Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

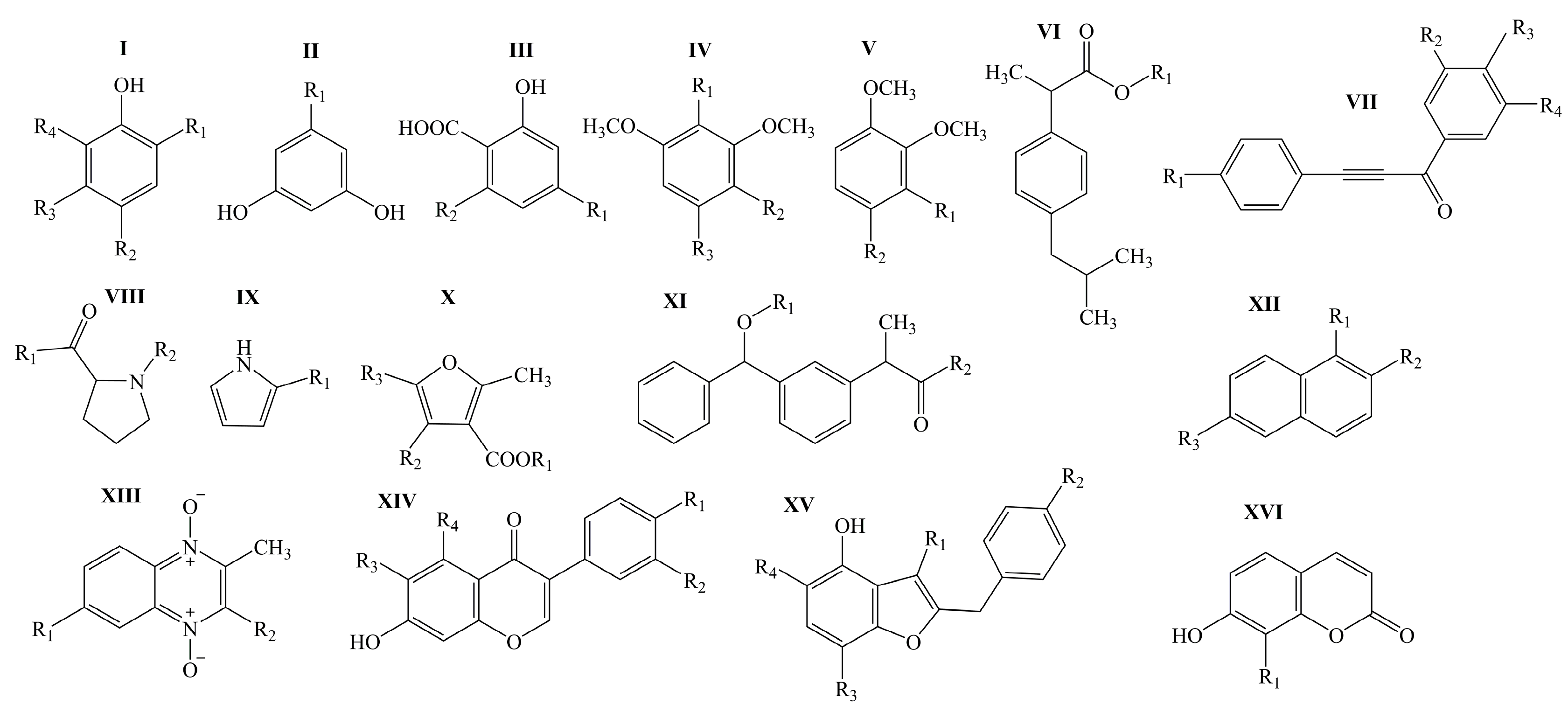

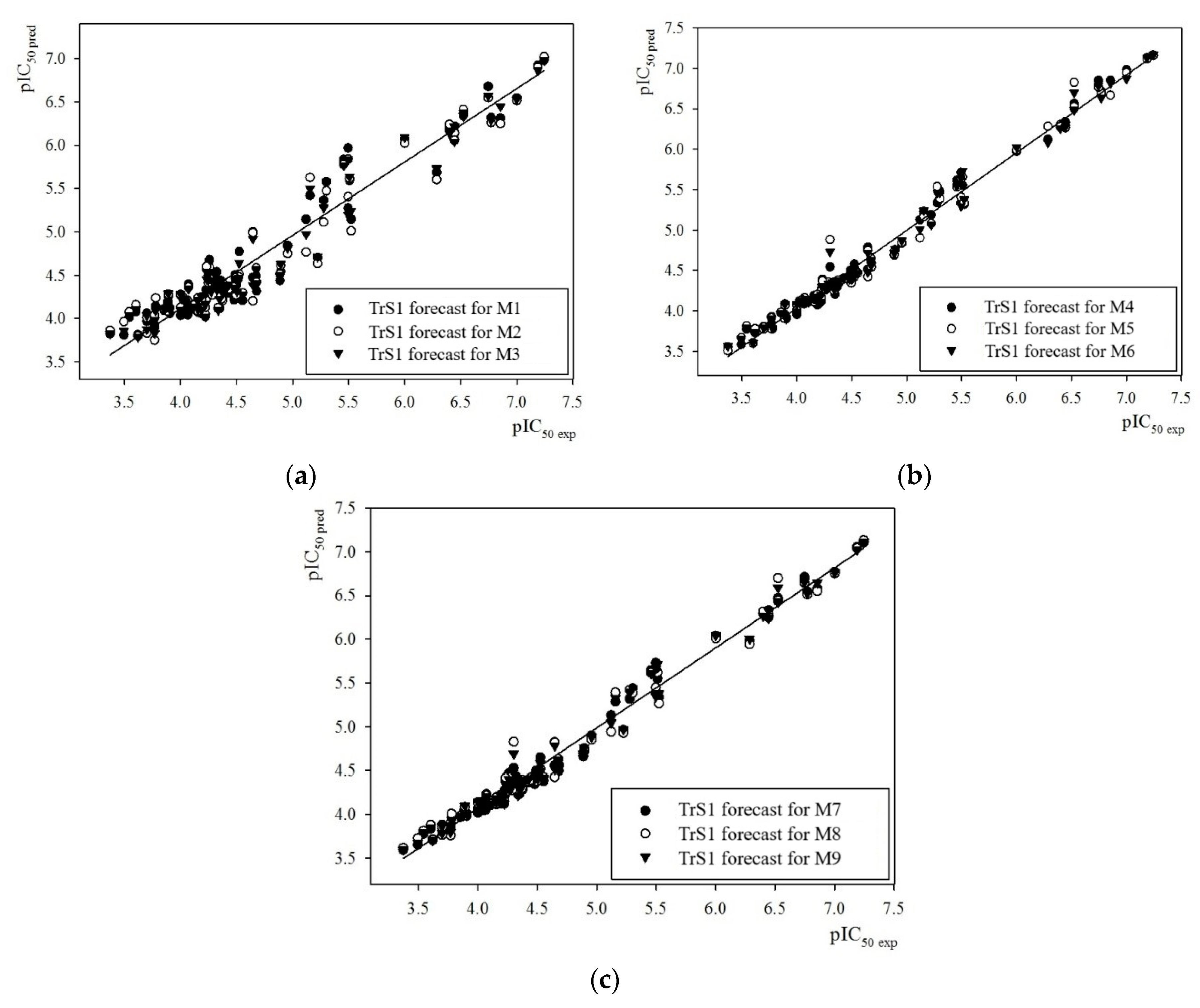

2.1. Prediction of the Numerical Values of the IC50 Parameter Using the GUSAR 2019 Program

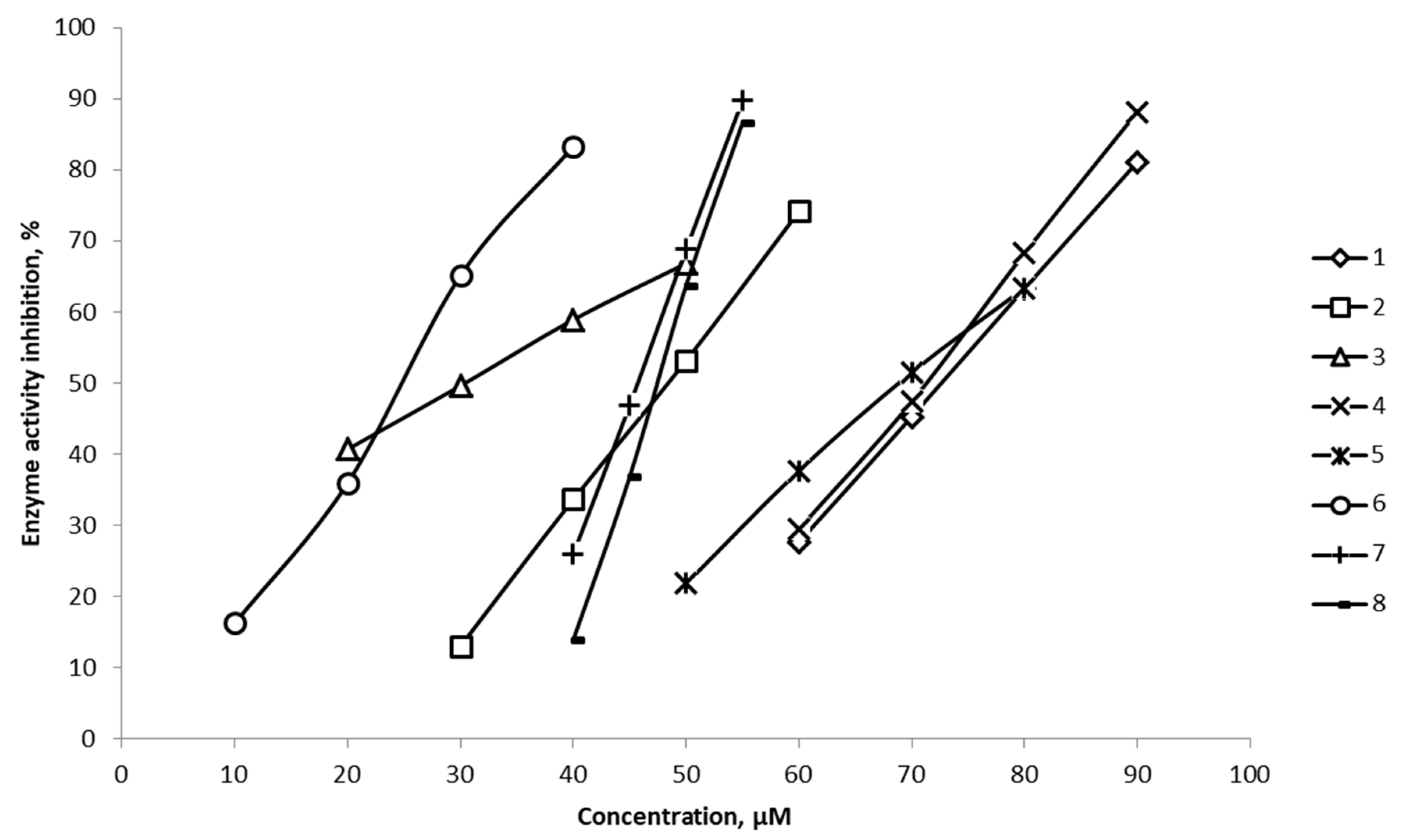

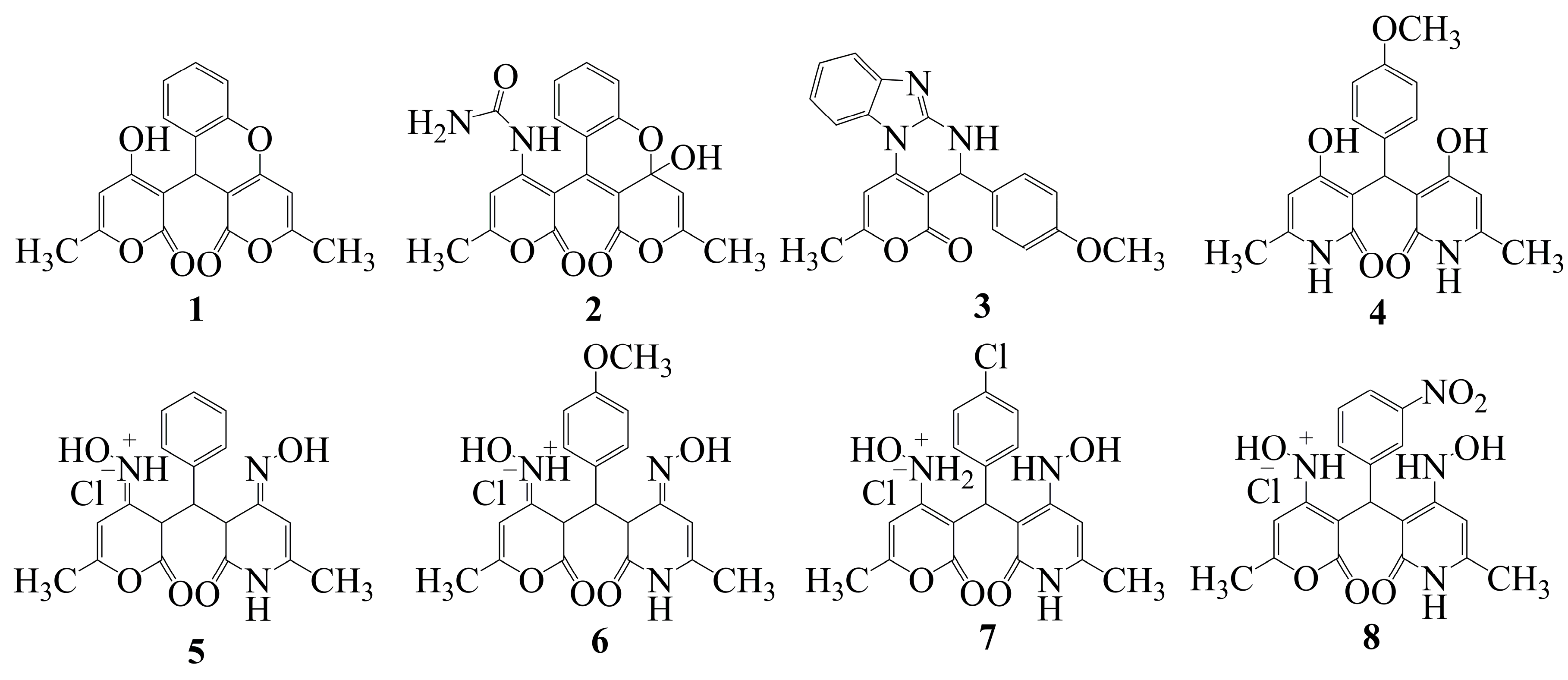

2.2. Experimental Determination of the IC50 Parameter Against 15-LOX for Compounds 1–8

2.3. Evaluation of the predictive ability of the M3, M6, M9, M12, M15, and M18 models based on Compounds 1–8 in the Test Set TS3

3. Research Methods

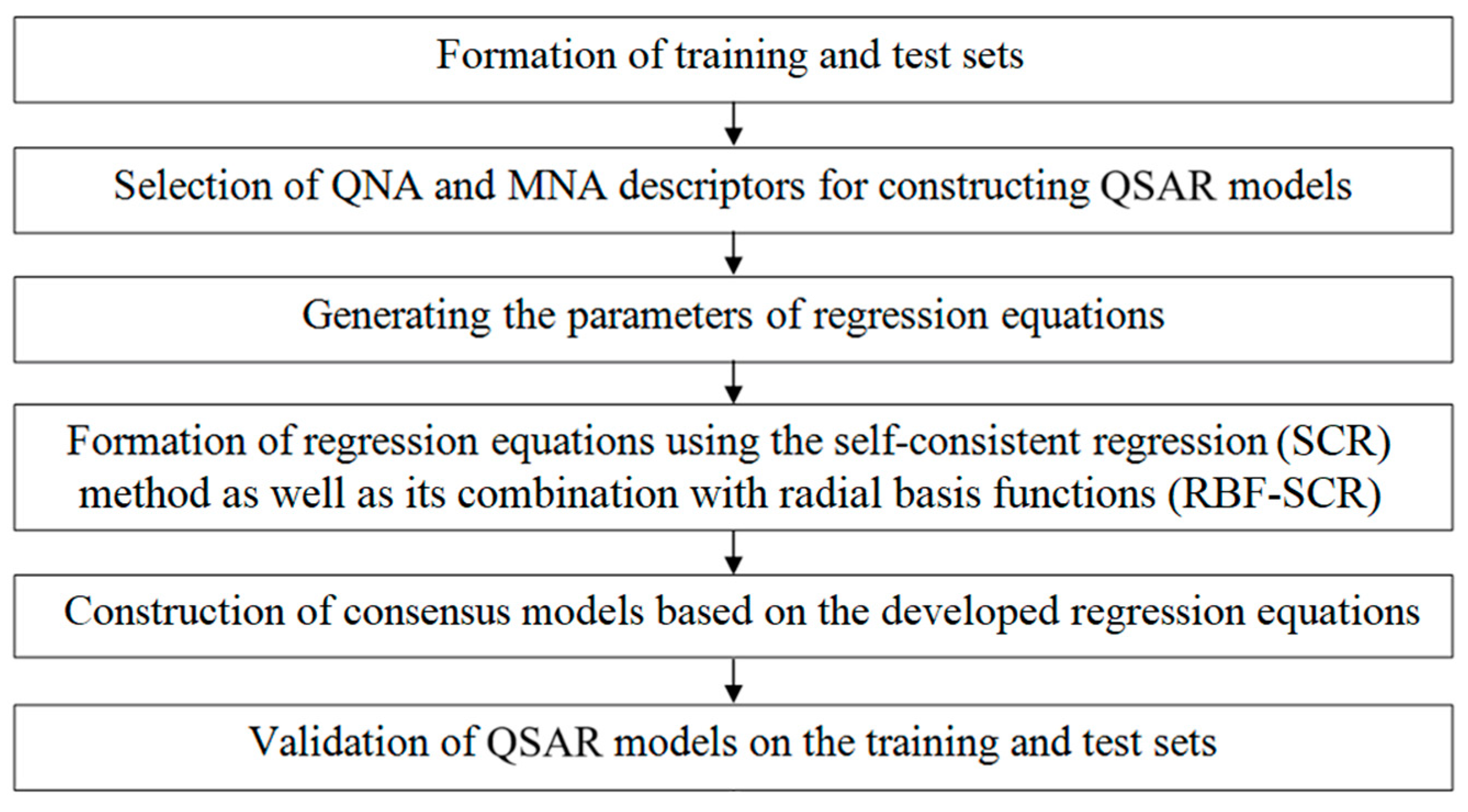

3.1. The Methodology of the Computational Experiment

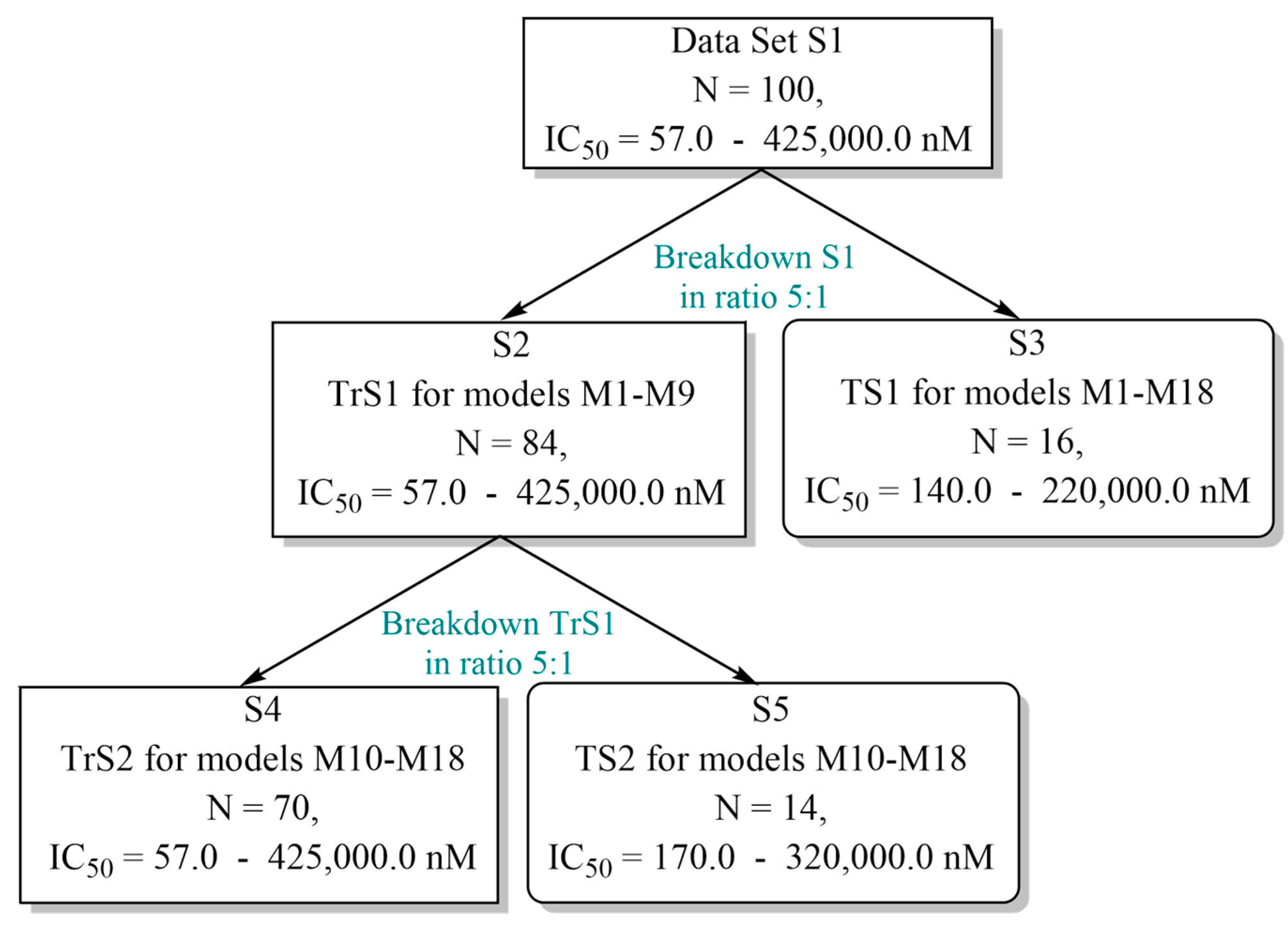

3.2. Formation of the Training and Test Sets

3.3. Building QSAR Models

- Zero-level MNA descriptor for each atom is the mark A of the atom itself;

- Any next-level MNA descriptor for the atom is the substructure notation A (D1D2 … Di …), where Di is the previous-level MNA descriptor for i–th immediate neighbor of the atom A.

- Self-consistent regression (SCR) method;

- The method of combining self-consistent regression with radial basis functions (RBF-SCR);

- The Bath method, which combines the simultaneous use of SCR and RBF-SCR methods in a unique way.

3.4. Evaluation of the Descriptive and Predictive Ability of QSAR Models

3.5. The Technique of the Biochemical Experiment to Measure Inhibitory Activity

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joo, Y.-C., & Oh, D.-K. (2012). Lipoxygenases: Potential starting biocatalysts for the synthesis of signaling compounds. Biotechnology Advances, 30(6), 1524–1532. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert NC, Bartlett SG, Waight MT, Neau DB, Boeglin WE, Brash AR, Newcomer ME. The structure of human 5-lipoxygenase. Science. 2011 Jan 14;331(6014):217-9. PMID: 21233389; PMCID: PMC3245680. [CrossRef]

- Johannesson, M., Backman, L., Claesson, H.-E., & Forsell, P. K. A. (2010). Cloning, purification and characterization of non-human primate 12/15-lipoxygenases. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 82(2-3), 121–129. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, C., Hofheinz, K., Vogel, R., Roffeis, J., Anton, M., Reddanna, P., … Walther, M. (2011). Stereocontrol of Arachidonic Acid Oxygenation by Vertebrate Lipoxygenases. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 286(43), 37804–37812. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, I. F., Laparra, H., Romero, S. P., Schmelz, E., Hamberg, M., Mottinger, J. P., … Dellaporta, S. L. (2009). tasselseed1 Is a Lipoxygenase Affecting Jasmonic Acid Signaling in Sex Determination of Maize. Science, 323(5911), 262–265. [CrossRef]

- Szymanowska, U., Jakubczyk, A., Baraniak, B., & Kur, A. (2009). Characterisation of lipoxygenase from pea seeds (Pisum sativum var. Telephone L.). Food Chemistry, 116(4), 906–910. [CrossRef]

- Senger, T., Wichard, T., Kunze, S., Göbel, C., Lerchl, J., Pohnert, G., & Feussner, I. (2004). A Multifunctional Lipoxygenase with Fatty Acid Hydroperoxide Cleaving Activity from the MossPhyscomitrella patens. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 280(9), 7588–7596. [CrossRef]

- Reet Koljak, Olivier Boutaud, Bih-Hwa Shieh, Nigulas Samel and Alan R. Brash Identification of a Naturally Occurring Peroxidase-Lipoxygenase Fusion Protein Source: Science, New Series, Vol. 277, No. 5334 (Sep. 26, 1997), pp. 1994-1996.

- Mortimer, M., Järving, R., Brash, A. R., Samel, N., & Järving, I. (2006). Identification and characterization of an arachidonate 11R-lipoxygenase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 445(1), 147–155. [CrossRef]

- Andreou, A., & Feussner, I. (2009). Lipoxygenases – Structure and reaction mechanism. Phytochemistry, 70(13-14), 1504–1510. [CrossRef]

- Bisakowski, B., Atwal, A. S., & Kermasha, S. (2000). Characterization of lipoxygenase activity from a partially purified enzymic extract from Morchella esculenta. Process Biochemistry, 36(1-2), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Brodhun F, Feussner I. Oxylipins in fungi. FEBS J. 2011 Apr;278(7):1047-63 . Epub 2011 Feb 23. Erratum in: FEBS J. 2011 Jul;278(14):2609-10. PMID: 21281447. [CrossRef]

- Shechter, G., & Grossman, S. (1983). Lipoxygenase from baker’s yeast: Purification and properties. International Journal of Biochemistry, 15(11), 1295–1304. [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, K.K., Varakumar, P., Pamuru, R.R. et al. Plant Lipoxygenases and Their Role in Plant Physiology. J. Plant Biol. 63, 83–95 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Haeggström, J. Z., & Funk, C. D. (2011). Lipoxygenase and Leukotriene Pathways: Biochemistry, Biology, and Roles in Disease. Chemical Reviews, 111(10), 5866–5898. [CrossRef]

- Okunishi, K., & Peters-Golden, M. (2011). Leukotrienes and airway inflammation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects, 1810(11), 1096–1102. [CrossRef]

- Allmann, S.. Halitschke, R.. Schuurink, R.C. and Baldwin, I.T. (2010) Oxylipin channelling in Nicotiana attenuata: lipoxygenase 2 supplies substrates for green leaf volatile production. Plant. Cell & Environment, 33 (12), 2028-2040. [CrossRef]

- Georg von Mérey, Nathalie Veyrat, George Mahuku, Raymundo Lopez Valdez, Ted C J Turlings, Marco D'Alessandro Dispensing synthetic green leaf volatiles in maize fields increases the release of sesquiterpenes by the plants, but has little effect on the attraction of pest and beneficial insects // Phytochemistry. 2011 Oct;72(14-15):1838-47.. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J. S., S. J. Himanen, J. K. Holopainen, F. Chen, and C. N. Stewart. 2009. Smelling global climate change: mitigation of function for plant volatile organic compounds. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 24: 323-331. 10.1016/j.tree.2009.01.012.

- Allmann, S. and Baldwin, I.T. (2010) Insects Betray Themselves in Nature to Predators by Rapid Isomerization of Green Leaf Volatiles. Science (New York, N.Y) 329(5995):1075-1078. [CrossRef]

- Mosblech A, Feussner I, Heilmann I (2009) Oxylipins: structurally diverse metabolites from fatty acid oxidation. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Volume 47, Issue 6, June 2009, Pages 511-517. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.-C., & Schwab, W. (2011). Cloning and characterization of a 9-lipoxygenase gene induced by pathogen attack from Nicotiana benthamiana for biotechnological application. BMC Biotechnology, 11(1), 30. [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, K. K., Varakumar, P., Pamuru, R. R., Basha, S. J., Mehta, S., & Rao, A. D. (2020). Plant Lipoxygenases and Their Role in Plant Physiology. Journal of Plant Biology. [CrossRef]

- Andreou A., Feussner I. Lipoxygenases – Structure and reaction mechanism // Phytochemistry. 2009. V. 70. P. 1504–1510.

- Upston J.M., Neuzil J., Witting P.K., Alleva R., Stocker R. Oxidation of free fatty acids in low density lipoprotein by 15-lipoxygenase stimulates nonenzymic, alpha-tocopherol-mediated peroxidation of cholesteryl esters // J. Biol. Chem. 1997. V. 272. P. 30067–30074.

- Takahashi Y., Glasgow W.C., Suzuki H., Taketani Y., Yamamoto S., Anton M., Kuhn H., Brash A.R. Investigation of the oxygenation of phospholipids by the porcine leukocyte and human platelet arachidonate 12-lipoxygenases // Eur. J. Biochem. 1993. V. 218. P. 165–171.

- Mao, F., Wu, Y., Tang, X., Wang, J., Pan, Z., Zhang, P., … Xu, W. (2017). Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate inflammatory bowel disease through the regulation of 15-LOX-1 in macrophages. Biotechnology Letters, 39(6), 929–938. [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, M.A., Safizadeh, B., Eghtedari, A.R. et al. 15-Lipoxygenase and its metabolites in the pathogenesis of breast cancer: A double-edged sword. Lipids Health Dis 20, 169 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hao Guo, Iris C. Verhoek, Gerian G. H. Prins, Ramon van der Vlag, Petra E. van der Wouden, Ronald van Merkerk, Wim J. Quax, Peter Olinga, Anna K. H. Hirsch, and Frank J. Dekker Novel 15-Lipoxygenase-1 Inhibitor Protects Macrophages from Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cytotoxicity // Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2019 62 (9), 4624-4637 . [CrossRef]

- Hong SH, Avis I, Vos MD, Martínez A, Treston AM, Mulshine JL. Relationship of arachidonic acid metabolizing enzyme expression in epithelial cancer cell lines to the growth effect of selective biochemical inhibitors. Cancer Res. 1999;59(9):2223–8.

- Orafaie, A., Mousavian, M., Orafai, H., & Sadeghian, H. (2020). An overview of lipoxygenase inhibitors with approach of in vivo studies. Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators, 106411. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Ramírez A, Mascayano-Collado C, Barriga A, Echeverría J and Urzúa A (2020) Inhibition of Soybean 15-Lipoxygenase and Human 5-Lipoxygenase by Extracts of Leaves, Stem Bark, Phenols and Catechols Isolated From Lithraea caustica (Anacardiaceae). Front. Pharmacol. 11:594257. [CrossRef]

- Wecksler, A. T., Garcia, N. K., and Holman, T. R. (2009). Substrate specificity effects of lipoxygenase products and inhibitors on soybean lipoxygenase-1. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 6534–6539. [CrossRef]

- Verma, J.; Khedkar, V.M.; Coutinho, E.C. 3D-QSAR in drug design-a review. J. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 95-115. [CrossRef]

- Kubinyi, H. Theory Methods and Applications. In QSAR in Drug Design; Kubinyi, H., Eds.; Kluwer/Escom: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1993; Volume 1, pp. 759.

- Kubinyi, H. QSAR and 3D QSAR in drug design Part 1: methodology. Drug discovery today 1997, 2, 457-467. [CrossRef]

- Nantasenamat, C.; Prachayasittikul, V.; Isarankura-Na-Ayudhya, C.; Naenna, T. A Practical Overview of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship. EXCLI J. 2009, 8, 74- 88. [CrossRef]

- Kubinyi, H. QSAR: Hansch analysis and related approaches. In Methods and principles in medicinal chemistry; Kubinyi, H., Mannhold, R., Krogsgaard-Larsen, P., Timmerman, H., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 993.

- Baskin, I.I. Modeli rovanie «struktura – svojstvo». In Vvedenie v hemoinformatiku; Baskin, I.I., Madzhidov, T.I., Antipin, I.S., Varnek, A.A., Eds.; Nauchno-izdatel'skij centr “Akademiya estestvoznaniya”: Kazan, Russia, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 304.

- Veselovsky, A.V.; Ivanov S. Strategy of computer-aided drug design. Curr. Drug Targets-Infectious Disorders 2003, 3, 33-40. [CrossRef]

- Damale, M.G.; Harke, S.N.; Kalam Khan, F.A.; Shinde, D.B.; Sangshetti, J.N. Recent advances in multidimensional QSAR (4D-6D): a critical review J. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 35-55. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.L.J.; Tropsha, A.; Winkler, D.A. Beware of R2: Simple, Unambiguous Assessment of the Prediction Accuracy of QSAR and QSPR Models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 1316-1322. [CrossRef]

- Ambure, P.; Gajewicz-Skretna, A.; Cordeiro, M.N.D.S.; Roy, K. New Workflow for QSAR Model Development from Small Data Sets: Small Dataset Curator and Small Dataset Modeler. Integration of Data Curation, Exhaustive Double Cross-Validation, and a Set of Optimal Model Selection Techniques. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Dearden, J.C.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Kaiser, K.L.E. How not to develop a quantitative structure-activity or structure-property relationship (QSAR/QSPR). J. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2009, 20, 241-266. [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.P.; Paul, S.; Mitra, I.; Roy, K. On Two Novel Parameters for Validation of Predictive QSAR Models. J. Molecules 2009, 14, 1660-1701. [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Ambure, P.; Kar, S. How Precise Are Our Quantitative Structure−Activity Relationship Derived Predictions for New Query Chemicals? J. ASC Omega 2018, 3, 11392-11406. [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.A.; Romanova, M.A.; Zadorozhny, A.D.; Kurilenko, N.S.; Shilov, B.V.; Pogodin, P.V.; Ivanov, S.M.; Filimonov, D.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Comparison of Quantitative and Qualitative (Q)SAR Models Created for the Prediction of Ki and IC50 Values of Antitarget Ingibitors. J. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1136. [CrossRef]

- Taipov, I.A.; Khayrullina, V.R.; Khoma, V.K.; Gerchikov, A.Ja.; Zarudiy, F.S.; Bege, Kh. Virtual screening in the row of effective inhibitor of catalytic activity-A4-hydrolase. J. Vestnik Bashkir. Univ. 2012, 17, 886-891.

- Tarasov, G.P.; Khayrullina, V.R.; Gertchikov, A.Ja.; Kirlan, S.A.; Zarudiy, Ph.S. Derivatives of 4-amino-n-[2-(dietilamino) ethyl] benzamids as potentially low-toxic substances with expressed antiarrhytmic action. J. Vestnik Bashkir. Univ. 2012, 17, 1242-1246.

- Khayrullina, V.R.; Kirlan, S.A.; Gerchikov, A.Ja.; Zarudiy, F.S.; Dimoglo, A.S.; Kantor E.A. Modeling of structures of anti-inflammatory heterocyclic compounds with their toxicity. J. Baskir. Khim. Zh. 2010, 17, 76-79.

- Liu, J.; Pan, D.; Tseng, Y.; Hopfinger, A.J. 4D-QSAR analysis of a series of antifungal p450 inhibitors and 3D-pharmacophore comparisons as a function of alignment. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 2170-2179. [CrossRef]

- Scior, T.; Medina-Franco, J.L.; Do, Q.-T.; Martínez-Mayorga, K.; Yunes Rojas, J.A.; Bernard, P. How to recognize and workaround pitfalls in QSAR studies: a critical review. J. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 4297-4313. [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.A.; Geronikaki, A.; Eleftheriou, P.; Pogodin, P.V. Rational Use of Heterogeneous Data in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling of Cyclooxygenase/Lipoxygenase Inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 713-730. [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Kar, S.; Narayan Das, R. Fundamental Concepts. In A Primer on QSAR/QSPR Modeling; Roy, K., Kar, S., Narayan Das, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, USA, 2015, pp. 129. [CrossRef]

- Dastmalchi, S.; Hamzeh-Mivehroud, M.; Sokouti, B. A Practical Approach. In Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship; Dastmalchi, S., Hamzeh-Mivehroud, M., Sokouti, B., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2018, pp. 115. [CrossRef]

- Roy, K. Applications in Pharmaceutical, Chemical, Food, Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. In Advances in QSAR Modeling; Roy, K., Eds.; Springer: Jackson, USA, 2017, Volume 24, pp. 555. [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Kar, S.; Ambure, P. On a simple approach for determining applicability domain of QSAR models. J. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2015, 145, 22-29. [CrossRef]

- Verma, J.; Malde, A.; Khedkar, S.; Iyer, R.; Coutinho E. Local indices for similarity analysis (LISA)-a 3D-QSAR formalism based on local molecular similarity. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 2695-2707. [CrossRef]

- Hopfinger, A.; Wang, S.; Tokarski, J.; Jin, B.; Albuquerque, M.G.; Madhav, P.J.; Duraiswami, C. Construction of 3D-QSAR Models Using the 4D-QSAR Analysis Formalism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 10509-10524. [CrossRef]

- Khayrullina, V.R.; Gerchikov, A.Ya.; Lagunin, A.A.; Zarudii, F.S. Quantitative Analysis of Structure−Activity Relationships of Tetrahydro-2H-isoindole Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitors. J. Biokhimiya 2015, 80, 74-86. [CrossRef]

- Khairullina, V.R.; Akbasheva, Y.Z.; Gimadieva, A.R.; Mustafin, A.G. Analysis of the relationship «structure-activity» in theseries of certain 5-ethyluridine derivatives with pronounced anti-herpetic activity. J. Vestnik Bashk. Univ. 2017, 22, 960-965.

- Khairullina, V.R.; Gerchikov, A.Ya.; Lagunin, A.A.; Zarudii, F.S. QSAR modeling of thymidilate synthase inhibitors in a series of quinazoline derivatives. J. Pharm. Chem. 2018, 51, 884-888. [CrossRef]

- Khairullina, V.R.; Gimadieva, A.R.; Gerchikov, A.Ja.; Mustafin, A.G.; Zaarudii, F.S. Quantitative structure–activity relationship of the thymidylate synthase inhibitors of Mus musculus in the series of quinazolin-4-one and quinazolin-4-imine derivatives. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2018, 85, 198-211. [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, A.V.; Lagunin, A.A.; Filimonov, D.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Quantitative prediction of antitarget interaction profiles for chemical compounds. J. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 2378-2385. [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Zakharov, A.V.; Lagunin, A.A.; Poroikov, V.V. QNA based “Star Track” QSAR approach. SAR and QSAR Environ. J. Resolut. 2009, 20, 679-709. [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, A.V.; Peach, M.L.; Sitzmann, M.; Nicklaus, M.C. A New Approach to Radial basis function approximation and Its application to QSAR. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 713-719. [CrossRef]

- Martynova, Y.Z.; Khairullina, V.R.; Biglova, Y.N.; Mustafin, A.G. Quantitative structure-property relationship modeling of the C60 fullerene derivatives as electron acceptors of polymer solar cells: Elucidating the functional groups critical for device performance. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2019, 88, 49-61. [CrossRef]

- Martynova, Yu.Z.; Khairullina, V.R.; Gimadieva, A.R.; Mustafin, A.G. QSAR-Modeling of desoxyuridine triphosphatase inhibitors in a series of some derivatives of uracil. J. Biomed. Chem. 2019, 65, 103-113. [CrossRef]

- Martynova, Yu.Z.; Khairullina, V.R.; Nasretdinova, R.N.; Garifullina, G.G.; Mitsukova, D.S.; Gerchikov, A.Ya; Mustafin, A.G. Determination of the chain termination rate constants of the radical chain oxidation of organic compounds on antioxidant molecules by the QSPR method. J. Russ. Chem. Bull., Int. Ed. 2020, 69, 1679-1691. [CrossRef]

- Khairullina, V.; Safarova, I.; Sharipova, G.; Martynova, Y.; Gerchikov, A. QSAR Assessing the Efficiency of Antioxidants in the Termination of Radical-Chain Oxidation Processes of Organic Compounds. J. Mol. 2021, 26, 421. [CrossRef]

- Martynova, Yu.Z.; Khairullina, V.R.; Garifullina, G.G.; Mitsukova, D.S.; Zarudiy, F.S.; Mustafin, A.G. QSAR-modeling of the relationship “structure – antioxidative activity” in a series of some benzopirane and benzofurane derivatives. J. Vestnik Bashk. Univ. 2019, 24, 573-580. [CrossRef]

- Martynova, Yu.Z.; Khairullina, V.R.; Gerchikov, A.Ya; Zarudiy, F.S.; Mustafin, A.G. QSPR-modeling of antioxidant activity of potential and industrial used stabilizers from the class of substituted alkylphenols. J. Vestnik Bashk. Univ. 2020, 25, 723-730. [CrossRef]

- Khairullina, V.; Martynova, Yu.; Safarova, I.; Sharipova, G.; Gerchikov, A.; Limantseva, R.; Savchenko, R. QSPR Modeling and Experimental Determination of the Antioxidant Activity of Some Polycyclic Compounds in the Radical-Chain Oxidation Reaction of Organic Substrates. J. Mol. 2022, 27, 6511. [CrossRef]

- Khairullina, V.R.; Martynova, Yu.Z. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship in the Series of 5-Ethyluridine, N2-Guanine, and 6-Oxopurine Derivatives with Pronounced Anti-Herpetic Activity. J. Mol. 2023, 28, 7715. [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam J., Gajbhiye R.L., Mandal L., Arumugam M., Achari A., Jaisankar P. Substituted furans as potent lipoxygenase inhibitors: Synthesis, in vitro and molecular docking studies // Bioorganic Chemistry. – 2017. – V. 71. – P. 97-101.

- Siskou I.C., Rekka E.A., Kourounakis A.P., Chrysselis M.C., Tsiakitzis K., Kourounakis P.N. Design and study of some novel ibuprofen derivatives with potential nootropic and neuroprotective properties // Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. – 2007. – V. 15, No. 2. – P. 951-961.

- Pontiki E., Hadjipavlou-Litina D. Synthesis and pharmacochemical evaluation of novel aryl-acetic acid inhibitors of lipoxygenase, antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory agents // Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. – 2007. – V. 15, No. 17. – P. 5819-5827.

- Wisastra R., Ghizzoni M., Boltjes A., Haisma H.J., Dekker F.J. Anacardic acid derived salicylates are inhibitors or activators of lipoxygenases // Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. – 2012. – V. 20, No. 16. – P. 5027-5032.

- Rao P.N.P., Chen Q.-H., Knaus E.E. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 1,3-diphenylprop-2-yn-1-ones as dual inhibitors of cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases // Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. – 2005. – V. 15, No. 21. – P. 4842-4845.

- Doulgkeris C.M., Galanakis D., Kourounakis A.P., Tsiakitzis K.C., Gavalas A.M., Eleftheriou P.T., Victoratos P., Rekka E.A., Kourounakis P.N. Synthesis and pharmacochemical study of novel polyfunctional molecules combining anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and hypocholesterolemic properties // Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. – 2006. – V. 16, No. 4. – P. 825-829.

- Burguete A., Pontiki E., Hadjipavlou-Litina D., Villar R., Vicente E., Solano B., Ancizu S., Pérez-Silanes S., Aldana I., Monge A. Synthesis and anti-inflammatory/antioxidant activities of some new ring substituted 3-phenyl-1-(1,4-di-N-oxide quinoxalin-2-yl)-2-propen-1-one derivatives and of their 4,5-dihydro-(1H)-pyrazole analogues // Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. – 2007. – V. 17, No. 23. – P. 6439-6443.

- Lau C.K., Belanger P.C., Scheigetz J., Dufresne C., Williams H.W.R., Maycock A.L., Guindon Y., Bach T., Dallob A.L. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of a novel class of 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors. 2-(Phenylmethyl)-4-hydroxy-3,5-dialkylbenzofurans: the development of L-656,224 // Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. – 1989. – V. 32, No. 6. – P. 1190-1197.

- Whitman S., Gezginci M., Timmermann B.N., Holman T.R. Structure−Activity Relationship Studies of Nordihydroguaiaretic Acid Inhibitors toward Soybean, 12-Human, and 15-Human Lipoxygenase // Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. – 2002. – V. 45, No. 12. – P. 2659-2661.

- Rao P.P.N., Chen Q.-H., Knaus E.E. Synthesis and Structure−Activity Relationship Studies of 1,3-Diarylprop-2-yn-1-ones: Dual Inhibitors of Cyclooxygenases and Lipoxygenases // Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. – 2006. – V. 49, No. 5. – P. 1668-1683.

- Kontogiorgis C.A., Hadjipavlou-Litina D.J. Synthesis and Antiinflammatory Activity of Coumarin Derivatives // Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. – 2005. – V. 48, No. 20. – P. 6400-6408.

- Shobha S.V., Candadai R.S., Ravindranath B. Inhibition of Soybean Lipoxygenase-1 by Anacardic Acids, Cardols, and Cardanols // Journal of Natural Products. – 1994. – V. 57, No. 12. – P. 1755-1757.

- Khan A.N., Perveen S., Malik A., Afza N., Iqbal L., Latif M., Saleem M. Conferin, potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory isoflavone from Caragana conferta Benth // J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. – 2010. – V. 25, No. 3. – P. 440-444.

- Jabbari A., Sadeghian H., Salimi A., Mousavian M., Seyedi S.M., Bakavoli M. 2-Prenylated m-Dimethoxybenzenes as Potent Inhibitors of 15-Lipoxygenase: Inhibitory Mechanism and SAR studies // Chemical Biology & Drug Design. – 2016. – V. 88. – P. 460-469.

- Rajić Z., Hadjipavlou-Litina D., Pontiki E., Balzarini J., Zorc B. The novel amidocarbamate derivatives of ketoprofen: synthesis and biological activity // Med. Chem. Res. – 2011. – V. 20, No. 2. – P. 210-219.

- Doulgkeris C.M., Siskou I.C., Xanthopoulou N., Lagouri V., Kravaritou C., Eleftheriou P., Kourounakis P.N., Rekka E.A. Compounds against inflammation and oxidative insult as potential agents for neurodegenerative disorders // Med. Chem. Res. – 2012. – V. 21, No. 9. – P. 2280-2291.

- Xternal Validation Plus. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/dtclabxvplus (accessed on June 25, 2022).

- Zakharov, A.V.; Peach, M.L.; Sitzmann, M.; Nicklaus, M.C. QSAR modeling of imbalanced high-throughput screening data in PubChem. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 705–712.

- Lagunin, A.; Zakharov, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. QSAR Modelling of Rat Acute Toxicity on the Basis of PASS Prediction. J. Mol. Informatics 2011, 30, 241-250. [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, A.V.; Lagunin, A.A.; Filimonov, D.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Quantitative structure—Activity relationships of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 inhibitors. J. Biomed. Chem. 2006, 52, 3–18.

- Filimonov, D.A.; Akimov, D.V.; Poroikov, V.V. The Method of Self-Consistent Regression for the Quantitative Analysis of Relationships Between Structure and Properties of Chemicals. Pharm. Chem. J. 2004, 38, 21–24.

- Ivanov, S.M.; Lagunin, A.A.; Filimonov, D.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Relationships between the structure and severe drug-induced liver injury for low, medium, and high doses of drugs. J. Chem. Res. Texicol. 2022, 35, 402–411.

- Lagunin, A.A.; Zakharov, A.V.; Filimonov, D.A.; Poroikov, V.V. A new approach to QSAR modelling of acute toxicity. J. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2007, 18, 285–298.

- Zakharov, A.V.; Varlamova, E.V.; Lagunin, A.A.; Dmitriev, A.V.; Muratov, E.N.; Fourches, D.; Kuz’min, V.E.; Poroikov, V.V.; Tropsha, A.; Nicklaus, M.C. QSAR Modeling and Prediction of Drug–Drug Interactions. J. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 545–556.

- MarvinSketch. Available online: https://chemaxon.com/download/marvin-suite (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- DiscoveryStudioVisualiser. Available online: https://www.3ds.com (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Roy, K.; Das, R.N.; Ambure, P.; Aher, R.B. Be aware of error measures. Further studies on validation of predictive QSAR models. J. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2016, 152, 18-33. [CrossRef]

- Strashilina I.V. Zameshchennye 2n-piran-2-ony v one-pot sinteze n, o -soderzhashchikh geterosistem: avtoref. dis. … kand. khim. nauk. 02.00.03 / Strashilina Irina Vladimirovna. – Saratov, 2018. – 23 s.

- Lyckander I. M., Malterud K. E. Lipophilic flavonoids from Orthosiphon spicatus as inhibitors of 15-lipoxygenase //Acta Pharmaceutica Nordica. – 1992. – Т. 4. – №. 3. – С. 159-166.

- Malterud K. E., Rydland K. M. Inhibitors of 15-lipoxygenase from orange peel //Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. – 2000. – Т. 48. – №. 11. – С. 5576-5580.

- Lyckander, I. M. Lipophilic flavonoids from Orthosiphon spicatus prevent oxidative inactivation of 15-lipoxygenase / I.M. Lyckander, K.E. Malterud // Prostaglandins, leukotrienes and essential fatty acids. – 1996. – V. 54. – №. 4. – P. 239-246.

- Bennamane, N. & Nedjar-Kolli, B & Geronikaki, Athina & Eleftheriou, Phaedra. (2011). N-Substituted [phenyl-pyrazolo]-oxazin-2-thiones as COX-LOX inhibitors: influence of the replacement of the oxo -group with thioxo- group on the COX inhibition activity of N-substituted pyrazolo-oxazin-2-ones.. ARKIVOC. [CrossRef]

- Poroikov, V.V. Computer-aided drug design: from discovery of novel pharmaceutical agents to systems pharmacology. J. Biochem. (Moscow), Supplement Series B: Biomedical Chemistry. 2020, 14, 216–227. [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Pogodin, P.V.; Savosina, P.I.; Tarasova, O.A.; Dmitriev, A.V.; Ivanov, S.M.; Biziukova, N.Y.; Druzhilovskiy, D.S.; Filimonov, D.A.; Poroikov V.V. CLC-Pred 2.0: A Freely Available Web Application for In Silico Prediction of Human Cell Line Cyto-toxicity and Molecular Mechanisms of Action for Druglike Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1689. [CrossRef]

- Muratov, E.N.; Bajorath, J.; Sheridan, R.P.; Tetko, I.V.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V.; Oprea, T.I.; Baskin, I.I.; Varnek, A.; Roitberg, A.; Isayev, O.; Curtarolo, S.; Fourches, D.; Cohen, Y.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Winkler, D.A.; Agrafiotis, D.; Cherkasov, A.; Tropsha, A. QSAR without borders. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3525–3564. [CrossRef]

- Tarasova, O.A.; Urusova, A.F.; Filimonov, D.A.; Nicklaus, M.C.; Zakharov, A.V.; Poroikov, V.V. QSAR Modeling Using Large-Scale Databases: Case Study for HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Mod. 2015, 55, 1388–1399. [CrossRef]

- Tarasova, O.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Ivanov, S.M.; Lagunin, A.A.; Poroikov, V.V.; Filimonov, D.A. Machine Learning Methods in Antiviral Drug Discovery. In Topics in Medicinal Chemistry; Tarasova, O.A., Rudik, A.V., Ivanov, S.M., Lagunin, A.A., Poroikov, V.V., Filimonov, D.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2021, 37, P. 245-279. [CrossRef]

- Kokurkina, G.V.; Dutov, M.D.; Shevelev, S.A.; Popkov, S.V.; Zakharov, A.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Synthesis, antifungal activity and QSAR study of 2-arylhydroxynitroindoles. Eur. J Med Chem. 2011, 46, 4374–4382. [CrossRef]

- Masand, V.H.; Mahajan, D.T.; Patil, K.N.; Dawale, N.E.; Hadda, T.B.; Alafeefy, A.A.; Chinchkhede, K.D. General Unrestricted Structure Activity Relationships based evaluation of quinoxaline derivatives as potential influenza NS1A protein inhibitors. Der Pharma Chemica, 2011, 3, 517–525.

- Masand, V.H.; Devidas, T.; Mahajan, D.T.; Patil, K.N.; Hadda, T.B.; Youssoufi, M.H.; Jawarkar, R.D.; Shibi, I.G. Optimization of Antimalarial Activity of Synthetic Prodiginines: QSAR, GUSAR, and CoMFA analyses. J. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2013, 81, 527–536. [CrossRef]

- Khairullina, V.R.; Gerchikov, A.Ya.; Zarudii, F.S. Analysis of the relationship “structure cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory activity” in the series of di-tret-butylphenol, oxazolone and thiazolone. J. Vestnik Bashk. Univ. 2014, 19, 417-422.

- Hildebrand, C.; Sandoli, D.; Focher, F.; Gambino, J.; Ciarrocchi, G.; Spadari, S.; Wright, G. Structure-activity relationships of N2-substituted guanines as inhibitors of HSV1 and HSV2 thymidine kinases. J. Med. Chem. 1990, 33, 203–206. [CrossRef]

- Manikowski, A.; Lossani, A.; Verri, A.; Gebhardt, B.-M.; Gambino, J.; Focher, F.; Spadari, S.; Wright, G.E. Inhibition of Herpes Simplex Virus Thymidine Kinases by 2-Phenylamino-6-oxopurines and Related Compounds: Structure-Activity Relationships and Antiherpetic Activity in Vivo. J Mol. Biochem. 2006, 48, 3919–3929. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.S.; Veselovsky, A.V.; Dubanov, A.V.; Skvortsov, V.S.; Archakov, A.I. The integral platform “From gene to drug prototype” in silico and in vitro. J. Ross. Khim. Zh. 2006, 1, 18–35.

| Training Set | Method | Model | N 1 | NPM | V | A 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR models based on the QNA descriptors | ||||||||||

| TrS1 | SCR | M1 | 84 | 20 | 0.825 | 0.758 | 10.429 | 0.485 | 17 | 0.067 |

| TrS2 | M10 | 70 | 20 | 0.804 | 0.714 | 7.608 | 0.531 | 15 | 0.090 | |

| TrS1 | RBF-SCR | M4 | 84 | 20 | 0.997 | 0.802 | 14.606 | 0.437 | 17 | 0.195 |

| TrS2 | M13 | 70 | 20 | 0.996 | 0.753 | 10.204 | 0.492 | 15 | 0.243 | |

| TrS1 | Both | M7 | 84 | 20 | 0.962 | 0.800 | 13.026 | 0.443 | 17 | 0.162 |

| TrS2 | M16 | 70 | 20 | 0.959 | 0.759 | 9.264 | 0.491 | 15 | 0.200 | |

| QSAR models based on the MNA descriptors | ||||||||||

| TrS1 | SCR | M2 | 84 | 20 | 0.798 | 0.725 | 8.749 | 0.517 | 16 | 0.073 |

| TrS2 | M11 | 70 | 20 | 0.825 | 0.741 | 6.444 | 0.512 | 17 | 0.084 | |

| TrS1 | RBF-SCR | M5 | 84 | 20 | 0.985 | 0.745 | 11.115 | 0.495 | 16 | 0.240 |

| TrS2 | M14 | 70 | 20 | 0.982 | 0.725 | 7.267 | 0.518 | 17 | 0.257 | |

| TrS1 | Both | M8 | 84 | 20 | 0.955 | 0.760 | 10.365 | 0.486 | 16 | 0.195 |

| TrS2 | M17 | 70 | 20 | 0.959 | 0.759 | 7.170 | 0.495 | 17 | 0.200 | |

| QSAR models based on both QNA and MNA descriptors | ||||||||||

| TrS1 | SCR | M3 | 84 | 320 | 0.842 | 0.777 | 8.747 | 0.480 | 17 | 0.065 |

| TrS2 | M12 | 70 | 320 | 0.842 | 0.766 | 7.067 | 0.499 | 16 | 0.076 | |

| TrS1 | RBF-SCR | M6 | 84 | 320 | 0.991 | 0.783 | 11.373 | 0.460 | 17 | 0.208 |

| TrS2 | M15 | 70 | 320 | 0.99 | 0.769 | 9.189 | 0.480 | 16 | 0.221 | |

| TrS1 | Both | M9 | 84 | 320 | 0.965 | 0.798 | 10.443 | 0.454 | 17 | 0.167 |

| TrS2 | M18 | 70 | 320 | 0.966 | 0.787 | 8.401 | 0.474 | 16 | 0.179 | |

| Criteria | Code of the Training Set | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrS1 | TrS2 | |||||||

| 100% data of TrS1 | 95% data of TrS1 | 100% data of TrS2 | 95% data of TrS2 | |||||

| max | min | max | min | max | min | max | min | |

| R2 | М4 | М2 | М4 | М2 | М13, М15 | М10 | М15 | М10 |

| 0.990 | 0.932 | 0.993 | 0.942 | 0.986 | 0.923 | 0.991 | 0.934 | |

| R20 | М4 | М2 | М4 | М2 | М13 | М10 | М15 | М10 |

| 0.989 | 0.920 | 0.992 | 0.933 | 0.985 | 0.914 | 0.991 | 0.934 | |

| R2’0 | М4 | М2 | М4 | М2 | М13 | М10 | М13 | М10 |

| 0.989 | 0.891 | 0.963 | 0.786 | 0.984 | 0.886 | 0.9545 | 0.781 | |

| М4 | М2 | М4 | М2 | М13 | М10 | М13 | М10 | |

| 0.964 | 0.811 | 0.971 | 0.837 | 0.959 | 0.813 | 0.969 | 0.832 | |

| ΔR2m | М2 | М4 | М2 | М4 | М10 | М13 | М10 | М15 |

| 0.067 | 0.009 | 0.057 | 0.006 | 0.071 | 0.012 | 0.062 | 0.008 | |

| CCC | М4 | М2 | М4 | М2 | М13, М15 | М10 | М13, М15 | М10 |

| 0.993 | 0.942 | 0.996 | 0.962 | 0.992 | 0.951 | 0.995 | 0.959 | |

| RMSE | М2 | М4 | М2 | М4 | М10 | М13 | М10 | М14, М15 |

| 0.278 | 0.101 | 0.244 | 0.088 | 0.290 | 0.120 | 0.260 | 0.101 | |

| MAE | М2 | М4 | М2 | М4 | М10 | М13 | М10 | М14 |

| 0.225 | 0.079 | 0.201 | 0.070 | 0.240 | 0.092 | 0.218 | 0.079 | |

| SD | М2 | М4 | М2 | М4 | М11 | М13 | М11 | М15 |

| 0.165 | 0.063 | 0.140 | 0.053 | 0.168 | 0.078 | 0.147 | 0.060 | |

| MAE + 3·SD | М2 | М4 | М2 | М4 | М10 | М13 | М10 | М15 |

| 0.719 | 0.268 | 0.620 | 0.230 | 0.733 | 0.326 | 0.644 | 0.261 | |

| Criteria | Code of the Test Set | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS1 | TS2 | |||||||

| 100% data of TS1 | 95% data of TS1 | 100% data of TS2 | 95% data of TS2 | |||||

| max | min | max | min | max | min | max | min | |

| R2 | М14 | М9, М12 | М10 | М3 | М13 | М11 | М13 | М11 |

| 0.832 | 0.776 | 0.870 | 0.798 | 0.849 | 0.723 | 0.880 | 0.730 | |

| R20 | М14 | М12 | М10 | М3 | М13 | М11 | М13 | М11 |

| 0.832 | 0.775 | 0.870 | 0.790 | 0.848 | 0.721 | 0.868 | 0.722 | |

| R2’0 | М14 | М9 | М1 | М12 | М13 | М11 | М16 | М11 |

| 0.806 | 0.711 | 0.820 | 0.627 | 0.809 | 0.580 | 0.700 | 0.583 | |

| М14 | М12 | М10 | М3, М12 | М13 | М11 | М13 | М11 | |

| 0.872 | 0.832 | 0.903 | 0.866 | 0.894 | 0.805 | 0.914 | 0.843 | |

| R2m | М14 | М12 | М10 | М3 | М13 | М11 | М13 | М11 |

| 0.828 | 0.774 | 0.869 | 0.783 | 0.845 | 0.716 | 0.868 | 0.673 | |

| CCC | М14 | М9 | М10 | М3 | М13 | М11 | М13 | М11 |

| 0.761 | 0.700 | 0.815 | 0.732 | 0.748 | 0.574 | 0.742 | 0.633 | |

| RMSEP | М1 | М18 | М12 | М1 | М11 | М13 | М11 | М13 |

| 0.147 | 0.040 | 0.123 | 0.016 | 0.204 | 0.118 | 0.186 | 0.104 | |

| MAE | М14 | М9 | М10 | М3 | М13 | М11 | М13 | М11 |

| 0.909 | 0.873 | 0.928 | 0.892 | 0.915 | 0.831 | 0.921 | 0.836 | |

| SD | М12 | М14 | М12 | М13 | М11 | М13 | М11 | М13 |

| 0.441 | 0.384 | 0.406 | 0.338 | 0.497 | 0.367 | 0.433 | 0.342 | |

| MAE + 3·SD | М3 | М13 | М12 | М16 | М11 | М13 | М11 | М13 |

| 0.377 | 0.326 | 0.347 | 0.287 | 0.411 | 0.314 | 0.365 | 0.291 | |

| Сompound | Concentration, μM | Enzyme activity inhibition, % | IC50, µmol/l |

| 1 | 60 | 27.62 | 72.5 |

| 70 | 45.25 | ||

| 80 | 63.30 | ||

| 90 | 81.12 | ||

| 2 | 30 | 12.99 | 48.2 |

| 40 | 33.61 | ||

| 50 | 53.12 | ||

| 60 | 74.14 | ||

| 3 | 20 | 40.679 | 30.4 |

| 30 | 49.593 | ||

| 40 | 58.907 | ||

| 50 | 66.821 | ||

| 4 | 60 | 29.47 | 70.8 |

| 70 | 47.37 | ||

| 80 | 68.27 | ||

| 90 | 88.18 | ||

| 5 | 50 | 21.78 | 69.6 |

| 60 | 37.64 | ||

| 70 | 51.49 | ||

| 80 | 63.36 | ||

| 6 | 10 | 16.2134 | 24.9 |

| 20 | 35.8994 | ||

| 30 | 65.0854 | ||

| 40 | 83.2714 | ||

| 7 | 40 | 25.9180 | 45.7 |

| 45 | 46.8465 | ||

| 50 | 68.7750 | ||

| 55 | 89.7035 | ||

| 8 | 40 | 13.886 | 47.4 |

| 45 | 36.793 | ||

| 50 | 63.700 | ||

| 55 | 86.607 |

| Сompound | pIC50 exp 1 | SCR | RBF-SCR | Both | ||||||

| Model | pIC50 pred | pIC50 2 | Model | pIC50 pred | pIC50 | Model | pIC50 pred | pIC50 | ||

| 1 | 4.140 | M3 | 4.323 | 0.183 | M6 | 4.313 | 0.173 | M9 | 4.267 | 0.127 |

| M12 | 4.301 | 0.161 | M15 | 4.301 | 0.161 | M18 | 4.249 | 0.109 | ||

| 2 | 4.317 | M3 | 4.033 | 0.284 | M6 | 4.063 | 0.254 | M9 | 3.934 | 0.383 |

| M12 | 4.145 | 0.172 | M15 | 4.166 | 0.151 | M18 | 4.054 | 0.263 | ||

| 3 | 4.517 | M3 | 4.086 | 0.431 | M6 | 4.119 | 0.398 | M9 | 4.081 | 0.436 |

| M12 | 4.054 | 0.463 | M15 | 4.112 | 0.405 | M18 | 4.052 | 0.465 | ||

| 4 | 4.150 | M3 | 4.874 | 0.724 | M6 | 4.836 | 0.686 | M9 | 4.823 | 0.673 |

| M12 | 4.840 | 0.690 | M15 | 4.808 | 0.658 | M18 | 4.813 | 0.663 | ||

| 5 | 4.157 | M3 | 4.426 | 0.269 | M6 | 4.389 | 0.232 | M9 | 4.388 | 0.231 |

| M12 | 4.518 | 0.361 | M15 | 4.479 | 0.322 | M18 | 4.493 | 0.336 | ||

| 6 | 4.604 | M3 | 4.403 | 0.201 | M6 | 4.373 | 0.231 | M9 | 4.385 | 0.219 |

| M12 | 4.427 | 0.177 | M15 | 4.398 | 0.206 | M18 | 4.429 | 0.175 | ||

| 7 | 4.340 | M3 | 4.532 | 0.192 | M6 | 4.450 | 0.11 | M9 | 4.501 | 0.161 |

| M12 | 4.635 | 0.295 | M15 | 4.552 | 0.212 | M18 | 4.613 | 0.273 | ||

| 8 | 4.324 | M3 | 4.318 | 0.006 | M6 | 4.290 | 0.034 | M9 | 4.270 | 0.054 |

| M12 | 4.396 | 0.072 | M15 | 4.364 | 0.040 | M18 | 4.362 | 0.038 | ||

| Model | RMSEP | 2·RMSEP | ||||||

| TS1 | TS2 | TS1 | TS2 | |||||

| 100% data | 95% data | 100% data | 95% data | 100% data | 95% data | 100% data | 95% data | |

| M3 | 0.437 | 0.389 | ‒ | ‒ | 0.874 | 0.778 | ‒ | ‒ |

| M6 | 0.431 | 0.326 | ‒ | ‒ | 0.862 | 0.652 | ‒ | ‒ |

| M9 | 0.440 | 0.375 | ‒ | ‒ | 0.880 | 0.750 | ‒ | ‒ |

| M12 | 0.441 | 0.406 | 0.458 | 0.390 | 0.882 | 0.812 | 0.916 | 0.780 |

| M15 | 0.425 | 0.365 | 0.420 | 0.362 | 0.850 | 0.730 | 0.840 | 0.724 |

| M18 | 0.432 | 0.381 | 0.433 | 0.373 | 0.864 | 0.762 | 0.866 | 0.746 |

| Designation of TrSi | Code of the Training Set | |

| TrS1 | TrS2 | |

| N | 84 | 70 |

| 5.308 | ||

| ∆pIC50 | 3.873 | |

| Thresholds used to evaluate model's forecast | ||

| 0.10 × ∆pIC50 | 0.387 | |

| 0.15 × ∆pIC50 | 0.581 | |

| 0.20 × ∆pIC50 | 0.775 | |

| 0.25 × ∆pIC50 | 0.968 | |

| Designation of TSi | Code of the Test Set | |

| TS1 | TS2 | |

| N | 84 | 70 |

| 4.765 | 4.678 | |

| ∆pIC50 | 3.196 | 3.275 |

| Distribution of the observed response values of test sets TSi around the test mean | ||

| ± 0.5, % | 37.500 | 50.000 |

| ± 1.0, % | 75.000 | 78.571 |

| ± 1.5, % | 87.500 | 85.714 |

| ± 2.0, % | 93.750 | 92.857 |

| Distribution of the observed response values of test sets TSi around the training mean | ||

| ± 0.5, % | 12.500 | 14.286 |

| ± 1.0, % | 50.000 | 42.857 |

| ± 1.5, % | 87.500 | 85.714 |

| ± 2.0, % | 100.000 | 100.000 |

| Model quality | High descriptive and predictive ability | Moderate descriptive and predictive ability | Low descriptive and predictive ability |

| Criteria based on R2 | R2 → R20 > 0.8 | R2 → R20 ≤ 0.8 | R2 → R20 ≤ 0.6 |

| > 0.8 | ≤ 0.6 | > 0.5 | |

| ≤ 0.15 | < 0.2 | < 0.2 | |

| CCC > 0.8 | CCC ≤ 0.8 | CCC → 0.7 | |

| Q2LMO > 0.70 | Q2LMO ≤ 0.70 | Q2LMO< 0.60 | |

| Q2F1 > 0.70 | Q2F1 ≤ 0.70 | Q2F1 < 0.60 | |

| Q2F2 > 0.70 | Q2F2 ≤ 0.70 | Q2F2 < 0.60 | |

| А* < 0.3 | А* ≤ 0.3 | А* > 0.3 | |

| MAE | MAE ≤ 0.387 | MAE = (0.387;0.581] | MAE > 0.581 |

| Criteria B** | B ≤ 0.775 | B = (0.775; 0.968] | B > 0.968 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).