In this section we present numerical experiments to evaluate our approach.

4.2. Experiment Group A

In this group the kill probability function has the form:

Let us look at the final results of a representative run of the learning algorithm. With

,

,

,

and

, we run the learning algorithm with

,

and for three different values

. In

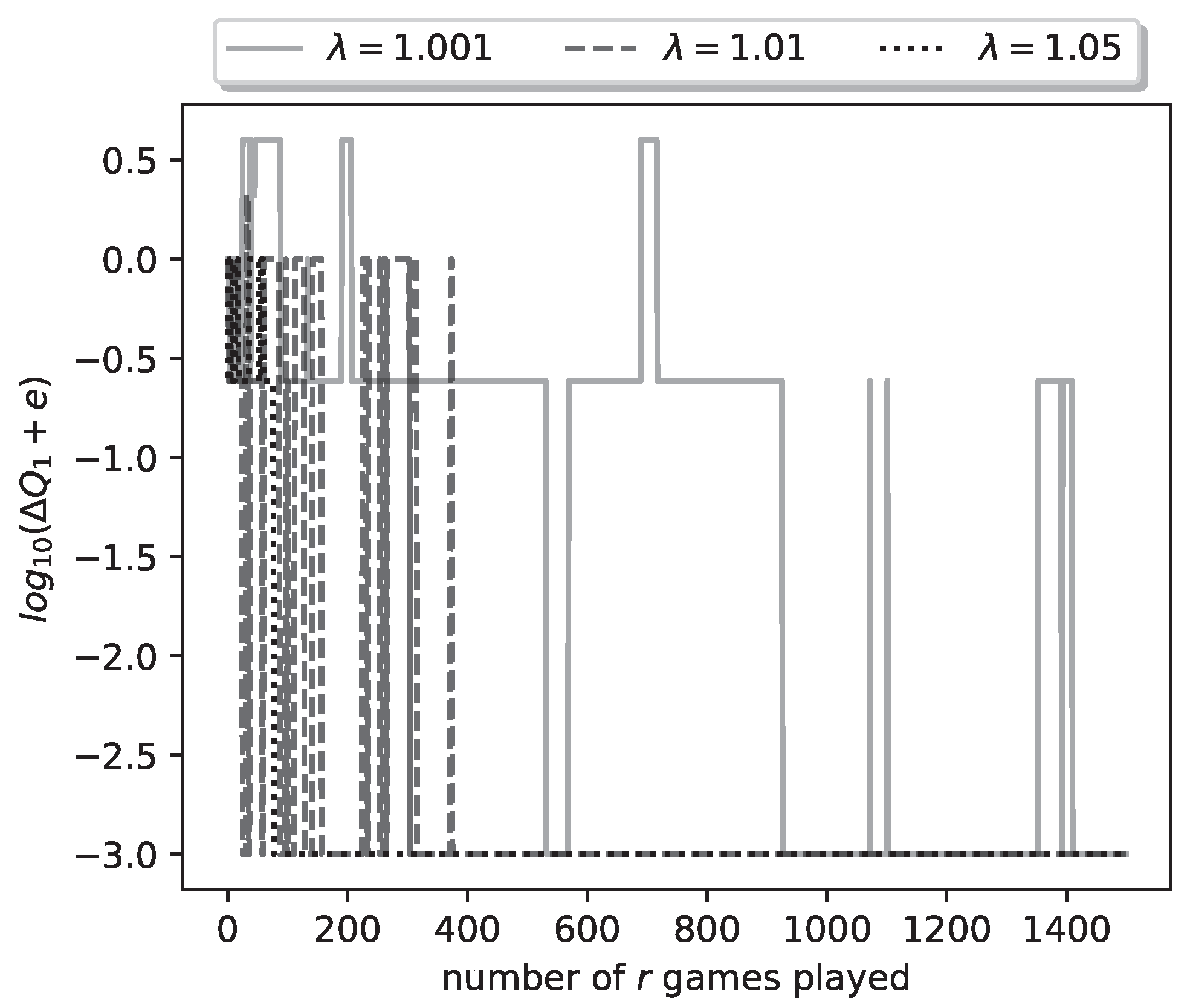

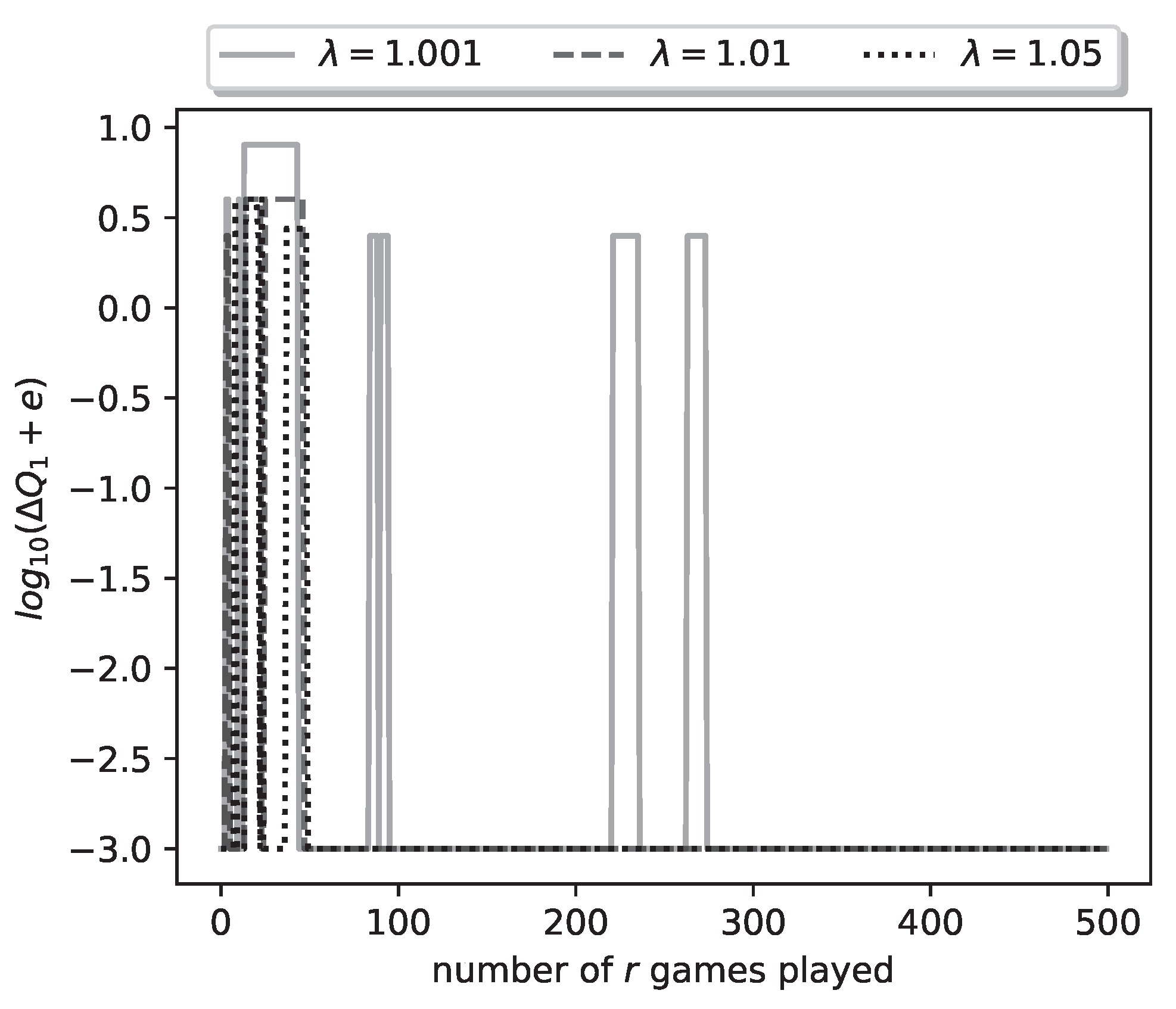

Figure 4 we plot the logarithm (with base 10) of the relative payoff error

(we have added

to deal with the logarithm of zero error). The three curves plotted correspond to the

values 1.001, 1.01, 1.05. We see that, for all

values, the algorithm achieves zero relative error; in other words it learns the optimal strategy for both players. Furthermore convergence is achieved by the 1500-th iteration of the algorithm (1500-th duel played), as seen by the achieved logarithm value

(recall that we have added

to the error, hence the true error is zero). Convergence is fastest for the largest

value, i.e.,

, and slowest for the smallest value

.

Figure 4.

Plot of logarithmic relative error of ’s payoff for a representative run of the learning process.

Figure 4.

Plot of logarithmic relative error of ’s payoff for a representative run of the learning process.

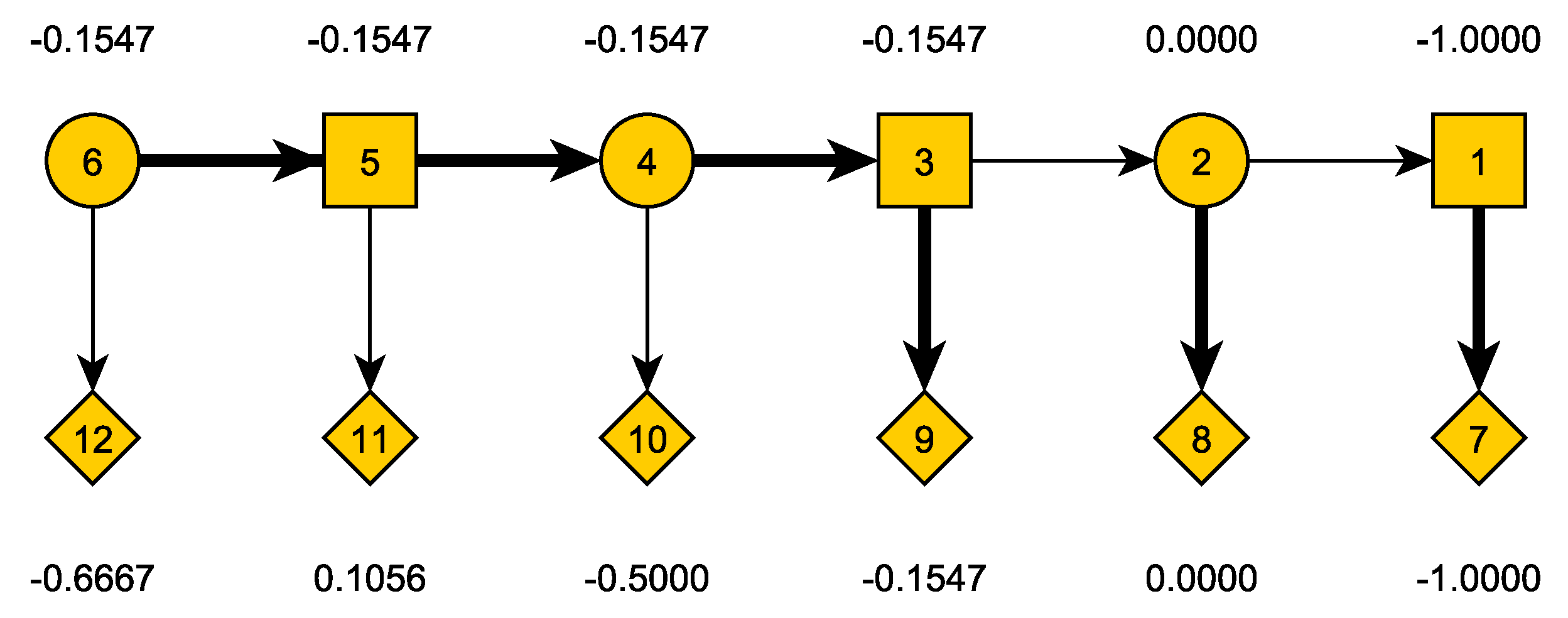

In

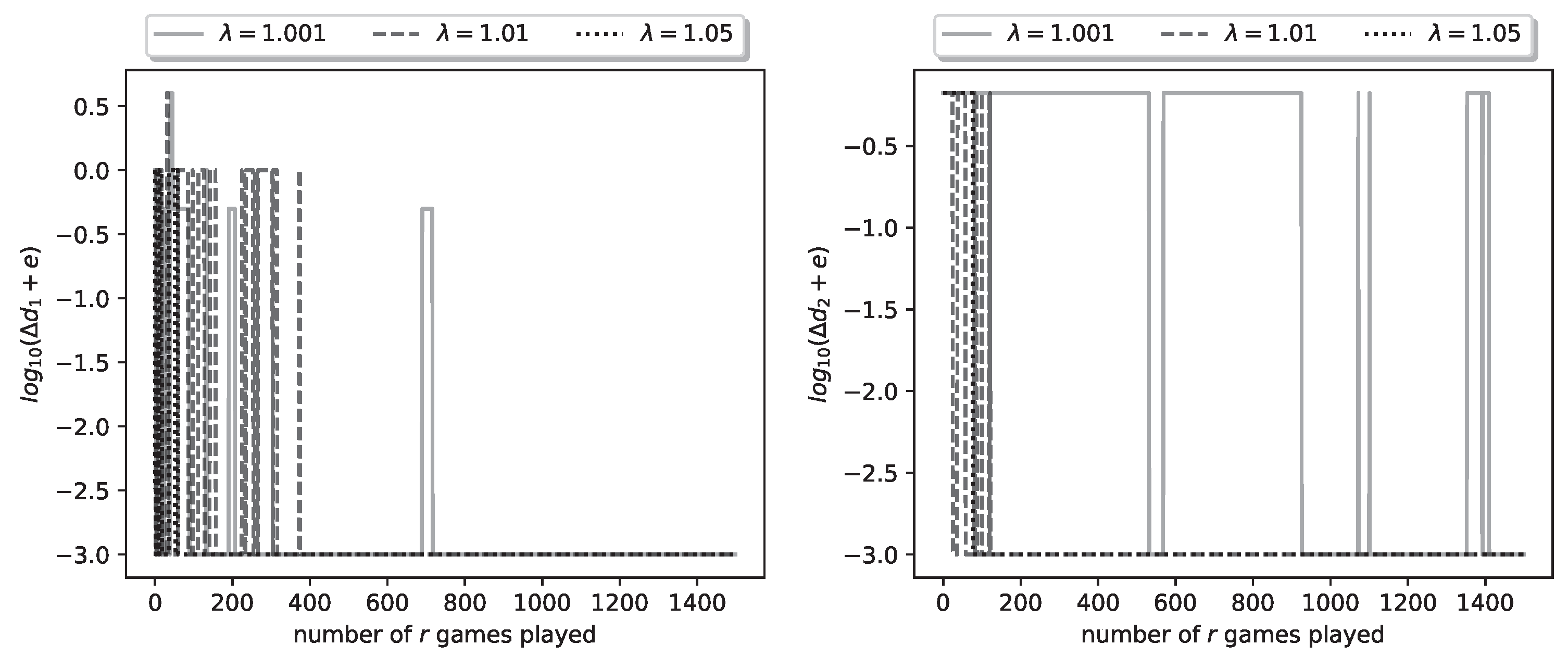

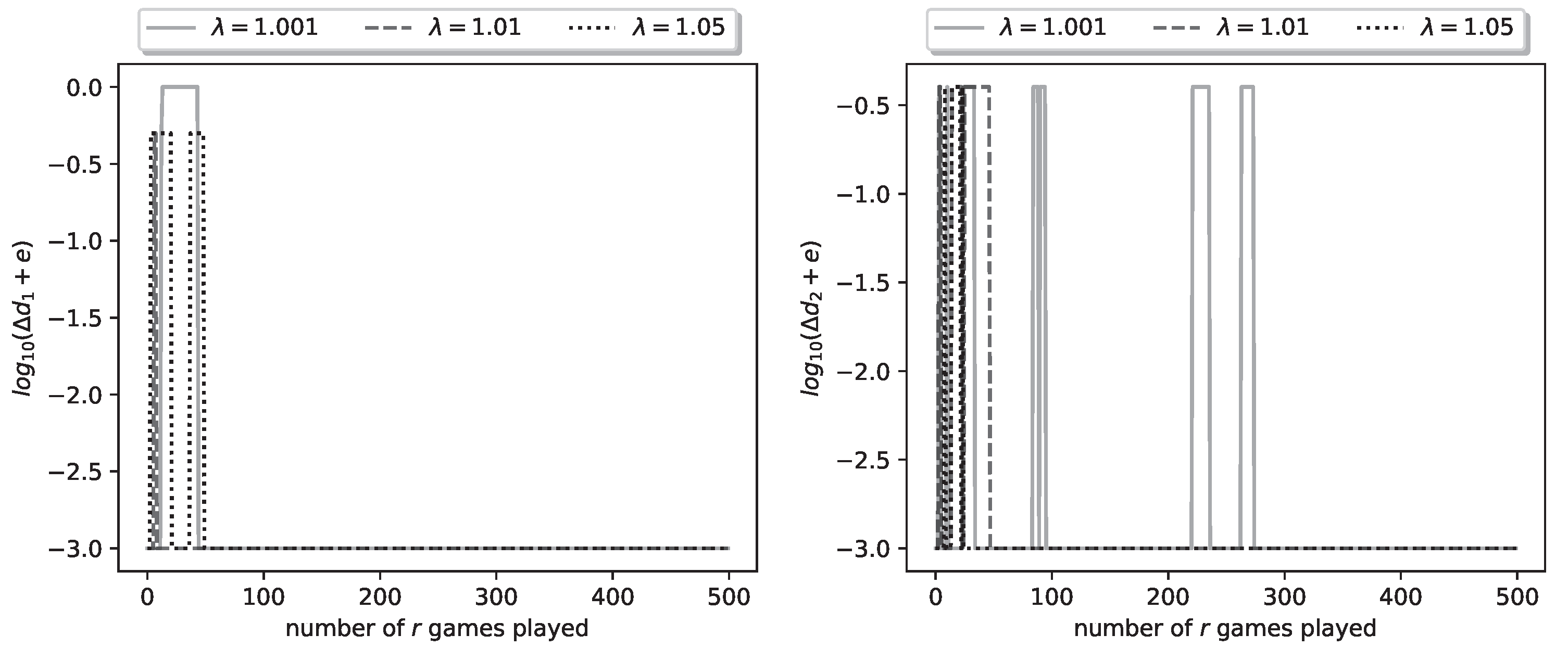

Figure 5 we plot the logarithmic relative errors

. These also, as expected, have converged to zero by the 1500-th iteration.

Figure 5.

Plot of logarithmic relative errors , for a representative run of the learning process.

Figure 5.

Plot of logarithmic relative errors , for a representative run of the learning process.

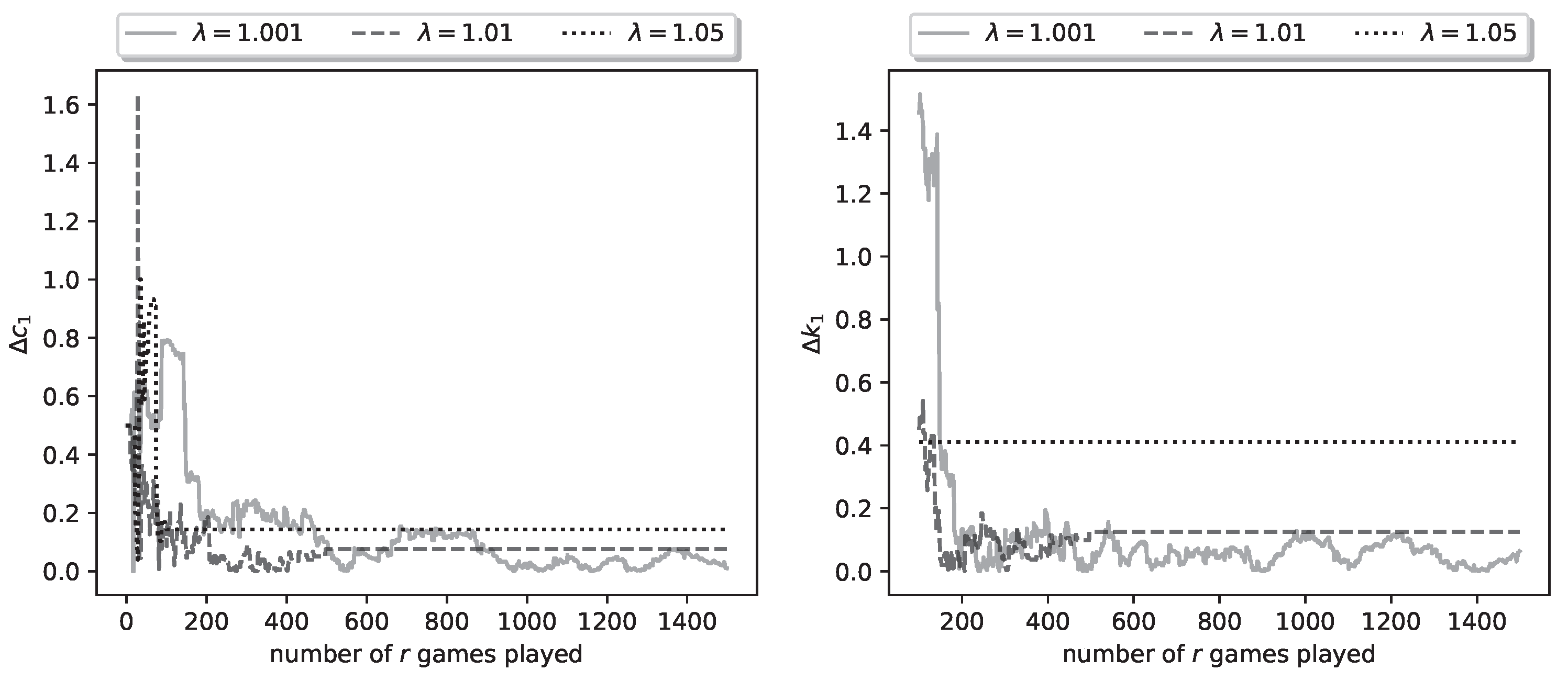

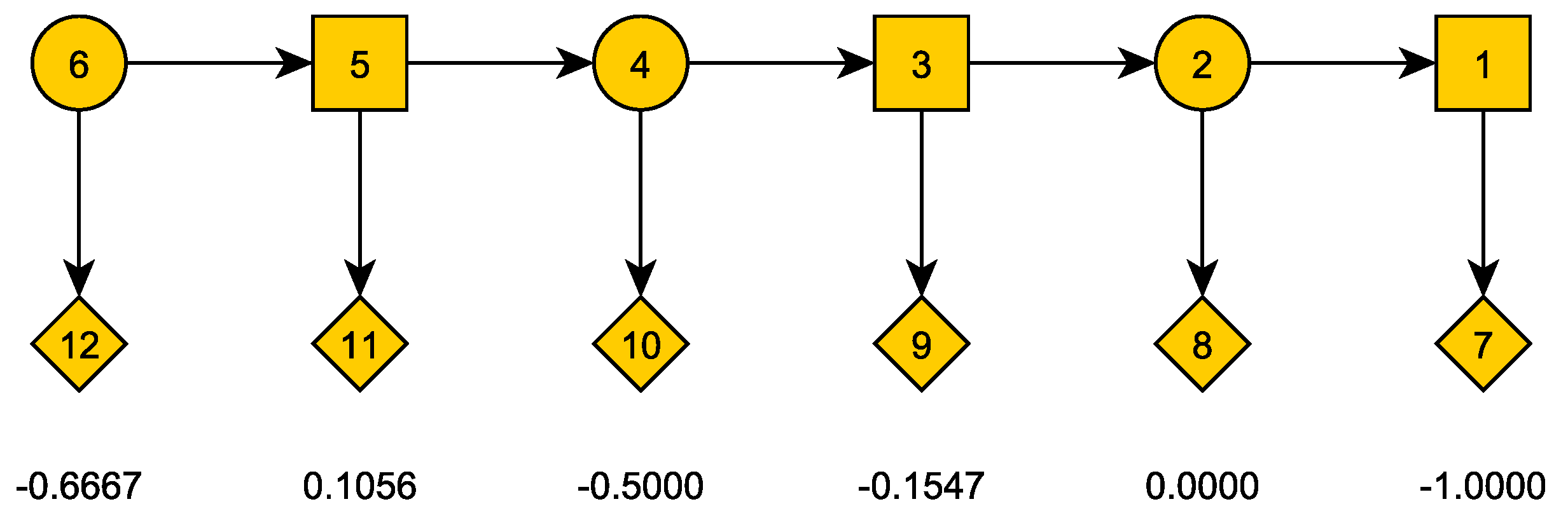

The fact that the estimates of the optimal shooting thresholds and strategies achieve zero error, does not imply that the same is true of the kill probability parameter estimates. In

Figure 6 we plot the relative errors

,

.

Figure 6.

Plot of relative parameter errors , for a representative run of the learning process.

Figure 6.

Plot of relative parameter errors , for a representative run of the learning process.

It can be seen that these errors do not converge to zero; in fact, for the errors converge to fixed nonzero values, which indicates that the algorithm obtains wrong estimates. However, the error is sufficiently small to still result in zero-error estimates of the shooting thresholds. The picture is similar for the errors , , hence their plots are omitted.

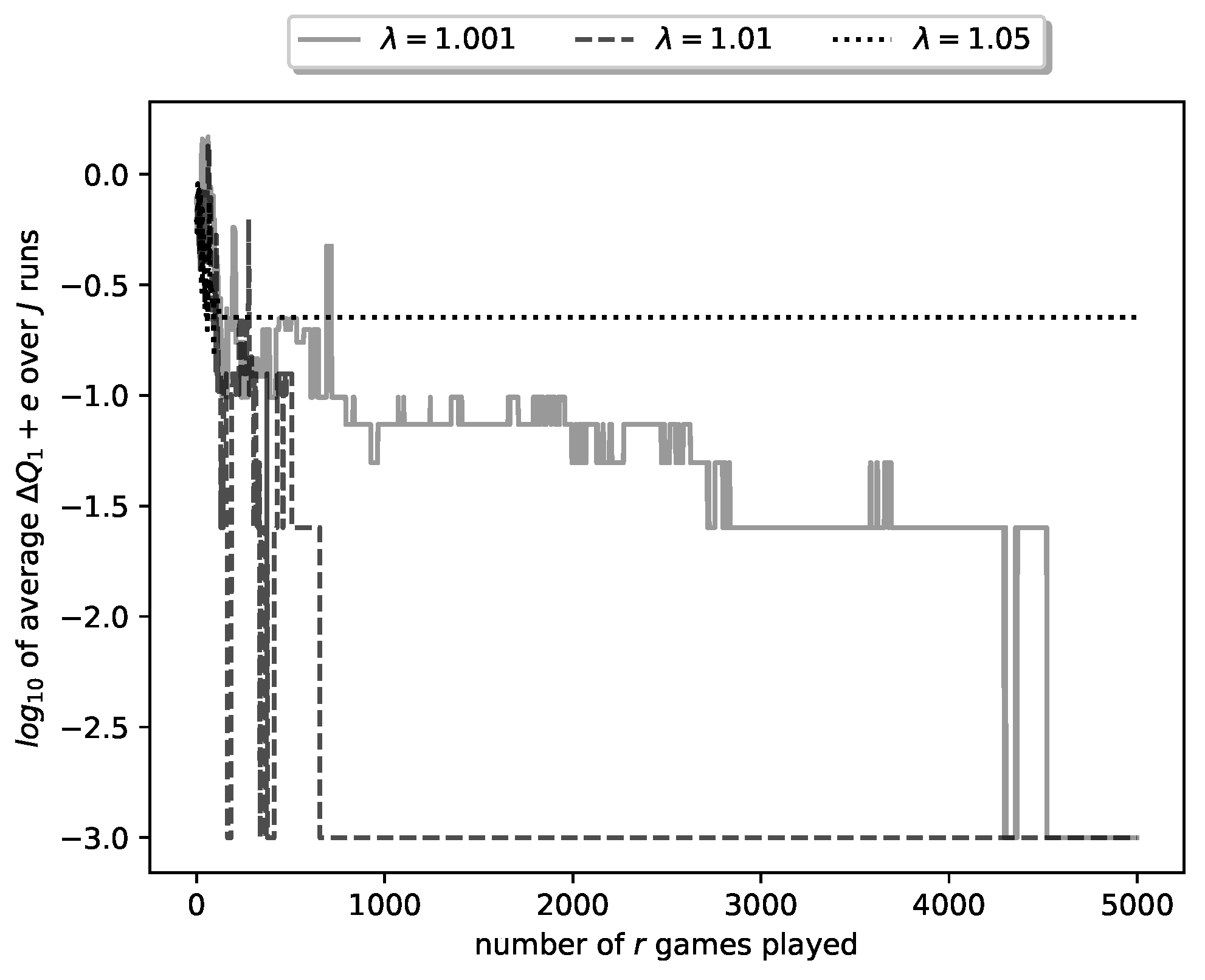

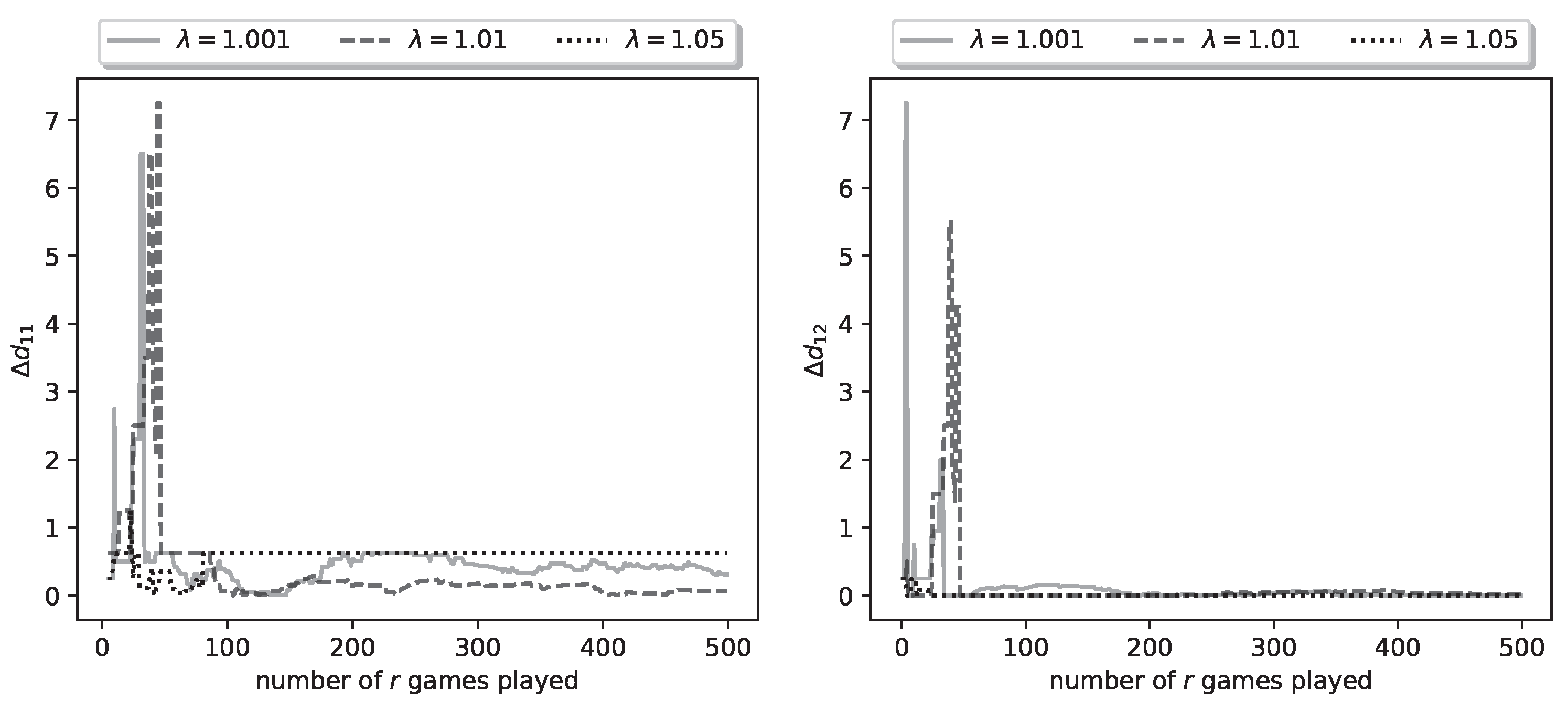

In the above we have given results for a particular run of the learning algorithm. This was a successful run, in the sense that it obtained zero-error estimates of the optimal strategies (and shooting thresholds). However, since our algorithm is stochastic, it is not guaranteed that every run will result in zero-error estimates. To better evaluate the algorithm, we have run it for

times and averaged the obtained results. In particular, in

Figure 7 we plot the average of ten curves of the type plotted in

Figure 4. Note that now we plot the curve for

plays of the duel.

Figure 7.

Plot of (’s payoff) for a representative run of the learning process.

Figure 7.

Plot of (’s payoff) for a representative run of the learning process.

Several observations can be made regarding

Figure 7.

For the smallest value, namely , the respective curve reaches at . This corresponds to zero average error, which means that, in some algorithm runs, it took more than 4500 iterations (duel plays) to reach zero error.

For the , all runs of the algorithm reached zero-error after runs.

Finally, for , the average error never reached zero; in fact 3 out of 10 runs converged to nonzero-error estimates, i.e., to non-optimal strategies.

The above observations corroborate a fact well known in the study of reinforcement learning [

7]. Namely, a small learning rate (in our case small

) results in higher probability of converging to the true parameter values, but also in slower convergence. This can be explained as follows: a small

results in higher

values for a large proportion of duels played by the algorithm; i.e., in more extensive

exploration, which however results in slower

exploitation (convergence).

3

We conclude this group of experiments by running the learning algorithm for various combinations of game parameters; for each combination we record the average error attained at the end of the algorithm (i.e., at ). The results are summarized at the following tables.

Table 3.

Values of final average relative error for , and various values of , , . D is fixed at .

Table 3.

Values of final average relative error for , and various values of , , . D is fixed at .

|

|

|

1.001 |

|

|

1.01 |

|

|

1.05 |

|

|

|

0.50 |

1.00 |

1.50 |

0.50 |

1.00 |

1.50 |

0.50 |

1.00 |

1.50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1.00 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.100 |

0.482 |

0.224 |

0.500 |

1.207 |

| 1.50 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.059 |

0.049 |

1.748 |

0.215 |

0.480 |

3.777 |

| 2.00 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.048 |

0.074 |

0.199 |

0.097 |

0.144 |

0.980 |

0.072 |

Table 4.

Round at which converged to zero for all sessions for , and various values of , , . D is fixed at . If did not converge for all sessions we note for how many sessions it converged.

Table 4.

Round at which converged to zero for all sessions for , and various values of , , . D is fixed at . If did not converge for all sessions we note for how many sessions it converged.

|

|

|

1.001 |

|

|

1.01 |

|

|

1.05 |

|

|

|

0.50 |

1.00 |

1.50 |

0.50 |

1.00 |

1.50 |

0.50 |

1.00 |

1.50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1.00 |

4521 |

1456 |

2983 |

656 |

9/10 |

8/10 |

7/10 |

5/10 |

5/10 |

| 1.50 |

3238 |

2939 |

1754 |

7/10 |

9/10 |

9/10 |

0/10 |

8/10 |

6/10 |

| 2.00 |

4153 |

423 |

8/10 |

2/10 |

9/10 |

6/10 |

3/10 |

4/10 |

6/10 |

From

Table 6 and

Table 7 we see that for

almost all learning sessions conclude in zero

, while increasing the value of

results in more sessions concluding with non-zero error estimates. Furthermore, we observe that when the average

converges to zero for multiple values of

the convergence is faster for bigger

. These results highlight the trade off between

exploration and

exploitation discussed above.

Finally, in

Table 8 we see how many learning sessions were run and how many converged to zero error estimate

for different values of

D and

.

Table 5.

Fraction of learning sessions that converged to for different values of D and .

Table 5.

Fraction of learning sessions that converged to for different values of D and .

|

|

1.001 |

1.01 |

1.05 |

| D |

|

|

|

| 8 |

163/170 |

144/170 |

89/170 |

| 10 |

165/170 |

139/170 |

81/170 |

| 12 |

161/170 |

123/170 |

68/170 |

| 14 |

164/170 |

134/170 |

73/170 |

| total |

653/680 |

540/680 |

311/680 |

Table 6.

Values of final average relative error for , and various values of , , . D is fixed at .

Table 6.

Values of final average relative error for , and various values of , , . D is fixed at .

| |

|

1.001 |

1.01 |

1.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

0.000 |

0.233 |

1.000 |

| 1 |

|

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.799 |

| 1 |

D |

|

|

0.800 |

|

|

0.000 |

0.000 |

2.799 |

|

D |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.777 |

|

D |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.480 |

Table 7.

Round at which converged to zero for all sessions for , and various values of , , . D is fixed at . If did not converge for all sessions we note for how many sessions it converged.

Table 7.

Round at which converged to zero for all sessions for , and various values of , , . D is fixed at . If did not converge for all sessions we note for how many sessions it converged.

| |

|

1.001 |

1.01 |

1.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

287 |

7/10 |

0/10 |

| 1 |

|

812 |

333 |

9/10 |

| 1 |

D |

7/10 |

9/10 |

9/10 |

|

|

326 |

139 |

5/10 |

|

D |

225 |

397 |

5/10 |

|

D |

711 |

464 |

6/10 |

Table 8.

Fraction of learning sessions that converged to for different values of D and .

Table 8.

Fraction of learning sessions that converged to for different values of D and .

|

|

1.001 |

1.01 |

1.05 |

| D |

|

|

|

| 8 |

76/110 |

80/110 |

49/110 |

| 10 |

97/110 |

95/110 |

56/110 |

| 12 |

94/110 |

78/110 |

39/110 |

| 14 |

100/110 |

84/110 |

40/110 |

| total |

367/440 |

337/440 |

184/440 |

4.3. Experiment Group B

In this group the kill probability function is piecewise linear

Let us look again at the final results of a representative run of the learning algorithm. With

,

,

,

and

, we run the learning algorithm with

,

and for the values

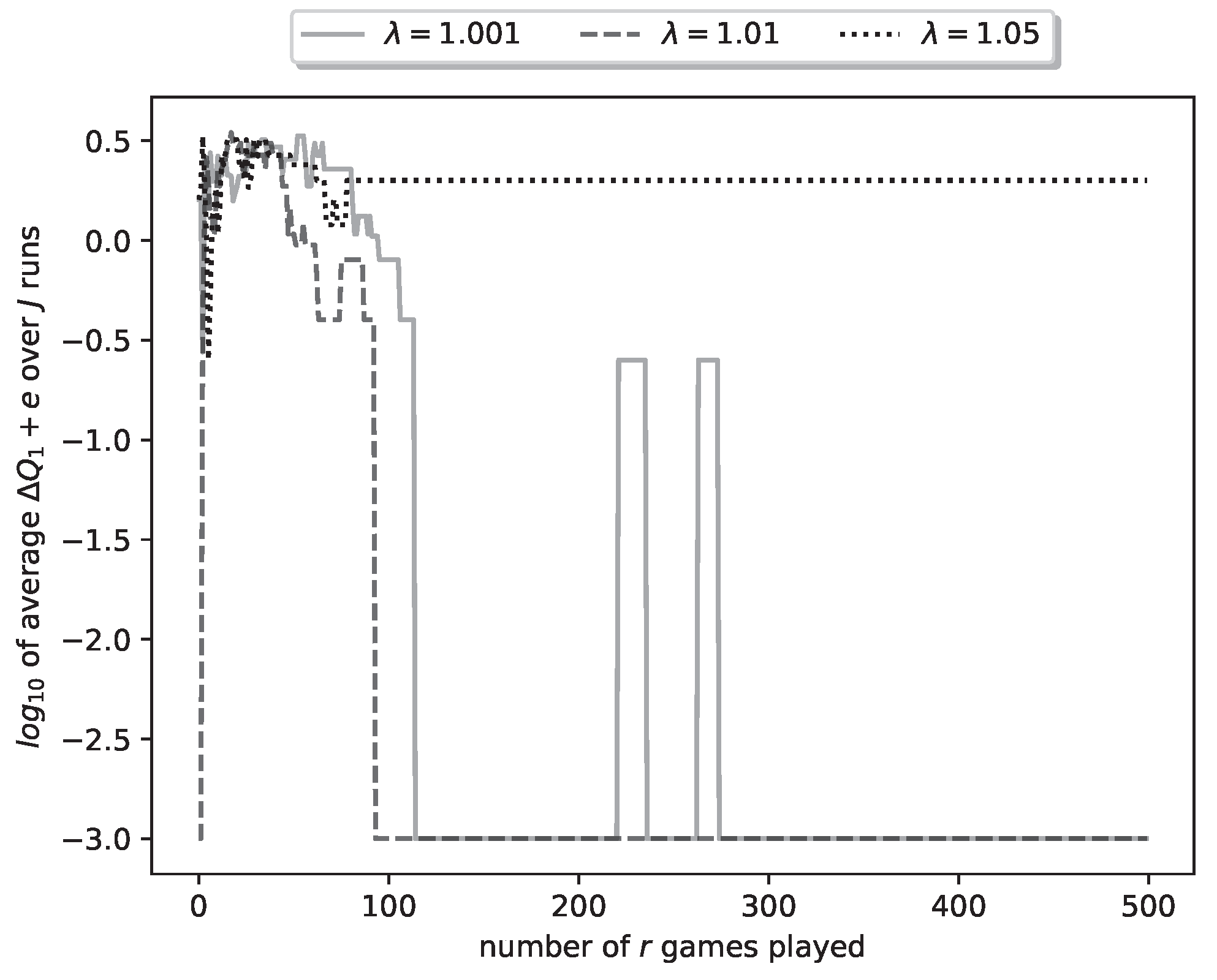

. In

Figure 8 we plot the logarithm (with base 10) of the relative payoff error

. We see similar results as in Group A, for all

values, the algorithm achieves zero relative error. Convergence is achieved by the 300-th iteration of the algorithm and it is fastest for

, and slowest for

.

Figure 8.

Plot of logarithmic relative error of ’s payoff for a representative run of the learning process.

Figure 8.

Plot of logarithmic relative error of ’s payoff for a representative run of the learning process.

In

Figure 9 we plot the logarithmic relative errors

. These also, as expected, have converged to zero by the 300-th iteration.

Figure 9.

Plot of logarithmic relative errors , for a representative run of the learning process.

Figure 9.

Plot of logarithmic relative errors , for a representative run of the learning process.

As in Group A, the fact that the estimates of the optimal shooting thresholds and strategies achieve zero error does not imply that the same is true for the kill probability parameter estimates. In

Figure 10, we plot the relative errors

and

. The relative error

converges to zero quickly, but the relative error

does not converge to zero for

. For

the error converges to a fixed nonzero value, which indicates that the algorithm obtains wrong estimates. However, the error is sufficiently small to still result in zero-error estimates of the shooting thresholds.

Figure 10.

Plot of relative parameter errors , for a representative run of the learning process.

Figure 10.

Plot of relative parameter errors , for a representative run of the learning process.

As in group A, to better evaluate the algorithm, we have run it for

times and averaged the obtained results. In particular, in

Figure 11 we plot the average of ten curves of the type plotted in

Figure 4. Note that now we plot the curve for

plays of the duel.

Figure 11.

Plot of (’s payoff) for a representative run of the learning process.

Figure 11.

Plot of (’s payoff) for a representative run of the learning process.

We again run the learning algorithm for various combinations of game parameters and record the average error attained at the end of the algorithm (again at ) for each combination. The results are summarized at the following tables.

From

Table 6 and

Table 7, we observe that for most parameter combinations, all learning sessions conclude with a zero

for the smaller

values. However, for

, the algorithm fails to converge and exhibits a high relative error. Notably, increasing

from 1.001 to 1.01 generally accelerates convergence, although this is not guaranteed in every case. In one instance, a higher

(specifically

) leads to a slower average convergence of

to zero, indicating the importance of initial random shooting choices. We also observe that results for the highest

are suboptimal, with the algorithm failing to converge in varying numbers of sessions, such as in 1 out of 10 or even 5 out of 10 cases. Notably, when convergence does occur, it happens relatively quickly, with sessions typically completing in under 1000 iterations. These findings also highlight the trade-off between

exploration and

exploitation, as discussed earlier.

Finally, in

Table 8 we see how many learning sessions were run and how many converged to zero error estimate

for different values of

D and

.