1. Introduction

Thin film growth in PLD (Pulse Laser Deposition) is produced as a result of the plasma formed when radiation from a pulsed laser interacts with the surface of a solid. These films are used in a variety of applications, such as the selective removal of material using lasers to create the desired geometry on a given substrate [

1], the electron source components on a laser-micromachining silicon chip using pulsed laser ablation [

2], laser processing to improve smart materials for various industries, enabling precise changes in material properties and customization of surface characteristics [

3] and, in particular, keeping the production capacity of YBa

2Cu

3O

7-δ (YBCO) thin films with excellent properties allow them to be used in manufacturing low-temperature high-performance electronic devices [

4,

5,

6]. Nevertheless, its applicability in micro and nanothecnologies is limited mainly because of two factors: splashing, that is, expulsion of particles and fragments of material from the target during ablation and their subsequent collision with film Surface [

7], promoting particles, "clusters" or inclusions during their growth.

Both factors modify film surface morphology during its growth. How these factors arise depends on the nature of the interaction of the laser radiation with the target material that is influenced by: oxygen pressure [

8], deposition temperatura [

9], laser power density, pulse duration, energy wavelength, and also thermodynamic and optical properties of the solid, which in turn, delimits the pen dynamics [

10]. The first three laser factors are adjusted to establish a thermodynamic environment between the target and the substrate that favors film growth. There are, however, thermal effects that modify both target and film surface morphology during film growth.

Apart from ebullition and evaporation of the target material, one of the most important thermal effects is phase explosión [

11], also called explosive ebullition, in which a superheated metastable liquid undergoes an explosive liquid-vapor phase transition into a stable two-phase state due to massive homogenous nucleation of vapor bubbles. The morphological characteristics of the target surface, as well as those of the grown film, such as roughness, porosity, wettability, and capillarity, can be controlled by laser parameters, besides physical properties, such as hardness, crystallinity, heat-transfer performance [

12], and liquid-absorption capacity. This control is feasible because, during ablation, the processes of fusion and evaporationdo not depend on the hardness of the material and they can be controlled by the laser parameters [

13]. Other parameters to be taken into account to establish a thermodynamic environment during ablation of the target material are: temperaturea, optical absorption, vapor pressure, and texture [

12].

Since all parameters are interrelated: those related to the laser radiation and those of target and substrate material, the phenomenology associated with PLD-film growth is complex, so the appropriate choice of parameter values to define with certainty physical properties of interest, such as film rugosity or electric conductivity is difficult. It is possible, however, to find a range of values applying methodologies based on statistically-supported techniques [

14] to the thermal effects associated with target-laser interaction [

11], to reduce spattering, “clusters”, and inclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

YBCO (1-2-3) superconducting stoichiometric targets were prepared at the Signal Processing and Sensors Laboratory of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Azcapotzałco using classical ceramic technology. The target was mounted on a fixed bracket inside a vacuum chamber. YBCO films were deposited on 99.9% purity electrolytic copper substrates using an Nd:YAG laser with , a fluence, a 5 pulse duration (), and a frequency of 10 Hz. For a fixed and frontal position of the laser with respect to the target, the image of the laser beam (“spot” of the laser) focused with a convex lens (). on the surface of the target was experimentally adjusted to a round shape 2 mm in diameter. The deposit time was five minutes. A 3 model distance between the target and the substrate ) was selected due to its proven experimental results. Growth temperature (substrate temperature) was °C. O2 pressure ) during film growth in the ablation chamber was . The incidence angle of the laser beam was adjusted to 30° with respect to the substrate surface normal vector. For all experiments, laser fluence, spot magnitude, oxygen pressure, growth temperature, growth time, and angle of incidence of the laser beam were kept fixed and stable. Once the YBCO films were obtained, they were exposed to an in situ annealing temperature of 450 °C and O2 pressure of 270 mTorr for two hours.

Microstructural observation of the surface and elemental chemical analysis were made in a SEM, LEO 440 brand with a capacity of 40 keV, adapted with a solid state detector of Si-Li with 1024 channels and range of 20 keV, OXFORD brand. Photomicrograps were obtained using an acceleration voltage of 20 keV and a current density of 200 pA, through a secondary electron detector. Chemical analysis was obtained through an X-ray diffraction applying energy dispersion (EDS), electrostatic dispersion, point analyzes were made with an acceleration voltage of 20 keV and current density 1 nA, the acquisition time of each spectrum was 60 s, in real time. All the elements that generate X-rays were detected from beryllium. The calculation of the semi-quantification was made using correction factor ZAF (effect of the atomic number, absorption and flourescence of the processed sample) and the results were normalized.

3. Results

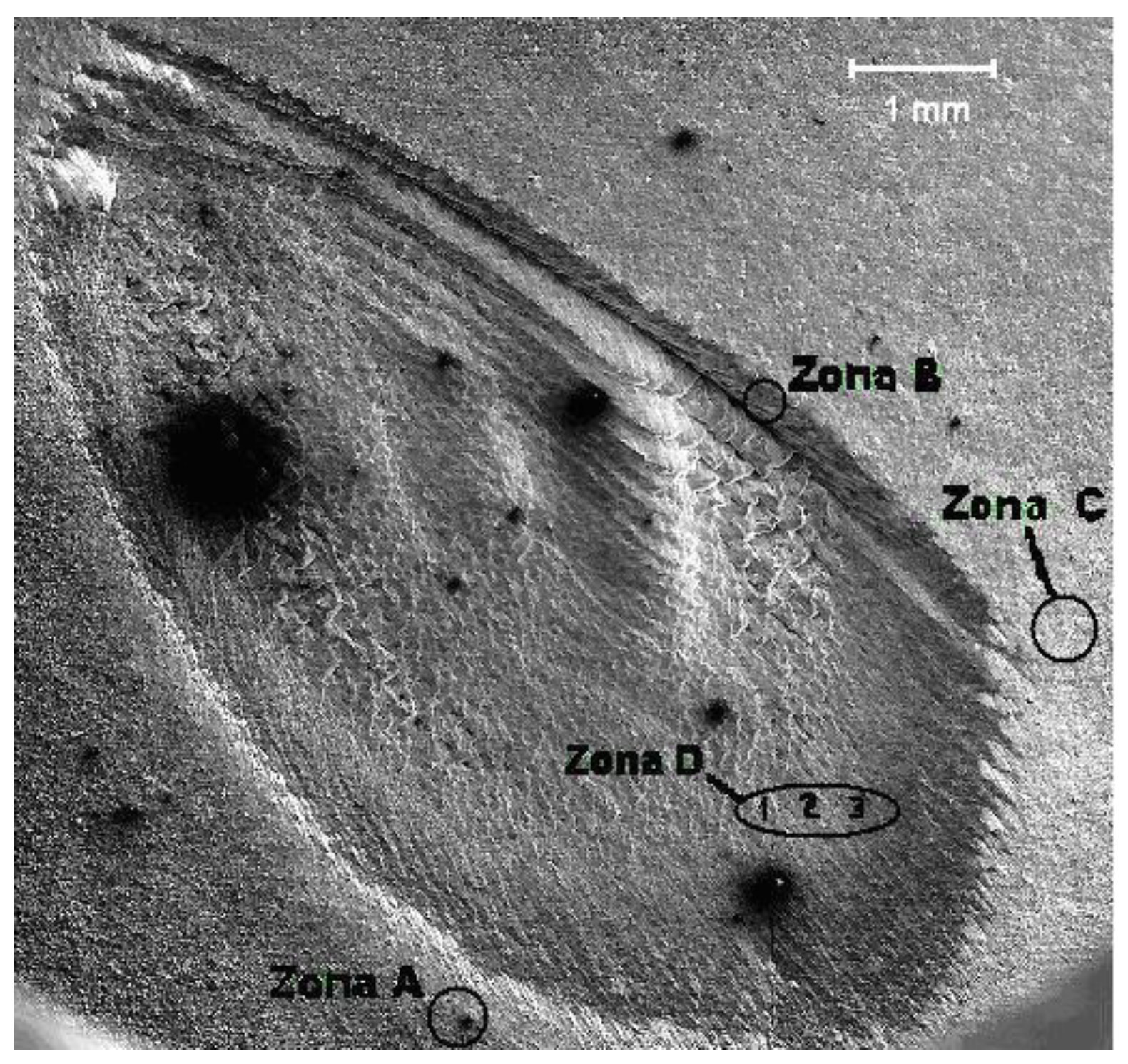

The image obtained by SEM shows different regions and structures in the area where the laser beam impacted the target surface and outside it. In

Figure 1, several of these regions have been selected for study, classified as zone A, B, C, and D. Image shows that tha crater, poduced by ablation, has an oval shape and in some of its regions has surface roughness with scale-like and terrace type formations.

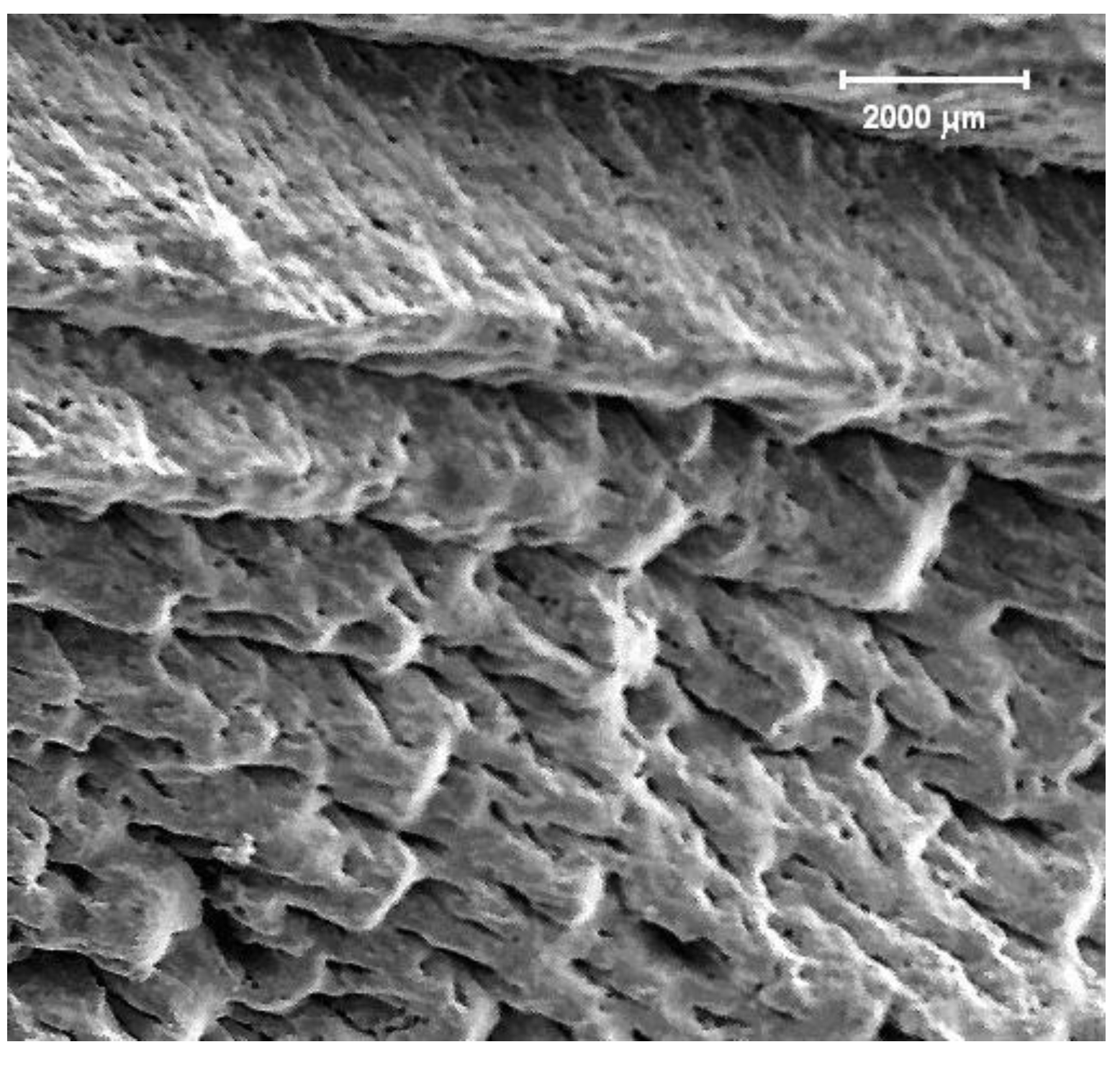

Figure 2 shows Zone B, the region located at the ablated edge (bevel), with a surface morphology typical of a fusion-resolidification process. ”Terraces” are observed, produced by the sonic shock wave (caused by the interaction between the laser beam photons and the target solid Surface [

7] when the material was not completely melted (during ablation) and had time to solidify before it ceased.

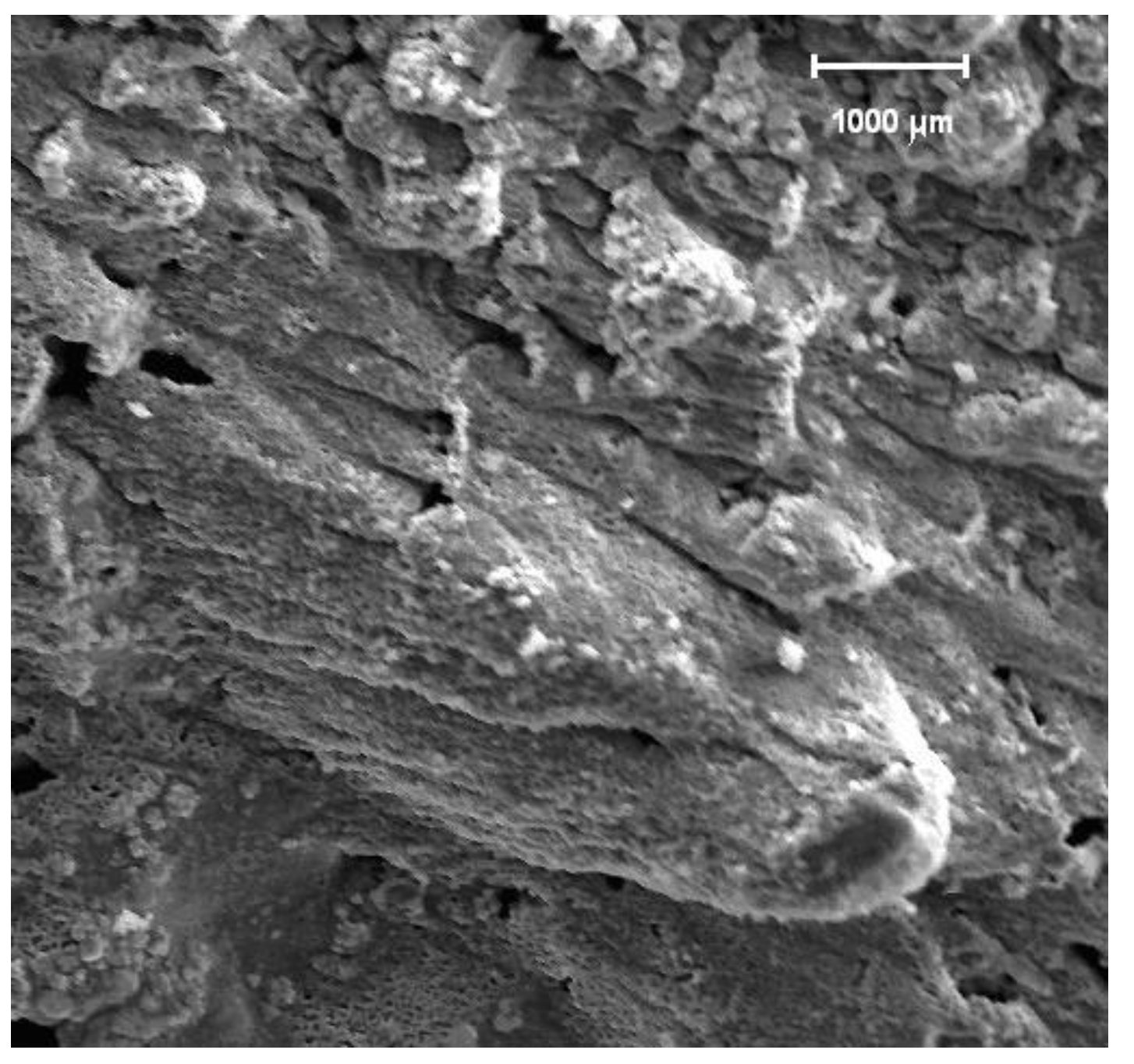

Figure 3 shows Zone A –the region immediately after the edge of the impact area. Zone A, like Zone B, shows a surface morphology in which a fusion-resolidification process also occurred. But there is a structure of cones of various sizes and zones where the cones didn't finish forming. Valleys and pores are present due to the formation of these cones.

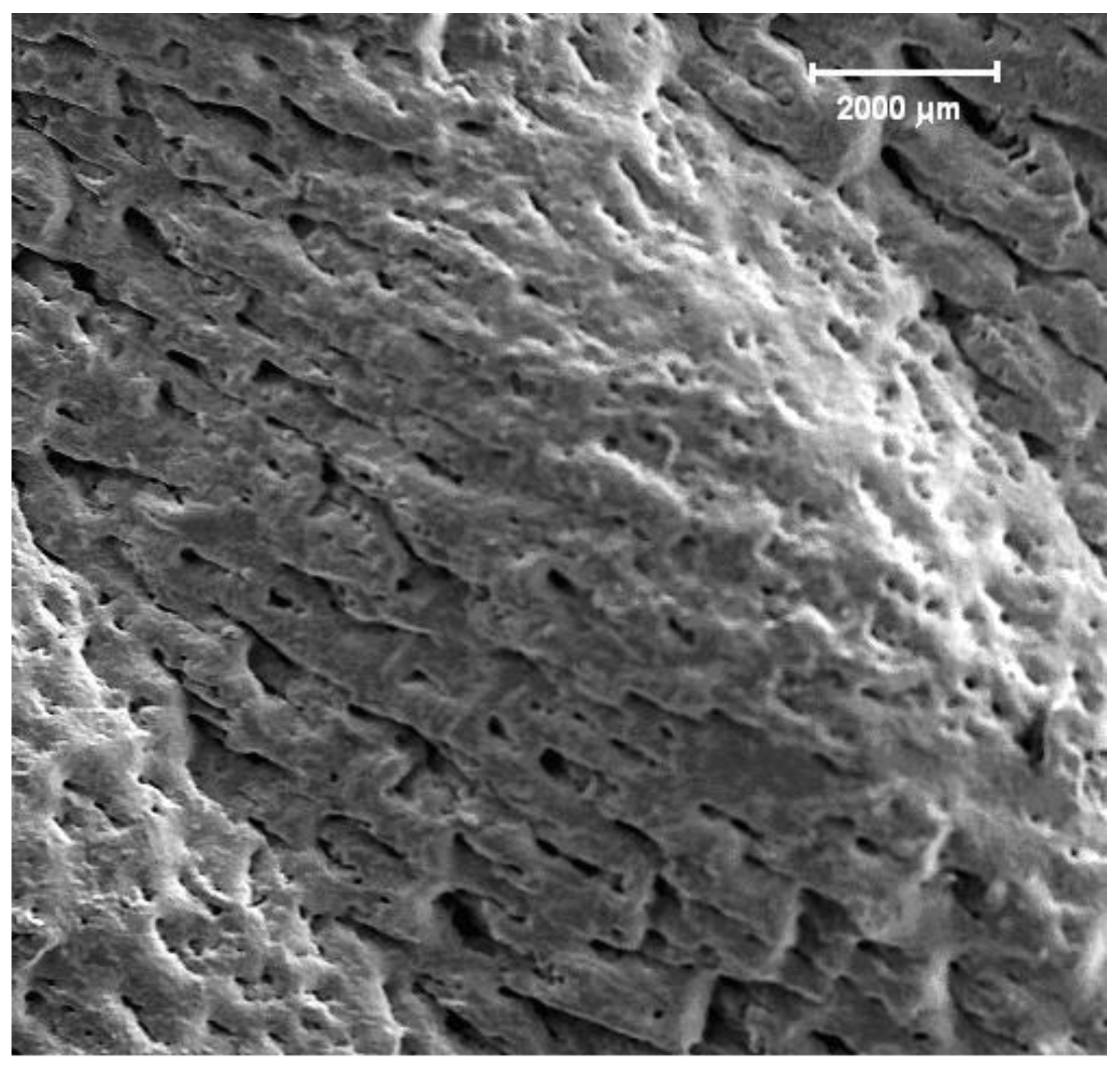

The photomicrograph in

Figure 4 shows the amplification of Zone B. The surface morphology, like in

Figure 3, reveals a fusion-resolidification process that formed a pattern of “scales" with a directional trend caused by the shock wave produced during ablation. This form of “surface melting” is caused by heat flowing away from the ablation area. It is likely that the discrepancy between the morphologies of Zones A and B is caused by the difference in the sonic shock wave intensities, given the relative positions between both Zones, with respect to the crater rim [

15].

Figure 5 shows a region of the target surface very close to the outer periphery of the crater –Zone C in

Figure 1. Particles of hemispherical shape are present, and their orientation reveals a preferential direction. There are also cracks on the target surface.

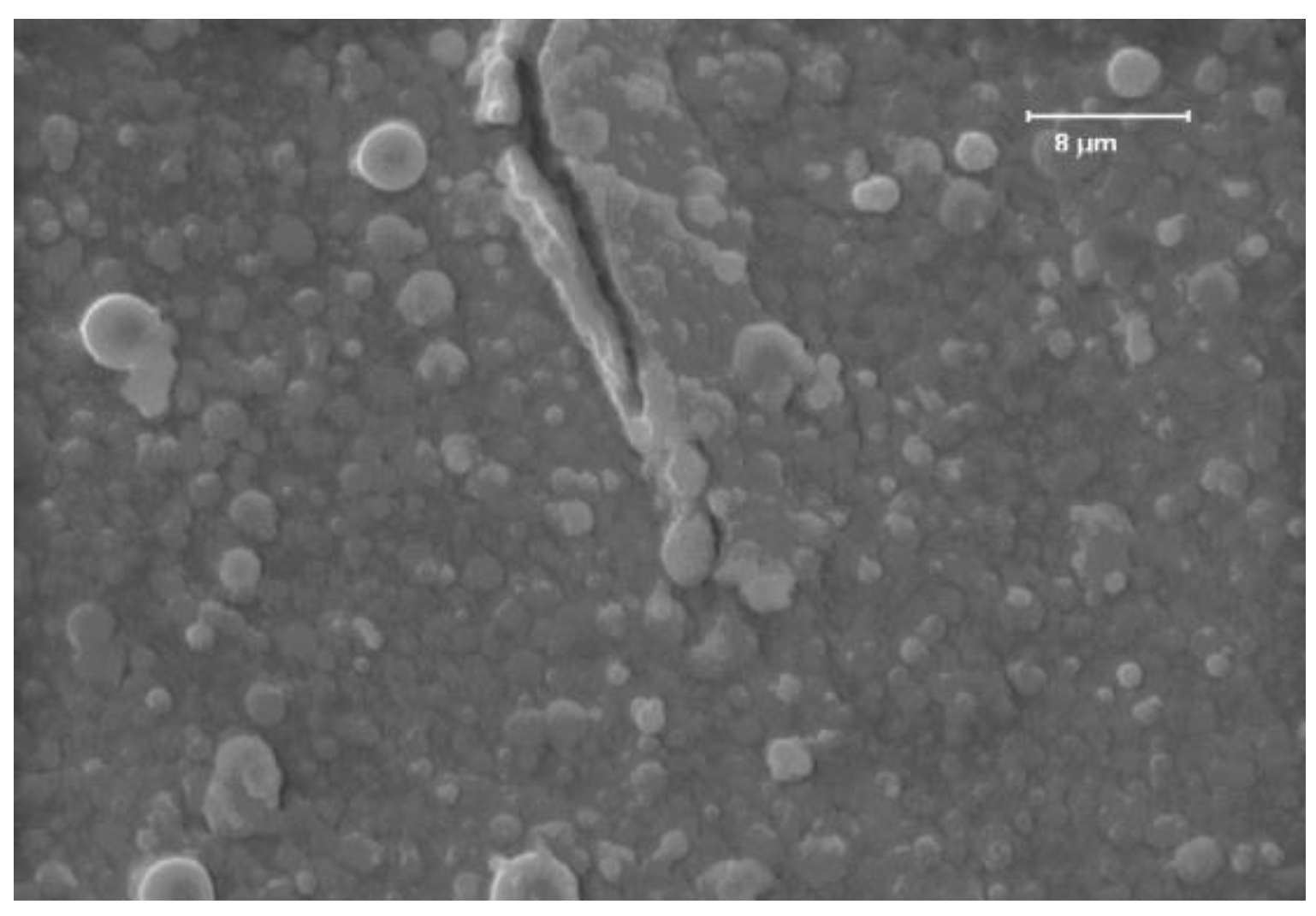

Figure 6 shows spherical-shaped particles deposited on the substrate during target laser ablation.

Figure 7 shows an inclusion of irregular shape on the surface of a YBCO film deposited by PLD with λ = 1064 nm.

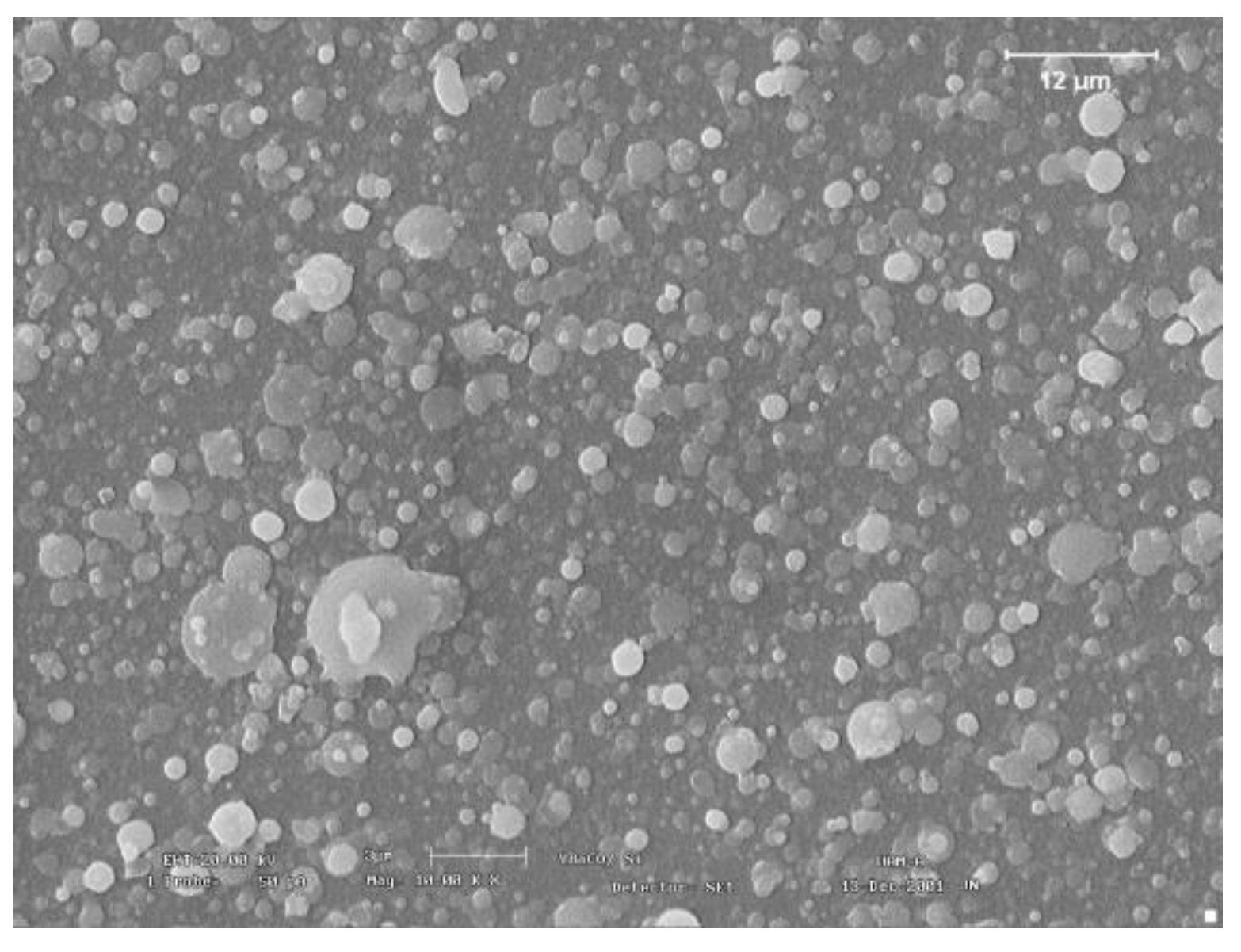

Photomicrograph of

Figure 8 shows material particles coming from the target, mainly of spherical shape, with diameters ranging in size from 0.4 to 6

μm, randomly distributed and some coated by deposit.

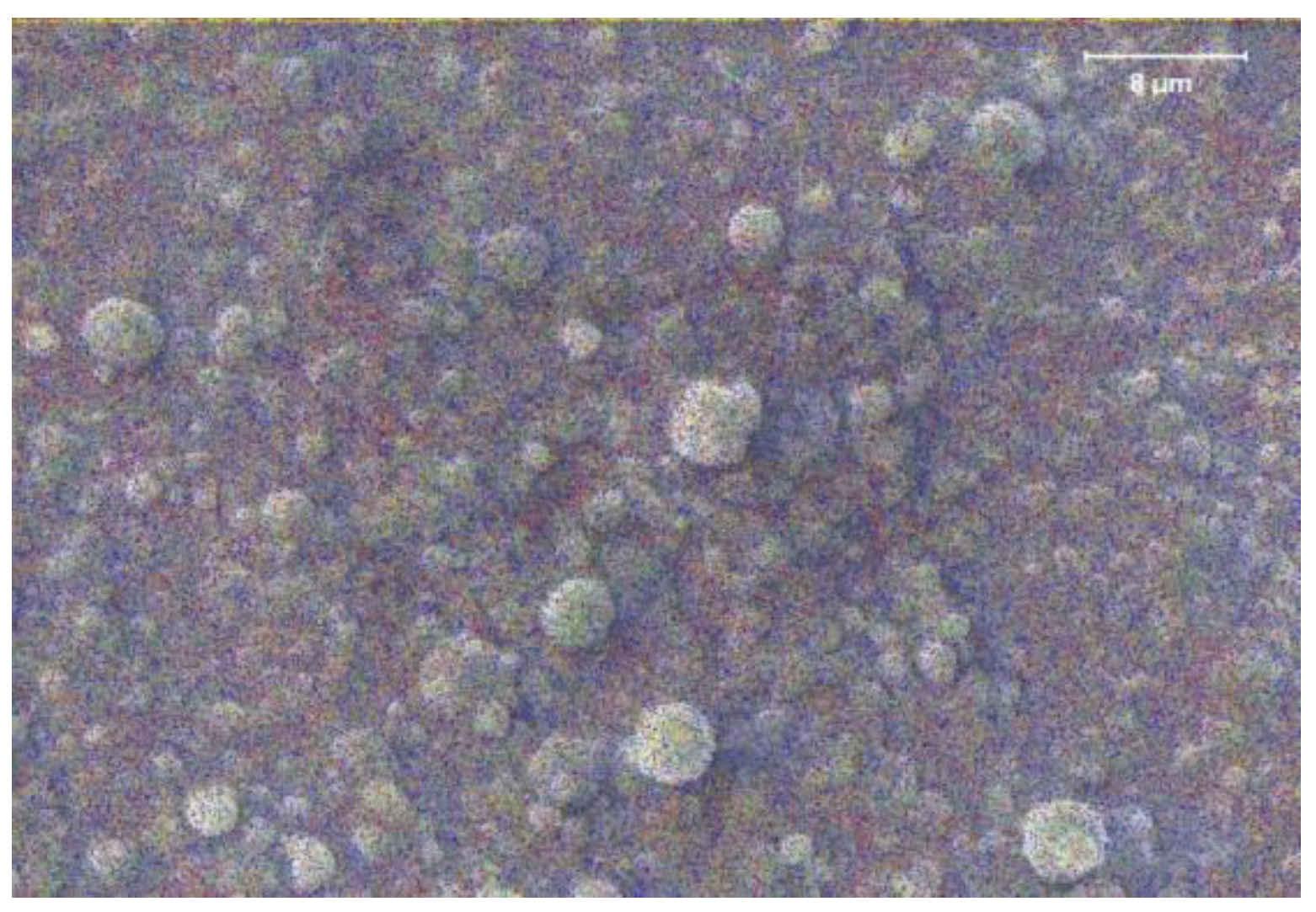

With the the LEO 440 brand SEM, the distribution of the YBCO film surface composition was qualitatively determined. The SEM uses a representation based on colored points –one color for each element: blue for Y, red for Cu, yellow for O and green for Ba. As can be seen, Cu predominates, Y follows.

Since the observed particles, both in the target and in the substrate, have random distributions, hemispherical shapes, and similar dimensions, as seen in

Figure 6 and

Figure 8, EDS analyzes were carried out to distinguish the contribution of stoichiometry in both cases and to be able to value them.

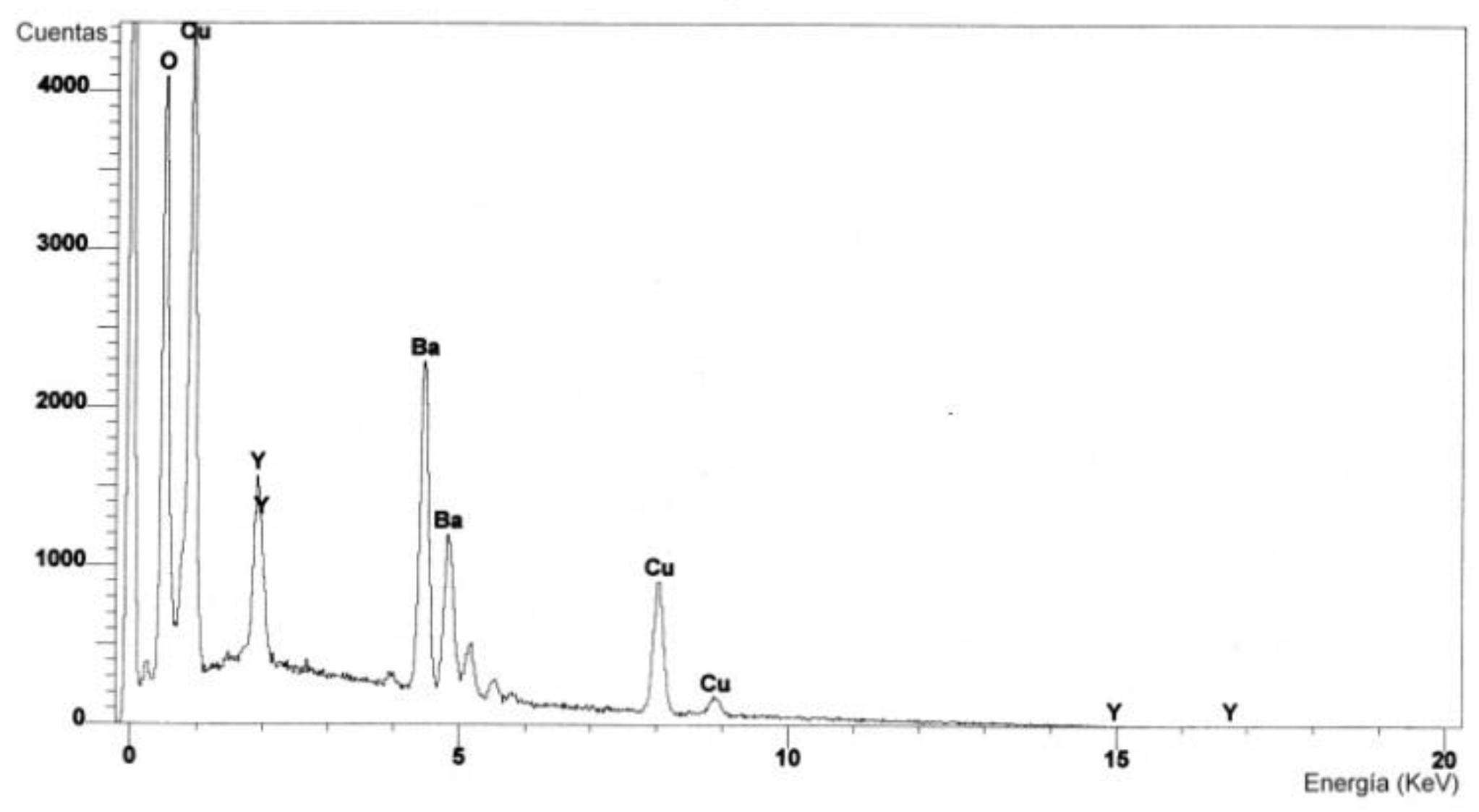

Figure 9 shows the EDS spectrum of the particles observed on the target surface, very close to the ridge of the crater –Zone C in

Figure 1. The atomic percentage composition is: 62.20% O, 18.47% Cu, 6.40% Y, 12.93% Ba.

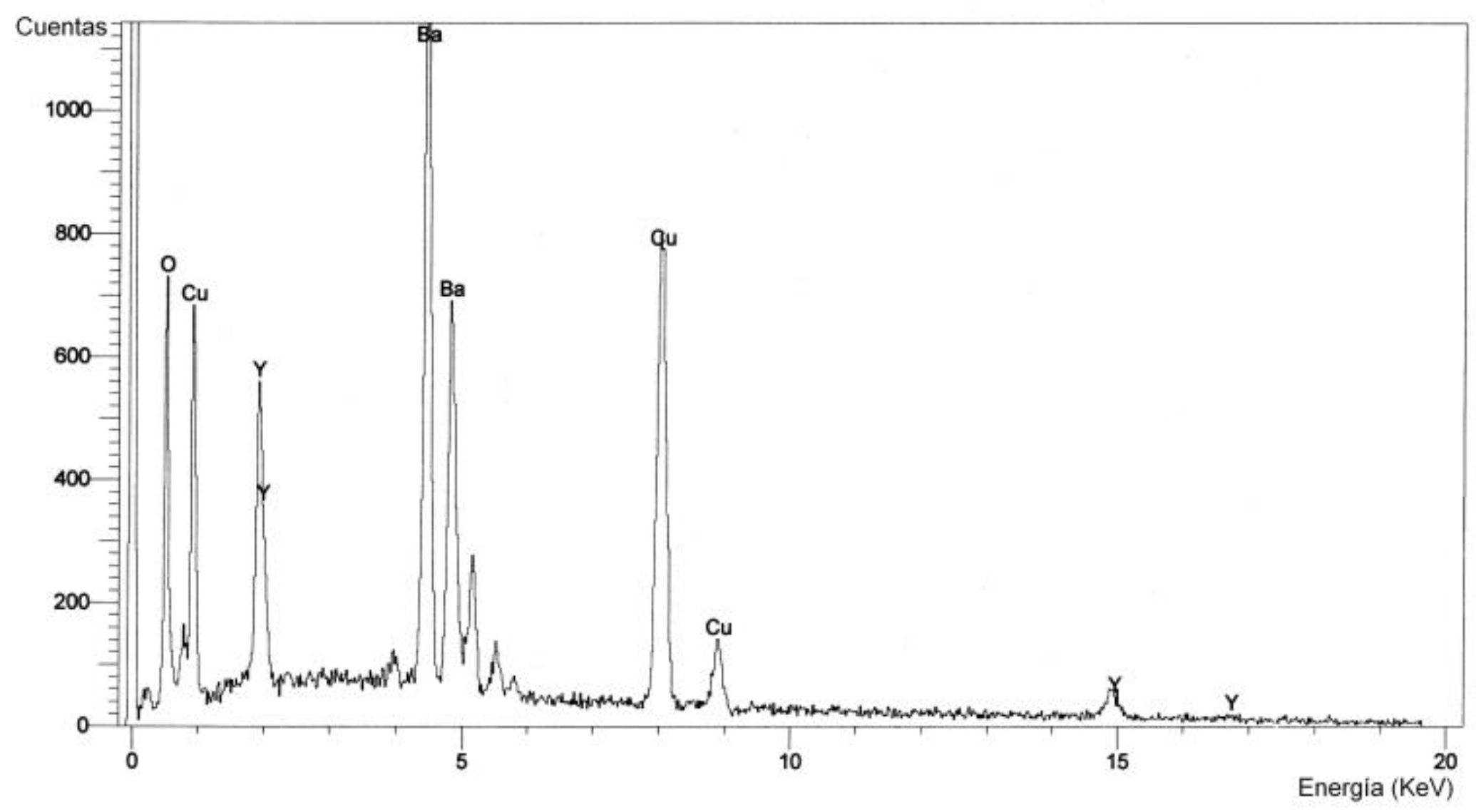

Figure 10 shows the EDS spectrum of one of the particles deposited on the YBCO film surface shown in

Figure 8. The atomic percentage composition is: 65.35% O, 18.42% Cu, 3.95% Y, 12.28% Ba.

4. Discussion

What

Figure 1 shows is the result of the interaction between the pulsed laser radiation and the target.

the expulsion and expansion of products obtained by such interaction,

interaction of the products with the substrate surface and

nucleation and growth of the film on the substrate surface.

Ablation effects on the target and film surface are related to stages (1), (2), and (3) and influence the splashing and uniformity of the deposit.

Understanding the phenomenology associated with point (1) is of utmost importance in explaining the production of the particles observed on the target and film surfaces (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). For instance, with laser pulses, the collision effects between the pen (plasm formed during ablation due to laser-substrate interaction) and the substrate surface are negligible compared with the side effects of the interaction. These secondary effects are related to thermal phenomena that depend on interaction energy since the plume may contain energetic particles from the target material. That is why, with laser pulses, the thermal effects are crucial in comprehending particle expulsion.

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show evidence of vaporization and particle expulsion under the stated conditions of fluence and pulse length, resulting from three effects: normal vaporization, normal boiling, and phase explosión [

16]. These thermal effects are called "thermal splashing" [

16] and contribute to particle expulsion.

For various experimental conditions, thermal splashing contributes energetically to substrate material ablation, for example, normal vaporization from the target surface can occur essentially with any fluence and pulse length, in addition to unimportant nucleation effects.

The second kind of thermal splashing in importance is normal boiling, because it requires the length of the pulse to be long enough to produce nucleation of heterogeneous bubbles on the target in a zone that extends from the surface to a depth related to the absorption length (1/μ, where µ is the absorption coefficient) as long as the condition that the temperature gradient at and below the surface of the target be ∂T⁄ ∂x = 0. There was evidence of sites where heterogeneous nucleation ocurred (

Figure 4). However, its effects are not predominant in boiling, meaning its density is low, probably in the order of

-1 [

8].

There is other kind of thermal splashing, besides vaporization and normal boiling, called “phase explosion”. This phenomenon is probably the main contributor to the expulsion of particles and material from the target during laser ablation. This third kind of thermal splashing requires that the laser fluence be high enough and the pulse length be short enough for the target to reach ~0.90T

tc (where T

tc is the thermodynamic critical temperature) [

11] in and below the surface of the target. If these conditions are met, homogeneous nucleation of bubbles ocurrs, and the target makes a fast transition from a superheated liquid to a mixture of vapor and drops of liquid in equilibrium. As in boiling, it can be expected that in and below the surface the condition ∂T⁄ ∂x = 0 be satisfied. Much of the historical work to understand this thermal effect was done by Martynyuk [

17,

18,

19] and Fucke and Seydel [

20], who introduced the terms phase explosion and explosive boiling. It is reasonable to asume that near T

tc homogeneous nucleation rate suddenly increases, though such nucleation does not constitute an obstacle because phase explosion predominates.

Phase explosion triggers the expulsion of particles since, under the given experimental conditions, initially, normal vaporization and normal boiling coexist simultaneously, i.e., two states of matter coexist at and below the surface. (very close, on the order of 1-2 µm), setting an average temperature (T

b). Under these conditions, the vaporized particles have only positive velocities (in directions normal to the target surface). Since the pulsed energy keeps coming, the material absorbs more energy until, after an elapsed time

∆t (of the order of ns), the Knudsen Layer (KL) is formed on the surface of the liquid [

21]. At that moment, in the region where the KL is present, negative velocities develop, but, for the total momentum to be conserved, the particles must develop a center of mass with positive velocity, producing a flow whose center of mass has positive velocity

The crux of the matter is that if normal vaporization and normal boiling happen simultaneously, just a little before the KL is formed, and the surface reaches an average temperature of a little more than TB, then heterogeneous nucleation follows. But if overheating occurs and the temperature reaches ~0.9Ttc, then phase explosion happens (explosive boiling) by homogenous nucleation. As a result, the hot region near the surface quickly becomes a mixture of vapor plus drops of liquid in equilibrium.

Based on the EDS spectra in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, the deviation in stoichiometry between the observed surface particles in the target and the grown film can be evaluated. As can be seen, the constituent elements are the same in both samples (in the target and the film), namely, O, Cu, Y, and Ba, though there are differences in their atomic percent composition.

Table 1 shows the results of the atomic percent composition for the analyzed areas in the target and the film and also the atomic percent composition difference between the two. As can be seen, the greatest difference in atomic percentage is that of Y, i.e., the composition of Y in the target is not reproduced on the grown film during laser ablation (it does not have congruent evaporation) under the experimental conditions set. One reason for this result is that the fluence is not high enough, and since the evaporation temperature of Y is the highest compared to the other oxides, then Y does not evaporate as easily.

Discrepancies between composition values of particles in the target and the film are due to the nature of the thermal splashing phenomena produced by the fluence. It is reasonable to assume that if the laser fluence is increased, or, more importantly, if the pulse width is reduced, the congruent evaporation in PLD will improve, namely, avoiding the splashing of drops and fragments, the vapor phase will predominate and therefore, making possible the systematic reproducibility of the composition of the target in the thin film, even growing multicomponent materials.

5. Conclusions

It is experimentally demonstrated that when the surface of YBCO targets with stoichiometry (123), interacts with a pulsed laser ( pulse duration) to low fluences () vapor is generated accompanied by material expulsion consisting of liquid particles and ruins coming from the target. The thermal effects that cause particle expulsion are basically due to the combination of normal vaporization, normal boiling and mainly phase explosion. At low fluences it is demonstrated that the particles are projected on the surface of the growing film and on the surface of the target too, meaning that there is a backscatter phenomenon. The composition of Y is not reproduced on the thin film, this is probably due to the low fluence, and since the evaporation temperature of Y is higher that of the other oxides, then Y does not evaporate as easily. Based on the discussion of results, for congruent evaporation to occur, the thermal effect of the normal vaporization must be increased and the normal boiling reduced as much as possible (either to reduce the liquid phase or none at all). This can be achieved either by increasing the fluence or, more interestingly, by decreasing the pulse width (ps or fs instead of ns); in this way, when phase explosion occurs, the vapor phase formation will be promoted and, therefore, the splashing of particles will be reduced The compositional and morphological modification of the target surface under prolonged laser irradiation can significantly influence the characteristics of the film (stoichiometry, roughness, and uniformity of the composition on the film) and must be taken into account in the practical use of PLD, for example, for the manufacture of high-performance electronic devices.

Author Contributions

Víctor Rogelio Barrales-Guadarrama performed the investigation, the experiments and wrote the manuscript, Raymundo Barrales-Guadarrama developthe conceptualization, the methodology and was responsible of writing review and Melitón Ezequiel Rodríguez-Rodríguez developed the image processing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Azcapotzalco, in Mexico City.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sundar, M.; Zhehao, J.; Alhaji, K. Droplet assisted nanosecond fibre laser micromachining. Lasers Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 9(2), 117-133.

- Langer, C.; Bomke, V.; Hausladen, M.; Ławrowski, R.; Prommesberger, C.; Bachman, M.; Schreiner, R. Silicon chip field emission electron source fabricated by laser micromachining. J. Vac. Sci. Technol.B 2020, 38(1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Murzin, S. P.; Stiglbrunner, C. Fabrication of smart materials using laser processing: analysis and prospects. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 85. [CrossRef]

- Sabbir, G.; Iyer, S.S. Ultra-high conductivity interconnects for 77K CMOS using heterogeneous integration. 2022 IEEE 72nd Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 2022, 2099-2103.

-

Umenne, P. AFM Analysis of micron and sub-micron sized bridges fabricated using the femtosecond laser on YBCO thin films. Micromachines 2020, 11(12), 1088. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wang, L. Fabrication and characterization of high-Tc YBCO DC-SQUID magnetometers with recycled SrTiO3 bi-crystal substrates using an off-axis RF magnetron sputtering technique. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2023, 33(5), 1-5.

- Kruse, C.M. et al. Enhanced pool-boiling heat transfer and critical heat flux on femtosecond laser processed stainless steel surfaces, Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 82, 109–116. [CrossRef]

- Aghabagheri,·S.; Mohammadizadeh, M. R.; Kameli,· P.; Salamati, H. Effect of oxygen pressure on the surface roughness and intergranular behavior of YBCO thin films. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2016, 29, 1483–1489.

- Tan, S.; Wang, S.; Li, S. The effect of deposition temperature on the morphology and superconductivity of YBa2Cu3O7-δ thin films. 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Electronic Information and Communication Technology (ICEICT), Qingdao, China, 2023, 1075-1077.

- Xu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, X. et al. Optimization for epitaxial fabrication of infinite-layer nickelate superconductors. Front. Phys. 2024. 19, 33209. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.; Miotello, A. Comments on explosive mechanisms of laser sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1996, 96-98, 205-215. [CrossRef]

- Udaya Kumar, G.; Suresh, S.; Sujith Kumar, C. S.; Back, S.; Kang, B.; Lee, H. A review on the role of lase textured surfaces on boiling heat transfer. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 174, 115274.

- Malinauskas, M.; Zukauskas, A.; Hasegawa, S.; Hayasaki, Y.; Mizeikis, V.; Buividas, R.; Juodkazis, S. Ultrafast laser processing of materials: from science to industry. Light Sci. Appl. 2016, 5, e16133. [CrossRef]

- Barrales-Guadarrama, V.R. Crecimiento de películas delgadas de YBaCuO por la técnica de crecimiento PLD. Tesis de Doctorado, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Av. Instituto Polítecnico Nacional 2508, San Pedro Zacatenco, Gustavo A. Madero, 07360, Ciudad de México, 2005.

- Clark, P.; Connolly, P.; Curtis, A.S.; Dow, J.A.; Wilkinson, C.D. Topographical control of cell behaviour: II. Multiple grooved substrata. Development 1990, 108(4), 635–644. [CrossRef]

- Bulgakova, N.M.; Buglgakov, A.V. Pulsed laser ablation of solids: transition from normal vaporization to phase explosion. Appl. Phys. 2001, A 73, 199–208. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Martynyuk, Sov. Phys. Tech. Phys. 1974, 19, 793.

- M.M. Martynyuk, Sov. Phys. Tech. Phys. 1976, 21, 430.

- M.M. Martynyuk, Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 1983, 57, 494.

- Seydel, U.; Fucke, W. Experimental determination of critical data of liquid molybdenum. J. Phys. F: Metal Physics 1978, 8(7), L157-L161. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.; Dreyfus, R.W. On the effect of Knudsen-layer formation on studies of vaporization, sputtering, and desorption. Surf. Sci. 1988, 198(1-2), 263-276. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).