Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

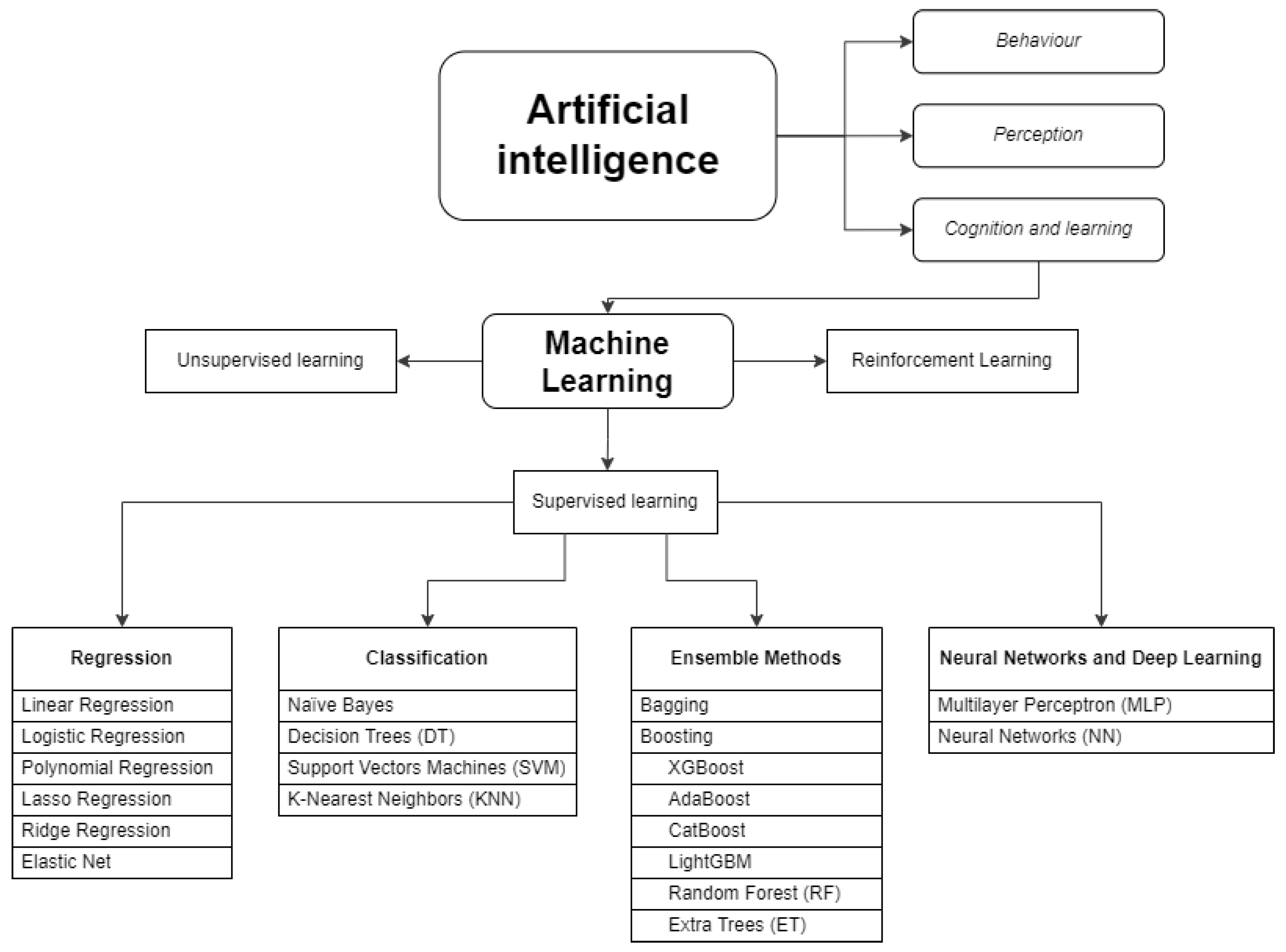

2.1. AI and ML Techniques Used for PK Modelling and Dose Prediction

2.2. Evaluation of the Available Data

| Metric | Type of statistical metric | Type of evaluation | Definition | Formula | Units | Interpretation |

| Coefficient of determination (R-squared) R² |

regression metric | accuracy or bias | proportion of the total variance of the variable explained by the regression | no units | Represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable which is explained by the linear regression model. Values between 0 to 1, where 1 is the best value. |

|

| Prediction error (PE) | difference | accuracy or bias | difference between the predicted and observed concentrations | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower PE indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Prediction error percentage (PE%) | percentage metric |

accuracy or bias | percentage of PE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower PE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Absolute prediction error (AE) | difference | accuracy or bias | difference between the predicted and observatory concentrations in absolute values. |

|

concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower APE indicates superior model accuracy |

| Absolute prediction error percentage (APE or AE%) | percentage metric | accuracy or bias | percentage of APE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower APE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean prediction error (ME) | media of the difference | accuracy or bias | sum of prediction errors divided by the sample size. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MPE indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean prediction error percentage (MPE or ME%) | percentage metric | accuracy or bias | percentage of MPE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MPE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean absolute prediction error (MAE) | media of the difference | precision | sum of absolute errors divided by the sample size. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MAE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Mean absolute prediction error percentage (MAPE or MAE%) | percentage metric | precision | percentage of MAPE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MAPE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Root mean squared error (RMSE) | squared root | precision | It quantifies the differences between predicted values and actual values, squaring the errors, taking the mean, and then finding the square root. It is computed by taking the square root of MSE. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ Lower values indicating better predictive accuracy. |

|

| Root mean squared error percentage (RMSE%) | squared root relative | precision | percentage of the RMSE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower RMSE% indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Median prediction error percentage (MDPE%) | median | precision | MDPE is found by ordering PE from smallest to largest, and using this middle value |

% | Values between 0 to 100- A lower MDPE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Median absolute prediction error percentage (MDAPE%) | median | precision | MDAPE is found by ordering the APE from smallest to largest and using this middle value. |

concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MDAPE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Mean relative error (MRE) | relative ratio | accuracy or bias | MRE was defined as the ratio between MAPE and the reference E-field magnitude within the corresponding target region. | no units |

Values between 0 to 1 |

|

| Mean relative error percentage (MRE% or rMPE) | relative percentage | accuracy or bias | percentage of MRE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MRE% indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Square prediction error (SPE) | square of the difference | precision | measures the expected squared distance between what your predictor predicts for a specific value and what the true value | square concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower SPE indicates a better model. |

|

| Mean square error (MSE) | mean of the difference | precision | squaring the difference between the predicted value and actual value and averaging it across the dataset. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ MSE increases exponentially with an increase in error. A good model will have an MSE value closer to zero. |

|

| relative mean prediction error (RMPE or rMPE) |

relative percentage | accuracy or bias | is a variant of Root MPE, gauging predictive model accuracy relative to the target variable range. | % | Value between 0 to 100. Lower rMPE shows lower deviation. |

|

| relative root mean squared error (RRMSE or rRMSE) |

relative percentage | accuracy or bias | is a variant of RMSE, gauging predictive model accuracy relative to the target variable range. | % | Value between 0 to 100. < 10% is an excellent value for RRMSE. > 30 %is a poor value for RRMSE. |

| Metric | Type of statistical metric | Type of evaluation | Definition | Formula | Units | Interpretation |

| Coefficient of determination (R-squared) R² |

regression metric | accuracy or bias | proportion of the total variance of the variable explained by the regression | no units | Represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable which is explained by the linear regression model. Values between 0 to 1, where 1 is the best value. |

|

| Prediction error (PE) | difference | accuracy or bias | difference between the predicted and observed concentrations | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower PE indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Prediction error percentage (PE%) | percentage metric |

accuracy or bias | percentage of PE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower PE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Absolute prediction error (AE) | difference | accuracy or bias | difference between the predicted and observatory concentrations in absolute values. |

|

concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower APE indicates superior model accuracy |

| Absolute prediction error percentage (APE or AE%) | percentage metric | accuracy or bias | percentage of APE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower APE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean prediction error (ME) | media of the difference | accuracy or bias | sum of prediction errors divided by the sample size. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MPE indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean prediction error percentage (MPE or ME%) | percentage metric | accuracy or bias | percentage of MPE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MPE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean absolute prediction error (MAE) | media of the difference | precision | sum of absolute errors divided by the sample size. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MAE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Mean absolute prediction error percentage (MAPE or MAE%) | percentage metric | precision | percentage of MAPE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MAPE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Root mean squared error (RMSE) | squared root | precision | It quantifies the differences between predicted values and actual values, squaring the errors, taking the mean, and then finding the square root. It is computed by taking the square root of MSE. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ Lower values indicating better predictive accuracy. |

|

| Root mean squared error percentage (RMSE%) | squared root relative | precision | percentage of the RMSE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower RMSE% indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Median prediction error percentage (MDPE%) | median | precision | MDPE is found by ordering PE from smallest to largest, and using this middle value |

% | Values between 0 to 100- A lower MDPE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Median absolute prediction error percentage (MDAPE%) | median | precision | MDAPE is found by ordering the APE from smallest to largest and using this middle value. |

concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MDAPE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Mean relative error (MRE) | relative ratio | accuracy or bias | MRE was defined as the ratio between MAPE and the reference E-field magnitude within the corresponding target region. | no units |

Values between 0 to 1 |

|

| Mean relative error percentage (MRE% or rMPE) | relative percentage | accuracy or bias | percentage of MRE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MRE% indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Square prediction error (SPE) | square of the difference | precision | measures the expected squared distance between what your predictor predicts for a specific value and what the true value | square concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower SPE indicates a better model. |

|

| Mean square error (MSE) | mean of the difference | precision | squaring the difference between the predicted value and actual value and averaging it across the dataset. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ MSE increases exponentially with an increase in error. A good model will have an MSE value closer to zero. |

|

| relative mean prediction error (RMPE or rMPE) |

relative percentage | accuracy or bias | is a variant of Root MPE, gauging predictive model accuracy relative to the target variable range. | % | Value between 0 to 100. Lower rMPE shows lower deviation. |

|

| relative root mean squared error (RRMSE or rRMSE) |

relative percentage | accuracy or bias | is a variant of RMSE, gauging predictive model accuracy relative to the target variable range. | % | Value between 0 to 100. < 10% is an excellent value for RRMSE. > 30 %is a poor value for RRMSE. |

| Study | ATB | N |

Subject characteristics |

Objective |

AI technique used |

Clinical parameters involved | Model compared | Precision metrics* | Results | Remarks and conclusions |

| Keutzer et al., 2022 [23] | Rifampicin | 1826 simulations | Tuberculosis patients | To examine the ability of various ML algorithms to predict time-varying plasma concentrations and derive PK parameters | XGBoost, RF, GBM, LASSO | Age, BMI, dose, fat-free-mass, infection by VIH, VIH coinfection, height, treatment week, race, gender, time after dose, weight. | popPK model in NONMEM | R2, RMSE, MAE | -For concentration prediction, the best AI technique was XGBoost using 6 rifampicin concentrations (R2=0,84, RMSE=6,9 mg/L, MAE= 4 mg/L. -For AUC0-24h prediction, the best AI technique was LASSO using 6 rifampicin concentrations (R2=0,97, RMSE: 29.1 h.mg/L, MAE: 18.8 h.mg/L) |

Prediction was according to the PK model. AI was 22 times faster. |

| Wang et al., 2022 [38] | Vancomycin | 2282 real patients | Patients who received at least one vancomycin injection. | To develop an innovative method to suggest the initial and subsequent daily dose of vancomycin. | LightGBM | s-Cr, CrCl, age, weight, gender, age, albumin, medicines on CV system, on alimentary tract or metabolism and on blood forming organs, hemodialysis, daily dose and concentration, administration timing. | popPK model | MAE, PAR** | -Initial dose model: MAE: 450.2 mg/day (AI model) vs 727.5 mg/day (popPK model); PAR: 51,7% (AI model) vs 28,3% (popPK model) -Subsequent dose model: MAE: 267,1 mg/day (AI model) vs 392,1 mg/day (popPK model); PAR: 73,4% (AI model) vs 60,4% (popPK model) |

ML performed better than the popPK model. |

| Bouoda et al., 2022 [36] | Vancomycin | 28 real patients/ 6000 simulations | Obese, critically ill, hospitalized patients with sepsis, trauma and post- heart surgery. | To train a ML algorithm to predict vancomycin AUC from early concentrations and few features and Predict vancomycin AUC from early concentrations | XGBoost | Concentration, s-Cr, age, weight, height, gender, dose, administration timing. | popPK models: MAA, MSA, PKJust program |

rMPE, rRMSE | rMPE 0,97 and rRMSE 12.7% ; when compared with PKJust; rMPE 0,8 and rRMSE 11,9% when compared with MSA; rMPE 1,2 and rRMPE 11,8% with MAA. | XGBoost algorithms seem complementary to standard popPK approaches. |

| Ponthier et al., 2022 [37] | Vancomycin |

82 real patients / 1900 simulations | Term and preterm neonates | To obtain a ML algorithm to estimate the best vancomycin initial dose and compare it to a popPK model previously validated. | XGBoost, GLMNET, MARS | Gestational age, time of infection after birth, post menstrual age at first infection, current weight, s-Cr. | popPK model | rMPE, rRMSE | XGBoost was the best. In the training set, rRMSE was 36.1 and rMPE was 7.2 in the train set. In the test set, rRMSE was 35,7 and rMPE was 8,6. Numerical best target attainment rate was obtained with ML algorithm (35,3% vs 28%). |

ML algorithm improves the exposure target attainment rate. |

| Tang et al., 2021 [47] | Vancomycin, latamofex, cefepime, azlocillin, ceftazidime and amoxicillin | 2272 real patients | Neonates | To evaluate whether the combination of ML methods and popPK methods can accurately predict individual clearance of renally eliminated drugs. | KNN, DT, adaboost, ETR, RF, GBR | Birth weight, current weight, gestational age, postnatal age, postmenstrual age, s-Cr. | popPK model in NONMEM | R2, MSE, MRE% | ETR was selected as the final uniform ML approach. Combined predictive method (popPK + AI) had a MRE of 15,4%, 2,2%, 2,8%, 10,1% and 2% for vancomycin, cefepime, latamoxef, azlocillin amoxicillin and ceftazidime, respectively. Except for azlocillin (9,9% of MRE in the popPK model), all the MRE were lower with the combined method. |

The combination of popPK and machine learning approach provided consistent information. |

| Brier et al., 1995 [43] | Gentamicin | 144 real patients | Patients who received gentamicin in the service of the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Louisville | To use a neural network to predict peak and trough gentamicin concentrations and compare the results with the NONMEM model. | NN | Age, height, weight, s-Cr, CrCl, dose, dose/weight, dose interval, BMI. | popPK model in NONMEM | PE, PE%, SPE, AE, APE (or AE%) | -Gentamicin´s peak: PE was - 0,02 in NN vs 0,14 in NONMEN, PE% was - 2,45% in NN vs 1.04% in NONMEN, SPE was 0,67 in NN vs 0,83 in NONMEN, and APE was 16,5% in NN vs 18,6% in NONMEN. -Gentamicin´s trough: PE was 0.002 in NN vs 0.049 in NONMEN, PE% was - 11,11% in NN vs -14.5% in NONMEN, SPE was 0.58 in NN vs 0.67 in NONMEN, and APE was 48.3% in NN vs 59% in NONMEN. NONMEM was more precise in the prediction of concentration outside the range 2,5-6 µg/ml (p=0,098) |

NN perform well when they are used in the range of concentrations that they have trained. NN has limitations in predicting out-of-range concentrations. |

| Verhaeghe et al., 2022 [46] | Piperacillin | 282 real patients | Surgical critically ill patients treated with piperacillin/tazobactam in continuous infusion. | To use ML model to predict total plasma concentrations of piperacillin in critically ill patients a priori and a posteriori and compare the results with a popPK model. | GBT, GP, MLP | Piperacillin previous concentrations, sex, weight, s-Cr, CrCl, albumin, bilirubin, fluid balance, height, lactate, platelets, red blood cells, sex, hours since start of treatment. | popPK model in NONMEM | PE, MAE, RMSE, R2, MdAPE, MdPE. | -A priori method: RMSE (GBT 34,27; GP 37,41; MLP 38,56; PK 57,97), MAE (GBT 21,55; GP 23,54; MLP 27,35; PK 39,67), ME (GBT -4.09; GP 2.04; MLP 2.58; PL -30.27), MdAPE (GBT 17.29%; GP 21.39%; MLP 23.09%; PL 40.79%), MdPE (GBT 0.06%; GP -3.83%; MLP -5.34%; PK 38.33%) -A posteriori method: RMSE (GBT 32.93; GP 34.03; MLP 37.20; PK 49.58), MAE (GBT 18.22; GP 19.41; MLP 23.64; PK 31.28), ME (GBT -6.55; GP -3.83; MLP -4.87; PK 4.91), MdAPE (GBT 12.75%; GP 16.48%; MLP 17.06%; PK 26.09%), MdPE (GBT 1.77%; GP -376%; MLP 0.73%; PK -1.85%) |

ML models can consistently estimate piperacillin concentrations with high predictive accuracy, especially in a priori method. |

| Huang et al., 2021 [42] | Vancomycin | 407 real patients | Pediatric patients who received vancomycin intravenously | To establish an optimal model to predict vancomycin through concentrations in pediatric patients by using ML. | DT, SVR, RF, Adaboost, Bagging, ETR, GBRT, XGBoost. Then, the best five were selected and perform an "ensemble model" | vancomycin dose concentrations and intervals, age, height, weight, gender, CrCl, uric acid, procalcitonin, PCR, AST, ALT, bilirubin, complete hemogram. | popPK model in NONMEM | R2, MSE, RMSE, MAE | The results of ML were superior to the popPK model. Ensemble model: MSE 34,39, R2 0,614, MAE 3,32, RMSE 4,94. Accuracy of the predicted through concentration (± 30%) was 51,22% in ML model vs 36.59% in popPK model. | The results of ML are better than the popPK model in predicting vancomycin concentration. |

| Yamamura et al., 2004 [44] | Arbekacin (Aminoglycoside used in Japan) |

30 real patients | Burn patients hospitalized in an intensive care unit in Japan. | Use artificial neural network modeling to predict arbekacin plasma concentration and compare with logistic regression analysis. | NN | Dose, parenteral fluid, BMI, CrCl, burn area after operation. | Multivariate logistic regression models | R2 | Artificial neural networks had a r of 0,9862 and logistic regression had a r of 0,8829. | Artificial neural networks were superior compared with logistic regression analysis. |

| Tang et al., 2023 [41] | Vancomycin | 1631 real patients | Neonates and young infants with postmenstrual age ranging from 23.3 to 52.4 weeks | To assess whether ML can be used in clinical practice to predict treatment targets and calculate optimal dosing regimens for individual patients. | GBDT, CatBoost, XGBoost, LBHM, LR, SVR, Tabnet, and ANN | s-Cr, sampling time, single dose per unit body weight, frequency of dosing within 24h, postnatal age, vancomycin concentration assay method, gestational age at birth, birth weight. | popPK model | RMSE, R2, MAPE (or MAE%), MPE (or ME%) | CatBoost was the optimal ML method. For Cmin prediction, RMSE was 5.02 for ML model vs 6.18 for popPK; MAPE was 29.5% for ML model vs 53% for popPK and MPE was -4.20% for ML vs 12.4 for popPK. |

The ML model was developed to be accurate and precise and can be used for individual dose recommendations in neonates. |

| Chow et al., 1997 [45] | Tobramycin | 101 real patients | Pediatric patients who received tobramycin intravenously in Tucson. | To explore the applicability of the neural networks approach to capture the relationship between patient-related prognostic factors and plasma drug levels. | NN: test I (with accumulated times), test II (without accumulated times) | Age, weight, gender, illness, dose, dosing interval, time of blood drawn. | popPK model in NONMEM | MSE, ME, ME% (or MPE), AE% (or APE) | Test I turned out worse than NONMEN. Test II provided precision of the predicted concentrations comparable to that NONMEN analysis: MSE 1,88 NONMEN vs 1,78 NN. AE% was better for NN test II: 33,9% vs 39,9% in NONMEN. ME was smaller in NONMEN (0,077 vs 0,32), PE% was better in NN (2,59% vs 17,3% in NONMEN) | NN could capture the relationships between patient-related factors and plasma drugs levels. |

| Nigo et al., 2022 [39] | Vancomycin | 5483 real patients | Adults who had at least one serum vancomycin level after their first vancomycin dose. Patients with ECMO, hemodialysis, and renal replacement therapy were excluded. | To develop a new PK approach with RNN-based methods with electronic medical record (EHR) to achieve more accurate and individualized predictions for vancomycin serum concentration in hospitalized patients. | NN | Weight, height, vital signs, laboratory biochemistry and complete hemogram, vancomycin dose and previous concentration, concomitant medications. | popPK model in NONMEM (VTDM model) |

RMSE, MAPE (or MAE%), MAE | PK-RNN-V E vs VTDM: RMSE 5,39 vs 6,29; MAE 3,64 vs 4,26; MAPE 25,41% vs 29,15%. | PK-RNN-V E exhibits better RMSE, MAE and MAPE compared to any of the VTDM models. PK-RNN-V E can integrate real-time patient-specific data from an EHR. |

| Miyai et al., 2022 [40] | Vancomycin | 822 real patients | Patients who received vancomycin intravenously and had the concentration measured at least once. | To construct a model for estimating the vancomycin maintenance dose to achieve the target. | CART | Age, BMI, CrCl. | Other nomograms (Oda et al.[53], Thomson et al. [54]) | ME% (or MPE), MAE% (or MAPE) | DT model: ME 10%, MAE 26,7%; Nomogram Oda et al.: ME 0,77%, MAE 26,6%; Nomogram Thomson et al: ME 8,67%, MAE 26,5%. | The constructed model can help construct clinical models for dose setting of initial vancomycin administration. |

2.3. Quality Assessment on Prediction Accuracy of Techniques Employed

| Metric | Type of statistical metric | Type of evaluation | Definition | Formula | Units | Interpretation |

| Coefficient of determination (R-squared) R² |

regression metric | accuracy or bias | proportion of the total variance of the variable explained by the regression | no units | Represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable which is explained by the linear regression model. Values between 0 to 1, where 1 is the best value. |

|

| Prediction error (PE) | difference | accuracy or bias | difference between the predicted and observed concentrations | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower PE indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Prediction error percentage (PE%) | percentage metric |

accuracy or bias | percentage of PE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower PE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Absolute prediction error (AE) | difference | accuracy or bias | difference between the predicted and observatory concentrations in absolute values. |

|

concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower APE indicates superior model accuracy |

| Absolute prediction error percentage (APE or AE%) | percentage metric | accuracy or bias | percentage of APE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower APE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean prediction error (ME) | media of the difference | accuracy or bias | sum of prediction errors divided by the sample size. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MPE indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean prediction error percentage (MPE or ME%) | percentage metric | accuracy or bias | percentage of MPE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MPE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean absolute prediction error (MAE) | media of the difference | precision | sum of absolute errors divided by the sample size. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MAE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Mean absolute prediction error percentage (MAPE or MAE%) | percentage metric | precision | percentage of MAPE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MAPE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Root mean squared error (RMSE) | squared root | precision | It quantifies the differences between predicted values and actual values, squaring the errors, taking the mean, and then finding the square root. It is computed by taking the square root of MSE. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ Lower values indicating better predictive accuracy. |

|

| Root mean squared error percentage (RMSE%) | squared root relative | precision | percentage of the RMSE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower RMSE% indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Median prediction error percentage (MDPE%) | median | precision | MDPE is found by ordering PE from smallest to largest, and using this middle value |

% | Values between 0 to 100- A lower MDPE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Median absolute prediction error percentage (MDAPE%) | median | precision | MDAPE is found by ordering the APE from smallest to largest and using this middle value. |

concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MDAPE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Mean relative error (MRE) | relative ratio | accuracy or bias | MRE was defined as the ratio between MAPE and the reference E-field magnitude within the corresponding target region. | no units |

Values between 0 to 1 |

|

| Mean relative error percentage (MRE% or rMPE) | relative percentage | accuracy or bias | percentage of MRE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MRE% indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Square prediction error (SPE) | square of the difference | precision | measures the expected squared distance between what your predictor predicts for a specific value and what the true value | square concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower SPE indicates a better model. |

|

| Mean square error (MSE) | mean of the difference | precision | squaring the difference between the predicted value and actual value and averaging it across the dataset. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ MSE increases exponentially with an increase in error. A good model will have an MSE value closer to zero. |

|

| relative mean prediction error (RMPE or rMPE) |

relative percentage | accuracy or bias | is a variant of Root MPE, gauging predictive model accuracy relative to the target variable range. | % | Value between 0 to 100. Lower rMPE shows lower deviation. |

|

| relative root mean squared error (RRMSE or rRMSE) |

relative percentage | accuracy or bias | is a variant of RMSE, gauging predictive model accuracy relative to the target variable range. | % | Value between 0 to 100. < 10% is an excellent value for RRMSE. > 30 %is a poor value for RRMSE. |

| Metric | Type of statistical metric | Type of evaluation | Definition | Formula | Units | Interpretation |

| Coefficient of determination (R-squared) R² |

regression metric | accuracy or bias | proportion of the total variance of the variable explained by the regression | no units | Represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable which is explained by the linear regression model. Values between 0 to 1, where 1 is the best value. |

|

| Prediction error (PE) | difference | accuracy or bias | difference between the predicted and observed concentrations | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower PE indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Prediction error percentage (PE%) | percentage metric |

accuracy or bias | percentage of PE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower PE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Absolute prediction error (AE) | difference | accuracy or bias | difference between the predicted and observatory concentrations in absolute values. |

|

concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower APE indicates superior model accuracy |

| Absolute prediction error percentage (APE or AE%) | percentage metric | accuracy or bias | percentage of APE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower APE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean prediction error (ME) | media of the difference | accuracy or bias | sum of prediction errors divided by the sample size. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MPE indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean prediction error percentage (MPE or ME%) | percentage metric | accuracy or bias | percentage of MPE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MPE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Mean absolute prediction error (MAE) | media of the difference | precision | sum of absolute errors divided by the sample size. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MAE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Mean absolute prediction error percentage (MAPE or MAE%) | percentage metric | precision | percentage of MAPE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MAPE% indicates superior model accuracy |

|

| Root mean squared error (RMSE) | squared root | precision | It quantifies the differences between predicted values and actual values, squaring the errors, taking the mean, and then finding the square root. It is computed by taking the square root of MSE. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ Lower values indicating better predictive accuracy. |

|

| Root mean squared error percentage (RMSE%) | squared root relative | precision | percentage of the RMSE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower RMSE% indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Median prediction error percentage (MDPE%) | median | precision | MDPE is found by ordering PE from smallest to largest, and using this middle value |

% | Values between 0 to 100- A lower MDPE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Median absolute prediction error percentage (MDAPE%) | median | precision | MDAPE is found by ordering the APE from smallest to largest and using this middle value. |

concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower MDAPE indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Mean relative error (MRE) | relative ratio | accuracy or bias | MRE was defined as the ratio between MAPE and the reference E-field magnitude within the corresponding target region. | no units |

Values between 0 to 1 |

|

| Mean relative error percentage (MRE% or rMPE) | relative percentage | accuracy or bias | percentage of MRE | % | Values between 0 to 100. A lower MRE% indicates superior model accuracy. |

|

| Square prediction error (SPE) | square of the difference | precision | measures the expected squared distance between what your predictor predicts for a specific value and what the true value | square concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ A lower SPE indicates a better model. |

|

| Mean square error (MSE) | mean of the difference | precision | squaring the difference between the predicted value and actual value and averaging it across the dataset. | concentration units | Values between 0 to ∞ MSE increases exponentially with an increase in error. A good model will have an MSE value closer to zero. |

|

| relative mean prediction error (RMPE or rMPE) |

relative percentage | accuracy or bias | is a variant of Root MPE, gauging predictive model accuracy relative to the target variable range. | % | Value between 0 to 100. Lower rMPE shows lower deviation. |

|

| relative root mean squared error (RRMSE or rRMSE) |

relative percentage | accuracy or bias | is a variant of RMSE, gauging predictive model accuracy relative to the target variable range. | % | Value between 0 to 100. < 10% is an excellent value for RRMSE. > 30 %is a poor value for RRMSE. |

3. Discussion

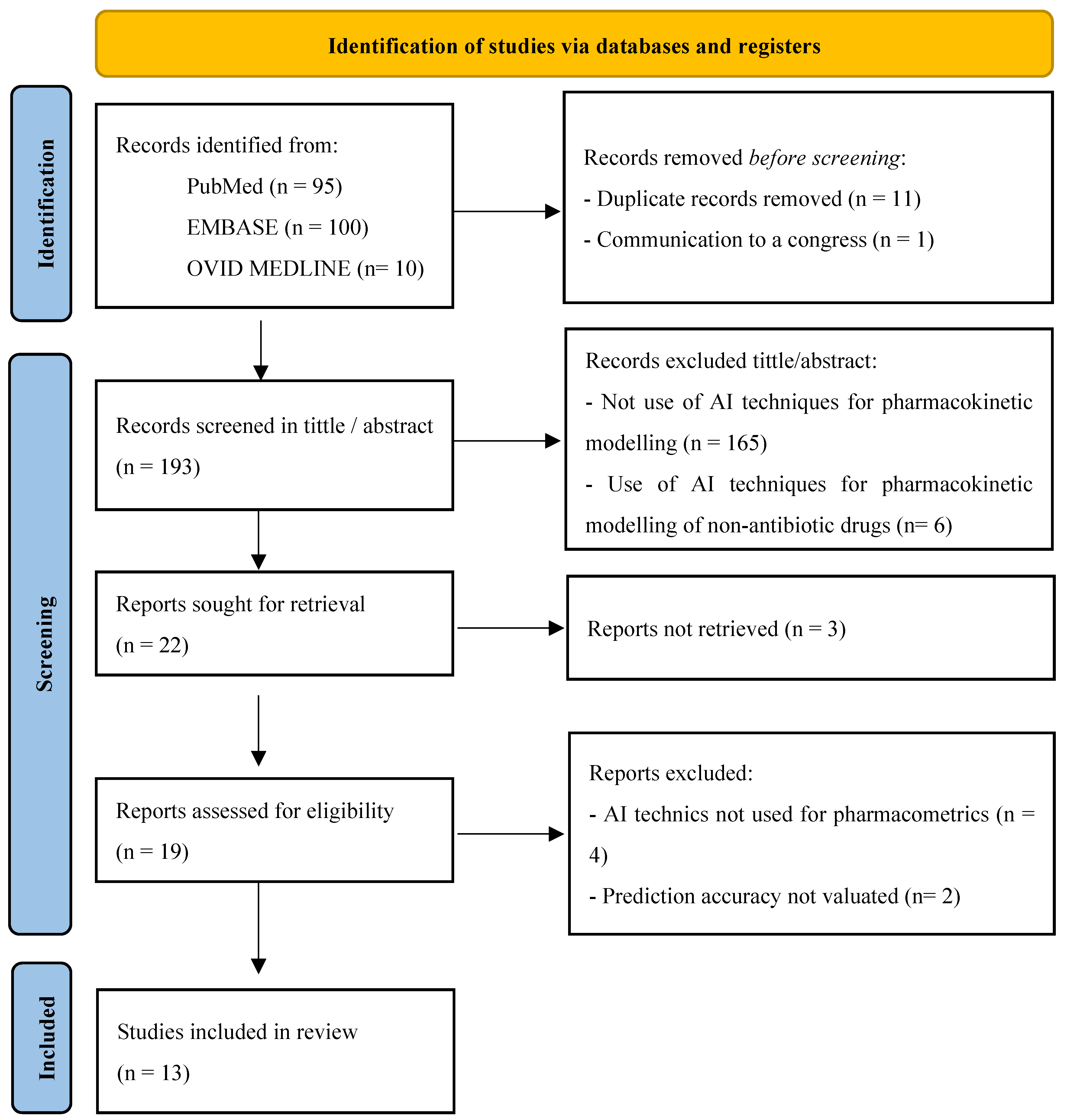

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Objectives

4.2. Search Strategy

4.3. Eligibility Criteria

4.4. Data Extraction

4.5. Synthesis of Results

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schwalbe, N.; Wahl, B. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Global Health. Lancet 2020, 395, 1579–1586. [CrossRef]

- Haymond, S.; McCudden, C. Rise of the Machines: Artificial Intelligence and the Clinical Laboratory. J Appl Lab Med 2021, 6, 1640–1654. [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) Organización Mundial de la Salud: Cibersalud. Cibersalud y bienestar Digital 2018.

- Chaturvedula, A.; Calad-Thomson, S.; Liu, C.; Sale, M.; Gattu, N.; Goyal, N. Artificial Intelligence and Pharmacometrics: Time to Embrace, Capitalize, and Advance? CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2019, 8, 440–443. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, L.; Steiert, B.; Soubret, A.; Wagg, J.; Phipps, A.; Peck, R.; Charoin, J.-E.; Ribba, B. Models and Machines: How Deep Learning Will Take Clinical Pharmacology to the Next Level. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2019, 8, 131–134. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, D.R.; Luciano, F.C.; Anaya, B.J.; Ongoren, B.; Kara, A.; Molina, G.; Ramirez, B.I.; Sánchez-Guirales, S.A.; Simon, J.A.; Tomietto, G.; et al. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Applications in Drug Discovery and Drug Delivery: Revolutionizing Personalized Medicine. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1328. [CrossRef]

- Hinkson, I.V.; Madej, B.; Stahlberg, E.A. Accelerating Therapeutics for Opportunities in Medicine: A Paradigm Shift in Drug Discovery. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 770. [CrossRef]

- Revolutionizing Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Review of AI Applications Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2813-2998/3/1/9 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Raja, K.; Patrick, M.; Elder, J.T.; Tsoi, L.C. Machine Learning Workflow to Enhance Predictions of Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) through Drug-Gene Interactions: Application to Drugs for Cutaneous Diseases. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 3690. [CrossRef]

- Salas, M.; Petracek, J.; Yalamanchili, P.; Aimer, O.; Kasthuril, D.; Dhingra, S.; Junaid, T.; Bostic, T. The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Pharmacovigilance: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Pharmaceut Med 2022, 36, 295–306. [CrossRef]

- Basile, A.O.; Yahi, A.; Tatonetti, N.P. Artificial Intelligence for Drug Toxicity and Safety. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2019, 40, 624–635. [CrossRef]

- Reker, D.; Shi, Y.; Kirtane, A.R.; Hess, K.; Zhong, G.J.; Crane, E.; Lin, C.-H.; Langer, R.; Traverso, G. Machine Learning Uncovers Food- and Excipient-Drug Interactions. Cell Rep 2020, 30, 3710-3716.e4. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Luo, F.; Tian, G.; Li, X. Predicting Potential Drug-Drug Interactions by Integrating Chemical, Biological, Phenotypic and Network Data. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 18. [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.J.; Rieger, T.R.; Musante, C.J. Efficient Generation and Selection of Virtual Populations in Quantitative Systems Pharmacology Models. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2016, 5, 140–146. [CrossRef]

- Gal, J.; Milano, G.; Ferrero, J.-M.; Saâda-Bouzid, E.; Viotti, J.; Chabaud, S.; Gougis, P.; Le Tourneau, C.; Schiappa, R.; Paquet, A.; et al. Optimizing Drug Development in Oncology by Clinical Trial Simulation: Why and How? Brief Bioinform 2018, 19, 1203–1217. [CrossRef]

- McComb, M.; Bies, R.; Ramanathan, M. Machine Learning in Pharmacometrics: Opportunities and Challenges. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2022, 88, 1482–1499. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.; Bennis, F.C.; Mathôt, R.A.A. Adoption of Machine Learning in Pharmacometrics: An Overview of Recent Implementations and Their Considerations. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1814. [CrossRef]

- Gobburu, J.V.; Chen, E.P. Artificial Neural Networks as a Novel Approach to Integrated Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Analysis. J Pharm Sci 1996, 85, 505–510. [CrossRef]

- Otalvaro, J.D.; Yamada, W.M.; Hernandez, A.M.; Zuluaga, A.F.; Chen, R.; Neely, M.N. A Proof of Concept Reinforcement Learning Based Tool for Non Parametric Population Pharmacokinetics Workflow Optimization. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ota, R.; Yamashita, F. Application of Machine Learning Techniques to the Analysis and Prediction of Drug Pharmacokinetics. J Control Release 2022, 352, 961–969. [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.; Pfister, M.; Daunhawer, I.; Wilbaux, M.; Wellmann, S.; Vogt, J.E. Pharmacometrics and Machine Learning Partner to Advance Clinical Data Analysis. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2020, 107, 926–933.

- Priya, S.; Tripathi, G.; Singh, D.B.; Jain, P.; Kumar, A. Machine Learning Approaches and Their Applications in Drug Discovery and Design. Chem Biol Drug Des 2022, 100, 136–153. [CrossRef]

- Keutzer, L.; You, H.; Farnoud, A.; Nyberg, J.; Wicha, S.G.; Maher-Edwards, G.; Vlasakakis, G.; Moghaddam, G.K.; Svensson, E.M.; Menden, M.P.; et al. Machine Learning and Pharmacometrics for Prediction of Pharmacokinetic Data: Differences, Similarities and Challenges Illustrated with Rifampicin. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1530. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Alffenaar, J.-W.C.; Bassetti, M.; Bracht, H.; Dimopoulos, G.; Marriott, D.; Neely, M.N.; Paiva, J.-A.; Pea, F.; Sjovall, F.; et al. Antimicrobial Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Critically Ill Adult Patients: A Position Paper#. Intensive Care Med 2020, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Downes, K.J.; Goldman, J.L. Too Much of a Good Thing: Defining Antimicrobial Therapeutic Targets to Minimize Toxicity. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021, 109, 905–917. [CrossRef]

- Rawson, T.M.; Wilson, R.C.; O’Hare, D.; Herrero, P.; Kambugu, A.; Lamorde, M.; Ellington, M.; Georgiou, P.; Cass, A.; Hope, W.W.; et al. Optimizing Antimicrobial Use: Challenges, Advances and Opportunities. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 747–758. [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Cunha, C.B. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs: Principles and Practice. Med Clin North Am 2018, 102, 797–803. [CrossRef]

- Chua, H.C.; Tse, A.; Smith, N.M.; Mergenhagen, K.A.; Cha, R.; Tsuji, B.T. Combatting the Rising Tide of Antimicrobial Resistance: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Dosing Strategies for Maximal Precision. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2021, 57, 106269. [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.A.; Wright, G.D. The Past, Present, and Future of Antibiotics. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14, eabo7793. [CrossRef]

- Stokes, J.M.; Yang, K.; Swanson, K.; Jin, W.; Cubillos-Ruiz, A.; Donghia, N.M.; MacNair, C.R.; French, S.; Carfrae, L.A.; Bloom-Ackermann, Z.; et al. A Deep Learning Approach to Antibiotic Discovery. Cell 2020, 180, 688-702.e13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, A.; Tao, F. Artificial intelligence in product lifecycle management. | International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology | EBSCOhost Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/contentitem/doi:10.1007%2Fs00170-021-06882-1?sid=ebsco:plink:crawler&id=ebsco:doi:10.1007%2Fs00170-021-06882-1 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Talevi, A.; Morales, J.F.; Hather, G.; Podichetty, J.T.; Kim, S.; Bloomingdale, P.C.; Kim, S.; Burton, J.; Brown, J.D.; Winterstein, A.G.; et al. Machine Learning in Drug Discovery and Development Part 1: A Primer. CPT: Pharmacometrics & Systems Pharmacology 2020, 9, 129–142. [CrossRef]

- Stankevičiūtė, K.; Woillard, J.-B.; Peck, R.W.; Marquet, P.; van der Schaar, M. Bridging the Worlds of Pharmacometrics and Machine Learning. Clin Pharmacokinet 2023, 62, 1551–1565. [CrossRef]

- Poweleit, E.A.; Vinks, A.A.; Mizuno, T. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches to Facilitate Therapeutic Drug Management and Model-Informed Precision Dosing. Ther Drug Monit 2023, 45, 143–150. [CrossRef]

- Bououda, M.; Uster, D.W.; Sidorov, E.; Labriffe, M.; Marquet, P.; Wicha, S.G.; Woillard, J.-B. A Machine Learning Approach to Predict Interdose Vancomycin Exposure. Pharm Res 2022, 39, 721–731. [CrossRef]

- Ponthier, L.; Ensuque, P.; Destere, A.; Marquet, P.; Labriffe, M.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E.; Woillard, J.-B. Optimization of Vancomycin Initial Dose in Term and Preterm Neonates by Machine Learning. Pharm Res 2022, 39, 2497–2506. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ong, C.L.J.; Fu, Z. AI Models to Assist Vancomycin Dosage Titration. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 801928. [CrossRef]

- Nigo, M.; Tran, H.T.N.; Xie, Z.; Feng, H.; Mao, B.; Rasmy, L.; Miao, H.; Zhi, D. PK-RNN-V E: A Deep Learning Model Approach to Vancomycin Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Using Electronic Health Record Data. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2022, 133, 104166. [CrossRef]

- Miyai, T.; Imai, S.; Yoshimura, E.; Kashiwagi, H.; Sato, Y.; Ueno, H.; Takekuma, Y.; Sugawara, M. Machine Learning-Based Model for Estimating Vancomycin Maintenance Dose to Target the Area under the Concentration Curve of 400-600 Mg·h/L in Japanese Patients. Biol Pharm Bull 2022, 45, 1332–1339. [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.-H.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Allegaert, K.; Hao, G.-X.; Yao, B.-F.; Leroux, S.; Thomson, A.H.; Yu, Z.; Gao, F.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Use of Machine Learning for Dosage Individualization of Vancomycin in Neonates. Clin Pharmacokinet 2023, 62, 1105–1116. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yu, Z.; Bu, S.; Lin, Z.; Hao, X.; He, W.; Yu, P.; Wang, Z.; Gao, F.; Zhang, J.; et al. An Ensemble Model for Prediction of Vancomycin Trough Concentrations in Pediatric Patients. Drug Des Devel Ther 2021, 15, 1549–1559. [CrossRef]

- Brier, M.E.; Zurada, J.M.; Aronoff, G.R. Neural Network Predicted Peak and Trough Gentamicin Concentrations. Pharm Res 1995, 12, 406–412. [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, S.; Kawada, K.; Takehira, R.; Nishizawa, K.; Katayama, S.; Hirano, M.; Momose, Y. Artificial Neural Network Modeling to Predict the Plasma Concentration of Aminoglycosides in Burn Patients. Biomed Pharmacother 2004, 58, 239–244. [CrossRef]

- Chow, H.H.; Tolle, K.M.; Roe, D.J.; Elsberry, V.; Chen, H. Application of Neural Networks to Population Pharmacokinetic Data Analysis. J Pharm Sci 1997, 86, 840–845. [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghe, J.; Dhaese, S.A.M.; De Corte, T.; Vander Mijnsbrugge, D.; Aardema, H.; Zijlstra, J.G.; Verstraete, A.G.; Stove, V.; Colin, P.; Ongenae, F.; et al. Development and Evaluation of Uncertainty Quantifying Machine Learning Models to Predict Piperacillin Plasma Concentrations in Critically Ill Patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2022, 22, 224. [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.-H.; Guan, Z.; Allegaert, K.; Wu, Y.-E.; Manolis, E.; Leroux, S.; Yao, B.-F.; Shi, H.-Y.; Li, X.; Huang, X.; et al. Drug Clearance in Neonates: A Combination of Population Pharmacokinetic Modelling and Machine Learning Approaches to Improve Individual Prediction. Clin Pharmacokinet 2021, 60, 1435–1448. [CrossRef]

- Manickam, P.; Mariappan, S.A.; Murugesan, S.M.; Hansda, S.; Kaushik, A.; Shinde, R.; Thipperudraswamy, S.P. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) Assisted Biomedical Systems for Intelligent Healthcare. Biosensors (Basel) 2022, 12, 562. [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.-C.; Lin, Z. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling. Toxicol Sci 2023, 191, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Mørk, M.L.; Andersen, J.T.; Lausten-Thomsen, U.; Gade, C. The Blind Spot of Pharmacology: A Scoping Review of Drug Metabolism in Prematurely Born Children. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 828010. [CrossRef]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Fisher, B.T.; Zaoutis, T.E. Invasive Fungal Infections in the Paediatric and Neonatal Population: Diagnostics and Management Issues. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009, 15, 613–624. [CrossRef]

- El Hassani, M.; Marsot, A. External Evaluation of Population Pharmacokinetic Models for Precision Dosing: Current State and Knowledge Gaps. Clin Pharmacokinet 2023, 62, 533–540. [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Katanoda, T.; Hashiguchi, Y.; Kondo, S.; Narita, Y.; Iwamura, K.; Nosaka, K.; Jono, H.; Saito, H. Development and Evaluation of a Vancomycin Dosing Nomogram to Achieve the Target Area under the Concentration-Time Curve. A Retrospective Study. J Infect Chemother 2020, 26, 444–450. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.H.; Staatz, C.E.; Tobin, C.M.; Gall, M.; Lovering, A.M. Development and Evaluation of Vancomycin Dosage Guidelines Designed to Achieve New Target Concentrations. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009, 63, 1050–1057. [CrossRef]

- FDA, U. Population Pharmacokinetics: Guidance for Industry. 2022; 2023;

- Agency, E.M. Guideline on Bioanalytical Method Validation; London, UK, 2011;

- Kanji, S.; Hayes, M.; Ling, A.; Shamseer, L.; Chant, C.; Edwards, D.J.; Edwards, S.; Ensom, M.H.H.; Foster, D.R.; Hardy, B.; et al. Reporting Guidelines for Clinical Pharmacokinetic Studies: The ClinPK Statement. Clin Pharmacokinet 2015, 54, 783–795. [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zhang, S. Comment on: “External Evaluation of Population Pharmacokinetic Models for Precision Dosing: Current State and Knowledge Gaps.” Clin Pharmacokinet 2023, 62, 1183–1185. [CrossRef]

- Sheiner, L.B.; Beal, S.L. Some Suggestions for Measuring Predictive Performance. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1981, 9, 503–512. [CrossRef]

- Brendel, K.; Dartois, C.; Comets, E.; Lemenuel-Diot, A.; Laveille, C.; Tranchand, B.; Girard, P.; Laffont, C.M.; Mentré, F. Are Population Pharmacokinetic and/or Pharmacodynamic Models Adequately Evaluated? A Survey of the Literature from 2002 to 2004. Clin Pharmacokinet 2007, 46, 221–234. [CrossRef]

- Miyabe-Nishiwaki, T.; Masui, K.; Kaneko, A.; Nishiwaki, K.; Nishio, T.; Kanazawa, H. Evaluation of the Predictive Performance of a Pharmacokinetic Model for Propofol in Japanese Macaques (Macaca Fuscata Fuscata). J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2013, 36, 169–173. [CrossRef]

- Struys, M.; Absalom, A.; Shafer, S.L. “Intravenous Drug Delivery Systems” in Miller’s Anesthesia. In “Intravenous Drug Delivery Systems” in Miller’s Anesthesia; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 919–957 ISBN 978-0-7020-5283-5.

- Aung, Y.Y.M.; Wong, D.C.S.; Ting, D.S.W. The Promise of Artificial Intelligence: A Review of the Opportunities and Challenges of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Br Med Bull 2021, 139, 4–15. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhi, H.; Dong, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Shen, H.; Wang, Y. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Past, Present and Future. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2017, 2, 230–243. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).