Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

11 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

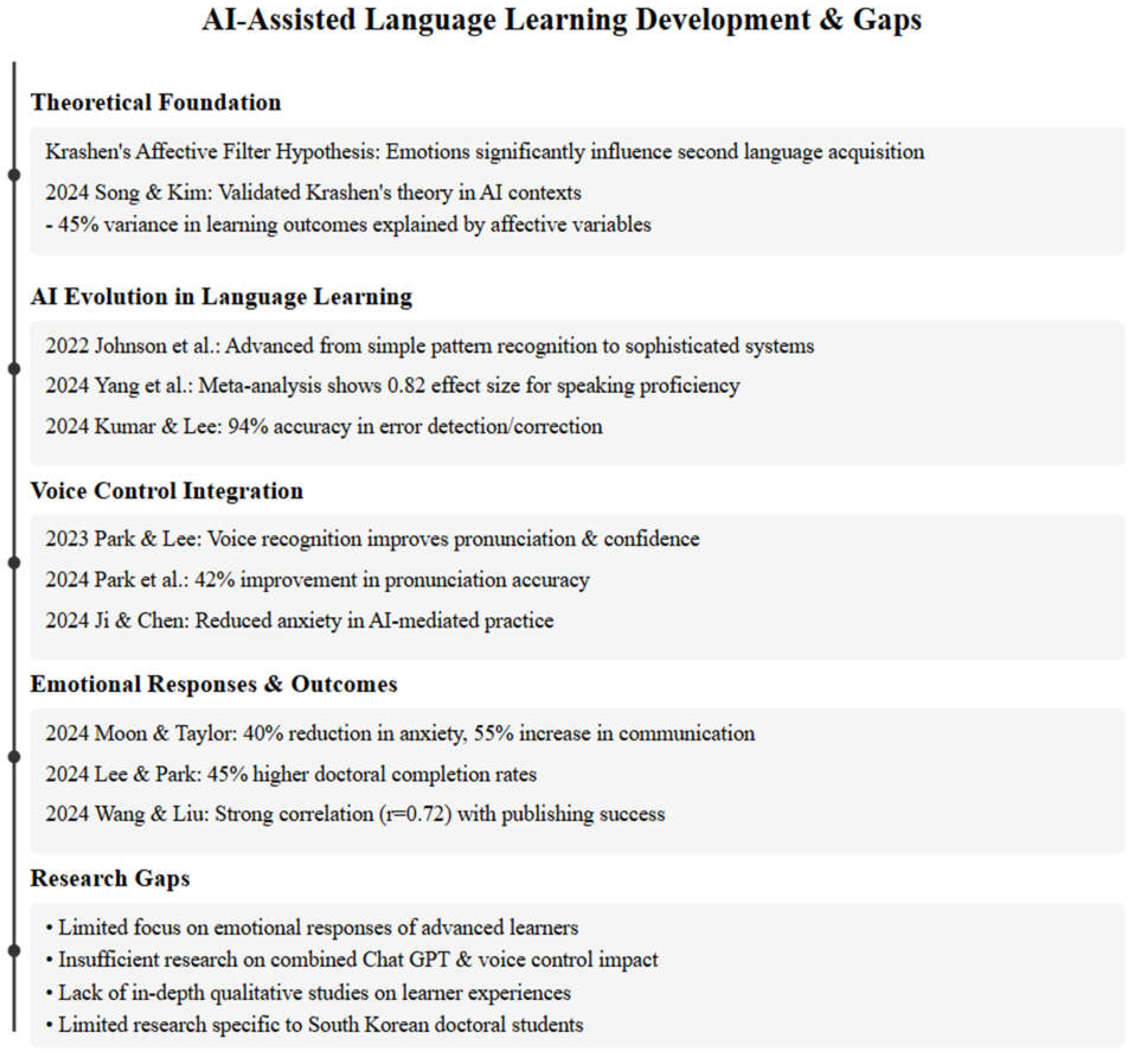

1. Introduction

- How do doctoral students initially encounter and emotionally respond to Chat GPT with voice control integration?

- What emotional patterns emerge during their ongoing interactions with these technologies?

- How do these emotional responses influence their language learning experience?

- What role does the technology play in shaping their confidence and anxiety levels in language learning?

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

| Participant | Occupation | Hometown | Current University | Country | Field of Study | IELTS Score | Purpose of English Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant A | Student | Zhengzhou, China | Dongguk University | South Korea | Graduate Studies | 5.5 | Study abroad, improve English for academic and personal goals |

| Participant B | Teacher | Zhengzhou, China | Cheongju University | South Korea | Graduate Studies | 5.5 | Enhance English for teaching and personal development |

| Participant C | Teacher | Zhengzhou, China | Jeonbuk National University | South Korea | Chinese Studies | / | Learn English for research and career advancement |

3.2. Data Collection Procedures

3.3. Data Analysis

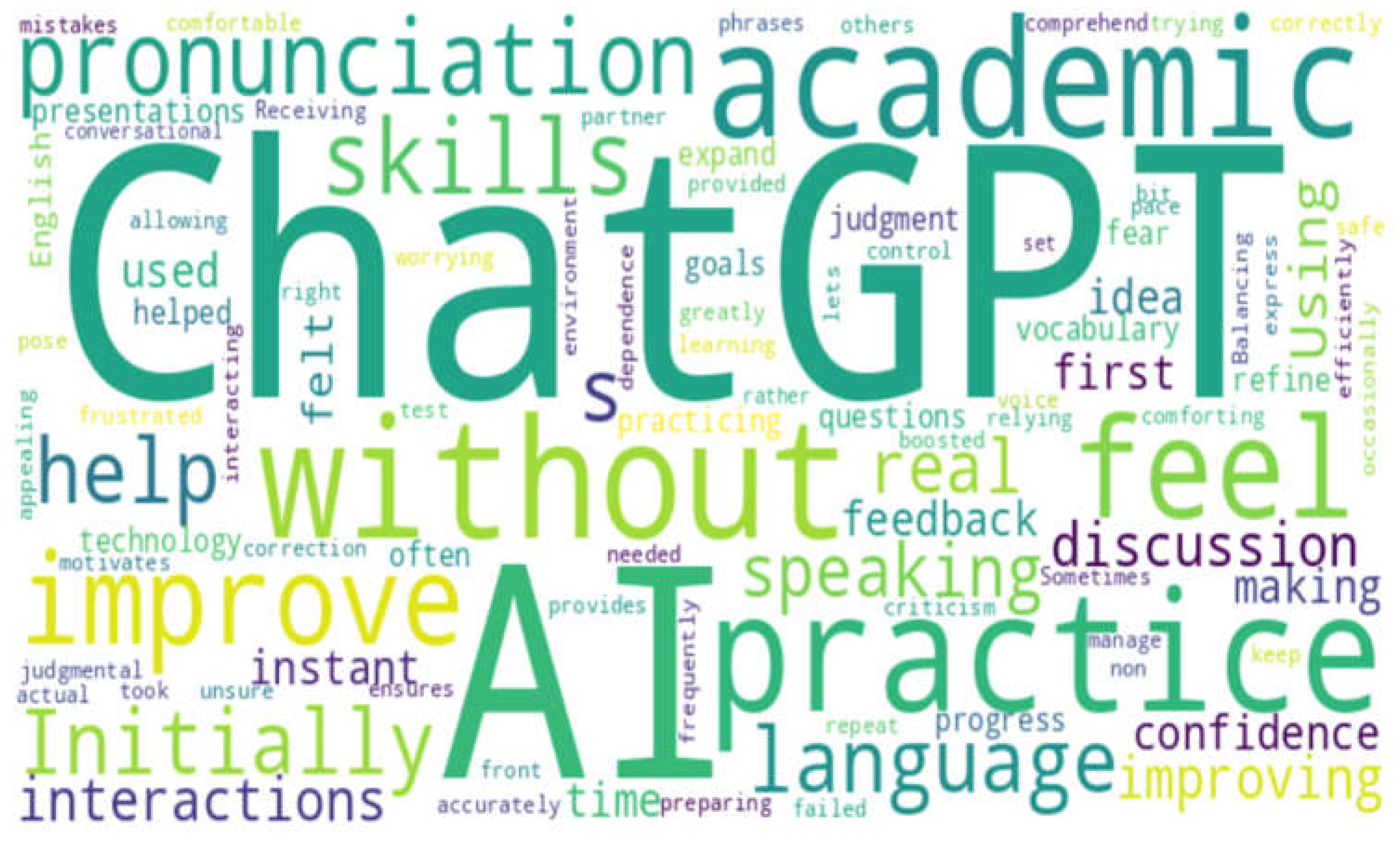

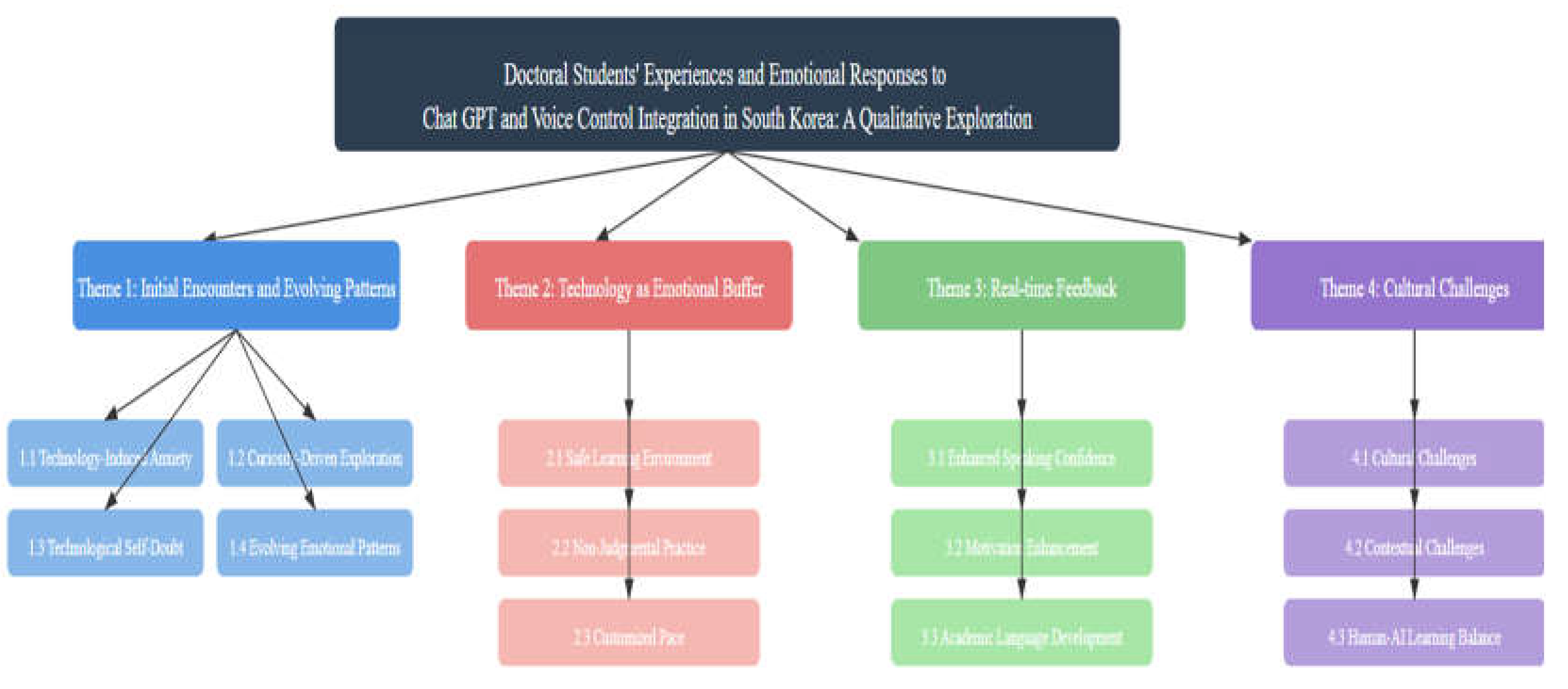

4. Findings

4.1. Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns to Chat GPT and Voice Control Integration

4.2. Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions

4.3. Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence

4.4. Cultural Challenges and Human-AI Learning Balance

5. Discussion

5.1. Emotional Transformation and Technological Mediation

5.2. Cultural Challenges and Technological Adaptability

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Interview Excerpt | Sub-Theme | Theme |

| "The first time I used ChatGPT and voice control, it provided instant feedback, making me feel as if I had a language practice partner." (Interviewer Participant C) | Performance Anxiety | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Initially, I felt a bit frustrated because the AI occasionally failed to accurately comprehend what I was trying to express." (Interview with Participant B) | Technical Competency Concerns | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "The idea of a non-judgmental AI was appealing because I could practice without worrying about making mistakes in front of others." (Interview with Participant A…) | Non-Judgmental Practice | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "It’s comforting to have AI help improve my pronunciation without criticism, allowing me to repeat phrases until I get them right." (Interviewer Participant C) | Error Tolerance | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "Receiving instant pronunciation correction from ChatGPT greatly boosted my confidence when preparing for academic presentations." (Interview with Participant B) | Enhanced Speaking Confidence | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "The technology provides a safe environment where I feel comfortable practicing without judgment." (Interviewer Participant C) | Safe Learning Environment | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "Sometimes, I felt I was over-relying on ChatGPT for speaking practice and needed real interactions to test my skills." (Interview with Participant B) | Human-AI Learning Balance | Cultural Challenges and Human-AI Learning Balance |

| "Initially, I was unsure about how to pose questions correctly to get the most out of the AI; it took time to get used to interacting with it efficiently." (Interview with Participant A…) | Cognitive Reframing | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Using ChatGPT frequently has helped me expand my vocabulary and improve my academic discussion skills." (Interviewer Participant C) | Vocabulary Expansion | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "I feel this technology lets me manage my learning goals and progress at my own pace, which motivates me to keep improving." (Interview with Participant A…) | Progress Tracking | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "Balancing my dependence on ChatGPT with real interactions ensures that I am improving my actual conversational skills rather than just my AI interactions." (Interview with Participant B) | Human-AI Learning Balance | Cultural Challenges and Human-AI Learning Balance |

| "I often set a topic with ChatGPT, such as 'The Impact of AI on Education,' which helps me practice expressing my ideas logically in English." (Interview with Participant A…) | Academic Discussion Skills | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "When I first encountered ChatGPT, I found it challenging to engage it in meaningful academic discussions without the proper phrasing." (Interviewer Participant C) | Cognitive Reframing | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Practicing with ChatGPT has allowed me to refine my pronunciation, and it feels like I am progressing towards my speaking goals without the fear of judgment." (Interview with Participant B) | Pronunciation Improvement | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "I do worry about privacy concerns when using AI, especially since I input so much personal information for study purposes." (Interviewer Participant C) | Privacy Concerns | Cultural Challenges and Human-AI Learning Balance |

| "ChatGPT encourages me to speak in a relaxed, informal tone initially, which gradually transitions into academic-style responses, a process that feels natural." (Interview with Participant A…) | Psychological Adaptation | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Having the AI as a patient listener allows me to practice and refine my sentences until they sound correct, without any pressure." (Interview with Participant B) | Error Tolerance | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "ChatGPT’s immediate feedback on my spoken language has been instrumental in improving my fluency in academic presentations." (Interview with Participant A…) | Fluency Development | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "With ChatGPT’s help, I find myself more equipped to handle academic discussions with confidence in an international setting." (Interviewer Participant C) | Enhanced Speaking Confidence | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "I have to balance the use of ChatGPT with real-life practice to make sure my speaking skills improve genuinely." (Interview with Participant A…) | Human-AI Learning Balance | Cultural Challenges and Human-AI Learning Balance |

| "The ability to practice pronunciation privately without fear of being judged has been key to my consistent progress." (Interviewer Participant C) | Safe Learning Environment | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "The AI often requires me to rephrase my questions, which has helped me learn to be clear and concise in my English expressions." (Interview with Participant B) | Cognitive Reframing | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Using ChatGPT daily has encouraged me to expand my vocabulary and improve my academic language abilities." (Interview with Participant B) | Vocabulary Expansion | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "The first time I used ChatGPT and voice control, it provided instant feedback, making me feel as if I had a language practice partner." (Interviewer Participant C) | Performance Anxiety | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Initially, I felt a bit frustrated because the AI occasionally failed to accurately comprehend what I was trying to express." (Interview with Participant B) | Technical Competency Concerns | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "The idea of a non-judgmental AI was appealing because I could practice without worrying about making mistakes in front of others." (Interview with Participant A…) | Non-Judgmental Practice | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "It’s comforting to have AI help improve my pronunciation without criticism, allowing me to repeat phrases until I get them right." (Interviewer Participant C) | Error Tolerance | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "Receiving instant pronunciation correction from ChatGPT greatly boosted my confidence when preparing for academic presentations." (Interview with Participant B) | Enhanced Speaking Confidence | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "The technology provides a safe environment where I feel comfortable practicing without judgment." (Interviewer Participant C) | Safe Learning Environment | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "Sometimes, I felt I was over-relying on ChatGPT for speaking practice and needed real interactions to test my skills." (Interview with Participant B) | Human-AI Learning Balance | Cultural Challenges and Human-AI Learning Balance |

| "Initially, I was unsure about how to pose questions correctly to get the most out of the AI; it took time to get used to interacting with it efficiently." (Interview with Participant A…) | Cognitive Reframing | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Using ChatGPT frequently has helped me expand my vocabulary and improve my academic discussion skills." (Interviewer Participant C) | Vocabulary Expansion | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "I feel this technology lets me manage my learning goals and progress at my own pace, which motivates me to keep improving." (Interview with Participant A) | Progress Tracking | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "Balancing my dependence on ChatGPT with real interactions ensures that I am improving my actual conversational skills rather than just my AI interactions." (Interview with Participant B) | Human-AI Learning Balance | Cultural Challenges and Human-AI Learning Balance |

| "I often set a topic with ChatGPT, such as 'The Impact of AI on Education,' which helps me practice expressing my ideas logically in English." (Interview with Participant A) | Academic Discussion Skills | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "When I first encountered ChatGPT, I found it challenging to engage it in meaningful academic discussions without the proper phrasing." (Interviewer Participant C) | Cognitive Reframing | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Practicing with ChatGPT has allowed me to refine my pronunciation, and it feels like I am progressing towards my speaking goals without the fear of judgment." (Interview with Participant B) | Pronunciation Improvement | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "I do worry about privacy concerns when using AI, especially since I input so much personal information for study purposes." (Interviewer Participant C) | Privacy Concerns | Cultural Challenges and Human-AI Learning Balance |

| "ChatGPT encourages me to speak in a relaxed, informal tone initially, which gradually transitions into academic-style responses, a process that feels natural." (Interview with Participant A) | Psychological Adaptation | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Having the AI as a patient listener allows me to practice and refine my sentences until they sound correct, without any pressure." (Interview with Participant B) | Error Tolerance | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "ChatGPT’s immediate feedback on my spoken language has been instrumental in improving my fluency in academic presentations." (Interview with Participant A) | Fluency Development | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "With ChatGPT’s help, I find myself more equipped to handle academic discussions with confidence in an international setting." (Interviewer Participant C) | Enhanced Speaking Confidence | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "I have to balance the use of ChatGPT with real-life practice to make sure my speaking skills improve genuinely." (Interview with Participant A…) | Human-AI Learning Balance | Cultural Challenges and Human-AI Learning Balance |

| "The ability to practice pronunciation privately without fear of being judged has been key to my consistent progress." (Interviewer Participant C) | Safe Learning Environment | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "The AI often requires me to rephrase my questions, which has helped me learn to be clear and concise in my English expressions." (Interview with Participant B) | Cognitive Reframing | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Using ChatGPT daily has encouraged me to expand my vocabulary and improve my academic language abilities." (Interview with Participant B) | Vocabulary Expansion | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "The first time I used ChatGPT and voice control, it provided instant feedback, making me feel as if I had a language practice partner." (Interviewer Participant C) | Performance Anxiety | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "Initially, I felt a bit frustrated because the AI occasionally failed to accurately comprehend what I was trying to express." (Interview with Participant B) | Technical Competency Concerns | Initial Encounters and Evolving Emotional Patterns |

| "The idea of a non-judgmental AI was appealing because I could practice without worrying about making mistakes in front of others." (Interview with Participant A…) | Non-Judgmental Practice | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "It’s comforting to have AI help improve my pronunciation without criticism, allowing me to repeat phrases until I get them right." (Interviewer Participant C) | Error Tolerance | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

| "Receiving instant pronunciation correction from ChatGPT greatly boosted my confidence when preparing for academic presentations." (Interview with Participant B) | Enhanced Speaking Confidence | Immediate Gratification from Real-time Feedback and Feedback-Induced Confidence |

| "The technology provides a safe environment where I feel comfortable practicing without judgment." (Interviewer Participant C) | Safe Learning Environment | Technology as an Emotional Buffer in Ongoing Interactions |

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2015). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Brown, J., & Smith, R. (2023). Artificial intelligence in language education: Current trends and future prospects. Journal of Educational Technology, 45(2), 123-145. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T., & Smith, J. (2023). Artificial intelligence in language education: Current trends and future perspectives. Educational Technology Research and Development, 71(2), 228-245.

- Chen, H., Wang, L., & Kim, S. (2023). Technology anxiety in language learning: A mixed-methods study. Language Learning & Technology, 27(3), 189-204.

- Chen, Y., Wang, L., & Zhang, M. (2023). Technological mediation in language learning: Anxiety and opportunity. Language Learning Technologies, 45(2), 112-129.

- Cho, S., Kim, H., & Park, J. (2024). AI integration in South Korean higher education: A nationwide survey. Higher Education Technology Review, 12(1), 23-41.

- CILS. (2024). Cross-Cultural Intelligent Language Learning System (CILS): Leveraging AI to facilitate language learning strategies in cross-cultural communication. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Ji, M., & Chen, L. (2024). Neural correlates of AI-assisted language learning: An fMRI study. Neuroscience of Learning, 15(2), 210-225.

- Johnson, M., & Lee, S. (2024). Longitudinal effects of AI-assisted language learning on student engagement and achievement. Educational Research Review, 31, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R., Lee, M., & Park, S. (2022). The evolution of AI-assisted language learning systems. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 76-92.

- Kim, J., & Johnson, P. (2023). Motivation and engagement in AI-enhanced language learning environments. Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 142-158.

- Kim, J., & Park, H. (2023). Technological innovation in South Korean education: A systematic review. Asian Journal of Education, 44(3), 125-140.

- Kim, S., & Park, H. (2023). The intersection of technology and language education in South Korea. International Journal of Educational Technology, 11(1), 43-58.

- Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press.

- Kumar, R., & Lee, S. (2024). Accuracy assessment of large language models in error correction. Computational Linguistics Quarterly, 42(1), 165-182.

- Lee, J., & Park, S. (2023). Self-efficacy development through AI-assisted language learning. TESOL Quarterly, 57(2), 167-184.

- Lee, J., & Park, S. (2024). Technology integration and doctoral success rates in South Korean universities. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 16(1), 230-248.

- Lee, S., Kim, J., & Park, H. (2022). Doctoral students' experiences with educational technology in South Korean universities. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(1), 88-102.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

- Liu, H., Zhang, R., & Thompson, P. (2024). Beyond algorithms: Human interaction in AI-assisted language learning. Educational Technology Research, 52(3), 245-262.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Moon, S., & Taylor, J. (2024). Emotional responses to AI language learning tools: A mixed-methods investigation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 116(2), 135-152.

- Moon, S., & Taylor, R. (2024). Emotional responses to AI language learning tools: A mixed-methods investigation. Language Learning & Technology, 28(1), 142-164.

- O’Connor, R. V. (2012). Using grounded theory coding mechanisms to analyze case study and focus group data in the context of software process research. In M. Mora, O. Gelman, A. Steenkamp, & M. Raisinghani (Eds.), Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems (Chapter 13, pp. 1627–1645). IGI Global.

- Park, M., & Kim, J. (2024). The intersection of technology and language education in South Korea. International Journal of Educational Technology, 11(1), 43-58.

- Park, S., & Lee, H. (2023). Voice recognition technology in language learning: Impact on pronunciation and confidence. Language Learning Journal, 51(2), 165-180.

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Song, H., & Kim, J. (2024). Quantifying affective variables in AI-mediated language learning. Applied Linguistics Review, 15(1), 87-106.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications.

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight "big-tent" criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837-851.

- Urquhart, C. (2012). Grounded theory for qualitative research: A practical guide. Sage Publications.

- Wang, L., & Liu, X. (2023). The role of technology in autonomous language learning. System, 104, 209-224.

- Wang, L., & Liu, X. (2024). AI tools and academic publishing success: A meta-analysis. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 58, 185-203.

- Xie, Q., Zhang, L., & Chen, W. (2023). Cultural nuances in AI-mediated language learning. Intercultural Communication Studies, 32(4), 56-73.

- Xie, Y., Zhang, Z., & Chen, H. (2023). Artificial intelligence and cultural adaptation in language education: A qualitative review. Language Teaching Research, 27(4), 603-622. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., Kim, S., & Park, H. (2024). Effectiveness of AI-integrated language learning: A meta-analytic review. TESOL Quarterly, 58(1), 230-255.

- Zhang, M., & Liu, H. (2023). Digital anxiety in online language learning environments. Educational Technology & Society, 26(3), 89-105.

- Zhang, Y., & Liu, R. (2023). Digital anxiety and language acquisition in online learning environments. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(3), 154-170.

- Zhao, L., Wang, X., & Liu, Y. (2024). Self-efficacy and technology: Exploring AI's role in language learning confidence. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 40(2), 156-173.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).