1. Introduction

As of now, the articulate discussion mainly pulled in recent years by 6G, sketched sets of diversified services and applications, Key Performance Indicators (KPI), and Key Enabling Technologies (KET), which seem falling well-beyond the next generation of telecommunications itself [

1]. In fact, observing the way other generations (including 5G) evolved, it is like if 6G is going to draw a line between the previous telecommunications-centric networks, and the upcoming services- and applications-centric diversified and distributed infrastructures. Trying to capture most of the forecasted disruption of 6G within a brief narrative is a non-trivial task. A brilliant approach is developed in [

2], where KPI and KET are grouped according to a small number of Paradigm Shifts (PS) that will be triggered by 6G. The four PS, after being re-termed and rearranged in [

3,

4], are graphically set as shown in

Figure 1, and read as follows.

The formation of highly synchronized, low latency and spectrally efficient networks as envisioned for 6G wireless communication is critically dependent on millimetric wave (mmWave), massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO), scattered intelligence (SI), and edge computing elements [

1,

2]. As mmWaves are degraded by atmospheric attenuation and physical obstructions, artificial intelligence (AI) aided signal processing, beamforming, and adaptive antenna techniques are critical for better link reliability.

Most commonly mmWave communications utilize hybrid beamforming, where analog beamforming manages clusters of users with similar channel characteristics, forming a single beam for each cluster. Within these clusters, users are spatially multiplexed via digital beamforming, allowing hybrid beamforming to combine the benefits of both analog and digital beamforming while requiring fewer RF chains. This approach supports the implementation of massive MIMO, which enables the formation of narrow beams. However, these narrow beams increase beam training time and necessitate line-of-sight communication, limiting their application in scenarios with high mobility.

Massive MIMO also enables the creation of arbitrarily shaped beams, which is achieved by designing the phase values of the analog phase shifters. This design process involves selecting an optimal set of phase shift values, referred to as a "codebook," using appropriate algorithms. As the number of antennas in massive MIMO systems increases, the search space for phase shift vectors grows, making exhaustive search algorithms impractical. Various learning-based methods have been proposed for optimal codebook design to achieve these arbitrary beam shapes. Multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) has demonstrated robustness and situational awareness in adaptive codebook design.

1.1. Scattered Intelligence (SI)

This PS hinges around the cornerstone technology of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Since the very early discussion of 6G, the backbone of decentralized data and computation across the network has been stressed as a crucial trend to be addressed [

5,

6]. Further elaboration of such a proposition led to forecasting a massive exploitation of AI at each level of 6G infrastructure, with reference both to the service plane (in continuity with previous generations), and (more disruptively) to the network operation plane [

7,

8].

AI algorithms can, e.g., optimize network operation by addressing problems that involve large amounts of diversified data, including mining, sensing, prediction and reasoning [

9]. Focusing on the user-end, AI can put together the sensing of network traffic variations, of resources utilization, averaged user demands, along with identification of potential threats, optimizing on a real-time basis the functioning of various network entities, like Base Stations (BS) and User Equipment (UE) [

10,

11,

12].

Also, it must be borne in mind that emerging wireless services will evolve into complex systems with varying requirements [

13], and the characteristics of AI and Machine Learning (ML) algorithms can empower self-aware networks. Further ahead, this can lead to developing self-evolutionary features of the network of networks (or system of systems), with the ability, among others, to gather proper resources to ensure local maintenance of KPI (i.e., resilience), while keeping homogeneity with the network as a whole. This implies complex orchestration of the infrastructure [

14] and, on the other hand, distribution of AI at each level of the network, which (re-termed) is Edge Intelligence (EI) [

15].

1.2. Seamless Coverage (SC)

This PS builds around another fundamental proposition of 6G, which is that of ensuring the same KPI, regardless of whether the user (human or machine) is accessing the network from a metropolitan, rural or remote location. Such a remarkable target is driven by the mega-trend towards ubiquity of services, and is already being pursued under 5G through extensive diversification of the physical infrastructure [

16,

17]. This concept is shown schematically in Fig. 1, where the network relies on terrestrial, airborne, space and oversea nodes. A comprehensive report on this topic is available in [

18,

19]. Given such a frame of reference, the topic of Non-Terrestrial Networks (NTN) is being intensively discussed recently [

20], with particular focus on aspects at different levels, arising from integration of satellites within the classical ground infrastructure [

21].

1.3. Spectrum Diversity (SD)

Recalling a few crucial expected KPI of 6G, like breaking the 1 Tbps average data rate per user, scoring End-To-End (E2E) latency below 1 ms, and ensuring E2E reliability of 99.99999 % [

22], it is easy to guess that non-conventional exploitation of the frequency spectrum will be necessary, well beyond what 5G is already pursuing today.

That said, the discussion in [

2] forecasts for 6G an all spectra scenario, leveraging the continuity across sub-6 GHz frequencies, mm-Waves (10-30 GHz), sub-THz (from 30 GHz to 300 GHz), THz range (above 300 GHz), along with optical frequencies, including the visible light spectrum (Visible Light Communications – VLC). Such a variety of spectra gives rise to a plethora of pros and cons that must be carefully and thoroughly evaluated. To this end, comprehensive discussion of various related aspects, ranging from the physics of data transmission at such high frequencies, to key-features as advanced beamforming, and spectrum policy issues, is available in [

23,

24,

25,

26].

1.4. Enhanced Security (ES)

Having in mind the discussion above, it is straightforward that 6G-driven high integration of technologies and ubiquity of services, along with massive exploitation of AI, will raise so many and non-trivial issues in terms of security, privacy and trust of data, that a dedicated PS (ES) is necessary for their counteraction and mitigation [

27,

28,

29].

The growth in sensing functionalities and the prevalence of mobile/wearable devices centered around human-centric services and communications, will prompt security/privacy challenges across multiple fronts. AI itself presents several issues, encompassing data security, AI model and algorithm security, Software (SW) vulnerabilities, and the improper utilization of AI technologies. The training of AI models involves collecting vast amounts of data, likely containing users’ sensitive information, such as identity and location [

2].

The proliferation of miniaturized and wearable IoT devices raises security concerns due to frequent interactions and interconnections, urging for efficient authentication mechanisms and strategies. Traditional encryption/decryption techniques become cumbersome in this context, as they demand computing resources that are often unavailable given the limited computational and storage capability and power availability, typical of IoT devices. Similar considerations apply to Unmanned Air Vehicles (UAV) networks (recalling the PS of SC), prompting the development of lightweight encryption protocols [

30,

31].

Just to list (in no particular order) a few key technologies and strategies that can provide significant contribution in the PS of ES, the following ones are worth to be mentioned: 1) Acting at the Physical Layer Security (PLS) level [

32]; 2) Exploitation of Quantum Technologies (QT), e.g., through Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) [

33,

34]; 3) Blockchain [

35,

36]; 4) Federated Learning (FL) [

37,

38].

1.5. Paper Outline

The paper is organized as follows. After the current

Section 1 that introduced the PS of 6G, the next

Section 2 will first highlight the proliferation and the disruption that will occur in 6G and FN at the network edge, and then will address the issues of edge to cloud continuity. Then,

Section 3 will argue that Micro/Nanotechnologies could address multiple edge requirements in an efficient and effective manner. Further, in

Section 4 we intend to report the design of certain approach with the objective to improve MARL-based codebook design by including federated learning (FL) at the user equipment level, resulting in more accurate and adaptive user clustering. Finally,

Section 5 will collect a few conclusive considerations.

2. General Considerations on Future Network Edge and Integration with the Whole Infrastructure

This section develops some considerations on the future development of the network edge, from the perspective of physical systems. To do so, the features expected for 6G/FN network edge are briefly discussed, at first. Then, the resulting open issue of orchestrating an increasingly more complex edge with the rest of the infrastructure is introduced.

2.1. Proliferation and Disruption at the Edge of the Network

Recalling the discussion developed to this point, it is out of the question that the edge of the network will relentlessly proliferate in the future, driven by application paradigms like the (Super-)IoT and the Tactile Internet (TI), with 6G and FN covering connectivity to the rest of the network (i.e., towards the core) and of the world. This statement comes in with important implications to be addressed. In particular, two considerations should be borne in mind.

The first, in close continuity with what is already ongoing, is that the density of devices connected to the network per square kilometer of 0.1 M/km2 under 4G, is expected to rise to 1 M/km2 with 5G, and to 10 M/km2 when 6G will take over [

39] (see

Figure 2).

The second is linked to the inherent disruption of 6G and FN (as sketched in

Section 1). It has to do with conceiving and designing edge physical systems that implement bio-/nature-inspired concepts, which is way far from how semiconductor-based electronics and telecommunications evolved across the past 5-6 decades. Just to mention a few of these unprecedented characteristics, the following items must be reported:

- (1)

Cognitive-like features, e.g., self-reaction and self-repair intrinsic capacities [

40,

41];

- (2)

Self-management, high resilience and self-evolution of physical systems [

42,

43];

- (3)

Energy autonomy and self-sustenance (zero-energy systems and Energy Harvesting – EH) [

44,

45];

- (4)

Post-digital and non-conventional computing (also termed soft-computing) and Computing In-Memory – CIM systems [

46,

47];

- (5)

Affective Computing (AC) [

48,

49].

Now that the crucial emerging trends of capillarization and disruption of the network edge are addressed, the consequent aspect of integration within the whole infrastructure is going to be addressed.

2.2. Addressing Continuity from the Edge to the Core

Even at shallow glance, making the future network edge work as a whole with the rest of the infrastructure, is not trivial. This is known to the scientific community, and efforts are already being spent to address such a complex issue. The resulting research is not yet aggregated in an established discipline, but it can effectively be termed as Distributed Computing Continuum Systems (DCCS) [

50].

In fact, already today, systems that leverage the Cloud infrastructure along with new computing tiers, like Fog and Edge, are working as a computing continuum [

51]. However, the discussion in [

52] lists a certain number of potential weaknesses, along with boundary conditions, which may yield such classical computing continuum approaches not the best option for the network edge of the future.

First, existing strategies are devoted to solve specific challenges. Moreover, they rely on traditional top-down methods for design and management, deriving from the first Internet-based systems, i.e., with a server and a client, specified by the SW application.

Also, [

52] points out that edge entities may not count on a certain architecture. Therefore, the architecture itself should become a dynamic feature of the systems, triggering the ability of reacting to (unexpected) situations. On the contrary, in the classical approach, the system characteristics are driven by their infrastructure. To this end, a key sentence of [

53] is quoted in [

52], i.e., “a system is complex if its behavior crucially depends on the details of the system”.

Another important statement, reported in [

52] while discussing the novel approach proposed, is that a DCCS addresses all the resources required to enable an application of the computing continuum, this includes also the application itself but just as another component of the system.

In addition, it is argued that in the Cloud a certain system infrastructure can have various characteristics, counting on the available Degrees of Freedom (DoF) in terms of resources to be employed. However, as the infrastructure starts approaching the Edge, the resources are increasingly limited, the DoF narrower, and the infrastructure approaches the use of all its capabilities.

The work in [

52] also covers relevant principles, like that of reactive systems, of equilibrium and of Free Energy Principle (FEP), borrowed from neuroscience, with reference to the brain adaptive behavior [

54].

It must be noted that all the considerations in [

52] mentioned above, refer to systems based on SW and to their management through a novel approach based on Markov chains [

55]. As the focus of this work is that of Micro and Nanotechnologies as potential KET of future network edge physical systems, it seems that no overlaps exist.

In fact, the propositions in [

52] stressed above, despite referred to a different field of research, carry twofold relevance for the discussion at stake here. One the one hand, it is clear that the classical approaches, still in use today, will not be effective to manage the complexity of the future edge.

From a different perspective, collective requirements and constraints are identified, like the need for high resilience, self-management and self-evolution, along with the scarce availability of resources, among which, sophisticated Hardware (HW) items and energy.

3. Micro/Nanotechnologies as a KET of Future Network Edge

After pinpointing the general requirements and possible constraints to the evolution of the future network edge, it is straightforward that reformulation of the classical approaches to the design and development of its physical nodes will be necessary to a certain extent. The resulting landscape of KET, both SW and HW, turns by its nature wide and diversified.

That said, HW technologies for low-complexity physical components, like sensors, actuators and transducers, are at stake here. Micro and Nanotechnologies (MEMS/NEMS), intended as highly-miniaturized devices, systems, along with innovative micro-/nano-materials and electronics [

56,

57,

58,

59], are identified as suitable candidates for meeting (to a large extent) demands and constraints of 6G/FN/Super-IoT physical edge nodes.

The way the potential borne by such technologies is reported here, is rather practical. To this end, one scheme discussed in [

3] is reported in

Figure 3, showing the most relevant demands of 6G/FN network edge nodes, directly and indirectly related to HW technologies.

Each surrounding label in Fig. 3 can be related to its partial or total implementation in physical (HW) miniaturized items manufactured in MEMS/NEMS technologies.

This statement is going to be elaborated more in details below, including examples of research works in literature, when available. In other cases, consolidated research on some specific themes does not exist, already. However, related contributions are sought, as well, and must be intended as preparatory knowledge for further development of the related item(s) listed in

Figure 3.

3.1. Resilient Self-Adapting Operation

The 6G network edge must adjust its operations in real-time to meet local needs and overcome temporary disruptions. This presents significant challenges for HW performance. E.g., low-complexity HW components must independently respond to changing conditions without relying on dedicated HW-SW systems, which are impractical due to complexity, cost, and size constraints. A practical example is in Radio Frequency (RF) channel switching, where current solutions use redundant relays controlled via SW. In contrast, MEMS/NEMS solutions could utilize micro-relays that adapt to RF power levels without the need for dedicated control systems, leveraging physical properties of thin-films, like, e.g., thermal expansion and self-actuation [

60].

3.2. Sensing Functionalities

In response to the previous point, sensing functionalities must be expanded. This involves physical sensors performing various and complementary functions, possibly through redundant duplication of different sensors on the same chip or by utilizing a single HW component in multiple ways. These capabilities can be facilitated by Microtechnologies and Nanotechnologies, also leveraging their substantial inexpensiveness, as discussed in [

61,

62].

3.3. Subsection Actuating Functionalities

Building upon the prior point, actuators must also expand their functions and modes of operation, similar to sensors. Moreover, integrating mixed sensing and actuating capabilities within a single physical device aligns with the evolving requirements of the 6G network edge. The current state of the art in this area remains constrained, despite a few works, like [

63], start stepping along this direction.

3.4. Transduction Functionalities

Transduction between different physical domain is an inherent feature of sensors and actuators. However, devices primarily focused on transduction capabilities, rather than sensing or actuating, are anticipated to be crucial, as well. This includes technologies like RF-MEMS/-NEMS, i.e., Radio Frequency MEMS/NEMS [

64,

65], and EH-MEMS/-NEMS, i.e., MEMS/NEMS for Energy Harvesting [

66,

67], which have been extensively explored in literature. Yet, there remains a gap in hybridizing these technologies to enable a single hardware unit to perform its function while simultaneously harvesting the required energy for operation. A couple of discussions venturing such a direction are elaborated in [

68,

69].

A microphotograph of a physical RF-MEMS complex switching device, manufactured in the technology discussed in [

70], is shown in

Figure 4.

A photo of an entire silicon wafer populated by diverse EH-MEMS design concepts targeting mechanical vibrations, as discussed in [

71], is shown in

Figure 5.

3.5. Miniaturization and Integration

The conduit linking all the previous points, as well as those following, is the relentless need for size reduction of physical devices at the edge, with a parallel increase of functionalities. Said that, Micro and Nanotechnologies trigger ample opportunities for advancing miniaturization, packaging, integration, and the fusion of functions within a single HW unit [

72,

73].

3.6. Energy Availability, Provision and Storage

As previously emphasized, energy management will be pivotal at the 6G edge. Scientific research is advanced in transducer technologies for converting environmental energy (e.g., EH in previous Subsection D), transferring it (e.g., Wireless Power Transfer – WPT [

74]), and storing it (e.g., miniaturized batteries [

75]).

However, there is a need to integrate and align these technologies to achieve the concept of Energy-Aware Distributed Optimization (EADO) [

3,

4]. Despite rich contributions in individual technology branches, there remains a gap in inclusive HW platform solutions that encompass diverse energy converters, optimized extraction and storage, and adaptive operation strategies tailored to real-time power availability. An example is discussed in [

76].

3.7. Evolution of Functions

Building on the earlier Subsection 3.1, the self-adaptation of 6G extends beyond mitigating local challenges. With extensive use of AI, services and functionalities will evolve, potentially incorporating unplanned features. This expanded flexibility cannot solely rely on HW, particularly at the network edge, where extensive HW/SW resources are limited and not fully accessible, as widely discussed in

Section 2.

3.8. Data Transmission/Reception (Tx/Rx) Capacity

In contrast to earlier generations, 6G will bring a disruptive shift from centralized (cloud) to distributed (fog/edge) capabilities (see

Section 2). Yet, this transition does not diminish the importance of data transmission and reception across the network periphery and core. Edge HW infrastructure nodes will require high-performance, versatile and ultra-low-power RF transceivers (transmitters/receivers). MEMS/NEMS solutions are expected to offer significant advantages in providing the necessary RF passive components for such systems (see Subsection 3.4).

3.9. Data Storage

Combining the trends of resource distribution, AI utilization, and self-adaptive operational evolution, alongside the importance of local data storage capacities, the need for miniaturized, ultra-low power consumption, and very-low access latency HW components becomes paramount.

Leveraging existing and emerging Micro and Nano technology-based solutions, like, e.g., [

77,

78,

79], in a synergic way could prove to be crucial in meeting these demands, as emphasized in the subsequent point, too.

3.10. Computational Capacity

In connection with the preceding point and with the discussion in

Section 2, there will be a significant rise in demands for high-efficiency edge computation capacities. Within this context, the two emerging research streams of CIM and of non-conventional computing will exert significant impact. These research areas, although not fully explored, align well with the capabilities offered by Micro/Nano technologies. Examples of investigations along both such directions are discussed in [

80] and [

81], respectively.

4. Federated Reinforcement Learning-Assisted Adaptive Downlink Beamforming Codebook Design for mmWave MIMO

As already mentioned, mmWave communications use hybrid beamforming, where analog beamforming produces a single beam for clusters of users with identical channel characteristics. By spatially multiplexing users within these clusters, digital beamforming allows hybrid beamforming to combine analog and digital benefits with fewer RF links. It supports massive MIMO, which narrows beams. Line-of-sight communication and extended beam training limit narrow beam utilization in high-mobility environments.

Designing analog phase shifter phase values lets huge MIMO produce any beam pattern [

82]. This design method chooses the best phase shift ”codebook”, or set of values, using algorithms. In large MIMO systems with multiple antennas, phase shift vector search space increases, making exhaustive search unfeasible [

83]. Multi-learning-based solutions have been devised for optimal codebook development to acquire any beam morphology. Multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) is robust and situational in adaptive codebook design.

4.1. Common Appproaches of Codebook Design for Hybrid Beamforming in mmWave-Massive MIMO Networks

Generally speaking, codebook design approaches necessitate an initial clustering phase, which frequently depends on offline data collecting and training [

82] or inefficient beam training methods. When dealing with situations that are dynamic, it is vital to re-cluster frequently. It is possible for downlink codebook design algorithms to identify the ideal beam for beamforming by utilizing only uplink channel state information (CSI) and prior codebook entries [

83]. This eliminates the need for consumers to provide any personal information. In light of this, there is a requirement for improved clustering algorithms that are capable of functioning without the direct transfer of user data to the base station. The hybrid beamforming technique is utilized in mmWave communications. In this technique, analog beamforming is utilized to create a single beam for groups of users who share the same channel characteristics. In these clusters, users are spatially multiplexed through the use of digital beamforming, which enables hybrid beamforming to combine the advantages of analog and digital technologies while reducing the number of RF chains. Through the use of this technology, narrow beams are produced, which permits massive MIMO. Narrow beams necessitate communication in a line of sight and longer training sessions, which limits their application in environments with high levels of mobility.

The ability of massive MIMO to generate beams of any shape is made possible by the design of analog phase shifter phase values. For the purpose of selecting an optimal phase shift ”codebook”, or set of values, this design technique requires the utilization of algorithms. It is impossible to use exhaustive search procedures in massive MIMO systems that have a large number of antennas because the phase shift vector search space increases. The generation of ideal codebooks for the purpose of obtaining arbitrary beam morphologies has been accomplished through the development of many learning-based methodologies. Multi-agent reinforcement learning, also known as MRL, is a robust and situational technique that is used in adaptive codebook design.

4.2. FL Assisted Codebook Design for Hybrid Beamforming

As reported by [

84] [

85], FL provides a solution by transferring the model to the data rather than the other way around, which helps to maintain the confidentiality of the account of the user. This makes it possible to make advantage of personal data, such as coarse GPS location, accelerometer, and gyroscope data, in order to enhance beamforming effectiveness while simultaneously protecting the privacy of the user [

86],[

87]. The purpose of this work is to improve the design of MARL-based codebooks by including FL at the user equipment level. This will make it possible to cluster users in a manner that is both more accurate and more customizable. We improve the overall performance of codebook design by training a model at each user device to dynamically assign the user to a suitable cluster. This is accomplished by utilizing data from GPS, acceleration, and orientation for the training of the model.

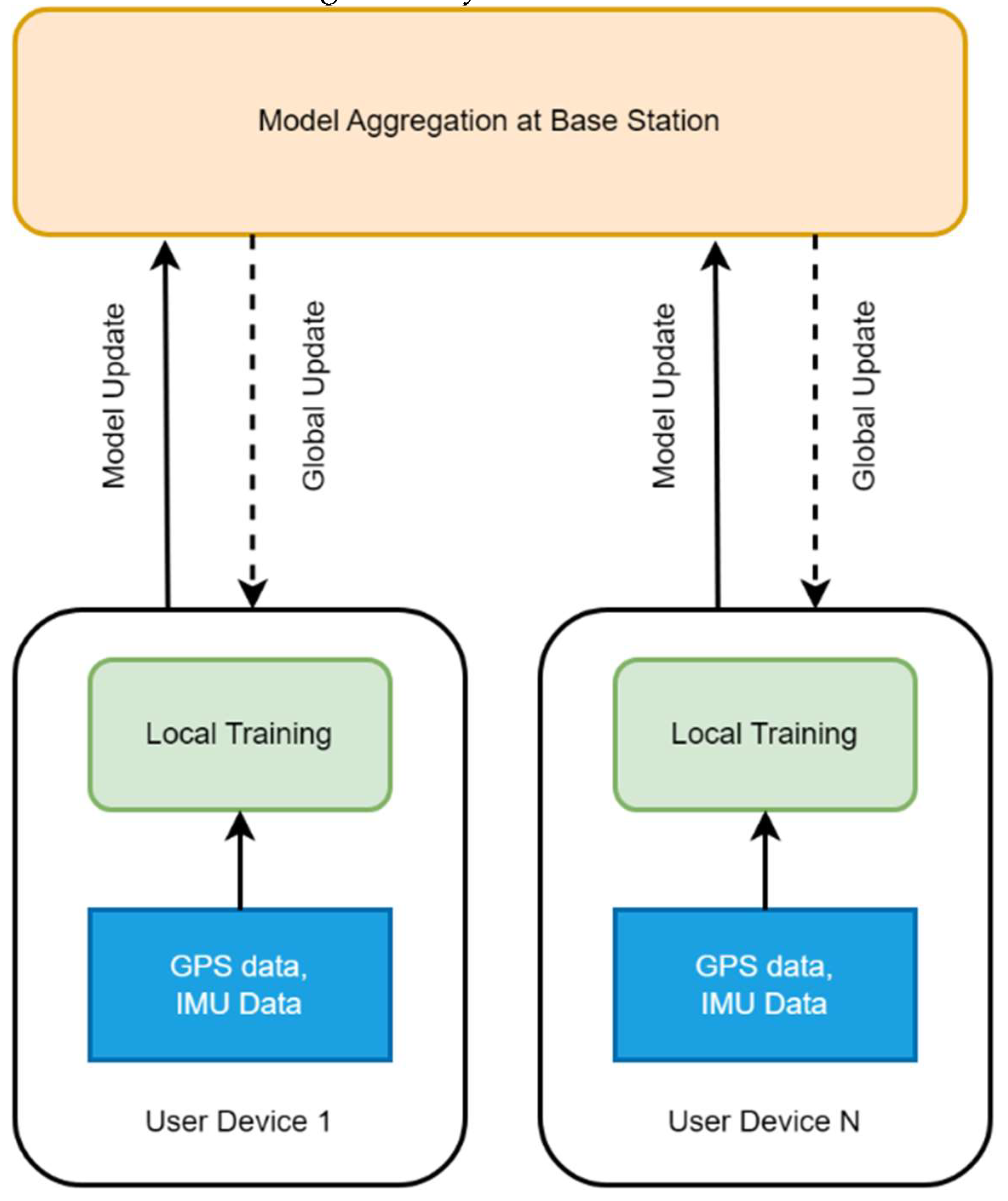

Figure 6 shows a set-up of a horizontal FL server at the base station for identifying cluster at each user devices. It has two components, i.e., a model and a global update. The model update is derived from the aggregate of learning that is recorded at the base station with inputs received from all users. The CSI feed coming from different users help the system to estimate the present state of the channel and share the aggregate update of the model with all the users. Along with CSI, data from a Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) and global positioning system (GPS) unit are used to drive the learning of the system.

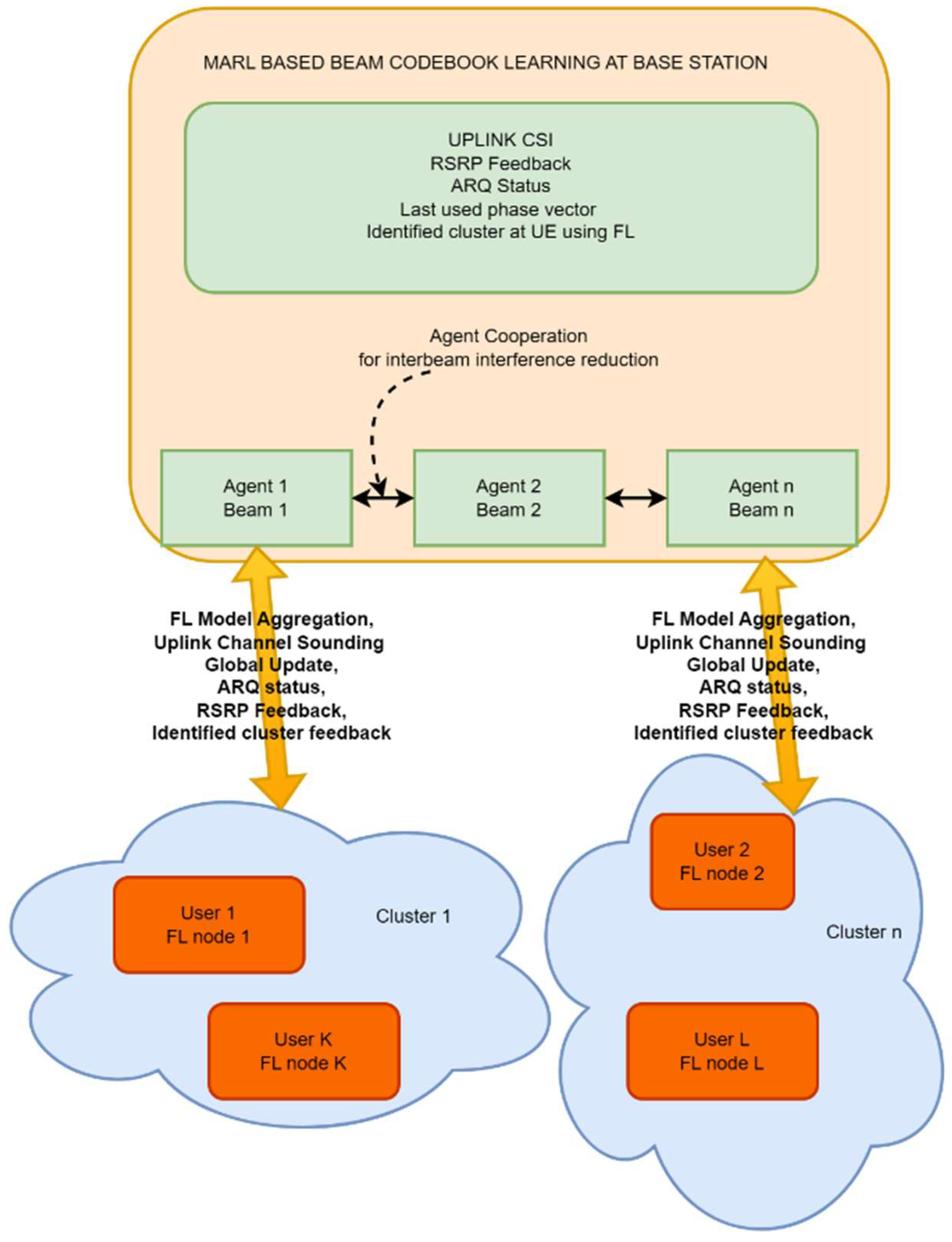

Figure 7 shows the MARL based beam codebook learning that takes place at the base station. Here the uplink CSI, reference signal received power (RSRP) (provides the measure of the wireless link in 4G/5G networks) feedback, automatic repeat request (ARQ) status, last used phase vector and identified cluster at user equipment (UE) level using FL are essential elements for creation of the model aggregation. Further, there is agent level collaboration and cooperation for inter-beam interference reduction. A bi-directional link between the MARL system and the participating nodes share the aggregated FL model, uplink channel sounding, and global update of the learning, ARQ status, RSRP feedback and identified cluster feedback for ascertaining the quality of the process. Identified cluster ID at each UE is fed back to the base station for improved MARL performance. Several such clusters are considered for establishing the effectiveness of the FL based approach.

4.3. Experimental Results

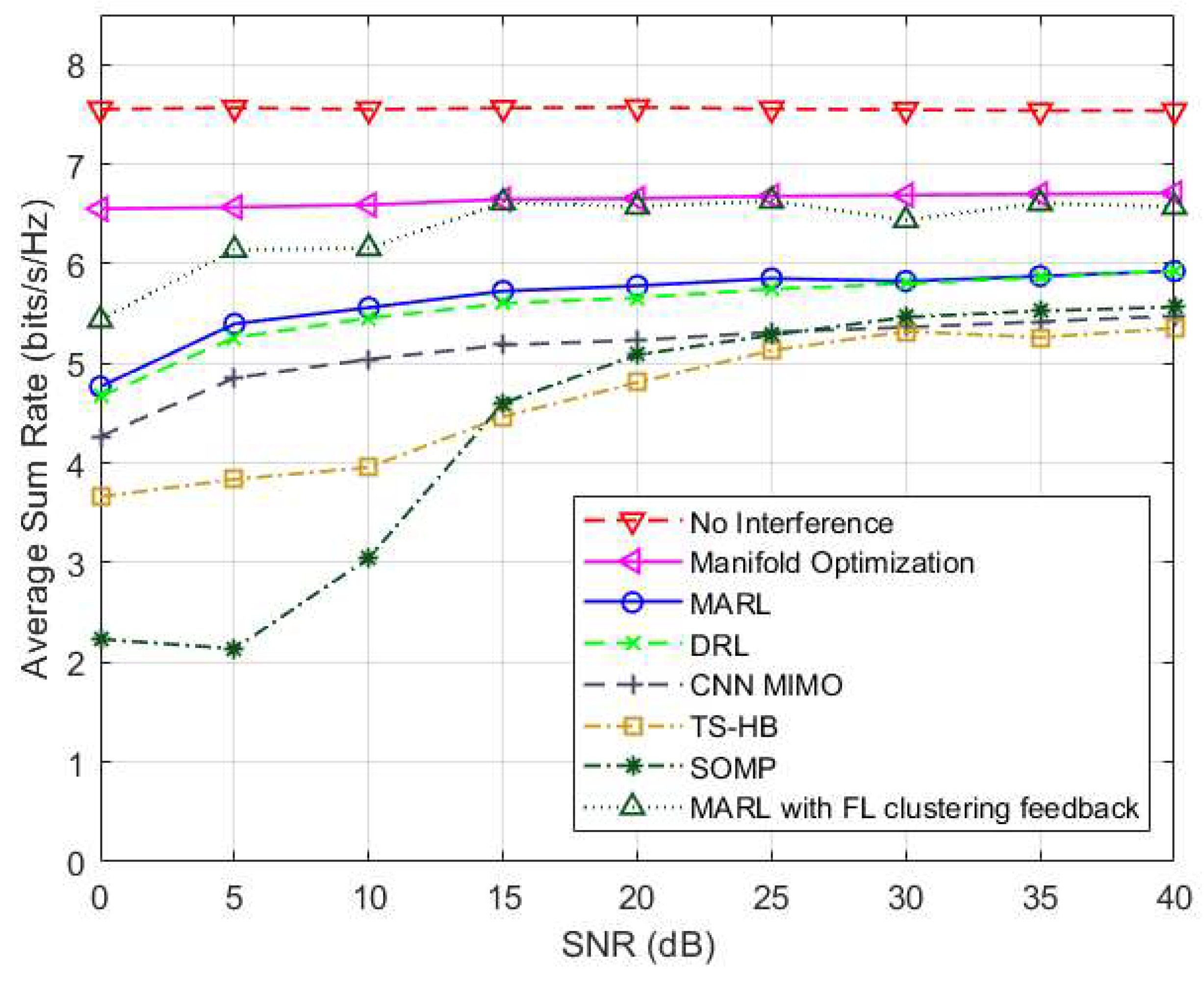

Certain experiments have been carried out for a number of base station (BS) antennas (NBS), number of UE antennas (NM), and number of UEs (M) for certain quantization bits (r) for the analog part of the hybrid beamforming with numbers of BSs and number of clusters considered to be equal.

Figure 8 shows a signal to noise ratio (SNR) vs. sum-rate comparison with noisy measurement of CSI and array response (with NBS = 32, NM = 4, r = 3, M = 4) for different hybrid beamforming techniques with mobile user moving between clusters. The results are compared with those obtained from deep reinforcement learning (DRL) in [

88], manifold optimization (MO) [

89], sparse orthogonal matching pursuit (SOMP) algorithm [

90], convolutional neural network (CNN)-MIMO and the two-stage hybrid beamforming (TS-HB) algorithm [

91].

The results indicate that for mobile users, FL-based user clustering with MARL outperforms traditional initial access-based beam clustering in MARL, as shown in [

88]. This is largely due to the slower nature of traditional beam sweeping and the non-instantaneous cluster handoff when users move from one cluster to another. With coarse GPS and IMU data available at edge devices (mobile devices), each device can identify its own cluster, enabling seamless cluster handoff. This further improves the convergence of MARL for codebook learning by providing accurate feedback. The applicability of the proposed FL-based user clustering is not limited to MARL; it can also be utilized with other non-ML-based beam codebook design techniques, as user clustering is a crucial phase in any hybrid beamforming codebook design approach.

5. Conclusions

Next application and service paradigms of 6G, Future Networks (FN), Super-Internet of Things (IoT) and Tactile Internet (TI), are paving the way for disruption to take place at any level of the network infrastructure. To handle such a huge challenge effectively, a rich and diversified portfolio of Key Enabling Technologies (KET) will be necessary.

Given such premises, this work introduced at first a simplified description of 6G based on macro-areas of disruption, named Paradigm Shifts (PS). Then, a few considerations were reported on the future development of the network edge, from the perspective of physical systems. Subsequently, Micro and Nanotechnologies (MEMS/NEMS), intended as highly-miniaturized devices, systems, along with innovative micro-/nano-materials and electronics, were identified as suitable candidates for meeting (to a large extent) demands and constraints of 6G/FN/Super-IoT physical edge nodes. To this end, numerous examples of already existing research aligned to such a direction were reported.

Then, the work also focused on a practical example of the concepts mentioned before, taking the example of beamforming. Here we have discussed the design and working of a FL driven MARL based robust and situationally aware technique for used in adaptive codebook design for mmWave massive MIMO set-ups as essential ingredients for enhanced link reliability in beyond 5G networks. We showed the effectiveness of such an approach covering base station and mobile users in clusters covered by adaptive antenna selection as part of hybrid beamforming technique.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, J.I. and K. K. S; methodology, J.I., K.K.S, M.B, P.S and A.M; software, M.B, D.D.M.; validation, J.I., K.K.S, M.B., A.M. and K.G; formal analysis, K.K.S, M.B., A.M. and K.G; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, J.I., K.K.S, and M.B.; visualization, J.I. ; supervision, J.I., K.K.S, A.M. and K.G.; project administration, J.I.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created by the study reported in this article.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, C.X.; You, X.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Haas, H.; et al. On the Road to 6G: Visions, Requirements, Key Technologies, and Testbeds. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2023, 25, 905–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Wang, C.X.; Huang, J.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Towards 6G Wireless Communication Networks: Vision, Enabling Technologies, and New Paradigm Shifts. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2021, 64, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannacci, J.; Poor, H.V. Review and Perspectives of Micro/Nano Technologies as Key-Enablers of 6G. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 55428–55458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannacci, J. A Perspective Vision of Micro/Nano Systems and Technologies as Enablers of 6G, Super-IoT, and Tactile Internet. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendan McMahan, H.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Agüera y Arcas, B. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, AISTATS 2017; pp. 20171273–1282.

- Katz, M.; Matinmikko-Blue, M.; Latva-Aho, M. 6Genesis Flagship Program: Building the Bridges Towards 6G-Enabled Wireless Smart Society and Ecosystem. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - 2018 10th IEEE Latin-American Conference on Communications, LATINCOM 2018; 2018; pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liang, Y.C.; Niyato, D. 6G Visions: Mobile Ultra-Broadband, Super Internet-of-Things, and Artificial Intelligence. China Commun. 2019, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letaief, K.B.; Chen, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.J.A. The Roadmap to 6G: AI Empowered Wireless Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2019, 57, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Ding, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Intelligent 5G: When Cellular Networks Meet Artificial Intelligence. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2017, 24, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandi, A. A Review Towards AI Empowered 6G Communication Requirements, Applications, and Technologies in Mobile Edge Computing. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computing, Communication and Multimedia (ICCMC), 2022. p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, A.; Sgouras, G.; Marojevic, V.; Amuru, S.P.; Grace, D. Supporting Intelligence in Disaggregated Open Radio Access Networks: Architectural Principles, AI/ML Workflow, and Use Cases. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 41973–41988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Du, B.; Li, X. AI-Native Network Slicing for 6G Networks. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2022, 29, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, M.G.; Nguyen, K.; Villardi, G.P.; Zhao, O.; Ishizu, K.; Kojima, F. Big Data Analytics, Machine Learning, and Artificial Intelligence in Next-Generation Wireless Networks. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 32328–32338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.A.; Olsson, M.; Razavi, R.; Kadiri, M.; Holmo, R.; Reberg, D. The Architectural Design of Service Management and Orchestration in 6G Communication Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM Workshops, 2023. p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Kitanov, S.; Nikolikj, V. The Role of Edge Artificial Intelligence in 6G Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Information Communication Technologies (ICEST), 2022. p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Boero, L.; Bruschi, R.; Davoli, F.; Marchese, M.; Patrone, F. Satellite Networking Integration in the 5G Ecosystem: Research Trends and Open Challenges. IEEE Netw. 2018, 32, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.A.R.; Hassan, S.A.; Pervaiz, H.; Ni, Q. Drone-Aided Communication as a Key Enabler for 5G and Resilient Public Safety Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P. A Review on 6G for Space-Air-Ground Integrated Network: Key Enablers, Open Challenges, and Future Direction. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Lin, Y.; Li, G.; Xu, W.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Space-Air-Ground Integrated Network (SAGIN) for 6G: Requirements, Architecture, and Challenges. China Commun. 2022, 19, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, M.M.; Billah, M.; Wang, X.; Abbas, R.; Chatzinotas, S.; Driouchi, A.; Xiao, P. Evolution of Non-Terrestrial Networks from 5G to 6G: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 1722–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Hu, X. Evolution to 6G for Satellite NTN Integration: From Networking Perspective. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Network Protocols (ICNP), Reykjavik, Iceland, 2023; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Saad, W.; Bennis, M.; Chen, M. A Vision of 6G Wireless Systems: Applications, Trends, Technologies, and Open Research Problems. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, T.S.; Sones, W.; Sun, S.; Xiao, Q.; Lee, M.; Valaee, S.; Roessler, K. Wireless Communications and Applications Above 100 GHz: Opportunities and Challenges for 6G and Beyond. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 102978–102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, A.; Yang, N.; Han, C.; Jornet, J.M.; Juntti, M.; Kurner, T. Terahertz Communications for 6G and Beyond Wireless Networks: Challenges, Key Advancements, and Opportunities. IEEE Netw. 2023, 37, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jornet, J.M.; Knightly, E.W.; Mittleman, D.M. Wireless Communications Sensing and Security Above 100 GHz. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M.J. 6G Spectrum Policy Issues Above 100 GHz. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2021, 28, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, Y.; Porambage, P.; Liyanage, M.; Ylianttila, M. AI and 6G Security: Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Networks and Communications (EuCNC) & 6G Summit; 2021; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porambage, P.; Gur, G.; Osorio, D.P.M.; Liyanage, M.; Gurtov, A.; Ylianttila, M. The Roadmap to 6G Security and Privacy. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2021, 2, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; He, S.; Su, L.; Bai, J.; Yan, R. Requirements and Potential Key Technologies of Security for 6G Mobile Network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Networking and Network Applications (NaNA), Qingdao, China, 2023; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Shahabuddin, S.; Kumar, T.; Okwuibe, J.; Gurtov, A.; Ylianttila, M. Security for 5G and Beyond. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2019, 21, 3091–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Lin, X.; Shen, X.S. Efficient and Secure Service-Oriented Authentication Supporting Network Slicing for 5G-Enabled IoT. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2018, 36, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammady, S.; Malone, D. A Physical Layer Security (PLS) Approach through Address Fed Mapping Crest Factor Reduction Applicable for 5G/6G Signals. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science (CloudCom), Austin, TX, USA, 2022; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, S.J.; Sharma, S.K.; Wyne, S.; Patwary, M.N.; Asaduzzaman, M. Quantum Machine Learning for 6G Communication Networks: State-of-the-Art and Vision for the Future. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 29095–29111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Banerjee, S. Analysis of Quantum Key Distribution Based Satellite Communication. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (ICCCNT), Bangalore, India, 2018; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.; Feng, G.; Yang, B.; Cao, B.; Imran, M.A. Blockchain-Enabled Wireless Internet of Things: Performance Analysis and Optimal Communication Node Deployment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 5676–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Kawamoto, Y.; Kato, N.; Liu, J. Future Intelligent and Secure Vehicular Network Toward 6G: Machine-Learning Approaches. Proc. IEEE 2020, 108, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Pathirana, P.N.; Ding, M.; Seneviratne, A. Blockchain for 5G and Beyond Networks: A State of the Art Survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2020, 166, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, M.; Wong, K.K.; Poor, H.V.; Cui, S. Federated Learning for 6G: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Engineering 2022, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Connection Density of 4G, 5G, and 6G Mobile Broadband Technologies. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1183690/mobile-broadband-connection-density/. Accessed on: Mar. 11, 2024.

- Ali, S.A.; Hussain, R.; Sethi, P.; Ahmad, A.; Kim, Y. Leveraging Machine Learning for Real-time Anomaly Detection and Self-Repair in IoT Devices. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computational Science and Artificial Intelligence (ICCSAI), Greater Noida, India, 2023; pp. 982–986. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Han, C.; Meng, Y.; Xu, J.; An, T. Embryonics Based Phased Array Antenna Structure with Self-Repair Ability. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 209660–209673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Layzell, P.; Zebulum, R.S. Explorations in Design Space: Unconventional Electronics Design through Artificial Evolution. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1999, 3, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, A.J.; Becker, S.; Schmidt, F.; Thamsen, L.; Kao, O. Towards a Cognitive Compute Continuum: An Architecture for Ad-Hoc Self-Managed Swarms. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM 11th International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science (CloudCom), 2021; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hezekiah, J.D.K.; Singh, A.; Ahmad, M.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, P. Review of Next-Generation Wireless Devices with Self-Energy Harvesting for Sustainability Improvement. Energies 2023, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeek, S.M.; Raja, M.K. Design of an Autonomous IoT Wireless Sensor Node for Industrial Environments. In Proceedings of the 2020 Asia-Pacific Microwave Conference (APMC); 2020; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Manogaran, G.; Gamal, A.; Chang, V. A Novel Intelligent Medical Decision Support Model Based on Soft Computing and IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 5349–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Dey, A.; Wu, X.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Z. Near-Memory Computing: Past, Present, and Future. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2019, 71, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambria, E. Affective Computing and Sentiment Analysis. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2016, 31, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yarosh, S. A Review of Affective Computing Research Based on Function-Component-Representation Framework. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2023, 14, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustdar, S. Distributed Computing Continuum Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (SCC), Barcelona, Spain, 2022; pp. 356–365. [CrossRef]

- Balouek-Thomert, D.; Renart, E.G.; Zamani, A.R.; Simonet, A.; Parashar, M. Towards a Computing Continuum: Enabling Edge-to-Cloud Integration for Data-Driven Workflows. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 2019, 33, 1159–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustdar, S.; Pujol, V.C.; Donta, P.K. On Distributed Computing Continuum Systems. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 1836–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, G. Complex Systems: A Physicist’s Viewpoint. Physica A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 1999, 263, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; Kilner, J.; Harrison, L. A Free Energy Principle for the Brain. J. Physiol. Paris 2006, 100, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.; Peres, Y. Markov Chains and Mixing Times; 2017.

- Gad-el-Hak, M., ed. MEMS – Introduction and Fundamentals, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 1–492.

- Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Issaabadi, Z.; Sajjadi, M.; Sajadi, S. M.; Atarod, M. Chapter 2 - Types of Nanostructures. In An Introduction to Green Nanotechnology, vol. 28, 2019; pp. 25–56.

- Kaushik, B. K. Nanoelectronics: Devices, Circuits and Systems; CRC Press: 2018; pp. 1–300.

- Gogotsi, Y. Nanomaterials Handbook, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: 2017; pp. 1–1200.

- Ni, L.; De Boer, M. P. Self-Actuating Isothermal Nanomechanical Test Platform for Tensile Creep Measurement of Freestanding Thin Films. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2022, 31, pp–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautefeuille, M.; O’Flynn, B.; Peters, F.; O’Mahony, C. Miniaturised Multi-MEMS Sensor Development. Microelectron. Reliab. 2009, 49, pp–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Haneef, I.; Akhtar, S.; Rafiq, M. A.; Ali, S. Z.; Udrea, F. SOI CMOS Multi-Sensors MEMS Chip for Aerospace Applications. In Proc. IEEE Sensors, 2014; vol. 2014-December, pp. 1132–1135. [CrossRef]

- Rabih, A. A. S.; et al. Multi Degrees-of-Freedom Hybrid Piezoelectric-Electrostatic MEMS Actuators Integrated With Displacement Sensors. IEEE JMEMS 2024, 33, pp–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Song, R.; Liu, J.; Yang, J. A Packaged THz Shunt RF MEMS Switch With Low Insertion Loss. IEEE Sensors J. 2021, 21, pp–23829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannacci, J. RF-MEMS Technology as an Enabler of 5G: Low-Loss Ohmic Switch Tested Up to 110 GHz. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 2018, 279, pp–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B.; Kumar, R. A Comparative Simulation Study of the Different Variations of PZT Piezoelectric Material by Using a MEMS Vibration Energy Harvester. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, pp–6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Lee, C.; Feng, H. Design, Fabrication, and Characterization of CMOS MEMS-Based Thermoelectric Power Generators. IEEE JMEMS 2010, 19, pp–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, D. F.; Fu, Y.; Yang, X. Developing Self-Powered High Performance Sensors: Part I - A Tri-Axial Piezoelectric Accelerometer with an Error Compensation Method. In Proc. DTIP, 2018; pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. L.; Sun, Q. Integrated Self-Powered Sensors Based on 2D Material Devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, pp–2208329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomozzi, F.; Mulloni, V.; Colpo, S.; Iannacci, J.; Margesin, B.; Faes, A. A Flexible Fabrication Process for RF MEMS Devices. Rom. J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 14, pp–285. [Google Scholar]

- Iannacci, J.; Sordo, G.; Serra, E.; Schmid, U. The MEMS Four-Leaf Clover Wideband Vibration Energy Harvesting Device: Design Concept and Experimental Verification. Microsyst. Technol. 2016, 22, pp–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. SiP-System in Package Design and Simulation; Wiley: 2017; pp. 1–348. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. High-Density Fan-Out Technology for Advanced SiP and 3D Heterogeneous Integration. In Proc. IEEE RPS, 2018; pp. 4D.1–1–4D.1–4. [CrossRef]

- Xing, N.; Rincón-Mora, G. A. Highest Wireless Power: Inductively Coupled or RF? In Proc. ISQED, 2020; pp. 298–301. [CrossRef]

- Kornyushchenko, A.; Natalich, V.; Shevchenko, S.; Perekrestov, V. Formation of Zn/ZnO and Zn/ZnO/NiO Multilayer Porous Nanosystems for Potential Application as Electrodes in Li-Ion Batteries. In Proc. IEEE NAP, 2020; pp. 01NSSA06–1–01NSSA06–5. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liao, X.; Ji, S.; Zhang, S. A Novel Multi-Source Micro Power Generator for Harvesting Thermal and Optical Energy. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2019, 40, pp–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uranga, A.; et al. Exploitation of Non-Linearities in CMOS-NEMS Electrostatic Resonators for Mechanical Memories. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 2013, 197, pp–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W. W.; et al. NEMS Switch with 30 nm-Thick Beam and 20 nm-Thick Air-Gap for High Density Non-Volatile Memory Applications. Solid State Electron. 2008, 52, pp–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, K.; Park, J.; Shin, C. Theoretical Study of Ferroelectric-Gated Nanoelectromechanical Diode Nonvolatile Memory Cell. Solid State Electron. 2020, 163, pp–107662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.; Hikihara, T. Reprogrammable Logic-Memory Device of a Mechanical Resonator. Int. J. Nonlinear Mech. 2017, 94, pp–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, G.; Mirigliano, M.; Paroli, B.; Milani, P. The Receptron: A Device for the Implementation of Information Processing Systems Based on Complex Nanostructured Systems. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 61, no. SM, pp. 040305. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X., et. al, "Deep Reinforcement Learning for Over-the-Air Federated Learning in SWIPT-Enabled IoT Networks," 2022 IEEE 96th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2022-Fall), London, United Kingdom, 2022, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, A. , et al. "Joint spatial division and multiplexing for mm-wave channels." IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 32.6 (2014): 1239-1255.

- Yue, Z. , et al. "Federated Learning with Non-IID Data." ArXiv, abs/1806.00582 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Tian, Li; et al. "Federated Learning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions." IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 37 (2019): 50-60. [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B. , et al. "Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data." Artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR, 2017.

- Truong, Nguyen, et al. "Privacy preservation in federated learning: An insightful survey from the GDPR perspective." Computers & Security 110 (2021): 102402.

- Zhang, Yet. Al., A. Reinforcement Learning of Beam Codebooks in Millimeter Wave and Terahertz MIMO Systems. IEEE Transactions on Communications. 2022, 70, 904–919. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X et. al.. Alternating Minimization Algorithms for Hybrid Precoding in Millimeter Wave MIMO Systems. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing. 2016, 10, 485–500. [CrossRef]

- Ayach, O.E.; Rajagopal, S.; Abu-Surra, S.; Pi, Z.; Heath, R.W. Spatially Sparse Precoding in Millimeter Wave MIMO Systems. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications. 2014, 13, 1499–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, A.; Leus, G.; Heath, R.W. Limited Feedback Hybrid Precoding for Multi-User Millimeter Wave Systems. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications. 2015, 14, 6481–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).