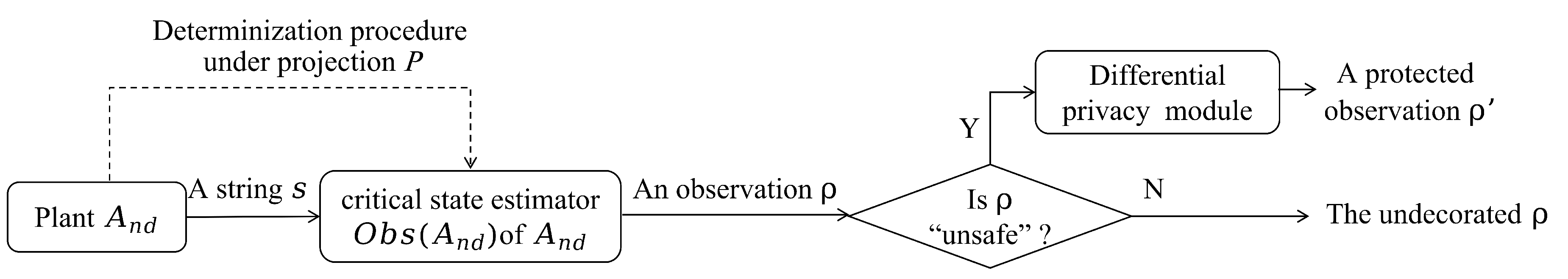

In this section, we aim to design a DPM to enforce critical observability for DESs modeled with DFAs, and to ensure that the predefined critical states cannot be detected to intruders. Specifically, we first define the Hamming distance of two state sequences in a DFA to describe the difference between them. Then, to prevent critical states or critical observability violative states from being captured by an intruder, we define a novel DPM for DFAs, called state sequence DP. Finally, an algorithm that provides a probability distribution for the generation of each state in an output state sequence is proposed and the DPM is designed.

4.1. Problem Statement

In , when an unsafe observation is generated, we can design a DPM associated with to effectively conceal the unsafe observation. In particular, given an observation , we derive its corresponding production state sequence . By inputting and a random production state sequence , such that the Hamming distance between and is restricted to a bound , into the designed mechanism, a protected production state sequence is output with approximate probability, where the lengths of , , and are equal (i.e., ). Since both and can lead to the generation of with probabilities that are sufficiently close, it becomes impossible for an intruder to determine whether or is generated by the estimator . In other words, from the observed behavior contained in , the intruder cannot infer its corresponding input behavior, and thereby the unsafe observation is not identifiable. Before discussing the use of DP to protect unsafe observations from being acquired, we first provide some definitions.

Definition 3 (Hamming distance). Given two production state sequences and generated by a critical state estimator with the same length ( = ), the Hamming distance between and is defined as , where represents the j-th entry of production state sequence , , and . ♢

Let

be a critical state estimator of

,

be a positive integer representing the length of a production state sequence, and

be a parameter. We define

as the set of all pairs of production state sequences

with

and the Hamming distance

between them is less than or equal to

l, i.e.,

Considering Definition 1 and the properties of DES models, we now define state sequence DP in a DFA.

Definition 4 (State sequence differential privacy).

Given an NFA , let be its critical state estimator and be the set of state sequences with length k in . Let be a real number. A mechanism is said to be of state sequence DP w.r.t. if for all production state sequence pairs and for all , it holds

where represents the probability of with . ♢

According to Definition 4, a mechanism that guarantees DP of state sequences w.r.t. implies that for all pairs of production state sequences with , and for all possible output production state sequences , the probability of being decorated as and that of being decorated as is close enough such that an intruder cannot identify which is the real input to .

To evaluate the performance of the mechanism, we introduce the concept of the security degree of a state sequence. Given an NFA , a set of observable events , a set of critical states , and the critical state estimator of , let be a state sequence in . If the production state sequence is safe, the security degree of is defined as , where with . Otherwise, the sequence is unsafe, whose security degree is defined as . In other words, the state sequence consistent with an observation that violates critical observability or reveals the critical states (i.e., or ) has the lowest security level. Note that for all , is unique. Given a production state sequence in , a larger value means that the set of critical observability violative states or the set of critical states is less likely to be detected by an intruder.

Consider a critical state estimator

of a system

and a parameter

. The maximum security degree of production state sequences

contained in

is defined as

1.

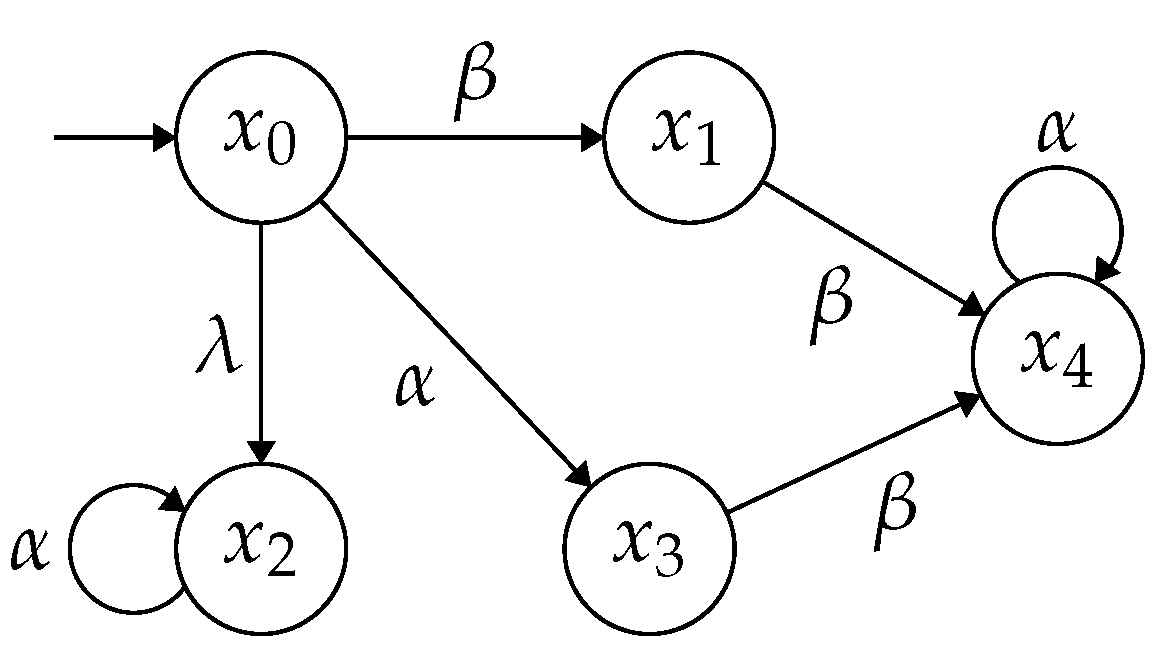

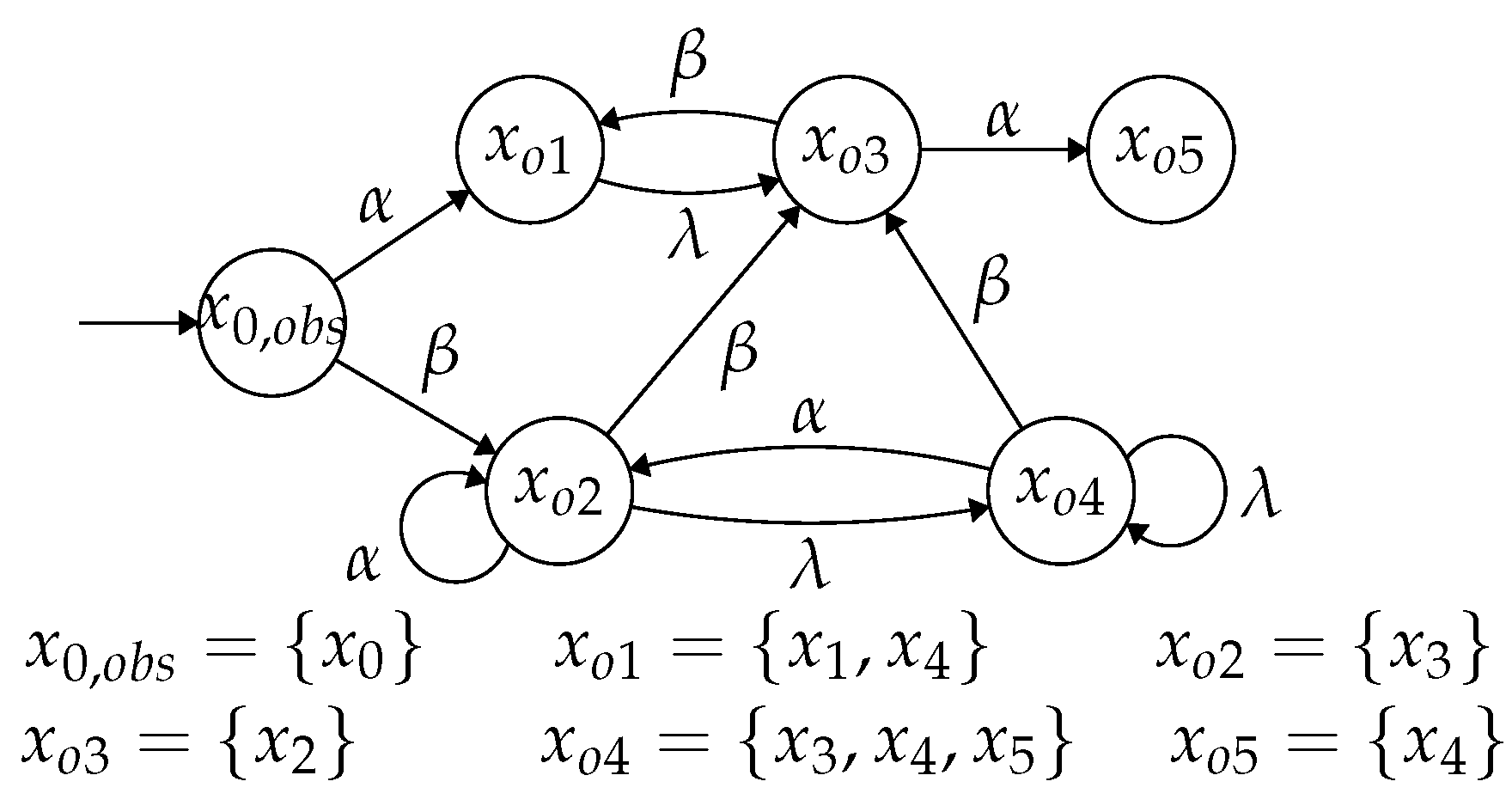

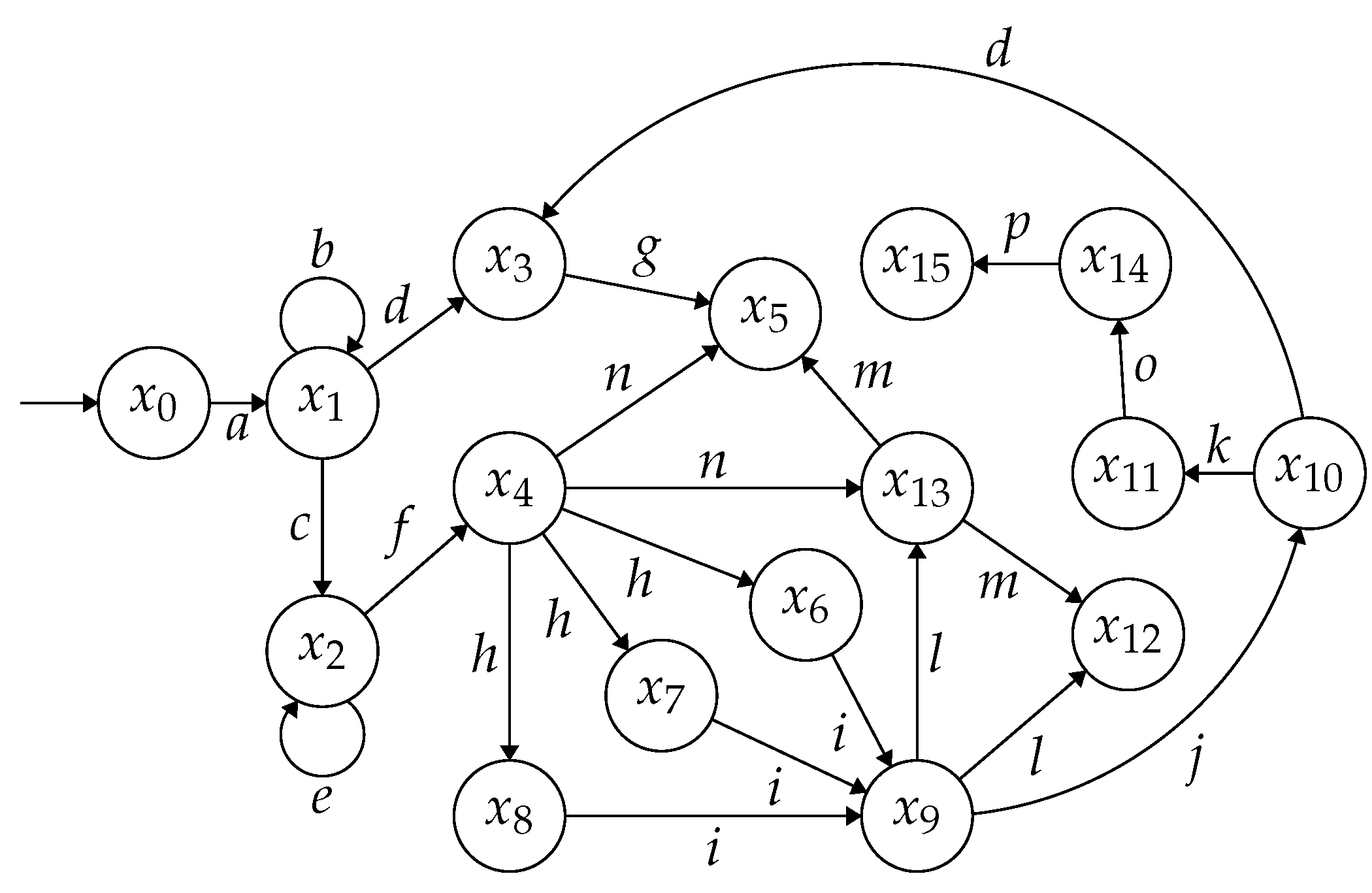

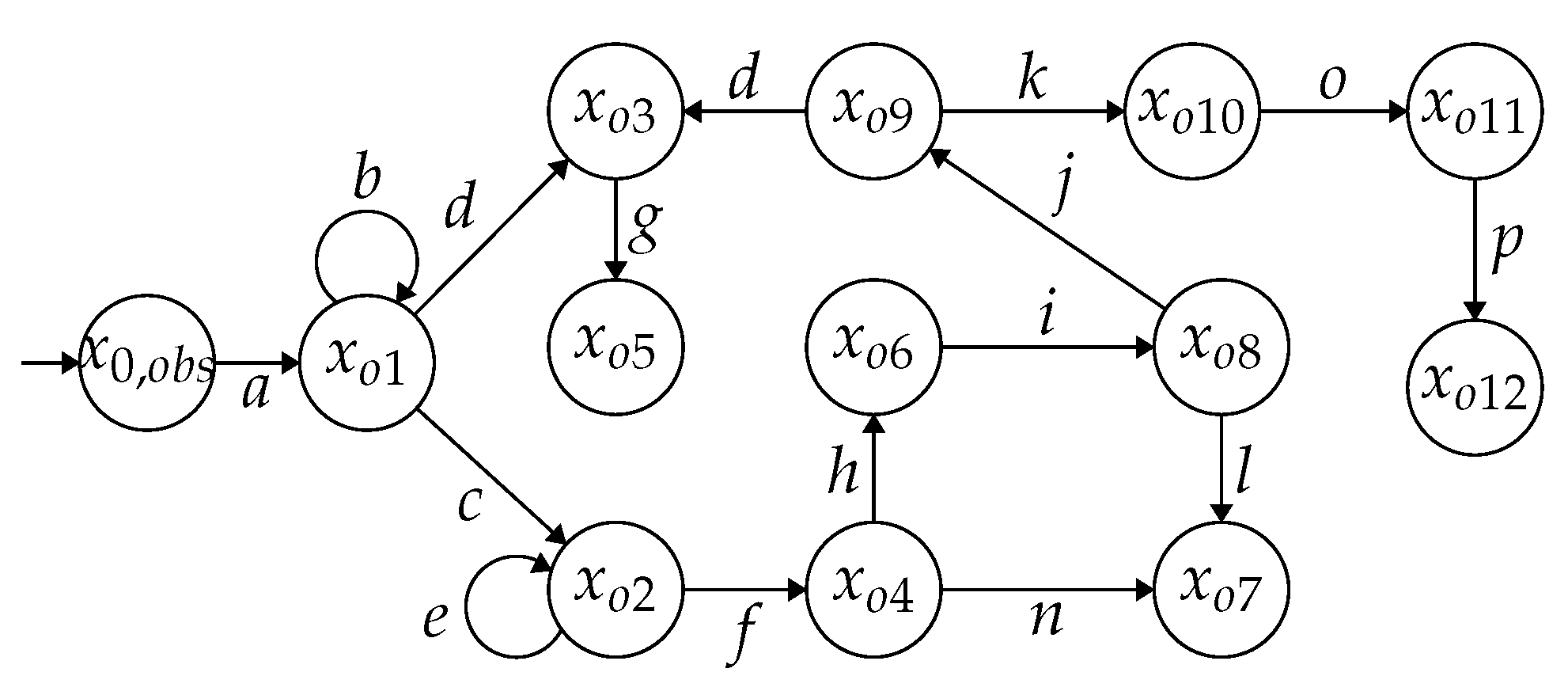

Example 3. Consider the NFA and a set of critical states in Example 2. Let be a production of portrayed in Figure 4 with . The security degree of ω is 2, i.e., . Given another production , the production state sequence is unsafe and has the lowest security degree thanks to . Given a non-negative integer representing the length of a state sequence, we have . □

In this paper, we focus on a mechanism that provides the highest degree of protection for an unsafe production state sequence. In simpler terms, the mechanism is capable of confusing unsafe state sequences with safe ones that have the maximum security degree. In particular, the designed mechanism w.r.t. ensures that, for an unsafe production state sequence , there exists a production state sequence with maximum degree such that and for all .

The distance bound l is another parameter that significantly impacts the performance of the mechanism . Given an unsafe state sequence , it is crucial to select a value l that is as small as possible while guaranteeing that the mechanism can maximally confuse with . In other words, the state sequence , which serves as a suitable alternative for , should exhibit the utmost similarity to .

Definition 5. Let be an NFA that is not critically observable, be a set of critical states, be a set of observable events, be a critical state estimator of , and be a mechanism that provides state sequence DP w.r.t. . Given an unsafe state sequence , the mechanism is optimal w.r.t. if it satisfies the following statements:

There exists a production state sequence in with such that , holds;

For all , the inequality holds;

For all in with , , there does not exist () such that , . ♢

According to Definition 5, given an unsafe , condition 1) ensures that there exists at least one state sequence with the maximum security degree such that belongs to the set . Condition 2) indicates that an optimal mechanism provides (guarantees) the state sequence DP w.r.t. . Condition 3) implies that the parameter l with must be minimal for all state sequences that satisfy . In the following, we will detail the design of an optimal mechanism that satisfies the definition of state sequence DP.

4.2. State Sequence Differential Privacy

Based on Definitions 4 and 5, we first design a probability allocation strategy for the optimal mechanism in a critical state estimator of system . Given an unsafe input production state sequence , the aim is to generate a random state sequence with a certain probability from such that . Specifically, the strategy to be defined enables assigning a probability to each state included in the output production state sequence , where . Then, by multiplying the probabilities of all output states (), we can obtain the probability of generating , i.e., . In terms of the strategy, we explore the conditions for ensuring the DP of state sequences and further design an algorithm to synthesize this optimal mechanism .

Given a critical state estimator

,

, let

be a mechanism that takes a production state sequence

as input and

as output. Before elaborating on the probability allocation strategy to a state in

, we introduce an indicator function denoted as

for two states

, defined as follows:

where

. If

included in

satisfies

, it is considered a correct state. On the other hand, if

, the state

is referred to as an incorrect state.

Now, we describe a probability allocation strategy that assigns a probability

to each state

in the state sequence

, where

. Given an input production state sequence

, let

be the set that collects all the states in

, i.e.,

. The strategy for

associated with

is a (partial) function

that outputs a probability of generating state

in relation to two states

and

, where

. Particularly, for the initial state, we define

, and it is assigned a probability value

. Then, for all

, if

is a correct state, it is allocated a correct probability

(the value of

is examined in detail in Theorem 1). On the other hand, if

is not a correct state, let

|

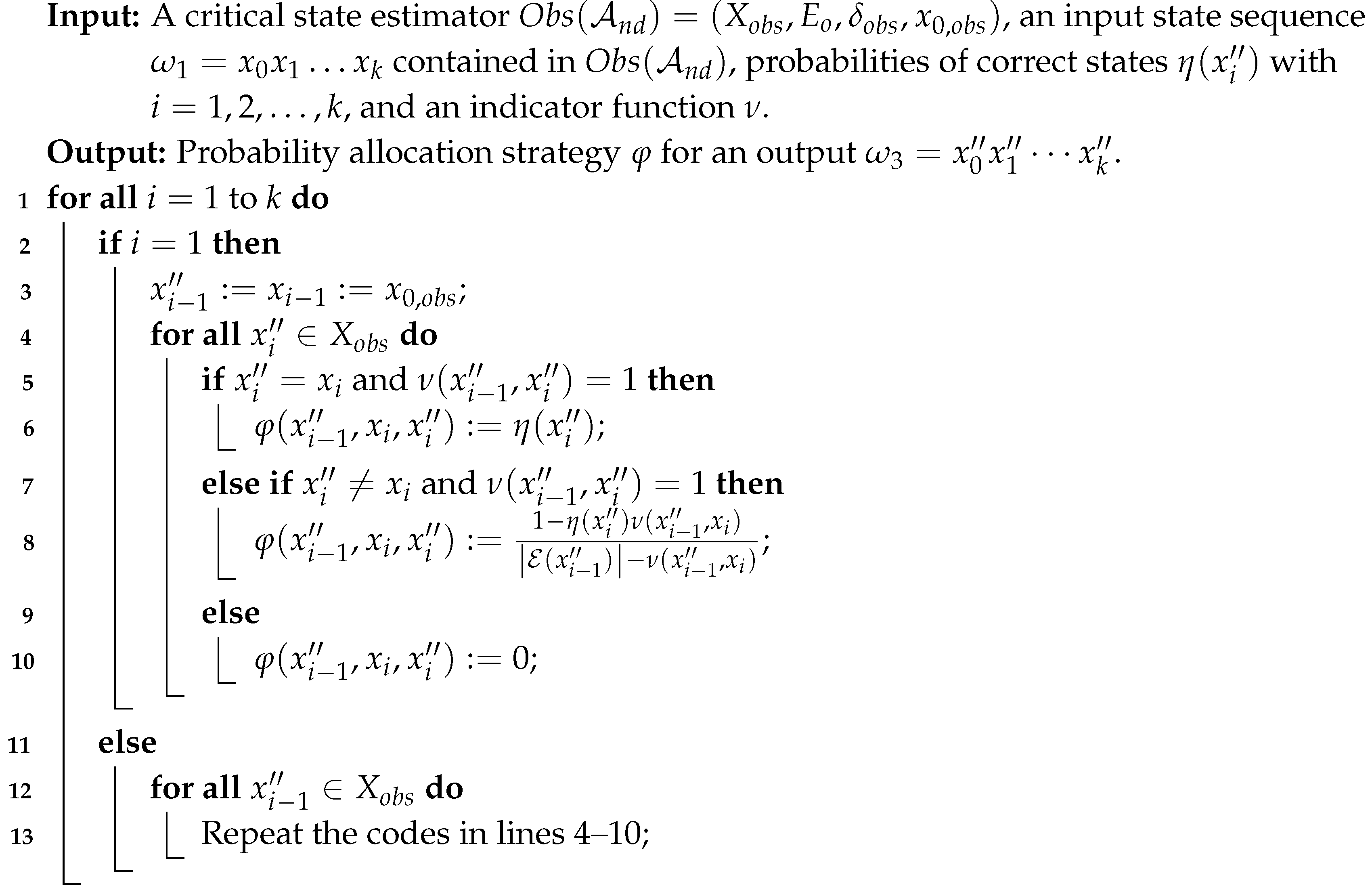

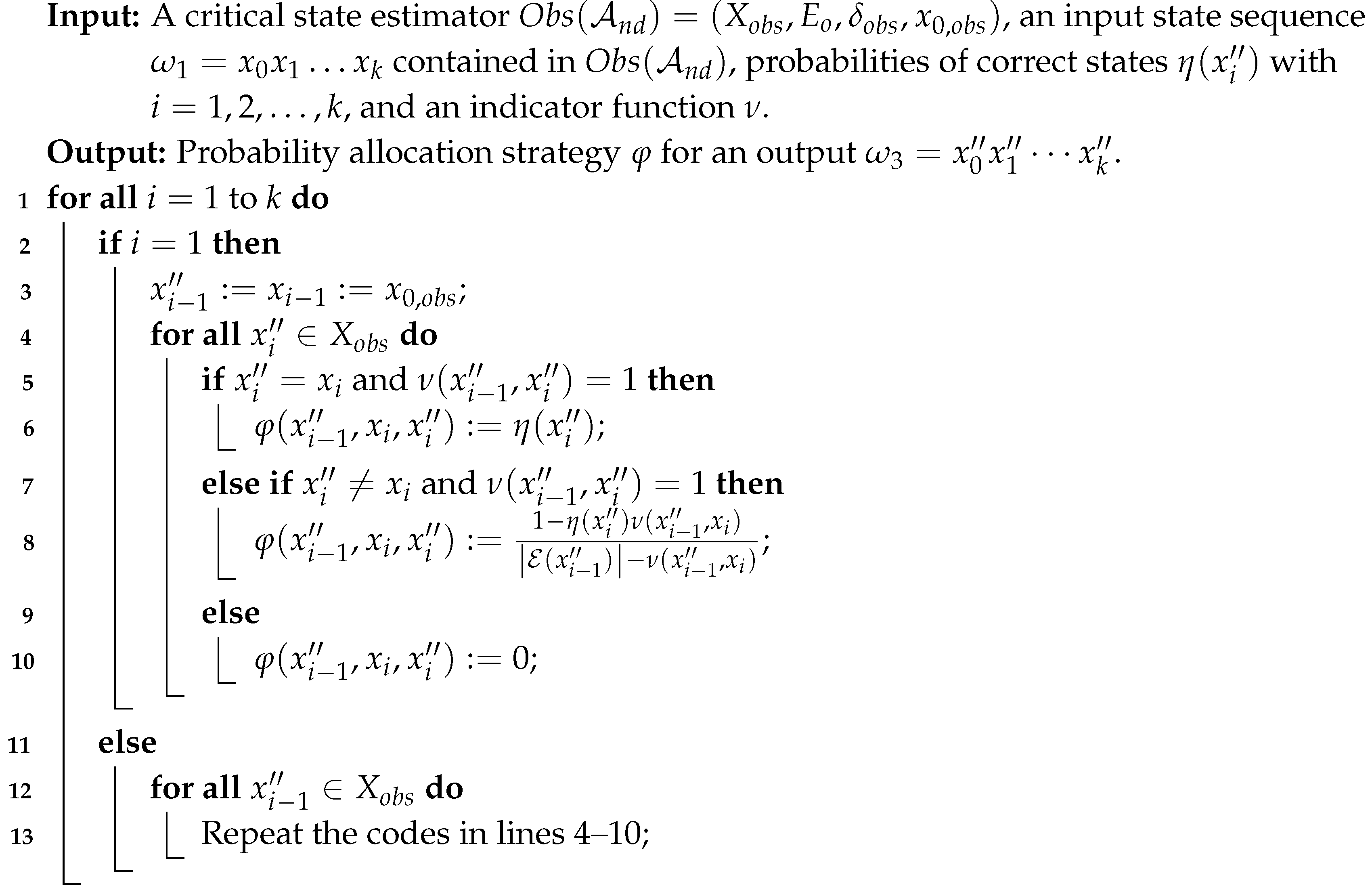

Algorithm 1: A probability Allocation Strategy . |

|

Then, we design an algorithm (namely Algorithm 1) to compute the probability allocation strategy

for a random output

associated with an input state sequence

. The algorithm takes as input a critical state estimator, an input state sequence, probabilities of correct states, and an indicator function. It iterates through each state in the input sequence and calculates the probability of generating each possible output state based on the given probabilities of correct states and the indicator function. In Algorithm 1, for all

, if

, we have

. For each possible state

, it checks whether

and whether the indicator function

. If both conditions hold, the correct state

is allocated a correct probability

. If

and the indicator function

, the state

is assigned an incorrect probability

Otherwise, if

,

is defined. If

, for all

, the codes in lines 4–10 are repeated. The computational complexity of Algorithm 1 is

.

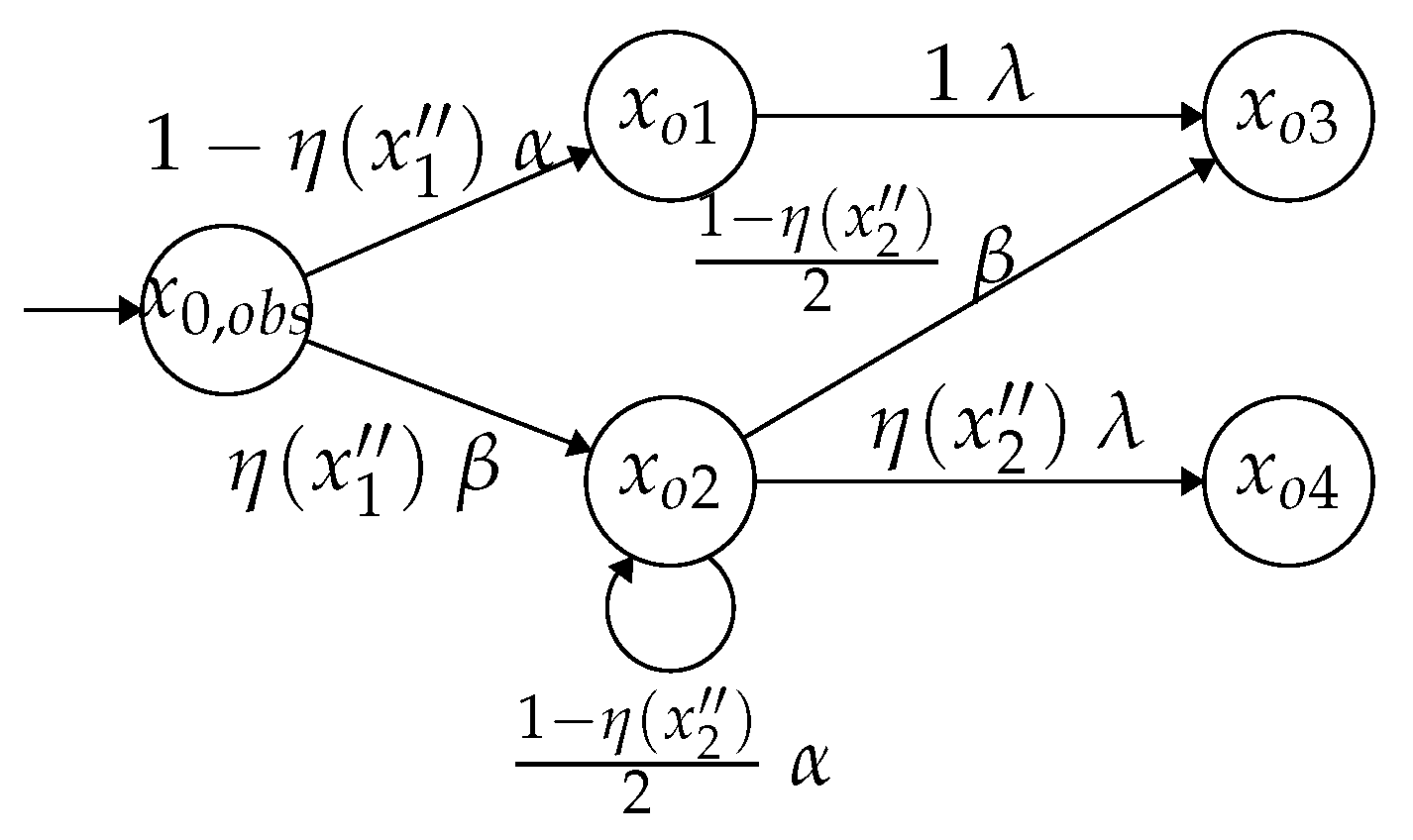

Example 4. Consider a state sequence in the critical state estimator in Figure 4 and feed into a mechanism . Let us elaborate on how to calculate the probability allocation strategy φ for a randomly generated output state sequence with (all possible output state sequences with are illustrated in Figure 5).

If , according to the strategy φ, the state is correct and is assigned a correct probability with (the value of is discussed in Theorem 1); if with , by the line 8 of Algorithm 1, we allocate an incorrect probability to state , i.e., .

At the state , since the feasible state is not correct, i.e., and , we have . Analogously, at the state , we have and . □

By utilizing the probability allocation strategy , we are able to synthesize a mechanism that generates a production state sequence assigned with a probability. In other words, for all states contained in , the probability of generating is given by with . Now, we demonstrate the condition of for a mechanism to provide state sequence DP w.r.t. , based on Algorithm 1.

Theorem 1.

Given a critical state estimator of a system that is not critically observable, let be a real number, be a parameter, be the length of a state sequence, be a mechanism whose probability allocation strategy is computed by Algorithm 1, and () be a correct state contained in an output state sequence of . The mechanism guarantees state sequence DP w.r.t. if the probabilities of correct states satisfy the following condition:

Proof. Let

and

be two production state sequences generated by

such that

. We consider

with

(the initial states in

,

, and

are the same, i.e.,

). By Definition 4, we need to prove the following inequality:

To begin with, we show

. Using Algorithm 1, we have

where

and

.

Note that when

is an incorrect state, the values of

depend on

, i.e.,

We now claim .

1) First, we prove

. One has

2) Let us prove the second inequality

.

The constraint can be proved similarly, which completes the proof. ▪

By Definition 4 and Theorem 1, Algorithm 2 computes an optimal mechanism for an unsafe input state sequence , which aims to prevent the leakage of critical observability violative states or critical states in a non-critically observable system. [2]We use a number in square brackets after a tuple to represent the entries of the tuple.

[3]A number in square brackets after a set of tuples represents the set contained by the entries of the tuple set. Here,

with

.

|

Algorithm 2: Construction of a mechanism . |

|

Algorithm 2 first initializes two empty sets B and G for storing the triplet elements and . Then, it iterates through all the productions with . In lines 3–6, for each such sequence , the algorithm executes three key computations: assigning , the degree of , and the Hamming distance , to , , and , respectively. In line 7, the maximum value in set is computed and is stored in the variable s. Next, for each triplet b in the set B, check whether is equal to the maximum number s. If the condition is true, then add this element b to the set G. In line 11, the value of the parameter h is obtained by calculating the minimum number in set . For all input state sequences and for all , in line 15, we compute the correct probability for each output state . Finally, in lines 16–17, Algorithm 2 synthesizes the mechanism by invoking the probability allocation strategy of Algorithm 1.

The computational complexity of Algorithm 2 is mainly decided by the synthesis of the mechanism in lines 12–17. In lines 12–13, we enumerate all the input and output sequences, resulting in complexity . Furthermore, in lines 14–16, we compute and utilize Algorithm 1 to calculate . This step has complexity . Taking into account the above statements, the complexity can be expressed as , i.e., .

Theorem 2. Consider a critical state estimator of a system that is not critically observable. Let be an unsafe production state sequence in . The mechanism computed by Algorithm 2 guarantees DP of state sequences w.r.t. , in which is a parameter calculated by Algorithm 2. Moreover, the mechanism is optimal w.r.t. an unsafe production state sequence .

Proof. First, we prove that the mechanism

designed in Algorithm 2 provides DP of state sequences w.r.t.

. Specifically, in lines 12–17, for all input state sequences

and any possible output state sequence

, we have

. Besides, we accurately compute the correct state probability

based on Equation (

2). According to Theorem 1, the mechanism

provides DP of state sequences w.r.t.

.

Then we show that the mechanism is optimal w.r.t. the unsafe state sequence . In lines 2–6, for all productions , the security degrees of their corresponding state sequences are calculated and these values are stored in the set . Then the algorithm calculates the Hamming distance between and , which reflects the degree of difference between them. In lines 7–10 of the algorithm, elements b are assigned to G such that . In line 11, for all , the minimum value h in the set is obtained, i.e., compute the minimum value h of the Hamming distance between and . To this end, there exists a state sequence with such that and there does not exist such that for all with the maximum degree. According to Definition 5, the mechanism is optimal. ▪

In Algorithm 2, we design an optimal mechanism w.r.t. an unsafe production state sequence . When the mechanism receives as input, a protected state sequence is probabilistically output. In addition, the mechanism guarantees that there exists at least one state sequence with the maximum security degree such that when is fed, it outputs with an approximate probability. Then, when an intruder obtains an observation derived from , he/she is unable to infer whether or is generated in the critical state estimator . Consequently, the disclosure of critical states or critical observability violative states becomes unattainable for the intruder. Furthermore, in order to maximize the obfuscation effect between and , we especially emphasize the optimization of the parameter h in Algorithm 2, i.e., the Hamming distance between and is minimal.

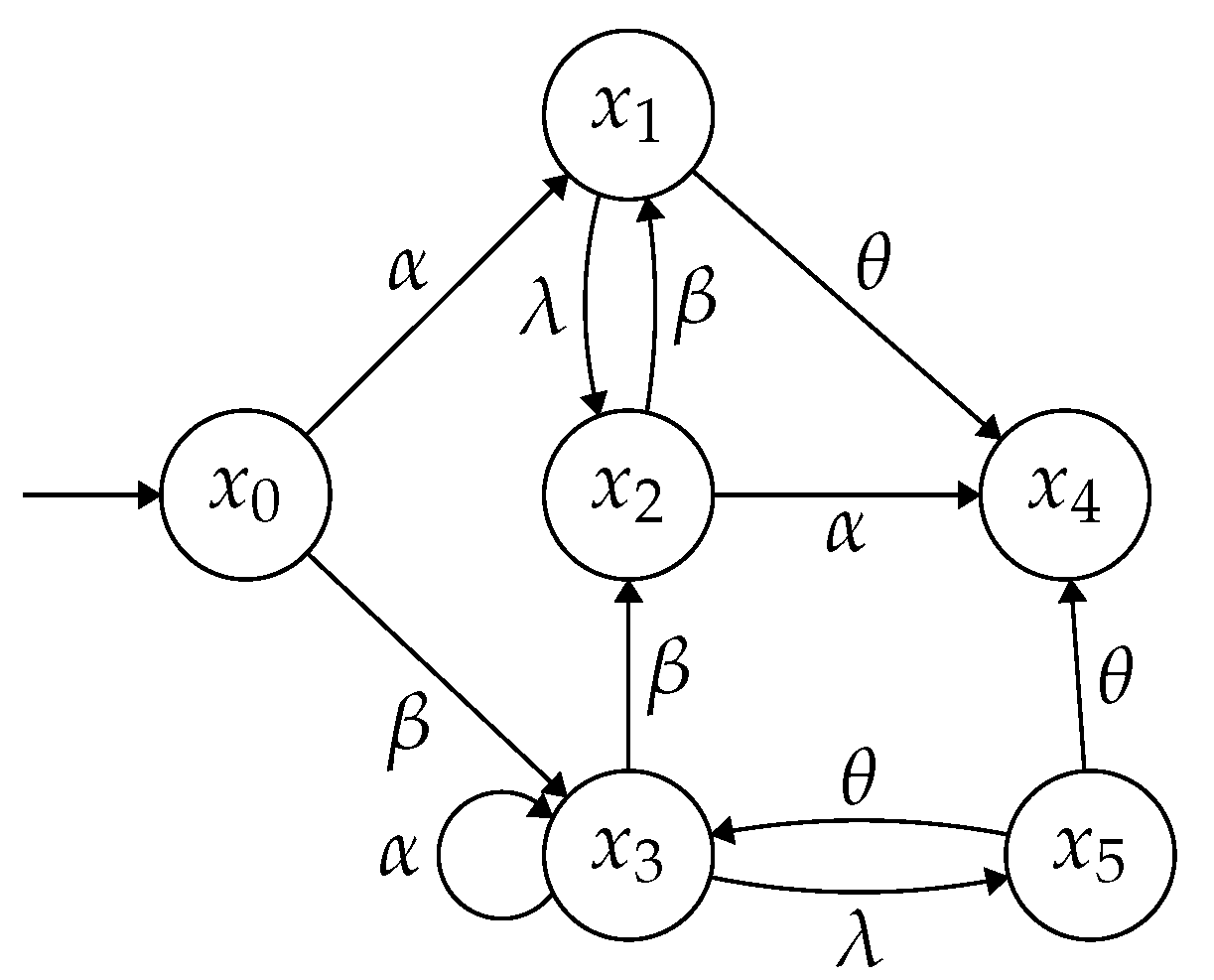

Example 5. We consider the NFA shown in Figure 3. Based on the results in Example 2 by assuming that the observable event set is and the secret is , the system is not critically observable. Suppose that an unsafe observation is generated, in which the state estimate is neither a subset of the critical states nor a subset of the non-critical states. The unsafe state sequence corresponding to ρ is obtained in the critical state estimator shown in Figure 4. By lines 2–6 of Algorithm 2, we calculate the set B illustrated in Table 1 (the contents of columns 1, 2 and 3 record , and , respectively). Then, we compute the maximum degree of the production state sequences in , i.e., and choose the minimum parameter .

We take the input sequence and a random output for an example. The probabilities of the correct states are

with , where in general . Here, we consider .

The probability for generating is

Analogously, for another random input state sequence (e.g., with the maximum security degree), we have probabilities for the correct states

When considering as an input of , the probability of generating is

In other words, if the observation is directly sent, the critical observability violative state can be detected by an intruder due to and . However, by inputting into the designed optimal DPM, a modified state sequence is output. Just by acquiring the sequence , it is difficult for an intruder to backtrack or infer the original sequence , since there exists another random sequence which can also generate with an approximate probability. □