Introduction

Peripheral entrapment neuropathy is a widely diagnosed condition in the United States [

1]. Neurological surgeons, along with other specialties, perform decompression procedures to relieve these neuropathies [

1,

2]. Surgical skills labs, anatomical confidence, and procedural techniques play a vital role in the development and maintenance of surgical skills [

3,

4]. Since the 2019 COVID-19 pandemic, medical education has reduced the use of cadavers for their medical students, residents, and attendings [

5]. However, the use of cadavers in medical education can provide trainees with the invaluable experience of developing the appropriate skills and confidence that is crucial for performing surgical operations on living patients [

3,

6,

7]. Furthermore, learning with cadavers facilitates surgical and neuroanatomical procedural practice and assessment. Embalmed cadavers enable trainees to operate using tissue planes and on structures that simulate life-like scenarios encountered in the operating room [

4]. Embalmed cadavers are a feasible, beneficial, and efficient method for medical education and training. A single cadaver can be used by different trainees, and different specialists, to refine their skills on multiple surgical procedures [

3,

4,

6,

7,

8]. Practicing a minimally invasive surgical approach on cadavers can provide medical students, residents, and any other trainees with proper techniques to ensure a successful outcome [

9].

For this cadaveric study, we chose a microscopic approach rather than an open procedure with surgical loops or using an endoscope. In more recent years, minimally invasive procedures for peripheral neuropathy caused by entrapment or trauma have become more popular due to their various benefits, including reduced blood loss and risk of infection compared to larger incision. A few published papers describe the procedures and learning methods for these surgeries. Therefore, the aim of this study is to discuss less common nerve entrapments, their anatomy, the surgical procedure, and the medical education methods used on the cadaver. We hope this encourages institutions to invest in a cadaveric skills labs for their trainees to experience maximum benefits.

Methods

Preparation of the cadaver: To ensure anonymity of the cadaver’s identity, the local willed body program removes clothing, personal items, documents all information, and places a coded identification tag on the ankle. The cadaver is bathed and sprayed with disinfectant on surfaces and orifices. The body is injected with 16 oz of embalming fluid that consists of ethylene glycol, formaldehyde, and methanol in the first step. The second step requires the injection of 2.75 gallons of water. Most cadavers will be set inside a 10% phenol bath between 12 and 24 hours prior to being in a 38–42-degree refrigerator until needed.

An attending neurological surgeon was present during every procedure and step to ensure proper techniques, methods, and success.

Tools: #3 knife handle, #15 blade, #11 blade, ratcheted forceps, hemostats, curved hemostats, Weitlaner retractor, Gelpi retractor, and a surgical microscope.

More methods will be discussed in the sections for the nerve and its respective decompression surgery.

Tibial Nerve

Introduction

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) is the compression of the tibial nerve and other structures within the tarsal tunnel [

10]. This syndrome may also be referred to as a tibial nerve dysfunction or posterior tibial nerve neuralgia [

11]. Posterior-inferior to the medial malleolus of the ankle, there is a fibro-osseous, narrow canal that contains the tendons, vasculature, and the tibial nerve [

10]. The most common etiologies of TTS include compression of the tarsal tunnel from an external source, fractures of the distal leg or proximal foot, and tenosynovitis. External sources of compression can be caused by cysts, tumors, dilated veins, or hypertrophy of muscles [

12]. The tibial nerve can also be compressed proximally at the tendinous arch of the soleus muscle, although this is rare. This syndrome is referred to as a “soleus tendinous arch entrapment” or a “soleal sling syndrome” [

13]. In both entrapment syndromes, patients report paresthesia with a burning, shooting pain in the plantar foot and digits. Constant use of the leg (walking, running, driving, stretching) that creates dorsiflexion and eversion may exacerbate the syndromes. Most cases will resolve with a conservative treatment plan, which includes pain relief medication, physical therapy, or corticosteroid injections to reduce edema [

13,

14]. Failure of these methods of TTS decompression may indicate surgical intervention.

Surgical Anatomy

Originating from the ventral rami of the L4-S3 spinal nerve roots, the tibial nerve is one of two terminal branches of the sciatic nerve. Although it is a continuation from the sciatic nerve, the sciatic nerve is divided into two sections: the tibial and peroneal (fibular) section. The sciatic nerve will provide motor innervation and sensory afferent fibers in the posterior leg15. A few centimeters superior to the popliteal fossa, the sciatic nerve bifurcates to give off the two terminal branches. The popliteal fossa is bordered by the semimembranosus muscle superior-medially, the biceps femoris muscle superior-laterally, inferior-medially by the medial head of the gastrocnemius, and inferior-laterally by the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. The contents of the popliteal fossa include the tibial nerve, popliteal vein, popliteal artery, small saphenous vein, common peroneal nerve, and the popliteal lymph nodes, from superficial to deep in a posterior to anterior view, respectively. Distally to the bifurcation, the tibial nerve gives off the medial sural cutaneous nerve. This afferent, sensory nerve branch travels superficially to both heads of the gastrocnemius muscle to unite with the sural communicating branch from the common peroneal (common fibular) nerve. After joining, these nerves contribute to sensation of the posterolateral aspect of the leg. The remainder of the tibial nerve will traverse deep to the gastrocnemius muscle and plantaris muscle to the tendinous arch of the soleus muscle to enter the deep, posterior compartment of the leg16. The tibial nerve will travel on the posterior aspect of the tibialis posterior muscle prior to entry into the tarsal tunnel. Proximal to the tunnel, the tibial nerve bifurcates and gives off another afferent, sensory branch, the medial calcaneal nerve. Posterior to the medial malleolus, the tarsal tunnel is bordered by the flexor retinaculum superficially (the “roof”), deep by the abductor hallucis (the “floor”), deep and lateral by the calcaneus and talus. From anterior to posterior, the tarsal tunnel houses the tendon of the tibialis posterior, the tendon of flexor digitorum, posterior tibial artery, posterior tibial vein, tibial nerve, and the tendon of flexor hallucis longus. Distally to the tarsal tunnel, the tibial nerve terminates by bifurcating into the medial and lateral plantar nerves.

Methods

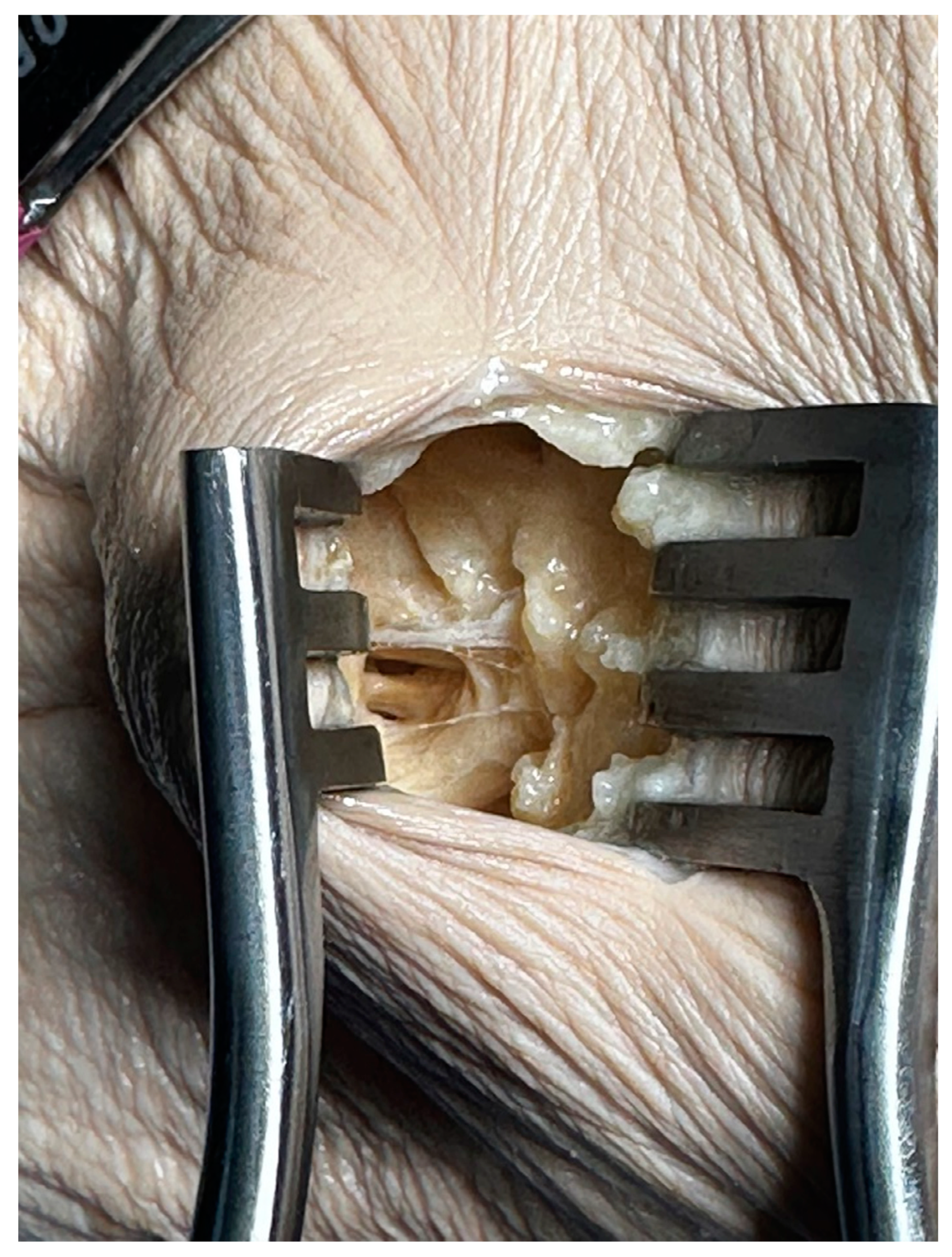

Prior to the minimally invasive procedure, one leg was used to explore relative anatomy with a long incision (

Figure 1 Left). Once confidence about the procedure increased, the other leg was prepared for the surgery. Posterior to medial malleolus, a 1.5 cm incision was made posterior to the medial malleolus. Subcutaneous tissue was carefully dissected, as the tissue planes are shallow. Once the entire retinaculum and medial cutaneous nerve branch were visualized, dissection was made to release entrapment (

Figure 1 Right).

Common Peroneal Nerve

Introduction

The common peroneal nerve, also referred to as the common fibular nerve, can cause compressive neuropathy in the lower extremity [

17]. Entrapment around the fibular head is the most common peroneal nerve entrapment neuropathy (PNEN), causing paresthesia, anesthesia, and motor weakness [

17,

18]. PNEN is the most frequent compressive neuropathy in the lower extremities and the third most common peripheral nerve entrapment neuropathy, following the median and ulnar nerve [

17,

19]. PNEN can be caused by traumatic or non-traumatic causes, specifically blunt trauma or laceration to the fibular neck region, knee dislocation, proximal fibula fracture, chronic or high compression from tight bandages and clothes, and posture [

17,

20].

Surgical Anatomy

The common peroneal nerve arises from the lumbosacral plexus, specifically the L4, L5, S1 and S2 spinal nerve roots [

17,

21,

22]. It originates from the sciatic nerve, which bifurcates into the tibial and peroneal nerve proximal to the popliteal fossa [

17,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The common peroneal nerve will course on the posterolateral part of the thigh deep to the long head of the biceps femoris prior to entry into the popliteal fossa [

19,

22,

25]. It then courses lateral to the fibula around the bony prominence. Lateral and inferior in respect to the fibular head, the common fibular nerve bifurcates into the superficial fibular and deep fibular nerves [

19,

22].

Methods

A longitudinal incision was made around the fibular neck after palpating the fibular head. Dissection of the subcutaneous tissue was performed to expose the gastrocnemius and superficial head of the peroneus longus muscles along with the superficial fascia between these two muscle bellies. Careful division of the superficial fascia allowed visualization of the common peroneal nerve situated deep to the fibrous band between the superficial head of the peroneus longus muscle and the soleus muscle (

Figure 2). Dissection of the band was made to relieve the entrapment.

Posterior Interosseous Nerve

Introduction

The posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) innervates the posterior forearm muscles, known as the extensors. PIN syndrome is considered the most common compressive neuropathy affecting the radial nerve; however, it is not a common neuropathy in the general patient population [

26,

27]. PIN syndrome can present with weakness in finger and thumb extension but will have normal sensation [

26,

27,

28,

29]. As a result of limited innervation of the extensor carpi ulnaris, patients with PIN syndrome can present with radial deviation of the wrist during extension. PIN syndrome occurs due to trauma, brachial neuritis, rheumatoid arthritis, spontaneous compression, and repetitive pronation/supination activities [

28]. Another cause is the hypertrophy of the recurrent radial vessels, often called the “leash of Henry” [

26]. The most common site of PIN compression is the arcade of Frohse, or the proximal margin of the supinator muscle [

26]. It can typically be remedied with conservative measures; however, symptoms that persist may require surgical decompression.

Surgical Anatomy

The PIN is a branch of the radial nerve, which stems from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus with spinal nerve roots C5 to T1. The radial nerve travels along the posterior arm and splits into the deep and superficial branches in the anterior proximal forearm, near the level of the head of the humerus [

26,

29]. The deep branch of the radial nerve journeys posteriorly along radial neck, across and above the fibrous layer of the articular capsule of the humeroulnar joint and annular ligament of the radius [

27,

29]. The PIN arises from the deep branch of the radial nerve, as it emerges from between the two bellies of the supinator muscle. The PIN continues down the posterior forearm, innervating the extensor carpi radialis brevis, supinator, extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor pollicis brevis and longus, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, extensor indicis, and abductor pollicis longus [

26,

28,

29].

Methods

Palpation identified the groove between the brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis muscles. A 1.5 cm longitudinal incision was made in the grove. Careful dissection of subcutaneous tissue was performed. Separation of the extensor digitorum and extensor carpi radialis brevis muscles exposed the PIN deep to the deep head of the supinator. Identification of the proximal edge of the supinator allowed for visualization and dissection of superficial fibrous bands at the radio-capitellar joint and the Arcade of Frohse to allow for decompression (

Figure 3).

Suprascapular Nerve

Introduction

The suprascapular nerve supplies the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, which are responsible for abduction and lateral rotation of the humerus at the glenohumeral joint, respectively. Suprascapular nerve entrapment can cause shoulder pain and weakness with symptoms depending on nerve entrapment location [

30]. Varying causes and symptoms cause suprascapular nerve entrapment syndrome difficult to diagnose, thus requiring a thorough history, nerve conduction tests, or imaging for confirmation [

30]. The etiologies of suprascapular nerve entrapment syndrome include traumatic injury, exertional overload, iatrogenic injury, systemic lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis [

31]. Additionally, the sharp borders of the suprascapular notch may cause irritation of the nerve, often called the “sling effect” [

31]. Males are more likely to have a V-shaped, or narrow, notch than females, predisposing them to nerve entrapment [

32]. The first line of treatment is rehabilitation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and lifestyle modification. However, surgery may be necessary if symptoms persist.

Surgical Anatomy

The suprascapular nerve emerges from the superior trunk of the brachial plexus (spinal nerve roots C5 and C6) and runs deep to the trapezius and laterally across the lateral cervical region. It then passes through the suprascapular notch, under the superior transverse suprascapular ligament, to the posterior scapular region [

31].

Methods

The cadaver’s right scapula was used to explore relative anatomy and landmarks to increase confidence before proceeding with the minimally invasive procedure. Three surgical techniques were used and are discussed below.

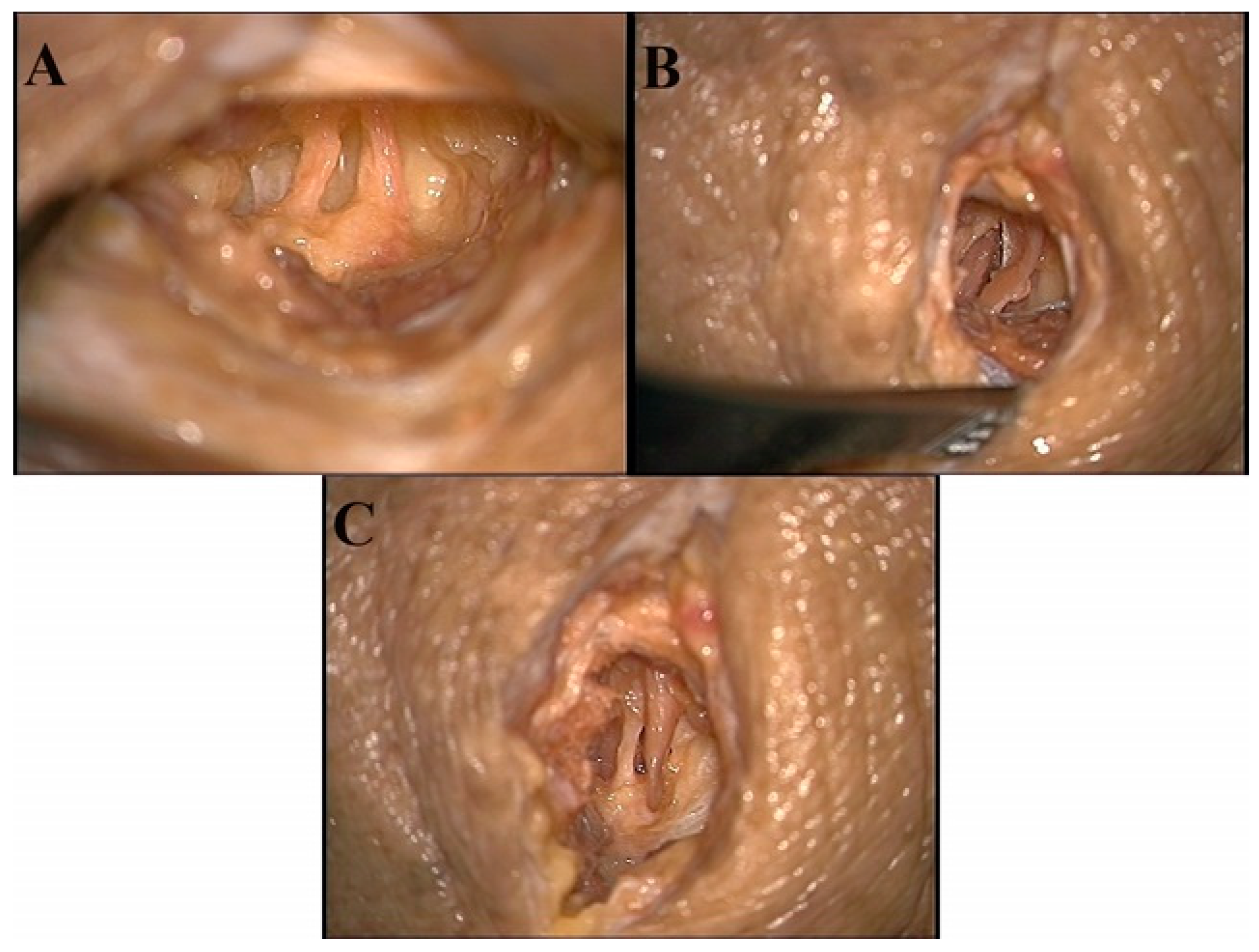

1. Suprascapular notch approach: Palpation of the clavicle and the spine of the scapula was performed. A 1.5 cm parallel incision, in relation to the clavicle, was made two inches medial of the spinoglenoid junction and inferior to the clavicle. Subcutaneous tissue was dissected, revealing the supraspinatus muscle. Careful retraction and dissection allowed for visualization of the suprascapular notch with the suprascapular artery and nerve. Decompression was made by the sectioning of the transverse scapular ligament (Figure 4A). However, some patients may be experiencing entrapment from a narrow canal. Therefore, decompression would be made using a shaver to increase the width of the suprascapular notch.

2. Scapular notch, superior approach: Palpation of the spine of the scapula was performed. A 1.5 cm parallel incision was made. Dissection of subcutaneous tissue revealed the spine of the scapula to view. Blunt dissection anteriorly along the spine was performed while retracting the supraspinatus muscle. Visualization of the suprascapular artery and nerve was made prior to entering the scapular notch (Figure 4B). Relieving the entrapment will be performed with a shaver to remove excess soft tissue and sectioning of the inferior transverse scapular ligament.

3. Scapular notch, inferior approach: Palpation of the spine of the scapula was performed. A 1.5 cm parallel incision along the inferior border of the spine allowed for dissection of subcutaneous tissue. The infraspinatus muscle was retracted inferiorly while blunt dissection continued along the inferior aspect of the scapular spine. Identification of the scapular notch revealed the suprascapular artery and nerve (Figure 4C). Relieving the entrapment will be performed with a shaver to remove excess soft tissue and sectioning of the inferior transverse scapular ligament.

Figure 4.

Image A shoes the suprascapular nerve (left) and artery (right) at the suprascapular notch. Image B shows the suprascapular artery (left) and nerve (right) superior to the suprascapular notch. Image C shows the suprascapular nerve (left) and artery (right) inferior to the suprascapular notch.

Figure 4.

Image A shoes the suprascapular nerve (left) and artery (right) at the suprascapular notch. Image B shows the suprascapular artery (left) and nerve (right) superior to the suprascapular notch. Image C shows the suprascapular nerve (left) and artery (right) inferior to the suprascapular notch.

Discussion

Cadavers offer advantages to learning anatomy and creating strong clinical and surgical procedural skills. The closeness to a life-like patient fortifies the trainees’ manual skills and comprehension of the dissection. In the cadaveric surgical operations for peripheral nerve decompression surgeries that was performed, trainees had the ability to be hands-on during the procedure, participate as the first assist to the surgeon, or perform the surgery with guidance from the neurosurgeon.

There are multiple different ways to embalm a human cadaver for the appropriate surgical training procedure. Our approach involved using a ‘fixed’ cadaver, as opposed to a fresh or ‘soft’ cadaver. The authors acknowledge that fixed cadavers do not ideally replicate real-time surgical conditions, such as tissue color and texture. However, they offer valuable opportunities to learn neuroanatomy and practice the tactile aspects of decompressive release surgeries. Future research might consider using different methods of embalming, such as soft cadaver embalming, to resemble fresh tissue. This will allow trainees the ability to reenact surgical scenarios more closely than fixed cadavers. These embalming techniques provide resemblance of colors and textures of living muscles, nerves, vasculature, and other tissues, further preparing trainees for real surgical scenarios.

Our study relied on subjective feedback with an objective assessment. There was a total of 5 trainees, and all reported that their confidence in the procedure increased after reviewing relative anatomy and from performing the procedure on the cadaver. Each student was able to thoroughly explain the neuroanatomy of the procedure after the study was completed. The neurosurgeon present assessed the trainees ability to use surgical skills on the cadaver and saw an improvement of skills and accuracy.

Conclusions

Medical institutions that have cadaver skills labs and anatomical dissections for students provide trainees with invaluable experience. For example, trainees can increase their proficiency in surgical skills. Creating proper surgical skills requires more than just didactic, pedagogical methods of learning. Hands-on, palpable methods are necessary for developing a confident and skillful surgeon. Neurosurgeons, neurosurgery residents, and medical students can use cadavers to repeatedly practice and simulate various operations. This study fortified the idea that students and trainees can practice a multitude of procedures on one cadaver. These trainees can also fortify their understanding of the anatomy of peripheral nerve entrapments. Cadaveric practice also has the benefit of handling surgical tools compared to 3D anatomy and virtual reality platforms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Marcos Arciniega and Laszlo Nagy; methodology, Marcos Arciniega; validation, Marcos Arciniega, Prudhvi Gundupalli, Alexandra Munson, Laszlo Nagy; formal analysis, Marcos Arciniega and Laszlo Nagy; investigation, Marcos Arciniega, Prudhvi Gundupalli, Alexandra Munson, Laszlo Nagy; resources, Marcos Arciniega and Laszlo Nagy; data curation, Marcos Arciniega, Prudhvi Gundupalli, Alexandra Munson, Laszlo Nagy; writing—original draft preparation, Marcos Arciniega, Prudhvi Gundupalli, Alexandra Munson, Laszlo Nagy; writing—review and editing, Marcos Arciniega, Prudhvi Gundupalli, Alexandra Munson, Laszlo Nagy; visualization, Marcos Arciniega, Prudhvi Gundupalli, Alexandra Munson, Laszlo Nagy; supervision, Laszlo Nagy; project administration, Laszlo Nagy. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Specimens/Cadavers

Un-embalmed human cadavers were appropriately acquired through the Institute of Anatomical Sciences, Willed-Body Program at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock TX, USA and approved for use by the Institutional Anatomical Review Committee. Cadaver specimens were handled in accordance with university policy and State of Texas regulations as determined by the Texas State Anatomical Board. IARC approval #R-111522

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the research using unidentifiable and the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Willed Body Program completely de-identifying information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. The cadavers were donated for the purpose of medical studies and research.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their deepest gratitude to the unselfish men, women, and family members who donate their bodies to the Institute of Anatomical Sciences, Willed Body Program at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center for educational and research purposes. Without their contribution, studies like this one would not be possible. The authors thank the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and the School of Health Professions’ Center for Rehabilitation Research and Institute of Anatomical Sciences for the use of the Clinical Anatomy Research Laboratory. The authors also thank Rex Johnson, Deanna Wise, Kelsey Patschke, and Jason C. Jones, Willed Body Program Director, for their assistance during this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nguyen B, Parikh P, Singh R, Patel N, Noland SS. Trends in Peripheral Nerve Surgery: Workforce, Reimbursement, and Procedural Rates. [CrossRef]

- Nawabi DH, Jayakumar P, Carlstedt T. Peripheral Nerve Surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(3):327–8. [CrossRef]

- Lewis CE, Peacock WJ, Tillou A, Hines OJ, Hiatt JR. A Novel Cadaver-Based Educational Program in General Surgery Training. Journal of Surgical Education. 2012;69(6):693-698. [CrossRef]

- Aboud E, Al-Mefty O, Yaşargil MG. New laboratory model for neurosurgical training that simulates live surgery. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2002;97(6):1367-1372. [CrossRef]

- Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Dumont AS, Tubbs RS. A review of anatomy education during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Revisiting traditional and modern methods to achieve future innovation. Clinical Anatomy. 2021;34(1):108-114. [CrossRef]

- Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, Ornstein E, Ranstam J, Rosén I. Prevalence of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in a General Population. JAMA. 1999;282(2):153-158. [CrossRef]

- Hazan E, Torbeck R, Connolly D, et al. Cadaveric simulation for improving surgical training in dermatology. Dermatology Online Journal. 2018;24(6). [CrossRef]

- Streith L, Cadili L, Wiseman SM. Evolving anatomy education strategies for surgical residents: A scoping review. The American Journal of Surgery. 2022;224(2):681-693. [CrossRef]

- Lee YS, Youn H, Shin SH, Chung YG. Minimally Invasive Carpal Tunnel Release Using a Hook Knife through a Small Transverse Carpal Incision: Technique and Outcome. Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery. 2023;15(2):318. [CrossRef]

- Moroni S, Fernández Gibello A, Zwierzina M, et al. Ultrasound-guided decompression surgery of the distal tarsal tunnel: a novel technique for the distal tarsal tunnel syndrome-part III. 2019;41:313-321. [CrossRef]

- Kiel J, Kaiser K. Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome. Entrapment Neuropathy of the Lumbar Spine and Lower Limbs. Published online August 8, 2022:85-92. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Mangi MD, Zadow S, Lim WY. Nerve entrapment syndromes of the lower limb: a pictorial review. Insights into Imaging. 2023;14(1). [CrossRef]

- Williams EH, Rosson GD, Hagan RR, Hashemi SS, Dellon AL. Soleal sling syndrome (proximal tibial nerve compression): Results of surgical decompression. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2012;129(2):454-462. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Merchan EC, Moracia-Ochagavia I. Tarsal tunnel syndrome: current rationale, indications and results. EFORT Open Reviews. 2021;6(12):1140. [CrossRef]

- Desai SS, Cohen-Levy WB. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Tibial Nerve. StatPearls. Published online August 14, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537028/.

- Iida T, Kobayashi M. Tibial nerve entrapment at the tendinous arch of the soleus: a case report. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1997;334(334):265-269. [CrossRef]

- Fortier LM, Markel M, Thomas BG, Sherman WF, Thomas BH, Kaye AD. An Update on Peroneal Nerve Entrapment and Neuropathy. Orthopedic Reviews. 2021;13(2):2021. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto D, Isu T, Kim K, et al. Microsurgical Decompression for Peroneal Nerve Entrapment Neuropathy. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2015;55(8):669. [CrossRef]

- Poage C, Roth C, Scott B. Peroneal Nerve Palsy: Evaluation and Management. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2016;24(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Lezak B, Massel DH, Varacallo M. Peroneal Nerve Injury. StatPearls. Published online November 14, 2022. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549859/.

- Bowley MP, Doughty CT. Entrapment Neuropathies of the Lower Extremity. Medical Clinics of North America. 2019;103(2):371-382. [CrossRef]

- Dalley AF, Agur AMR. Lower Limb. In: Moore’s Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2024:703-707.

- Marciniak C. Fibular (Peroneal) Neuropathy: Electrodiagnostic Features and Clinical Correlates. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 2013;24(1):121-137. [CrossRef]

- Hardin JM, Devendra S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Calf Common Peroneal Nerve (Common Fibular Nerve). StatPearls. Published online October 17, 2022. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532968/.

- Garrett A, Black AC, Launico M v., Geiger Z. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Superficial Peroneal Nerve (Superficial Fibular Nerve). StatPearls. Published online October 24, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534793/.

- Węgiel A, Karauda P, Zielinska N, Tubbs RS, Olewnik Ł. Radial nerve compression: anatomical perspective and clinical consequences. Neurosurgical Review. 2023;46(1):53. [CrossRef]

- Bevelaqua AC, Hayter CL, Feinberg JH, Rodeo SA. Posterior Interosseous Neuropathy: Electrodiagnostic Evaluation. HSS Journal. 2012;8(2):184. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler R, DeCastro A. Posterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome. StatPearls. Published online May 1, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541046/.

- Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR. “Forearm”. Moore’s Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2024, pp. 569,580,584.

- Łabȩtowicz P, Synder M, Wojciechowski M, et al. Protective and Predisposing Morphological Factors in Suprascapular Nerve Entrapment Syndrome: A Fundamental Review Based on Recent Observations. BioMed Research International. 2017;2017. [CrossRef]

- Leider JD, Derise OC, Bourdreaux KA, et al. Treatment of suprascapular nerve entrapment syndrome. Orthopedic Reviews. 2021;13(2):2021. [CrossRef]

- Polguj M, Sibiński M, Grzegorzewski A, Grzelak P, Majos A, Topol M. Variation in morphology of suprascapular notch as a factor of suprascapular nerve entrapment. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).