Submitted:

08 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

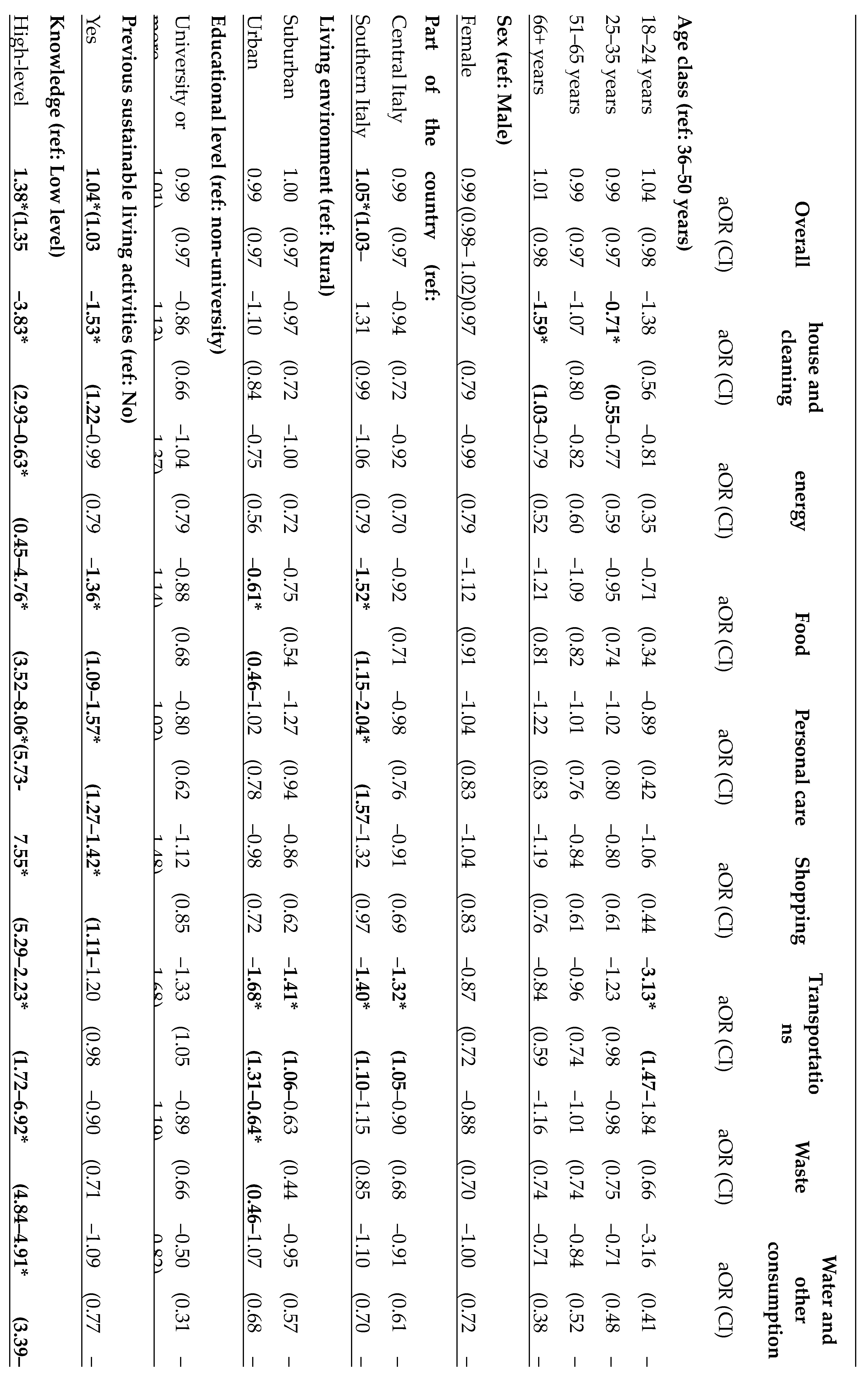

Education and knowledge are essential for fostering sustainable living, that will help protect our planet, promote health and socio-economic development. This study investigated sustainable living knowledge and behaviours among the Italian general population. A 40-item questionnaire was created to assess knowledge, awareness and attitudes in 8 domains: house, energy, food, personal care, shopping, transportation, waste, water and other consumption. The questionnaire was distributed online between January and June 2023. A multiple logistic regression model was performed to assess the relationship between all the variables surveyed. Among the 420 people participated (66% female, median age of 39 years), 76% had a higher-level education degree, and 72% had never participated in a sustainability initiative. Knowledge about sustainability was lower in the domains of shopping (70.6%) and transportation (85.0%). The fewest behaviours acted/products used were found in the domains of personal care (31.3%) and transportation (47.8%). Positive associations were found between the use/adoption of sustainable items and knowledge about sustainability (aOR: 1.38, CI: 1.35–1.41), and previous inherent educational activities (aOR: 1.04, CI: 1.03–1.06). Age, region of residence and urbanization context were factors that discontinuously influenced the implementation of the considered items for transportation and food. Improvements are needed to close the gap between knowledge and action, especially in the domain of personal care. A better understanding of the factors that play a role in non-use of transportation will help to develop measures to promote sustainability and societal wellbeing.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Questionnaire

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

3.2. Knowledge About a Sustainable Living /Sustainability Perception

3.3. Use/attitude Towards Sustainable Living

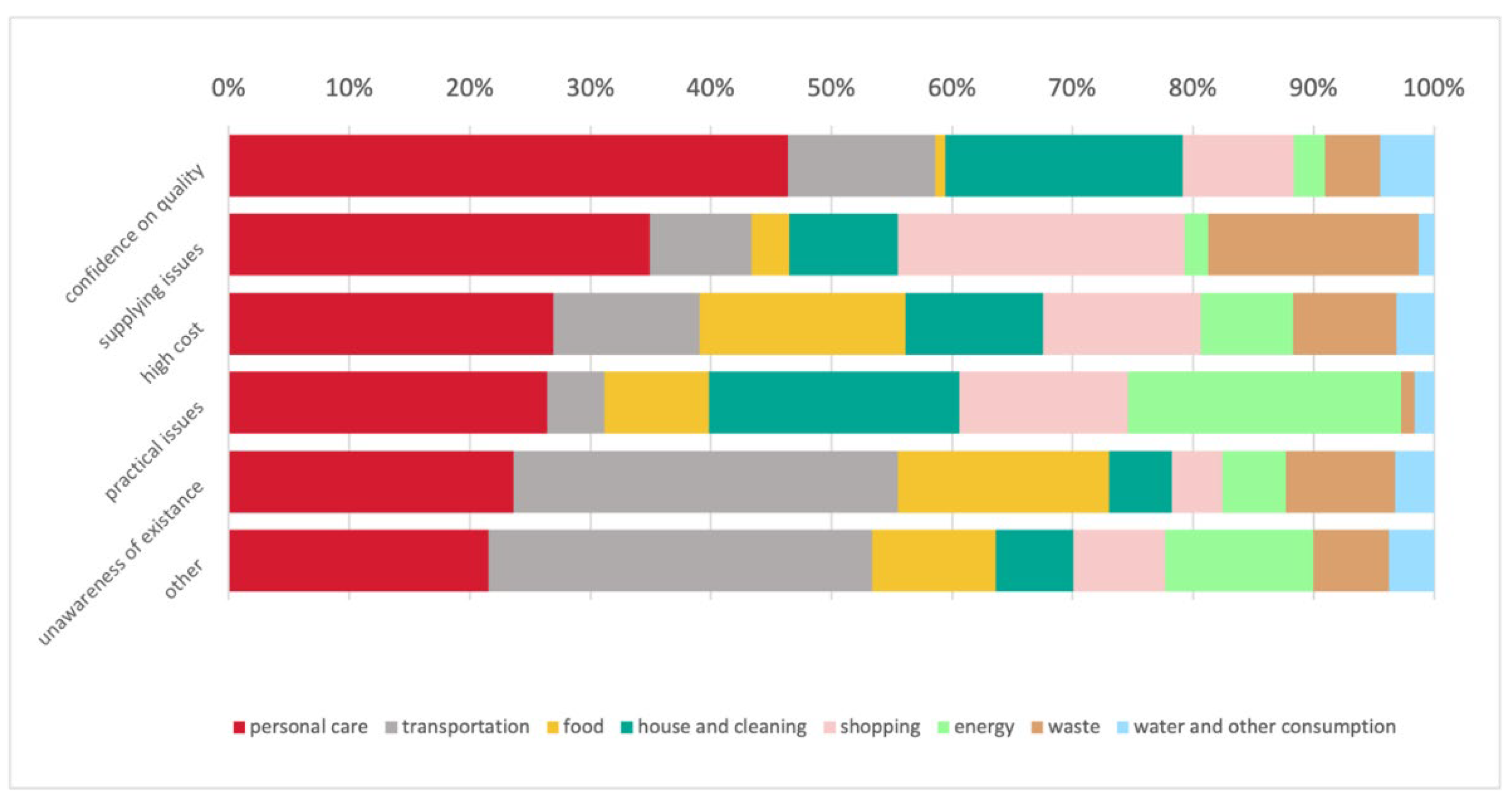

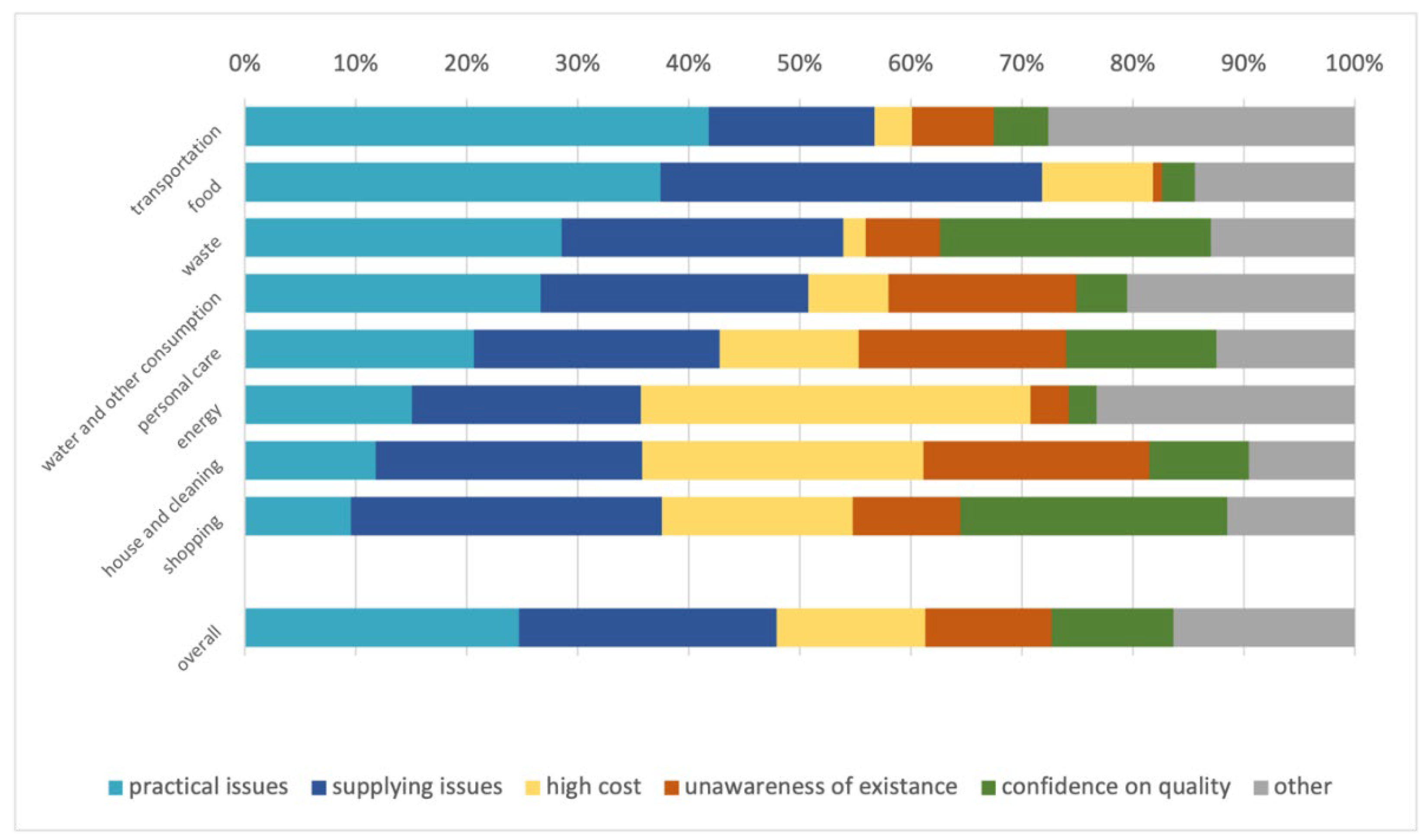

3.4. Reasons for Non-Use or Non-Adoption

3.5. Sources of Information for a Sustainable Living

3.6. Relationship Between Attitudes Towards Sustainable Devices, Behaviours, and Participant Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Barriers to the Use of Products or Adoption of Sustainable Behaviours

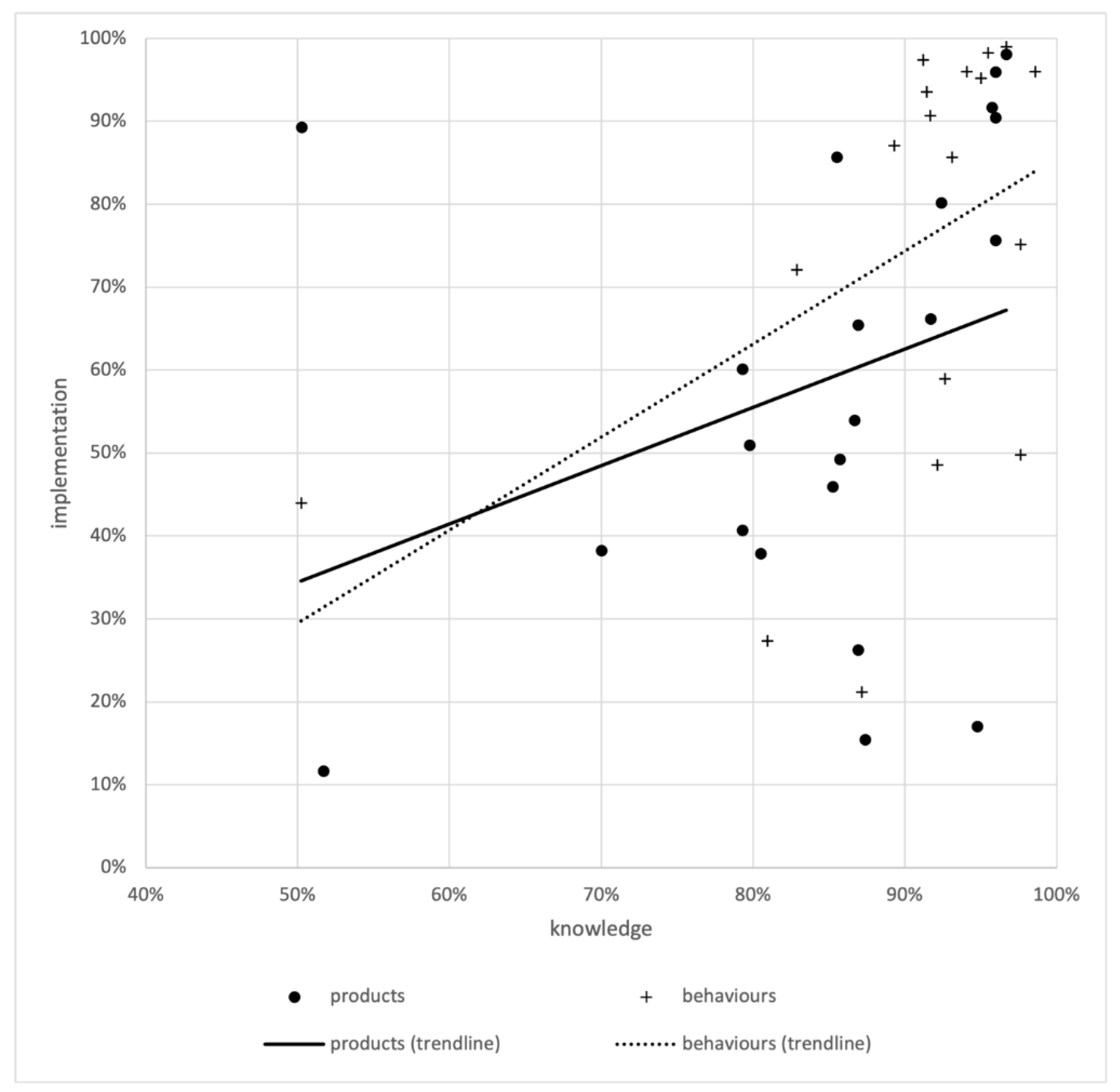

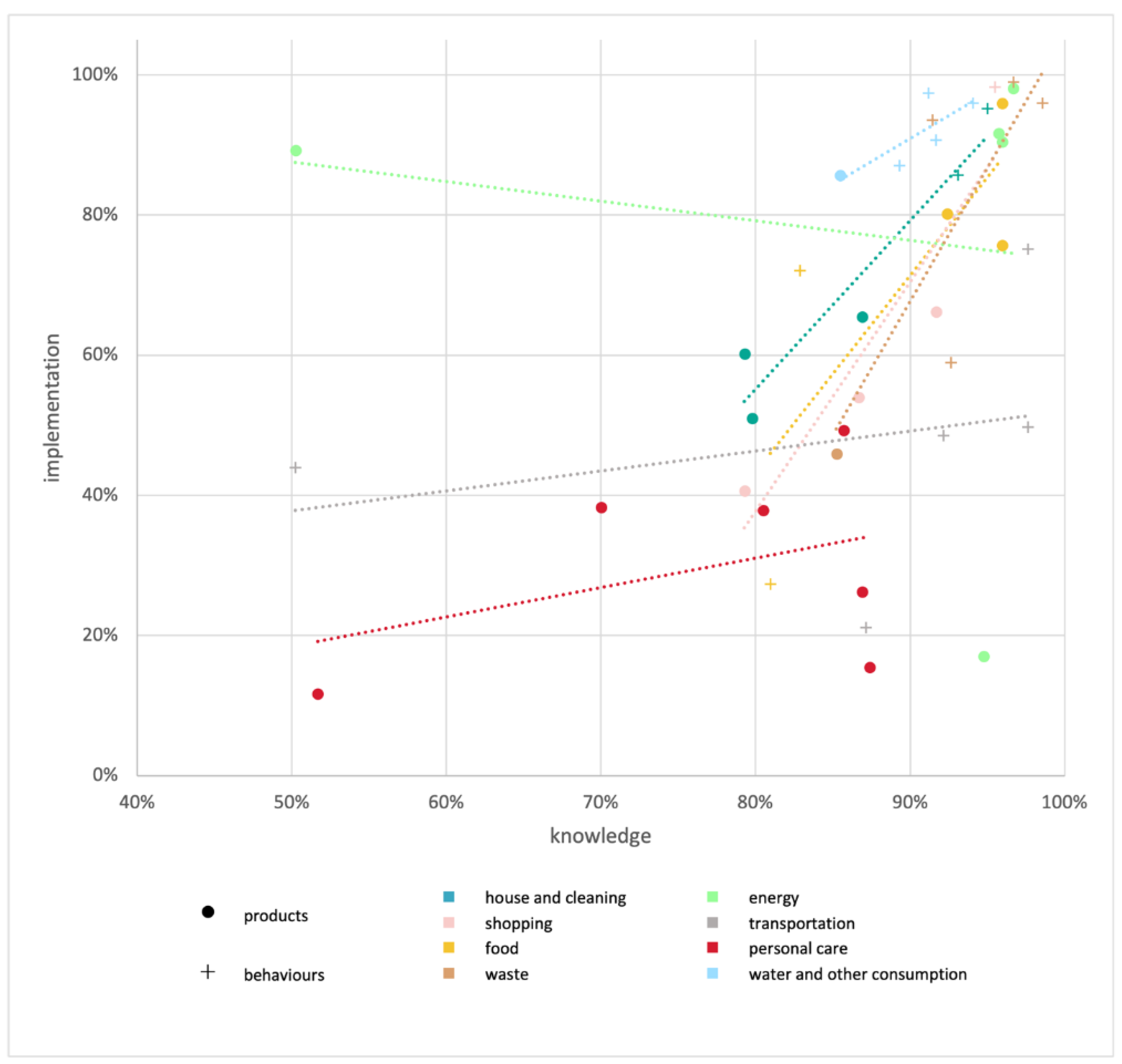

4.2. Gaps Between Knowledge and Use

4.3. Our Results in a Broader Scenario

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research [Internet]. Addison Wesley Publishing Company. 1975. Available from: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/f&a1975.html.

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process [Internet]. 1991, 50, 179–211. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/074959789190020T?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Eur J Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO What you need to know about education for sustainable development [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.unesco.org/en/education/sustainable-development/need-know.

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2015. Goal 4 - Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4.

- Smaniotto, C.; Battistella, C.; Brunelli, L.; Ruscio, E.; Agodi, A.; Auxilia, F.; et al. Sustainable development goals and 2030 agenda: Awareness, knowledge and attitudes in nine Italian universities, 2019. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smaniotto, C.; Brunelli, L.; Miotto, E.; Del Pin, M.; Ruscio, E.; Parpinel, M. Sustainable Development Goals and 2030 Agenda—Survey on Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes of Italian Teachers of Public Mandatory Schools, 2021. Sustain. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto, C.; Saramin, A.; Brunelli, L.; Parpinel, M. Insights and Next Challenges for the Italian Educational System to Teach Sustainability in a Global Context. Sustain. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Sustainable lifestyles [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/sustainable-lifestyles.

- United Nations Environment Programme. Why Sustainable lifestyles matter [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/sustainable-lifestyles/why-sustainable-lifestyles.

- Enel Green Power. Consumo sostenibile: le persone scelgono l’ambiente [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.enelgreenpower.com/it/learning-hub/transizione-energetica/trend-consumo-sostenibile.

- Lifegate. Come l’innovazione ci aiuta a costruire un futuro sostenibile [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.lifegate.it/trend/osservatorio-2021.

- Johns Hopkins University. Sustainable Living Guide [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://hub.jhu.edu/2021/01/08/sustainable-living-guide.

- EUROSTAT. NUTS - NOMENCLATURE OF TERRITORIAL UNITS FOR STATISTICS [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/background.

- EUSURVEY - privacy statement [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eusurvey/home/privacystatement.

- Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. Registro Nazionale delle Associazioni di Promozione Sociale [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.lavoro.gov.it/temi-e-priorita/Terzo-settore-e-responsabilita-sociale-imprese/focus-on/Associazionismo-sociale/Pagine/Registro-nazionale-delle-associazioni-di-promozione-sociale.aspx.

- Globescan. Healthy & Sustainable Living - a global consumer insight project - Highlights Report 2019 [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://globescan.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Healthy_Sustainable_Living_2019_GlobeScan_Highlights.pdf.

- GlobeScan. Healthy & Sustainable Living - 2022 Highlights Report. 2022. Available from: https://globescan.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/GlobeScan_Healthy_and_Sustainable_Living_Highlights_Report_2022.pdf.

- Rural Energy Community Advisory Hub. Empowering Municipalities to Develop and Support Rural Energy Communities [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://rural-energy-community-hub.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-11/Empowering Municipalities to Develop and Support Rural ECs.pdf.

- European Union. Grover: Reducing e-waste by renting out electronic devices [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/en/good-practices/grover-reducing-e-waste-renting-out-electronic-devices.

- European Commission. A new Circular Economy Action Plan For a cleaner and more competitive Europe [Internet]. Brussels, 11.3.2020 COM(2020) 98 Final. 2020. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:9903b325-6388-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1.0017.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

- Italian National Institute of Statistics. demo - demografia in cifre (ISTAT) [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://demo.istat.it/app/?i=POS&l=it.

- UNIMPRESA - Unione Nazionale di Imprese LAVORO: UNIMPRESA, SMART WORKING IN 26 CONTRATTI NAZIONALI E 177 ACCORDI AZIENDALI. Osservatorio lavoro agile al Ministero del Lavoro [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.unimpresa.it/lavoro-unimpresa-smart-working-in-26-contratti-nazionali-e-177-accordi-aziendali/53074.

- European Parliament. Consolidated text: Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 on the energy performance of buildings (recast) [Internet]. 2021. Available from: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2010/31/2021-01-01.

- Ministero dello sviluppo economico. Decreto interministeriale 26 giugno 2015 - Applicazione delle metodologie di calcolo delle prestazioni energetiche e definizione delle prescrizioni e dei requisiti minimi degli edifici [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.mimit.gov.it/index.php/it/normativa/decreti-interministeriali/decreto-interministeriale-26-giugno-2015-applicazione-delle-metodologie-di-calcolo-delle-prestazioni-energetiche-e-definizione-delle-prescrizioni-e-dei-requisiti-minimi-degli-edific.

- Impreseedili. Survey Ufficio Studi Gabetti e Abaco Team. 2021. Edilizia residenziale: Gabetti analizza lo stato del patrimonio italiano. Available from: https://www.impresedilinews.it/gabetti-abaco-team-survey-patrimonio-edilizio-residenziale/.

- Istituto nazionale per l’analisi delle politiche pubbliche. Indagine PIACC - Le competenze dei 16-65enni: il gap Italia nel confronto internazionale. 2023. Available from: https://www.inapp.gov.it/piaac/dati-e-risultati/highlights-ciclo-i/le-competenze-dei-16-65enni-il-gap-italia-nel-confronto-internazionale#:~:text=Gli adulti italiani (16-65,performance (Livello 1 o inferiore.

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Understanding the Sustainable Lifestyle. J Consum Res [Internet]. 2010, 36, 715–34. Available from: https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8475T9J.

- Triantafyllidou, E.; Zabaniotou, A. From Theory to Praxis: ‘Go Sustainable Living’ Survey for Exploring Individuals Consciousness Level of Decision-Making and Action-Taking in Daily Life Towards a Green Citizenship. Circ Econ Sustain. 2022, 2, 113–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cmyk, P.; Nero, B. Progettiamo insieme la Strategia Regionale per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile del Friuli Venezia Giulia REPORT FINALI DELLE CONSULTAZIONI PUBBLICHE [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.regione.fvg.it/rafvg/export/sites/default/RAFVG/ambiente-territorio/tutela-ambiente-gestione-risorse-naturali/FOGLIA208/allegati/Report_finali_consultazione_pubblica.pdf.

- Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia. Strategia Regionale per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile - Questionario [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://agenda2030.fvg.it/questionario.

- Salas-Zapata, W.A.; Ríos-Osorio, L.A.; Cardona-Arias, J.A. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Sustainability: Systematic Review 1990-2016. Vol. 20, Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability. De Gruyter Open Ltd; 2018. p. 46–63.

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf.

- European Investment Bank. The EIB Climate Survey - CITIZENS CALL FOR GREEN RECOVERY, Fourth edition 2021-2022 [Internet]. 2022. 82 p. Available from: https://www.eib.org/en/publications/the-eib-climate-survey-2021-2022.

- Centro Italiano per l’Apprendimento Permanente. FROM ZERO TO HERO: Wise Energy Use Volunteering Scheme for Youngster [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.ciape.it/ciape/en/2019/03/06/from-zero-to-hero-refuse-reuse-reduce-2.

- GlobeScan. Healthy & Sustainable Living - Global Consumer Insights - 2021 Highlights Report. 2021. Available from: https://globescan.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/GlobeScan-HSL-Highlights-Report-2021.pdf.

- GlobeScan. CONSUMERS WILL NOT SAVE THE WORLD: WHY NOW IS THE TIME FOR A RESET, GlobeScan Healthy & Sustainable Living Report 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://globescan.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/GlobeScan_Healthy_and_Sustainable_Living_Highlights_Report_2023.pdf.

- United Nations Environment Programme. The One Planet Network. 2018. Available from: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org.

- SUSTAINABLE LIFESTYLES options & opportunities Take actions together to minimize footprints and maximize impacts. 2018.

- Apel M, Elliott C, Glenn E, Prichard J, Rashash D, Simon D, et al. Sustainable Living Handbook : A Citizen’s Guide to Thoughtful Action [Internet]. Oregon. 2011. Available from: https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/technical_reports/s7526c86z?locale=en.

- Haan, M.; Konijn, E.A.; Burgers, C.; Eden, A.; Brugman, B.C.; Verheggen, P.P. Identifying Sustainable Population Segments Using a Multi-Domain Questionnaire: A Five Factor Sustainability Scale. Soc Mar Q. 2018, 24, 264–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Digital Education Action Plan 2021-2027 Resetting education and training for the digital age [Internet]. Vol. 2, COM(2020) 624 final. Brussels. 2020. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0624.

| Variable | Modality | % (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Class 18–24 | 2 % (7) |

| Class 25–35 | 39 % (162) | |

| Class 36–50 | 25 % (107) | |

| Class 51–65 | 26 % (108) | |

| Class 66 + | 9 % (36) | |

| Sex | Male | 33 % (139) |

| Female | 66 % (279) | |

| Non-binary | < 1 % (2) | |

| Place of Residence |

Northern Italy | 61 % (256) |

| Central Italy | 21 % (87) | |

| Southern Italy | 18 % (77) | |

| Living environment |

Rural | 19 % (78) |

| Suburban | 24 % (100) | |

| Urban | 58 % (242) | |

| Education | Elementary school | < 1 % (2) |

| Secondary school | 2 % (10) | |

| High school diploma | 19 % (81) | |

| Non-university higher education degree | 1 % (6) | |

| University degree | 37 % (156) | |

| Post-graduate qualification | 39 % (165) | |

| Previous SL | No | 72 % (301) |

| activities | Yes | 28 % (119) |

| Profession | Health | 45 % (190) |

| Services – Third sector | 12 % (52) | |

| Public administration | 8 % (34) | |

| Industry | 7 % (31) | |

| Teaching | 6 % (27) | |

| Economy | 4 % (15) | |

| Commerce | 4 % (15) | |

| Unemployed – Unemployable | 4 % (15) | |

| Student | 3 % (13) | |

| Telecommunications – Media | 2 % (8) | |

| Crafts | 1 % (6) | |

| Law | 1 % (6) | |

| Agriculture | 1 % (5) | |

| Politics | < 1 % (2) | |

| Armed forces | < 1 % (1) |

| Item | % respondents with high sustainability perception (N) | % respondents who used device/adopted behaviour (N) |

|---|---|---|

| N = 16 800 | N = 16 473 | |

| House and cleaning | ||

| ecological detergents and cleaners | 86.9 % (365) | 65.5 % (275) |

| cleaning towels made with natural ingredients | 79.8 % (335) | 51.0 % (214) |

| hang wet laundry to dry instead of using a dryer | 93.1 % (391) | 85.7 % (360) |

| wash only full loads of laundry and use cold water | 95.0 % (399) | 95.2 % (400) |

| baking and food storage paper reusable or biodegradable | 79.3 % (333) | 60.2 % (253) |

| Energy | ||

| LED light bulbs | 96.7 % (406) | 98.1 % (412) |

| photovoltaic panels | 94.8 % (398) | 17.1 % (72) |

| multi-plug adapters | 50.2 % (211) | 89.3 % (375) |

| changeable thermostat settings | 95.7 % (402) | 91.7 % (385) |

| more energy-efficient household appliances | 96.0 % (403) | 90.5 % (380) |

| Food | ||

| grow your own food and herbs | 81.0 % (340) | 27.4 % (115) |

| reduce your consumption of meat and dairy products (substituting with white meat, fish, vegetable proteins) | 82.9 % (348) | 72.1 % (303) |

| buy organic and locally produced food | 92.4 % (388) | 80.2 % (337) |

| prefer seasonal products | 96.0 % (403) | 96.0 % (403) |

| use reusable, package-free or bulk-packaged products | 96.0 % (403) | 75.7 % (318) |

| Personal care | ||

| biodegradable cotton balls, cotton swabs, toothbrushes, razors |

85.7 % (360) | 49.3 % (207) |

| bars of soap, shampoo, conditioner, shower gel | 70.0 % (294) | 38.3 % (161) |

| powder/tablets of toothpaste and mouthwash | 51.7 % (217) | 11.7 % (49) |

| microplastic-free cosmetics | 80.5 % (338) | 37.9 % (159) |

| washable/reusable or biodegradable/compostable period products | 86.9 % (365) | 26.3 % (74) |

| washable nappies for infants | 87.4 % (367) | 15.5 % (36) |

| Shopping | ||

| second hand clothes | 79.3 % (333) | 40.7 % (171) |

| durable clothing and ethically and transparently made products | 91.7 % (385) | 66.2 % (278) |

| garments made from organic or rapidly renewable textiles | 86.7% (364) | 54.0 % (227) |

| reusable shopping and grocery bags | 95.5 % (401) | 98.3 % (413) |

| Transportation | ||

| public transportation | 97.6 % (410) | 49.8 % (209) |

| telecommuting and telemeeting platforms to reduce trips | 92.1 % (387) | 48.6 % (204) |

| bicycle or walk trips | 97.6 % (410) | 75.2 % (316) |

| carsharing/carpooling | 87.1 % (366) | 21.2 % (89) |

| offset carbon emissions from air travel with a donated carbon tax | 50.2 % (211) | 44.0 % (185) |

| Waste | ||

| donation/sale of clothing and items instead of disposing them | 91.4 % (384) | 93.6 % (393) |

| separate waste collection according to the regulations of your municipality | 96.7 % (406) | 99.0 % (416) |

| production of compost for wet waste | 92.6 % (389) | 59.0 % (248) |

| disposing of hazardous waste at authorised collection points (ecological islands/waste collection points/containers for expired drugs and used batteries) | 98.6 % (414) | 96.0 % (403) |

| purchase/sale of reconditioned electronic equipment | 85.2 % (358) | 46.0 % (193) |

| Water and other consumption | ||

| turn off the tap when you wash your hands and face, brush your teeth and shave | 94.0 % (395) | 96.0 % (403) |

| use the shower instead of taking a bath in the tub | 91.2 % (383) | 97.4 % (409) |

| use of mixers to regulate the flow of water | 85.5 % (359) | 85.7 % (360) |

| internal design to use natural sunlight during the day instead of lamps and overhead lighting | 91.7 % (385) | 90.7 % (381) |

| solutions/measures to turn off lights and LED appliances when not in use or not needed | 89.3 % (375) | 87.1 % (366) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).