Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

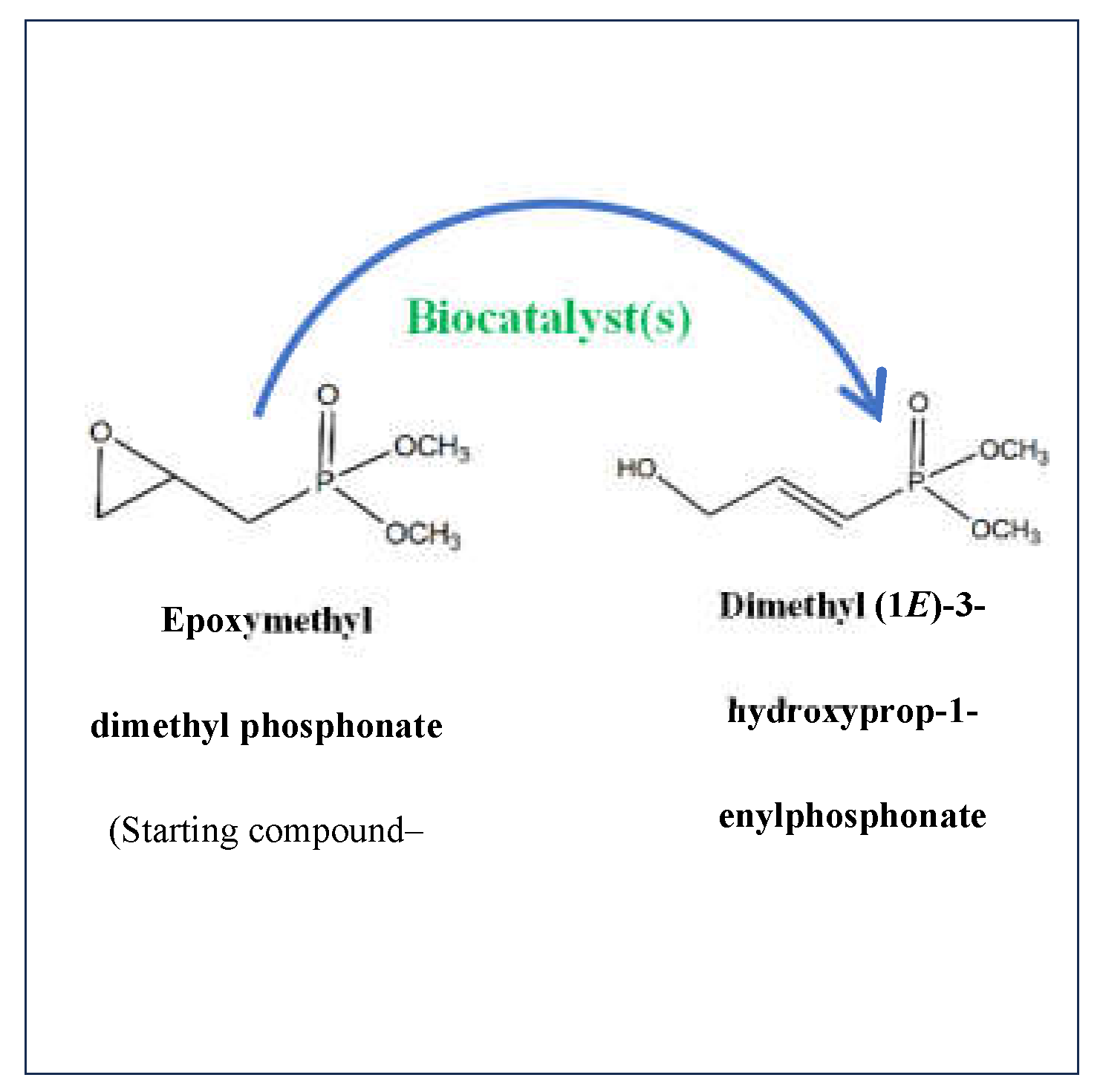

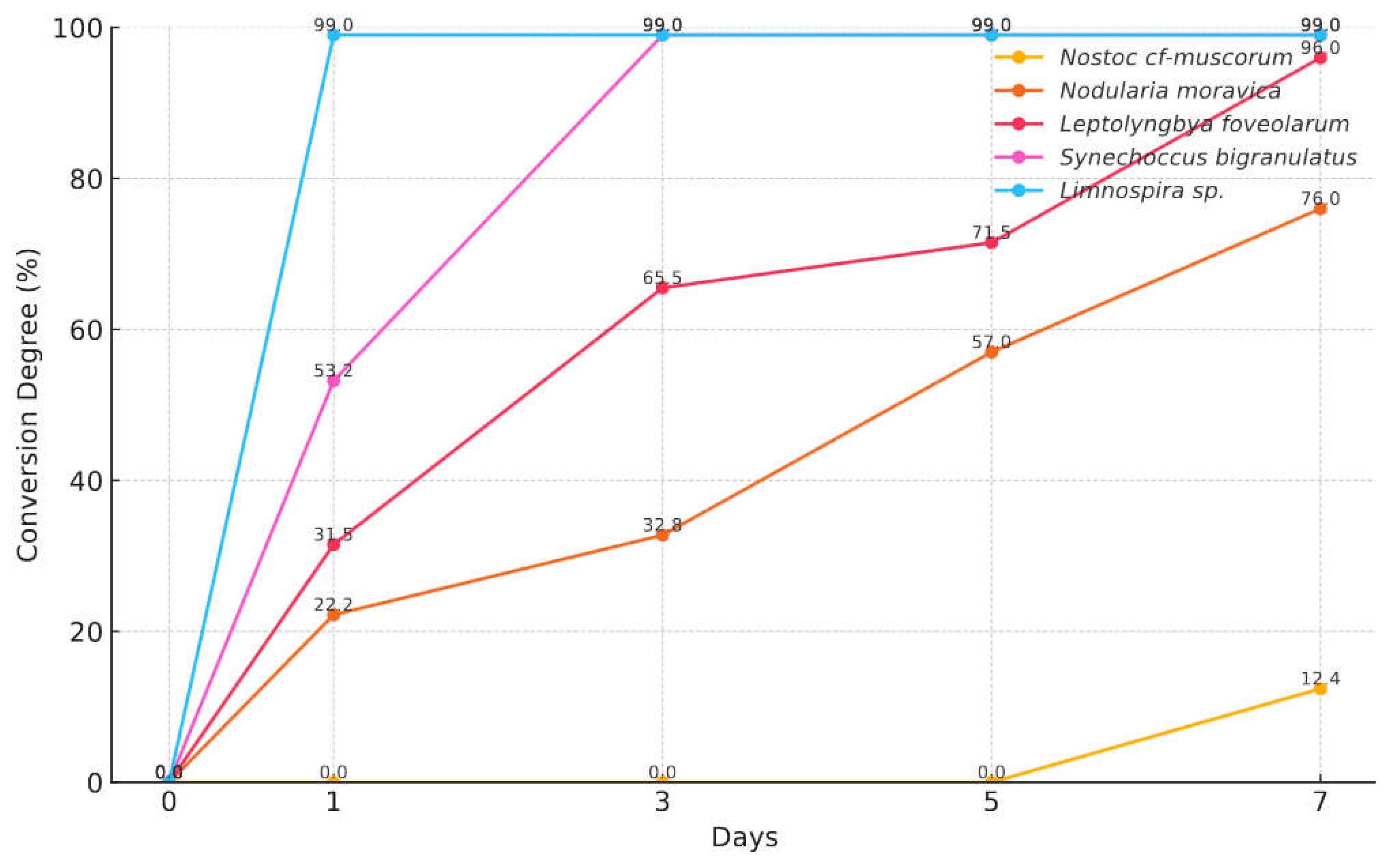

3.1. Comparative Bioconversion Rates of Cyanobacterial Strains

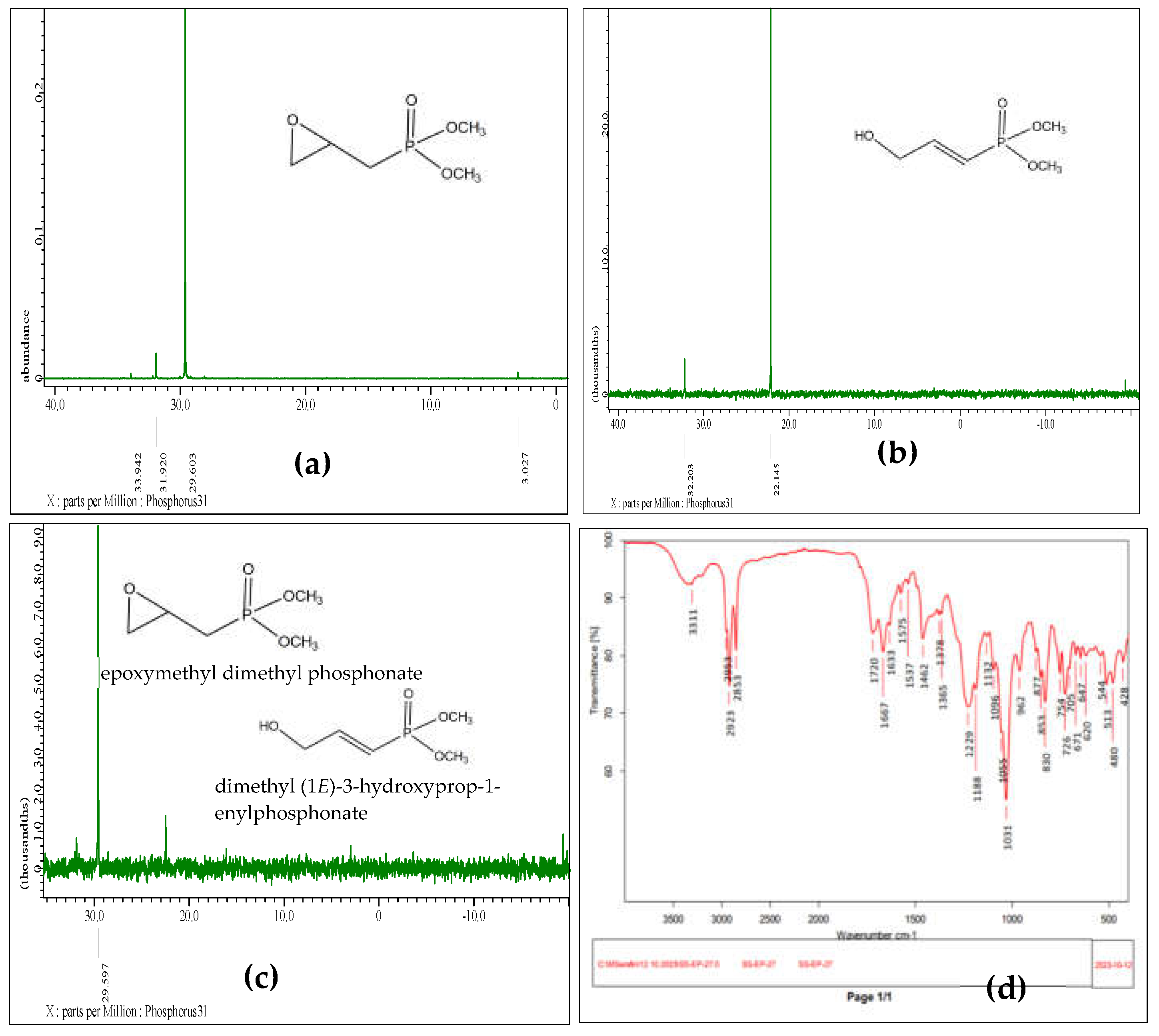

3.2. Spectral Characterization of Biotransformation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McPherson, J.C.; Runner, R.; Buxton, T.B.; Hartmann, J.F.; Farcasiu, D.; Bereczki, I.; Rőth, E.; Tollas, S.; Ostorházi, E.; Rozgonyi, F.; et al. Synthesis of osteotropic hydroxybisphosphonate derivatives of fluoroquinolone antibacterials. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 47, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikołajczyk M (2019) Phosphonate reagents and building blocks in the synthesis of bioactive compounds, natural products and medicines. Pure Appl Chem 91:811–838. [CrossRef]

- Krečmerová M, Majer P, Rais R, Slusher BS (2022) Phosphonates and Phosphonate Prodrugs in Medicinal Chemistry: Past Successes and Future Prospects. Front Chem 10:889737. [CrossRef]

- Sevrain, C.M.; Berchel, M.; Couthon, H.; Jaffrès, P.-A. Phosphonic acid: preparation and applications. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 2186–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaboudin B, Daliri P, Faghih S, Esfandiari H (2022) Hydroxy- and Amino-Phosphonates and -Bisphosphonates: Synthetic Methods and Their Biological Applications. Front Chem 10:890696. [CrossRef]

- Alkenoic acids and their derivatives. In: Tetrahedron Organic Chemistry Series. pp 199–282.

- Turhanen PA, Demadis KD, Kafarski P (2021) Editorial: Phosphonate Chemistry in Drug Design and Development. Front Chem 9:695128. [CrossRef]

- Manghi, M.C.; Masiol, M.; Calzavara, R.; Graziano, P.L.; Peruzzi, E.; Pavoni, B. The use of phosphonates in agriculture. Chemical, biological properties and legislative issues. 2021, 283, 131187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, C.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Z.; Shu, C. Recent developments in the synthesis of pharmacological alkyl phosphonates. Adv. Agrochem 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Singh, P. Epoxides: Developability as active pharmaceutical ingredients and biochemical probes. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 125, 105862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montchamp JL (2019) Challenges and solutions in phosphinate chemistry. Pure Appl Chem 91:113–120. [CrossRef]

- Cybulska P, Legrand YM, Babst-Kostecka A, Diliberto S, Leśniewicz A, Oliviero E, Bert V, Boulanger C, Grison C, Olszewski TK (2022) Green and Effective Preparation of α-Hydroxyphosphonates by Ecocatalysis. Molecules 27:3075. [CrossRef]

- Serafin-Lewańczuk M, Brzezińska-Rodak M, Lubiak-Kozłowska K, Majewska P, Klimek-Ochab M, Olszewski TK, Żymańczyk-Duda E (2021) Phosphonates enantiomers receiving with fungal enzymatic systems. Microb. Cell Fact. 20.

- Kolodiazhna, A.O.; Kolodiazhnyi, O.I. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of C-Chiral Phosphonates. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobkowski M, Kraszewski A, Stawinski J (2014) Recent Advances in H-Phosphonate Chemistry. Part 2. Synthesis of C-Phosphonate Derivatives. Top Curr Chem 361:179–216. [CrossRef]

- Schrewe, M.; Julsing, M.K.; Bühler, B.; Schmid, A. Whole-cell biocatalysis for selective and productive C–O functional group introduction and modification. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6346–6377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, N.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Z.; Tao, J. Recent applications of biocatalysis in developing green chemistry for chemical synthesis at the industrial scale. Green Chem. 2007, 10, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groaz E, De Jonghe S (2021) Overview of Biologically Active Nucleoside Phosphonates. Front Chem 8:616863. [CrossRef]

- Hilderbrand, R.L. Henderson TO (2018) Phosphonic acids in nature. Role Phosphonates Living Syst 5–30. [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.E.; Kaplan, A.P.; Bartlett, P.A. Phosphonate analogs of carboxypeptidase A substrates are potent transition-state analog inhibitors. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 6294–6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffolo, F.; Dinhof, T.; Murray, L.; Zangelmi, E.; Chin, J.P.; Pallitsch, K.; Peracchi, A. The Microbial Degradation of Natural and Anthropogenic Phosphonates. Molecules 2023, 28, 6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsági, N.; Keglevich, G. The Hydrolysis of Phosphinates and Phosphonates: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsman, G.P.; Zechel, D.L. Phosphonate Biochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2016, 117, 5704–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górak, M.; Żymańczyk-Duda, E. Application of cyanobacteria for chiral phosphonate synthesis. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 4570–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüllinghoff, A.; Djaya-Mbissam, H.; Toepel, J.; Bühler, B. Light-driven redox biocatalysis on gram-scale in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 via an in vivo cascade. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 2074–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk, A.; Selão, T.T.; Norling, B.; Nixon, P.J. Newly discovered Synechococcus sp. PCC 11901 is a robust cyanobacterial strain for high biomass production. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu S, Boussiba S (2014) Advances in the Production of High-Value Products by Microalgae. Ind. Biotechnol. 1: 10.

- Vijay, D.; Akhtar, M.K.; Hess, W.R. (2019) Genetic and metabolic advances in the engineering of cyanobacteria. Curr Opin Biotechnol 59:150–156. [CrossRef]

- El-Fayoumy, E.A.; Shanab, S.M.; Hassan, O.M.A.; Shalaby, E.A. Enhancement of active ingredients and biological activities of Nostoc linckia biomass cultivated under modified BG-110 medium composition. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 13, 6049–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, E.; López-Lozano, A.; Herrero, A. (2015) Nitrogen fixation in the oxygenic phototrophic prokaryotes (cyanobacteria): the fight against oxygen. Biol Nitrogen Fixat 2–2:879–890. [CrossRef]

- Kulasooriya SA, Magana-Arachchi DN (2016) Nitrogen fixing cyanobacteria: Their diversity, ecology and utilization with special reference to rice cultivation. J Natl Sci Found Sri Lanka 44:111–128. [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Rodríguez YY, Herazo-Cárdenas DS, Vallejo-Isaza A, Pompelli MF, Jarma-Orozco A, Jaraba-Navas J de D, Cordero-Ocampo JD, González-Berrio M, Arrieta DV, Pico-González A, Ariza-González A, Aviña-Padilla K, Rodríguez-Páez LA (2023) Optimal Laboratory Cultivation Conditions of Limnospira maxima for Large-Scale Production. Biology (Basel) 12:1462. [CrossRef]

- Segers C, Mysara M, Coolkens A, Wouters S, Baatout S, Leys N, Lebeer S, Verslegers M, Mastroleo F (2023) Limnospira indica PCC 8005 Supplementation Prevents Pelvic Irradiation-Induced Dysbiosis but Not Acute Inflammation in Mice. Antioxidants 12:. [CrossRef]

- Poughon L, Laroche C, Creuly C, Dussap C-G, Paille C, Lasseur C, Monsieurs P, Heylen W, Coninx I, Mastroleo F (2020) limnospira indica pcc8005 growth in photobioreactor: model and simulation of the iss and ground experiments. Life Sci Sp Res 25. [CrossRef]

- López-Rodríguez A, Mayorga J, Flaig D, Fuentes G, Hernández V, Gómez PI (2023) Genetic characterization and assessment of the biotechnological potential of strains belonging to the genus Arthrospira/Limnospira (Cyanophyceae) deposited in different culture collections. Algal Res 73:103164. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; El-Sheekh, M.; Manni, A.; Ruiz, H.A.; Elsamahy, T.; Sun, J.; Schagerl, M. Microalgae-mediated wastewater treatment for biofuels production: A comprehensive review. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 265, 127187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshari N, Zhao Y, Das SK, Zhu T, Lu X (2022) Cyanobacterial Community Structure and Isolates From Representative Hot Springs of Yunnan Province, China Using an Integrative Approach. Front Microbiol 13:. [CrossRef]

- Negi, R.; Nigam, M.; Singh, R.K. Harnessing Leptolyngbya for antiproliferative and antimicrobial metabolites through lens of modern techniques: A review. Algal Res. 2024, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.R.; Narendrakumar, G.; Thyagarajan, R.; Melchias, G. A comparative analysis of biodiesel production and its properties from Leptolyngbya sp. BI-107 and Chlorella vulgaris under heat shock stress. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Morita, M.; Ohno, O.; Kimura, T.; Teruya, T.; Watanabe, T.; Suenaga, K.; Shibasaki, M. Leptolyngbyolides, Cytotoxic Macrolides from the Marine Cyanobacterium Leptolyngbya sp.: Isolation, Biological Activity, and Catalytic Asymmetric Total Synthesis. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 8500–8509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żymańczyk-Duda, E.; Głąb, A.; Górak, M.; Klimek-Ochab, M.; Brzezińska-Rodak, M.; Strub, D.; Śliżewska, A. Reductive capabilities of different cyanobacterial strains towards acetophenone as a model substrate – Prospect of applications for chiral building blocks synthesis. Bioorganic Chem. 2019, 93, 102810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodlbauer, J.; Rohr, T.; Spadiut, O.; Mihovilovic, M.D.; Rudroff, F. Biocatalysis in Green and Blue: Cyanobacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Sun, H.; Chen, R.; Sun, J.; Mo, G.; Luan, G.; Lu, X. Multiple routes toward engineering efficient cyanobacterial photosynthetic biomanufacturing technologies. Green Carbon 2023, 1, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baunach, M.; Guljamow, A.; Miguel-Gordo, M.; Dittmann, E. Harnessing the potential: advances in cyanobacterial natural product research and biotechnology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 41, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, R.; Saxena, A.K.; Jaiswal, P.; Nayak, S. Development of alternative support system for viable count of cyanobacteria by most probable number method. Folia Microbiol. 2006, 51, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parte, S.; Sirisha, V.L.; D’Souza, J.S. Biotechnological Applications of Marine Enzymes From Algae, Bacteria, Fungi, and Sponges. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 80, pp. 75–106. [Google Scholar]

- Knoop, H.; Gründel, M.; Zilliges, Y.; Lehmann, R.; Hoffmann, S.; Lockau, W.; Steuer, R. Flux Balance Analysis of Cyanobacterial Metabolism: The Metabolic Network of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9, e1003081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Lin LZ, Zeng Y, Teng WK, Chen MY, Brand JJ, Zheng LL, Gan NQ, Gong YH, Li XY, Lv J, Chen T, Han BP, Song LR, Shu WS (2023) The facilitating role of phycospheric heterotrophic bacteria in cyanobacterial phosphonate availability and Microcystis bloom maintenance. Microbiome 11:1–16. [CrossRef]

- González-Morales SI, Pacheco-Gutiérrez NB, Ramírez-Rodríguez CA, Brito-Bello AA, Estrella-Hernández P, Herrera-Estrella L, López-Arredondo DL (2020) Metabolic engineering of phosphite metabolism in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 as an effective measure to control biological contaminants in outdoor raceway ponds. Biotechnol Biofuels 13:1–19. [CrossRef]

- Dexter, J.; Fu, P. Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria for ethanol production. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattharaprachayakul, N.; Choi, J.-I.; Incharoensakdi, A.; Woo, H.M. Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology of Cyanobacteria for Carbon Capture and Utilization. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2020, 25, 829–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.A.; Al-Haj, L.; Abed, R.M.M. Metabolic engineering of Cyanobacteria and microalgae for enhanced production of biofuels and high-value products. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati R, Mallick N (2012) Production and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) co-polymer by a N 2-fixing cyanobacterium, Nostoc muscorum Agardh. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 87:505–512. [CrossRef]

- Dodds WK, Gudder DA, Mollenhauer D (1995) THE ECOLOGY OF NOSTOC. J Phycol 31:2–18. [CrossRef]

- Nostoc muscorum - microbewiki. https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Nostoc_muscorum. 2024.

- Wang, Y.; Tao, F.; Ni, J.; Li, C.; Xu, P. Production of C3 platform chemicals from CO2 by genetically engineered cyanobacteria. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 3100–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pembroke JT, Ryan MP (2020) Cyanobacterial Biofuel Production: Current Development, Challenges and Future Needs. 35–62. [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Li, C.; Zheng, H.; Ni, J. Engineering cyanobacteria for the production of aromatic natural products. Blue Biotechnol. 2024, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, A.; Esquirol, L.; Ebert, B.E. Current Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Photosynthetic Bioproduction in Cyanobacteria. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.C.; Lan, E.I. Advances in Metabolic Engineering of Cyanobacteria for Photosynthetic Biochemical Production. Metabolites 2015, 5, 636–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, S.; Abdollahi, K.; Panahi, R.; Rahmanian, N.; Shakeri, M.; Mokhtarani, B. Applications of Biocatalysts for Sustainable Oxidation of Phenolic Pollutants: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippka, R.; Deruelles, J.; Waterbury, J.B.; Herdman, M.; Stanier, R.Y. Generic Assignments, Strain Histories and Properties of Pure Cultures of Cyanobacteria. Microbiology 1979, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just G, Potvin P, Hakimelahi GH 3-Diethylphosphonoacrolein diethylthioacetal anion (6*), a reagent for the conversion of aldehydes to u,p-unsaturated ketene dithioacetals and three-carbon homologated u ,p-unsaturated aldehydes.

- Galezowska, J.; Gumienna-Kontecka, E. Phosphonates, their complexes and bio-applications: A spectrum of surprising diversity. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornburg, C.C.; Cowley, E.S.; Sikorska, J.; Shaala, L.A.; Ishmael, J.E.; Youssef, D.T.A.; McPhail, K.L. Apratoxin H and Apratoxin A Sulfoxide from the Red Sea Cyanobacterium Moorea producens. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H:\chm_51\website\chapters\carey-13.PDF | Enhanced Reader.

- Sengupta S, Jaiswal D, Sengupta A, Shah S, Gadagkar S, Wangikar PP (2020) Metabolic engineering of a fast-growing cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 11801 for photoautotrophic production of succinic acid. Biotechnol Biofuels 13:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, J.; Feng, D.; Sun, H.; Cui, J.; Zeng, X.; Wu, Y.; Luan, G.; Lu, X. Unlocking the potentials of cyanobacterial photosynthesis for directly converting carbon dioxide into glucose. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciebiada, M.; Kubiak, K.; Daroch, M. Modifying the Cyanobacterial Metabolism as a Key to Efficient Biopolymer Production in Photosynthetic Microorganisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouga T, Pereira J, Moreira V, Afonso C (2024) Unveiling the Cultivation of Nostoc sp. under Controlled Laboratory Conditions. Biology (Basel) 13:306. [CrossRef]

- Brenes-Álvarez, M.; Olmedo-Verd, E.; Vioque, A.; Muro-Pastor, A.M. A nitrogen stress-inducible small RNA regulates CO2 fixation in Nostoc. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciani M, Adessi A (2023) Cyanoremediation and phyconanotechnology: cyanobacteria for metal biosorption toward a circular economy. Front Microbiol 14:1166612. [CrossRef]

- Cepoi, L.; Zinicovscaia, I.; Valuta, A.; Codreanu, L.; Rudi, L.; Chiriac, T.; Yushin, N.; Grozdov, D.; Peshkova, A. Bioremediation Capacity of Edaphic Cyanobacteria Nostoc linckia for Chromium in Association with Other Heavy-Metals-Contaminated Soils. Environments 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourembam J, Haobam B, Singh KB, Verma S, Rajan JP (2024) The molecular insights of cyanobacterial bioremediations of heavy metals: the current and the future challenges. Front Microbiol 15:1450992. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Shao, L.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, X. Microfluidic immobilized enzyme reactors for continuous biocatalysis. React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 5, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Miyazaki, M. Bioremediation of Hazardous Pollutants Using Enzyme-Immobilized Reactors. Molecules 2024, 29, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A.; Basso, A.; Brady, D. New frontiers in enzyme immobilisation: robust biocatalysts for a circular bio-based economy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 5850–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).