Submitted:

09 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

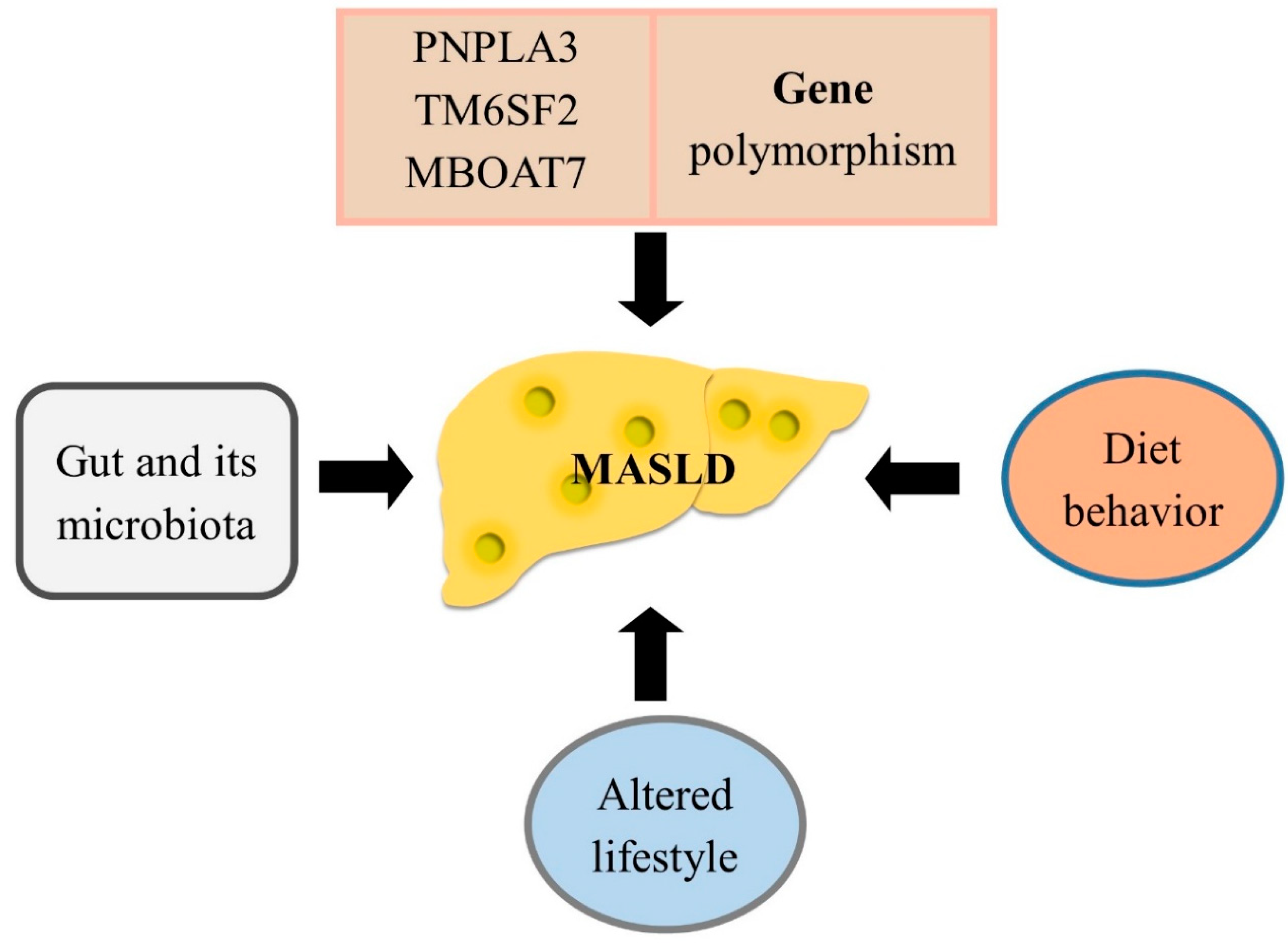

Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease

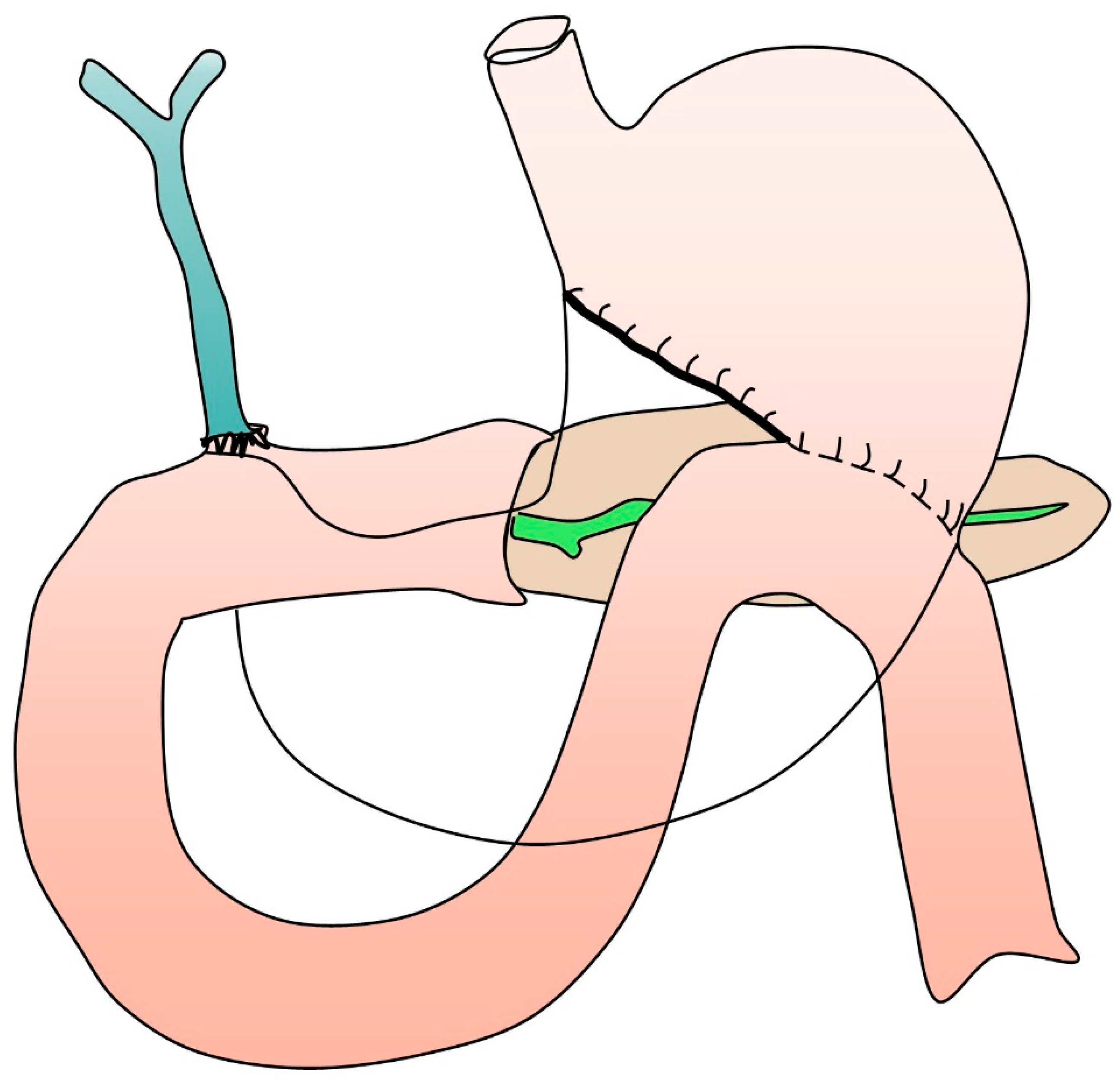

Overview of Pancreaticoduodenectomy

MASLD in Patients After Undergoing Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Conclusion

Conflict of Interest

Funding

Acknowledgments

Authors’ Contributions

References

- Younossi ZM, Kalligeros M, Henry L. Epidemiology of Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Miao L, Targher G, Byrne CD, Cao Y-Y, Zheng M-H. Current status and future trends of the global burden of MASLD. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtare M, Abdi A, Sadeghian AM, Sotoudeheian M, Namazi A, Sikaroudi MK. Investigation about the correlation between the severity of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2023;58:221-7. [CrossRef]

- van Erpecum KJ, Dalekos GN. New horizons in the diagnosis and management of patients with MASLD. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2024;122:1-2.

- Lionis C, Papadakis S, Anastasaki M, Aligizakis E, Anastasiou F, Francque S, et al. Practice Recommendations for the Management of MASLD in Primary Care: Consensus Results. Diseases. 2024;12:180. [CrossRef]

- Hüttner FJ, Fitzmaurice C, Schwarzer G, Seiler CM, Antes G, Büchler MW, et al. Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (pp Whipple) versus pancreaticoduodenectomy (classic Whipple) for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016.

- Han MAT, Yu Q, Tafesh Z, Pyrsopoulos N. Diversity in NAFLD: a review of manifestations of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in different ethnicities globally. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology. 2020;9:71. [CrossRef]

- Yip TCF, Vilar-Gomez E, Petta S, Yilmaz Y, Wong GLH, Adams LA, et al. Geographical similarity and differences in the burden and genetic predisposition of NAFLD. Hepatology. 2023;77:1404-27. [CrossRef]

- Habib S. Team players in the pathogenesis of metabolic dysfunctions-associated steatotic liver disease: The basis of development of pharmacotherapy. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. 2024;15.

- Ha S, Wong VW-S, Zhang X, Yu J. Interplay between gut microbiome, host genetic and epigenetic modifications in MASLD and MASLD-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sun B, Zhuang L. PNPLA3 is one of the bridges between TM6SF2 E167K variant and MASLD. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Seko Y, Yamaguchi K, Shima T, Iwaki M, Takahashi H, Kawanaka M, et al. Clinical Utility of Genetic Variants in PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 to Predict Liver-Related Events in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Liver International. 2024.

- Longo M, Meroni M, Paolini E, Erconi V, Carli F, Fortunato F, et al. TM6SF2/PNPLA3/MBOAT7 loss-of-function genetic variants impact on NAFLD development and progression both in patients and in in vitro models. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2022;13:759-88.

- Wang Z, Xu M, Hu Z, Shrestha UK. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its metabolic risk factors in women of different ages and body mass index. Menopause. 2015;22:667-73.

- Mitra S, De A, Chowdhury A. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Translational gastroenterology and hepatology. 2020;5.

- Gan L, Chitturi S, Farrell GC. Mechanisms and implications of age-related changes in the liver: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the elderly. Current gerontology and geriatrics research. 2011;2011:831536.

- Arun J, Clements RH, Lazenby AJ, Leeth RR, Abrams GA. The prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is greater in morbidly obese men compared to women. Obesity surgery. 2006;16:1351-8.

- Polyzos SA, Goulis DG. Menopause and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Maturitas. 2024:108024.

- Lekakis V, Papatheodoridis GV. Natural history of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2024;122:3-10.

- Israelsen M, Francque S, Tsochatzis EA, Krag A. Steatotic liver disease. The Lancet. 2024;404:1761-78.

- Tacke F, Horn P, Wong VW-S, Ratziu V, Bugianesi E, Francque S, et al. EASL–EASD–EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Journal of Hepatology. 2024.

- Geng Y, Faber KN, de Meijer VE, Blokzijl H, Moshage H. How does hepatic lipid accumulation lead to lipotoxicity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? Hepatology international. 2021;15:21-35.

- Liu Q, Bengmark S, Qu S. The role of hepatic fat accumulation in pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Lipids in health and disease. 2010;9:1-9.

- Fujii H, Kawada N. Inflammation and fibrogenesis in steatohepatitis. Journal of gastroenterology. 2012;47:215-25.

- Mouleeswaran K, Varghese J, Reddy MS. Atlas of Basic Liver Histology for Practicing Clinicians and Pathologists: Springer; 2023.

- Leow W-Q, Chan AW-H, Mendoza PGL, Lo R, Yap K, Kim H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the pathologist’s perspective. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology. 2023;29:S302. [CrossRef]

- Akkız H, Gieseler RK, Canbay A. Liver fibrosis: From basic science towards clinical progress, focusing on the central role of hepatic stellate cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024;25:7873.

- Ahmad W, Ijaz B, Javed FT, Gull S, Kausar H, Sarwar MT, et al. A comparison of four fibrosis indexes in chronic HCV: development of new fibrosis-cirrhosis index (FCI). BMC gastroenterology. 2011;11:1-10.

- Pinzani M, Rosselli M, Zuckermann M. Liver cirrhosis. Best practice & research Clinical gastroenterology. 2011;25:281-90.

- Garrido A, Djouder N. Cirrhosis: a questioned risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. Trends in cancer. 2021;7:29-36. [CrossRef]

- Eslam M, El-Serag HB, Francque S, Sarin SK, Wei L, Bugianesi E, et al. Metabolic (dysfunction)-associated fatty liver disease in individuals of normal weight. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2022;19:638-51.

- Verma MK, Tripathi M, Singh BK. Dietary Determinants of Metabolic Syndrome: Focus on the Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). 2024.

- Liu S, Wang J, Wu S, Niu J, Zheng R, Bie L, et al. The progression and regression of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease are associated with the development of subclinical atherosclerosis: a prospective analysis. Metabolism. 2021;120:154779.

- Chai X-N, Zhou B-Q, Ning N, Pan T, Xu F, He S-H, et al. Effects of lifestyle intervention on adults with metabolic associated fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2023;14:1081096.

- Tan Z, Sun H, Xue T, Gan C, Liu H, Xie Y, et al. Liver fibrosis: therapeutic targets and advances in drug therapy. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2021;9:730176.

- Drebin JA, Strasberg SM. Techniques for biliary and pancreatic reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Pancreatic Cancer: Springer; 2002. p. 171-80.

- Wang M, Cai H, Meng L, Cai Y, Wang X, Li Y, et al. Minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy: a comprehensive review. International Journal of Surgery. 2016;35:139-46.

- Dai R, Turley RS, Blazer DG. Contemporary review of minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy. World journal of gastrointestinal surgery. 2016;8:784.

- Tang G, Zhang L, Xia L, Zhang J, Chen R, Zhou R. Comparison of short-term outcomes of robotic versus open Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials and Propensity-Score-Matched studies. International Journal of Surgery. 2024:10.1097.

- Shamali A, McCrudden R, Bhandari P, Shek F, Barnett E, Bateman A, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for nonampullary duodenal lesions: indications and results. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2016;28:1388-93.

- Jabłońska B, Szmigiel P, Mrowiec S. Pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: Current diagnosis and management. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 2021;13:1880.

- Salvia R, Burelli A, Perri G, Marchegiani G. State-of-the-art surgical treatment of IPMNs. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2021:1-10.

- Chen R, Xiao C, Song S, Zhu L, Zhang T, Liu R. The optimal choice for patients underwent minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis including patient subgroups. Surgical Endoscopy. 2024:1-17.

- Sharifi A, Bakhtiari Z. Complications (Pain intensity, Opioid usage, Bleeding, morbidity and mortality) following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Eurasian Journal of Chemical, Medicinal and Petroleum Research. 2023;2:266-74.

- Vallance AE, Young AL, Macutkiewicz C, Roberts KJ, Smith AM. Calculating the risk of a pancreatic fistula after a pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review. Hpb. 2015;17:1040-8.

- Ke Z-x, Xiong J-x, Hu J, Chen H-y, Li Q, Li Y-q. Risk factors and management of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy: single-center experience. Current medical science. 2019;39:1009-18.

- Guo C, Xie B, Guo D. Does pancreatic duct stent placement lead to decreased postoperative pancreatic fistula rates after pancreaticoduodenectomy? A meta-analysis. International Journal of Surgery. 2022;103:106707. [CrossRef]

- Marchegiani G, Di Gioia A, Giuliani T, Lovo M, Vico E, Cereda M, et al. Delayed gastric emptying after pancreatoduodenectomy: One complication, two different entities. Surgery. 2023;173:1240-7. [CrossRef]

- Simon R. Complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgical Clinics. 2021;101:865-74.

- Eguia E, Aranha GV, Abood G, Godellas C, Kuo PC, Baker MS. Do high-volume centers mitigate complication risk and reduce costs associated with performing pancreaticoduodenectomy in ethnic minorities? The American Journal of Surgery. 2021;222:153-8.

- Panni RZ, Panni UY, Liu J, Williams GA, Fields RC, Sanford DE, et al. Re-defining a high volume center for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hpb. 2021;23:733-8.

- Abdelrahim M, Esmail A, Xu J, Katz TA, Sharma S, Kalashnikova E, et al. Early relapse detection and monitoring disease status in patients with early-stage pancreatic adenocarcinoma using circulating tumor DNA. Journal of Surgery and Research. 2021;4:602-15. [CrossRef]

- Groot VP, Mosier S, Javed AA, Teinor JA, Gemenetzis G, Ding D, et al. Circulating tumor DNA as a clinical test in resected pancreatic cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2019;25:4973-84.

- Hata T, Mizuma M, Motoi F, Ohtsuka H, Nakagawa K, Morikawa T, et al. Prognostic impact of postoperative circulating tumor DNA as a molecular minimal residual disease marker in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing surgical resection. Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences. 2023;30:815-24.

- Yamaguchi T, Uemura K, Murakami Y, Kondo N, Nakagawa N, Okada K, et al. Clinical implications of pre-and postoperative circulating tumor DNA in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2021;28:3135-44. [CrossRef]

- Vigia E, Ramalhete L, Filipe E, Bicho L, Nobre A, Mira P, et al. Machine learning-based model helps to decide which patients may benefit from pancreatoduodenectomy. Onco. 2023;3:175-88.

- Schlanger D, Graur F, Popa C, Moiș E, Al Hajjar N. The role of artificial intelligence in pancreatic surgery: A systematic review. Updates in Surgery. 2022;74:417-29.

- Shen Z, Chen H, Wang W, Xu W, Zhou Y, Weng Y, et al. Machine learning algorithms as early diagnostic tools for pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy and guide drain removal: A retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Surgery. 2022;102:106638.

- Verma A, Balian J, Hadaya J, Premji A, Shimizu T, Donahue T, et al. Machine Learning–based Prediction of Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula Following Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Annals of Surgery. 2024;280:325-31.

- Ashraf Ganjouei A, Romero-Hernandez F, Wang JJ, Casey M, Frye W, Hoffman D, et al. A machine learning approach to predict postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy using only preoperatively known data. Annals of surgical oncology. 2023;30:7738-47.

- Capretti G, Bonifacio C, De Palma C, Nebbia M, Giannitto C, Cancian P, et al. A machine learning risk model based on preoperative computed tomography scan to predict postoperative outcomes after pancreatoduodenectomy. Updates in Surgery. 2022:1-9.

- Kang CM, Lee JH. Pathophysiology after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG. 2015;21:5794.

- Mori T, Ozawa E, Sasaki R, Shimakura A, Takahashi K, Kido Y, et al. Are transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 gene polymorphisms associated with steatohepatitis after pancreaticoduodenectomy? JGH Open. 2024;8:e13113.

- Tanaka N, Horiuchi A, Yokoyama T, Kaneko G, Horigome N, Yamaura T, et al. Clinical characteristics of de novo nonalcoholic fatty liver disease following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Journal of gastroenterology. 2011;46:758-68.

- Kato H, Kamei K, Suto H, Misawa T, Unno M, Nitta H, et al. Incidence and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease after total pancreatectomy: a first multicenter prospective study in Japan. Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences. 2022;29:428-38.

- Nakagawa N, Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Kondo N, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease after pancreatoduodenectomy is closely associated with postoperative pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2014;110:720-6.

- Kato H, Isaji S, Azumi Y, Kishiwada M, Hamada T, Mizuno S, et al. Development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) after pancreaticoduodenectomy: proposal of a postoperative NAFLD scoring system. Journal of hepato-biliary-pancreatic sciences. 2010;17:296-304.

- Huang K, Ma T, Qian T, Bai X, Liang T. Clinical significance and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a Retrospective Cohort Study. HPB. 2024;26:S361-S2.

- Fujii T, Iizawa Y, Kobayashi T, Hayasaki A, Ito T, Murata Y, et al. Radiomics-based prediction of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease following pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery Today. 2024:1-11.

- D’Cruz V, De Zutter A, Van den Broecke M, Ribeiro S, de Carvalho LA, Smeets P, et al. Prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease after pancreatic surgery in a historical Belgian cohort and review of the literature. Acta Gastro-Enterologica Belgica. 2024;87.

- Shibata S, Takahashi Y, Oyama H, Minegishi Y, Tanaka K. Incidence and clinical characteristics of hepatic steatosis following pancreatectomy. The Showa University Journal of Medical Sciences. 2024;36:25-35.

- Izumi H, Yoshii H, Fujino R, Takeo S, Nomura E, Mukai M, et al. Factors contributing to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and fat deposition after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A retrospective analysis. Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery. 2023;7:793-9.

- Fujii Y, Nanashima A, Hiyoshi M, Imamura N, Yano K, Hamada T. Risk factors for development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease after pancreatoduodenectomy. Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery. 2017;1:226-31.

- Yoo D-G, Jung B-H, Hwang S, Kim S-C, Kim K-H, Lee Y-J, et al. Prevalence analysis of de novo hepatic steatosis following pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. Digestive surgery. 2015;31:359-65. [CrossRef]

- Yu H-H, Shan Y-S, Lin P-W. Effect of pancreaticoduodenectomy on the course of hepatic steatosis. World journal of surgery. 2010;34:2122-7.

- Ito Y, Kenmochi T, Shibutani S, Egawa T, Hayashi S, Nagashima A, et al. Evaluation of predictive factors in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease after pancreaticoduodenectomy. The American Surgeon. 2014;80:500-4.

- Sato T, Matsuo Y, Shiga K, Morimoto M, Miyai H, Takeyama H. Factors that predict the occurrence of and recovery from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease after pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery. 2016;160:318-30.

- Hata T, Ishida M, Motoi F, Sakata N, Yoshimatsu G, Naitoh T, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for the development of postoperative hepatic steatosis after total pancreatectomy. Pancreas. 2016;45:362-9. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).