1. Introduction

Arginine methylation is a posttranslational modification (PTM) that regulates several cellular processes, such as transcription, RNA splicing, protein synthesis, signal transduction, and DNA repair, among others [

1,

2,

3]. The terminal ω-guanidinio atoms of arginine residue can be monomethylated (MMA), asymmetrically dimethylated (aDMA) or symmetrically dimethylated (sDMA) [

4]. Different forms of arginine methylation lead to distinct downstream outcomes, for instance, the asymmetric dimethylation of arginine 3 of histone 4 (H4R3me2a) leads to gene activation, whereas its symmetric dimethylation (H4R3me2s) directs to gene repression [

5].

Arginine methylation is carried out by enzymes known as Protein Arginine Methyltransferases (PRMTs), which use the S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) as donor of methyl group; and according to their activity these enzymes are divided in four types [

4] Type I produces MMA and aDMA, type II yields MMA and sDMA; type III catalyzes only the formation of MMA, whereas type IV, which has only been described in yeast and plants, monomethylates the δ-amino of arginine. Mammals have nine members of the PRMT family (PRMT1-9), six of them are type I (PRMT1, 2, 3 ,4, 6, and 8), two are type II (PRMT5 and 9), and one is type III (PRMT7)[

4]. Interestingly, dysregulation of arginine methylation is closely associated with cancer progression, suggesting that PRMTs are potential targets for the development of new anticancer drugs [

4]. In fact, PRMT5 is emerging as the most promising target for a range of solid and blood cancers [

4]. In particular, EPZ015666 is a compound that binds to PRMT5, inhibiting it competitively to the target peptides and non-competitively to SAM, and its antitumor activity has been demonstrated [

6,

7,

8].

In protozoan parasites the types and number of PRMTs vary in each group, but all contain at least one type I and one type II with homology to PRMT1 and PRMT5, respectively [

9,

10]. Interestingly, PRMT5 has been described to regulate transitions in the life cycle of some of these microorganisms [

11,

12].

Entamoeba histolytica, the parasite responsible of human amebiasis, infects up to 50 million people worldwide each year, causing 40,000 to 100,000 deaths annually [

13]. This parasite has two forms in its life cycle: trophozoite and cyst. The trophozoite is the replicative form and is responsible for causing the disease, but to infect the host it must differentiate to cyst.

E. histolytica contains five PRMTs (EhPRMTs), four of them are type I (EhPRMT1a, EhPRMT1b, EhPRMT1c, and EhPRMTA) and one is type II (EhPRMT5) [

9,

10,

14]. However, up to now is not known whether these PRMTs participate in the differentiation of this microorganism. The

in vitro encystment process of

E. histolytica has not yet been accomplished. For this reason,

Entamoeba invadens, a reptile parasite that has highly efficient protocols for

in vitro encystment, has been used as a model system to study

Entamoeba differentiation [

15].

In this work we demonstrate that sDMA is produced in E. invadens and interestingly increases and relocalizes during encystment. The genome database search of this parasite showed the presence of a single type II PRMT, which is similar to PRMT5. Molecular docking of the 3D model of EiPRMT5 with EPZ015666 showed affinity of the compound for the active site of the enzyme. Accordingly, the drug reduced trophozoite viability and cyst formation. These results suggest that PRMT5 could be postulated as a potential target to develop new therapeutic strategies to prevent the spread of amebiasis.

2. Results

2.1. sDMA Occurs in E. invadens and Increases During Encystment

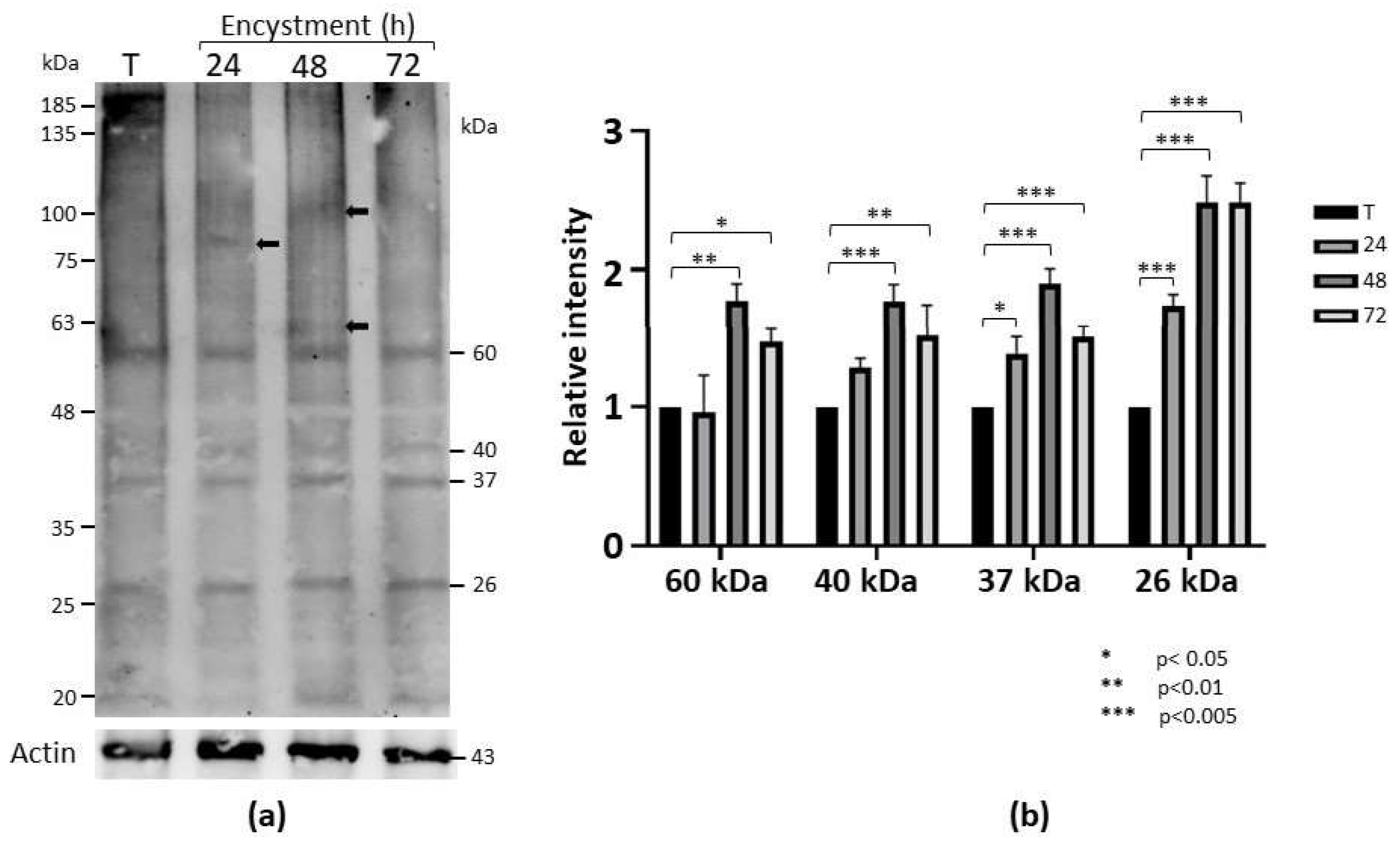

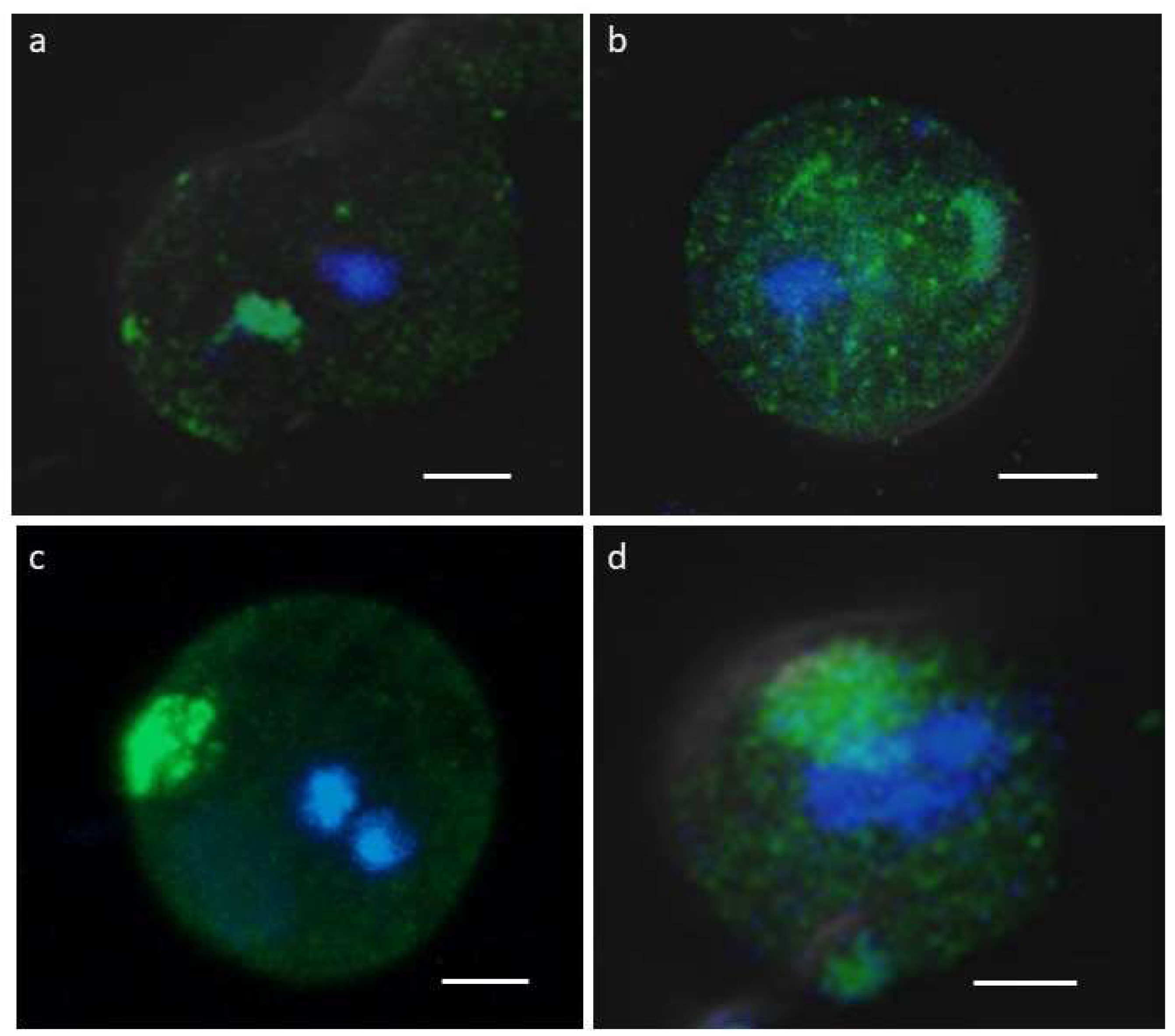

To determine whether symmetric dimethylation of arginine (sDMA) occurs in E. invadens, western blot assays were performed with an anti-sDMA antibody on extracts of trophozoites and cells subjected to 24, 48 and 72 h of encystment process. In these experiments, about 10 protein bands of 20-200 kDa were detected in trophozoite extracts, although recognition was strongest for four bands of 26, 37, 40, and 60 kDa (Fig. 1a). Interestingly, recognition of proteins with sDMA appeared to increase during encystment, and additional bands of 100, 85 and 62 kDa were also clearly present at 24 or 48 h after encystment induction (Fig. 1a, arrows). Densitometric analysis of the four main bands detected by the antibody, using actin recognition as a internal control, confirmed a significant augment of sDMA (Fig. 1b). In trophozoites, by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy, proteins with SDMA were detected in the nucleus, in small dots located in the cytoplasm and near the plasma membrane, and in some parasites a fluorescent signal was concentrated in a larger structure of unknown nature (Fig. 2a). In cells subjected to encystment for 24 h, fluorescence increased, but showed a localization similar to that of trophozoites (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, sDMA proteins were concentrated in one or two poles of the cells subjected to encystment during 48 and 72 h (Fig. 2c,d). These results suggested that the symmetric dimethylation of arginine is involved in the encystment of E. invadens.

Figure 1.

Detection of sDMA in E. invadens. (a) Extracts of trophozoites (T) and encysting cells at different times (24, 48 and 72 h) were subjected to western blot assays using an anti-sDMA antibody. Numbers on the right indicate the molecular weight of the main bands detected by de antibody. Arrows indicate specific bands at 24 and 48 h after encystment induction. Actin recognition, used as an internal control, is shown at the bottom. (b) The four main bands recognized by the anti-sDMA antibody were analyzed by densitometry and the data were normalized respect to those of actin. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation of three biological replicates.

Figure 1.

Detection of sDMA in E. invadens. (a) Extracts of trophozoites (T) and encysting cells at different times (24, 48 and 72 h) were subjected to western blot assays using an anti-sDMA antibody. Numbers on the right indicate the molecular weight of the main bands detected by de antibody. Arrows indicate specific bands at 24 and 48 h after encystment induction. Actin recognition, used as an internal control, is shown at the bottom. (b) The four main bands recognized by the anti-sDMA antibody were analyzed by densitometry and the data were normalized respect to those of actin. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation of three biological replicates.

Figure 2.

Immunolocalization of proteins with sDMA. Three-dimensional reconstruction of Z-stack scan of trophozoites (a) or cells subjected to encystment for 24 (b), 48 (c), and 72 h (d) analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence using the α-sDMA antibody followed by an ALEXA 488-labeled secondary antibody (green). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 3342 (blue). Scale bar: 5 µm.

Figure 2.

Immunolocalization of proteins with sDMA. Three-dimensional reconstruction of Z-stack scan of trophozoites (a) or cells subjected to encystment for 24 (b), 48 (c), and 72 h (d) analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence using the α-sDMA antibody followed by an ALEXA 488-labeled secondary antibody (green). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 3342 (blue). Scale bar: 5 µm.

2.2. E. Invadens Has Only One Type II PRMT

To identify the enzyme that catalyzes sDMA in E. invadens, a search for putative PRMTs was performed in the genome database of this microorganism. This analysis revealed the presence of four genes (accession numbers EIN_172090, EIN_223690, EIN_398100 and EIN_497480) encoding proteins containing PRMT consensus sequences. The nucleotide sequences range in length from 800 to 1978 bp (Supplementary Table 1), although the start codon of EIN_172090 is missing; consequently, its complete sequence is currently unknown. The EIN_497480 gene does not contain introns, whereas the EIN_398100 and EIN_223690 sequences show the presence of one and two introns, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The mRNA sizes corresponding to the genes that are complete in the database range from 966 to 1827 nucleotides, encoding proteins with 321 to 608 amino acids with estimated molecular weights of 37 to 69.8 kDa and isoelectric points of 5.10 to 5.57 (Supplementary Table 1).

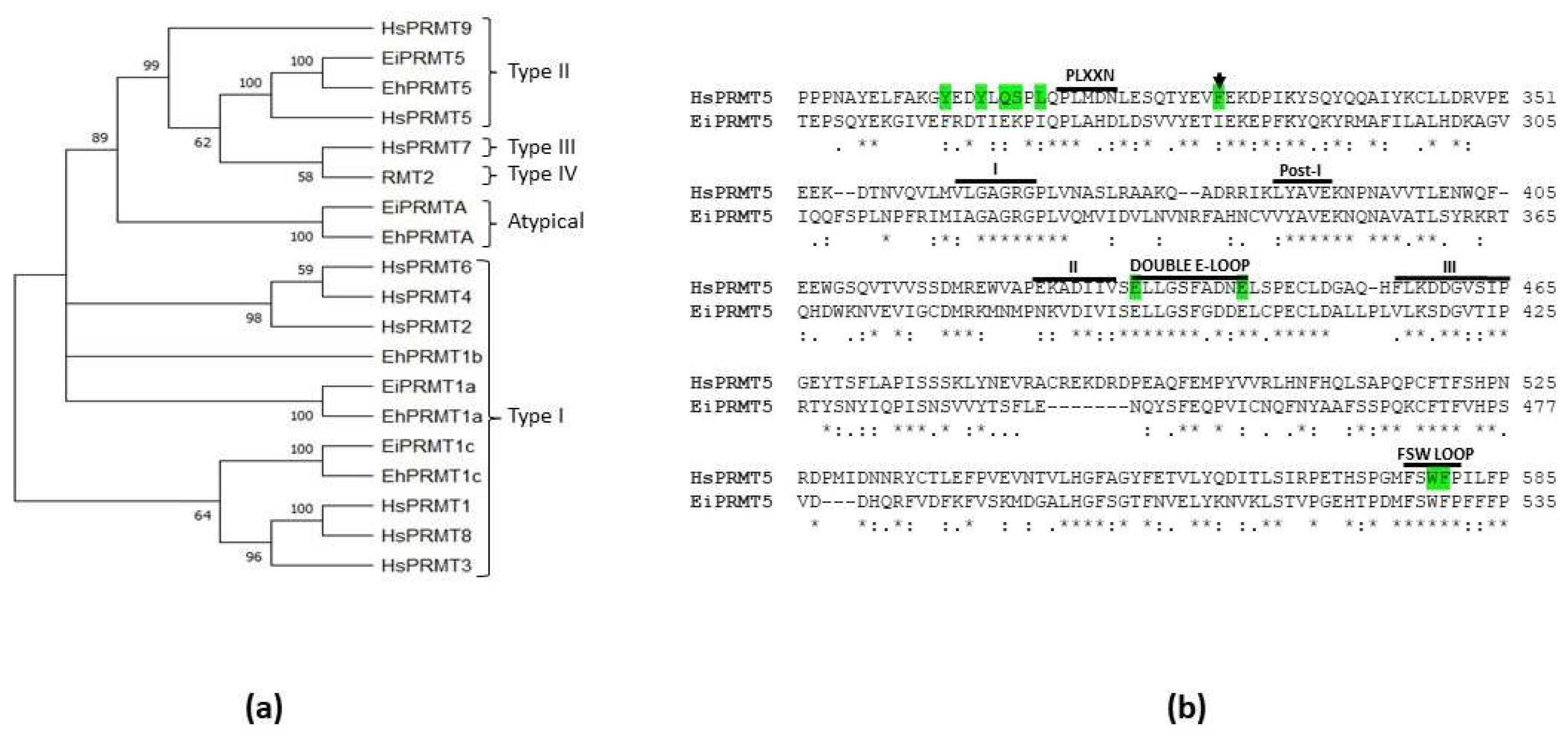

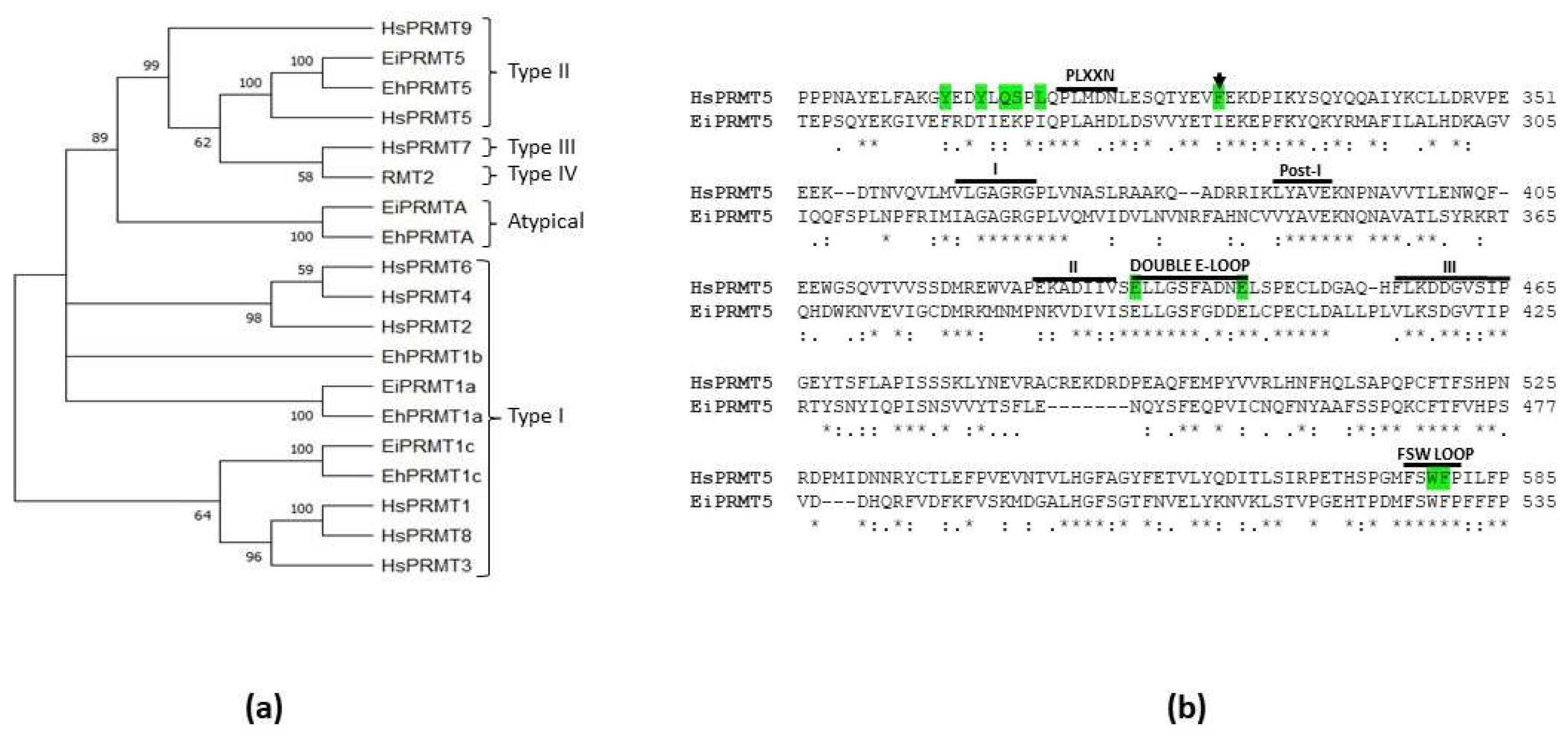

A phylogenetic analysis comparing the amino acid sequences of E. invadens, E. histolytica, and human PRMTs, as well as the type IV PRMT of yeast (RMT2), clustered two of the E. invadens PRMTs with type I enzymes, another was linked with the atypical PRMT of E. histolytica (EhPRMTA), and the last was grouped within the type II family, and more closely associated to PRMT5 (Fig. 3a). Remarkably, this analysis exposed that E. invadens proteins are closely linked to EhPRMT1a, EhPRMT1c, EhPRMTA, and EhPRMT5, where the amino acid sequence identity of each EiPRMT with its respective EhPRMT range between 46.3 and 83.7% (Supplementary Table 2). Due to this relationship, the E. invadens proteins were named EiPRMT1a (EIN_497480), EiPRMT1c (EIN_398100), EiPRMTA (EIN_172090), and EiPRMT5 (EIN_223690), and we suggest that they might have similar functions in both species.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of EiPRMTs and alignment of human and E. invadens PRMT5. (a) The predicted amino acid sequences of

E. invadens PRMTs (EiPRMTs) were aligned with those of human (HsPRMTs),

E. histolytica (EhPRMTs) and yeast type IV (RMT2) and data were subjected to phylogenetic analysis by the Neighbor-Joining method using MEGA11 [

16]. Proteins used for this analysis were: Human: HsPRMT1 (NP_938074.2), HsPRMT2 (NP_001526.2), HsPRMT3 (NP_005779.1), HsPRMT4/CARM1 (NP_954592.1), HsPRMT5 (NP_006100.2); HsPRMT6 (NP_060607.2), HsPRMT7 (NP_061896.1), HsPRMT8 (NP_062828.3). HsPRMT9 (NP_612373.2);

S. cereviciae: RMT2 (NP_010753.1);

E. histolytica: EhPRMT1a (EHI_105780), EhPRMT1b (EHI_152460), EhPRMT1c (EHI_202470), EhPRMTA (EHI_159180), EhPRMT5 (EHI_158560);

E. invadens: EiPRMT1a (EIN_497480), EiPRMT1c (EIN_398100), EiPRMTA (EIN_172090), and EiPRMT5 (EIN_223690). Numbers at the branch nodes indicate the confidence percentages of the tree topology from bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates.

(b) Alignment of human and

E. invadens PRMT5, showing that the parasite protein contains the characteristic sequences of PRMTs (domains I, Post-1, II and III, and the double E domain), as well as typical sequences of the PRMT5 family, such as the FSW loop and the PLXXN motif. Green shaded residues correspond to those of HsPRMT5 implicated in the binding and catalysis of a histone H4-derived substrate peptide [

17]. Arrow indicates the F327 residue, which determines the production of sDMA in HsPRMT5 [1.8].

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of EiPRMTs and alignment of human and E. invadens PRMT5. (a) The predicted amino acid sequences of

E. invadens PRMTs (EiPRMTs) were aligned with those of human (HsPRMTs),

E. histolytica (EhPRMTs) and yeast type IV (RMT2) and data were subjected to phylogenetic analysis by the Neighbor-Joining method using MEGA11 [

16]. Proteins used for this analysis were: Human: HsPRMT1 (NP_938074.2), HsPRMT2 (NP_001526.2), HsPRMT3 (NP_005779.1), HsPRMT4/CARM1 (NP_954592.1), HsPRMT5 (NP_006100.2); HsPRMT6 (NP_060607.2), HsPRMT7 (NP_061896.1), HsPRMT8 (NP_062828.3). HsPRMT9 (NP_612373.2);

S. cereviciae: RMT2 (NP_010753.1);

E. histolytica: EhPRMT1a (EHI_105780), EhPRMT1b (EHI_152460), EhPRMT1c (EHI_202470), EhPRMTA (EHI_159180), EhPRMT5 (EHI_158560);

E. invadens: EiPRMT1a (EIN_497480), EiPRMT1c (EIN_398100), EiPRMTA (EIN_172090), and EiPRMT5 (EIN_223690). Numbers at the branch nodes indicate the confidence percentages of the tree topology from bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates.

(b) Alignment of human and

E. invadens PRMT5, showing that the parasite protein contains the characteristic sequences of PRMTs (domains I, Post-1, II and III, and the double E domain), as well as typical sequences of the PRMT5 family, such as the FSW loop and the PLXXN motif. Green shaded residues correspond to those of HsPRMT5 implicated in the binding and catalysis of a histone H4-derived substrate peptide [

17]. Arrow indicates the F327 residue, which determines the production of sDMA in HsPRMT5 [1.8].

2.3. EiPRMT5 Retains the Characteristic Domains of the PRMT5 Family

The amino acid sequence of EIN_223690 is similar to PRMT5 from different organisms, including the human protein (HsPRMT5), with which it showed 32.98% identity, supporting the hypothesis that it corresponds to the PRMT5 of

E. invadens (EiPRMT5). Furthermore, sequence alignment of EiPRMT5 and HsPRMT5 showed that the

E. invadens protein contains t

he typical PRMT motifs [

19], such as domains I (residues 321-325), post-I (residues 348-350), II (residues 386-391) and III (residues 417-425), as well as the double E loop (residues 393-403) (Fig. 3b). In addition, it possesses sequences described as specific for PRMT5 [

19], such as the FSW loop (residues 527- 530), the PLXXN sequence (residues 268-272), although the asparagine residue is replaced by aspartate (Fig. 3b), and a N-terminal TIM barrel domain. Furthermore, this alignment revealed that of the ten amino acid residues of HsPRMT5 involved in substrate binding and catalysis [

17], EiPRMT5 has four identical and the other four are present as conservative substitutions (Fig. 3b), supporting the hypothesis that it belongs to the PRMT5 family.

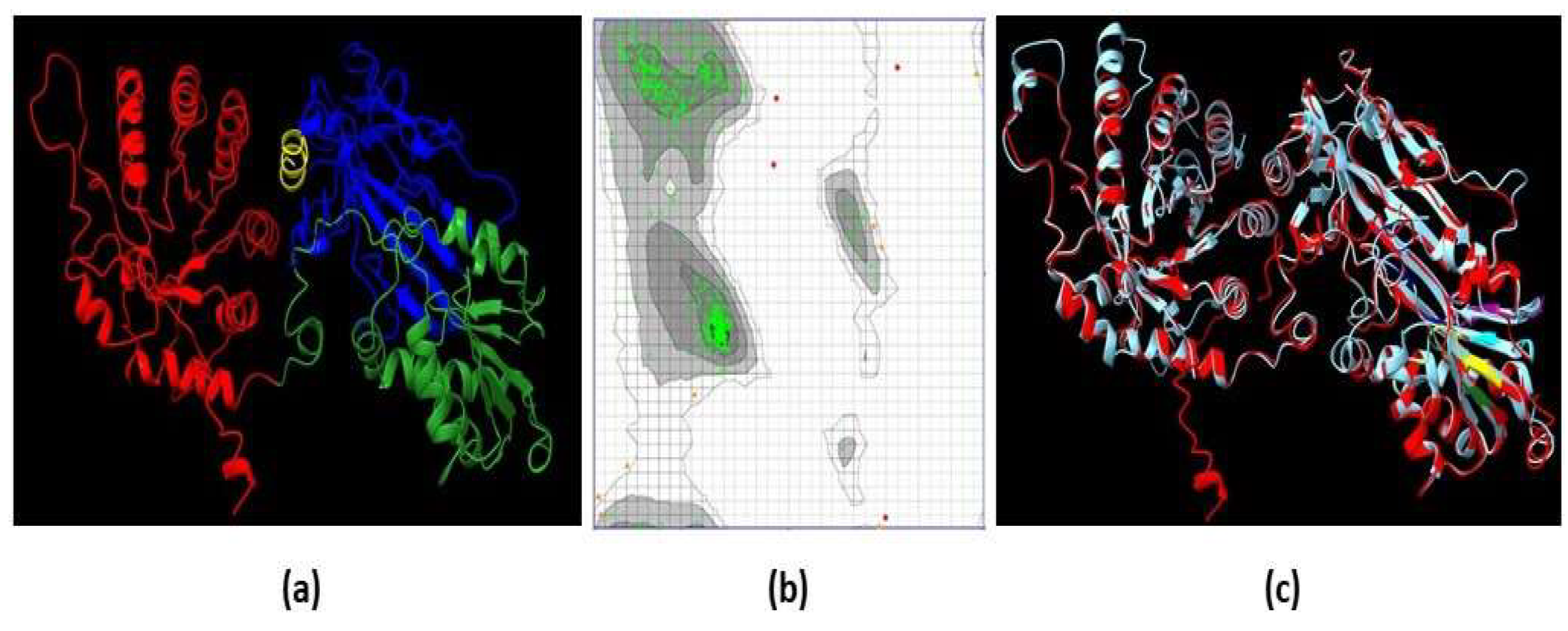

2.4. The 3D Model of EiPRMT5 Showed Homology with the X. Laevis PRMT5 Crystal

The structural conformation of EiPRMT5 (Fig. 4a) was predicted by the I-Tasser server considering the crystal structure of

Xenopus laevis PRMT5 (PDB: 4G56) as a template. The evaluation of this model was performed through a Ramachandran plot, which showed that 97.52% of the residues are located in the most favored regions, 1.72% in the allowed regions, and 0.76% in the disallowed regions (Fig. 4b), data that meet the standard criterion for high-quality protein structures. The overall fold of the EiPRMT5 model displayed: i) an N-terminal TIM barrel domain (residues 9-246), which in the human enzyme binds to the co-factor known as methylosoma protein 50 (MEP50); ii) a Rossman fold domain (residues 247-426), which is responsible for substrate binding and catalysis; and III) a C-terminal β-barrel domain (residues 438- 447), involved in dimerization [

20] (Fig. 4a). When the 3D model of EiPRMT5 was aligned with the crystal structures of PRMT5 from

X. laevis (Fig. 4c) and human (PDB: 4GQB), identity of 33 and 29% was found, respectively.

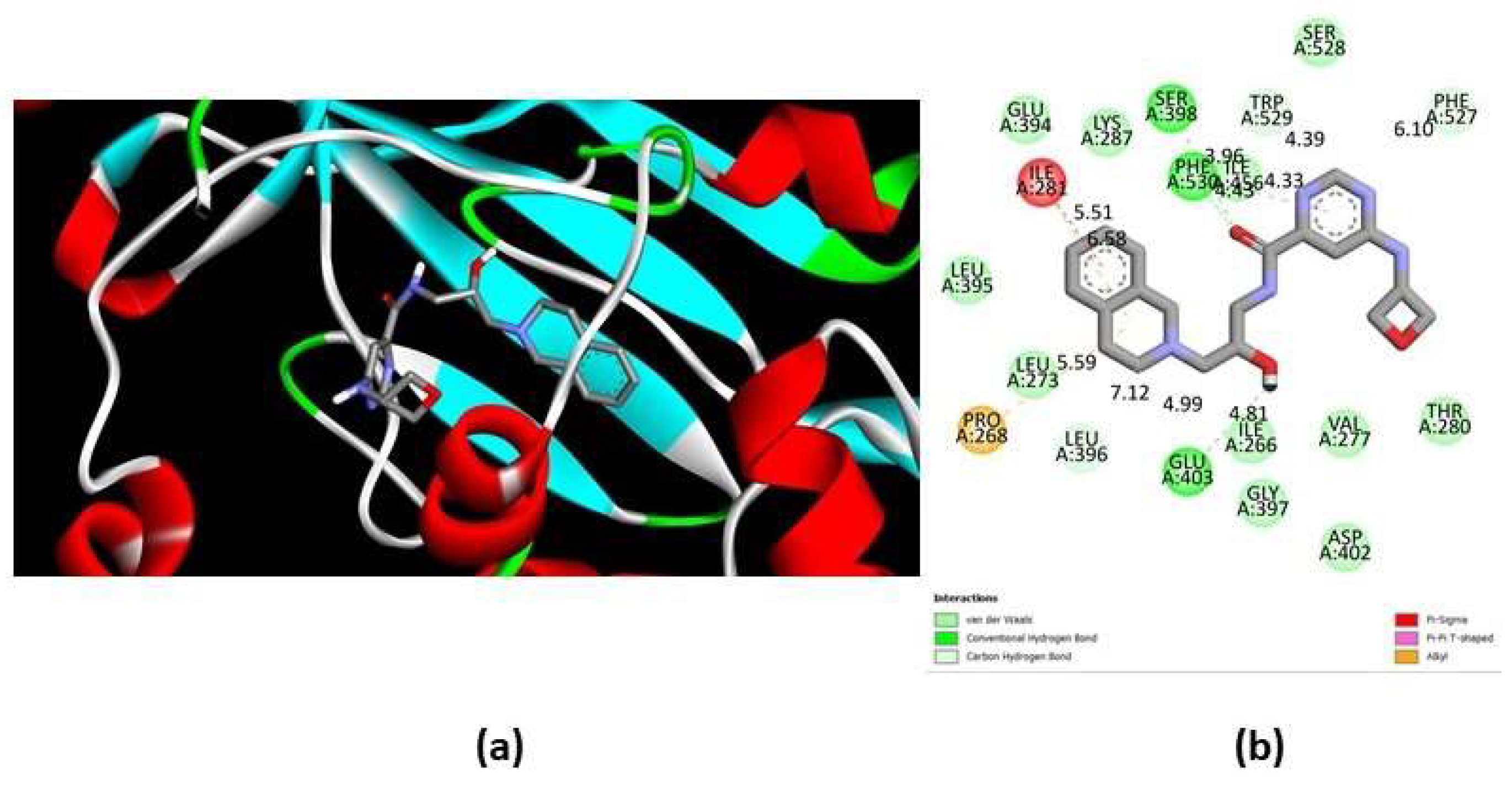

2.5. Molecular Docking Predicts the Binding of EPZ015666 to the Active Site of EiPRMT5

To analyze the possible binding of EPZ015666, a specific inhibitor of mammalian PRMT5 [

8], to EiPRMT5, we performed molecular docking studies using AutoDock 4.2. This analysis predicted that, similarly to what happens with the human enzyme [

8], the drug binds to the peptide-binding site and the pocket occupied by the side chain of the arginine substrate with a coupling energy of ΔG= -6.05 kcal/mol (Fig. 5a). The molecular interactions (Fig. 5b) occur between the tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) and pyrimidine rings of EPZ015666 and residues located mainly in the double E and FSW loops, which are involved in methyl group transfer. The interactions include three hydrogen bonds with residues S398, E403 and F530, (lengths of 3.96, 4.81 and 4.43 A°, respectively) and four carbon-hydrogen bonds with residues L396, E403, F527, and W529 (lengths of 7.12, 4.99. 6.10, and 4.39 A°), as well as several hydrophobic interactions, such as a Pi-sigma (residue I281 with a distance of 5.51 A°), a Pi-Pi (residue F530 with a distance of 4.33 A°), and two Pi-alkyl (residues P268 and I281 with distances of 5.39 and 6.58 A°) (Fig. 5b). In addition, several residues are involved in the binding of the drug through Van der Walls forces (Fig. 5b), including E394, and S528, located in double E and FSW loops, respectively.

Figure 4.

3D model of EiPRMT5. (a) Ribbon representation of the EiPRMT5 structure predicted by I-Tasser. Red: N-terminal TIM barrel domain. Green: Rossman fold domain. Blue: C-terminal β-barrel domain. Yellow: Dimerization arm. (b) Ramachandran plot of the model showing that 97.52% of the residues are located in the most favored regions. (c) Merge of the EiPRMT5 model (red) and the X. laevis PRMT5 crystal (Cian). .

Figure 4.

3D model of EiPRMT5. (a) Ribbon representation of the EiPRMT5 structure predicted by I-Tasser. Red: N-terminal TIM barrel domain. Green: Rossman fold domain. Blue: C-terminal β-barrel domain. Yellow: Dimerization arm. (b) Ramachandran plot of the model showing that 97.52% of the residues are located in the most favored regions. (c) Merge of the EiPRMT5 model (red) and the X. laevis PRMT5 crystal (Cian). .

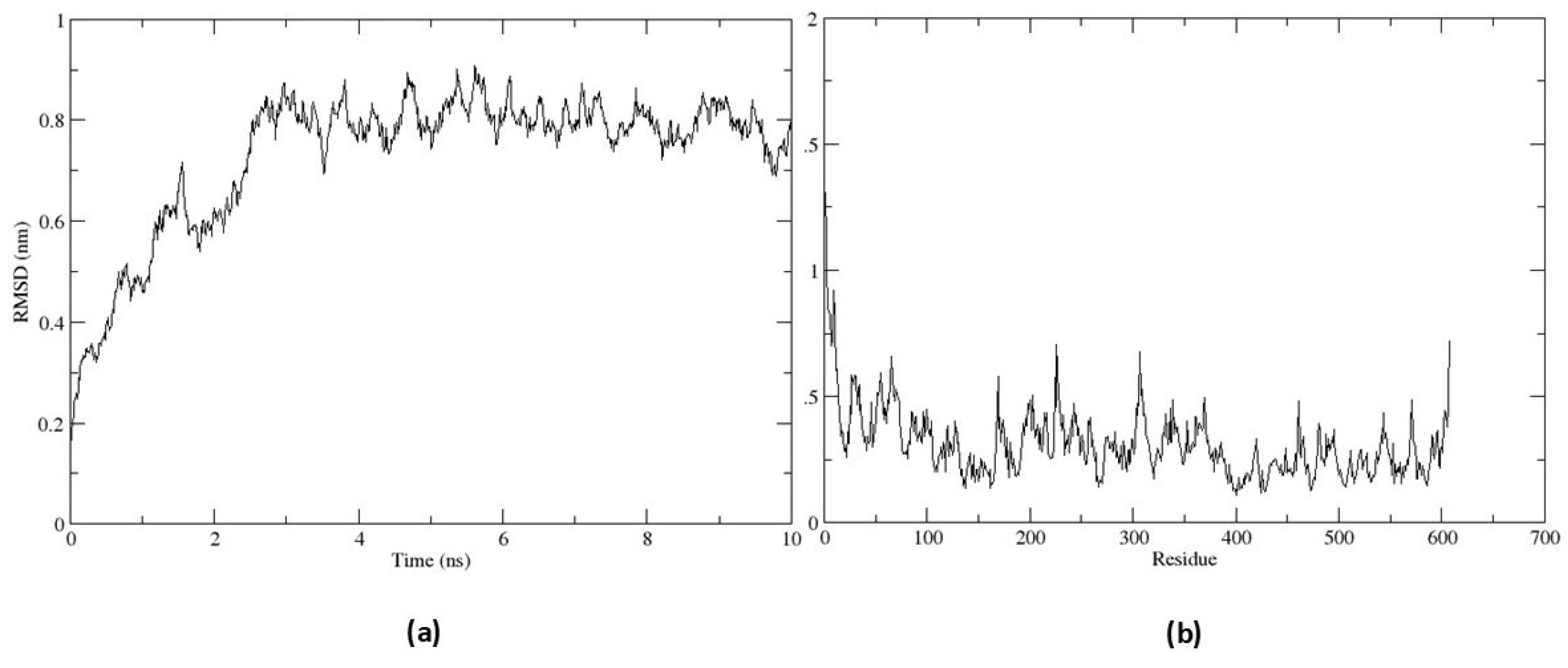

To analyze the stability of the EiPRMT5-EPZ015666 complex, it was subjected to molecular dynamic simulation. The RMSD value increased up to 0.8 nm over the first 2.49 ns and remained within a narrow range for the rest of the simulation time (Fig. 6a), indicating the conformational stability of the protein during the simulation time. The RMSF plot did not show large fluctuations in the protein residues and revealed that residues constituting the active site (residues 393-403 and 527- 530) exhibit fewer flexibility (Fig. 6b), indicative of ligand-complex stability.

Figure 5.

Interactions between EiPRMT5 and EPZ015666. A molecular docking study between the EiPRMT5 enzyme and the EPZ015666 inhibitor was performed using Autodock 4.2. (a) The ligand binding region in the 3D model of EiPRMT5. (b) 2D model showing the amino acxids of EiPRMT5 with which EPZ015666 interacts. The nature of protein-ligand interactions is shown with different color legends.

Figure 5.

Interactions between EiPRMT5 and EPZ015666. A molecular docking study between the EiPRMT5 enzyme and the EPZ015666 inhibitor was performed using Autodock 4.2. (a) The ligand binding region in the 3D model of EiPRMT5. (b) 2D model showing the amino acxids of EiPRMT5 with which EPZ015666 interacts. The nature of protein-ligand interactions is shown with different color legends.

Figure 6.

Molecular dynamic simulation of the EiPRMT5-EPZ015666 complex. The complex was subjected to molecular dynamics simulation for 10 ns (a) RMSD plot. (b) RMSF plot.

Figure 6.

Molecular dynamic simulation of the EiPRMT5-EPZ015666 complex. The complex was subjected to molecular dynamics simulation for 10 ns (a) RMSD plot. (b) RMSF plot.

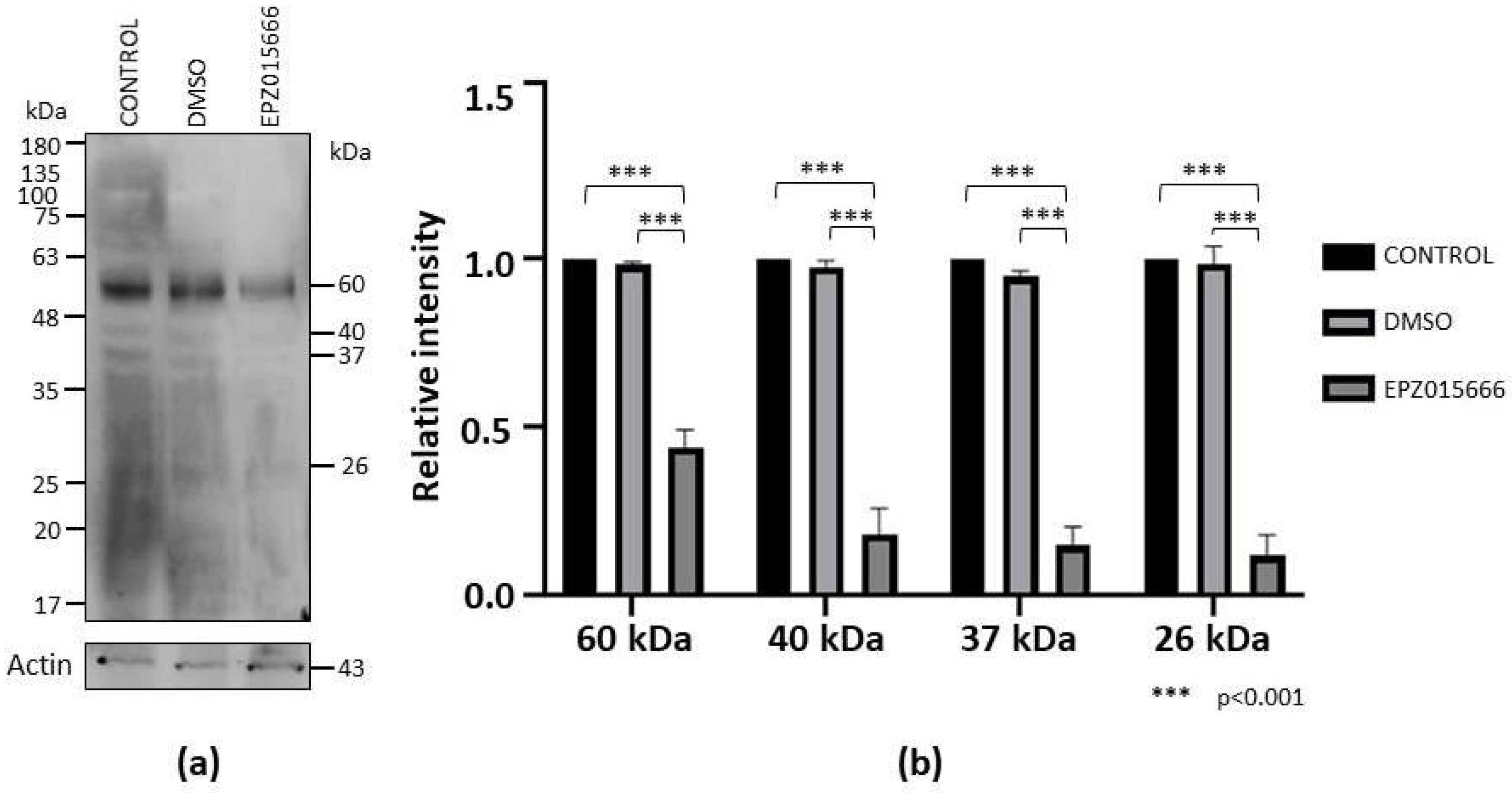

2.6. EPZ015666 Affects Viability and Encystment of E. Invadens

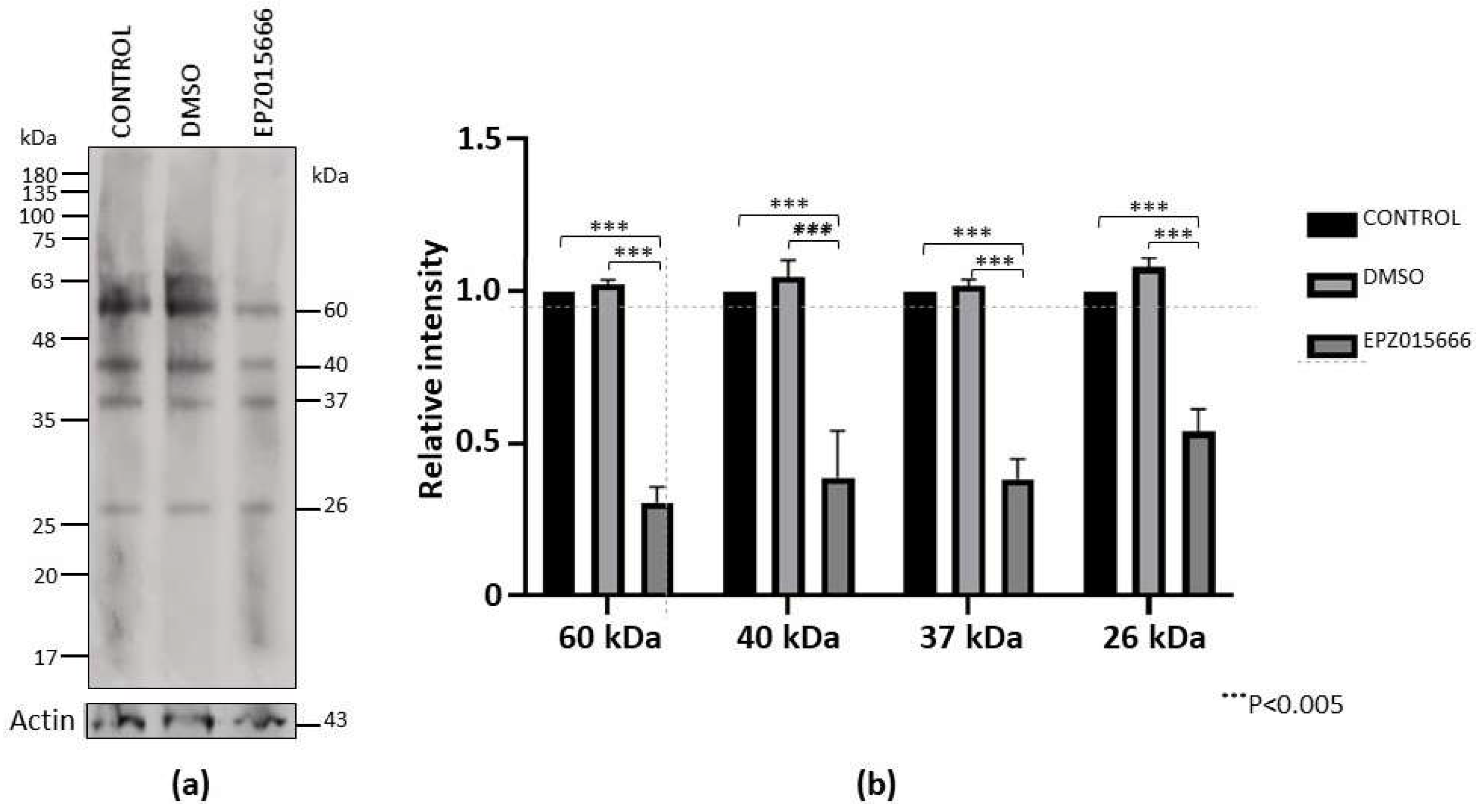

To analyze the impact of EPZ015666 on E. invadens viability, we incubated trophozoite cultures in the presence of different concentrations of the drug for 72 h. In this assay we observed a dose-response effect, with an IC50 of 96.6 ± 6 μM. Furthermore, western blot assays showed that sDMA recognition was decreased in trophozoites treated with the drug (IC20 = 20 mM) for 72 h compared to controls, while actin detection, used as an internal control, was similar under all conditions (Fig. 7a). Through densitometric analysis of the four main sDMA bands, normalized to the actin content, a significant decrease of this PTM by treatment with EPZ015666 was confirmed (Fig. 7b).

Figure 7.

sDMA level in trophozoites cultured in the presence of EPZ015666. (a) Extracts of trophozoites cultured for 72 h in normal medium (control) or in the presence of DMSO (vehicle) or IC20 of EPZ015666 were subjected to western blot assays using an anti-sDMA antibody. Numbers on the right indicate the molecular weight of the main bands detected by de antibody. Actin recognition is shown at the bottom. (b) The four main bands recognized by the anti-sDMA antibody were analyzed by densitometry and the data were normalized respect to those of actin. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of three biological replicates.

Figure 7.

sDMA level in trophozoites cultured in the presence of EPZ015666. (a) Extracts of trophozoites cultured for 72 h in normal medium (control) or in the presence of DMSO (vehicle) or IC20 of EPZ015666 were subjected to western blot assays using an anti-sDMA antibody. Numbers on the right indicate the molecular weight of the main bands detected by de antibody. Actin recognition is shown at the bottom. (b) The four main bands recognized by the anti-sDMA antibody were analyzed by densitometry and the data were normalized respect to those of actin. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of three biological replicates.

On the other side, western blot on extracts of cells submitted to encystment and treated with IC20 of EPZ015666 for 72 h also showed a decrease in the recognition by the anti-sDMA antibody (Fig. 8a). Densitometric analysis of the four main sDMA bands, normalized to actin content, showed that IC20 of EPZ015666 confirmed a significant reduction in sDMA recognition of this PTM (Fig. 8b).

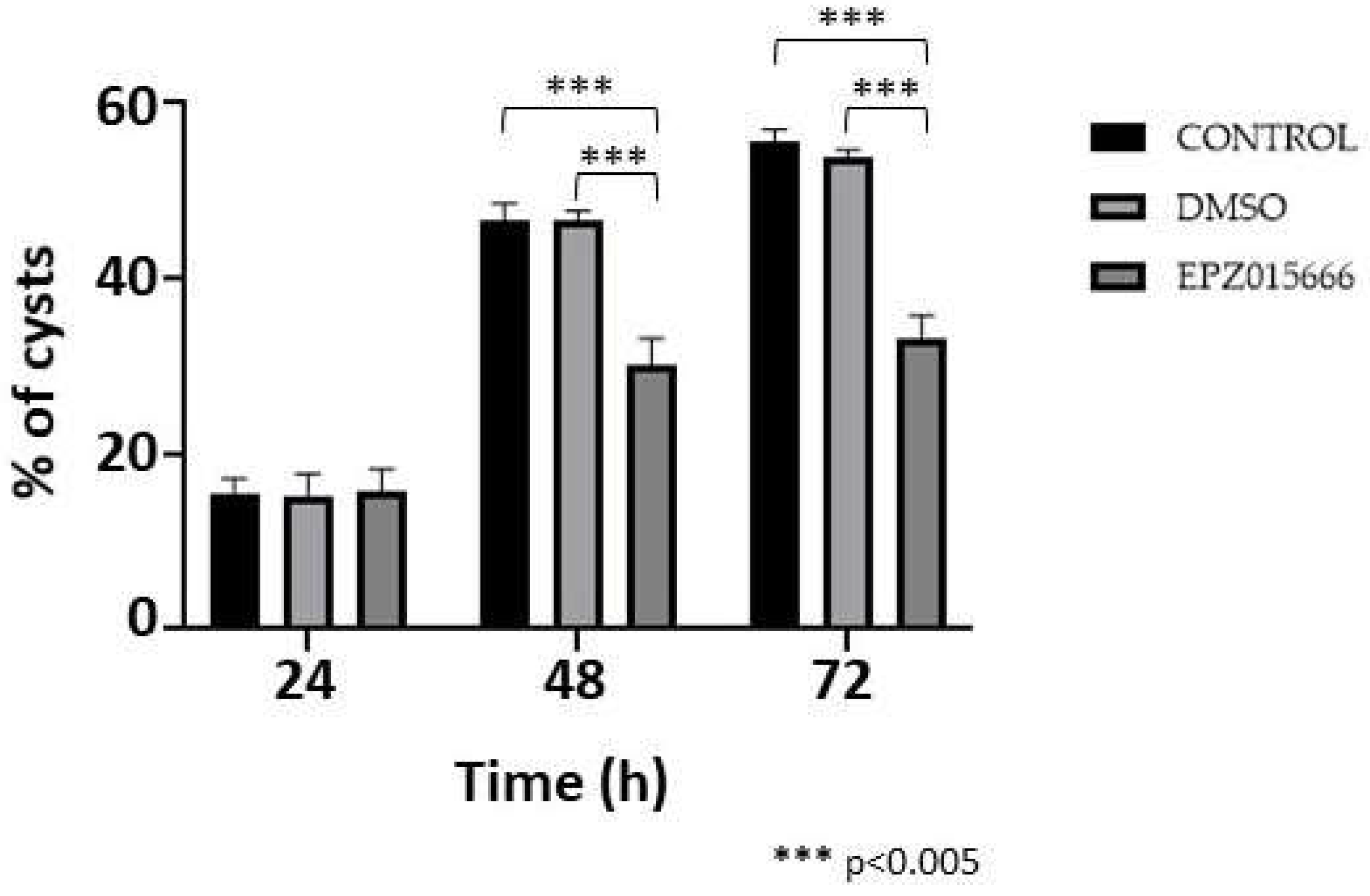

Finally, the efficiency of encystment in the presence of IC20 of EPZ015666 was investigated. In this experiment, the development of cysts at 24 h post-induction was not affected by the presence of the drug, compared to controls; however, at 48 and 72 h cyst formation decreased by approximately 35 and 40%, respectively, whereas the DMSO vehicle had no effect (Fig. 9). The results confirm that symmetric dimethylation of arginine, catalyzed by EiPRMT5, is involved in this differentiation event of E. invadens.

Figure 8.

sDMA level during encystment in the presence of EPZ015666. (a) Trophozoites were submitted to encystment in the presence of IC20 of EPZ015666 for 72 h. Then, extracts were subjected to western blot assays using an anti-sDMA antibody. Numbers on the right indicate the molecular weight of the main bands detected by de antibody. Actin recognition is shown at the bottom. (b) The four main bands recognized by the anti-sDMA antibody were analyzed by densitometry and the data were normalized respect to those of actin. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of three biological replicates.

Figure 8.

sDMA level during encystment in the presence of EPZ015666. (a) Trophozoites were submitted to encystment in the presence of IC20 of EPZ015666 for 72 h. Then, extracts were subjected to western blot assays using an anti-sDMA antibody. Numbers on the right indicate the molecular weight of the main bands detected by de antibody. Actin recognition is shown at the bottom. (b) The four main bands recognized by the anti-sDMA antibody were analyzed by densitometry and the data were normalized respect to those of actin. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of three biological replicates.

Figure 9.

Encystment in the presence of EPZ015666. Trophozoites were submitted to encystment in the presence of IC20 of EPZ015666. Then, the percentage of sarkosyl-resistant cells were determined at 24, 48 and 72 h. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation of three biological replicates.

Figure 9.

Encystment in the presence of EPZ015666. Trophozoites were submitted to encystment in the presence of IC20 of EPZ015666. Then, the percentage of sarkosyl-resistant cells were determined at 24, 48 and 72 h. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation of three biological replicates.

3. Discussion

Symmetric dimethylation of arginine is a PTM that regulates many biological processes, such as epigenetics, splicing, stress response, and development, among others [

1,

2,

3]. Here, we demonstrate that this PTM occurs in

E. invadens and is upregulated during encystment induction. Furthermore, some sDMA-containing proteins relocalize to one or two poles in cells subjected to encystment, suggesting that this PTM has an important role in

Entamoeba differentiation. sDMA is catalyzed by type II PRMTs and

the principal enzyme of this type found in all eukaryotic species studied, including protozoa parasites, is PRMT5 [

9,

10]. Our

in silico analysis showed that

E. invadens has four putative PRMTs, two of them belong to type I (EiPRMT1a, EiPRMT1c), other one, whose sequence is incomplete, forms an independent clado with the atypical EhPRMTA, which is more similar to type I than type II enzymes [

9,

10,

14], while the last one was grouped into the PRMT5 family. Due to the similarity of EiPRMTs and EhPRMTs, we suggest that these enzymes should play similar functions in both

Entamoeba parasites. Because both species have only one type II PRMT and sDMA increases during

E. invadens encystment, we decided characterize PRMT5 as a possible regulator of this process of differentiation.

The amino acid sequence of EiPRMT5 contains the core motifs of all PRMTs [

2]: i) Domain I, which forms the core of the SAM-binding pocket with three highly conserved glycines; ii) Post-domain I that forms hydrogen bonds with the ribose hydroxyl moiety of SAM; iii) Domains II and III, which form a parallel β-sheet to stabilize motif I; and iv) The Double E loop, where the two glutamate residues position the arginine substrate. In addition, it includes the FSW loop also involved in substrate binding, which is specific for type II PRMTs, while in type I PRMTs it is replaced by the THW loop [

2,

3,

4]. Besides, the 3D model of EiPRMT5 showed that it also retains the characteristic structures of PRMT5: An N-terminal TIM barrel, a middle Rossman-fold containing the catalytic core of PRMTs, and a C-Terminal β-barrel, comprising a dimerization arm that contact the TIM-barrel of the other monomer [

18,

21]. PRMT5 from higher eukaryotes forms complexes with MEP50, a 7-bladed WD40 repeat β-propeller protein, which enhances the methyltransferase activity of PRMT5 by improving substrate binding [

3]. In these organisms, PRMT5 forms a heterooctomeric complex composed of four PRMT5 proteins and four MEP50 proteins [

17,

22]. Searching the AmoebaDB genome database we did not identify clear homologues of MEP50 in

E. invadens, although it has several WD repeat-containing proteins and some of them could perform a similar function to MEP50. Alternatively, EiPRMT5 might not require another protein to regulate its activity, as has been shown for PRMT5 from

Trypanosoma brucei [

23].

EPZ015666 is a selective PRMT5 inhibitor that binds to the peptide binding site, given the compound a peptide-competitive and SAM-uncompetitive characteristic and its antitumor role has been tested in several cancer cell lines [

7,

24,

25,

26]. The inhibitor binds to HsPRMT5 via hydrogen bonds to F580 and E444; furthermore, the tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) ring of EPZ015666 forms a water-mediated interaction with E435 and a Pi-Pi stacked interaction with F327 [

8], a residue that directs symmetric dimethylation of arginine [

18]. Alignment with HsPRMT5 showed that EiPRMT5 has identical residues in the corresponding double E and FSW loops of EiPRMT5 (E394, E403 and F530), whereas F327 showed a conservative substitution by isoleucine (I281) in the amebic protein. In concordance, our molecular docking analysis with EiPRMT5 predicted that the inhibitor forms hydrogen bonds with E403 and F530, it interacts with E394 by Van der Walls forces and forms Pi-sigma and pi-alkyl interactions with I281, suggesting that this compound may also inhibit EiPRMT5 activity. Indeed, incubation of trophozoites or cells undergoing encystment in the presence of EPZ015666 diminished sDMA production. However, the

IC50 for trophozoites viability (96.6 μM) is much higher than that for mammalian cells, which varies from 22 nM [

8] to approximately 10 μM [

24]. This discrepancy could be due to differences in plasma membrane permeability or to changes in some residues involved in substrate binding or to the possible absence of a protein that increases the affinity for the substrate, as occurs with MEP50 for PRMT5 from higher eukaryotes [

3]. Alternatively, sDMA could not be very important for trophozoite viability, although the many pathways regulated by PRMT5/sDMA in other organisms suggest that this possibility is unlikely. Therefore, it will necessary to test other currently studied PRMT5 inhibitors or chemical modifications of EPZ015666 to specifically reduce the amebic viability. Furthermore, it would be important to identify the target proteins of EiPRMT5 and their role in the parasite biology. Nevertheless, incubation of cells undergoing encystment with

IC20 of EPZ015666 reduced cyst formation by up to 40%, supporting the idea that sDMA is involved in encystment. Therefore, our results suggest that EiPRMT5 could be considered as a potential target for the development of novel therapeutic strategies against amebiasis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Culture of E. Invadens Trophozoites and In Vitro Encystment

E. invadens trophozoites (IP-1 strain) were maintained in LYI-S-2 medium at 25°C and harvested as described [

27]. To induce encystment, trophozoites were transferred at a final concentration of 5 × 10

5 cells/ml to LG (low glucose) medium (LYI-S-2 medium diluted to 47% without glucose and 5% bovine serum) [

15] and cells were collected at 24, 48 and 72 h. To confirm encystation, cells were incubated in 0.05% sarkosyl for 30 min at room temperature. In addition, some samples of detergent-resistant cells were stained with 1% Calcofluor white (CFW) for 30 min at room temperature and visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX41).

4.2. Western Blot Assays

To determine the presence of sDMA in E. invadens, extracts of trophozoites and cell subjected to encystment were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with an anti-sDMA antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:2,000). The membranes were then incubated with a peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, 1:10000 dilution). Reactions were developed by chemiluminescence (ECL Plus, Amersham), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. To evaluate semi-quantitively the symmetric dimethylation of arginine, same membranes were probed with an anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:3000 dilution), then the four main bands recognized by anti-sDMA were analyzed by densitometry and the data were normalized to that of the band detected by anti-actin. The sDMA level of each band in trophozoites was arbitrary taken as 1.

4.3. Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy

Trophozoites and cells subjected to encystment were fixed and permeabilized with 100% cold methanol for 5 min. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum in PBS; then, samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with the anti-sDMA antibody (dilution 1:100) and subsequently with a secondary antibody coupled to Alexa448 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, dilution 1:200). Finally, nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the cells were observed through a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss LSM 900) using the ZEN 3.6 software. Observations were performed in 13 planes from top to bottom of each sample; the distance between scanning planes was 1 μm.

4.4. Identification of E. Invadens PRMTs and In Silico Characterization of EiPRMT5

The search for putative

E. invadens PRMTs (EiPRMTs), was performed in AmoebaDB (

https://amoebadb.org) using the PRMT consensus amino acid sequence as a query. The predicted gene and protein sequences were analyzed

in silico using the software deposited on the NCBI Homepge (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and on Expasy Bioinformatics Resourse (

https://web.expasy.org).

The amino acid sequences of EiPRMTs were compared to those of human and

E. histolytica PRMTs, as well as to yeast type IV PRMT (RMT2) using the Clustal Omega software. Phylogenetic analyses were carried out using the Neighbor-Joining method implemented in the MEGA11 software package [

16]. Bootstrapping was performed for 1000 replicates.

4.6. Molecular Docking Analysis of the Interaction Between EiPRMT5 and EPZ015666

The 2D structure of EPZ015666 was obtained with BIOVIA Draw 2022 and then converted to 3D .mol format in Avogadro software (

https://sourceforge.net/projects/avogadro). Its geometry was then optimized using Gauss View 5.0 software [

29] and the AMI semi-empiric method. On the other hand, the EiPRMT5 model was edited using the BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer by adding charges, hydrogen and a force field CHARMn method.

For molecular docking studies we used the AutoDock Tools suite version 1.5.7 (

https://autodocksuite.scripps.edu). Blind docking was performed on the entire protein using 10,000,000 evaluations and a genetic algorithm. The results obtained were visualized in the BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer software.

The protein-ligand complex with the best docking energy obtained by the Autodock Tools suite was prepared for molecular dynamics using the GROMOS96 43a1 force field [

30]. The ligand topology was generated using the PRODRG tool. SPC was selected as a solvent model (triclinic water box with size 50 × 75 × 70 Å) for the protein-ligand complex. This system was neutralized by adding sodium or chloride ions depending on the total charges.

For the evaluation of the stability of EiPRMT5-EPZ015666 complex two main parameters were taken into account, RMSD (root mean square deviation) and RMSF (root mean square fluctuation). Molecular dynamics simulation (MSD) was performed in the presence of 0.15 M NaCl using a constant temperature (300 K) and pressure (1.0 bar). The approximate number of frames per simulation was 1000. The RMSD parameter was evaluated using the WebGRO server (

https://simlab.uams.edu), the simulation time was set to 10 ns. CABS-flex version 2.0 (

https://biocomp.chem.uw.edu.pl/lCABSfex2) was used to evaluate the RMSF. The number of cycles was set to 50 and the cycles between trajectory frames were set to 50. The other parameters were set to the default values. Furthermore, molecular dynamic simulation (MDS) was also performed by means of imods [

28], using the default parameters.

4.7. Effect of EPZ015666 on E. invadens Trophozoites

To analyze the effect of EPZ015666 on the viability of trophozoites, 2 × 105 cells were seeded in LYI-S-2 medium in the presence of different concentrations of this drug. After 72 h, the number and viability of trophozoites was determined by trypan-blue dye exclusion in a hematocytometer. As controls, cells were cultured in the absence of the drug or in the presence of DMSO. IC20 and IC50 values were obtained using Graphpad Prism 10 (Graphpad Software Inc.) by constructing a dose-response curve.

To examine the effect of EPZ015666 on sDMA in E. invadens trophozoites, cells were cultured in LYS-S-2 medium in the presence of IC20 and IC50 of the drug or in the presence of DMSO (vehicle) for 72 h. Then, the relative level of sDMA at each time was analyzed by western blot as described above. The relative level of sDMA in trophozoites in the absence of the drug was arbitrary taken as the unit.

4.8. Effect of EPZ015666 on Encystment

Extracts from cells submitted to encystment for 72 h in the absence or presence of DMSO or IC20 of EPZ015666 were analyzed by western blotting and sDMA level was determined as above, arbitrarily taken the relative level of sDMA in the absence of EPZ015666 as 1.

Finally, to analyze the effect of EPZ015666 on cyst formation efficiency, trophozoites undergoing encystment were incubated with IC20 of the drug and the number of sarkosyl-resistant cells was determined at 24, 48 and 72 h.

4.9. Statistics

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation of three to four biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 10.

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest that PRMT5 is a potential target for the development of new therapeutic strategies against the spread of amebiasis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Properties of E. invadens PRMT genes and proteins; Table S2: Comparison between EiPRMTs and EhPRMTs.

Author Contributions

R.O.-H.: Investigation, Methodology, Analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft. E.M.-C.: Methodology, Analysis, Writing—Original Draft. J.B. Methodology, Formal Analysis. S.M.-R.: Methodology, Formal analysis. C.V.-C.: Methodology, Analysis. E.A.-L.: Writing—Review and Editing, Funding acquisition, J.V.: Writing—Review and Editing, Funding acquisition. M.A.R.: Conceptualization, Analysis, Investigation, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencia y Tecnología (CONAHCyT, Mexico), Grant 194163/2020. R.O.-H. was a recipient of a CONAHCyT fellowship (Grant 780474).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data contained within the article are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mario Rodriguez-Nieves for his excellent technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Biggar, K.K.; Li, S.S.-C. Non-Histone Protein Methylation as a Regulator of Cellular Signalling and Function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015, 16, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, M.T.; Clarke, S.G. Protein Arginine Methylation in Mammals: Who, What, and Why. Mol Cell 2009, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stopa, N.; Krebs, J.E.; Shechter, D. The PRMT5 Arginine Methyltransferase: Many Roles in Development, Cancer and Beyond. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015, 72, 2041–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc, R.S.; Richard, S. Arginine Methylation: The Coming of Age. Mol Cell 2017, 65, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuhrmann, J.; Clancy, K.W.; Thompson, P.R. Chemical Biology of Protein Arginine Modifications in Epigenetic Regulation. Chem Rev 2015, 115, 5413–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernzen, K.; Melvin, C.; Yu, L.; Phelps, C.; Niewiesk, S.; Green, P.L.; Panfil, A.R. The PRMT5 Inhibitor EPZ015666 Is Effective against HTLV-1-Transformed T-Cell Lines in Vitro and in Vivo. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullà, A.; Hideshima, T.; Bianchi, G.; Fulciniti, M.; Kemal Samur, M.; Qi, J.; Tai, Y.T.; Harada, T.; Morelli, E.; Amodio, N.; et al. Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5 Has Prognostic Relevance and Is a Druggable Target in Multiple Myeloma. Leukemia 2018, 32, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Penebre, E.; Kuplast, K.G.; Majer, C.R.; Boriack-Sjodin, P.A.; Wigle, T.J.; Johnston, L.D.; Rioux, N.; Munchhof, M.J.; Jin, L.; Jacques, S.L.; et al. A Selective Inhibitor of PRMT5 with in Vivo and in Vitro Potency in MCL Models. Nat Chem Biol 2015, 11, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, J.C.; Read, L.K. Protein Arginine Methylation in Parasitic Protozoa. Eukaryot Cell 2011, 10, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.A. Protein Arginine Methyltransferases in Protozoan Parasites. Parasitology 2022, 149, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, F.-X.; Li, C.-Y.; Li, X.-C.; Chen, L.-F.; Wu, K.; Yang, P.-L.; Lai, Z.-F.; Liu, T.; Sullivan, W.J.; et al. Characterization of Protein Arginine Methyltransferase of TgPRMT5 in Toxoplasma Gondii. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, E.-K.; Hong, Y.; Chung, D.-I.; Goo, Y.-K.; Kong, H.-H. Identification of Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5 as a Regulator for Encystation of Acanthamoeba. Korean J Parasitol 2016, 54, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ximénez, C.; Morán, P.; Rojas, L.; Valadez, A.; Gómez, A. Reassessment of the Epidemiology of Amebiasis: State of the Art. Infection, Genet Evol 2009, 9, 1029–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borbolla-Vázquez, J.; Orozco, E.; Betanzos, A.; Rodríguez, M.A. Entamoeba Histolytica: Protein Arginine Transferase 1a Methylates Arginine Residues and Potentially Modify the H4 Histone. Parasit Vectors 2015, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichinger, D. Encystation of Entamoeba Parasites. BioEssays 1997, 19, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonysamy, S.; Bonday, Z.; Campbell, R.M.; Doyle, B.; Druzina, Z.; Gheyi, T.; Han, B.; Jungheim, L.N.; Qian, Y.; Rauch, C.; et al. Crystal Structure of the Human PRMT5:MEP50 Complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 17960–17965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, M.; Lv, Z.; Yang, N.; Liu, Y.; Bao, S.; Gong, W.; Xu, R.M. Structural Insights into Protein Arginine Symmetric Dimethylation by PRMT5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 2041–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewary, S.K.; Zheng, Y.G.; Ho, M.-C. Protein Arginine Methyltransferases: Insights into the Enzyme Structure and Mechanism at the Atomic Level. Cell Mol Life Sci 2019, 76, 2917–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motolani, A.; Martin, M.; Sun, M.; Lu, T. The Structure and Functions of Prmt5 in Human Diseases. Life 2021, 11, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapira, M.; Ferreira De Freitas, R. Structural Biology and Chemistry of Protein Arginine Methyltransferases. Medchemcomm 2014, 5, 1779–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.-C.; Wilczek, C.; Bonanno, J.B.; Xing, L.; Seznec, J.; Matsui, T.; Carter, L.G.; Onikubo, T.; Kumar, P.R.; Chan, M.K.; et al. Structure of the Arginine Methyltransferase PRMT5-MEP50 Reveals a Mechanism for Substrate Specificity. PLoS One 2013, 8, e57008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternack, D.A.; Sayegh, J.; Clarke, S.; Read, L.K. Evolutionarily Divergent Type II Protein Agrinine Methyltransferase in Trypanosoma Brucei. Eukaryot Cell 2007, 6, 1665–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; He, J.Z.; Mao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, W.W.; Duan, S.; Jiang, A.; Gao, Y.; Sang, Y.; Huang, G. EPZ015666, a Selective Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) Inhibitor with an Antitumour Effect in Retinoblastoma. Exp Eye Res 2021, 202, 108286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, B.; Benavides-Serrato, A.; Saunders, J.T.; Landon, K.A.; Schreck, A.J.; Nishimura, R.N.; Gera, J. The Protein Arginine Methyltransferase PRMT5 Confers Therapeutic Resistance to MTOR Inhibition in Glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 2019, 145, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, S.; Liu, F.; Veazey, K.J.; Gao, G.; Das, P.; Neves, L.F.; Lin, K.; Zhong, Y.; Lu, Y.; Giuliani, V.; et al. Genetic Deletion or Small-Molecule Inhibition of the Arginine Methyltransferase PRMT5 Exhibit Anti-Tumoral Activity in Mouse Models of MLL-Rearranged AML. Leukemia 2018, 32, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Amado, D.; Herrera-Solorio, A.M.; Valdés, J.; Alemán-Lazarini, L.; Almaraz-Barrera, Ma. de J.; Luna-Rivera, E.; Vargas, M.; Hernández-Rivas, R. Identification of Repressive and Active Epigenetic Marks and Nuclear Bodies in Entamoeba Histolytica. Parasit Vectors 2016, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Blanco, J.R.; Aliaga, J.I.; Quintana-Ortí, E.S.; Chacón, P. IMODS: Internal Coordinates Normal Mode Analysis Server. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42 (web server issue), W271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.B.; Holder, A. J Gauss View 5.0, User´s Reference; Pittsurgh, 2009.

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindah, E. Gromacs: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).