1. Introduction

Headache is the most common cause of chronic or recurrent pain in childhood and adolescence [

1] and affects school performance, social and physical activities and quality of life [

2,

3] but is still underdiagnosed and insufficiently treated. The longer course of headache means greater risk of developing chronic headache and associated comorbidities such as an anxiety and depression [

4,

5]. Therefore, it is essential to make an early diagnosis and implement preventive measures.

The most common primary headaches in children are migraine and tension-type headache [

6]. These two types of headaches have a shared prevalence of 62% [

7]. A recent meta-analysis revealed that the prevalence of childhood migraine is 11% [

7], indicating an increase compared to previously known data. The prevalence of tension-type headache is from 17% to 29% [

7,

8] emphasizing that the prevalence of tension-type headache is more diverse due to variability of headache characteristics during childhood and adolescence [

9].

The diagnosis of migraine and tension-type headache is based on the criteria of the International Classification of Headache disorders, third edition (ICHD-3) and these criteria are applicable in both children and adults with some differences [

10]. Some of the differences are officially included in ICHD-3, such as the duration of migraine attacks being 2-72 hours in children, while others are only mentioned in the commentary of ICHD-3. [

10]. One of the main controversies in clinical work is the duration of migraine pain in children, with studies showing that migraine pain in children can last less than 1 hour [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Another difference is the localization of the migraine headache, as the pain in children is often bilateral, while unilateral pain occurs from adolescence [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The character of the pain also differs, with throbbing pain being most common in children [

18], and pulsating pain most common in adults. Considering these differences, migraine and tension type-headache have more overlapping than distinctive features, making it even more difficult to differentiate the type of primary headache based solely on clinical characteristics.

One clear distinguishing factor between the two most common types of primary headaches is their pathophysiology. The pathophysiology of tension-type headache is the result of a combination of genetic factors, myofascial mechanisms, and central sensitization of nociceptive pathways, as well as dysfunction in the descending modulation of pain which leads to the development of chronic pain [

19]. Migraine, on the other hand, has several phases including the prodromal phase, aura phase, headache phase, postdrome phase, and interictal phase, each characterized by specific pathophysiological hallmarks [

20]. The prodromal phase can start hours or even days before the headache phase and involves a complex interaction between cortical and subcortical brain regions with the hypothalamus as the main driver [

21]. The aura phase is specific to migraine with aura and is associated with cortical spreading depression (CSD) representing a slowly spreading wave of depolarization followed by hyperpolarization of cortical neuronal and glial cells [

22,

23].

CSD activates the trigeminovascular system (TGVS), initiating the headache phase [

24,

25]. TGVS activation causes the release of various neuropeptides in the vascular branches of the meninges, including substance P (SP), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACP), neurokinin A, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) - a neuropeptide that plays a crucial role in migraine [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The postdrome phase occurs between the end of the headache phase and the return to the state before the onset of the migraine attack. Symptoms during this phase may include neck stiffness, difficulty concentrating and fatigue, lasting for more than 24 hours [

32,

33,

34]. The interictal phase is the period between two migraine attacks.

CGRP acts on multiple sites along the trigeminovascular pathway. It is a potent vasodilator of cerebral blood vessels [

35,

36,

37,

38], involved in initiating neurogenic inflammation [

39], and mediating peripheral and central sensitization [

30,

40,

41,

42]. Numerous studies confirm the central role of CGRP in the pathophysiology of migraine in adults [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51].

The potential importance of CGRP in childhood migraine pathology has been explored in a small number of studies with inconsistent results. A study comparing the levels of CGRP in the blood during (ictally) and between migraine attacks (interictally) in adolescent subjects (aged 13-18 years) with migraine without aura (MO) and migraine with aura (MA) compared to healthy controls found no difference in CGRP levels between the study groups during non-attack periods. However, higher levels of CGRP were reported during attacks in subjects with MA [

52]. Fan et al. found higher ictal and interictal levels of CGRP in migraineurs compared to healthy controls and group with non-migraine headache [

53,

54]. Similarly, Liu et al. demonstrated higher plasma CGRP levels in children with migraine compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, CGRP levels were found to be higher during ictal periods than interictal periods, and also higher in subjects with MA compared to MO subjects [

55]. In contrast to these studies, Hanci et al. found no differences in CGRP levels between children with migraine and healthy controls both ictally and interictally [

56]. The inconsistency and lack of reproducibility of the performed researches are probably the result of the different methodology of measuring plasma CGRP as well as the inhomogeneity of study subjects [

57].

This study prospectively investigated interictal serum CGRP levels in children with migraine compared to children with tension-type headache and healthy controls. The results were analyzed based on different subgroups of patients, and the correlation between CGRP levels and the demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects was studied. The diagnostic value of CGRP in children with different types of primary headaches was also analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Participants

We prospectively enrolled 178 study subjects who attended the pediatric neurology clinic at the Children’s Hospital Zagreb, a tertiary medical center in Croatia. Out of these, 66 (37.1%) had migraine, 59 (33.1%) had tension-type headaches, and 53 (29.8%) were healthy controls. The participants were aged between 5 and 18 years, and we categorized them based on the age of headache onset into three groups: those whose headaches started before the age of 7, those with an onset age of 7-12 years, and those with an onset age of over 12 years.

Inclusion criteria of migraine patients included diagnosis of MO or MA or probable migraine with or without aura ( pMA, pMO) defined by ICHD-3 [

10]. Tension-type headache group included subjects with episodic tension type headache (TTH) and probable episodic tension type headache (pTTH) also defined by the ICHD-3 [

10]. In the tension-type headache group 13 participants (22%) had pTTH, 46 (78%) had definitive TTH and in the migraine group 40 (60%) subjects had MO, 12 (18%) subjects had MA, and pMA/pMO type had 7 (11%) respondents in each subgroup. The exclusion criteria were: secondary headache, headache after head trauma, other primary headaches except migraine and tension-type headache, chronic migraine or chronic tension-type headache, prophylactic headache therapy, migraine attack or episode of tension-type headache within 72 hours before blood sampling for CGRP, abortive headache therapy taken within 72 hours before blood sampling for CGRP, chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, mental retardation, congenital or chromosomal anomalies.

The control group consisted of healthy children whose blood was sampled due to preoperative work-up or anesthesiologic procedures, and who had no anamnestic data of migraine, headache and chronic inflammatory or autoimmune diseases.

All participants had a general physical and neurological examination. The clinical follow-up of the subjects continued for a period of two years when the diagnosis of primary headache was reevaluated. All subjects who were assigned to the probable migraine/probable tension-type headache subgroup were examined by another pediatric neurologist who assessed whether the subject met the diagnostic criteria for migraine/tension-type headache.

The protocol and all procedures carried out in this study follow the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Ethics Committee Faculty of Medicine, University of Osijek and by the Ethical Committee of Children’s Hospital Zagreb and the informed consent had been signed by parents/guardians of study subjects and study participants older than 9 years.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Data collected included age, sex, data on a positive family history of migraine in a first-line relative and data on previous serious illnesses. Comprehensive major symptoms of migraine were recorded including age of onset of headache, course of headache in months, frequency of headache (number of headache days per month), characteristics of headache including number of total headache attacks/episodes, duration of headache (hours), localization of pain, character of pain, assessment of pain according to Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), association of headache with usual physical activity, presence of nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia , existence of and type of aura. All these features of headache were also collected in the group of subjects with tension-type headache.

Headache course was calculated from the first attack of headache to the blood sampling. Headache attack duration was defined as the mean duration per attack per subject, calculated from the beginning to the end of the migraine attack, including sleep time if the subject fell asleep during the headache attack. Headache intensity indicates the severity of the headache attack. The intensity of pain was assessed based on VAS, where 1-3 means mild pain intensity, 4-7 moderate, and 7-10 severe intensity and is applicable to the group of children older than 7 years. In younger children we assessed the intensity of the headache in cooperation with parents according to the level of the child's activity - if the pain is mild then it does not interfere with daily activities, moderate if it interferes, and strong if the child does not participate in the activities of daily life [

15]. Frequency of headache indicated the number of attacks per month per subject.

CGRP Determination

Blood for CGRP sampling was collected during venipuncture at the Children's Hospital Zagreb, from the right or left cubital vein, with the patient in a lying position. A total of 3.5 ml of blood was collected into vacuum tubes (Vacuette, gold-yellow cap, 3.5 ml with gel separator and clot activator, Grainer Bio-One GmbH, Austria).

After collection, the blood sample was immediately centrifuged (10 minutes at 3500 rpm; centrifuge: Hettich GmbH Rotofix 32 A, Germany, 2017). The serum sample was separated after routine laboratory analyses (minimum volume 300 µL) into plastic tubes with a cap and stored at -80°C (freezer: Thermo Scientific TSE240VGP - ULT freezer, -86°C, USA, 2015) until the CGRP determination. The determination of CGRP was performed using the ELISA method according to the manufacturer's instructions [

58] on a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA, 2017) at a wavelength of 405 nm, with results analyzed using the appropriate software (SoftMax Pro 7, Molecular Devices, USA, 2017). Freshly frozen plasma released from endogenous CGRP (extraction procedure) was used as a matrix for control samples (positive and negative control from the manufacturer and for preparing standards (S1 to S8) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The patient samples in this procedure did not undergo the extraction process prior to the ELISA procedure, which is detailed in the manufacturer's instructions.

Reading of results according to preliminary verification results was carried out at a wavelength of 405, 60 minutes after the end point of the ELISA procedure (after the addition of Ellman’s reagent). For CGRP values greater than 1000 pg/mL, the determination was repeated using a diluted sample with ELISA buffer. The manufacturer declares values ranging from 3 to 269 pg/mL (0.8 pmol/L to 71 pmol/L) as the range of values in healthy individuals. Elevated CGRP values are also found in patients undergoing hemodialysis, patients with exacerbated asthma, thyroid cancer patients, and pregnant women.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data are presented with absolute and relative frequencies. Differences between categorical variables were tested with the chi-square test, and if necessary, the Fisher exact test. Normality of distribution of continuous variables was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous data is described with the median and interquartile range. Differences in continuous variables between two independent groups were tested with the Mann-Whitney U test (Hodges-Lehmann median difference with corresponding 95% confidence interval). Differences in normally distributed numerical variables among more than two independent groups were tested with the Kruskal-Wallis test (post hoc Conover). The impact of the biomarker CGRP on the probability of migraine occurrence was evaluated with logistic regression. ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) analysis was used to determine the optimal cutoff point, area under the curve (AUC), specificity, and sensitivity of the CGRP biomarker in predicting migraine probability. All p-values are two-sided. The level of significance was set at alpha = 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using MedCalc® Statistical Software version 22.023 and SPSS 23. The research report was prepared following the guidelines for reporting research results in biomedicine and healthcare.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

Serum samples were collected from 66 children with migraine (40 MO, 12 MA, 7 pMO, 7 pMA), 59 children with tension-type headache (46 TTH, 13 pTTH) and 53 healthy controls. Samples from participants with primary headache were collected between headache episodes (interictally). The average age of the children with migraines was not significantly different from the subjects with tension-type headaches or healthy controls. Demographic data and clinical characteristics of the study subjects are shown in

Table 1.

In 48% of participants, headaches started between the ages of 7-12 years, in 24% at the age younger than 7 years, and the remaining participants were older than 12 years. There was no significant difference in age between the study groups. The duration of headaches was significantly longer in the migraine group compared to the tension-type group (median 25 months vs. 12 months). Although the migraine group had longer duration of headache attacks (6 hours vs. 4 hours), it was not deemed significant. In terms of frequency of headaches, the tension-type group experienced more frequent headaches than the migraine group. Migraine with aura is usually viewed as a more complex type of migraine because it includes additional neurological symptoms and carries a higher risk of certain complications, such as ischemic stroke. Therefore, we have also conducted a comparison between the migraine with aura and migraine without aura subgroups (

Table 2).

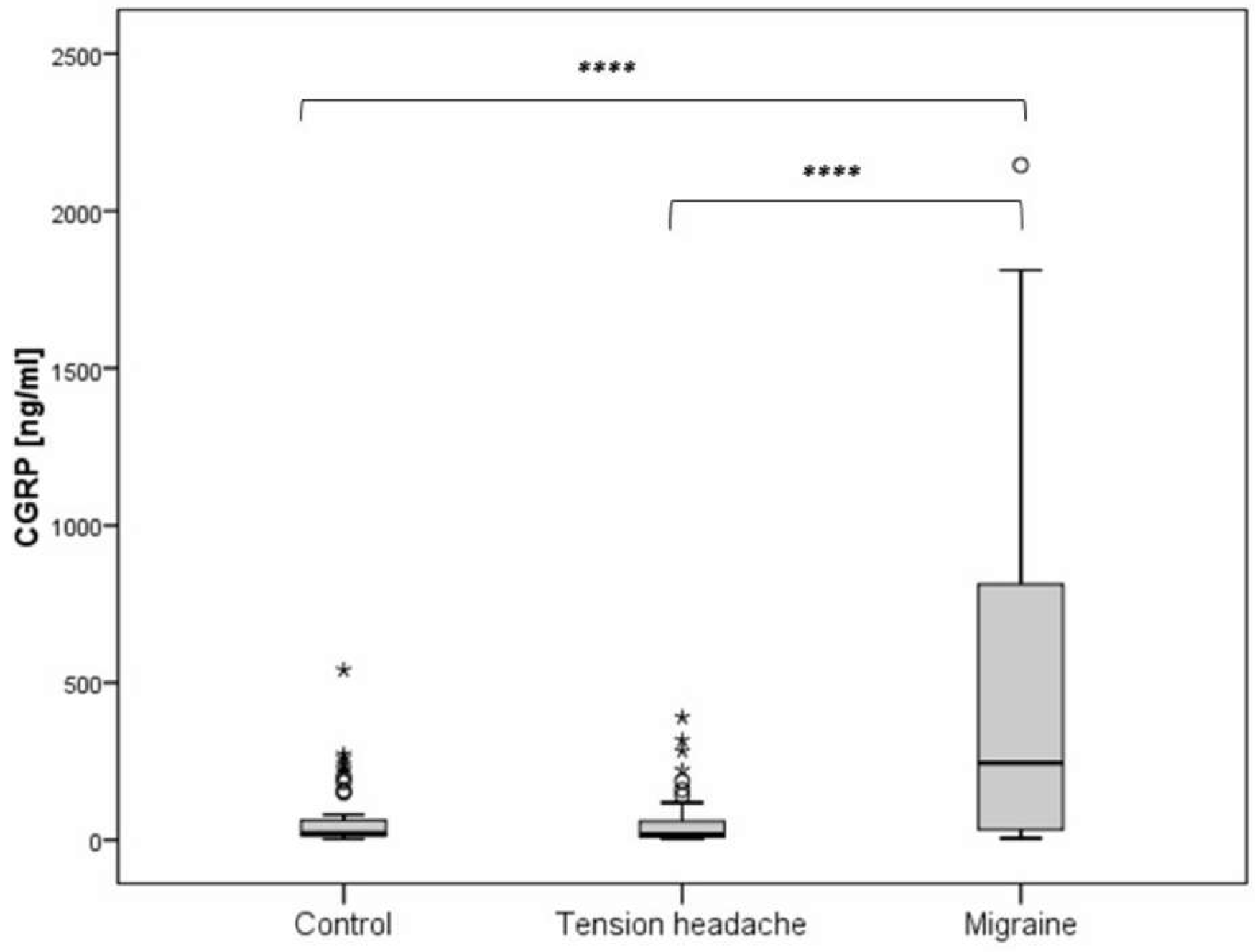

3.2. Serum CGRP Levels in the Migraine Group, Tension-Type Group and Healthy Controls

We examined the interictal serum levels of CGRP in the migraine group, tension-type group, and healthy controls. The migraine group had significantly higher levels of CGRP (CGRP(m): median 245.5, IQR 33.5 - 813.4) compared to the tension-type group (CGRP(t): median 17.3, IQR 9.8 - 60.8) and the healthy control group (CGRP(c): median 20.4, IQR 12.9 - 63.9). There was no significant difference in CGRP levels between the tension-type and control group (

Figure 1).

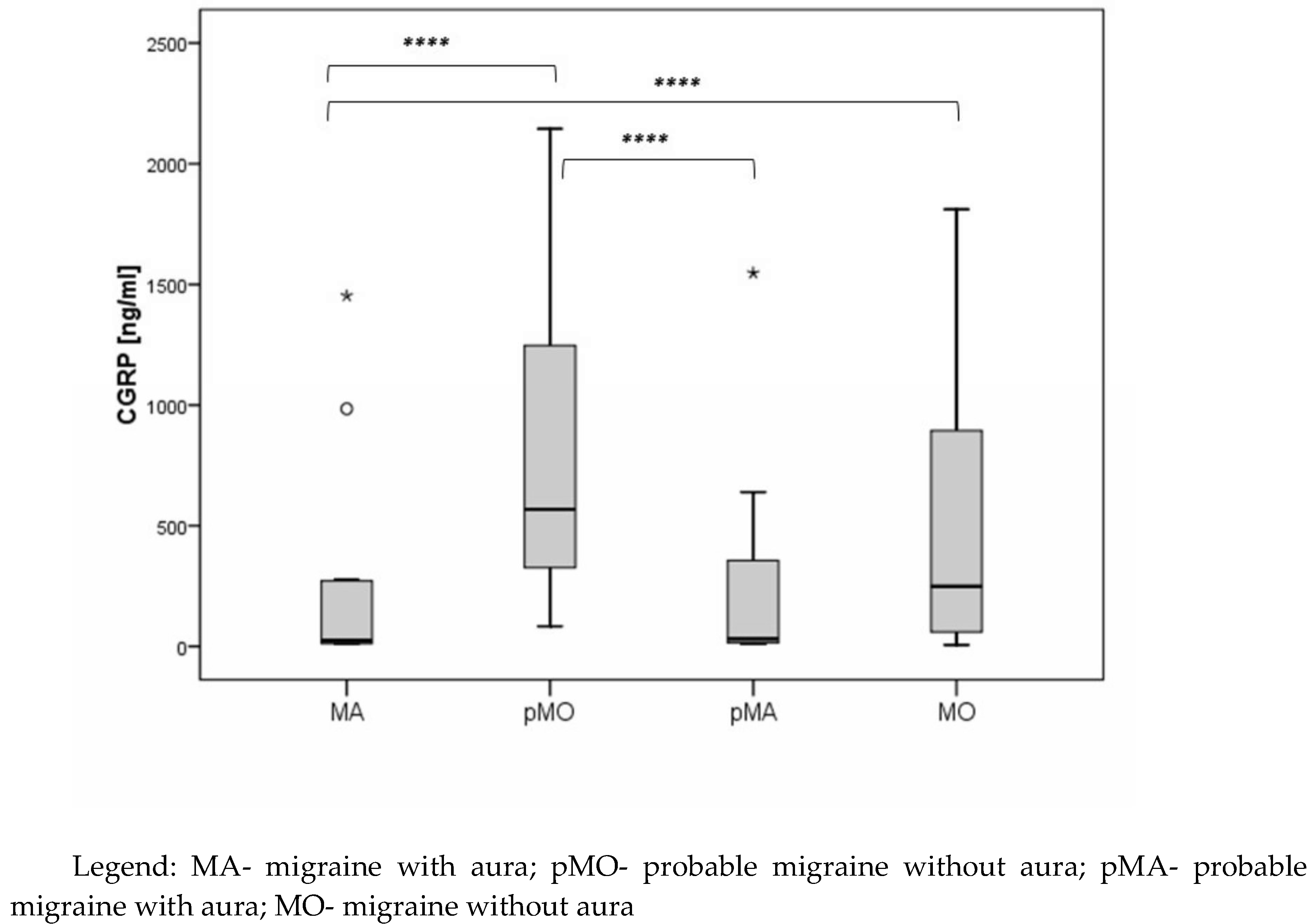

3.3. Plasma CGRP Levels in Pediatric Migraine Without Aura, Migraine with Aura, Probable Migraine Without Aura and Probable Migraine with Aura

CGRP levels were found to be significantly lower in subjects with MA compared to MO and pMO (median 23.3 vs. 249.0 vs. 568.3), and subjects with pMO had significantly higher CGRP levels compared to subjects with pMA (median 568.3 vs. 30.4) (

Figure 2).

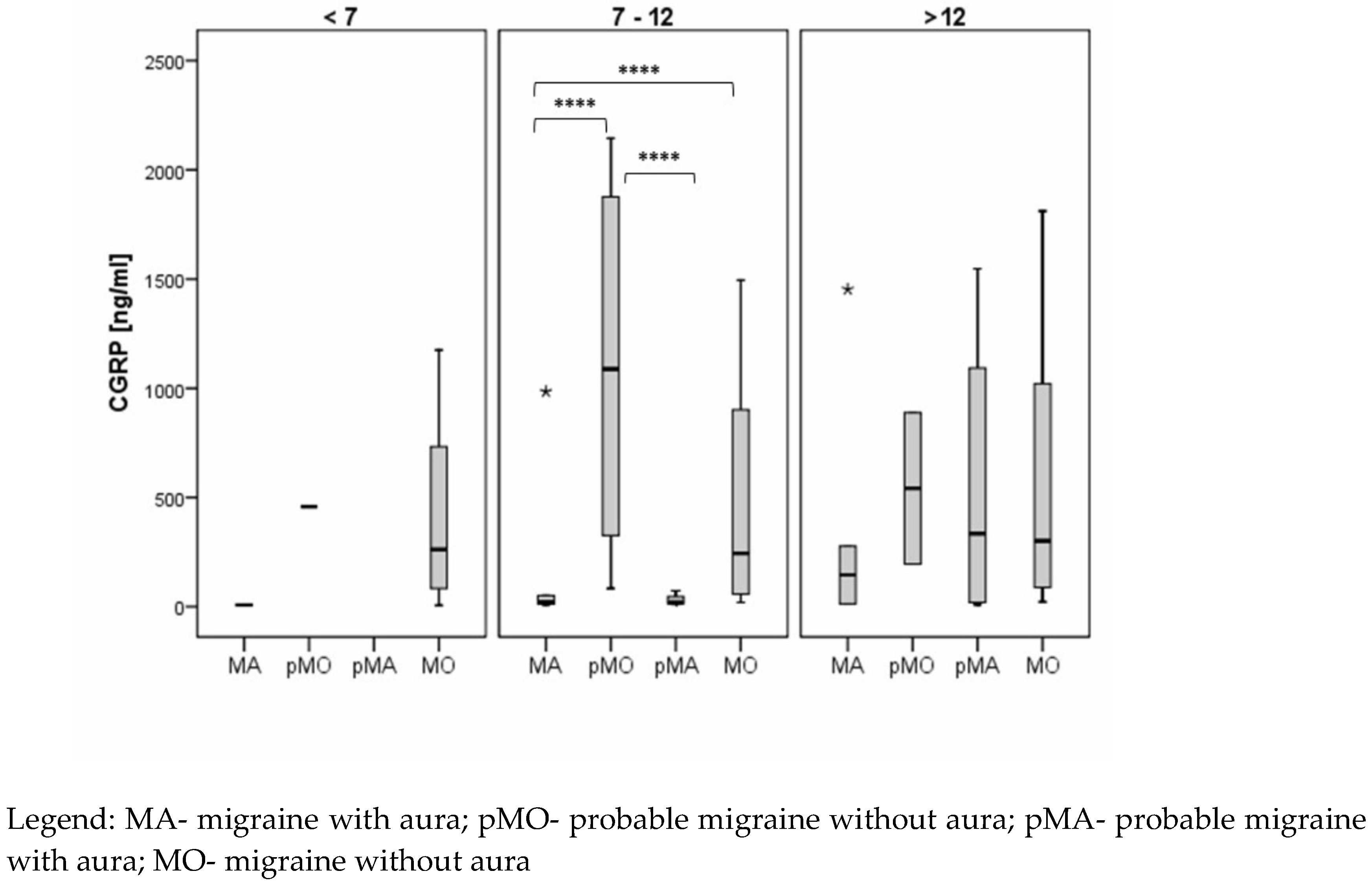

CGRP levels were also significantly lower in subjects with MA whose headaches began between the ages of 7-12 years compared to subjects with MO (median 20.7 vs. 247.6), and similar results were found in pMA/pMO subjects in the same age range (median 18.3 vs. 1087.7). There were no significant differences between MA and MO subgroups for subjects whose headaches began before age 7 and after age 12, and no significant differences were found between pMA and pMO subgroups for subjects whose headaches began after age 12 (

Figure 3).

3.4. The Correlation of CGRP with Clinical Characteristics and Association of CGRP and the Diagnosis of Pediatric Migraine

Univariate regression analysis revealed that serum CGRP levels were significantly correlated only with visual (p = 0.009) and sensory (p = 0.04) aura (

Table 3). We included clinical characteristics with a P-value of less than 0.2 in the multiple linear regression analysis, but the results indicated that none of the predictors showed a significant association with CGRP levels.

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the impact of CGRP on the probability of migraine occurrence. The results indicate that CGRP is a significant predictor of migraine, with an odds ratio of 1.01. This means that individuals with higher CGRP levels have a 1.01 times increased likelihood of experiencing a migraine. Furthermore, CGRP accounts for between 28% (as per Cox & Snell R²) and 39% (according to Nagelkerke R²) of the variance in migraine occurrence, and it accurately predicts 78% of cases.

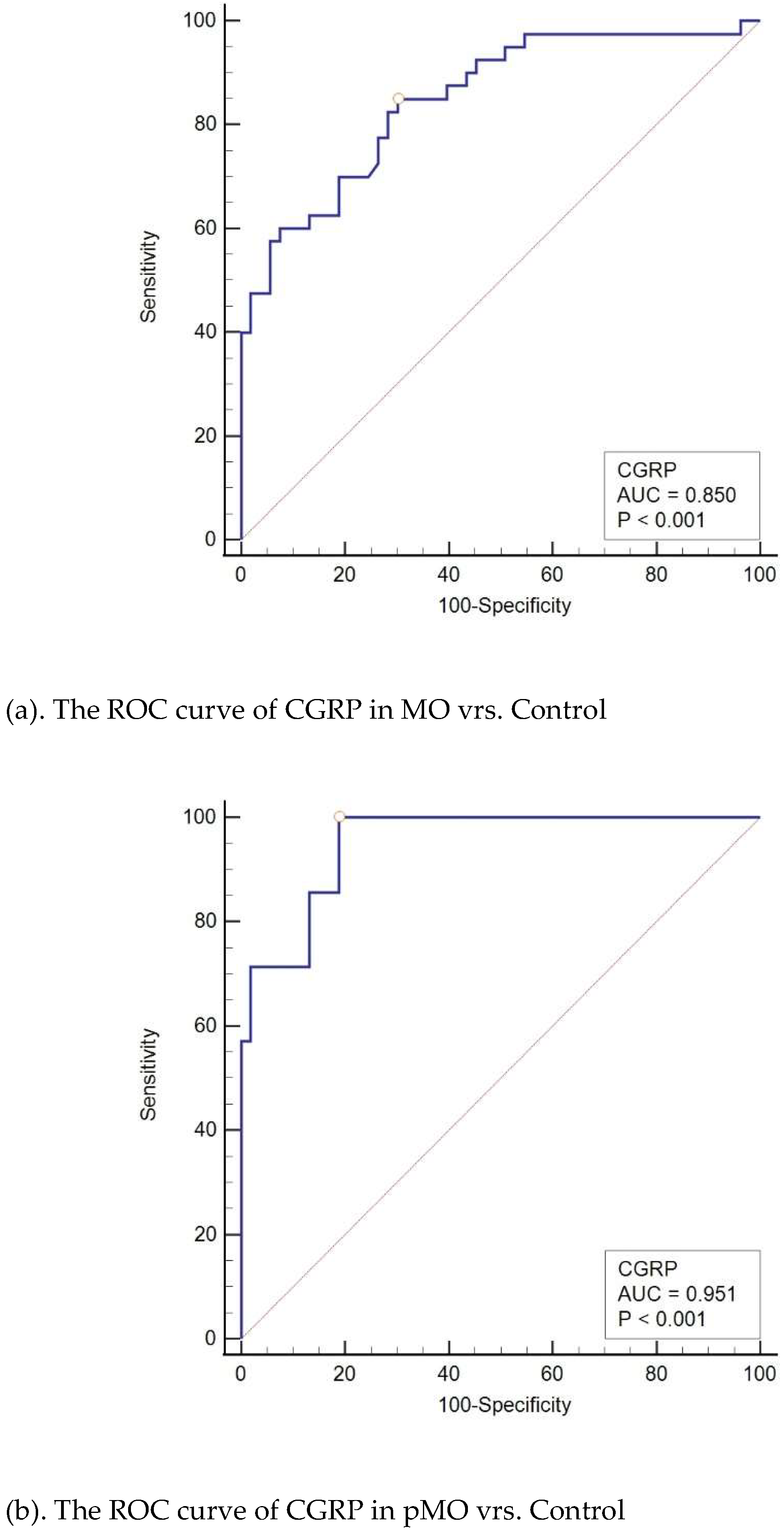

3.5. The Diagnostic Value of CGRP in Pediatric Migraine

When comparing the probability of migraine to that of the control group, CGRP emerged as a significant diagnostic marker for migraine (AUC = 0.779; sensitivity = 51.5; specificity = 94.3; P < 0.001), with a cut-off point of > 241.5. It also served as a notable diagnostic indicator when differentiating migraines from tension-type headaches (AUC = 0.799; sensitivity = 56.1; specificity = 93.2; P < 0.001), with a cut-off point of > 187.4.

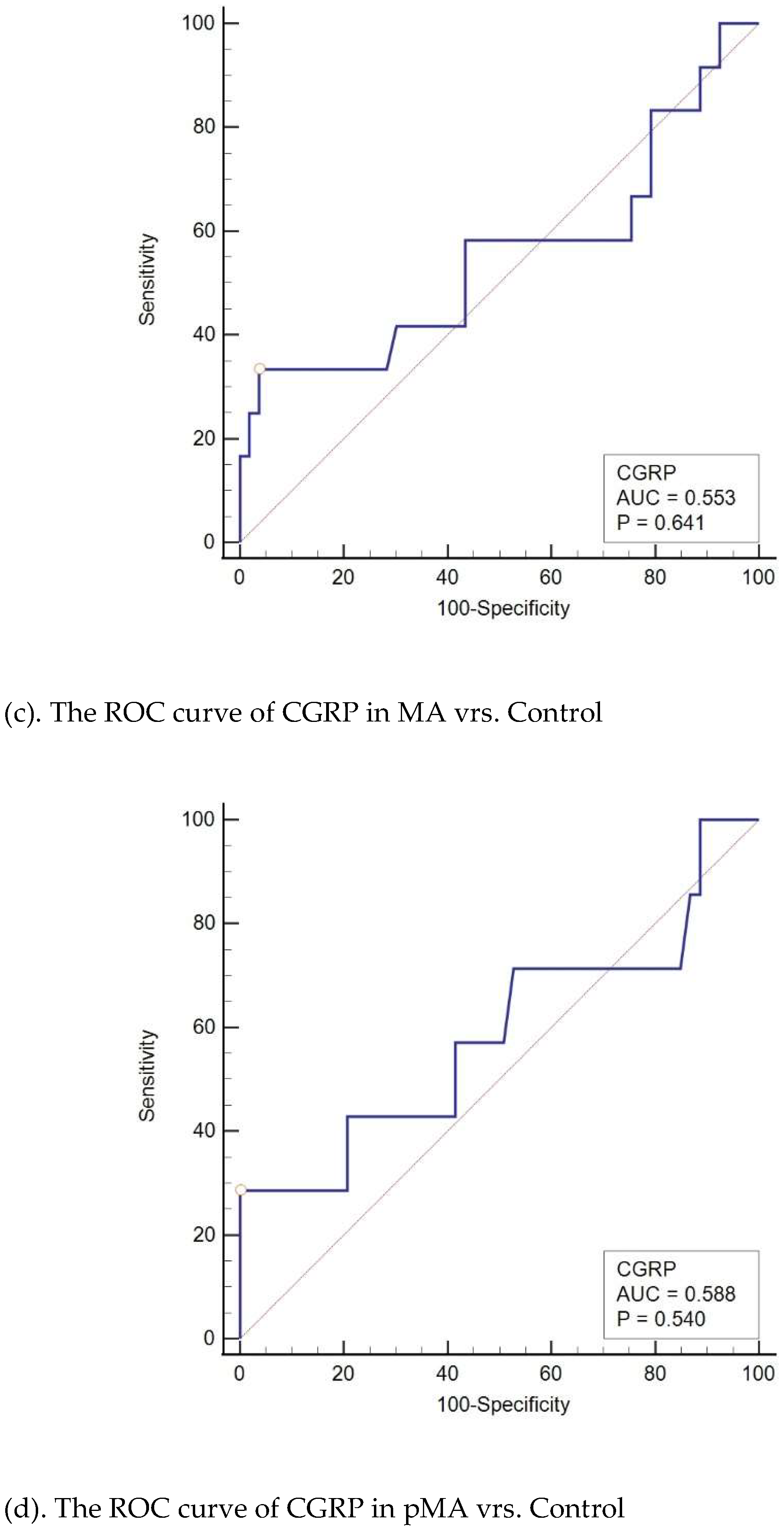

In our analysis of migraine subgroups (MO, MA, pMO, and pMA), CGRP was found to be a significant diagnostic indicator for both MO and pMO but not for MA and pMA. When MO is considered independently from other migraine types, CGRP serves as a significant diagnostic indicator for MO when compared to the tension-type and control groups. The results were even more pronounced than those observed in the entire migraine group with a larger area under the curve (AUC 0.85 vs. 0.779) and with higher sensitivity (85% vs. 51.5%). Similarly, CGRP is a significant diagnostic indicator for pMO when compared to control and tension-type headache. Stil, analysis of CGRP as a diagnostic indicator of MA did not show significance in comparison with the control or tension-type group of subjects and the same applies for pMA (

Figure 4).

(a). The ROC curve of CGRP in MO vrs. Control

(b). The ROC curve of CGRP in pMO vrs. Control

(c). The ROC curve of CGRP in MA vrs. Control

(d). The ROC curve of CGRP in pMA vrs. Control

MO: migraine without aura, pMO: probable migraine without aura, MA: migraine with aura, pMA: probable migraine with aura, AUC: area under the curve, CGRP: calcitonin gene-related peptide

4. Discussion

The results of our study indicate that interictal CGRP values are significantly higher in children with migraine than in children with tension-type headache or in healthy controls. The significance of this research lies in comparing migraine and tension-type headaches, given their often-overlapping characteristics, particularly in children under 7 years of age. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of interictal CGRP levels comparing children with migraine and tension-type headache. Two previously conducted studies compared interictal plasma CGRP levels in subjects with migraine and subjects with non-migraine headache, which included tension-type headache and secondary headaches [

53,

54].

Our subjects with MA had significantly lower CGRP levels than subjects with MO, moreover there was no significant difference in interictal CGRP levels between the MA subgroup and healthy controls. This finding is to be elucidated in future studies with a larger sample sizes, yet the same outcome arises from the work of Al-Khazali et al. which showed that aura reduces the probability of migraine development induced by exogenous CGRP [

59].

We found no significant difference in the CGRP levels between MO and MA subgroups in subjects with headache onset >12 years, but the difference was significant in the group where the headache started at the younger age (7-12 years). Published studies comparing interictal CGRP levels in MO and MA in children showed no difference in interictal levels of CGRP between MO and MA [

52,

55]. In those studies, stratification for age was not performed, but the first study contained only adolescent subjects [

52] and in the second study, subjects with MA had a significantly higher number of migraine attacks per month compared to our subjects [

55]. Significant differences were observed in CGRP values when stratified by aura type, particularly for visual and sensory auras. This suggests that the presence of certain types of aura may be associated with distinct CGRP levels, indicating potential differences in migraine pathophysiology based on aura presence.

In our study, we observed that the levels of CGRP remain consistent in individuals with MO regardless of their age at the onset of headaches. However, in individuals with MA, the levels of plasma CGRP appear to be linked to their age. Research from animal studies indicates that CGRP is produced during the fetal period, with higher levels present in fetus and then levels decreases as age progresses [

60], which supports the idea of age-specific CGRP production. An age-related difference in TGVS response to capsaicin has been observed, especially in adolescent and adult rat model, where adolescent rats showed less reactivity, reinforcing the notion that age influences presentation of disease due to variations in TGVS reactivity [

61]. Thus, it is plausible that the pathophysiological processes underlying migraine, or migraine types, including CGRP production and response to CGRP, are influenced by age.

The absence of significant associations in the multiple regression analysis in this study may have several implications. It suggests that the clinical features of migraine examined in this study do not contribute significantly to CGRP levels. Previous research investigating the link between CGRP levels and clinical features of migraine, such as the frequency and duration of migraine attacks in children, has yielded mixed results. In the study conducted by Hanci et al., there was no correlation between CGRP levels and the frequency or duration of migraine attacks [

56]. Conversely, Liu et al. identified a correlation between CGRP levels, attack duration (greater than 6 hours), and the frequency of attacks (fewer than 15 attacks per month) [

55]. Study in adult subjects found a correlation between CGRP levels and headache intensity and duration while the attack is occurring, with CGRP levels returning to baseline once the migraine episode ended [

52]. A related finding was reported by Gupta et al., who observed a positive correlation between CGRP levels and the duration and frequency of headaches during attacks, although they did not confirm a higher interictal CGRP level in migraine patients compared to those in the control and tension-type headache groups [

62]. The distinction in CGRP levels between episodic migraine and chronic migraine prompted researchers to conclude that the less frequent activation of the TGVS is the cause of lower CGRP levels in episodic migraine [

63]. Studies that reported elevated interictal CGRP levels in episodic migraine were primarily conducted in tertiary care centers, suggesting that the included participants had a more severe form of migraine characterized by increased frequency, pain intensity and attack duration [

48,

49]. The continuous release of CGRP resulting from frequent headaches, as observed in CM, promotes the sensitization of central trigeminal neurons, and electrophysiological evidence indicates that the brain remains hyperexcitable between migraine episodes, making individuals more susceptible to subsequent migraine attacks [

64]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that chronic migraine patients have heightened sensitivity to exogenous CGRP, indicating that CGRP may also function as a modulator of nociceptive transmission within the trigeminal system [

65]. It is plausible that the reactivity of the trigeminal vascular system differs in developmental stages compared to adulthood, and the triggers for its activation and the sensitization of central trigeminal neurons in children may vary.

Regarding the diagnostic value of CGRP in the study by Liu et al., CGRP was identified as a diagnostic indicator of migraine when compared to the control group. ROC analysis showed an area under the curve of 0.869 (AUC) with specificity of 76.62% and sensitivity of 85.53% using a cutoff value above 94.29 pg/ml. However, the diagnosis of migraine in that study was clinical and not strictly based on the ICHD-3 criteria [

55]. Our study achieved higher specificity but lower sensitivity, likely due to the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria.

However, this study is limited by its small sample size, especially given that migraine patients were categorized into four types based on their migraine characteristics and further subdivided into three groups according to the age of headache onset. The small number of subjects, particularly in the youngest age group, poses a limitation to the study. Another limitation is the data that was collected (frequency of migraines, duration of headaches, concomitant symptoms, etc.) depended on the memory of the participants and/or their parents, which may have resulted in bias in the gathered data.

Taking these limitations into account, it appears that interictal levels of CGRP are somewhat specific and sensitive to migraine in children, especially when only considering migraine without aura. Our findings only reflect a cross-sectional analysis of a specific period in the disease course, whereas epidemiological studies classify migraine as a lifelong condition [

66]. Thus, a clearer understanding of CGRP levels would require longitudinal studies and follow-up with migraine patients throughout childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Further research is necessary in younger children, especially considering the limited data on MA in this group, which should include subjects with episodic syndromes that may be related to migraine.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

JSF: conceptualization of the study, investigation, formal data analysis, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, and supervision. ASK: formal data analysis, writing—original draft preparation and approved the final version. VD: formal data analysis, preparation of the draft manuscript, and approved the final version. JLK: assisted in the investigation, formal data analysis, preparation of the draft manuscript, and approved the final version. AKB: assisted in the investigation, formal data analysis and approved the final version. LL: assisted in the investigation, preparation of the draft manuscript, and approved the final version. ID: assisted in the investigation, formal data analysis, preparation of the draft manuscript, and approved the final version. SPR: assisted in the investigation, formal data analysis, preparation of the draft manuscript, and approved the final version. APF: assisted in the investigation, formal data analysis, preparation of the draft manuscript, and approved the final version. KV: assisted in the investigation, preparation of the draft manuscript, and approved the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scientific Center of Excellence for Reproductive and Regenerative Medicine, Republic of Croatia, and by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund. Specifically, funding was provided under the projects: “Reproductive and Regenerative Medicine - Exploring New Platforms and Potentials” (grant agreement No. KK.01.1.1.01.0008) and “Development and Strengthening of Research and Innovation Capacities, and Application of Advanced Technologies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Childrens Hospital Zagreb (Registry number: 02-23/1-5-20) and with approval by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Osijek (Registry number 2158-61-07-20-152, date of approval 16.09.2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study or their parents/caregivers for subjects under age of 9.

Data Availability Statement

Original data can be obtained from Jadranka Sekelj Fures upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our patients and their parents, as well as the medical and laboratory staff involved in the work-up and treatment of these patients. We would also like to thank our collaborators from Scientific Center of Excellence for Reproductive and Regenerative Medicine, Republic of Croatia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Philipp, J.; Zeiler, M.; Wöber, C.; Wagner, G.; Karwautz, A.F.K.; Steiner, T.J.; Wöber-Bingöl, Ç. Prevalence and burden of headache in children and adolescents in Austria – a nationwide study in a representative sample of pupils aged 10–18 years. J. Headache Pain 2019, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, M.A.; Bigal, M.E. Behavioral and emotional symptoms and primary headaches in children: a population-based study. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2012, 32, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofri, A.; Olivieri, L.; Silva, P.; Bernassola, M.; Tozzi, E. Correlation between primary headaches and learning disabilities in children and adolescents. Minerva Pediatr. 2022, 74, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, V.; Galli, F. Evolution of headache in childhood and adolescence: an 8-year follow-up. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 1998, 18, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, E.F.; Blume, H.; Palermo, T.M. Longitudinal Impact of Parent Factors in Adolescents With Migraine and Tension-Type Headache. Headache 2020, 60, 1722–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Arafeh, I.; Gelfand, A.A. The childhood migraine syndrome. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onofri, A.; Pensato, U.; Rosignoli, C.; Wells-Gatnik, W.; Stanyer, E.; Ornello, R.; Chen, H.Z.; De Santis, F.; Torrente, A.; Mikulenka, P.; et al. Primary headache epidemiology in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Headache Pain 2023, 24, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovner, L.J.; Hagen, K.; Linde, M.; Steiner, T.J. The global prevalence of headache: an update, with analysis of the influences of methodological factors on prevalence estimates. J. Headache Pain 2022, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straube, A.; Andreou, A. Primary headaches during lifespan. J. Headache Pain 2019, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [CrossRef]

- Maytal, J.; Young, M.; Shechter, A.; Lipton, R.B. Pediatric migraine and the International Headache Society (IHS) criteria. Neurology 1997, 48, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metsähonkala, L.; Sillanpää, M. Migraine in children--an evaluation of the IHS criteria. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 1994, 14, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortimer, M.J.; Kay, J.; Jaron, A. Childhood migraine in general practice: clinical features and characteristics. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 1992, 12, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershey, A.D.; Winner, P.; Kabbouche, M.A.; Gladstein, J.; Yonker, M.; Lewis, D.; Pearlman, E.; Linder, S.L.; Rothner, A.D.; Powers, S.W. Use of the ICHD-II Criteria in the Diagnosis of Pediatric Migraine. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2005, 45, 1288–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özge, A.; Faedda, N.; Abu-Arafeh, I.; Gelfand, A.A.; Goadsby, P.J.; Cuvellier, J.C.; Valeriani, M.; Sergeev, A.; Barlow, K.; Uludüz, D.; et al. Experts’ opinion about the primary headache diagnostic criteria of the ICHD-3rd edition beta in children and adolescents. J. Headache Pain 2017, 18, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, A.; Mukherjee, A.; Roy, D. Migraine pain location at onset and during established headaches in children and adolescents: a clinic-based study from eastern India. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2007, 27, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, A.; Mukherjee, A.; Roy, D. Migraine pain location: how do children differ from adults? J. Headache Pain 2008, 9, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.W.; Hershey, A.D.; Coffey, C.S.; Chamberlin, L.A.; Ecklund, D.J.; Sullivan, S.; Klingner, E.A.; Yankey, J.W.; Kashikar-Zuck, S.M.; Korbee, L.L.; et al. The Childhood and Adolescent Migraine Prevention (CHAMP) Study: A Report on Baseline Characteristics of Participants. Headache 2016, 56, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashina, S.; Mitsikostas, D.D.; Lee, M.J.; Yamani, N.; Wang, S.-J.; Messina, R.; Ashina, H.; Buse, D.C.; Pozo-Rosich, P.; Jensen, R.H.; et al. Tension-type headache. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2021, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodick, D.W. A Phase-by-Phase Review of Migraine Pathophysiology. Headache 2018, 58 Suppl 1, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, R.; Noseda, R.; Borsook, D. Migraine: multiple processes, complex pathophysiology. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 6619–6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leao, A.A.P. Spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 1944, 7, 359–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.C.; Baca, S.M. Cortical spreading depression and migraine. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 9, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Levy, D.; Noseda, R.; Kainz, V.; Jakubowski, M.; Burstein, R. Activation of meningeal nociceptors by cortical spreading depression: implications for migraine with aura. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 8807–8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolay, H.; Reuter, U.; Dunn, A.K.; Huang, Z.; Boas, D.A.; Moskowitz, M.A. Intrinsic brain activity triggers trigeminal meningeal afferents in a migraine model. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, L. Tracing neural connections to pain pathways with relevance to primary headaches. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2011, 31, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, L.; Hara, H.; Uddman, R. Retrograde tracing of nerve fibers to the rat middle cerebral artery with true blue: colocalization with different peptides. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1989, 9, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, L. The Trigeminovascular Pathway: Role of CGRP and CGRP Receptors in Migraine. Headache 2017, 57 Suppl 2, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messlinger, K.; Hanesch, U.; Baumgärtel, M.; Trost, B.; Schmidt, R.F. Innervation of the dura mater encephali of cat and rat: ultrastructure and calcitonin gene-related peptide-like and substance P-like immunoreactivity. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 1993, 188, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messlinger, K.; Fischer, M.J.M.; Lennerz, J.K. Neuropeptide effects in the trigeminal system: pathophysiology and clinical relevance in migraine. Keio J. Med. 2011, 60, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, F.M.; Hougaard, A.; Schytz, H.W.; Asghar, M.S.; Lundholm, E.; Parvaiz, A.I.; de Koning, P.J.H.; Andersen, M.R.; Larsson, H.B.W.; Fahrenkrug, J.; et al. Investigation of the pathophysiological mechanisms of migraine attacks induced by pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-38. Brain J. Neurol. 2014, 137, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giffin, N.J.; Lipton, R.B.; Silberstein, S.D.; Olesen, J.; Goadsby, P.J. The migraine postdrome: An electronic diary study. Neurology 2016, 87, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, P.; Goadsby, P.J. The migraine postdrome. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2016, 29, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelman, L. The Postdrome of the Acute Migraine Attack. Cephalalgia 2006, 26, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, L.; Fredholm, B.B.; Hamel, E.; Jansen, I.; Verrecchia, C. Perivascular peptides relax cerebral arteries concomitant with stimulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate accumulation or release of an endothelium-derived relaxing factor in the cat. Neurosci. Lett. 1985, 58, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, S.D.; Williams, T.J.; Tippins, J.R.; Morris, H.R.; MacIntyre, I. Calcitonin gene-related peptide is a potent vasodilator. Nature 1985, 313, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanko, J.; Hardebo, J.E.; Kåhrström, J.; Owman, C.; Sundler, F. Calcitonin gene-related peptide is present in mammalian cerebrovascular nerve fibres and dilates pial and peripheral arteries. Neurosci. Lett. 1985, 57, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, J.J.; Craig, R.K.; Marshall, I. Human alpha- and beta-CGRP and rat alpha-CGRP are coronary vasodilators in the rat. Peptides 1986, 7, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskowitz, M.A. Neurogenic inflammation in the pathophysiology and treatment of migraine. Neurology 1993, 43, S16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura-Craig, M.; Gill, B.K. Effect of neurokinin A, substance P and calcitonin gene related peptide in peripheral hyperalgesia in the rat paw. Neurosci. Lett. 1991, 124, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.; Ossipov, M.H.; Johnson, K.W. The role of calcitonin gene–related peptide in peripheral and central pain mechanisms including migraine. Pain 2017, 158, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Winborn, C.S.; Marquez de Prado, B.; Russo, A.F. Sensitization of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors by receptor activity-modifying protein-1 in the trigeminal ganglion. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2693–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goadsby, P.J.; Edvinsson, L. The trigeminovascular system and migraine: studies characterizing cerebrovascular and neuropeptide changes seen in humans and cats. Ann. Neurol. 1993, 33, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goadsby, P.J.; Edvinsson, L.; Ekman, R. Release of vasoactive peptides in the extracerebral circulation of humans and the cat during activation of the trigeminovascular system. Ann. Neurol. 1988, 23, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goadsby, P.J.; Edvinsson, L.; Ekman, R. Vasoactive peptide release in the extracerebral circulation of humans during migraine headache. Ann. Neurol. 1990, 28, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarchielli, P.; Alberti, A.; Codini, M.; Floridi, A.; Gallai, V. Nitric oxide metabolites, prostaglandins and trigeminal vasoactive peptides in internal jugular vein blood during spontaneous migraine attacks. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2000, 20, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goadsby, P.J.; Edvinsson, L.; Ekman, R. Release of vasoactive peptides in the extracerebral circulation of humans and the cat during activation of the trigeminovascular system. Ann. Neurol. 1988, 23, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusayasu, E.; Kowa, H.; Takeshima, T.; Nakaso, K.; Nakashima, K. Increased plasma substance P and CGRP levels, and high ACE activity in migraineurs during headache-free periods. Pain 2007, 128, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashina, M.; Bendtsen, L.; Jensen, R.; Schifter, S.; Olesen, J. Evidence for increased plasma levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide in migraine outside of attacks. Pain 2000, 86, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, L.H.; Haderslev, P.A.; Jacobsen, V.B.; Iversen, H.K.; Sperling, B.; Olesen, J. CGRP may play a causative role in migraine. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2002, 22, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, L.; Linde, M. New drugs in migraine treatment and prophylaxis: telcagepant and topiramate. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2010, 376, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallai, V.; Sarchielli, P.; Floridi, A.; Franceschini, M.; Codini, M.; Glioti, G.; Trequattrini, A.; Palumbo, R. Vasoactive peptide levels in the plasma of young migraine patients with and without aura assessed both interictally and ictally. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 1995, 15, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.-C.; Kuo, P.-H.; Chang, S.-H.; Lee, W.-T.; Wu, R.-M.; Chiou, L.-C. Plasma Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide in Diagnosing and Predicting Paediatric Migraine. Cephalalgia 2009, 29, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.-C.; Kuo, P.-H.; Lee, M.T.; Chang, S.-H.; Chiou, L.-C. Plasma Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide: A Potential Biomarker for Diagnosis and Therapeutic Responses in Pediatric Migraine. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, G.; Dan, Y.; Liu, X. CGRP and PACAP-38 play an important role in diagnosing pediatric migraine. J. Headache Pain 2022, 23, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanci, F.; Kilinc, Y.B.; Kilinc, E.; Turay, S.; Dilek, M.; Kabakus, N. Plasma levels of vasoactive neuropeptides in pediatric patients with migraine during attack and attack-free periods. Cephalalgia 2021, 41, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamm, K. CGRP and Migraine: What Have We Learned From Measuring CGRP in Migraine Patients So Far? Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 930383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin Bioreagent CGRP (human) ELISA kit. Available at: http://content.bertin-bioreagent.com/spibio/docs/pdf/A05481.pdf. Accessed on , 2024. 14 October.

- Al-Khazali, H.M.; Ashina, H.; Christensen, R.H.; Wiggers, A.; Rose, K.; Iljazi, A.; Schytz, H.W.; Amin, F.M.; Ashina, M. An exploratory analysis of clinical and sociodemographic factors in CGRP-induced migraine attacks: A REFORM study. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2023, 43, 3331024231206375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhall, U.; Cowen, T.; Haven, A.J.; Burnstock, G. Perivascular noradrenergic and peptide-containing nerves show different patterns of changes during development and ageing in the guinea-pig. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1986, 16, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.-C.; Kuo, P.-H.; Hu, J.W.; Chang, S.-H.; Hsieh, S.-T.; Chiou, L.-C. Different trigemino-vascular responsiveness between adolescent and adult rats in a migraine model. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2012, 32, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Ahmed, T.; Banerjee, B.; Bhatia, M. Plasma calcitonin gene-related peptide concentration is comparable to control group among migraineurs and tension type headache subjects during inter-ictal period. J. Headache Pain 2009, 10, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Pereda, S.; Toriello-Suárez, M.; Ocejo-Vinyals, G.; Guiral-Foz, S.; Castillo-Obeso, J.; Montes-Gómez, S.; Martínez-Nieto, R.M.; Iglesias, F.; González-Quintanilla, V.; Oterino, A. Serum CGRP, VIP, and PACAP usefulness in migraine: a case-control study in chronic migraine patients in real clinical practice. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 7125–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, G.; Pierelli, F.; Schoenen, J. Is the cerebral cortex hyperexcitable or hyperresponsive in migraine? Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2007, 27, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iljazi, A.; Ashina, H.; Zhuang, Z.A.; Lopez Lopez, C.; Snellman, J.; Ashina, M.; Schytz, H.W. Hypersensitivity to calcitonin gene-related peptide in chronic migraine. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2021, 41, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bille, B. A 40-year follow-up of school children with migraine. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 1997, 17, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).