Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

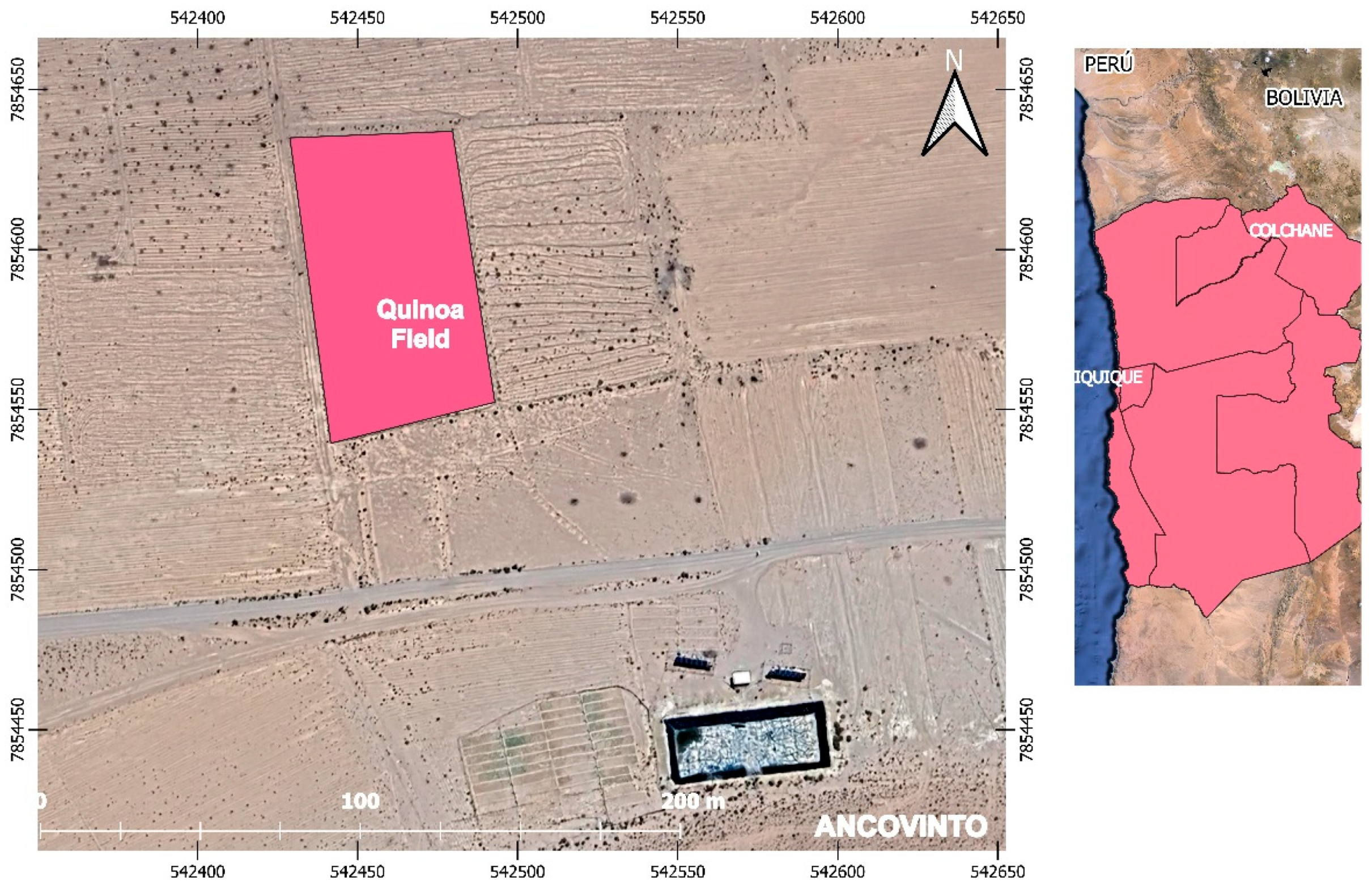

2.1. Definition of the Study Site

2.2. Vegetal Material

2.3. Climate Data

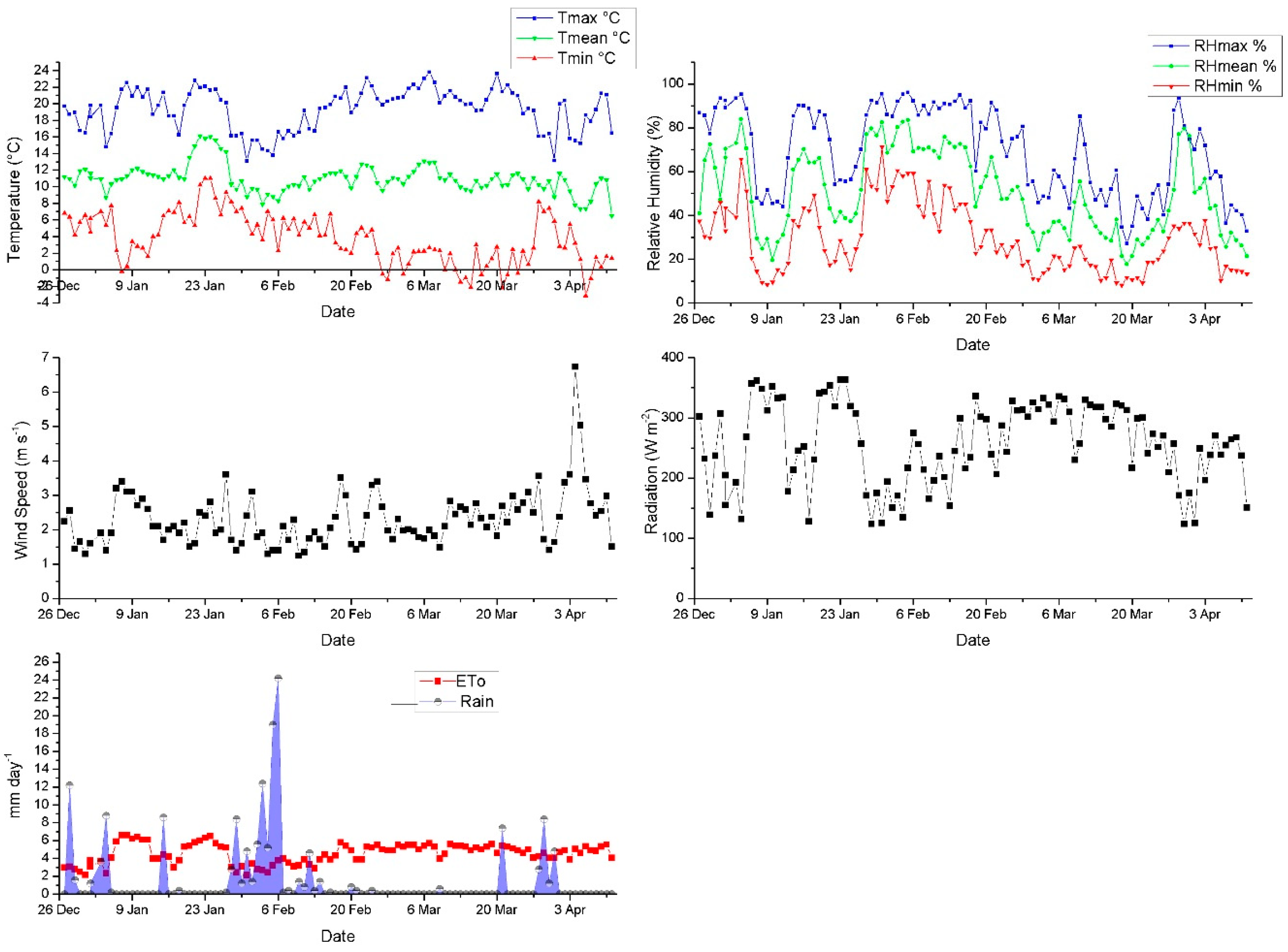

2.4. Climate Variables

2.5. Experimental Design

| Treatment | % ETc | Applied mm |

| T0 | rainfed | 127 = 127 L/m2 |

| T1 (control) | 100 | 576 = 576 L/m2 |

| T2 | 66,6 | 423 = 423 L/m2 |

| T3 | 33,3 | 275 = 275 L/m2 |

2.6. Analysis of Physicochemical Parameters

2.8. Soil Moisture Measurement

2.9. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) Measurement

2.9. Water Accounting and Productivity

2.10. Analysis of Agromorphological Parameters

3. Results and Discussion

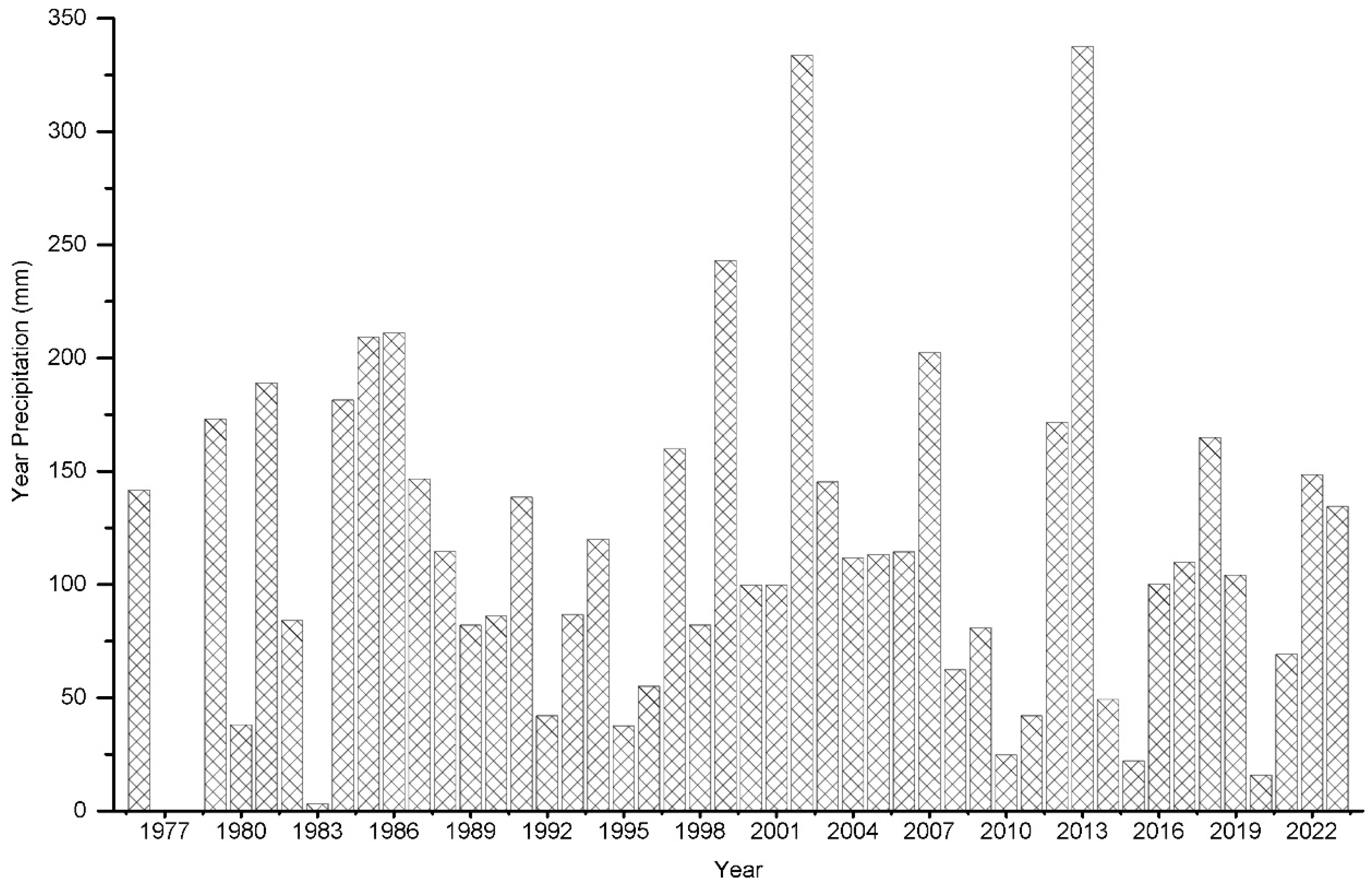

3.1. Analysis of Climatic Variables in the Study Sites

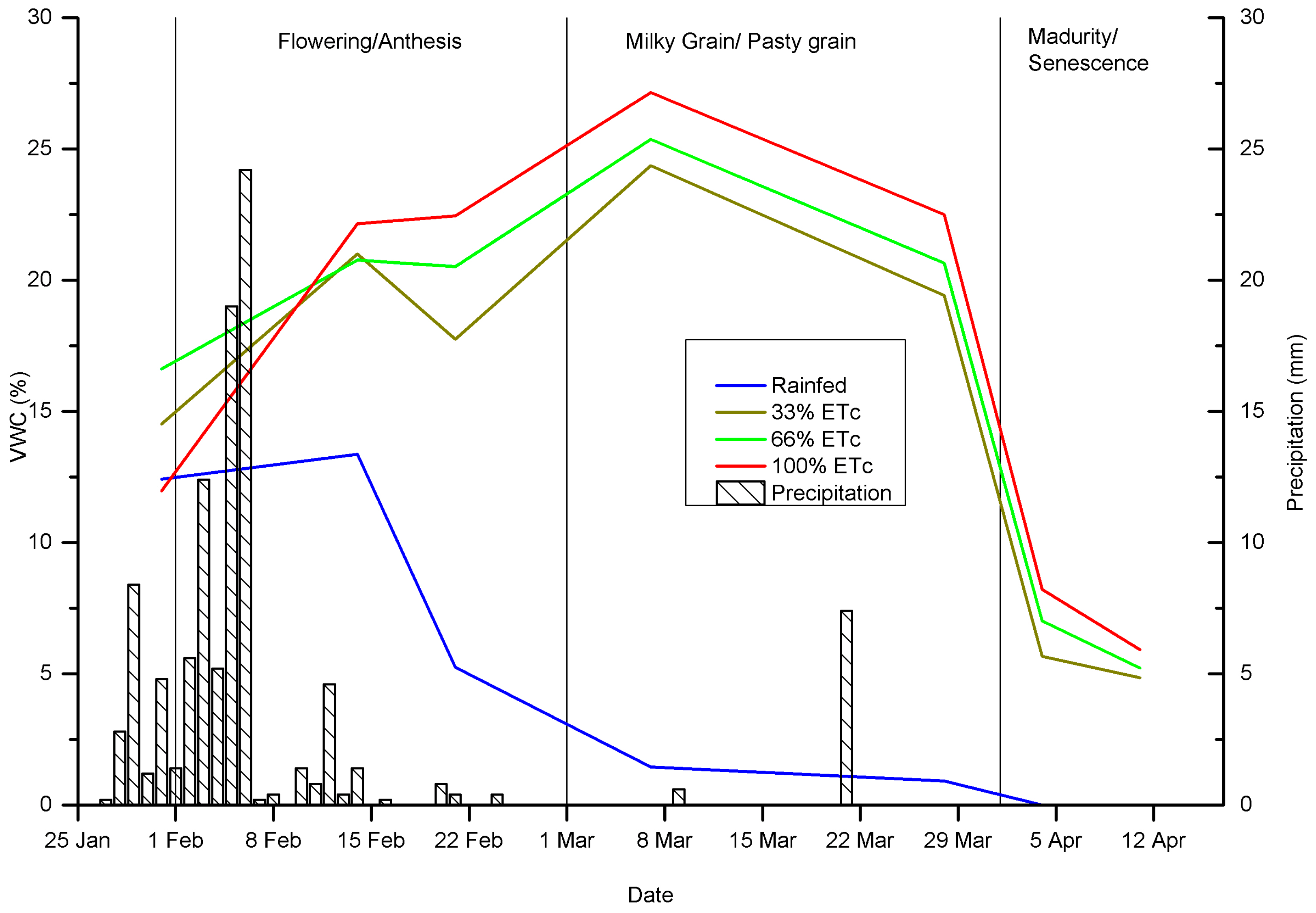

3.2. Volumetric Water Content (VWC) of the Soil at the Research Location

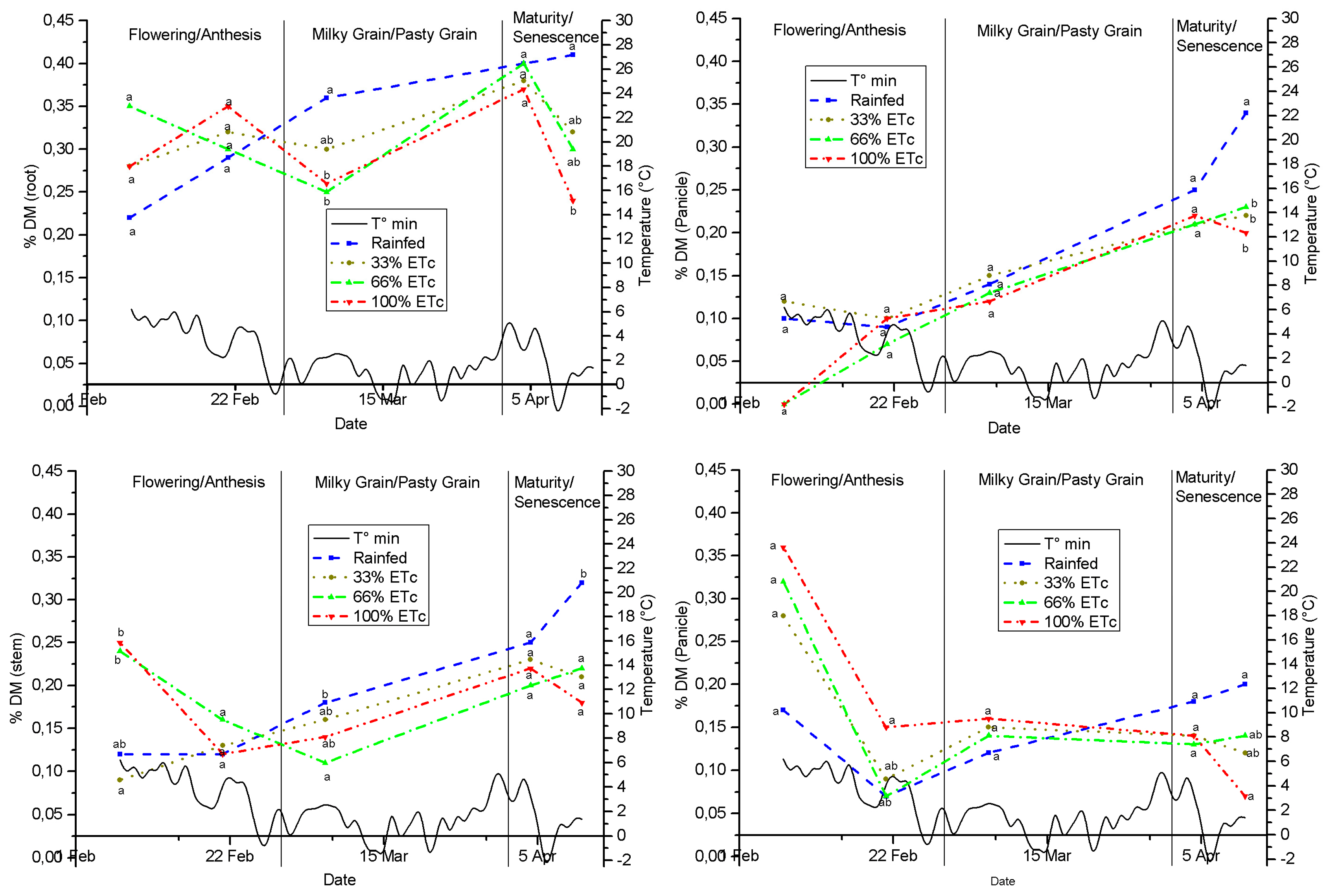

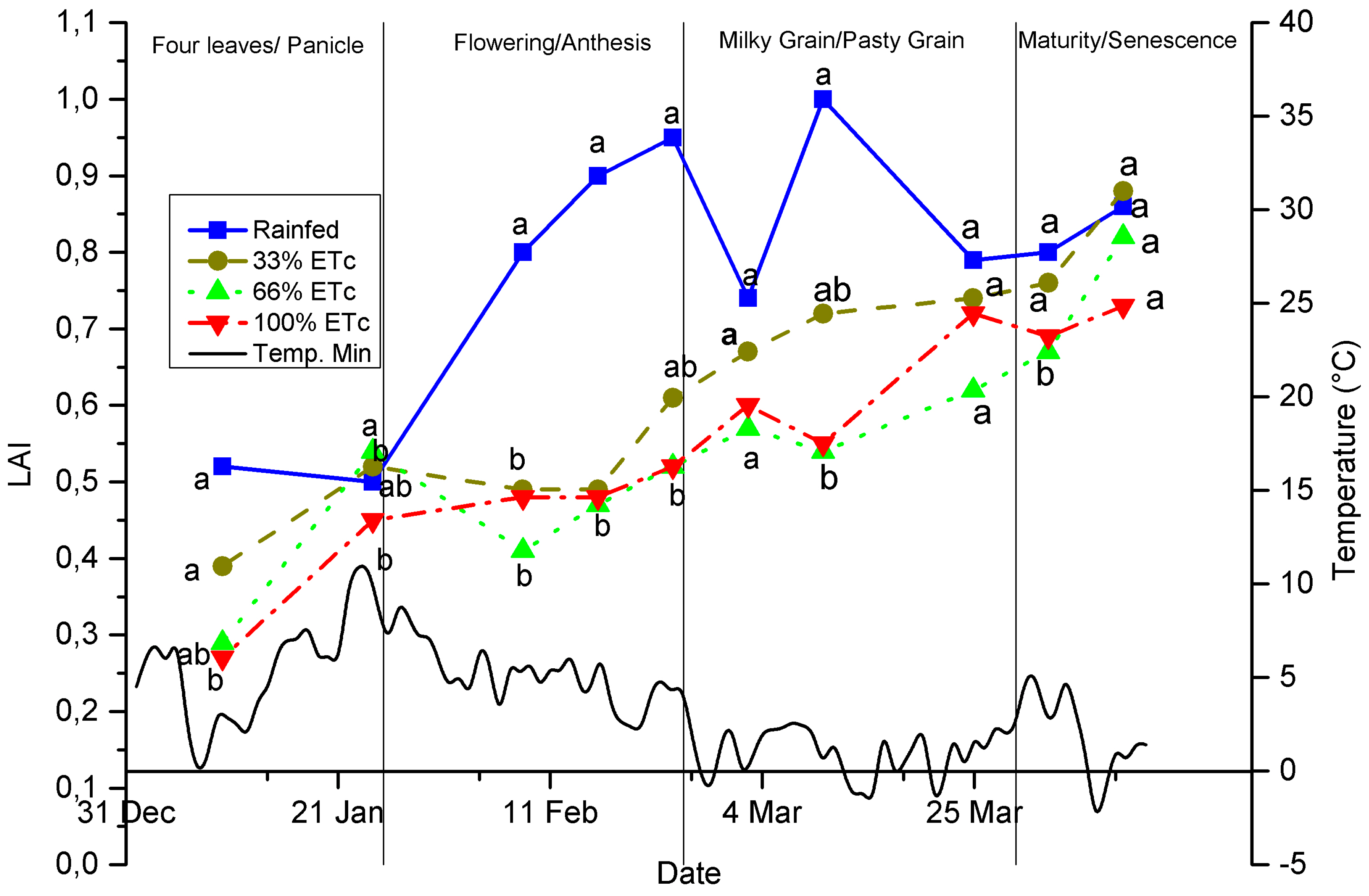

3.2. Dry matter Production of Leaf, Stem, Root, Leaf Area Index and Height of Quinoa Plants

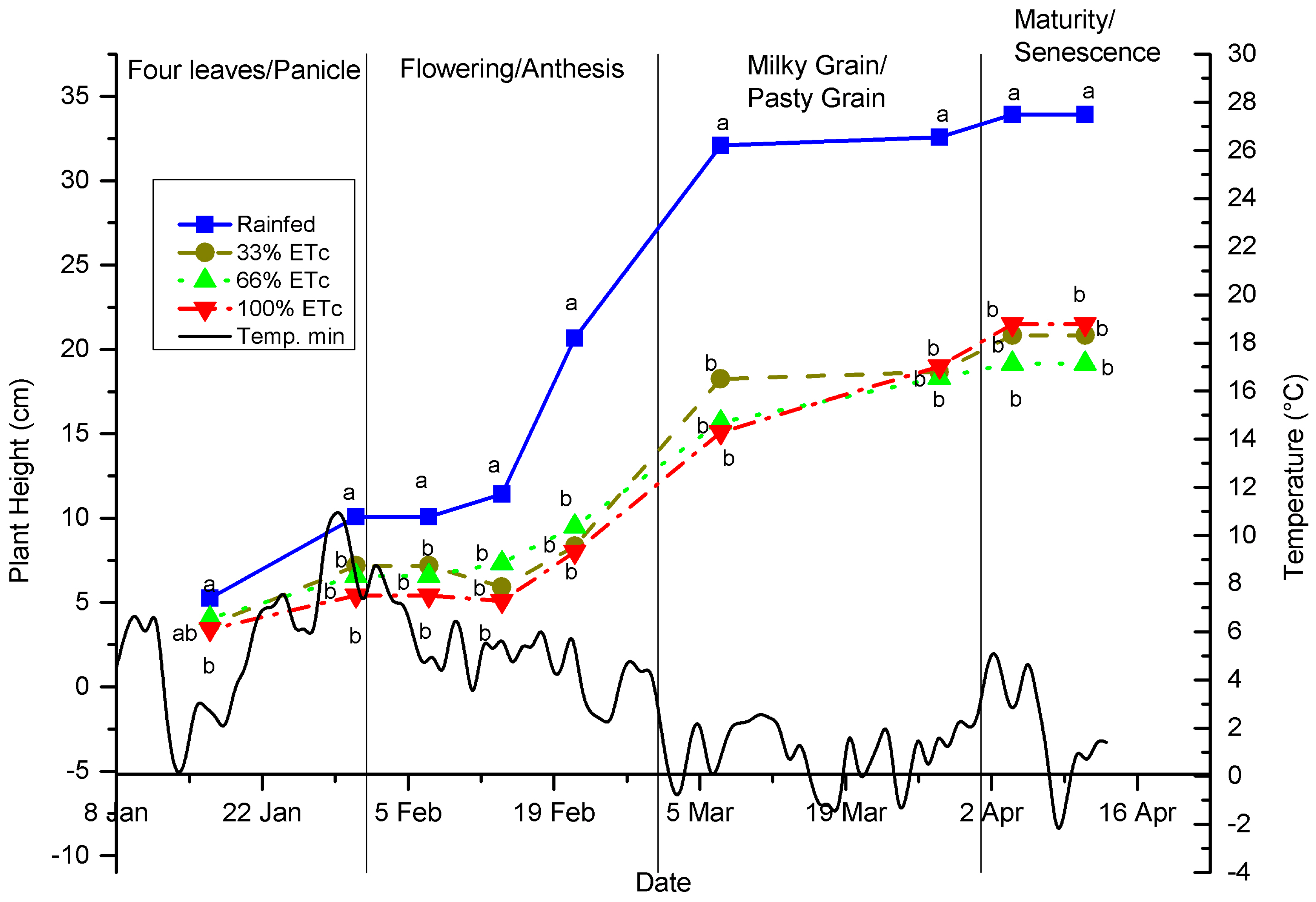

3.3. Plant Height

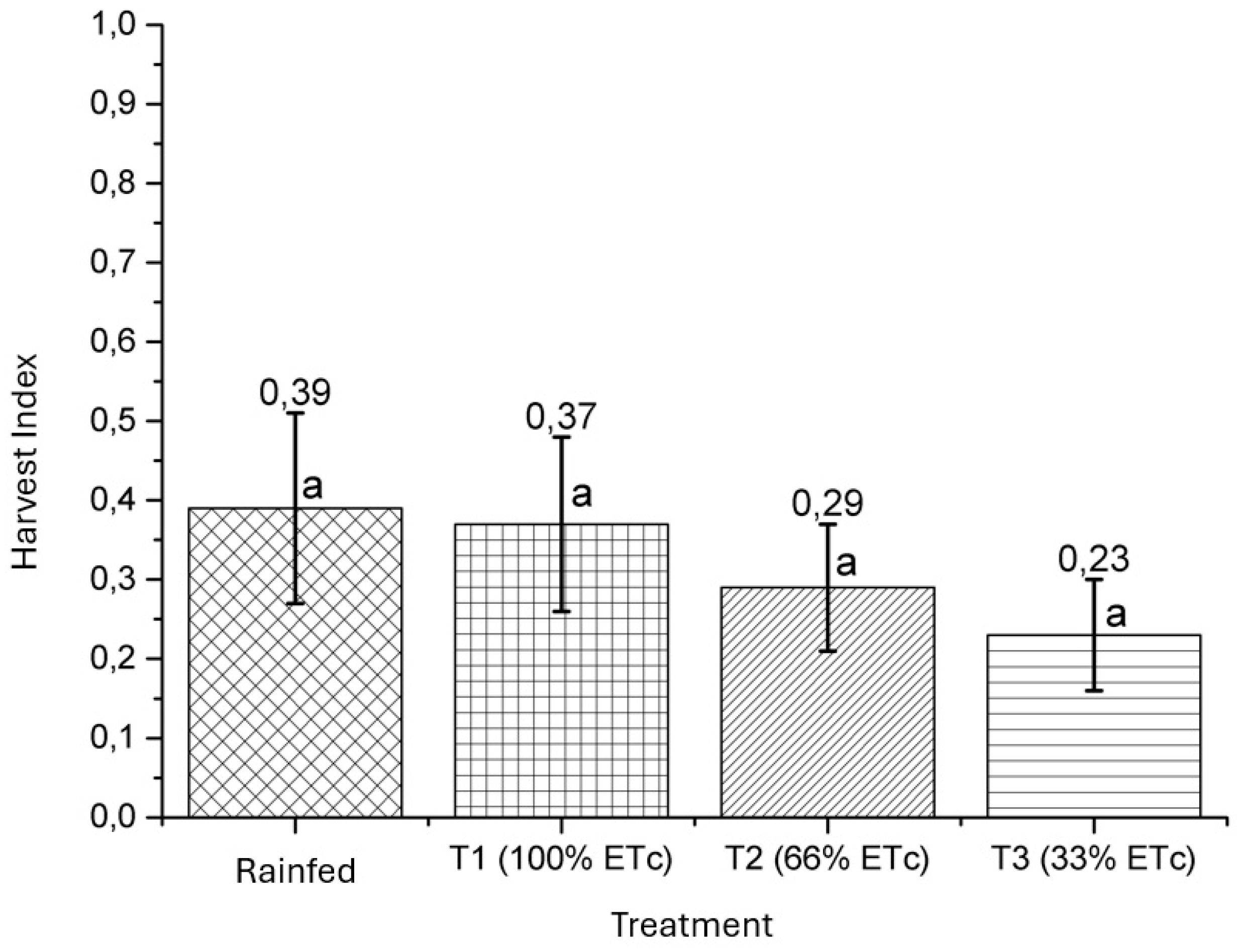

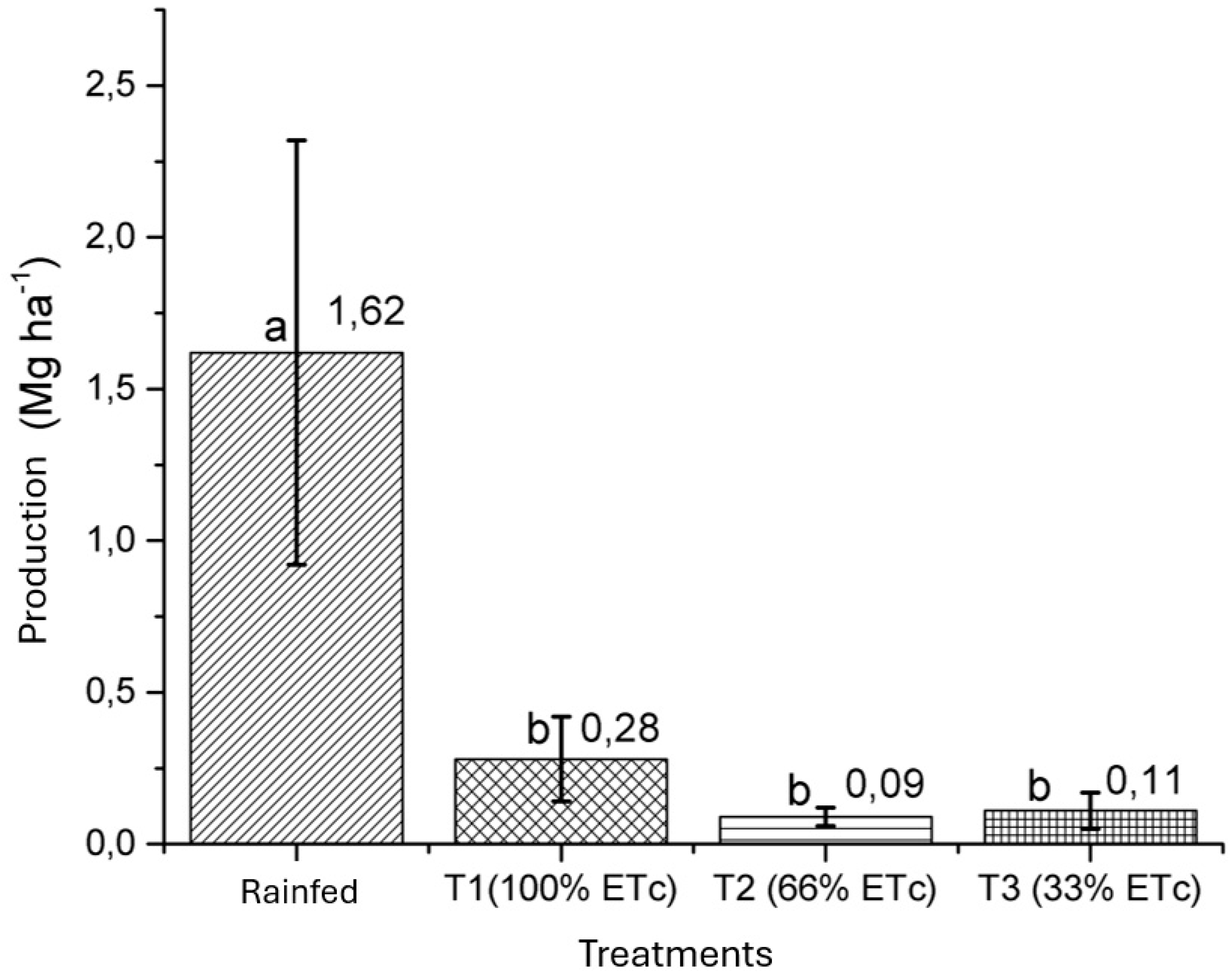

3.4. Harvest Index (HI) and Production

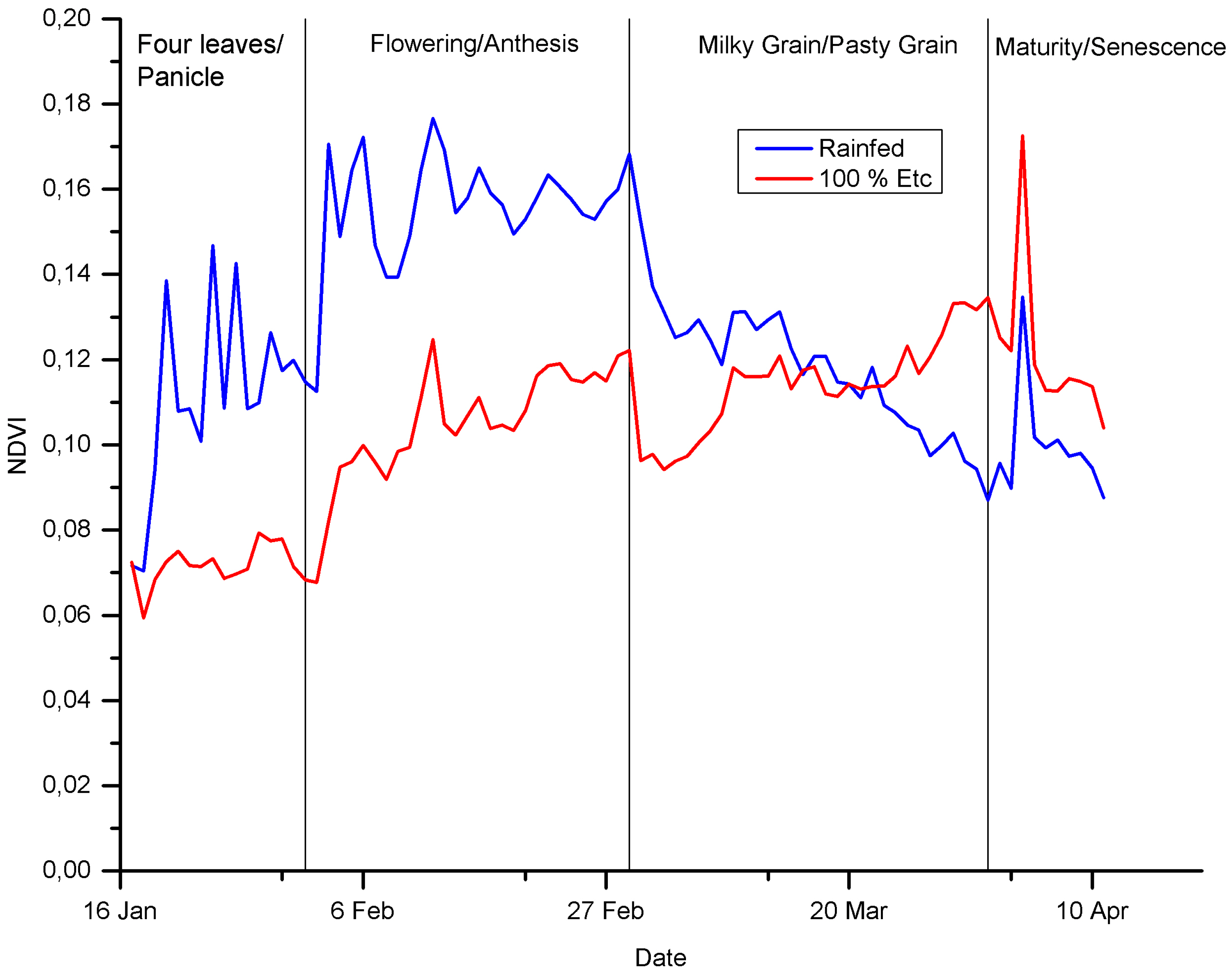

3.5. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

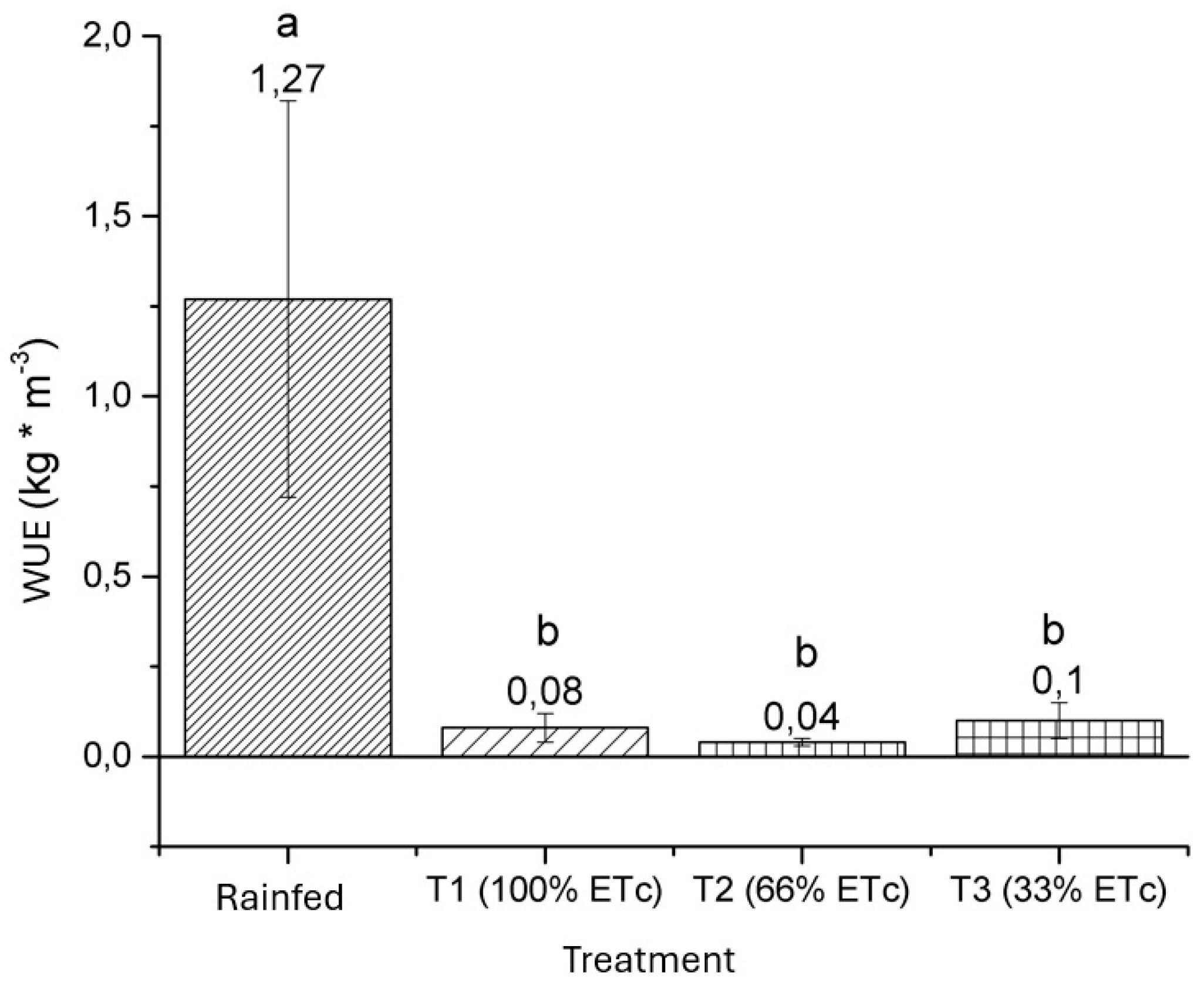

3.6. Water Use Efficiency (WUE)

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valdivia, C.; Thibeault, J.; Gilles, J.L.; García, M.; Seth, A. Climate trends and projections for the Andean Altiplano and strategies for adaptation. Adv. Geosci. 2013, 33, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, E.B. Impacto económico del cambio climático en cultivo de quinua ( chenopodium quinoa willd ) orgánica en la región del Altiplano : un enfoque Ricardiano Impact economic of climate change on crop of organic quinua in the Altiplano Region : a Richardian approac. 2021, 23, 236–243. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, P.C.; Jacobsen, S. Cultivation of Quinoa on the Peruvian Altiplano Cultivation of Quinoa on the Peruvian Altiplano. 2006, 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Geerts, S.; Raes, D.; Garcia, M.; Del Castillo, C.; Buytaert, W. Agro-climatic suitability mapping for crop production in the Bolivian Altiplano: A case study for quinoa. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2006, 139, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bois, J.F.; Winkel, T.; Lhomme, J.P.; Raffaillac, J.P.; Rocheteau, A. Response of some Andean cultivars of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) to temperature: Effects on germination, phenology, growth and freezing. Eur. J. Agron. 2006, 25, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas (INE) Censo. Gob. Chile 2002, 4–9.

- CIDERH Observatorio del Agua.

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. 1998, 56, 323.

- Choquecallata, J.; Valcher, J.; Fellmann, T.; Imaña, E. Evapotranspiración Maxima del Cultivo de la Quinua por Lisimetría y su relación con la Evapotraspiración Potencial en el Altiplano Boliviano. In Proceedings of the Congreso Internacional sobre Cultivos Andinos; Morales, D., Vacher, J., Eds.; La Paz, Bolivia, 1991; pp. 63–67.

- Brahmakshatriya, R.D.; Donker, J.D. Five Methods for Determination of Silage Dry Matter. J. Dairy Sci. 1971, 54, 1470–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hühn, M. Comments on the Calculation of Mean Harvest Indices. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 1990, 165, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarricolea Espinoza, P.; Romero Aravena, H. Variabilidad y cambios climáticos observados y esperados en el Altiplano del norte de Chile. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2015, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olave, J.; Sanchez-Monje, M.; Aguilera, J.; Araya, P. Riego Suplementario del Cultivo de la Quinua en el Altiplano de la Región la de Tarapacá; UNAP – Uni.; Iquique, 2019; ISBN 978 956 302 110 - 3.

- Jacobsen, S.; Monteros, C..; Christiansen, J.; Bravo, L.; Corcuera, L.; Mujica, Á. Plant responses of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) to frost at various phenological stages. Eur. J. Agron. 2004, 22, 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Hirich, A. Effects of Deficit Irrigation using Treated Wastewater and Irrigation with Saline Water on Legumes, Corn and Quinoa Crops. Res. Unit Hortic. Prod. 2017, 1, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.E.; Monteros, C.; Corcuera, L.J.; Bravo, L.A.; Christiansen, J.L.; Mujica, A. Frost resistance mechanisms in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 26, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocozza, C.; Pulvento, C.; Lavini, A.; Riccardi, M.; D’andria, R.; Tognetti, R. Effects of Increasing Salinity Stress and Decreasing Water Availability on Ecophysiological Traits of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Grown in a Mediterranean-Type Agroecosystem. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2013, 199, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoutar, F.; Abdelaziz, H.; Ouafae, B.; Redouane, C.A.; Ragab, R. Yield and Dry Matter Simulation Using the Saltmed Model for Five Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa) Accessions Under Deficit Irrigation in South Morocco. Irrig. Drain. 2017, 66, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Huang, T.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Qin, P. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis of the Response of Quinoa Seedlings to Low Temperatures. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.; Jacobsen, S.-E.; Andersen, M..; Núñez, N.; Andersen, S..; Rasmussen, L.; Mogensen, V. Leaf gas exchange and water relation characteristics of field quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) during soil drying. Eur. J. Agron. 2000, 13, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.P.; Ono, E.; Abdullah, A.M.S.; Choukr-Allah, R.; Abdelaziz, H. Cultivation of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) in Desert Ecoregion. 2020, 145–161. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, F.; Maughan, P.; Jellen, E.R. Diversidad genetica y recursos geneticos para el mejoramiento de la quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) (Genetic diversity and genetic resources for quinoa breeding). Rev. Geográfica Valparaíso 2009, 42, 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pathan, S.; Ndunguru, G.; Clark, K.; Ayele, A.G. Yield and nutritional responses of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) genotypes to irrigated, rainfed, and drought-stress environments. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, L.; Kumar, N.; Gill, K.S.; Murphy, K.M. Spectral reflectance indices and physiological parameters in Quinoa under contrasting irrigation regimes. Crop Sci. 2019, 59, 1927–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, S.; Raes, D.; Garcia, M.; Vacher, J.; Mamani, R.; Mendoza, J.; Huanca, R.; Morales, B.; Miranda, R.; Cusicanqui, J.; et al. Introducing deficit irrigation to stabilize yields of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Eur. J. Agron. 2008, 28, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehan, G.; Abdel-Ghany-Nagdy, H. Impact of Soil Heat Flux on Water Use of Quinoa. Ann. Agric. Sci. Moshtohor 2019, 57, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar]

| 2018-2019 | Daily ET0 (mm/day) | Kc* | Daily ETc (mm/day) | Phenological Phase* |

| December -January | 4,7 | 0,58 | 2,7 | Four true leaves |

| January | 4,7 | 0,63 | 3,0 | Panicle initiation |

| January | 4,7 | 0,73 | 3,4 | Panicle |

| January | 4,7 | 0,90 | 4,2 | Flowering beginning |

| February | 4,1 | 1,01 | 4,1 | Flowering or anthesis |

| February | 4,1 | 1,08 | 4,4 | Flowering or anthesis |

| March | 5,1 | 1,14 | 5,8 | Milky grain beggining |

| March | 5,1 | 1,00 | 5,1 | Milky grain end |

| April | 5,0 | 0,78 | 3,9 | Mushy grain |

| Area | Textural type | Depth | Organic matter* | Bulk density | Clay | Silt | Sand | Field capability | Permanent wilting point | Available moisture** |

| (cm) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | a -0,01Mpa (vol.%) | a -1,55MPa (vol.%) | (peso) (%) | |||

| Ancovinto | Sandy loam | 0-30 | 0,51 | 1,76 | 14 | 13 | 73 | 10,5 | 5,2 | 5,3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).