4.1. Password/PIN and Pattern Authentication

Text passwords are still common because they offer several benefits. They are simple to learn, enforce, and adjust if they are corrupted or forgotten, and they are extremely reliable. Unfortunately, the widespread use of text passwords across thousands of modern user accounts has made creating and remembering a unique and random text password for each account cognitively impossible [

59].

PINs were first utilized in automated dispensing and control systems at gas stations. They were later introduced to “the Chubb system” by the Westminster Bank in the United Kingdom in 1967 [

60]. Since then, PINs have become increasingly common in the banking business worldwide. PINs operated as passwords to protect embedded devices (such as PDAs and smartphones) from unwanted access, thanks to the rapid development of microelectronic technology in the 1990s. The idea of employing passwords to imitate human choices of 4-digit PINs was initially proposed in [

61], and it has sparked a slew of new PIN research [

62].

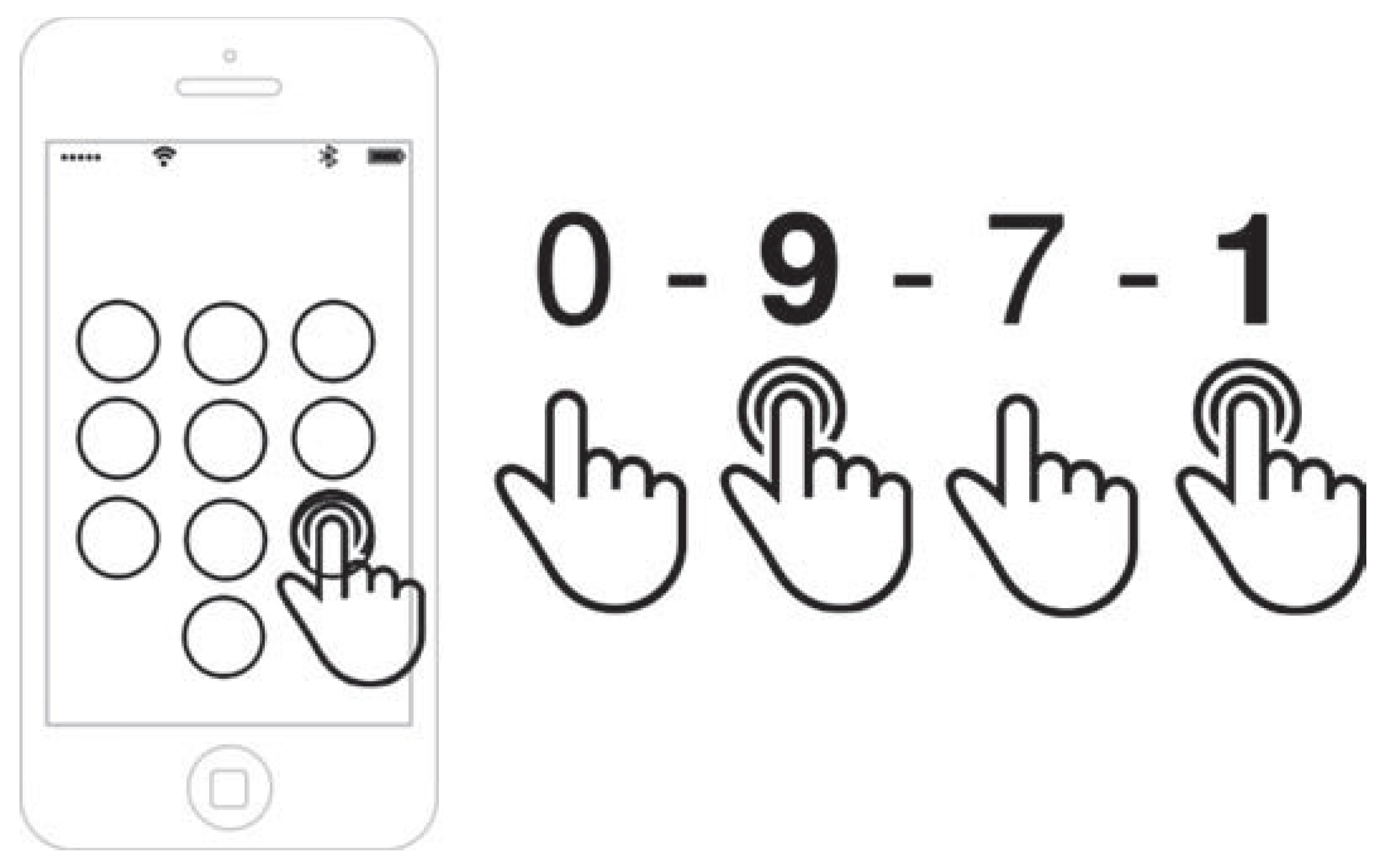

The classic PIN-entry method is commonly used, however it is subject to attacks such as shoulder-surfing and spyware since it requires direct input. [

63] present an indirect input method that uses addition mod 10 and a mini-challenge keypad to produce a one-time PIN (OTP) while concealing the original PIN. Their user study demonstrates that this strategy improves security over traditional PIN systems while maintaining usability, with user comments supporting its use in high-security contexts.

PIN/Password and pattern authentications are the most common authentication methods that exist so far. These approaches are vulnerable to classic attacks like guessing the attacks and surfing the shoulder [

64,

65]. Other MPAS schemes, such as fingerprint and face recognition, complement passwords but are not intended to replace them. Biometrics, according to security experts, make it easier to enter into the systems; on the other hand, passwords are used to create initial trust and as a backup, if biometrics fail [

66]. The DRAW-A-PIN authentication scheme is a suggested way of further improving the pin system [

67]. In this authentication scheme, a user must draw the pin code on his mobile screen instead of simply typing out his pin code. When a pin is drawn, the authentication system will verify the digits entered and then observe the user’s behavior during the pin entry.

Authentication based on patterns is also a very common form of authentication today on many mobile devices [

68]. Many users prefer PIN or text-based passwords because psychological studies indicate that the human brain learns and recalls visual content better than letters and numbers [

69]. Pattern unlock is quite vulnerable to attacks like shoulder surfing and smudge attacks. People choose simple and easy PIN/passwords and patterns to authenticate because these schemes are easy to use and available on almost every mobile device.

[

70] proposed a CAPTCHA AI hard problem-based salted challenge-response MPAS. The proposed framework is based on the same principle as CAPTCHA. i.e., a bot’s ability to recognize twisted text in a picture is a difficult problem. Using the client’s password, the framework combines the challenge text and scatters within a random image rather than submitting it in a way humans will find easy but bots will find prohibitively difficult.

4.1.1. Opportunity

It is not necessary to use the direct password input technique. In social engineering attack scenarios, the attacker can observe the user’s behavior, including password entry operations, while the user is operating his/her mobile device. All types of display information, including user guide material, should be masked against new attack types if the methods entail direct password input procedures. The best approach to achieve this is to create a password entry method that isn’t direct. When using indirect input, guessing the information from the shown data is challenging. As a result, regular PIN codes can be combined with an indirect input mechanism to allow personal identification and authentication.

4.2. Authentication Using Behavioral Features

The widespread implementation of ubiquitous mobile phones is fast expanding due to advances in sophisticated hardware technologies with cutting-edge functionality. These capabilities enable users to save personal information on their devices, with cellphones being one of the most extensively used and accessible technologies in daily life. Smartphones include entry-point authentication techniques to safeguard stored data. However, typical authentication methods are insufficient without strict access restriction. To counter these problems, there is a rising preference for implicit or continuous authentication on smartphones. In the near future, smartphones are likely to include intelligent access control systems that allow for continuous authentication.Behavioral authentication and behavior modeling are closely related techniques. There is extensive study on using behavior modeling approaches to anticipate user characteristics such as traits, personality, and behavior [

71].

Researchers have proposed to use behavioral touch MPAS as a second line of defense if initial authentication is compromised [

72,

73] or as the center for the user who does not configure any of the authentication techniques due to usability issues [

74]. Behavioral authentication is a form of biometric authentication with two benefits: first, it is implicit, ensuring it is done unconsciously. Second, behavioral characteristics are difficult to mimic because it is difficult for others to learn and replicate a person’s behavioral habits after they have been established [

75]. Behavioral biometric information, i.e., touch gestures, mouse movements, and keystrokes, can be gathered via sensor devices and can be helpful to analyze the user’s behavioral attributes for authentication [

76,

77]. In government departments, passport offices, border surveillance, and many consumer devices, there is a growing need for privacy-preserving biometric authentication systems [

78].

A biometric device can be divided into two categories based on the number of modalities used: unimodal and multimodal. unimodal biometric systems focused on a single identifier depend on a single modality for authentication; therefore, they are easier to create. The authentication metric itself can be a single point of failure; an unimodal device faces challenges such as noisy data, poor recognition efficiency, less reliable results, and spoofing attacks [

79] [

80]. A multimodal biometric system uses multiple or combined parameters (for example, face and voice features). It does not depend on a single feature, making it much more stable and difficult to break. It is more resistant to spoofing threats, has higher recognition rates, and has improved accuracy and reliability [

81].

Machine Learning schemes can be used to improve protection schemes for MPAS [

82]. Machine learning techniques are highly successful in enhancing the protection of applications regarding the touch screen of mobile devices. The key advantages of mobile phone safety software training algorithms include recognizing biometric and sensor information to enhance the protection of mobile phones [

56].

Bo et al.[

83] suggested using a support vector machine (SVM) algorithm to create a classification model based on cell phone users’ biometric behavior. The classification model developed updates the SVM model by introducing new features found through self-learning to enhance classification accuracy. The results show that the proposed authentication scheme for identification is fast and accurate.

Song et al. proposed [

84] a secure, easy, and fast authentication framework that was built using multi-touch devices for the use of physiological and behavioral biometrics by the consumer using K-nearest neighbor (KNN) and support vector machine algorithm (SVM). Legitimate hand geometry and compartmental knowledge of users are employed to create a one-class SVM and KNN classification model. The experiment shows that, although the proposed system uses a small number of experimental subjects and analyzes a few movements, the KNN outperforms the SVM in nearly every case.

Ehatisham-ul-Haq et al. [

85] suggested that the performance of the three user-authentication algorithms should be measured and evaluated by Bayesian network (BN), SVM, and KNN. The classifiers were trained to create a mobile user MPAS based on their physical behavior. The three classifiers’ precision was compared. The proposed solution can not provide various access rates when identified based on their biometrics of actions.

Liang et al.[

86] proposed a convolutionary neural network (ConvNet) to predict the user tap series and device usage behavior. Sensor data have been collected as users communicate with the system on different applications, and a classification model based on ConvNet, SVM, and KNN, is established using sensor data. The solution suggested did not make the CovNet model more complex to obtain stable and better performance.

Muhammad Sajjad et al [

87] proposed a hybrid technology with two layers of security, the first layer integrates the palm vein, fingerprints and face recognition and second layer takes these things along with face anti-spoofing convolutional neural networks (CNN) based models to detect spoofing. After matching fingerprints successfully, it is checked on a CNN-based model to verify that it’s fake or real—repetition of the same method with face and palm. Experimental results verified the efficient work of the system, conquering the constraints in spoofing techniques.

Dynamic Time Wrapping (DTW) has been discovered to strengthen the security of mobile devices [

88]. For the MPAS, only a small number of DTWs were used. DTW was used to build a scheme [

89] that validates the user by observing how he/she draws a PIN on a touch screen rather than typing it. Based on the user’s PIN drawing behavior, the DTW algorithm is utilized to compare and realize the similarities between the two PIN drawing samples. The experiment’s findings show that users’ PIN writing behavior can be used for personal identification, and DTW can support the proposed model with promising results. The proposed research uses a small number of experimental subjects and does not equate its findings to those of other classification algorithms.

Current mobile authentication methods that use PIN numbers and physiological biometrics face severe security and usability problems. [

90] focuses on Continuous Authentication (CA) utilizing behavioral biometrics, which allows for passive user verification without requiring explicit actions. A comparison analysis was undertaken using behavioral attributes gathered from common mobile interactions such as typing and tapping, as well as sensor data from numerous mobile sensors. HuMIdb, an innovative public dataset, has significant mobile interaction data that may be used for testing and research in passive authentication. The combination (fusion) of many modalities consistently increased authentication accuracy, resulting in a considerable reduction in EER compared to single-modality systems.

[

91] introduces BehavePassDB, a publicly available database for mobile behavioral biometrics and benchmark evaluation. This database enables continuous authentication by exploiting multimodal data from user interactions with mobile devices, which are organized into separate sessions and jobs. The authors present an experimental protocol that allows for fair comparisons of various approaches while also investigating the performance differences between random and skilled impostor scenarios, emphasizing the effectiveness of Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM) architecture with triplet loss in distinguishing user identity from device characteristics.

[

92] investigates the use of swiping motions as a mechanism for continuous identity verification on mobile devices, demonstrating that behavioral biometrics can be a more user-friendly and effective authentication method than older methods. The study shows that various machine learning classifiers, notably a deep learning model, outperform other models in reliably identifying users based on their distinctive swiping behavior. The study achieves a low Equal Error Rate (EER) of 0.20%, demonstrating hopeful progress in the field of continuous biometric authentication.

Table 3 summarizes the behavioral authentication schemes.

4.2.1. Opportunity

Data encrypting and profiling procedures should be performed on the server to reduce unnecessary energy consumption. Mobile devices should consume as little energy as possible and should only be utilized to detect or sense the owner’s actions. Then, using algorithmic selection, a subset of the data retrieved from each sensor’s raw data should be sent to the server. The server could profile and encrypt the data for authentication purposes before sending it to the mobile device using the selected data. When the data is received, the mobile device can compare it to the current user’s behavior pattern.

4.3. Keystroke Authentication

For MPAS, keystroke dynamics have advanced over time and are now used in mobile phones. The main problem with cell phones, however, is that they can be used anywhere. As a result, examining the utilization of keystroke dynamics using data obtained in different typing positions becomes essential [

94]. Keystroke elements successfully conduct biometric authentication for user validation at a workstation [

95]. Several research works have been done for MPAS using keystroke techniques [

96].

Khan et al. [

97] test the vulnerability of smartphone keystroke dynamics to password stiffening and mimicry attacks. They use feature analysis on a publicly available dataset [

98] to create interfaces that teach users to mimic their victim’s keystroke behavior and propose two schemes for an attacker to get real-time guidance when performing a mimicry attack. Against many passwords, their setup effectively circumvents keystroke dynamics. The researchers perform experiments to demonstrate how malicious insiders can use social engineering to gather keystroke data and then use that data to recreate the victim’s behavior.

Buchoux and Clarke [

99] use a keystroke user authentication scheme and designed software that can be run on Microsoft Windows Mobile 5. They proposed two types of passwords: a strong alphanumeric password and a simple PIN. Three classifiers were also evaluated, namely Mahalanobis distance, FFMLP, and Euclidean distance. Their results suggested that as PIN increased the amount of input data, the performance of the defined classifiers was better when the password was employed. People normally use either a pin or pattern to unlock their cell phones. Users always prefer the simple PIN schemes proposed here because they are too short and easy to use.

Saevanee and Bhattarakosol [

100] proposed a new mechanism for MPAS, named finger pressure, combined with inter-key features and existing hold time. To measure finger pressure, users utilize a mobile touchpad that acts as a touchscreen. Results show 99% accuracy, as this system doesn’t require remembering any complex passwords or pins, just a simple password combined with the user’s behavioral manners.

S Zahid et al. [

101] examined keystroke data from 25 mobile device users. The proposed mechanism takes a total of six characteristics of the keystroke. These characteristics of various users are scattered, and a finicky classifier is utilized to classify and cluster the data. The proposed system has an error rate of 2%, which indicates that the system is user-friendly and can be adopted.

Hwang et al. [

102] suggested MPAS using the keystroke dynamics, which depends on a four-digit PIN. Normally, a four-digit PIN can’t give secure authentication and is vulnerable to guessing and shoulder-surfing attacks. To make it more secure, the authors introduced an input scheme supported by tempo cues and artificial rhythms. Their experiment work shows that the proposed technique reduces the energy efficient ratio from 13% to 4%.

Table 4 summarizes the keystroke authentication schemes.

4.3.1. Opportunity

As technology advances, mobile and portable devices have become increasingly common in people’s daily lives. Smartphones and tablets have ever-increasing memory and processing power compared to a few years ago. Furthermore, advanced and sensitive microhardware sensors, such as multitouch screens, pressure-sensitive panels, accelerometers, and gyroscopes, can unlock new feature data. This upgraded hardware is now widely available, paving the way for future research into keystroke dynamics on this platform.

4.4. Touch Screen Authentication

The touch MPAS has been called "the more natural, unobtrusive future of smartphone biometrics." Google launched pattern lock as a security safety mechanism in 2008 [

107].

Ashley Colley et al. [

108] developed a touchscreen unlocking technique that improves the attack resistance of the commonly used pattern lock mechanism. Their scheme increases the touch password capacity for a specific smudge pattern by 15 factors. In a user test (n=36), users found our model to be more reliable than their current lock system while still being comparable in speed and memorability. The proposed process took an average of 2.2 seconds to unlock the phone (SD=0.9). 1.5 seconds is the average mean time (SD=0.6) for patterns with only the multi-select function, comparable to those illustrated for the regular mechanism for pattern locking.

Watching other users’ login credentials without their permission is commonly called shoulder surfing and has been intensively studied. Research by Malin Eiband et al. [

109] has provided good measurement steps to hide the password or PIN codes by a bystander. Their presented work focuses on hiding the messaging text like chat from a shoulder surfer. The researchers think that text messages in public places should be written in the user’s personal handwriting since it’s not easy for everyone to read other handwritten words. It replaces the standard printing font on mobile devices with user-personal handwriting. The user study shows that there was variation between the times of reading the user’s handwriting and reading the text written in the handwriting of the different users.

Katharina Krombholz et al. [

110] proposed a technique to avoid password attacks for the MPAS in public areas. The idea is to make the security of the PINS by applying force to the digits which are either bold or underlined, e.g., 1

2 1

4 as shown in the

Figure 5. It also gives vibration feedback as the user enters any PIN with force authentication. This scheme is easy and simple, as most users use PIN authentication to log in.

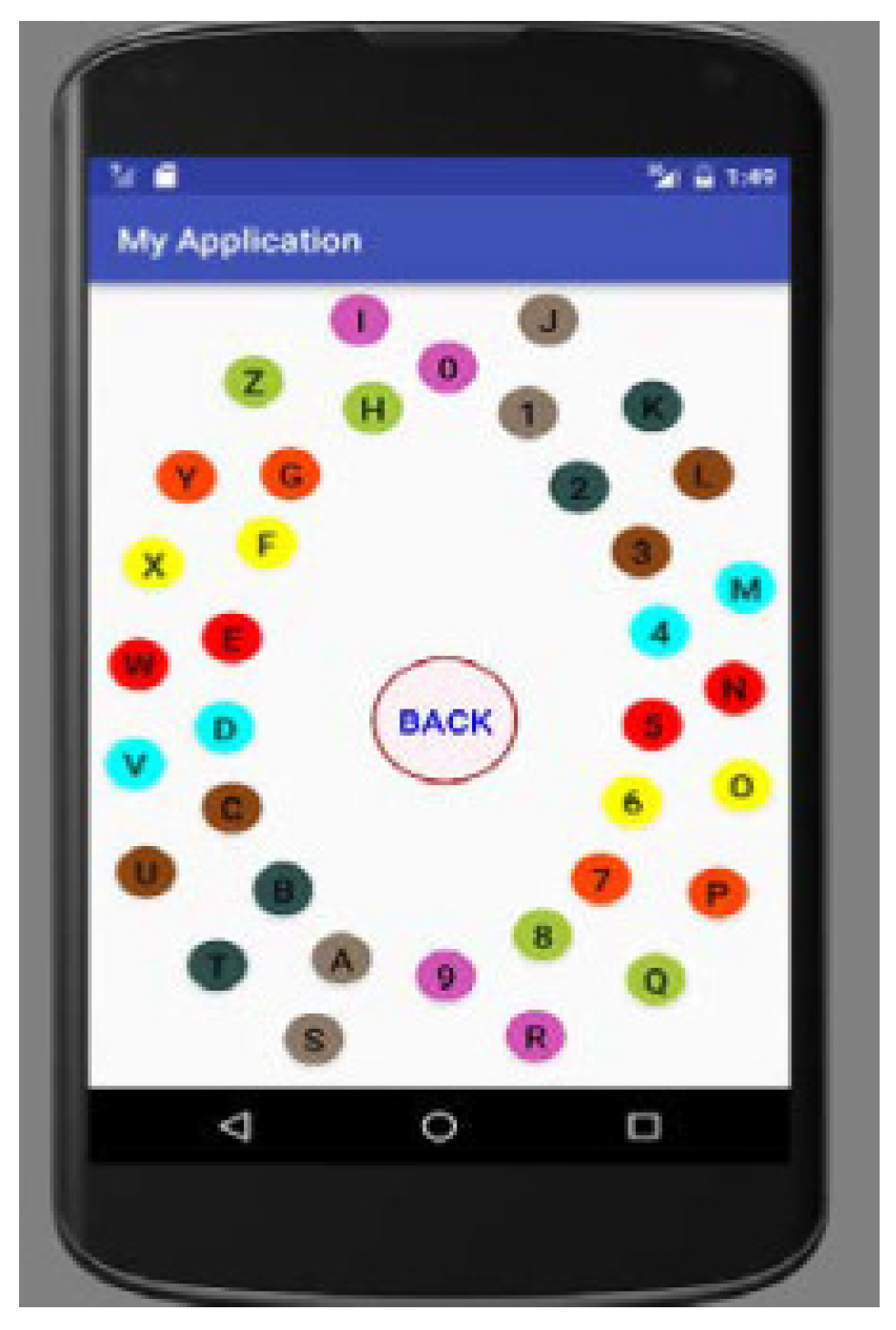

Nilesh Chakraborty et al. [

111] designed a system that lets the user choose his/her password, which will be of four characters, which can be both alphabetically and numerically. The characters in the password can also be repeated, e.g., ST4T, AR2A. MobSecure has 36 nodes that have all alphabets (A-Z) and numeric characters (

) (

Figure 6). They are arranged in a circular pattern named orbit, so there are two orbits, inner and outer. All nodes are colored, and two adjacent nodes of both orbits are colored the same and named as sister nodes. The authentication process consists of two stages. In the first stage, the user is challenged, in which the user can hear a number through earphones, which can be random and consist of numbers between 0 to 17 or 0 to 17. The second stage entails the user has to select his/her number from the inner or outer orbit. Compared to existing approaches, the proposed process was reviewed based on usability and security perspectives.

In comparison to textual and numerical PINs, the 3X3 pattern lock scheme is standard. Due to a lack of instructions on complex drawing rules, users prefer to use fundamental patterns, making them vulnerable to attacks. Sukanya et al. [

112] proposed a mobile unlocking application that uses a pattern formation with a PassO circular grid layout instead of a 3X3 grid. Using a mobile device, they examined the Passo patterns obtained from 32 participants in a lab study. According to the findings, the average duration of patterns was reduced by 25.47% in the mobile scenario. As a result, participants developed shorter patterns in real-life situations for ease of use and recall.

Vincenzo Gattulli et al. [

113] explores a method for continuous user authentication on smartphones by leveraging touch events and human activities. The authors utilize the H-MOG dataset to analyze user behavior while reading documents on a smartphone, focusing on the combination of touch events and sensor data (accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer). They propose a feature extraction method that includes the Signal Vector Magnitude and evaluate various machine learning models, including 1-class and 2-class SVMs, achieving high accuracy rates (98.9%) and F1-scores (99.4%). The study emphasizes the importance of continuous authentication to enhance smartphone security, particularly against unauthorized access during passive activities like reading.

The research [

114] suggested a scoping review by Finnegan et al. that examines the current state of behavioral biometrics in user authentication and demographic characteristic detection, particularly in the context of measuring screen time on mobile devices. The review systematically analyzes 122 studies that utilize built-in sensors on smartphones and tablets for user authentication through methods such as motion behavior, touch dynamics, and keystroke dynamics. The findings indicate that touch gestures and movement are the most commonly used biometric methods, with a significant reliance on accelerometer and touch data streams. However, the overall quality of the studies is low, highlighting a need for more rigorous research, especially involving child populations, to effectively apply behavioral biometrics in public health contexts.

4.4.1. Opportunity

The issue of compatibility is a major worry for the scientific community. Some of the authentication methods proposed in the literature are incompatible with other smartphone platforms, which poses a problem. An ideal authentication system must be compatible with various systems to be widely used. No matter how powerful an authentication system is, its use will be limited if it only supports a few platforms. As a result, excluding a certain group of users from the authentication process reduces its overall efficiency.

Table 5 summarizes the touch screen authentication schemes.

4.5. Gaze-Based Authentication Techniques

Gaze is an appealing and vital communication methodology that gives the client an instinctive, without-hand method for connection. Traditional techniques like touch and clicking have usability advantages. Still, the gaze is more protective against observation attacks due to its subtlety and can be implemented to existing mobile pattern lock schemes with no additional changes to the interface[

119]. Gaze data can be used in numerous viewpoints, for example, gadget verification, diversion plan, gadget controlling, client conduct examination, etc. [

120]. Gaze as features of input [

121] have empowered different look-based verification strategies, in the case of shoulder surfing, that can be grouped crosswise over common three classes [

122] i.e., gaze pin-based, gaze gesture-based, and gaze pursuit based authentication.

Mohamed Khamis et al. [

123] proposed GazeTouchPass, a multimodal verification conspire in which clients characterize four images; every single one must be typed in either utilizing touch (a digit somewhere in the range of 0 and 9) or utilizing gaze(looking to one side and one side). Successive look contributions to a similar heading would then be isolated by a gaze to the front. GazeTouchPass accomplishes a harmony between security and convenience, with low confirmation times and high observation resistance.

C Katsini et al. [

124], developed a two-step process for evaluating the quality of client-made graphical passwords dependent on the eye-gaze behavior during password formation. In the first step, the user gaze patterns are determined, represented by the exceptional obsessions in each area of interest (AOI) and the all-out obsession length per AOI. Second, the gaze-based entropy of the user is determined. A feasibility study was conducted to determine password robustness. Results uncovered a solid positive relationship between the quality of the made passwords and the gazed-based entropy.

Yasmeen Abdrabou et al. [

125] presented and evaluated six MPAS using gaze, gestures, and multimodal combinations and found that gaze offers a good balance between utility and protection, is highly protected in case of shoulder surfing attack, needs minimum time for authentication, and is barely vulnerable to mistakes. Experimental results show a 70% improvement over previous authentication time work due mainly to improved sensors and visual computing schemes.

Narishige et al. [

126], from the peak velocity of the gaze, proposed a scheme for predicting the target gaze point coordinates. The polynomial approximation of the peak velocity and the distance to the target was used to model the prediction estimation function. Furthermore, this modeling result was experimentally accurate using data from BioEye 2015’s RAN task. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that this modeling outcome had individual variations, and the application of individual certification was described.

[

127] an eye gaze-driven metric was proposed focusing on the hotspot vs. non-hotspot image sections for elegantly measuring the intensity of graphical passwords created by the users by evaluating eye gaze actions of the users during password formation. For testing the feasibility, An eye-tracking study (n=42) was conducted, i.e., the presence of link within the metric that is proposed and the intensity of passwords created by users, where a graphical password is constructed by the user using a customized image which activates declarative memory (familiar image) vs. an image demonstrating (generic image).

Omer Namnakani [

128] introduces GazeCast, a novel system that utilizes users’ handheld mobile devices to facilitate gaze-based interaction with public displays. The authors highlight the limitations of traditional gaze interaction methods, which often rely on stationary or cumbersome eye trackers. Through a user study involving 20 participants, they compared GazeCast with a standard webcam setup and found that while GazeCast required more time and physical effort, it offered higher accuracy and flexible positioning. The study demonstrated that GazeCast could enhance user experience by allowing spontaneous, calibration-free interactions while also addressing privacy concerns by enabling local processing of gaze data on users’ devices. They concludes by discussing the potential applications of GazeCast in various public settings and the importance of further research to optimize its usability.

Table 6 summarizes the gaze-based authentication schemes

4.5.1. Opportunity

To be completely implicit and work without the user’s participation, gaze-based security solutions require highly accurate gaze estimates. Calibration is required to gather highly accurate gaze data [109]. Eye trackers used to require users to be extremely still, even requiring them to utilize chin rests [33]. While current eye trackers allow users to roam around to some extent, they frequently require recalibration whenever the user’s or setup’s state changes dramatically.

However, calibration adds a layer of complexity to the contact process, making it feel boring, awkward, and time-consuming [164]. Many studies have made calibration more implicit than explicit, such as including it in the engagement process while reading text or viewing videos. Previous research on implicit calibration focused on generic use cases rather than implicit authentication. This leaves room for future research into how to adjust implicit authentication to improve its performance. This necessitates first comprehending the implicit gaze-based authentication better trade between calibration time and accuracy.

4.6. Graphical Passwords Authentication

Initially, any MPAS necessitates acceptance of a security system that is simple, versatile, and adaptable. The graphical information-based MPAS is among the schemes of authentication that depend on the remembrance of protected passwords [

131]. Researchers have found that graphical passwords are more memorable than textual alphanumeric passwords [

132]. Organizations or different social networking websites force users to adopt a strong password policy, which requires users to select hard passwords that are less vulnerable to discovery. Nevertheless, on the other hand, it increases the burden on the users to remember those hard passwords [

133]. The user tends to use easy passwords for all systems, increasing the security risk, as if one hack, all systems will be hacked [

134]. If people choose easy passwords, it is easy to find through automated search [

135]. The primary debate regarding graphical passwords is that they reduce the overhead load of user memory to remember hard textual passwords, as studies have proved that humans memorize graphics and images better than text [

136]. Because of this memorability advantage, users are keen for graphical secret key [

137].

Recognition-based, pure recall-based, and cued-recall graphical passwords are the three types of graphical passwords [

138]. The images selected correctly during registration are recognized in a recognition-based authentication scheme. The procedure, however, is possibly interrupted by phishing attacks that mislead users from capturing screenshots of their passwords. Another drawback to this scheme is the discovery of some pre-selected images that involve scanning several images regarding the password, making the operation time-consuming [

139]. Users must recreate or draw something because the password depends on a pure-recall authentication scheme. When a stylus is not used, the disadvantages of schemes depending on recognition are fixed by the schemes depending on pure-recall; however, they are vulnerable to misconceptions [

140]. Since they automatically mimic human inputs, the systems that depend on pure recall are slightly exposed to social engineering, dictionaries, and brute-force rather than text-based passwords. Cued recall authentication involves the user seeing a specified picture and clicking on one or more predetermined locations in a prescribed sequence. In contrast to the complicated and real-world segment, preconceived click objects need clear, artificial images, such as cartoon-like images. The user is susceptible to selecting the image’s hot spot, which would be easy for a hacker to guess [

141].

Graphical passwords are widely used in search of a remedy for shoulder surfing attacks. They are easy-to-remember and hard-to-crack passwords as pattern recognition of bio-metric passwords while drawing the graphical passwords has been considered to provide better security [

142].

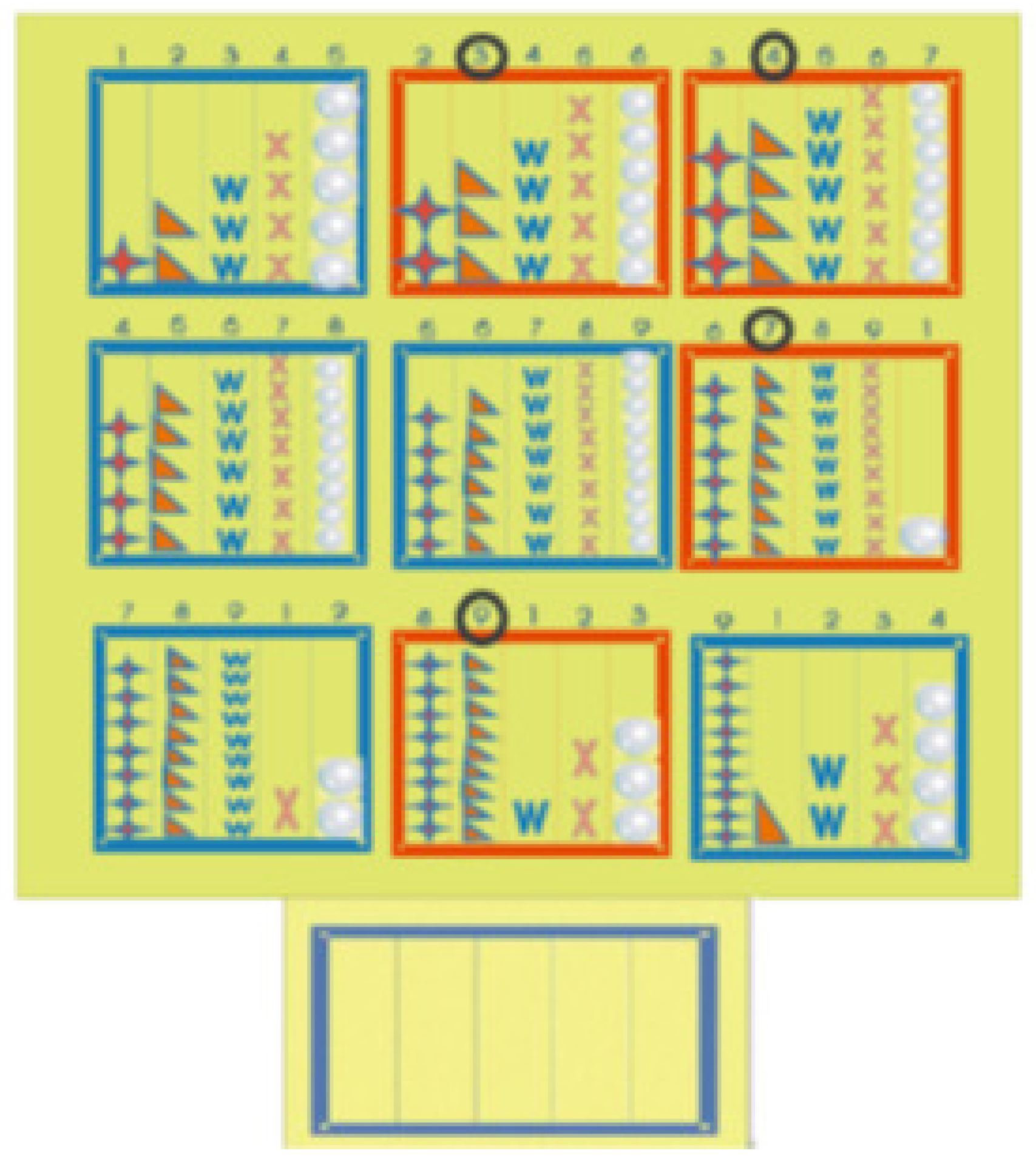

A Technique named pass matrix [

143], which consists of four modules, namely, image discretization, horizontal and vertical axis module, login indicator generator module, and a communication module, gives a broad space for a password to the user. This technique avoids shoulder surfing and smudge attacks. The login indicator will generate a new password for every session; the users will use a dynamic pointer to identify the position of their password rather than clicking on the password directly. The user images are divided into a

grid; the smaller the image, the larger the password space. Each time the user logs in, he will touch the screen to see the indicator, which can also be referred to as a session password shown in

Figure 7. The given indicator will be converted into an image with horizontal and vertical axes from A to G and 1 to 11 characters representing a

grid, respectively, shown in

Figure 7. The module for password verification confirms the arrangement within the pass square for each image. If the arrangement is accurate in every image, then the user can log into the system.

Techniques depend on click, known as passport [

144], is one of the earlier techniques in graphical passwords. Still, in this scheme, security analysis found that its simple geometric pattern with images is vulnerable to hotspots [

145,

146,

147].

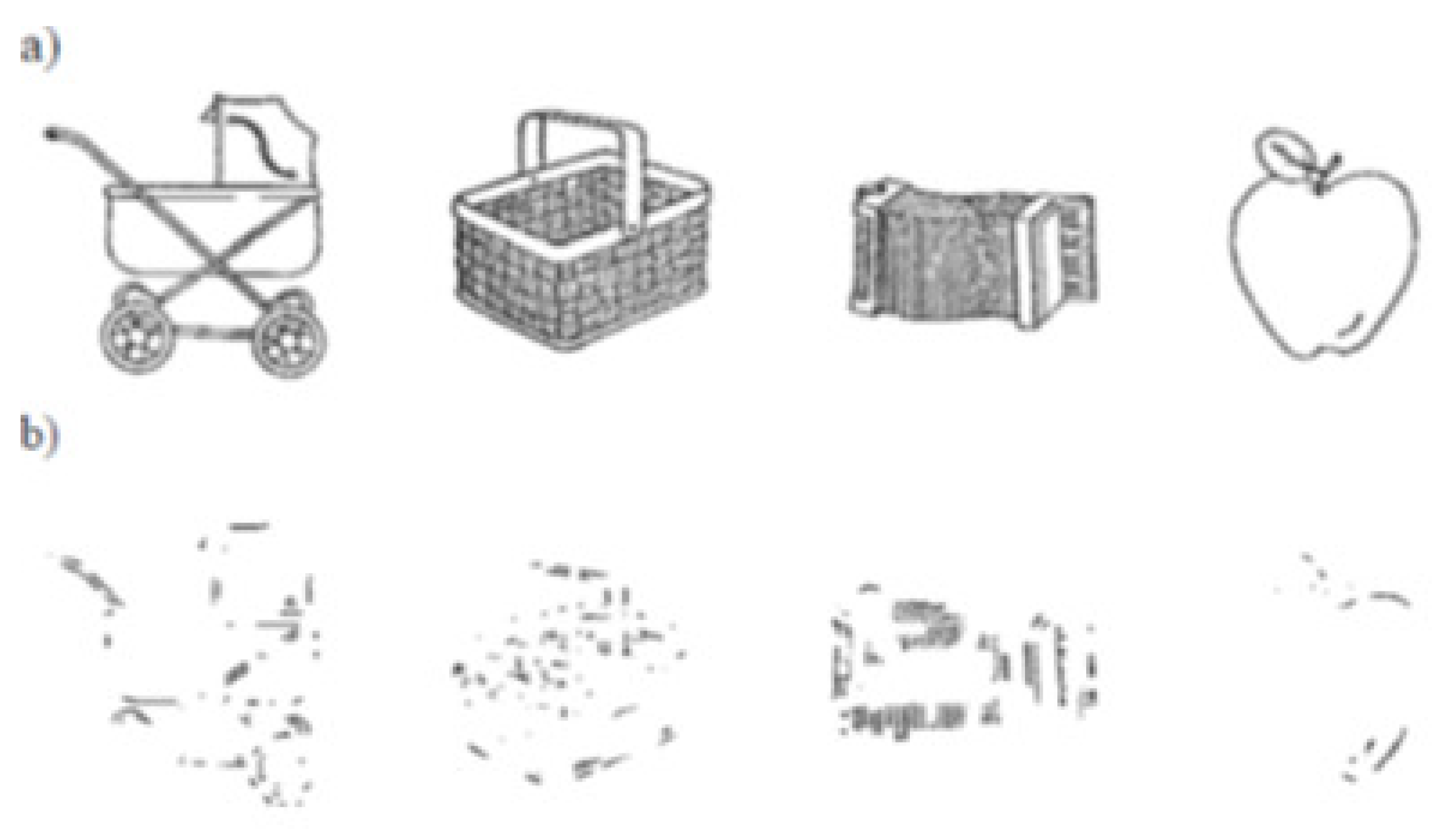

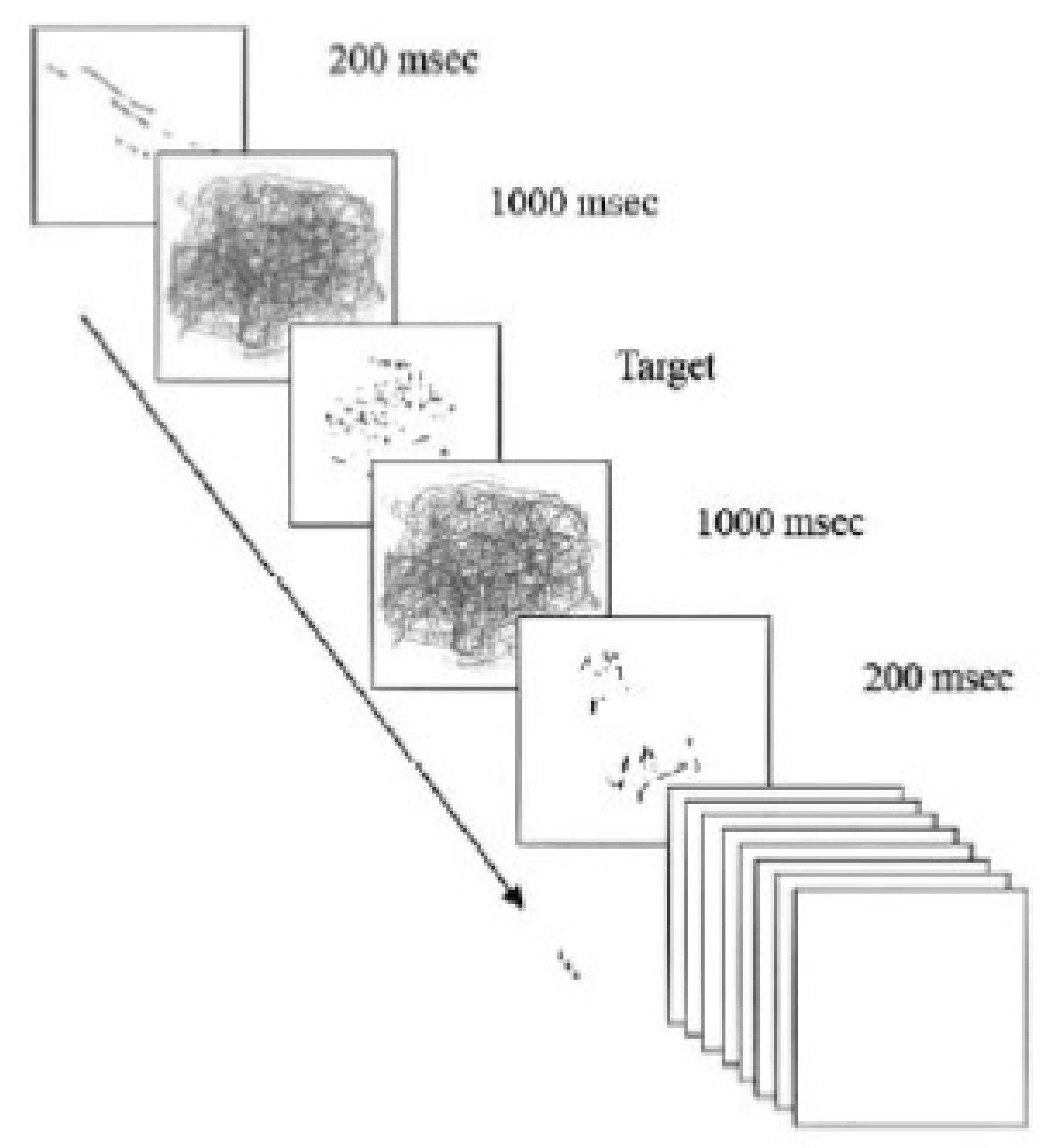

In their research, Ashley A. Cain et al. [

148] concentrate on a series of graphics based on faster authentication while choosing the right images in 14 seconds. There are many distracting images from which the user has to touch or click the four target images. This series of images comprises low-grade line drawings of daily life objects. Low-quality or distorted unclear images are used to support cognitive object recognition. The system uses the Recognition by Components, which tells us that 3D objects can be recognized without the viewpoint of curving, linearity, shape, etc. These graphics are vague and unclear, making them hardly identifiable objects in

Figure 8.

At the same time, these nebulous graphics can be quickly recognized if the user is acquainted with the original object. Tainted images are shown on the screen for a very small fraction of a second, 200 milliseconds to be precise, which is fast, but the authentic user can easily cope with it. The degraded images overlap to create a mask that stops for one second and comes after each degraded image shown in

Figure 9. These degraded pictures are shown randomly in between 7 distracting masks. The correct target image is not shown initially to allow the user time to fine-tune the streaming speed.

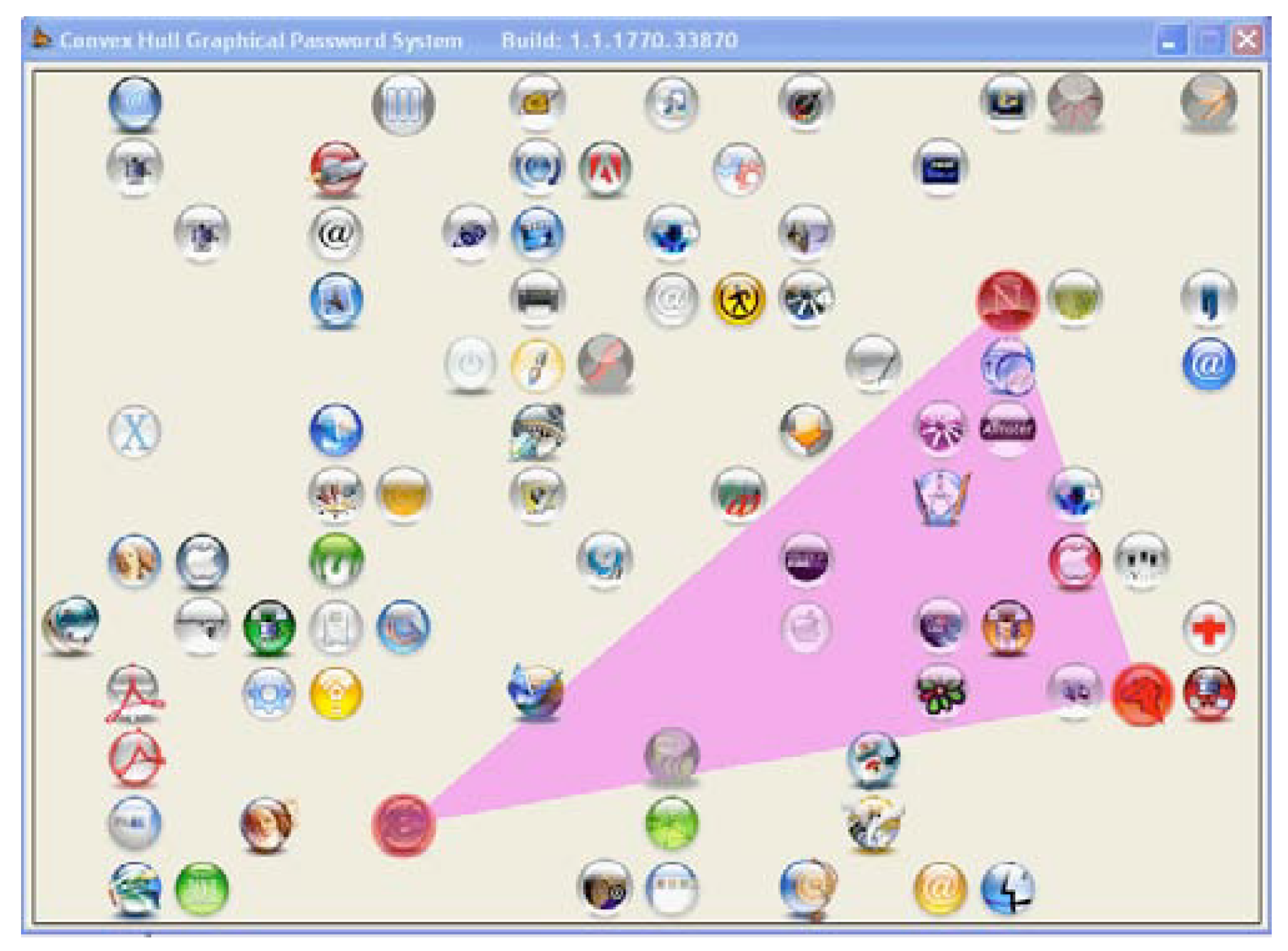

A graphical MPAS known as Convex Hall Click Scheme [

149] is based on a round of image selection to get the authentication as shown in

Figure 10. The convex hall has pass icons that can be clicked without clicking the user’s actual password icons.

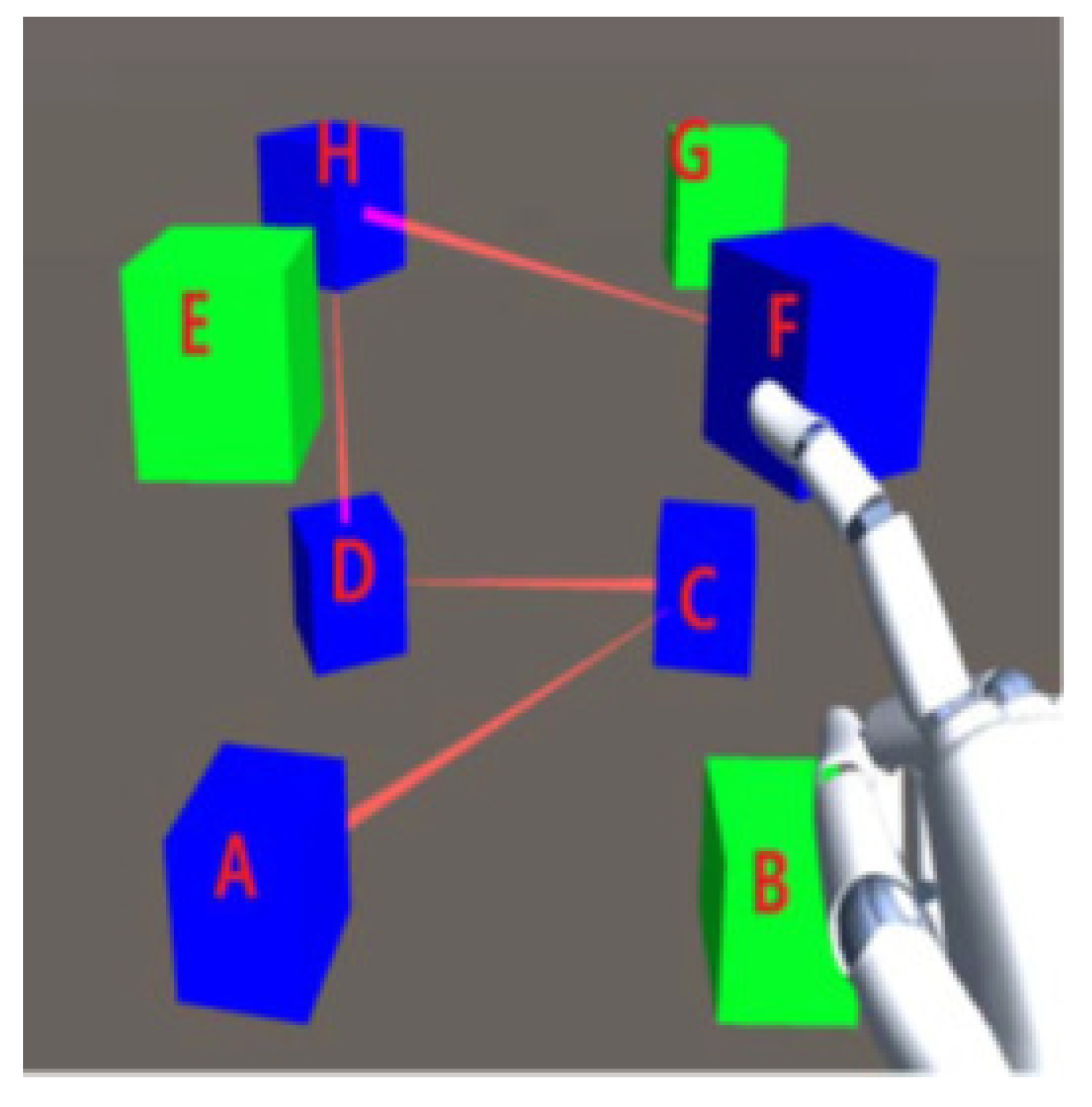

3D graphical passwords have introduced a new methodology for user authentication on mobile devices. Unity 3D package [

150] is used to create the 3D graphical password and a device named Leap motion with the help of a scripting tool c#, which allows user interaction with mobile devices. The 3D graphical methodology is shaped like a cube matrix, consisting of nodes and edges that construct the user password. This cube has eight green cubes of the same structure; the leap can see the user’s hand movement. The activity by the user’s hand within the observation area, the 3D virtual hand will represent the user’s hand movement, which permits user interaction with objects as shown in

Figure 11. The positions of the cube can be randomly set. When the user touches any cube, its state visibly changes. The arrangement of the being touched is meant to record and pass through an algorithm to create a unique password for every login.

Irfan et al. [

151] suggested a graphical password scheme based on text. Out of sixteen random images, the user selects five images. The random images shown are a mixture of graphical and text-based images in password creation. This scheme’s login process consists of a

grid in which the last vertical grid shifts continuously. If the selected moving grid image is matched with the other two selected static grid images, the user can tap the image to activate the unit. The drawback of this scheme is the waiting time for the synchronization of images, which results in increased login time.

The research title "Securing Access to Internet of Medical Things Using a Graphical-Password-Based User Authentication Scheme" by Khan et al.[

152] proposes a novel graphical password authentication method aimed at enhancing security in the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT). The authors highlight the growing need for secure user authentication in digital healthcare services and address the limitations of traditional text-based passwords. The proposed scheme incorporates multiple factors, including simple arithmetic operations, machine learning for hand gesture recognition, and medical images for recall, to create a user-friendly and memorable authentication process. The effectiveness of the method was evaluated using the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ), which showed significant improvements in system quality, information quality, and interface quality compared to conventional PIN and pattern-based techniques. The study concludes that the proposed graphical authentication scheme is a promising solution for improving security and usability in IoMT applications.

[

153] unique solution uses color as a memory cue to improve password memorability and security. A five-week longitudinal study looked at over 3000 passwords established, learned, and recalled. Our findings indicate that adding color to passwords can improve both memorability and security. Allowing users to select their own password colors instead than pre-selected ones promotes personalization and important memory cues. Color increased password entropy, adding another layer of security. These discoveries have practical consequences for academics and practitioners, potentially improving password security and reducing financial damages from breaches.

Table 7 summarizes the graphical authentication schemes.

4.6.1. Opportunity

A countermeasure could be developing a nonvisible user graphical password authentication mechanism. Graphical elements are usually prominent. As a result, when compared to text-based passwords, graphical passwords may be more vulnerable under certain circumstances. An image is larger than the text, assuming the graphical password using a predefined picture selection method; however, a shoulder surfing attacker may have problems acquiring the original password from a long distance with a text-based password. As a result, a shoulder surfing attacker may obtain the password from a considerable distance. As a result, one or more authentication measures must be used in conjunction with a graphical password.

4.7. Color Based Authentication

Color MPAS has been proposed as an alternative to textual and graphical image selection passwords. A method for detecting tampered regions on images is color image authentication [

156].

Manish M. Potey et al. [

157] proposed a technique whose registration process begins with entering the information submitted by the user, such as username, password, contact number, etc. Then, the user has to choose three colors from the colors grid arbitrarily, and the order of these colors is important, so the user has to remember the order in which he/she entered the colors. After this user has to click on three shades: white, black, and gray, this order is also to be memorized by the user, which will also be needed at the time of authentication. For authentication, the user must enter his/her username and then offer the same order of the shade of the three basic shades, white, black, and gray. This is the first step. If correct, the user has to choose the numbers shown on the colors grid, which signify the column number of the corresponding numeral grid. Those three cells have white, black, and gray in the numeral grid. Each corresponding row is recognized per the shade order selected in the registration process. Then the user has to select the three-digit numeric present in the numeral grid by applying the same procedure using the identified row. The user has to then append the three numbers from the numeral grid for a single time-made password. Then, the same procedure must be rerun for the second and third colors. After completing nine colors, the submit button is to be pressed, and if all of the combinations and the final digit are correct, authentication is granted.

Aayush Dilipku mar Jain et al. [

158] proposed a system of authentication using graphical and color systems to overcome the attack of shoulder surfing. This system provides security against shoulder surfing and key logger attacks. By combining the color sector and numeric password, the user can easily authenticate to the system.

Chiang et al. [

159] proposed a multi-layered drawing unlock scheme that, when compared to pattern unlock, significantly expands the pattern space. More complex patterns can be formed using multiple layers and warp cells at the grid’s corners. When a warp cell is touched while entering a pattern, for example, the second layer grid appears, concealing the authentic grid layer for proceeding with the pattern entry.

[

160] proposed ColorSnakes, a software-based authentication system that protects in case of shoulder attack and, to a minimal level, attacks involving the videos. A ColorSnakes PIN begins with a single colored digit and ends with four digits. Users draw an arc from the first colored digit to their PIN. The users enter their PIN; various colored entrap pathways intend to be generated simultaneously among the starting colored digits, mimicking the alternative pathway to conceal the input. To prevent smudge attacks, the underlying numbers grid is created randomly after each successful input.

[

153] introduced unique solution uses color as a memory cue to improve password memorability and security. A five-week longitudinal study looked at over 3000 passwords established, learned, and recalled. Our findings indicate that adding color to passwords can improve both memorability and security. Allowing users to select their own password colors instead than pre-selected ones promotes personalization and important memory cues. Color increased password entropy, adding another layer of security. These discoveries have practical consequences for academics and practitioners, potentially improving password security and reducing financial damages from breaches.

[

161] advances color-based authentication by making the verification process more difficult, addressing flaws in textual authentication and improving security at the authentication layer. This color-based authentication technique has the potential to replace textual authentication and is suitable for sensitive data sectors like medical and banking organizations. This improves the authentication layer for websites that are prone to hacking, including brute force and dictionary attacks. This study can be used to the development process as well as systems. Color-based authentication can enhance password security.

Table 8 summarizes the Color-based authentication schemes.

4.7.1. Opportunity

Some authentication schemes use color combinations that may confuse the user when getting used to the system. As color-blind people have difficulty identifying colors, the schemes must be user-friendly.

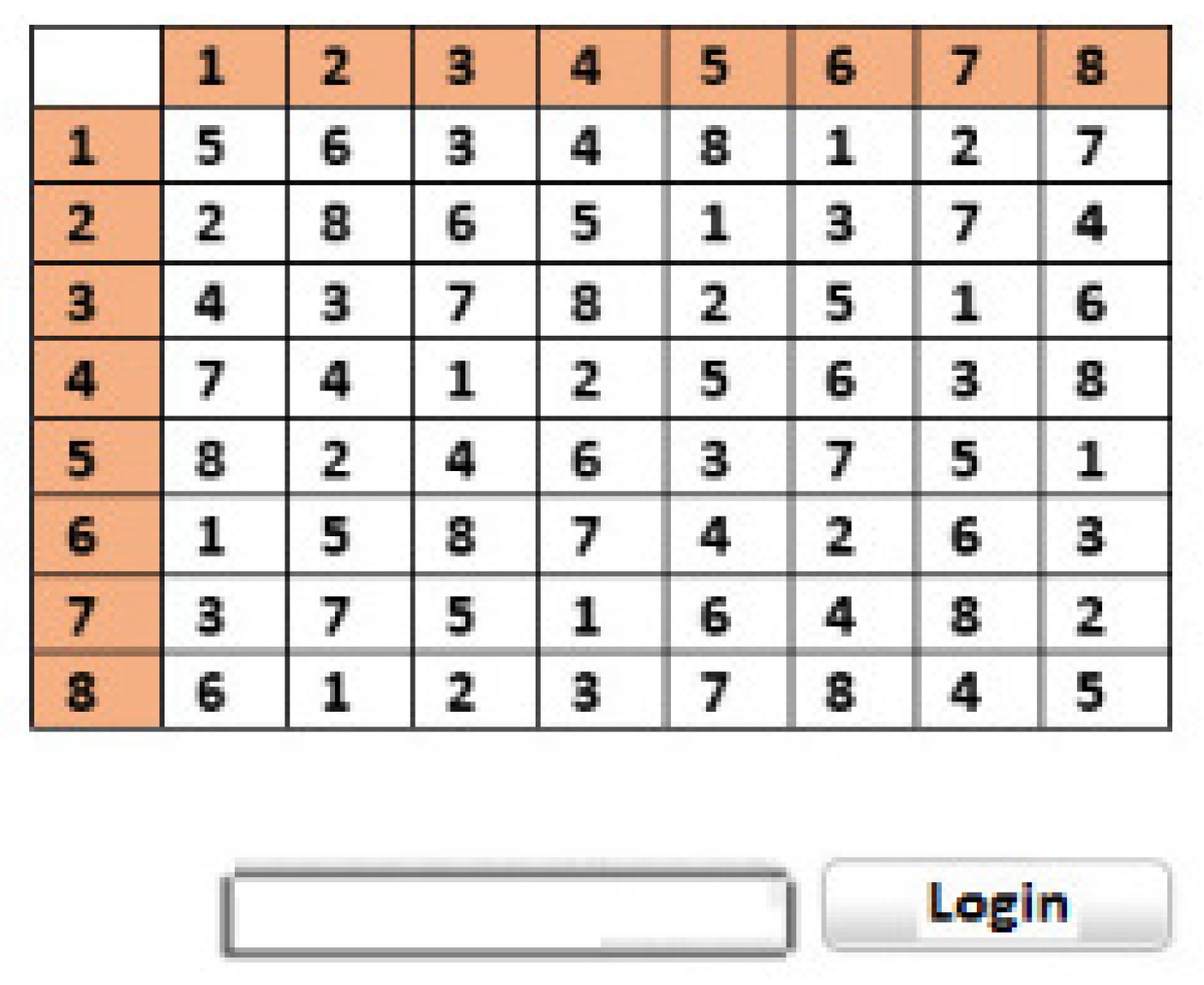

4.8. Processed Authentication and Random Password

Authentication granted through textual passwords is the most common way to log in. Still, a lot of vulnerability is attached to this, so graphical passwords are used to prevent them. Sanket et al. [

163] proposed a system of two methodologies against these attacks. In the first method, Pair Based Authentication, the user must choose a password of 8 minimum characters. It is referred to as a secret password as it will never be entered but will help make and enter the actual password at that session. When the user starts the login process, the system presents a

grid shown in

Figure 12 having session passwords made according to the hidden password. These session passwords are combinations of alphabets, numbers, special characters, and different symbols and change every session.

When the grid is shown to the user, the user considers the two letters of his/her hidden password from the grid, and then the intersection of those two hidden passwords is c, which is the real session password. For example, in

Figure 12, the two hidden passwords are T and @. These two represent a row and column; their intersection is the letter L, which is the session password the user must enter. The password chosen at the time of registration should be an even number of characters so that each pair can generate an intersecting session password. The second scheme is the hybrid authentication of the user during registration, which includes a group of colors in which he/she has to select the ratings of the colors. The colors can have similar ratings, which the user has to remember. When the user wants to log in, the system uses an

grid with random numbers from 1 to 8. 4 pairs of colors are shown to the user. Each pair represents a row and a column. The user considers his/her rating of the color and then concentrates on the crisscrossing number that intersects after combining the two numbers he/she got from the colors. This number would be the session password the user enters for authentication.

The use of extra equipment to strengthen the MPAS’s security and eliminate shoulder surfing attacks has increased. If the equipment is inexpensive and does not pose any difficulty to the users, it will be more acceptable and practical. Sami Ullah Afzal et al. [

164] proposed an MPAS that uses a headphone and a graphical password to stop any chance of a shoulder surfing attack. The user listens to the voice of the server telling a random number which is used in a formula to process the password, which is then entered graphically using a numeric type graphic pad as shown in

Figure 13. This graphic pad has many symbols, which is why the user clicking on the user to enter the password will never let the shoulder surfing attacker know what password was typed. Then, for the next authentication, the server voice changes the number, and the number pad also changes its numbering sequence along with the symbols and their orders. These are the proposed techniques addressing the issue of shoulder surfing attacks and duress attacks. This problem of shoulder surfing and duress attacks is an increasing one and poses threats day by day to users around the world while authenticating their precious property or assets.

Hussain Alsaiari et al. [

30] proposed a technique by combining the graphical password and a one-time password system. Users register with a unique username and draw a shape on a

pattern lock. In the login process, the user enters his username and draws a pattern; if this given data is correct, then a 4*4 grid of images appears, containing two user-pass Images and other distracting images to divert the attention of a bystander or a hacker. Codes associated with the correct images are automatically generated. The user has to recognize the correct images in his brain and does not have to click on the image but enter the code related to the correct pass image. In this way, the shoulder surfer does not know which images were selected. This technique provides a good solution against shoulder surfing attacks common in public places.

Sami Ullah Afzal [

165] proposed a technique where the user needs to process his PIN code whenever he login to the system. The user has to process (mathematical operation) his PIN code digits with the server’s given numbers during every session.

The unique technique proposed in [

166] combines the fifth element, machine learning, and behavioral authentication. The sixth factor prevents shoulder surfing as the arithmetic operation is hidden by a hand put on the screen. When a user places their palm on the screen to hide the code, the system displays the arithmetic operation and performs the calculation in their mind. The user is shown a public pattern, but the machine learns their touch dynamics and postures, including lying. The focus has been on providing an additional layer of defense to save users’ authentication processes.

Table 9 summarizes the process authentication schemes.

4.8.1. Opportunity

Process password authenticating schemes provide an extra layer of security. All authentication schemes discussed under this category require the user to log in with new credentials whenever he/she logs in. This provides good security against attacks such as guessing and shoulder surfing attacks. The user must process his/her password using the given server numbers. This processing should be simple enough not to require extra time to authenticate.

4.9. Augmented Reality Authentication

Augmented reality is a technique that eradicates the attacks like shoulder surfing. A device is used in which the user can only see what is on the screen or which keys are shown on the keyboard with different layouts. Other people nearby, which can be potentially dangerous, cannot see what will be shown on the screen or the typed password [

170]. As the number of augmented applications grows, one factor that has gone unnoticed is the privacy and protection of augmented systems. User behavior in a virtual reality environment differs significantly from that of other digital devices such as smartphones or computers [

171].

Cloaking note [

172] a desktop interface for writing subtly, i.e., to misdirect the observer’s attention from the authentic text. It is used to write personal messages in crowded places that misdirect the attackers from the real action.

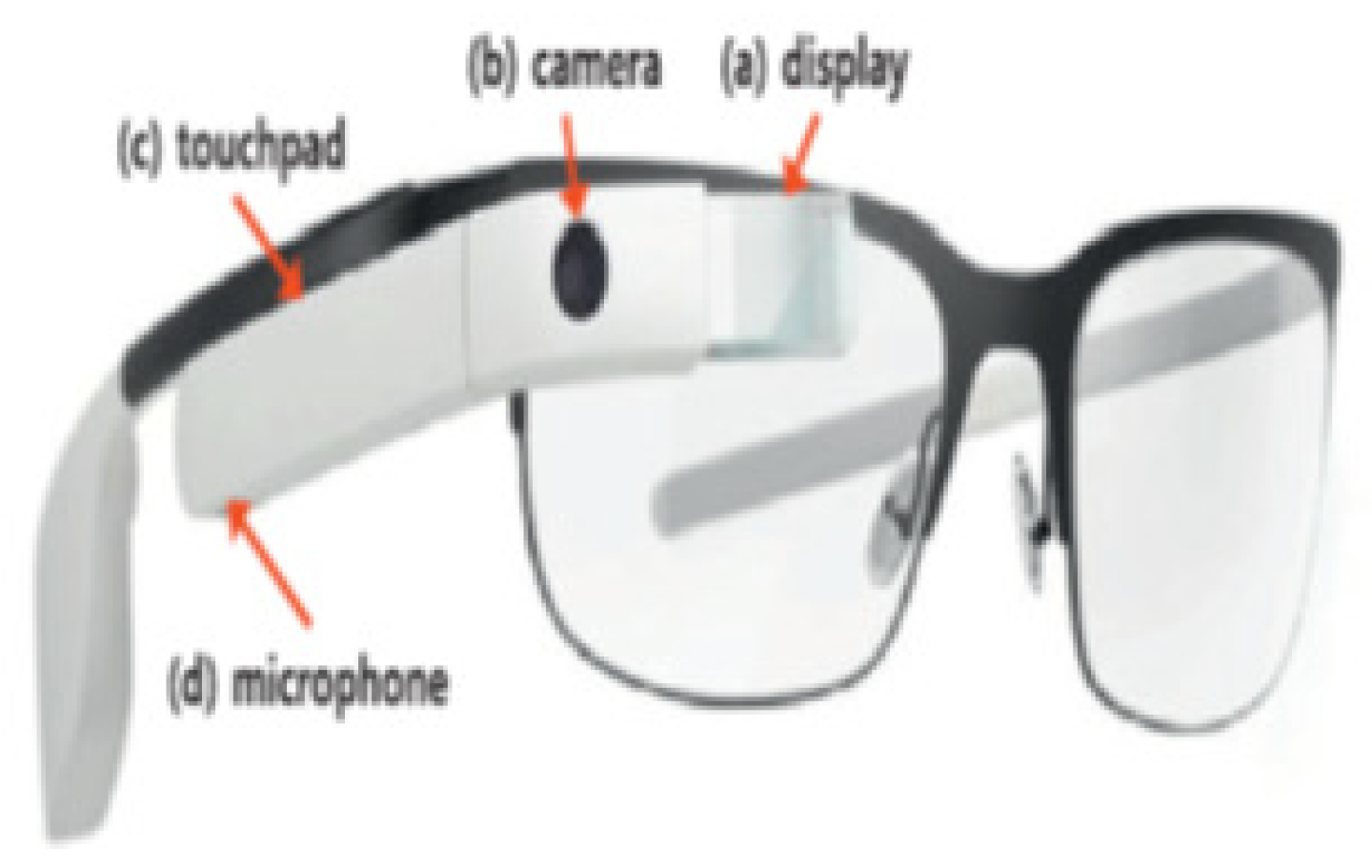

Hwajeong Seo et al. [

173] proposed a system that uses a particular device, i.e., Google Glass (

Figure 14), which deals with the concept of augmented reality and contains many properties as it can interact with the user based on voice, touch, and gestures. This technique is also beneficial when using an ATM or credit card in an open environment. The user performs the PIN entry using Google Glass, after which the user types the password and then chooses the existing operation.

Ruide Zhang et al. [

174] proposed a system based on getting authenticated with an augmented reality display. The proposed system uses an augmented reality headset and a controlling device. The display is given through the headset, and the gesture device is responsible for recording the gestures and input. The user has to wear the device to input any gestures or data. After wearing it, the user has to execute numerous taps to record a pattern that will be a signature for that user and is named as labeled sensor data. A model that corresponds to a particular user is created. Then the user has to set a password, after which the headset will provide a virtual keyboard for the operator to enter the password. This virtual keyboard will have a numeric pad with eight keys from zero to seven, among which the user must set or insert the password. This system works on the principle it is quite effective in resisting shoulder surfing attacks.

Ilesanmi Olade et al. [

175] paid central attention to the scheme of protection required to approve a user’s identity utilizing a variety of familiar characters tics that distinguish the user from other users in a virtual and augmented reality environment. Identifying the task comes first, followed by identifying the individual in the identification process. Machine learning was used to test 65,241 datasets regarding the movements of hands, head, and eyes to develop a continuous biometric authentication system and achieved an accuracy of 98.6%.

[

176] introduced GazePair, a new pairing system that enhances previous local pairing strategies with an efficient and user-friendly protocol. GazePair employs eye tracking and a spoken key sequence cue (KSC) to generate 64-bit symmetric encryption keys that are identical and separately generated. GazePair improves pairing success rates and timeframes compared to current approaches. Additionally, it was also demonstrate that GazePair can support several users. Finally, GazePair can be used on any Mixed Reality (MR) device with eye gaze tracking.

The work [

177] aims to create a non-contact authentication system employing ErPR epochs in an AR environment. Thirty participants were offered a quick visual presentation with familiar and unfamiliar human photos. ErPR was compared to Event-related Potential (ERP). ERP and ErPR amplitudes for familiar faces were substantially higher than those for strangers. The ERP-based authentication system achieved flawless accuracy using a linear support vector machine classifier. A quadratic discriminant analysis classifier trained on ErPR characteristics achieved 97% accuracy and had minimal false acceptance (0.03) and false rejection (0.03) rates. ERP and ErPR amplitudes had correlation values ranging from 0.452 to 0.829, and Bland-Altman graphs indicated good agreement.

Table 10 summarizes the augmented authentication schemes.

4.9.1. Opportunity

Augmented devices provide a stronger shield against attacks but are way expensive [

173]. Users need to carry an extra device for authentication, which is sometimes a problem. If the extra device is lost or stolen, then authentication using the above-mentioned schemes in this section is impossible. So researchers should find a solution to get rid of the extra or augmented device, which should be small enough to carry.