Submitted:

04 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

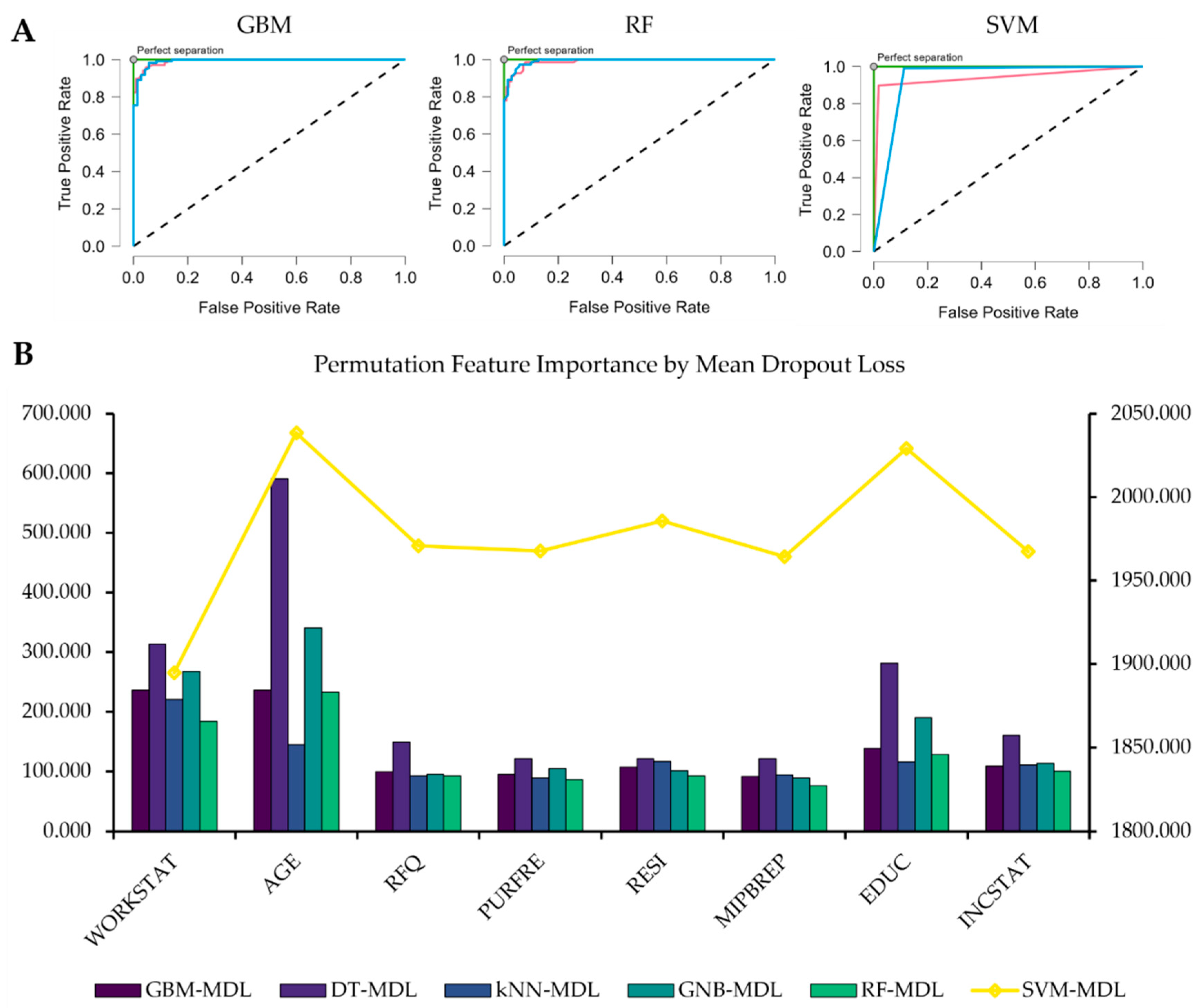

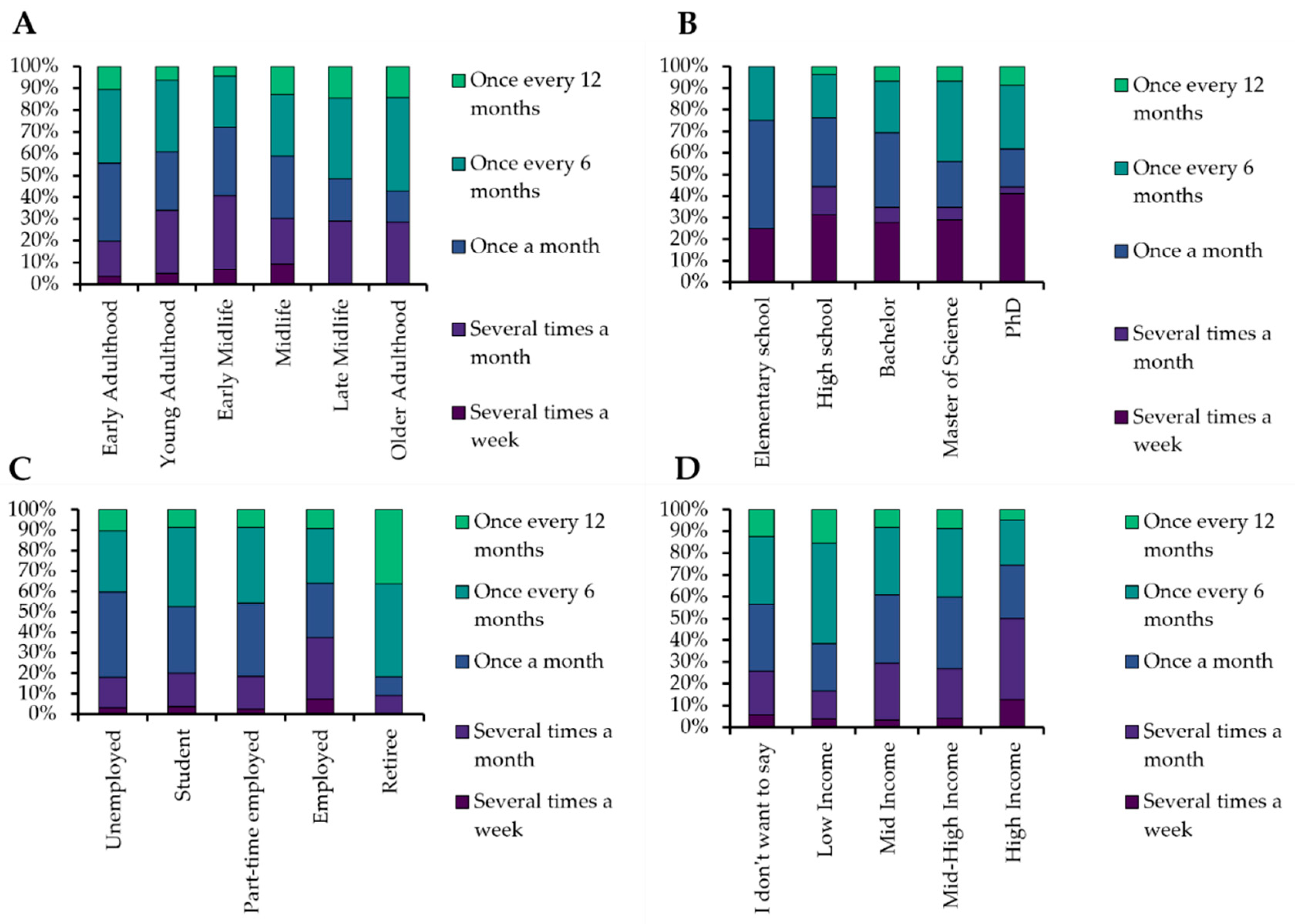

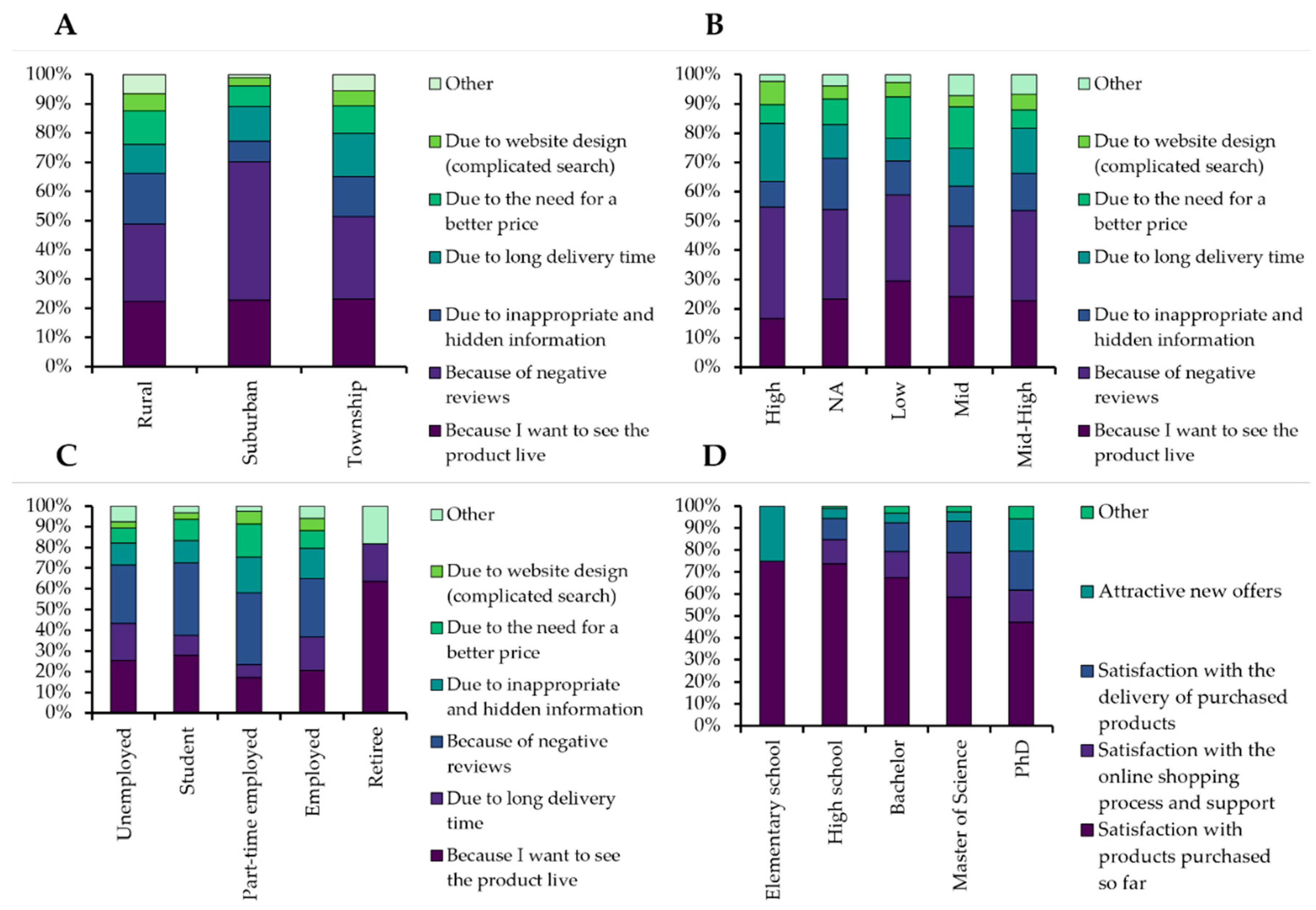

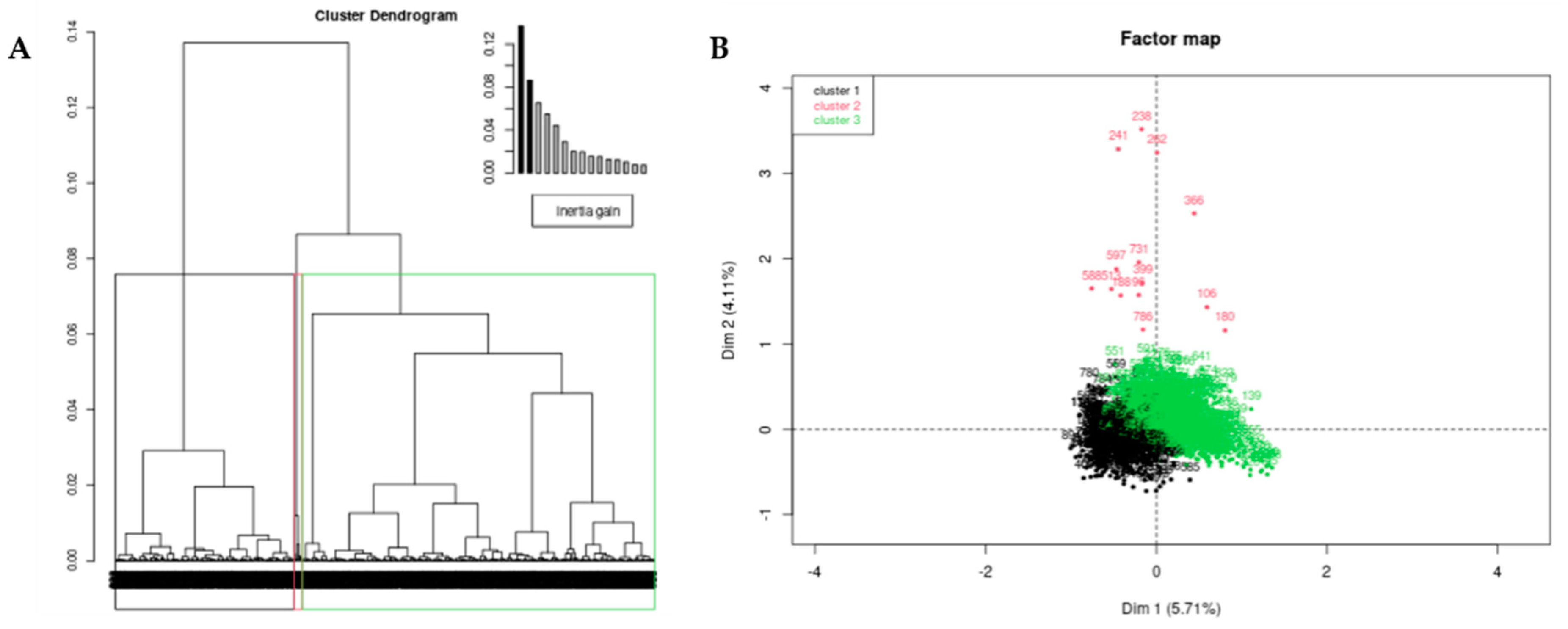

The rapid growth of e-commerce has transformed customer behaviours, demanding deeper insights into how demographic factors shape online user preferences. To understand the impact of these changes, this study performs a threefold analysis. Firstly, the study investigates how demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, education, income) influence e-customer preferences in Serbia. From a sample of n = 906 respondents, we test conditional dependencies between demographics and user preferences – “purchase frequency”, “the most important property when buying for the first time”, “the most important property before repeating a purchase”, and “reasons for quitting an online purchase”. From a hypothetical framework of 24 tested hypotheses, the study successfully rejects 8/24 (with p < 0.05), suggesting a high association between demographics with purchase frequency (p < 0.01) and reasons for quitting the purchase (p < 0.01). However, although reported test statistics suggest an association, understanding how interactions between categories shape e-customer profiles is lacking. As a consequence, the second part considers an MCA-HCPC (Multiple Correspondence Analysis with Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components) to identify user profiles. The analysis reveals three main clusters : (1) young female unemployed e-customers driven mainly by customer reviews; (2) retirees and older adults with infrequent purchases, hesitant to buy without experiencing the product in person; (3) employed, highly educated, male midlife adults who prioritise fast and accurate delivery over price. In the third stage, the study uses identified clusters as labels for Machine Learning (ML) classification through the following algorithms: Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), Decision Tree (DT), k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Gaussian Naïve Bayes (GNB), Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM). The results suggest high classification performance of GBM (AUROC = 0.994), RF (AUROC = 0.994) and SVM (AUROC = 0.902) in identifying user profiles. Lastly, after performing Permutation Feature Importance (PFI), the findings suggest that age, work status, education, and income are the main determinants of shaping e-customer profiles and developing marketing strategies.

Keywords:

MSC: 62H25; 62H30; 62H17; 62F03

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Aims and Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Multistage Model of Data Workflow Framework

2.2. Data Collection and Sample Size

2.3. Research Hypothesis Framework

2.4. Multiple Correspondence Analysis Hierarchical Clustering of Principal Components

2.5. Machine Learning Classifiers

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

3.3. Multiple Correspondence Analysis

3.4. Classification Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Hypothesis Testing Results

4.2. Multiple Correspondence Analysis With Hierarchical Clustering on PCs

4.3. Validity of Findings from Classifiers and Feature Importance

5. Conclusions

5.1. Concluding Remarks

5.2. Limitations of the Study

5.3. Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Authors Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Non-Statistically Significant Findings

| Variables | Chi-Squared Tests | Value | df | p | Cramer's V | VS-MPR* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESI - PURFRE | χ2 test statistic | 13.502 | 8 | 0.096 | 0.086 | 1.638 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 14.657 | 8 | 0.066 | 2.047 | ||

| AGE - RFQ | χ2 test statistic | 43.165 | 30 | 0.057 | 0.098 | 2.262 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 42.747 | 30 | 0.062 | 2.141 | ||

| EDU - RFQ | χ2 test statistic | 21.600 | 24 | 0.603 | 0.077 | 1.000 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 21.506 | 24 | 0.609 | 1.000 | ||

| AGE - MIPB1T | χ2 test statistic | 37.455 | 25 | 0.052 | 0.091 | 2.386 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 36.759 | 25 | 0.061 | 2.160 | ||

| EDU - MIPB1T | χ2 test statistic | 24.007 | 20 | 0.242 | 0.081 | 1.071 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 19.474 | 20 | 0.491 | 1.000 | ||

| RESI - MIPB1T | χ2 test statistic | 10.860 | 10 | 0.369 | 0.077 | 1.000 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 13.190 | 10 | 0.213 | 1.116 | ||

| AGE - MIPBREP | χ2 test statistic | 20.786 | 20 | 0.410 | 0.076 | 1.000 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 19.676 | 20 | 0.418 | 1.000 | ||

| RESI - MIPBREP | χ2 test statistic | 12.540 | 8 | 0.129 | 0.083 | 1.394 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 14.275 | 8 | 0.117 | 1.896 | ||

| INCSTAT - MIPBREP | χ2 test statistic | 6.601 | 16 | 0.980 | 0.043 | 1.000 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 6.959 | 16 | 0.974 | 1.000 | ||

| INCSTAT - MIPB1T | χ2 test statistic | 22.425 | 20 | 0.318 | 0.079 | 1.010 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 23.378 | 20 | 0.271 | 1.040 | ||

| WORKSTAT - MIPBREP | χ2 test statistic | 23.385 | 16 | 0.104 | 0.080 | 1.564 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 18.538 | 16 | 0.293 | 1.023 | ||

| WORKSTAT - MIPB1T | χ2 test statistic | 22.403 | 20 | 0.319 | 0.319 | 1.009 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 23.386 | 20 | 0.270 | 1.040 | ||

| GENDER - PURFRE | χ2 test statistic | 6.853 | 8 | 0.553 | 0.061 | 1.000 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 7.311 | 8 | 0.503 | 1.000 | ||

| GENDER - MIPBREP | χ2 test statistic | 14.223 | 8 | 0.074 | 0.089 | 1.914 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 13.556 | 8 | 0.094 | 1.654 | ||

| GENDER - MIPB1T | χ2 test statistic | 6.432 | 10 | 0.778 | 0.060 | 1.000 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 7.038 | 10 | 0.722 | 1.000 | ||

| GENDER - RFQ | χ2 test statistic | 20.983 | 12 | 0.051 | 0.108 | 2.436 |

| G2 Likelihood ratio | 22.061 | 12 | 0.037 | 3.025 |

| Categories | PC1 | CTR | cos2 | v.test | PC2 | CTR | cos2 | v.test | PC3 | CTR | cos2 | v.test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Adulthood | -1.22 | 18.57 | 0.58 | -22.93 | -0.26 | 1.15 | 0.03 | -4.88 | 0.68 | 9.01 | 0.18 | 12.67 |

| Student | -1.20 | 15.70 | 0.47 | -20.57 | -0.33 | 1.58 | 0.03 | -5.58 | 0.65 | 7.20 | 0.14 | 11.05 |

| High School | -0.67 | 8.83 | 0.36 | -18.07 | -0.06 | 0.11 | 0.00 | -1.73 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 1.99 |

| Rural | -0.74 | 3.24 | 0.08 | -8.73 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.64 | -0.44 | 1.84 | 0.03 | -5.21 |

| Income_NA | -0.45 | 2.21 | 0.07 | -7.76 | -0.14 | 0.31 | 0.01 | -2.49 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| Once 6 months | -0.34 | 1.55 | 0.05 | -6.76 | 0.27 | 1.39 | 0.03 | 5.47 | -0.41 | 3.63 | 0.08 | -8.22 |

| MIPBREP_Satisf_Product | -0.14 | 0.62 | 0.04 | -6.30 | -0.08 | 0.24 | 0.01 | -3.33 | -0.27 | 3.45 | 0.15 | -11.82 |

| RFQ_Product_Live | -0.35 | 1.24 | 0.04 | -5.72 | 0.70 | 6.90 | 0.15 | 11.54 | -0.14 | 0.30 | 0.01 | -2.23 |

| Low Income | -0.58 | 1.27 | 0.03 | -5.32 | 0.50 | 1.30 | 0.02 | 4.59 | -0.41 | 1.03 | 0.02 | -3.80 |

| Once 12 months | -0.50 | 1.05 | 0.03 | -4.85 | 0.82 | 3.87 | 0.07 | 7.97 | -0.41 | 1.14 | 0.02 | -4.01 |

| Unemployed | -0.55 | 0.98 | 0.02 | -4.64 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.72 |

| Once a month | -0.13 | 0.22 | 0.01 | -2.55 | -0.24 | 1.02 | 0.02 | -4.66 | 0.20 | 0.81 | 0.02 | 3.86 |

| RFQ_Price | -0.25 | 0.27 | 0.01 | -2.45 | -0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | -0.44 | -0.25 | 0.41 | 0.01 | -2.41 |

| RFQ_Negative_Reviews | -0.08 | 0.08 | 0.00 | -1.51 | -0.41 | 3.10 | 0.07 | -8.11 | -0.15 | 0.47 | 0.01 | -2.93 |

| Part-time | -0.14 | 0.08 | 0.00 | -1.36 | -0.12 | 0.08 | 0.00 | -1.14 | -0.35 | 0.79 | 0.01 | -3.33 |

| Retiree | -0.35 | 0.07 | 0.00 | -1.16 | 6.91 | 35.30 | 0.59 | 23.04 | 1.38 | 1.62 | 0.02 | 4.59 |

| MIPBREP_Attractive _offers | -0.13 | 0.04 | 0.00 | -0.91 | 0.96 | 2.76 | 0.05 | 6.57 | 0.47 | 0.78 | 0.01 | 3.25 |

| Elementary | -0.43 | 0.04 | 0.00 | -0.86 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.85 | -0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.20 |

| Suburban | -0.06 | 0.02 | 0.00 | -0.65 | -0.27 | 0.49 | 0.01 | -2.86 | -0.66 | 3.45 | 0.06 | -7.05 |

| RFQ_Missinformation | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.58 | -0.15 | 0.19 | 0.00 | -1.81 | -0.36 | 1.21 | 0.02 | -4.24 |

| Older Adulthood | 0.53 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 1.40 | 7.60 | 27.15 | 0.45 | 20.16 | 2.62 | 3.76 | 0.05 | 6.96 |

| Late Midlife | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 1.59 | 0.79 | 2.59 | 0.05 | 6.43 | -0.98 | 4.64 | 0.07 | -7.99 |

| Mid-High Income | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 1.67 | -0.19 | 0.62 | 0.01 | -3.60 | -0.08 | 0.12 | 0.00 | -1.50 |

| RFQ_Website | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 2.09 | -0.39 | 0.47 | 0.01 | -2.71 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 1.71 |

| MIPBREP_Other | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 2.51 | -0.14 | 0.03 | 0.00 | -0.65 | -0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.08 |

| Mid Income | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 2.67 | 0.47 | 3.01 | 0.06 | 7.62 | -0.15 | 0.37 | 0.01 | -2.49 |

| MIPBREP_Shopping_Process | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 3.33 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 1.42 | 0.02 | 4.56 |

| RFQ_Other | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 4.07 | 0.63 | 1.26 | 0.02 | 4.43 | 0.58 | 1.24 | 0.02 | 4.10 |

| MIPBREP_Delivery | 0.47 | 1.13 | 0.03 | 5.12 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.93 | 7.14 | 0.12 | 10.19 |

| Young Adulthood | 0.34 | 1.24 | 0.04 | 5.79 | -0.17 | 0.44 | 0.01 | -2.96 | -0.40 | 2.78 | 0.05 | -6.88 |

| Several times a week | 0.85 | 1.78 | 0.04 | 6.20 | -0.68 | 1.57 | 0.03 | -4.96 | 0.87 | 2.93 | 0.04 | 6.31 |

| RFQ_Long_Delivery | 0.54 | 1.80 | 0.05 | 6.52 | -0.19 | 0.29 | 0.01 | -2.24 | 0.76 | 5.59 | 0.09 | 9.11 |

| Midlife | 0.40 | 1.76 | 0.05 | 6.92 | -0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | -0.66 | -0.67 | 7.81 | 0.15 | -11.55 |

| BSc | 0.30 | 1.53 | 0.06 | 7.09 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 2.44 | -0.32 | 2.73 | 0.06 | -7.50 |

| Town | 0.14 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 7.37 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 1.58 | 0.18 | 1.65 | 0.10 | 9.28 |

| PhD | 1.27 | 2.69 | 0.06 | 7.55 | -0.10 | 0.02 | 0.00 | -0.58 | 1.33 | 4.66 | 0.07 | 7.88 |

| High Income | 0.71 | 3.13 | 0.08 | 8.60 | -0.42 | 1.50 | 0.03 | -5.09 | 0.63 | 3.85 | 0.06 | 7.57 |

| Several times a month | 0.59 | 3.77 | 0.11 | 10.06 | -0.22 | 0.72 | 0.02 | -3.74 | 0.24 | 1.01 | 0.02 | 4.14 |

| Early Midlife | 0.97 | 6.14 | 0.16 | 12.11 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 0.83 | 7.21 | 0.12 | 10.41 |

| MSc | 1.07 | 6.56 | 0.17 | 12.40 | -0.07 | 0.04 | 0.00 | -0.80 | 0.30 | 0.81 | 0.01 | 3.45 |

| Employed | 0.61 | 9.43 | 0.51 | 21.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.26 | 2.70 | 0.09 | -9.09 |

Appendix B. Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering

| Cluster 1 variables | Cla/Mod | Mod/Cla | Global | p value | v.test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE=Early Adulthood | 92.913 | 78.667 | 28.035 | 0.000 | 24.465 |

| WORKSTAT=Student | 97.738 | 72.000 | 24.393 | 0.000 | 24.261 |

| EDUC=High school | 50.860 | 69.000 | 44.923 | 0.000 | 10.295 |

| WORKSTAT=Unemployed | 55.224 | 12.333 | 7.395 | 0.000 | 3.846 |

| RESI=Rural | 48.760 | 19.667 | 13.355 | 0.000 | 3.823 |

| MIPB1T=To have positive customer reviews | 41.554 | 41.000 | 32.671 | 0.000 | 3.722 |

| PURFRE=Once a month | 41.697 | 37.667 | 29.912 | 0.000 | 3.545 |

| GEND=Female | 37.043 | 71.000 | 63.466 | 0.001 | 3.333 |

| INCSTAT=I don't want to say | 42.105 | 32.000 | 25.166 | 0.001 | 3.288 |

| PPL=No | 35.756 | 82.000 | 75.938 | 0.002 | 3.040 |

| RFQ=RFQ_Because of negative reviews | 39.194 | 35.667 | 30.132 | 0.011 | 2.531 |

| CCP=Mobile app | 37.736 | 46.667 | 40.949 | 0.014 | 2.451 |

| GEND=Prefer not to disclose | 75.000 | 2.000 | 0.883 | 0.021 | 2.309 |

| RFQ=RFQ_Because I want to see the product live | 39.423 | 27.333 | 22.958 | 0.029 | 2.179 |

| RFQ=Due to long delivery time | 24.800 | 10.333 | 13.797 | 0.032 | -2.151 |

| MIPB1T=Fast and accurate delivery | 26.733 | 18.000 | 22.296 | 0.028 | -2.201 |

| CCP=SMS | 29.621 | 44.333 | 49.558 | 0.027 | -2.209 |

| PURFRE=Several times a week | 18.000 | 3.000 | 5.519 | 0.016 | -2.401 |

| RFQ=RFQ_Other | 17.021 | 2.667 | 5.188 | 0.013 | -2.483 |

| RESI=Town/township | 30.848 | 70.333 | 75.497 | 0.012 | -2.513 |

| WORKSTAT=Retiree | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.214 | 0.012 | -2.523 |

| RFQ=Due to inappropriate and hidden information | 22.951 | 9.333 | 13.466 | 0.009 | -2.609 |

| INCSTAT=Mid Income | 25.604 | 17.667 | 22.848 | 0.008 | -2.640 |

| AGE=Young Adulthood | 25.893 | 19.333 | 24.724 | 0.008 | -2.671 |

| PPL=Yes | 24.771 | 18.000 | 24.062 | 0.002 | -3.040 |

| GEND=Male | 25.077 | 27.000 | 35.651 | 0.000 | -3.858 |

| PURFRE=Several times a month | 22.018 | 16.000 | 24.062 | 0.000 | -4.075 |

| EDUC=Bachelor | 23.615 | 27.000 | 37.859 | 0.000 | -4.791 |

| EDUC=PhD | 0.000 | 0.000 | 3.753 | 0.000 | -4.926 |

| AGE=Late Midlife | 0.000 | 0.000 | 6.843 | 0.000 | -6.907 |

| EDUC=Master of Science | 7.627 | 3.000 | 13.024 | 0.000 | -6.929 |

| AGE=Early Midlife | 3.759 | 1.667 | 14.680 | 0.000 | -8.851 |

| AGE=Midlife | 0.442 | 0.333 | 24.945 | 0.000 | -14.177 |

| WORKSTAT=Employed | 3.802 | 6.667 | 58.057 | 0.000 | -23.228 |

| Cluster 2 | Cla/Mod | Mod/Cla | Global | p.value | v.test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WORKSTAT=Retiree | 100.000 | 78.571 | 1.214 | 0.000 | 9.891 |

| AGE=Older Adulthood | 100.000 | 50.000 | 0.773 | 0.000 | 7.577 |

| RFQ=I want to see the product live | 4.327 | 64.286 | 22.958 | 0.001 | 3.248 |

| CCP=SMS | 2.450 | 78.571 | 49.558 | 0.031 | 2.153 |

| MIPBREP=Attractive new offers | 6.667 | 21.429 | 4.967 | 0.032 | 2.143 |

| PURFRE=Once every 12 months | 4.651 | 28.571 | 9.492 | 0.043 | 2.023 |

| WORKSTAT=Student | 0.000 | 0.000 | 24.393 | 0.019 | -2.340 |

| AGE=Young Adulthood | 0.000 | 0.000 | 24.724 | 0.018 | -2.363 |

| INCSTAT=Mid-High Income | 0.000 | 0.000 | 29.470 | 0.007 | -2.686 |

| WORKSTAT=Employed | 0.380 | 14.286 | 58.057 | 0.001 | -3.281 |

| Cluster 3 | Cla/Mod | Mod/Cla | Global | p value | v.test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WORKSTAT=Employed | 95.817 | 85.135 | 58.057 | 0.000 | 23.920 |

| AGE=Midlife | 99.115 | 37.838 | 24.945 | 0.000 | 14.315 |

| AGE=Early Midlife | 94.737 | 21.284 | 14.680 | 0.000 | 8.620 |

| EDUC=Master of Science | 91.525 | 18.243 | 13.024 | 0.000 | 6.993 |

| AGE=Late Midlife | 95.161 | 9.966 | 6.843 | 0.000 | 5.734 |

| EDUC=Bachelor | 74.636 | 43.243 | 37.859 | 0.000 | 4.628 |

| EDUC=PhD | 97.059 | 5.574 | 3.753 | 0.000 | 4.470 |

| PURFRE=Several times a month | 77.064 | 28.378 | 24.062 | 0.000 | 4.255 |

| GEND=Male | 73.065 | 39.865 | 35.651 | 0.000 | 3.661 |

| PPL=Yes | 74.312 | 27.365 | 24.062 | 0.001 | 3.233 |

| AGE=Young Adulthood | 74.107 | 28.041 | 24.724 | 0.001 | 3.214 |

| RFQ=Due to inappropriate | 77.049 | 15.878 | 13.466 | 0.003 | 2.980 |

| PURFRE=Several times a week | 82.000 | 6.926 | 5.519 | 0.009 | 2.624 |

| RESI=Town/township | 67.544 | 78.041 | 75.497 | 0.016 | 2.419 |

| MIPB1T=Fast and accur | 71.782 | 24.493 | 22.296 | 0.028 | 2.195 |

| INCSTAT=Mid Income | 71.498 | 25.000 | 22.848 | 0.033 | 2.130 |

| RFQ=Due to long delivery | 73.600 | 15.541 | 13.797 | 0.035 | 2.109 |

| RFQ=Other | 78.723 | 6.250 | 5.188 | 0.044 | 2.010 |

| RFQ=Because of negative | 60.440 | 27.872 | 30.132 | 0.043 | -2.022 |

| CCP=Mobile app | 61.456 | 38.514 | 40.949 | 0.041 | -2.039 |

| PURFRE=Once every 6 months | 60.498 | 28.716 | 31.015 | 0.041 | -2.041 |

| INCSTAT=Low Income | 53.846 | 7.095 | 8.609 | 0.029 | -2.184 |

| GEND=Prefer not to disclose | 25.000 | 0.338 | 0.883 | 0.027 | -2.215 |

| RFQ=RFQ_Because I want to se | 56.250 | 19.764 | 22.958 | 0.002 | -3.097 |

| GEND=Female | 61.565 | 59.797 | 63.466 | 0.002 | -3.163 |

| INCSTAT=I don't want to say | 56.579 | 21.791 | 25.166 | 0.002 | -3.174 |

| PURFRE=Once a month | 57.565 | 26.351 | 29.912 | 0.001 | -3.182 |

| PPL=No | 62.500 | 72.635 | 75.938 | 0.001 | -3.233 |

| AGE=Older Adulthood | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.773 | 0.001 | -3.443 |

| MIPB1T=MIPB1T_To have positive customer reviews | 57.095 | 28.547 | 32.671 | 0.000 | -3.600 |

| WORKSTAT=Unemployed | 43.284 | 4.899 | 7.395 | 0.000 | -3.812 |

| RESI=Rural | 49.587 | 10.135 | 13.355 | 0.000 | -3.818 |

| WORKSTAT=Retiree | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.214 | 0.000 | -4.473 |

| EDUC=High school | 47.666 | 32.770 | 44.923 | 0.000 | -10.136 |

| WORKSTAT=Student | 2.262 | 0.845 | 24.393 | 0.000 | -23.557 |

References

- Svobodová, Z.; Rajchlová, J. Strategic Behavior of E-Commerce Businesses in Online Industry of Electronics from a Customer Perspective. Adm Sci 2020, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yum, K. Enhancing Continuous Usage Intention in E-Commerce Marketplace Platforms: The Effects of Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction, and Trust. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 7617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, Y.; Shams, P.; Hellström, D.; Hjort, K. Online Retail Experience and Customer Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Last Mile Delivery. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2019, 29, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buldeo Rai, H.; Mommens, K.; Verlinde, S.; Macharis, C. How Does Consumers’ Omnichannel Shopping Behaviour Translate into Travel and Transport Impacts? Case-Study of a Footwear Retailer in Belgium. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zennaro, I.; Finco, S.; Calzavara, M.; Persona, A. Implementing E-Commerce from Logistic Perspective: Literature Review and Methodological Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Jo, J. Dynamic Joint Construction and Optimal Operation Strategy of Multi-Period Reverse Logistics Network: A Case Study of Shanghai Apparel E-Commerce Enterprises. J Intell Manuf 2017, 28, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biclesanu, I.; Anagnoste, S.; Branga, O.; Savastano, M. Digital Entrepreneurship: Public Perception of Barriers, Drivers, and Future. Adm Sci 2021, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, M.-C.; Sîrghi, N.; Toth, D.M.-M. Consumers’ Experience and Satisfaction Using Augmented Reality Apps in E-Shopping: New Empirical Evidence. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 9596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, J.; Hellström, D.; Vakulenko, Y. Customer Experience Dimensions in Last-Mile Delivery: An Empirical Study on Unattended Home Delivery. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2023, 53, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrhovac, V.; Vasić, S.; Milisavljević, S.; Dudić, B.; Štarchoň, P.; Žižakov, M. Measuring E-Commerce User Experience in the Last-Mile Delivery. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, D. Internet Prodaja u Republici Srbiji. Pravo-teorija i praksa 2017, 34, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasic, N.; Kilibarda, M.; Kaurin, T. The Influence of Online Shopping Determinants on Customer Satisfaction in the Serbian Market. Journal of theoretical and applied electronic commerce research 2019, 14, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TRADE Serbia - Country Commercial Guide Available online:. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/serbia-ecommerce (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Kaurin, T.; Kilibarda, M.; Fakultet Beograd, S. Analiza Determinanti Elektronske Trgovine Na Tržištu Srbije. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Assael, H. Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Martinović, M.; Barać, R.; Maljak, H. Exploring Croatian Consumer Adoption of Subscription-Based E-Commerce for Business Innovation. Adm Sci 2024, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V.; Govindan, K.; Darbari, J.D.; Jha, P.C. An Optimization Model for Sustainable Solutions towards Implementation of Reverse Logistics under Collaborative Framework. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management 2016, 7, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Saliba, S.; Wrenn, B. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, and Control: Instructor’s Manual; Prentice-hall, 1991; ISBN 0135525144. [Google Scholar]

- MORRIS, M.G.; VENKATESH, V. AGE DIFFERENCES IN TECHNOLOGY ADOPTION DECISIONS: IMPLICATIONS FOR A CHANGING WORK FORCE. Pers Psychol 2000, 53, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, W.W. Buying, Searching, or Browsing: Differentiating between Online Shoppers Using in-Store Navigational Clickstream. Journal of consumer psychology 2003, 13, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar, V.M. Customers’ Demographic Profile and Satisfaction in E-Banking Services: A Study of Indian Banks. International Journal for Business, Strategy & Management 2011, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, J.; Frade, R.; Ascenso, R.; Prates, I.; Martinho, F. Generation Z and Key-Factors on E-Commerce: A Study on the Portuguese Tourism Sector. Adm Sci 2020, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barutcu, S. E-Customer Satisfaction in the E-Tailing Industry: An Empirical Survey for Turkish E-Customers. Ege Academic Review 2010, 10, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, I. A Demographic Study of Buying Spontaneity on E-Shoppers: Preference Kolkata (West Bengal). Journal of Technology Management for Growing Economies 2015, 6, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Z.A.; Qadri, F.A. Role of E-Retailer’s Image in Online Consumer Behaviour – Empirical Findings from E-Customers’ Perspective in Saudi Arabia. International Business Research 2018, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkalčič, M.; Chen, L. Personality and Recommender Systems. In Recommender Systems Handbook; Springer US: New York, NY, 2022; pp. 757–787. [Google Scholar]

- Hristoski, I.; Kostoska, O. On the Taxonomies and Typologies of E-Customers in B2C e-Commerce. Balkan and Near Eastern Journal of Social Sciences 2018, 4, 130–148. [Google Scholar]

- Swarnakar, P.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S. Why Generation Y Prefers Online Shopping: A Study of Young Customers of India. International Journal of Business Forecasting and Marketing Intelligence 2016, 2, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Xu, H.; Yan, H.; Lin, L. User Demographic Prediction Based on the Fusion of Mobile and Survey Data. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 111507–111527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, P.; Palesi, L.A.I.; Nesi, P.; Pantaleo, G. Multi Clustering Recommendation System for Fashion Retail. Multimed Tools Appl 2023, 82, 9989–10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruba Manjunath, Y.S.; Kashef, R.F. Distributed Clustering Using Multi-Tier Hierarchical Overlay Super-Peer Peer-to-Peer Network Architecture for Efficient Customer Segmentation. Electron Commer Res Appl 2021, 47, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hørlück, J.; Christiansen, T.; Hansen, L.K.; Larsen, J. Are All E-Customers Alike? In Proceedings of the 1st Nordic Workshop on Electronic Commerce, Halmstad, Sweden, May 28 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, S.; Farooqi, R. Moderating Effect Of Demographic Variables on Attitude towards Online Shopping: An Empirical Study Using PROCESS. IOSR Journal of Business and Management 2017, 19, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Noorshella, C.N.; Abdullah, A.M.; Nursalihah, A.R. Examining the Key Factors Affecting E-Service Quality of Small Online Apparel Businesses in Malaysia. Sage Open 2015, 5, 215824401557655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, P.; Kaur, N.; Singh, T. A Review of Factors Affecting Online Buying Behavior. Apeejay Journal of Management and Technology 2016, 11, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Darzi, M.A. Exploring the Influence of Consumer Demographics on Online Purchase Benefits. FIIB Business Review 2019, 8, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettich, D.; Hattula, S.; Bornemann, T. Consumer Decision-Making of Older People: A 45-Year Review. Gerontologist 2018, 58, e349–e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RODGERS, S.; HARRIS, M.A. Gender and E-Commerce: An Exploratory Study. J Advert Res 2003, 43, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolsaker, A.; Payne, C. Engendering Trust in E-commerce: A Study of Gender-based Concerns. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 2002, 20, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Miguel, F.J.; Agudo-Peregrina, Á.F.; Chaparro-Peláez, J. Influences of Gender and Product Type on Online Purchasing. J Bus Res 2015, 68, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Møller Jensen, J. Shopping Orientation and Online Clothing Purchases: The Role of Gender and Purchase Situation. Eur J Mark 2009, 43, 1154–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, M.B.; Elliott, G. Role of Demographics, Social Connectedness and Prior Internet Experience in Adoption of Online Shopping: Applications for Direct Marketing. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing 2011, 19, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young Kim, E.; Kim, Y. Predicting Online Purchase Intentions for Clothing Products. Eur J Mark 2004, 38, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, C.; Lien, D. E-Commerce and Consumer’s Purchasing Behaviour. Appl Econ 2003, 35, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, R.E.; Sabherwal, R. Determinants Of Retail Electronic Purchasing: A Multi-Period Investigation1. INFOR: Information Systems and Operational Research 2002, 40, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, P. Does Demographics Affect Purchase Frequency in Online Retail? International Journal of Online Marketing 2017, 7, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveny, S.M.; Parhasarathy, M. Customer Switching Behavior in Online Services: An Exploratory Study of the Role of Selected Attitudinal, Behavioral, and Demographic Factors. J Acad Mark Sci 2001, 29, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Niu, C. E-COMMERCE PARTICIPATION AND HOUSEHOLD INCOME GROWTH IN TAOBAO VILLAGES. Poverty & Equity Global Practice, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Agudo-Peregrina, Á.F.; Hernández-García, Á.; Acquila-Natale, E. The Effect of Income Level on E-Commerce Adoption. In Encyclopedia of E-Commerce Development, Implementation, and Management; IGI Global, 2016; pp. 2239–2255. [Google Scholar]

- Paun, C.; Ivascu, C.; Olteteanu, A.; Dantis, D. The Main Drivers of E-Commerce Adoption: A Global Panel Data Analysis. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2024, 19, 2198–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çebi Karaaslan, K. Determinants of Online Shopping Attitudes of Households in Turkey. Journal of Modelling in Management 2022, 17, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, K.Ç. Analysis of the Factors Affecting Credit Card Use and Online Shopping Attitudes of Households in Turkey with the Bivariate Probit Model. International Journal of Electronic Finance 2022, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Asif, M.; Sajjad, W. Impact of Employment Status on Online Shopping Preferences: A Case Study of Women in Rawalpindi. Journal of Business Insight and Innovation 2022, 1, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Basu, R. Online Consumer Shopping Behaviour: A Review and Research Agenda. Int J Consum Stud 2023, 47, 815–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheah, J.; Lim, X. Online Shopping Cart Abandonment: A Review and Research Agenda. Int J Consum Stud 2023, 47, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C.; König, G.; Herbinger, J.; Freiesleben, T.; Dandl, S.; Scholbeck, C.A.; Casalicchio, G.; Grosse-Wentrup, M.; Bischl, B. General Pitfalls of Model-Agnostic Interpretation Methods for Machine Learning Models. 2022; 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Orošnjak, M.; Beker, I.; Brkljač, N.; Vrhovac, V. Predictors of Successful Maintenance Practices in Companies Using Fluid Power Systems: A Model-Agnostic Interpretation. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburg, M. Basic Statistics: A Modern Approach, 3rd ed.; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Burkolter, D.; Kluge, A. Online Consumer Behavior and Its Relationship with Socio-Demographics, Shopping Orientations, Need for Emotion, and Fashion Leadership. Journal of Business and Media Psychology 2011, 2, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D.C. Chi-Square Test - Analysis of Contingency Tables; Burlington. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, N.; Krzywinski, M. Interpreting P Values. Nat Methods 2017, 14, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, L.G.; Curran-Everett, D.; Vowler, S.L.; Drummond, G.B. The Fickle P Value Generates Irreproducible Results. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, N.; Krzywinski, M. P Values and the Search for Significance. Nat Methods 2017, 14, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E.-J. A Practical Solution to the Pervasive Problems Ofp Values. Psychon Bull Rev 2007, 14, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.M.R.-R.; Puga, J.L. Deciding on Null Hypotheses Using P-Values or Bayesian Alternatives: A Simulation Study. Psicothema 2018, 30, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Test | Value | df | p | Cramer's V | VS-MPR* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE - PURFRE | χ2 test statistic | 50.519 | 20 | 0.001 | 0.118 | 229.606 |

| G2 likelihood ratio | 54.838 | 20 | 0.001 | 843.603 | ||

| EDU - PURFRE | χ2 test statistic | 38.498 | 16 | 0.001 | 0.103 | 43.022 |

| G2 likelihood ratio | 39.004 | 16 | 0.001 | 49.631 | ||

| RESI - RFQ | χ2 test statistic | 24.599 | 12 | 0.017 | 0.117 | 5.349 |

| G2 likelihood ratio | 25.710 | 12 | 0.012 | 7.025 | ||

| EDU - MIPBREP | χ2 test statistic | 33.834 | 16 | 0.006 | 0.097 | 12.456 |

| G2 likelihood ratio | 30.371 | 16 | 0.016 | 5.516 | ||

| INCSTAT - PURFRE | χ2 test statistic | 52.421 | 16 | 0.001 | 0.120 | 3392.513 |

| G2 likelihood ratio | 49.376 | 16 | 0.001 | 1221.498 | ||

| INCSTAT - RFQ | χ2 test statistic | 41.019 | 24 | 0.017 | 0.106 | 5.413 |

| G2 likelihood ratio | 41.087 | 24 | 0.016 | 5.484 | ||

| WORKSTAT - PURFRE | χ2 test statistic | 51.892 | 16 | 0.001 | 0.120 | 2834.207 |

| G2 likelihood ratio | 50.487 | 16 | 0.001 | 1766.807 | ||

| WORKSTAT - RFQ | χ2 test statistic | 50.697 | 24 | 0.001 | 0.118 | 47.147 |

| G2 likelihood ratio | 54.134 | 24 | 0.001 | 115.292 |

| Algorithm | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBM | 0.939 | 0.943 | 0.939 | 0.936 | 0.994 |

| DT | 0.917 | 0.902 | 0.917 | 0.909 | 0.894 |

| kNN | 0.884 | 0.870 | 0.884 | 0.876 | 0.796 |

| GNB | 0.939 | 0.942 | 0.939 | 0.936 | 0.843 |

| RF | 0.928 | 0.914 | 0.928 | 0.920 | 0.994 |

| SVM | 0.950 | 0.954 | 0.950 | 0.949 | 0.902 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).