Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Big Picture Problem

If you take the hype and PR at face value over the last 10 years, you would think it goes from five percent to 90 percent. But if you know how these models work, it goes from five percent to maybe six or seven percent.Patrick Malone, KdT Ventures

- Generating/deriving (e.g. from images etc.) and analysing existing data

- Designing structures of bioactive agents, across modalities

- Designing in vitro experiments (where data is needed to establish predictive value of experiments)

- Understanding and modelling biological mechanisms

- Summarising information across literature and study reports

- The elephant in the room is large language models - commonly called LLMs. This is the ChatGPT-like [6] environment that we have become rapidly familiar with over the last couple of years. In principle, LLMs could change the world of drug discovery (as they are often claiming to do), but biology and chemistry and derived data are full of nuances [7] and the expectations for how LLMs will actually impact drug discovery need to be kept reasonably low for the moment. Approaches such as neuro-symbolic reasoning [8] may be able to overcome some of the current, and inherent, challenges of LLMs [9].

- Another big field of advancement is protein modelling and simulation. There are several technologies and specific tools being rolled out in this area. The latest exciting advancement is AlphaFold 3, which was just released [10]. AlphaFold 3 has been built to model DNA, RNA and smaller molecules (ligands) [11], and various open source implementations of this and related approaches have followed, such as HelixFold [12] and others, which aimed to address the non-availability of AlphaFold3 to the public.

- The third area is predictive modelling (including both machine learning statistical techniques). This is a traditional application for AI (including machine learning). These methods are extensions of classical statistical techniques that we learnt at school, such as linear regression (fitting a straight line to data points). The big advancement over the last two to three decades has been the power of the new algorithms, which leverage cheap compute processing and storage (Moore’s Law), and in some areas also cheap data generation (for example, $100 whole genome sequencing). However, life science data is fundamentally different from elsewhere when it comes to clinically relevant endpoints, as described previously [13].

- AI technologies cannot work their magic without sufficient quality curated data, and generating such data is challenging - especially with in vitro lab tests. According to a prominent article ten years back [14] data scientists spend up to 80 percent of their time mired in the mundane labour of collecting and preparing unruly digital data, before it can be explored for useful nuggets. There are academics and companies actively working on solving this challenge, but biology and chemistry is hard and lab data is often messy and irreproducible. To learn the basics of data quality, a good start is the 7 C’s framework [15].

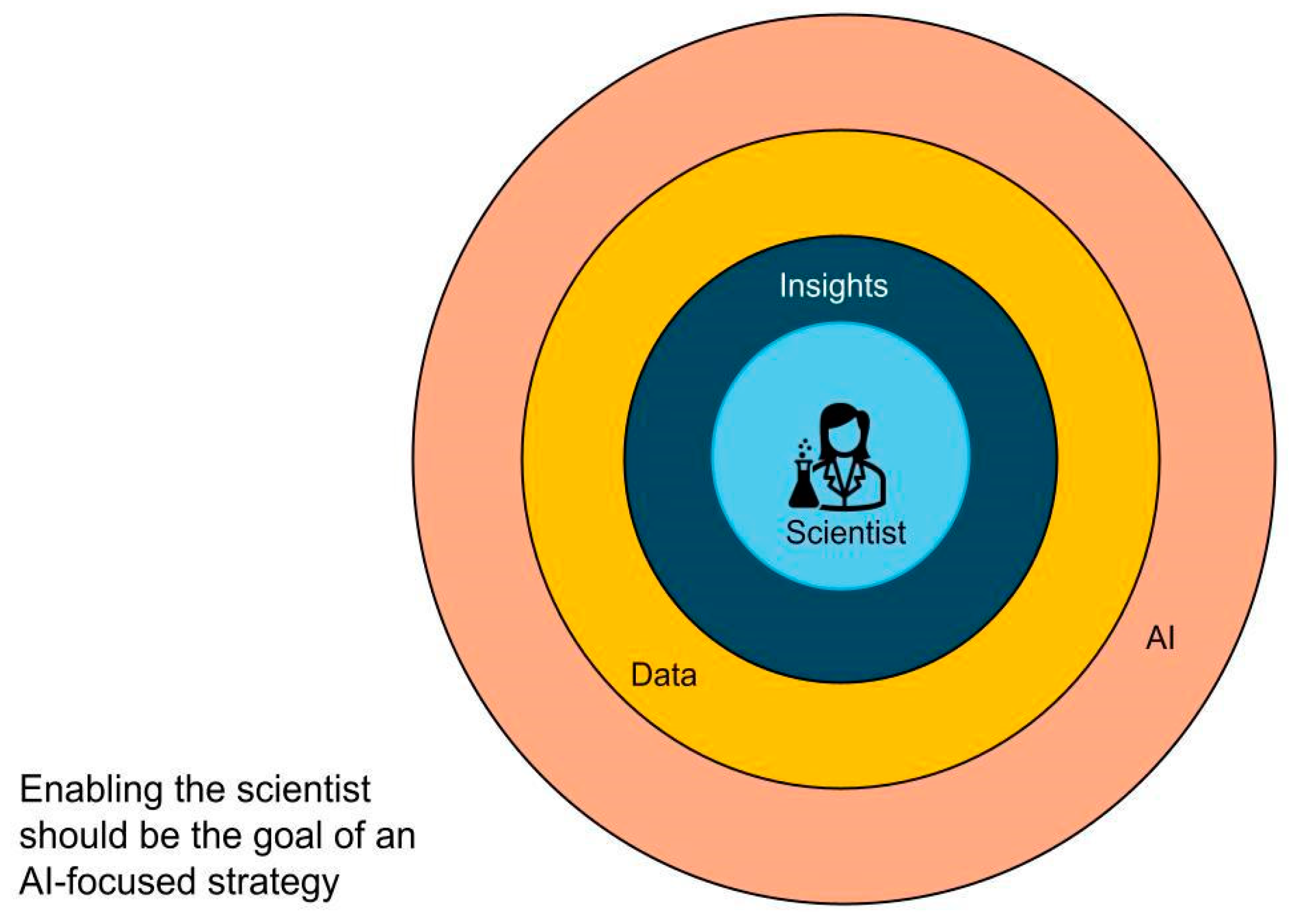

- Assess your data quality and utility and develop a data build vs buy strategy. Some limited knowledge of AI/statistical techniques will be needed for this, as it affects the utility calculation; this knowledge can be gained through experienced advisors.

- Develop a both short-term and longer-term computational strategy that leverages current data and planned new data. Be open to paying for datasets and tools, and even look at open-source software if you have the in-house software skills. Each phase of the strategy should be targeted at helping answer key scientific questions that your investors are expecting you to answer.

2. Voice of Industry

2.1. Navigating Scepticism and Embracing AI

2.2. Communication: The Key to Overcoming Barriers

There is a disconnect between individual scientific achievement and collective organisational goals. High-ranking scientists are often celebrated for their groundbreaking research but are not held accountable for ensuring their work is reproducible or that it benefits the broader scientific community.Mr Conway, CEO, 20/15 Visioneers

2.3. Understanding Biotech’s Board Commitments

The pressure comes from improving efficiencies to deliver on these milestones as quickly as possible. For vendors and tech partners working with biotech companies, understanding these milestones is key to aligning their services and helping accelerate the drug discovery process.Dr Wilkie, CEO Mironid Ltd

2.4. Managing Scientific Data Complexity in Small Biotechs

You’ve got this mass amount of data, and how do you move it around? How do you even access it easily? And then, what do you do with it? This challenge is compounded by the increasing complexity of biological data, particularly in imaging, which often contains hidden insights that are difficult to extract without advanced computational tools.Dr Thomas, CEO, Five Alarm Biosciences

2.5. The Untapped Potential of Automation and AI

2.6. Data as Intellectual Property

3. The Impact of Culture

3.1. The Cultural Landscape in Drug Discovery

3.2. Addressing Cultural Challenges

4. Data Quality and Its Impact

4.1. An Introduction to Data Quality and the Need for Data Scientists

- a measurement issue from a lab machine - e.g. missing data in a csv file

- a poorly designed experiment - related to both predictivity for the final human-relevant effect one wants to predict, as well as e.g. too much variability in the data

- poor data from non-controlled environments - e.g. observation data from human studies

4.2. The Impact of Poor Data Quality

- Irrelevant data for a given purpose - leading to the generation of machine learning models that predict other endpoints than those needed for decision making in practice (hence in the worst case even being misleading as a result)

- Incomplete data can cause ML models to miss patterns or relationships. For example, if crucial bioactivity data for certain compounds is missing, the model may not fully account for the structure-activity relationships, leading to inaccurate predictions.

- Inconsistencies, such as variations in how data is recorded (eg, different units of measurement or naming conventions), can confuse models and lead to erroneous predictions. For instance, if the same compound is labelled differently in different datasets (due to a different tautomer, salt form, there are many reasons why this can happen), the model might treat it as different entities, skewing the results.

- Bias in data can lead to models that are not generalisable or that perform poorly on certain subsets of data. For instance, if your training data is biased toward a particular chemical scaffold or a specific set of biological targets, the model will be less effective in predicting the activity of compounds outside these categories.

- Noise in data, which may arise from experimental errors, variability in biological assays, or inconsistent conditions, can obscure true signals and reduce the model's ability to learn relevant patterns. This can result in a higher rate of false positives or negatives.

- Duplicate records and redundant features or data points can inflate the dimensionality of the data without adding new information, leading to overfitting and reduced model performance.

- Scientific reproducibility is compromised when data quality is poor, as other researchers or systems might not replicate the findings.

5. Guidelines to Handle Data Quality Issues

6. Practises to Address Cultural Challenges Impacting Data Quality

7. Way forward - The HitchhikersAI Community [Raminderpal]

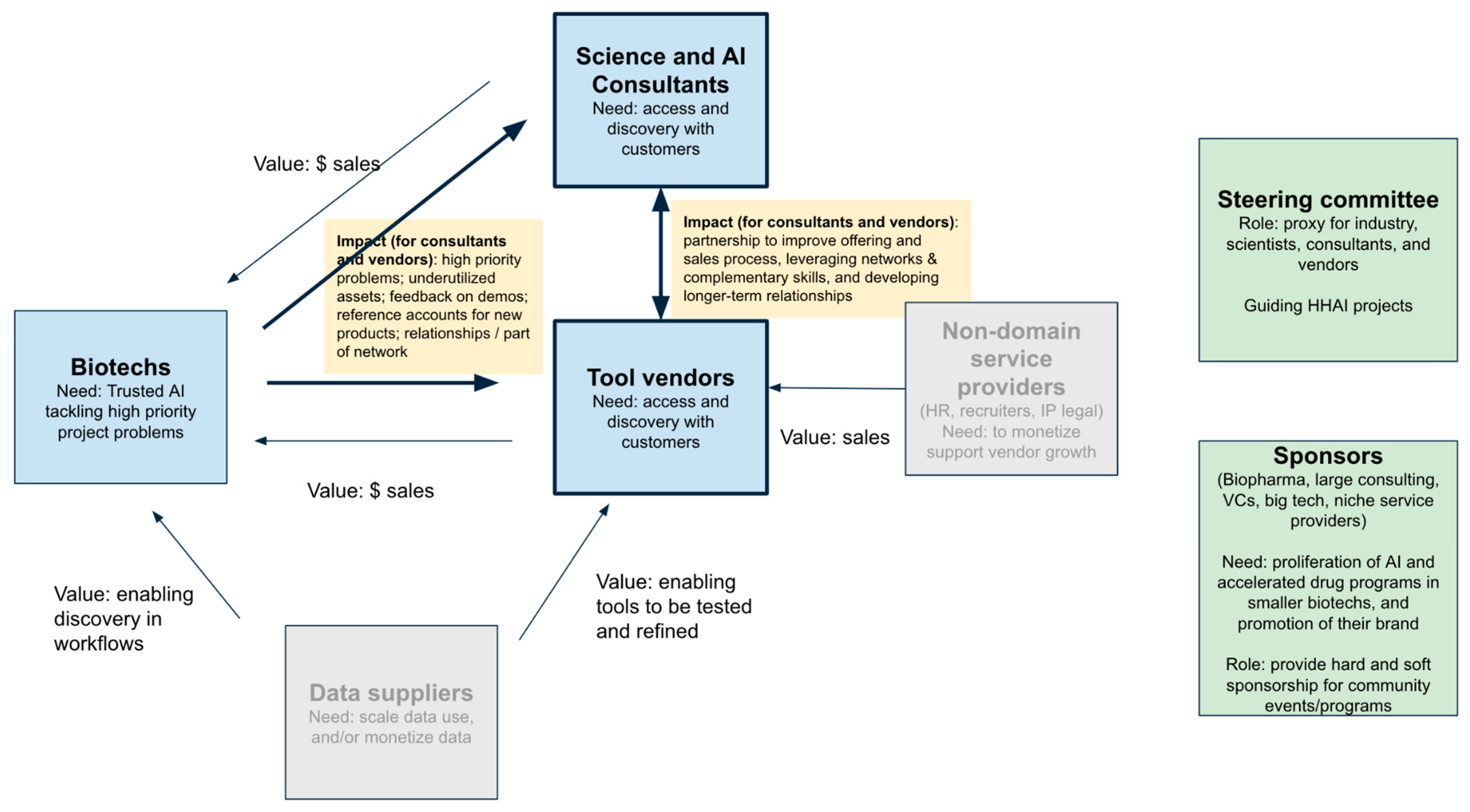

- Scientists and biotechs have not been motivated to participate in the HitchhikersAI, as direct value not clear to them - it does not seem to help them in their day-job and high priority challenges.

- The vendors most interested in HitchhikersAI are those in market discovery mode - early monetization, learning the voice of the customer, product-market-fit, new to the drug discovery world etc.

- The sole focus on early drug discovery is limiting the amount of vendors who could participate, because only a relatively few vendors are enabled enough to focus on early drug discovery.

- Market feedback (e.g. from biopharma exec talks at Bio Europe 2023) strongly pushing AI vendors to support late stage drug discovery needs.

- There are many science and AI consultants who would also participate if they could be helped.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Interests

References

- Dunn, A. Endpoints News. After years of hype, the first AI-designed drugs fall short in the clinic. [Internet] 2023 [updated 2023 October 19; cited 2024 April]. Available online: https://endpts.com/first-ai-designed-drugs-fall-short-in-the-clinic-following-years-of-hype/.

- Cross R, Dunn A. Endpoints News. Exclusive: In $1B+ bet on AI, biopharma heavyweights back new startup to upend drug R&D. [Internet] 2024 [updated 2024 April 23; cited 2024 April]. Available online: https://endpts.com/in-biggest-ever-bet-on-using-ai-to-design-drugs-biotech-heavyweights-launch-xaira-with-1b-in-backing/.

- Buntz, B. Drug Discovery & Development. 20 biotech startups attracted almost $3B in Q1 2024. [Internet] [2024 April 5, cited 2024 April]. Available online: https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/20-biotech-startups-attracted-almost-3b-in-q1-2024-funding/.

- Moore GA, McKenna R. 1999. Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling high-tech Products to Mainstream Customers. Harper Collins.

- Randall, T. Where is Tesla’s EV competition? The Economic Times [Internet] 2023 [updated 2023 October 5, cited 2024 April]. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/renewables/where-is-teslas-ev-competition/articleshow/104193382.cms?from=mdr.

- Wikipedia. ChatGPT [Internet] 2024 [updated 2024 May 12; cited 2024 May]. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ChatGPT.

- Bender A, Cortés-Ciriano I. Artificial intelligence in drug discovery: what is realistic, what are illusions? Part 1: Ways to make an impact, and why we are not there yet. 2020. Drug Discovery Today. 26(2): 511–524. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33346134/.

- DeLong LN, Mir RF, Fleuriot JD. Neurosymbolic AI for Reasoning over Knowledge.

- Graphs: A Survey. Arxiv.org [Internet] 2023 [updated 2024 May 16; cited 2024 September]. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.07200.

- Saba, W. No Generalization without Understanding and Explanation. Communications of the ACM [Internet] 2024 [updated 2024 Sep 20; cited 2024 September]. Available online: https://cacm.acm.org/blogcacm/no-generalization-without-understanding-and-explanation/.

- Howe NP, Thompson B. Alphafold 3.0: the AI protein predictor gets an upgrade. Nature [Internet] 2024 [updated 2024 May 8; cited 2024 May]. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-01385-x.

- Emilia David. Google DeepMind’s new AI can model DNA, RNA, and ‘all life’s molecules’. The Verge [Internet] 2024 [updated 2024 May 8; cited 2024 May]. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2024/5/8/24152088/google-deepmind-ai-model-predict-molecular-structure-alphafold.

- Liu L, Zhang S, Xue Y, Ye X, Zhu K, Li Y et al. Technical Report of HelixFold3 for Biomolecular Structure Prediction. Arxiv.org [Internet] 2024 [updated 2024 September 9; cited 2024 September]. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.16975.

- Bender A, Cortés-Ciriano I. Artificial intelligence in drug discovery: what is realistic, what are illusions? Part 2: a discussion of chemical and biological data. 2021. Drug Discovery Today. 26(4): 1040-1052. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33508423/.

- Lohr, S. For Big-Data Scientists, ‘Janitor Work’ Is Key Hurdle to Insights. The New York Times [Internet] 2014 [updated 2024; cited 2024 May]. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/18/technology/for-big-data-scientists-hurdle-to-insights-is-janitor-work.html.

- Agre JR, Gordon KD, Vassiliou MS. The Seven C’s of Data Curation for the Two C’s – Command and Control. Institute for Defense Analyses [Internet] 2015 [updated 2015 February; cited 2024 May]. Available online: https://www.ida.org/research-and-publications/publications/all/t/th/the-seven-cs-of-data-curation-for-the-two-cscommand-and-control.

- Ghiandoni GM, Evertsson E, Riley DJ, Tyrchan C, Rathi PC. 2024. Augmenting DMTA using predictive AI modelling at AstraZeneca. Drug Discovery Today. 29(4): 103945. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38460568/.

- Narain, NR. AI Isn’t the Magic Bullet to Simplify Drug Discovery. Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News [Internet] 2024 [updated 2024 June; cited 2024 September]. Available online: https://www.genengnews.com/bioperspectives/ai-isnt-the-magic-bullet-to-simplify-drug-discovery/.

- Biehler, K. The need for a data-driven culture in life sciences: What you don’t know can hurt you. Pharmaceutical Processing World [Internet] 2023 [updated 2023 May; cited 2024 September]. Available online: https://www.pharmaceuticalprocessingworld.com/the-need-for-a-data-driven-culture-in-life-sciences-what-you-dont-know-can-hurt-you/.

- Max Planck Digital Library. Data Quality [Internet] [cited 2024 September]. Available online: https://rdm.mpdl.mpg.de/before-research/data-quality/.

- Scannell JW, Bosley J, Hickman JA, Dawson GR, Truebel H, Ferreira GS et al. 2022. Predictive validity in drug discovery: what it is, why it matters and how to improve it. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 21(12):915-931. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36195754/.

- Hardy K, Heyse S (2023). FAIR data policies can benefit biotech startups. Nature biotechnology. 41: 1060–1061. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-023-01892-8.

- Truong T, George R, Davidson J. Establishing an Effective Data Governance System. Pharmaceutical Technology. [Internet] 2017 [updated 2017 November 2, cited 2024 September]. Available online: https://www.pharmtech.com/view/establishing-effective-data-governance-system.

- Ulrich H, Kock-Schoppenhauer AK, Deppenwiese N, Gött R, Kern J, Lablans M et al. (2023). Understanding the Nature of Metadata: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 24(1): e25440. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8790684/.

- Hollman S, Frohme M, Endrullat C, Kremer A, D’Elia D, Regierer B et al. Ten simple rules on how to write a standard operating procedure. Plos Computational Biology. 2022, 16, e1008095. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7470745/.

- HitchhikersAI [Internet] [cited 2024 September]. Available online: https://www.hitchhikersai.org/.

- Pistoia Alliance [Internet] [cited 2024 September]. Available online: https://www.pistoiaalliance.org/.

- Washington N, Lewis S (2008). Ontologies: Scientific Data Sharing Made Easy. Nature Education. 1(3):5. Available online: https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/ontologies-scientific-data-sharing-made-easy-77972/.

| Guideline | Implementation example 1 | Implementation example 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Collection and Entry | Standardisation: Implement standardised operating procedures (SOPs) for data collection and entry, including consistent use of units, naming conventions, and data formats. | Training: Train the team involved in data collection on the importance of data quality and the specific protocols to follow to minimise errors. |

| 2. Data Validation | Automated Checks: Use automated validation scripts to check for common issues such as missing values, duplicates, outliers, and inconsistencies in units or formats. | Manual Review: Periodically perform manual reviews of a subset of the data to identify any issues that automated checks might miss. |

| 3. Data Cleaning | Missing Data Handling: Develop a strategy for handling missing data, such as deciding when to use imputation, exclude data points, or flag datasets for further investigation. | Outlier Detection: Implement methods to identify and investigate outliers, determining whether they represent true variability or errors. |

| 4. Data Integration | Harmonisation: Ensure that data from different sources or experiments are harmonised before integration. This includes reconciling different naming conventions, units, and formats. | Cross-Validation: Use cross-referencing methods to validate integrated datasets, checking for consistency and correctness. |

| 5. Data Documentation | Metadata: Maintain detailed metadata for each dataset, including information about the origin, collection method, and any preprocessing steps. This helps in tracking data provenance and understanding the context. | Version Control: Use version control systems for datasets to track changes and ensure that any modifications are well-documented and reversible. |

| 6. Data Monitoring | Continuous Monitoring: Implement ongoing monitoring of data quality metrics, such as completeness, accuracy, and consistency, throughout the data lifecycle. | Alerts: Set up automated alerts to notify relevant personnel if data quality metrics fall below predefined thresholds. |

| 7. Data Auditing | Regular Audits: Conduct regular data audits to assess the overall quality of your datasets. This involves checking for adherence to data quality standards and identifying any systemic issues. | Audit Trails: Maintain audit trails that log all data processing steps, transformations, and any changes made to the data. This ensures traceability and accountability. |

| 8. Bias and Variability Checks | Bias Analysis: Regularly assess your datasets for potential biases, such as over-representation of certain chemical scaffolds or biological targets. Use statistical techniques to quantify bias and take corrective actions. This involves a change in mindset in particular, from project-based data generation, to process-based data generation (where said process involves the use of AI models by default) | Variance Analysis: Analyse the variability in your data, especially in biological assays, to understand the level of noise and its impact on model performance. |

| 9. Data Redundancy and Duplication Checks | Duplicate Detection: Implement robust mechanisms to detect and remove duplicate records to prevent skewing of the data. | Feature Redundancy Check: Use techniques like correlation analysis to identify and eliminate redundant features that do not contribute new information. |

| 10. Data Imbalance Handling | Balance Check: Continuously monitor the balance of different classes in your data (e.g., active vs. inactive compounds). Address imbalances through methods like oversampling, undersampling, or synthetic data generation.#break# | Model Adaptation: If data imbalance is unavoidable, consider using model algorithms that are better suited to handle imbalanced data. |

| 11. Data Security and Access Control | Access Control: Restrict access to data based on roles and responsibilities to prevent unauthorised modifications or data entry errors. | Data Security: Implement security measures to protect data from corruption, loss, or unauthorised access, ensuring that data integrity is maintained. |

| 12. Communication and Collaboration | Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Foster collaboration between data scientists, domain experts, and IT professionals to ensure that data quality requirements are clearly understood and addressed. | Feedback Loop: Establish a feedback loop where issues identified by data scientists or model results are communicated back to the experimental team to refine data collection processes. |

| 13. Use of Quality Control Samples | Control Samples: Include quality control samples (e.g., known standards or replicates) in experimental runs to monitor and ensure consistency in assay performance. | QC Analysis: Regularly analyse the results of quality control samples to identify any drifts or deviations in experimental conditions that could impact data quality. |

| 14. Data Quality Metrics and Reporting | Define Metrics: Define specific data quality metrics such as predictivity for a downstream endpoint, accuracy, completeness, consistency, timeliness, and uniqueness. Use these metrics to evaluate and report on the quality of your data regularly. | Reporting: Regularly report on data quality metrics to stakeholders, ensuring transparency and facilitating continuous improvement. |

| 15. Continuous Improvement | Root Cause Analysis: When data quality issues are identified, perform root cause analysis to understand the underlying reasons and implement corrective actions. | Iterative Process: Treat data quality improvement as an iterative process, continuously refining and enhancing your strategies as new challenges and technologies emerge. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).