1. Introduction

“He deals the cards as a meditation, … to find the answer, the sacred geometry of chance, the hidden law of a probable outcome, the numbers lead a dance…”

Sting, The Shape of My Heart

“A little neglect may breed great mischief… For the want of a nail the shoe was lost; for the want of a shoe the horse was lost; and for want of a horse the rider was lost… For the want of a battle the kingdom was lost, And all for the want of a horseshoe-nail.”

Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanac

I have been fascinated by biology, especially human biology, my whole life. As a doctor I have dedicated myself to the study of health and disease. I have been interested in a particular organ’s health-the breast. Most of my professional thinking, as a general surgeon then plastic surgeon, has focused on breast cancer and its treatment. Recent paradigm shifts in biology, evolution, and cancer research have led to the realization that life and disease are too complicated to be solely explained at the molecular and cellular level [

1]. Life is a competition for free energy in the environment, needed for a limited time to reduce entropy locally, to stay alive, so that we can be sure to pass life on. Cancer too must be understood at more than the molecular and cellular level; it must be thought about at the tissue, organ, and organismal level [

2]. The Somatic Gene Theory’s failure to explain the discovery of an ever increasingly complex set of characteristics, of the spectrum of neoplasia, has opened the door for questioning this orthodoxy. Multiple alternative theories of the causation of cancer are being seriously considered as the 21

st century moves into its second quarter [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

2. Breast Cancer as a Developmental Disease

Breast cancer is thought to be a developmental disease of the breast organ [

9]. That is, breast cancer is a fundamental break down of the coordinating limiting factors of tissues: cells and extracellular protein matrix (ECM), the so-called tumor microenvironment (TME). Most of the important information presented in this paper was published in the 1990s. However, not until just recently have cytologists [a term first coined in 1962 by Smithers [

10]], who have led a publication filibuster for over 60 years, yielded the floor to the organismists. Hanahan’s 2024 publication has raised the number of

Hallmarks to such a level that the Somatic Gene Theory has spun out of orbit [

11]. Weinberg’s solo publication admits it is time for biologist studying cancer to go back to the drawing board [

12].

The cells and proteins, which first come together two-months after conception, make the breast gland which matures into the adult form at puberty [

13]. The hormonal milieu of pregnancy sets into motion a spring-time season of the female breast tissue that is a recapitulation of embryonic lactiferous epithelial development. The breast gland fulfills its destiny by realizing the production of milk that sustains the infant’s nutrition, until it is mature enough to fend for itself. When man lived in small hunter-gatherer bands, at the origin of our species, successful breast feeding was essential to leaving behind progeny. Prior to the epigenetic development of larger society, which evolved with the start of agriculture and animal husbandry, then complex civilizations with wet nurses or substitutes like cow’s milk and ultimately grocery store formulas, failure of the mother’s breasts was an existential threat to survival of the human species. Perhaps it was the Neanderthal breast that was inferior. It is therefore little wonder that human

culture would put such a high priority on the health and maintenance of the breast

organ. If a woman’s years of fertility are limited and if bad luck has led to barrenness, then the last successful ovulation which leads to impregnation

must lead to successful milk production by the breast organs, for the offspring to survive infancy. But what rules regulate the complex set of interactions involved in the above scenario? Put another way, in the absence of human societal culture, the culture of organs must prevail for preservation of the species.

3. Living Anatomy of Organs

In the late 1930s, just before the outbreak of war in Europe, an important scientific study was taking place within Biology. The French surgeon, Alexis Carrel, awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery of the technique for vascular anastomosis, had turned his attention to organ transplantation and tissue engineering [

14]. In 1938 he and his famous friend, Charles Lindbergh, published “The Culture of Organs”. The removal of whole organs, from experimental animals, for physiological study would require that Lindbergh, who entered medical research after having watched his sister-in-law die prematurely from a heart condition, invent a perfusion pump to keep organs alive and functioning outside the body [

15]. Carrel, who in the early 1900s was a pioneer in the burgeoning field of cell culture, had devised the fluid medium that would be pumped. But it was Alexis’ vision of the importance of studying the

living anatomy of

whole organs and not just dissected dead parts, that set the scientific project apart. Unfortunately, WW II would interrupt the thoughts of scientists, causing some of the most gifted of the group to leave Europe as a matter of survival from the eugenics Lindbergh subscribed to and the Nazi plague Carrel’s Vichy government sympathized with. Carrel died of natural causes shortly after the war, saving him the embarrassment of being tried for collaborating with the Nazis. His legacy did not recover, and this limited his influence on biologic thought of the 20

th century. The 1950s and sixties would usher in a 70-year reign of cell biology, genetics, and the study of cancer cells in flasks- not perfused organs. Only just now are we fully appreciating what a mistake this wrong turn in history was. The following paragraphs are taken from the first few pages of chapter one, of Carrel and Lindbergh’s 1938 book, the “The Culture of Organs” [

16].

“The concept of tissue and organs, as taught by classical anatomy, are simple and convenient. But, like all abstractions, they are an incomplete expression of reality. They have shown their usefulness in providing a basis for physiology and pathology… It does not unveil the mechanism of most commonly observed phenomena, such as inflammation of a tissue, growth of a tumor, cicatrization of a wound. Living organs differ profoundly from organs removed by dissection from the body, because tissues and circulating blood constitutes an indivisible whole… A cell is bound to medium (lymph filling the intra-organic spaces) strictly as nucleus to cytoplasm.”

“This medium is secreted by tissues and organs and, in turn, regulates their activity… The structure and functions of an organ rest simultaneously on its hereditary properties, on its previous history, and on the state of its humors… These chemicals (components of blood plasma) are indispensable to the constitution of each organ as are epithelial and connective cells and their framework… Cells and medium are one.”

“An organ separated from the body by dissection is rendered timeless and functionless. Structure, time, and function, are only aspects of the wholeness of living organisms. … An organ is essentially an enduring thing. It is a movement, a ceaseless change within the frame of an identity. The duration of an organism is equivalent to those chemical changes of tissue and blood plasma that express themselves in growth, maturity, old age. The rigidity and immobility of their appearance are illusions, because they flow into physical time at the same rhythm as the observer… Physiological time is merely the fourth dimension of the living organism.”

4. The New Biology

It is this ethos that typifies the new era we embark on, in what Phillip Ball has called the “New Biology” [

17]. A break from the old biology: reductionist, simple narratives about parts built of smaller and smaller parts, which function linearly with predictable outcomes. The old biology is built on a Newtonian world, but the new biology is a quantum world which is complex and full of non-linear systems that have stochastic outcomes, built of emergent properties, and quite possibly… biological entanglement [

18]. This is the world of the human embryo at eight weeks, when the breast anlage emerges [

19]. The embodied truths of ontogenesis are essential to understanding the origins of cancer. Therefore, future advances in cancer research will require us to return to the beginning of the story of tissue and organ development.

5. Spatial Opportunity and Metabolic Occasion

Erich Blechschmidt teaches us that development takes place when there is a spatial opportunity and a metabolic occasion [

19]. He explains the emergence of tissues by defining the fundamental orientation of limiting and inner tissues: limiting tissues are epithelium on the shore of embryonic fluid spaces or lumens; inner tissues (mesodermal connective tissues) are bounded by the former cells and their basement membranes. All the above is built on an underlying unseen canvas, a Cartesian three-dimensional spatial grid or field which establishes the basic poles of orientation: anterior/ventral, posterior/dorsal, superior/cephalic, inferior/caudal; and the relative growth-spatial relationships of adjacent tissues and cells. How does a cell “know” where it is? Perhaps the electromagnetic field of the collective atoms and their subatomic particles is the basis of three-dimensional field orientation. This three-dimensional geometry is elastic and bending in time, it is topological.

Migrating cell ensembles, in the developing embryo, form their arrangements on a foundation, built of an archaic connective tissue called interstitium. It is the layer of acellular connective tissue, also known as the extracellular matrix (ECM), or loose areolar tissue. The interstitium is composed of “inner tissues” of self-organizing structural collagen bundles, which branch and entangle themselves in fractal, spongelike patterns that define serum filled interstitial spaces, which cannulate because of metabolic contrails. Hyaluronan has a ubiquitous presence in the interstitial spaces [

20]. It can be composed of large, hydrated forms which hold cells together as tissues form, but also small building blocks (created when enzymes known as hyaluronidases break HA into smaller pieces) serving in a local messaging capacity between cells. This multifunctional molecule is a key component of cellular organization and tissue morphogenesis in metazoans [

21]. Over time budding tubes of the emerging lactiferous ductal epithelium receive and deposit the products of their metabolic needs, in patterns of flow through the labyrinth of the interstitium. In the wake of this metabolic trail, blood vessels emerge. Dike has shown that in vitro endothelial cells grown on micropatterned substate, that are 10 microns in width and coated with ECM, will demonstrate differentiation and formation of capillary tube-like structures containing a central lumen [

22]. Vascular branching

must follow Adrian Bejan’s Constructal Law of Design: “For a finite size system to persist in time, to live, it must evolve in such a way that it provides easier access to the imposed currents that flow through it” [

23]. There is no master architectural plan or DNA code that stipulates this style of branching pattern - given an opportunity, the flow of metabolites will automatically build along the most efficient pattern. In high metabolic tissues, like growing epithelial parenchyma, this means vascular branching in low fractal dimensions [

24]. In the low metabolic field of the mostly acellular inner tissue, the interstitial circulation of metabolites, morphogens, paracrine substances, and migrating cells (both autologous and invading infectious agents) is based on the ebb and flow of serum through the high fractal dimension, sponge like, spaces that exist between collagen cables of the ECM. The histoarchitecture of the interstitium was first described by Theis, et al in 2018 [

20]. In this way, developing organs are comprised of parenchymal epithelium supported by connective tissue stroma built on the interstitium which underlies all organ tissues and wraps around all vascular and neuro cables [

25]. The exact differentiation of mesenchymal cells in the developing connective tissue depends on the physical characteristics of the local ECM [

26]. We shall return to examine the controlling relationship ECM has on cellular behavior when we look for the beginnings of cancer.

6. The Interstitium as a Body-Wide System

The interstitium of metazoans most likely was built on a renovated sponge skeletal design, which is made from a collagen-like protein called spongin. The entangled three-dimensional branching of spongin is self-organizing and is produced by specialized cells known as amoebocytes [

27]. Sponge cells bind to circular hyaluronic acid like proteoglycans called spongicans [

28]. Animal tissues have a sponge like collagen foundation to their connective tissues, with serum and hyaluronic acid flowing through the open interstitial spaces. It is on this prior art, that animal tissues were first invented by nature. The epigenesis of tissues emerge in horizontal lamina which build vertical depth over time during development. In some ways this is analogous to 3-D printing, or the rings of a tree trunk, the layers of sedimentary rock, or Piaget’s horizontal and vertical decalage concept, in which intelligence is built over developmental milestones, over space-time. Multicellular organisms are composed of a heterarchy of tissue and organ systems. Whether it is the bottom-up influence of DNA inheritance, which affects the proteome of cells and tissues, or the top-down influence we know as epigenetics, living organisms are complex wholes which must be understood by their interconnectedness.

Animal cells are not amoebas or paramecium that swim through archaic seas. Animal cells live on dry land and must take their sea water with them everywhere they go. They have outer skins which allow autonomous separation from their environment, and as Claude Bernard first taught, allow the inner homeostasis of their internal milieu. But all this magic requires organs built of specialized tissues. Also, animal cells do not swim. Animal cells migrate on their ECM scaffolds, like adventurers who free climb on sheer rock walls.

Donald Ingber has published his findings showing the importance of mechanical forces in morphogenesis and cell differentiation. He explains that tensegrity-like prestressing of structural ECM proteins outside of the cell connect to the tensioned intracellular cytoskeleton and microtubules, which convey mechanotransduction effects on the nucleus and gene expression. He states, “… mechanical forces generated by living cells are as crucial as genes and chemical signals for the control of embryonical development, morphogenesis and tissue patterning.” [

29,

30].

The second month of human fetal development marks the beginning of the breast as an organ. The fertilized egg has gone through symmetry breaking cellular divisions that resulted in the development of the morula. Thomas Meyers calls the infoldings of the conceptus, “double bag” maneuvers [

31]. The first of these creates the “blastula stage” of the developing embryo. Differential growth rates and their metabolic byproducts physically separate and shape early tissues, which Blechschmidt calls anlages of the eventual organs. The developing ventral thorax demonstrates a sagittal mammary line to the left and right of center. On these lines the human embryo picks a point, between the fourth and fifth ribs, to start its invasion of mesodermal adipose tissues by ectodermal epithelial cells. This process of epithelial branching begins with a remodeling and weakening of the basement membrane by the actions of matrix metalloproteinases [

32], which triggers an avalanche of separation, in the underlying tensioned, mesodermal interstitium. Ingber likens it to a “run” in a women’s nylon stocking [

30], because the interstitial fibers and filaments are pretensioned in a tensegrity architecture [

33]. This tearing crack, in the spongy labyrinth of collagen bundles, parts the sea of inner tissue, sucking the overlying epithelium into the chasm created in the interstitial ECM, thus making way for the low fractal dimension branching of the breast’s lactiferous ductal system. This is not the time for lobular cell development- that will have to wait many years for the hormonally stimulated beginning of puberty. But even this early coordinated cellular subordination, to the common good, requires paracrine communication along the local backwater paths of the interstitium. The epithelial invasion, of the mesodermal lands, pulls with it trailing caissons of vascularity [

30]. Branching epithelial ducts become mired in the muck of the interstitium, which eventually halts the momentum of their campaign. The overwhelming flood of ectodermal invagination and branching lactiferous expansion compresses against the interstitial collagen fibers it is invading, and the compressed exterior border becomes known as the pseudo-capsule of the corpus mammae, just like the surface tension of a baking boule of bread forms a crust (

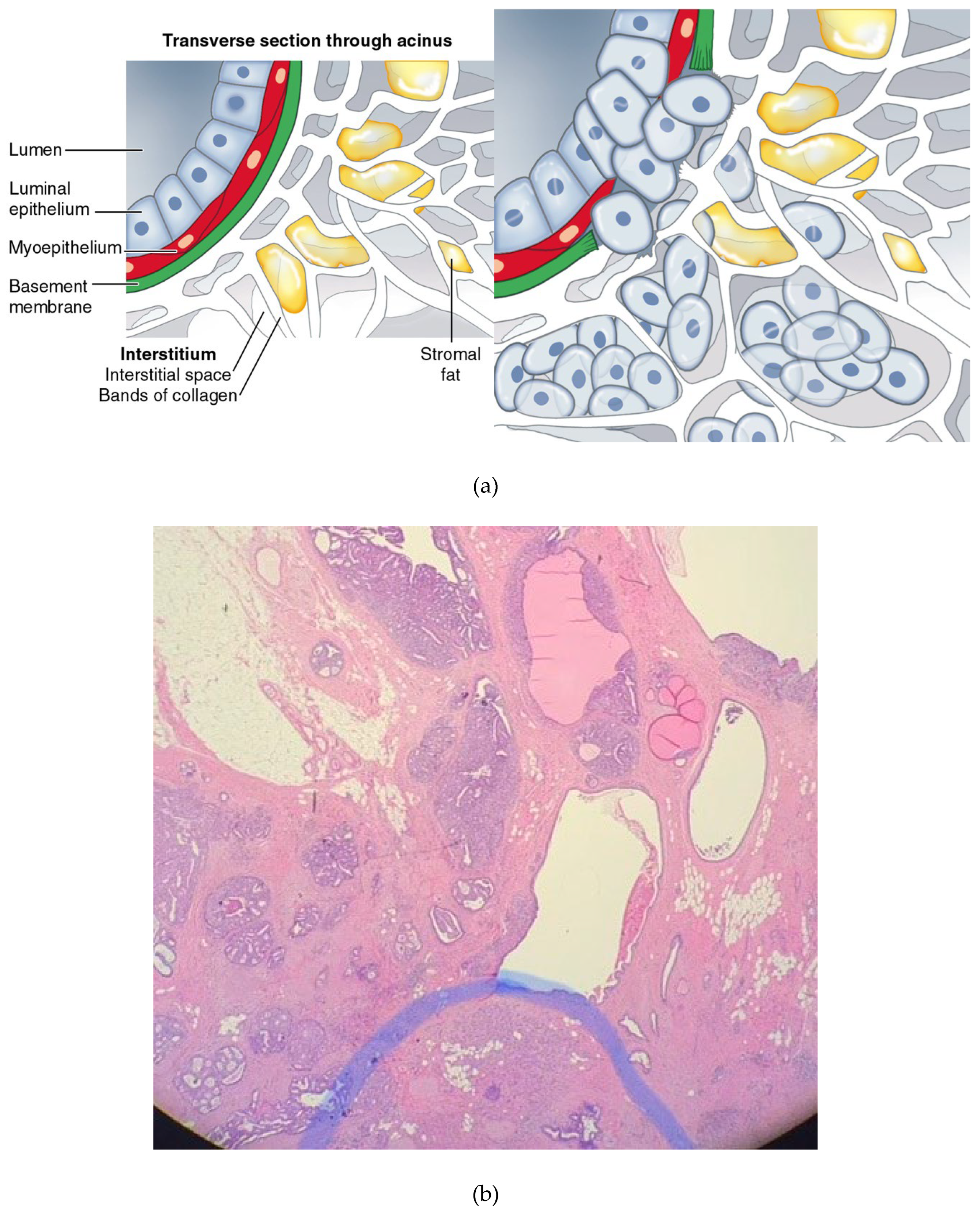

Figure 1 a & b). The relatively immobile chest wall that is adjacent the posterior surface of the corpus mammae causes a flat surface, while the more elastic skin/soft tissue envelope on the breast gland’s anterior surface allows for a fluffy morphology, like cumulus clouds. This is the background history of the breast organ, when cancer emerges; in the process of autopoiesis cellular populations of tissues become mutinous. The end terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU) (

Figure 2 a & b) has been called the site of the cancer tumor microenvironment (TME). What is the morphology of this break down in breast culture, and should it more correctly be called the cancer tissue environment (CTE)?

7. The Failure of Organ Culture

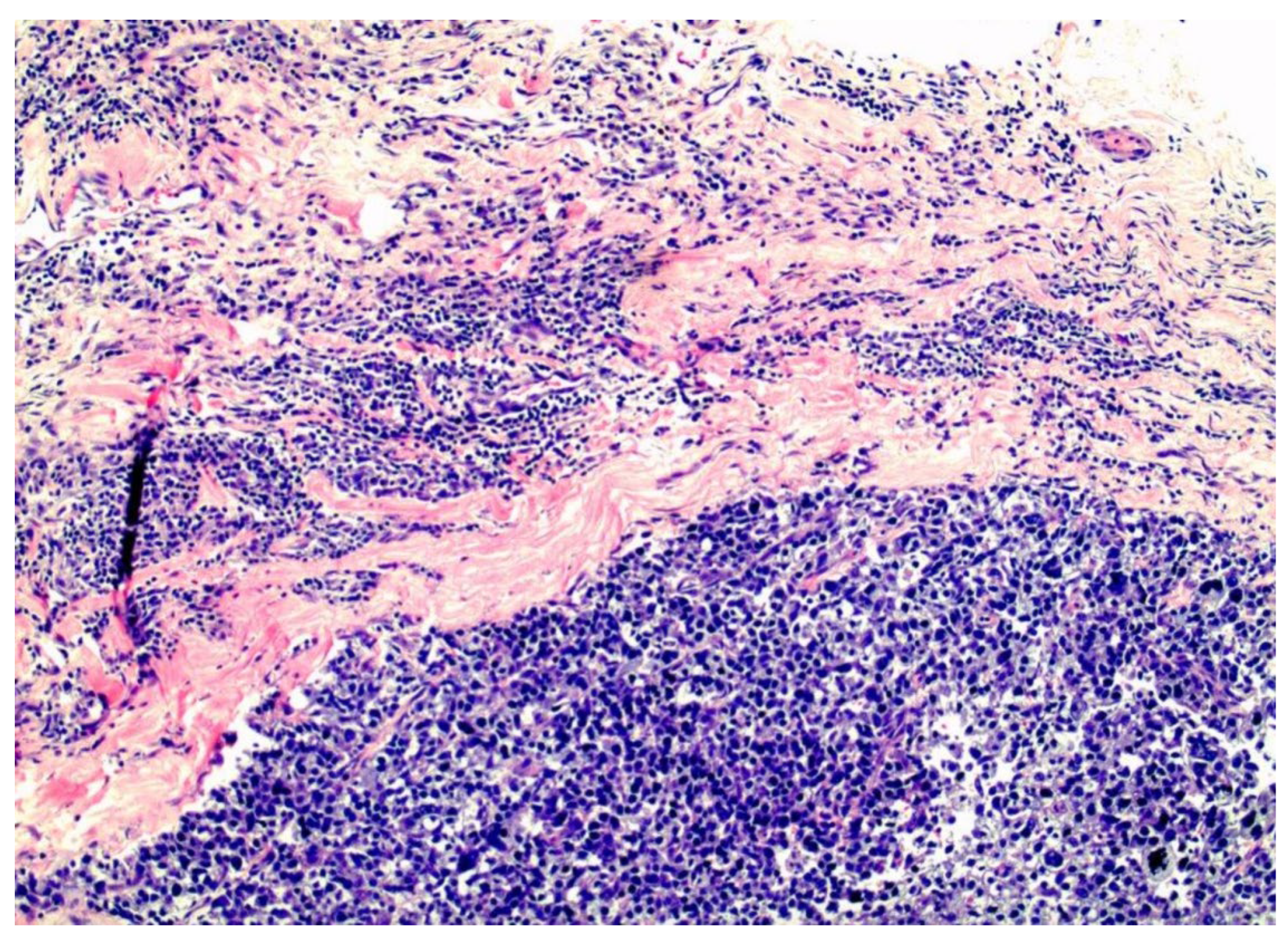

It is possible that the snapshot of a breast needle biopsy will catch tissue which exhibits ‘carcinoma in situ’. Abnormal cell behavior in a tissue can be seen on a spectrum of abnormality. In situ neoplasia is uncoordinated cellular mitoses with an intact basement membrane. Once the basement membrane’s constraining boundary fails, a flood of uncivilized cells enters the adjacent interstitium (

Figure 3 a & b). They have crossed the Rubicon. “Cancer cells” do not inhabit adjacent cells in parasite fashion, the way that some theorists suggest microbes become parasites in tumor cells [

6]. Therefore, by definition, they inhabit

interstitial space. Invasive cancer is “looking” for room to grow within the expandable interstitial space, defined by the bundles of collagen it infiltrates (

Figure 4). The interstitium is characterized by its dynamic ability to enlarge dramatically because of inflammation, binding more volumes of water to hyaluronan, thus setting the stage for the required space for tumors to grow. These multiplying epithelial cells lose their connection to each other when connections called E-cadherins stop being expressed, severing the grounding of epithelial cells to basement membranes, hyaluronan, and fibronectin. Through failures of desmosomes, gap junctions, tight and anchoring junctions, epithelial cells separate, lose their polarity and cross the dissolving basement membrane, and crawl into the interstitium. This withdrawal from the organ community unhinges their mechanical connections to each other and the local extracellular proteins. De-differentiation and migration are hallmarks of the so called epithelial to mesenchymal transition, or EMT for short. Once they arrive in adequate tissue tumor environments, like the interstitium, they revert to epithelial cells in a process termed mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET) and begin to grow enlarging tumors. Tumor cells frequently are found to have hybrid states, exhibiting both epithelial and mesenchymal traits [

34]. These tumors are frequently highly aggressive tumors, such as the triple negative breast cancers [

35].

The isolation from their tissue confraternity leads the change to a spherical cellular shape, and a resulting dedifferentiation. Failure of following apoptosis programs and immune surveillance allows instead a malignant remodeling of the interstitial ECM.

The breakdown in coordinated attachment of the epithelial lining is like a dancing couple getting out of step. The cells no longer are following a collective choreography but enter a mosh pit. The timing, rhythm, and movement of cell growth breaks all the rules of tissue culture. A “cancer cell” revolts against subordination to the collective good of tissues, and according to Sonnenschein and Soto, reverts to its natural state: constant growth, division, and migration. These authors have long argued for a more holistic understanding of cancer as it relates to the whole organism through the disciplines of systems biology and morphogenesis controlled by self-organization [

36].

The high metabolic growing tumor cell mass demands more blood flow but there is no longer the branching epithelium of lactiferous ducts, with its low fractal pattern, pushing out ahead of the following vasculature [

30]. The trails of cancer metabolites flow haphazardly in the high fractal dimension pattern of the interstitial spaces, and thus the emerging tumor vascularity, is different from normal breast tissue vascularity [

37]. The instability of a drop in the economic output, of tumor metabolism, opens the door to a metabolic coup- switching from oxidative phosphorylation to the less efficient glycolysis [

38,

39]. When delivery of oxygen and nutrients no longer keep pace with the rate of growth of the tumor, central necrosis takes place. Undifferentiated cells with their high mitotic rate then begin to look for greener pastures to emigrate to. This is the likely cause of tumor macrophage activity that senses and changes the interstitial milieu, thus triggering epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis [

40]. Metastatic cells may find walls of resistance and unreceptive environments in the ECM of distant tissues, but they may find receptive, liberal shores to immigrate to and build tumor colonies. If Bejan is right, the constructal law will say that eventually the flow of the growing tumor economy cannot be sustained [

23]. The organism racked with growing metastatic colonies will not persist over time. The words of the old song serve as a warning:

“Oh, very young

What will you leave us this time?

You’re only dancing on this Earth for a short while

And though you want to last forever

You know you will never will

You know you never will

And the goodbye makes the journey harder still

Oh, very young

What will you leave us this time?

Your only dancing on this Earth for a short while

Oh very young

What will you leave us this time?”- Cat Stevens

8. Conclusions

The break down in the “cell culture” of tissues in specific organ is the beginning of cancer. Here too we hope is the secret to the end of cancer. To overcome cancer the “culture” of organs must be understood and conserved.

Funding

No outside funding, private or institutional, was provided.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in the creation of this essay. Data sharing is not applicable to this article. .

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to our patients, whose trials and suffering with cancer is a constant reminder not to give up hope of a cure.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rosslenbroich, B. Properties of Life: Toward a Theory of Organismic Biology. MIT Press: 2023. ISBNelectronic: 9780262375399. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenschein, C.; Soto, A. Over a Century of Cancer Research: Inconvenient Truths and Promising Leads. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, R.; Bustuoabad, O. The Biological Sense of Cancer: A Hypothesis. Theoretical Biology and Medical Modelling 2006, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A. The Tumor Suppression Theory of Aging. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 2021, 200, 111583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, H. Tumors: Wounds that do not heal—Redux. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorr, L.; et al. Intracellular Bacteria in Cancer—Prospects and Debates. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2023, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lineweaver, C.; et al. Cancer Progression as a Sequence of Atavistic Reversions. Bioessays 2021, 43, e2000305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkwill, F. Mantovani A. Inflammation and Cancer: Back to Virchow? THE LANCET 2001, 357, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenschein, C.; Soto, A.M. The Society of Cells; Taylor&Francis: New York, NY, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smithers, D.W. Cancer: An Attack on Cytologism. The Lancet 1962, 279, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; et al. Embracing cancer complexity: Hallmarks of systemic disease. Cell 2024, 187, 1589–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, R.A. It Took a Long, long Time: Ras and the Race to Cure Cancer. Cell 2024, 187, 1574–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, J.P. Morris’ Human Anatomy; A Complete Systematic Treatise, 10th ed.; The Blakiston Company: Philadelphia, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski, J.A. Alexis Carrel and the mysticism of tissue culture. Med Hist. 1979, 23, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sade, R.M. A Surprising Alliance: Two Giants of the 20th Century. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 103, 2015–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrel, A.; Lindbergh, C.A. The Culture of Organs; Paul B. Hoeber: New York, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, P. How Life Works: A User’s Guide to the New Biology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Matarese, B. Quantum Biology and the Potential Role of Entanglement and Tunneling in Non-Targeted Effects of Ionizing Radiation: A Review and Proposed Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blechschmidt, E. The Ontogenetic Basis of Human Anatomy: A Biodynamic Approach to Development from Conception to Birth; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Benias, P.C.; Wells, R.G.; Sackey-Aboagye, B.; Klavan, H.; Reidy, J.; Buonocore, D.; Theise, N.D. Structure and Distribution of an Unrecognized Interstitium in Human Tissues. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, A.P.; Tien, J.L. Hyaluronan and Morphogenesis. Birth Defects Res. Part C 2004, 72, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dike, L.E.; et al. Geometric Control of Switching Between Growth, Apoptosis, and Differentiation During Angiogenesis Using Micropatterned Substrates. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Animal 1999, 35, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejan, A.; Lorente, S. The constructal law and evolution in nature. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature, 3rd ed.; Echo Point Books & Media: Battleboro, VT, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cenaj, O.; Douglas, H.; Allison, R.; Imam, R.; Zeck, B.; Drohan, L.M.; Chiriboga, L.; Theise, N.D. Evidence for continuity of interstitial spaces across tissue and organ boundaries in humans. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, A.J.; et al. Myotubes Differentiate Optimally on Substrates with Tissue-like Stiffness: Pathological Implications for Soft or Stiff Microenvironments. The Journal of Cell Biology 2004, 166, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesionowski, T.; et al. Marine Spongin: Naturally Prefabricated 3D Scaffold-Based Biomaterial. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Busquets, X.; Burger, M.M. Circular Proteoglycans from Sponges: First Members of the Spongican Family. CMLS, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003, 60, 88–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammoto, T.; Ingber, D.E. Mechanical Control of Tissue and Organ Development. Development 2010, 137, 1407–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingber, D.E. Mechanical Control of Tissue Morphogenesis During Embryological Development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2006, 50, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, T.W. Anatomy Trains, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nistico, P.; Bissell, M.J.; Radisky, D.C. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition: General Principles and Pathological Relevance with Special Emphasis on the Role of Matrix Metalloprteinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4, a01198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingber, D.E.; Wang, N.; Stamenovic, D. Tensegrity, Cellular Biophysics, and the Mechanics of Living Systems. Rep Prog Phys. 2014, 77, 046603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, A.C.; et al. Intraclonal Plasticity in Mammary Tumors Revealed through Large-Scale-Cell Resolution 3D Imaging. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font-Clos, F.; Zapperi, S.; LaPorta, C. Classification of tripple-Negative Breast Cancers Through a Boolean network model of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Systems 2021, 12, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saetzler, K.; Sonnenschein, C.; Soto, A.M. Systems Biology Beyond Networks: Generating Order from Disorder through Self-Organization. Semn Cancer Biol. 2011, 21, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternifi, R.; et al. Ultrasound High-definition Microvasculature imaging with Novel Quantitative Biomarkers Improves Breast Cancer Detection Accuracy. European Radiology 2022, 32, 7448–7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberti, M.V.; Locasale, J.W. The Warburg Effect: How does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016, 41, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Inglesias, A.; Manes, S. The Importance of Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier in Cancer Cell Metabolism and Tumorigenesis. Cancers 2021, 13, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; et al. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Promote Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and the Cancer Stem Cell Properties in Tripple-Negative Breast Cancer through CCL2/AKT/beta-Catenin Signaling. Cell Communication and Signaling 2022, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).