocabulary for the use case of AlSi10Mg. The mid-level and domain-level parts of the ontology are also available as separate modules. The mid-level ontology module is designed to be general to the MSE domain. Comparisons and connections were made to parallel mid-level ontology design efforts in the MSE domain, highlighting the need to create mappings between these ontologies.

A generic Process Graph template for mapping material data along process chains was presented, respecting the taxonomy and semantic rules of the mid-level BWMD ontology. The Process Graph template enables a digital representation of impartible processes comprising material process chains. While digitalization efforts like PMD [

15] and UrWerk [

47] have described modeling of specific processes and process chains in MSE, the presented work provides a generic template that can be adapted for modeling any impartible processes. Further, the ’instantiation’ of this template for ten different processes was presented, demonstrating its generality.

The so-called graph designer workflow was presented to generate semantic RDF data. The tools part of the workflow is available publicly in [

51]. The gap between domain and ontology experts is reduced, making interaction easier using the presented interview template. The workflow is designed to make the user interaction steps easy and intuitive. Users can design the schema describing processes in the interview template and later in a GUI without mastering any schema languages. Tools are designed to convert the GUI template to Excel files, which are used for data input. Here, users can instantiate data in a flat hierarchy, unlike the requirement to preserve data hierarchy in workflows based on schema languages such as LinkML [

53] and JSON-Schema. These advantages have led to the adoption of the Graph Designer Workflow in digitalization efforts like AluTrace (referenced as the Fraunhofer IWM toolchain [

54,

55,

56]), iBain [

45], Urwerk [

47], H2Digital [

57], etc.

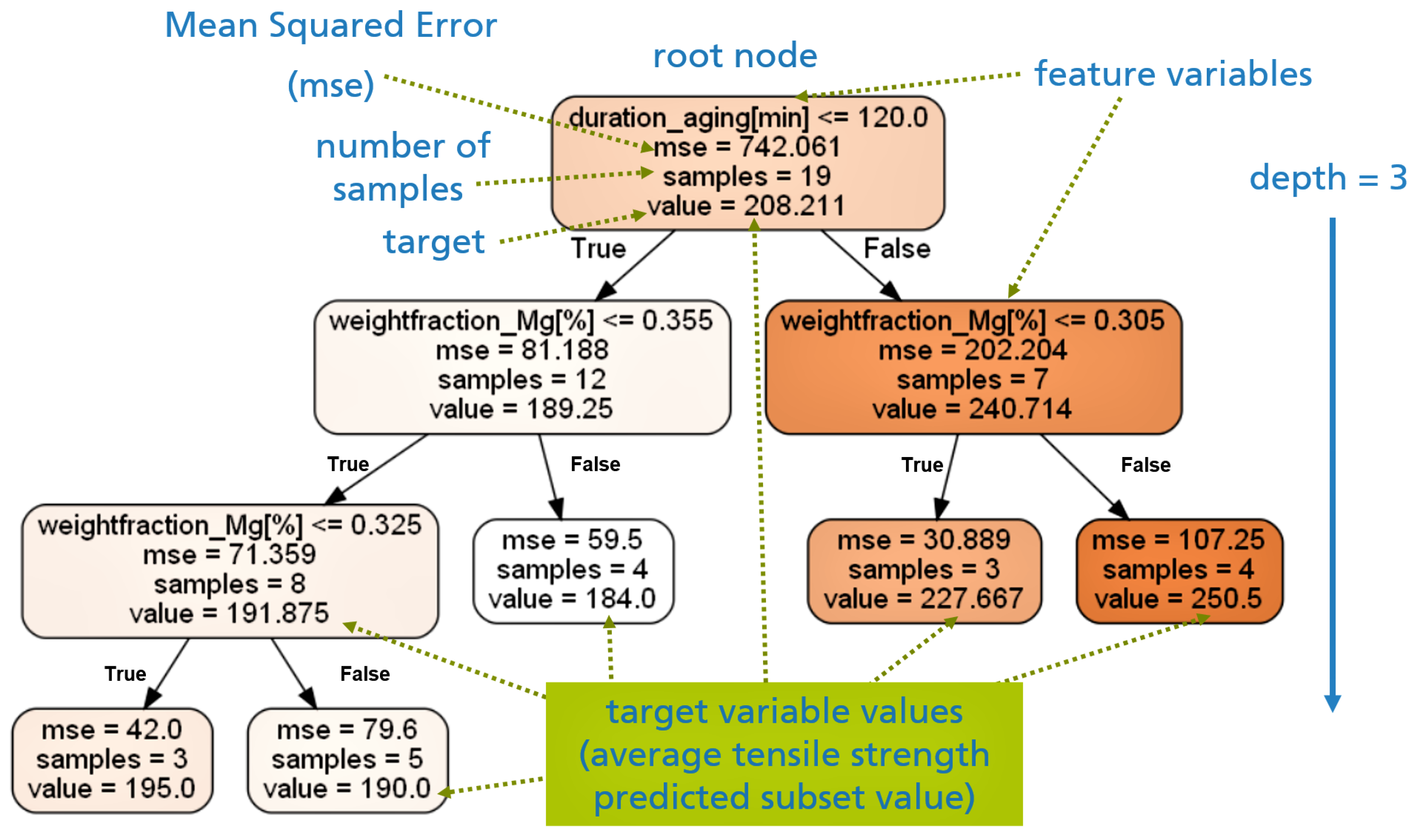

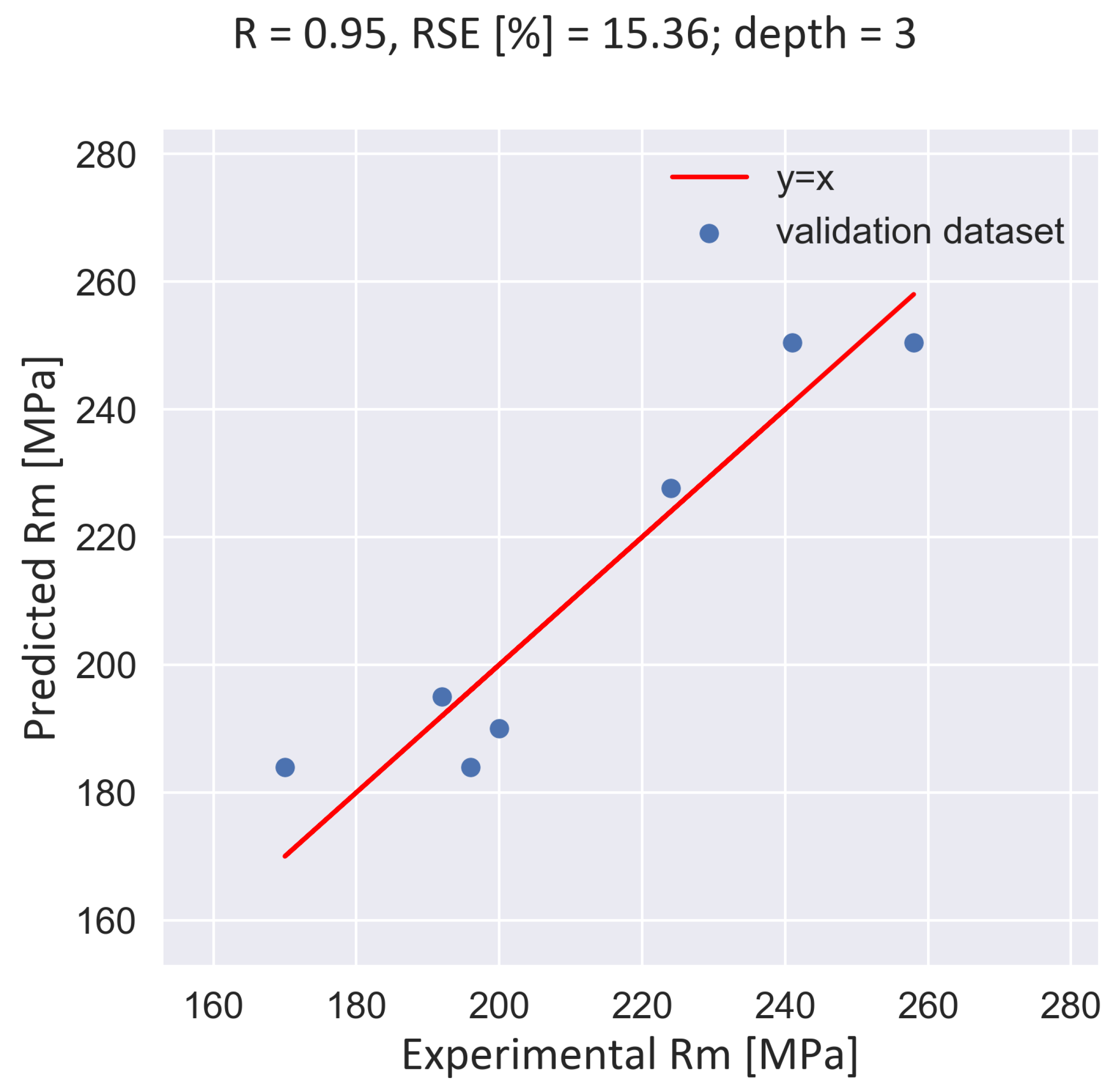

A simple and interpretable machine learning model is designed to demonstrate the benefit of creating semantic-rich MSE data. A decision regression tree model is used to predict the maximum tensile strength as a function of heat treatment and chemical composition.

This work successfully accelerates materials discovery by digitalizing data from material process chains using a generic methodology. The resulting knowledge graphs adhere to the FAIR principles and provide a valuable resource for materials-domain experts. Future work will focus on addressing the challenges of semantic data modeling and further improving the user experience.

Figure 1.

The BWMD process instance modeling philosophy: BFO classes depicted in black, BWMD classes in green, and BWMD object properties in red.

Figure 1.

The BWMD process instance modeling philosophy: BFO classes depicted in black, BWMD classes in green, and BWMD object properties in red.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the permanent mold casting process including the ingot as input and the cast part as output.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the permanent mold casting process including the ingot as input and the cast part as output.

Figure 3.

The Graph Designer Workflow. Extended documentation regarding its application and tools can be found in [

29].

Figure 3.

The Graph Designer Workflow. Extended documentation regarding its application and tools can be found in [

29].

Figure 4.

Detail of the interview Excel sheet regulating the information exchange between the domain expert and the ontology developer: one section of the interview is reserved for collecting the list of parameters that determine a specific outcome of the process to be modeled, in the BWMD Ontology referred to through the class ProcessControlParameters.

Figure 4.

Detail of the interview Excel sheet regulating the information exchange between the domain expert and the ontology developer: one section of the interview is reserved for collecting the list of parameters that determine a specific outcome of the process to be modeled, in the BWMD Ontology referred to through the class ProcessControlParameters.

Figure 5.

The generic Process Graph template: a common pattern to describe a process.

Figure 5.

The generic Process Graph template: a common pattern to describe a process.

Figure 6.

Details of the Excel template for metadata acquisition: 1.) user_variables: user view including the node names of the literals from the process graphs; 2.) gdtriples: logic of the process graph; 3.) namespaces: ontology IRI and namespace.

Figure 6.

Details of the Excel template for metadata acquisition: 1.) user_variables: user view including the node names of the literals from the process graphs; 2.) gdtriples: logic of the process graph; 3.) namespaces: ontology IRI and namespace.

Figure 7.

Exemplary use of the {1..n} construct with the example of user-specific duplication of chemical elements within a chemical composition.

Figure 7.

Exemplary use of the {1..n} construct with the example of user-specific duplication of chemical elements within a chemical composition.

Figure 8.

Description of the assignment of an ID and chemical composition to a cast part.

Figure 8.

Description of the assignment of an ID and chemical composition to a cast part.

Figure 9.

Description of process parameters and handling of physical quantities and unit symbols.

Figure 9.

Description of process parameters and handling of physical quantities and unit symbols.

Figure 10.

Visualization of the complete knowledge graph.

Figure 10.

Visualization of the complete knowledge graph.

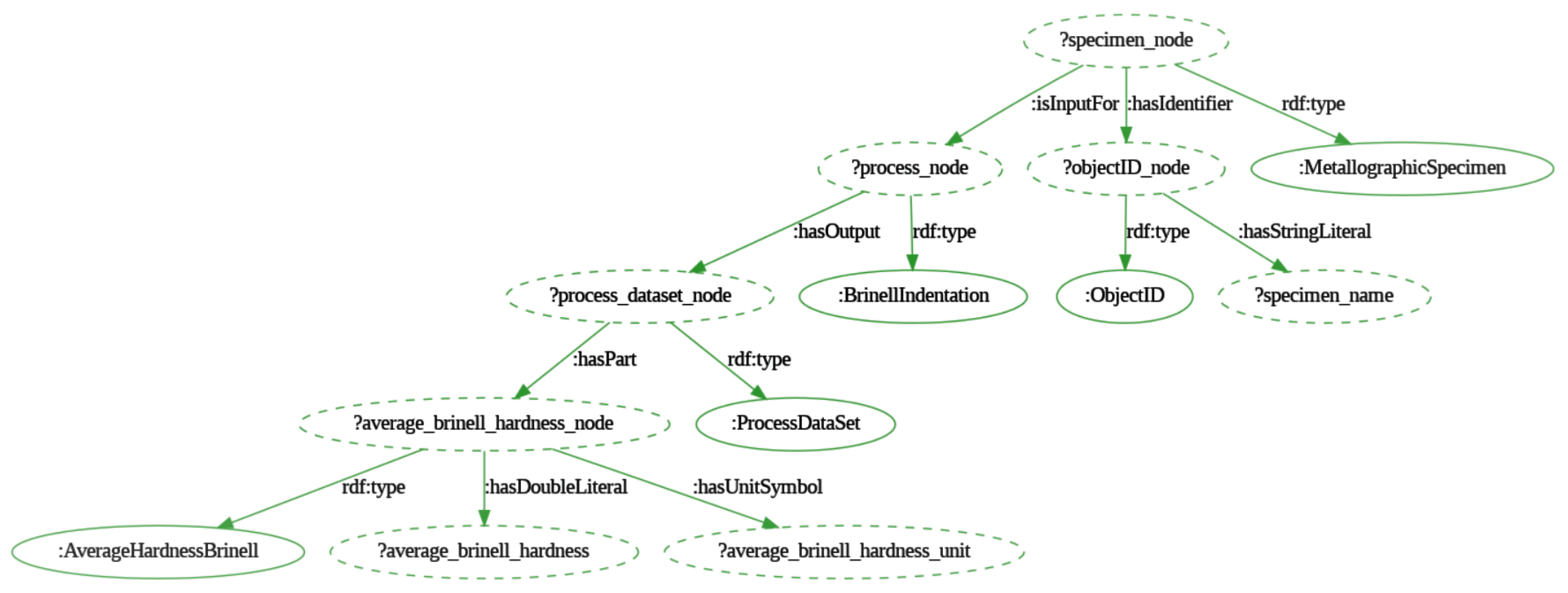

Figure 11.

Visualization of Brinell hardness SPARQL query algorithm.

Figure 11.

Visualization of Brinell hardness SPARQL query algorithm.

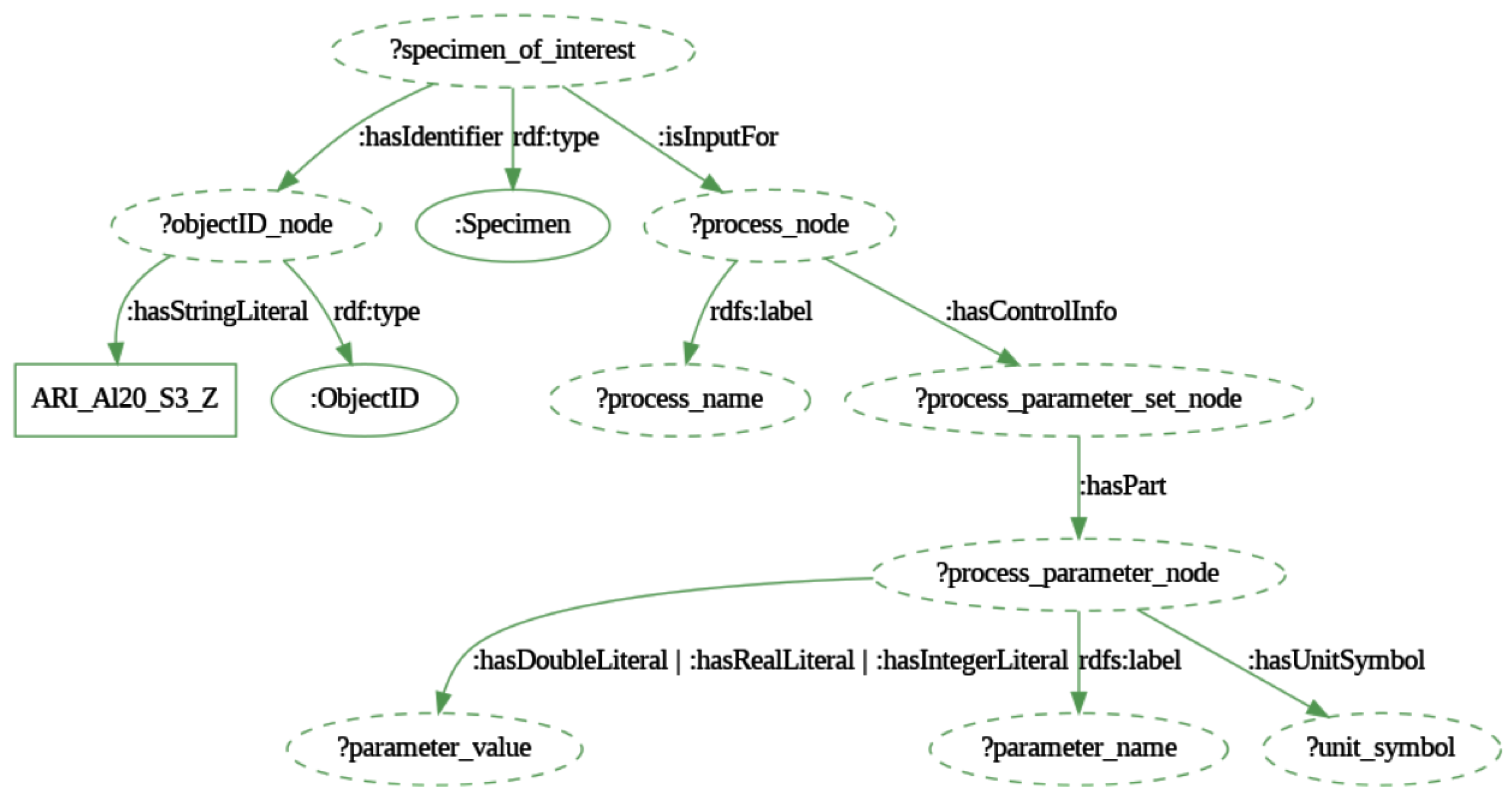

Figure 12.

Visualization of the SPARQL query algorithm the process control parameters corresponding to one specific object identifier.

Figure 12.

Visualization of the SPARQL query algorithm the process control parameters corresponding to one specific object identifier.

Figure 13.

Visualization of the process chain for the object

ARI_Al6 with the help of the GraphDB software frontend for graph visualization [

32].

Figure 13.

Visualization of the process chain for the object

ARI_Al6 with the help of the GraphDB software frontend for graph visualization [

32].

Figure 14.

Using a decision tree to predict the tensile strength of the cast AlSi10Mg based on process chain graph data.

Figure 14.

Using a decision tree to predict the tensile strength of the cast AlSi10Mg based on process chain graph data.

Figure 15.

Validation of the trained DecisionTreeRegressor model with a correlation coefficient of 0.95 and a relative standard error (RSE) of the slope equal to 15.36 %.

Figure 15.

Validation of the trained DecisionTreeRegressor model with a correlation coefficient of 0.95 and a relative standard error (RSE) of the slope equal to 15.36 %.

Table 1.

List of digitalized processes and corresponding BWMD Ontology class in the BWMD dataset.

Table 1.

List of digitalized processes and corresponding BWMD Ontology class in the BWMD dataset.

| Process |

Category |

| permanent mold casting |

bwmd:PermanentMoldCasting |

| 3D X-ray computer tomography |

bwmd:ThreeDimensionalXRayComputerTomography |

| wire eroding |

bwmd:WireEroding |

| turning |

bwmd:Turning |

| separating |

bwmd:Separating |

| solution annealing |

bwmd:SolutionAnnealing |

| artificial aging |

bwmd:ArtificialAging |

| tensile test |

bwmd:QuasiStaticTensileTest |

| Brinell indentation |

bwmd:BrinellIndentation |

| casting simulation |

bwmd:CastingSimulation |

Table 2.

First five matches retrieved by the Brinell hardness SPARQL query.

Table 2.

First five matches retrieved by the Brinell hardness SPARQL query.

| specimen_name |

average_brinell_hardness |

average_brinell_hardness_unit |

| ARI_Al19_Stab4_R2 |

87.8 |

HB 2.5/62.5 |

| ARI_Al16_S4_R1 |

65.6 |

HB 2.5/62.5 |

| ARI_Al26_Stab16_R1 |

63.7 |

HB 2.5/62.5 |

| ARI_Al22_Stab8_R9 |

68.2 |

HB 2.5/62.5 |

| ARI_Al22_Stab8_R4 |

68.2 |

HB 2.5/62.5 |

Table 3.

Result of the control process parameters query for the specimen with object identifier ARI_Al20_S3_Z.

Table 3.

Result of the control process parameters query for the specimen with object identifier ARI_Al20_S3_Z.

| process_name |

parameter_name |

parameter_value |

unit_symbol |

| QuasiStaticTensileTest__1 |

CrossheadSeparationRate__1 |

3.0E-2 |

mm/s |

| QuasiStaticTensileTest__1 |

OriginalGaugeLength__1 |

9.79E+07 |

µm |

Table 4.

Level of importance for making predictions.

Table 4.

Level of importance for making predictions.

| Feature variable |

Level of importance [%] |

| duration_aging[min] |

91.4 |

| weightfraction_Mg[%] |

8.6 |

| temperature_aging[°C] |

0.0 |

| temperature_annealing[°C] |

0.0 |

| duration_annealing[min] |

0.0 |