Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. Research Problem and Study Contributions

- A data-driven , cloud-based method for the static risk assessment of mobile apps resident on an MD.

- An effective innovative filter-based feature selection (FS) technique for static app classification.

- A proof-of -concept prototype of an innovative distributed hybrid intrusion detection and prevention system (IDPS) .

- A flexible framework for building distributed systems for the protection of MCC user data and devices.

2. Materials and Methods

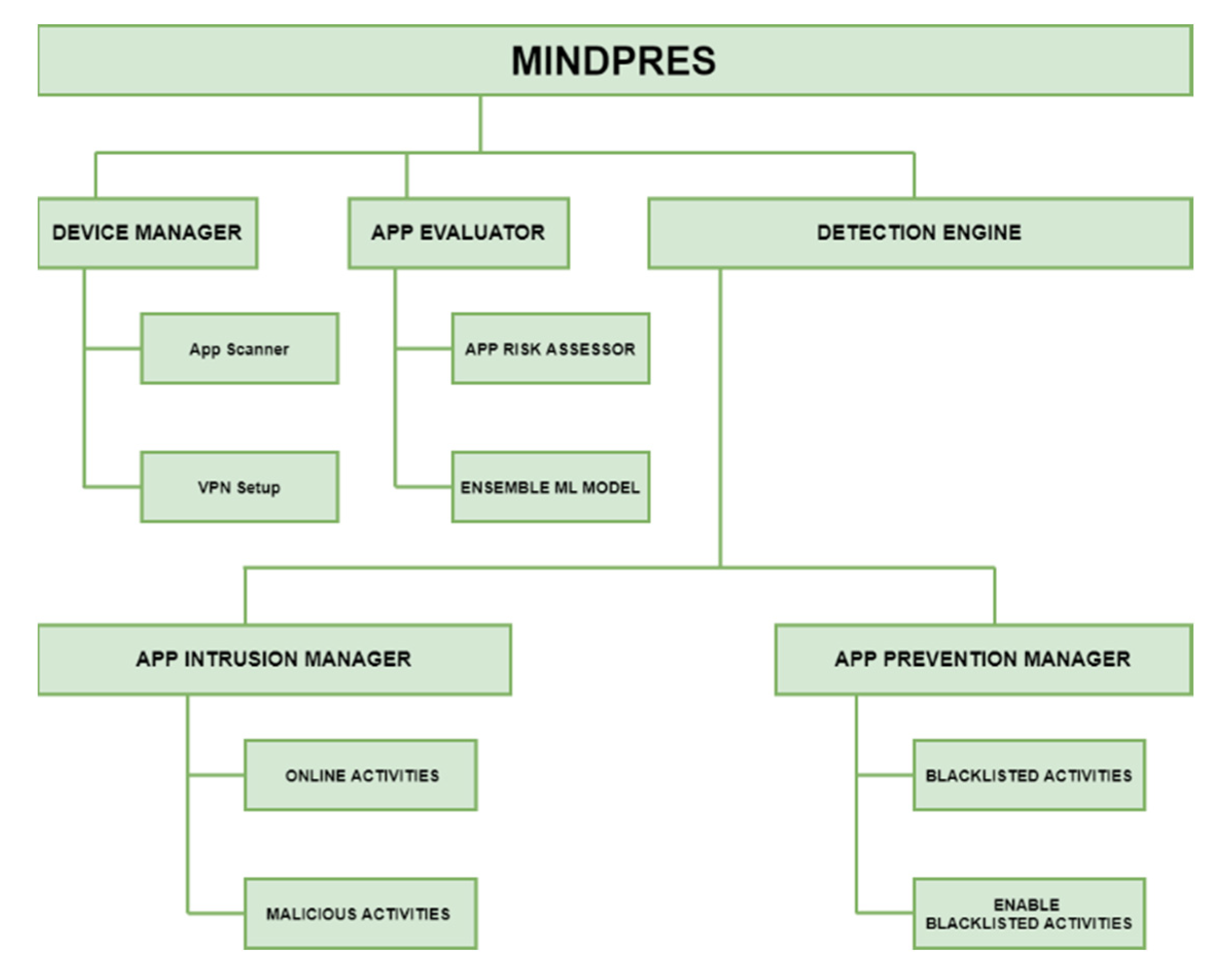

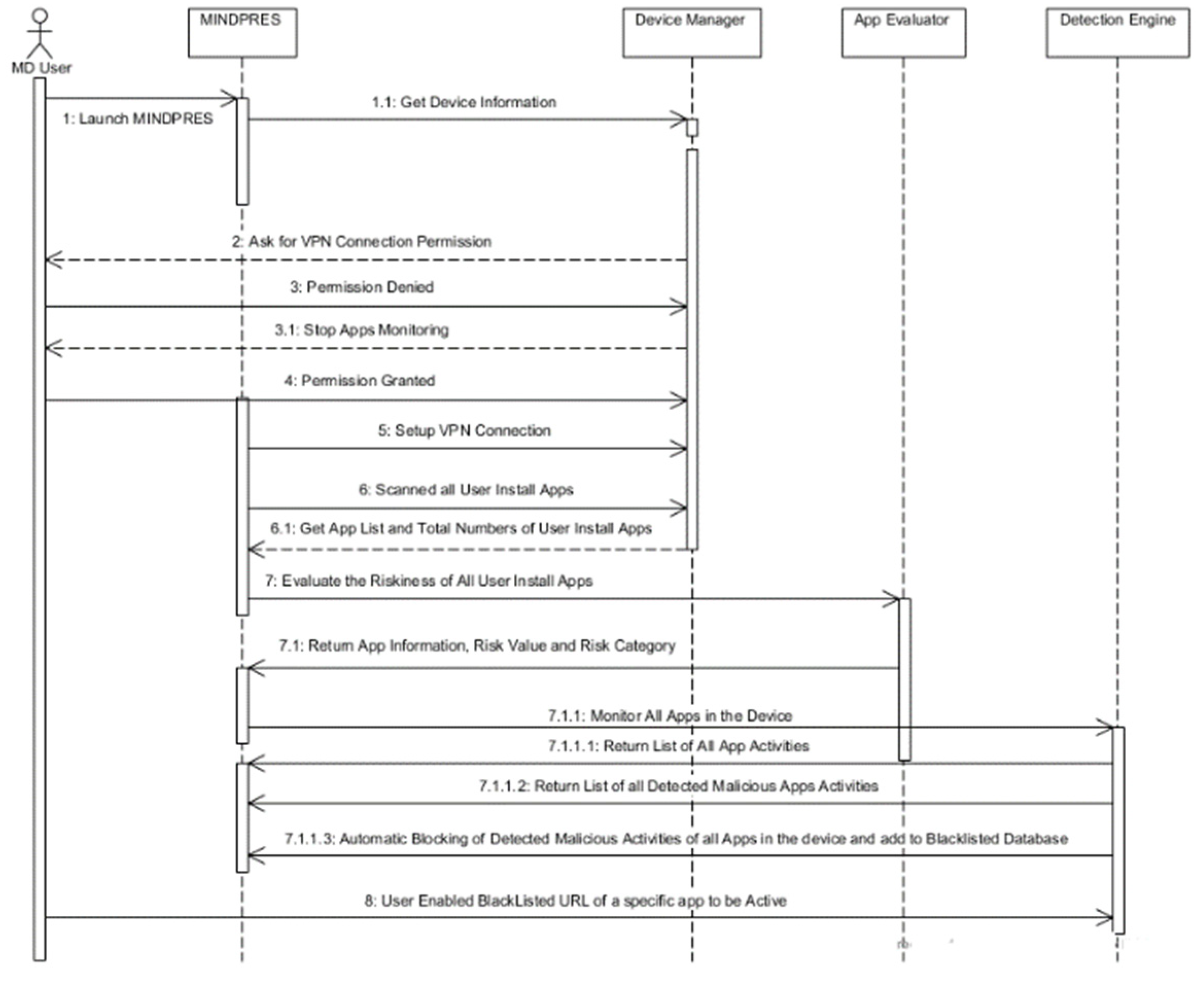

- When MINDPRES is installed on a device for the first time, it analyzes each user-installed app and determines its risk category (high, medium, low). Apps that fall into the high and medium risk categories are placed in a watchlist.

- When a new app is installed on a device the host IDS of MINDPRES is automatically invoked to perform a static analysis and assign the app a risk category.

- The network and host IDS of MINDPRES monitors the API calls made by apps and apps’ network activities both when the user is using the device and when the device is idle. The system prioritizes monitoring the behavior of the apps that are already on the watchlist.

- The IPS automatically blocks apps when suspicious activities or malicious network traffic are detected. Due to the possibility of false alarms, MINDPRES gives users the option to override the block and execute the app.

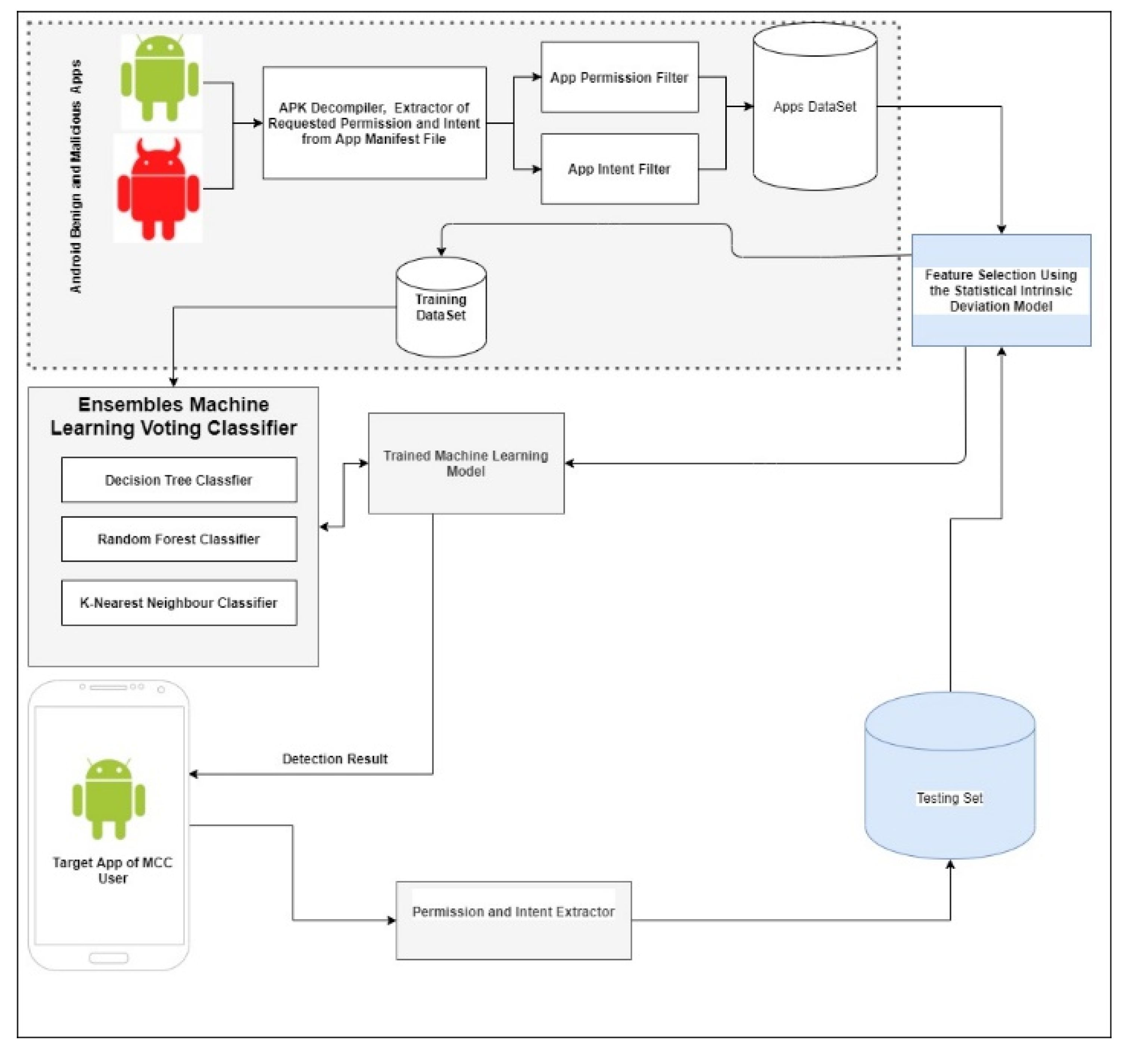

2.1. Feature Selection Method

2.2. Ensemble ML Model for Static App Classification

2.2.1. ML Classification Algorithms

2.2.2. Algorithm Performance Evaluation

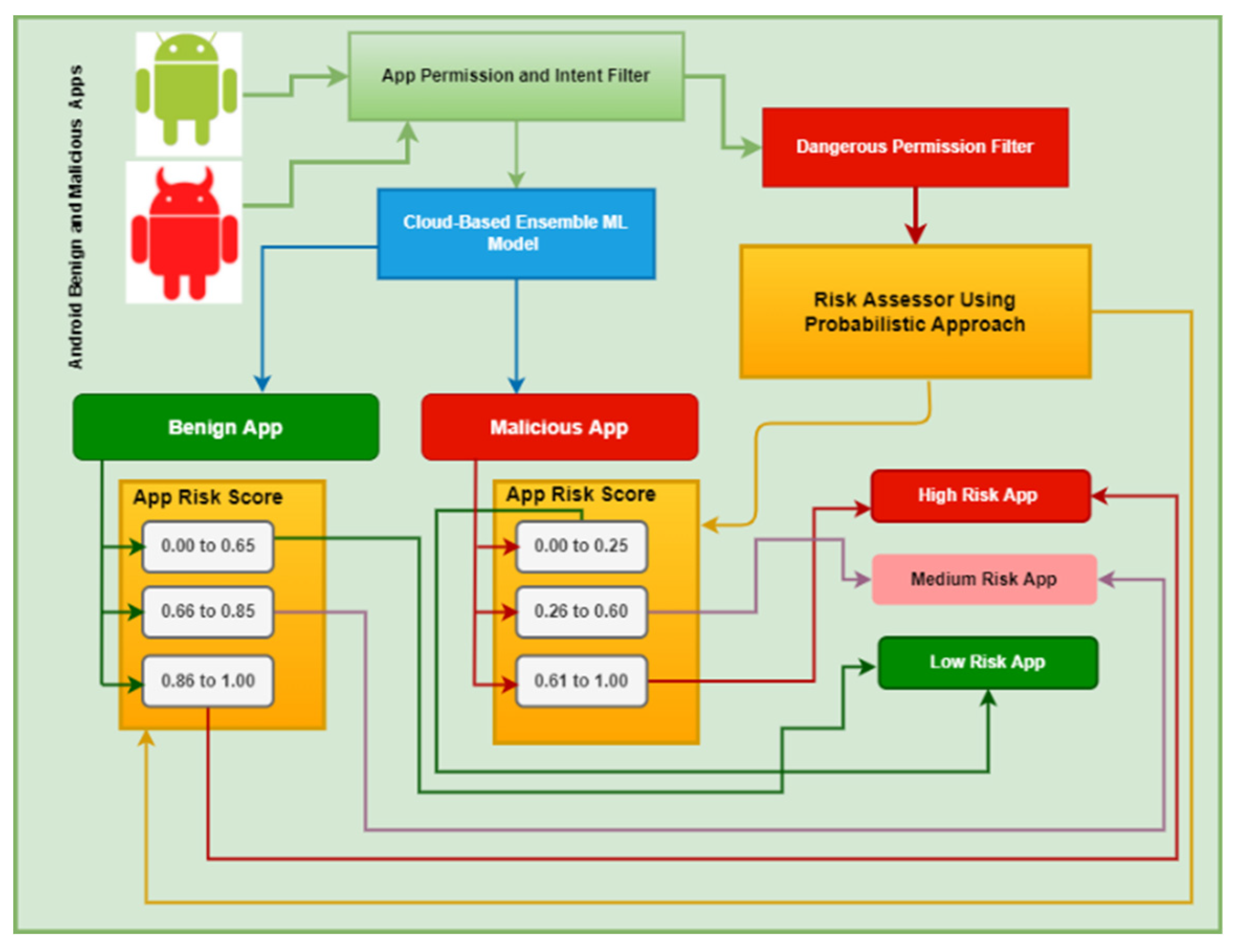

2.3. Static App Risk Evaluation Method

2.3.1. Risk Scores of Dangerous Permissions

2.3.2. App Risk Score

2.3.3. App Risk Category

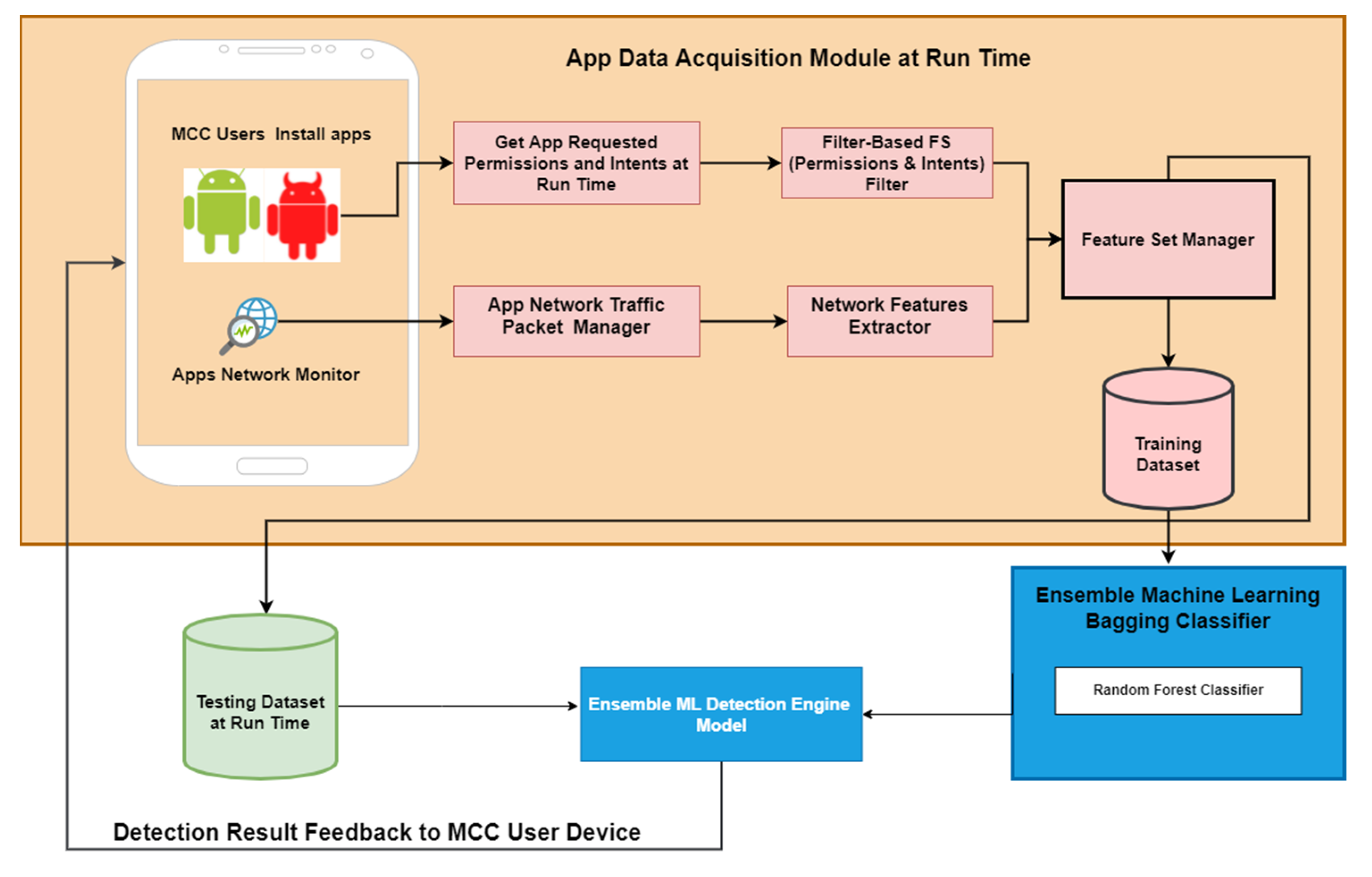

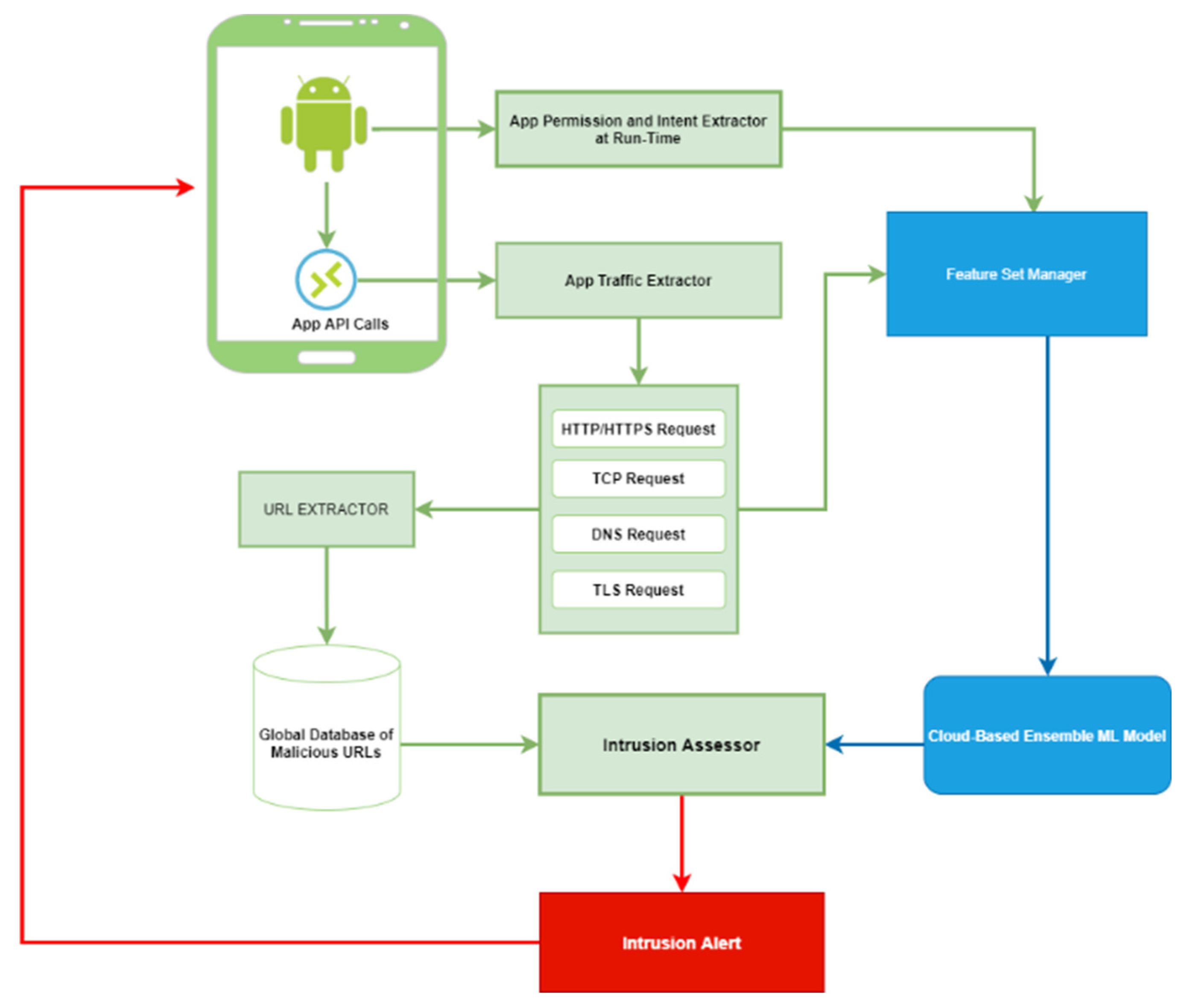

2.4. Dynamic App Risk Evaluation Method

- An ensemble ML model for the analysis of API calls made by apps at run time. The model analyses an app’s dynamic activities based on network traffic data to detect malicious activities performed by apps resident on the MD.

- An ensemble ML model for app classification based on run-time permission and internet requests. In this study, the model described in section 2.2 was used for the purpose.

2.4.1. Data Acquisition

2.4.2. Feature Selection

2.4.3. Ensemble ML Model for Dynamic App Activity Classification

3. Results

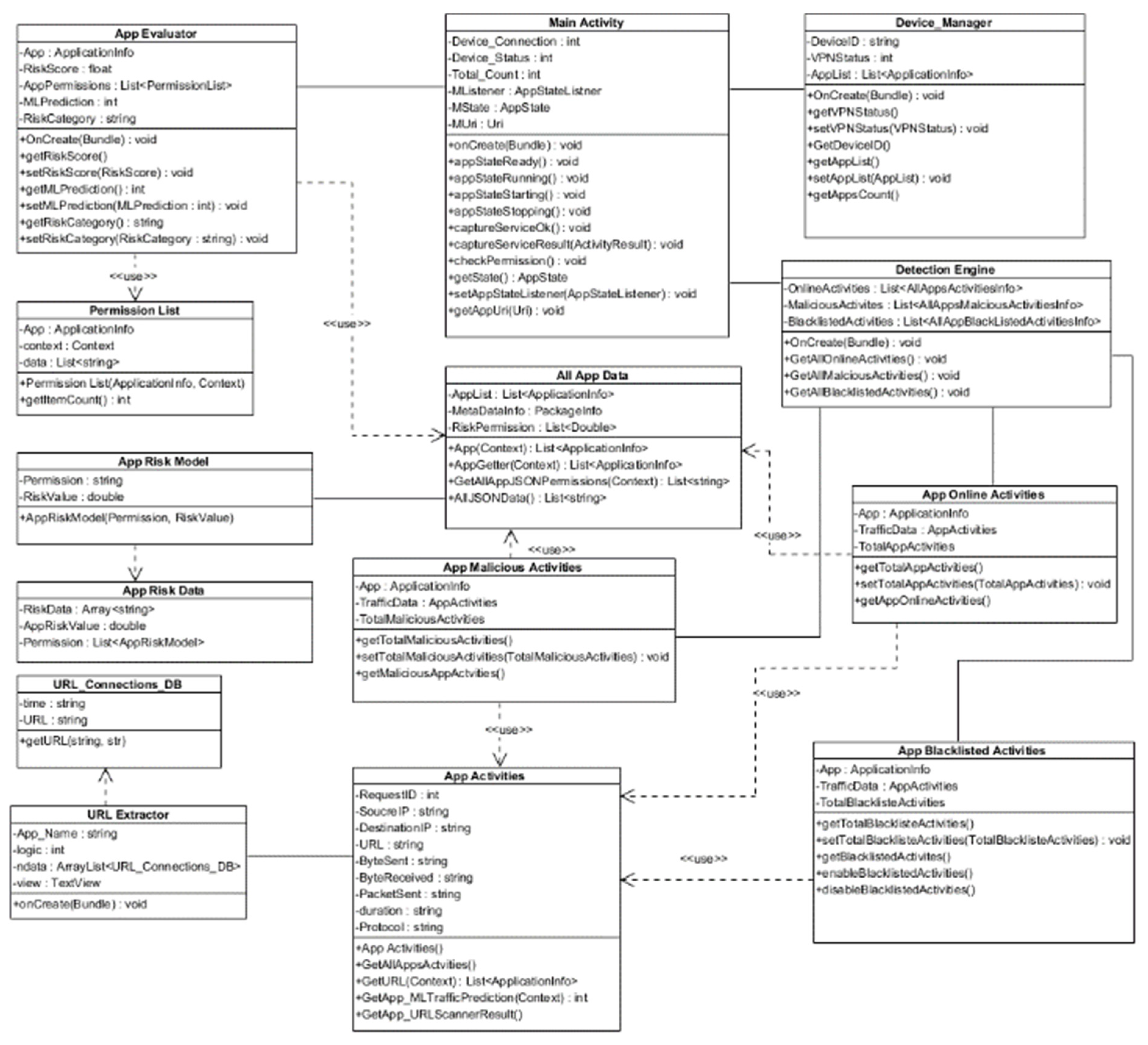

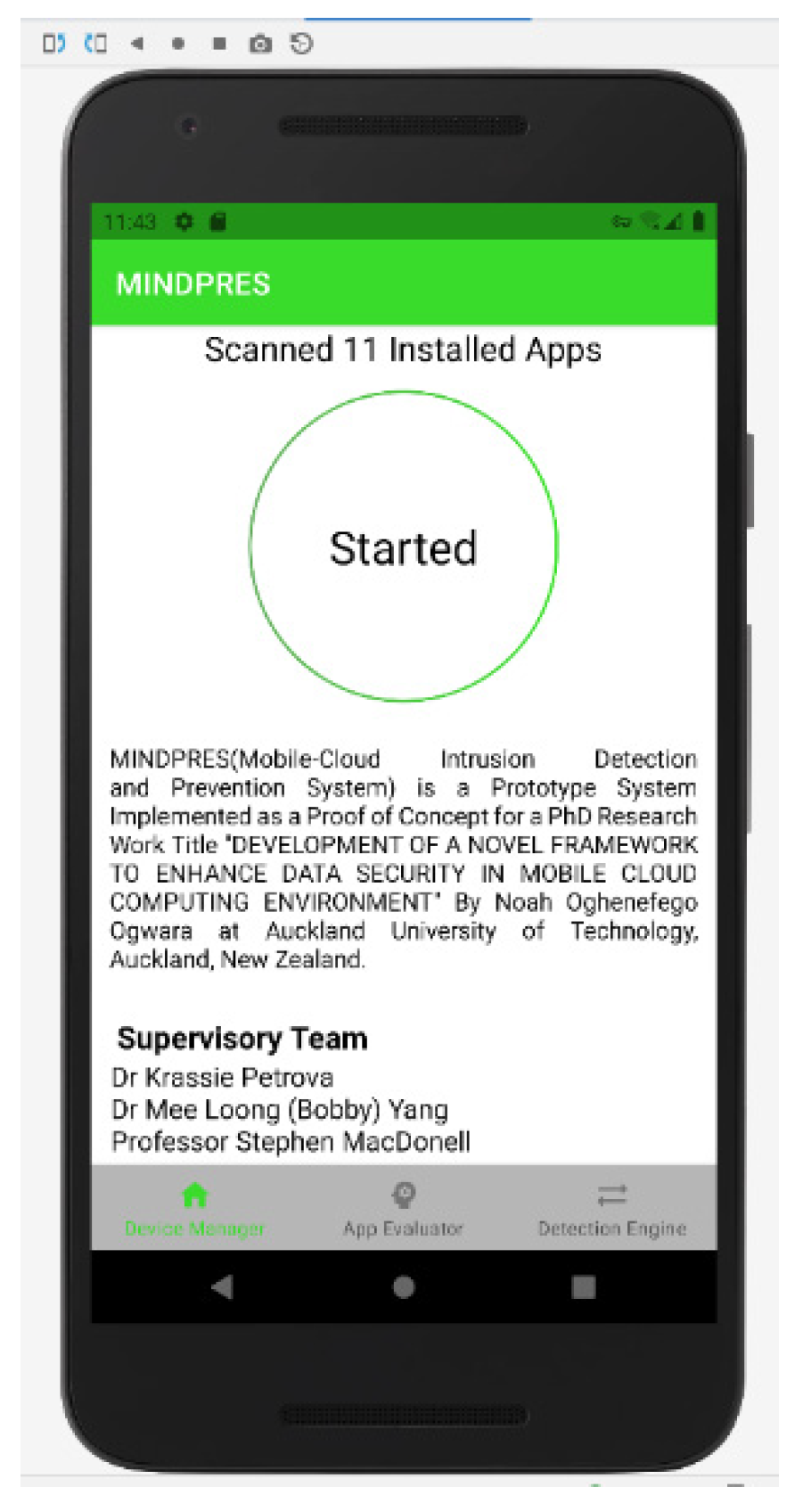

3.1. MINDPRES Prototype Design

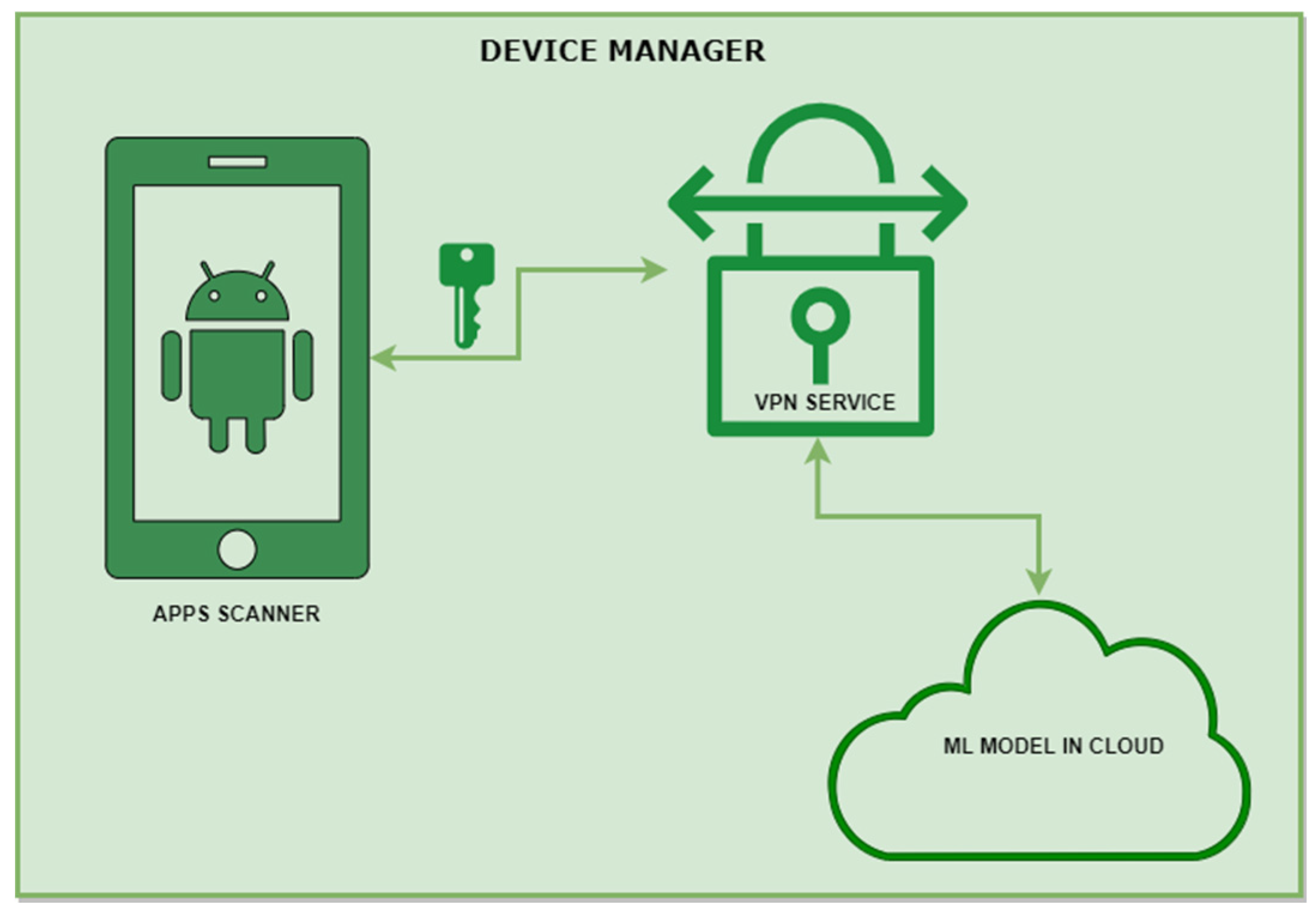

3.1.1. Device Manager

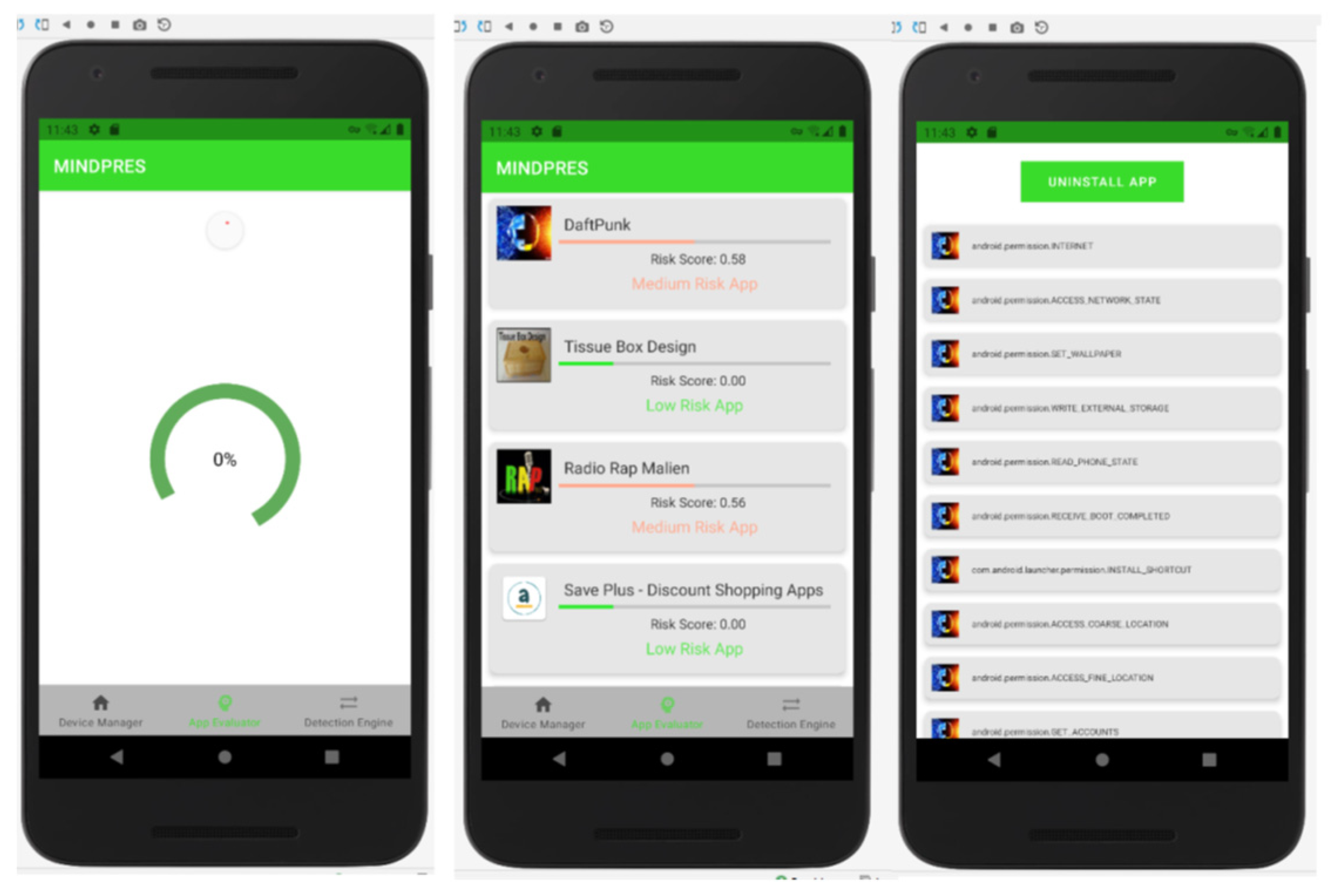

3.1.2. App Evaluator

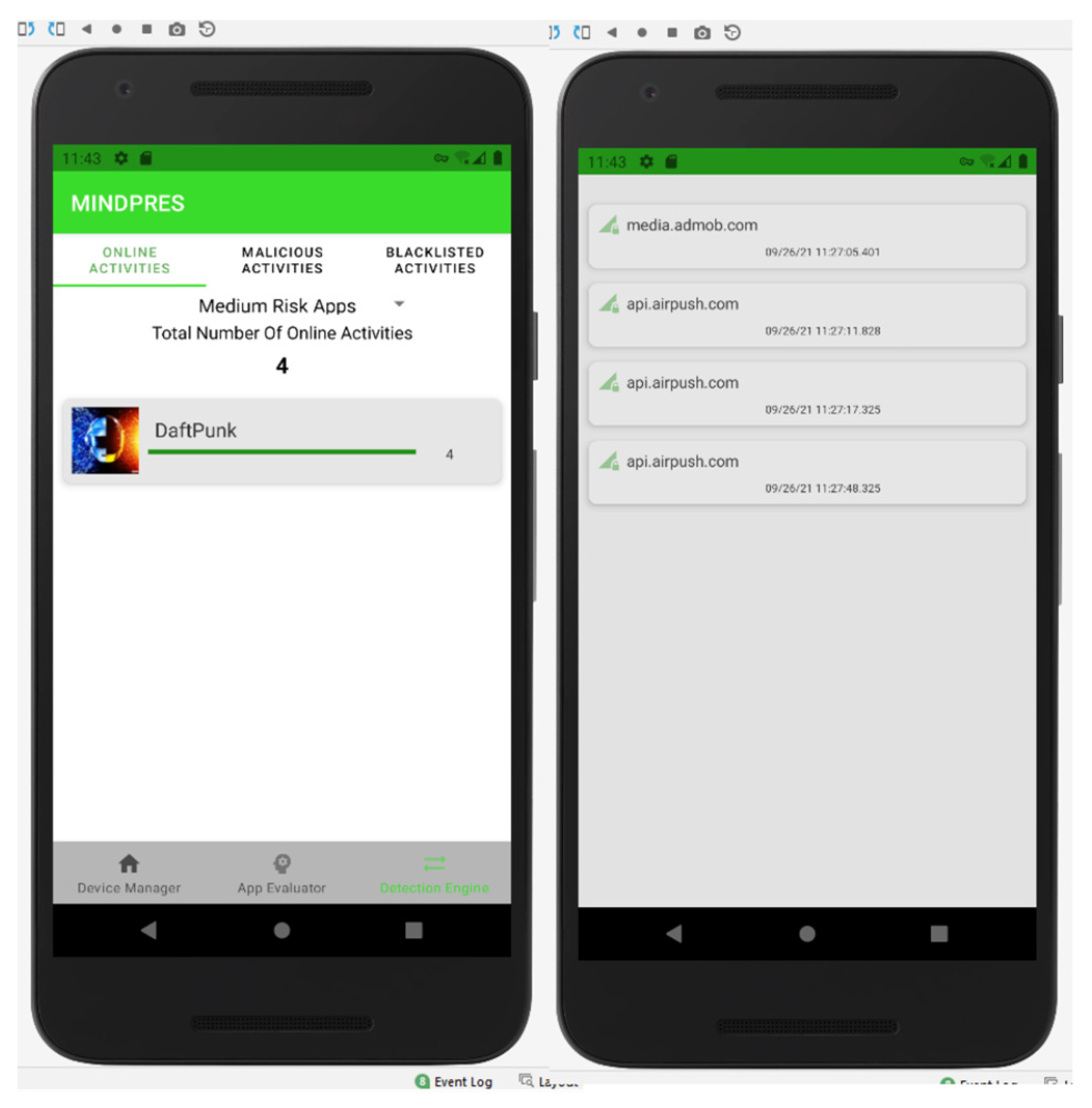

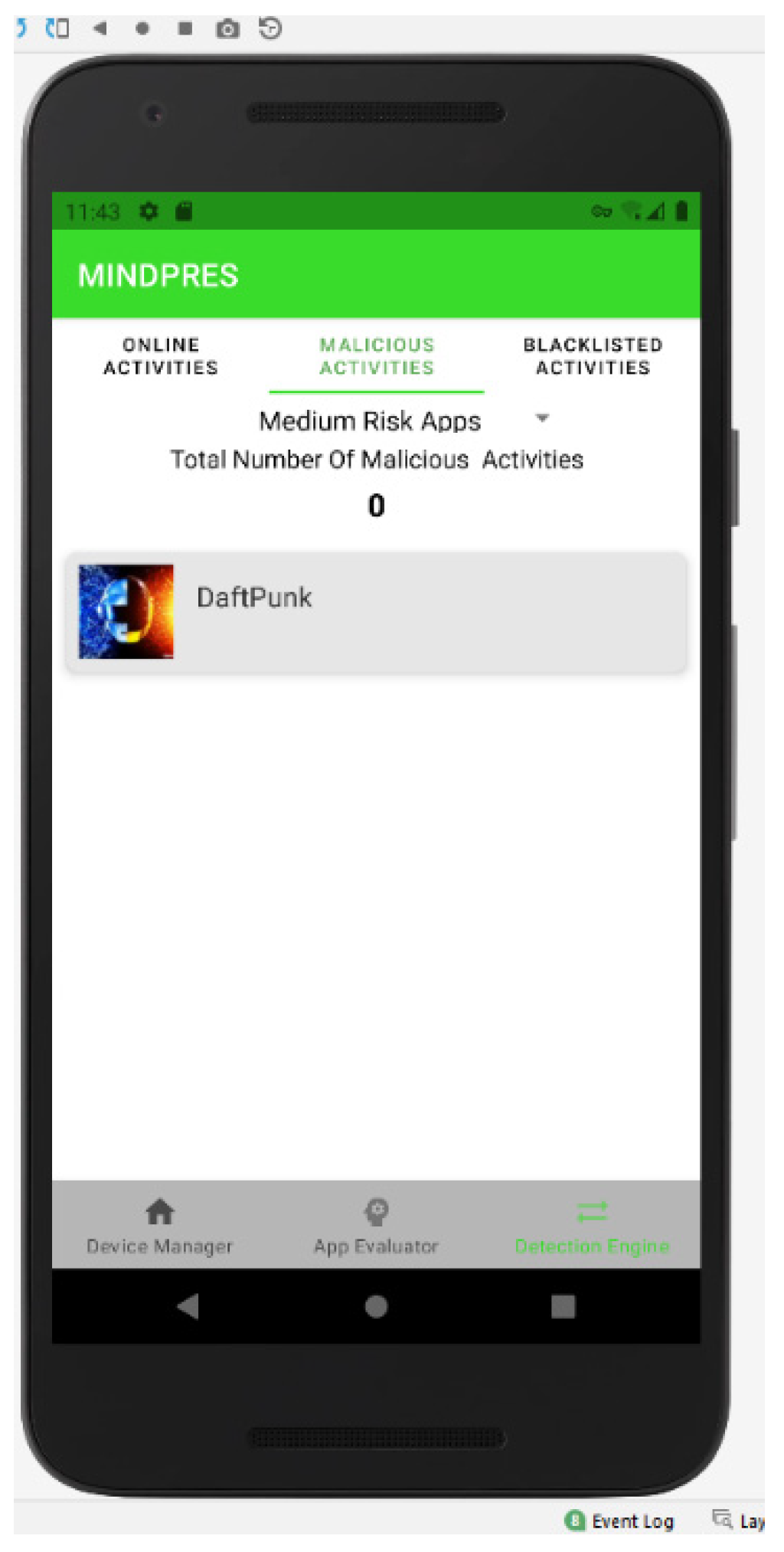

3.1.3. Detection Engine

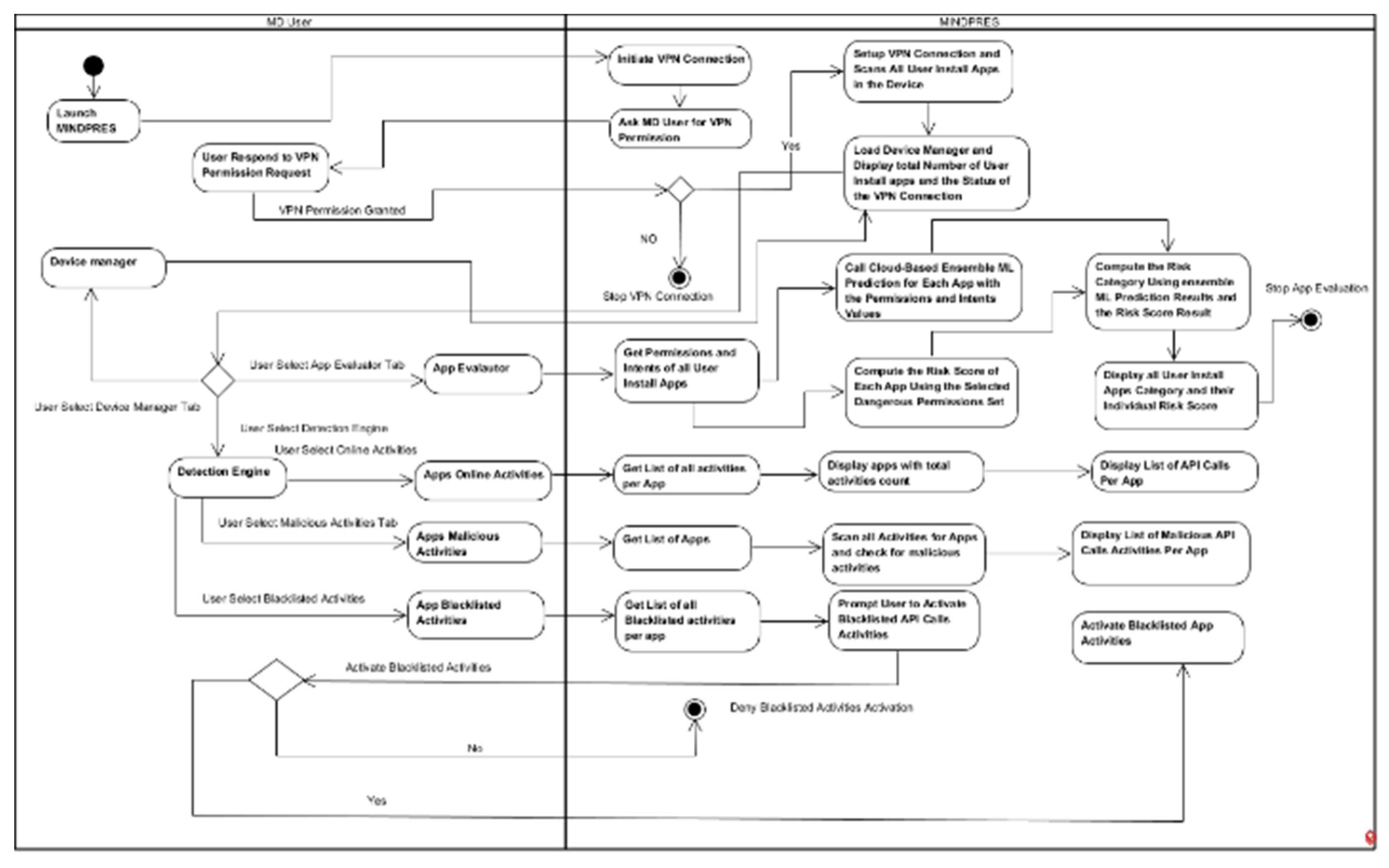

3.1.4. MINDPRES Unified Modelling

3.2. MINDPRES Prototype Implementation and User Interface

3.3. MINDPRES Prototype Evaluation

3.3.1. Experiment Setup

- Adware

- 2.

- Banking Malware:

- 3.

- SMS Malware

- 4.

- Riskware

3.3.2. Testing the App Evaluator

3.3.3. Testing the Detection Engine

3.3.4. Prototype Effectiveness

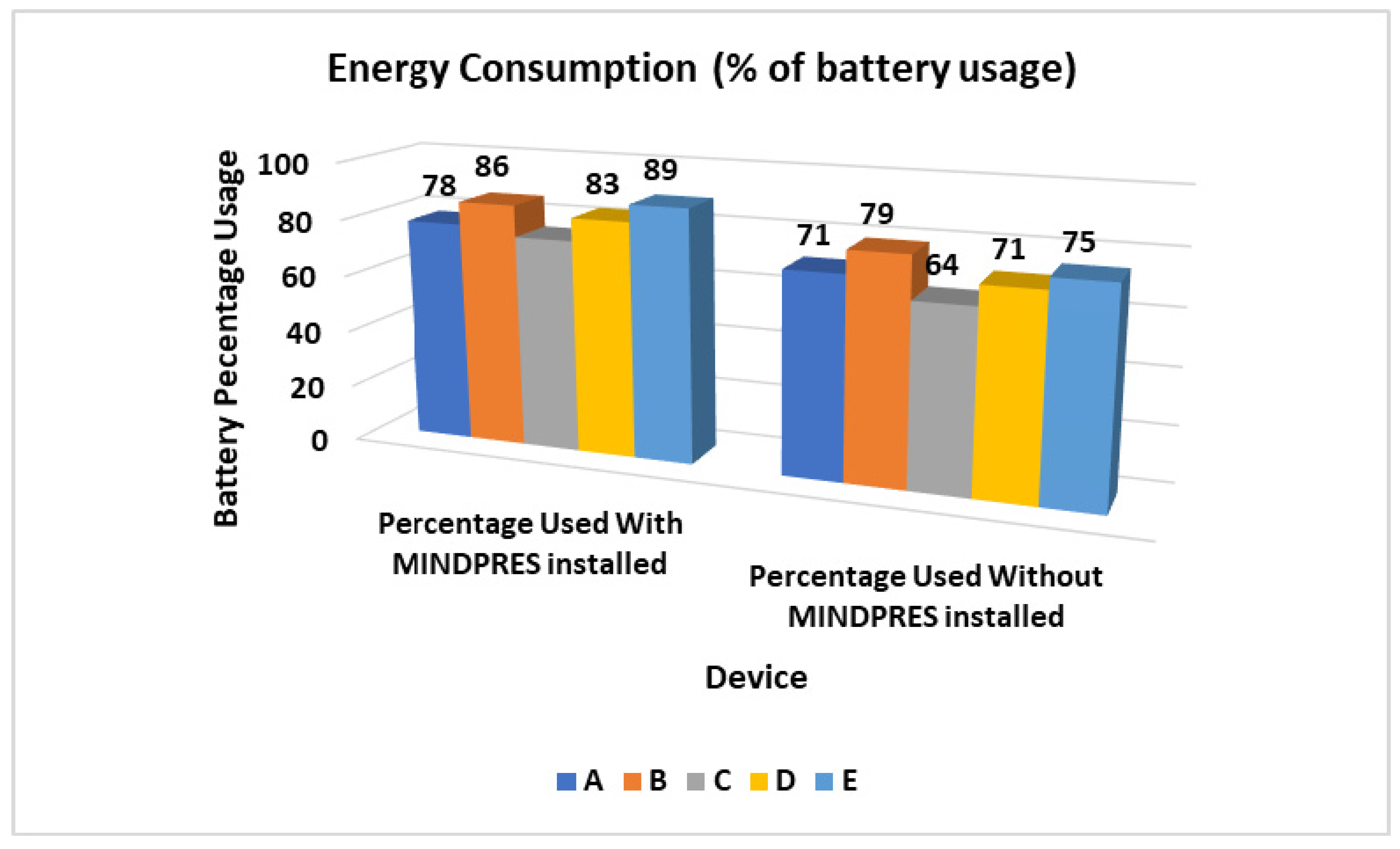

3.3.5. Energy Consumption

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Prior Work

4.2. Study Contributions

4.3. Study Limitations and Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Section A1: Class diagram description

Section A2: Sequence diagram description

Section A3: Activity diagram description

References

- Sharma, M.;Kaul, A. A. Expert Systems 2024,41(1), article 13482.

- Gaber, M.G.; Ahmed, M.;J anicke, H. Malware detection with artificial intelligence: A systematic literature review. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 56 (6), 1-33.

- Noor, T. H.; Zeadally, S.; Alfazi, A.; Sheng, Q. Z. Mobile cloud computing: Challenges and future research directions. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2018, 115, 70-85. [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Ye, Q.; Sampalli, S.A machine learning-based intrusion detection scheme for data fusion in mobile clouds involving heterogeneous client networks. Information Fusion 2019, 49, 205-215. [CrossRef]

- Cinar, A.C.; Kara, T.B. The current state and future of mobile security in the light of the recent mobile security threat reports." Multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82(13), 20269-20281. [CrossRef]

- Wenhua, Z.; Kamrul Hasan, M.; Ismail, A.F.; Yanke, Z.; Razzaque, M.A.; Islam, S.; Anil kumar, B. Data security in smart devices: Advancement, constraints and future recommendations. IET Networks 2023, 12(6),269-281.

- Palma, C.; Ferreira, A.; Figueiredo, M. Explainable machine learning for malware detection on android applications. Information 2024,15(1), 1-25.

- Bostani, H.; Moonsamy, V. Evadedroid: A practical evasion attack on machine learning for black-box android malware detection. Computers & Security 2024 , 139, article 103676.

- Butt, U.A.; Amin, R.; Mehmood, M.; Aldabbas, H.; Alharbi, M.T.; Albaqami, N. Cloud security threats and solutions: A survey."Wireless Personal Communications 2023, 128(1), 387-413. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, M.; Shiaeles, S. An analysis of cloud security frameworks, problems and proposed solutions. Network 2023, 3, 422-450. [CrossRef]

- Nisha, O. J.; Bhanu, S. M. S. Detection of malware applications using social spider algorithm in the mobile cloud computing environment. International Journal of Ad Hoc and Ubiquitous Computing 2020, 34(3), 154-169.

- Mollah, M. B.; Azad, M. A. K.; Vasilakos, A. Security and privacy challenges in mobile cloud computing: Survey and way ahead. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2017, 84, 38-54. [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, A.; Gupta, B.B.; Panigrahi, P.K. A comprehensive survey on machine learning approaches for malware detection in IoTt-based enterprise information system. Enterprise Information Systems 2023, 17(3), article 2023764.

- Alsmadi, A.A.; Shuhaiber, A.; Alhawamdeh, L.N.; Alghazzawi, R.; Al-Okaily, M. Twenty years of mobile banking services development and sustainability: A bibliometric analysis overview (2000–2020). Sustainability 2022, 14(17), article 10630. [CrossRef]

- Saranya, A.; Naresh, R. Efficient mobile security for e-health care application in cloud for secure payment using key distribution. Neural Processing Letters 2023 55(1), 141-152. [CrossRef]

- Naveed, Q.N.; Choudhary, H.; Ahmad, N.; Alqahtani, J.; Qahmash, A.I. Mobile learning in higher education: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2023 ,15 (18), article 13566. [CrossRef]

- AlAhmad, A. S.; Kahtan, H.; Alzoubi, Y. I.; Ali, O.; Jaradat, A. Mobile cloud computing models security issues: A systematic review. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2021, 190, auricle 03152.

- Ribeiro, J.; Saghezchi, F. B.; Mantas, G.; Rodriguez, J.; Shepherd, S. J.; Abd-Alhameed, R. A. (2019). An autonomous host-based intrusion detection system for Android mobile devices. Mobile Networks and Applications 2019, 25, 164-172. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Feng, F.; Shen, Z.; Zhou, R.; Hsieh, M. Y.; Li, K. C. A novel approach for mobile malware classification and detection in Android systems. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2019, 78(3), 3529-3552. [CrossRef]

- John, T.S.; Thomas, T.; Emmanuel, S. Detection of evasive Android malware using EigenGCN. Journal of Information Security and Applications 2024, 86, article 103880.

- Verderame, L.; Ruggia, A.; Merlo, A. Pariot: Anti-repackaging for IoT firmware integrity. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2023, 217, article 103699.

- Casolare, R.; Fagnano, S.;I adarola, G.; Martinelli, F.; Mercaldo, F.; Santone, A. Picker blinder: A framework for automatic injection of malicious inter-app communication. Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques 2024, 20(2), 331-346.

- Shamshirband, S.; Fathi, M.; Chronopoulos, A.T.; Montieri, A.; Palumbo, F.; Pescapè, A. Computational intelligence intrusion detection techniques in mobile cloud computing environments: Review, taxonomy, and open research issues. Journal of Information Security and Applications 2020, 55, article 102582.

- Makhlouf, A.M.; Ghribi, S.; Zarai, F. Layer-based cooperation for intrusion detection in mobile cloud environment. International Journal of Mobile Communications 2023, 21(3), 365-384. [CrossRef]

- Sathupadi, K. A hybrid deep learning framework combining on-device and cloud-based processing for cybersecurity in mobile cloud environments. International Journal of Information and Cybersecurity 2023, 7(12), 61-80.

- Mishra, P.; Jain, T.; Aggarwal, P.; Paul, G.; Gupta, B.B.; Attar, R.W.; Gaurav, A. Cloudintellmal: An advanced cloud based intelligent malware detection framework to analyze Android applications. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2024, 119 , article 109483.

- S, J. N. Detection of malicious Android applications using Ontology-based intelligent model in mobile cloud environment. Journal of Information Security and Applications 2021, 58, article 102751.

- Ogwara, N. O.; Petrova, K.; Yang, M. L. B.; MacDonell, S.G, Enhancing data security in the user layer of mobile cloud computing environment: A novel approach. Advances in Security, Networks, and Internet of Thing. Proceedings from SAM'20, ICWN'20, ICOMP'20, and ESCS'20 , 2021, 129-145.

- Ogwara, N.O.; Petrova, K.; Yang, M.L., MacDonell, S.G. A risk assessment framework for mobile apps in mobile cloud computing environments. Future Internet 2024, 16(8), 271. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Goyal, R. On cloud security requirements, threats, vulnerabilities and countermeasures: A survey. Computer Science Review 2019, 33, 1-48. [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, A.; Singh, S.; Shrivastava, G. Android malware analysis and detection: A systematic review. Expert Systems 2023 (early view, e13488).

- Bhat, P.; Behal, S.; Dutta, K. A system call-based android malware detection approach with homogeneous & heterogeneous ensemble machine learning. Computers & Security 2023, 130, article 103277.

- Roy, S.; Bhanja, S.; Das, A. Andywar: An intelligent android malware detection using machine learning. Innovations in Systems and Software Engineering 2023. [CrossRef]

- Alazab, M.; Alazab, M.; Shalaginov, A.; Mesleh, A.; Awajan, A. Intelligent mobile malware detection using permission requests and API calls. Future Generation Computer Systems 2020, 107, 509-521. [CrossRef]

- Kirubavathi, G.; Anne, W.R. Behavioral based detection of android ransomware using machine learning techniques. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management 2024, 15, 4404-4425. [CrossRef]

- AlJarrah, M.N.; Yaseen, Q.M.; Mustafa, A.M. A context-aware android malware detection approach using machine learning. Information 2022, 13(12), 563. [CrossRef]

- Mahindru, A.; Arora, H.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Mahajan, S.; Kadry, S.; Kim, J. Permdroid a framework developed using proposed feature selection approach and machine learning techniques for android malware detection. Scientific Reports 2024, 14(1), article 10724.

- Maryam, A.; Ahmed, U.; Aleem, M.; Lin, J.C.-W.; Arshad Islam, M.; Iqbal, M.A. Chybridroid: A machine learning-based hybrid technique for securing the edge computing. Security and Communication Networks 2020, 1, article 8861639.

- Shatnawi, A.S.; Jaradat, A.; Yaseen, T.B.;T aqieddin, E.; Al-Ayyoub, M.; Mustafa, D. An android malware detection leveraging machine learning. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2022, 1, article 1830201.

- Aldhafferi, N. Android malware detection using support vector regression for dynamic feature analysis. Information 2024, 15(10), 658. [CrossRef]

- Asmitha, K.; Vinod, P.; KA, R.R.; Raveendran, N.; Conti, M. Android malware defense through a hybrid multi-modal approach. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2024, 233, article 104035.

- Sonya, A.; Deepak, R.R. Android malware detection and classification using machine learning algorithm. International Journal of Communication Networks and Information Security 2024, 16(4) : 327-347.

- Ogwara, N. O.; Petrova, K.; Yang, M. L. B. (2021). MOBDroid2: An Improved Feature Selection Method for Detecting Malicious Applications in a Mobile Cloud Computing Environment. In 2021 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI) (pp. 397-403). IEEE.

- Allix, K.; Bissyandé, T. F.; Klein, J; Le Traon, Y. (2016). Androzoo: Collecting millions of android apps for the research community. In 2016 IEEE/ACM 13th Working Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR) (pp. 468-471). IEEE.

- Wang, H.; Si, J.; Li, H.,; Guo, Y. (2019). Rmvdroid: towards a reliable android malware dataset with app metadata. In 2019 IEEE/ACM 16th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR) (pp. 404-408). IEEE.

- AlOmari, H.; Yaseen, Q.M.; Al-Betar, M.A. A comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms for Android malware detection. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 220,763-768. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.S.; Feng, T. Evaluation of machine learning algorithms for malware detection. Sensors 2023, 23(2), 946. [CrossRef]

- Ogwara, N. O.; Petrova, K.; Yang, M. L. Towards the Development of a Cloud Computing Intrusion Detection Framework Using an Ensemble Hybrid Feature Selection Approach. Journal of Computer Networks and Communications, 2022, article 5988567. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P., & Bagchi, A. (2024). Introduction to Pandas. In Essentials of Python for Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (pp. 161-196). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Mahdavifar, S.;Kadir, A. F. A.;Fatemi, R.; Alhadidi, D.; Ghorbani, A. A. (2020). Dynamic Android Malware Category Classification using Semi-Supervised Deep Learning. In 2020 IEEE Intl Conf on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, Intl Conf on Pervasive Intelligence and Computing, Intl Conf on Cloud and Big Data Computing, Intl Conf on Cyber Science and Technology Congress (DASC/PiCom/CBDCom/CyberSciTech) (pp. 515-522). IEEE.

| Feature ID | Feature name | Permission/Intent |

| F1 | ACCESS_COARSE_LOCATION | Permission |

| F2 | ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION | Permission |

| F3 | ACCESS_LOCATION_EXTRA_COMMANDS | Permission |

| F4 | ACCESS_WIFI_STATE | Permission |

| F5 | BROADCAST_STICKY | Permission |

| F6 | CALL_PHONE | Permission |

| F7 | CHANGE_CONFIGURATION | Permission |

| F8 | CHANGE_NETWORK_STATE | Permission |

| F9 | CHANGE_WIFI_STATE | Permission |

| F10 | DISABLE_KEYGUARD | Permission |

| F11 | GET_ACCOUNTS | Permission |

| F12 | GET_TASKS | Permission |

| F13 | KILL_BACKGROUND_PROCESSES | Permission |

| F14 | MODIFY_AUDIO_SETTINGS | Permission |

| F15 | MOUNT_UNMOUNT_FILESYSTEMS | Permission |

| F16 | READ_CONTACTS | Permission |

| F17 | READ_EXTERNAL_STORAGE | Permission |

| F18 | READ_LOGS | Permission |

| F19 | READ_PHONE_STATE | Permission |

| F29 | READ_SMS | Permission |

| F21 | RECEIVE_BOOT_COMPLETED | Permission |

| F22 | RECEIVE_SMS | Permission |

| F23 | RECORD_AUDIO | Permission |

| F24 | RESTART_PACKAGES | Permission |

| F25 | SET_WALLPAPER | Permission |

| F26 | SYSTEM_ALERT_WINDOW | Permission |

| F27 | VIBRATE | Permission |

| F28 | WAKE_LOCK | Permission |

| F299 | WRITE_EXTERNAL_STORAGE | Permission |

| F30 | WRITE_SETTINGS | Permission |

| F31 | ACTION_BOOT_COMPLETED | Intent |

| F32 | ACTION_PACKAGE_ADDED | Intent |

| F33 | ACTION_PACKAGE_REMOVED | Intent |

| F34 | ACTION_SEARCH | Intent |

| F35 | ACTION_USER_PRESENT | Intent |

| F36 | ACTION_VIEW | Intent |

| F37 | CATEGORY_BROWSABLE | Intent |

| F38 | CATEGORY DEFAULT | Intent |

| F39 | CATEGORY _HOME | Intent |

| ID | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Decision Tree | Uses a tree structure to solve a specific problem. The leaf node in the tree represents a class label. |

| C2 | Random Forest | Consists of multiple decision trees that learn independently The outcome is determined by the most frequently occurring classification . |

| C3 | AdaBoost | Uses an iterative approach to create a stronger classifier at each next iteration. |

| C4 | Naïve Bayes | Applies a probabilistic approach: computes the probability of the possible outcomes and selects the class with the highest probability. |

| C5 | Stochastic Dual Coordinate Ascent | An iterative, fast converging optimization method.. |

| C6 | Multi-layer Perceptron | An artificial neural network (ANN) feedforward model with at least three layers (input, one or more hidden, output). Uses a non-linear mapping of the input vectors to a specific output vector. |

| C7 | K-nearest Neighbors | Measures the distance between the test sample and the training samples and uses a majority voting to predict the outcome. |

| C8 | Linear Discriminant Analysis | Combines variables to find a linear combination that best differentiates between groups and predicts s based on the maximum probabilistic allocation of the class labels . |

| C9 | Logistic Regression | Uses a statistical model that uses a logistic curve to fit the training dataset. Finds the probability that a given instance of an input set belongs to a specific class. |

| C10 | Support Vector Machine | Maps each input feature into an n-dimensional feature space such that n is the total number of features. Identifies the hyperplane that separates each input feature into two different classes while maximizing the marginal distance for the classes and reducing the classification errors. |

| Metric | Definition |

|---|---|

| TP (true positive) | The number of malicious samples correctly classified as malicious |

| TN (true negative) | The number of non-malicious (i.e., benign) samples correctly classified as non-malicious (i.e., benign) |

| FP (false positive) | The number of non-malicious (i.e., benign ) samples wrongly classified as malicious |

| FN (false negative) | The number of malicious samples wrongly classified as not malicious (i.e., benign) |

| CA (classification accuracy) | The percentage of the correctly classified malicious and benign samples out of all samples in the test dataset |

| ER (error rate) | The percentage of all wrongly classified benign and malicious samples out of all samples in the test dataset |

| PR (precision rate) | The percentage of all samples correctly classified as malicious out of all samples that were classified as malicious |

| RC (recall rate) | The percentage of all samples correctly classified as malicious out of all malicious samples in the test dataset |

| FPR (false positive rate) | The percentage of all benign samples classified wrongly as malicious out of all benign samples in the test dataset |

| FNR (false negative rate) | The percentage of all malicious samples classified wrongly as benign out of all malicious samples in the test dataset |

| FAR (false alarm rate) | The average percentage of all samples that were misclassified |

| FM (F-measure) | The harmonic mean of the classifier |

| ML Model | TP | FP | TN | FN | CA | ER | PR | RC | FM | FPR | FNR | FAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble (C1, C2, C7) | 3,598 | 43 | 1,958 | 63 | 98.13 | 1.87 | 98.82 | 98.28 | 98.55 | 2.15 | 1.72 | 1.93 |

| C1 | 3,421 | 185 | 1,816 | 240 | 92.78 | 7.22 | 95.29 | 93.44 | 94.36 | 8.45 | 6.56 | 7.50 |

| C2 | 3,496 | 174 | 1,827 | 165 | 94.00 | 6.00 | 95.58 | 95.11 | 95.35 | 8.05 | 4.89 | 6.47 |

| C7 | 3,484 | 201 | 1,800 | 177 | 93.50 | 6.50 | 94.80 | 95.17 | 94.98 | 9.55 | 4.83 | 7.19 |

| Dangerous permission ID | Dangerous permission name |

|---|---|

| P1 | WRITE EXTERNAL STORAGE |

| P2 | READ PHONE STATE |

| P3 | ACCESS COARSE LOCATION |

| P4 | ACCESS FINE LOCATION |

| P5 | GET TASKS |

| P6 | READ EXTERNAL STORAGE |

| P7 | SYSTEM ALERT WINDOW |

| P8 | READ LOGS |

| P9 | MOUNT UNMOUNT FILESYSTEMS |

| P10 | CAMERA |

| P11 | RECORD AUDIO |

| P12 | GET ACCOUNTS |

| P13 | CALL PHONE |

| P14 | WRITE SETTINGS |

| P15 | SEND SMS |

| Static Classification ML Model outcome for app a | R(a) (Risk Sore of App a) | Risk category of App a |

|---|---|---|

| App a classified as malicious | R(a) belongs to the interval [0, t1] | Low risk |

| R(a) belongs to the interval (t1, t3] | Medium risk | |

| R(a) belongs to the interval (t3, 1] | High risk | |

| App a classified as benign | R(a) belongs to the interval [0, t2] | Low risk |

| R(a) belongs to the interval (t2, t4] | Medium risk | |

| R(a) belongs to the interval (t4, 1] | High risk |

| Emulator | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign Apps | 3,578 | 3,099 | 4,329 | 2,988 | 4,005 | 3,021 | 3,566 | 5,002 | 39,44 | 2,991 | 36,523 |

| Malicious Apps | 4,024 | 5,600 | 5,023 | 3,456 | 3,878 | 4,098 | 5,008 | 3,207 | 3,456 | 4,012 | 41762 |

| Total recorded | 7,602 | 8,699 | 9,352 | 6,444 | 7,883 | 7,119 | 8,574 | 8,209 | 7,400 | 7,003 | 78,285 |

| ID | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Protocol | Network communication protocol requested |

| C2 | Duration | The duration of the connection between the host MD and the destination host |

| C3 | Domain URL | The URL of the destination host that services the API call |

| C4 | Packets Sent | The number of packets sent from the host MD |

| C5 | Packets Received | The number of packets received from the destination host |

| C6 | Destination IP | The IP address of the destination host |

| C7 | Source Bytes | The total size of data sent from the host MD (source) |

| C8 | Destination Bytes | The total size of data received from the destination host |

| Steps | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Let VPNStatus =0 and Initialize VPN Service Connection and Prompt User for permission to monitor all apps |

| Step 2 | IF VPN Service Connection is granted by the user, Then Go to Step 3 Otherwise Go to Step |

| Step 3 | Setup VPN Service Connection for the Device and Set VPNStatus=1 (Ready) |

| Step 4 | Scanned all Apps that are Installed by the User and Set Array DefaultAppList to AllUserInstallApps |

| Step 5 | Let AppsCount = number of records in array DefaultAppList and Set TotalUserInstallApps = AppsCount |

| Step 6 | Stop VPN Service Connection and Set VPNStatus=0 |

| Step 7 | End of IF structure in Step 2 |

| Step 8 | OUTPUT: VPNStatus, TotalUserInstallApps |

| Step 9 | Exit |

| Steps | Description |

|---|---|

| INPUT | DangerousPermissionList, EnsemblePermissionIntentList, PermissionRiskValue |

| Step 1 | For Each App X in DefaultAppList repeat step 2, 3, 4,5, and 6 |

| Step 2 | Extract the Permission and Intent demanded by app X contained in the Features Listed in EnsemblePermissionIntentList as appPermissionIntentList and Set array PI = appPermissionIntentList |

| Step 3 | Extract the dangerous Permission demanded by app X contained in the Features Listed in DangerousPermissionList as appDangerousPermissionList and Set array DP = appDangerousPermissionList |

| Step 4 | Compute the RiskScore of app X with the selected dangerous permission in DP and Extract the Permission Risk Value for each permission contained in PermissionRiskValue that exists in DP |

| Step 5 | Get the result of the ensemble ML prediction for app X using the features extracted from Step 2 in array PI and store the result return in a variable MLResult as integer (0 is benign and 1 is malicious) |

| Step 6 | IF RiskScore in Step 4 is greater than or equal to 0.75 and MLResult=0 Then Set RiskCategory to “High Risk App” and go to Step 12 Otherwise go to step 7 |

| Step 7 | IF RiskScore in Step 4 is greater than or equal to 0.50 and MLResult=0 Then Set RiskCategory to “Medium Risk App” and go to Step 12 Otherwise go to step 8 |

| Step 8 | IF RiskScore in Step 4 is greater than or equal to 0.00 and MLResult=0 Then Set RiskCategory to “Low Risk App” and go to Step 12 Otherwise go to step 9 |

| Step 9 | IF RiskScore in Step 4 is greater than or equal to 0.65 and MLResult=1 Then Set RiskCategory to “High Risk App” and go to Step 12 Otherwise go to step 10 |

| Step 10 | IF RiskScore in Step 4 is greater than or equal to 0.25 and MLResult=1 Then Set RiskCategory to “Medium Risk App” and go to Step 12 Otherwise go to step 11 |

| Step 11 |

Set RiskCategory to “Low Risk App” and go to Step 12 End of If Structure in Step 6 |

| Step 12 | OUTPUT RiskScore, RiskCategory |

| Step 13 | End of Step 1 For -Loop |

| Step 14 | Exit |

| Steps | Description |

|---|---|

| Var | Array<string>: AppsActivities, MaliciousAppsTraffic, BlackListedAppsTraffic |

|

INPUT |

VPNStatus, EnsemblePermissionIntentList, TrafficDataList, DefaultAppTrafficList |

| Step 1 | IF VPNStatus =1 Then Go to Step 2 Otherwise Go to Step 16 |

| Step 2 | For Each App X in DefaultAppList repeat step 3, 13 and 14 |

| Step 3 | For Each Traffic Data of App X in DefaultAppTrafficList repeat step 4,5, 6,7,8,9, and 10 |

| Step 4 | Extract the Permissions and Intents demanded by app X at run-time whenever an online Request is made contained in the Features Listed in EnsemblePermissionIntentList as appPermissionIntentList and Set array PI =appPermissionIntentList |

| Step 5 | Extract the Traffic Network Data by app X contained in the Features Listed in TrafficDataList as appTrafficData and Set array TD =appTrafficData and add Traffic data for app x in array AppsActivities |

| Step 6 | Extract the URL call by app X contained in the TrafficDataList as appTrafficURL and Set array TURL =appTrafficURL |

| Step 7 | Construct App network traffic dataset from TD in step 5 and PI in step 4 and set AppTrafficMLData as the new dataset for each traffic request consisting of API calls, Permissions, and Intent |

| Step 8 | Get the result of the ensemble ML prediction for app X using the features constructed from Step 7 in array AppTrafficMLData and store the result return in a variable MLTrafficResult as integer (0 is benign and 1 is malicious) |

| Step 9 | Get the result of the Malicious Global Database scanner for app X using the URL extracted from Step 6 in array TURL and store the result return in a variable URLTrafficResult as integer (0 is benign and 1 is malicious) |

| Step 10 | IF MLTrafficResult =1 OR URLTrafficResult =1Then ADD the traffic data inTDfrom step 5 for app X toMaliciousAppsTrafficand also automatically block TD and ADD toBlackListedAppsTraffic for app X and go to Step 11 Otherwise go to step 12 |

| Step 11 | End of If Structure in Step 10 |

| Step 12 | End of Inner For-Loop in Step 3 |

| Step 13 | Set TotalAppActivites = Total Number of Records in AppsActivities in Step 5 Set TotalMaliciousAppActivites= Total Number of Records in MaliciousAppsTraffic in Step 10 Set TotalBlacklistedAppActivites= Total Number of Records in BlackListedAppsTraffic in Step 10 |

| Step 14 | OUTPUT: TotalAppActivites, TotalMaliciousAppActivites, TotalBlacklistedAppActivites, AppsActivities, MaliciousAppsTraffic, BlackListedAppsTraffic for app X. |

| Step 15 | End of Outer For -Loop in Step 2 |

| Step 16 | Exit |

| Device | Benign apps | Malicious apps |

|---|---|---|

| Device A: EE Tablet HTC Nexus 9.8.9, 1.8GB RAM 32GB Internal storage | 240 | 200 |

| Device B: Samsung Galaxy Tab A (SM-T380) 2GB RAM, 16GB Internal storage | 90 | 50 |

| Device C: Samsung Galaxy Tab A (SM-T380) 2GB RAM, 16GB Internal storage | 90 | 50 |

| Device D: Samsung Galaxy Tab A (SM-T380) 2GB RAM, 16GB Internal storage | 90 | 50 |

| Device E: Samsung Galaxy Tab A (SM-T380) 2GB RAM, 16GB Internal storage | 90 | 50 |

| Total | 600 | 400 |

| App Category | Total | Average Downloads | Device | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | Watch | 30 | 95 million | A |

| B2 | Art & Design | 30 | 21 million | |

| B3 | Beauty | 30 | 1 million | |

| B4 | Business | 30 | 100 million | |

| B5 | Communication | 30 | 200 million | |

| B6 | Education | 30 | 20 million | |

| B7 | Events | 30 | 1 million | |

| B8 | Food and Drink | 30 | 10 million | |

| B9 | Shopping | 30 | 50 million | B |

| B10 | Social | 30 | 500 million | |

| B11 | News & Magazines | 30 | 5 million | |

| B12 | Finance | 30 | 10 million | C |

| B13 | Entertainment | 30 | 100 million | |

| B14 | Lifestyle | 30 | 10 million | |

| B15 | Music & Audio | 30 | 50 million | D |

| B16 | Maps & Navigation | 30 | 10 million | |

| B17 | Travel and Local | 30 | 1 million | |

| B18 | Tools | 30 | 10 million | E |

| B19 | Sports | 30 | 10 million | |

| B20 | Dating | 30 | 10 million | |

| App Category | Total | Device | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Adware | 100 | A |

| M2 | Banking Malware | 100 | A |

| M3 | SMS Malware | 50 | B |

| M4 | SMS Malware | 50 | C |

| M5 | Mobile Riskware | 50 | D |

| M6 | Mobile Riskware | 50 | E |

| Testbed Apps | Number of app classified | Number of Apps Evaluated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As Benign | As Malicious | As Low Risk | As Medium Risk | As High Risk | |

| B1 (30) | 30 | 0 | 29 | 1 | 0 |

| B2 (30) | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| B3 (30) | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| B4 (30) | 28 | 2 | 28 | 2 | 0 |

| B5 (30) | 27 | 3 | 27 | 3 | 0 |

| B6 (30) | 28 | 2 | 28 | 1 | 1 |

| B7 (30) | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| B8 (30) | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| B9 (30) | 26 | 4 | 26 | 3 | 1 |

| B10 (30) | 25 | 5 | 25 | 5 | 0 |

| B11 (30) | 28 | 2 | 26 | 4 | 0 |

| B12 (30) | 29 | 1 | 29 | 1 | 0 |

| B13 (30) | 29 | 1 | 29 | 1 | 0 |

| B14 (30) | 29 | 1 | 28 | 2 | 0 |

| B15 (30) | 27 | 3 | 27 | 3 | 0 |

| B16 (30) | 28 | 2 | 28 | 2 | 0 |

| B17 (30) | 29 | 1 | 29 | 1 | 0 |

| B18 (30) | 28 | 2 | 28 | 2 | 0 |

| B19 (30) | 28 | 2 | 27 | 3 | 0 |

| B20 (30) | 29 | 1 | 29 | 1 | 0 |

| M1 (100) | 7 | 93 | 0 | 73 | 27 |

| M2 (100) | 3 | 97 | 0 | 85 | 15 |

| M3 (50) | 4 | 46 | 2 | 35 | 13 |

| M4 (50) | 2 | 48 | 0 | 30 | 20 |

| M5 (50) | 3 | 47 | 0 | 38 | 12 t |

| M6 (50) | 1 | 49 | 1 | 33 | 16 |

| Testbed Apps | Low Risk | Medium Risk | High Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| B1 (Watch) | 96.67% | 3.33% | 0.00% |

| B2 (Art and Design) | 100.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| B3 (Beauty) | 100.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| B4 (Business) | 93.33% | 6.67% | 0.00% |

| B5 (Communication) | 90.00% | 10.00% | 0.00% |

| B6 (Education) | 93.33% | 3.33% | 3.33% |

| B7 (Events) | 100.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| B8 (Food and Drink) | 100.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| B9 (Shopping) | 86.67% | 10.00% | 3.33% |

| B10 (Social) | 83.33% | 16.67% | 0.00% |

| B11 (News & Magazines) | 86.67% | 13.33% | 0.00% |

| B12 (Finance) | 96.67% | 3.33% | 0.00% |

| B13 (Entertainment) | 96.67% | 3.33% | 0.00% |

| B14 (Lifestyle) | 93.33% | 6.67% | 0.00% |

| B15 (Music & Audio) | 90.00% | 10.00% | 0.00% |

| B16 (Maps & Navigation) | 93.33% | 6.67% | 0.00% |

| B17 (Travel and Local) | 96.67% | 3.33% | 0.00% |

| B18 (Tools) | 93.33% | 6.67% | 0.00% |

| B19 (Sports) | 90.00% | 10.00% | 0.00% |

| B20 (Dating) | 96.67% | 3.33% | 0.00% |

| M1 (Adware) | 0.00% | 73.00% | 27.00% |

| M2 (Banking Malware) | 0.00% | 85.00% | 15.00% |

| M3 (SMS Malware) | 3.70% | 64.81% | 31.48% |

| M4 (SMS Malware) | 0.00% | 65.22% | 34.78% |

| M5 (Mobile Riskware) | 0.00% | 70.37% | 29.63% |

| M6 (Mobile Riskware) | 2.17% | 71.74% | 26.09% |

| Device | Actual App Type | Activities When Device In Use |

Activities When Device Idle |

Number of Malicious Activities |

Number of Apps Performing Malicious Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Benign | 1,978 | 597 | 13 | 6 |

| B | Benign | 899 | 215 | 5 | 2 |

| C | Benign | 768 | 198 | 2 | 1 |

| D | Benign | 987 | 231 | 7 | 3 |

| E | Benign | 1,204 | 149 | 4 | 2 |

| A | Malicious | 2,876 | 459 | 1,781 | 187 |

| B | Malicious | 768 | 202 | 571 | 48 |

| C | Malicious | 1,377 | 599 | 650 | 45 |

| D | Malicious | 1,422 | 231 | 679 | 49 |

| E | Malicious | 1009 | 456 | 752 | 42 |

| Device | Analysis | TP | FP | TN | FN | CA | ER | PR | RC | FM | FPR | FNR | FAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Static | 190 | 7 | 233 | 10 | 96.14 | 3.86 | 96.45 | 95.00 | 95.72 | 2.92 | 5.00 | 3.96 |

| Dynamic | 187 | 6 | 234 | 13 | 95.68 | 4.32 | 96.89 | 93.50 | 95.17 | 2.50 | 6.50 | 4.50 | |

| B | Static | 46 | 4 | 86 | 4 | 94.29 | 5.71 | 92.00 | 92.00 | 92.00 | 4.44 | 8.00 | 6.22 |

| Dynamic | 48 | 2 | 88 | 2 | 97.14 | 2.86 | 96.00 | 96.00 | 96.00 | 2.22 | 4.00 | 3.11 | |

| C | Static | 48 | 3 | 87 | 2 | 96.43 | 3.57 | 94.12 | 96.00 | 95.05 | 3.33 | 4.00 | 3.67 |

| Dynamic | 45 | 1 | 89 | 5 | 95.71 | 4.29 | 97.83 | 90.00 | 93.75 | 1.11 | 10.00 | 5.56 | |

| D | Static | 47 | 6 | 84 | 3 | 93.57 | 6.43 | 88.68 | 94.00 | 91.26 | 6.67 | 6.00 | 6.33 |

| Dynamic | 49 | 3 | 87 | 1 | 97.14 | 2.86 | 94.23 | 98.00 | 96.08 | 3.33 | 2.00 | 2.67 | |

| E | Static | 49 | 5 | 85 | 1 | 95.71 | 4.29 | 90.74 | 98.00 | 94.23 | 5.56 | 2.00 | 3.78 |

| Dynamic | 42 | 2 | 88 | 8 | 92.86 | 7.14 | 95.45 | 84.00 | 89.36 | 2.22 | 16.00 | 9.11 |

| Source and Approach | Features and Datasets | Sample Size | ML Algorithm | Performance Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study: Static | Featureas: P, I Datasets: AZ, RD |

B: 9,879 M: 18,427 |

Ensemble (DT, RF, KNN) | CA= 98.13% FM= 98.55% FPR =2.15% |

| This study: Hybrid | Features: P, I, A, NT Datasets: AZ, RD, CMD2020, GP |

B: 9,879 +600 M: 18,427+400 |

Ensemble (DT, RF, KNN) and RF | (best result) CA= 97.14% FM= 96.08% FPR= 1.11% |

| [18]: Dynamic | Features: DR Datasets: GP |

B: 6,000 M: 6,000 |

DT | CA=99.80% |

| [19]: Dynamic | Features: SC Datasets: BM, VSH |

Not Reported | MCA | CA=97.85% PR=98.70% FPR=4.21% |

| [34]: Dynamic | Features: P, A Datasets: AZ |

B: 14,172 M: 13,719 |

RF | FM=94.3% |

| [38]: Hybrid | Features: P, I, NT, IL, CR Datasets: DB, GP |

B: 2,500 N:2,500 |

RF, NB, SVM, DT, K* | FM=97% |

| [27]: Static | Features: P Datasets: AZ, VSH |

B: 1,959 M: 2,113 |

RF | CA=94.11% FM=93.00% FPR=.00% |

| [36]: Static | Features: A, P, CF Datasets: CMD2020 |

B: 4,100 M: 12,800 | RF, LR, SVM, KNN, DT | CA=99.4% |

| [39]: Hybrid | Features: P, AR Datasets: PAN |

M: 104,747 B: 90,876) |

GB, XGB, DT, RF | GB: CA= 99.7% FM= 99.8%; XGB: CA=99.8% FM: 99.8% DT: CA=99.5%, FM=99.6% RF: CA= 97.4%, FM: 97.9% |

| [32]: Dynamic | Features: SC, BC, NT Datasets: CMD2020 |

B: 1795 M: 9803 |

SVM, NB, LR, DT, RF |

CA= 98.08% |

| [33]: Dynamic |

Features: SC, BC, NT Datasets: CAM2017, CMD2020 |

Not specified | Ensemble (KNN, SVM,LR, DT) | CAM2017: FM=97.23% CMD2020: FM=97.57% |

| [40]: Hybrid | Features: SC, A, NT Datasets: AMDD |

B: 9,045 M: 3,233 |

SVR | CA= 95.74% FM= 96.38% |

| [41]: Hybrid | Features: P, I, SC, CF Datasets: DR, AZ, CMD2022 |

DR: ( B:7,121; M:3783) AZ: (B:7,121, M:3,483) CMD2020: (B:1795; M:9,803 |

DNN, SVM, RF, KNN | CA=99.97% FM=99.97% |

| [35]: Static | Features: P, SC Datasets: 28-SABD |

B: 3,628 M: 3,572 |

DT, RF, ET, LGBM | CA=98.05% |

| [37]: Static | Features: P, A, APR, APD Datasets: GP, ST, AA, CNET, SDD |

B:70,000 M:70, 000 |

Three ML classifiers, neural network | (Best) AC=98.80% |

| [42]: Hybrid | Features: P, A, NT, SC Datasets: CAM2017 |

B: 298,087 M:104,747 |

GBT, RC | GBT: CA=93.50% RC: CA= 83% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).