Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

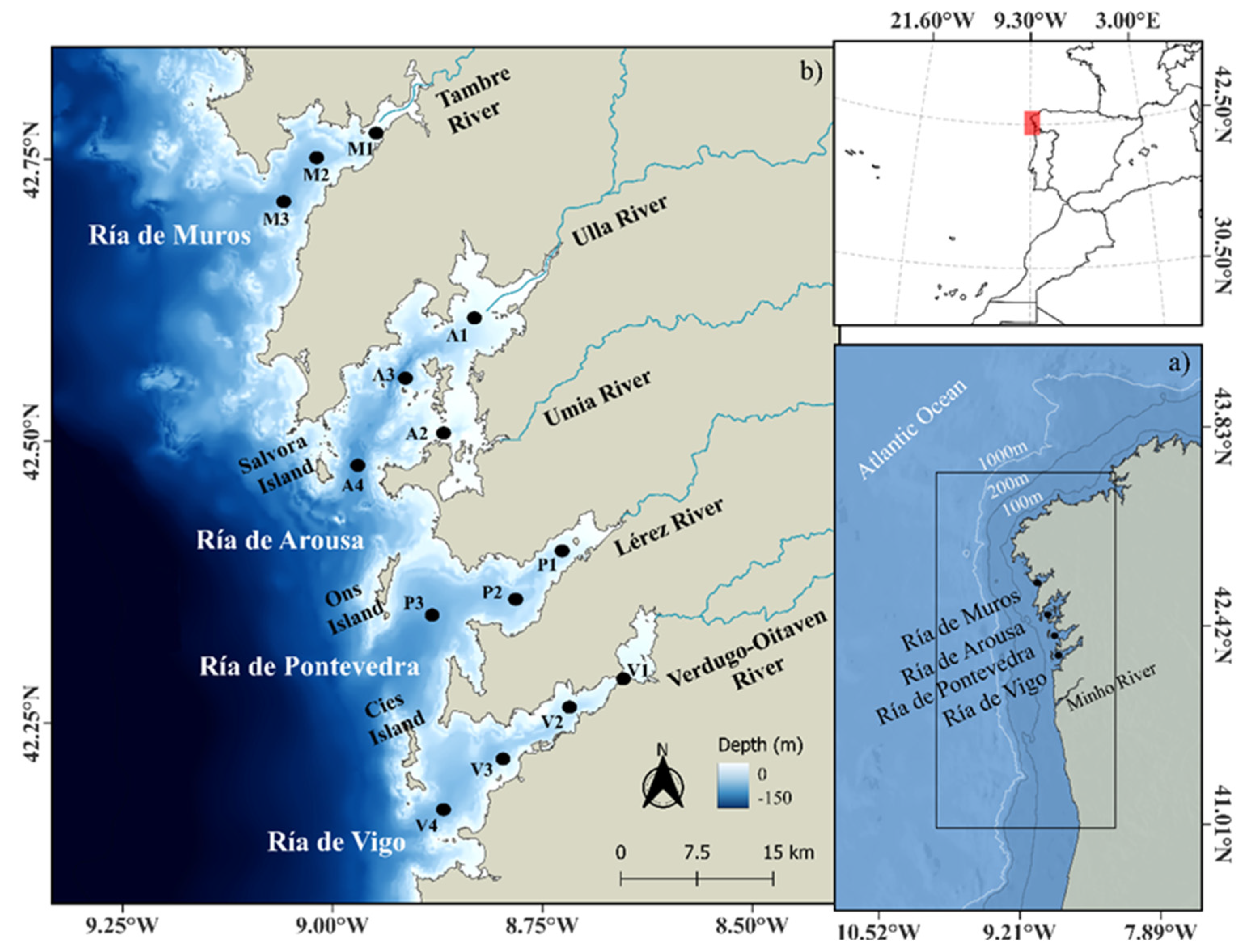

2. Study Area

3. Methodology

3.1. In Situ Data for Model Calibration and Validation

3.2. Numerical Modeling

3.1.1. Hydrodynamic Module

3.1.1. Water Quality module

3.3. Model Calibration

4. Results

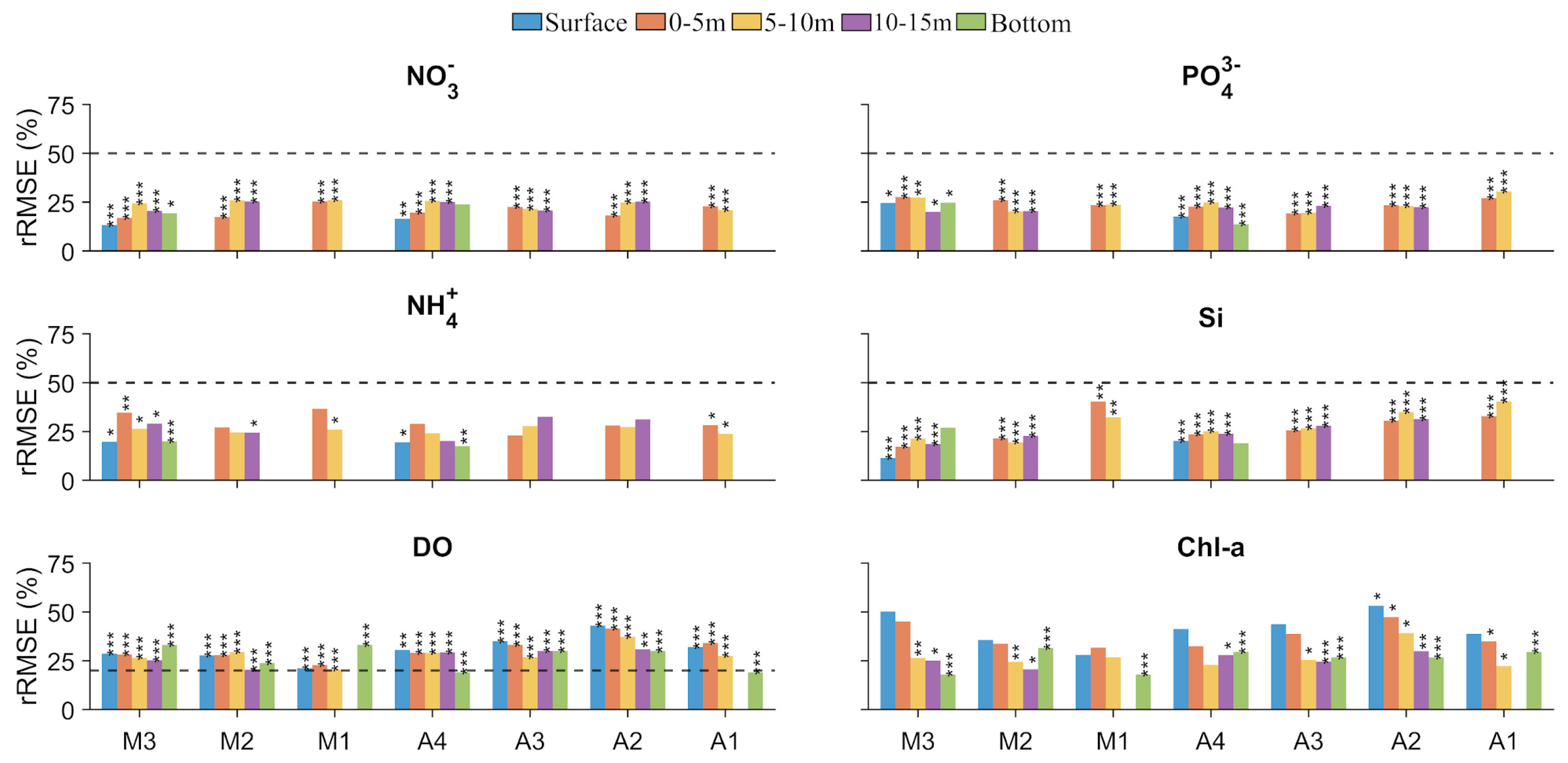

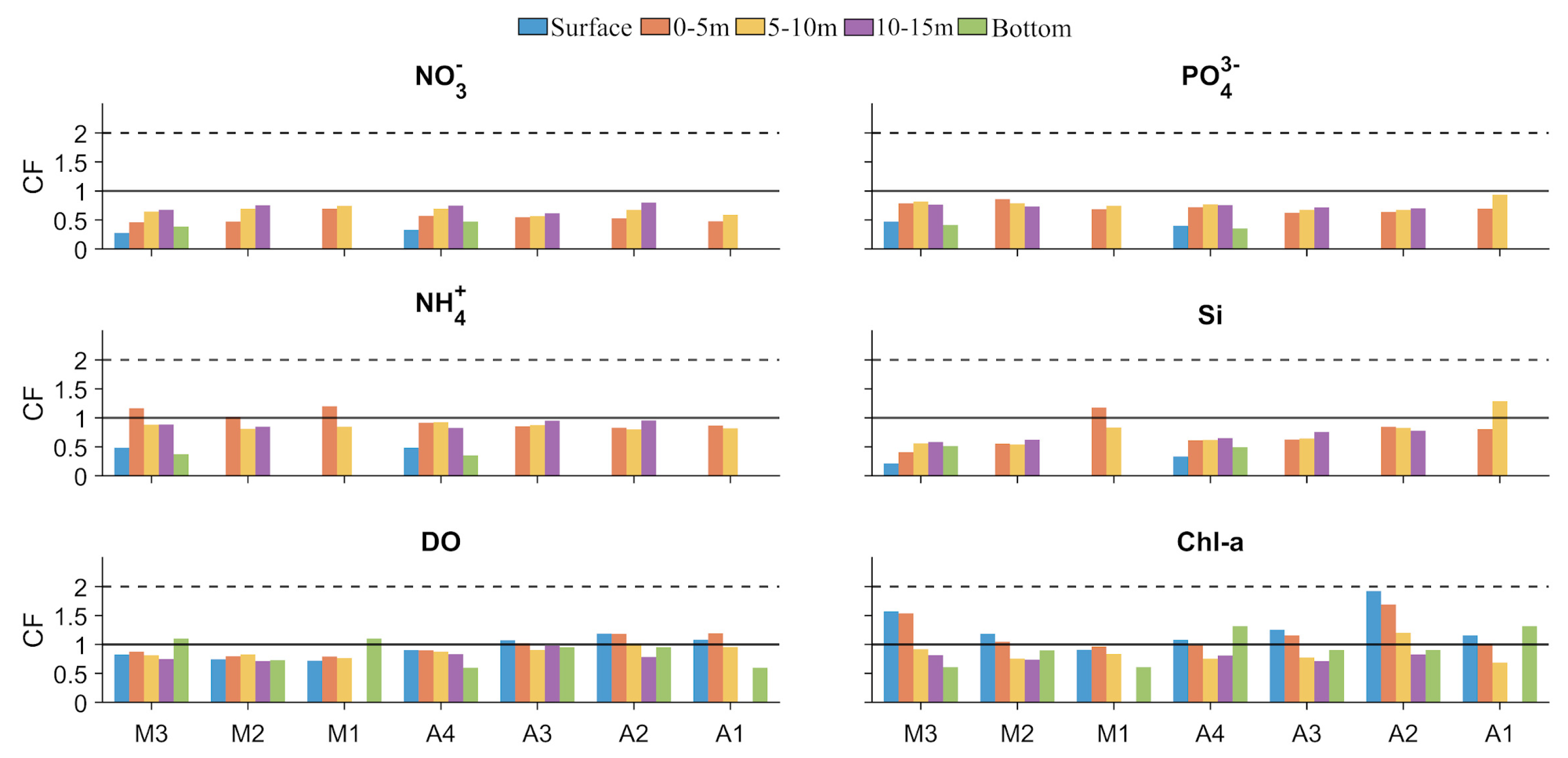

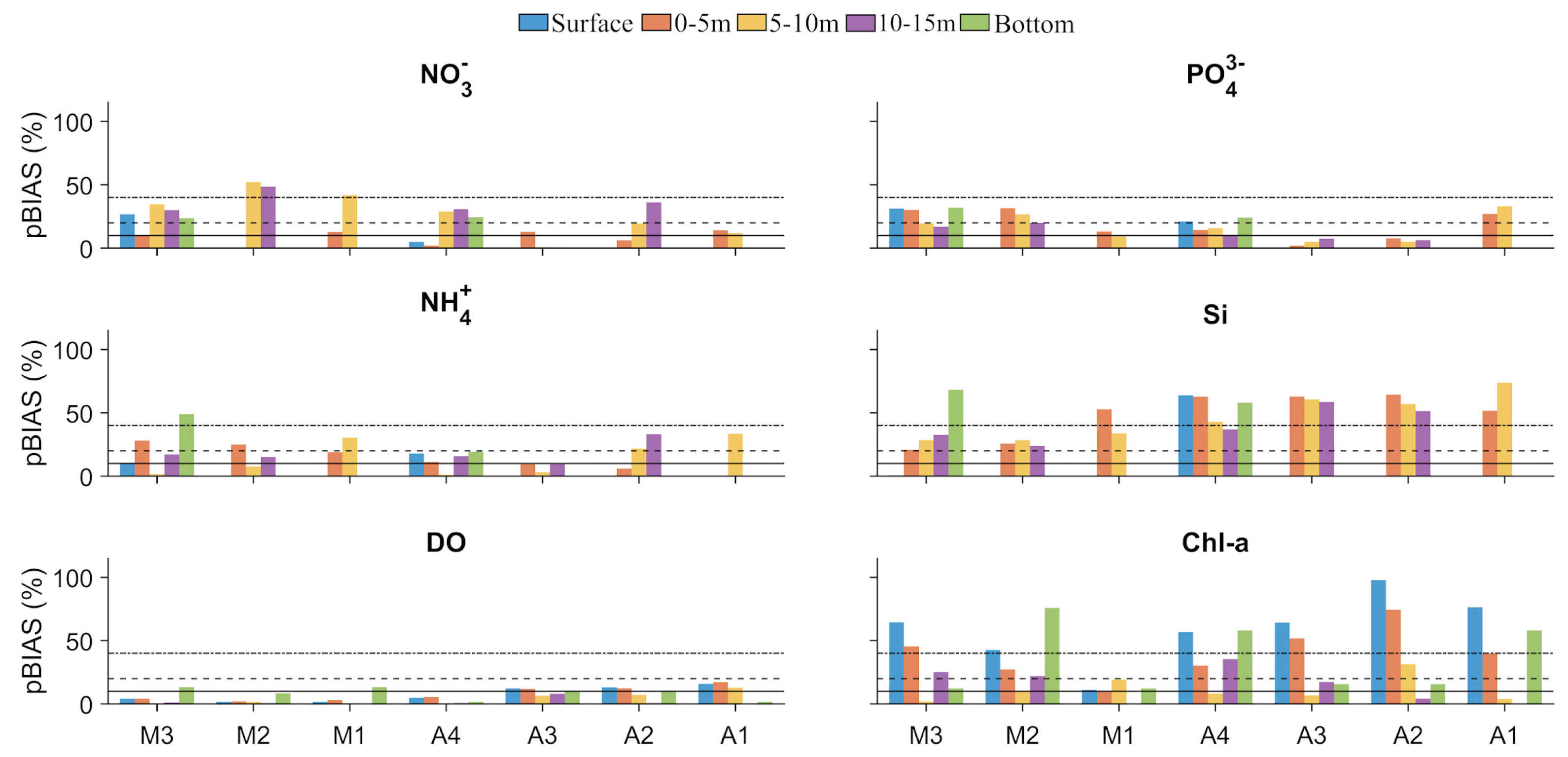

4.1. Model Calibration and Performance

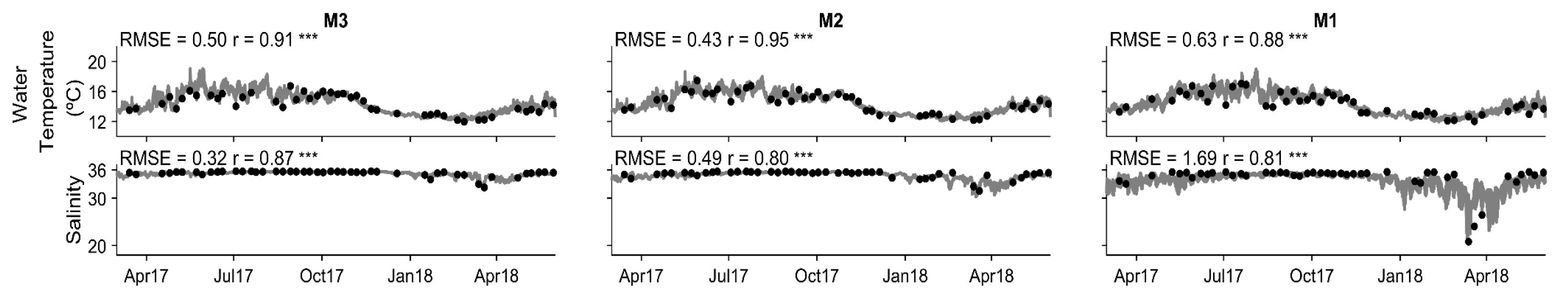

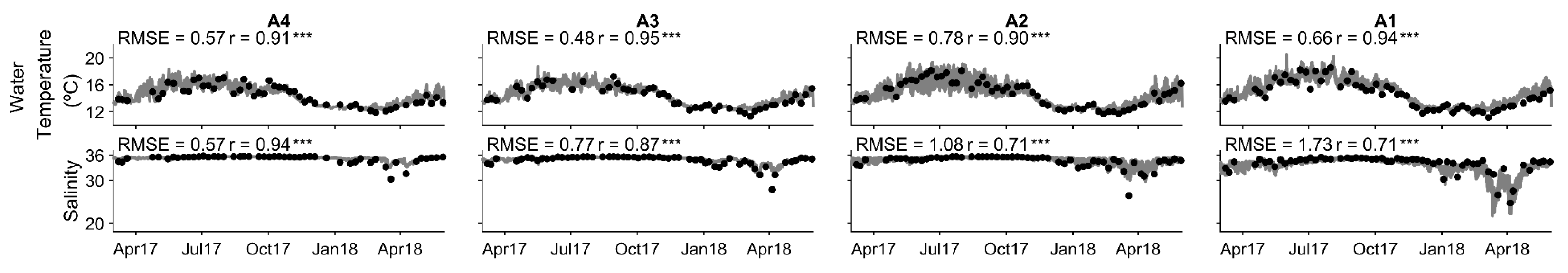

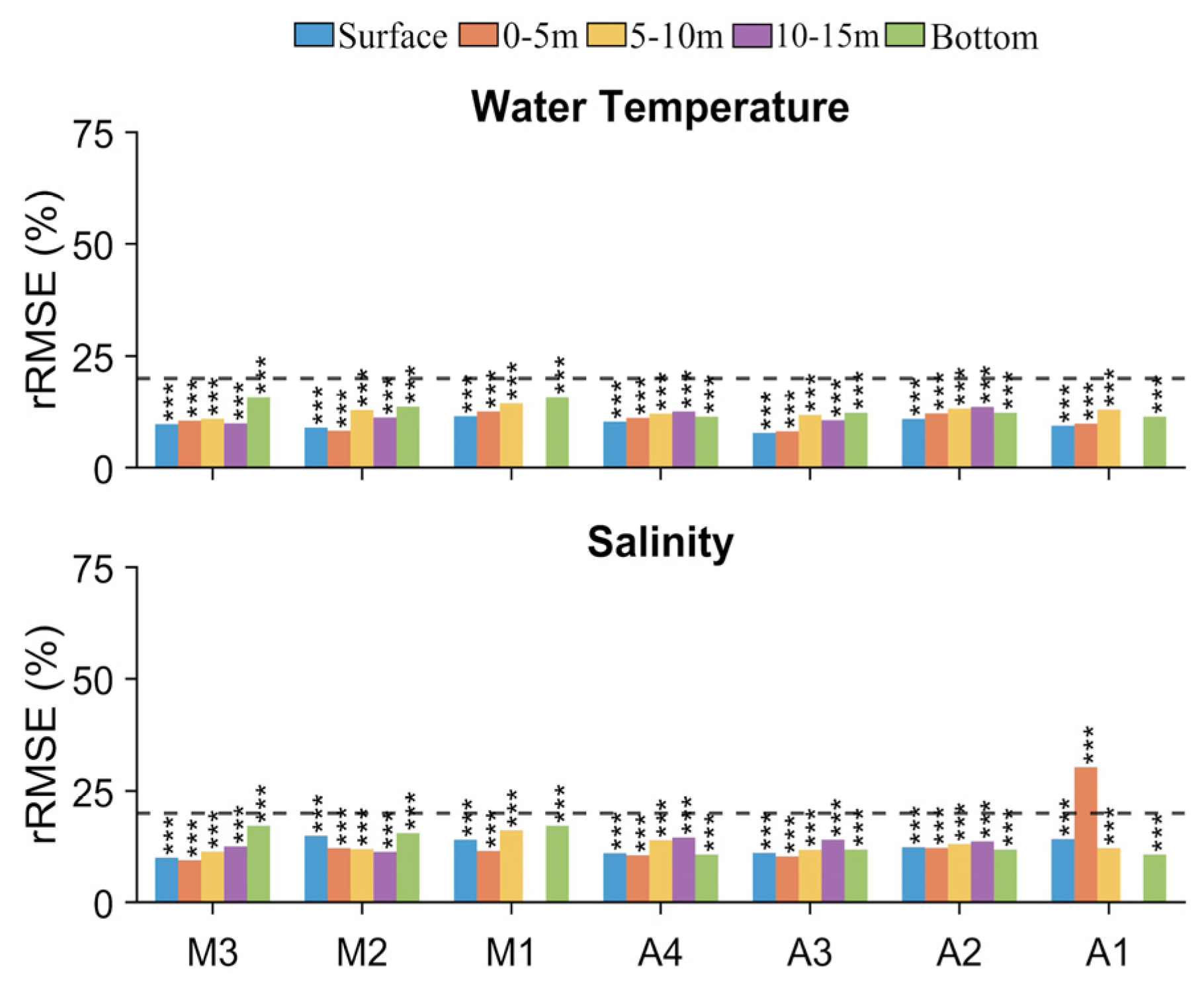

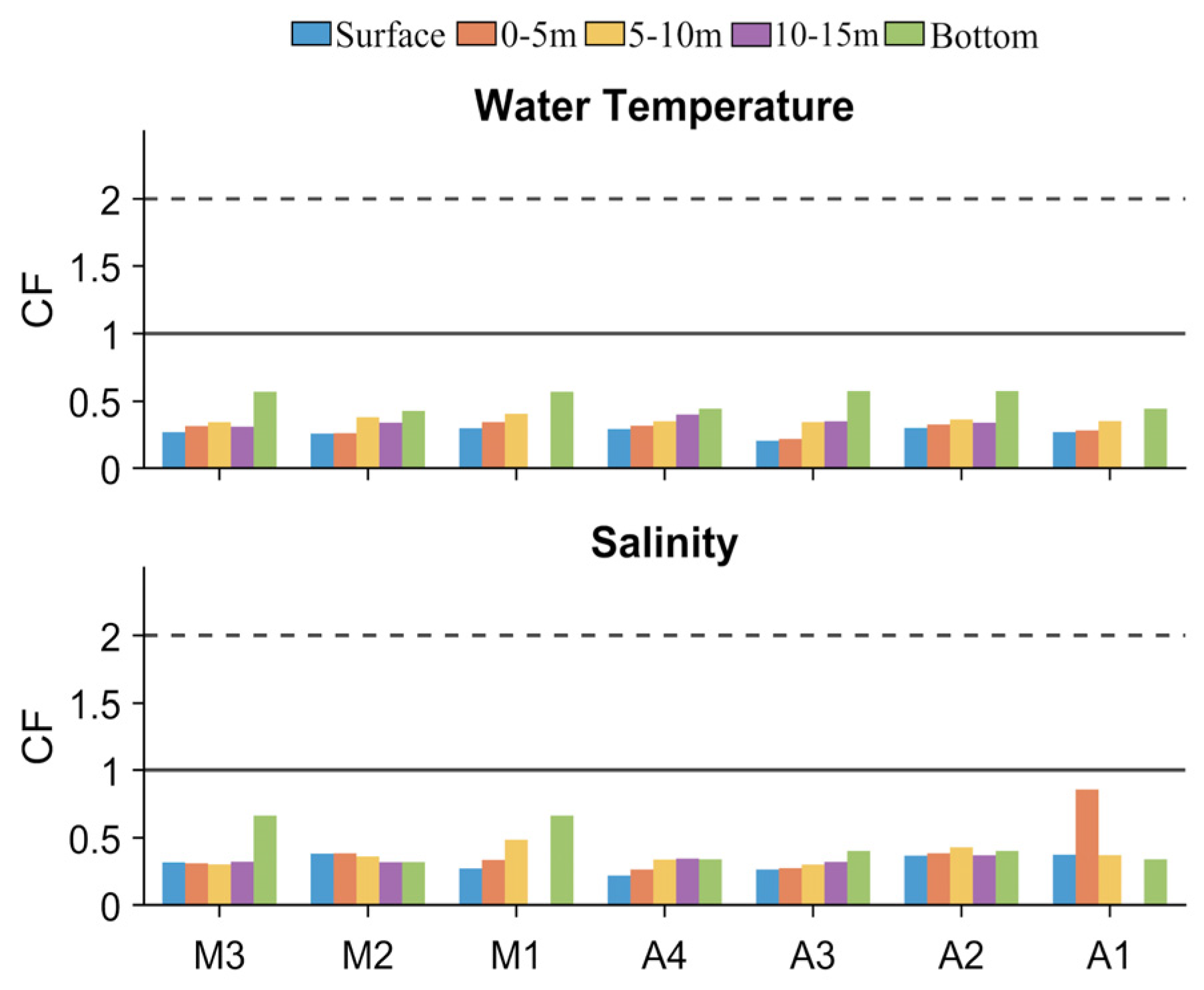

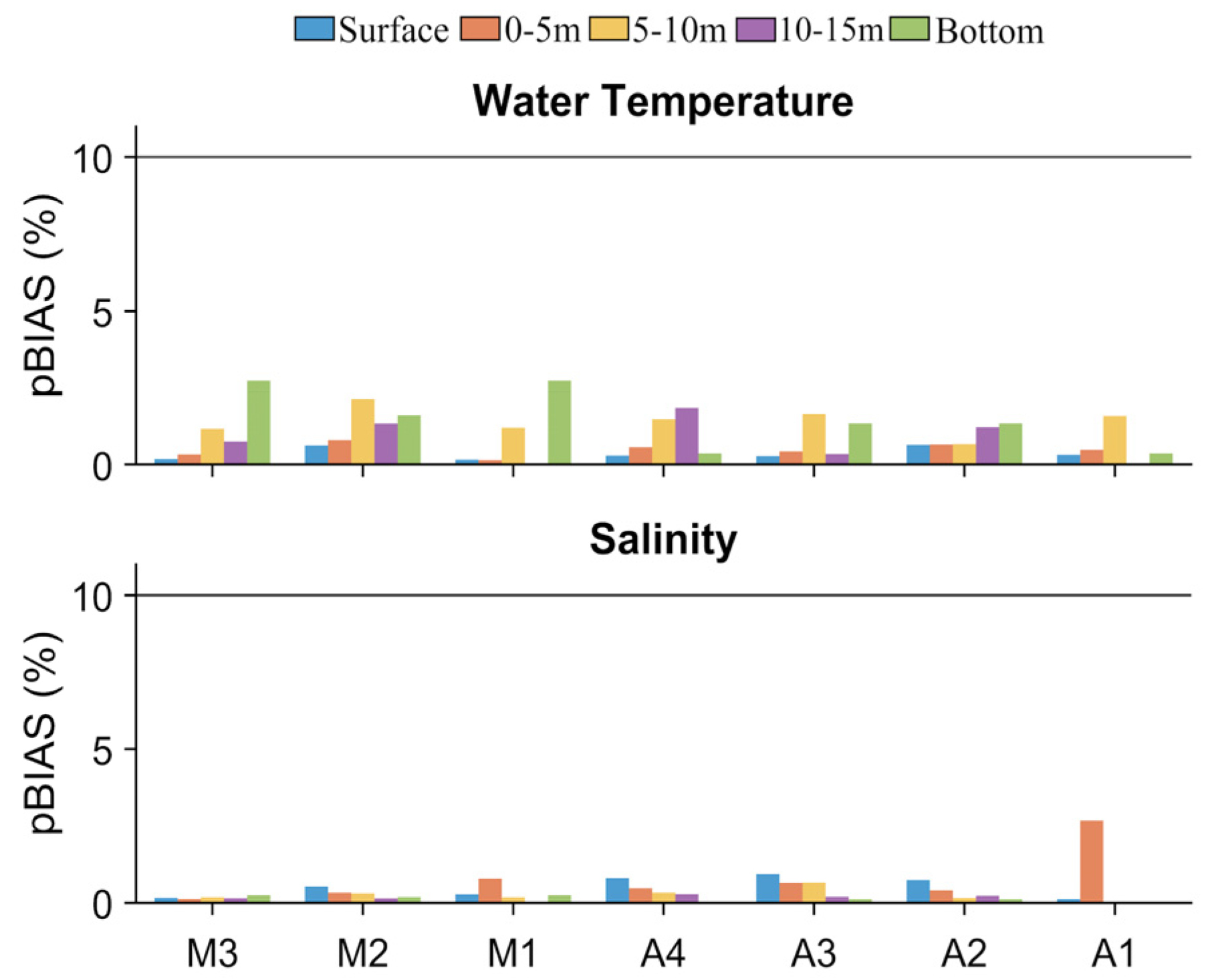

4.1.1. Hydrodynamic

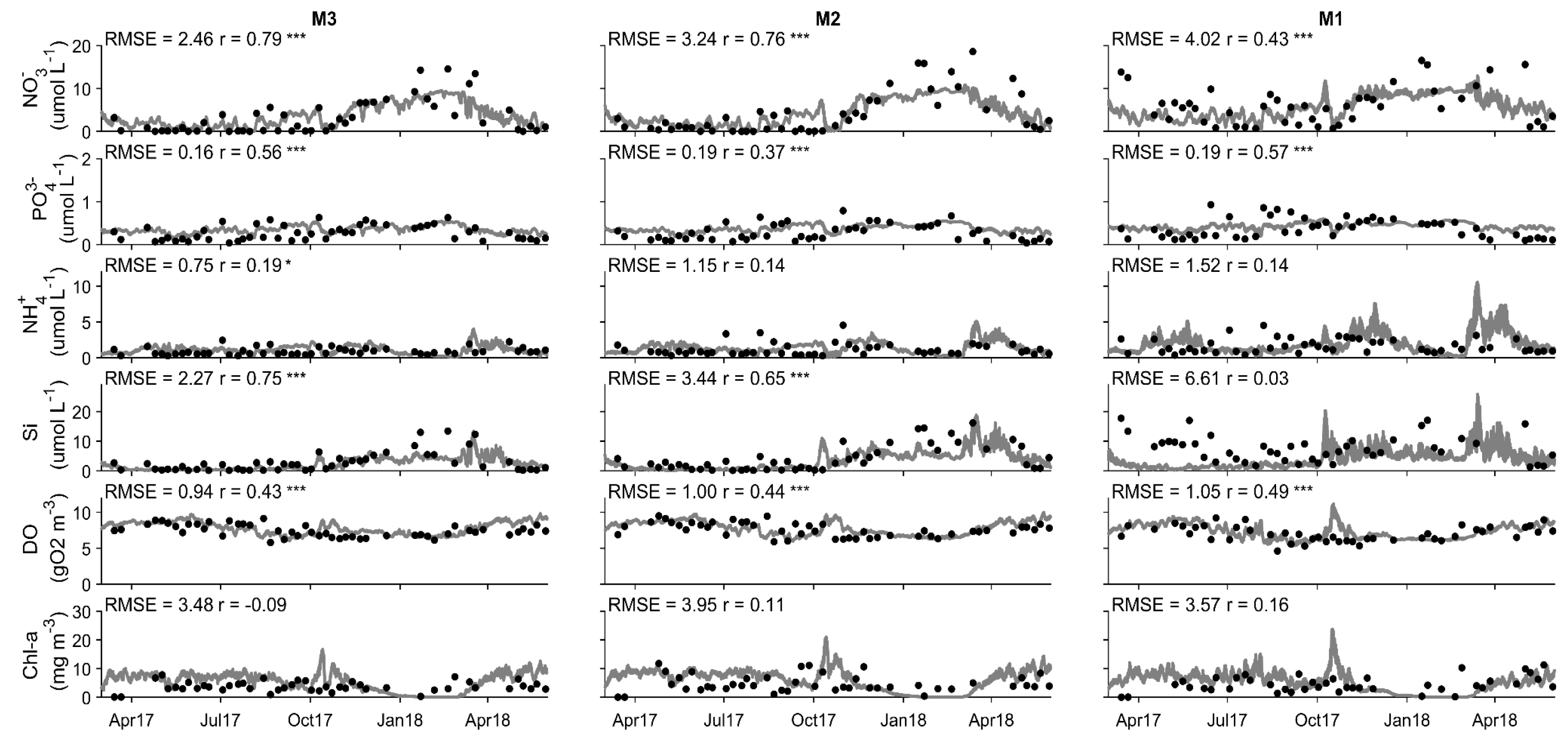

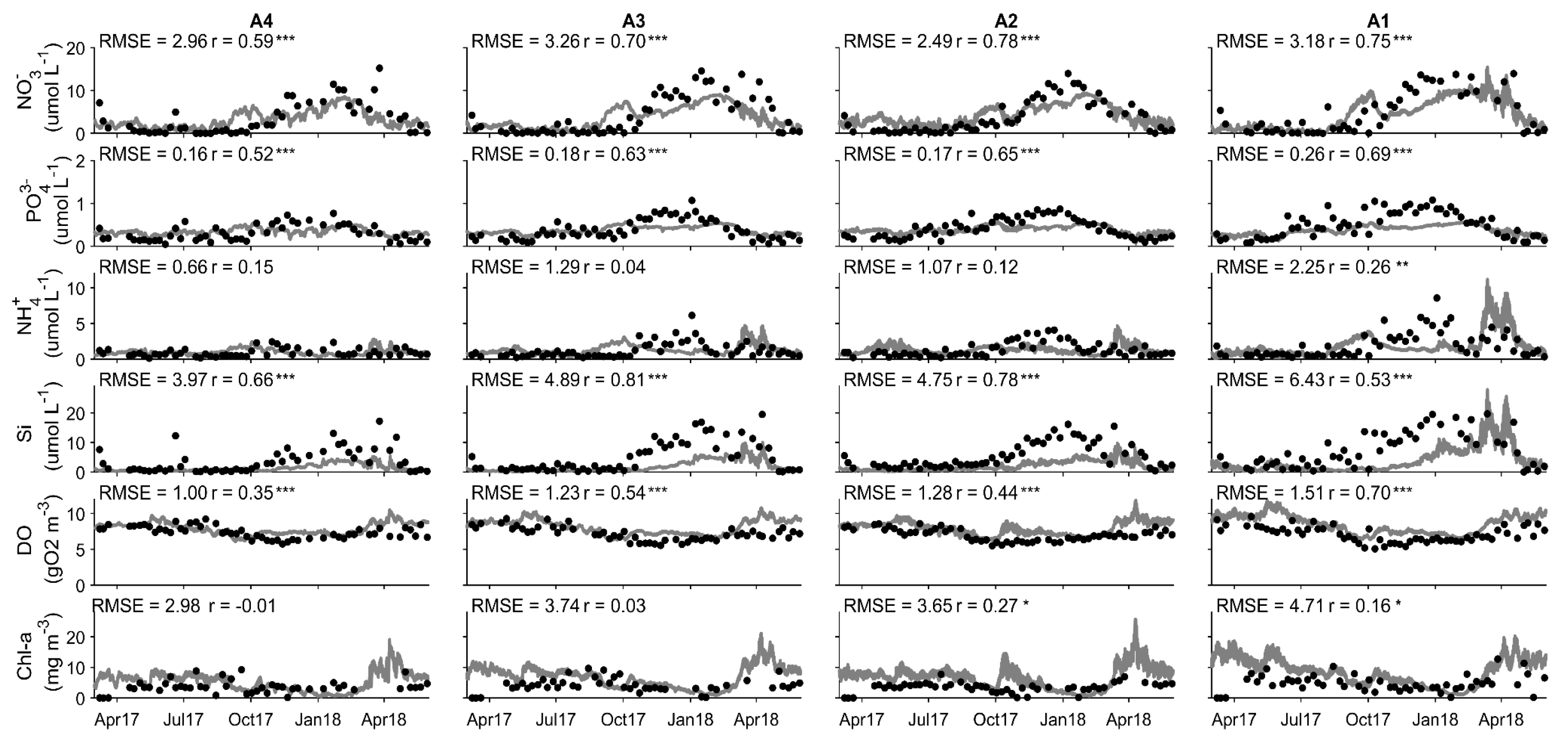

4.2. Water Quality

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kennish, M.J. Environmental threats and environmental future of estuaries. Environ Conserv 2002, 29, 78–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołowicz, M.; Sokołowski, A.; Lasota, R. Estuaries—a biological point of view. Oceanol Hydrobiol Stud 2007, 36, 113–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.B. What was natural in the coastal oceans? Proc Natl Acad Sci 2001, 98, 5411–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloern, J.E.; Abreu, P.C.; Carstensen, J.; Chauvaud, L.; Elmgren, R.; Grall, J.; et al. Human activities and climate variability drive fast-paced change across the world’s estuarine–coastal ecosystems. Global Change Biol 2016, 22, 513–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Alley, R.B.; Berntsen, T.; Bindoff, N.L.; et al. Technical summary. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennerjahn, T.C.; Mitchell, S.B. Pressures, stresses, shocks and trends in estuarine ecosystems–An introduction and synthesis. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 2013, 130, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Poloczanska, E.S. The effect of climate change across ocean regions. Front Mar Sci 2017, 4, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecosystem collapse and climate change; Canadell, J.G., Jackson, R.B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des, M.; Fernández-Nóvoa, D.; DeCastro, M.; Gómez-Gesteira, J.L.; Sousa, M.C.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Modeling salinity drop in estuarine areas under extreme precipitation events within a context of climate change: effect on bivalve mortality in Galician Rías Baixas. Sci Total Environ 2021, 790, 148147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Olivares, A.; Des, M.; Olabarria, C.; DeCastro, M.; Vázquez, E.; Sousa, M.C.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Does global warming threaten small-scale bivalve fisheries in NW Spain? Mar Environ Res 2022, 180, 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Salgado, X.A.; Gago, J.; Míguez, B.M.; Gilcoto, M.; Pérez, F.F. Surface waters of the NW Iberian margin: Upwelling on the shelf versus outwelling of upwelled waters from the Rías Baixas. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 2000, 51, 821–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarta, U.; Fernández-Reiriz, M.J. The Galician mussel industry: Innovation and changes in the last forty years. Ocean Coast Manag 2019, 167, 208–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesca de galicia. Available online: http://www.pescadegalicia.gal (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- FAO. FishStat: Global aquaculture production 1950-2022. 2024. Available online: www.fao.org/fishery/en/statistics/software/fishstatj (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Román, M.; Román, S.; Vázquez, E.; Troncoso, J.; Olabarria, C. Heatwaves during low tide are critical for the physiological performance of intertidal macroalgae under global warming scenarios. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 19530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Des, M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M.; DeCastro, M.; Gómez-Gesteira, L.; Sousa, M.C. How can ocean warming at the NW Iberian Peninsula affect mussel aquaculture? Sci Total Environ 2020, 709, 136117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des, M.; Martínez, B.; DeCastro, M.; Viejo, R.M.; Sousa, M.C.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. The impact of climate change on the geographical distribution of habitat-forming macroalgae in the Rías Baixas. Mar Environ Res 2023, 193, 106884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olabarria, C.; Gestoso, I.; Lima, F. P.; Vázquez, E.; Comeau, L. A.; Gomes, F.; Seabra, R.; Babarro, J. M. F. Response of two mytilids to a heatwave: the complex interplay of physiology, behaviour and ecological interactions. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, R.; Olabarria, C.; Woodin, S. A.; Wethey, D. S.; Peteiro, L. G.; Macho, G.; Vázquez, E. Contrasting responsiveness of four ecologically and economically important bivalves to simulated heat waves. Mar Environ Res. 2021, 164, 105229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, E.; Woodin, S. A.; Wethey, D. S.; Peteiro, L. G.; Olabarria, C. Reproduction under stress: acute effect of low salinities and heat waves on reproductive cycle of four ecologically and commercially important bivalves. Front Mar Sci. 2021, 8, 685282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, M.; Gilbert, F.; Viejo, R. M.; Román, S.; Troncoso, J. S.; Vázquez, E.; Olabarria, C. Are clam-seagrass interactions affected by heatwaves during emersion? Mar Environ Res. 2023, 186, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detoni, A. M. S.; Navarro, G.; Padín, X. A.; Ramirez-Romero, E.; Zoffoli, M. L.; Pazos, Y.; Caballero, I. Potentially toxigenic phytoplankton patterns in the northwestern Iberian Peninsula. Front Mar Sci. 2024, 11, 1330090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, B.; López-Pérez, Á. E.; León, I. Impact of sediment mobilization on trace elements release in Galician Rías (NW Iberian Peninsula): insights into aquaculture. Environ Monit Assess. 2024, 196, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A. M.; Gobler, C. J. Interactive effects of acidification, hypoxia, and thermal stress on growth, respiration, and survival of four North Atlantic bivalves. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2018, 604, 143–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.; Silva, R.; Veloso-Gomes, F.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Potential effects of climate change on northwest Portuguese coastal zones. ICES J Mar Sci. 2009, 66, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, I.; Bio, A.; Melo, W.; Avilez-Valente, P.; Pinho, J.; Cruz, M.; Veloso-Gomes, F. Hydrodynamic model ensembles for climate change projections in estuarine regions. Water. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, L.; Bio, A.; Iglesias, I. The importance of marine observatories and of RAIA in particular. Front Mar Sci. 2016, 3, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Jakeman, A. J.; Vaze, J.; Croke, B. F.; Dutta, D.; Kim, S. J. E. Flood inundation modelling: a review of methods, recent advances and uncertainty analysis. Environ Model Softw. 2017, 90, 201–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, I.; Venâncio, S.; Pinho, J. L.; Avilez-Valente, P.; Vieira, J. M. P. Two models solutions for the Douro estuary: flood risk assessment and breakwater effects. Estuaries Coasts. 2019, 42, 348–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, J.; Bi, X.; Xu, Z.; He, Y.; Gin, K. Y. H. Developing an integrated 3D-hydrodynamic and emerging contaminant model for assessing water quality in a Yangtze Estuary reservoir. Chemosphere. 2017, 188, 218–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ma, W.; Liu, X.; Peng, W.; Zhang, J. Numerical study of hydrodynamics and water quality in Qinhuangdao coastal waters, China: implication for pollutant loadings management. Environ Model Assess. 2021, 26, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Quan, F.; Lu, H.; Zeng, H. Impact of climate change on coastal water quality and its interaction with pollution prevention efforts. J Environ Manag. 2023, 325, 116557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. , Mynett, A.E. Modelling algal blooms in the Dutch coastal waters by integrated numerical and fuzzy cellular automata approaches. Ecol Model. 2006, 199, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troost, T.A.; De Kluijver, A.; Los, F.J. Evaluation of eutrophication variables and thresholds in the Dutch North Sea in a historical context—a model analysis. J Mar Syst. 2014, 134, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, L.; Frankenbach, S.; Serôdio, J.; Dias, J.M. New insights about the primary production dependence on abiotic factors: Ria de Aveiro case study. Ecol Indic. 2019, 106, 105555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picado, A.; Mendes, J.; Ruela, R.; Pinheiro, J.; Dias, J.M. Physico-chemical characterization of two Portuguese coastal systems: Ria de Alvor and Mira estuary. J Mar Sci Eng. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picado, A.; Pereira, H.; Vaz, N.; Dias, J.M. Assessing present and future ecological status of Ria de Aveiro: a modeling study. J Mar Sci Eng. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.; Picado, A.; Sousa, M.C.; Brito, A.C.; Biguino, B.; Carvalho, D.; Dias, J.M. Effects of climate change on aquaculture site selection at a temperate estuarine system. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 888, 164250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, J.J.; Prego, R.; Ruiz-Villarreal, M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M.; Montero, P.; Santos, A.P.; Pérez-Villar, V. Evaluation of the seasonal variations in the residual circulation in the Ría of Vigo (NW Spain) by means of a 3D baroclinic model. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 1998, 47, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R.; Iglesias, G.; Castro, A. Residual circulation in the Ría de Muros (NW Spain): a 3D numerical model study. J Mar Syst. 2009, 75(1-2), 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, G.; Carballo, R. Seasonality of the circulation in the Ría de Muros (NW Spain). J Mar Syst. 2009, 78, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.C.; Vaz, N.; Alvarez, I.; Dias, J.M. Effect of Minho estuarine plume on Rias Baixas: numerical modeling approach. J Coast Res. 2013, (65), 2059–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des, M.; Gómez-Gesteira, J.L.; Decastro, M.; Iglesias, D.; Sousa, M.C.; ElSerafy, G.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Historical and future naturalization of Magallana gigas in the Galician estuaries (NW Spain). Aquaculture. 2023, 569, 739843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego, R. General aspects of carbon biogeochemistry in the ria of Vigo, northwestern Spain. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1993, 57, 2041–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Salgado, X.A.; Rosón, G.; Pérez, F.F.; Figueiras, F.G.; Pazos, Y. Nitrogen cycling in an estuarine upwelling system, the Ria de Arousa (NW Spain). I. Short-time-scale patterns of hydrodynamic and biogeochemical circulation. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1996, 135, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-López, S.; Álvarez-Salgado, X.A.; Varela, R.A. Offshore export versus in situ fractionated mineralization: a 1-D model of the fate of the primary production of the Rías Baixas (Galicia, NW Spain). J Mar Syst. 2005, 54(1-4), 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedracoba, S.; Nieto-Cid, M.; Souto, C.; Gilcoto, M.; Rosón, G.; Álvarez-Salgado, X.A.; Figueiras, F.G. Physical–biological coupling in the coastal upwelling system of the Ría de Vigo (NW Spain). I: In situ approach. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2008, 353, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, L.; Sousa, M.C.; Gómez-Gesteira, M.; Dias, J.M. A habitat suitability model for aquaculture site selection: Ria de Aveiro and Rias Baixas. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, F. Upwelling off the Galician coast, northwest Spain. Coastal Upwelling. 1981, 1, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.; Prego, R. Rias, estuaries and incised valleys: is a ria an estuary? Mar Geol. 2003, 196(3-4), 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gil, S. A natural laboratory for shallow gas: the Rías Baixas (NW Spain). Geo-Mar Lett. 2003, 23, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartelle, V.; García-Moreiras, I.; Martínez-Carreño, N.; Sobrino, C.M.; García-Gil, S. The role of antecedent morphology and changing sediment sources in the postglacial palaeogeographical evolution of an incised valley: The sedimentary record of the Ría de Arousa (NW Iberia). Glob Planet Change. 2022, 208, 103727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas, F.; Bernabeu, A. M.; Méndez, G. Sediment distribution pattern in the Rias Baixas (NW Spain): main facies and hydrodynamic dependence. J Mar Syst 2005, 54(1-4), 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, I.; deCastro, M.; Gomez-Gesteira, M.; Prego, R. Inter- and intra-annual analysis of the salinity and temperature evolution in the Galician Rías Baixas–ocean boundary (northwest Spain). Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2005, 110(C4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Salgado, X. A.; Rosón, G.; Pérez, F. F.; Pazos, Y. Hydrographic variability off the Rías Baixas (NW Spain) during the upwelling season. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 1993, 98, 14447–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gesteira, M.; Moreira, C.; Alvarez, I.; DeCastro, M. Ekman transport along the Galician coast (northwest Spain) calculated from forecasted winds. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2006, 111(C10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finenko, Z. Z. Production in plant populations. Marine Ecology. 1978, 4, 13–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ospina-Álvarez, N.; Prego, R.; Álvarez, I.; DeCastro, M.; Álvarez-Ossorio, M. T.; Pazos, Y.; Varela, M. Oceanographical patterns during a summer upwelling–downwelling event in the Northern Galician Rias: Comparison with the whole Ria system (NW of Iberian Peninsula). Continental Shelf Research. 2010, 30, 1362–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deCastro, M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M.; Alvarez, I.; Prego, R. Negative estuarine circulation in the Ria of Pontevedra (NW Spain). Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2004, 60, 301–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, I.; DeCastro, M.; Gomez-Gesteira, M.; Prego, R. Hydrographic behavior of the Galician Rias Baixas (NW Spain) under the spring intrusion of the Mino River. Journal of Marine Systems. 2006, 60(1-2), 144–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des, M.; deCastro, M.; Sousa, M. C.; Dias, J. M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Hydrodynamics of river plume intrusion into an adjacent estuary: The Minho River and Ria de Vigo. Journal of Marine Systems. 2019, 189, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deCastro, M.; Alvarez, I.; Varela, M.; Prego, R.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Miño River dams discharge on neighbor Galician Rias Baixas (NW Iberian Peninsula): hydrological, chemical and biological changes in water column. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2006, 70, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C. G.; Ríos, A. F. La Ría de Vigo: una aproximación integral al ecosistema marino de la Ría de Vigo, (Biogeoquímica de la Ría de Vigo: ciclo de las sales nutrientes; Trampa/sumidero de CO2), 2008; 85–111.

- Pérez, F. F.; Alvarezsalgado, X.; Rosón, G.; Ríos, A. F. Carbonic-calcium system, nutrients and total organic nitrogen in continental runoff to the Galician Rias Baixas, NW Spain. Oceanologica Acta. 1992, 15, 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Doval, M. D.; López, A.; Madriñán, M. Temporal variation and trends of inorganic nutrients in the coastal upwelling of the NW Spain (Atlantic Galician rías). Journal of Sea Research. 2016, 108, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, E.; Pérez, F. F.; Ríos, A. F. Seasonal patterns and long-term trends in an estuarine upwelling ecosystem (Ría de Vigo, NW Spain). Estuarine, Coastal, and Shelf Science. 1997, 44, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiras, F. G.; Labarta, U.; Reiriz, M. F. Coastal upwelling, primary production and mussel growth in the Rías Baixas of Galicia. In Sustainable Increase of Marine Harvesting: Fundamental Mechanisms and New Concepts: Proceedings of the 1st Maricult Conference held in Trondheim, Norway, 25–28 June 2000; Springer Netherlands, 2002; pp. 121–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, H. P.; Grasshoff, K. Automated chemical analysis. In: Methods of seawater analysis. 1983. p. 347-395.

- INTECMAR. Available online: http://www.intecmar.gal/Ctd/Default.aspx (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Deltares. Available online: https://oss.deltares.nl/web/delft3d (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- GEBCO. Available online: https://www.gebco.net/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Copernicus Marine Data Store. Available online: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- Climate Copernicus. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Meteogalicia. Available online: https://www.meteogalicia.gal (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Confederación Hidrográfica del Miño-Sil. Available online: https://www.chminosil.es/es/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Deltares. D-Water Quality Technical Reference Manual, 5.01 ed.; Deltares, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lønborg, C.; Martínez-García, S.; Teira, E.; Álvarez-Salgado, X. A. Bacterial carbon demand and growth efficiency in a coastal upwelling system. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2011, 63, 183–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Pérez, F.; Castro, C. G. Benthic oxygen and nutrient fluxes in a coastal upwelling system (Ria de Vigo, NW Iberian Peninsula): seasonal trends and regulating factors. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2014, 511, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiras, F. G.; Miranda, A.; Riveiro, I.; Vergara, A. R.; Guisande, C. La Ría de Vigo: una aproximación integral al ecosistema marino de la Ría de Vigo, (El Plancton de la Ría de Vigo). 2008. pp: 111-152.

- McNichol, A. P.; Osborne, E. A.; Gagnon, A. R.; Fry, B.; Jones, G. A. TIC, TOC, DIC, DOC, PIC, POC—unique aspects in the preparation of oceanographic samples for 14C-AMS. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B. 1994, 92(1-4), 162–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munhoven, G. Mathematics of the total alkalinity–pH equation–pathway to robust and universal solution algorithms: the SolveSAPHE package v1.0.1. Geosci Model Dev. 2013, 6, 1367–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijl, F.; Laan, S. C.; Emmanouil, A.; van Kessel, T.; van Zelst, V. T.; Vilmin, L. M.; van Duren, L. A. Potential ecosystem effects of large upscaling of offshore wind in the North Sea. Report 11203731-004-ZKS-0015, Version 1.1, 22 April 2021. p. 96.

- Vieira, L. R.; Guilhermino, L.; Morgado, F. Zooplankton structure and dynamics in two estuaries from the Atlantic coast in relation to multi-stressors exposure. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2015, 167, 347–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, J.; Prego, R. Estimación de los aportes fluviales de nitrato, fosfato y silicato hacia las rías gallegas. 1997.

- Gago, J.; Álvarez-Salgado, X. A.; Nieto-Cid, M.; Brea, S.; Piedracoba, S. Continental inputs of C, N, P and Si species to the Ría de Vigo (NW Spain). Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2005, 65(1-2), 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. I.; Holt, J. T.; Blackford, J.; Proctor, R. Error quantification of a high-resolution coupled hydrodynamic-ecosystem coastal-ocean model: Part 2. Chlorophyll-a, nutrients and SPM. J Mar Syst. 2007, 68(3-4), 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A. C.; Pereira, H.; Picado, A.; Cruz, J.; Cereja, R.; Biguino, B.; Dias, J. M. Increased oyster aquaculture in the Sado Estuary (Portugal): How to ensure ecosystem sustainability? Sci Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçıkoç, M.; Beyhan, M. Hydrodynamic and water quality modeling of Lake Eğirdir. CLEAN–Soil Air Water. 2014, 42, 1573–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSPAR Commission. Report of the modelling workshop on eutrophication issues. 5–8 November 1996. Den Haag, The Netherlands. OSPAR Report.

- Maréchal, D.; Holman, I. P. Comparison of hydrologic simulations using regionalised and catchment-calibrated parameter sets for three catchments in England. 2004.

- Mendes, J.; Ruela, R.; Picado, A.; Pinheiro, J. P.; Ribeiro, A. S.; Pereira, H.; Dias, J. M. Modeling dynamic processes of Mondego estuary and Óbidos lagoon using Delft3D. J Mar Sci Eng. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Zhu, Z.; Ma, J.; Fu, D.; Song, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhao, H. Modeling nutrient flows from land to rivers and seas–A review and synthesis. Mar Environ Res. 2023, 186, 105928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Barral, A.; Teira, E.; Díaz-Alonso, A.; Justel-Díez, M.; Kaal, J.; Fernández, E. Impact of wildfire ash on bacterioplankton abundance and community composition in a coastal embayment (Ría de Vigo, NW Spain). Mar Environ Res. 2024, 194, 106317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs, J. S.; Melack, J. M. Initial impacts of a wildfire on hydrology and suspended sediment and nutrient export in California chaparral watersheds. Hydrol Process. 2013, 27, 3842–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K. D.; Kolden, C. A. Modeling the impacts of wildfire on runoff and pollutant transport from coastal watersheds to the nearshore environment. J Environ Manag. 2015, 151, 113–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, I. G.; Arbones, B.; Froján, M.; Nieto-Cid, M.; Álvarez-Salgado, X. A.; Castro, C. G.; Figueiras, F. G. Response of phytoplankton to enhanced atmospheric and riverine nutrient inputs in a coastal upwelling embayment. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2018, 210, 132–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Harvey, E.; Baetge, N.; McNair, H.; Arrington, E.; Stubbins, A. Investigating atmospheric inputs of dissolved black carbon to the Santa Barbara Channel during the Thomas Fire (California, USA). J Geophys Res Biogeosciences. 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, R.; Durán, M.; Saiz, F. El fitoplancton de la ría de Vigo de enero de 1953 a marzo de 1954. 1955.

- Cermeño, P.; Marañón, E.; Rodríguez, J.; Fernández, E. Large-sized phytoplankton sustain higher carbon-specific photosynthesis than smaller cells in a coastal eutrophic ecosystem. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2005, 297, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermeño, P.; Marañón, E.; Pérez, V.; Serret, P.; Fernández, E.; Castro, C. G. Phytoplankton size structure and primary production in a highly dynamic coastal ecosystem (Ría de Vigo, NW-Spain): seasonal and short-time scale variability. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2006, 67, 251–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina-Álvarez, N.; Varela, M.; Doval, M. D.; Gómez-Gesteira, M.; Cervantes-Duarte, R.; Prego, R. Outside the paradigm of upwelling rias in NW Iberian Peninsula: Biogeochemical and phytoplankton patterns of a non-upwelling ria. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2014, 138, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comesaña, A.; Fernández-Castro, B.; Chouciño, P.; Fernández, E.; Fuentes-Lema, A.; Gilcoto, M.; Mouriño-Carballido, B. Mixing and phytoplankton growth in an upwelling system. Front Mar Sci. 2021, 8, 712342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droop, M. R. The nutrient status of algal cells in continuous culture. J Mar Biol Assoc UK. 1974, 54, 825–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T. C.; Boynton, W.; Horton, T.; Stevenson, C. Nutrient loadings to surface waters: Chesapeake Bay case study. Keeping pace with science and engineering 1993, 8, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Broullón, E.; Franks, P. J.; Fernández Castro, B.; Gilcoto, M.; Fuentes-Lema, A.; Pérez-Lorenzo, M.; Mouriño-Carballido, B. Rapid phytoplankton response to wind forcing influences productivity in upwelling bays. Limnol Oceanogr Lett. 2023, 8(3), 529–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, M. D. L.; Pérez, F. F.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, M.; Bode, A. Seasonal ventilation controls nitrous oxide emission in the NW Iberian upwelling. Prog Oceanogr. 2024, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M. C.; Vaz, N.; Alvarez, I.; Gomez-Gesteira, M.; Dias, J. M. Modeling the Minho River plume intrusion into the rías Baixas (NW Iberian Peninsula). Cont Shelf Res. 2014, 85, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerralbo, P.; Grifoll, M.; Espino, M.; López, J. Predictability of currents on a mesotidal estuary (Ría de Vigo, NW Iberia). Ocean Dyn. 2013, 63, 131–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Hu, K.; La Peyre, M. K. A modeling study of the impacts of Mississippi River diversion and sea-level rise on water quality of a deltaic estuary. Estuaries Coasts. 2017, 40, 1028–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, L. Optimization of Estuarine Aquaculture Exploitation: Modelling Approach. PhD thesis, University of Aveiro, 2020; p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Arhonditsis, G. B.; Brett, M. T. Evaluation of the current state of mechanistic aquatic biogeochemical modeling. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004, 271, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DSLLC. Dynamic Solutions LLC, 3-Dimensional Hydrodynamic and Water Quality Model of Lake Thunderbird, Oklahoma EFDC Water Quality Model Setup, Calibration and Load Allocation Tasks 1A, 1B, 1C and 1D (Draft). Technical Report Prepared by Dynamic Solutions, Knoxville, TN for Oklahoma Department Environmental Quality, Water Quality Division, Oklahoma City, OK; 2012.

- Dumbauld, B. R.; Ruesink, J. L.; Rumrill, S. S. The ecological role of bivalve shellfish aquaculture in the estuarine environment: a review with application to oyster and clam culture in West Coast (USA) estuaries. Aquaculture. 2009, 290(3‐4), 196–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. G.; Corner, R. A.; Moore, H.; Bricker, S. B.; Rheault, R. Ecological carrying capacity for shellfish aquaculture—sustainability of naturally occurring filter-feeders and cultivated bivalves. J Shellfish Res. 2018, 37, 709–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ría | Water Volume (km3) |

Surface Area (km3) |

Length (km) |

Mean Mouth Depth (m) |

Main River(s) | Mean River Flow (m3 s-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vigo | 3.1 | 176 | 31 | southern 50 | Verdugo-Oitaven | 17 |

| northern 25 | ||||||

| Pontevedra | 3.5 | 141 | 22 | southern 60 | Lérez | 25.6 |

| northern 15 | ||||||

| Arousa | 4.5 | 230 | 25 | southern 55 | Ulla | 79.3 |

| northern 5 | Umia | 16.3 | ||||

| Muros | 2.1 | 125 | 13 | 50 | Tambre | 54.1 |

| Parameter | Description [units] | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Temp | ambient water temperature [ºC] | Delft3D-FLOW |

| Salinity | salinity [g kg-1] | Delft3D-FLOW |

| NCRatGreen | green stoichiometric constant for N over C in algae biomass [gN gC-1] | 0.12 |

| PCRatGreen | green stoichiometric constant for P over C in algae biomass [gP gC-1] | 0.01 |

| NCRatDiat | diatoms stoichiometric constant for N over C in algae biomass [gN gC-1] | 0.16 |

| PCRatDiat | diatoms stoichiometric constant for P over C in algae biomass [gP gC-1] | 0.01 |

| SCRatDiat | diatoms stoichiometric constant for Si over C in algae biomass [gSi gC-1] | 0.15 |

| NH4KRIT | critical concentration of ammonium [gN m-3] | 0.1 |

| SWRear | switch for oxygen reaeration formulation - | 7 |

| fPPtot | total net primary production [gC m-2 d-1] | 10 |

| fResptot | total respiration flux [gC m-2 d-1] | 0.5 |

| CBOD5 | carbonaceous biological oxygen demand [gO2 m-3] | time-varying |

| SOD | sediment oxygen demand [gO2 m-3] | time-varying |

| SalM1Green | lower salinity limit for mortality Greens [g kg-1] | 0 |

| SalM2Green | upper salinity limit for mortality Greens [g kg-1] | 50 |

| GRespDiat | growth respiration factor Diatoms [1 d-1] | 0.25 |

| SalM1Diat | lower salinity limit for mortality Diatoms [g kg-1] | 0 |

| SalM2Diat | upper salinity limit for mortality Diatoms [g kg-1] | 50 |

| Zooplank | input concentration of zooplankton [gC m-3] | time-varying |

| Latitude | latitude of study area [degrees] | 42.2 |

| RefDay | day number of reference day simulation [d] | time-varying |

| RadSurf | irradiation at water surface [W m-2] | time-varying |

| Ditochl | Chlorophyll-a:C ratio in Diatoms [mg Chlfa/g C] | 22 |

| Grtochl | Chlorophyll-a:C ratio in Greens [mg Chlfa/g C] | 15 |

| Parameter input | Available | Variable selected | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH4+ | YES | ||

| NO3- | |||

| PO₄³⁻ | |||

| Si | |||

| DO | |||

| TIC | NO | DIC | It is assumed that the concentration of TIC is equal to DIC (based on [80]) |

| Alkalinity | pH, water temperature, salinity and DIC | Alkalinity is calculated from pH, seawater temperature, salinity and DIC (based on [80]). Water temperature and salinity fields were retrieved form the IBI_MULTIYEAR_PHY_005_002 product. | |

| Diatoms | NO | Chl-a | Based on [79] from 1987 to 1996 at Ría de Vigo. December, January, February: 40% diatoms and 60% green. March, April, May: 80% diatoms and 20% green. June, July, August: 50% diatoms and 50% green. September, October, November: 80% diatoms and 20% green. |

| Green Algae | |||

| Opal-Si | NO | PHYC | PHYC × (28/12) × 0.5 × 0.13 (based on [82]) |

| POC1 | NO | PHYC | PHYC × 2 × 12/1000 (based on [82]) |

| PON1 | POC | POC × (14/12) /106 (based on [82]) | |

| POP1 | POC | POC × (31/12) / 106 (based on [82]) |

| Parameter input | River | Source | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH4+ | Minho | [83] | Monthly NH4+ values (2010 - 2011) |

| Rías Baixas | HYPEWEB | Monthly IN values from all available models (2000-2010). It is assumed that 10% of the IN corresponds to NH4+ (based on [82]) | |

| NO3- PO₄³⁻ Si |

Minho | [83] | Monthly values (2010 - 2011) |

| Rías Baixas | [84] | Maximum value dry and wet season (1980-1992) | |

| DO | Minho Rías Baixas |

[83] - |

Monthly O2 values (2010 - 2011) A constant value of 8 gO2 m-3 is assigned. |

| TIC Alkalinity |

Minho Rías Baixas |

[83] [85] |

Alkalinity is calculated from pH, TIC, water temperature and salinity following [82]. Seasonal values (2002) |

| Diatoms Green Algae |

Minho Rías Baixas |

[83] - |

Monthly values of Chl-a (2010 - 2011) are divided by two. A constant value of 0.001 gC m-3 is assigned. |

| Opal-Si | Minho Rías Baixas |

- - |

A constant value of 0 gSi m-3 is assigned. |

| POC1 PON1 POP1 |

Minho | HYPEWEB | Based on [82] it is estimated that: PON = TN – (NH4++NO3-); POC = 12 x PON; POP = TP – PO4 |

| Rías Baixas | [85] | Seasonal values (2002) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).