1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the most frequent tumors affecting women worldwide; with over half a million new cases diagnosed annually. It is the fourth most common cancer in women, and the second most frequent in ages from 15 to 44 years old [

1]. Its development is mainly influenced by HPV infection, so its prevalence is highly variable, with important differences according to the grade of development of the countries [

2]. Access to HPV vaccination, an adequate screening program and treatment of pre-malignant disease are the main factors that cause important differences regarding incidence among countries [

3]. These factors cause that, in some countries, its incidence becomes higher than endometrial or ovarian cancer.

Cervical cancer may affect patients of a broad age range, so it is not rare its diagnosis in young patients. This fact, added to the current increase of the maternity age, makes necessary the development of new treatments that may enable, in selected cases, the preservation of fertility on the patients that wish to.

Surgery is the standard treatment for early-stage cervical cancer, although radiotherapy can be considered in some cases, with equal results [

4]. Nonetheless, surgery is usually chosen as the standard treatment because its morbidity is lower and it provides a histological examination that allows the obtainment of prognostic factors; radiotherapy as treatment for early-stage tumors is not frequently used. Radiotherapy is more often used as adjuvant treatment in selected high- risk patients after surgery or as primary treatment with concomitant chemotherapy in advanced- stage tumors.

When the tumor is amenable for surgery, its extension and, therefore, radicality, is based on FIGO stage. Stage IA1 with no invasion of lymph vascular space may be treated by a cervical conization or single hysterectomy [

5]; in the remaining surgical stages, the standard treatment consists on radical hysterectomy. Surgery for cervical cancer includes dissection and removal of both parametrium, since cervical cancer tends to spread through the parametrial tissue. The degree of radicality needed is also based on FIGO stage.

Despite the higher or lower grade of parametrial radicality needed, standard radical surgery for cervical cancer includes the removal of the uterine body along with the cervix, entailing the loss of fertility, so other treatments have been considered in order to allow the accomplishment of childbearing wishes.

Radical trachelectomy consists on the removal of the cervix and the parametrium with the preservation of the uterine body and its suture to the vaginal cuff. This surgical procedure was first described by Eugen Aburel in the 1950s, not being used anymore until a French group headed by Dargent started to perform it again in 1994 [

6]. This surgery can either have vaginal or abdominal approach; the abdominal approach includes laparotomy, laparoscopy and robotics. Radical trachelectomy is indicated when an early-stage cervical tumor is diagnosed in a young patient with desire of fertility sparing. In addition to those requirements, some other criteria need to be taken into account, as histological type, tumor size and

absence of lymph node and metastatic disease.

Robotic surgery is known, among others, to ease an improved dexterity and higher rates for instrument movement and a three-dimensional view, in addition to ergonomic and tremor less, which may help to preserve important adjacent structures without compromising the mandatory oncological radicality [

7].

Many studies have been published about fertility sparing surgery for cervical cancer, but few of them describe robotic radical trachelectomy; furthermore, they include a small number of patients and a yet short follow- up time. The experience of robotic surgery in non-fertility- sparing procedures for cervical cancer is bigger; studies comparing vaginal and abdominal approach, including laparotomic, laparoscopic and robotic, showed no important differences between vaginal or abdominal minimally invasive surgery (MIS) regarding oncological safety, mean operating time, perioperative or postoperative complications [

8]. On the other hand, laparotomic surgery has a similar rate of recurrences but with a higher number of complications. Nonetheless, LACC study postulates an opposite theory, showing lower rates of disease- free survival and overall survival when a laparoscopic or robotic radical hysterectomy is performed, compared to laparotomic approach [

9]. Since these results were unexpected, shortly after their release, some other studies were carried out in order to clarify if MIS actually increased risk for recurrence. IRTA study was published in 2022, and aimed to compare open vs. MIS radical trachelectomy; no differences in prognosis were found in these study [

10].

Our objective is not only to add to literature new cases of robotic radical trachelectomy, with a longer follow- up time, but to compare the so far published data with our own data, in order to prove feasibility and safety of robotic radical trachelectomy as fertility sparing surgery.

2. Material and Methods

Seven patients that underwent robotic radical trachelectomy from 2013 to 2022 at Hospital Clinico San Carlos were analyzed. They were all young patients with early-stage cervical cancer and wished fertility preservation. They were explained that it was not the standard procedure; moreover, they all fulfilled inclusion criteria and signed a consent form. The study was approved by the local ethic committee.

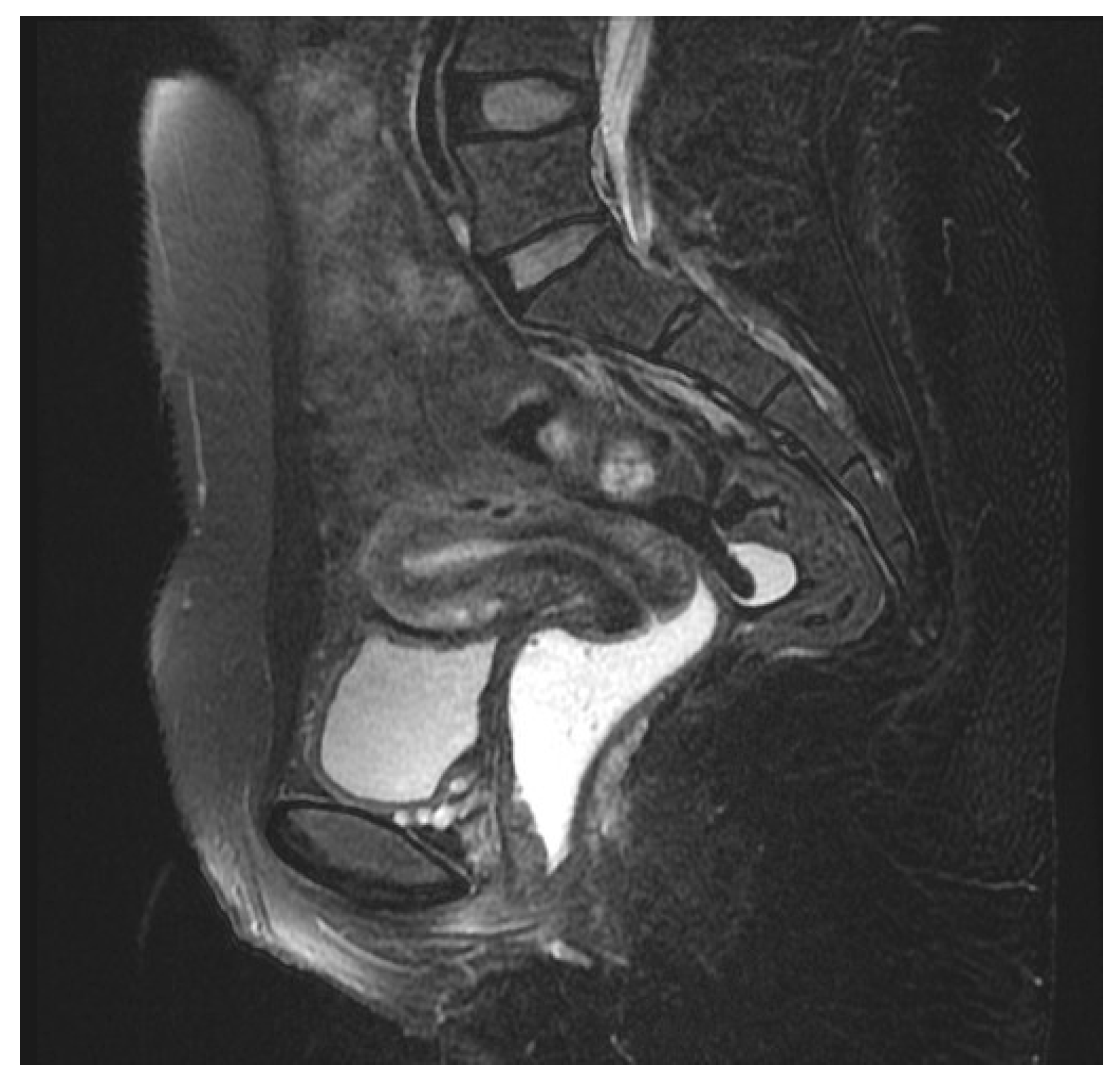

After diagnosis, patients that demanded fertility preservation and were candidates underwent a preoperative study including a magnetic resonance image to assure tumoral size (

Figure 1), absence of distant metastasis and no lymph node involvement.

The surgery was a standard procedure in all cases, and was performed with Da Vinci surgical system. Until March 2015 da Vinci standard was used; beyond that date, the hospital changed the robotic platform and achieved the Xi da Vinci, which was the one used from that date onwards.

Surgery was performed as follows: the patient was placed in lithotomy position. Umbilical incision for Hasson´s technique was used. Pneumoperitoneum with pressures maximum to 12 mmHg was established and three 8 mm robotic trocars were placed; through those trocars the monopolar scissor (arm 1), bipolar fenestrated forceps (arm 3) and prograsp grasper (arm 4) were placed. An auxiliary trocar of 5 mm or 10 mm was placed on the left side of the umbilicus, and was used by the assistant for conventional laparoscopy. Detail of the trocar placement is shown on

Figure 2.

First, a bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy was performed and the lymph nodes were sent to frozen section for intraoperative histological analysis. In case of positive nodes, the tumor was upstaged due to lymph node involvement, so the patient was not amenable for radical surgery. In that case, a transperitoneal infrarenal paraaortic lymphadenectomy was done and the patient was derived to chemo- radiotherapy as definitive treatment. If pelvic lymph nodes were negative, a nerve-sparing radical trachelectomy was performed with the preservation of both uterine arteries. The cervix was sectioned below the isthmus and removed vaginally leaving the uterus attached to the ovaries, the round ligaments and the uterine arteries. A frozen section of the upper margin was then performed to confirm clear margins. A permanent cervical cerclage with a non-absorbable suture was placed just below the isthmus. Finally, anastomosis between the remaining uterine body and the vaginal cuff was performed robotically with an absorbable suture. The radical removal of the parametrium made it advisable to leave an urinary catheter for urinary monitoring.

3. Results

A total of seven patients who underwent radical robotic trachelectomy were studied. The range of ages were from 23 to 35 years old, with a median patient age of 30 years old. Their body mass index was from 19 to 28, with a mean of 24. Staging was based on FIGO stage system. Since there was an update in 2018 but the majority of patients were diagnosed prior to that new staging, we decided to use the FIGO stage 2009 in the article for standardization. Final clinical stage was IA2 in 1 patient, IB1 in 5 patients and IB2 in 1 patient. Histology of the tumor was squamous cell carcinoma in 4 patients (57%) and HPV adenocarcinoma in the remaining 3 patients (43%). Surgery was performed with Da Vinci standard in 3 (43%) of the patients and Da Vinci Xi in 4 (57) %. Time of surgery was divided on skin-to-skin time, which was defined as the time of the radical trachelectomy procedure only, and total operating time, which also included docking time of the robot. The mean total surgical time was 285 minutes, ranging from 247 to 315. The mean skin-to-skin time was 215 minutes, ranging from 183 to 247.

There were not intraoperative complications, but 2 patients (28.5%) experienced postoperative complications such as hematometra and femoral neuropathy. At a median follow- up of 53.3 months (range from 18 to 115 months), one patient experienced tumor recurrence and finally died of disease. Two patients tried to get pregnant. The first underwent an in vitro fertilization and delivered by cesarean section at 37 weeks of pregnancy a healthy newborn. The second also underwent an in vitro fertilization and had a premature delivery by cesarean section at 28 weeks of pregnancy. All robotic radical trachelectomy results are summarized in

Table 1.

The patient that had relapse of the disease underwent a preoperative pelvic magnetic resonance that described a 15 millimeters tumor, so she was referred to conservative surgery. The final histological analysis reported a 3 centimeters tumor with lymph vascular space invasion and deep cervical stromal invasion. According to those risk factors, she was proposed adjuvant treatment, but she had strong childbearing desire, so she refused to undergo any type of adjuvant treatment or completion of surgery, despite medical advice. After 12 months of follow- up, the image techniques, pelvic examination, pap- smear and HPV test were all negative so she was allowed to try to get pregnant. Shortly after, she consulted for an episode of metrorrhagia, with normal clinical examination. She underwent a hysteroscopy, that observed a tumoral mass, which was confirmed by biopsy. A pelvic magnetic resonance image observed a pelvic tumor of 27x15 millimeters involving the muscular of the bladder. A treatment with chemo- radiotherapy was initiated, but was not effective, with local disease progression and vagino-vesical fistula. The positron emission tomography scan did not evidence signs of distant metastasis, so anterior pelvic exenteration was proposed and performed afterwards, with tumor- free margins. The patient recovery was adequate, with a hospital discharge after 33 days of the surgery. Five months later, pulmonary metastatic disease was found followed by peritoneal carcinomatosis; that lead to her decease four months later.

4. Discussion

Radical trachelectomy is a thrilling option for fertility sparing surgery after diagnosis of cervical cancer in young patients [

11]. As for all treatments, it is important to offer similar rates of complications and oncological prognosis than standard procedures, in order to establish it as a safe treatment for our patients.

Surgery for cervical cancer has to be radical in order to assure the removal of the parametrium, as it is mandatory for an adequate treatment in the majority of cases. Robotic surgery has the advantages of minimally invasive surgery in terms of shorter hospital stay and less postoperative pain comparing to laparotomic approach. Robotics has also some advantages inherent to the robot itself, as the addition of extreme accuracy for dissection, but also reduction in surgeon-dependent factors such as tremor [

12]. The use of robotic surgery does not imply less surgical radicality, as there are no differences in length of parametrial tissue removed comparing to different surgical options [

13]

. As vaginal approach is also a widespread surgical option, it has been compared with robot-assisted surgery. No differences were found on remaining cervical length among them; furthermore, robotic surgery enables a more accurate placement of the cerclage, closer to the inner cervical os [

14]

.

Considering complications, MIS has shown similar rates of intraoperative and postoperative complications than open surgery, with a significantly lower blood loss [

15]. Some groups have even found lower rates of blood loss with the use of robotic surgery, compared to conventional laparoscopy [

16]. Robotics also provide an improvement in postoperative recovery, with shorter hospital stay [

17]. No significant differences were found regarding mean operative time when compared to open surgery. In our series, only two minor postoperative complications were reported (28.6%). All our patients had a quick recovery and a short hospital stay.

Once advantages of MIS and especially robotic surgery are shown, it is time to discuss risk factors that may condition the indication of conservative procedures. There are many factors that have influence on prognosis for cervical cancer. For conservative procedures, the main factors are tumor size, FIGO stage and margins condition [

18]. Lymph node status does not play a role, since the presence of tumoral cells in lymph nodes is a contraindication for any type of surgical treatment in cervical cancer. FIGO stage and, therefore, tumoral size, has a huge impact in prognosis. In the beginning, fertility sparing surgery was a possible option in tumors up to 4 cm, as long as tumor- free margins were assured [

19]; nonetheless, some groups were already more restrictive, using 2 cm limit [

20]. Currently, there is a consensus to limit the size in all cases to 2 cm, so trachelectomy is an option only for stages IB1 (FIGO stage 2018) or less [

21]. Some studies discuss the possibility of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by conservative procedures, to enable conservative procedures in bigger tumors, although it is not a widespread management [

22]. The state of surgical margins is a key point for fertility sparing surgery, since the presence of disease in the upper margin would lead to extended cervical resection if free margins were feasible; if free margins were not obtained, a hysterectomy would be mandatory. Prior to consider surgery for cervical cancer, it is mandatory to histologically assure absence of lymph node involvement, even for standard radical hysterectomy.

Taking into account the expected prognosis of conservative procedures for cervical cancer, many studies have been published. Initially, MIS procedures were scarce, so some groups compared it to open surgery and even to different procedures such as conization [

23]. In this study, recurrences were reported in all groups; deaths were present in all the groups except for the robotic trachelectomy. The rate of recurrences was higher in tumors bigger than 2 centimeters. Data are summarized in

Table 2.

Some other studies consider exclusively robot-assisted radical trachelectomy, for early-stage cervical cancer. When FIGO stages are IA1- IA2, no recurrences were reported during follow-up [

24]

. Over time, restrictions on tumoral size were less strict, so conservative procedures were applicable to bigger tumors, proving also low rates of recurrences; this study reports only 4% of local recurrence after radical trachelectomy for stages IA1- IB1 [

25]

. It is important to highlight that the majority of these studies do not specify tumoral size; when they do, it is less than 2.5 centimeters [

26].

Undoubtedly, special mention deserves LACC study, as it unexpected results led to a turning point in the surgical management of cervical cancer. LACC study conferred worse prognosis for minimally invasive surgery compared to open surgery, causing a change in surgical practice worldwide

⁹. Many studies were conducted afterwards in order to rebate those results and add evidence to bring MIS back as a safe option for cervical cancer. Factors such as tumor size above 2 centimeters, impact of pneumoperitoneum and use of a uterine manipulator were identified as potential causes for recurrences increase [

27]. Those results have resulted in a change of paradigm with the appearance of protective maneuvers to avoid tumor spread, such as vaginal cuff closure while tumor manipulation [

28]. Also, prior conization has been proposed as a strategy to minimize risk of spread [

29]. Limitation on tumor size < 2 centimeters has also become mandatory, and it is considered probably the main factor having influence in prognosis [

30]. All data are shown on

Table 3.

In our study, one (14.3%) case of recurrence was reported, that led to the patient’s death. It is important to identify risk factors that may have played a role in this adverse outcome, in order to prevent it from happening again. The six patients that remain free of disease at the time of the data collection had a tumor smaller than 3 centimeters. The patient that had the recurrence had a three- centimeter tumor with extensive lymph vascular space invasion and deep cervical stromal invasion. At the time of her diagnosis, there was no strict size criteria that prohibited the conservative procedure. Nonetheless, the patient was advised to undergo standard procedure due to the tumoral size, but she refused due to her strong childbearing wishes. After conservative surgery, since tumor had an extensive ILV she was recommended for adjuvant therapy, that she also refused. Considering published studies that only describe robotic radical trachelectomy, none of them had recurrences nor deaths; analyzing tumor characteristics, all of them had a size of less than two centimeters. That fact would have had a great impact on the good prognosis

Therefore, we believe the limitation of size to offer fertility-sparing surgery for cervical cancer is mandatory, since recurrences are strongly related to tumor size, with the subsequent impact on prognosis.

Our study has some limitations: it is a retrospective study so data collection may have some missing data. Moreover, some of our patients were referred to our hospital for surgery, and returned to their own hospitals which were located at a different city for follow- up, so the results need to be carefully considered due to the possibility of some missing data. Second, it is a still short series of patients and, the presence of one death due to disease has great impact on the final results; nonetheless, we think our results are useful for the literature, since we have learned the importance of tumor size limitation.

In conclusion, with the results published so far, we strongly believe that robot-assisted radical trachelectomy is a safe option for patients that wish to preserve their fertility, as long as strict inclusion criteria are fulfilled. In the absence of those criteria, patients should be referred to standard surgery, with the subsequent loss of the uterine body. Robotic surgery has similar rates of oncological safety and complications than open procedures, with a shorter recovery time.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Marta Heras and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its observational retrospective nature.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Buskwofie A, David-West G, Clare CA. A Review of Cervical Cancer: Incidence and Disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020 Apr;112(2):229-232. Epub 2020 Apr 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimple SA, Mishra GA. Global strategies for cervical cancer prevention and screening. Minerva Ginecol. 2019 Aug;71(4):313-320. Epub 2019 Feb 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, Sundström K, Dillner J, Sparén P. HPV Vaccination and the Risk of Invasive Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct 1;383(14):1340-1348. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somashekhar SP, Ashwin KR. Management of Early Stage Cervical Cancer. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2015;10(4):302-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagotti A, Gagliardi ML, Moruzzi C, Carone V, Scambia G, Fanfani F. Excisional cone as fertility-sparing treatment in early-stage cervical cancer. Fertil Steril. 2011 Mar 1;95(3):1109-12. Epub 2010 Dec 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dursun P, LeBlanc E, Nogueira MC. Radical vaginal trachelectomy (Dargent's operation): a critical review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007 Oct;33(8):933-41. Epub 2007 Jan 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranev D, Teixeira J. History of Computer-Assisted Surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2020 Apr;100(2):209-218. Epub 2020 Jan 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Z, Li X, Tian S, Zhu T, Yao Y, Tao Y. Superiority of robotic surgery for cervical cancer in comparison with traditional approaches: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2017 Apr;40:145-154. Epub 2017 Feb 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, Lopez A, Vieira M, Ribeiro R, Buda A, Yan X, Shuzhong Y, Chetty N, Isla D, Tamura M, Zhu T, Robledo KP, Gebski V, Asher R, Behan V, Nicklin JL, Coleman RL, Obermair A. Minimally Invasive versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 15;379(20):1895-1904. Epub 2018 Oct 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvo G, Ramirez PT, Leitao MM, Cibula D, Wu X, Falconer H, Persson J, Perrotta M, Mosgaard BJ, Kucukmetin A, Berlev I, Rendon G, Liu K, Vieira M, Capilna ME, Fotopoulou C, Baiocchi G, Kaidarova D, Ribeiro R, Pedra-Nobre S, Kocian R, Li X, Li J, Pálsdóttir K, Noll F, Rundle S, Ulrikh E, Hu Z, Gheorghe M, Saso S, Bolatbekova R, Tsunoda A, Pitcher B, Wu J, Urbauer D, Pareja R. Open vs minimally invasive radical trachelectomy in early-stage cervical cancer: International Radical Trachelectomy Assessment Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Jan;226(1):97.e1-97.e16. Epub 2021 Aug 27. PMCID: PMC9518841. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segarra-Vidal B, Persson J, Falconer H. Radical trachelectomy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021 Jul;31(7):1068-1074. Epub 2021 Mar 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han L, Chen Y, Zheng A, Tan X, Chen H. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical trachelectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cancer Res. 2023 Sep 15;13(9):4466-4477. PMCID: PMC10560958. [PubMed]

- Nick AM, Frumovitz MM, Soliman PT, Schmeler KM, Ramirez PT. Fertility sparing surgery for treatment of early-stage cervical cancer: open vs. robotic radical trachelectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2012 Feb;124(2):276-80. Epub 2011 Oct 27. PMCID: PMC4286385. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson J, Imboden S, Reynisson P, Andersson B, Borgfeldt C, Bossmar T. Reproducibility and accuracy of robot-assisted laparoscopic fertility sparing radical trachelectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2012 Dec;127(3):484-8. Epub 2012 Aug 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira MA, Rendón GJ, Munsell M, Echeverri L, Frumovitz M, Schmeler KM, Pareja R, Escobar PF, Reis RD, Ramirez PT. Radical trachelectomy in early-stage cervical cancer: A comparison of laparotomy and minimally invasive surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2015 Sep;138(3):585-9. Epub 2015 Jun 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong DG, Lee YS, Park NY, Chong GO, Park IS, Cho YL. Robotic uterine artery preservation and nerve-sparing radical trachelectomy with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy in early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011 Feb;21(2):391-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett AF, Stone PJ, Duckworth LA, Roman JJ. Robotic radical trachelectomy for preservation of fertility in early cervical cancer: case series and description of technique. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009 Sep-Oct;16(5):569-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slama J, Runnebaum IB, Scambia G, Angeles MA, Bahrehmand K, Kommoss S, Fagotti A, Narducci F, Matylevich O, Holly J, Martinelli F, Koual M, Kopetskyi V, El-Balat A, Corrado G, Căpîlna ME, Schröder W, Novàk Z, Shushkevich A, Fricová L, Cibula D. Analysis of risk factors for recurrence in cervical cancer patients after fertility-sparing treatment: The FERTIlity Sparing Surgery retrospective multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Apr;228(4):443.e1-443.e10. Epub 2022 Nov 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rob L, Skapa P, Robova H. Fertility-sparing surgery in patients with cervical cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Feb;12(2):192-200. Epub 2010 Jul 8. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2011 Jan;12(1):11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lintner B, Saso S, Tarnai L, Novak Z, Palfalvi L, Del Priore G, Smith JR, Ungar L. Use of abdominal radical trachelectomy to treat cervical cancer greater than 2 cm in diameter. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Jul;23(6):1065-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R. Cancer of the cervix uteri: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Oct;155 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):28-44. PMCID: PMC9298213. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed AH, Shepard MK, Maglinte DD, Ding S, Del Priore G. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by simultaneous robotic radical trachelectomy and reversal of tubal sterilization in stage IB2 cervical cancer. JSLS. 2012 Oct-Dec;16(4):650-3. PMCID: PMC3558908. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentivegna E, Gouy S, Maulard A, Chargari C, Leary A, Morice P. Oncological outcomes after fertility-sparing surgery for cervical cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2016 Jun;17(6):e240-e253. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez PT, Schmeler KM, Malpica A, Soliman PT. Safety and feasibility of robotic radical trachelectomy in patients with early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010 Mar;116(3):512-5. Epub 2009 Nov 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen G, Lönnerfors C, Falconer H, Persson J. Reproductive and oncologic outcome following robot-assisted laparoscopic radical trachelectomy for early stage cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Apr;141(1):160-5. Epub 2016 Feb 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andou M, Yamanaka A, Kodama K, Shirane A, Fukuta M. Robotically-Assisted Radical Trachelectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015 Nov-Dec;22(6S):S11-S12. Epub 2015 Oct 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touhami O, Plante M. Minimally Invasive Surgery for Cervical Cancer in Light of the LACC Trial: What Have We Learned? Curr Oncol. 2022 Feb 14;29(2):1093-1106. PMCID: PMC8871281. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler C, Hertel H, Herrmann J, Marnitz S, Mallmann P, Favero G, Plaikner A, Martus P, Gajda M, Schneider A. Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with transvaginal closure of vaginal cuff - a multicenter analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019 Jun;29(5):845-850. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronado PJ, Gracia M. Robotic radical hysterectomy after conization for patients with small volume early-stage cervical cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2024 Feb;92:102434. Epub 2023 Dec 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibula D, Raspollini MR, Planchamp F, Centeno C, Chargari C, Felix A, Fischerová D, Jahnn-Kuch D, Joly F, Kohler C, Lax S, Lorusso D, Mahantshetty U, Mathevet P, Naik R, Nout RA, Oaknin A, Peccatori F, Persson J, Querleu D, Bernabé SR, Schmid MP, Stepanyan A, Svintsitskyi V, Tamussino K, Zapardiel I, Lindegaard J. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines for the management of patients with cervical cancer - Update 2023. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023 May 1;33(5):649-666. PMCID: PMC10176411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).