1. Introduction

Generative artificial intelligence has been influencing our daily lives both personally and professionally. These tools support us in performing multiple tasks, such as making queries, generating ideas, and creating stories, images, or videos. Among them are several options currently available, including ChatGPT (Roumeliotis & Tselikas, 2023), Gemini (Team et al., 2024), and Copilot (Wermelinger, 2023), among others. All these developments are referred to as Large Language Models (LLMs), which are models trained with large volumes of text to process and generate natural language. These developments are considered part of the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP). It is known that NLP developments enable models to “understand”, generate, and analyze human language. This is a great advantage as it allows us to interact with LLMs using natural language rather than code, eliminating the need for programming skills to use or interact with them.

In this context, the concept of a “prompt” emerges, referring to a request or stimulus text designed to facilitate interaction between the user and an LLM. Now, although each LLM is focused on different use cases, such as content creation, customer support, language translation, etc., they all share one common characteristic: robustness against prompt errors (Bryant et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2024). However, to what extent is this true?

To test the performance of LLMs, they are generally assessed using benchmarks for specific tasks such as Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU) for multitask accuracy (Hendrycks, Burns, Basart, et al., 2021), MATH (Hendrycks, Burns, Kadavath, et al., 2021) for mathematical problems, HumanEval (M. Chen et al., 2021) for coding, Multilingual Grade School Math (MGSM) for multilingual capabilities (Shi et al., 2022), among others. However, these tests rely on the entire input context being relevant and do not necessarily assess how the prompt is formulated. This topic is related to the Prompt Engineering technique, which focuses on the design, structure and optimisation of text inputs (prompts) to elicit accurate and relevant responses aligned with the user’s intent in LLMs. Prompt Engineering evaluates robustness against prompt variability, ambiguity, context shifts, and other factors (B. Chen et al., 2024). A well-known benchmark for evaluating prompts is the BIG-bench (Srivastava et al., 2023), which includes tasks such as Understanding Grammar of Unseen Words. This task aims to assess whether LLMs can infer the grammatical role of non-existent pseudo-words, but which have orthographic and phonetic similarity to real words (Srivastava et al., 2023). Also, Sing et al. (2024) analyzed the robustness of prompts in Language Error Correction (LEC) using a synthetic database with corrupted data to find out how distant the embedding of the corrupted text is from its correct counterpart. Therefore, current research is about testing LLMs with defined benchmarks for specific tasks. However, they have not focused on a linguistic and/or grammatical analysis at the level of real users of generative AIs.

It is known that the training of LLMs has had to address, among other challenges, the ability to correctly interpret poorly written texts; otherwise, human-machine interaction would be significantly constrained. Therefore, the ability of LLMs to interpret texts despite grammatical errors raises important questions: To what extent does this capability hold? Does it apply consistently across all languages? What are its limitations?

Although, as users, we know that it is not crucial to write a prompt with perfect grammar because models can interpret more informal instructions and correct grammatical deficiencies to generate a coherent response (Singh et al., 2024), this raises the question: Will language and grammar abilities continue to be important? Will grammar remain a relevant concern in education? Understanding this issue is particularly relevant in the context of higher education students, as they will be the ones expected to harness the full potential of these emerging AI tools.

At the same time, these models are known to be robust to different languages. Mixed-language data has been implemented, significantly enhancing the ability to process prompts and generate responses in other languages (Fang et al., 2023). Nevertheless, how effective are the responses when the prompt is written in a language other than English? A decrease in performance is expected, given that it remains unclear whether these models, primarily trained in English, can manage the complexities of other languages. For example, can these models infer correctly when the prompt is written in a verb mood that does not exist in English? In the case of Spanish, the subjunctive mood plays a crucial role in expressing wishes, commands, possibilities, opinions, and ambiguities, often describing situations that have not yet occurred. However, this mood does not exist in English, so how “good” can an LLM answer be when it is written in the Spanish subjunctive mode? To the best of the authors' knowledge, no study has been conducted that focuses exclusively on the role of the user's non-English grammar and its impact on LLM responses.

Although our research could be explored from a variety of experimental groups—such as the general population, young people, older adults, or individuals in the field of computer science, each offering its own scientific value—we chose to address it from the perspective of higher education students. We consider that this is a young age group, who has experience in the use of technologies and could handle our data collection methodology well (Chan & Hu, 2023; Overono & Ditta, 2023; Saúde et al., 2024). In addition, it is interesting from the authors' point of view to know how our students interact with the LLMs to implement possible improvements in future work to increase their learning.

Considering the background presented, this study proposes an exploratory investigation to understand how the language and grammar abilities of Chilean higher education students influence the quality of the responses provided by ChatGPT (free version), considering the use of Spanish.

2. Materials and Methods

The material used to collect the results was a questionnaire and the analysis was based on a descriptive exploratory study methodology. The details will be presented in the following points.

2.1. Data Collection

The sample of this research was composed of 104 higher education students from the Biobío Region, whose participation was not randomly selected but depended on the possibilities of access that were available in various educational institutions in the region.

The selection criteria followed a convenience sampling approach, where participants were recruited based on the accessibility and availability of the collaborating educational institutions (Etikan, 2016). Students came from three different careers, including areas of study such as rehabilitation and computer science, allowing for a diverse representation of different areas of knowledge.

Although the sample is not probabilistic, it is considered representative within the context of this study (exploratory analysis), as it includes students with different levels of familiarity with the use of Generative Artificial Intelligence. This selection strategy allows us to obtain a broad perspective on the writing strategies used by students, despite the limitations imposed by the non-randomness of the sample.

2.2. Validation of the Evaluation Instrument

To ensure the content validity of the evaluation instrument used in this research, a consensus was reached with three experts, one of whom is a specialist in linguistics, another is an expert in artificial intelligence and the third is an evaluation specialist with experience in the use of technologies. The resulting evaluation guideline is a matrix that is divided into a theoretical category, a theoretical subcategory, and the prompts evaluation questions.

The judgment matrix was distributed to six experts, of whom four agreed to participate in the evaluation of the matrix. The four experts met the minimum inclusion criteria, namely that they were university academics, held a degree, and worked in the fields of linguistics or speech therapy.

The evaluation criteria established by the judges are threefold: sufficiency, relevance, and clarity of each evaluation question. To determine the degree of consensus among the judges, Aiken's V (Aiken, 1985; Penfield & Giacobbi, Jr., 2004) is employed to evaluate the representativeness of the questions concerning the construct under examination.

Aiken's V values range from .5 to 1, with a validity threshold of .7 or above. This indicates a high degree of agreement among judges regarding the adequacy, relevance, and clarity of the items (see

Table A1).

The outcome of the changes proposed by the experts is detailed below and the instrument is presented in two parts. Criteria A1, A2, and B correspond to the dependent variables to be measured (see

Table 1). Criteria C, D, and E define the independent variables (see

Table 2).

The subjective judgment of the prompt written according to the instruction for the activity proposed by the evaluators was considered. These ratings were achieved, moderately achieved, and not achieved. The “achieved” ratings indicated that a prompt was complete in content, meaning it was coherent and complete: the prompt followed the instructions provided by the evaluators (e.g. giving context or motivation) and met all the requirements of the activity (e.g. including keywords, requesting structure, etc.). The “moderately achieved” rating is considered a prompt to be missing something, or the instructions or incomplete addressing of the requirement. The rating “not achieved” considered the responses unsatisfactory in both respects (Knoth et al., 2024; White et al., 2024).

The subjective assessment of the quality of the response given by the LLM according to the delivered prompt was considered. These ratings were “achieved”, “moderately achieved”, and “not achieved”. The “achieved” ratings considered a response to be complete in content, (e.g. it included possible questions and possible answers to address the hypothetical problem posed). In addition, it had to be adequate in form to make the response easy to read. The “moderately achieved” ratings considered a response to be lacking something. The ratings “not achieved” considered responses unsatisfactory in both content and form (i.e. incomplete) (Johnson et al., 2023).

The mean length of utterances MLU (Promedio de longitud de los enunciados, PLE) is an index traditionally used to measure the level of language development in children. It measures the length of utterances based on the assumption that structural complexity, i.e. the range of linguistic programming, is manifested in an increase in the number of elements that make up an utterance (Pavelko et al., 2020; Pavez, 2002; Soler et al., 2023).

Orthography and punctuation are observable features of written form that are governed by a set of rules for the writing of a language. Criterion C seeks to assess issues of form in the writing of the prompt, which is why these indicators are included (Torrego, 2015).

On the advice of the external evaluators, the consideration of colloquialisms and politeness formulas was eliminated, as they do not directly concern the form of the writing, nor do they correspond to the good use of the rules of writing.

Regarding variable D, the Spanish language employs three distinct verb moods, which may be described as representing different attitudes of the speaker. These moods correspond to the voice or attitude of the speaker and are indicated in the verb conjugation. The indicative mood is the most prevalent and is used to discuss matters related to reality, facts, or objective truths. It is typically employed for narration, information conveyance, and description. The imperative mood, on the other hand, is used to give commands or directives to the addressee, aiming to elicit a specific action or response. In other words, it is employed to express orders, commands, requests, or advice. Together with the indicative, these are the moods that speakers typically utilize first in their language development.

The subjunctive mood is a feature of many Romance languages and is employed to convey a range of meanings, including doubt, desire, emotion, and hypothesis. The complexity of the subjunctive mood lies in its capacity to express subjectivity, uncertainty, or desire. In other words, the verb will express unrealities, possibilities, or desires, rather than verifiable or objective questions (Gjenero, 2024; Muñoz De La Virgen, 2024; Vyčítalová, 2024).

The expert reviewers highlighted a potential issue with participants' comprehension of this distinction. However, the use of these should be spontaneous. Participants don't need to possess expert knowledge of this distinction, as native speakers of Spanish utilize them naturally and modulate them following their intended meanings.

A linguistic researcher with expertise in morphosyntactic studies conducted the classification of the verbal moods used in the prompt. Regarding variable E, the traditional approach to measuring sentence complexity is based on the number of verbal syntactic elements present in an utterance. In this paradigm, a low level of grammatical complexity is indicated by the exclusive use of simple sentences. Given that there is only one conjugated verb in the utterance, the use of coordinated and subordinate sentences is deemed to be more complex, as it necessitates the utilization of two semantically connected conjugated verbs. Sentences and coordinated sentences are analogous to complex or compound sentences, and the deployment of these or their combinations is associated with elevated syntactic structural management demands (Brown et al., 2021; Radford, 2023).

Given the reservations expressed by experts regarding the methodology employed in establishing sentence complexity, the classification of sentence types in each prompt was conducted manually. A linguistic researcher with expertise in morphosyntactic studies conducted this research.

2.3. Procedure

The data collection procedure was carried out between August and September 2024. The activity began with a welcome to the students, where the context of the study and the research objectives were explained to them. Before starting, students read the consent form and those who were willing to complete the questionnaire gave their consent. Next, the questionnaire was applied. To complete it, students used their portable devices such as cell phones or tablets. It was a structured questionnaire that consisted of several sections designed to collect both quantitative and qualitative information about students' interaction (prompt) with ChatGPT in its free version. Thus, if only some students have access to paid versions, possible biases due to the use of enhanced versions are eliminated. The first section of the questionnaire collected basic demographic data, such as age, gender, educational institution, career, and year of study. In addition, a question about the participants' previous experience with ChatGPT was included, to contextualize the answers and analyze possible differences in the ways of writing the prompt according to the level of familiarity with the tool. The second part of the questionnaire was focused on a case analysis. Students were faced with a specific situation that they had to solve by interacting with ChatGPT. We decided to use a transversal case for all higher education students regardless of establishment and type of career: A job interview in their area of study. The instructions were:

Situation: You have a job interview for an internship at a company in your field of study. You need to be prepared for the possible questions you will be asked and how to answer them effectively.

Objective: Use ChatGPT to get examples of common job interview questions and tips on how to answer them.

In the third section, the level of student satisfaction with the answers provided by the AI was evaluated. The entire activity lasted approximately 35 minutes.

The students accessed the ChatGPT website exclusively from their mobile devices or personal computers while in their respective classrooms. The questionnaire was administered via Google Forms, which allowed for efficient and anonymous data collection. This combination of tools made it easier for students to participate in the study directly from the educational setting, ensuring that everyone had controlled access to the same technological conditions.

After opening the questionnaire and filling in the instructions, students were asked to first indicate whether they understood the case analysis and then write the text (prompt) they would use to interact with the AI. The prompt had to be written in our questionnaire and then copied and pasted into the free ChatGPT platform. This generated an answer that had to be copied exactly from the ChatGPT website back to the questionnaire.

Afterward, they were to carefully read the answer and give their evaluation of their satisfaction with it. They were to indicate whether they were satisfied or dissatisfied with the ChatGPT response. If the evaluation was “yes” the test ended. If the answer was “no”, the option to rewrite another prompt with the same instructions as in the previous step was displayed. This ends until a positive evaluation is obtained from the student or up to a maximum of 7 questions. This would allow us to analyze not only the prompt text but also the response obtained and the user's satisfaction with the tool.

Regarding ethical aspects, the study complied with the informed consent rules. Before beginning, students were asked to read and agree to participate voluntarily, with the option to withdraw at any time without consequences. The informed consent, included in the form, detailed that the information collected would be treated anonymously and used exclusively for academic purposes. It was guaranteed that personal data would not be used to identify participants to preserve their confidentiality.

At the end of data collection, data analysis was initiated using the Content Assessment Instrument (validated by expert judgment). This task was carried out by a linguist with expertise in morphosyntax (i.e. grammar) who analyzed each participant's response individually. This assessment was tabulated in a database to enable data analysis.

2.4. Data Analysis

Firstly, a descriptive analysis of the data was carried out. At the moment of analyzing the texts used to interact with the AI, we determined to analyze the following dependent and independent variables.

The dependent variables were three: the subjective judgment of the prompt (i.e. ordinal categorical variable); the subjective judgment of the quality of the response given by the LLM (i.e. ordinal categorical variable); and the length mean of the utterances (index: Amount of words / Number of utterances). The subjective judgment of the prompt was written according to the instructions for the activity proposed by the evaluators. Also, the subjective assessment of the quality of the response given by the LLM according to the delivered prompt was considered. The criteria were achieved, moderately achieved, and not achieved. The length of the utterances of the prompt was calculated with the number of words in the utterances divided by the number of sentences.

In the second place, the Kruskal Wallis ANOVA was employed for each independent variable: the use of standards in writing (i.e. no orthography or punctuation errors vs. orthography errors in the writing of the prompt vs. punctuation errors in the writing of the prompt vs. both types of errors in the writing of the prompt); verbal moods or attitudes of the speaker (use of indicative vs. subjunctive vs. imperative moods vs. use of two verb moods vs. use of three verb moods); sentence complexity (use of simple sentences vs. use of coordinated sentences vs. use of subordinate sentences vs. use of two types of sentences vs. use of three types of sentences).

The prompt written by the participants was analyzed in terms of aspects of form, where the occurrence or non-occurrence of orthographic errors and/or errors in the use of punctuation was considered. This variable was called “Use of standards in writing”.

In addition, the prompt was described in terms of the use of verbal moods in the writing. This criterion considered the use of indicative mood, subjunctive mood, and imperative mood in the wording of the prompt. Separately, the type of sentences used in the prompt was considered: simple, coordinated, and subordinate sentences.

Jamovi software version 2.3 (2022) and IBM SPSS 27 Statistics were used for the analyses.

3. Results

First, a descriptive analysis of the data was performed. Second, Kruskal Wallis ANOVA was performed for each dependent variable.

3.1. Subjective Judgment of the Prompt Written According to the Instructions for the Activity

In the first place, the subjective judgment of the prompt written according to the instruction for the activity proposed by the evaluators was considered. These ratings were achieved, moderately achieved, and not achieved (see

Table 1). For these analyses, all inattentive prompts were excluded, i.e. those that were not related in any way to the activity proposed to the participants. 65% of the data was included.

The overall mean per objective achievement was 1.99 (.85 SD). The frequency of ranking 1 (achieved) was 36.8%, ranking 2 (moderately achieved) was 27.9%, and ranking 3 (not achieved) was 35.3%. This was sensible to the sex of participants (χ² (1) = 5.82, p = .016). Male participants (n = 33) showed a benefit (mean of 1.73; .139 SD) over the female participants (n = 35; 2.23; .143 SD) on the subjective judgment of the prompt. The age variable that was grouped (18-19 vs. 20-21 vs. 22 or older) did not have a significant effect.

Also, data were taken from two higher education institutions (Private University vs. Traditional University). Traditional University participants (n = 28) showed a benefit (mean of 1.64; .780 SD) over the Private University participants (n = 33; 2.23; .131 SD) on the subjective judgment of the prompt. The class (first vs. second, vs. third, vs. fourth) of the participants was not significant, but the numerical trend showed that the fourth class (1.60; .680 SD) had an advantage over the first (2.18; .885 SD) and second classes (2.17; .753 SD).

Table 3.

Frequencies (f) in percentage for each variable, media, and median for the subjective judgment of the prompt written according to the instruction to the activity proposed by the evaluators (mean prompt).

Table 3.

Frequencies (f) in percentage for each variable, media, and median for the subjective judgment of the prompt written according to the instruction to the activity proposed by the evaluators (mean prompt).

| Variable |

Conditions |

f |

Mean, (SD) of prompt |

Range and median of prompt |

Use of standards in writing

χ² (3) = 1.43, p = .700 |

No orthography or punctuation errors. |

11.8% |

2.00

(0.92) |

2 (1-3)

2 |

| orthography errors in the writing of the prompt. |

26.5% |

2.17

(0.78) |

2 (1-3)

2 |

| punctuation errors in the writing of the prompt. |

26.5% |

1.83

(0.92) |

2 (1-3)

1.5 |

| Both types of errors in the writing of the prompt. |

35.3% |

1.96

(0.85) |

2 (1-3)

2 |

Verbal moods or attitudes of the speaker

χ² (3) = 13.4, p = .004 |

Use of indicative mood |

51.5 % |

2.23

(0.87) |

2(1-3)

3 |

| Use of subjunctive mood |

7.4 % |

2.60

(0.54) |

1(2-3)

3 |

| Use of imperative mood |

0% |

|

|

| Use of two verb moods |

36.8 % |

1.64

(0.70) |

2 (1-3)

2 |

| Use of three verb moods |

4.4 % |

1.00

(0.00) |

0 (1-1)

1 |

Sentence complexity

χ² (4) = 17.4, p = .002 |

Use of simple sentence |

29.4 % |

2.45

(0.52) |

2 (1-3)

3 |

| Use of coordinated sentences |

2.9 % |

1.5

(1.00) |

1 (1-2)

1.5 |

| Use of subordinate clauses |

8.8 % |

2.67

(0.40) |

1 (2-3)

3 |

| Use of two types of sentences |

38.2 % |

1.81

(0.87) |

2 (1-3)

2 |

| Use three types of sentences |

20.6 % |

1.43

(0.83) |

2 (1-3)

1 |

The prompt written by the participants was analyzed in terms of aspects of form (i.e. use of standards in writing), where the occurrence or non-occurrence of orthographic and punctuation errors is considered. The more frequent prompts were those with orthographic errors and those with both errors (orthographic and punctuation). No significant differences were observed.

However, there was an observed significant effect for the variable verbal moods or attitudes of the speaker in the prompt (χ²(3) = 13.4, p = .004). The indicative mood was employed in 51.5% of prompts, with a median of 3 (range: 1-3). The subjunctive mood was observed in 7.4% of prompts, with a median of 3 (range: 2-3). The imperative mood was not observed in any of the prompts tested, with a zero percent occurrence. In 36.8% of prompts, two moods were combined, with a median of 2 (range: 1-3). Additionally, 4.4% of prompts employed three verb moods, with a median of 1 (range: 1-1).

The findings indicate that the exclusive utilization of the indicative or subjunctive mood is associated with diminished objective achievement, as evidenced by higher evaluations (medians of 3). Conversely, prompts that combine two moods demonstrate a more favorable tendency (median of 2), while those that employ three verbal moods obtain the optimal evaluation (median of 1), reflecting a greater alignment with the target.

Also, there was an observed significant effect for the variable sentence complexity (χ²(4) = 17.4,

p = .002) in the prompt (see

Table 1). A total of 29.4% of the prompts employed a simple sentence structure, with a median of 3 sentences (range: 1-3), which is indicative of a less successful outcome in achieving the desired objective. The use of coordinated sentences was observed in 2.9% of prompts, with a median of 1.5 (range: 1-2), indicating superior performance. Subordinate sentences were observed in 8.8% of prompts, with a median of 3 (range: 2-3), indicating a lower level in achieving the desired objective.

A total of 38.2% of the prompts exhibited a combination of two structural types, with a median of 2 (range: 1-3). 20% of the prompts employed all three structures, with a median of one (range: one to three), reflecting the optimal performance and the highest level of achievement of the objective.

In conclusion, the use of only simple sentences or sentences with subordination resulted in lower objective achievement, as indicated by a median of 3. Conversely, prompts that employed coordinated sentences or a combination of three types of structures demonstrated the most favorable evaluations, with medians of 1.5 and 1, respectively, reflecting greater success in meeting the aim.

3.2. Subjective Judgment of the Quality of the Response Given by the LLM

In the second place, the subjective judgment of the quality of the response given by the LLM was considered. These ratings were achieved, moderately achieved, and not achieved (see

Table 2). For these analyses, all data were included 100%.

The overall mean per target achievement was 1.66 (.74 SD). The frequency ranking 1 (achieved) was 50.5%, ranking 2 (moderately achieved) was 33%, and ranking 3 (not achieved) was 16.5%.

The subjective judgment of the response was not sensible to the sex of the participants. Male participants (n = 46) showed a mean of 1.61 (.745 SD) and the female participants (n = 57) showed a mean of 1.70 (.755 SD) on the subjective judgment of the response. The age variable that was grouped (18-19 vs. 20-21 vs. 22 or older) did not have a significant effect.

Also, Traditional University participants (n = 37) and Private University participants (n = 66) don't show a significant difference in the subjective judgment of the response (1.54 vs. 1.73 respectively). In addition, the observation of the class of participants (first vs. second, vs. third, vs. fourth) showed no significant differences.

Table 4.

Frequencies (f) for each variable, media (SD), median, and range for the subjective judgment of the quality of the response given by the LLM (mean Response).

Table 4.

Frequencies (f) for each variable, media (SD), median, and range for the subjective judgment of the quality of the response given by the LLM (mean Response).

| Variable |

Conditions |

f |

Mean (SD) of response |

Range and median of response |

Use of standards in writing

χ² (3) = 7.78, p = .051 |

No orthography or punctuation errors. |

18.4% |

1.95

(0.84) |

2(1-3)

2 |

| orthography errors in the writing of the prompt. |

30.1% |

1.81

(0.74) |

2(1-3)

2 |

| punctuation errors in the writing of the prompt. |

21.4% |

1.41

(0.73) |

2(1-3)

1 |

| Both types of errors in the writing of the prompt. |

30.1% |

1.52

(0.62) |

2(1-3)

1 |

Verbal moods or attitudes of the speaker

χ² (4) = 18.7, p < .001 |

Use of indicative mood |

62.1 % |

1.73

(0.78) |

2(1-3)

2 |

| Use of subjunctive mood |

6.8 % |

2.0

(0.57) |

2(1-3)

2 |

| Use of imperative mood |

1.9 % |

3.0

(0) |

0(3-3)

3 |

| Use of two verb moods |

26.2 % |

1.37

(0.56) |

2(1-3)

1 |

| Use of three verb moods |

2.9 % |

1.0

(0) |

0(1-1)

1 |

Sentence complexity

χ² (4) = 18.7, p < .001 |

Use of simple sentence |

44.7 % |

1.91

(0.78) |

2 (1-3)

2 |

| Use of coordinated sentences |

2.9 % |

1.33

(0.57) |

1 (1-2)

1 |

| Use of subordinate clauses |

10.7 % |

2

(0.77) |

2 (1-3)

2 |

| Use of two types of sentences |

27.2 % |

1.43

(0.63) |

2 (1-3)

1 |

| Use three types of sentences |

14.6 % |

1.13

(0.35) |

1 (1-2)

1 |

The response of the IA was analyzed in terms of the use of standards in writing in the prompt (i.e. orthographic and/or punctuation errors). The more frequent responses were those associated with the prompt with both types of errors (orthography and punctuation). No significant differences were observed for this variable (χ² (3) = 1.43, p = .700).

However, there was an observed significant effect on the response of the IA depending on the variable verbal moods or attitudes of the speaker in the prompt (χ² (3) = 13.4, p = .004). The indicative mood in the prompt was observed in 62.1% of responses, with a median of 2 (range: 1-3), indicating responses of moderate achievement. The subjunctive mood in the prompt was employed in 6.8% of the responses, with a median of 2 (range: 1-3), indicating that these responses were also moderate achievement. The imperative mood in the prompt was employed in only 1.9% of the responses, with a median of 3 (range: 3-3), indicating no achievement.

The combination of two verb moods in the prompt was employed by 26.2% of respondents, with a median of 1 (range: 1-3), indicating response achievement. The use of three verb moods in the prompt was evidenced in 2.9% of responses, with a median of 1 (range: 1-1), indicating also response achievement.

These results suggest that responses to prompts that combine two or three verbal moods were evaluated most favorably (median of 1), suggesting that these responses were achieved. In contrast, responses utilizing only the imperative mood in the prompts were evaluated as not achieved (median of 3). Responses employing the indicative or subjunctive mood in the prompt exhibited moderate achievement (median of 2).

Also, there was an observed significant effect on the response of the IA depending on the variable sentence complexity in the prompt (χ² (4) = 17.4,

p = .002) (see

Table 2). A total of 44.7% of responses from the prompt were composed of simple sentences, with a median of 2 (2-3). This indicates that the responses were moderately achieved. A mere 2.9% of the responses exhibited the use of coordinated sentences, with a median of 1 (range: 1-2), indicative of complete achievement. A total of 10.7% of responses included subordination, with a median of 2 (range: 1-3), indicating also moderately achievement responses.

A total of 27.2% of responses from prompts combined two sentence types, with a median of 1 (range: 1-3), indicating that these responses were achieved. The use of three sentence types on the prompt was observed in 14.6% of responses, with a median of 1 (range: 1-2), indicating complete achievement.

These findings suggest that responses from prompts utilizing coordinated sentences or a combination of two or three sentence types were the most highly evaluated (median of 1). In contrast, responses from prompts employing simple or subordinate sentences were less favorably evaluated (median of 2).

3.3. Length of the Utterances of the Prompt

In the third place, the length of the utterances of the prompt was considered. The index is calculated with the number of words in the utterances divided by the number of sentences (see

Table 3). For these analyses, all data were included 100%.

The overall mean per target achievement was 11.1 (4.85 SD). The length of the utterances of the prompt was not sensible to the sex of the participants. Male participants (n = 46) showed a mean of 11.9 (5.63 SD) and the female participants (n = 57) showed a mean of 10.50 (4.05 SD) on the subjective judgment of the response. The age variable that was grouped (18-19 vs. 20-21 vs. 22 or older) did not have a significant effect.

However, Traditional University participants (n = 37) showed a benefit (mean of 12.8; 6.09 SD) over the Private University participants (n = 66; 10.2; 3.74 SD) on the length of the utterances of the prompt. In addition, the observation of the class of participants (first vs. second, vs. third, vs. fourth) showed a significant difference. The participants of the fourth class (14.15, 6.77 SD) showed a benefit overall the first class (10.15, 3.68 SD).

The length of the utterances was analyzed in terms of the use of standards in writing (i.e. orthographic and/or punctuation errors). No significant differences were observed for this variable (χ² (3) = 6.19, p = .103)

However, there was an observed significant effect for the length of the utterances depending on the variable verbal moods or attitudes of the speaker in the prompt (χ² (4) = 39.8,

p < .001). The results described in

Table 5 suggest that responses from prompts using the imperative mood are the most concise, with a median of 5. On the other hand, responses from prompts using three verb moods had the highest length index (median of 17), indicating greater complexity and sentence length. Responses from prompts with indicative or subjunctive mood showed an intermediate level of length (median of 9), although the indicative mood showed a greater variation in the range. Finally, responses from prompts combining two verb moods also showed a high rate, with a median of 13.5, but without reaching the length of those including three moods.

Also, there was an observed significant effect for the length of the utterances depending on the variable sentence complexity in the prompt (χ² (4) = 39.8,

p < .001) (see

Table 3). The results indicate that responses from prompts comprising simple sentences exhibit the lowest length index (median 8), suggesting greater conciseness. In contrast, responses from prompts comprising subordinate and coordinated sentences exhibited higher length indices, with medians of 11 and 10, respectively. The combination of two sentence types yielded the highest index (median 13.2), reflecting a greater degree of complexity and length. In contrast, responses from prompts comprising three sentence types exhibited a median length of 12.3, also indicating a trend towards greater sentence length.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore how the characteristics of prompt writing in Spanish can influence the responses generated by an LLM (ChatGPT, free version). To explore this issue, we evaluated the subjective judgment of the prompt written according to the instructions for the proposed activity (mean prompt), the subjective judgment of the quality of the response given by the LLM, and the length of the utterances in the prompt. These variables were described according to sociodemographic covariates and then analyzed based on the following: i) the use of writing standards (form) in the prompt, ii) the verbal moods or attitudes expressed by the speaker in the prompt, and iii) sentence complexity in the prompt.

4.1. Punctuation and Orthography

The first notable finding was that the use of writing standards, such as punctuation and spelling, did not affect any of the observed dependent variables. Specifically, it had no impact on achieving the objective prompt, on the AI's response, or on the length of the utterances. This highlights how robust LMMs are nowadays in this variable, even in a language other than English.

4.2. Verbal Moods

The second finding was that the verbal moods employed in the written prompt had an impact on the three dependent variables observed. Regarding the subjective judgment of the prompt written, the results demonstrate that prompts using a combination of three moods achieve the highest objective performance. Those combining two moods show moderate success, while prompts with only the indicative or subjunctive mood achieve the lowest scores.

Regarding the subjective judgment of the response given by the IA, the results suggest that responses to prompts combining two or three verbal moods were evaluated most favorably. In contrast, responses from prompts with only the imperative mood were evaluated as not achieved; and responses to prompts employing the indicative or subjunctive were evaluated as moderate achievement.

Regarding the length of the utterances, the general trend observed in the analysis suggests that prompt employing a combination of verbal moods leads to better performance and greater achievement. This pattern highlights that greater variety in verbal moods positively impacts both the quality and complexity of the prompts and responses.

4.3. Sentence Complexity

The third finding was that the sentence complexity employed in the written prompt had an impact on the three dependent variables observed.

Regarding the subjective judgment over the written prompt, the use of only simple sentences or sentences with subordination resulted in lower objective achievement. Conversely, prompts that employed coordinated sentences or a combination of three types of structures demonstrated better evaluations, reflecting greater success in meeting the objective.

Regarding the subjective judgment of the quality of the response, the results showed that responses from prompts utilizing coordinated sentences or a combination of two or three-sentence types were the most highly evaluated. In contrast, responses from prompts employing simple or subordinate sentences were less favorably evaluated.

Regarding the length of the utterances in the prompt, the results indicate that responses from prompts comprising simple sentences exhibit the lowest length index, suggesting greater conciseness. In contrast, responses from prompts comprising subordinate and coordinated sentences exhibited higher length indices. The combination of two- and three-sentence types yielded the highest index, indicating a greater degree of complexity and length

In synthesis, the findings reveal that the use of diverse verbal moods and sentence structures significantly impacts the evaluation of both the prompt and the generated responses, as well as the length of the responses. Prompts that incorporate multiple moods and more complex sentence types achieve better results, both in terms of objective performance and subjective judgments. The diversity in linguistic features not only enhances the quality of the interaction but also influences the success of the generated text. Writing standards such as punctuation and orthography did not show any impact on the dependent variables.

4.4. Implications for How to Objectively Evaluate a Prompt Written by an Adult

Considering the observed trends, it is recommended that to evaluate a written Spanish prompt, consideration should be given to verb moods, sentence complexity, and utterance length. A post-hoc Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted, revealing that, when these three variables were considered, a single component was extracted (see

Table 6). This suggests that only one component captures enough variance to be retained. Additionally, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed to examine the structure of the factor and identify underlying patterns.

The variance of 63.9% indicates that utterance length has a high loading on the first component, which is an important factor in explaining the overall complexity of the text. However, it requires complementary information regarding verb mood and sentence complexity.

The EFA was conducted using the principal axis factoring method with oblimin rotation. This analysis identified one factor with a KMO of .65 (Pallant, 2020) and a sphericity test of χ² = 60.2, degrees of freedom (df) = 3, and significance (p < .001). McDonald's omega (ω) reliability analysis yielded a value of .73.

Therefore, if we consider the proposals in

Table 1 and

Table 2 together as an operationalisation of indicators for evaluation instruments, the evaluation of prompts should consider the subjective assessment of prompt achievement and the subjective assessment of response achievement. These two variables will focus on an overall look at the content achievement of both elements of AI interaction. Furthermore, the instrument should consider the length of utterances, verb moods used, and sentence complexity to consider aspects of writing form (structural). These have been relevant and significant for the achievement of the AI interaction objectives. Our analyses indicate that it is not informative to consider compliance with spelling and punctuation rules, as these were not significant in terms of achievement.

This evaluation instrument then allows us to assess the form of the prompt. That is, in terms of the complexity of the writing. A follow-up study must stratify the outcome of this instrument with a larger sample size. In a pilot post hoc, a scale has been established based on the Z-score of the principal component which indicates the following: the 84th percentile or higher (≥ 1.11) signifies achievement; a percentile between the 16th and 83rd (greater than -1 and less than 1.11) indicates moderate achievement; and a percentile below the 16th indicates no achievement.

These considerations can be extended to evaluations of speech form in other contexts. For example, in the field of speech therapy and linguistics. As mentioned above, sentence length is an index for assessing the level of morphosyntactic (grammatical) development in children. However, it is not used to formally assess adult language. At present, linguists and speech therapists do not have an objective protocol for assessing the morphosyntactic level in Spanish, so a subjective and qualitative assessment is generally made. The present study contributes to the assessment of the morphosyntactic level of adult speech by providing guidelines on how it can be assessed quantitatively. We have provided evidence that determining the level of complexity in writing requires considering at least sentence length, the verb forms used, and the types of sentences employed by the participants.

4.5. Implications of this Work in the Field of Higher Education

As Holmes (Holmes, 2023) suggests, it is important to recognize that the connections between AI and education are more complex than they might seem, with misunderstandings often arising due to a lack of investigations (Miao et al., 2021).

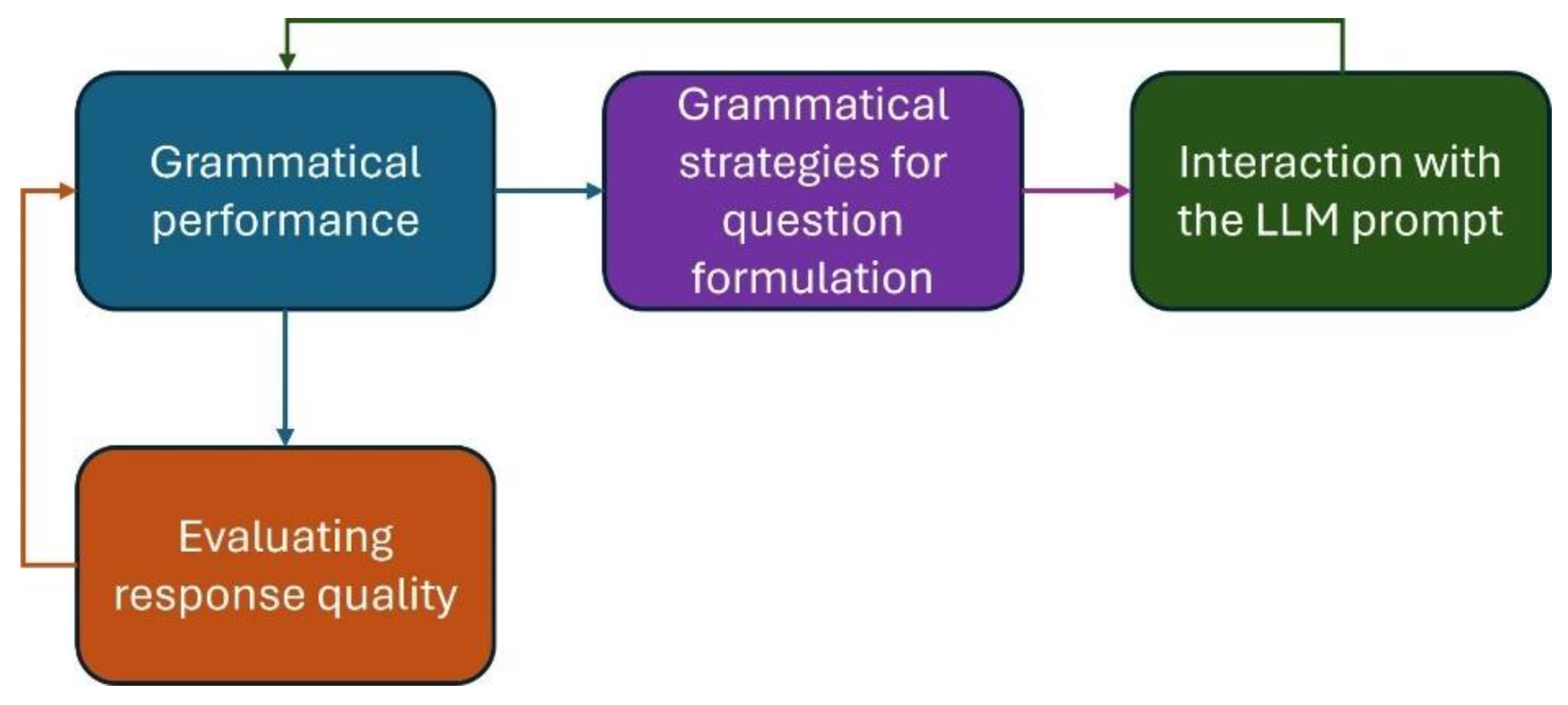

With this work, we propose that both the strategies for formulating effective questions to interact with an LLM and the quality of the responses these LLMs provide depend on students' grammatical performance. While much research focuses on prompt engineering strategies, it is important that literacy policies for the use of AI in education also incorporate the development of students' grammatical performance.

Figure 1 represents a methodological proposal that educational communities could use to enhance students' grammatical performance, enabling responsible interaction between students and LLMs. This framework highlights four essential aspects to consider in human-machine interaction: i) Grammatical performance; ii) Grammatical strategies for question formulation; iii) Interaction with the LLM prompt; iv) Evaluating response quality.

Grammatical performance, focused on the verb and its mood, influences sentence complexity. The subjunctive mood, being more complex than the indicative, presents greater challenges for non-native speakers. Compound sentences, especially subordinate ones, increase complexity by relating multiple ideas. According to our study, the choice of verbal mood and the type of sentence are linked to the length of interactions with the LLMs. Speakers with more expertise, able to combine different moods and sentence types, can generate longer and more informative messages, achieving better results in their interactions with the LLMs. Hence, the speaker’s expertise in structuring sentences is positively related to better outcomes and success in interactions with LLMs, such as ChatGPT.

Grammatical strategies for question formulation can be considered part of the prompt engineering field. A prompt is an input to a generative AI model used to guide its output (Heston & Khun, 2023; Meskó, 2023). Many studies demonstrate that more effective prompts improve the quality of responses across a wide range of tasks (Schulhoff et al., 2024). However, understanding how to use it correctly remains an emerging field, with various terms and techniques that are not necessarily well understood by students.

To evaluate the quality of responses, it is crucial that students also enhance their skills, such as critical thinking, researching, and contrasting information sources, while being able to analyze the ethical aspects and intellectual property rights involved in interactions with AI.

Finally, we can observe that all the proposed components are connected to grammatical performance. We intend to emphasize the importance of grammatical performance, as a foundational step in improving interactions with AI.

5. Conclusions

The drastic and accelerated rise of generative artificial intelligence in several areas has led both individuals and organizations to use it for solving a wide range of problems. Unlike traditional AI, generative AI manages models capable of processing language by using written instructions provided through a prompt as input.

Despite advances in this type of technology, uncertainties persist regarding what kind of abilities must be acquired to interact with LLMs. Although several studies situate discussions around prompt engineering strategies, in this work we wanted to take a step back and ask how important grammatical performances are for achieving effective responses from LLMs like ChatGPT.

In this context, the present study constitutes an initial attempt to understand the interaction between higher education students and LLMs (in this case, ChatGPT) from a linguistic perspective. Specifically, we aimed to analyze how the writing style influenced the quality of the responses provided by ChatGPT, considering the use of Spanish. In other words, how important is grammar in influencing the quality of ChatGPT's responses?

The dependent variables were three: the subjective judgment of the prompt written according to the instruction to the activity proposed by the evaluators; the subjective judgment of the quality of the response given by the LLM; and the length mean of the utterances.

The results of this exploratory study indicate that the use of varied verbal moods and sentence structures has a significant effect on both the evaluation of the prompt and the generated responses, as well as on the length of the responses. Prompts that include a wider range of moods and more complex sentence structures tend to yield better outcomes, both in terms of objective performance and subjective assessments. This linguistic diversity not only improves the quality of the interaction but also plays a key role in the success of the generated text. Interestingly, writing standards such as punctuation and orthography did not appear to affect dependent variables.

What implications could these results have for higher education, considering that technologies based on LLMs can significantly enhance students' learning experiences? In this context, we propose a framework to guide higher education communities in both the digital literacy process for professors and students, as well as in the integration of AI into the teaching-learning process. This framework highlights four essential aspects to consider in human-machine interaction: i) Grammatical performance; ii) Grammatical strategies for question formulation; iii) Interaction with the LLM prompt; iv) Evaluating response quality.

Considering the key findings of this research, the following future works could be proposed: i) the need to train LLMs with underrepresented languages; ii) understanding how students are using prompt engineering strategies; iii) exploring how students are evaluating the quality of outputs delivered by LLMs; iv) determining where higher education should focus on grammatical performances or prompt engineering; v) assessing whether natural language alone is sufficient to obtain better responses; vi) implementing the proposed framework and analyzing its outcomes with students from a sample of higher education communities.

Limitations

This study was exploratory and involved a limited sample of higher education communities from the Biobío region in Chile. Although the findings emphasize the importance of grammatical performances for interacting with LLMs, further research is needed to confirm these results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rhoddy Viveros-Muñoz and Carla Contreras-Saavedra; Data curation, Carolina Contreras-Saavedra and Carla Contreras-Saavedra; Formal analysis, Rhoddy Viveros-Muñoz, Carolina Contreras-Saavedra and Carla Contreras-Saavedra; Investigation, Rhoddy Viveros-Muñoz and Carla Contreras-Saavedra; Methodology, Rhoddy Viveros-Muñoz, José Carrasco-Sáez, Carolina Contreras-Saavedra and Carla Contreras-Saavedra; Resources, Sheny San-Martín-Quiroga; Supervision, José Carrasco-Sáez; Visualization, Sheny San-Martín-Quiroga; Writing – original draft, Rhoddy Viveros-Muñoz, José Carrasco-Sáez, Carolina Contreras-Saavedra, Sheny San-Martín-Quiroga and Carla Contreras-Saavedra; Writing – review & editing, Rhoddy Viveros-Muñoz, José Carrasco-Sáez and Sheny San-Martín-Quiroga.

Funding

The author R.VM. acknowledges support from ANID FONDECYT Postdoc through grant number 3230356. The author C.CS. acknowledges support from grant ANID Capital humano Beca Doctorado Nacional Foil 21231752 Project ID 16930.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results of 4 expert judgments for two content validity (Vo = .50 and Vo = .70) of the assessment instrument by Sufficiency (S), Relevance (R), and Clarity (C) about the variables. Only those parts of the instrument that require editing or modification are reported.

Table A1.

Results of 4 expert judgments for two content validity (Vo = .50 and Vo = .70) of the assessment instrument by Sufficiency (S), Relevance (R), and Clarity (C) about the variables. Only those parts of the instrument that require editing or modification are reported.

| |

|

mean |

V |

Vo = .50 |

Lower |

Upper |

Vo = .70 |

Decision |

| A1 The student's prompt demonstrates that he/she was able to follow the instructions given in the activity. |

S |

3.75 |

.92 |

✓ |

.6461 |

.9851 |

X |

Reassess sufficiency |

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

3.25 |

.75 |

X |

.4677 |

.9111 |

X |

Rewrite |

| A2 The answer given by the IA is satisfactory according to the given prompt. |

S |

3.75 |

.92 |

✓ |

.6461 |

.9851 |

X |

Revise sufficiency |

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

3.00 |

.67 |

X |

.3906 |

.8619 |

X |

Rewrite |

| B1 Record the number of words used in the question posed to the AI. |

S |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| B2 Record the number of sentences used in the wording of the question posed to the IA. |

S |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C1 There are orthographical errors in the wording of the prompt. |

S |

2.25 |

.42 |

X |

.1933 |

.6805 |

X |

insufficiency |

| R |

3.50 |

.83 |

✓ |

.552 |

.953 |

X |

Revise Relevance |

| C |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C2 There are punctuation errors in the wording of the prompt. |

S |

3.25 |

.75 |

X |

.4677 |

.9111 |

X |

insufficiency |

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C3 Students comply with Colloquialisms and politeness in the writing of the prompt. |

S |

2.75 |

.58 |

X |

.3195 |

.8067 |

X |

insufficiency |

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

3.75 |

.92 |

✓ |

.6461 |

.9851 |

X |

Revise writing |

| D1 The indicative mode is present in the wording of the prompt. |

S |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

3.00 |

.67 |

X |

.3906 |

.8619 |

X |

Rewrite |

| D2 The subjunctive mood is present in the wording of the prompt. |

S |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

3.00 |

.67 |

X |

.3906 |

.8619 |

X |

Rewrite |

| D3 The imperative mood is present in the wording of the prompt. |

S |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

3.00 |

.67 |

X |

.3906 |

.8619 |

X |

Rewrite |

| D4 There are dual combinations of verb moods, i.e. at least two types in the wording of the prompt |

S |

3.25 |

.75 |

X |

.4677 |

.9111 |

X |

insufficiency |

| R |

3.25 |

.75 |

X |

.4677 |

.9111 |

X |

Irrelevant |

| C |

3.00 |

.67 |

X |

.3906 |

.8619 |

X |

Rewrite |

| D5 The prompt uses three types of combined verb moods |

S |

3.25 |

.75 |

X |

.4677 |

.9111 |

X |

Insufficiency |

| R |

3.25 |

.75 |

X |

.4677 |

.9111 |

X |

Irrelevant |

| C |

3.00 |

.67 |

X |

.3906 |

.8619 |

X |

Rewrite |

| E1 There is a simple sentence in the wording of the prompt. |

S |

3.75 |

.92 |

✓ |

.6461 |

1.0000 |

X |

Revise sufficiency |

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

3.25 |

.75 |

X |

.4677 |

.9111 |

X |

Rewrite |

| E2 There is a coordinated sentence in the wording of the prompt. |

S |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

3.25 |

.75 |

X |

.4677 |

.9111 |

X |

Rewrite |

| E3 There is a subordinate sentence in the wording of the prompt. |

S |

3.50 |

.83 |

✓ |

.552 |

.953 |

X |

Revise sufficiency |

| R |

3.50 |

.83 |

✓ |

.552 |

.953 |

X |

Revise relevance |

| C |

3.25 |

.75 |

X |

.4677 |

.9111 |

X |

Rewrite |

| E4 There are dual combinations of sentence types |

S |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| R |

4.00 |

1.00 |

✓ |

.7575 |

1.0000 |

✓ |

|

| C |

3.75 |

.92 |

✓ |

.6461 |

.9851 |

X |

Revise writing |

| E5 Three types of combined sentences are used in the prompt |

S |

3.50 |

.83 |

✓ |

.552 |

.953 |

X |

Revise sufficiency |

| R |

3.50 |

.83 |

✓ |

.552 |

.953 |

X |

Revise relevance |

| C |

3.00 |

.67 |

X |

.3906 |

.8619 |

X |

Rewrite |

References

- Aiken, L. (1985). Three coefficients for analyzing the reliability and validity of ratings. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 45(1), 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. V., Paz, Y. B., & Brown, E. K. (2021). El léxico-gramática del español: Una aproximación mediante la lingüística de corpus. Routledge.

- Bryant, C., Yuan, Z., Qorib, M. R., Cao, H., Ng, H. T., & Briscoe, T. (2023). Grammatical Error Correction: A Survey of the State of the Art. Computational Linguistics, 1–59. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. K. Y., & Hu, W. (2023). Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 43. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Zhang, Z., Langrené, N., & Zhu, S. (2024). Unleashing the potential of prompt engineering in Large Language Models: A comprehensive review (No. arXiv:2310.14735). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2310.14735.

- Chen, M., Tworek, J., Jun, H., Yuan, Q., Pinto, H. P. de O., Kaplan, J., Edwards, H., Burda, Y., Joseph, N., Brockman, G., Ray, A., Puri, R., Krueger, G., Petrov, M., Khlaaf, H., Sastry, G., Mishkin, P., Chan, B., Gray, S., … Zaremba, W. (2021). Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code (No. arXiv:2107.03374). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2107.03374.

- Deng, M., Wang, J., Hsieh, C.-P., Wang, Y., Guo, H., Shu, T., Song, M., Xing, E. P., & Hu, Z. (2022). RLPrompt: Optimizing Discrete Text Prompts with Reinforcement Learning (No. arXiv:2205.12548). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2205.12548.

- Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Fang, T., Yang, S., Lan, K., Wong, D. F., Hu, J., Chao, L. S., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Is ChatGPT a Highly Fluent Grammatical Error Correction System? A Comprehensive Evaluation (No. arXiv:2304.01746). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2304.01746.

- Gjenero, A. (2024). Uso del modo subjuntivo para expresar deseos. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Zagreb. Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Department of Romance Languages and Literature.

- Hendrycks, D., Burns, C., Basart, S., Zou, A., Mazeika, M., Song, D., & Steinhardt, J. (2021). Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding (No. arXiv:2009.03300). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2009.03300.

- Hendrycks, D., Burns, C., Kadavath, S., Arora, A., Basart, S., Tang, E., Song, D., & Steinhardt, J. (2021). Measuring Mathematical Problem Solving With the MATH Dataset (No. arXiv:2103.03874). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.03874.

- Heston, T., & Khun, C. (2023). Prompt Engineering in Medical Education. International Medical Education, 2(3), 198–205. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W. (2023). The unintended consequences of artificial intelligence and education. Education International.

- Johnson, D. Johnson, D., Goodman, R., Patrinely, J., Stone, C., Zimmerman, E., Donald, R., Chang, S., Berkowitz, S., Finn, A., Jahangir, E., Scoville, E., Reese, T., Friedman, D., Bastarache, J., Heijden, Y. V. D., Wright, J., Carter, N., Alexander, M., Choe, J., … Wheless, L. (2023). Assessing the Accuracy and Reliability of AI-Generated Medical Responses: An Evaluation of the Chat-GPT Model. In Review. [CrossRef]

- Knoth, N., Tolzin, A., Janson, A., & Leimeister, J. M. (2024). AI literacy and its implications for prompt engineering strategies. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100225. [CrossRef]

- Meskó, B. (2023). Prompt Engineering as an Important Emerging Skill for Medical Professionals: Tutorial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e50638. [CrossRef]

- Miao, F., Holmes, W., Huang, R., & Zhang, H. (2021). AI and education: A guidance for policymakers. Unesco Publishing.

- Muñoz De La Virgen, C. (2024). Adquisición del modo subjuntivo: Una propuesta didáctica. Didáctica. Lengua y Literatura, 36, 127–144. [CrossRef]

- Overono, A. L., & Ditta, A. S. (2023). The Rise of Artificial Intelligence: A Clarion Call for Higher Education to Redefine Learning and Reimagine Assessment. College Teaching, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Pavelko, S. L., Price, L. R., & Owens Jr, R. E. (2020). Revisiting reliability: Using Sampling Utterances and Grammatical Analysis Revised (SUGAR) to compare 25-and 50-utterance language samples. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(3), 778–794. [CrossRef]

- Pavez, M. (2002). Presentación del índice de desarrollo del lenguaje ‘Promedio de Longitud de los Enunciados’ (PLE). Universidad de Chile. https://bit.ly/2IH4rwV.

- Penfield, R. D., & Giacobbi, Jr., P. R. (2004). Applying a Score Confidence Interval to Aiken’s Item Content-Relevance Index. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 8(4), 213–225. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A. (2023). Analysing English sentence structure: An intermediate course in syntax. Cambridge University Press.

- Roumeliotis, K. I., & Tselikas, N. D. (2023). ChatGPT and Open-AI Models: A Preliminary Review. Future Internet, 15(6), 192. [CrossRef]

- Saúde, S., Barros, J. P., & Almeida, I. (2024). Impacts of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: Research Trends and Students’ Perceptions. Social Sciences, 13(8), 410. [CrossRef]

- Schulhoff, S., Ilie, M., Balepur, N., Kahadze, K., Liu, A., Si, C., Li, Y., Gupta, A., Han, H., Schulhoff, S., Dulepet, P. S., Vidyadhara, S., Ki, D., Agrawal, S., Pham, C., Kroiz, G., Li, F., Tao, H., Srivastava, A., … Resnik, P. (2024). The Prompt Report: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Techniques (No. arXiv:2406.06608). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2406.06608.

- Shi, F., Suzgun, M., Freitag, M., Wang, X., Srivats, S., Vosoughi, S., Chung, H. W., Tay, Y., Ruder, S., Zhou, D., Das, D., & Wei, J. (2022). Language Models are Multilingual Chain-of-Thought Reasoners (No. arXiv:2210.03057). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2210.03057.

- Singh, A., Singh, N., & Vatsal, S. (2024). Robustness of LLMs to Perturbations in Text (No. arXiv:2407.08989). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2407.08989.

- Soler, M. C., Murillo, E., Nieva, S., Rodríguez, J., Mendez-Cabezas, C., & Rujas, I. (2023). Verbal and More: Multimodality in Adults’ and Toddlers’ Spontaneous Repetitions. Language Learning and Development, 19(1), 16–33. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A., Rastogi, A., Rao, A., Shoeb, A. A. M., Abid, A., Fisch, A., Brown, A. R., Santoro, A., Gupta, A., Garriga-Alonso, A., Kluska, A., Lewkowycz, A., Agarwal, A., Power, A., Ray, A., Warstadt, A., Kocurek, A. W., Safaya, A., Tazarv, A., … Wu, Z. (2023). Beyond the Imitation Game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models (No. arXiv:2206.04615). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04615.

- Team, G., Anil, R., Borgeaud, S., Alayrac, J.-B., Yu, J., Soricut, R., Schalkwyk, J., Dai, A. M., Hauth, A., Millican, K., Silver, D., Johnson, M., Antonoglou, I., Schrittwieser, J., Glaese, A., Chen, J., Pitler, E., Lillicrap, T., Lazaridou, A., … Vinyals, O. (2024). Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models (No. arXiv:2312.11805). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2312.11805.

- Torrego, L. G. (2015). Ortografía de uso español actual. Ediciones SM España.

- Vyčítalová, B. L. (2024). El subjuntivo y el indicativo: La importancia de una preparación previa del estudiante. Filozofická Fakulta Ústav Románských Jazyků a Literatur. Masarykova Univerzita.

- Wermelinger, M. (2023). Using GitHub Copilot to Solve Simple Programming Problems. Proceedings of the 54th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1, 172–178. [CrossRef]

- White, J., Hays, S., Fu, Q., Spencer-Smith, J., & Schmidt, D. C. (2024). ChatGPT Prompt Patterns for Improving Code Quality, Refactoring, Requirements Elicitation, and Software Design (No. arXiv:2303.07839). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2303.07839.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).