1. Introduction

Genetic breeding is a successful modern technology for increasing productivity and stress resistance of agricultural plants, however, the development and use of highly effective plant protection products (PPPs) remains relevant. Traditional, chemical pesticides have significant drawbacks: toxicity and allergenicity for humans and animals, reduced nutritional value of food products, development of resistance in harmful organisms and pollution of the environment. Biological PPPs based on natural compounds are increasingly attracting attention, since, without these drawbacks, they are often not inferior to chemical preparations in effectiveness.

The range of biopesticides and their application methods are quite diverse. But they all target the interaction between the pathogen and the plant, acting either by increasing the plant’s immunity or by interrupting the pathogen's life cycle. The outcome of this interaction depends on the pathogen, including lifestyle and nutrition strategy: biotrophy, hemi-biotrophy and necrotrophy. In the process of evolution, the host plant has developed hormone-dependent defense mechanisms corresponding to each type of pathogen. Currently, two classical mechanisms are generally recognized: 1) involving salicylic acid (SA) for the host defense response against biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens; 2) involving jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene, which promote the defense response against necrotrophs and hemibiotrophs [

1]. Increasingly, evidence suggests that other hormones (auxins, cytokinins, abscisic acid, gibberellins, brassinosteroids) and signaling molecules, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO), are also involved in the regulation of plant defense responses [

1,

2]. The latter are especially important for the activation of the SA-dependent cascade, leading to the accumulation of ROS, hypersensitivity reaction (HSR), synthesis of phenolic substances and specific protective PR (Pathogeneous Related) proteins [

2,

3].

Chitin and chitosan derivatives are widely used as biological PPPs [

4,

5]. The polymeric carbohydrate chitin is widespread in nature and is a component of the integuments of arthropods (including crustaceans and insects) and fungi. Chitosan is obtained by hydrolysis and deacetylation of chitin. Chitosan-based preparations have a stimulating effect on plant growth and development, and also enhance resistance to abiotic stress [

6,

7]. Chitosan derivatives are also of particular interest as inducers of resistance to fungal, bacterial and viral diseases [

8,

9]. The efficiency of chitosan derivatives can be significantly enhanced by their modification: introduction of functional groups of Schiff bases, halogen atoms (Cl or F), metal nanoparticles, urea groups,

etc. [

9]. A positive protective effect of combining chitosan preparations with other biologically active substances (BAS) and beneficial microorganisms (Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria, PGPB) has been established [

10,

11,

12].

A new chitosan derivative, novochizol, obtained by intramolecular cross-linking of linear chitosan molecules, has great potential. The novochizol molecule has a globular shape, which gives it a number of advantages over chitosan: increased solubility in aqueous solutions, chemical stability and resistance to biodegradation, high penetrating ability and adhesion, as well as the ability to absorb various BAS and slowly release them (

www.novochizol.ch). The latter property is especially important in terms of creating complex preparations with any BAS, regardless of their structural and physical parameters. Novochizol has a growth-stimulating effect when treated with seeds and leaves. Using common wheat,

T. aestivum, as an example, it was shown that this preparation enhanced seed germination, contributed to an increase in root mass and the total mass of plants [

13].

To develop the technology of biological PPPs application it is necessary to study their effect on defense mechanisms and development of the most harmful diseases. The effect of novochizol on mechanisms of wheat resistance against rust diseases has not been studied before. The objective of this work is to conduct a preliminary biochemical analysis of the effect of novochizol on common wheat susceptible to stem rust when it is infected in laboratory conditions with the causative agent of this disease- P. graminis f. sp. tritici (Pgt). At this stage, it was necessary to find the critical points at which the reaction to the pathogen occurs under the influence of novochizol. For this purpose, biochemical tests were used: for antioxidant activity, for the total content of phenols, and for the activity of peroxidase and catalase, the main antioxidant enzymes. This work is the first step for a subsequent, broader analysis of the molecular- genetic and biochemical mechanisms of the effect of novochizol on plant immunity.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The research objects were 10-day-old seedlings of the common wheat variety Novosibirskaya 29 susceptible to stem rust. The plants were grown in vessels with soil, which is recommended for experiments with rust fungi by international protocols [

14].

2.2. Stem Rust Pathogen

To infect the seedlings, we used urediniospores of the West Siberian population

Pgt from the collection of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics of SB RAS. Urediniospores were stored at -70℃ before the experiment and re-cultivated on the susceptible variety of common wheat “Khakasskaya” [

15].

2.3. Novochizol Treatment and Plant Infection

The seedlings were treated with novochizol solutions at concentrations of 0.125, 0.75, 1.5, 2.5%. The solutions were applied to the plants using a sprayer (15 ml/100 plants) four days before infection with Pgt.

A suspension of urediniospores with a concentration of 0.8 mg/ml Novec 7100 [

16] was applied to the seedlings using a sprayer. Control plants were sprayed with bidistilled water. Inoculated plants were incubated for 24 h in a humidified chamber in the dark at a temperature of 15–20 °C to ensure maximum spore germination. Then, the plants were transferred to growth chambers and incubated under 16-hour illumination with phytolamps with an intensity of 10,000 lux at a temperature of 26–28 °C. This temperature is necessary for the formation of appressoria, penetration of the pathogen into the stomata, and the development of infectious hyphae in the intercellular spaces of the plant [

17].

2.4. Evaluation of the Susceptibility Level of Plants to Infection

The infection types of plant response (IT) was determined 12–14 days after inoculation using the modified Stackman scale, where IT “0”, “;”, “1”, “2” were interpreted as resistant (low, L), and “3”, “3+” and “4” – susceptible (high, H) [

18].

2.5. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity of Plant Extracts

Taking into account the previous assessment of the effect of novochizol on the disease development, biochemical analyses were performed on the plants treated with 0.125% novochizol. The material was collected 2, 7, 10, 24, 72, 144, 240 hours after inoculation (hp/in). Leaf pieces were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at – 80 ℃ until analysis. Extracts were obtained using a modified method [

19]. Frozen leaves were ground in cooled sterile mortars. 0.1 g of tissue was placed in cooled Eppendorf tubes and 0.6 ml of cooled (4ºC) 0.2 M K-phosphate buffer pH 7.8 was added. The tubes were thoroughly shaken and centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 rpm at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and stored on ice until analysis. Antioxidant activity (AA) of plant extracts was assessed by their ability to inhibit the reaction of adrenaline autooxidation with its conversion to adrenochrome, according to a modified method [

20]. The reaction mixture was obtained by sequentially adding 0.045 ml of 0.2 M K-phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) and 0.15 ml of 0.1% (5.46 mM) adrenaline hydrochloride solution to 3 ml of 0.2 M Na-carbonate buffer (pH 10.65). The control sample (D1) was mixed, placed in a spectrophotometer SPEKS SSP 705 ("Spectroscopic Systems", Moscow, Russia), and the optical density was measured during 30 sec. at a wavelength of 347 nm (absorption spectrum of adrenochrome). When analyzing plant extract samples, the K-phosphate buffer was replaced with 0.045 ml of the extract (D2). AA was assessed as a percentage of adrenaline autooxidation inhibition using the formula: AA = ((D1-D2)*100)/D1,%.

2.6. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

Total phenolic content (TPC) was estimated using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent [

21]. Frozen leaves were ground in cooled sterile mortars. Samples of 0.02 g of ground tissue were placed in cooled Eppendorf tubes, 2 ml of ice-cold 95% methanol was added in each sample, vortexed and left in the dark for 48 hours at room temperature for extraction. The tubes were centrifuged at 14 500 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was transferred to new tubes. 0.1 ml of each sample was used for the analysis. Standard solutions of gallic acid and 95% methanol for the blank probe were used to construct the calibration curve. Gallic acid solutions were prepared in 95% methanol, the final concentrations were 10, 50, 100, 150, 200, 240 μg/ml. 0.2 ml of 10% (v/v) Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was added to the analyzed samples, mixed on a vortex and after 3-4 min 0.8 ml of 700 mM Na

2CO

3 was added. Immediately after that, the samples were vortexed and left in the dark at room temperature for 2 hours. After 2 hours, the samples were centrifuged as described above. The optical density of the solutions was determined at λ=765 nm using spectrophotometer. TPC was determined from a calibration graph using the regression equation between gallic acid standards and optical density of solutions at λ = 765 nm, and expressed as gallic acid equivalents.

2.7. Evaluation of Enzymatic Activity

The collected plant material was stored until analysis at -80 °C as described above. Samples were ground in cooled mortars, 0.05 g were collected and 0.45 ml of cold PBS buffer (pH 7.4) with 1 mM EDTA was added. The samples were then centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and stored on ice until analysis. The analyses were performed on the same day. The protein level in the samples was estimated using the Bradford protein determination kit (Catalog No: E-BC-K168-S, Elabscience Inc., USA). No sample dilution was required to determine catalase activity. To determine peroxidase activity, the samples were additionally diluted with 0.01 M PBS buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM EDTA with a dilution factor of 1:10. The enzymatic activity of each sample was determined according to the manufacturer's protocols using the Plant Peroxidase Activity (POD) Assay Kit (Catalog No.: E-BC-K227-S) and Catalase Activity (CAT) Assay Kit (Catalog No.: E-BC-K031-M) from Elabscience.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in 3 biological and 2 analytical replicates. Data obtained from each analysis were first evaluated for normality. Data were analyzed using Statistica 12 software (Statsoft, USA). To test for the significant difference between the two samples we used Mann–Whitney U test (

Table 1).

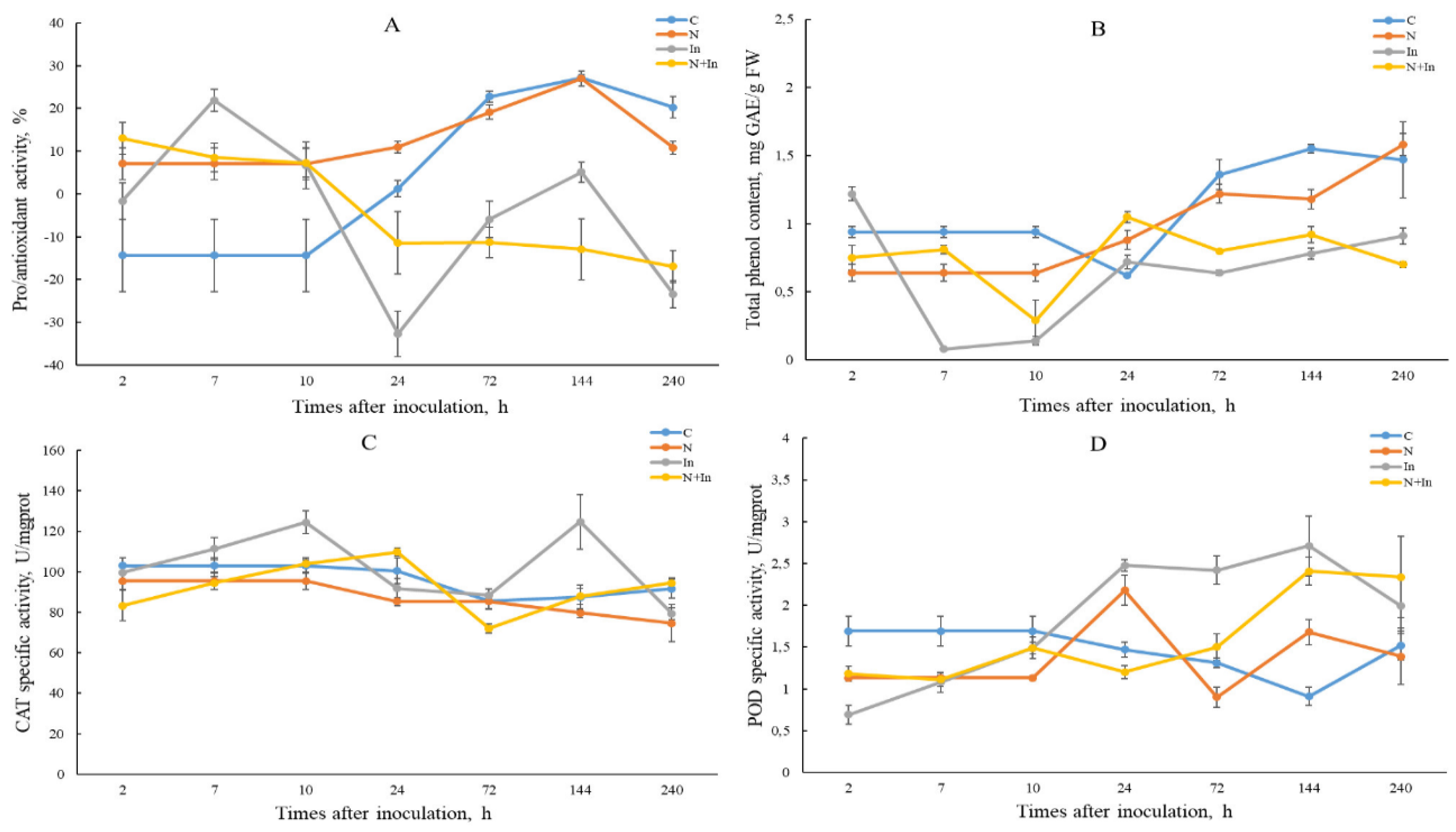

Figure 2 presents the mean values and their standard errors.

3. Results

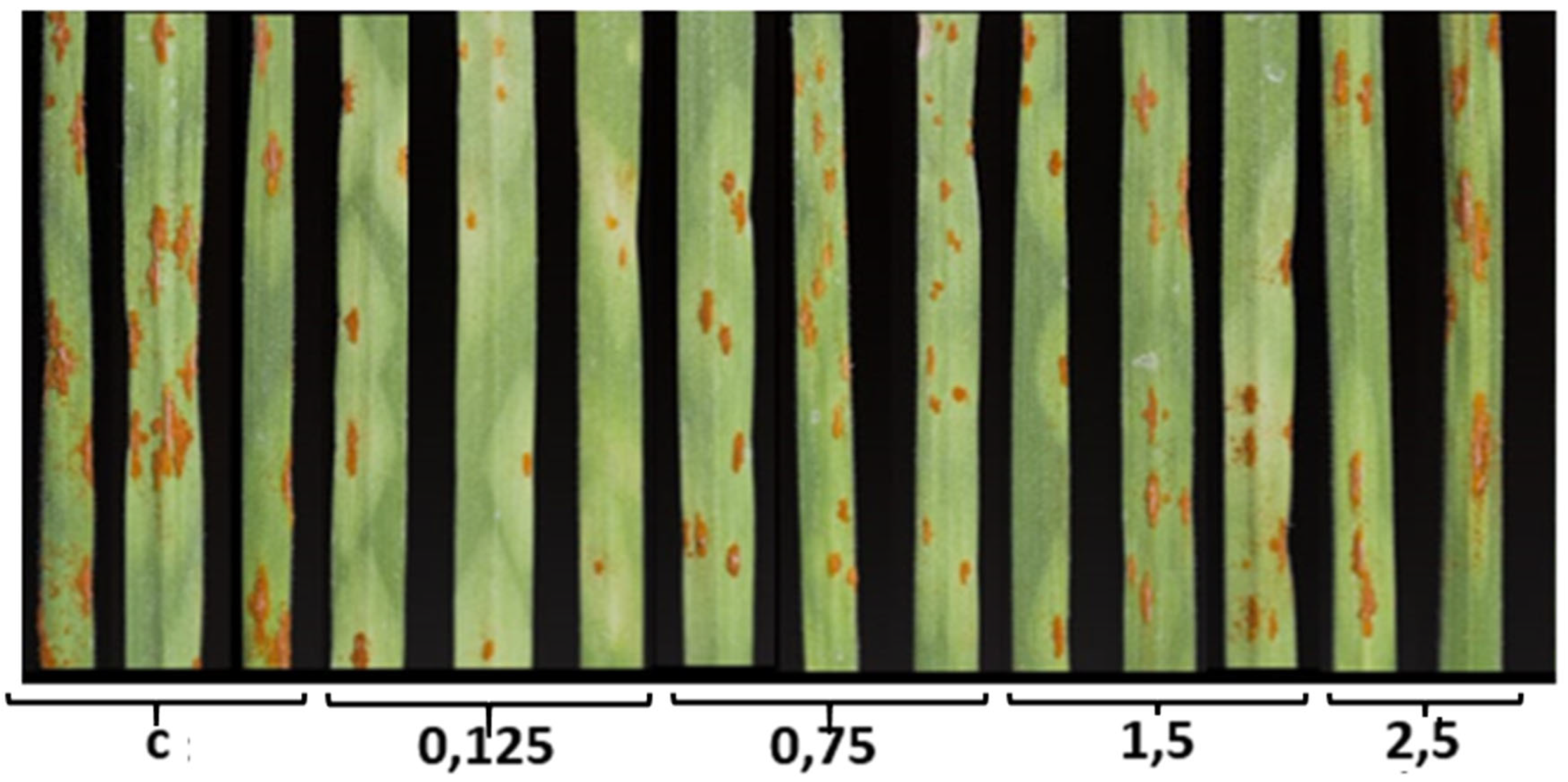

3.1. Visual Assessment of the Novochizol Effect on the Stem Rust Development

At the first stage, the effect of different novochizol concentrations on the disease development was studied on the susceptible variety Novosibirskaya 29. A wide range of drug concentrations was used in the experiments - from 0.125 to 2.5%. Pustules with IT "4" (pustuls of type 4) were formed on the plants treated with water (k). The results showed that novochizol in any concentration affected the development of the disease, which was manifested in a decrease in the density of urediniopustules, a reduction in their size and the appearance of chlorosis zones of various sizes around sporulation (

Figure 1). The minimal IT decrease was noted when using 2.5% solution of novochizol (IT “3”,”3+”). The preparation in concentrations of 0.125, 0.75 and 1.5% induced a stable reaction of plants. It was found that the ratio of resistance symptoms (pustules of type “1” and “2”) to susceptibility symptoms (pustules of type “3”) was maximum when using a 0.125% concentration of novochizol (

Figure 1). This concentration was used for further study of plant defense reactions.

3.2. AA Determination

As described in Methods, AA was assessed by the degree of inhibition of superoxide radical by plant extracts in the adrenaline autooxidation reaction. The AA level of control plants changed from prooxidant activity at 2-10 hp/in to antioxidant activity (72-240 hp/in) (

Figure 2A). We assume that this change was caused by stress due to the limited size of the pot and the root ball. Uninfected novochizol(+) plants showed increased antioxidant activity up to 24 hp/in compared to control, which may be due to the effect of novochizol (

Table 1;

Figure 2A). In infected plants, compared to the control, we observed an increased level of AA at 2-10 hp/in, most pronounced in plants not treated with novochizol at 7 hp/in. After 10 hp/in, the curve shifts towards prooxidant activity, especially in plants pretreated with novochizol (

Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

The changes in pro/antioxidant activity (A), total phenol content (B), catalase activity (C) and peroxidase activity (D) in leaves of common wheat after treatment with 0.125% novochizol and inoculation with urediniospores of the West Siberian population Pgt. Designations: C- control; N- novochizol treatment; In- inoculation; N+In- novochizol treatment and inoculation.

Figure 2.

The changes in pro/antioxidant activity (A), total phenol content (B), catalase activity (C) and peroxidase activity (D) in leaves of common wheat after treatment with 0.125% novochizol and inoculation with urediniospores of the West Siberian population Pgt. Designations: C- control; N- novochizol treatment; In- inoculation; N+In- novochizol treatment and inoculation.

3.3. TPC Determination

TPC was assessed using the Folin-Chocalteu reagent (see Methods). Control plants have on average a higher TPC value compared to other groups, except for the 24 hp/in point (

Figure 2B) (

Table 1;

Figure 2B). Infected novochizol(-) plants demonstrated a lower TPC value at the interval about 5-144 hp/in, compared to infected novochizol(+) plants.

3.4. Estimation of Peroxidase and Catalase Activity

The level of catalase (CAT) activity in uninfected control and novochizol(+) plants remained more or less stable during the experiment (

Figure 2C;

Table 1). In infected novochizol(-) plants, catalase activity increased at 10 hp/in and then decreased to control level at 72 hp/in. After the last point the activity increased again, reaching its highest value at 144 hp/in. Unlike the previous group, no significant changes in the level of catalase activity were observed in the infected novochizol(+) plants compared to control plants, with the exception of a slight decrease in this level below the control at 72 hp/in.

In uninfected novochizol(+) plants at 24 hp/in, a significant increase in peroxidase (POD) activity was observed relative to the control (

Figure 2D;

Table 1). But after 2 days, the activity dropped below the control level. In infected plants, a reduced activity of this enzyme was observed within about 2-10 hp/in. After that the infected novochizol(-) plants demonstrated an increase in peroxidase activity up to 144 hp/in, whereas novochizol(+) plants showed a later increase in this activity after 72 hp/in reaching the level of the previous group at 144 hp/in.

4. Discussion

This paper presents preliminary data on the effect of novochizol on the development of stem rust in common wheat. A concentration- dependent effect of novochizol on the development of stem rust was established (

Figure 1). This is consistent with the results of previous studies on the effect of chitosan doses on defense responses [

6]. In the variant with 0.125% novochizol treatment, the best ratio of pustules by infectious type and condition of leaves was revealed. We used this preparation at the following stages of work.

According to earlier studies, two peaks of ROS formation in response to pathogen infection were revealed in plants. The first peak occurs within minutes or few hours after recognition of pathogen elicitors and was associated with activation of the enzyme NADPH oxidase, which constitutively exists in the membrane, and formation of superoxide anion O2−, which is quickly converted into H

2O

2 by the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD) [

22]. The second peak appears after 3-5 days and is associated with

de novo synthesis of enzymes of the pro/antioxidant system (peroxidases, catalase, oxalate oxidases,

etc.). The pro/antioxidant system maintains an optimal level of ROS in tissues. Catalase breaks down H

2O

2 into water and molecular oxygen; various peroxidases, polyphenol oxidase and ascorbate oxidase utilize ROS in oxidative reactions [

23].

To study the pro/antioxidant activity associated with SOD, we used the adrenaline test (

www.csun.edu/~hcchm001/sodassay.pdf) [

20,

24,

25]. As a result, we observed an increase in AA at 2-10 hp/in, which corresponds to the first peak of ROS accumulation (

Figure 2A). A higher level of AA is characteristic of infected plants without treatment with novochizol, while the level of infected novochizol(+) plants is almost the same as that of uninfected novochizol(+) plants. This may indicate a lower level of stress sensitivity provided by the novochizol treatment. After 10 hp/in we observed a decrease in AA in plants both treated and untreated with novochizol (prooxidant activity). Recently, a histochemical analysis of this plant material was carried out at 96 hp/in and an intensive accumulation of H

2O

2 in the leaves was established [

26]. Apparently, this is associated with the manifestation of the second peak of the oxidative burst. Moreover, in areas of intensive accumulation of H

2O

2, the death of pathogen mycelial cells was observed. A protective role of H

2O

2 against fungal pathogens has also been confirmed by other authors [

27]. Next, we analyzed the activity of enzymes peroxidase and catalase that affect the concentration of this ROS.

The level of catalase activity in infected plants without novochizol treatment demonstrated 2 peaks at 10 and 144 hp/in (

Figure 2C). These peaks probably correspond to the main peaks of ROS accumulation. In infected plants with treatment, this level was generally lower, except for the point 24 hp/in. Along with the data on the AA estimation (see above), this may indicate a higher stress resistance of the latter group. As for peroxidase, its activity level was lower in the same group in the period from 10 to 144 hp/in (

Figure 2D). During the assessment of the effect of complex chitosan preparations on wheat resistance to fungal diseases, the ability of these preparations to inhibit the activity of catalase and peroxidase was shown [

28]. The authors hypothesized that this effect leads to the accumulation of H

2O

2, which contributes to increased expression of pathogen defense genes.

Phenolic substances play an important role in protecting plants from pathogens [

29]. It has been previously shown that the formation of phenols and strengthening of cell walls with lignin after treatment with chitosan were the most typical defense reactions against pathogenic fungi [

6,

8]. Our data shows that treatment with novochizol stimulated more intensive accumulation of phenols than in untreated plants throughout most of the experiment (

Figure 2B). This difference is most noticeable at an early stage up to 10 hp/in.

Thus, we have shown that in plants pre-treated with novochizol at a concentration of 0.125% followed by infection with the stem rust pathogen, changes occur in the antioxidant system, which are accompanied by modulation of the activity of the main enzymes of this system, as well as an increase in the level of phenolic compounds. These changes result in increased plant resistance to this fungal pathogen.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and E.S.; methodology, A.S., E.S. and A.F.; investigation, E.S., A.F. and N.B.; chemical resources, V.F.; supervision, A.S.; writing, A.S., E.S. and A.F.; project administration, A.S.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (RSF project № 23-16-00119).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jones:, J.; Dangl, J. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manjunatha, G.; Niranjan-Raj, S.; Prashanth, G.N.; Deepak, S.; Amruthesh, K.N.; Shetty, H.S. Nitric oxide is involved in chitosan-induced systemic resistance in pearl millet against downy mildew disease. Pest Manag. Sci. 2009, 65, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha, G.; Roopa, K.S.; Prashanth, G.N.; Shetty, H.S. Chitosan enhances disease resistance in pearl millet against downy mildew caused by Sclerospora graminicola and defence-related enzyme activation. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaudo, M. Chitin and chitosan: properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, M.; Cerana, R. Chitosan effects on plant systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzali, L.; Corsi, B.; Forni, C.; Riccioni, L. Chitosan in Agriculture: A new challenge for managing plant disease. In Biological Activities and Application of Marine Polysaccharides, Editor Shalaby E.A., InTech, 2017, 87-96. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahman, M.; Khan, Md.A.R.; Bhowmik, P.; Mahmud, N.U.; Tanveer, M.; Islam, T. Mechanism of plant growth promotion and disease suppression by chitosan biopolymer. Agriculture 2020, 10, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherban, A.B. Chitosan and its derivatives as promising plant protection tools. Vavilov Journal of Genetics and Breeding. 2023, 27, 1010–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluin, F.N.; Hussein, M.Z. Chitosan-Based Agronanochemicals as a Sustainable Alternative in Crop Protection. Molecules 2020, 25, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rkhaila, A.; Chtouki, T.; Erguig, H.; El Haloui, N.; Ounine, K. Chemical proprieties of biopolymers (Chitin/Chitosan) and their synergic effects with endophytic bacillus species: unlimited applications in Agriculture. Molecules 2021, 26, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarullina, L.G.; Burkhanova, G.F.; Tsvetkov, V.O.; Cherepanova, E.A.; Sorokan, A.V.; Zaikina, E.A.; Mardanshin, I.S.; Fatkullin, I.Y.; Maksimov, I.V.; Kalatskaja, J.N.; et al. The effect of chitosan conjugates with hydroxycinnamic acids and Bacillus subtilis bacteria on the activity of protective proteins and resistance of potato plants to Phytophthora infestans. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology 2024, 60, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarullina, L.; Kalatskaja, J.; Tsvetkov, V.; Burkhanova, G.; Yalouskaya, N.; Rybinskaya, K.; Zaikina, E.; Cherepanova, E.; Hileuskaya, K.; Nikalaichuk, V. The influence of chitosan derivatives in combination with Bacillus subtilis bacteria on the development of systemic resistance in potato plants with viral infection and drought. Plants 2024, 13, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplyakova, O.I.; Fomenko, V.V.; Salakhutdinov, N.F.; Vlasenko, N.G. Novochizol™ seed treatment: effects on germination, growth and development in soft spring wheat. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res. 2022, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldeab, G.; Hailu, E.; Bacha, N. Protocols for race analysis of wheat stem rust (Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici). Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research, Ambo Plant Protection Research Center, Ethiopia, 2017. Available online: https://bgri.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Ambo-Manual-revised-2019FINAL.pdf.

- Rsaliyev, A.S.; Rsaliyev, Sh.S. Principal approaches and achievements in studying race composition of wheat stem rust. Vavilov Journal of Genetics and Breeding 2018, 22, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, C.K.; Thach, T.; Hovmøller, M.S. Evaluation of spray and point ino-culation methods for the phenotyping of Puccinia striiformis on wheat. Plant Disease 2016, 100, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelfs, A.P.; Singh, R.P.; Saari, E.E. Rust diseases of wheat: concepts and methods of disease management. Cimmyt, Mexico DF, Mexico. 1992, 81.

- Roelfs, A.P; Martens, J.W.M. An international system of nomenclature for Puccinia graminis f.sp. tritici. Phytopathology 1988, 78, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkar, R. Plant stress tolerance. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 639, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabinina, E.E.; Zotova, E.N.; Vetrova, N.I.; Ponomareva, T.N.; Ilyushina, A. New approach to assessing the antioxidant activity of plant raw materials in studying the process of adrenaline autooxidation. Chemistry of plant raw materials 2011, 3, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Nature protocols 2007, 2, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boller, T.; Keen, N.T. Perception and transduction of elisitor signals in host-pathogen interactions. In Mechanisms of Resistance to Plant Diseases. Eds. A.J. Slusarenko, R.S.S. Frazer, L.S. van Loon, Kluewer Ac. Publ, the Netherlands, 2000, 189–230.

- Maksimov, I.V.; Cherepanova, E.A. Pro-/antioxidant system and plant resistance to pathogens. Advances in modern biology 2006, 126, 250–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kazlou, A.Y. Determination of superoxide dismutase activity. [CrossRef]

- Sirota, T.V. Method for determining the antioxidant activity of superoxide dismutase and chemical compounds. Patent №2144674 (Russia). 20.01.2000.

- Shcherban, A.V.; Skolotneva, E.S.; Fedyaeva, A.V.; Fomenko, V.V. Cyto-physiological manifestations of protective reactions of wheat against stem rust, induced by the biofungicide Novochizol. Vavilov Journal of Genetics and Breeding, 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, N.P.; Mehrabi, R.; Lütken, H.; Haldrup, A.; Kema, G.H.J.; Collinge, D.B.; Jørgensen, H.J.L. Role of hydrogen peroxide during the interaction between the hemibiotrophic fungal pathogen Septoria tritici and wheat. New Phytologist 2007, 174, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, E.V.; Domnina, N.S.; Sokornova, S.V.; Kovalenko, N.M.; Tyuterev, S.L. Innovative hybrid plant immunomodulators based on chitosan and bioactive antioxidants and prooxidants. Agricultural Biology 2021, 56, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caverzan, A.; Casassola, A.; Brammer, S.P. Antioxidant responses of wheat plants under stress. Genet Mol Biol. 2016, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).