1. Introduction

The increasing complexity of global public health challenges necessitates innovative and collaborative approaches that go beyond institutional and national boundaries. Inter-institutional cooperation (IIC) has become a vital mechanism for coordinating efforts in science, technology, and innovation in health (ST&IH), promoting collaboration among governments, non-state actors, and international organizations to tackle urgent health is-sues [

1,

2]. These IIC aim to optimize resource use, improve knowledge sharing, and drive innovation in health systems. However, challenges such as fragmented initiatives, misaligned policies, and inadequate coordination persist, limiting the impact of these efforts and exacerbating health disparities [

3].

The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the urgent need for robust governance models to address these challenges effectively. It exposed significant weaknesses in instruments for coordination and communication across various sectors, hindering the global response to health emergencies. The prioritization of national interests over collective action revealed the limitations of traditional collaboration strategies, such as sectoral aggregation and mutual consultations, in managing complex health crises [

1]. As noted by Brown and Susskind [

4], many public health tasks, especially those related to infectious disease control, should be considered global public goods requiring effective international cooperation to achieve optimal outcomes [

2]. The crisis underscored the necessity for structured governance frameworks to manage interinstitutional cooperation better and coordinate responses to future health challenges.

In this context, integrating interinstitutional cooperation (IIC) with the principles of global health diplomacy (GHD) has gained prominence as a strategy to enhance international collaboration, strengthen health systems, and promote sustainable and equitable health outcomes. GHD bridges health policy with international relations, law, and eco-nomic management, aiming to align health objectives with broader social and political goals [

3]. While some progress has been made through GHD, significant obstacles remain, including insufficient global governance structures, resource limitations, and inconsistent state-level commitment. Addressing these challenges requires innovative governance approaches that integrate diverse stakeholders and line up their efforts toward shared health goals.[

3]

The overall objective of this study is to propose a governance model for IIC that are performed by platforms (IICP) dedicated to ST&IH collaboration, which contributes to im-proving the performance of cooperation activities primarily among public health institutions and other stakeholders. To attend that it proposes CoopGovern, a governance model designed to enhance the sustainability and effectiveness of IICPs in ST&IH. CoopGovern seeks to overcome existing limitations by providing a comprehensive governance framework comprising principles, guidelines, and key performance indicators tailored to the needs of collaborative health initiatives.

Developed based on established practices and critical success factors identified in different contexts, the model targets to improve coordination, optimize resource sharing, and stimulate innovation within health systems. It is structured to generate public value and facilitate the integration of strengths across sectors, contributing to more resilient and equitable health systems.

The adaptableness of CoopGovern confirms that it can evolve continuously in response to evolving conditions and health challenges. Its flexible structure supports the implementation of innovative and sustainable public health policies, seeking to create long-term im-pact and advance global health resilience. By emphasizing sustainability, CoopGovern ensures that cooperative actions impact to enduring public health objectives, ultimately enhancing the capacity of health systems to address future crises.

This study is guided by the following central question: “What elements should constitute a governance model for IICP in ST&IH, and how should its configuration be de-signed to guide performance improvement actions in IICP activities in ST&IH”?

This work contributes to the literature on interinstitutional cooperation in health (IICH) by offering a practical governance model that tackles existing gaps and supports the improvement of global health initiatives.

In the following sections, this study will present the principles and governance guidelines underpinning the CoopGovern conceptual framework, explore its alignment with collaborative governance theories, and discuss its potential to guide sustainable public policy implementation.

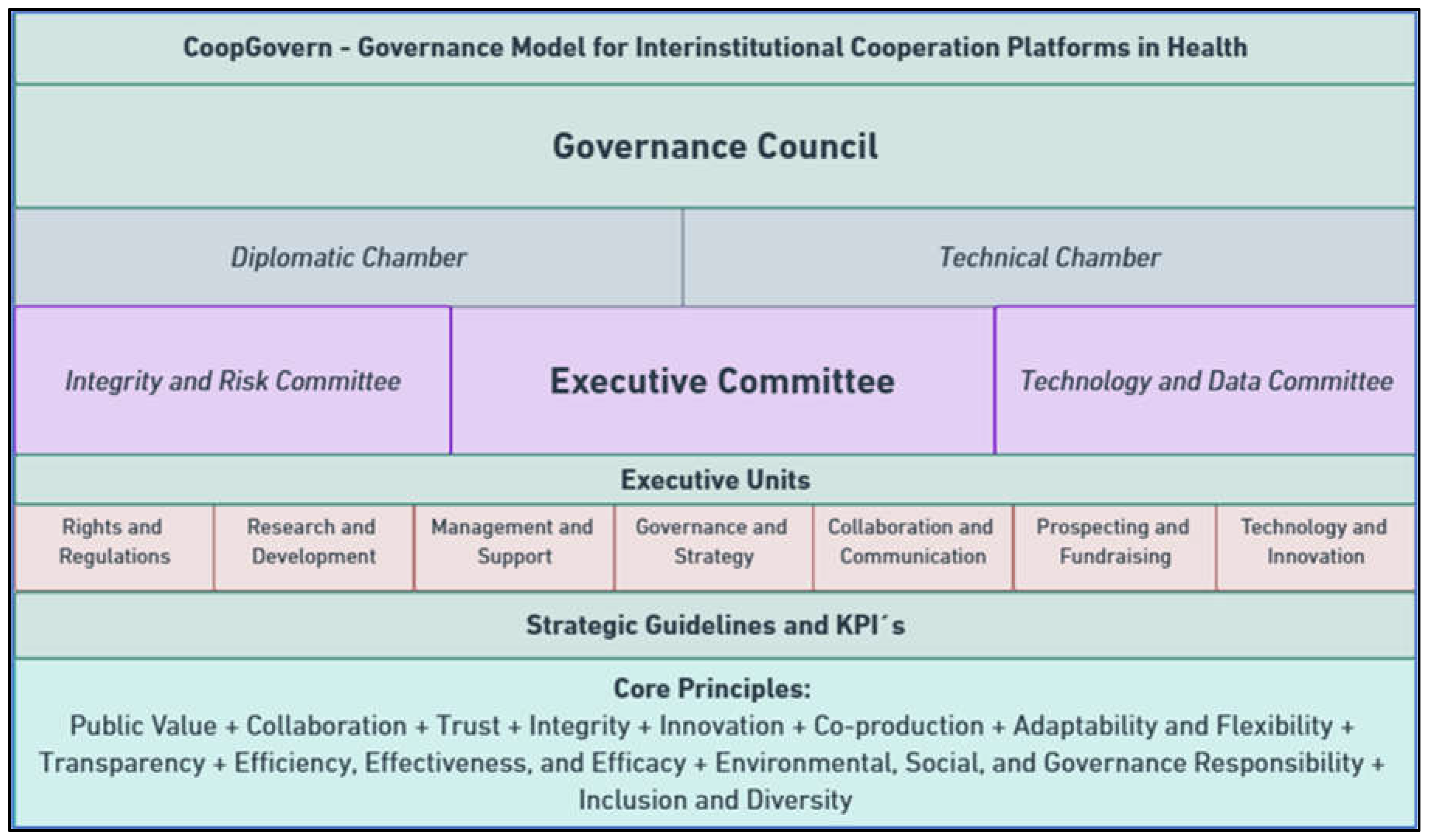

Figure 1 illustrates the structure diagram of CoopGovern, and

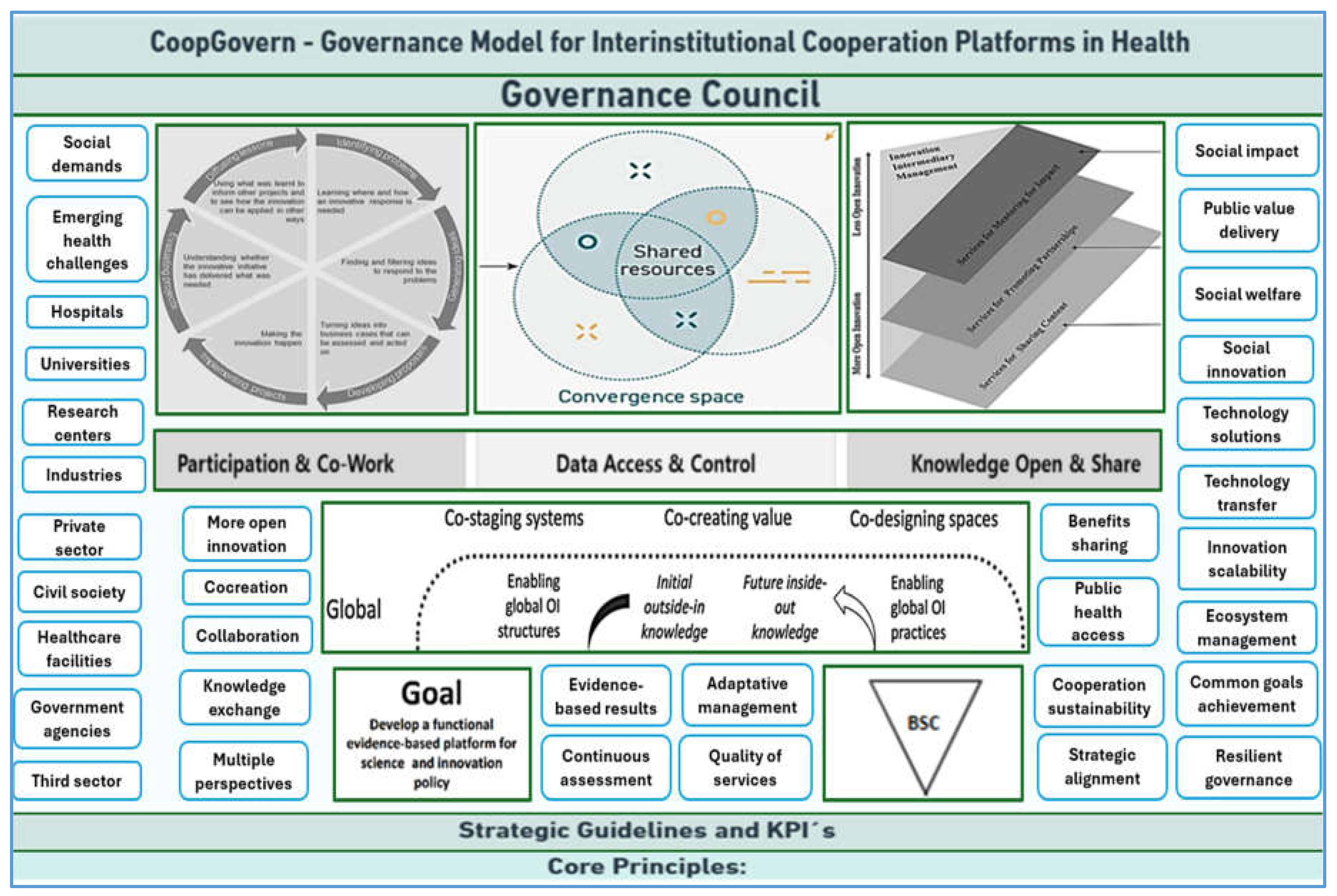

Figure 2 displays the conceptual model of CoopGovern:

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative and empirical approach rooted in the interpretivist paradigm, which posits that knowledge is socially constructed and shaped by contextual influences. Interpretivism is an approach to understand the multiple realities shaped by social and cultural experiences [

5]. This theory is pertinent to the governance of IICPs in ST&IH, which it is inherently influenced by sociocultural and institutional contexts.

Two key methodological procedures were effectively implemented in this study. The first procedure undertaken was a comprehensive literature review meant to identifying best practices and critical success factors for IICP governance. This review encompassed academic literature, public policy documents, reports, and case studies from international organizations and corporate settings. The main goal was to establish a robust theoretical foundation for developing the CoopGovern model.

The second technical procedure involved developing the CoopGovern integrating theoretical and practical governance frameworks identified in the literature review. CoopGovern was developed then using insights into innovation and collaboration within complex environments, such as they occur in ST&IH.

Those selected bases guided key aspects of governance, including internal management structures, evaluation metrics, and open innovation modeling. CoopGovern bases on those models aspiring to harmonize stakeholder interactions, optimize resource sharing, and foster innovation in health systems. CoopGovern incorporates elements of science diplomacy (SD), innovation diplomacy (ID), and health diplomacy (HD). This integration handles limitations in existing governance approaches by improving coordination, optimizing resource sharing, and fostering public value creation.

It is important to mention that the third chosen technical procedure, a comparative theoretical analysis (CTA) of CoopGovern against other governance frameworks and models, remains pending and will be addressed in the next phase of the research. Its objective is to permit a critical evaluation of the CoopGovern model, with emphasis on its novelty while identifying potential adaptations to augment its suitability, effectiveness and applicability. The literature review offers a detailed analysis of key concepts that support the theoretical framework of the CoopGovern. The findings are summarized below:

Science and Innovation Diplomacies (SD and ID): SD is defined as efforts to enhance international scientific collaboration and promote cross-border research. Anunciato and Santos [

6] underscore SD's role in integrating countries into the global ecosystem of ST&I, while Fedoroff [

7] highlights its potential to respond to global challenges through scientific cooperation. ID (a subset of SD) emphasizes fostering international partnerships in innovation to bolster socioeconomic development and enhance technological capabilities across nations.

Health Diplomacy (HD) is viewed as vital for fostering international health cooperation. Scholars such as Kickbusch and Liu [

8] and Labonté et al. [

9] argue that HD facilitates global health governance and supports collaboration amid countries to tackle complex health obstacles. The COVID-19 pandemic exemplifies the significance of international and multilateral health cooperation [

10].

Concept of Platform: The study adopts a broad understanding of platforms, conceptualizing them as collaborative ecosystems that facilitate interactions across governments, industries, academia, and civil society. Baltimore et al. [

11] describe platforms as structures that stimulate interaction between various entities to ease exchanges of goods, services, or information. Gawer and Cusumano [

12] further expand this definition by emphasizing the role of platforms in supporting network effects and innovation within business ecosystems. Dondofema [

13] adds that platforms function as multifaceted ecosystems that support adaptive governance, capacity development, conflict resolution, and power dynamics.

Innovation Platform: Spaces for learning and change, where diverse participants collaborate to identify problems, explore opportunities, and devise solutions. Tui et al. [

14] characterize these platforms as dynamic environments where stakeholders, including for instance, researchers, traders, and government officials, come together to diagnose problems and pursue shared objectives. Osorio-García et al. [

15] emphasized the role of innovation platforms in promoting co-creation and integrated strategies to navigate complex challenges. Dondofema [

16] highlights the practical relevance of incorporating governance structures that enable leadership, capacity building, and adaptability within these collaborative locations.

Concept of Governance: Younis and Zaman [

17] emphasize that governance relies on strong oversight mechanisms, such as audits and accountable boards, to align organizations with stakeholder interests. And flexibility in governance systems is essential for adapting to evolving institutional needs. Li et al. [

18] discuss social governance, highlighting the importance of stakeholder inclusion and collaboration for effective decision-making. Governance, therefore, operates as a dynamic system raising knowledge-sharing and adaptability. Smith [

19] stresses the importance of resilience in governance, noting that flexible structures are crucial for maintaining effectiveness during crises and adapting to changing conditions. These governance principles are significant for managing IICP in ST&I, where adaptability and reliable systems are critical for innovative health policies.

Public Governance faces challenges due to the need for integration across government levels and intersectoral coordination. Peters [

20] highlights the inadequacy of traditional, hierarchical models in addressing complex modern issues like demographic shifts, economic crises, and environmental challenges. New Public Governance (NPG) offers a flexible, collaborative approach where governments facilitate dialogue between sectors and co-create solutions [

21]. Raschendorfer, Roder, and Figueira [

22] emphasize that NPG promotes transparent, democratic governance through citizen participation. Aguilar [

23] underscores the importance of monitoring and the application of evaluation mechanisms to ensure policy effectiveness, while data-driven governance fosters adaptability to emerging needs [

22]. These principles—collaboration, transparency, and adaptability—are vital for IICP governance in ST&IH, where intergovernmental cooperation and accountability drive competent policy implementation and innovation.

Collaborative Governance involves multiple stakeholders in decision-making processes, encouraging active participation from diverse actors to face complex challenges. Ansell and Gash (2008) define it as an inclusive, deliberative approach, where public and private sectors work together to solve issues that a single entity cannot tackle alone. This model responds to the limitations of traditional governance, emphasizing formal and consensual decision-making where actors actively engage beyond consultation. Collaborative governance fosters democratic legitimacy and collective learning through continuous and transparent dialogue [

24]. Bryson, Crosby, and Bloomberg [

25] argue that collaborative engagement is key to creating public value, encompassing not only efficiency but also social justice and democratic participation. The inclusion of NGOs and private sector actors, as highlighted by Calò et al.[

26], brings unique, context-specific insights, particularly in addressing local needs. Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh [

27] offer a model of collaborative governance centered on systemic context, governance regimes, and collaborative dynamics, with trust and shared motivation being essential for success. Wallenius and Varjo [

28] accentuate the challenge of forming collaborative networks and ensuring multilateral accountability, while Larrea et al. [

29] suggest that a territorial approach can unify diverse actors in collaborative efforts. In STI, collaborative governance is important for attending high-complexity challenges through interdisciplinary solutions. The success of such governance depends on balancing power disparities and fostering mutual trust, which enables sustainable collaboration [

26]. Collaborative governance thus provides a framework for integrating diverse knowledge and fostering inclusive, innovative solutions, making it essential in contexts requiring coordination across various governance levels and actors.

Interinstitutional Cooperation (IIC) refers to a structured collaboration framework between organizations aimed at achieving shared objectives. According to Herrera-Kit et al. [

2], IIC involves essential practices such as sectoral aggregation and mutual consultation, with governance playing a central role in safeguarding successful cooperation. Lang [

30] identifies various collaborative mechanisms within IIC—such as mergers, federations, and consortia—that advance network formation, thereby advancing productivity and innovation potential. Herrera-Kit et al. [

2] further underscore the significance of structured governance, particularly in public management, where efficiency and effectiveness are pivotal. The role of governance is also central to achieving the strategic aims of IIC in referring pressing issues in sectors like health, where timely and active responses are significant. In the context of international research collaboration, Wagner and Simon [

31] and Hwang [

32] highlight the significant contributions of these partnerships to scientific advancement, especially for institutions in developing countries. They argue that cross-border collaboration fosters innovation, capacity building, and the shared pursuit of solutions for complex global challenges, including climate change and infectious diseases.

Interinstitutional Cooperation in Health (IICH) is frequently discussed in the literature as a multifaceted strategy analyzed through various perspectives. For instance, in Brazil, Silva et al. [

33] accentuate the importance of strong regional governance within the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) to facilitate productive institutional partnerships. They argue that governance forms the foundation needed to coordinate and sustain collaborative undertakings. Similarly, Herrera-Kit et al. [

2] focus on the value of structured collaborative practices that validate continuous synergy among the participating actors. While Silva and Gomes [

33] concentrate at governance as a central element, Herrera-Kit et al. [

2] attribute significance to the organization of collaborative practices. Together, these perspectives suggest that IICH depends on a governance framework that both coordinates efforts and supports practices promoting integration amongst health institutions. In the health sector, IIC actions has been increasingly recognized as a viable strategy to tackle global crises, a recognition underscored by their role during the COVID-19 pan-demic. Herrera-Kit et al. [

2] suggest that formal mechanisms such as dedicated committees, and informal practices, for instance mutual consultation amid institutions, are decisive to increase this kind of collaboration. According to Gadelha et al.[

34], the flow of knowledge within innovation networks is another indispensable component for sustaining IICH, particularly in Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health (ST&IH). This integration of collaborative strategies and knowledge exchange bolsters the resilience of cooperative platforms, enabling a timelier and coordinated response to health adversities. Moreover, the dynamism within innovation platforms, as discussed by Gadelha et al. [

34], cultivates an environment conducive to knowledge exchange, thereby enhancing health innovation networks. Pellegrin and Caulliraux [

35] also investigate the significance of pro-innovation collaboration within health networks, noting that technological innovation often benefits from these exchanges. While Gadelha et al. [

34] highlight platform dynamics as a driver of innovation, Pellegrin and Caulliraux [

35] view collaborative networks as catalysts for technological advancements suggesting that networks play complementary roles in facilitating IICH. Collectively, these studies illustrate that collaborative governance, by promoting an integrated and efficient IICH, contributes significantly to sustaining innovations and improvements within the health sector.

To evaluate and reinforce the efficacy of interinstitutional collaboration, the Coop-Govern model provides a structured governance framework that is adaptable to the specific needs of ST&IH and introduces key performance indicators (KPIs) to assess strategic guidelines (see a complete list of the KPI´s and related guidelines of CoopGovern at

Appendix B -

Table A2). This model manages the core aspects of coordination, evaluation, and sustainability within collaborative platforms. Building on foundational studies by Lang [

30], Herrera-Kit et al. [

2], and Gadelha et al. [

34], CoopGovern seeks to boost governance approaches within IICH, aligning policies and resources to extend collaborative impact in public health sectors. Ultimately, the CoopGovern proposal aims not only to refine governance arrangements but also to support an environment favorable to innovation and the generation of public value in the health sector.

3. Results

This section aims to demonstrate how the overall objective of this study—to propose a governance model for IICPs that contributes to improving the performance of cooperation activities in ST&IH among institutions and other stakeholders—has been met. It also presents the findings related to the study's central question, focusing on the design and implementation procedures of the proposed governance model.

3.1. The Design Process of CoopGovern

It is noteworthy that the CoopGovern proposal is supported by a series of theoretical and practical frameworks addressing innovation and collaboration within complex contexts, specifically and particularly characteristic of the field of Science, Technology, and Health Innovation (ST&IH). CoopGovern model focuses on providing a governance framework tailored to the specific needs of collaborative initiatives in CT&IH. The CoopGovern model's structure is founded on six core bases that are outlined below:

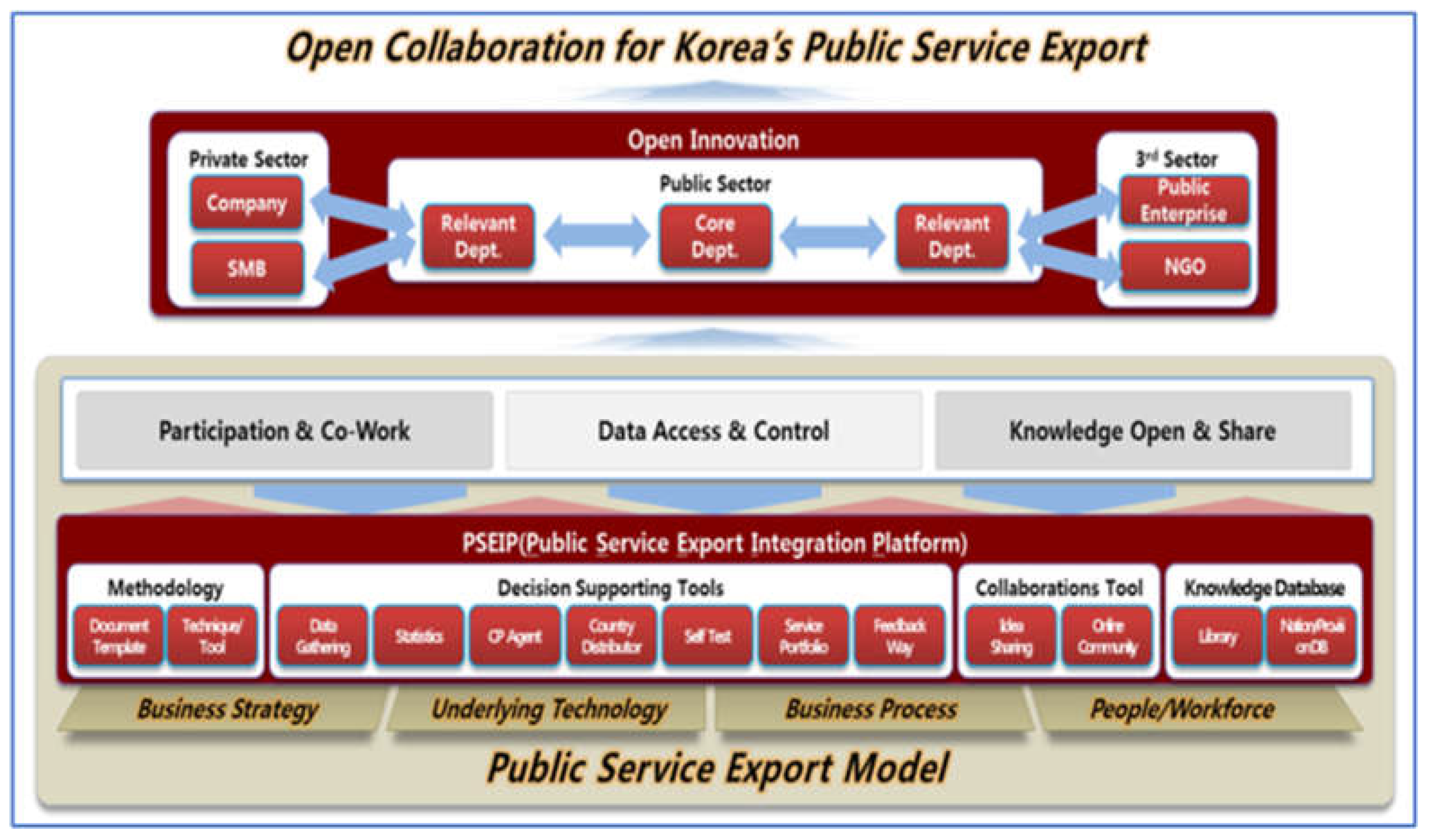

Public Services Platform: Joo and Seo [

36] provide a theoretical and practical framework for collaboration among different public sector agents, aiming to optimize service delivery and promote innovation in governance. This model is relevant for the integration of diverse stakeholders in the health sector, such as hospitals, universities, and government bodies, by facilitating systematic collaboration to improve service access.

Figure 3 shows the Platform Business Model in Public Sector Collaboration Design [

36]:

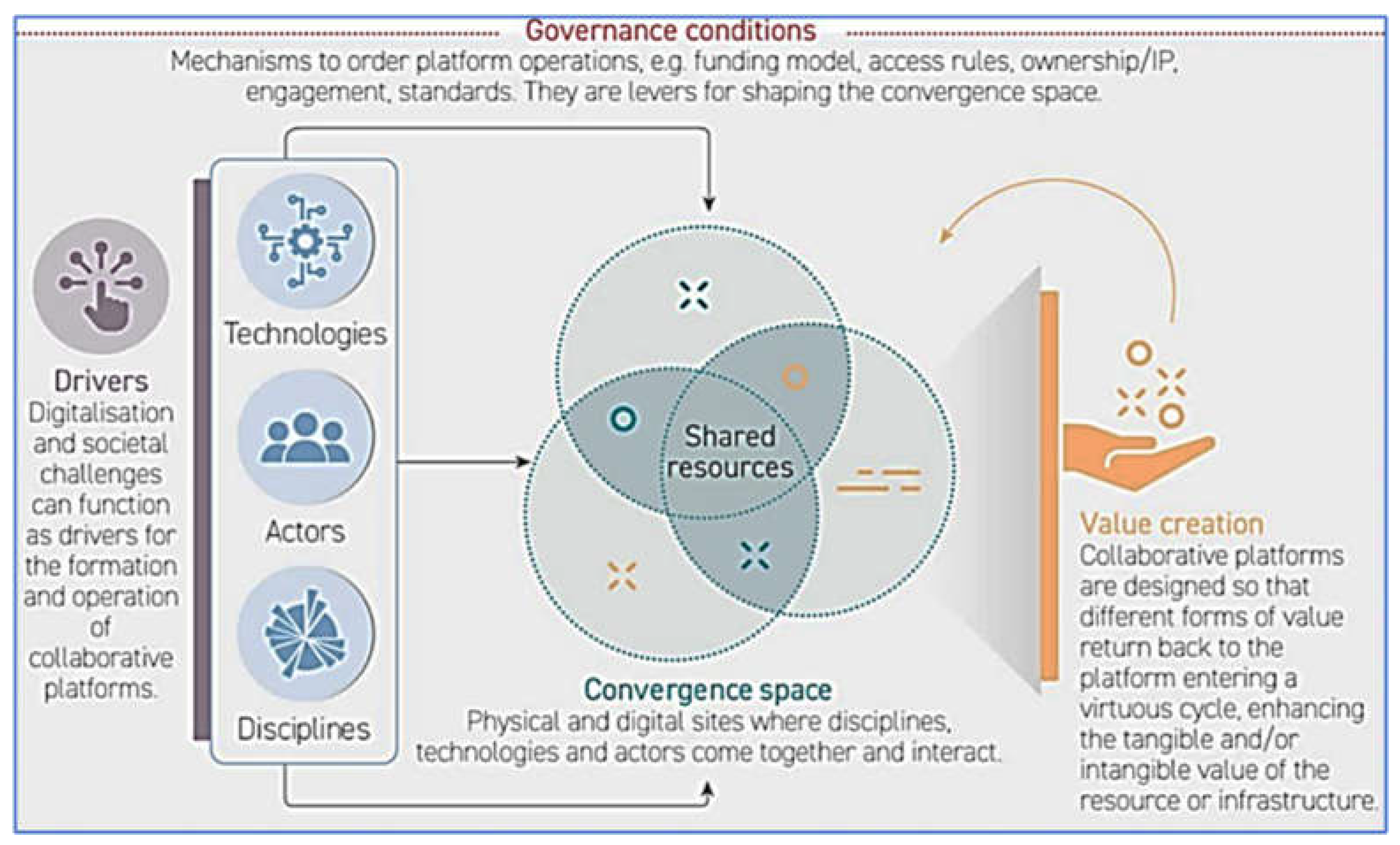

Conceptual Model of Collaborative Platforms as Spaces of Convergence: Winickoff et al. [

37] conceptualize collaborative platforms as dynamic environments that facilitate knowledge and resource flows among diverse stakeholders and disciplines. This approach aligns with CoopGovern’s goal of fostering an environment that maximizes the impact of health innovation projects by encouraging convergence and adaptive governance.

Figure 4 presents Conceptual Model of Collaborative Platforms as Spaces of Convergence [

37]:

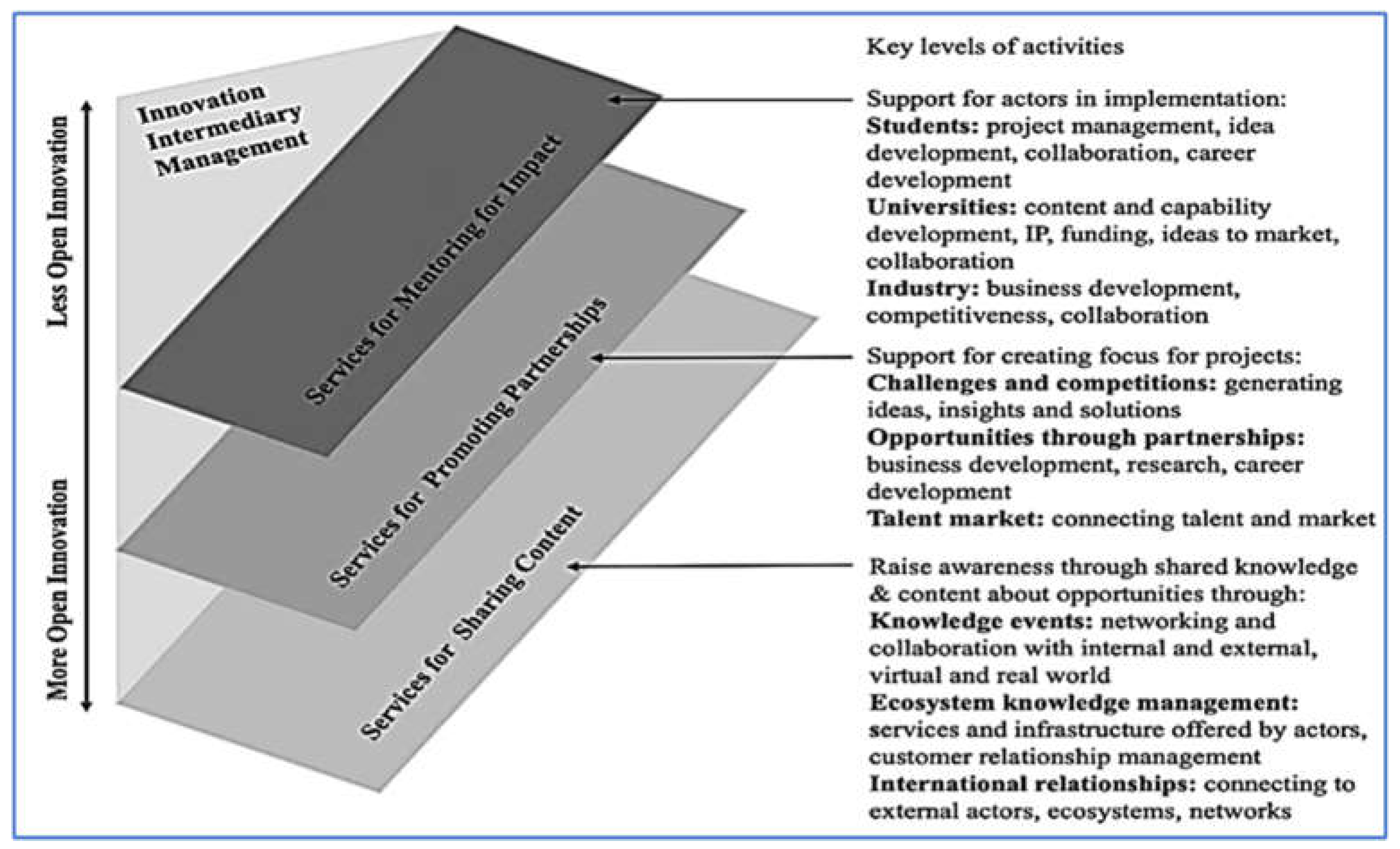

Multilevel Platforms and Service Activities theorized by Koria et al. [

38] have governance mechanisms that work as a component that coordinates activities across local, national, and international levels to enhance collaboration in large-scale interinstitutional projects, ensuring an integrated and coherent approach to innovation governance.

Figure 5 highlights the Multilevel Platforms and Service Activities [

38]:

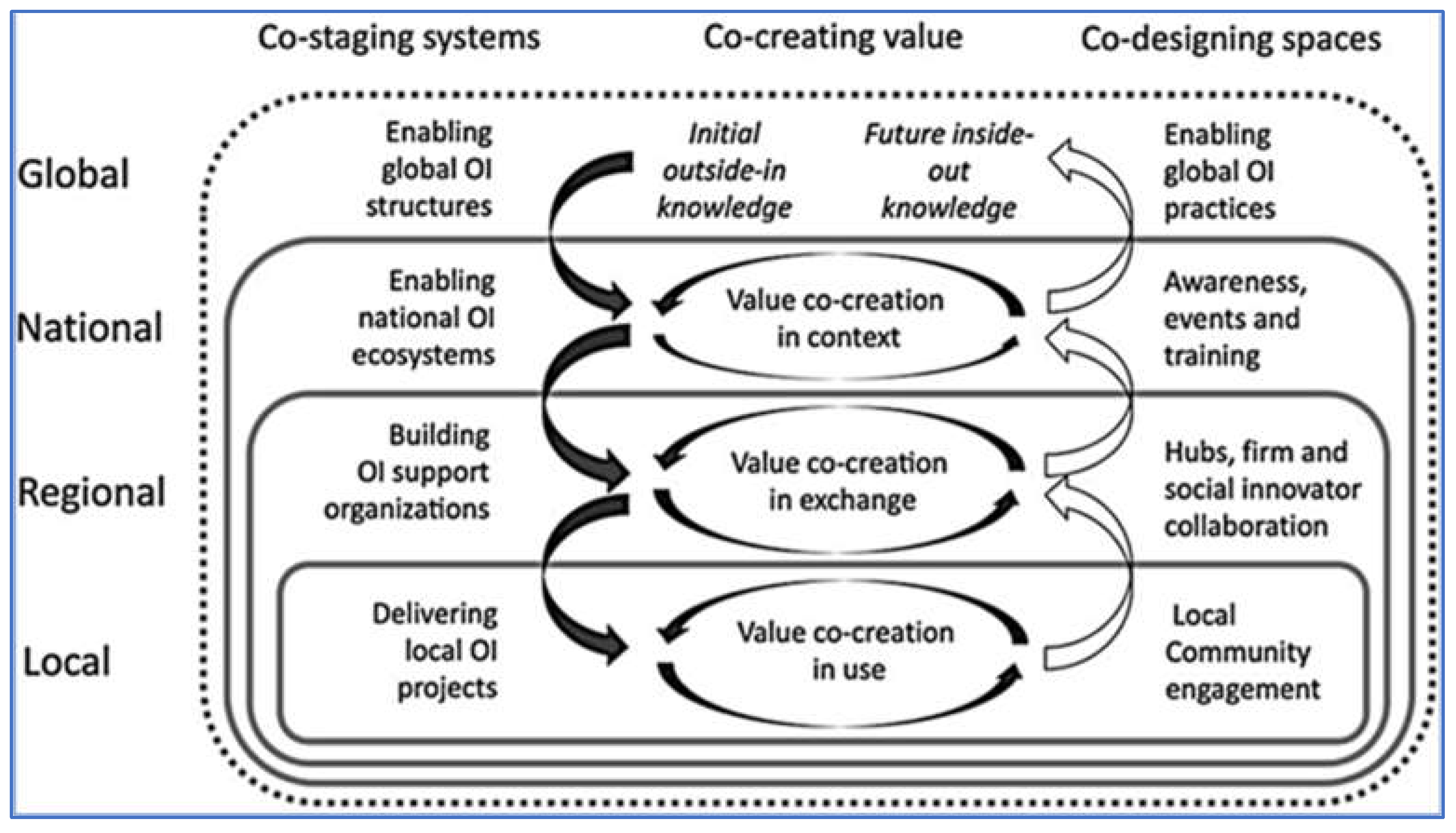

Value Creation Modeling in Open Innovation [

39]: Following the principles outlined by Osorno-Hinojosa et al. [

39], CoopGovern emphasizes value co-creation through collaborations between universities, industries, and research institutions. This approach supports the dissemination of innovations across sectors, promoting a broad distribution of benefits.

Figure 6 displays the Value Creation Modeling in Open Innovation [

39].

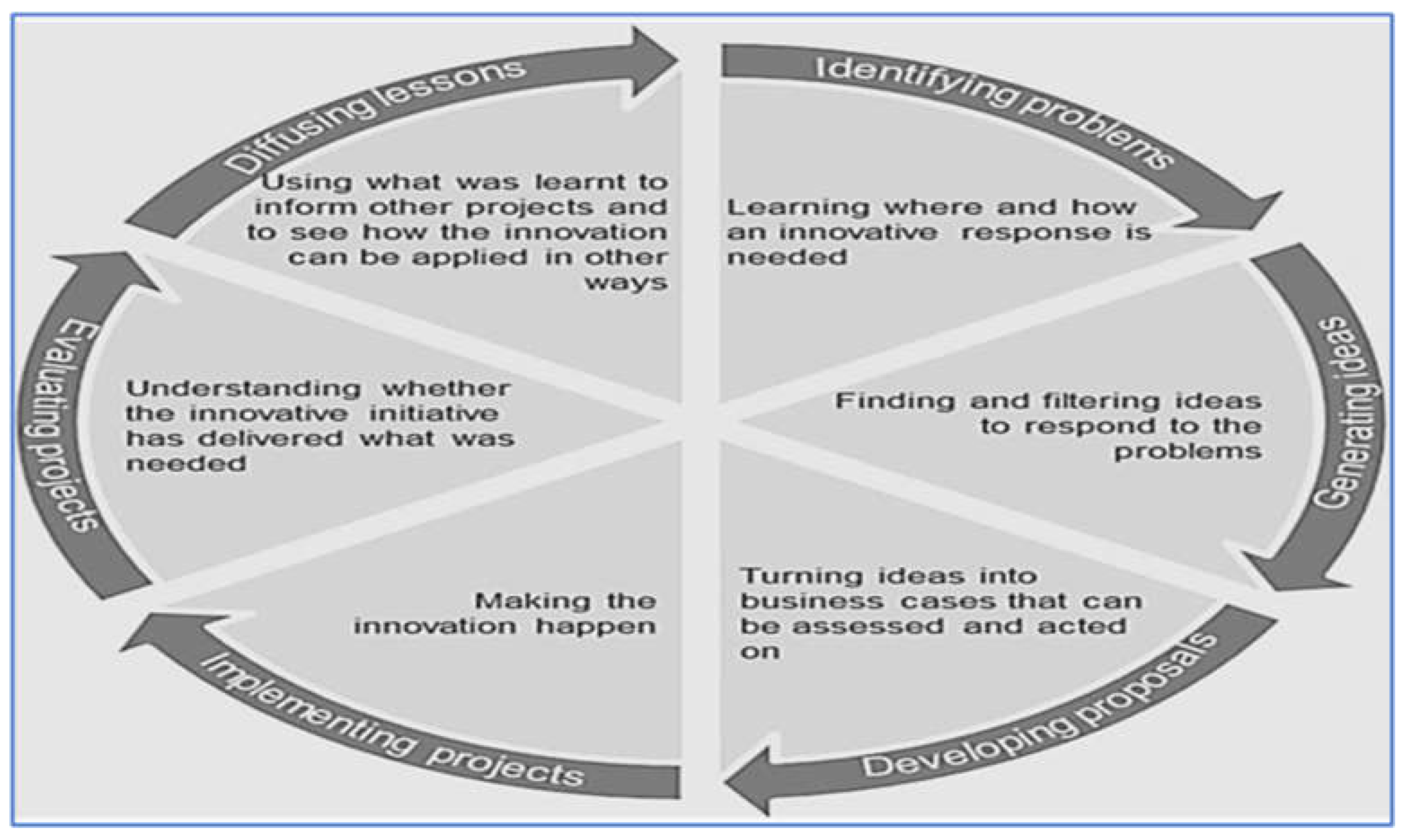

Innovation Lifecycle Model [

40]: CoopGovern aligns with the innovation lifecycle model outlined by the OECD, which structures the process from idea generation to continuous improvement, allowing for monitoring and adaptive management of innovation initiatives.

Figure 7 indicates the Innovation Lifecycle Model [

40].

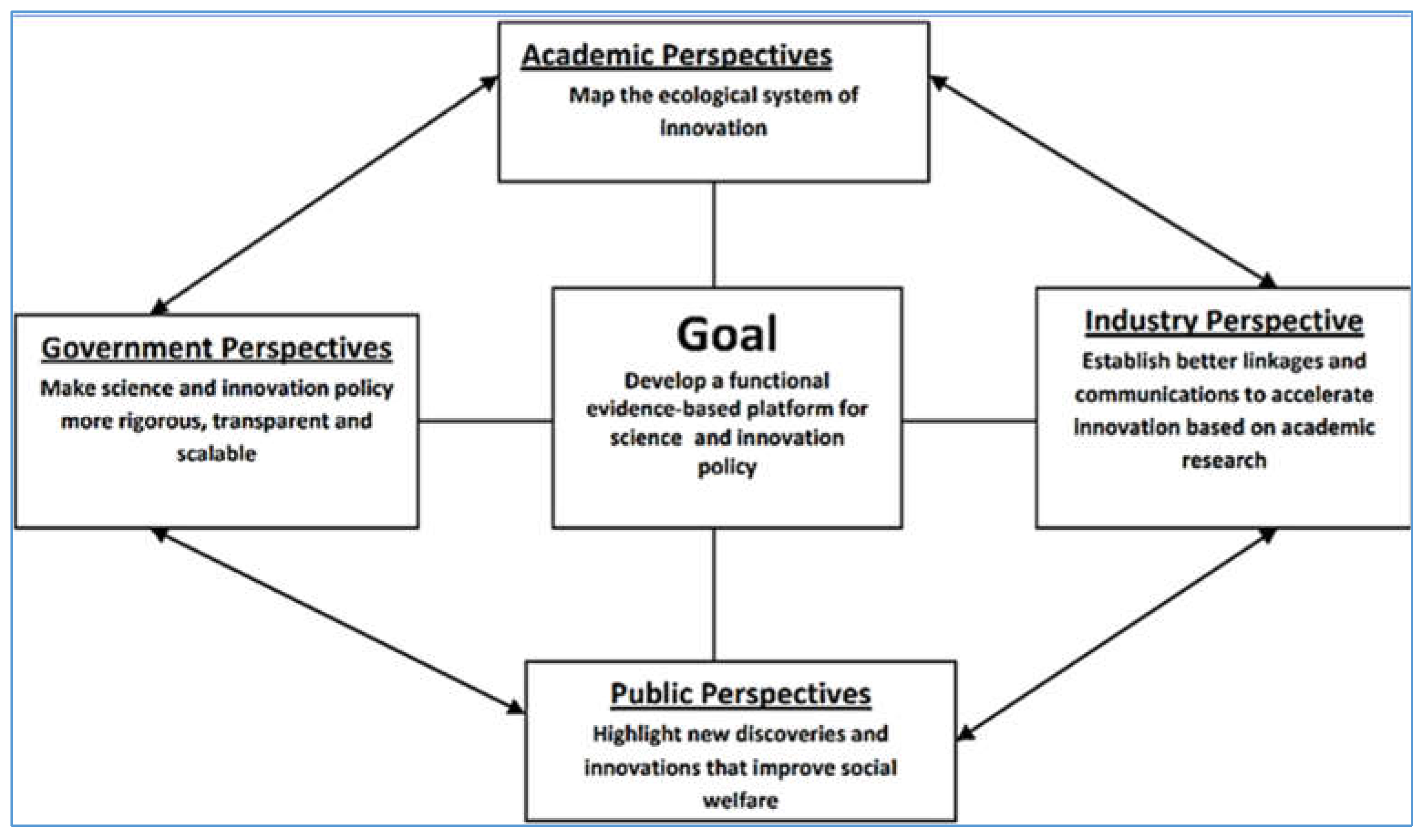

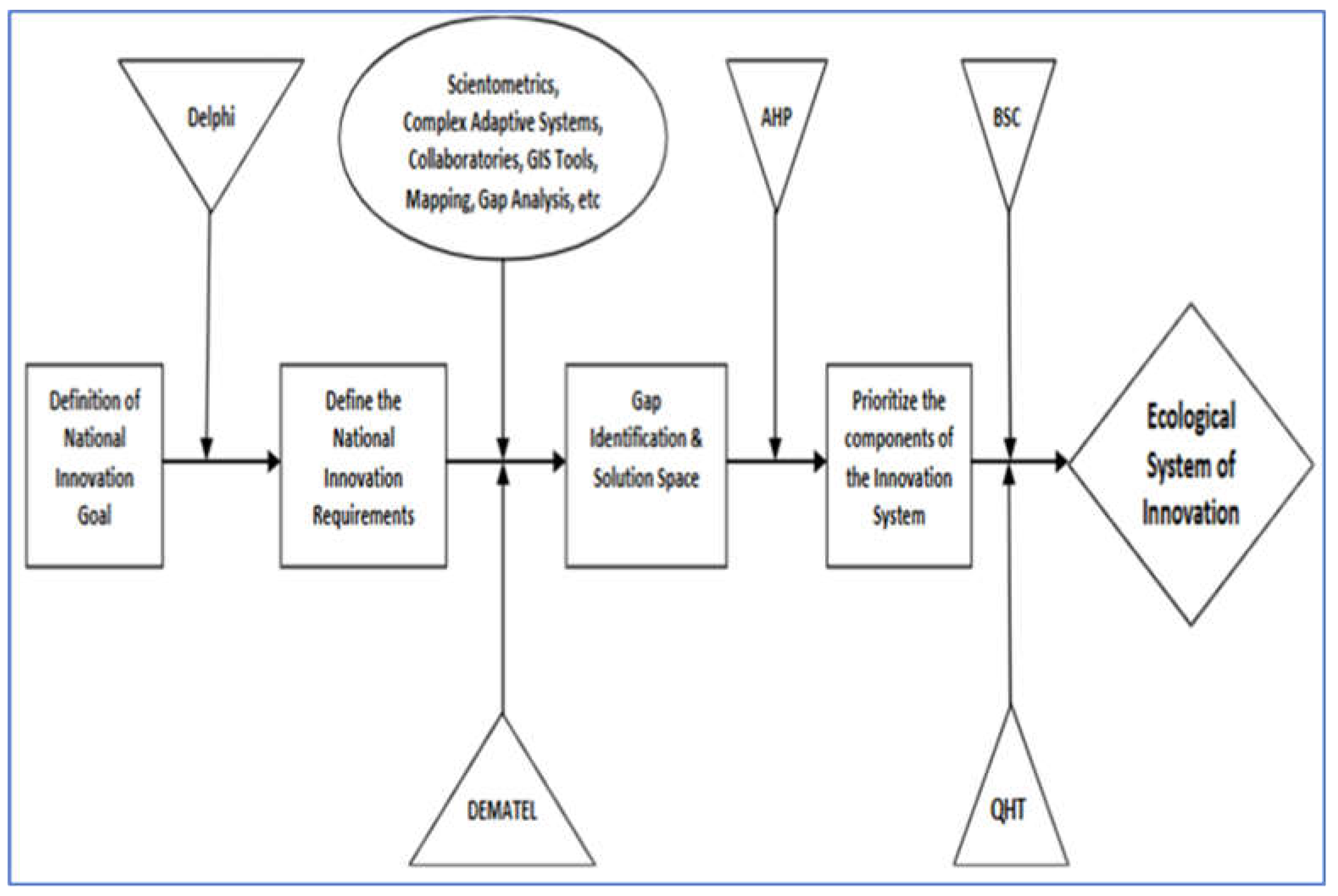

Ecological System of Innovation (ESI): Conceptualized by Yawson [

41], serves as a structure guiding the responsive and evidence-based strategy design of CoopGovern, underscoring the interdependence of stakeholders within the innovation ecosystem. This paradigm promotes continuous knowledge exchange and collaboration to effectively tackle progressing issues. Yawson’s model integrates diverse perspectives within national innovation systems and reinforces the necessity of evidence to guide science, technology, and innovation policies, emphasizing the significance of a cohesive and responsive method. ESI further suggests that scorecards, or key performance indicators, are instrumental in this structure.

Figure 8 illustrates the multiple perspectives considered by ESI [

41], while

Figure 9 details the ESI design process [

41], incorporating these scorecards.

3.2. CoopGovern Coordination and Functioning

CoopGovern’s governance structure consists of a main council, consultive chambers, committees, and executive bodies or units designed to accelerate decision-making and guarantee strategic alignment.

Governance Council leads the strategic planning and is responsible for final decision-making, overseeing overall supervision, internal control, and auditing. It is supported by the Diplomatic Chamber for Science, Innovation in Health that exerts an advisory role, and represents the IICP in international issues, negotiations, and public relations, including interactions with multilateral organizations. And, by the Technical Chamber on Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health that provides technical advisory guidance aimed at directing, updating, and enhancing the IICP's scientific, research, development, and innovation activities.

Executive Committee implements the strategies proposed to the IICP, while the Integrity and Risk Committee ensures compliance with ethical and legal standards Technology, Governance, and Data Protection Committee oversees the technological infrastructure, security management, and data protection of IICP and its participants. It ensures that innovation solutions in products, services, and internal processes are aligned with strategic needs and applicable regulatory requirements.

Execution Units engage in tactical and operational activities to execute defined strategies. Their specific roles encompass a range of actions from technological innovation and strategic management to legal-regulatory aspects, collaboration rules, network management, research and innovation communities of practice, knowledge dissemination, fundraising, and scientific and technological prospecting.

3.3. CoopGovern Implementation

As demonstrated before the design and implementation of CoopGovern involves the application of collaborative and multi-level platform concepts, value modeling in open innovation, and other structures that facilitate public management and the governance of intricate initiatives. The details of that process are presented below.

The public service platform proposed by Joo and Seo [

36] offers a collaborative framework that maximizes resource management and service quality in the public sector, addressing challenges such as intergovernmental coordination and diverse social demands. In CoopGovern, this framework permits the integration of hospitals, universities, and government agencies to expand access to healthcare services, functioning as a cooperative ecosystem that promotes innovation and unifies shared objectives. The foundational structure of cooperative platforms, as conceptualized by Winickoff et al.[

37], supports the underlying objectives of CoopGovern. These types of platforms are “spaces of convergence” where governments, industries, universities, and civil society can co-create innovative solutions. These dynamic platforms exchange information, resource, and knowledge across projects and technologies. CoopGovern applies this model to empower coordination involving governance levels and stakeholders, encouraging a cooperative environment that stimulates innovation and allows governance to swiftly adjust to rising challenges.

The multi-level platform model by Koria et al. [

38] accentuates the integration of governance levels and coordination of service activities within a collaborative platform, particularly suited to complex environments where governance must span multiple hierarchical and sectoral levels, effectively managing interactions at local, regional, national, and international scales. This model equips CoopGovern with a framework to orchestrate activities and interactions among institutions of varying scales, essential for large inter-institutional initiatives focused on cooperation and health innovation. Adopting a multi-level platform approach facilitates coherent and integrated governance across fronts, certifying that all involved parties work in synergy—imperative for sustaining long-term projects that CoopGovern aims to support.

The open innovation model, as analyzed by Osorno-Hinojosa et al. [

39], centers on value generation within cooperative settings, where diverse stakeholders—particularly universities and industries—engage in developing novel technological and social solutions. This framework for value generation is significant for CoopGovern, as it allows for co-creation of value across various institutions, cultivating the exchange of knowledge and innovative practices applicable to public health. By adopting an open innovation approach to value generation, CoopGovern seeks to assist the broad dissemination of IIC benefits across participating entities. The emphasis on shared knowledge, technology transfer, and exchange practices between universities, research centers, and industries is essential for the success of health innovation initiatives, synchronizing with CoopGovern's goals. This model supports innovation that is inclusive, sustainable, and scalable, extending societal benefits.

The innovation lifecycle model proposed by OECD [

40] outlines the sequential phases of the innovation process, from initial idea conception to implementation, learning, and adaptation. These stages—typically comprising idea generation, R&D, testing, iteration, implementation, and adoption—form a continuous loop of review and improvement. This framework is particularly valuable for CoopGovern, providing a structured, monitored pathway for IICPS initiatives to adapt to evolving technological and health innovation needs. By applying this lifecycle model, CoopGovern establishes a methodologically sound structure to guide IIC practices in ST&IH. Each phase is supported by specific metrics and indicators, qualifying CoopGovern to maintain strategic arrangement and fit as new challenges occur. This model not only simplifies rigorous monitoring of each innovation phase but also secures sustainable, long-term impact through regular review, supporting public health objectives by stimulating scalable, adaptive innovation within a collaborative governance framework.

The CoopGovern proposal is reinforced by the Ecological System of Innovation (ESI) model, as described by Yawson [

41]. This model provides an evidence-based framework to guide science, technology, and innovation policies through an integrated, flexible approach. ESI underscores the interdependence among key innovation ecosystem ac-tors—government, academia, industry, and civil society—who collaborate to develop innovative solutions. Central to ESI, and highly relevant for CoopGovern, is the use of key performance indicators (scorecards) to monitor, measure, and manage progress toward established goals, enhancing transparency and enabling targeted adjustments. In Coop-Govern, these indicators offer ongoing, detailed assessments of social impact, technological innovation, and efficiency, which are decisive for evaluating success in ST&IH initiatives. The ESI model’s flexibility ensures that CoopGovern can effectively address shifting issues in the health sector, sustaining resilient governance in a dynamic environment. ESI further underscores the importance of evidence-based decision-making, aligning with CoopGovern’s objective of utilizing dependable data to guide strategic actions and maximize resource allocation. Centered on generating public value, ESI integrates with CoopGovern’s mission to propel innovation in public health for the benefit of society, thereby guaranteeing that ST&IH initiatives deliver measurable improvements in public well-being.

4. Discussion

The CoopGovern developed for governing IICP in ST&IH is a structured framework designed to accelerate innovation and collaboration across diverse stakeholders. Rooted in established theories of collaborative and public governance, CoopGovern aims to generate public value through an adjustable governance model that integrates strategic, ethical, and technical dimensions.

4.1. Foundations of CoopGovern

CoopGovern's core principles—public value, collaboration, trust, integrity, innovation, and adaptability—guide its governance processes (see the complete list of the core principles at the

Appendix A Table A1). The model prioritizes public value, concentrating on equity, sustainability, and societal welfare, particularly in enriching public health services. Collaboration within diverse actors, including government agencies, research institutions, and civil society, is required for engaging with the multifaceted issues in ST&IH. Through assisting shared responsibility and the joint development of solutions, CoopGovern supports the innovation needed to manage these demands successfully.

Trust and transparency are integral to the model’s success, reassuring accountability and ethical decision-making. The adherence to these values warrants institutional credibility and develops cooperation. CoopGovern also underlines innovation allowing institutions to respond in effect to evolving political, social, and technological landscapes [

23,

42,

43]. This malleability is particularly relevant in CT&IH area, where the pace of changes requires constant adjustment.

4.2. Practical Applications and Governance Mechanisms

The multi-level governance framework of CoopGovern allows it to operate across local, national, and international levels, facilitating cooperation including various institutions. This structure warrants coherent policy implementation and synchronizes strengths toward common goals, making it particularly productive in fixing the multifaceted challenges of public health governance.

4.3. Key Implications

The implications of CoopGovern are significant for policy and practice in CT&IH equally. By integrating standards of collaborative governance, the model develops the capacity of institutions to innovate while maintaining transparency and accountability. Its malleability to different institutional contexts makes it a versatile tool for managing interinstitutional cooperation, warranting the generation of public value through inclusive and transparent governance processes.

4.4. Main Features

CoopGovern is designed to assist the governance of complex, collaborative initiatives in health and innovation. Its main features include:

- ▪

Supporting multilevel collaboration between governments, industries, and academic institutions;

- ▪

Encouraging innovation through open platforms that promote knowledge sharing and resource pooling;

- ▪

Providing a governance structure that reinforce transparency, accountability, and versatility in managing interinstitutional cooperation (IIC);

- ▪

Bolstering the sustainability of public health solutions through a collaborative governance paradigm.

By integrating all those foundations, the CoopGovern model aims to support the applicable enhanced governance for interinstitutional cooperation platforms (IICP) in CT&IH.

4.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study encounters limitations primarily due to its specific emphasis on interinstitutional cooperation (IIC) in Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health (ST&IH). While destined to developing a governance model to support interinstitutional arrangements and information sharing, the research depends on secondary data and existing available literature, limiting comprehensive analysis of functional processes across varied contexts. Theoretical models and case studies, though informative, may not encompass the full range of interinstitutional cooperation (IIC) detailed scenarios, thereby constraining the applicability of the findings. In addition, the data reflects time-related limitations in a rapidly evolving field, indicating that the conclusions may require updates as new trends and insights surface. Further limitations include resource restrictions, particularly of time and funding, which narrow the scope of the study and its exploration of key challenges in interinstitutional cooperation (IIC). Future research would benefit from access to complete primary data, expanded funds, and longitudinal and field studies to deepen perceptions into governance processes and consolidate the robustness of findings across diverse settings. Numerous potential research avenues could further refine and extend the CoopGovern model. Several of these directions are outlined below:

Theoretical Comparative Analysis (TCA): This is the third technical procedure of this research. It is a promising area for future research in the assessment of CoopGovern against other governance models. This approach will assess CoopGovern's adaptability, innovation, and public value generation by comparing it to similar interinstitutional governance frameworks. The TCA will assess CoopGovern’s organizational structures, decision-making processes, and cooperation mechanisms, identifying its strengths and areas for improvement. Through this comparative lens, future research will explore how well CoopGovern’s principles, guidelines, and KPIs align with other models, and how its collaborative structure can be further refined to enhance governance in science, technology, and public health.

Validation of CoopGovern: An applied study on concrete and representative field cases of IIC in ST&IH to measure the effective applicability of CoopGovern as designed (or adapted/customized), based on an analysis of identified critical factors, challenges, and theoretical-practical reference models. The validation may be conducted through specific tests (utility tests, satisfaction questionnaires, assessment scales, and impact matrices), which can be administered to participants (users, beneficiaries, and other stakeholders) from selected representative cases (sample spaces).

Longitudinal Studies: Evaluating CoopGovern’s long-term impact in various contexts will provide insights into its adaptability and effectiveness over time.

Technological Integration: Future studies could explore how emerging technologies such as and big data, artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, smart contracts, digital twins, augmented and virtual reality tools can improve CoopGovern’s decision-making and information management capabilities.

Application to Other Sectors: Investigating CoopGovern’s pertinency beyond public health and healthcare, in other fields like education or environmental governance, would test the model’s versatility.

Socioeconomic Impact: Research on the socioeconomic outcomes of services, products social and technological innovations driven by IICP applying CoopGovern model could highlight its broader benefits to public health and social equity.

Progressed Civil Society Participation: Exploring ways to increase citizen engagement within IICP using CoopGovern’s framework may consolidate its legitimacy and effectiveness in public policy development [35, 38].