Submitted:

05 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Part

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Measurements

2.3 Synthesis of the Copolymers

2.4. Esterification Reaction

2.5. Study of Heterogeneous Hydrolysis of Poly(HEMA-co-IA)-Herbicide

3. Results and Discusion

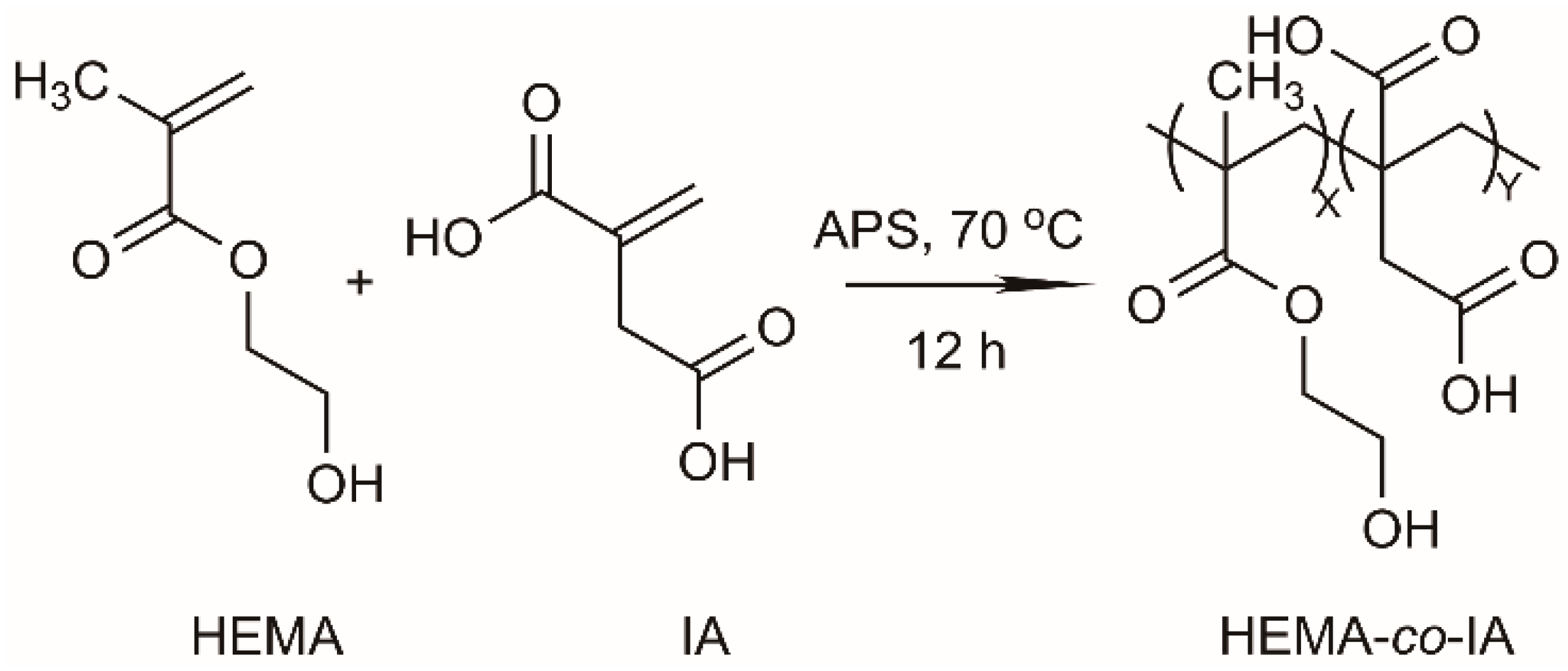

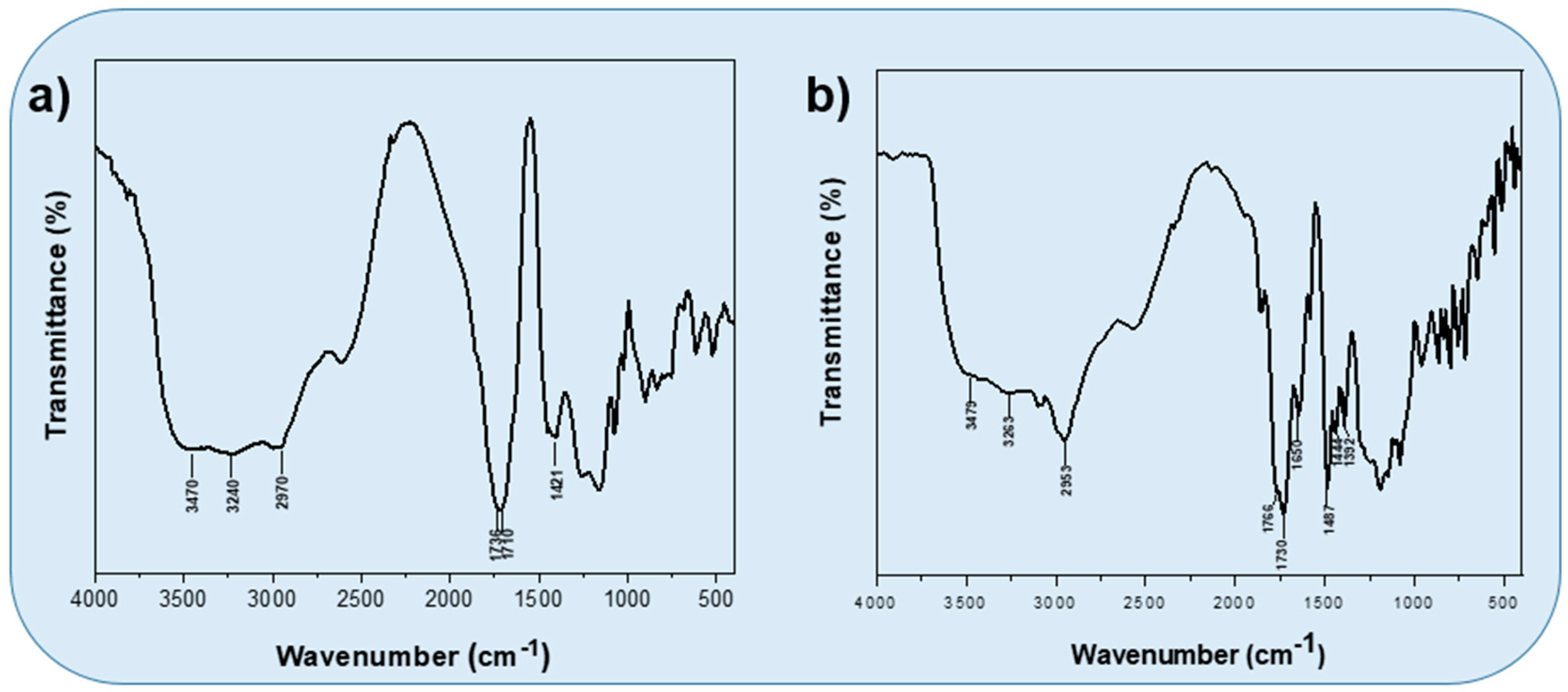

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(HEMA-co-IA)

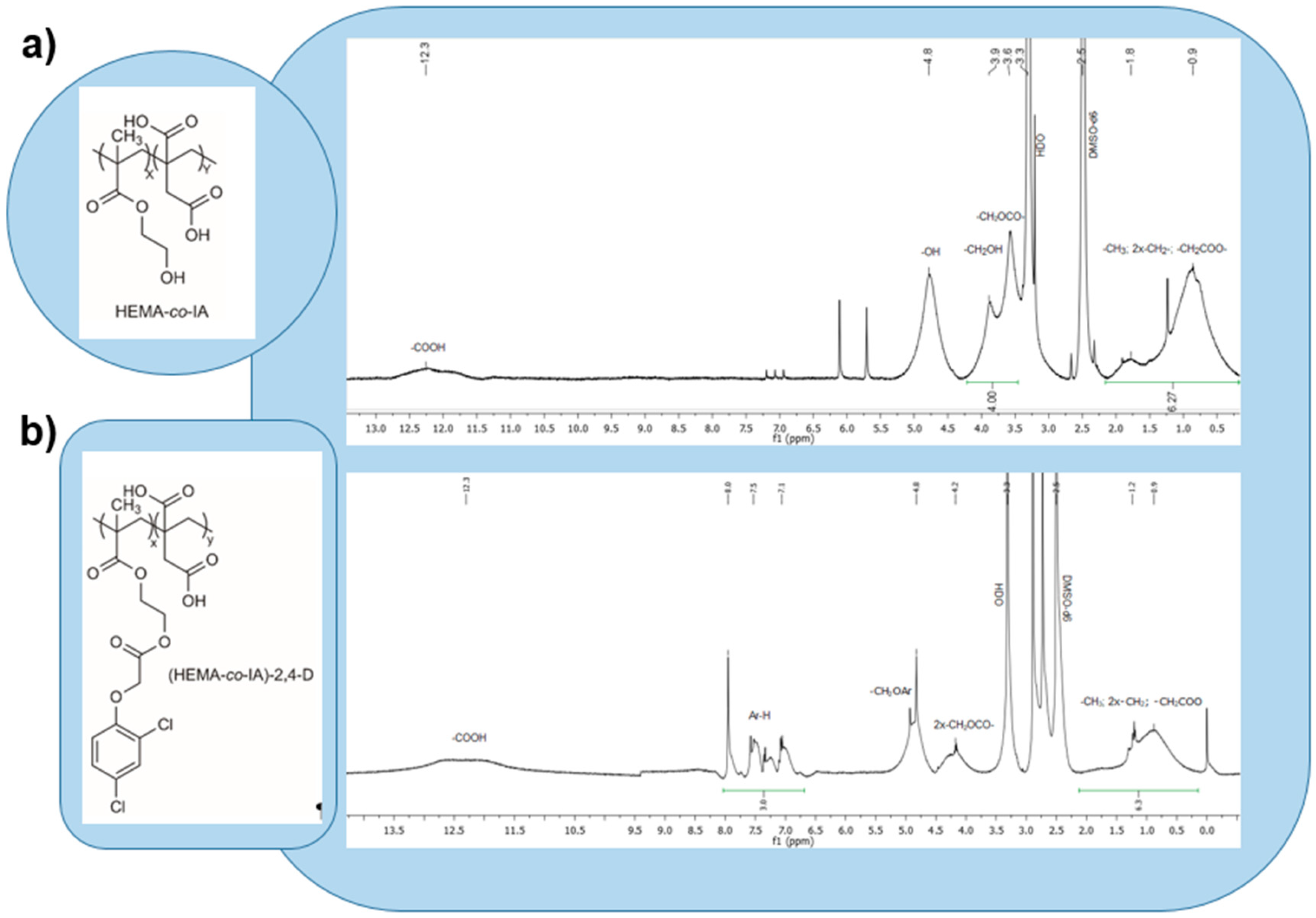

3.2. Copolymer Composition by 1H-NMR

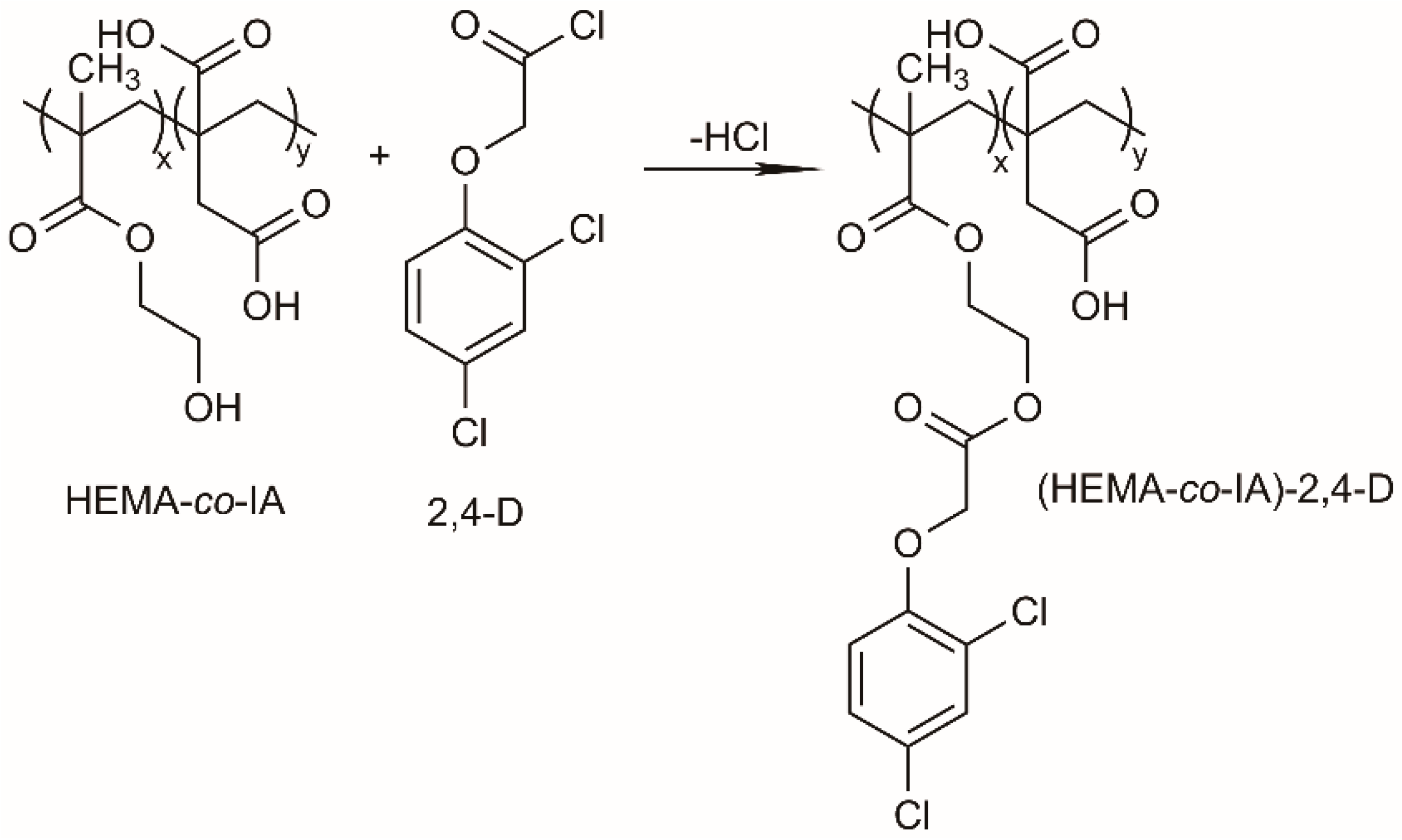

3.3. Poly(HEMA-co-IA) Matrix Grafted with 2,4 D-Chloride

3.4. Degree of Functionalization of Poly(HEMA-co-IA)-2,4-D.

3.5. Determination of Monomer Reactivity Ratios

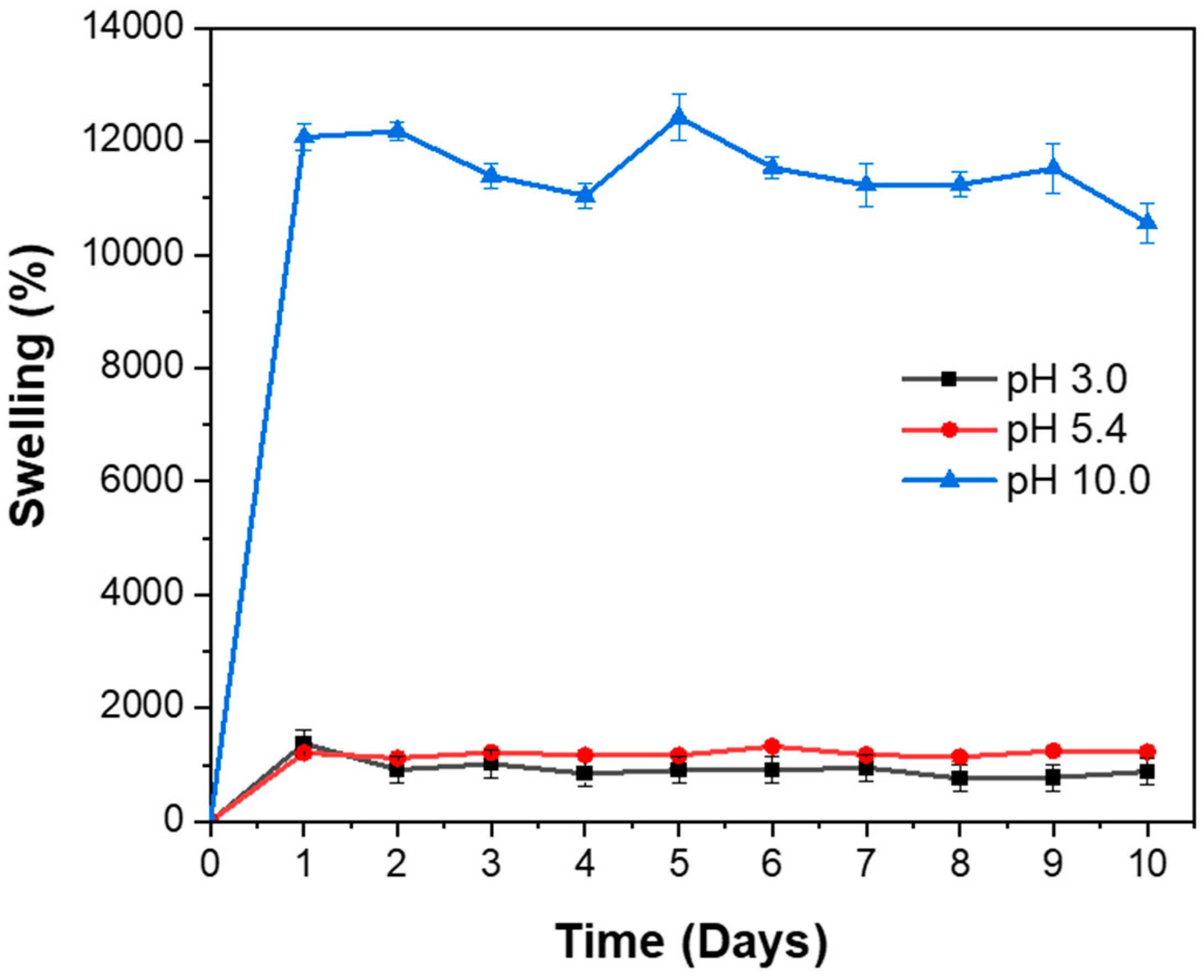

3.6. Swelling Behavior of Hydrogel: Influence of pH

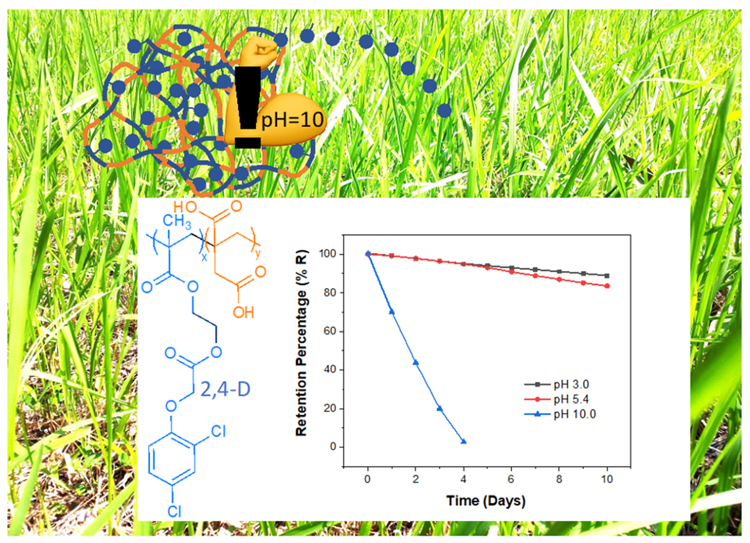

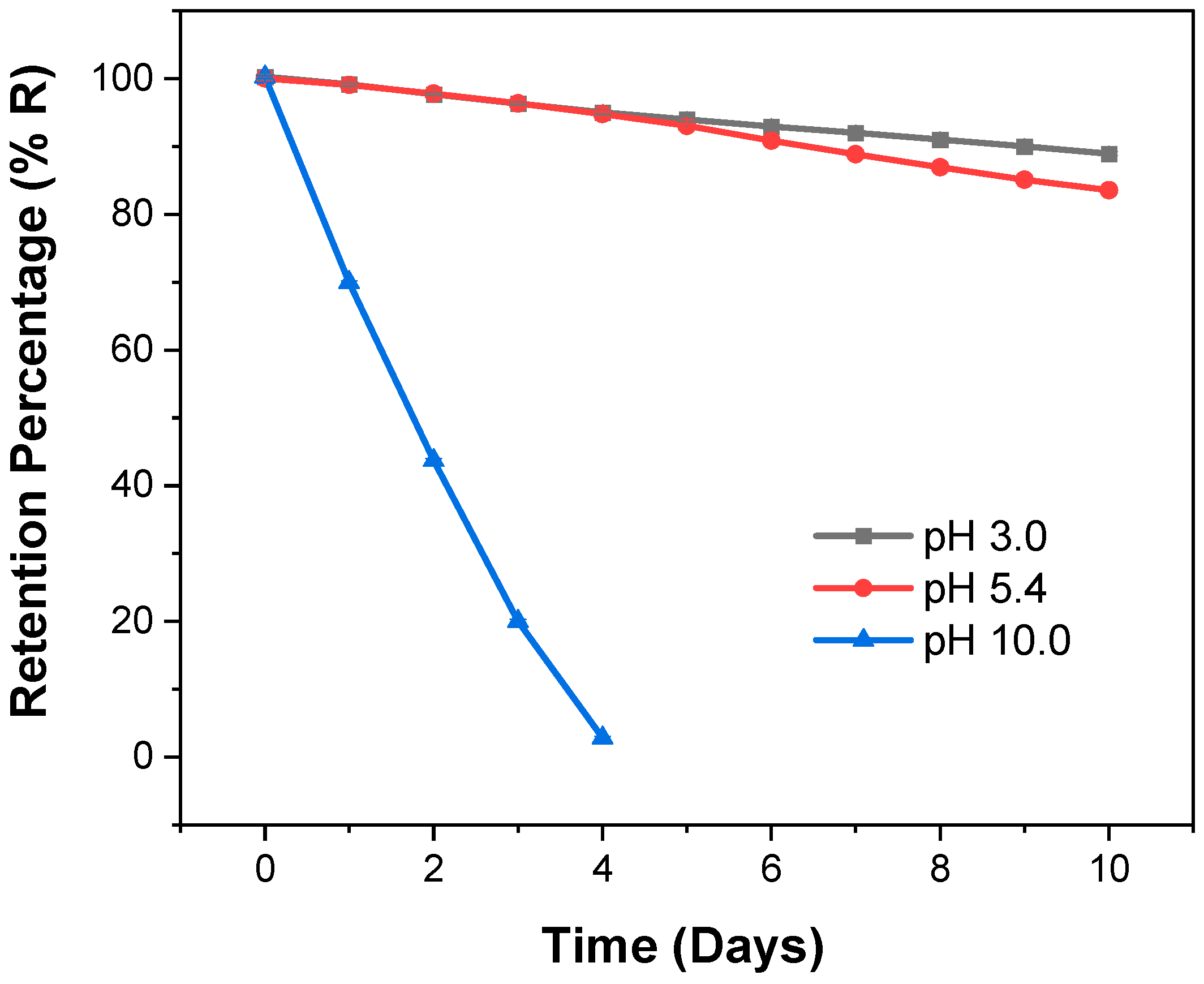

3.7. Controlled Release Hydrogels

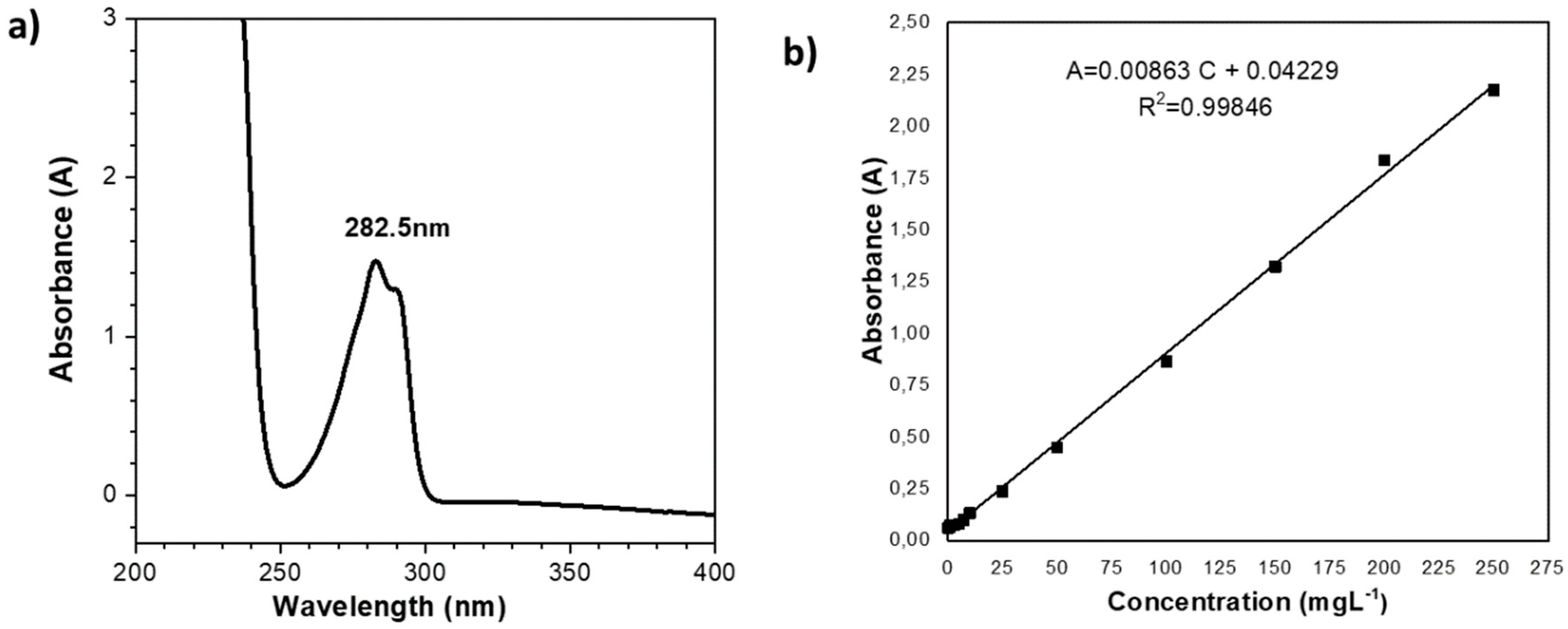

3.8. Release of Bioactive Agent: Kinetic of the Reaction

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Dahan, A.; Hoffman, A. Rationalizing the Selection of Oral Lipid Based Drug Delivery Systems by an in Vitro Dynamic Lipolysis Model for Improved Oral Bioavailability of Poorly Water Soluble Drugs. Journal of Controlled Release 2008, 129(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, Y. M.; Dickson, J. P.; Geckeler, K. E. Swelling and Diffusion Characteristics of Novel Semi-interpenetrating Network Hydrogels Composed of Poly[(Acrylamide)- Co -(Sodium Acrylate)] and Poly[(Vinylsulfonic Acid), Sodium Salt]. Polym Int 2007, 56(2), 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, Y. M.; Joseph, D. K.; Geckeler, K. E. Poly( N -isopropylacrylamide- Co -sodium Acrylate) Hydrogels: Interactions with Surfactants. J Appl Polym Sci 2007, 103(5), 3423–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaman, N.; Kazan, D.; Erarslan, A.; Okay, O.; Baysal, B. M. Structure and Protein Separation Efficiency of Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Gels: Effect of Synthesis Conditions. J Appl Polym Sci 1998, 67(5), 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Concheiro, A. Reversible Adsorption by a PH- and Temperature-Sensitive Acrylic Hydrogel. Journal of Controlled Release 2002, 80(1–3), 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.-R.; Shiah, J.-G.; Sakuma, S.; Kopečková, P.; Kopeček, J. Design of Novel Bioconjugates for Targeted Drug Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2002, 78(1–3), 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadaǧ, E.; Üzüm, Ö. B.; Saraydin, D. Swelling Equilibria and Dye Adsorption Studies of Chemically Crosslinked Superabsorbent Acrylamide/Maleic Acid Hydrogels. Eur Polym J 2002, 38(11), 2133–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantha, K. L.; Harding, D. R. K. Synthesis, Characterisation and Evaluation of Poly[Lactose Acrylate-N-Vinyl-2-Pyrrolidinone] Hydrogels for Drug Delivery. Eur Polym J 2003, 39(1), 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N. A.; Am Ende, D. J. Controlled Release of Perfumes from Polymers. II. Incorporation and Release of Essential Oils from Glassy Polymers. J Appl Polym Sci 1997, 66(3), 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, T.; Watanabe, T.; Kawabata, T.; Kurihara, S. Preparation of Thermosensitive and Superabsorbent Polymer Hydrogels from Trialkyl-4-Vinylbenzyl Phosphonium Chloride-N-Isopropylacrylamide-N,N?-Methylenebisacrylamide Copolymers and Their Properties. J Appl Polym Sci 2001, 79(1), 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idziak, I.; Avoce, D.; Lessard, D.; Gravel, D.; Zhu, X. X. Thermosensitivity of Aqueous Solutions of Poly( N,N -Diethylacrylamide). Macromolecules 1999, 32(4), 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del C Pizarro, G.; Marambio, O. G.; Jeria-Orell, M.; Avellán, M. C.; Rivas, B. L. Synthesis, Characterization and Application of Poly[(1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone)- Co -(2-hydroxyethyl Methacrylate)] as Controlled-release Polymeric System for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic Chloride Using an Ultrafiltration Technique. Polym Int 2008, 57(7), 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. X.; Brizard, F.; Piché, J.; Yim, C. T.; Brown, G. R. Bile Salt Anion Sorption by Polymeric Resins: Comparison of a Functionalized Polyacrylamide Resin with Cholestyramine. J Colloid Interface Sci 2000, 232(2), 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, Y. M.; Geckeler, K. E. Polyampholytic Hydrogels: Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide)-Based Stimuli-Responsive Networks with Poly(Ethyleneimine). React Funct Polym 2007, 67(2), 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, R. D. Inhibiting Water Infiltration into Soils with Cross-linked Polyacrylamide: Seepage Reduction for Irrigated Agriculture. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2007, 71(4), 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tally, M.; Atassi, Y. Optimized Synthesis and Swelling Properties of a PH-Sensitive Semi-IPN Superabsorbent Polymer Based on Sodium Alginate-g-Poly(Acrylic Acid-Co-Acrylamide) and Polyvinylpyrrolidone and Obtained via Microwave Irradiation. Journal of Polymer Research 2015, 22(9), 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Duan, B.; Cai, J.; Zhang, L. Superabsorbent Hydrogels Based on Cellulose for Smart Swelling and Controllable Delivery. Eur Polym J 2010, 46(1), 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, F. L.; Graham, A. T. Modern Superabsorbent Polymer Technology; 1998.

- Liu, M.; Liang, R.; Zhan, F.; Liu, Z.; Niu, A. Synthesis of a Slow-release and Superabsorbent Nitrogen Fertilizer and Its Properties. Polym Adv Technol 2006, 17(6), 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkert, S.; Schmidt, T.; Gohs, U.; Dorschner, H.; Arndt, K.-F. Cross-Linking of Poly(N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone) Films by Electron Beam Irradiation. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2007, 76(8–9), 1324–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E. M.; Aggor, F. S.; Awad, A. M.; El-Aref, A. T. An Innovative Method for Preparation of Nanometal Hydroxide Superabsorbent Hydrogel. Carbohydr Polym 2013, 91(2), 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Lu, T.; Lu, T. J.; Xu, F. Magnetic Hydrogels and Their Potential Biomedical Applications. Adv Funct Mater 2013, 23(6), 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh Pakdel, P.; Peighambardoust, S. J. A Review on Acrylic Based Hydrogels and Their Applications in Wastewater Treatment. J Environ Manage 2018, 217, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannazza, G.; Cataldo, A.; De Benedetto, E.; Demitri, C.; Madaghiele, M.; Sannino, A. Experimental Assessment of the Use of a Novel Superabsorbent Polymer (SAP) for the Optimization OfWater Consumption in Agricultural Irrigation Process. Water (Basel) 2014, 6(7), 2056–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S.; Nadeem, S.; Awan, Z.; Ghani, A. A. Synthesis, Applications and Swelling Properties of Poly (Sodium Acrylate-Coacrylamide) Based Superabsorbent Hydrogels. Journal of the Chemical Society of Pakistan 2019, 41(4), 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardarelli, N. Controlled Release Pesticides Formulations; Zweig, G., Ed.; CRC Press, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kydonieus, A. F. Controlled Release Technologies: Methods, Theory, and Applications; CRC Press, 1980; Vol. I.

- Das, K. G.; Patwardhan, S. A.; Collins, R. L.; Zeoli, L. T.; Kydonieus, A. F.; Wilkins, R. M.; Zweig, G.; Cardarelli, N. F.; Radick, C. M. Controlled-Release Technology: Bioengineering Aspects. (No Title).

- Baker, R. W. Controlled Release of Biologically Active Agents; Wiley, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Schnatter, W. F. K. Functionalized Polymers and Their Applications, by A. Akelah and A. Moet, Chapman and Hall, London, 1990, 345 Pp. Price: $79.95. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem 1992, 30(11), 2473–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E. R.; Sherrington, D. C.; Akelah, A. Controlled Release of Agrochemical Molecules Chemically Bound to Polymers. Eur Polym J 1992, 28(8), 841–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akelah, A.; Kenawy, E. R.; Sherrington, D. C. Hydrolytic Release of Herbicides from Modified Polyamides of Tartrate Derivatives. Eur Polym J 1995, 31(9), 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Martínez, A. R.; Lujan-Montelongo, J. A.; Silva-Cuevas, C.; Mota-Morales, J. D.; Cortez-Valadez, M.; Ruíz-Baltazar, Á. de J.; Cruz, M.; Herrera-Ordonez, J. Swelling and Methylene Blue Adsorption of Poly(N,N-Dimethylacrylamide-Co-2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate) Hydrogel. React Funct Polym 2018, 122, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, G. D. C.; Marambio, O. G.; Manuel Jeria, O.; Huerta, M.; Rivas, B. L. Nonionic Water-Soluble Polymer: Preparation, Characterization, and Application of Poly(1-Vinyl-2-Pyrrolidone-Co-Hydroxyetnylmethacrylate) as a Polychelatogen. J Appl Polym Sci 2006, 100(1), 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharekhani, H.; Olad, A.; Mirmohseni, A.; Bybordi, A. Superabsorbent Hydrogel Made of NaAlg-g-Poly(AA-Co-AAm) and Rice Husk Ash: Synthesis, Characterization, and Swelling Kinetic Studies. Carbohydr Polym 2017, 168, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetimoğlu, E. K.; Kahraman, M. V.; Ercan, Ö.; Akdemir, Z. S.; Apohan, N. K. N-Vinylpyrrolidone/Acrylic Acid/2-Acrylamido-2-Methylpropane Sulfonic Acid Based Hydrogels: Synthesis, Characterization and Their Application in the Removal of Heavy Metals. React Funct Polym 2007, 67(5), 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşdelen, B.; Çifçi, D. İ.; Meriç, S. Preparation of N-Isopropylacrylamide/Itaconic Acid/Pumice Highly Swollen Composite Hydrogels to Explore Their Removal Capacity of Methylene Blue. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2017, 519, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, M.; Franklin, D. S.; Guhanathan, S. PH-Sensitive Itaconic Acid Based Polymeric Hydrogels for Dye Removal Applications. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2016, 134, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, J. R. In the Beginning: The Multiple Discovery of the First Hormone Herbicides. Weed Sci 2001, 49(2), 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, G. del C.; Marambio, O. G.; O, M. J.; Geckeler, K. E. Synthesis and Properties of Hydrophilic Polymers, 10. Macromol Chem Phys 2003, 204(7), 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del C. Pizarro, G.; Marambio, O. G.; Jeria-Orell, M.; Huerta, M. R.; Rivas, B. L.; Habicher, W. D. Metal Ion Retention Using the Ultrafiltration Technique. Preparation, Characterization of the Water-soluble Poly(1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone- Co -itaconic Acid) and Its Metal Complexes in Aqueous Solutions. J Appl Polym Sci 2008, 108(6), 3982–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüdos, F.; Kelen, T.; Turcsányi, B.; Kennedy, J. P. Analysis of the Linear Methods for Determining Copolymerization Reactivity Ratios. VI. A Comprehensive Critical Reexamination of Oxonium Ion Copolymerizations. Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Chemistry Edition 1981, 19(5), 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineman, M.; Ross, S. D. Linear Method for Determining Monomer Reactivity Ratios in Copolymerization. Journal of Polymer Science 1950, 5(2), 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weast, R. C. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 53rd Edition; Chemical Rubber Pub., 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Peppas, N. A.; Khare, A. R. Preparation, Structure and Diffusional Behavior of Hydrogels in Controlled Release. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 1993, 11(1–2), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marambio, O. G.; Sánchez, J.; del C. Pizarro, G.; Jeria-Orell, M. Rivas, B. L. Free Radical Copolymerization of Functional Water-Soluble Poly(N-Maleoylglycine-Co-Crotonic Acid): Polymer Metal Ion Retention Capacity, Electrochemical and Thermal Behavior. Polymer Bulletin 2010, 65(7), 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Villoslada, I. Retention of Metal Ions in Ultrafiltration of Mixtures of Divalent Metal Ions and Water-Soluble Polymers at Constant Ionic Strength Based on Freundlich and Langmuir Isotherms. J Memb Sci 2003, 215(1–2), 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIVAS, B. L.; SCHIAPPACASSE, L. N.; PEREIRAU, E.; MORENO-VILLOSLADA, I. ERROR SIMULATION IN THE DETERMINATION OF THE FORMATION CONSTANTS OF POLYMER-METAL COMPLEXES (PMC) BY THE LIQUID-PHASE POLYMER-BASED RETENTION (LPR) TECHNIQUE. Journal of the Chilean Chemical Society 2004, 49(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, G. C. del; Marambio, O. G.; Rivas, B. L.; Geckeler, K. E. Interactions of the Water-Soluble Poly(N-Maleyl Glycine- Co -Acrylic Acid) as Polychelatogen with Metal Ions in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A 1997, 34(8), 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, B. L.; Pooley, S. A.; Luna, M. Ultrafiltration of Metal Ions by Water-soluble Chelating Poly( N -acryloyl- N -methylpiperazine- Co-N -acetyl-α-aminoacrylic Acid). J Appl Polym Sci 2002, 83(12), 2556–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, G. del C.; Rivas, B. L.; Geckeler, K. E. Metal Complexing Properties of Water-Soluble Poly(N-Maleyl Glycine) Studied by the Liquid-Phase Polymer-Based Retention (LPR) Technique. Polymer Bulletin 1996, 37(4), 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Monomer feed ratios HEMA/IA |

HEMA mL (mmol) |

IA g (mmol) |

PSA mg (mol-%) |

Yield % |

Copolymer composition by 1H NMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0:1.0 | 4.51 (9.00) |

1.59 (3.00) |

53.6 (0.490) |

37.7 | 3.0:1.0 |

| 2.5:1.0 | 4.30 (8.60) |

1.80 (3.40) |

54.1 (0.494) |

37.3 | 2.5:1.0 |

| 2.0:1.0 | 4.01 (8.00) |

2.10 (4.00) |

54.4 (0.497) |

32.4 | 2.0:1.0 |

| 1.5:1.0 | 3.61 (7.20) |

2.53 (4.80) |

54.5 (0.498) |

27.1 | 1.5:1.0 |

| 1.0:1.0 | 3.01 (6.00) |

3.16 (6.00) |

54.5 (0.498) |

28.5 | 1.0:1.0 |

| 1.0:1.5 | 2.41 (4.80) |

3.79 (7.20) |

55.9 (0.510) |

46.5 | 1.0:1.5 |

| 1.0:2.0 | 2.01 (4.00) |

4.22 (8.00) |

56.0 (0.511) |

42.0 | 1.0:2.0 |

| 1.0:2.5 | 1.72 (3.40) |

5.51 (8.60) |

56.4 (0.515) |

38.6 | 1.0:2.5 |

| 1.0:3.0 | 1.51 (3.00) |

4.75 (9.00) |

55.4 (0.506) |

30.0 | 1.0:3.0 |

| System |

pH 3.0 |

pH 5.4 |

pH 10.0 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

k (n) |

τ1/2 (days) |

k (n) |

τ1/2 (days) |

k (n) |

τ1/2 (days) |

|

| Poly(HEM -co- IA)-2,4-D | 0.011 (0.988) |

63.01 | 0.019 (0.981) |

36.48 | 0.857 (0.424) |

0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).