Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

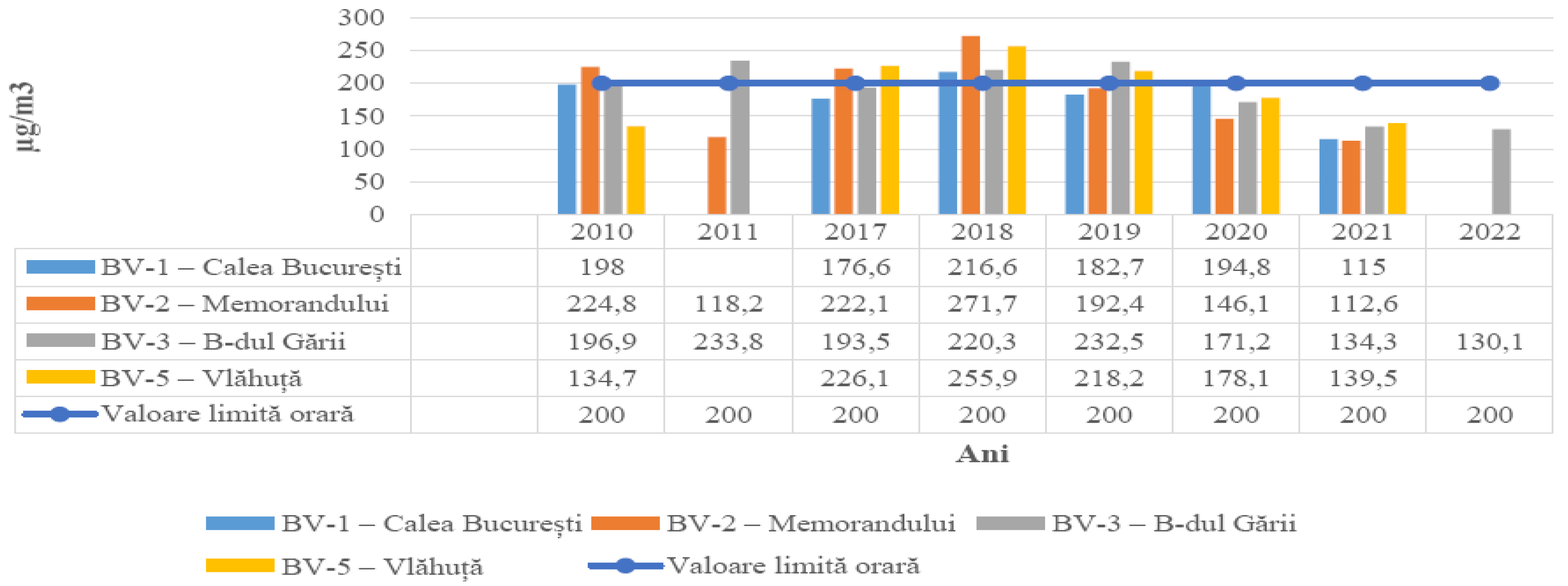

1. Background

- -

- Limit values 200 [μg/m3] NO2 - the hourly limit value for the protection of human health;

- -

- The annual limit value of 40 [μg/m3] NO2 for the protection of human health; and

- -

- Critical Level of 30 [μg/m3] NOx - for protection of fauna and flora;

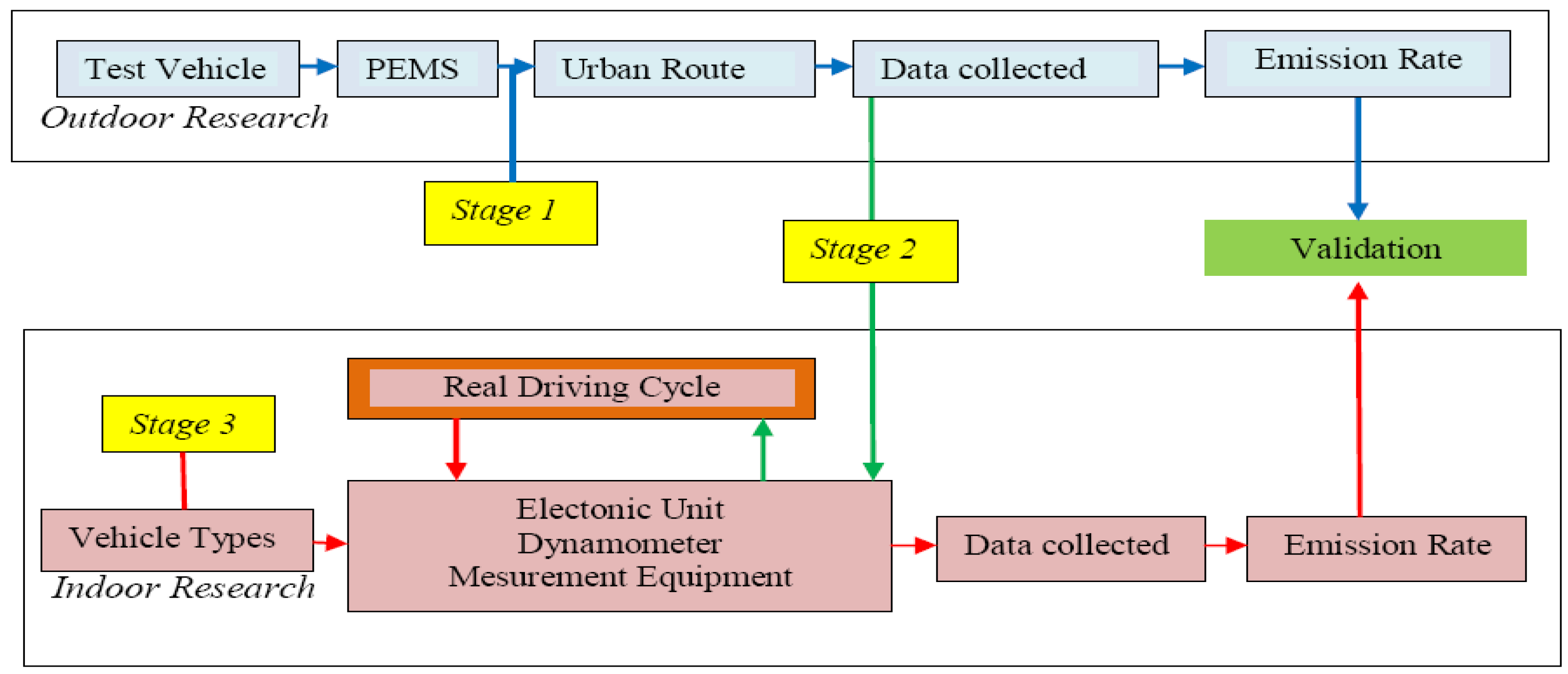

2. Methodology

2.1. Experimental Framework

- In order to achieve this objective, the experimental research will be carried out in three stages:

- In the first stage, data will be collected regarding traffic characteristics, emissions, and fuel consumption on the routes selected for the vehicles under consideration.

- In the second stage, the data recorded on the chosen routes are entered as input data in the Driving cycle software of the dynamometric stand to obtain the real driving cycles that represent the research objectives.

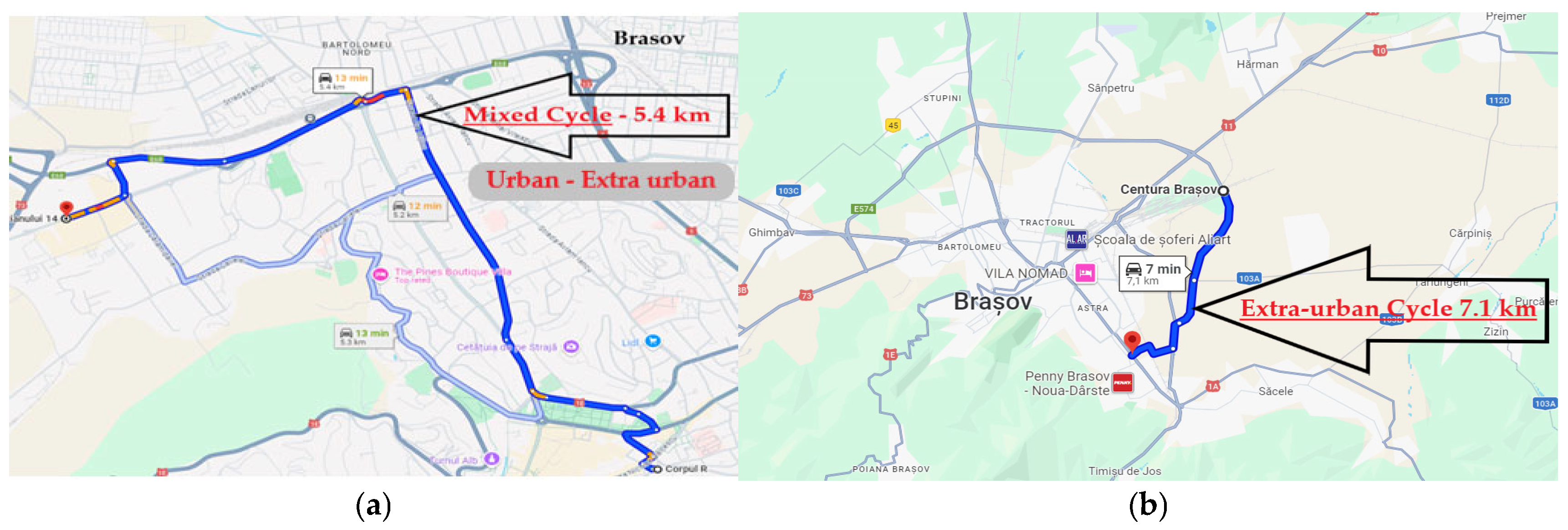

2.2. Analysis of Representative Test Routes

| Route Characteristics | Mixed Route | Extra-urban Route |

|---|---|---|

| Traffic lighted intersections | 3 | - |

| Roundabout circulation | 8 | 5 |

| Intersections directed by road signs | 2 | 1 |

| Pedestrian crossings with traffic lights | 1 | - |

| Pedestrian crossings without traffic lights | 20 | 2 |

| Brasov bypass exits/entrances | - | 3 |

2.3. Test Vehicles and Their Characteristics

2.4. Traffic Conditions

2.5. Modelling of the Real Driving Cycle

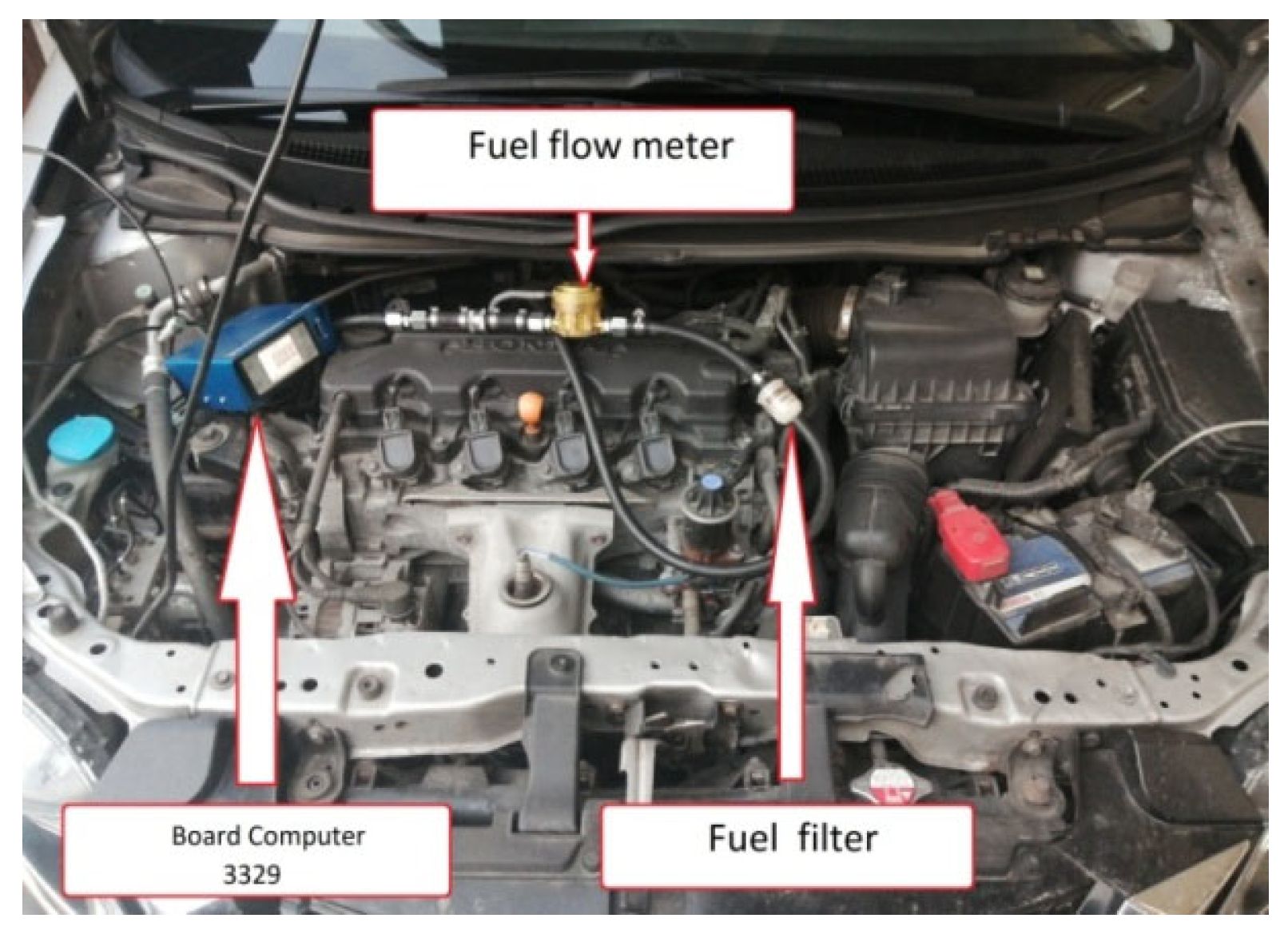

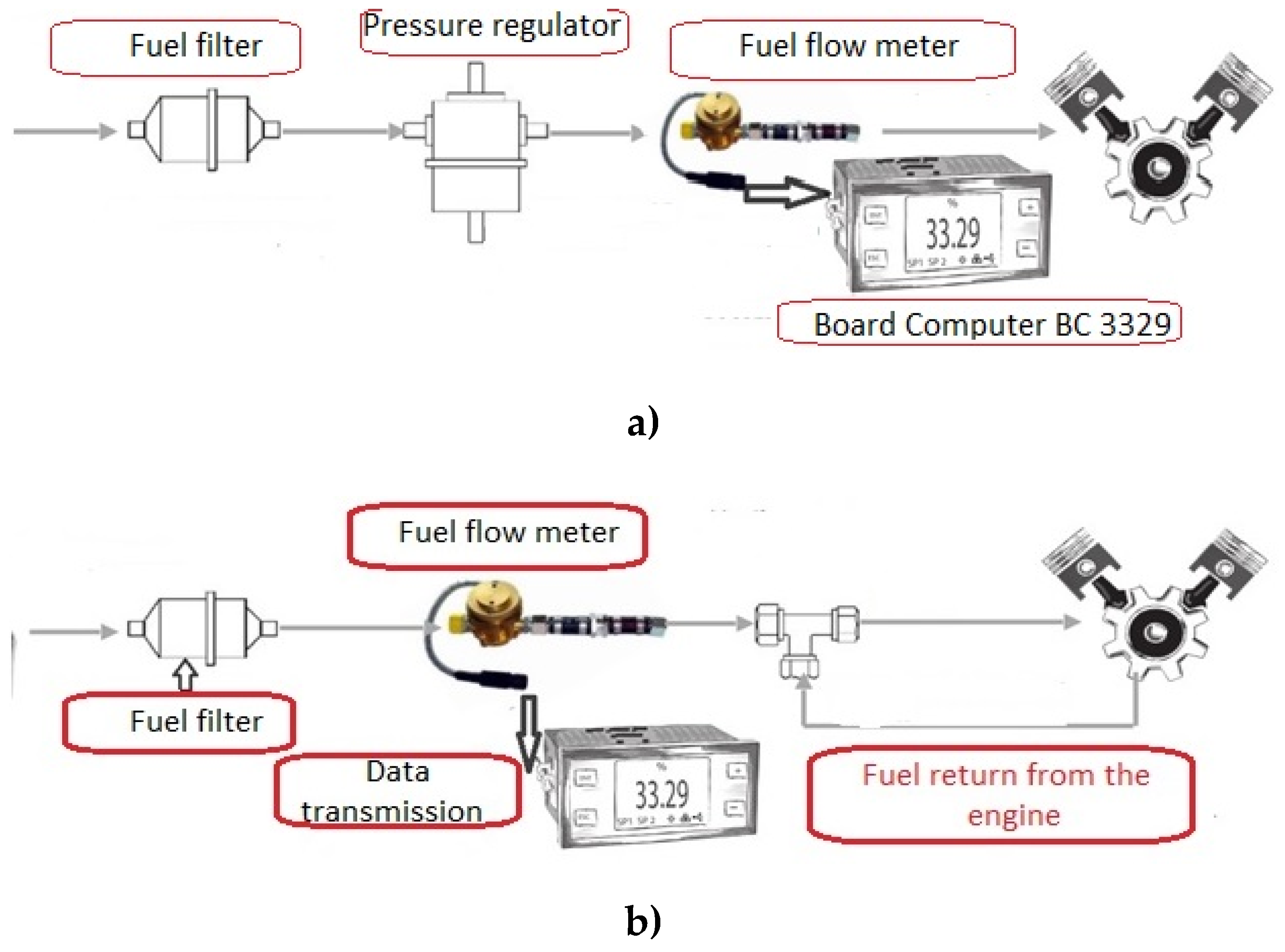

3. Measurement Equipments

3.1. On Board Measurement System

3.2. Dynamometric Bench for Measurement in the Laboratory

4. Analysis of Experiments and Results

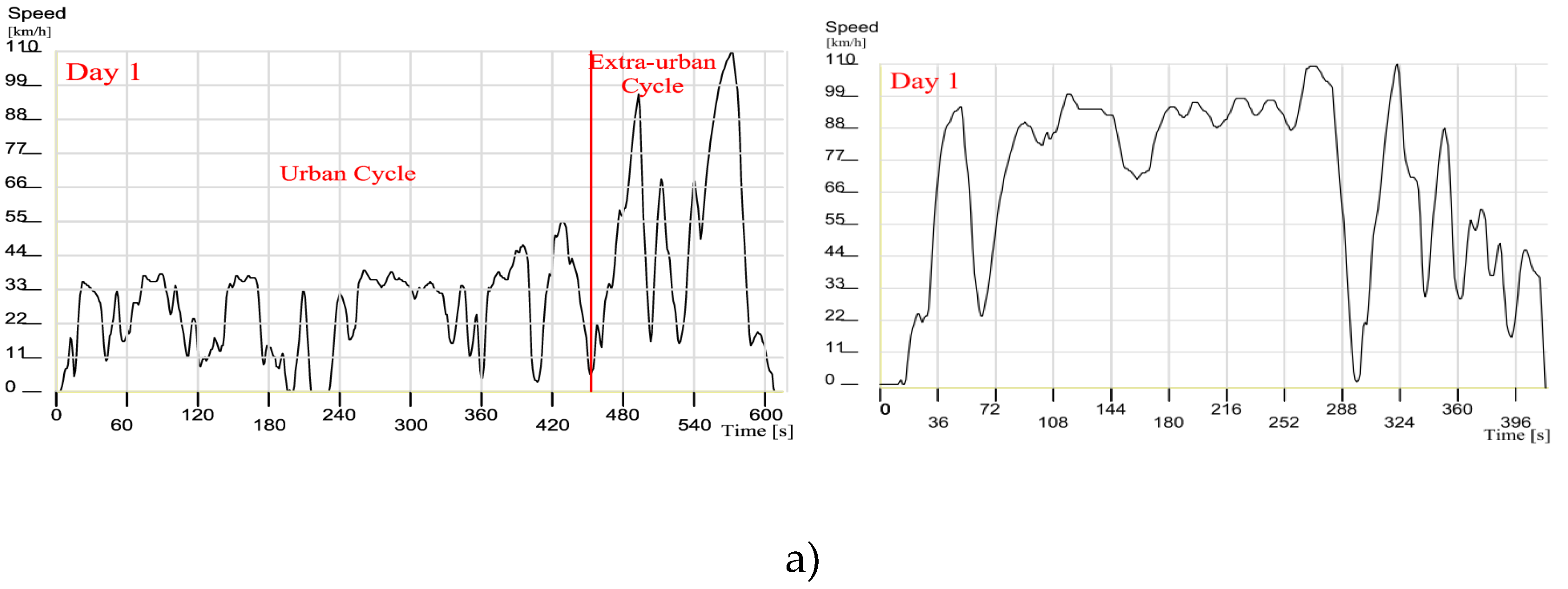

4.1. Real Modelled Driving Cycle

- -

- the duration of the route (5.4 km) of the four cycles varies from the shortest 528 [s] to the longest 692 [s], which shows a difference of 31.06 [%];

- -

- the total duration of the stops in the cycle is between 33 [s] and 120 [s] in the variation range, the other two cycles being included (of 72.50 [%]), this variation is induced by the number of stops and their duration;

- -

- the number of stops in the cycle is between 4 (1 cycle) and 9 (3 cycles), the range of variation being of 55.55 [%], and if it is related to the possible number of stops (34), they represent 11.76 [%] and 26.47 [%] respectively;

- -

- the average speed of traveling the entire distance of the cycle (5.4 km) with stops is between 28.10 [km/h] and 36.82 [km/h], the other cycles showing average speeds between these limits and representing a variation of 31.03 [% ];

- -

- the average speed of the urban route sector with the related stops was between 26.60 [km/h] and 33.60 [km/h], which represents a range of variation of 26.32 [%];

- -

- the average speed of the entire route of the mixed cycle with stops was between 28.10 [km/h] and 36.83 [km/h], the size of the interval where the other two cycles fall being of 23.70 [%].

- -

- the duration of the route (7.1 km) of the four cycles falls between 425 [s] and 481[s], which shows a difference of 13.18 [%];

- -

- the number of stops in the cycle varies depending on the test day, from 2 (2 cycles) to 4 (1 cycle) the range of variation being 100.00[%], and, if the number of stops is related to the possible number of stops (8), they represent 75.00 [%] and 50.00 [%] respectively, one of the cycle has 3 stops;

- -

- the total time allocated to stops in the cycle is between 13 [s] and 44 [s] in the variation range, being of 238.46 [%];

- -

- the average speed of the real extraurban cycle (7.1 km), taking into account the stops, is between 53.14 [km/h] and 60.17[km/h], and the other cycles showing average speeds between these limits of 56.22 [km/ h] respectively 58.10 [km/h]. The range of variation being of 13.23 [%].

- -

- the optimistic scenario, in this case the number of vehicles remains constant or increases slightly and an intelligent stop management system is implemented that can reduce the time allocated to trips and increase speeds, according to this scenario, short-duration cycles should be selected.

- -

- the pessimistic scenario in this situation, the number of vehicles will increase according to trends to the EU average value, and the stop management system remains unchanged, according to this scenario, cycles with long durations and low average speeds should be chosen.

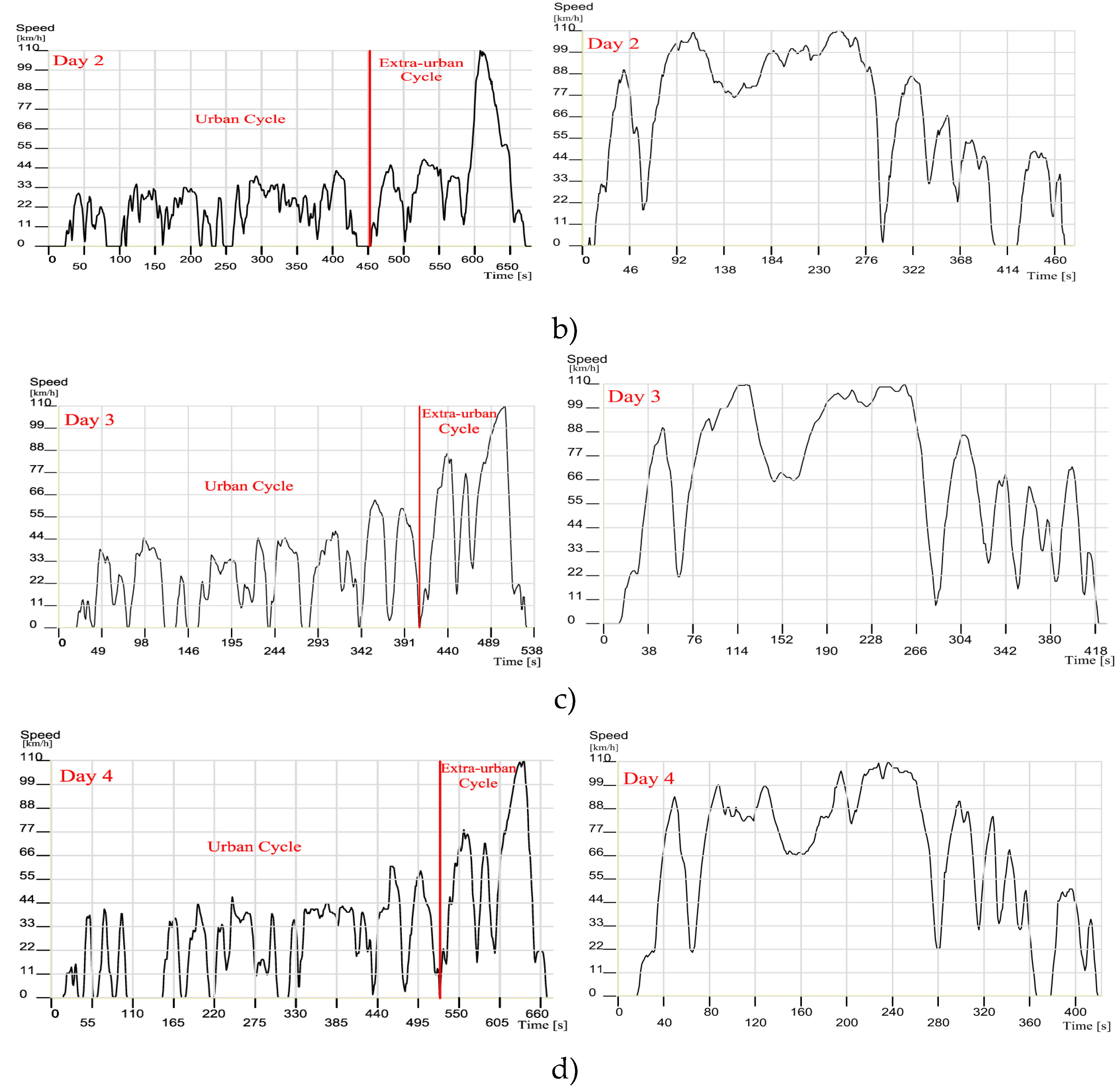

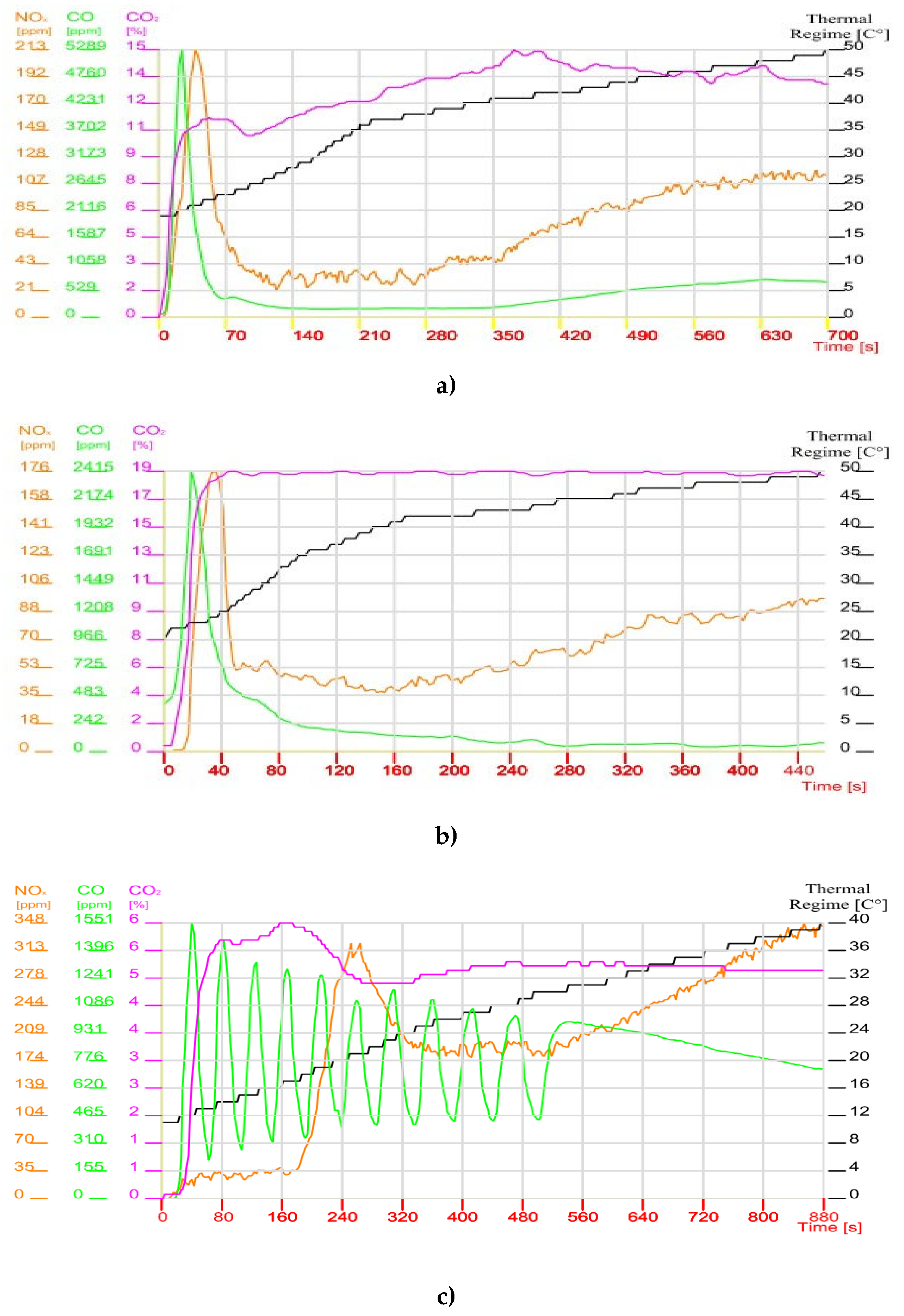

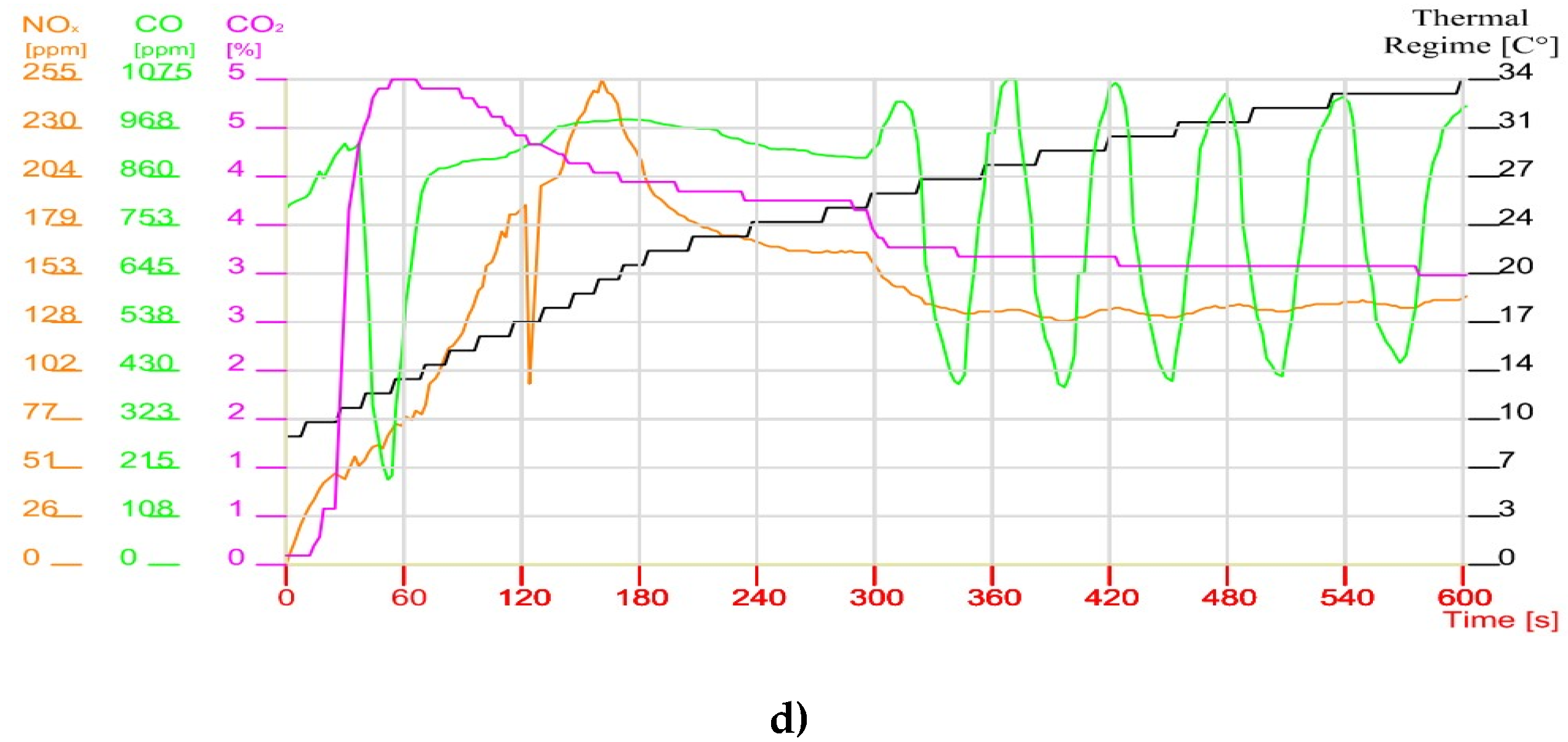

4.2. The Influence of Thermal Regime on Emissions When Idling

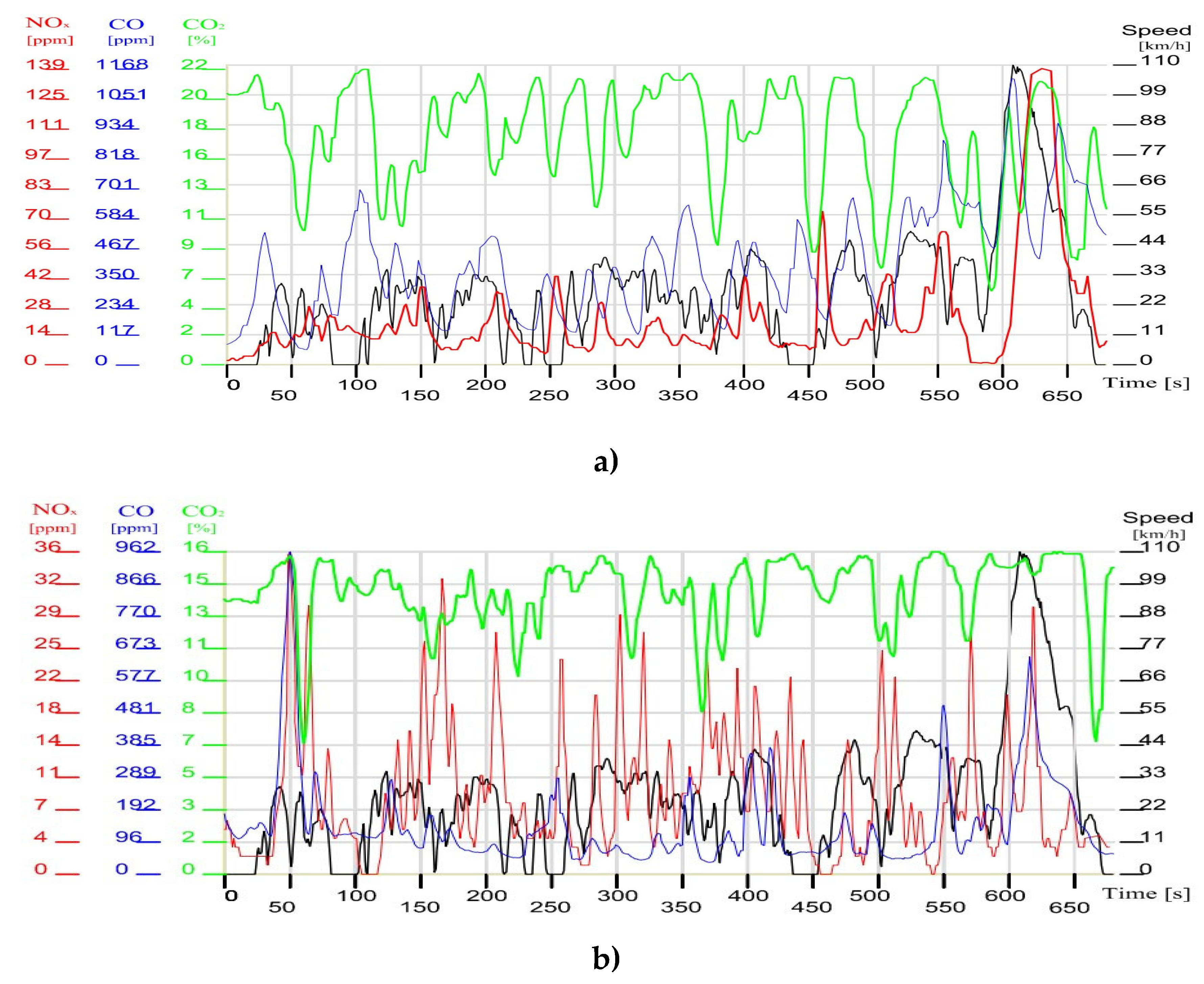

4.3. Emissions’ Results on Real Mixed and Extra-Urban Driving Cycle

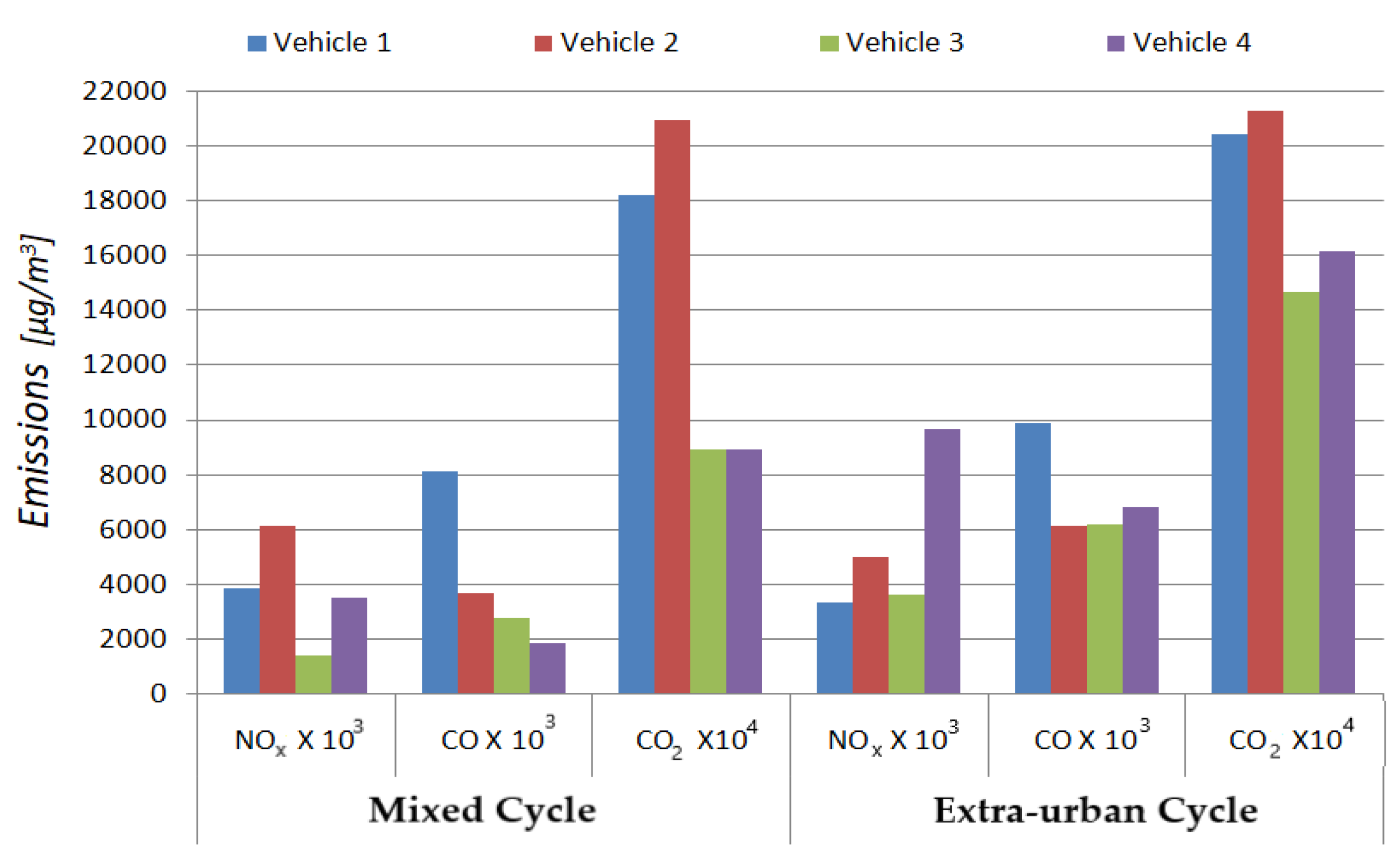

4.3.1. Emissions on Mixed Driving Cycle (M-BV Cycle)

4.3.2. Emissions on Extra-Urban Driving Cycle (E-BV Cycle)

| The Mixed Cycle (”M-BV Cycle”) | Extra-urban cycle (”E-BV Cycle”) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOx (x103) [μg/m3] |

CO (x103) [μg/m3] |

CO2 (x104) [μg/m3] |

NOx (x103) [μg/m3] |

CO (x103) [μg/m3] |

CO2 (x104) [μg/m3] |

|

| Vehicle 1 | 3867 | 8135 | 18199 | 3332 | 9922 | 20437 |

| Vehicle 2 | 6107 | 3685 | 20954 | 5003 | 6112 | 21306 |

| Vehicle 3 | 1406 | 2748 | 8927 | 3619 | 6203 | 14704 |

| Vehicle 4 | 3519 | 1846 | 8941 | 9675 | 6835 | 16195 |

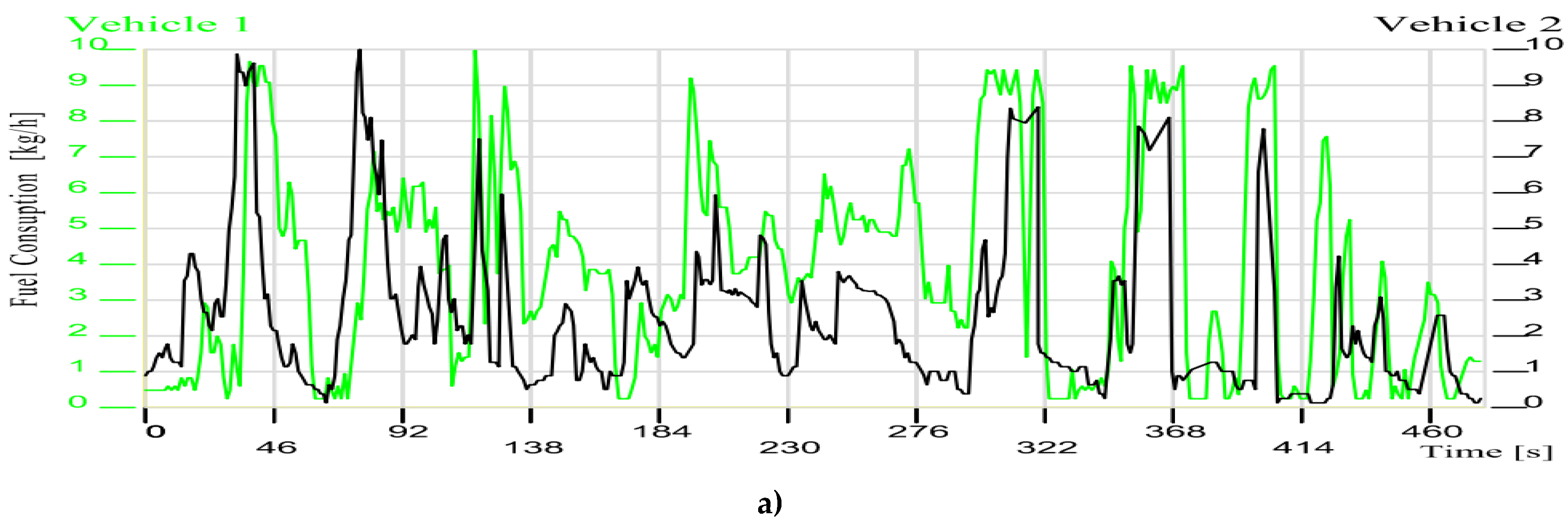

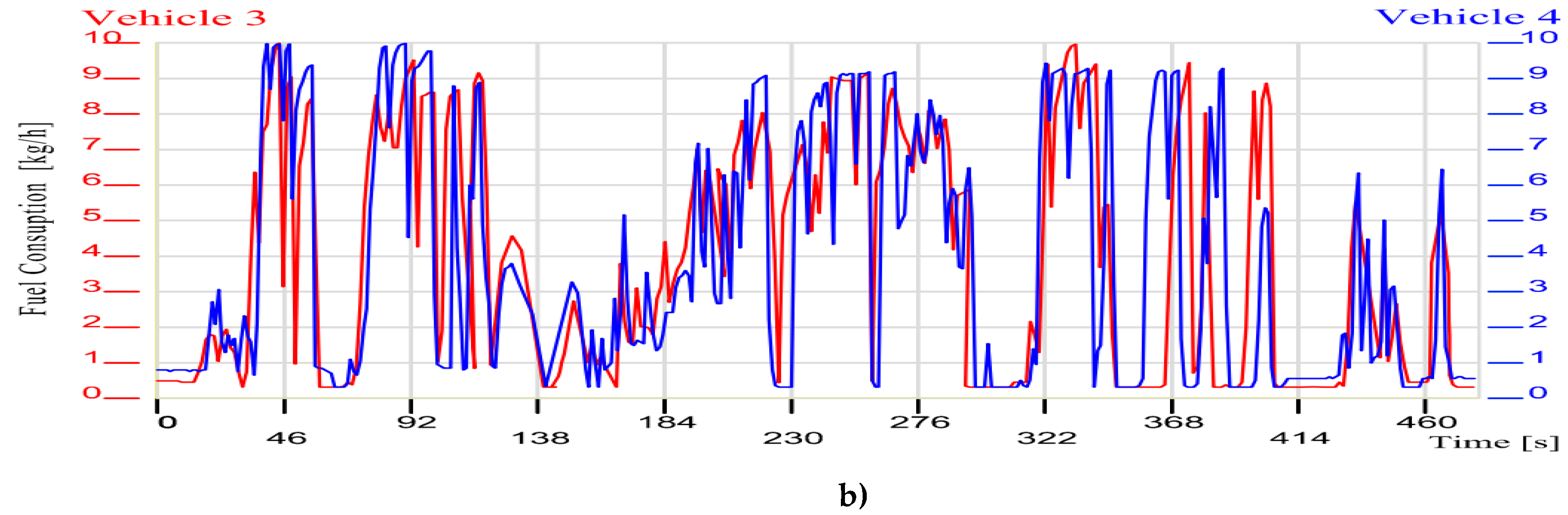

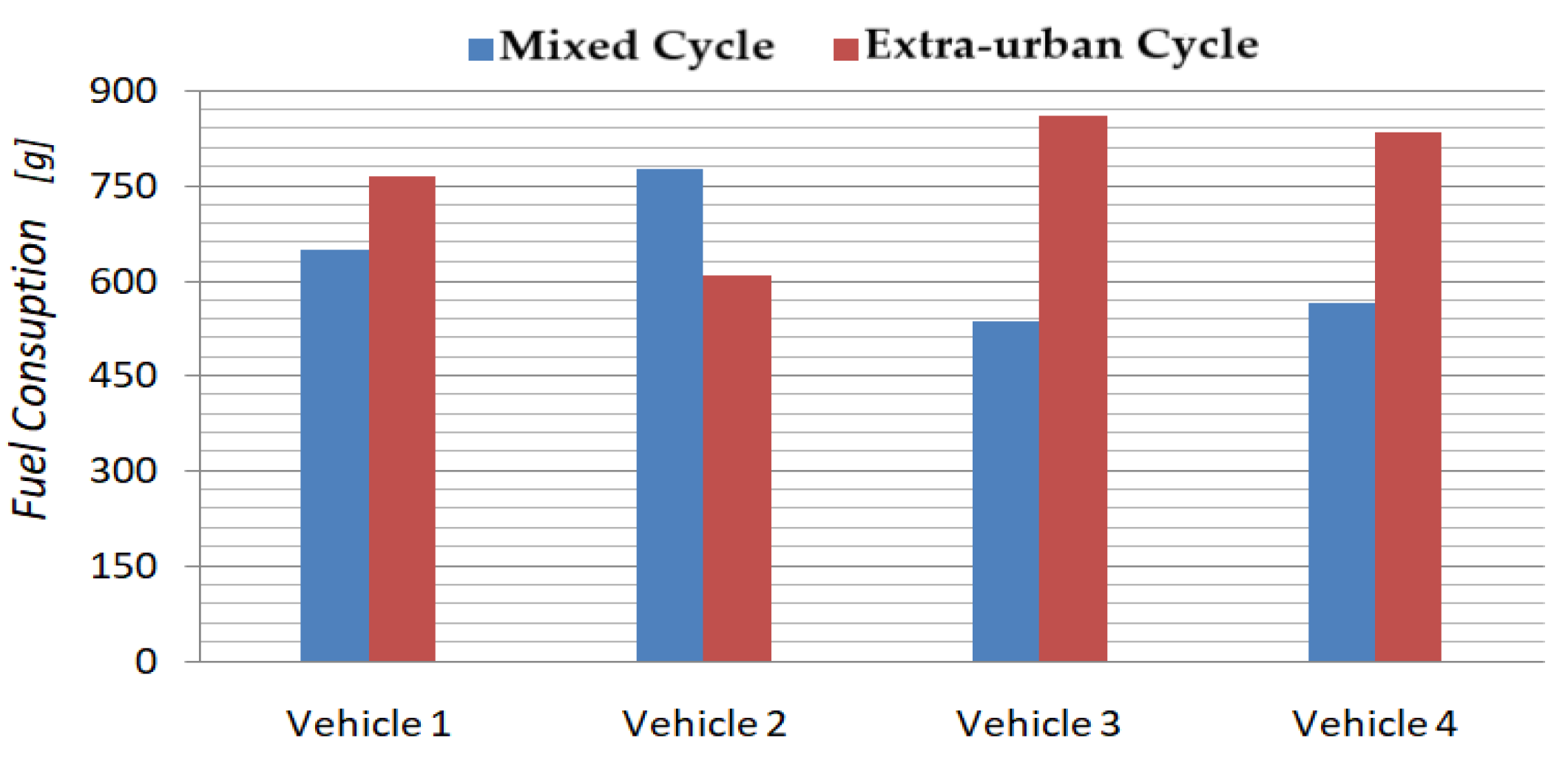

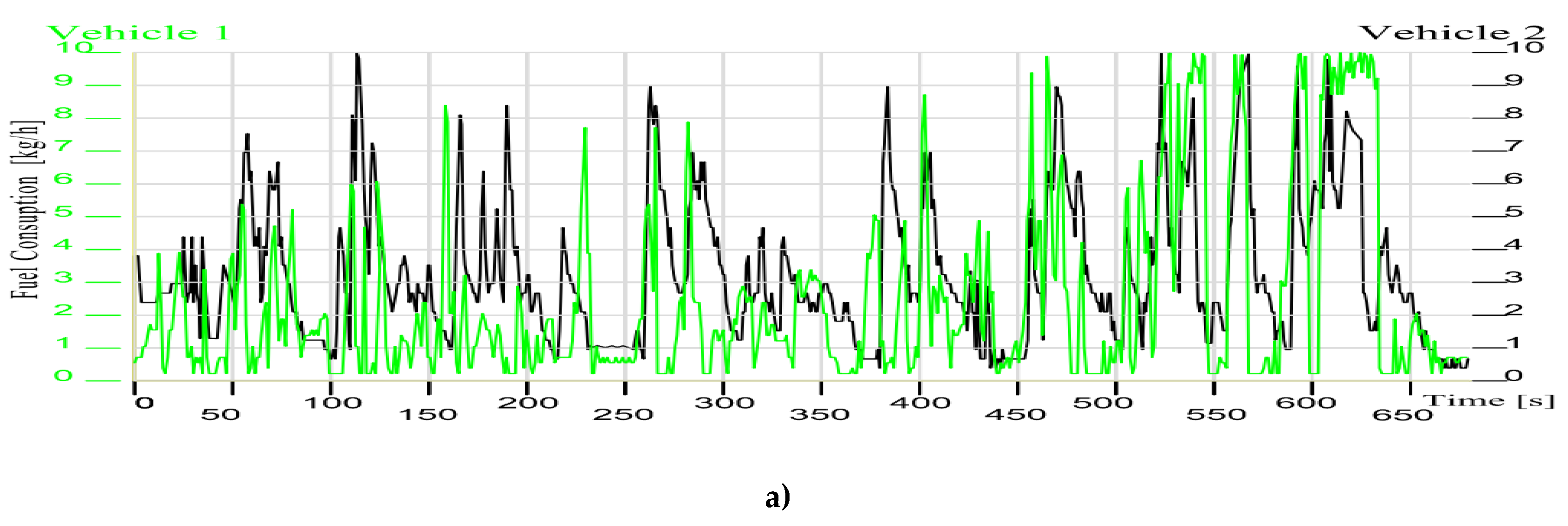

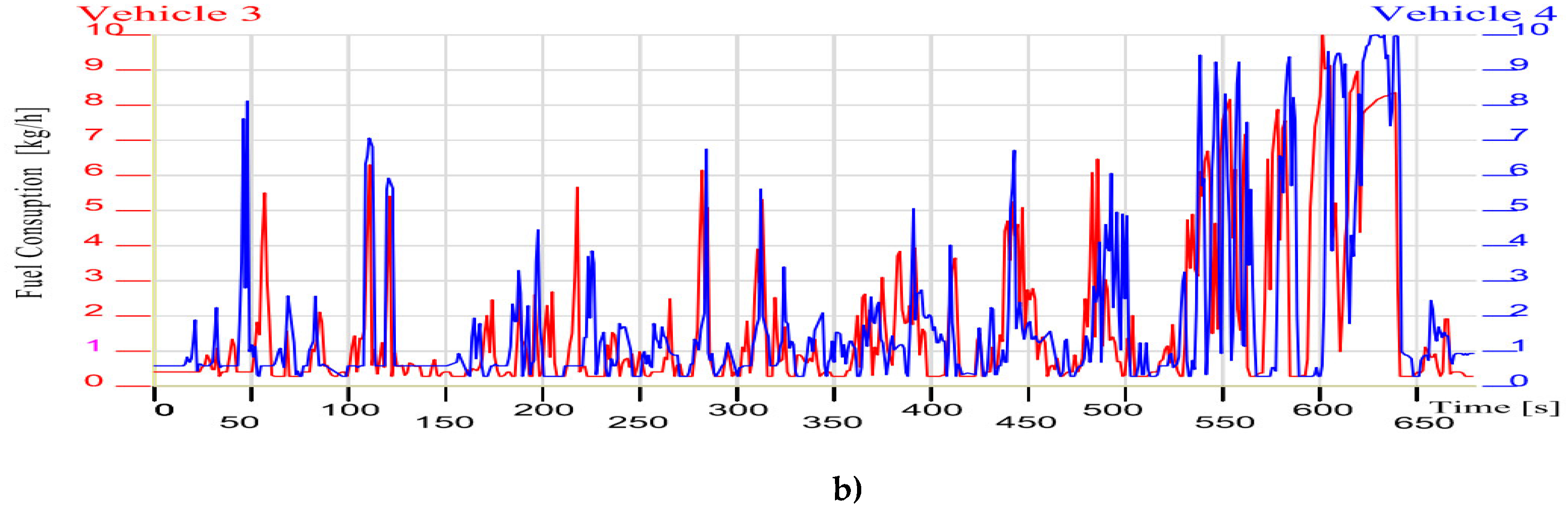

4.3.3. Fuel Consumption Results

| Cycle | Mixed Cycle (”M - BV Cycle”) | Extra-urban Cycle (”E-BV Cycle”) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M.U. | [g] | [kg/h] | [l/h] | [g] | [kg/h] | [l/h] |

| Vehicle 1 | 649 | 3.38 | 4.51 | 765 | 5.73 | 7.64 |

| Vehicle 2 | 776 | 4.04 | 5.39 | 609 | 4.56 | 6.08 |

| Vehicle 3 | 538 | 2,80 | 3.73 | 860 | 6.44 | 8.59 |

| Vehicle 4 | 566 | 2,94 | 3.92 | 834 | 6.24 | 8.32 |

5. Discussion

5.1. Selecting Routes and Modelled Test Driving Cycles

- -

- Transport is carried out in limited road spaces, which have fixed dimensions; it is not possible to store unused road capacity for use over periods of higher demand.

- -

- "Derived" transport demand, in this case, trips are not made for the sake of the desire to travel, but are generated by the need to move to places where different types of activities are carried out, such as, work, shopping, studies, recreation, relaxation etc., in different locations;

- -

- Transport demand is highly variable and shows peak periods that concentrate a large number of journeys in a short period of time due to the desire to make the best use of the time available for those various activities.

5.2. Vehicle Emissions and Fuel Consumption During Real Driving Cycles

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/1151 of 1 June 2017 supplementing Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council on type-approval of motor vehicles with respect to emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/1151/oj.

- Liqiang, H.; Jingnan, H.; Shaojun, Z.; Ye, W.; Rencheng, Z.; Lei, Z.; Xiaofeng, B.; Yitu, L.; Sheng, S. The impact from the direct injection and multi-port fuel injection technologies for gasoline vehicles on solid particle number and black carbon emissions. Applied Energy 2018, 226, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernotte, J.; Najt, P.; and Durrett, R. Downsized-Boosted Gasoline Engine with Exhaust Compound and Dilute Advanced Combustion. SAE Int. J. Adv. & Curr. Prac. in Mobility 2020, 2, 2665–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Liu, J.; Tan, Y.; Luo, B.; Guo, G. Influence of single injection and two-stagnation injection strategy on thermodynamic process and performance of a turbocharged direct-injection spark-ignition engine fuelled with ethanol and gasoline blend. Applied Energy 2018, 228, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola, C.; Martín, J.; Pla, B.; Bares, P. Cycle by cycle NOx model for diesel engine control. Applied Thermal Engineering 2017, 110, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Überall, A.; Otte, R.; Eilts, P.; Krahl, J. A literature research about particle emissions from engines with direct gasoline injection and the potential to reduce these emissions. Fuel 2015, 147, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, M.; Najafi, G.; Ghobadian, B.; Yusaf, T. Performance and emission characteristics of a CI engine using nano particles additives in biodiesel-diesel blends and modelling with GP approach. Fuel 2017, 202, pp. 699–716, ISSN: 0016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergueta, C.; Bogarra, M.; Tsolakis, A.; Essa, K.; Herreros, J.M. Butanol-gasoline blend and exhaust gas recirculation, impact on GDI engine emissions. Fuel 2017, 208, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, D.R.; Athanasios, M.D.; Evangelos, G.G.; Dimitrios, C.R. Investigating the emissions during acceleration of a turbocharged diesel engine operating with bio-diesel or n-butanol diesel fuel blends. Energy 2010, 35, 5173–5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinhui, W.; Rong, Z.; Yanhong, Q.; Jianfei, P.; Mengren, L.; Jianrong, L. The impact of fuel compositions on the particulate emissions of direct injection gasoline engine. Fuel 2016, 166, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpica, D. Coefficient of Engine Flexibility as a Basis for the Assessment of Vehicle Tractive Performance. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2019, 39, https:doi.org/10.1186/s10033–019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dumitrescu, C. Flame development analysis in a optical engine converted to spark ignition natural gas operation. Applied Energy 2018, 230, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.F.; Liang, Z.R.; Zhang, X.; Shuai, S.J. Characterizing particulate matter emissions from GDI and PFI vehicles under transient cold-startand cold start condition. Fuel 2017, 189, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarulescu, S.; Cofaru, C.; Tarulescu, R. Cold Engine’s Operating Regime Influence over the Exhaust Emissions. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2016, 822, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liye, B.; Jihua, W.; Lihui, S.; Haijun, C. Exhaust Gas After-Treatment Systems for Gasoline and Diesel Vehicles. International Journal of Automotive Manufacturing and Materials 2022, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Uditha, G.; Loshaka, P.; Saman, B. Developing a General Methodology for Driving Cycle Construction: Comparison of Various Established Driving Cycles in the World to Propose a General Approach. Journal of Transportation Technologies 2015, 5(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.Y.; Hung, W.T. On-Road Motor Vehicle Emissions and Fuel Consumption in Urban Driving Conditions. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2011, 50, 543–554, ISSN 1047-3289. [Google Scholar]

- Kęska, A. The Actual Toxicity of Engine Exhaust Gases Emitted from Vehicles: The Development and Perspectives of Biological and Chemical Measurement Methods. ACS Omega. 2023, Jul 18; Vol.8, Issue 28, pp 24718–24726. [CrossRef]

- Principles of calculating results by the Madur Gas Analysers, Madur Electronics, 07/2007. Available online: www.madur.com.

- User’s manual for CAP 3201, EMISSION STATION, Capelec Ergonomics Efficency Simplicity. Available online: www.capelec.fr.

- Andrew, R.; Richard, B.; Shipway, P. Internal combustion engine cold-start efficiency: A review of the problem, causes and potential solutions. Energy Conversion and Management 2014, 82, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelos, G.; Giakoumis, T.; George, T. Analysis of the Effect of Vehicle, Driving and Road Parameters on the Transient Performance and Emissions of a Turbocharged Truck. Energies 2018, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmankhah, B.; Macedo, E.; Fernandes, P.; Coelho, M. Micro driving behaviour in different roundabout layouts: Pollutant emissions, vehicular jerk, and traffic conflicts analysis. Transportation Research Procedia 2022, 62, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofaru, C. Autovehiculul si poluarea mediului:evaluare si control. Editura Universitatii “Transilvania Brasov”, 2015 ISBN 978-606-19-0666-6.

- Guanfeng, Y.; Mingnian, W.; Tao, Y. Pengcheng Qin Effects of traffic patterns on vehicle pollutant emission factors in road tunnels. Tunnelling and Underground, Space Technology 2022, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A.; Charles, A.; Gift, D.; Atinuke, O. The Impact of Vehicle Engine Characteristics on Vehicle Exhaust Emissions for Transport Modes in Lagos City. Urban, Planning and Transport Research. Open Access Journal 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.; Mahmoud, E.; Khaled, Z.; Fabio, T.; Ibrahim, S. Effect of Road, Environment, Driver, and Traffic Characteristics on Vehicle Emissions in Egypt. International Journal of Civil Engineering 2022, 20, 1261–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, I.; Steven, B.; Ronghui, L. Modelling instantaneous traffic emission and the influence of traffic speed limits. Science of the Total Environment 2006, 371, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Hamid, A. Investigating the Effect of Traffic Flow on Pollution, Noise for Urban Road Network. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 961, 012067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, P.; Sharad, G.; Aloke, G. Evaluating effects of traffic and vehicle characteristics on vehicular emissions near traffic intersections. Transportation Research Part D:Transport and Environment 2013, 23, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarić, A.; Sulejmanović, S.; Albinović, S.; Pozder, M.; Ljevo, Ž. The Role of Intersection Geometry in Urban Air Pollution Management Air Pollution Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, M.; Cuzmin, C.; Șerban, C.; Munteniță, C. The impact of road transport emissions on air quality in Brăila, Romania. PESD 2021, Volume 15.

- Vladimir, S.; Aleksandr, I.; Slobodi, M. Studying the Relationship between the Traffic Flow Structure, the Traffic Capacity of Intersections, and Vehicle-Related Emissions. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katarzyna, B.; Zdzisław, C.; Krystian, S.; Magdalena, Z. The Influence of the Properties of Vehicles Traffic on the Total Pollutant Emission. Zeszyty Naukowe Instytutu Pojazdów, Instytut Pojazdów Politechniki Warszawskiej, Proceedings of the Institute of Vehicles 2017, Volume 1, pp. 89–102. Available online: https://repo.pw.edu.pl/info/article.

- Fangfang, Z.; Jie, L.; Henk, Z.; Chao, L. Influence of driver characteristics on emissions and fuel consumption. Transportation Research Procedia 2017, 27, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, N.; Demetris, D.; Elena, T.; Athanasios, M. Analyzing the Requirements for Smart Pedestrian Applications: Findings from Nicosia, Cyprus. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1950–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230530-1.

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20240117-1.

- Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/452238/europe-eu-28-number-of-cars-per-1000-inhabitants/.

- Available online: https://www.acea.auto/figure/per-capita-new-car-registrations-by-eu-country/.

- Available online: https://statzon.com/insights/e-mobility-europe-an-overview-of-europes-latest-electric-vehicles-data.

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Transport_equipment_statistics.

- Available online: https://www.brasovcity.ro/filezone/mediu/planuriactiune/aer/Plan%20Integrat%20de%20Calitate%20a%20Aerului%20in%20Municipiul%20Brasov%202023-2027.pdf.

| Car | Vehicle 1 (SIE) | Vehicle 2 (SIE) | Vehicle 3 (CIE) | Vehicle 1 (CIE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car Model | SUV | Sedan | Van | Sedan |

| Turbo | Variable geometry | Turbo | ||

| Start & Stop | turbine | Start & Stop | ||

| Catalyst | Three-way catalytic converter |

Three-way catalytic converter |

Oxidation catalyst +SCR |

Oxidation catalyst +SCR |

| Displacement [cm3], (Power [HP]), Gearbox (manual/automatic) | 1.2 PureTech (130 HP), Automatic |

1798 (142 HP), Manual. |

1499 (119HP) Manual |

1461 (75HP) Manual |

| Manufacturing | 2019 | 2017 | 2019 | 2019 |

| Mileage [km] | 30641 | 27321 | 36567 | 33541 |

| Imput parameters-Stand Maha | LPS 3000 MAHA | |||

| Air density [kg/m3] | 1.1 | |||

| The angle of inclination | 0 | |||

| Table of the stand rollers | 200 | |||

| Cf A [KW] | 3.46 | 4.75 | 5.87 | 4.05 |

| Cf B [KW] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cf C [KW] | 12.38 | 8.75 | 11.2 | 11.92 |

| Mass of vehicle [Kg] | 1050 | 1440 | 1780 | 1229 |

| Mixed Cycles | Extra-Urban Cycles | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle characteristics | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | |||||

| Cycle | M-1 Cycle | M-2 Cycle | M-3 Cycle | M-4 Cycle | E-1 Cycle | E-2 Cycle | E-3 Cycle | E-4 Cycle | |||||

| Distance [km] | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | |||||

| Time cycle [s] | 610 | 692 | 528 | 682 | 440 | 481 | 425 | 455 | |||||

| Urban | Extra-urban [s] | 460 | 150 | 440 | 252 | 412 | 116 | 528 | 154 | - | - | - | - |

| Number of stops | 4 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Time stops [s] | 33 | 107 | 75 | 120 | 13 | 44 | 17 | 33 | |||||

| Maximum speed [km/h] | 111 | 109 | 110 | 109 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 | |||||

| Average speed with stops [km/h] | 31.87 | 28.10 | 36.83 | 28.51 | 58.10 | 53.14 | 60.17 | 56.22 | |||||

| Average speed without stops [km/h] | 33.68 | 33.23 | 42.93 | 34.59 | 59.86 | 58.53 | 62.66 | 60.58 | |||||

| Vehicle Test | M-BV Cycle | E-BV Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle 1 (Gasoline) | 11 - 47 [0C] | 47 - 86 [0C] |

| Vehicle 2(Gasoline) | 10 - 44 [0C] | 44 - 81 [0C] |

| Vehicle 3 (Diesel) | 12 - 37 [0C] | 37 - 69 [0C] |

| Vehicle 4 (Diesel) | 10 - 35 [0C] | 35 - 71 [0C] |

| Vehicle Test | Vehicle 1 | Vehicle 2 | Vehicle 3 | Vehicle 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test fuel consumption | M-BV Cycle | [l/100km] | 16.02 | 19.16 | 13.28 | 13.98 |

| E-BV Cycle | [l/100km] | 14.37 | 11.44 | 16.15 | 15.66 | |

| Manufacturer’s fuel consumption data | Urban travel | [l/100km] | 5.30 | 8.80 | 4.30 | 4.10 |

| Extra urban travel | [l/100km] | 4.00 | 5.60 | 3.30 | 3.80 | |

| Mixed travel | [l/100km] | 4.50 | 6.70 | 3.40 | 3.70 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).