Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

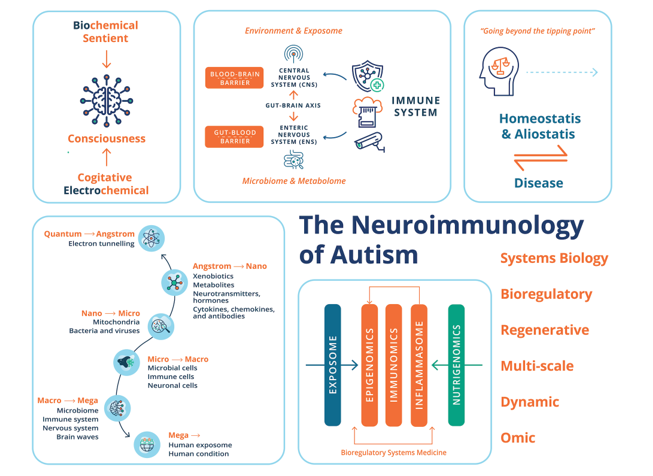

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiological Preambles of ASD

3. Underpinnings of ASD: From Genetic to Environmental and Gene/Environment Etiologies

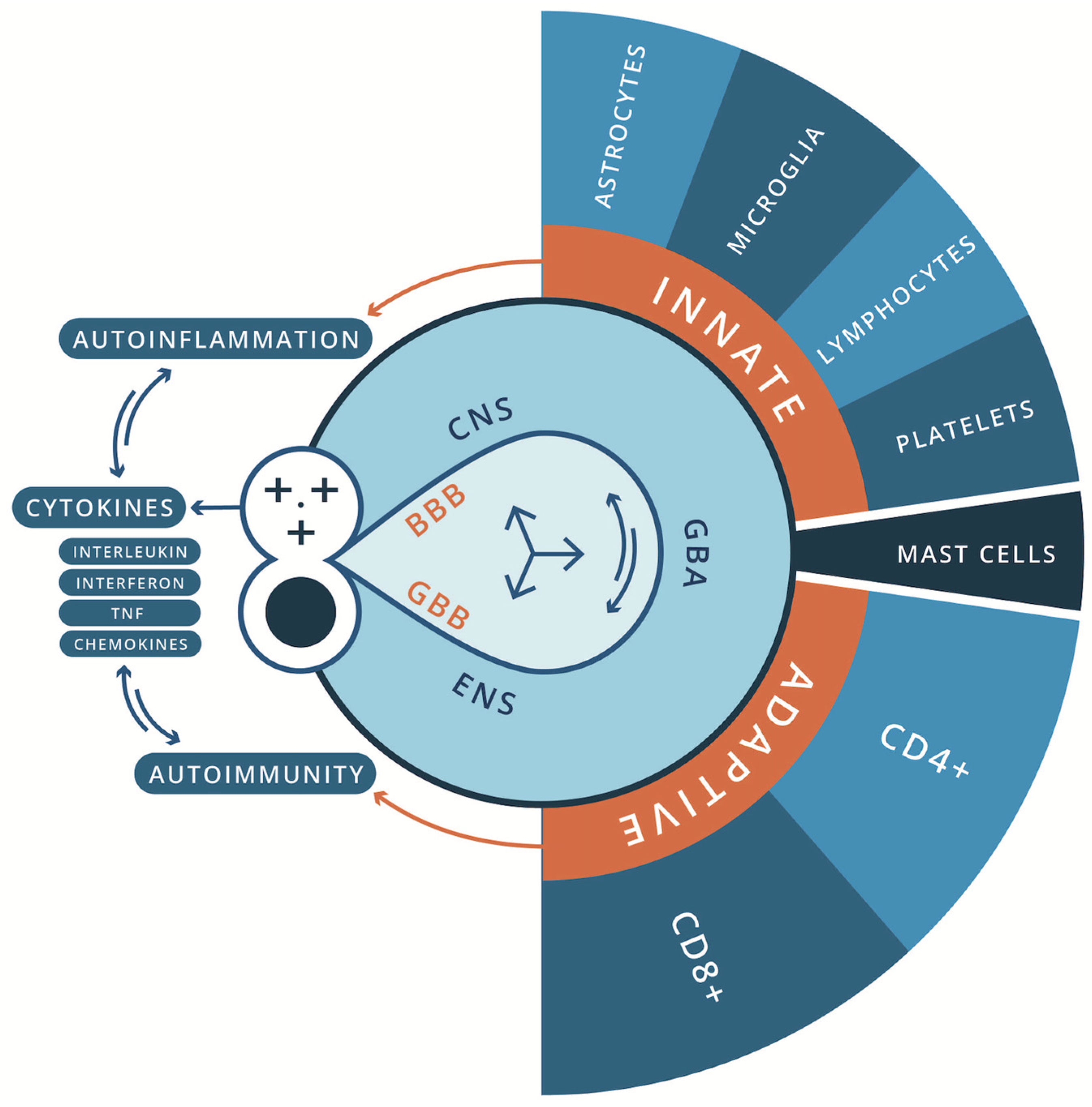

4. The Immune & Nervous Systems: “Systems of Relations”

6. The Pathophysiology of ASD

6.1. ASD, Inflammation & Oxidative Stress

6.2. Innate Immune Deregulation, Encephalitis & ASD

6.2.1. The Pathophysiology of Glial Cells in ASD

6.2.2. The Pathophysiology of NK Cells in ASD

6.2.3. The Pathophysiology of Mast Cells & Dendritic Cells in ASD

6.2.4. The Pathophysiology of Platelets in ASD

6.3. Adaptive Immune Dysfunction, Autoimmune Conditions, & The Pathophysiology of ASD

6.4. Autoimmune Encephalitis, N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDAR) Encephalitis & ASD

6.5. GI Pathology, the Immune System & Pathophysiology of ASD

6.6. Sex Hormones, the Pathogenesis of ASD & the Immune System

7. ASD: From Biochemical, Immune, & Electrophysiological Correlates of Cognition, Sentience & Consciousness to the Biology of the Self

7.1. ASD from Underpinnings of Homeostasis/Allostasis & Sentience

7.2. From Neuroanatomical to Neurofunctional Underpinnings of ASD

7.3. ASD at the Level of Brainwaves & Synchronized Neural Activity

7.4. Neurocognitive Theories of ASD

7.5. ASD the Biology of the Self

8. ASD and Biological Influences: A Two-Way Street

9. Future Directions & Therapeutic Modalities for ASD

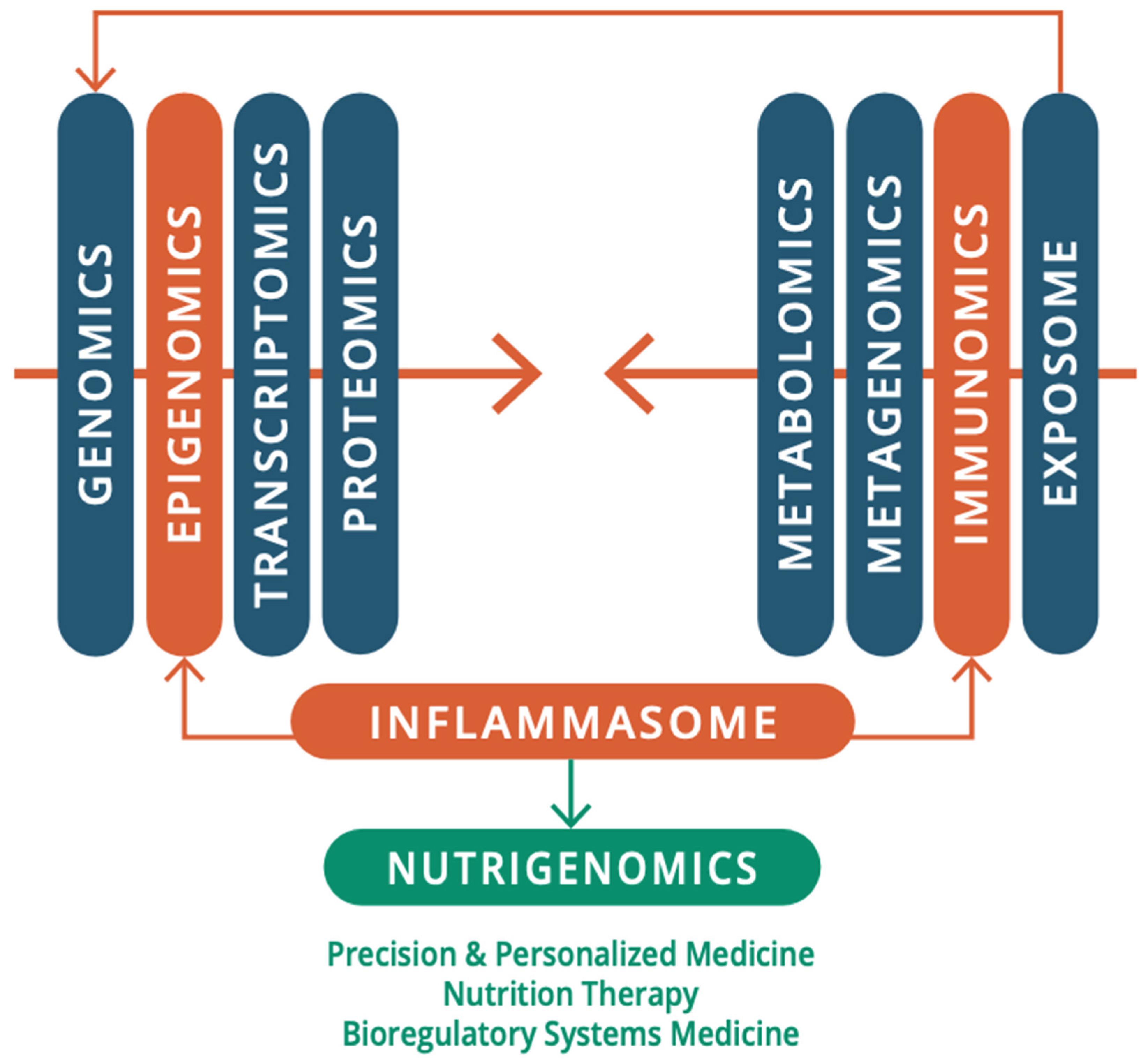

9.1. ASD: Viewpoints from Environmental Exposomes, Omics Technologies & BrSYS Medicine

9.2. ASD Therapeutic Modalities: Standard of Care & State-Of-The-Art

9.3. ASD Therapeutics: Personalized & Precision Nutrition and Mind-Body Modalities

10. Concluding Remarks

References

- Abbaoui, A.; Fatoba, O.; Yamashita, T. Meningeal T cells function in the central nervous system homeostasis and neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1181071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, N.J.; Patabendige, A.A.K.; Dolman, D.E.M.; Yusof, S.R.; Begley, D.J. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abnave, P.; Ghigo, E. Role of the immune system in regeneration and its dynamic interplay with adult stem cells. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 87, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Shaban, T.; Sharna, S.S.; Hosie, S.; Lee, C.Y.Q.; Balasuriya, G.K.; McKeown, S.J.; Franks, A.E.; Hill-Yardin, E.L. Issues for patchy tissues: defining roles for gut-associated lymphoid tissue in neurodevelopment and disease. J. Neural Transm. 2022, 130, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, L.S. Sex Hormones and the Genesis of Autoimmunity. Arch. Dermatol. 2006, 142, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.B.; Borody, T.J.; Kang, D.-W.; Khoruts, A.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R.; Sadowsky, M.J. Microbiota transplant therapy and autism: lessons for the clinic. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 13, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.F.; Ansari, M.A.; Nadeem, A.; Bakheet, S.A.; Al-Ayadhi, L.Y.; Attia, S.M. Elevated IL-16 expression is associated with development of immune dysfunction in children with autism. Psychopharmacology 2018, 236, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.F.; Nadeem, A.; Ansari, M.A.; Bakheet, S.A.; Attia, S.M.; Zoheir, K.M.; Al-Ayadhi, L.Y.; Alzahrani, M.Z.; Alsaad, A.M.; Alotaibi, M.R.; et al. Imbalance between the anti- and pro-inflammatory milieu in blood leukocytes of autistic children. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 82, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.F.; A Zoheir, K.M.; Ansari, M.A.; Nadeem, A.; Bakheet, S.A.; Al-Ayadhi, L.Y.; Alzahrani, M.Z.; Al-Shabanah, O.A.; Al-Harbi, M.M.; Attia, S.M. Dysregulation of Th1, Th2, Th17, and T regulatory cell-related transcription factor signaling in children with autism. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 54, 4390–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aideyan, B.; Martin, G.C.; Beeson, E.T. A Practitioner’s Guide to Breathwork in Clinical Mental Health Counseling. J. Ment. Heal. Couns. 2020, 42, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, C.A. Does the epithelial barrier hypothesis explain the increase in allergy, autoimmunity and other chronic conditions? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, J.S.; Davis, T.N.; Gerow, S.; Avery, S. Decreasing motor stereotypy in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, L.J.; Inman, R.D. Gram-negative pathogens and molecular mimicry: is there a case for mistaken identity? Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 444–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, L.J.; Inman, R.D.; Epstein, F.H. Molecular Mimicry and Autoimmunity. New Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 2068–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.S. “Theory of food” as a neurocognitive adaptation. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2012, 24, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, M.; Huang, B.S.; Notaras, M.J.; Lodhi, A.; Barrio-Alonso, E.; Lituma, P.J.; Wolujewicz, P.; Witztum, J.; Longo, F.; Chen, M.; et al. Astrocytes derived from ASD individuals alter behavior and destabilize neuronal activity through aberrant Ca2+ signaling. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2470–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahayni, O.; Hammond, L.; Hamasaki, H. Does the Wim Hof Method have a beneficial impact on physiological and psychological outcomes in healthy and non-healthy participants? A systematic review. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0286933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayouf, H.A. Growing evidence of pharmacotherapy effectiveness in managing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in young children with or without autism spectrum disorder: a minireview. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1408876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association, D. , & American Psychiatric Association, D. (2013). Diagnostic & statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Vol. 5). American Psychiatric Association Washington, DC.

- American Psychiatric Association Staff, & Spitzer, R. L. (1980). Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Amor, S.; Puentes, F.; Baker, D.; Van Der Valk, P. Inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology 2010, 129, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, R.; Hu, X.; Zhang, F.; Yang, J.; Chen, J. The Role of Intestinal Mucosal Barrier in Autoimmune Disease: A Potential Target. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 871713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W.F.; Dien, B.S.; Brandon, S.K.; Peterson, J.D. Assessment of Bermudagrass and Bunch Grasses as Feedstock for Conversion to Ethanol. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2007, 145, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angajala, A.; Lim, S.; Phillips, J.B.; Kim, J.-H.; Yates, C.; You, Z.; Tan, M. Diverse Roles of Mitochondria in Immune Responses: Novel Insights Into Immuno-Metabolism. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, A.; Alysandratos, K.-D.; Asadi, S.; Zhang, B.; Francis, K.; Vasiadi, M.; Kalogeromitros, D.; Theoharides, T.C. Brief Report: “Allergic Symptoms” in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. More than Meets the Eye? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 41, 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansaldo, E.; Farley, T.K.; Belkaid, Y. Control of Immunity by the Microbiota. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 449–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardalan, M.; Mallard, C. From hormones to behavior through microglial mitochondrial function. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2024, 117, 471–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwood, P. , & Van de Water, J. (2004). A review of autism and the immune response. Clinical & Developmental Immunology, 11(2), 165. [CrossRef]

- Asperger, H. Die „Autistischen Psychopathen” im Kindesalter. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1944, 117, 76–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzalini, D.; Rebollo, I.; Tallon-Baudry, C. Visceral Signals Shape Brain Dynamics and Cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, J.-F. The hygiene hypothesis in autoimmunity: the role of pathogens and commensals. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 18, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badimon, L.; Vilahur, G.; Padro, T. Systems biology approaches to understand the effects of nutrition and promote health. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 83, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahi, C.; Irrmischer, M.; Franken, K.; Fejer, G.; Schlenker, A.; Deijen, J.B.; Engelbregt, H. Effects of conscious connected breathing on cortical brain activity, mood and state of consciousness in healthy adults. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 10578–10589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcells, C.; Xu, Y.; Gil-Solsona, R.; Maitre, L.; Gago-Ferrero, P.; Keun, H.C. Blurred lines: Crossing the boundaries between the chemical exposome and the metabolome. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023, 78, 102407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baniel, A.; Almagor, E.; Sharp, N.; Kolumbus, O.; Herbert, M.R. From fixing to connecting—developing mutual empathy guided through movement as a novel path for the discovery of better outcomes in autism. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2025, 18, 1489345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, F.; Coque, T.M.; Galán, J.C.; Martinez, J.L. The Origin of Niches and Species in the Bacterial World. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, J.; Dissanayake, C. Autism Spectrum Disorders in Infancy and Toddlerhood: A Review of the Evidence on Early Signs, Early Identification Tools, and Early Diagnosis. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2009, 30, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlattani, T. , D’Amelio, C., Cavatassi, A., De Luca, D., Di Stefano, R., Di Berardo, A., et al. (2023). Autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric comorbidities: a narrative review. Journal of Psychopathology. [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S. (2000). Theory of mind and autism: A review. In International Review of Research in Mental Retardation (Vol. 23, pp. 169–184). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7750(00)80010-5.

- Baron-Cohen, S. The cognitive neuroscience of autism. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2004, 75, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Ring, H.; Bullmore, E.; Wheelwright, S.; Ashwin, C.; Williams, S. The amygdala theory of autism. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000, 24, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, S.; Venkataswamy, M.M.; Christopher, R.; Van Amelsvoort, T.; Srinath, S.; Girimaji, S.C.; Ravi, V. Immune aberrations in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a case-control study from a tertiary care neuropsychiatric hospital in India. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 94, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, M.L. Medical Comorbidities in Autism: Challenges to Diagnosis and Treatment. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, M.L.; Kemper, T.L. Neuroanatomic observations of the brain in autism: a review and future directions. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2005, 23, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, N.; Pham-Dinh, D. Biology of Oligodendrocyte and Myelin in the Mammalian Central Nervous System. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 871–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, E. B. E., & Stoodley, C. J. (2013). Chapter One - Autism Spectrum Disorder and the Cerebellum. In G. Konopka (Ed.), International Review of Neurobiology (Vol. 113, pp. 1–34). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-418700-9.00001-0.

- Bei, R.; Masuelli, L.; Palumbo, C.; Modesti, M.; Modesti, A. A common repertoire of autoantibodies is shared by cancer and autoimmune disease patients: Inflammation in their induction and impact on tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 2009, 281, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellot-Saez, A.; Cohen, G.; van Schaik, A.; Ooi, L.; Morley, J.W.; Buskila, Y. Astrocytic modulation of cortical oscillations. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benakis, C.; Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Trezzi, J.-P.; Melton, P.; Liesz, A.; Wilmes, P. The microbiome-gut-brain axis in acute and chronic brain diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 61, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beopoulos, A.; Gea, M.; Fasano, A.; Iris, F. Autonomic Nervous System Neuroanatomical Alterations Could Provoke and Maintain Gastrointestinal Dysbiosis in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Novel Microbiome–Host Interaction Mechanistic Hypothesis. Nutrients 2021, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, S.; Enayati, A.; Redwood, L.; Roger, H.; Binstock, T. Autism: a novel form of mercury poisoning. Med Hypotheses 2001, 56, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H.-R.; Neuhuber, W.L. Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system. Auton. Neurosci. 2000, 85, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.D.; Kogan, M.D.; Strickland, B.B.; Schor, E.L.; Robertson, J.; Newacheck, P.W. A National and State Profile of Leading Health Problems and Health Care Quality for US Children: Key Insurance Disparities and Across-State Variations. Acad. Pediatr. 2011, 11, S22–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagavati, S. Autoimmune Disorders of the Nervous System: Pathophysiology, Clinical Features, and Therapy. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.; Parr, T.; Ramstead, M.; Friston, K. Immunoceptive inference: why are psychiatric disorders and immune responses intertwined? Biol. Philos. 2021, 36, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bien, C.G.; Elger, C.E. Limbic encephalitis: A cause of temporal lobe epilepsy with onset in adult life. Epilepsy Behav. 2007, 10, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Meguid, N.A.; El-Bana, M.A.; Tinkov, A.A.; Saad, K.; Dadar, M.; Hemimi, M.; Skalny, A.V.; Hosnedlová, B.; Kizek, R.; et al. Oxidative Stress in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 2314–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Mkhitaryan, M.; Sahakyan, E.; Fereshetyan, K.; A Meguid, N.; Hemimi, M.; Nashaat, N.H.; Yenkoyan, K. Linking Environmental Chemicals to Neuroinflammation and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Mechanisms and Implications for Prevention. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 6328–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Blalock, J. The immune system as a sensory organ. J. Immunol. 1984, 132, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaxill, M.F.; Redwood, L.; Bernard, S. Thimerosal and autism? A plausible hypothesis that should not be dismissed. Med Hypotheses 2004, 62, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleuler, E. (1911). Dementia praecox: oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien. F. Deuticke.

- Bleuler, E. (1951). Autistic thinking. In Organization & pathology of thought: Selected sources (pp. 399–437). Columbia University Press.

- Bojarskaite, L.; Bjørnstad, D.M.; Pettersen, K.H.; Cunen, C.; Hermansen, G.H.; Åbjørsbråten, K.S.; Chambers, A.R.; Sprengel, R.; Vervaeke, K.; Tang, W.; et al. Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling is reduced during sleep and is involved in the regulation of slow wave sleep. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordenstein, S.R.; Theis, K.R.; Waldor, M.K. Host Biology in Light of the Microbiome: Ten Principles of Holobionts and Hologenomes. PLOS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braunschweig, D.; Ashwood, P.; Krakowiak, P.; Hertzpicciotto, I.; Hansen, R.; Croen, L.A.; Pessah, I.N.; Vandewater, J.; Van de Water, J. Autism: Maternally derived antibodies specific for fetal brain proteins. NeuroToxicology 2007, 29, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breece, E.; Paciotti, B.; Nordahl, C.W.; Ozonoff, S.; Van de Water, J.A.; Rogers, S.J.; Amaral, D.; Ashwood, P. Myeloid dendritic cells frequencies are increased in children with autism spectrum disorder and associated with amygdala volume and repetitive behaviors. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2013, 31, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brincker, M.; Torres, E.B. Noise from the periphery in autism. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 52681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, W.v.D.; van Bilsen, J.; Salic, K.; Hoevenaars, F.P.M.; Verschuren, L.; Kleemann, R.; Bouwman, J.; Ronnett, G.V.; van Ommen, B.; Wopereis, S. Current and Future Nutritional Strategies to Modulate Inflammatory Dynamics in Metabolic Disorders. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, G.; Nekolla, E.A.; Nosske, D.; Griebel, J. Risks and safety aspects related to PET/MR examinations. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 36, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.C.; Mehl-Madrona, L. Autoimmune and gastrointestinal dysfunctions: does a subset of children with autism reveal a broader connection? Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 5, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buie, T.; Campbell, D.B.; Fuchs, G.J., 3rd; Furuta, G.T.; Levy, J.; Vandewater, J.; Whitaker, A.H.; Atkins, D.; Bauman, M.L.; Beaudet, A.L.; et al. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Gastrointestinal Disorders in Individuals With ASDs: A Consensus Report. Pediatrics 2010, 125 (Suppl. 1), S1–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnouf, T.; Walker, T.L. The multifaceted role of platelets in mediating brain function. Blood 2022, 140, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns-Naas, L.A.; Dearman, R.J.; Germolec, D.R.; Kaminski, N.E.; Kimber, I.; Ladics, G.S.; Luebke, R.W.; Pfau, J.C.; Pruett, S.B. “Omics” Technologies and the Immune System. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2006, 16, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buskila, Y.; Bellot-Saez, A.; Morley, J.W. Generating Brain Waves, the Power of Astrocytes. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G.; Watson, B.O. Brain rhythms and neural syntax: implications for efficient coding of cognitive content and neuropsychiatric disease. Dialog- Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnin, A. In vivo imaging of neuroinflammation. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002, 12, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, J.; Frye, R.E.; Walker, S.J. The lifetime social cost of autism: 1990–2029. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calçada, D.; Vianello, D.; Giampieri, E.; Sala, C.; Castellani, G.; de Graaf, A.; Kremer, B.; van Ommen, B.; Feskens, E.; Santoro, A.; et al. The role of low-grade inflammation and metabolic flexibility in aging and nutritional modulation thereof: A systems biology approach. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2014, 136-137, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantando, I.; Centofanti, C.; D’aLessandro, G.; Limatola, C.; Bezzi, P. Metabolic dynamics in astrocytes and microglia during post-natal development and their implications for autism spectrum disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1354259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carré, A.; Chevallier, C.; Robel, L.; Barry, C.; Maria, A.-S.; Pouga, L.; Philippe, A.; Pinabel, F.; Berthoz, S. Tracking Social Motivation Systems Deficits: The Affective Neuroscience View of Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 3351–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. (2021). Managing Chronic Health Conditions. CDC Healthy Schools. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/chronicconditions.htm. 1 June.

- Cekici, H.; Sanlier, N. Current nutritional approaches in managing autism spectrum disorder: A review. Nutr. Neurosci. 2017, 22, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellot, G.; Cherubini, E. GABAergic Signaling as Therapeutic Target for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Pediatr. 2014, 2, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, C., & Schaefer, C. (2015). 2.10 - Epilepsy and antiepileptic medications. In C. Schaefer, P. Peters, & R. K. Miller (Eds.), Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation (Third Edition) (pp. 251–291). San Diego: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-408078-2.00011-1.

- Chavez, J.A.; Zappaterra, M. Can Wim Hof Method breathing induce conscious metabolic waste clearance of the brain? Med Hypotheses 2023, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Chiu, C.-H. Current and future applications of fecal microbiota transplantation for children. Biomed. J. 2021, 45, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, X.; Tjia, M.; Thapliyal, S. Homeostatic plasticity and excitation-inhibition balance: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2022, 75, 102553–102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, S.L.; Kapoor, S.; Carvalho, C.; Bajénoff, M.; Gentek, R. Mast cell ontogeny: From fetal development to life-long health and disease. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 315, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirumbolo, S.; Bjørklund, G. PERM Hypothesis: The Fundamental Machinery Able to Elucidate the Role of Xenobiotics and Hormesis in Cell Survival and Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Kim, J.H.; Yang, H.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Cortese, S.; Smith, L.; Koyanagi, A.; Dragioti, E.; Radua, J.; Fusar-Poli, P.; et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for irritability in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis with the GRADE assessment. Mol. Autism 2024, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślińska, A.; Kostyra, E.; Savelkoul, H.F. ; Wageningen University & Research Treating Autism Spectrum Disorder with Gluten-Free and Casein-Free Diet: The Underlying Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis Mechanisms. Clin. Immunolgy Immunother. 2017, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clappison, E.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Zis, P. Psychiatric Manifestations of Coeliac Disease, a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copf, T. Impairments in dendrite morphogenesis as etiology for neurodevelopmental disorders and implications for therapeutic treatments. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 946–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, M. Bodily self and immune self: is there a link? Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, E.K.; Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Fierer, N.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R. Bacterial Community Variation in Human Body Habitats Across Space and Time. Science 2009, 326, 1694–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coury, D.L.; Anagnostou, E.; Manning-Courtney, P.; Reynolds, A.; Cole, L.; McCoy, R.; Whitaker, A.; Perrin, J.M. Use of Psychotropic Medication in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Pediatrics 2012, 130, S69–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crépeaux, G.; Authier, F.-J.; Exley, C.; Luján, L.; Gherardi, R.K. The role of aluminum adjuvants in vaccines raises issues that deserve independent, rigorous and honest science. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 2020, 62, 126632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O'RIordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaba, G. Hormones in the immune system and their possible role. A critical review. Acta Microbiol. Et Immunol. Hung. 2014, 61, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutolo, M.; Capellino, S.; Sulli, A.; Serioli, B.; Secchi, M.E.; Villaggio, B.; Straub, R.H. Estrogens and Autoimmune Diseases. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2006, 1089, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwik, J. C. (2021). Spiritual needs of people with autism spectrum disorder. In Spiritual Needs in Research and Practice: The Spiritual Needs Questionnaire as a Global Resource for Health and Social Care (pp. 265–280). Springer.

- D’adamo, C.R.; Nelson, J.L.; Miller, S.N.; Hong, M.R.; Lambert, E.; Ruhm, H.T. Reversal of Autism Symptoms among Dizygotic Twins through a Personalized Lifestyle and Environmental Modification Approach: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daëron, M. The immune system as a system of relations. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 984678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’aGostino, P.M.; Gottfried-Blackmore, A.; Anandasabapathy, N.; Bulloch, K. Brain dendritic cells: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 124, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, E., D. Tricklebank, M., & Wichers, R. (2019). Chapter Two - Neurodevelopmental roles and the serotonin hypothesis of autism spectrum disorder. In M. D. Tricklebank & E. Daly (Eds.), The Serotonin System (pp. 23–44). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813323-1.00002-5.

- Damasio, A. Mental self: The person within. Nature 2003, 423, 227–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, E. (2018). Physiology of the cerebellum. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 154, 85–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63956-1.00006-0.

- Davenport, P.; Sola-Visner, M. Platelets in the neonate: Not just a small adult. Res. Pr. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 6, e12719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Bishop, D.; Manstead, A.S.R.; Tantam, D. Face Perception in Children with Autism and Asperger's Syndrome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1994, 35, 1033–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgio, R.; Guerrini, S.; Barbara, G.; Stanghellini, V.; De Ponti, F.; Corinaldesi, R.; Moses, P.L.; A Sharkey, K.; Mawe, G.M. Inflammatory neuropathies of the enteric nervous system☆. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, 1872–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Casale, A.; Ferracuti, S.; Alcibiade, A.; Simone, S.; Modesti, M.N.; Pompili, M. Neuroanatomical correlates of autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2022, 325, 111516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafield-Butt, J.; Ciaunica, A. Sensorimotor foundations of self-consciousness in utero. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2024, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, J.L.; Little, M.; Cui, J.Y. Gut microbiome: An intermediary to neurotoxicity. NeuroToxicology 2019, 75, 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Yi, P.; Xiong, Y.; Ying, J.; Lin, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wei, G.; Wang, X.; Hua, F. Gut Metabolites Acting on the Gut-Brain Axis: Regulating the Functional State of Microglia. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 480–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denman, A.M. Sex hormones, autoimmune diseases, and immune responses. BMJ 1991, 303, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deth, R.C. Autism: A Redox/Methylation Disorder. Glob. Adv. Heal. Med. 2013, 2, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethlefsen, L.; McFall-Ngai, M.; Relman, D.A. An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human–microbe mutualism and disease. Nature 2007, 449, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Liberto, D.; D’anneo, A.; Carlisi, D.; Emanuele, S.; De Blasio, A.; Calvaruso, G.; Giuliano, M.; Lauricella, M. Brain Opioid Activity and Oxidative Injury: Different Molecular Scenarios Connecting Celiac Disease and Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, P.M.; Rose, C.E.; McArthur, D.; Maenner, M. National and State Estimates of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 4258–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimmeler, S.; Ding, S.; A Rando, T.; Trounson, A. Translational strategies and challenges in regenerative medicine. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'MEllo, A.M.; Stoodley, C.J. Cerebro-cerebellar circuits in autism spectrum disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, M.; Foley, K.-R.; Schloss, J. Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Autism – A Systematic Review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, K.; Finlay, B.B. Early-life interactions between the microbiota and immune system: impact on immune system development and atopic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Benveniste, E.N. Immune function of astrocytes. Glia 2001, 36, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, A.P.A.; Basson, M.A. The neuroanatomy of autism – a developmental perspective. Am. J. Anat. 2016, 230, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dukhinova, M.; Kuznetsova, I.; Kopeikina, E.; Veniaminova, E.; Yung, A.W.; Veremeyko, T.; Levchuk, K.; Barteneva, N.S.; Wing-Ho, K.K.; Yung, W.-H.; et al. Platelets mediate protective neuroinflammation and promote neuronal plasticity at the site of neuronal injury. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2018, 74, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meimand, S.E.; Rostam-Abadi, Y.; Rezaei, N. Autism spectrum disorders and natural killer cells: a review on pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 17, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, C. The neuroanatomy of autism spectrum disorder: An overview of structural neuroimaging findings and their translatability to the clinical setting. Autism 2016, 21, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmiston, E.; Ashwood, P.; Van de Water, J. Autoimmunity, Autoantibodies, and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ansary, A.; Bhat, R.S.; Zayed, N. Gut Microbiome and Sex Bias in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 7, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enstrom, A.M.; Lit, L.; Onore, C.E.; Gregg, J.P.; Hansen, R.L.; Pessah, I.N.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Van de Water, J.A.; Sharp, F.R.; Ashwood, P. Altered gene expression and function of peripheral blood natural killer cells in children with autism. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2008, 23, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.S.; McEwen, B.S.; Ickovics, J.R. Embodying Psychological Thriving: Physical Thriving in Response to Stress. J. Soc. Issues 1998, 54, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, M.L.; McAllister, A.K. Maternal immune activation: Implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science 2016, 353, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exley, C. Human exposure to aluminium. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2013, 15, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exley, C.; Clarkson, E. Aluminium in human brain tissue from donors without neurodegenerative disease: A comparison with Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis and autism. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famitafreshi, H.; Karimian, M. Overview of the Recent Advances in Pathophysiology and Treatment for Autism. CNS Neurol. Disord. - Drug Targets 2018, 17, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Ma, J.; Ma, R.; Suo, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, Y. Microglia Modulate Neurodevelopment in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, C.A.; Thurm, A.E.; Honnekeri, B.; Kim, P.; Swedo, S.E.; Han, J.C. The contribution of platelets to peripheral BDNF elevation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A. Leaky Gut and Autoimmune Diseases. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 42, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Halt, A.R.; Realmuto, G.; Earle, J.; Kist, D.A.; Thuras, P.; Merz, A. Purkinje Cell Size Is Reduced in Cerebellum of Patients with Autism. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2002, 22, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, S.L.; Abel, T.; Brodkin, E.S. Sex Differences in Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiano, A.J.; Xu, Y.; Tustison, N.J.; Marsh, R.L.; Baker, W.; Smirnov, I.; Overall, C.C.; Gadani, S.P.; Turner, S.D.; Weng, Z.; et al. Unexpected role of interferon-γ in regulating neuronal connectivity and social behaviour. Nature 2016, 535, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipek, P.A.; Juranek, J.; Nguyen, M.T.; Cummings, C.; Gargus, J.J. Relative Carnitine Deficiency in Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, G.W.; Strauss, C.; Montero-Marin, J.; Cavanagh, K. Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, D. Walter B. Cannon and homeostasis.. 1984, 51, 609–40. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, S.; Rutter, M. Genetic influences and infantile autism. Nature 1977, 265, 726–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.D.; Van Domselaar, G.; Bernstein, C.N. The Gut Microbiota in Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraguas, D.; Díaz-Caneja, C.M.; Pina-Camacho, L.; Moreno, C.; Durán-Cutilla, M.; Ayora, M.; González-Vioque, E.; de Matteis, M.; Hendren, R.L.; Arango, C.; et al. Dietary Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20183218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frith, U. Autism and theory of mind in everyday life. Soc. Dev. 1994, 3, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, U.; Happé, F. Autism: beyond “theory of mind”. Cognition 1994, 50, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frith, U.; Happé, F. Theory of Mind and Self-Consciousness: What Is It Like to Be Autistic? Mind Lang. 1999, 14, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E.; Rincon, N.; McCarty, P.J.; Brister, D.; Scheck, A.C.; Rossignol, D.A. Biomarkers of mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 197, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Schroder, K.; Wu, H. Mechanistic insights from inflammasome structures. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.; Rahona, E.; Fisher, S.; Caravanos, J.; Webb, D.; Kass, D.; Matte, T.; Landrigan, P.J. Pollution and non-communicable disease: time to end the neglect. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2018, 2, e96–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furness, J.B.; Callaghan, B.P.; Rivera, L.R.; Cho, H.-J. The Enteric Nervous System and Gastrointestinal Innervation: Integrated Local and Central Control. In Microbial Endocrinology: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; Volume 817, pp. 39–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, M.S.; Sheriff, H.; Dalmau, J.; Tilley, D.H.; Glaser, C.A. The Frequency of Autoimmune N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis Surpasses That of Individual Viral Etiologies in Young Individuals Enrolled in the California Encephalitis Project. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, S.; Sacco, R.; Persico, A.M. Blood serotonin levels in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallotto, S.; Sack, A.T.; Schuhmann, T.; de Graaf, T.A. Oscillatory Correlates of Visual Consciousness. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1147–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvez-Contreras, A.Y.; Zarate-Lopez, D.; Torres-Chavez, A.L.; Gonzalez-Perez, O. Role of Oligodendrocytes and Myelin in the Pathophysiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, D.; Mohammad, S.S.; Sharma, S. Autoimmune Encephalitis in Children: An Update. Indian Pediatr. 2020, 57, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaugler, T.; Klei, L.; Sanders, S.J.; A Bodea, C.; Goldberg, A.P.; Lee, A.B.; Mahajan, M.; Manaa, D.; Pawitan, Y.; Reichert, J.; et al. Most genetic risk for autism resides with common variation. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. A., G.; J.K., K.; M.R., G. The biological basis of autism spectrum disorders: Understanding causation and treatment by clinical geneticists. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2010, 70, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geier, D.A.; King, P.G.; Hooker, B.S.; Dórea, J.G.; Kern, J.K.; Sykes, L.K.; Geier, M.R. Thimerosal: Clinical, epidemiologic and biochemical studies. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 444, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.-H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Q.-L.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, P.-H. Enteric Nervous System: The Bridge Between the Gut Microbiota and Neurological Disorders. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 810483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuis, S.J. What's Out There Making Us Sick? J. Environ. Public Heal. 2011, 2012, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, M.D. The Enteric Nervous System: A Second Brain. Hosp. Pr. 1999, 34, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, M. D. (2022). The Shaggy Dog Story of Enteric Signaling: Serotonin, a Molecular Megillah. In N. J. Spencer, M. Costa, & S. M. Brierley (Eds.), The Enteric Nervous System II (pp. 307–318). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Ghanizadeh, A.; Akhondzadeh, S.; Hormozi, M.; Makarem, A.; Abotorabi-Zarchi, M.; Firoozabadi, A. Glutathione-Related Factors and Oxidative Stress in Autism, A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 4000–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaziuddin, M.; Al-Owain, M. Autism Spectrum Disorders and Inborn Errors of Metabolism: An Update. Pediatr. Neurol. 2013, 49, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Michalon, A.; Lindemann, L.; Fontoura, P.; Santarelli, L. Drug discovery for autism spectrum disorder: challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianchecchi, E.; Delfino, D.V.; Fierabracci, A. NK cells in autoimmune diseases: Linking innate and adaptive immune responses. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giron, M.C.; Mazzi, U. Molecular imaging of microbiota-gut-brain axis: searching for the right targeted probe for the right target and disease. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2021, 92, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gładysz, D.; Krzywdzińska, A.; Hozyasz, K.K. Immune Abnormalities in Autism Spectrum Disorder—Could They Hold Promise for Causative Treatment? Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 6387–6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobin, V.; Van Steendam, K.; Denys, D.; Deforce, D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a novel class of immunosuppressants. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 20, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, W.A.; Osann, K.; Filipek, P.A.; Laulhere, T.; Jarvis, K.; Modahl, C.; Flodman, P.; Spence, M.A. Language and Other Regression: Assessment and Timing. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2003, 33, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.W.; Burmeister, Y.; Cesnulevicius, K.; Herbert, M.; Kane, M.; Lescheid, D.; McCaffrey, T.; Schultz, M.; Seilheimer, B.; Smit, A.; et al. Bioregulatory systems medicine: an innovative approach to integrating the science of molecular networks, inflammation, and systems biology with the patient's autoregulatory capacity? Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goubau, C.; Buyse, G.M.; Van Geet, C.; Freson, K. The contribution of platelet studies to the understanding of disease mechanisms in complex and monogenetic neurological disorders. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 56, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, M.B.; Streit, W.J. Microglia: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 119, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, M.B.; Stre'RT, W.J. Microglia: Immune Network in the CNS. Brain Pathol. 1990, 1, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.J.; Park, K.; Bhatt-Mehta, V.; Snyder, D.; Burckart, G.J. Regulatory Considerations for the Mother, Fetus and Neonate in Fetal Pharmacology Modeling. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, G. , & Tobach, E. (2014). Behavioral Evolution & Integrative Levels: The T.C. Schneirla Conferences Series, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis.

- Gropman, A., & Sadle, C. J. (2024). Epigenetics of autism spectrum disorder. In Neuropsychiatric Disorders & Epigenetics (pp. 81–102). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-18516-8.00017-X.

- Guan, A.; Wang, S.; Huang, A.; Qiu, C.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Deng, B. The role of gamma oscillations in central nervous system diseases: Mechanism and treatment. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 962957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Gupta, M. Off-label psychopharmacological interventions for autism spectrum disorders: strategic pathways for clinicians. CNS Spectrums 2023, 29, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gzielo, K.; Nikiforuk, A. Astroglia in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacohen, Y.; Wright, S.; Gadian, J.; Vincent, A.; Lim, M.; Wassmer, E.; Lin, J. N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antibodies encephalitis mimicking an autistic regression. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 1092–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafizi, S.; Tabatabaei, D.; Lai, M.-C. Review of Clinical Studies Targeting Inflammatory Pathways for Individuals With Autism. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmayer, J.; Cleveland, S.; Torres, A.; Phillips, J.; Cohen, B.; Torigoe, T.; Miller, J.; Fedele, A.; Collins, J.; Smith, K.; et al. Genetic Heritability and Shared Environmental Factors Among Twin Pairs With Autism. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameroff, S. The “conscious pilot”—dendritic synchrony moves through the brain to mediate consciousness. J. Biol. Phys. 2009, 36, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampe, C.S.; Mitoma, H. A Breakdown of Immune Tolerance in the Cerebellum. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Peng, T.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, W.; Xie, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, C.; Xie, N. Mitochondrial-regulated Tregs: potential therapeutic targets for autoimmune diseases of the central nervous system. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1301074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaford, A.; Johnson, S.C. The immune system as a driver of mitochondrial disease pathogenesis: a review of evidence. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happé, F.G.E. Wechsler IQ Profile and Theory of Mind in Autism: A Research Note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1994, 35, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, D. Autoimmune Encephalitis in Children. Pediatr. Neurol. 2022, 132, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkey, J. The Epidemiology of Selected Chronic Childhood Health Conditions. Child. Heal. Care 1983, 12, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J. Leo Kanner and autism: a 75-year perspective. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 30, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haruwaka, K.; Ikegami, A.; Tachibana, Y.; Ohno, N.; Konishi, H.; Hashimoto, A.; Matsumoto, M.; Kato, D.; Ono, R.; Kiyama, H.; et al. Dual microglia effects on blood brain barrier permeability induced by systemic inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hasib, R.; Ali, C.; Rahman, H.; Ahmed, S.; Sultana, S.; Summa, S.Z.; Shimu, M.S.S.; Afrin, Z.; Jamal, M.A.H.M. Integrated gene expression profiling and functional enrichment analyses to discover biomarkers and pathways associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome and autism spectrum disorder to identify new therapeutic targets. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 42, 11299–11321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawgood, S.; Hook-Barnard, I.G.; O’bRien, T.C.; Yamamoto, K.R. Precision medicine: Beyond the inflection point. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 300ps17–300ps17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, S.; Spradling-Reeves, K.D.; Papoutsis, A.; Walker, S.J. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing Identifies Dysbiosis in Triplet Sibling with Gastrointestinal Symptoms and ASD. Children 2020, 7, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberling, C.A.; Dhurjati, P.S.; Sasser, M. Hypothesis for a systems connectivity model of autism spectrum disorder pathogenesis: Links to gut bacteria, oxidative stress, and intestinal permeability. Med Hypotheses 2013, 80, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemskerk, V.H.; Daemen, M.A.; A Buurman, W. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and growth hormone (GH) in immunity and inflammation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999, 10, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, C.N.; Olofsson, L.E. The role of the gut microbiota in development, function and disorders of the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system. J. Neuroendocr. 2019, 31, e12684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helt, M.; Kelley, E.; Kinsbourne, M.; Pandey, J.; Boorstein, H.; Herbert, M.; Fein, D. Can Children with Autism Recover? If So, How? Neuropsychol. Rev. 2008, 18, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, E.; van Bergeijk, D.; Oosting, R.S.; Redegeld, F.A. Mast cells in neuroinflammation and brain disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 79, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, F.L.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Becher, B. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herberman, R.B.; Ortaldo, J.R. Natural killer cells: their roles in defenses against disease. Science 1981, 214, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M. , & Weintraub, K. (2013). The Autism Revolution: Whole-Body Strategies for Making Life All It Can Be. Random House Publishing Group.

- Herbert, M.R. Large Brains in Autism: The Challenge of Pervasive Abnormality. Neurosci. 2005, 11, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M. S. 01.03 Autism: from static genetic brain defect to dynamic gene-environment modulated pathophysiology. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M. R. (2014). Translational implications of a whole-body approach to brain health in autism: how transduction between metabolism and electrophysiology points to mechanisms for neuroplasticity. In Frontiers in Autism Research: New Horizons for Diagnosis & Treatment, 515–556. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/9789814602167_0021.

- Herbert, M.R.; Sage, C. Autism and EMF? Plausibility of a pathophysiological link – Part I. Pathophysiology 2013, 20, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M.R.; Sage, C. Autism and EMF? Plausibility of a pathophysiological link part II. Pathophysiology 2013, 20, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M.R.; Ziegler, D.A.; Deutsch, C.K.; O'Brien, L.M.; Kennedy, D.N.; Filipek, P.A.; Bakardjiev, A.I.; Hodgson, J.; Takeoka, M.; Makris, N.; et al. Brain asymmetries in autism and developmental language disorder: a nested whole-brain analysis. Brain 2004, 128, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M.R.; Ziegler, D.A.; Deutsch, C.K.; O'BRien, L.M.; Lange, N.; Bakardjiev, A.; Hodgson, J.; Adrien, K.T.; Steele, S.; Makris, N.; et al. Dissociations of cerebral cortex, subcortical and cerebral white matter volumes in autistic boys. Brain 2003, 126, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, M.R.; Ziegler, D.A.; Makris, N.; Filipek, P.A.; Kemper, T.L.; Normandin, J.J.; Sanders, H.A.; Kennedy, D.N.; Caviness, V.S. Localization of white matter volume increase in autism and developmental language disorder. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 55, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Schmidt, R.J.; Krakowiak, P. Understanding environmental contributions to autism: Causal concepts and the state of science. Autism Res. 2018, 11, 554–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, A.; Crabtree, J.; Stott, J. ‘Suddenly the first fifty years of my life made sense’: Experiences of older people with autism. Autism 2017, 22, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higdon, R.; Earl, R.K.; Stanberry, L.; Hudac, C.M.; Montague, E.; Stewart, E.; Janko, I.; Choiniere, J.; Broomall, W.; Kolker, N.; et al. The Promise of Multi-Omics and Clinical Data Integration to Identify and Target Personalized Healthcare Approaches in Autism Spectrum Disorders. OMICS: A J. Integr. Biol. 2015, 19, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, E.L. Executive dysfunction in autism☆. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004, 8, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, E.L. Evaluating the theory of executive dysfunction in autism. Dev. Rev. 2004, 24, 189–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K. (1990). The decline of childhood mortality.

- Hiller-Sturmhöfel, S. , & Bartke, A. (1998). The endocrine system - An overview. Alcohol health & Research World, 22, 153–64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 1570. [Google Scholar]

- Hirahara, K.; Nakayama, T. CD4 + T-cell subsets in inflammatory diseases: beyond the T h 1/T h 2 paradigm. Int. Immunol. 2016, 28, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.; Ross, D.A. More Than a Gut Feeling: The Implications of the Gut Microbiota in Psychiatry. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81, e35–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, B.; Kern, J.; Geier, D.; Haley, B.; Sykes, L.; King, P.; Geier, M. Methodological Issues and Evidence of Malfeasance in Research Purporting to Show Thimerosal in Vaccines Is Safe. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlin, C.; Falkmer, M.; Parsons, R.; Albrecht, M.A.; Falkmer, T.; Mulle, J.G. The Cost of Autism Spectrum Disorders. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e106552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hridi, S.U.; Barbour, M.; Wilson, C.; Franssen, A.J.; Harte, T.; Bushell, T.J.; Jiang, H.-R. Increased Levels of IL-16 in the Central Nervous System during Neuroinflammation Are Associated with Infiltrating Immune Cells and Resident Glial Cells. Biology 2021, 10, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, E.Y.; McBride, S.W.; Chow, J.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Patterson, P.H. Modeling an autism risk factor in mice leads to permanent immune dysregulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 12776–12781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Zou, L.; Healy, S.; Tse, C.Y.A.; Li, C. Effects of Mind-Body Exercises on Health-related Outcomes in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H.K.; Ko, E.M.; Rose, D.; Ashwood, P. Immune Dysfunction and Autoimmunity as Pathological Mechanisms in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H.K.; Rose, D.; Ashwood, P. The Gut Microbiota and Dysbiosis in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulme, S.R.; Jones, O.D.; Raymond, C.R.; Sah, P.; Abraham, W.C. Mechanisms of heterosynaptic metaplasticity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries S, Bystrianyk R (2013) Dissolving illusions: Disease, vaccines and the forgotten history. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Hurley-Hanson, A. E., Giannantonio, C. M., Griffiths, A. J., Hurley-Hanson, A. E., Giannantonio, C. M., & Griffiths, A. J. (2020). The costs of autism. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29049-8_3.

- Hussaini, S.M.Q.; Jang, M.H. New Roles for Old Glue: Astrocyte Function in Synaptic Plasticity and Neurological Disorders. Int. Neurourol. J. 2018, 22, S106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Ichim, T.; Solano, F.; Glenn, E.; Morales, F.; Smith, L.; Zabrecky, G.; Riordan, N.H. Stem Cell Therapy for Autism. J. Transl. Med. 2007, 5, 30–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, J. K. , MacSween, J., & Kerns, K. A. (2011). History and evolution of the autism spectrum disorders. In International Handbook of Autism & Pervasive Developmental disorders (pp. 3–16). Springer.

- Jaga, K.; Dharmani, C. The interrelation between organophosphate toxicity and the epidemiology of depression and suicide. Rev. Environ. Heal. 2007, 22, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrold, C.; Russell, J. Counting Abilities in Autism: Possible Implications for Central Coherence Theory. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1997, 27, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaswal, V.K.; Wayne, A.; Golino, H. Eye-tracking reveals agency in assisted autistic communication. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaswal, V.K.; Lampi, A.J.; Stockwell, K.M. Literacy in nonspeaking autistic people. Autism 2024, 28, 2503–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenne, C.N.; Urrutia, R.; Kubes, P. Platelets: bridging hemostasis, inflammation, and immunity. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2013, 35, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.M.; Cowan, M.; Moonah, S.N.; Petri, W.A. The Impact of Systemic Inflammation on Neurodevelopment. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E. The neurophysics of consciousness. Brain Res. Rev. 2002, 39, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.P.; Williamson, L.; Konsoula, Z.; Anderson, R.; Reissner, K.J.; Parker, W. Evaluating the Role of Susceptibility Inducing Cofactors and of Acetaminophen in the Etiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Life 2024, 14, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Hugot, J.-P.; Barreau, F. Peyer's Patches: The Immune Sensors of the Intestine. Int. J. Inflamm. 2010, 2010, 823710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyonouchi, H. Food allergy and autism spectrum disorders: Is there a link? Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2009, 9, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyonouchi, H. Autism spectrum disorder and a possible role of anti-inflammatory treatments: experience in the pediatric allergy/immunology clinic. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1333717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminska, A.; Cheliout-Heraut, F.; Eisermann, M.; de Villepin, A.T.; Lamblin, M.D. EEG in children, in the laboratory or at the patient's bedside. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2015, 45, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-W.; Adams, J.B.; Coleman, D.M.; Pollard, E.L.; Maldonado, J.; McDonough-Means, S.; Caporaso, J.G.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Long-term benefit of Microbiota Transfer Therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanner, L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv. Child 1943, 2, 217–250. [Google Scholar]

- Karhu, E.; Zukerman, R.; Eshraghi, R.S.; Mittal, J.; Deth, R.C.; Castejon, A.M.; Trivedi, M.; Mittal, R.; A Eshraghi, A. Nutritional interventions for autism spectrum disorder. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 78, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karl, J.P.; Hatch, A.M.; Arcidiacono, S.M.; Pearce, S.C.; Pantoja-Feliciano, I.G.; Doherty, L.A.; Soares, J.W. Effects of Psychological, Environmental and Physical Stressors on the Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, O. Chemical safety and the exposome. Emerg. Contam. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I.; Behl, T.; Aleya, L.; Rahman, H.; Kumar, A.; Arora, S.; Akter, R. Role of metallic pollutants in neurodegeneration: effects of aluminum, lead, mercury, and arsenic in mediating brain impairment events and autism spectrum disorder. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8989–9001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, M.S.; Dalmau, J. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, autoimmunity, and psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 176, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, B. A., Lees, J. G., & Moalem-Taylor, G. (2019). The Roles of Regulatory T Cells in Central Nervous System Autoimmunity. In H. Mitoma & M. Manto (Eds.), Neuroimmune Diseases: From Cells to the Living Brain (pp. 167–193). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19515-1_6.

- Keller, A.; Rimestad, M.L.; Rohde, J.F.; Petersen, B.H.; Korfitsen, C.B.; Tarp, S.; Lauritsen, M.B.; Händel, M.N. The Effect of a Combined Gluten- and Casein-Free Diet on Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.S.; Apple, C.G.; Gharaibeh, R.; Pons, E.E.B.; Thompson, C.W.B.; Kannan, K.B.; Darden, D.B.; Efron, P.A.; Thomas, R.M.; Mohr, A.M. Stress-related changes in the gut microbiome after trauma. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021, 91, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, T.L.; Bauman, M. Neuropathology of Infantile Autism. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1998, 57, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepser, L.-J.; Homberg, J.R. The neurodevelopmental effects of serotonin: A behavioural perspective. Behav. Brain Res. 2015, 277, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, J.; Geier, D.; Audhya, T.; King, P.; Sykes, L.; Geier, M. Evidence of parallels between mercury intoxication and the brain pathology in autism. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2012, 72, 113–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, J.K.; Geier, D.A.; Deth, R.C.; Sykes, L.K.; Hooker, B.S.; Love, J.M.; Bjørklund, G.; Chaigneau, C.G.; Haley, B.E.; Geier, M.R. Systematic Assessment of Research on Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Mercury Reveals Conflicts of Interest and the Need for Transparency in Autism Research. Sci. Eng. Ethic- 2017, 23, 1691–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, J.K.; Geier, D.A.; Sykes, L.K.; Geier, M.R. Relevance of Neuroinflammation and Encephalitis in Autism. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 9, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachadourian, V.; Mahjani, B.; Sandin, S.; Kolevzon, A.; Buxbaum, J.D.; Reichenberg, A.; Janecka, M. Comorbidities in autism spectrum disorder and their etiologies. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.F.; Wang, G. Environmental agents, oxidative stress and autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Gramfort, A.; Shetty, N.R.; Kitzbichler, M.G.; Ganesan, S.; Moran, J.M.; Lee, S.M.; Gabrieli, J.D.E.; Tager-Flusberg, H.B.; Joseph, R.M.; et al. Local and long-range functional connectivity is reduced in concert in autism spectrum disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 3107–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Michmizos, K.; Tommerdahl, M.; Ganesan, S.; Kitzbichler, M.G.; Zetino, M.; Garel, K.-L.A.; Herbert, M.R.; Hämäläinen, M.S.; Kenet, T. Somatosensory cortex functional connectivity abnormalities in autism show opposite trends, depending on direction and spatial scale. Brain 2015, 138, 1394–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrazian, D.; Herbert, M.; Lambert, J. The Relationships between Intestinal Permeability and Target Antibodies for a Spectrum of Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khetrapal, N. The framework for disturbed affective consciousness in autism. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khundakji, Y.; Masri, A.; Khuri-Bulos, N. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis in a toddler. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2018, 5, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.-Y.; Camilleri, M. Serotonin: A Mediator of The Brain–Gut Connection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 95, 2698–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Cho, M.-H.; Shim, W.H.; Kim, J.K.; Jeon, E.-Y.; Kim, D.-H.; Yoon, S.-Y. Deficient autophagy in microglia impairs synaptic pruning and causes social behavioral defects. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 22, 1576–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.H.; Hollander, E.; Sikich, L.; McCracken, J.T.; Scahill, L.; Bregman, J.D.; Donnelly, C.L.; Anagnostou, E.; Dukes, K.; Sullivan, L.; et al. Lack of Efficacy of Citalopram in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders and High Levels of Repetitive Behavior. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissane, D.W. The Relief of Existential Suffering. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 1501–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, B.; Rossmanith, W.G. Hormones and the Endocrine System; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, M.; Romeo, R.; Beecham, J. Economic cost of autism in the UK. Autism 2009, 13, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, G.P. Gender bias in autoimmune diseases: X chromosome inactivation in women with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 286, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuesel, I.; Chicha, L.; Britschgi, M.; Schobel, S.A.; Bodmer, M.; Hellings, J.A.; Toovey, S.; Prinssen, E.P. Maternal immune activation and abnormal brain development across CNS disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.-L.; Lin, C.-K.; Lin, C.-L. Relationship between executive function and autism symptoms in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2024, 147, 104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N.; Takahashi, D.; Takano, S.; Kimura, S.; Hase, K. The Roles of Peyer's Patches and Microfold Cells in the Gut Immune System: Relevance to Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, C.-H.; Lee, S.; Kwak, M.; Kim, B.-S.; Chung, Y. CD8 T-cell subsets: heterogeneity, functions, and therapeutic potential. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 2287–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konteh, F.H. Urban sanitation and health in the developing world: Reminiscing the nineteenth century industrial nations. Heal. Place 2009, 15, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacheva, E.; Gevezova, M.; Maes, M.; Sarafian, V. Mast Cells in Autism Spectrum Disorder—The Enigma to Be Solved? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, R.; Ikegaya, Y. Microglia in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders. Neurosci. Res. 2015, 100, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausová, M.; Braun, D.; Buerki-Thurnherr, T.; Gundacker, C.; Schernhammer, E.; Wisgrill, L.; Warth, B. Understanding the Chemical Exposome During Fetal Development and Early Childhood: A Review. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2023, 63, 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushak, R.I.; Winter, H.S. Gut Microbiota and Gender in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2020, 16, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacivita, E.; Perrone, R.; Margari, L.; Leopoldo, M. Targets for Drug Therapy for Autism Spectrum Disorder: Challenges and Future Directions. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 9114–9141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, D.K.; Maloney, B.; Wang, R.; Sokol, D.K.; Rogers, J.T.; Westmark, C.J. How autism and Alzheimer’s disease are TrAPPed. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 26, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Dhingra, R.; Zhang, Z.; Ball, L.M.; Zylka, M.J.; Lu, K. Toward Elucidating the Human Gut Microbiota–Brain Axis: Molecules, Biochemistry, and Implications for Health and Diseases. Biochemistry 2021, 61, 2806–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, K.S.; Aman, M.G.; Arnold, L.E. Neurochemical correlates of autistic disorder: A review of the literature. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 27, 254–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, K.W.; Hauser, J.; Reissmann, A. Gluten-free and casein-free diets in the therapy of autism. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebow, M., Kuperman, Y., & Chen, A. (2024). Prenatal-induced psychopathologies: All roads lead to microglia. In Stress: Immunology & Inflammation (pp. 199–214). Elsevier.

- Lederberg, J. Infectious History. Science 2000, 288, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Sato, W.; Son, C.-G. Brain-regional characteristics and neuroinflammation in ME/CFS patients from neuroimaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 23, 103484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiter, O.; Walker, T.L. Platelets: The missing link between the blood and brain? Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 183, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, E.E.M.; Campos, M.R.S. Effect of ultra-processed diet on gut microbiota and thus its role in neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients 2020, 71, 110609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerer, L.; Varia, J. A long trip into the universe: Psychedelics and space travel. Front. Space Technol. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesch, K.-P.; Waider, J. Serotonin in the Modulation of Neural Plasticity and Networks: Implications for Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Neuron 2012, 76, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, J.; Miller, J.; Abecassis, M.; Tollerud, D.J.; Ildstad, S.T. Evolving Approaches of Hematopoietic Stem Cell–Based Therapies to Induce Tolerance to Organ Transplants: The Long Road to Tolerance. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 93, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chauhan, A.; Sheikh, A.M.; Patil, S.; Chauhan, V.; Li, X.-M.; Ji, L.; Brown, T.; Malik, M. Elevated immune response in the brain of autistic patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009, 207, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, K.; He, X.; Zhou, J.; Jin, C.; Shen, L.; Gao, Y.; Tian, M.; Zhang, H. Structural, Functional, and Molecular Imaging of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neurosci. Bull. 2021, 37, 1051–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Liu, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, Y. Postmortem Studies of Neuroinflammation in Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systematic Review. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 3424–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilienfeld, S.O.; Marshall, J.; Todd, J.T.; Shane, H.C. The persistence of fad interventions in the face of negative scientific evidence: Facilitated communication for autism as a case example. Evidence-Based Commun. Assess. Interv. 2014, 8, 62–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Pearl, A.M.; Kong, L.; Leslie, D.L.; Murray, M.J. A Profile on Emergency Department Utilization in Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 47, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liang, S.; Zhang, C. NK Cells in Autoimmune Diseases: Protective or Pathogenic? Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-H.; Shi, X.-J.; Fan, F.-C.; Cheng, Y. Peripheral blood neurotrophic factor levels in children with autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleo, A. (2014). Chapter 2 - What Is an Autoantibody? In Y. Shoenfeld, P. L. Meroni, & M. E. Gershwin (Eds.), Autoantibodies (Third Edition) (pp. 13–20). San Diego: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-56378-1.00002-2.

- Lleo, A.; Invernizzi, P.; Gao, B.; Podda, M.; Gershwin, M.E. Definition of human autoimmunity — autoantibodies versus autoimmune disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010, 9, A259–A266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cacho, J.M.; Gallardo, S.; Posada, M.; Aguerri, M.; Calzada, D.; Mayayo, T.; Lahoz, C.; Cárdaba, B. Characterization of Immune Cell Phenotypes in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Investig. Med. 2016, 64, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Varela, S.; González-Gross, M.; Marcos, A. Functional foods and the immune system: a review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, S29–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Shulman, C.; DiLavore, P. Regression and word loss in autistic spectrum disorders. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 936–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, Z. The Impact of Microglia on Neurodevelopment and Brain Function in Autism. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luvián-Morales, J.; Varela-Castillo, F.O.; Flores-Cisneros, L.; Cetina-Pérez, L.; Castro-Eguiluz, D. Functional foods modulating inflammation and metabolism in chronic diseases: a systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 4371–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyster, R.; Richler, J.; Risi, S.; Hsu, W.-L.; Dawson, G.; Bernier, R.; Dunn, M.; Hepburn, S.; Hyman, S.L.; McMahon, W.M.; et al. Early Regression in Social Communication in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A CPEA Study. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2005, 27, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.P.; Ratliff, H.; Abdelwahab, A.; Vohra, M.H.; Kuang, A.; Shatila, M.; Khan, M.A.; Shafi, M.A.; Thomas, A.S.; Philpott, J.; et al. The Safety of Immunosuppressants Used in the Treatment of Immune-Related Adverse Events due to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: a Systematic Review. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 2956–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, A.J.; Pachnis, V.; Prinz, M. Boundaries and integration between microbiota, the nervous system, and immunity. Immunity 2023, 56, 1712–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maenner, M.J. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR. Surveill. Summ. 2021, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.F.; Watkins, L.R. Bidirectional communication between the brain and the immune system: implications for behaviour. Anim. Behav. 1999, 57, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre, L.; Bustamante, M.; Hernández-Ferrer, C.; Thiel, D.; Lau, C.-H.E.; Siskos, A.P.; Vives-Usano, M.; Ruiz-Arenas, C.; Pelegrí-Sisó, D.; Robinson, O.; et al. Multi-omics signatures of the human early life exposome. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallozzi, M.; Bordi, G.; Garo, C.; Caserta, D. The effect of maternal exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals on fetal and neonatal development: A review on the major concerns. Birth Defects Res. Part C: Embryo Today: Rev. 2016, 108, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamuladze, T.; Kipnis, J. Type 2 immunity in the brain and brain borders. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 1290–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manji, H.; Kato, T.; Di Prospero, N.A.; Ness, S.; Beal, M.F.; Krams, M.; Chen, G. Impaired mitochondrial function in psychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, L. , & Fester, R. (1991). Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation: Speciation & Morphogenesis. MIT Press.

- Marotta, R.; Risoleo, M.C.; Messina, G.; Parisi, L.; Carotenuto, M.; Vetri, L.; Roccella, M. The Neurochemistry of Autism. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, R.E.; Marques, P.E.; Guabiraba, R.; Teixeira, M.M. Exploring the Homeostatic and Sensory Roles of the Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 125–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, L., & Born, J. (2002). Brain-Immune interactions in sleep. In International Review of Neurobiology (Vol. 52, pp. 93–131). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7742(02)52007-9.

- Martin, A.; Scahill, L.; Anderson, G.M.; Aman, M.; Arnold, L.E.; McCracken, J.; McDougle, C.J.; Tierney, E.; Chuang, S.; Vitiello, B.; et al. Weight and Leptin Changes Among Risperidone-Treated Youths With Autism: 6-Month Prospective Data. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1125–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cerdeño, V. Dendrite and spine modifications in autism and related neurodevelopmental disorders in patients and animal models. Dev. Neurobiol. 2016, 77, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, A.K.; Leung, N.J.; McMurchy, A.N.; Levings, M.K. TH17 Cells in Autoimmunity and Immunodeficiency: Protective or Pathogenic? Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi, A.; DeMayo, M.M.; Glozier, N.; Guastella, A.J. An Overview of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Heterogeneity and Treatment Options. Neurosci. Bull. 2017, 33, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matcovitch-Natan, O.; Winter, D.R.; Giladi, A.; Aguilar, S.V.; Spinrad, A.; Sarrazin, S.; Ben-Yehuda, H.; David, E.; González, F.Z.; Perrin, P.; et al. Microglia development follows a stepwise program to regulate brain homeostasis. Science 2016, 353, aad8670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, C.; Bosma, A. Immune Regulatory Function of B Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A. Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut–brain communication. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.A.; Nance, K.; Chen, S. The Gut–Brain Axis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.M.; Wright, C.L. Convergence of Sex Differences and the Neuroimmune System in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, C.M.; Furey, B.F.; Child, M.; Sawyer, M.J.; Donohue, S.M. Neonatal sex hormones have `organizational' effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of male rats. Dev. Brain Res. 1998, 105, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, J.T.; Anagnostou, E.; Arango, C.; Dawson, G.; Farchione, T.; Mantua, V.; McPartland, J.; Murphy, D.; Pandina, G.; Veenstra-VanderWeele, J. Drug development for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Progress, challenges, and future directions. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 48, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCruden, A. B., & Stimson, W. H. (1991). Sex Hormones and Immune Function. In R. ADER, D. L. FELTEN, & N. COHEN (Eds.), Psychoneuroimmunology (pp. 475–493). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-043780-1.50021-X.

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Stress, Adaptation, and Disease: Allostasis and Allostatic Load. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 840, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, J.; Ashwood, P. Evidence supporting an altered immune response in ASD. Immunol. Lett. 2015, 163, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megremi, A.S. Is fever a predictive factor in the autism spectrum disorders? Med Hypotheses 2013, 80, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzacappa, A.; Lasica, P.-A.; Gianfagna, F.; Cazas, O.; Hardy, P.; Falissard, B.; Sutter-Dallay, A.-L.; Gressier, F. Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorders According to Period of Prenatal Antidepressant Exposure. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclotte, L.; Van de Wiele, T. Food processing, gut microbiota and the globesity problem. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 1769–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H. , Zhang, J., Kuolee, R., Patel, G., & Chen, W. (2007). Intestinal M cells: The fallible sentinels? World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 13, 1477–86. [CrossRef]

- Mills, E.L.; Kelly, B.; O’Neill, L.A.J. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misquita, A.G.; da Silva, C.N.F.; Souza, D.R.O.; dos Santos, D.N.B.; Brito, I.D.S.M.; Ribeiro, J.D.O.S.; Almeida, J.F.L.; Silva, J.A.G.; Barreto, N.P.M.; Rodrigues, S.C.P.; et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy: A valuable intervention in the autistic universe. Int. Seven- J. Heal. Res. 2024, 3, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsea, E.; Drigas, A.; Skianis, C. Cutting-Edge Technologies in Breathwork for Learning Disabilities in Special Education. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 34, 136–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modafferi, S.; Lupo, G.; Tomasello, M.; Rampulla, F.; Ontario, M.; Scuto, M.; Salinaro, A.T.; Arcidiacono, A.; Anfuso, C.D.; Legmouz, M.; et al. Antioxidants, Hormetic Nutrition, and Autism. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2024, 22, 1156–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, A.M.; Ismail, J.; Nor, N.K. Motor Development in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, C.; Morrow, A.; Meinzenderr, J.; Schleifer, K.; Dienger, K.; Manningcourtney, P.; Altaye, M.; Willskarp, M. Elevated cytokine levels in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Neuroimmunol. 2006, 172, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncrieff, J. Why is it so difficult to stop psychiatric drug treatment? Med Hypotheses 2006, 67, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncrieff, J.; Cohen, D.; Porter, S. The Psychoactive Effects of Psychiatric Medication: The Elephant in the Room. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2013, 45, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Money, J.; Bobrow, N.A.; Clarke, F.C. Autism and autoimmune disease: A family study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1971, 1, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, M.A.; dos Santos, A.A.A.; Gomes, L.M.M.; Rito, R.V.V.F. AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW ABOUT NUTRITIONAL INTERVENTIONS. Rev. Paul. de Pediatr. 2020, 38, e2018262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.L.; Bowers, W.J. Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha and the Roles it Plays in Homeostatic and Degenerative Processes Within the Central Nervous System. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011, 7, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.B.; Weeks, M.E. Proteomics and Systems Biology: Current and Future Applications in the Nutritional Sciences. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2011, 2, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordelt, A.; de Witte, L.D. Microglia-mediated synaptic pruning as a key deficit in neurodevelopmental disorders: Hype or hope? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2023, 79, 102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.T.; Chana, G.; Pardo, C.A.; Achim, C.; Semendeferi, K.; Buckwalter, J.; Courchesne, E.; Everall, I.P. Microglial Activation and Increased Microglial Density Observed in the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Autism. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroncini, G.; Calogera, G.; Benfaremo, D.; Gabrielli, A. Biologics in Inflammatory Immune-mediated Systemic Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2018, 18, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, L.; Bianchi, I.; Lleo, A. Geoepidemiology, gender and autoimmune disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2011, 11, A386–A392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]