Submitted:

04 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

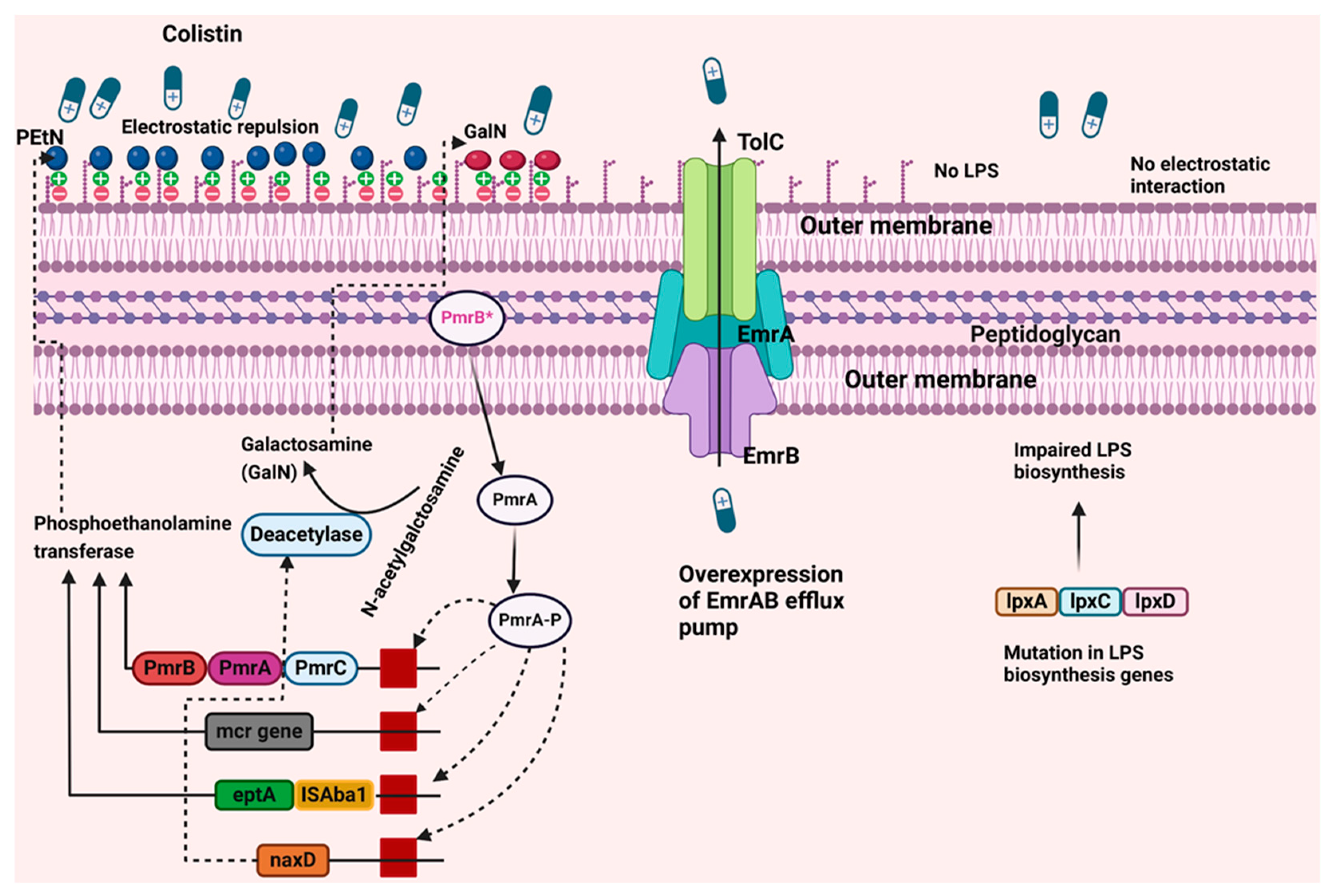

2. Colistin Mechanism of Action

3. Mechanism of Colistin Resistance in A. baumannii

4. Biological Cost of Acquiring Colistin-Resistant Trait

5. Available Therapies and Future Prospects for Col-RAB Infections

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Authors Contribution

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang M, Chen X, Liu S, Zhang Z, Li N, Dong C, et al. Epidemiological Analysis of Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates in a Tertiary Hospital Over a 12-Year Period in China. Frontiers in public health. 2021, 9:707435. [CrossRef]

- WHO WHO: WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: bacterial pathogens of public health importance to guide research, development and strategies to prevent and control antimicrobial resistance. In.; 2024.

- Serapide F, Guastalegname M, Gullì SP, Lionello R, Bruni A, Garofalo E, et al. Antibiotic Treatment of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections in View of the Newly Developed β-Lactams: A Narrative Review of the Existing Evidence. 2024, 13, 506.

- Cain AK, Hamidian M. Portrait of a killer: Uncovering resistance mechanisms and global spread of Acinetobacter baumannii. PLOS Pathogens. 2023, 19, e1011520. [CrossRef]

- Yang S, Wang H, Zhao D, Zhang S, Hu C. Polymyxins: recent advances and challenges. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed Ahmed MAE, Zhong LL, Shen C, Yang Y, Doi Y, Tian GB. Colistin and its role in the Era of antibiotic resistance: an extended review (2000-2019). Emerging microbes & infections. 2020, 9, 868–885. [CrossRef]

- Rabi R, Enaya A, Sweileh MW, Aiesh BM, Namrouti A, Hamdan ZI, et al. Comprehensive Assessment of Colistin Induced Nephrotoxicity: Incidence, Risk Factors and Time Course. Infection and drug resistance. 2023, 16:3007-17. [CrossRef]

- Torres DA, Seth-Smith HMB, Joosse N, Lang C, Dubuis O, Nüesch-Inderbinen M, et al. Colistin resistance in Gram-negative bacteria analysed by five phenotypic assays and inference of the underlying genomic mechanisms. BMC Microbiology. 2021, 21, 321. [CrossRef]

- Sharma J, Sharma D, Singh A, Sunita K. Colistin Resistance and Management of Drug Resistant Infections. The Canadian journal of infectious diseases & medical microbiology = Journal canadien des maladies infectieuses et de la microbiologie medicale. 2022, 2022:4315030. [CrossRef]

- Lencina FA, Bertona M, Stegmayer MA, Olivero CR, Frizzo LS, Zimmermann JA, et al. Prevalence of colistin-resistant Escherichia coli in foods and food-producing animals through the food chain: A worldwide systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e26579. [CrossRef]

- Kumar H, Chen BH, Kuca K, Nepovimova E, Kaushal A, Nagraik R, et al. Understanding of Colistin Usage in Food Animals and Available Detection Techniques: A Review. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI. 2020, 10(10). [CrossRef]

- Mondal AH, Khare K, Saxena P, Debnath P, Mukhopadhyay K, Yadav D. A Review on Colistin Resistance: An Antibiotic of Last Resort. Microorganisms. 2024, 12(4). [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Yang K, Han ML, Yuan B, Li J, Gong B, et al. Outer Membranes of Polymyxin-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii with Phosphoethanolamine-Modified Lipid A and Lipopolysaccharide Loss Display Different Atomic-Scale Interactions with Polymyxins. ACS Infect Dis. 2020, 6, 2698–2708. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang Z, He W, Jiao M, Yu Q, Guo Y, Refat M, et al. Mechanistic and biophysical characterization of polymyxin resistance response regulator PmrA in Acinetobacter baumannii. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Aurosree B, Gopalakrishnan B, Balada-Llasat J-M, Pancholi V, Pancholi P. The role of LpxA/C/D and pmrA/B gene systems in colistin-resistant clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Frontiers in Laboratory Medicine. 2017, 1, 86–91. [CrossRef]

- Moffatt JH, Harper M, Harrison P, Hale JDF, Vinogradov E, Seemann T, et al. Colistin Resistance in <i>Acinetobacter baumannii</i> Is Mediated by Complete Loss of Lipopolysaccharide Production. 2010, 54, 4971–4977. [CrossRef]

- Hameed F, Khan MA, Muhammad H, Sarwar T, Bilal H, Rehman TU. Plasmid-mediated mcr-1 gene in Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: first report from Pakistan. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2019, 52:e20190237. [CrossRef]

- Novović K, Jovčić B. Colistin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: Molecular Mechanisms and Epidemiology. 2023, 12, 516.

- Sabnis A, Hagart KLH, Klöckner A, Becce M, Evans LE, Furniss RCD, et al. Colistin kills bacteria by targeting lipopolysaccharide in the cytoplasmic membrane. eLife. 2021, 10:e65836. [CrossRef]

- Papazachariou A, Tziolos R-N, Karakonstantis S, Ioannou P, Samonis G, Kofteridis DP. Treatment Strategies of Colistin Resistance Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. 2024, 13, 423.

- Roberts JL, Cattoz B, Schweins R, Beck K, Thomas DW, Griffiths PC, et al. In Vitro Evaluation of the Interaction of Dextrin-Colistin Conjugates with Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide. J Med Chem. 2016, 59, 647–654. [CrossRef]

- Gadar K, de Dios R, Kadeřábková N, Prescott TAK, Mavridou DAI, McCarthy RR. Disrupting iron homeostasis can potentiate colistin activity and overcome colistin resistance mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Communications biology. 2023, 6, 937. [CrossRef]

- Pournaras S, Poulou A, Dafopoulou K, Chabane YN, Kristo I, Makris D, et al. Growth retardation, reduced invasiveness, and impaired colistin-mediated cell death associated with colistin resistance development in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2014, 58, 828–832. [CrossRef]

- Saleh NM, Hesham MS, Amin MA, Samir Mohamed R. Acquisition of Colistin Resistance Links Cell Membrane Thickness Alteration with a Point Mutation in the lpxD Gene in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2020, 9(4). [CrossRef]

- Möller A-M, Vázquez-Hernández M, Kutscher B, Brysch R, Brückner S, Marino EC, et al. Common and varied molecular responses of Escherichia coli to five different inhibitors of the lipopolysaccharide biosynthetic enzyme LpxC. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2024, 300(4). [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Guitián M, Vázquez-Ucha JC, Álvarez-Fraga L, Conde-Pérez K, Bou G, Poza M, et al. Antisense inhibition of lpxB gene expression in Acinetobacter baumannii by peptide-PNA conjugates and synergy with colistin. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2020, 75, 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Quinn PJ, Yan A. Kdo2 -lipid A: structural diversity and impact on immunopharmacology. Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 2015, 90, 408–427. [CrossRef]

- Moffatt JH, Harper M, Harrison P, Hale JD, Vinogradov E, Seemann T, et al. Colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii is mediated by complete loss of lipopolysaccharide production. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2010, 54, 4971–4977. [CrossRef]

- Moffatt JH, Harper M, Adler B, Nation RL, Li J, Boyce JD. Insertion sequence ISAba11 is involved in colistin resistance and loss of lipopolysaccharide in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2011, 55, 3022–3024. [CrossRef]

- Cafiso V, Stracquadanio S, Lo Verde F, Gabriele G, Mezzatesta ML, Caio C, et al. Colistin Resistant A. baumannii: Genomic and Transcriptomic Traits Acquired Under Colistin Therapy. 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Kim S-H, Yun S, Park W. Constitutive Phenotypic Modification of Lipid A in Clinical Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates. 2022, 10, e01295–22. [CrossRef]

- Gerson S, Betts JW, Lucaßen K, Nodari CS, Wille J, Josten M, et al. Investigation of Novel pmrB and eptA Mutations in Isogenic Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates Associated with Colistin Resistance and Increased Virulence In Vivo. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2019, 63(3). [CrossRef]

- Sun B, Liu H, Jiang Y, Shao L, Yang S, Chen D, et al. New Mutations Involved in Colistin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. mSphere. 2020, 5(2). [CrossRef]

- Yamada N, Kamoshida G, Shiraishi T, Yamaguchi D, Matsuoka M, Yamauchi R, et al. PmrAB, the two-component system of <i>Acinetobacter baumannii</i>, controls the phosphoethanolamine modification of lipooligosaccharide in response to metal ions. 2024, 206, e00435–23. [CrossRef]

- Hua J, Jia X, Zhang L, Li Y. The Characterization of Two-Component System PmrA/PmrB in Cronobacter sakazakii. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kato A, Chen HD, Latifi T, Groisman EA. Reciprocal control between a bacterium's regulatory system and the modification status of its lipopolysaccharide. Molecular cell. 2012, 47, 897–908. [CrossRef]

- Adams MD, Nickel GC, Bajaksouzian S, Lavender H, Murthy AR, Jacobs MR, et al. Resistance to Colistin in <i>Acinetobacter baumannii</i> Associated with Mutations in the PmrAB Two-Component System. 2009, 53, 3628–3634. [CrossRef]

- Trebosc V, Gartenmann S, Tötzl M, Lucchini V, Schellhorn B, Pieren M, et al. Dissecting Colistin Resistance Mechanisms in Extensively Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Clinical Isolates. mBio. 2019, 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Yang Y-S, Jeng W-Y, Lee Y-T, Hsu C-J, Chou Y-C, Kuo S-C, et al. Ser253Leu substitution in PmrB contributes to colistin resistance in clinical Acinetobacter nosocomialis. Emerging microbes & infections. 2021, 10, 1873–1880. [CrossRef]

- Sun B, Liu H, Jiang Y, Shao L, Yang S, Chen D. New Mutations Involved in Colistin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. mSphere. 2020, 5(2). [CrossRef]

- Karakonstantis, S. A systematic review of implications, mechanisms, and stability of in vivo emergent resistance to colistin and tigecycline in Acinetobacter baumannii. Journal of Chemotherapy. 2020, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano V, Marascio N, Pavia G, Lamberti AG, Quirino A, Musarella R, et al. Identification of pmrB mutations as putative mechanism for colistin resistance in A. baumannii strains isolated after in vivo colistin exposure. Microbial pathogenesis. 2020, 142:104058. [CrossRef]

- Adams MD, Nickel GC, Bajaksouzian S, Lavender H, Murthy AR, Jacobs MR, et al. Resistance to colistin in Acinetobacter baumannii associated with mutations in the PmrAB two-component system. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2009, 53, 3628–3634. [CrossRef]

- Nurtop E, Bayındır Bilman F, Menekse S, Kurt Azap O, Gönen M, Ergonul O, et al. Promoters of Colistin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. Microbial drug resistance (Larchmont, NY). 2019, 25, 997–1002. [CrossRef]

- Haeili M, Kafshdouz M, Feizabadi MM. Molecular Mechanisms of Colistin Resistance Among Pandrug-Resistant Isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii with High Case-Fatality Rate in Intensive Care Unit Patients. Microbial drug resistance (Larchmont, NY). 2018, 24, 1271–1276. [CrossRef]

- Palethorpe S, Milton ME, Pesci EC, Cavanagh J. Structure of the Acinetobacter baumannii PmrA receiver domain and insights into clinical mutants affecting DNA binding and promoting colistin resistance. Journal of biochemistry. 2022, 170, 787–800. [CrossRef]

- Chin C-Y, Gregg KA, Napier BA, Ernst RK, Weiss DS. A PmrB-Regulated Deacetylase Required for Lipid A Modification and Polymyxin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. 2015, 59, 7911–7914. [CrossRef]

- Pelletier MR, Casella LG, Jones JW, Adams MD, Zurawski DV, Hazlett KR, et al. Unique structural modifications are present in the lipopolysaccharide from colistin-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013, 57, 4831–4840. [CrossRef]

- Zafer MM, Hussein AFA, Al-Agamy MH, Radwan HH, Hamed SM. Retained colistin susceptibility in clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolates with multiple mutations in pmrCAB and lpxACD operons. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2023, 13:1229473. [CrossRef]

- Beceiro A, Llobet E, Aranda J, Bengoechea JA, Doumith M, Hornsey M, et al. Phosphoethanolamine modification of lipid A in colistin-resistant variants of Acinetobacter baumannii mediated by the pmrAB two-component regulatory system. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2011, 55, 3370–3379. [CrossRef]

- Trebosc V, Gartenmann S, Tötzl M, Lucchini V, Schellhorn B, Pieren M, et al. Dissecting Colistin Resistance Mechanisms in Extensively Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Clinical Isolates. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Potron A, Vuillemenot J-B, Puja H, Triponney P, Bour M, Valot B, et al. ISAba1-dependent overexpression of eptA in clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii resistant to colistin. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2019, 74, 2544–2550. [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar S, Swetha RG, Bakthavatchalam YD, Vasudevan K, Abirami Shankar B, Kirubananthan A, et al. Genomic investigation unveils colistin resistance mechanism in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. Microbiology Spectrum. 2024, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Palmieri M, D’Andrea MM, Pelegrin AC, Perrot N, Mirande C, Blanc B, et al. Abundance of Colistin-Resistant, OXA-23- and ArmA-Producing Acinetobacter baumannii Belonging to International Clone 2 in Greece. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lesho E, Yoon EJ, McGann P, Snesrud E, Kwak Y, Milillo M, et al. Emergence of colistin-resistance in extremely drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii containing a novel pmrCAB operon during colistin therapy of wound infections. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013, 208, 1142–1151. [CrossRef]

- Deveson Lucas D, Crane B, Wright A, Han ML, Moffatt J, Bulach D, et al. Emergence of High-Level Colistin Resistance in an Acinetobacter baumannii Clinical Isolate Mediated by Inactivation of the Global Regulator H-NS. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2018, 62(7). [CrossRef]

- Gaballa A, Wiedmann M, Carroll LM. More than mcr: canonical plasmid- and transposon-encoded mobilized colistin resistance genes represent a subset of phosphoethanolamine transferases. 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Stojanoski V, Sankaran B, Prasad BVV, Poirel L, Nordmann P, Palzkill T. Structure of the catalytic domain of the colistin resistance enzyme MCR-1. BMC Biology. 2016, 14, 81. [CrossRef]

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2016, 16, 161–168. [CrossRef]

- Hussein NH, Al-Kadmy IMS, Taha BM, Hussein JD. Mobilized colistin resistance (mcr) genes from 1 to 10: a comprehensive review. Molecular biology reports. 2021, 48, 2897–2907. [CrossRef]

- Calero-Cáceres W, Rodríguez K, Medina A, Medina J, Ortuño-Gutiérrez N, Sunyoto T, et al. Genomic insights of mcr-1 harboring Escherichia coli by geographical region and a One-Health perspective. Frontiers in microbiology. 2022, 13:1032753. [CrossRef]

- Lei C-W, Zhang Y, Wang Y-T, Wang H-N. Detection of Mobile Colistin Resistance Gene <i>mcr-10.1</i> in a Conjugative Plasmid from <i>Enterobacter roggenkampii</i> of Chicken Origin in China. 2020, 64. [CrossRef]

- Göpel L, Prenger-Berninghoff E, Wolf SA, Semmler T, Bauerfeind R, Ewers C. Occurrence of Mobile Colistin Resistance Genes mcr-1–mcr-10 including Novel mcr Gene Variants in Different Pathotypes of Porcine Escherichia coli Isolates Collected in Germany from 2000 to 2021. 2024, 4, 70–84.

- Zhang J, Chen L, Wang J, Yassin AK, Butaye P, Kelly P, et al. Molecular detection of colistin resistance genes (mcr-1, mcr-2 and mcr-3) in nasal/oropharyngeal and anal/cloacal swabs from pigs and poultry. Scientific Reports. 2018, 8, 3705. [CrossRef]

- Rahman M, Ahmed S. Prevalence of colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in clinical Isolates Acinetobacter Baumannii from India. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020, 101:81. [CrossRef]

- Seleim SM, Mostafa MS, Ouda NH, Shash RY. The role of pmrCAB genes in colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 20951. [CrossRef]

- Fan R, Li C, Duan R, Qin S, Liang J, Xiao M, et al. Retrospective Screening and Analysis of mcr-1 and blaNDM in Gram-Negative Bacteria in China, 2010–2019. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kareem, SM. Emergence of mcr- and fosA3-mediated colistin and fosfomycin resistance among carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Iraq. Meta Gene. 2020, 25:100708. [CrossRef]

- Martins-Sorenson N, Snesrud E, Xavier DE, Cacci LC, Iavarone AT, McGann P, et al. A novel plasmid-encoded mcr-4.3 gene in a colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strain. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2020, 75, 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Ma F, Shen C, Zheng X, Liu Y, Chen H, Zhong L, et al. Identification of a Novel Plasmid Carrying <i>mcr-4.3</i> in an <i>Acinetobacter baumannii</i> Strain in China. 2019, 63. [CrossRef]

- Bitar I, Medvecky M, Gelbicova T, Jakubu V, Hrabak J, Zemlickova H, et al. Complete Nucleotide Sequences of mcr-4.3-Carrying Plasmids in Acinetobacter baumannii Sequence Type 345 of Human and Food Origin from the Czech Republic, the First Case in Europe. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2019, 63. [CrossRef]

- Lin MF, Lin YY, Lan CY. Contribution of EmrAB efflux pumps to colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Journal of microbiology (Seoul, Korea). 2017, 55, 130–136. [CrossRef]

- Boinett CJ, Cain AK, Hawkey J, Do Hoang NT, Khanh NNT, Thanh DP, et al. Clinical and laboratory-induced colistin-resistance mechanisms in Acinetobacter baumannii. Microbial genomics. 2019, 5(2). [CrossRef]

- Cheah SE, Johnson MD, Zhu Y, Tsuji BT, Forrest A, Bulitta JB, et al. Polymyxin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: Genetic Mutations and Transcriptomic Changes in Response to Clinically Relevant Dosage Regimens. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 26233. [CrossRef]

- Ni W, Li Y, Guan J, Zhao J, Cui J, Wang R, et al. Effects of Efflux Pump Inhibitors on Colistin Resistance in Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2016, 60, 3215–3218. [CrossRef]

- Osei Sekyere J, Amoako DG. Carbonyl Cyanide m-Chlorophenylhydrazine (CCCP) Reverses Resistance to Colistin, but Not to Carbapenems and Tigecycline in Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Thi Khanh Nhu N, Riordan DW, Do Hoang Nhu T, Thanh DP, Thwaites G, Huong Lan NP, et al. The induction and identification of novel Colistin resistance mutations in Acinetobacter baumannii and their implications. Scientific Reports. 2016, 6, 28291. [CrossRef]

- Paul D, Mallick S, Das S, Saha S, Ghosh AK, Mandal SM. Colistin Induced Assortment of Antimicrobial Resistance in a Clinical Isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii SD01. Infectious disorders drug targets. 2020, 20, 501–505. [CrossRef]

- Catel-Ferreira M, Marti S, Guillon L, Jara L, Coadou G, Molle V, et al. The outer membrane porin OmpW of Acinetobacter baumannii is involved in iron uptake and colistin binding. 2016, 590, 224–231. [CrossRef]

- Parra-Millán R, Vila-Farrés X, Ayerbe-Algaba R, Varese M, Sánchez-Encinales V, Bayó N, et al. Synergistic activity of an OmpA inhibitor and colistin against colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanistic analysis and in vivo efficacy. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2018, 73, 3405–3412. [CrossRef]

- Hood MI, Becker KW, Roux CM, Dunman PM, Skaar EP. genetic determinants of intrinsic colistin tolerance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Infection and immunity. 2013, 81, 542–551. [CrossRef]

- Levin BR, Berryhill BA, Gil-Gil T, Manuel JA, Smith AP, Choby JE, et al. Theoretical considerations and empirical predictions of the pharmaco- and population dynamics of heteroresistance. 2024, 121, e2318600121. [CrossRef]

- Band VI, Weiss DS. Heteroresistance to beta-lactam antibiotics may often be a stage in the progression to antibiotic resistance. PLoS biology. 2021, 19, e3001346. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Rayner CR, Nation RL, Owen RJ, Spelman D, Tan KE, et al. Heteroresistance to colistin in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2006, 50, 2946–2950. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, DI. The biological cost of mutational antibiotic resistance: any practical conclusions? Current opinion in microbiology. 2006, 9, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beceiro A, Moreno A, Fernández N, Vallejo JA, Aranda J, Adler B, et al. Biological cost of different mechanisms of colistin resistance and their impact on virulence in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2014, 58, 518–526. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva GJ, Domingues S. Interplay between Colistin Resistance, Virulence and Fitness in Acinetobacter baumannii. 2017, 6, 28.

- Jones CL, Singh SS, Alamneh Y, Casella LG, Ernst RK, Lesho EP, et al. <i>In Vivo</i> Fitness Adaptations of Colistin-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates to Oxidative Stress. 2017, 61, 10–1128. [CrossRef]

- Oh MH, Shin WS, Mahbub NU, Islam MM. Phage-encoded depolymerases as a strategy for combating multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Bertani B, Ruiz N. Function and Biogenesis of Lipopolysaccharides. EcoSal Plus. 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- García-Quintanilla M, Carretero-Ledesma M, Moreno-Martínez P, Martín-Peña R, Pachón J, McConnell MJ. Lipopolysaccharide loss produces partial colistin dependence and collateral sensitivity to azithromycin, rifampicin and vancomycin in Acinetobacter baumannii. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2015, 46, 696–702. [CrossRef]

- Carretero-Ledesma M, García-Quintanilla M, Martín-Peña R, Pulido MR, Pachón J, McConnell MJ. Phenotypic changes associated with Colistin resistance due to Lipopolysaccharide loss in Acinetobacter baumannii. Virulence. 2018, 9, 930–942. [CrossRef]

- Kamoshida G, Akaji T, Takemoto N, Suzuki Y, Sato Y, Kai D, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-Deficient Acinetobacter baumannii Due to Colistin Resistance Is Killed by Neutrophil-Produced Lysozyme. Frontiers in microbiology. 2020, 11:573. [CrossRef]

- Rolain J-M, Roch A, Castanier M, Papazian L, Raoult D. Acinetobacter baumannii Resistant to Colistin With Impaired Virulence: A Case Report From France. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011, 204, 1146–1147. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Nation RL, Owen RJ, Wong S, Spelman D, Franklin C. Antibiograms of Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Acinetobacter baumannii: Promising Therapeutic Options for Treatment of Infection with Colistin-Resistant Strains. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007, 45, 594–598. [CrossRef]

- Hraiech S, Roch A, Lepidi H, Atieh T, Audoly G, Rolain JM, et al. Impaired virulence and fitness of a colistin-resistant clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii in a rat model of pneumonia. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013, 57, 5120–5121. [CrossRef]

- López-Rojas R, Jiménez-Mejías ME, Lepe JA, Pachón J. Acinetobacter baumannii Resistant to Colistin Alters Its Antibiotic Resistance Profile: A Case Report From Spain. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011, 204, 1147–1148. [CrossRef]

- López-Rojas R, McConnell MJ, Jiménez-Mejías ME, Domínguez-Herrera J, Fernández-Cuenca F, Pachón J. Colistin resistance in a clinical Acinetobacter baumannii strain appearing after colistin treatment: effect on virulence and bacterial fitness. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013, 57, 4587–4589. [CrossRef]

- Dafopoulou K, Xavier BB, Hotterbeekx A, Janssens L, Lammens C, Dé E, et al. Colistin-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Clinical Strains with Deficient Biofilm Formation. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2015, 60, 1892–1895. [CrossRef]

- Farshadzadeh Z, Taheri B, Rahimi S, Shoja S, Pourhajibagher M, Haghighi MA, et al. Growth Rate and Biofilm Formation Ability of Clinical and Laboratory-Evolved Colistin-Resistant Strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Frontiers in microbiology. 2018, 9:153. [CrossRef]

- Mu X, Wang N, Li X, Shi K, Zhou Z, Yu Y, et al. The Effect of Colistin Resistance-Associated Mutations on the Fitness of Acinetobacter baumannii. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Gupta J, Palmore TN, Murray PR, Segre JA. Genomic insights into the fate of colistin resistance and Acinetobacter baumannii during patient treatment. Genome research. 2013, 23, 1155–1162. [CrossRef]

- Durante-Mangoni E, Del Franco M, Andini R, Bernardo M, Giannouli M, Zarrilli R. Emergence of colistin resistance without loss of fitness and virulence after prolonged colistin administration in a patient with extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2015, 82, 222–226. [CrossRef]

- Dahdouh E, Gómez-Gil R, Sanz S, González-Zorn B, Daoud Z, Mingorance J, et al. A novel mutation in pmrB mediates colistin resistance during therapy of Acinetobacter baumannii. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2017, 49, 727–733. [CrossRef]

- Gogry FA, Siddiqui MT, Sultan I, Haq QMR. Current Update on Intrinsic and Acquired Colistin Resistance Mechanisms in Bacteria. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Thadtapong N, Chaturongakul S, Soodvilai S, Dubbs P. Colistin and Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Aci46 in Thailand: Genome Analysis and Antibiotic Resistance Profiling. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2021, 10(9). [CrossRef]

- Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, Mathers AJ, van Duin D, Clancy CJ. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Saelim W, Changpradub D, Thunyaharn S, Juntanawiwat P, Nulsopapon P, Santimaleeworagun W. Colistin plus Sulbactam or Fosfomycin against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Improved Efficacy or Decreased Risk of Nephrotoxicity? Infect Chemother. 2021, 53, 128–140.

- Kashyap S, Kaur S, Sharma P, Capalash N. Combination of colistin and tobramycin inhibits persistence of Acinetobacter baumannii by membrane hyperpolarization and down-regulation of efflux pumps. Microbes and Infection. 2021, 23, 104795. [CrossRef]

- Xie M, Chen K, Chan EW, Chen S. Synergistic Antimicrobial Effect of Colistin in Combination with Econazole against Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Its Persisters. Microbiol Spectr. 2022, 10, e0093722. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Feng H, He L, Zhang H, Xu P. In Vitro Activities of Tigecycline in Combination with Amikacin or Colistin Against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2021, 193, 3867–3876. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Mutakabbir JC, Yim J, Nguyen L, Maassen PT, Stamper K, Shiekh Z, et al. In Vitro Synergy of Colistin in Combination with Meropenem or Tigecycline against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. 2021, 10, 880.

- Müderris T, Dursun Manyaslı G, Sezak N, Kaya S, Demirdal T, Gül Yurtsever S. In-vitro evaluation of different antimicrobial combinations with and without colistin against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. European Journal of Medical Research. 2024, 29, 331. [CrossRef]

- Ju YG, Lee HJ, Yim HS, Lee M-G, Sohn JW, Yoon YK. In vitro synergistic antimicrobial activity of a combination of meropenem, colistin, tigecycline, rifampin, and ceftolozane/tazobactam against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Scientific Reports. 2022, 12, 7541. [CrossRef]

- Zhu S, Song C, Zhang J, Diao S, Heinrichs TM, Martins FS, et al. Effects of amikacin, polymyxin-B, and sulbactam combination on the pharmacodynamic indices of mutant selection against multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Shafiee F, Naji Esfahani SS, Hakamifard A, Soltani R. In vitro synergistic effect of colistin and ampicillin/sulbactam with several antibiotics against clinical strains of multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2021, 39, 358–362. [CrossRef]

- Ungthammakhun C, Vasikasin V, Changpradub D. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Colistin Combined with Sulbactam: 9 g per Day versus 12 g per Day in the Treatment of Extensively Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Pneumonia: An Interim Analysis. 2022, 11, 1112.

- Liang W, Liu XF, Huang J, Zhu DM, Li J, Zhang J. Activities of colistin- and minocycline-based combinations against extensive drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from intensive care unit patients. BMC infectious diseases. 2011, 11:109. [CrossRef]

- Ozger HS, Cuhadar T, Yildiz SS, Demirbas Gulmez Z, Dizbay M, Guzel Tunccan O, et al. In vitro activity of eravacycline in combination with colistin against carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates. The Journal of Antibiotics. 2019, 72, 600–604. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Z, Shao Z, Lu L, Tang S, Shi K, Gong F, et al. Ceftazidime/avibactam combined with colistin: a novel attempt to treat carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli infection. BMC infectious diseases. 2023, 23, 709. [CrossRef]

- Nepka M, Perivolioti E, Kraniotaki E, Politi L, Tsakris A, Pournaras S. In Vitro Bactericidal Activity of Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole Alone and in Combination with Colistin against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Clinical Isolates. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2016, 60, 6903–6906. [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, MM. Synergistic activities of colistin combined with other antimicrobial agents against colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0270908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirijatuphat R, Thamlikitkul V. Preliminary Study of Colistin versus Colistin plus Fosfomycin for Treatment of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. 2014, 58, 5598–5601. [CrossRef]

- Phee LM, Betts JW, Bharathan B, Wareham DW. Colistin and Fusidic Acid, a Novel Potent Synergistic Combination for Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. 2015, 59, 4544–4550. [CrossRef]

- Stabile M, Esposito A, Iula VD, Guaragna A, De Gregorio E. PYED-1 Overcomes Colistin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland). 2023, 12(11). [CrossRef]

- Gontijo AVL, Pereira SL, de Lacerda Bonfante H. Can Drug Repurposing be Effective Against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii? Curr Microbiol. 2021, 79, 13. [CrossRef]

- Peyclit L, Baron SA, Rolain JM. Drug Repurposing to Fight Colistin and Carbapenem-Resistant Bacteria. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2019, 9:193. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Artificial intelligence for drug repurposing against infectious diseases. Artificial Intelligence Chemistry. 2024, 2, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayerbe-Algaba R, Gil-Marqués ML, Jiménez-Mejías ME, Sánchez-Encinales V, Parra-Millán R, Pachón-Ibáñez ME, et al. Synergistic Activity of Niclosamide in Combination With Colistin Against Colistin-Susceptible and Colistin-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae. 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Domalaon R, De Silva PM, Kumar A, Zhanel GG, Schweizer F. The Anthelmintic Drug Niclosamide Synergizes with Colistin and Reverses Colistin Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacilli. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2019, 63. [CrossRef]

- Tran TB, Cheah S-E, Yu HH, Bergen PJ, Nation RL, Creek DJ, et al. Anthelmintic closantel enhances bacterial killing of polymyxin B against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. The Journal of Antibiotics. 2016, 69, 415–421. [CrossRef]

- Ayerbe-Algaba R, Gil-Marqués ML, Miró-Canturri A, Parra-Millán R, Pachón-Ibáñez ME, Jiménez-Mejías ME, et al. The anthelmintic oxyclozanide restores the activity of colistin against colistin-resistant Gram-negative bacilli. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2019, 54, 507–512. [CrossRef]

- Borges KCM, Costa VAF, Neves BJ, Kipnis A, Junqueira-Kipnis AP. New antibacterial candidates against Acinetobacter baumannii discovered by in silico-driven chemogenomics repurposing. PLOS ONE. 2024, 19, e0307913. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Muñiz MY, López-Jacome LE, Hernández-Durán M, Franco-Cendejas R, Licona-Limón P, Ramos-Balderas JL, et al. Repurposing the anticancer drug mitomycin C for the treatment of persistent Acinetobacter baumannii infections. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2017, 49, 88–92. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y-S, Sun W, Xu M, Shen M, Khraiwesh M, Sciotti RJ, et al. Repurposing Screen Identifies Unconventional Drugs With Activity Against Multidrug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Espejo S, Vila-Domínguez A, Cebrero-Cangueiro T, Smani Y, Pachón J, Jiménez-Mejías ME, et al. Efficacy of Tamoxifen Metabolites in Combination with Colistin and Tigecycline in Experimental Murine Models of Escherichia coli and Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Russo TA, Umland TC, Deng X, El Mazouni F, Kokkonda S, Olson R, et al. Repurposed dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors with efficacy against drug-resistant <i>Acinetobacter baumannii</i>. 2022, 119, e2213116119. [CrossRef]

- Moghadam MT, Mojtahedi A, Moghaddam MM, Fasihi-Ramandi M, Mirnejad R. Rescuing humanity by antimicrobial peptides against colistin-resistant bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 3879–3893. [CrossRef]

- Mwangi J, Hao X, Lai R, Zhang ZY. Antimicrobial peptides: new hope in the war against multidrug resistance. Zoological research. 2019, 40, 488–505. [CrossRef]

- Sacco F, Bitossi C, Casciaro B, Loffredo MR, Fabiano G, Torrini L, et al. The Antimicrobial Peptide Esc(1-21) Synergizes with Colistin in Inhibiting the Growth and in Killing Multidrug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Strains. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2022, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Vila-Farres X, Garcia de la Maria C, López-Rojas R, Pachón J, Giralt E, Vila J. In vitro activity of several antimicrobial peptides against colistin-susceptible and colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012, 18, 383–387. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan D, Roy N, Kulkarni O, Nanajkar N, Datey A, Ravichandran S, et al. Ω76: A designed antimicrobial peptide to combat carbapenem- and tigecycline-resistant <i>Acinetobacter baumannii</i>. 2019, 5, eaax1946. [CrossRef]

- Mohan NM, Zorgani A, Jalowicki G, Kerr A, Khaldi N, Martins M. Unlocking NuriPep 1653 From Common Pea Protein: A Potent Antimicrobial Peptide to Tackle a Pan-Drug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Wang Y, Wu Z, Mao C, Li L, Cao H, et al. Antimicrobial Peptide Cec4 Eradicates Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in vitro and in vivo. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2023, 17, 977–992. [CrossRef]

- Ji F, Tian G, Shang D, Jiang F. Antimicrobial peptide 2K4L disrupts the membrane of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and protects mice against sepsis. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch R, Wiesner J, Marker A, Pfeifer Y, Bauer A, Hammann PE, et al. Profiling antimicrobial peptides from the medical maggot Lucilia sericata as potential antibiotics for MDR Gram-negative bacteria. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2018, 74, 96–107. [CrossRef]

- Hetta HF, Ramadan YN, Al-Harbi AI, E AA, Battah B, Abd Ellah NH, et al. Nanotechnology as a Promising Approach to Combat Multidrug Resistant Bacteria: A Comprehensive Review and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kumar D, Singhal C, Yadav M, Joshi P, Patra P, Tanwar S, et al. Colistin potentiation in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii by a non-cytotoxic guanidine derivative of silver. 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Khaled JM, Alharbi NS, Siddiqi MZ, Alobaidi AS, Nauman K, Alahmedi S, et al. A synergic action of colistin, imipenem, and silver nanoparticles against pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from patients. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2021, 14, 1679–1685. [CrossRef]

- Ušjak D, Novović K, Filipić B, Kojić M, Filipović N, Stevanović MM, et al. In vitro colistin susceptibility of pandrug-resistant Ac. baumannii is restored in the presence of selenium nanoparticles. J Appl Microbiol. 2022, 133, 1197–1206. [CrossRef]

- Youf R, Müller M, Balasini A, Thétiot F, Müller M, Hascoët A, et al. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy: Latest Developments with a Focus on Combinatory Strategies. 2021, 13, 1995.

- Boluki E, Kazemian H, Peeridogaheh H, Alikhani MY, Shahabi S, Beytollahi L, et al. Antimicrobial activity of photodynamic therapy in combination with colistin against a pan-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from burn patient. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy. 2017, 18:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Boluki E, Moradi M, Azar PS, Fekrazad R, Pourhajibagher M, Bahador A. The effect of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy against virulence genes expression in colistin-resistance Acinetobacter baumannii. Laser therapy. 2019, 28, 27–33. [CrossRef]

- Pourhajibagher M, Kazemian H, Chiniforush N, Bahador A. Evaluation of photodynamic therapy effect along with colistin on pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Laser therapy. 2017, 26, 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Yang J, Sun X, Li M, Zhang P, Zhu Z, et al. CRISPR-Cas in Acinetobacter baumannii Contributes to Antibiotic Susceptibility by Targeting Endogenous AbaI. Microbiol Spectr. 2022, 10, e0082922. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, He D, Li B, Guo Y, Wang W, Luo X, et al. Eliminating mcr-1-harbouring plasmids in clinical isolates using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2019, 74, 2559–2565. [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader K, Gutiérrez D, Grimon D, Ruas-Madiedo P, Lood C, Lavigne R, et al. Lysin LysMK34 of <i>Acinetobacter baumannii</i> Bacteriophage PMK34 Has a Turgor Pressure-Dependent Intrinsic Antibacterial Activity and Reverts Colistin Resistance. 2020, 86, e01311–20. [CrossRef]

- Wintachai P, Phaonakrop N, Roytrakul S, Naknaen A, Pomwised R, Voravuthikunchai SP, et al. Enhanced antibacterial effect of a novel Friunavirus phage vWU2001 in combination with colistin against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Scientific Reports. 2022, 12, 2633. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi S, Sisakhtpour B, Mirzaei A, Karbasizadeh V, Moghim S. Efficacy of isolated bacteriophage against biofilm embedded colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Gene Reports. 2021, 22, 100984. [CrossRef]

- Schooley RT, Biswas B, Gill JJ, Hernandez-Morales A, Lancaster J, Lessor L, et al. Development and Use of Personalized Bacteriophage-Based Therapeutic Cocktails To Treat a Patient with a Disseminated Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. 2017, 61. [CrossRef]

- Helekal D, Keeling M, Grad YH, Didelot X. Estimating the fitness cost and benefit of antimicrobial resistance from pathogen genomic data. 2023, 20, 20230074. [CrossRef]

- Oyejobi GK, Olaniyan SO, Yusuf N-A, Ojewande DA, Awopetu MJ, Oyeniran GO, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii: More ways to die. Microbiological Research. 2022, 261, 127069. [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Yao Z, Kong J, Tang M, Liu Q, Zhang X, et al. Antiparasitic nitazoxanide potentiates colistin against colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli in vitro and in vivo. Microbiol Spectr. 2024, 12, e0229523. [CrossRef]

- Minrovic BM, Jung D, Melander RJ, Melander C. New Class of Adjuvants Enables Lower Dosing of Colistin Against Acinetobacter baumannii. ACS Infect Dis. 2018, 4, 1368–1376. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Liu Y, Feng L, Xu M, Wen H, Yao Z, et al. In vitro and in vivo synergistic effect of chrysin in combination with colistin against Acinetobacter baumannii. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kaur A, Sharma P, Capalash N. Curcumin alleviates persistence of Acinetobacter baumannii against colistin. Scientific Reports. 2018, 8, 11029. [CrossRef]

- Thadtapong N, Chaturongakul S, Napaswad C, Dubbs P, Soodvilai S. Enhancing effect of natural adjuvant, panduratin A, on antibacterial activity of colistin against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Scientific Reports. 2024, 14, 9863. [CrossRef]

- Koller BH, Jania LA, Li H, Barker WT, Melander RJ, Melander C. Adjuvants restore colistin sensitivity in mouse models of highly colistin-resistant isolates, limiting bacterial proliferation and dissemination. 2024, 68, e00671–24. [CrossRef]

- Feng X, Liu S, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Sun L, Li H, et al. Synergistic Activity of Colistin Combined With Auranofin Against Colistin-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Ucha JC, Martínez-Guitián M, Lasarte-Monterrubio C, Conde-Pérez K, Arca-Suárez J, Álvarez-Fraga L, et al. Syzygium aromaticum (clove) and Thymus zygis (thyme) essential oils increase susceptibility to colistin in the nosocomial pathogens Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2020, 130:110606. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Cai J, Shi J, Wang Z, Liu Y. Resensitizing multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria to carbapenems and colistin using disulfiram. Communications biology. 2023, 6, 810. [CrossRef]

- Guo T, Li M, Sun X, Wang Y, Yang L, Jiao H, et al. Synergistic Activity of Capsaicin and Colistin Against Colistin-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii : In Vitro/Vivo Efficacy and Mode of Action. Front Pharmacol. 2021. [CrossRef]

| Compounds | Subjects | Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaempferol | Galleria mellonella | Disruption of iron homeostasis and fenton reaction leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species. | [22] |

| Nitazoxanide | Galleria mellonella | Inhibit biofilm | [163] |

| 2-aminoimidazole | Galleria mellonella | [164] | |

| Chrysin | Galleria mellonella/ Mouse | Damage extracellular membrane and modify bacterial membrane potential | [165] |

| Curcumin | In-vitro | Increase ROS and function as efflux pump inhibitor | [166] |

| AOA-2 | Mouse | OmpA inhibitor, significantly decrease the bacterial cell load in tissues and blood, and increased mouse survival rate | [80] |

| Panduratin A | In vitro | Inhibit biofilm formation | [167] |

| IMD-0354 | Mouse | Inhibit lipid A modification | [168] |

| NMD-27 | Mouse | [168] | |

| Auranofin | Mouse | Inhibition of MCR | [169] |

| Essential oils of clove and thyme | In vitro | Increase cell membrane permeability | [170] |

| Disulfiram | Mouse | Damage bacterial membrane and disrupt metabolism | [171] |

| Capsaicin | Mouse | Inhibit the biofilm formation, Disrupt outer membrane, Inhibition of protein synthesis and efflux pumps activity | [172] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).