Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

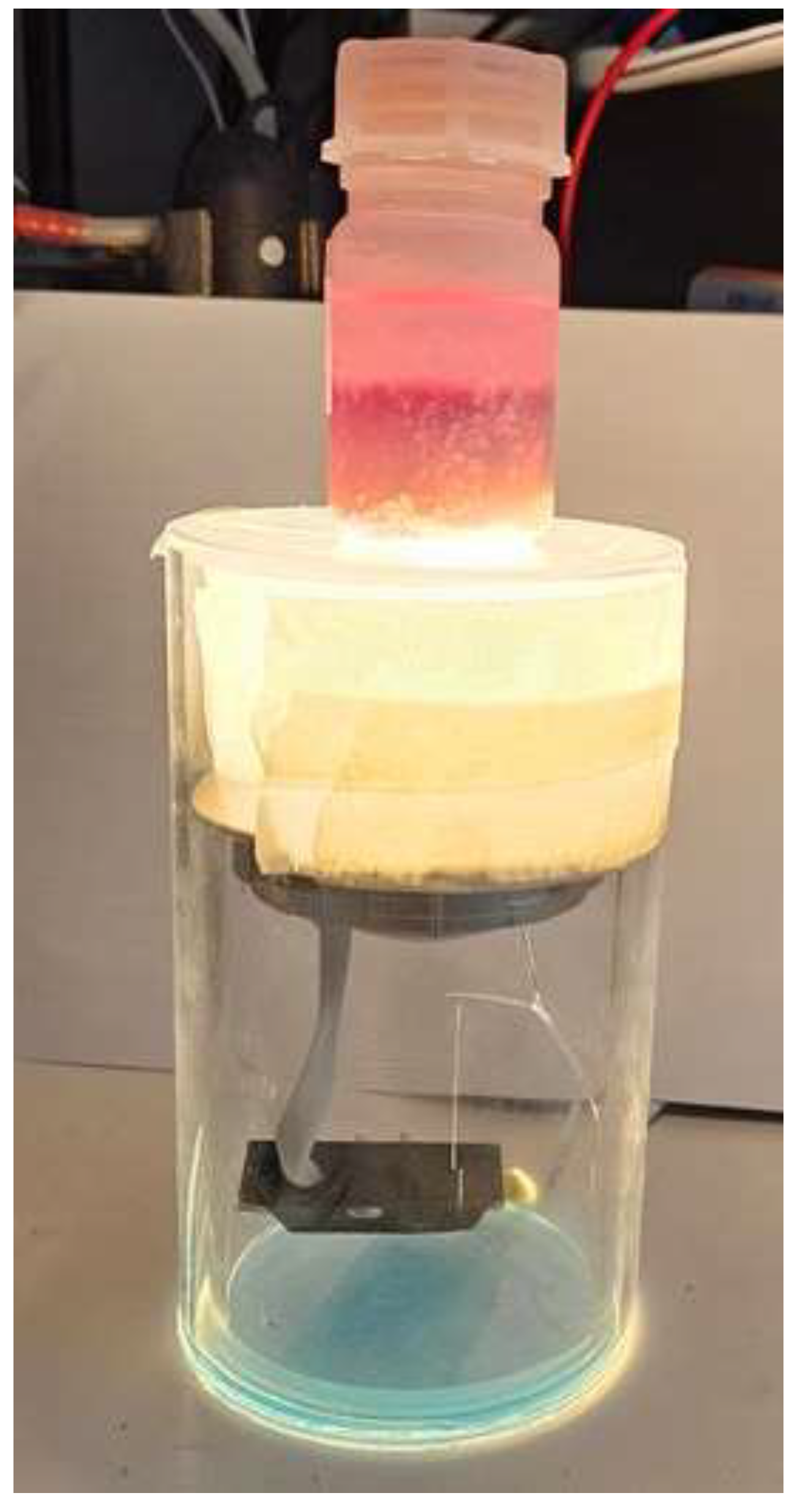

2.1. Photochemical Degradation of Selected Pollutants with Trivalent Europium (Eu(III)-Chloride) In A Two Phase System

2.2. Sample Preparation for GC Analysis by Toluene Extraction

2.3. Analysis of the Products of Photochemical Conversion of Various Selected Pollutants

| Parameter | Value |

| Injector temperature | 180 °C |

| Initial oven temperature | 80 °C |

| End oven temperature | 280 °C |

| Temperature ramp | 30 °C/min |

| Mobile phase | He |

| Flow rate | 1 ml/min |

| Split | 100/1 |

3. Results and Discussion

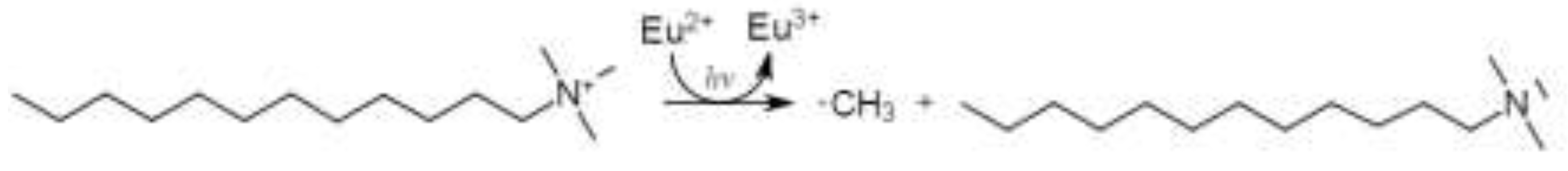

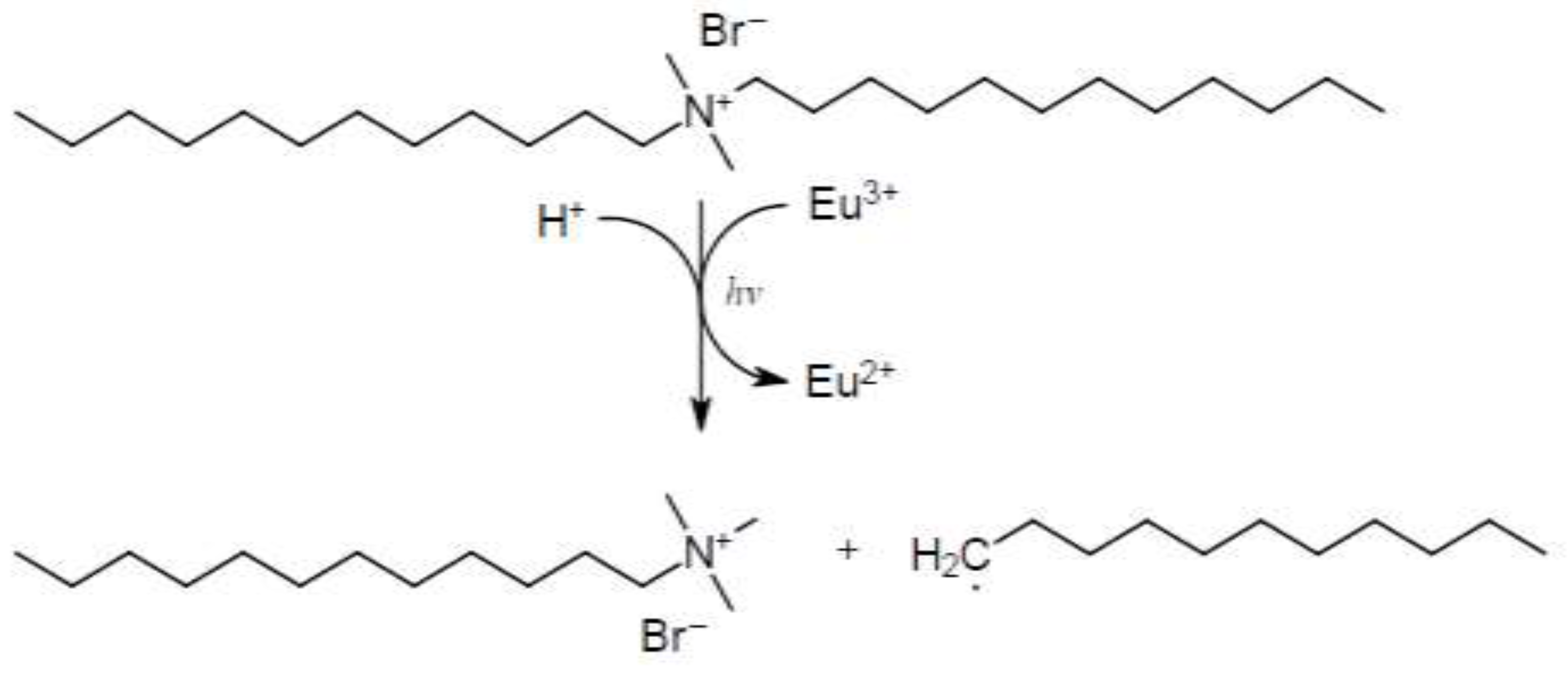

3.1. Results and Discussion of the Degradation Experiments Of Didodecyl Dimethyl Ammonium Bromide With Trivalent Europium

- As well as Docosyl acetate

3.2. Results and Discussion of the Degradation Experiments of Toluene With Trivalent Europium

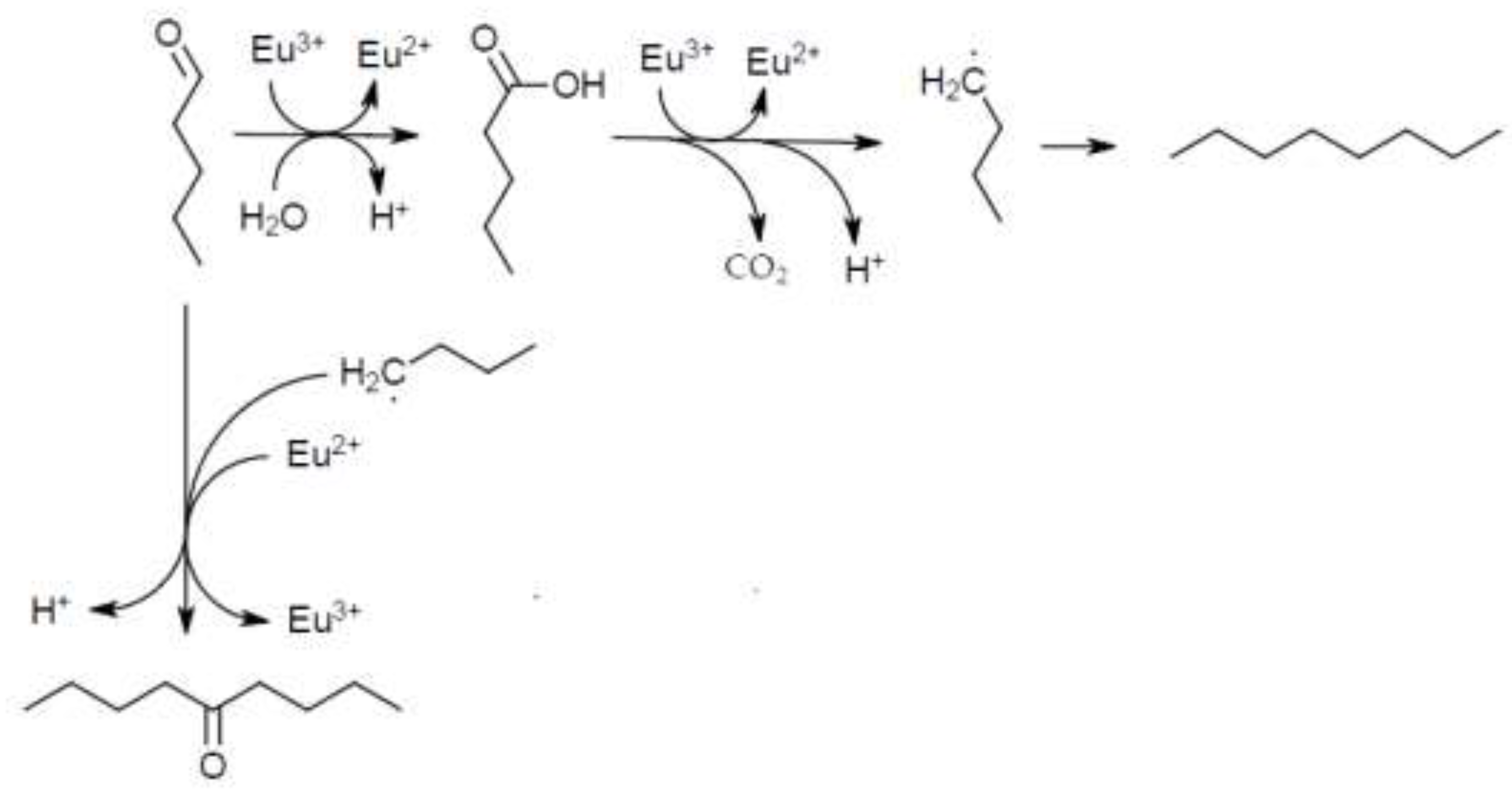

3.3. Results and Discussion of the Degradation Experiments of Pentanal with Trivalent Europium

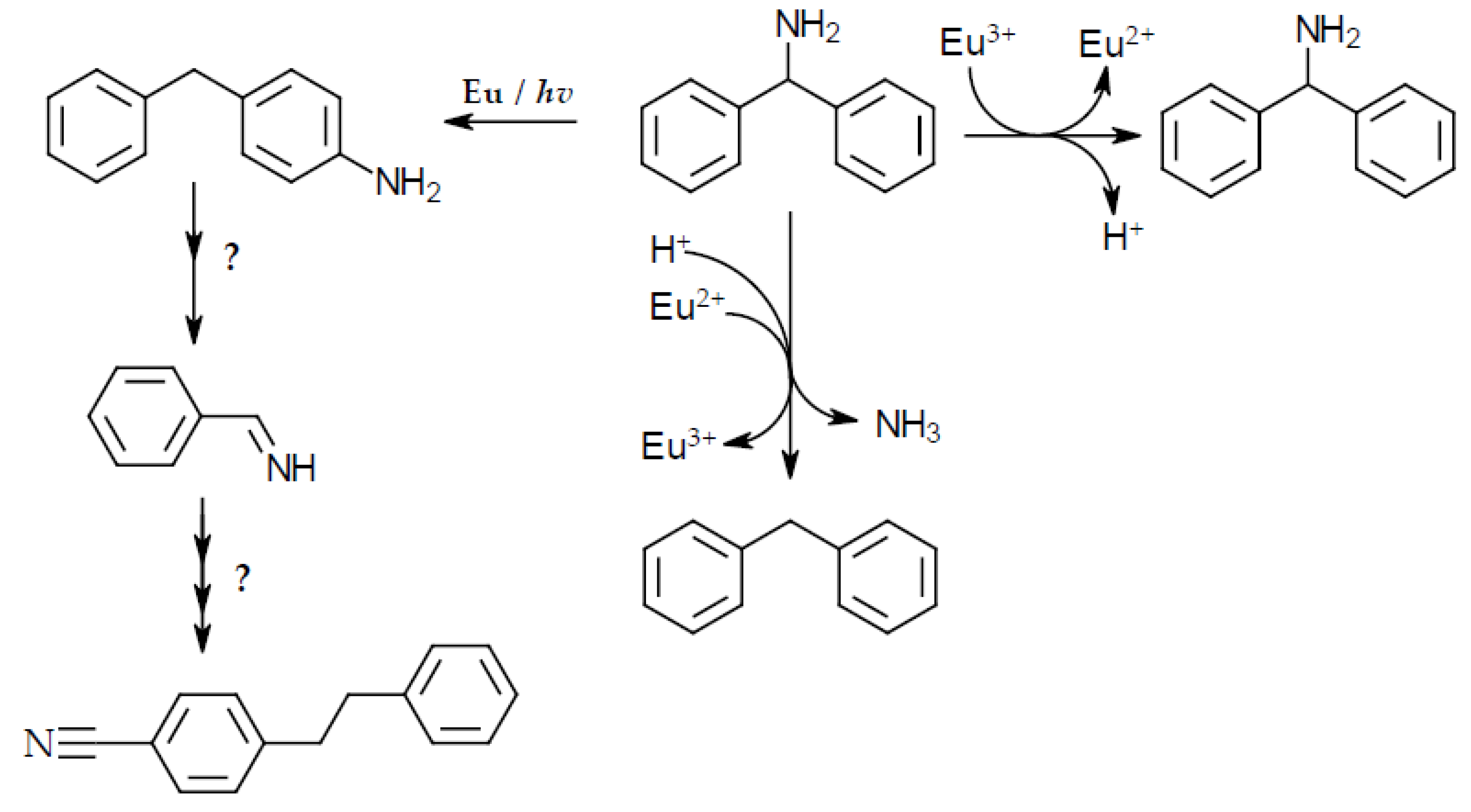

3.4. Results and Discussion Of The Degradation Experiments Of Benzhydryl Amine With Trivalent Europium

- Benzophenone imine

- 2-phenylethyl-4-benzonitrile

- Diphenylmethane

3.5. Results and discussion of the degradation experiments of N-1,2-diphenylethyl isopropyl carbamate with trivalent europium

- 1-dodecyl isocyanate

- 1-phenyl-2-propanol

- diethyl bis(hydroxymethyl) malonate

- ethylbenzene

- various pyroglutamates

3.6. Results and Discussion Of The Degradation Experiments Of Chlorobenzene With Trivalent Europium

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Remesal Rodríguez, J. Monte Testaccio (Rome, Italy). In Encyclopedia of global archaeology; Springer: Cham, 2018; pp. 1–14. ISBN ISBN 978-3-319-51726-1. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, J.T. Roman pottery in the archaeological record; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, New York, 2007; ISBN 0511285787. [Google Scholar]

- Ricerche sul Patrimonio Urbano tra Testaccio e Ostiense; CROMA Univ. Roma Tre: Roma, 2014, ISBN 9788883681301.

- Havlíček, F.; Pokorná, A.; Zálešák, J. Waste Management and Attitudes Towards Cleanliness in Medieval Central Europe. Journal of Landscape Ecology 2017, 10, 266–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Březinová, H.; Selmi Wallisová, M. Odpadní vrstvy a objekty jako pramen poznání stratifikace středověké společnosti – výpověď mocného smetištního souvrství z Nového Města pražského. Archaeologia historica 2016, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreck, P. Environmental impact of uncontrolled waste disposal in mining and industrial areas in Central Germany. Environmental Geology 1998, 35, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, H.; Teutsch, G.; Fritz, P.; Daus, B.; Dahmke, A.; Grathwohl, P.; Trabitzsch, R.; Feist, B.; Ruske, R.; Böhme, O.; et al. Sanierungsforschung in regional kontaminierten Aquiferen (SAFIRA) - 1. Information zum Forschungsschwerpunkt am Standort Bitterfeld. Grundwasser 2001, 6, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.; Alfreider, A.; Lorbeer, H.; Hoffmann, D.; Wuensche, L.; Babel, W. Bioremediation of chlorobenzene-contaminated ground water in an in situ reactor mediated by hydrogen peroxide. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 2004, 68, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.J.; van der Lee, E.M.; Eggert, A.; Stamer, B.; Gledhill, M.; Schlosser, C.; Achterberg, E.P. In Situ Measurements of Explosive Compound Dissolution Fluxes from Exposed Munition Material in the Baltic Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 5652–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, J.; Wecks, M.; Freier, U.; Häntzschel, D. Abbau von Chlorbenzol im Grundwasser durch heterogen-katalytische Oxidation in einer Pilotanlage. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2006, 78, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.L.; Jørgensen, C.K. Absorption Spectra of Octahedral Lanthanide Hexahalides. J. Phys. Chem. 1966, 70, 2845–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, O.; Horváth, O.; Stevenson, K.L. Charge transfer photochemistry of coordination compounds; VCH: New York, Weinheim, 1993; ISBN 0471188379. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.A.; Williams-Jones, A.E. The aqueous geochemistry of the rare-earth elements and yttrium 4. Monazite solubility and REE mobility in exhalative massive sulfide-depositing environments. Chemical Geology 1994, 115, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, P.; Wagener, K. Über die Sintergeschwindigkeit von Urandioxidpulver unter oxidierenden und reduzierenden Bedingungen und Folgerungen über die Spaltedelgasabgabe (Edelgasdiffusion in Festkörpern 16). In Über die Sintergeschwindigkeit von Urandioxidpulver unter oxidierenden und reduzierenden Bedingungen und Folgerungen über die Spaltedelgasabgabe (Edelgasdiffusion in Festkörpern 16); Möller, P., Wagener, K., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, s.l; pp. 113–117. 1965; ISBN 978-3-662-22911-8. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, Y.; Stein, G.; Tomkiewicz, M. Fluorescence and photochemistry of the charge-transfer band in aqueous europium(III) solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 1970, 74, 2558–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, Y.; Stein, G.; Tenne, R. The Photochemistry of Solutions of Eu(III) and Eu(II). Israel Journal of Chemistry 1972, 10, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, A.; Azuma, N. Photodecomposition of europium(III) acetate and formate in aqueous solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 1988, 92, 1830–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.D.; Stevenson, K.L.; King, G.K. Photolysis of europium(II) perchlorate in aqueous acidic solution. Inorg. Chem. 1977, 16, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blind, F. Orientierende Untersuchungen zur Platinmetall-freien Aktivierung von CH-Bindungen für Europium-basierte Brennstoffzellenanwendungen. Masterthesis; TU Dresden, Dresden, 06/18.

- Dai, W.-M.; Mak, W.L.; Wu, A. Eu(fod)3-catalyzed tandem regiospecific rearrangement of divinyl alkoxyacetates and Diels–Alder reaction. Tetrahedron Letters 2000, 41, 7101–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.-M.; Wu, A.; Lee, M.Y.H.; Lai, K.W. Neighboring nucleophilic group assisted rearrangement of allylic esters under Eu(fod)3 catalysis. Tetrahedron Letters 2001, 42, 4215–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.-M.; Mak, W.-L. Structural Effect on Eu(fod) 3 -Catalyzed Rearrangement of Allylic Esters. Chin. J. Chem. 2003, 21, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shull, B.K.; Sakai, T.; Koreeda, M. Eu(fod) 3 -Catalyzed Rearrangement of Allylic Methoxyacetates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11690–11691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulsfort, J. Biopolymere als Potenzielle Substrate der Photooxidation durch f-Block-Metalle. Master Thesis, ; TU Dresden, Zittau, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, A.W. Ueber die Einwirkung des Broms in alkalischer Lösung auf Amide. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1881, 14, 2725–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, A.W. von. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der flüchtigen organischen Basen. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1851, 78, 253–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laue, T.; Plagens, A. Namen- und Schlagwort-Reaktionen der organischen Chemie, 5., durchgesehene Auflage; Vieweg + Teubner: Wiesbaden, 2006; ISBN 3-8351-0091-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski, L.A.; Upadhyay, R.; Greeley, Z.W.; Margulies, B.J. Current Drugs to Treat Infections with Herpes Simplex Viruses-1 and -2. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeough, M.B.; Spruance, S.L. Comparison of new topical treatments for herpes labialis: efficacy of penciclovir cream, acyclovir cream, and n-docosanol cream against experimental cutaneous herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Arch. Dermatol. 2001, 137, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, S.L.; Thisted, R.A.; Jones, T.M.; Barbarash, R.A.; Mikolich, D.J.; Ruoff, G.E.; Jorizzo, J.L.; Gunnill, L.B.; Katz, D.H.; Khalil, M.H.; et al. Clinical efficacy of topical docosanol 10% cream for herpes simplex labialis: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001, 45, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patty's toxicology; Bingham, E. ; Cohrssen, B.; Patty, F.A., Eds., 6. ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, N.J, 2012; ISBN 9780470410813. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman, M.A.; Graham, D.G.; Priest, J.W.; Bouldin, T.W. The neurotoxicity of 5-nonanone: preliminary report. Toxicol. Lett. 1981, 8, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Donoghue, J.L.; Krasavage, W.J.; DiVincenzo, G.D.; Ziegler, D.A. Commercial-grade methyl heptyl ketone (5-methyl-2-octanone) neurotoxicity: contribution of 5-nonanone. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1982, 62, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.; Steinacher, M.; Lukas, F.; Gaertner, P. Carpe diene! Europium-catalyzed 3,3 and 5,5 rearrangements of aryl-pentadienyl ethers. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 32077–32082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tignibidina, L.G.; Bakibaev, A.A.; Gorshkova, V.K.; Saratikov, A.S.; Krauin'sh, M.P. Synthetic anticonvulsants, antihypoxic agents, and inducers of the liver monooxygenase system. XIX. The synthesis, anticonvulsive, and antihypoxic properties of benzhydrylamine carboxylates. Pharm Chem J 1994, 28, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posternak, J.M.; Dufour, J.J.; Rogg, C.; Vodoz, C.A. Toxicological tests on flavouring matters. II. Pyrazines and other compounds. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1975, 13, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BENZOPHENONE-IMINE-98-5GR.

- Barfknecht, C.F.; Smith, R.V.; Nichols, D.E.; Leseney, J.L.; Long, J.P.; Engelbrecht, J.A. Chemistry and pharmacological evaluation of 1-phenyl-2-propanols and 1-phenyl-2-propanones. J. Pharm. Sci. 1971, 60, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WOLF, M.A.; ROWE, V.K.; MCCOLLISTER, D.D.; HOLLINGSWORTH, R.L.; OYEN, F. Toxicological studies of certain alkylated benzenes and benzene; experiments on laboratory animals. AMA. Arch. Ind. Health 1956, 14, 387–398. [Google Scholar]

| Modell-pollutant | Concentration/amount | Solvent | Conductive salt | Eu(III)-chloride |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium1 | 0,5 g | Ethylene glycol7 | Tetraphenyl-phosphonium chloride9 (PPh4 Cl) |

2.5 mM/l |

| Toluene2 | 50 ml | Toluene2 | ||

| Pentanal3 | 2 ml | Pentanal2 | ||

| Benzhydryl amine4 | 2 ml | Ethylene glycol/ ethane-1,1,2, tricarboxylate8 | ||

| N-1,2-diphenylethyliso- propyl carbamate5 |

100 mg | Ethylene glycol | ||

| Chlorobenzene6 | 2 ml | Ethylene glycol |

| Substance | LD50 rat | Source |

| Benzhydryl amine | 400 mg/kg, oral | [35] |

| 4-methylbiphenyl | 2570 mg/kg, oral | [36] |

| Diphenylmethane | 2250 mg/kg, oral | [36] |

| Benzophenone imine | >2000 mg/kg, oral | [37] |

| Substance | LD50 rat | Source |

| N-1,2-diphenylethylisopropyl carbamate | No data available | |

| 1-dodecyl isocyanate | No data available | |

| 1-phenyl-2-propanol | 520 mg/kg mouse, i.p. | [38] |

| Diethyl bis(hydroxymethyl) malonate | No date available | |

| ethylbenzene | 3500 mg/kg rate, oral | [39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).