1. Introduction

Collagen is the most abundant structural protein in animals, constituting about 30% of the total protein in mammalian bodies [

1]. It plays an essential role in maintaining the structural integrity of tissues, providing strength and flexibility to bones, tendons, skin, cartilage, and ligaments [

2]. According to San Antonio, Jacenko [

3], collagen is essential for hemostasis, wound healing, angiogenesis, and biomineralization. Conversely, when collagen is dysfunctional, it can lead to conditions such as fibrosis, atherosclerosis, cancer metastasis, and brittle bone disease [

3]. Due to its remarkable biocompatibility and bioactivity, collagen has gained significant interest for its use in various industries, particularly in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and biomedical fields [

4]. Applications range from wound healing [

5,

6], tissue engineering [

7,

8], bio fillers [

9,

10] to cosmetic products [

11] and nutraceuticals [

12]. In addition, collagen possesses important characteristics, including high tensile strength [

13], low antigenicity [

14], and excellent biocompatibility [

15]. Collagen promotes blood platelet coagulation, influences cell differentiation, and plays a role in wound healing[

16].

Traditionally, collagen has been sourced from terrestrial animals such as cows, pigs, and sheep [

17]. However, concerns regarding zoonotic disease transmission, religious restrictions, and growing awareness about sustainability and environmental impact have prompted the search for alternative collagen sources [

18]. From a health perspective, collagen source from marine such as fish scales seems not to have disease transmission [

19,

20]. Fish scales, an underutilized byproduct of the seafood industry, offer a sustainable and eco-friendly source of collagen [

21]. Fish scale-derived collagen, particularly from species like tilapia, has been found to have comparable physicochemical properties to mammalian collagen. Utilizing fish scales not only reduces waste from fish processing but also aligns with the global push toward sustainable development and the circular economy [

9]. Moreover, the by-products are low cost and the need to minimize fish industry waste’s environmental impact paved the way for the use of discards in the development of collagen-based products with remarkable added value [

20].

While fish scales offer a promising source of collagen, the extraction process poses significant challenges. For instance, collagen in fish scales is embedded within a dense matrix of calcium salts [

22], making efficient extraction difficult. Traditional methods often involve the use of strong acids or enzymes, which can degrade the collagen structure or result in low yields. Moreover, these methods can be time-consuming and expensive, limiting the industrial scalability of fish scale collagen extraction [

23,

24]. The use of Tris-Glycine buffer for collagen extraction offers an innovative alternative. Tris-Glycine is a widely used buffer in biochemical research, known for its ability to maintain a stable pH over a wide range of conditions [

25], which is crucial for preventing collagen degradation during extraction. By using Tris-Glycine, the extraction process can be more controlled, reducing the need for harsh chemicals and improving the purity and yield of the collagen obtained.

Although a vast number of studies are available on the extraction of collagen from marine sources, the optimization and the study of the effect of Tris-Glycine on the extraction of collagen from the skin of the tilapia fish is lacking. Besides, optimization of the extraction process is essential to maximize collagen yield and maintain its bioactivity [

26]. The Taguchi method, a statistical approach used for optimizing complex processes, is well-suited for this purpose. By systematically varying key factors such as buffer concentration, temperature, pH, and extraction time, the Taguchi method allows the identification of the optimal conditions with a minimal number of experiments [

27]. This approach reduces time and resource consumption while ensuring high-quality results [

28]. Several studies have successfully used the Taguchi method to optimize biochemical processes. For instance, Mokrejš, Gál [

29] optimize the processing of the MDCM by-product into gelatins using Taguchi method, achieving enhanced yield and quality of the gelatins. Taguchi design and response surface methodology (RSM) was also applied to optimise the extraction parameters, such as acetic acid concentration, hydrolysis time, and temperature [

30]. The current study is an attempt to optimize the process variables to obtain the highest collagen yield per gram of fish scales. Various factor like acetic acid concentration (M), volume of acetic acid (mL), time (hr), and Tris-Glycine buffer (mL) were optimized to achieve maximum yield of collagen. The results obtained were validated using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) focusing on dominant factors Interaction effect between the variables were studied using regression model.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Assessing the Effective of Optimized Parameters on Collagen Yield

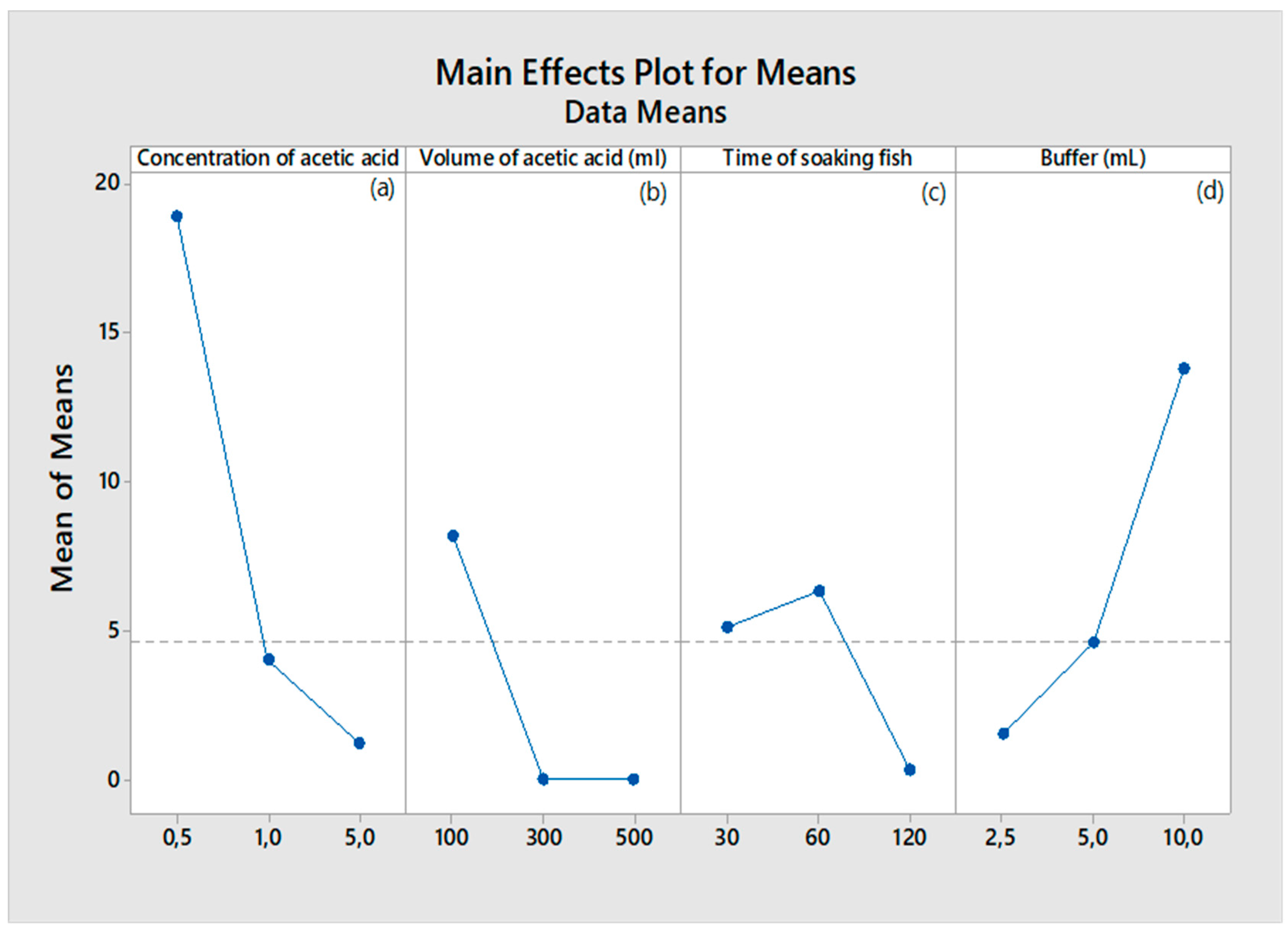

The effect of acetic acid concentration, volume of acid, time of soaking, and buffer on the extraction of collagen were studied by one variable at a time using Taguchi method.

2.1.1. Effect of Acetic Acid Concentration on Collagen Extraction

The effect of the acetic acid concentration (0.5–5.0 M) on collagen extraction was determined while keeping other three variables constant. Figure 1 (a) shows a steep decline in the mean response as the concentration of acetic acid increases from 0.5 M to 5 M. This indicates that higher acetic acid concentrations significantly reduce collagen yield. This might be due to the excessive acid degrading the collagen or affecting its solubility. This agrees with prior research showing that high concentrations of acid can degrade collagen, affecting the yield during the extraction process [

4]. Nagai and Suzuki [

31] reveal that while acetic acid is effective for demineralizing fish scales, overly high concentrations can disrupt collagen's triple-helical structure, lowering yield.

2.1.2. Effect of Volume of Acetic Acid on Collagen Extraction

The effect of the volume of acetic acid (100–500 ML) on collagen extraction was determined while keeping other three variables constant. Figure 1 (b) shows that there is a decline in the mean response as the volume of acetic acid increases from 100 mL to 500 mL, with minimal changes between 300 mL and 500 mL. This implies that larger volumes of acetic acid may not necessarily improve the demineralization or collagen extraction, potentially due to saturation effects. Kim and Mendis [

32] mention that excessive volumes of acids can dilute the reagents and lower efficiency, without increasing the extraction yield proportionately.

2.1.3. Effect of Time of Soaking on Collagen Extraction

The effect of the volume of acetic acid (60–120 minutes) on collagen extraction was determined while keeping other three variables constant. Figure 1 (c) shows an initial increase in the mean response at 60 minutes of soaking, followed by a drop at 120 minutes, implying that soaking fish scales for 60 minutes appears optimal, while prolonged soaking (120 minutes) could lead to collagen degradation.

2.1.4. Effect of Buffer Volume on Collagen Extraction

The effect of the volume of acetic acid (60–120 minutes) on collagen extraction was determined while keeping other three variables constant.

Figure 1 (d) shows an increase in the mean response with increasing buffer volume, peaking at 10 mL. The finding suggests that higher volume of Tris-Glycine buffer improves collagen yield, likely by stabilizing the pH and preventing collagen degradation during extraction. Tris-Glycine buffers are known for maintaining pH stability during protein extractions [

33], which can enhance collagen yield. Presumably, buffer solutions help stabilize the pH during extraction, ensuring that collagen remains intact, which agrees with research indicating that buffers are crucial for maintaining collagen structure during processing [

34,

35].

2.2. Experimental Factors Affecting the Extraction of Collagen

Table 1 shows the results of a Taguchi method experiment with four factors affecting the extraction of collagen. The Delta values represent the difference between the highest and lowest responses for each factor, and the Rank indicates the order of importance of the factors based on their impact on collagen yield. The concentration of acid has the largest effect on collagen extraction, as indicated by the highest delta value (17.7105). The response decreases sharply with increasing acid concentration. Therefore, lower concentrations of acid (Level 1) produce the highest collagen yield and increasing the concentration results in diminished extraction efficiency. This aligns with literature showing that while some acid is necessary to break down the matrix in fish scales, higher concentrations can degrade collagen, reducing yield [

31].

The volume of acetic acid has a moderate effect on the collagen yield. The highest yield is observed at Level 1 (100 mL), but increasing the volume beyond this point results in no significant improvement (Levels 2 and 3 show no response). This could be due to the saturation of the solution, where increasing the volume of acetic acid beyond a certain threshold provides no additional benefit to the extraction process. Soaking time has a relatively smaller impact on collagen yield compared to the acid concentration and buffer volume. The optimal time for soaking is 60 minutes (Level 2), with a slight improvement over shorter times (Level 1: 30 minutes). However, soaking for longer periods (Level 3: 120 minutes) results in a sharp decline in yield, potentially due to collagen degradation after extended exposure to acidic conditions [

36].

The buffer volume has the second-largest impact on collagen extraction, with the highest yield observed at Level 3 (10 mL). This shows that larger buffer volumes (10 mL) significantly enhance collagen yield, likely by stabilizing the pH during the extraction process, protecting the collagen from degradation. This finding is consistent with literature on buffer use in biochemical extractions, where adequate buffer volume ensures pH stability and prevents enzymatic degradation [

32,

35].

2.3. ANOVA Model for Collagen Extraction Optimization

The ANOVA value in

Table 2 provides insight into the significance of each factor affecting collagen extraction using the Taguchi method. The regression model is statistically significant with a P-value of 0.000, indicating that the factors included in the model (concentration of acetic acid, volume of acetic acid, time of soaking, and buffer) explain a significant amount of the variation in collagen yield. The high F-value (21.87) also indicates a strong overall effect of the factors on the outcome. The finding suggests that concentration of acetic acid and buffer volume are the most significant factors influencing collagen yield, as evidenced by their high F-values and very low P-values (0.001 for both). Controlling these two factors is critical for optimizing collagen extraction. On the other hand, volume of acetic acid has a moderate effect (P=0.039), while soaking time does not significantly impact collagen yield within the range tested (P>0.05). This result contradicts other previous studies which shows that time, concentration of the acid and temperature are significant parameters in the collagen yield[

26,

37]. The plausible explanation may be connected to the differences between fish scales as use in the present study and fish skins reported in the literature.

2.4. Responses Modelling.

Mathematical relationships between the responses and the studied factors are developed and presented by the following equations shown in

Table 3. The model explains a large portion of the variance in the data (R² = 73.84%), and all variables show acceptable levels of multicollinearity (VIF values). The concentration of acetic acid and buffer volume are the most significant factors affecting collagen yield, with concentration negatively affecting yield ((-1.504) and buffer volume positively affecting it (1.152). The volume of acetic acid plays a moderate role in reducing collagen yield (-0.01330, while time of soaking has an insignificant effect within the tested range (0.0127). These findings are consistent with previous studies, where optimizing acid concentration and maintaining buffer stability were crucial for maximizing collagen yield [

38].

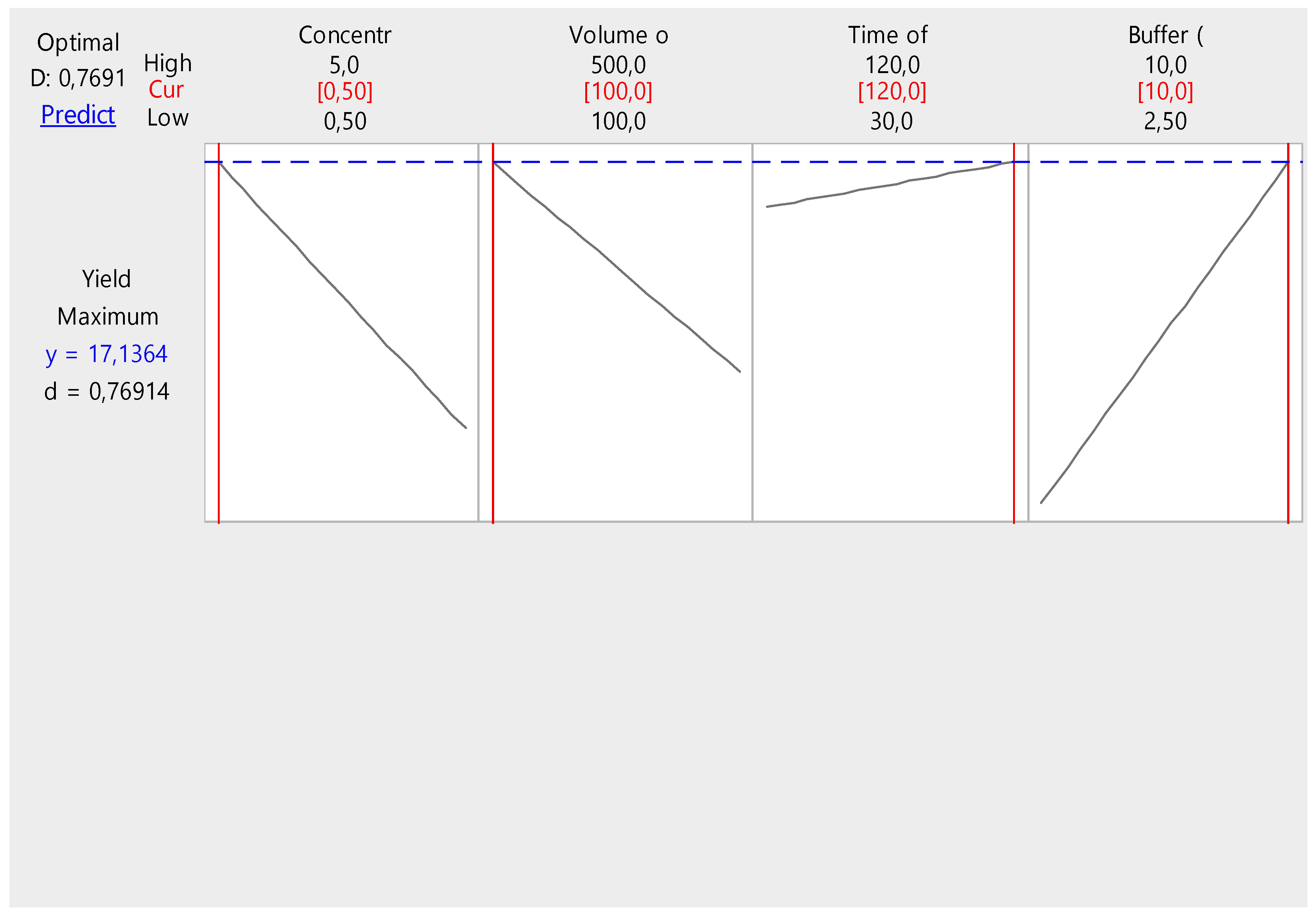

Figure 2 further provides graphical representation of an optimization process for the collagen yield experiment, where different factors (concentration of acetic acid, volume of acetic acid, time of soaking, and buffer volume) are being evaluated for their effects on the yield. The optimal factor combination for achieving the highest collagen yield is represented in the plot: Concentration of acetic acid (0.50), Volume of acetic acid (100 mL), Time of soaking (around 120 minutes), Buffer volume: Close to the high end (10 mL). This suggests that minimizing the concentration and volume of acetic acid while maximizing the buffer volume and keeping the soaking time relatively high will result in the highest collagen yield. The predicted maximum yield of 17.1364% reflects a high collagen yield for the given experimental setup

2.5. Amino Acid Quantification and Characterization

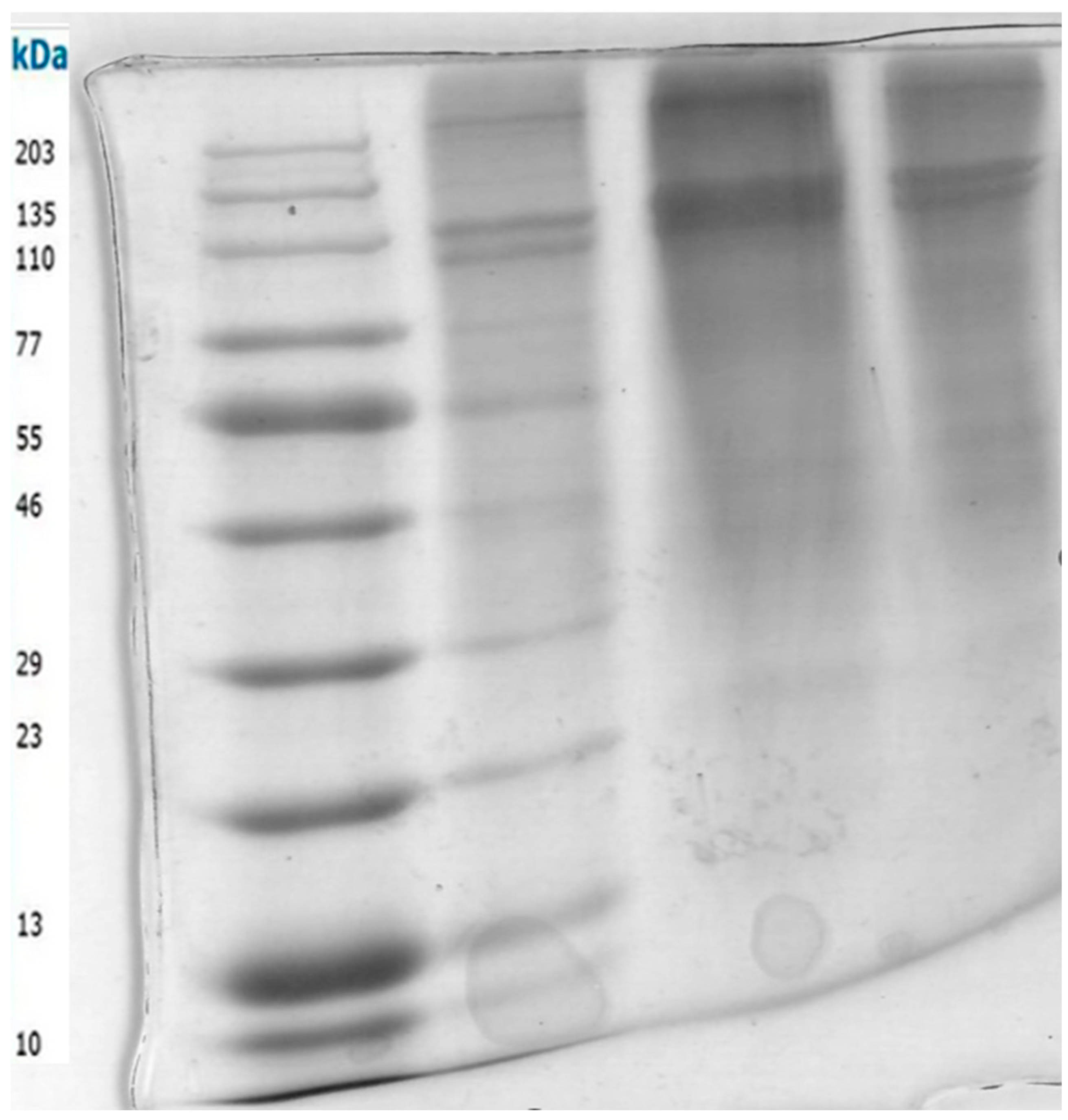

2.5.1. SDS-PAGE Characterization of Collagen

Figure 3 shows the SDS-PAGE of type I collagen extracted from marine samples. Lane 1: molecular weight marker (MW); Lanes 2-4: extracted type I collagen with different substrates. On SDS-PAGE, three bands are commonly found for collagen type I, which refers to the basic structure of monomeric alpha-1 and alpha-2 monomers, as well as the common motif of regular collagen secondary structures of the β-band and γ-band. The alpha bands of type I collagen are approximately 100-130 kDa, while the beta band is approximately 250 kDa [

39]. The β-band represents a dimer representing two alpha chains crosslinking with each other, and the γ-band represents three alpha chains, which are visible in the upper part of the gel [

40]. SDS-PAGE revealed the typical pattern for type I collagen, with bands at apparent molecular weights of 208 kDa (b), 130 kDa (a1), and 116 kDa (a2), we detected significant collagenase activity using 1. Collagen dissolved in acetic acid and 5 % SDS (Lane 1) 2. Collagen boiled in Sodium chloride at 80 °C (Lane 2) 3. Acetic acid only (Lane 3). Collagenases cleave type I collagen at specific sites in the a-chain, leading to the formation of 1/4 C-terminal and 3/4 N-terminal fragments [

41]. Amongst the detected collagenase activity, collagen boiled in sodium chloride at 80 °C (Lane 2) gave the best activity, hence, it was further purified by 80 % ammonium sulfate precipitation and ran on 10 % SDS-PAGE and gave the picture below. Collagen is the most abundant structural protein found in humans and mammals, particularly in the extracellular matrix (ECM) [

39]. Its primary function is to hold the body together. The collagen superfamily of proteins includes over 20 types that have been identified [

41]. Yet, collagen type I is the major component in many tissues. Type I collagen is commonly recognized as the gold standard biomaterial for the manufacturing of medical devices for health-care related applications. In recent years, with the final aim of developing scaffolds with optimal bioactivity [

40].

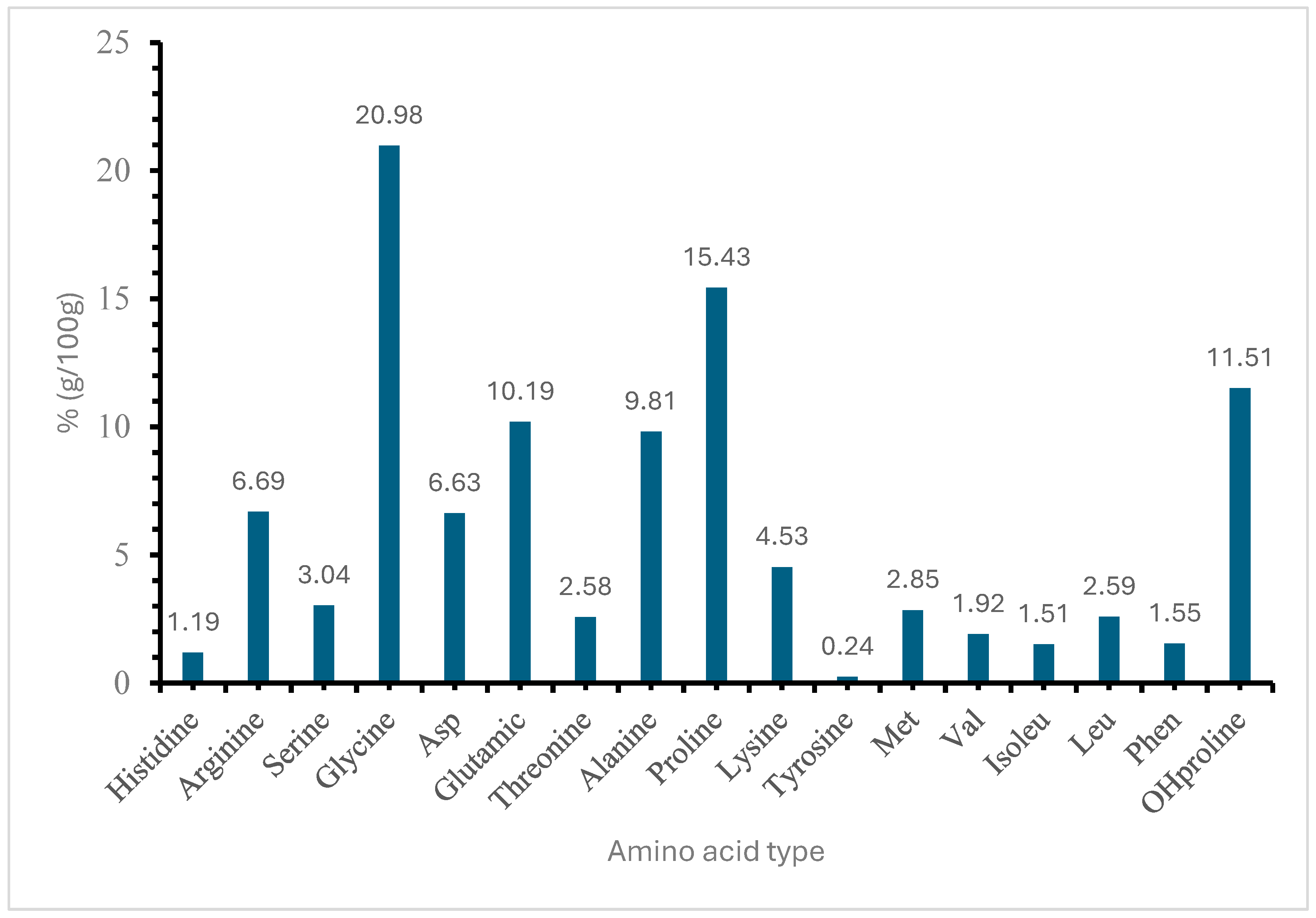

Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins, and their distribution is crucial in determining the overall characteristics of the protein. The composition of the amino acids in 100 g revealed 17 different types of amino acids (

Figure 4). The high percentages of glycine (20.98%), proline (15.43%), and hydroxyproline (11.51%) suggest a significant presence of structural proteins like collagen. According to Gauza-Włodarczyk, Kubisz [

42], glycine determines the regular structure of the collagen chain and allows for the formation of stabilizing bonds between chains.

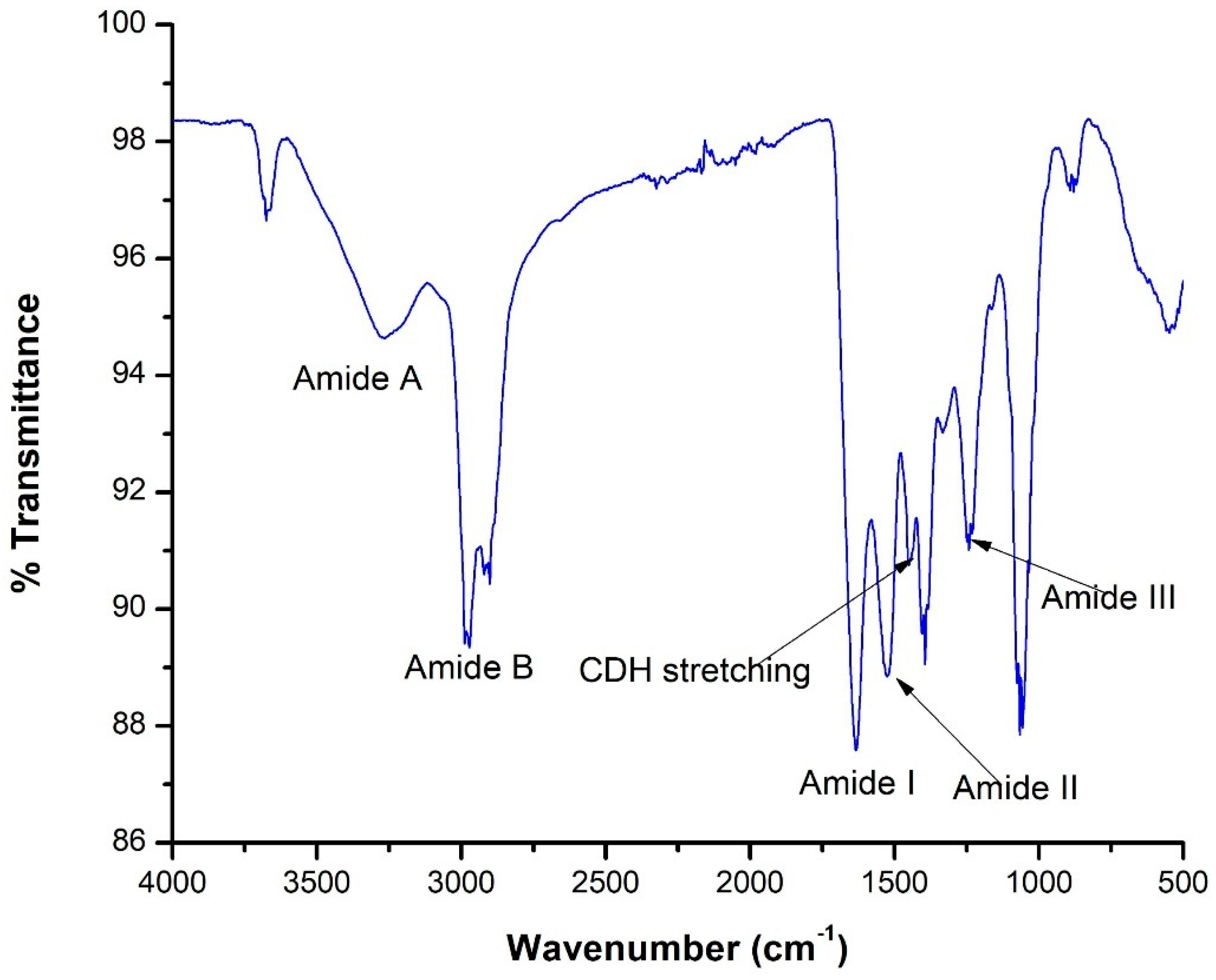

The FTIR spectrum in

Figure 5displays several peaks corresponding to distinct amide bands (A, B, I, II, and III), which are characteristic of collagen due to their association with peptide bonds in protein structures [

43,

44]. For instance, the amide A band appears around 3,293 cm

−1, representing N─H stretching vibrations typical of peptide bonds found in proteins like collagen. The amide B band, at approximately 2,927 cm

−1, is linked to asymmetrical N─H stretching vibrations, also related to peptide linkages. The amide I band, observed around 1,611 cm

−1, is crucial for protein analysis, as it mainly corresponds to C═O stretching vibrations in peptide bonds and provides insights into the protein's secondary structure. The amide II band, at around 1,523 cm

−1, is associated with N─H bending and C─N stretching vibrations, while the amide III band, around 1,300 cm

−1, involves complex vibrations of C─N stretching and N─H bending, offering additional details about the protein’s conformation. Additionally, C─H deformation peaks around 1,451 cm

−1 are linked to C─H stretching vibrations, which originate from various side chains in the collagen molecule [

44].

3. Materials and Methods

Roughly 100 kg of fresh fish scales were obtained from a local fish shop in Durban, South Africa. The samples were brought to the laboratory and rinsed with distilled water and 5 mL of household bleach. The scales were subsequently air-dried for 2 days to eliminate excess water. Sigma-Aldrich, a chemical manufacturer business, provided food-grade acetic acid. All of the reagents and chemicals used were of the highest grade.

3.1. Preparation and Extraction of Fish Scale Collagen (FSC) from Fish Scales

Using the collected fish scales, collagen was extracted through acid hydrolysis. All preparation and chemical extraction of the fish scales was done at the Biochemistry and X Laboratory (Durban University of Technology, Durban, and Mintek, Randberg South Africa). Following defrosting to room temperature to facilitate bacteria removal, the scales were air-dried for 2 days to eliminate excess water. FSC was extracted according to a well-established protocol involving demineralization and acid hydrolysis [

45]. The scales were treated with 0.1 N NaOH for 2 days to eliminate non-collagenous proteins and pigments. After washing and drying for 2-3 weeks, collagen extraction was carried out using varied parameters. Collagen extraction involved soaking 100g of scales in varying concentration of acetic acids (0.5M, 1, and 5 M), volume of acid (100, 300, 500) at different soaking time of (30min, 60min, and 120min) at 4°C with intermittent stirring. The solution underwent centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were salted out by adding 9% NaCl, stirred automatically for 1 day, and suspended in a tris glycine buffer at different concentration (2.4mL, 5, and 10mL). Pellets were collected via centrifugation, washed with distilled water, and subjected to dialysis using a dialysis membrane (MWCO 12-14 kDa) to eliminate residual salts. The resulting material was freeze-dried at -80°C under vacuum conditions. Characterization of the resulting collagen was conducted using different analytical techniques.

3.2. Optimization of the Extraction Parameters

As advocated in the literature, the Design of Experiments (DOE) was used to determine the number of screening experiments to optimize the parameters [

46]. A four-factor-three-level at the center point and 36 experiments. The optimal experimental conditions are determined by comparing the mean averages. Fisher RA emphasized the importance of identifying the optimal combination of factors and levels in Design of Experiments (DOE) to achieve desired outcomes. The results are validated through Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) focusing on dominant factors, as indicated by prior studies [

47,

48].

Table 4 illustrates the primary factors and their corresponding levels, while

Table 5 outlines the extraction conditions. Utilizing MINITAB 17 software, this methodology enables the evaluation of test outcomes in the form of signal-to-noise ratios (SN).

Collagen yields were calculated as follows:

3.3. SDS-PAGE Analysis

SDS-PAGE was carried out as per the Laemmli 1970 method to estimate the molecular weight of the enzyme and visualise and evaluate protein purification efficiency. Before SDS-PAGE analysis, the samples (40 µg in 15 µl distilled water) were prepared by mixing them with 5 µl of sample buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, 2% SDS, 2% dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol and 0.02% bromophenol blue). The samples were then heated at 100˚C for 5 minutes and cooled at room temperature. Samples were loaded on the gel (5% stacking gel and 10% resolving gel) and electrophoresed at 20 mA per gel at room temperature, until the dye front reached the end of the gel. Coomassie brilliant blue R250 (0.25% dye, 10% acetic acid, 45% ethanol in distilled water) was used to stain the gels. The gels were destained (7.5% acetic acid, 5.% ethanol in distilled water) and photographed with a Gel Doc XR system (BioRad).

3.4. Protein Estimation

The Kjeldahl method was used to determine the amino acid content of the extracted FSC, while the Stegmann method [

49] was applied to measure the hydroxyproline concentration. An automatic amino acid analyzer was employed to obtain the results for the amino acid composition of FSC, as presented in

Figure 2. Since amino acids serve as the fundamental components of proteins, their distribution plays a key role in defining the protein's overall properties.

3.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Assessment.

The Perkin Elmer Universal ATR was used to analyze the structural changes in the PU composite. A background scan was conducted before the actual measurements. Each prepared sample was then placed in a sample holder and scanned with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ over the wavenumber range of 400 to 4,500 cm⁻¹.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the Taguchi methodology was implemented and the optimal conditions (concentration of acetic acids, buffer, volume, and time) to obtain the highest collagen yield (per 100g of fish scales) were determined. Th finding suggests that the maximum collagen yield of 17.14 ± 0.05 mg/g of fish scales was achieved under the optimal conditions. This study has showed that improved yield of collagen was obtained when the concentration of acetic acid was 0.5 M, Volume of acid of 100mL, soaking time of 120 minutes and time and buffer concentration of 10 mL. It was found that three of variables except time of soaking, showed a significant effect on the extraction of collagen from the fish scales and a positive relation was observed acetic acid concentration and Tris-Glycine Buffer variables. The obtained mathematical model had an R2 value of 73.84% and a P-value of < 0.0001 which implicated a moderate agreement of the experimental values of the yield of collagen from the fish scales and affirmed a good generalization of the mathematical model. FTIR analysis confirmed the presence of characteristic collagen peaks at 1611 cm⁻¹ (amide I), 1523 cm⁻¹ (amide II), and 1300 cm⁻¹ (amide III), indicating the successful extraction of Type I collagen. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed a protein banding pattern consistent with the molecular weight of collagen.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.U.M., S.O, N.M.; Methodology, M.U.M., Z.O., D.N., and A.B.; Fish scale extraction, M.U.M., S.O., and Z.O.; Chemical characterization, M.U.M., S.O., D.N., and Z.O.; Formal analysis, M.U.M., S.O, and A.B.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.U.M. and S.O.; Draft revision and editing, N.M., A.B and Z.O.; Supervision, S.O., A.K., and B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Durban University of Technology Hlomisa Funding and National Research Fund (NRF) [BAAP22060920380].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

: Data can be made available by the author on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledged the support provided by the Department of Biotechnology and Food Science at the Durban University of Technology and Health Platform, Advanced Materials Division at Mintek.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dutta, S., et al., Chemical evidence of preserved collagen in 54-million-year-old fish vertebrae. Palaeontology, 2020. 63(2): p. 195-202.

- Schmidt, M., et al., Collagen extraction process. International food research journal, 2016. 23(3): p. 913.

- San Antonio, J.D., et al., Collagen structure-function mapping informs applications for regenerative medicine. Bioengineering, 2020. 8(1): p. 3. [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, G.K.S., et al., Extraction, optimization and characterization of collagen from sole fish skin. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 2018. 9: p. 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Shi, S., et al., Recent progresses of collagen dressings for chronic skin wound healing. Collagen and Leather, 2023. 5(1): p. 31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., et al., Application of collagen-based hydrogel in skin wound healing. Gels, 2023. 9(3): p. 185. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L., et al., The use of collagen-based materials in bone tissue engineering. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023. 24(4): p. 3744. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Z. Wang, and Y. Dong, Collagen-based biomaterials for tissue engineering. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 2023. 9(3): p. 1132-1150. [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, D., et al., Effectiveness of Fish Scale-Derived Collagen as an Alternative Filler Material in the Fabrication of Polyurethane Foam Composites. Advances in Polymer Technology, 2024. 2024(1): p. 1723927. [CrossRef]

- Onwubu, S.C., et al., Enhancing Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Epoxy Composites with Fish Scale-Derived Collagen Reinforcement. Advances in Polymer Technology, 2024. 2024(1): p. 8890654. [CrossRef]

- Jadach, B., Z. Mielcarek, and T. Osmałek, Use of Collagen in Cosmetic Products. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 2024. 46(3): p. 2043-2070. [CrossRef]

- Cadar, E., et al., Marine Antioxidants from Marine Collagen and Collagen Peptides with Nutraceuticals Applications: A Review. Antioxidants, 2024. 13(8): p. 919. [CrossRef]

- Owczarzy, A., et al., Collagen-structure, properties and application. Engineering of Biomaterials, 2020. 23(156).

- Rezvani Ghomi, E., et al., Collagen-based biomaterials for biomedical applications. Journal of biomedical materials research Part B: applied biomaterials, 2021. 109(12): p. 1986-1999.

- Subhan, F., et al., Fish scale collagen peptides protect against CoCl2/TNF-α-induced cytotoxicity and inflammation via inhibition of ROS, MAPK, and NF-κB pathways in HaCaT cells. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2017. 2017(1): p. 9703609.

- Dang, Q., et al., Fabrication and evaluation of thermosensitive chitosan/collagen/α, β-glycerophosphate hydrogels for tissue regeneration. Carbohydrate polymers, 2017. 167: p. 145-157.

- Septiani, R.A., et al., Pemanfaatan Kolagen dari Hewan. Jurnal Buana Farma, 2023. 3(2): p. 24-32. [CrossRef]

- Smith, I., et al., Characterization of the Biophysical Properties and Cell Adhesion Interactions of Marine Invertebrate Collagen from Rhizostoma pulmo. Marine Drugs, 2023: p. 21. [CrossRef]

- Browne, S., D.I. Zeugolis, and A. Pandit, Collagen: finding a solution for the source. Tissue Engineering Part A, 2013. 19(13-14): p. 1491-1494. [CrossRef]

- Rajabimashhadi, Z., et al., Polymers. Collagen derived from fish industry waste: progresses and challenges, 2023. 15(3): p. 544. [CrossRef]

- Coppola, D., et al., Marine collagen from alternative and sustainable sources: Extraction, processing and applications. Marine drugs, 2020. 18(4): p. 214. [CrossRef]

- Tziveleka, L.A., et al., Valorization of fish waste: Isolation and characterization of acid-and pepsin-soluble collagen from the scales of mediterranean fish and fabrication of collagen-based nanofibrous scaffolds. Marine Drugs, 2022. 20(11): p. 664. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H., et al., Waste-to-resource: Extraction and transformation of aquatic biomaterials for regenerative medicine. Biomaterials Advances, 2024: p. 214023. [CrossRef]

- Kıyak, B.D., et al., Advanced technologies for the collagen extraction from food waste–A review on recent progress. Microchemical Journal, 2024: p. 110404. [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.-C., J.-G. Wu, and S.-C. Luo, Revisiting background signals and the electrochemical windows of Au, Pt, and GC electrodes in biological buffers. ACS Applied Energy Materials, 2019. 2(9): p. 6808-6816. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Menezes, M.d.L.L., et al., Optimization of the collagen extraction from Nile tilapia skin (Oreochromis niloticus) and its hydrogel with hyaluronic acid. COLLOIDS AND SURFACES B-BIOINTERFACES, 2020. 189.

- Meena, N.K., et al., Modified taguchi-based approach for optimal distributed generation mix in distribution networks. IEEE Access, 2019. 7: p. 135689-135702. [CrossRef]

- Hamzaçebi, C., et al., Taguchi method as a robust design tool. Quality Control-Intelligent Manufacturing, Robust Design and Charts, 2020: p. 1-19.

- Mokrejš, P., R. Gál, and J. Pavlačková, Enzyme conditioning of chicken collagen and taguchi design of experiments enhancing the yield and quality of prepared gelatins. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023. 24(4): p. 3654. [CrossRef]

- Aidat, O., et al., Optimisation of gelatine extraction from chicken feet-heads blend using Taguchi design and response surface methodology. International Food Research Journal, 2023. 30(5). [CrossRef]

- Nagai, T. and N. Suzuki, Isolation of collagen from fish waste material—skin, bone and fins. Food chemistry, 2000. 68(3): p. 277-281.

- Kim, S.-K. and E. Mendis, Bioactive compounds from marine processing byproducts–a review. Food research international, 2006. 39(4): p. 383-393. [CrossRef]

- Carballares, D., J. Rocha-Martin, and R. Fernandez-Lafuente, The stability of dimeric D-amino acid oxidase from porcine kidney strongly depends on the buffer nature and concentration. Catalysts, 2022. 12(9): p. 1009. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., et al., Modulating physicochemical properties of collagen films by cross-linking with glutaraldehyde at varied pH values. Food Hydrocolloids, 2022. 124: p. 107270. [CrossRef]

- Kittiphattanabawon, P., et al., Isolation and characterisation of collagen from the skin of brownbanded bamboo shark (Chiloscyllium punctatum). Food Chemistry, 2010. 119(4): p. 1519-1526. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K., et al., Application of ultrasonic treatment to extraction of collagen from the skins of sea bass Lateolabrax japonicus. Fisheries Science, 2013. 79: p. 849-856. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., et al., Optimization of conditions for extraction of acid-soluble collagen from grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) by response surface methodology. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 2008. 9(4): p. 604-607. [CrossRef]

- Darvish, D.M., Collagen fibril formation in vitro: From origin to opportunities. Materials Today Bio, 2022. 15: p. 100322. [CrossRef]

- Inanc, S., D. Keles, and G. Oktay, An improved collagen zymography approach for evaluating the collagenases MMP-1, MMP-8, and MMP-13. Biotechniques, 2017. 63(4): p. 174-180. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Morales, L., et al., Germline gain-of-function MMP11 variant results in an aggressive form of colorectal cancer. International Journal of Cancer, 2023. 152(2): p. 283-297.

- Salvatore, L., et al., On the effect of pepsin incubation on type I collagen from horse tendon: Fine tuning of its physico-chemical and rheological properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2024. 256: p. 128489. [CrossRef]

- Gauza-Włodarczyk, M., L. Kubisz, and D. Włodarczyk, Amino acid composition in determination of collagen origin and assessment of physical factors effects. International journal of biological macromolecules, 2017. 104: p. 987-991. [CrossRef]

- Elbialy, Z.I., et al., Collagen extract obtained from Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) skin accelerates wound healing in rat model via up regulating VEGF, bFGF, and α-SMA genes expression. BMC veterinary research, 2020. 16: p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Onwubu, S., et al., Enhancing Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Epoxy Composites with Fish Scale-Derived Collagen Reinforcement. Advances in Polymer Technology, 2024. 2024(1): p. 8890654.

- Wahyuningsih, R., et al., Optimization of acid soluble collagen extraction from Indonesian local “Kacang” goat skin and physico-chemical properties characterization. Chemical Engineering Transactions, 2018. 63: p. 703-708.

- Dixit, A. and K. Kumar, Optimization of mechanical properties of silica gel reinforced aluminium MMC by using Taguchi method. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2015. 2(4-5): p. 2359-2366. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S., et al., Taguchi L8 (27) orthogonal array design method for the optimization of synthesis conditions of manganese phosphate (Mn3 (PO4) 2) nanoparticles using water-in-oil microemulsion method. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 2016. 219: p. 1131-1136. [CrossRef]

- Meena, K., A. Kumar, and S.N. Pandya, Optimization of friction stir processing parameters for 60/40 brass using Taguchi method. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2017. 4(2): p. 1978-1987.

- Hurych, J., Methods of hydroxyproline determination. Kozarstvi, 1962. 12: p. 317-323.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).