Introduction

Regular physical activity (PA) is critical to a healthy lifestyle. Scientific studies have repeatedly demonstrated its positive impact on quality of life, health, and well-being. Numerous scientific studies indicate that physical exercise induces beneficial neuropathic changes in the brain of people suffering from neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson's disease (PD) [1-2].

It has been proven that PA is a recommended intervention for older adults, as it affects cognitive functions, the number of falls, mobility, and mood, among other factors (2). In the realm of physical activity (PA) research, there exists a fundamental need for consistent guidelines that measure specific aspects of PA in older individuals. At present, there is a significant degree of heterogeneity in the selection of outcomes, which can lead to biases and hinder the ability to compare and combine results across studies. As a consequence, this presents challenges in identifying effective, ineffective, and untested PA interventions, thereby making it difficult to make informed decisions relating to healthcare programming and promoting PA for public health initiatives aimed at supporting the aging population [

3].

In this context, measuring PA in older individuals is crucial for understanding PA's impact on health and quality of life, identifying the best forms of activity for this age group, maintaining independence, and monitoring the effectiveness of intervention programs [

4].

There are limitations to the PA measurement tools available as physical fitness levels vary significantly. While some tools work well for assessing PA in active individuals, they may not be effective in differentiating PA in those with physical limitations or who lead sedentary lifestyles. Furthermore, advanced age is often associated with chronic conditions and diseases that can impact physical exertion. Recommendations for PA within specific disease entities may not provide an accurate view. Conditions that limit maximal or submaximal intensity efforts require engaging in lower intensity efforts, which complicates proper measurement and interpretation [5-6].

Studies have demonstrated that the rapid advancement of technology and measuring devices can lead to challenges when attempting to operate them. For instance, specific measuring techniques, like activity monitors worn on the wrist, may not be practical or comfortable for older people, which can lead to inaccurate readings. Psychological aspects are also an additional consideration. Measuring PA requires a certain level of self-awareness and motivation. Older individuals might struggle with self-esteem and may also have concerns that measuring PA could lead to a loss of privacy or be perceived as an intrusion into their daily lives [

4].

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder. The primary risk factor is the brain's aging, which occurs due to metabolism and neuronal homeostasis disturbances. PD can result from the interaction of genetic and environmental factors [7-9]. It is estimated that 7 - 10 million people worldwide suffer from PD. The average age of onset is 60 years, and along with it, the incidence increases. However, in about 5 - 10% of the population, the disease begins before age 50 [10-11]. Clinicians identify four main motor symptoms of PD: tremor, muscle rigidity, bradykinesia, and impaired postural reflexes [

12]. Due to the complex mechanism underlying motor impairments, which can lead to progressive loss of independence and, ultimately, disability despite optimal medical or surgical treatment, physical rehabilitation is an essential complement to pharmacological therapy [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Rehabilitation is primarily focused on improving specific aspects of mobility (stretching-strengthening exercises, balance exercises, posture, and occupational therapy) [

17]. Resistance exercises are also used, among others, to enhance specific gait parameters. The effectiveness of externally generated control signals facilitating the initiation and maintenance of motor activities has been demonstrated [

18,

19]. Researchers often focused on selected aspects of physical fitness, proposing a traditional approach based on motor symptoms or a conditioning (aerobic) exercise-oriented approach [

20].

A thorough analysis of studies in the literature has shown that physical rehabilitation yields clinically significant benefits, yet the interventions presented are largely heterogeneous [

17,

21]. Therefore, in this work, a functional physical rehabilitation (FPR) was implemented, combining a traditional approach with a modern perspective, and symptom-based therapy is directly linked to task-oriented training [

22].

According to the literature, multiple studies suggest that physical rehabilitation and physical activity are closely connected [

23,

24]. Engaging in physical activity during middle age can lower the risk of Parkinson's disease and potentially influence its progression. Many exercise programs are effective in slowing down the progression of the disease and reducing the severity of motor symptoms. Recommendations regarding physical activity should be a significant component of the rehabilitation process for individuals with PD. Emphasizing the regularity of exercises to achieve and maintain good physical condition, the selection of practices should not only be tailored to patients' capabilities but also consider their interests to motivate them for regular physical exercise [

25,

26].

Accurate measurement of PA is therefore critical for understanding the effects of the disease and developing effective treatment strategies. Measure the PA in people with PD to track the progression of the disease and its effects on motor function. Regular measurement of PA allows us to monitor changes in motor function over time and identify potential improvements or declines. This information is essential for developing effective treatment plans and making adjustments as needed to ensure optimal management of PD symptoms [

14,

27,

28]. Moreover measuring PA is to evaluate the effectiveness of different treatment options. PA is often prescribed as part of a comprehensive treatment plan for people with PD. Regular measurement allows us to assess the impact of PA on motor function and quality of life, and to identify areas for improvement. This information is valuable for developing targeted interventions that are most effective for individual patients [

29]. Measuring PA also provides a valuable tool for tracking the impact of lifestyle factors. People with PD may engage in PA for a variety of reasons, including for exercise, leisure, or work-related activities. Regular measurement allows healthcare providers to understand the impact of these activities on motor function and quality of life and to identify strategies for optimizing PA in people with PD [

29,

30,

31].

Research has indicated that individuals with Parkinson's Disease (PD) often report higher levels of physical activity (PA) than they perform. This discrepancy may arise from a divergence between their perception of PA and the actual definitions of the term, leading to an overestimation of engagement in such activities. The subjective nature of self-reported PA plays a significant role in this phenomenon. Individuals with PD may need to fully recognize or comprehend the various activities that qualify as PA, such as household chores or walking, which may result in a lower reported activity level. Furthermore, challenges associated with the motor symptoms of PD, including tremors, stiffness, and difficulties with balance and coordination, can hinder participation in physical activities. This can lead to a reduced perception of engagement even when actual activity levels may be relatively substantial. Additionally, individuals with PD may tend to avoid certain types of physical activity or may require assistance with specific tasks, further diminishing their perceived involvement in PA [

32,

33].

How the PA is measured can also contribute to the discrepancy between perception and reality. Self-reported is typically measured using self-reported questionnaires or diaries, subject to the abovementioned biases and inaccuracies. Objective PA tracking devices, such as wearable devices or accelerometers, can provide a more accurate measurement.

The discrepancy between the perception and reality of PA in people with PD is a complex issue with multiple factors contributing to the problem, therefore the aim of the study was to compare the level of self-reported and objective PA of people with PD in the context of participation in FPR.

Material and methods.

The study included 47 patients with idiopathic PD, according to criteria set by the United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank, aged 64.37±7.12 yrs., disease duration 6.29 ± 4.02 yrs., in II and III stages of the disease according to the Hoehn and Yahr scale [

34]. To determine the clinical status of patients, the Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) was applied [

35].

The patients volunteered to participate in the study. A Committee for Bioethics of the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice gave consent for carrying out the examinations (30/2017). All examined patients were informed about the purpose and the course of examinations and provided expressed written consent for their participation in them. The patients did not have other coexisting neurodegenerative diseases.

The subjects were randomly assigned to two groups: participating (group A) and not participating in the FPR program (group B). The characteristics of the subjects divided into groups are presented in tab.1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects.

| Characterisctic |

Group A

(n=25) |

Group B

(n=22) |

t-student test |

|

| X± SD |

X± SD |

T |

p |

|

|

| Age (years) |

63,27±5,86 |

64,42±6,45 |

2,31 |

0,21 |

|

|

| Disease duration (years) |

5,93±1,34 |

6,73±1,97 |

3,72 |

0,49 |

|

|

MDS -UPDRS

[pts] |

ME-DL |

7,89±0,81 |

8,27±0,72 |

1,63 |

0,12 |

|

| ME |

25,67±2,08 |

28,97±3,23 |

2,52 |

0,02* |

|

| MC |

2,89±0,84 |

3,12±0,79 |

2,74 |

0,06 |

|

| Total |

36,45±4,89 |

40,36±4,72 |

2,32 |

0,03* |

|

Subjects from group A participated in 60 minutes of FPR in the gym twice a week, for 9 months, before the study commenced. The researchers conducted a program that aimed to improve the functional independence and quality of life of individuals with PD. The program focused on addressing motor symptoms and concurrent task-oriented training. The main principles of the program were based on combining therapy that targets motor symptoms with task-oriented therapy. Each exercise was functionally justified and designed to help patients cope with daily activities.

Rehabilitation in this form allows for the prevention and correction of secondary changes leading to functional impairment and effective modification of the complexity of exercises at each stage of cooperation based on the patient's functional priorities. In each functional exercise, the following were used: strategies targeted at motor problems resulting from symptoms and particularly recommended and useful in a specific functional motor task. The rehabilitation process was adapted to the needs and capabilities of the patient and focused on the most important problem related to movement (muscle stiffness, slowness of movement, postural reflex disorders, tremors). Rehabilitation sessions consisted of performing simple and complex movement patterns to increase the fluidity of motor skills. These patterns were based on movement templates, were functionally justified, and aimed at developing the ability to manage everyday activities (independent turning and getting out of bed, dressing, putting on and lacing shoes, going up and down stairs and crossing thresholds, moving around in the field) [

31,

36].

Additionally, exercises targeting reduced muscle tension and strategies for coping with tremors were implemented. The essence of the condition was taken into account, where motor programs are preserved, automatic movements fade or become voluntary-dependent, and voluntary activities emerge with delay, slowness, and incompleteness. In each functional exercise, targeted strategies were employed to address motor issues arising from symptoms, specifically recommended and valuable for the defined functional movement task [

31,

36].

Used sets of exercises were worked out by authors of the research work based on literature.

The patients from group B did not participate in the rehabilitation sessions.

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)[

37,

38] and triaxial accelerometer, Actigraph GT3X+, were used to measure the weekly physical activity (AC)[

4,

29].

The assessment of PA was conducted using a weekly physical activity, which recorded accelerations in the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes. The device was worn by the participants for seven consecutive days at hip level and removed only during sleep and water-related activities. According to the PA assessment guidelines, measurements were conducted in October and March [

4].

The accelerometer-recorded data were subjected to statistical analysis using ActiLife 5.10.0 software, which allowed for obtaining physical activity parameters such as the duration of physical efforts of low, moderate, and high intensity. The following thresholds of recorded accelerations (signals) per minute (counts per minute - cpm) were adopted for this purpose:

200-2689 cpm for low-intensity physical activity,

2690-6166 cpm for moderate-intensity physical activity,

6167 cpm and above for high-intensity physical activity [

39].

The respondents filled out an IPAQ questionnaire during the time reading data from the accelerometer in order to determine the level of self-reported PA. They were supposed to assess their PA of the previous week, in which they wore the accelerometer. A short version of the IPAQ questionnaire was used and contained questions about the number of days of the week when they made efforts in the respective zones of intensity. Based on the responses of the surveyed people, the volume of PA was evaluated in the intensity zones as follows: low (walking), moderate, high (vigorous).

Based on the collected data, frequency of PA, intensity, and duration during the day, the weekly volume of PA was determined for three intensity zones. The intensity of the activity was determined using the metabolic equivalent of task (MET), 8.0 MET for activity with vigorous intensity (PA1), 4.0 MET for moderate intensity (PA2) and 3.3 MET for low (walking) intensity (PA3). The calculation procedure involved multiplying the number of days, duration, and the MET values for each intensity zone separately. The total weekly physical activity (WPA) was determined by summing up its level in the three intensity zones (MET-min/week) [

40]. The calculations were made separately for the data obtained from the questionnaire and from the Actigraph.

The obtained results were compiled and prepared in accordance with statistics rules. Basic descriptive statistics were calculated and the normal distribution was examined by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In order to evaluate the significance of differences, the Student’s t-distribution test was applied for independent samples.

Results

Comparing self-reported weekly physical activity with the objective showed statistically significant differences in both groups (

Table 2). In relative values, the self-reported physical activity level was 8.61% higher in group A, while in group B it was higher by 56.70%.

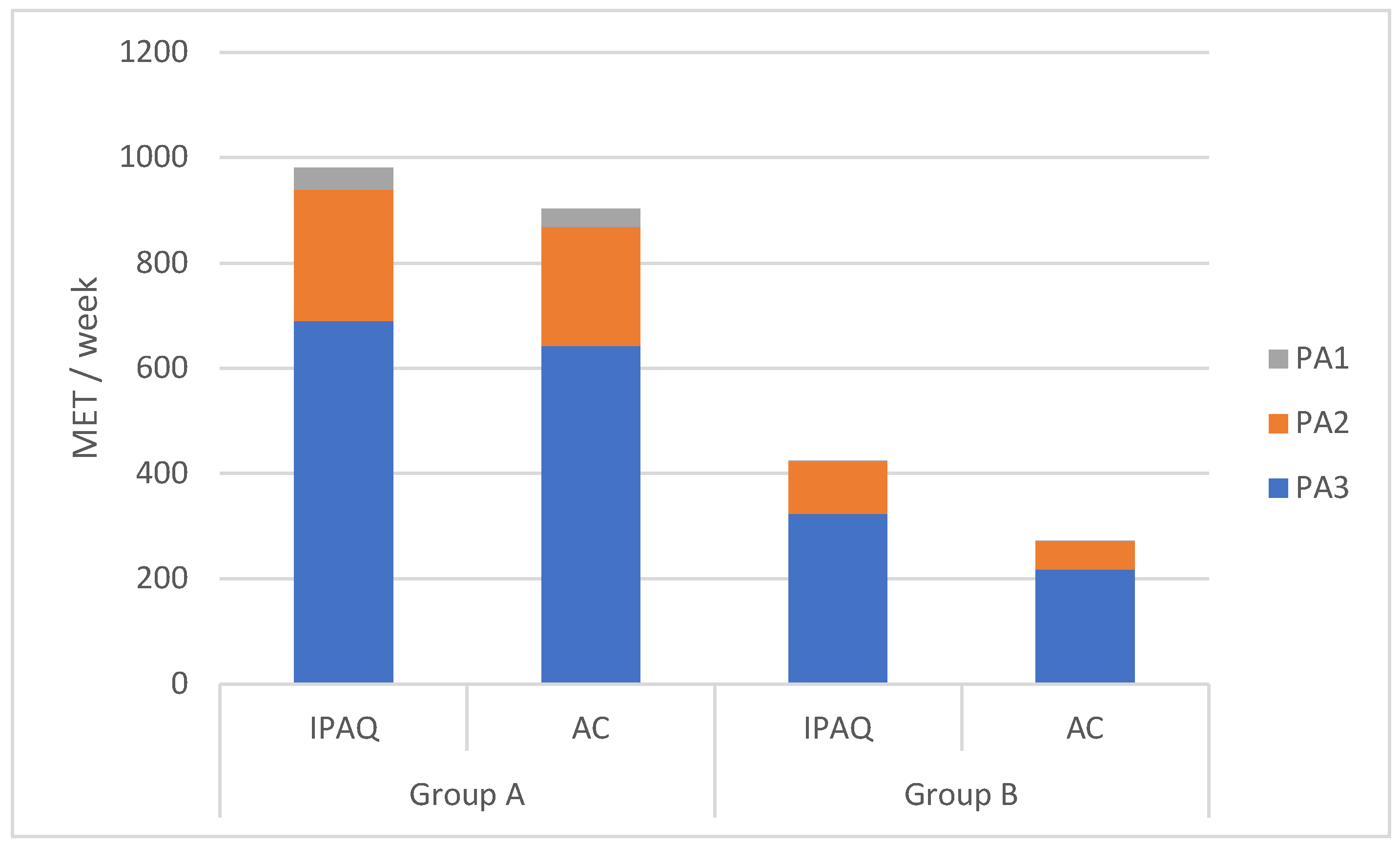

According to the methodology adopted in this study, the size of WPA is the sum of PA in each intensity zone; therefore, further analysis was conducted on the level of weekly PA divided into intensity zones (Fig.1). In both studied groups, efforts in the low-intensity zone dominated. In group A, the declared level of PA was higher than the objective in all intensity zones. Specifically, the reported level was 19.50% higher in the high-intensity zone, 10.52% higher in the moderate-intensity zone, and 7.35% higher in the low-intensity zone. However, only the differences in the moderate-intensity zone (p<0.01) and high-intensity zone (p<0.02) were statistically significant.

In group B, similar to group A, self-reported PA was higher than objectively measured PA. The highest relative difference was observed in the high-intensity zone (250%), followed by the moderate-intensity zone (90.66%) and the low-intensity zone (48.32%). These differences were statistically significant (PA1- p<0.001, PA2- p<0.01, PA3-p<0.002).

Figure 1.

Weekly PA in MET MET – Metabolic equivalent of task, IPAQ – Weekly PA measure by International Physical Activity Questionnaire, AC – Weekly PA measure by accelerometer, PA 1 – Physical activity of high intensity, PA 2 – Physical activity of moderate intensity, PA 3 – Physical activity of low intensity.

Figure 1.

Weekly PA in MET MET – Metabolic equivalent of task, IPAQ – Weekly PA measure by International Physical Activity Questionnaire, AC – Weekly PA measure by accelerometer, PA 1 – Physical activity of high intensity, PA 2 – Physical activity of moderate intensity, PA 3 – Physical activity of low intensity.

As the PA level in individual zones is a product of the number of days at a given intensity and the duration of effort, these parameters were analyzed (

Table 3).

Analyzing the data of frequency and volume of daily PA in three intensity zones within the group, it was found that statistically significant differences occurred in both examined parameters in the high-intensity zone. However, in the moderate and low-intensity zones, statistically significant differences were found in the duration of efforts. Statistically insignificant differences in the frequency of undertaking efforts were observed in these zones.

In group B, statistically significant differences were found in the duration of efforts in all zones and in the frequency of undertaking efforts in the moderate and low-intensity zones. Statistically insignificant differences occurred in the frequency of undertaking efforts in the high-intensity zone.

Discusion

Identifying the main factor responsible for discrepancies between reported and actual PA levels is complex [

41]. Studies have shown that there are significant differences between subjectively reported and objectively monitored, especially in people with PD. Accurate measurement, especially in older people and those with PD, is difficult due to both movement and non-movement disorders.

Objective measurement, e.g., using accelerometers, allows for precise determination of activity level and exercise intensity, but self-report methods, although practical and widely used, are prone to overestimation or underestimation due to difficulties in planning and executing tasks, focusing attention on PA, the influence of social expectations, and misinterpretation of data [42-43].

Although questionnaires such as the IPAQ, often used in clinical and population studies, provide useful information on weekly PA, they have limitations [

38,

44,

45]. Studies by Kang [

46] and Kelly [

47] indicate that in many social groups, there is a tendency to over report, which may result from the desire to improve one’s self-image, feel better, or meet expectations related to a healthy lifestyle.

Another important factor that may influence the differences between reported and actual PA is the physical limitations associated with PD. For example, studies by Clina et al. [

48] have shown that people with disabilities, compared to healthy people, tend to have a higher subjective assessment of activity related to performing household chores. This may be due to the incredible difficulty these people experience when performing daily activities, affecting their perception of effort. Musculoskeletal problems like pain and fatigue may complicate precise task performance, affecting their PA self-assessment [

48].

Cognitive impairment, which often accompanies PD, further complicates the accurate assessment of activity levels. Reduced ability to assess physical effort and problems with planning and organizing activities may lead to incorrect retrospective assessments of the intensity and duration of activity. As a result, subjective assessments of activity in older populations should be treated with caution because cognitive dysfunctions may partially explain the differences between objective and subjective measures of PA [

49,

50].

Our results indicate that people with PD who participated in FPT had a lower tendency to overestimate their level of effort and a higher level of PA compared to those who did not participate in the rehabilitation program. These results suggest that FPT may be an effective intervention to improve both the level of activity and the accuracy of its assessment.

Studies presented in the literature suggest that physical rehabilitation improves brain plasticity, essential for improving motor and cognitive functions [

51]. Regular exercise can support brain function by inhibiting inflammation, reducing oxidative stress, and stimulating synaptogenesis and angiogenesis, which affects more accurate self-assessment of physical effort [

52]. Therefore, exercise therapy is a valuable tool in managing non-motor symptoms of PD and can support pharmacological treatment [

51].

Accurate determination of the actual level of PA in the context of PD is crucial, as PA is a potentially modifiable risk factor for disease progression. Further research is needed to identify the main factor responsible for the discrepancies between subjective and objective measures of PA. Therefore, studies that consider physical fitness level and disease severity may contribute to a better understanding of the interaction between reported and actual activity and its impact on motor and non-motor symptoms.

Conclusions

A reliable assessment of PA levels is an important tool for evaluating disease progression, monitoring treatment effectiveness, and assessing the efficiency of rehabilitation programs. The conducted research revealed significant discrepancies between self-reported and objectively measured PA levels in individuals with PD, depending on their participation in FPT. Based on the study results, it was concluded that participation in functional physical rehabilitation improves the accuracy of self-assessment of physical activity levels.

References

- Chang M, Geirsdottir O, Thorsdottir I, Jonsson P, Ramel A, Gudjonsson MC. Relationship Between Physical Activity and Function With Quality of Life in Community-Living Older Adults. Innov Aging. 2020;4(Suppl 1):189. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.E.; Li, Q.; Nacca, A.; Salem, G.J.; Song, J.; Yip, J.; Hui, J.S.; Jakowec, M.W.; Petzinger, G.M. Treadmill exercise elevates striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in patients with early Parkinson's disease. NeuroReport 2013, 24(10), 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, D.C; Ekegren, C.L.; Baldwin, C.; Young, P.J.; Gray, S.M.; Ciok, A.; Wong, A. Outcome domains measured in randomized controlled trials of physical activity for older adults: a rapid review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 24;20(1), 34. [CrossRef]

- Ito H, Yokoi D, Kobayashi R, Okada H, Kajita Y, Okuda S. The relationships between three-axis accelerometer measures of physical activity and motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease: a single-center pilot study. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):340. [CrossRef]

- Helmerhorst, H.J.; Brage, S.; Warren, J.; Besson, H.; Ekelund, U. A systematic review of reliability and objective criterion-related validity of physical activity questionnaires. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doma, K.; Speyer, R.; Parsons, L.A.; Cordier, R. Comparison of psychometric properties between recall methods of interview-based physical activity questionnaires: a systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blauwendraat, C.; Nalls, M.A.; Singleton, A.B. The genetic architecture of Parkinson's disease. The Lancet Neurology 2020, 19(2), 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, S.; Zhang, L.; Mollenhauer, B.; Jacob, J.; Longerich, S.; et al. A proteogenomic view of Parkinson's disease causality and heterogeneity. NPJ Parkinson's disease 2023, 9(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.; Chiu, R.; Lee, J. Parkinson disease primer, part 1: diagnosis. Can. Fam. Physician. 2023, 69(1), 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.S.; Bloem, B.R. The emerging evidence of the Parkinson pandemic. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2018, 8(s1), S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysnes, O.B.; Storstein, A. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. J. Neural Trans. (Vienna), 2017, 124(8), 901–905. [CrossRef]

- Váradi C. Clinical Features of Parkinson's Disease: The Evolution of Critical Symptoms. Biology (Basel). 2020;9(5):103. [CrossRef]

- Cholewa, J.; Gorzkowska, A.; Nawrocka, A.; Cholewa, J. Quality of life of people with Parkinson's disease in the context of professional work and physiotherapy. Med. Pr. 2017, 68(6), 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.; Folkerts, A.K.; Gollan, R.; Lieker, E.; Caro-Valenzuela, J.; et al. Physical exercise for people with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 1(1), CD013856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lena, F.; Modugno, N.; Greco, G.; Torre, M.; Cesarano, S.; et al. Rehabilitation interventions for improving balance in Parkinson's disease: A Narrative Review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 102(3), 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, S.; Teixeira, D.; Monteiro, D.; Imperatori, C.; Murillo-Rodriguez, E.; et al. Clinical applications of exercise in Parkinson's disease: what we need to know? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2022, 22(9), 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C.L.; Herd, C.P.; Clarke, C.E.; Meek, C.; Patel, S.; et al. Physiotherapy for Parkinson's disease: a comparison of techniques. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, (6), CD002815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, R.; Diverio, M.; Zucchi, F.; Lentino, C.; Abbruzzese, G. The role of sensory cues in the rehabilitation of parkinsonian patients: a comparison of two physical therapy protocols. Mov. Disord. 2020, 15(5), 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwboer, A.; Kwakkel, G.; Rochester, L.; Jones, D.; van Wegen, E.; et al. Cueing training in the home improves gait-related mobility in Parkinson's disease: the RESCUE trial. J. Neurol. Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010, 81(1), 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, M., Folkerts, A. K., Gollan, R., Lieker, E., Caro-Valenzuela, J., Adams, A., Cryns, N., Monsef, I., Dresen, A., Roheger, M., Eggers, C., Skoetz, N., & Kalbe, E. (2023). Physical exercise for people with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 1(1), CD013856. [CrossRef]

- Lauzé, M.; Daneault, J.F.; Duval, C. The effects of physical activity in Parkinson's disease: A Review. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2016, 6(4), 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cholewa, J.; Gorzkowska, A.; Szepelawy, M.; Nawrocka, A.; Cholewa, J. Influence of functional movement rehabilitation on quality of life in people with Parkinson's disease. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2014, 26(9), 1329–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordani C, Mosconi B. What type of physical exercise works best to improve movement and quality of life for people with Parkinson's disease? - A Cochrane Review summary with commentary. NeuroRehabilitation. 2024;54(4):699-702. [CrossRef]

- van der Marck MA, Kalf JG, Sturkenboom IH, Nijkrake MJ, Munneke M, Bloem BR. Multidisciplinary care for patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15 Suppl 3:S219-S223. [CrossRef]

- Emig, M.; George, T.; Zhang, J.K.; Soudagar-Turkey, M. The role of exercise in Parkinson's disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2021, 34(4), 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.C.; Su, C.H. Evidence supports PA prescription for Parkinson's disease: Motor symptoms and non-motor features: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17(8), 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, A.W.; Chahine, L.; Seedorff, N.; Caspell-Garcia, C. J.; Coffey, C.; Simuni, T. Parkinson's progression markers initiative. Self-reported physical activity levels and clinical progression in early Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relad. Disord. 2019, 61, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, M.; Hvid L., G.; Dalgas, U.; Langeskov-Christensen, M. Parkinson's disease and intensive exercise therapy - an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2022, 145(5), 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correno, M.B.; Hansen, C.; Carlin, T.; Vuillerme, N. Objective measurement of walking activity using wearable technologies in people with Parkinson disease: A systematic review. Sens. 2022, 22, 4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Núñez, J.; Calvache-Mateo, A.; López-López L.; Heredia-Ciuró, A.; Cabrera-Martos, I.; Rodríguez-Torres, J.; Valenza, M.C. Effects of exercise-based interventions on physical activity levels in with Parkinson's disease persons: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Cholewa, J.; Gorzkowska, A.; Kunicki, M.; Stanula, A.; Cholewa, J. Continuation of full time employment as an inhibiting factor in Parkinson's disease symptoms. Work 2016, 54(3), 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantri, S.; Wood, S.; Duda, J. E.; Morley, J. F. Comparing self-reported and objective monitoring of physical activity in Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relad. Dis., 2019, 67, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzkowska, A.; Cholewa, J.; Malecki, A.; Klimkowicz-Mrowiec, A.; Cholewa, J. What determines spontaneous physical activity in patients with Parkinson's disease? J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9(5), 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, M. M.; Yahr, M. D. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967, 17(5), 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23(15), 2129–2170. [CrossRef]

- Cholewa J, Cholewa J, Nawrocka A, Gorzkowska A. Senior Fitness Test in the assessment of the physical fitness of people with Parkinson's disease. Exp Gerontol. 2021;151:111421. [CrossRef]

- International Physical Activity Questionnaire. http://www.ipaq.ki.se/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022.

- Sember, V.; Meh, K.; Sorić, M.; Starc, G.; Rocha, P.; Jurak, G. Validity and reliability of International Physical Activity Questionnaires for adults across EU countries: systematic review and meta analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17(19), 7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nero, H.; Benka Wallén, M.; Franzén, E.; Ståhle, A.; Hagströmer, M. Accelerometer cut points for physical activity assessment of older adults with Parkinson's disease. PloS one 2015, 10(9), e0135899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B. E.; Haskell, W. L.; Herrmann, S. D.; Meckes, N.; Bassett, D. R.; Jr, Tudor-Locke, C.; Greer, J. L.; Vezina, J.; Whitt-Glover, M. C.; Leon, A. S. Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43(8), 1575–1581. [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, K.; Rhodes, R.; Naylor, P. J.; Tuokko, H.; MacDonald, S. Direct and indirect measurement of physical activity in older adults: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, M.C.; Jaunig, J.; Tösch, C.; Watson, E.D.; Mokkink, L.B.; Dietz, P.; van Poppel, M.N.M. Current evidence of measurement properties of physical activity questionnaires for older adults: an updated systematic review. Sports Med. 2020, 50(7), 1271–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malec, J.F.; Testa, J.A.; Rush, B.K.; Brown, A.W.; Moessner, A.M. Self-assessment of impairment, impaired self-awareness, and depression after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007, 22(3), 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhlin, J.; Toots, A.; Dahlin Almevall, A.; Littbrand, H.; Conradsson, M.; Hörnsten, C.; Werneke, U.; Niklasson, J.; Olofsson, B.; Gustafson, Y.; et al. Concurrent validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire adapted for adults aged ≥ 80 years (IPAQ-E 80 +) - tested with accelerometer data from the SilverMONICA study. Gait Posture, 2022, 92, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ånfors, S.; Kammerlind, A.S.; Nilsson, M.H. Test-retest reliability of physical activity questionnaires in Parkinson's disease. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21(1), 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.G.; Charnigo, R.J. Self-reported vs. objectively measured physical activity: effects on subjective measures of mood and quality of life in college-aged women. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19(5), 659-669.

- Kelly, P.; Fitzsimons, C.; Baker, G.; Mutrie, N. The problem with using one question to assess physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. Age Ageing, 2014, 43(2), 209-214.

- Clina, J.G.; Herman, C.; Ferguson, C.C.; Rimmer, J.H. Adapting an evidence-based physical activity questionnaire for people with physical disabilities: A methodological process. Disabil. Health J. 2023, 16(3), 101447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amboni, M.; Barone, P.; Hausdorff, J. M. Cognitive contributions to gait and falls: evidence and implications. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28(11), 1520–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbolsheimer, F.; Riepe, M.W.; Peter, R. Cognitive function and the agreement between self-reported and accelerometer-accessed physical activity. BMC Geriatrics, 2018, 18(1), 56. [CrossRef]

- Palasz, E.; Bak, A.; Niewiadomska, G. Increased physical training as supportive therapy in Parkinson’s disease – research in humans and animalse. KOSMOS, 2016, 65(3), 351–360. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M.A.; Farley, B.G. Exercise and neuroplasticity in persons living with Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Physic. Rehabilit. Med. 2009, 35, 215–229. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).