1. Introduction

Copper is an essential micronutrient for plants, animals and microorganisms and plays an important role in various physiological processes [

1]. However, it is also a metal that is frequently emitted into the natural environment and behaves as a toxic agent when its concentration exceeds certain thresholds [

2,

3]. Although there are numerous natural sources of copper emissions: forest fires, dust storms, vegetation decomposition and marine aerosols, the biggest problem is represented by anthropogenic sources: mining and metallurgical industries, agrochemical use and wood production [

4,

5]. In the air, copper adheres to particles and can be transported quite far from its source. In water, copper is fixed to the soil, from where it is transferred to plants and begins its journey through the food chain, or it dissolves and remains available to affect microorganisms, crustaceans and fish, promoting bioaccumulation phenomena [

3].

Of particular concern is the contamination of soils with copper from the use of agrochemicals, as these are a constant source of biomagnification of the metal. Copper is one of the seven micronutrients essential for plant growth, and in agricultural soils its normal concentration varies from 5 to 30 mg/kg, but higher levels can cause toxic effects [

6]. Ballabio

et al. [

6] studied the concentration of Cu in different types of soil cover and showed that vineyards, olive groves and fruit trees had the highest average concentration of Cu (49.26, 33.49 and 37.32 mg/kg) and also the highest percentage of samples above the maximum threshold. In natural soils around the world, average Cu concentrations typically range from 2 to 109 mg/kg. Mining is another activity that can heavily contaminate soils, with concentrations exceeding 1000 mg/kg [

7,

8].

On the other hand, the main sources of groundwater contamination are natural/geogenic, waste in landfills and poor sanitary practices, together with the use of agrochemicals. [

9]. The presence of copper-contaminated water presents a significant risk to human well-being, in particular to the general balance of living organisms and to aquatic ecosystems [

5].

Due to its bioaccumulative nature, copper can have adverse effects on human and animal health, affecting the intestines, liver and stomach. At higher concentrations, it can cause skin cancer, skin lesions, angiosarcoma, peripheral neuropathy and vascular disease [

10]. It can also cause neurotoxicity and cytotoxicity [

11], even leading to cell death through a phenomenon known as cuprosis [

12]. On the other hand, excess Cu in soil also negatively affects vegetation, significantly reducing seed germination in many species and negatively affecting the growth and development of many others.

There are many techniques to remove or reduce the amount of copper in wastewater and soil, including ion exchange, chemical precipitation, adsorption and filtration. These types of technologies are effective at high metal concentrations, but they use significant amounts of chemicals, are expensive and produce sludge that then needs to be treated. For this reason, several studies have been carried out in recent decades on the biosorption of heavy metals in general and copper in particular [

13]. Biosorption is a very effective biological technique at low concentrations (<100 mg/L), green, economically viable, ecological and sustainable, which is presented as a promising tool to contribute to the environmental sustainability of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Biosorption involves several mechanisms of interaction with metals, some of which have the capacity to reduce metal ions, promoting the synthesis of nanoparticles that can be recovered and used in other areas of biotechnology. This aspect also contributes to the circular economy and ultimately to environmental sustainability. CuO nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) have shown remarkable potential in the biomedical field and their antimicrobial, antiviral, anticancer and antidiabetic capacity has been demonstrated, and they also have potential as drug delivery vectors [

14]. In terms of their biocidal activity, their potential derives from their small size and high specific surface area, which facilitates interactions with microbial cell membranes and access to vital organelles in the cytoplasm [

15].

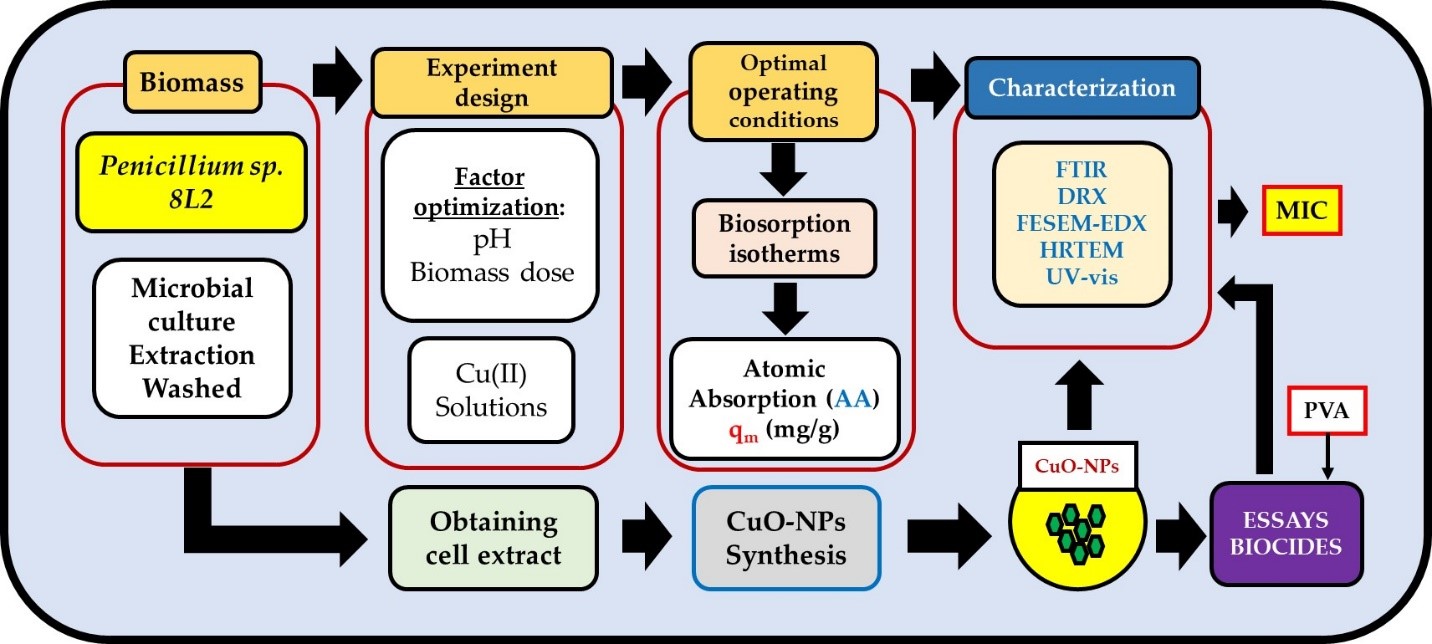

The aim of this work was to study the biotechnological potential of

Penicillium sp. 8L2, a ubiquitous fungus previously isolated from urban wastewater [

16]. Two different facets were studied: the biosorption of Cu(II) and the synthesis of CuO-NPs from its cellular extract. In addition, a preliminary study on the biocidal capacity of the NPs was carried out. Finally, a first approximation to the use of adjuvants and their influence on the biocidal activity of CuO-NPs was investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Biomass for Biosorption Tests and Nanoparticle Synthesis

For this research, a filamentous fungus was selected that had been isolated from wastewater from the province of Jaén [

16] and that had shown good behavior for Ag(I) biosorption in a previous work [

17].

Penicillium sp. 8L2 was preserved in glycerol stock at -80°C and grown in YPG (yeast, peptone, glucose) liquid medium for 24 h at 27 °C and 150 rpm. From the activated pre-inoculum, six 250 mL flasks were inoculated with 200 mL of YPG each and kept under the same conditions for 4 days until mycelial spheres of suitable size were obtained in sufficient quantity to carry out the biosorption tests. The biomass was repeatedly washed with 0.1 M NaNO

3 electrolyte solution until the biomass was free of nutrient medium. From this washed biomass, the dry weight was calculated to determine the amount of wet biomass required to obtain the respective biomass concentrations to be used in the biosorption tests. On the other hand, to obtain the fungal cell extract to be used in the nanoparticle synthesis tests, the protocol used in [

17] was followed.

2.2. Biosorption Tests

For biosorption assays, Cu(II) solutions were prepared in distilled water and pH adjusted using 0.1 M HNO

3 and 0.1 N NaOH solutions. All assays were performed at 27 °C and 200 rpm in an SI-600R Orbital (Lab Companion Warpsgrove Ln, Chalgrove, Ox-fordshire, UK). 100 mL flasks containing 50 mL of metal solution were used, to which the required amount of biomass was added. Response Surface Methodology (SRM) was used to define the optimum operating conditions (see section 3.3), which resulted in various test conditions listed in

Table 1. In all cases, to ensure that the biosorption process was complete, a contact time of 4 days was chosen, after which the samples were collected, filtered with 0.22 µm PES filters and analyzed by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) in a Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 800 instrument (Midland, ON, Canada). To obtain the biosorption capacity (q mg metal/g dry biomass), the results obtained were applied in Equation 1:

where C

i is the initial concentration of Cu(II), C

f is the final concentration of Cu(II) after the test, V is the volume used and m is the dry mass of the biomass expressed in grams. The experimental design tests were carried out with a metal concentration of 50 mg/L and allowed the optimal operating conditions of the biosorption process to be established. Tests were then carried out to obtain the isotherms of the process by varying the metal concentration between 10 and 200 mg/L. All experiments were carried out in duplicate.

2.3. Experimental Design

In order to carry out the Cu(II) biosorption tests with

Penicillium sp. 8L2 and to determine their optimum conditions, a two-factor rotatable central composite (RCC) design with five levels and five centers was used. The factors studied were pH (between 3 and 5.5) and biomass concentration (between 0.2 and 0.8 g/L), preceded by the rest of the operational variables as indicated in section 2.2.

Table 1 shows the experimental design in real and coded factors, sorting the trials in order of execution, randomized to eliminate the error associated with the repetition of successive factors. The software used was Design Expert 8.0.7.1 from Stat-Ease, Inc., Minneapolis (USA).

The experimental results were fitted, using Response Surface Methodology (RSM), to the following quadratic Equation (2):

where y is the response, A and B are the coded factors and ε is the standard deviation of the model in predicting the response. α are the coefficients of the different terms of the equation, so the subscript 0 indicates the value of the response at the center of the experimental design, 1 and 2 correspond to the linear terms of the factors or first level terms, 11 and 22 are the quadratic terms and 12 corresponds to the interaction term between factors. Terms with two numbers in the subscript are considered to be second level or of lesser importance to the response surface. The model obtained should be hierarchical, so that whenever a second level term is statistically significant, the first level term of that factor should be present in the equation, even if it is not statistically significant (p_value > 0.05).

The linear terms in Equation 2 show the linear variation of the response as the factors are varied, while the quadratic terms give a curvature to the surface and the interaction term twists it to show the different influence of one factor on the response depending on the value of the other factor.

2.4. Biosorption Mechanisms: FE-SEM-EDX and FT-IR Analysis

In order to study the mechanisms involved in the biosorption process, biomass samples were taken before and after the biosorption stage during the equilibrium tests. The biomass blank was obtained directly from the biomass washed just before the start of the tests. The different experimental samples were taken at the end of each test and washed repeatedly as described in section 2.1 until biomass free of metal dissolution was obtained. The ultimate goal was to ensure that the biomass was free of residual copper and that any copper in the samples was derived from biosorption mechanisms typical of fungal biomass. For Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis, samples were dried in an oven at 60 °C for 48 h until confirmed to be moisture free. The samples were then subjected to intensive grinding in a ceramic mortar and stored in a desiccator until analysis. A VERTEX 70 (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) instrument with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) detector in the range of 400 to 4000 cm-1 was used. The resulting spectra were analyzed using OPUS 7.0 software and allowed the identification of the characteristic bands of the fungal biomass and how these were affected after the Cu(II) retention stage.

In addition, using the same sampling protocol, biomass pellets were obtained for analysis by field emission scanning electron microscopy coupled with an X-ray dispersion detector (FESEM-EDX). A MERLIN instrument from Carl Zeiss (Göttingen, Germany) was used. Samples were fixed with a 2. 5% dilution of glutaraldehyde in PBS buffer and kept at 5 °C for 1 h, then the samples were washed with PBS buffer until the fixative solution was removed, then the biomass was dehydrated by exposing it to increasing concentrations of acetone (50, 70, 90 and 100%), resuspending it and keeping it for 10 min at each concentration until reaching the highest concentration, where it was kept for 1 h, then the samples were subjected to the critical point technique to dry them completely by including liquefied CO2 at high pressure. Finally, the samples were metallized with carbon to avoid signal interference during elemental mapping.

2.5. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Nanoparticles

The process for obtaining CuO nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) was based on contacting the cell extract produced by

Penicillium sp. 8L2 (see section 2.1) with a Cu(NO

3)

2-3H

2O solution, as described by Muñoz

et al. [

18]. Once the CuO-NPs were obtained, they were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD). For this purpose, the nanoparticles were analyzed in a Malvern Panalytical Empyrean instrument (Malvern, WR14 1XZ, UK) under the conditions described in Muñoz

et al. [

19]. The theoretical crystal size was also calculated using the Debye-Scherrer equation (Equation 3):

where d is the mean crystal diameter, k is the value of the Scherrer constant which has a value of 0.9, λ is the wavelength of the incident beam (1.5406 Å), β is the width at half height of the most intense peak in the spectrum and θ is the Braag diffraction angle. The measurement conditions are described in Muñoz

et al. [

20].

In addition, the CuO-NPs were analyzed by FESEM and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to study their morphology and to determine the actual mean size based on the histogram and frequency polygon. A JEOL JEM-1010 transmission electron microscope (11 Dearborn Road, Peabody, MA, USA) was used and images were processed using ImageJ software (version 1.53e).

2.6. Determination of the Biocidal Effect

The study of the biocidal capacity of CuO-NPs synthesized with the cell extract of

Penicillium sp. 8L2 was based on the determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The microorganisms used in the assays were the yeast

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa 1S1, isolated from wastewater in a previous work [

16], two Gram-positive bacteria:

Bacillus cereus CECT 131 and

Staphylococcus epidermidis CECT 4183, and two Gram-negative bacteria:

Escherichia coli CECT 101 and

Pseudomonas fluorescens CECT 378. Two types of assays were performed: the first was carried out on solid Müller-Hinton agar medium contaminated with increasing concentrations of nanoparticles ranging from 3.9 to 2000 µg/mL, obtained by serial dilution from a colloidal suspension in sterile ultrapure water of 4000 µg/mL. From a liquid pre-inoculum with 24 h growth (at 27 °C and 150 rpm), 20 µL were inoculated in triplicate into the different Petri dishes, keeping two of them containing the uncontaminated medium to act as positive control (inoculated) and negative control (uninoculated). The plates were kept in an oven at 27 °C for 24 hours before microbial growth was analyzed. The second method incorporated a 10% dispersing reagent (polyvinyl alcohol, PVA) into the nanoparticle suspensions and was performed in 96-well microplates. This method was based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) protocol M07-A9 with some modifications. The protocol used the same inoculum and culture medium as the previous protocol, described in detail in a previous paper [

18], and established a concentration range between 7.8 and 4000 µg/ml. Assays were performed in triplicate for 24 h at 27 °C, with absorbance readings at 630 nm every 30 min in two different instruments that gave comparable values: BioTek Synergy HT (Santa Clara, USA) and TECAN Infinite M Plex (Männedorf, Switzerland).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biosorption of Cu(II): Optimal Operating Conditions

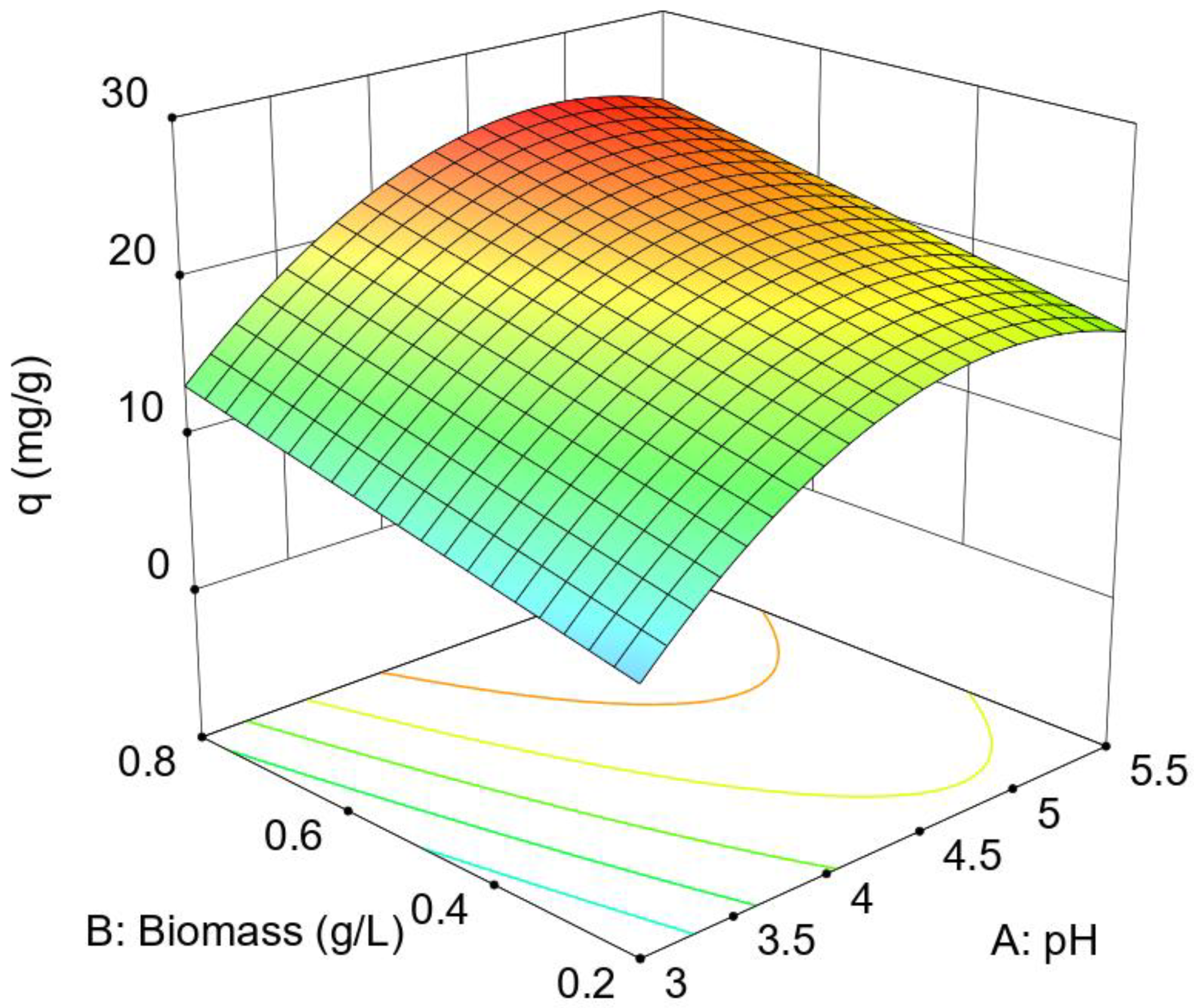

Table 1 shows the results obtained for Cu(II) biosorption by Penicillium sp. 8L2. These data have been fitted to Equation 2 to obtain the model of Equation 4, in coded factors.

Hierarchical model with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.997 and a coefficient of variation of 2.94%. The model and the terms shown in Equation 4 are statistically significant (p_value < 0.0001) and there is no lack of fit (p_value > 0.29). Missing terms are not statistically significant (p_value > 0.1).

According to Equation 4, the influence of pH is greater than that of biomass concentration (the coefficient is higher), there is no interaction between the factors and it only shows a curvature for the pH factor. As the sign of the quadratic term is negative, the response curves downwards at the extremes of the experimental interval, sometimes showing a maximum in intermediate zones. The influence of the quadratic term on the response surface is greater the larger it is in absolute value compared to the linear term. Thus, 5.55 versus 5.34 allows the surface to curve significantly as the factor approaches the extremes of the interval. In the case of Equation 4, the model shows a maximum biosorption capacity at pH 4.85 (+0.48 coded). For the biomass concentration, since the coefficient of the linear term of factor B of Equation 4 is positive and there is no other term that includes this factor, the maximum corresponds to the upper value of the experimental interval 0.8 g/L (+1 coded). For these optimum factors, the maximum biosorption of Cu(II) by Penicillium sp. 8L2 is 25.46 mg/g.

Figure 1 shows the response surface model represented by Equation 4, where all of the above can be verified.

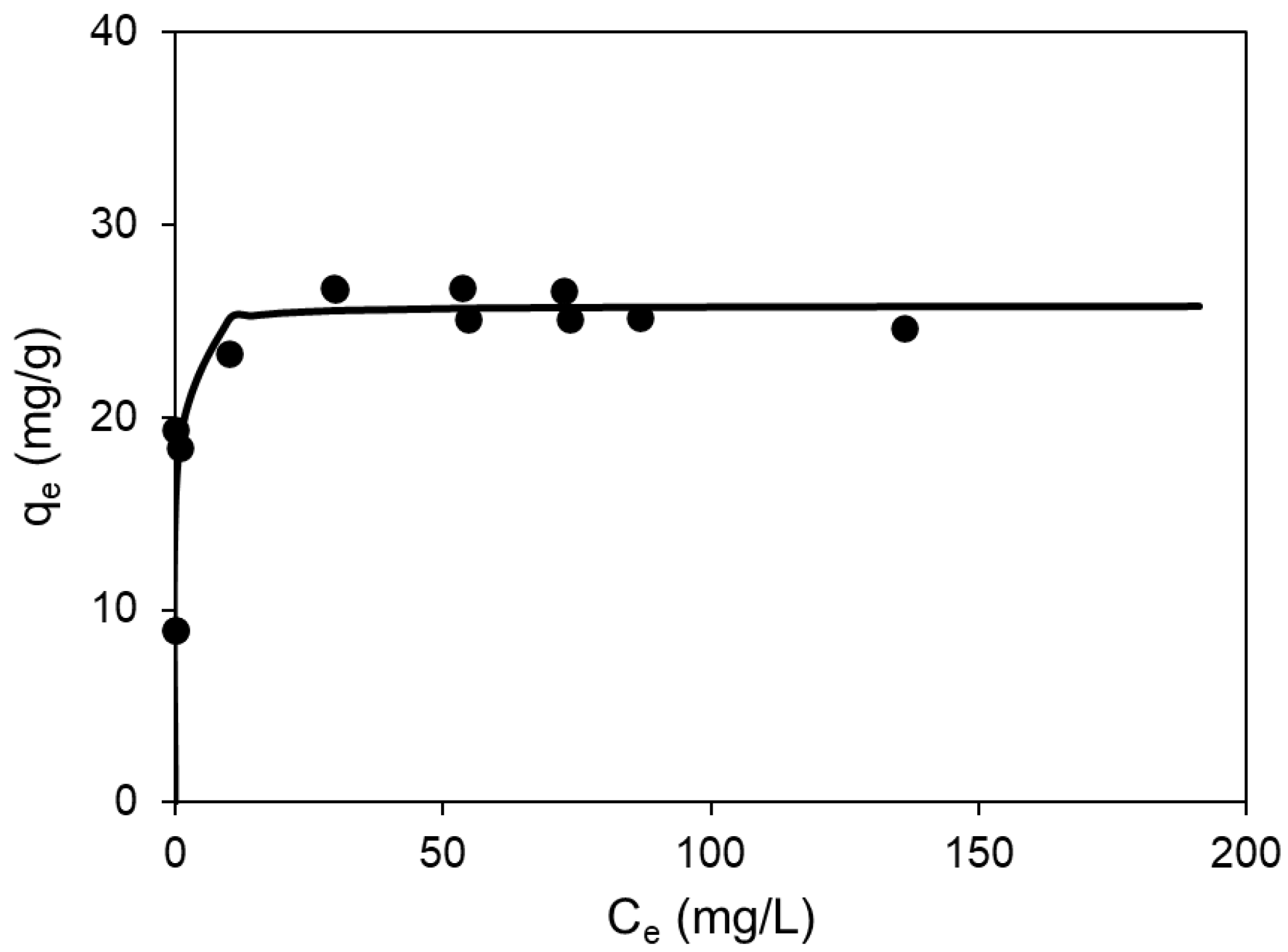

3.2. Biosorption Isotherms

Table 2 shows the experimental results obtained in the equilibrium tests described in section 2.2. In this case, the pH and biomass concentration factors, 4.85 and 0.8 g/L respectively, were previously obtained in the experimental design (section 3.1).

Non-linear fitting using Statgraphics Centurion v.16.2.04 determined the Langmuir [

21] and Freundlich [

22] models that fit the data in

Table 3. Two-parameter models that fit the experimental results fairly well (

Table 3) with coefficients of variation less than 5% (Langmuir model) or close to 5% (Freundlich model).

As can be seen in

Table 3, the Langmuir model is the one that best fits the experimental results, since it has the best coefficient of determination and the lowest relative error. Statistically, the relatively low R

2 values are justified because the values of the dependent variable (q

e) vary very little with high variations of the independent variable (C

e), mostly an almost horizontal line (

Figure 2).

Considering the Langmuir model,

Table 3 shows a qmax value of 25.79 mg/g, which is very similar to the optimum determined in the experimental design in

Table 1, Equation 4, indicating the precision with which the biosorption optimum has been determined. On the other hand, such a high value of b indicates that the biosorption equilibrium is reached very quickly, i.e. the process is very fast. This is also reflected in the very high value of the n parameter of the Freundlich model.

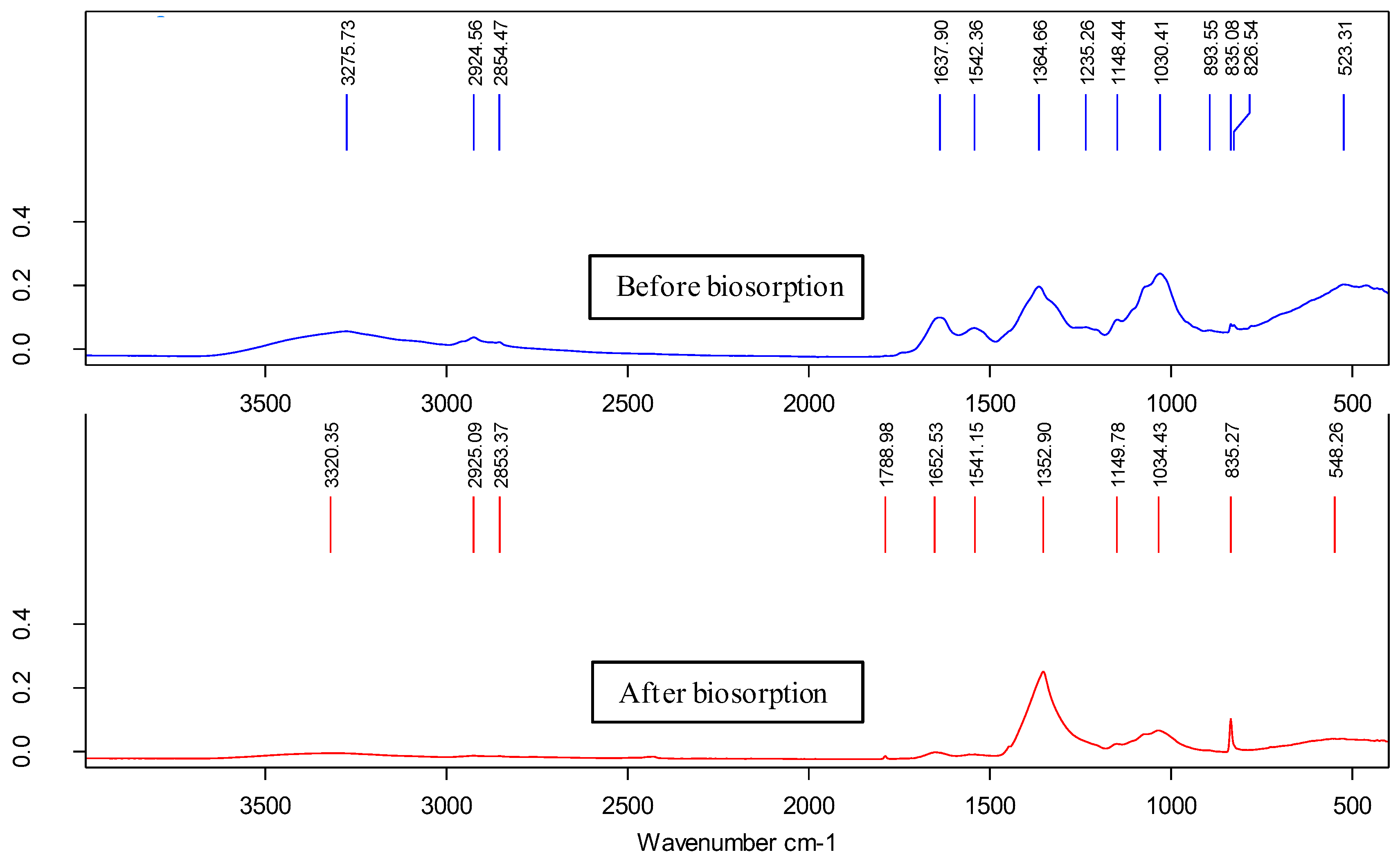

3.3. Biosorption Mechanisms

Figure 3 shows the spectra obtained by ATR before and after the biosorption stage and reveals important intensity changes and shifts in some characteristic bands. The bands at 3276 cm

-1 (which changed to 3320 cm

-1) and 1365 cm

-1 (which changed to 1353 cm

-1) involved vibrations of O-H and C-O bonds in the first case and vibrations due to bending of C-H bonds in the second case [

23,

24,

25]. All this indicated the involvement of hydroxyl, carbonyl and methyl groups in the Cu(II) biosorption process. On the other hand, the band located at 1638 cm

-1 underwent a significant shift to 1653 cm

-1, revealing the involvement of C=O bond stretching vibrations associated with amide I, confirming the participation of carbonyl groups [

26,

27]. In parallel, the band at 1235 cm

-1 associated with asymmetric C-O-C bond stretching disappeared after the biosorption step, again confirming the involvement of carbonyl groups. Finally, there was a strong change in the bands located in the region between 800 and 900 cm

-1, which could be related to an out-of-plane C-H aromatic deformation or even to C-N bond stretching vibrations [

28]. In conclusion, FT-IR analysis indicated that hydroxyl, carbonyl, methyl and methylene functional groups were mainly involved in the Cu(II) biosorption process.

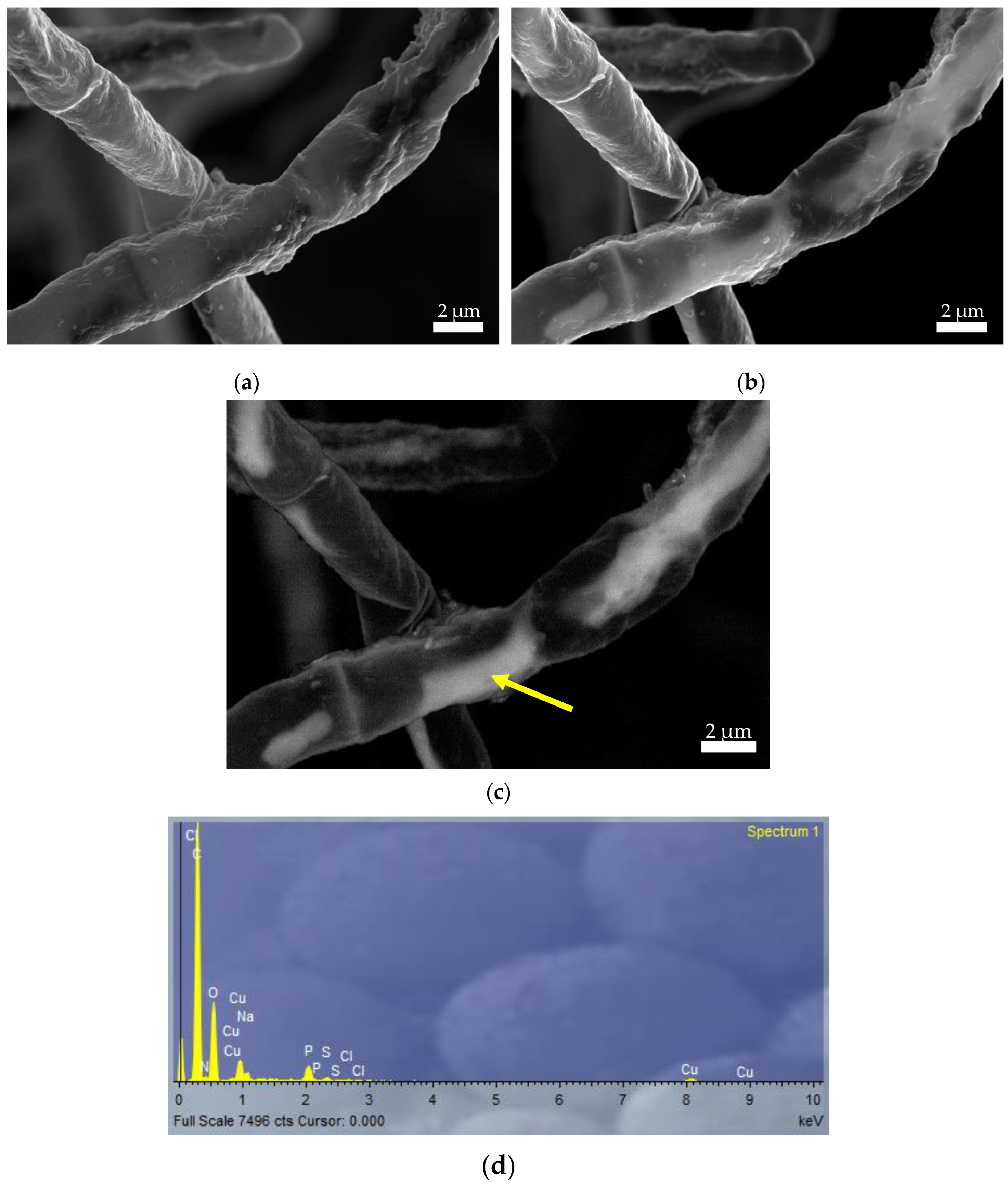

Figure 4 shows three SEM images obtained after the Cu(II) biosorption step by Penicillium sp. 8L2. The image in

Figure 4-a was taken with the secondary electron detector (SE2) and allowed the topography of the sample surface to be examined at low magnifications with a large depth of field. In this case, small surface aggregates compatible with copper precipitation were observed. To further investigate Cu(II) biosorption, the same sample area was observed by changing the detector and in

Figure 4-b the same area can be observed with the secondary electron detector in the lens (InLens), which collects low energy electrons and provides high resolution images, but does not allow changes in the chemical nature of the sample to be clearly distinguished. Nevertheless, whitish areas were observed which appeared to indicate the presence of copper in the fungal hyphae. Finally,

Figure 4-c, taken with the backscattered electron detector (AsB), which has the peculiarity of being sensitive to the variation in atomic number of the elements present in the sample, allowed the presence of copper inside the hyphae to be clearly identified. These results were confirmed by the EDX spectrum taken in the same area (

Figure 4-d).

3.4. Characterization of Nanoparticles

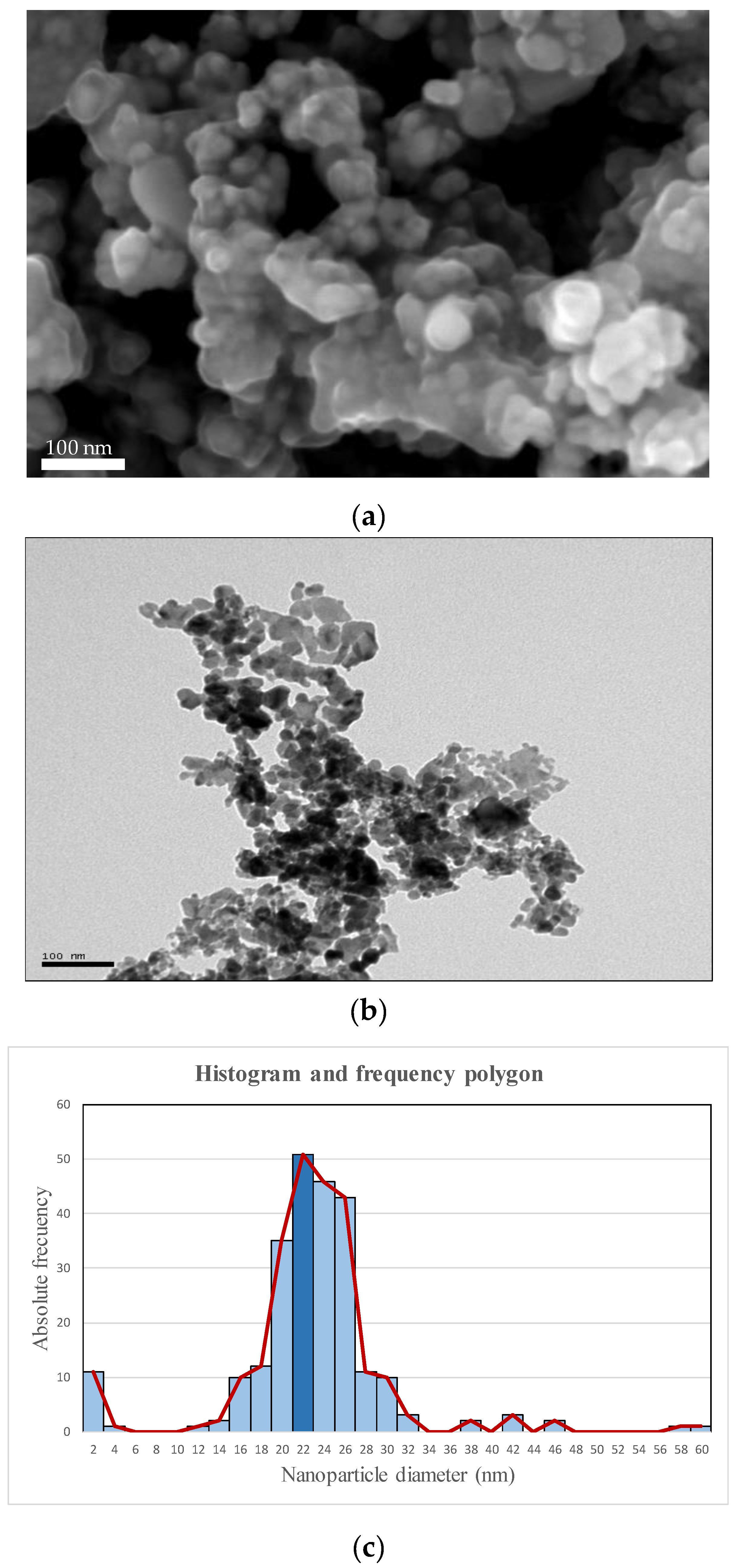

In order to verify the effectiveness of the method for the synthesis of CuO-NPs from the fungus Penicillium sp. 8L2, XRD and TEM analyses were carried out.

Figure 5 shows the X-ray diffraction spectrum and it can be observed that the two protocols used allowed obtaining CuO nanoparticles, although the protocol that included the carbonisation step at 500 °C (protocol 2) allowed obtaining nanoparticles of greater purity and crystallinity, as indicated by the presence of narrow and well-defined peaks [

29]. For protocol 2, the spectral bands fit perfectly with those expected for CuO-NPs and their 2Theta angle positions were at 35.52°, 35.54°, 38.76°, 49.79°, 53.51°, 58.32°, 61.58°, 66.21°, 68.09°, 72.42° and 75.14° [

30,

31]. For protocol nº1, it can be observed that the peaks are also present, but they have a lower definition and intensity, and they also appear mixed with other peaks that could be due to salts from the synthesis process. The presence of CuO-NPs in a protocol that did not include carbonisation of the samples is interesting and its biocidal potential will be studied in future work, but in this work it was decided to analyse the biocidal activity of the nanoparticles obtained by protocol 2, which had a higher purity.

When the most intense peak of the spectrum was analysed using the Debye-Scherrer equation, a theoretical crystal size of 17 nm was obtained. This size was similar to that observed in the TEM and SEM images of

Figure 6 (a and b respectively), which were obtained directly on the nanoparticles and had an average size of 22 nm.

Figure 6-c shows the histogram and frequency polygon obtained from the image in Figure SEM/TEM-a and it can be observed that the nanoparticles had sizes between 12 and 32 nm. This FESEM image showed a strong presence of aggregates, which made their analysis with the ImageJ software difficult, but allowed to obtain a very approximate idea of the average size of the nanoparticles, which was at a value similar to that obtained by other authors [

15]. In general, both the small size of the nanoparticles and their spherical morphology allowed us to predict that the behaviour of CuO-NPs as biocidal agents could be good [

14].

3.5. Biocidal Tests

Table 4 shows the MIC values obtained for the five strains studied in the biocidal tests. For both protocols, the data obtained indicate that the CuO-NPs have a good biocidal capacity against the strains tested. In the first protocol (without addition of PVA), values between 125 and 2000 µg/mL were obtained, which were significantly reduced in the second protocol, indicating that the addition of PVA improved the biocidal effect of the nanoparticles by 50 to 75%, resulting in very low MIC values between 62.5 and 500 µg/mL. PVA seems to have dispersing properties that keep the colloidal suspensions of nanoparticles more homogeneous during the tests. Some authors had pointed out this characteristic [

32] and in a previous work with CuO-NPs synthesised from the bacteria Staphylococcus epidermidis, this aspect was confirmed [

18].

There are not many works analysing the biocidal activity of CuO-NPs based on the CLSI standard protocol M07-A9. In most cases, more practical and simpler methods based on diffusion in agar wells or disc diffusion are chosen, which give less accurate results based on the measurement of the microbial inhibition halo. However, some authors have developed protocols that make it possible to compare the efficacy of the nanoparticles obtained in the present work. This is the case of Dadi et al. [

33] who, working with CuO-NPs obtained by the sol-gel method, tested the two previous diffusion methods and obtained different results. At the same time, they analysed the growth curves of the microorganisms studied to conclude that these nanoparticles have a high capacity to transport toxic species such as Cu, to which the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 9027), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 8739) showed high sensitivity during the exponential phase of growth. The authors determined an equivalent critical concentration of 2.3 ± 0.2 mmol/L (146.2 µg/ml) in the three cases. In a recent work, CuO-NPs were obtained by green chemistry from Rosmarinus officinalis leaf extract and found MICs of 1560 µg/mL for E. coli and 3120 µg/mL for S. aureus and Candida albicans, respectively [

34]. Starting from Cupressocyparis leylandii leaf extracts, other works have found lower MIC values for E. coli and B. subtilis of 250 µg/mL and 500 µg/mL, respectively [

35]. Some authors have synthesised CuO-NPs from endophytic fungi such as Aspergillus terreus and found values similar to those reported in this work: 100 µg/mL for E. coli and S. aureus and 250 µg/mL for P. aeruginosa [

36]. In general, the results obtained in this work were in similar ranges or even better than those reported by other authors.

4. Conclusions

The results obtained in this work show that the filamentous fungus Penicillium sp. 8L2 has a good capacity to remove Cu(II) ions from synthetic solutions with a qmax of 25.79 mg/g for the Langmuir model. At the same time, its cell extract showed excellent properties for use in the green synthesis of CuO-NPs. These nanoparticles had very small sizes, between 12 and 32 nm, and offered good MIC values against the five microorganisms tested, ranging from 62.5 to 500 µg/ml, noting that the biocidal effect was improved by the addition of PVA at 10% of the weight of the nanoparticles. In general, Penicillium sp. 8L2 is a microorganism with high potential for use in biotechnology applied to the bioremediation of copper in wastewater and also in the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles intended for the control of pathogenic microorganisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.M. and F.E.; Methodology, A.J.M. and F.E.; Validation, A.J.M. and F.E.; Formal analysis, A.J.M., F.E. and M.M.; Investigation, A.J.M. and C.M.; Resources, F.E. and M.M.; Data curation, A.J.M., F.E. and M.M.; Writing—original draft, A.J.M., C.M., M.M. and F.E.; Writing—review & editing, A.J.M., F.E., M.M., E.R. and C.M.; Supervision, F.E., M.M. and E.R.; Project administration, F.E.; Funding acquisition, F.E.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. Plan estatal de Investigación Científica, Técnica y de Innovación 2021-2023. Ref. TED2021-129552B-100.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

CICT technical staff of the University of Jaén.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rob, M. M.; Akhter, D.; Islam, T.; Bhattacharjya, D. K.; Khan, M. S. S.; Islam, F.; Chen, J. Copper stress in rice: perception, signaling, bioremediation and future prospects. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 302, 154314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adrees, M.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Abbas, F.; Farid, M.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Irshad, M.K.; Bharwana, S. A. The effect of excess copper on growth and physiology of important food crops: a review. ESPR. 2015, 22, 8148–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhanjaf, A.Ah.M.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, M.; Kumar, R.; Arora, N.K; Kumar, B.; Umar, Ah.; Baskoutas, S.; Mukherjee, T.K. Microbial strategies for copper pollution remediation: Mechanistic insights and recent advances. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 346, 123588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Tanjil, H.; Akter, S.; Hossain, M. S; Iqbal, A. Evaluation of physical and heavy metal contamination and their distribution in waters around Maddhapara Granite Mine, Bangladesh. Water Cycle. 2024, 5, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggere, G.; Gasparin, A.; Barbosa, J. Z.; Melo, G. W.; Corrêa, R. S.; Motta, A. C. V. Soil contamination by copper: Sources, ecological risks, and mitigation strategies in Brazil. J. Trace Elem. Min. 2023, 4, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballabio, C.; Panagos, P.; Lugato, E.; Huang, J. H.; Orgiazzi, A.; Jones, A.; Fernández-Ugalde, O.; Borrelli, P.; Montanarella, L. Copper distribution in European topsoils: An assessment based on LUCAS soil survey. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secu, C.V.; Lesenciuc, D.C. Copper concentration in the vineyard and forest topsoils. A comparative study with individual pollution índices. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Han, G.; Zeng, J.; Liang, B.; Zhu, G.; Zhao, Y. Development of copper contamination trajectory on the soil systems: A review on the application for stable copper isotopes. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 36, 103795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, C.E.; Igbokwe, A.M.; Suru, S.M.; Dike, C.C.; Mbachu, A.N.; Maduka, H.C.Ch. Evaluating the human health risks of heavy metal contamination in copper and steel factory effluents in Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 12, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Alharthy, R. D.; Zubair, M.; Ahmed, M.; Hameed, A.; Rafique, S. Toxic and heavy metals contamination assessment in soil and water to evaluate human health risk. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Long, M. Copper Toxicity in Animals: A Review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsvetkov, P.; Coy, S.; Petrova, B.; Dreishpoon, M.; Verma, A.; Abdusamad, M.; Rossen, J.; Joesch-Cohen, L.; Humeidi, R.; Golub, T. R. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Sci. 2022, 375(6586), 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaashikaa, P.R.; Palanivelu, J.; Hemavathy, R.V. Sustainable approaches for removing toxic heavy metal from contaminated water: A comprehensive review of bioremediation and biosorption techniques. Chemosphere 2024, 357, 141933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringu, T.; Das, A.; Ghosh, S.; Pramanik, N. Exploring the potential of copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) for sustainable environmental bioengineering applications. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreslassie, Y.T.; Gebremeskel, F.G. Green and cost-effective biofabrication of copper oxide nanoparticles: Exploring antimicrobial and anticancer applications. Biotechnol. Rep. 2024, 41, e00828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Ruiz, E.; Abriouel, H.; Gálvez, A.; Ezzouhri, L.; Lairini, k.; Espínola, F. Heavy metal tolerance of microorganisms isolated from wastewaters: Identification and evaluation of its potential for biosorption. J. Chem. Eng. 2012, 210, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Espínola, F.; Ruiz, E.; Cuartero, M.; Castro, E. Biotechnological use of the ubiquitous fungus Penicillium sp. 8L2: biosorption of Ag(I) and synthesis of silver nanoparticles. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Espinola, F.; Moya, M.; Martín, C.; Ruiz, E. Cu(II) Biosorption and Synthesis of CuO Nanoparticles by Staphylococcus epidermidis CECT 4183: Evaluation of the Biocidal Effect. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Espínola, F.; Ruiz, E.; Moya, M.; Castro, E. Ag(I) Biosorption and Green Synthesis of Silver/Silver Chloride Nanoparticles by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa 1S1. Nanomater. 2023, 13(2), 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Espínola, F.; Ruiz, E.; Barbosa-Dekker, A.M.; Dekker, R.F.H.; Castro, E. Biosorption mechanisms of Ag(I) and the synthesis of nanoparticles by the biomass from Botryosphaeria rhodina MAMB-05. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. Adsorption of gases on plane surface of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Adsorption in solutions. Phys. Chem. 1906, 57, 384–410. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Joshi, H.K.; Vishwakarma, M.Ch.; Sharma, H.; Joshi, S.K.; Bhandari, N.S. Biosorption of copper and lead ions onto treated biomass Myrica esculenta: Isotherms and kinetics studies. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2023, 19, 100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, D.H.; Rather, M.A. Kinetic and thermodynamic investigations of copper (II) biosorption by green algae Chara vulgaris obtained from the waters of Dal Lake in Srinagar (India). JWPE 2024, 58, 104850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, J.T.; Oh, S. Biosorption of Cd(II), Co(II), and Cu(II) onto Microalgae under Acidic and Neutral Conditions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkman, M.; Moulai-Mostefa, N.; Zouambia, Y. Biosorption of Cu(II) from aqueous solutions by the residues of cider vinegar as new biosorbents: comparative study with modified citrange peels. Desalin. Water Treat 2019, 142, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Lan, Ch.Q. Mechanism of heavy metal ion biosorption by microalgal cells: A mathematic approach. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, M.Ch.; Joshi, H.K.; Tiwari, P.; Bhandari, N.S.; Joshi, S.K. Thermodynamic, kinetic, and equilibrium studies of Cu(II), Cd(II), Ni(II), and Pb(II) ion biosorption onto treated Ageratum conyzoid biomass. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274(2), 133001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedefoglu, N.; Er, S.; Veryer, K.; Zalaoglu, Y.; Bozok, F. Green synthesized CuO nanoparticles using macrofungi extracts: Characterization, nanofertilizer and antibacterial effects. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 309, 128393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Th.Th.Th.; Nguyen, Y.N.N.; Tran, B.Th.; Nguyen, T.Th.Th.; Tran, Th.V. Green synthesis of CuO, ZnO and CuO/ZnO nanoparticles using Annona glabra leaf extract for antioxidant, antibacterial and photocatalytic activities. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabea, A.; Naeem, E.; Balabel, N.M.; Daigham, Gh.E. Management of potato brown rot disease using chemically synthesized CuO-NPs and MgO-NPs. Bot. Stud. 2023, 64, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirelkhatim, A.; Mahmud, Sh.; Seeni, A.; Kaus, N.H.M.; Ann, L.Ch.; Bakhori, S.K.M.; Hasan, H.; Mohamad, D. Review on Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Antibacterial Activity and Toxicity Mechanism. Nanomicro Lett. 2015, 7, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadi, R.; Azouani, R.; Traore, M.; Mielcarek, Ch.; Kanaev, A. Antibacterial activity of ZnO and CuO nanoparticles against gram positive and gram negative strains. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 104, 109968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroda, M.D.; Deressa, T.L.; Tiwikrama, A.H.; Chala, T.F. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Rosmarinus officinalis leaf extract and evaluation of its antimicrobial activity. Next Mat. 2025, 7, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfadji, Ah.; Naous, M.; Rajendrachari, Sh.; Ceylan, Y.; Ceylan, K.B.; Shekar, P.V.R. Effective investigation of electro-catalytic, photocatalytic, and antimicrobial properties of porous CuO nanoparticles green synthesized using leaves of Cupressocyparis leylandii. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1301, 137318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, Sh.A.; El-Sayed, E.R.; Mohamed, S.S.; El-seoud, M.A.A.; Elmehlawy, A.A.; Abdou, D.A.M. Novel mycosynthesis of Co3O4, CuO, Fe3O4, NiO, and ZnO nanoparticles by the endophytic Aspergillus terreus and evaluation of their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol, 2021; 105, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).