1. Introduction

Medical glue embolization, first used in 1975, is permanent and instantaneous, but can be toxic if infused into the intravascular lumen, making it suitable for specialized centers [

1]. Intermediate-length cyanoacrylate adhesives like n-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) were the first product to be broadly used in medicine for closing cutaneous wounds, and now are the mostly utilized to permanently occlude vascular anomalies, such as brain and spinal vascular malformations [

2], as well as in portal vein embolization [

3], preoperative renal tumor embolization, embolization of endoleaks through endoprostheses and embolization for bleeding control [

4].

Histoacryl® (B/Braun, Tuttlingen, Germany) or N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate glue is the most commonly used. It has replaced isobutyl cyanoacrylate and is also marketed under the name Trufill® (Cordis, Miami Lakes, Florida). The lack of formal acknowledgment for Histoacryl®'s off-label use in endovascular therapy has garnered attention in recent years, giving rise to serious legal issues. Because of this, a brand-new acrylic glue called Glubran 2® (GEM SRL, Viareggio, Italy) was introduced to the market in 2000, wherein N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and metacryloxysulpholane (MS) are mixed to create a more flexible polymer with a milder exothermic reaction (45°C) that causes less inflammation and histotoxicity [

5,

6,

7]. Metacryloxysulpholane also gives surgical Glubran 2 a significant anti-inflammatory effect. The addition of MS to NBCA yielded a glue complying with European regulations, hence receiving CE certification for internal and endovascular use. Lipiodol is usually added to NBCA for visibility under fluoroscopic control [

8,

9,

10], and the polymerization time can be modulated by changing the lipiodol to NBCA ratio [

11,

12,

13].

Further studies showed that ethanol addition can accelerate the polymerization time [

14,

15,

16]. Kawai et al. (2012) discovered that adding ethanol to the mixture of NBCA plus lipiodol had the impact of modifying the structure of NBCA polymerization [

15]. They investigated the properties of NLE (NBCA+Lipiodol+Ethanol) mixture with increasing ratios of aneurysm packing in a swine model and discovered that high ethanol ratios caused solid-like qualities of the mixture with strong occlusive ability and little adherence to the microcatheter. Over the last years, new embolic agents have been also developed with improved handling characteristics and penetration in artero-venous malformations (AVMs) [

17]. Among these non-adhesive liquid embolic materials, so-called gelling solutions, some are now largely used for endovascular treatments [

18]. Gelling solutions are polymers in solvents that solidify in situ when water replaces the solvent. The first gelling solution, described by Taki in 1990, was made by ethylene-vinyl-alcohol copolymer (EVOH) in a dimethyl-sulphoxide (DMSO) suspension [

19]. These non-adhesive liquid embolic materials, easily injected through a microcatheter, dissolve in aqueous solutions like blood, precipitating a spongy polymer cast [

20,

21], but endovascular DMSO shows an angio- and neurotoxic effect [

22,

23,

24]. Still, the inflammatory reaction in the vessel wall is less pronounced than with cyanoacrylates and there is no inflammatory reaction in the surrounding interstitium [

25].

Although endovascular treatment of AVMs with embolic agents, both adhesive and non-adhesive, is nowadays largely used as a standard of care in neurovascular interventions [

26], the same treatment cannot be applied for cerebral aneurysms as the long polymerization time of these embolic agents leads to high risk of uncontrolled migration and thus damage of healthy vessels and tissues. None of the studies available in the literature investigated the use of the mixture Glubran® 2 (n-butyl-cyanoacrylate + metacryloxysulfolane NBCA-MS) associated with Ethanol and Lipiodol as a new embolic agent for aneurysm endovascular treatment. The aim of this study was to investigate the degree of penetration, permanence of occlusion and vascular changes induced by a modified mixture of n-butyl cyanoacrylate (Glubran 2®), Ethanol and Lipidol® mixture (GEL) in experimental aneurysms induced in swine. The primary endpoint was to assess the efficacy and safety of the embolization treatment with the G.E.L. The secondary endpoint was to characterize, by histopathological analysis, the tissue response to this mixture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental design

In this preclinical study, tissue samples from 9 healthy swine, six females and three males, weighing 50–70 kg were used. The experiments were performed at the Biotechnologies Research Centre of A.O.R.N. “Antonio Cardarelli” Hospital. Permission to conduct this experimental study was granted before starting the study by the Institutional Committee on Research-Animal Care and the Italian Ministry of Health (Authorization n. 23654/19), in according with Italian Laws DL.gs 26/2014 and Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. For each swine, two aneurysmal defects were created for a total of 18. Before surgery each animal was administered zoletil 50/50 + propofol + ketamine + sevorane (0.5ml kg +6mg/kg+10mg/kg + sev.2%) and butorphanol as pre-operative analgesia. General anesthesia was induced with isoflurane gas via tracheal intubation. Cardiac and pulmonary data were monitored throughout the procedures.

2.2. Creation of Aneurysm

Each swine underwent surgical exposure of the left and right carotid arteries and jugular veins to form two aneurysms. To generate an aneurysm model with carotid artery interruption a 3 cm section of the jugular vein was removed first. The resected vein was then sutured to the ipsilateral carotid artery. Every swine underwent surgical creation of the aneurysms, two aneurysms for each swine for a total of 18 aneurysms. Subsequently, femoral access was performed to place a carrier catheter in one of the two carotid axes with the use of a double microcatheter. The first was used for the injection of the GEL mixture while the second microcatheter had a distal balloon that allowed the blocking of the flow at the aneurysm sac, thus preventing the uncontrolled migration of embolizing material from the sac itself. The animals were placed in anti-aggregative therapy to avoid spontaneous thrombosis of the created bag. In the first three days it was administered Tramadol 10 mg/kg orally in the drinking water and antibiotic therapy was continued for 7 days. Animals were checked daily for signs of adverse effects.

2.3. Gel used for embolization

For embolization was used a GEL mixture composed by Glubran 2 NBCA + MS (GEM Srl; Viareggio (LU) Italy) was withdrawn through a 21-gauge needle and mixed with contrast agent Lipiodol (iodinated ethyl esters of the fatty-Guerbet) and ethanol (99.9 %, FUSO Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd.). Glubran®2 was mixed with ethanol and Lipiodol in the ratio 2: 0.5: 1 (57% Glubran®2, 14% EtOH, 28%Lipiodol). This ratio was used because it yields a mixture that polymerizes in longer times allowing a controlled filling of the entire aneurysm. It was prepared by first mixing ethanol and Lipiodol in a vail and was shaken by hand for 1 minute and then adding the NBCA+MS and shaking it all for three minutes. The amount of the injected GEL mixture was variable to the size of the created aneurysm. We measured the volume of the aneurysm and estimated the total volume of GEL required.

2.4. Endovascular procedure

In each swine, packing of the aneurysm was attempted 3-4 hours after the creation of the aneurysms. The embolization procedure was performed on the swine at an angiography facility (GE, USA). Activation clotting time of 200 s or more (normal range <120 s) was maintained by intravenous infusion of heparin (50 U/kg) before the surgery and the embolization. Digital subtraction angiography, test injection, and the interventional procedure were conducted after adjusting the tube angle for optimal visualization of the lateral aspect of the aneurysm. Carotid arteriography was conducted via a guiding catheter (Envoy 5Fr or 6Fr, Cerenovous, USA) placed in the target vessel within which a 0,017” microcatheter (SL10, Stryker, USA) was advanced to the aneurysm neck and inside the sac, using a 0.014-inch micro-guide wire (Transend EX; Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts). Subsequently, a 4,35 Fr Remodeling Balloon catheter (Copernic, Balt, France) was advanced into the carotid artery and inflated at the neck of the aneurysm to a pressure of 6 atmospheres. Because the mean diameter of the carotid arteries was 5.2 mm (range 4.4–5.9 mm), we used a 6 mm balloon catheter. The gluing microcatheter is then purged with saline, to clear any residue of contrast material, and primed with 5% glucose with a volume to match the catheter dead space (approximately 1.2 ml) to prevent polymerization of NBCA in the microcatheter. After a new control of activated clotting time of >200 seconds, the carotid artery was occluded by balloon inflation. The mixture was slowly injected in small increments from the distal end of the aneurysm sac by use of a 3-ml syringe to avoid regurgitation in the microcatheter. After the initial injection of approximately 1-1.3 ml GEL, a test injection was performed. The mixture was slowly injected through the microcatheter under fluoroscopic control. When packing was achieved, the balloon catheter was deflated 5 minutes later, and digital angiography was performed to verify the occlusion rate. When packing was insufficient, an additional injection was attempted using the same mixture under balloon occlusion to reduce the aneurysmal open space. By use of this approach, maximum of two injections were required to pack the aneurysms.

2.5. Sampling of aneurysms

Immediately after excision surgery of the aneurysm and at 7-30-90 days post-surgery, two swine were sacrificed by anesthetic overdose (isoflurane) and submitted to surgery to remove the experimentally induced aneurysms. The experimentally induced defects were excised in toto and immediately placed into 10% buffered formalin fixative.

2.6. Histopathology

The formalin-fixed experimentally induced aneurysms were routinely processed for paraffin embedding. Five-μm serial sections were dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated in a graded alcohol series, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H-E) for routine examination, Masson’s trichrome stain to evaluate connective tissue, Perls’ Prussian blue stain to detect hemosiderin deposits, and picrosirius red stain to determine the collagen types of contents. Slides were examined by two pathologists (N.F. and A.P.) in a blinded fashion.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry tissue sections were mounted on treated glass slides (Superfrost Plus; Menzel-Glaser, Germany). Sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through graded alcohols. Heat-induced epitope retrieval with citrate buffer pH 6.0 was performed in a microwave oven. Immunohistochemical labeling was carried out manually with the Sequenza slide rack and cover-plate system (Shandon, Runcorn, UK). Non-specific peroxidase activity was blocked with Bloxall blocking solution (SP-6000; Vector Laboratories, CA, USA), and non-specific antigen binding was blocked with UltraVision Protein Block (TA-060-PBQ; Thermo Scientific, Cheshire, UK). A panel of primary antibodies was applied to serial sections and incubated overnight at 4°C. Anti-Iba1 rabbit polyclonal antobody (Wako, Neuss, Germany; diluted 1:300), anti-CD3 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark; diluted 1:200), and anti-Cd79a mouse monoclonal antibody (Exbio, Praha, Czech Rep.; diluted 1:100) were used for macrophages, T-lymphocytes, and B-lymphocyte, respectivley. Antibody binding was detected by the Biotinylated horse anti-Mouse/Rabbit IgG antibody (H+L) R.T.U. (Vectors Laboratories, CA, USA), the Streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase kit (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA) and the 3,30-diamino-benzidine as chromogen (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA) as indicated by manufacturer’s instructions. Stained slides were subsequently counterstained in haematoxylin followed by dehydration in graded alcohols and cleared with xylene. Sections were mounted in DPX (08600E; Surgipath Europe, UK). Substitution of the primary antibody with an unrelated matched primary antibody was used to provide a negative control. Serial sections of a rat lymph node were used as a positive control.

2.8. Morphometrical studies

The aneurysm wall was submitted to a morphometric investigation. Bright-field images were acquired at x40 magnification with a Leica Microsystem DFC490 digital camera mounted on Leica DMR microscope (Wetzlar, Germany). Counting was performed using a semiautomatic analysis system (LASV 4.3, Leica) on six 15,000 μm2 random fields of three different areas of the aneurysm wall. These sampled areas were used to evaluate the thickness of the aneurysm wall, the thickness of the connective tissue production, the new blood vessel count, and the composition of cell populations involved in the inflammatory reaction.

2.9 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS Advanced Statistics 21.0 (SPSS Inc.,Chicago, IL, USA). ANOVA test was used to compare the different parameters observed at different time. Post hoc analysis was made by Bonferroni Test. Statistical significance was based on a 5% (alpha = 0.05) significance level.

3. Results

All the scheduled interventions have been completed and all the swine underwent aneurysm creation and embolization. A total of 18 aneurysms have been considered. In 77.78% of cases (14/18) aneurysms have been successfully and completely fulfilled by the mixture without immediate or delayed complications. In 11.11% of cases (2/18) aneurysms have been completely fulfilled but after balloon deflation embolic complication occurred as the mixture migrated in the parent artery. In 5.56% of cases (1/18) the rupture of the balloon catheter occurred with consequent mixture migration in healthy territory. In 5.56% of cases (1/18) aneurysm has not been treated because the swine was suppressed before the treatment. Looking at the swine the fate is the following: in 66.67% of cases (6/9) swine survived after the procedure and underwent scheduled controls and sacrifice according to the protocol. In 11.11% of cases (1/9) swine were successfully embolized but died 24 hours. after the procedural probably due to ischemic complications. In 22.22% of cases (2/9) swine were suppressed immediately after the procedure due to embolic or hemorrhagic complications.

3.1. Endovascular procedure

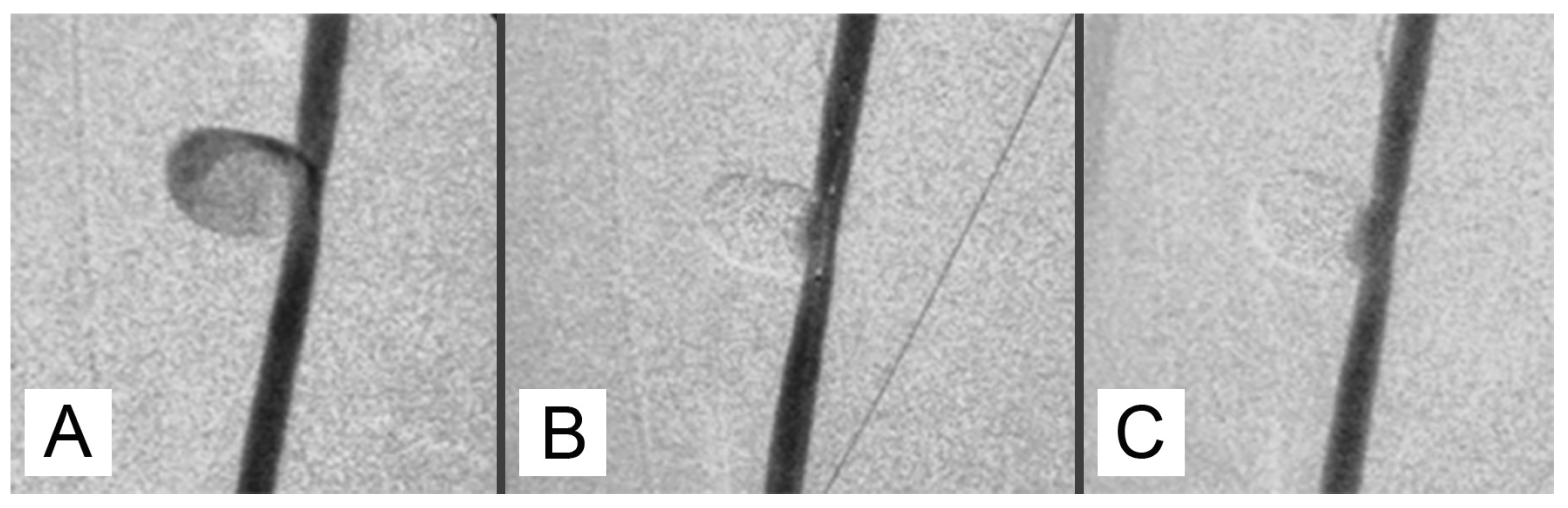

Upon injection, GEL first took the appearance of a thread-like structure before expanding into a huge, circular formation that occupied the aneurysm's whole lumen. Following the GEL injection, it was possible to withdraw the balloon catheter and the microcatheter with ease. This allowed for more packing of the aneurysm by moving the microcatheter forward and injecting the mixture again while inflating the balloon catheter.

One possible method of cleaning a microcatheter lumen is to flush it with lipiodol. Nevertheless, it was occasionally discovered that GEL remained in the hub section of a microcatheter, making guidewire insertion challenging when the microcatheter was reinserted using a guidewire. Another microcatheter was needed in this case. In 15 of the 18 aneurysms, post-packing angiography showed nearly full aneurysm packing (

Figure 1).

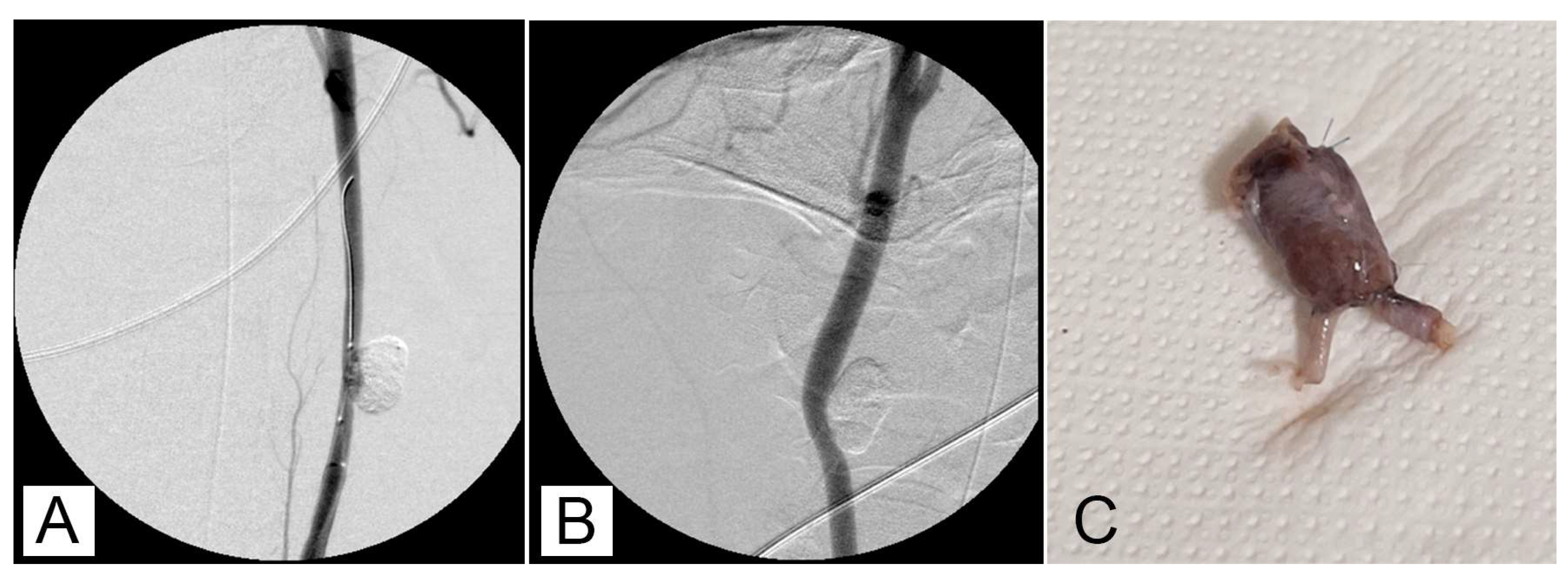

After 30 minutes of packaging, there was no migration or leakage of GEL. Post-procedure angiographic controls showed a stable occlusion of all the aneurysms with no signs of recurrence (

Figure 2A,B)

3.2. Macroscopic study

The different subjects did not exhibit symptoms related to a painful state. During the surgery for removing the experimentally induced defects, no alterations due to an ongoing inflammatory process were evidenced (

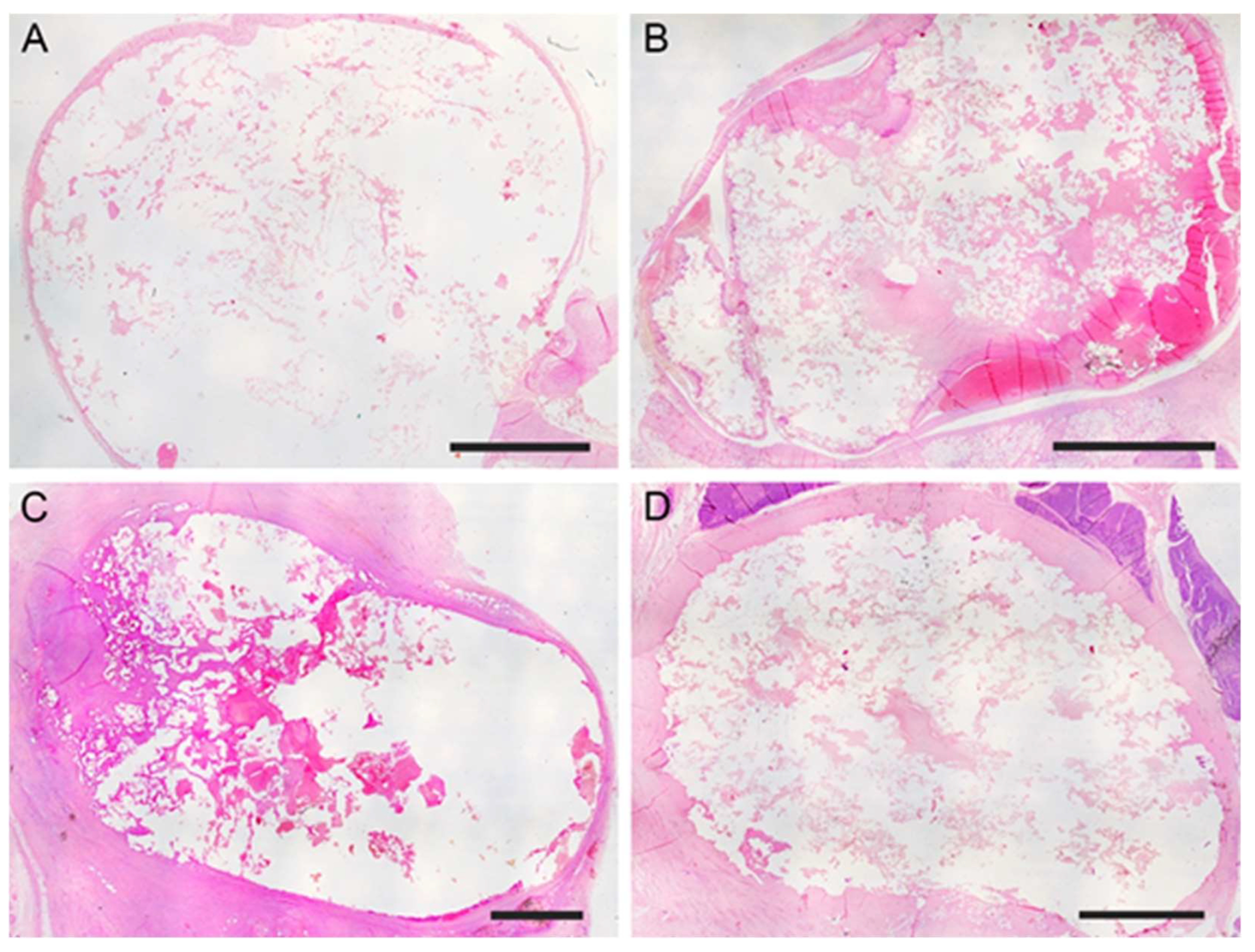

Figure 2C) The mean long × short diameters of the created aneurysm ranged from 5 to 30 mm (mean diameter 12.4 mm ± 6.2 mm). The mean neck width ranged from 3 to 10 mm. The dome-to-neck ratio (long diameter/neck width) ranged from 1 to 3. A complete occlusion was observed starting from time 0

(Figure 3A) and remained evident at 7

(Figure 3B), 30 (

Figure 3C), and 90 (

Figure 3D) days post-surgery. The aneurysm occlusion was due to a mixture of the embolic agent and thrombotic materials. The distribution of the embolic material inside the embolic cast was homogeneous and the embolizing material adhered to the aneurysm wall. There was no evidence of recanalization of the embolic cast in samples examined, particularly after 7-, 30-, and 90-days post-surgery.

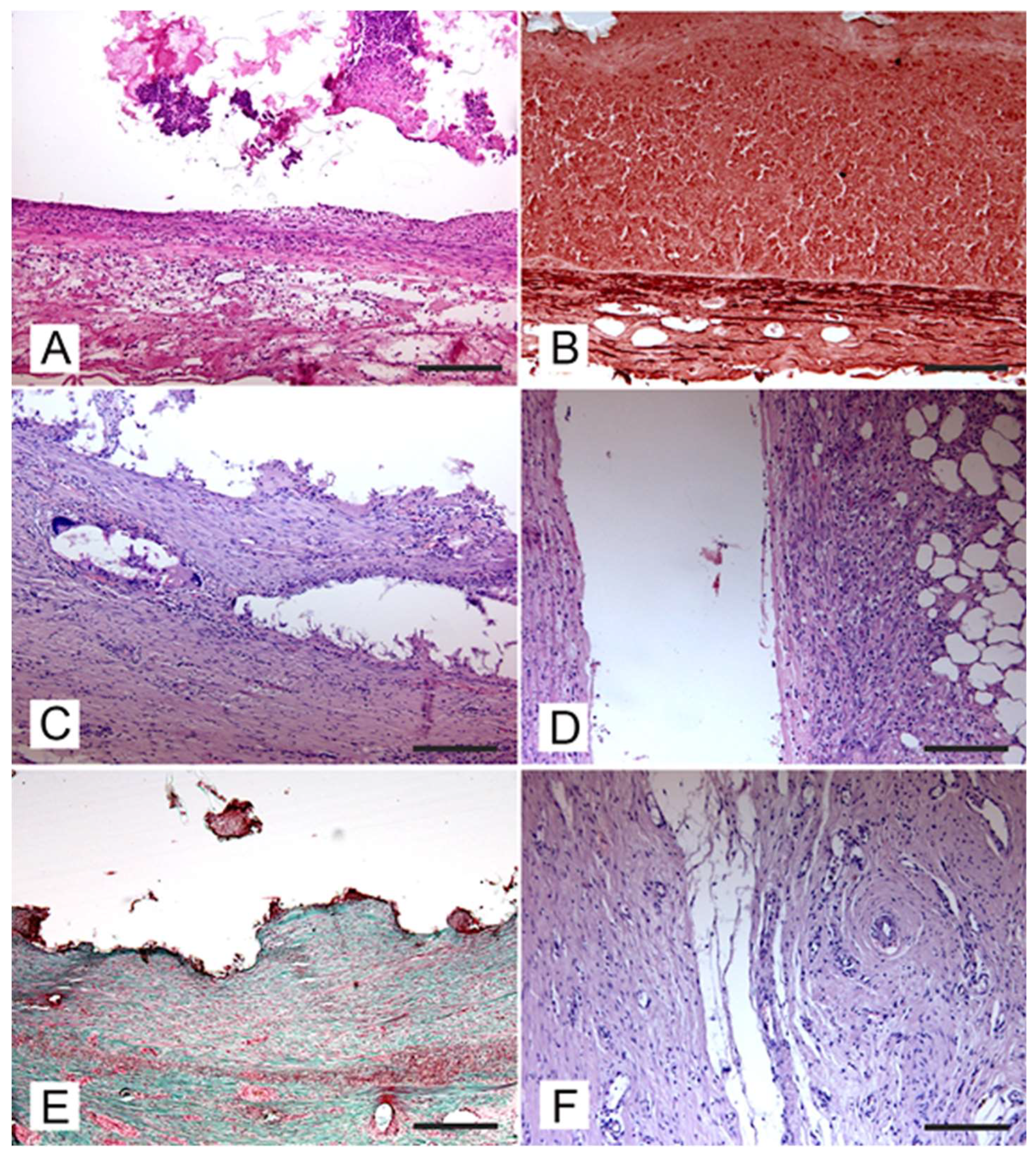

3.3. Vascular changes

Vascular integrity of the aneurysm wall was observed in all experimentally induced defects and no evidence of perivascular extravasation of embolic material was detected in any specimens. An acute inflammatory reaction characterized by the presence of hemorrhages was detected in all samples resected after a few hours (t0) and 7 days post-surgery

(Figure 4A

). In samples collected after 7 days post-surgery, angionecrosis demonstrated by alteration of elastic fibers was also observed

(Figure 4B

). At 30 days post-surgery, the aneurysm wall was slightly thickened due to the proliferation of a poorly differentiated connective tissue and presence of chronic vascular inflammation

(Figure 4C

). In the aneurysm wall scattered foreign body reactions at the periphery of embolizing material residues and characterized by the presence of foreign body giant cells were also detected

(Figure 4D

). At the periphery of the aneurysm wall there was edema and host tissue showed a reduced inflammatory infiltration

(Figure 4E

). After 90 days post-surgery the aneurysm wall was thickened and consisted of a well-differentiated connective tissue

(Figure 4F

). Pigment deposits of hemoglobin origin (both hemosiderin and hematin) were also observed.

3.4. Perivascular changes

In samples collected 7 days post-surgery a limited perivascular oedema was observed. After 30 days post-surgery a marked reduction of the perivascular oedema was evident, scattered perivascular inflammatory infiltrates constituted by macrophages and small lymphocytes were also present. No perivascular changes were detected in samples collected 90 days post-surgery.

3.5. Immunohistochemical studies

Immunohistochemical studies revealed the presence of a reduced number of T- and B- lymphocytes in the inflammatory infiltrates observed in the aneurysm wall after 7- and 30-days post-surgery. Many macrophages were detected in chronic vascular inflammatory infiltrates detected in the aneurysm wall after 30 days post-surgery. The number of macrophages in the aneurysm wall was drastically reduced in samples collected 90 days post-surgery.

3.6. Morphometric analysis

Morphometric analysis performed to determine the thickness of the aneurysm wall at different time from embolization revealed that at 7 days post embolization, the aneurysm walls were only slightly increased due to the acute inflammatory reaction to the mixture deposit without significant differences (65μm ± 9 μm at t0 vs 120 μm ± 10 μm at t7). After 30 days post embolization there was a significant increase in the aneurysm wall thickening (120 μm ± 10 μm al t7 vs 366 μm ± 83 μm at t30; p<0.001) due to the connective tissue proliferation more evident 90 days after embolization (366 μm ± 83 μm al t30 vs 701 μm ± 261 μm at t90; p<0.001).

4. Discussion

This is the first experimental study to address feasibility, efficacy, and tissue reaction after embolization with a mixture of n-butyl-cyanoacrylate (Glubran 2®), Ethanol and Lipidol® of aneurysms experimentally induced in swine. Endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms has become an alternative to conventional neurosurgical clipping [

27]. Guglielmi Detachable Coils (GDC) offer safe and effective endovascular treatment for cerebral aneurysms [

28], but face limitations in dense packing and control due to their ineffectiveness in wide-necked or large aneurysms, making them less effective [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. One potential alternative for the treatment of certain cerebral aneurysms is the use of liquid embolic agents [

34,

35]. However, these treatment approaches have not gained widespread acceptance due to inherent technical constraints. One significant drawback has been the inability to adjust or retrieve the liquid embolic agent once delivered into the aneurysm sac [

36]. Several clinical and experimental techniques, including the placement of metallic stents, balloon inflation across the aneurysm's neck, and intra-aneurysmal flow control with proximal balloon protection, have been tried to reduce the liquid embolic agent's distal migration [

34,

37]. Kawai et al. successfully packed a narrow-neck carotid artery aneurysm with NLE, but not wide-neck aneurysms due to NLE migration risk [

15]. The study by Tanaka et al. [

38] and Hama et al. [

39] represents a step forward, as balloon inflation at the aneurysm site was effectively used to execute NLE packing of aneurysms with a neck width of ≥6.3 mm and a dome-to-neck ratio of <2.0. Balloon-assisted injection of liquid embolic agents and balloon- or stent-assisted coiling (BAC and SAC) use a two-catheter system, requiring glue/dimethyl sulfoxide-compatible catheters and balloons, and embolizing the aneurysm sac with liquid agents. Similar occlusion rates were seen at in the CAMEO trial [

40], which examined the treatment of 100 aneurysms using the Onyx liquid embolic system. Using this system a 79% complete occlusion rate at 12 months were obtained, but the rate of major adverse events (26.8%) was remarkable. This procedure is still used in other nations, but it did not catch on in the United States due to the high rate of complications.

In this study, at seven days after the embolization, a mild acute vascular reaction was evident in the aneurysm wall, probably related with the polymerization of cyanoacrylic glue present in the mixture, without involvement of host tissues at the periphery of the experimentally induced lesion. This acute reaction was followed by a chronic inflammation which induced a thickening of aneurysm wall due to proliferation of connective tissue still confined within the aneurysm wall. The embolization procedure induced vascular changes followed by a complete and stable occlusion of the aneurysms. Our experimental study demonstrated that the presence of the occlusion remained stable up to 90 days after surgery, without recanalization phenomena.

The 2:0,5:1 ratios of GEL components seemed to offer a good compromise between polymerization time, balloon resistance and catheter patency. As we know Glubran + Lipiodol mixture is not appropriate for packing of wide-neck aneurysms [

41] because it forms small oily droplets and adheres firmly to the microcatheter and balloon catheter [

42], which could prevent its removal from the vessel. GEL, on the other hand, produced a single huge solid droplet, which made it look like a suitable material for aneurysm packing [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. GEL was less adherent to the balloon catheter and microcatheter than G+L was. This allowed the microcatheter to be advanced further into the aneurysm and GEL to be reinjected for more packing via the microcatheter. The GEL's minimal stickiness made it simple to remove both catheters. In two of the eighteen aneurysms, we saw resistance to the microcatheter during retrieval, despite the fact that the microcatheter did not adhere to the adhesive cast.

The GEL mixture in our study exhibited outstanding visibility under fluoroscopy. To prevent leakage into the parent artery and distal migration of the adhesive, liquid embolic agents should be employed under high-quality, subtracted, real-time fluoroscopic guidance in addition to having optimal visibility. During the aneurysm packing, continuous injection of GEL was necessary to prevent blood regurgitation. Ethanol accelerates polymerization along the GEL mixture-blood interface, potentially reducing unwanted NBCA adhesion to the catheter by binding to anions in the blood [

30]. Since the hemodynamics of a human aneurysm differ from those of the surgically created side-wall aneurysm model in pigs, direct application of our findings to clinical research may be limited. Furthermore, following very long-term follow-up, the embolic effect's stability and safety must be verified. Taking everything to account, glue embolization of aneurysms is technically feasible with neck protection of the flow with a balloon.

In conclusion, the GEL mixture may be useful for embolizing arteriovenous malformations, controlling acute bleeding, and isolating aneurysms in future clinical applications, requiring balloon occlusion and selective catheterization. GEL could also shorten the treatment time according to its very short polymerization time and could be used in combination with detachable coils for aneurysm packing. In short, despite certain restrictions, packing for aneurysms using GEL is safe and feasible because it becomes more solid and has a higher occlusive ability than a simple Glubran and lipiodol mixture, with minimal adhesion to the microcatheter and embolic complications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. (Massimo Muto), G.L., M.M. (Mario Muto); methodology, M.M. (Massimo Muto), M.M. (Mario Muto), A.P.; validation, G.L., M.M. (Mario Muto), A.P.; formal analysis, F.C., A.P., N.F., ; investigation, F.G., G.G., E.D.M., N.F.; data curation, A.P., N.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. (Massimo Muto), A.D.D., N.F.; writing—review and editing, V.A., M.M. (Mario Muto), A.P.; project administration, M.M. (Mario Muto), A.P.; funding acquisition, M.M. (Mario Muto). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by GEM Srl, which covered all costs for animals, necessary materials, and analysis.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Committee on Research-Animal Care and the Italian Ministry of Health (Authorization n. 23654/19), in according with Italian Laws DL.gs 26/2014 and Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Günther, R., Schubert, U., Bohl, J., Georgi, M., Marberger, M. Transcatheter embolization of the kidney with butyl-2-cyanoacrylate: experimental and clinical results. Cardiovasc Radiol 1978, 1(2):101-8. doi: 10.1007/BF02552003. PMID: 570455. [CrossRef]

- Lieber, B.B., Wakhloo, A.K., Siekmann, R., Gounis, M.J. Acute and chronic swine rete arteriovenous malformation models: effect of ethiodol and glacial acetic acid on penetration, dispersion, and injection force of N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005, 26(7):1707-14. PMID: 16091519; PMCID: PMC7975171.

- Ali, A., Ahle, M., Björnsson, B., Sandström, P. Portal vein embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate glue is superior to other materials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2021, 31(8):5464-5478. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07685-w. Epub 2021 Jan 26. PMID: 33501598.-021-03014-w. Epub 2021 Dec 14. PMID: 34907454; PMCID: PMC8940786. [CrossRef]

- Seewald, S., Sriram, P.V., Naga, M., Fennerty, M.B., Boyer, J., Oberti, F., Soehendra, N. Cyanoacrylate glue in gastric variceal bleeding. Endoscopy 2002, 34(11):926-32. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35312. PMID: 12430080. [CrossRef]

- Favard, N., Moulin, M., Fauque, P., Bertaut, A., Favelier, S., Estivalet, L., Michel, F., Cormier, L., Sagot, P., Loffroy, R. Comparison of three different embolic materials for varicocele embolization: retrospective study of tolerance, radiation and recurrence rate. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2015, 5(6):806-14. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.10.10. PMID: 26807362; PMCID: PMC4700243. [CrossRef]

- Bal-Ozturk, A., Cecen, B., Avci-Adali, M., Topkaya, S.N., Alarcin, E., Yasayan, G., Ethan, Y.C., Bulkurcuoglu, B., Akpek, A., Avci, H., Shi, K., Shin, S.R., Hassan, S. Tissue Adhesives: From Research to Clinical Translation. Nano Today 2021, 36:101049. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2020.101049. Epub 2020 Dec 20. PMID: 33425002; PMCID: PMC7793024. [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, M., Barbara, C., Simonetti, L., Giardino, R., Aldini, N.N., Fini, M., Martini, L., Masetti, L., Joechler, M., Roncaroli, F. Glubran 2: a new acrylic glue for neuroradiological endovascular use. Experimental study on animals. Interv Neuroradiol 2002, 30;8(3):245-50. doi: 10.1177/159101990200800304. Epub 2004 Oct 20. PMID: 20594482; PMCID: PMC3572477. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y., Morishita, H., Sato, Y. et al. Guidelines for the use of NBCA in vascular embolization devised by the Committee of Practice Guidelines of the Japanese Society of Interventional Radiology (CGJSIR), 2012 edition. Jpn J Radiol 2014, 32, 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-014-0328-7. [CrossRef]

- Comby, P. O., Guillen, K., Chevallier, O., Lenfant, M., Pellegrinelli, J., Falvo, N., Midulla, M., Loffroy, R. Endovascular Use of Cyanoacrylate-Lipiodol Mixture for Peripheral Embolization: Properties, Techniques, Pitfalls, and Applications. J Clin Med 2021, 10(19), 4320. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194320. [CrossRef]

- Cognard, C., Weill, A., Tovi, M., Castaings, L., Rey, A., Moret, J. Treatment of distal aneurysms of the cerebellar arteries by intraaneurysmal injection of glue. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999, 20:780 –784.

- Li, Y.J.; Barthes-Biesel, D.; Salsac, A.V. Polymerization kinetics of n-butyl cyanoacrylate glues used for vascular embolization. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2017, 69, 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.01.003. [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.M.H., Chen, C.C., Lirng, J.F., Chen, S.S., Lee, L.S., Chang, T. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate for embolization of carotid aneurysm. Neuroradiology 1994, 36:144–147.

- Kinugasa, K., Mandai, S., Tsuchida, S., Sugiu, K., Kamata, I., Tokunaga, K., Ohmoto, T. and Taguchi, K. Cellulose acetate polymer thrombosis for the emergency treatment of aneurysms: Angiographic findings, clinical experience, and histopathological study. Neurosurgery 1994, 34(4), pp.694-701.

- Nishi, S., Taki, W., Nakahara, I., Yamashita, K., Sadatoh, A., Kikuchi, H., Hondo, H., Matsumoto, K., Iwata, H. and Shimada, Y. Embolization of cerebral aneurysms with a liquid embolus, EVAL mixture: report of three cases. Acta neurochirurgica 1996, 138, pp.294-300. [CrossRef]

- Kawai, N.; Sato, M.; Minamiguchi, H.; Ikoma, A.; Sanda, H.; Nakata, K.; Tanaka, F.; Nakai, M.; Sonomura, T. Basic study of a mixture of N-butyl cyanoacrylate, ethanol, and lipiodol as a new embolic material. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012, 23, 1516–1521. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, F.; Kawai, N.; Sato, M.; Minamiguchi, H.; Nakai, M.; Nakata, K.; Sanda, H.; Sonomura, T.; Matuzaki, I.; Murata, S. Effect of transcatheter arterial embolization with a mixture of N-butyl cyanoacrylate, lipiodol, and ethanol on the vascular wall: Macroscopic and microscopic studies. Jpn J Radiol 2015, 33, 404–409. PMID: 25963344. [CrossRef]

- Jahan, R.; Murayama, Y.; Gobin, Y.P.; Duckwiler, G.R.; Vinters, H.V.; Viñuela, F. Embolization of Arteriovenous Malformations with Onyx: Clinicopathological Experience in 23 Patients. Neurosurgery 2001, 48, 984–995.

- Takao, H., Murayama, Y., Yuki, I., Ishibashi, T., Ebara, M., Irie, K., Yoshioka, H., Mori, Y., Vinuela, F. and Abe, T. Endovascular treatment of experimental aneurysms using a combination of thermoreversible gelation polymer and protection devices: feasibility study. Neurosurgery 2009, 65(3), pp.601-609. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000350929.31743.C2. PMID: 19687707. [CrossRef]

- Taki, W.; Yonekawa, Y.; Iwata, H.; Uno, A.; Yamashita, K.; Amemiya, H. A New Liquid Material for Embolization of Arteriovenous Malformations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1990, 11, 163–168. PMID: 2105599; PMCID: PMC8332490.

- Hu, J.; Albadawi, H.; Chong, B.W.; Deipolyi, A.R.; Sheth, R.A.; Khademhosseini, A.; Oklu, R. Advances in Biomaterials and Technologies for Vascular Embolization. Adv Mater 2019, 31, 1901071. PMID: 31168915; PMCID: PMC7014563. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, A. Ethylene vinyl alcohol co-polymer as a high-performance membrane: An EVOH membrane with excellent biocompatibility. In High-Performance Membrane Dialyzers 2011, 173, pp. 164–171. doi: 10.1159/000329056. Epub 2011 Aug 8. PMID: 21865789. [CrossRef]

- Chaloupka, J.C., Huddle, D.C., Alderman, J., Fink, S., Hammond, R., Vinters, H.V. A reexamination of the angiotoxicity of superselective injection of DMSO in the swine rete embolization model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999, 20(3):401-10. PMID: 10219404; PMCID: PMC7056064.

- Klisch, J., Yin, L., Requejo, F., Eissner, B., Scheufler, K.M., Kubalek, R., Buechner, M., Pagenstecher, A., Nagursky, H., Schumacher, M. Liquid 2-poly-hydroxyethyl-methacrylate embolization of experimental arteriovenous malformations: feasibility study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002, 23(3):422-9. PMID: 11901012; PMCID: PMC7975285.

- Bakar, B., Kose, E.A., Sonal, S., Alhan, A., Kilinc, K., Keskil, I.S. Evaluation of the neurotoxicity of DMSO infused into the carotid artery of rat. Injury 2012, 43(3):315-22. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.08.021. Epub 2011 Sep 9. PMID: 21907339. [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, M.E., Wolak, D.J., Kumar, N.N., Brunette, E., Brunnquell, C.L., Hannocks, M.J., Abbott, N.J., Meyerand, M.E., Sorokin, L., Stanimirovic, D.B., Thorne, R.G. Intrathecal antibody distribution in the rat brain: surface diffusion, perivascular transport and osmotic enhancement of delivery. J Physiol 2018, 1;596(3):445-475. doi: 10.1113/JP275105. Epub 2017 Dec 18. PMID: 29023798; PMCID: PMC5792566. [CrossRef]

- Duffner, F., Ritz, R., Bornemann, A., Freudenstein, D., Wiendl, H., Siekmann, R. Combined therapy of cerebral arteriovenous malformations: histological differences between a non-adhesive liquid embolic agent and n-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA). Clin Neuropathol 2002, 21(1):13-7. PMID: 11846039.

- Higashida, R.T., Lahue, B.J., Torbey, M.T., Hopkins, L.N., Leip, E., Hanley, D.F. Treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a nationwide assessment of effectiveness. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007, 28(1):146-51. PMID: 17213445; PMCID: PMC8134123.

- Kuether, T.A., Nesbit, G.M., Barnwell, S.L. Clinical and angiographic outcomes, with treatment data, for patients with cerebral aneurysms treated with Guglielmi detachable coils: a single-center experience. Neurosurgery 1998, 43(5):1016-1025. DOI: 10.1097/00006123-199811000-00007. PMID: 9802844. [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A., Killer, M., Bavinzski, G., Richling, B. Clinical and angiographic results of endosaccular coiling treatment of giant and very large intracranial aneurysms: a 7-year, single-center experience. Neurosurgery 1999, 45(4):793-803; discussion 803-4. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199910000-00013. PMID: 10515473. [CrossRef]

- Sluzewski, M., Menovsky, T., van Rooij, W.J., Wijnalda, D. Coiling of very large or giant cerebral aneurysms: long-term clinical and serial angiographic results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003, 24(2):257-62. PMID: 12591644; PMCID: PMC7974128.

- Fernandez Zubillaga, A., Guglielmi, G., Viñuela, F., Duckwiler, G.R. Endovascular occlusion of intracranial aneurysms with electrically detachable coils: correlation of aneurysm neck size and treatment results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994, 15(5):815-20. PMID: 8059647; PMCID: PMC8332188.

- Malisch, T.W., Guglielmi, G., Viñuela, F., Duckwiler, G., Gobin, Y.P., Martin, N.A., Frazee, J.G. Intracranial aneurysms treated with the Guglielmi detachable coil: midterm clinical results in a consecutive series of 100 patients. J Neurosurg 1997, 87(2):176-83. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.2.0176. Erratum in: J Neurosurg 1998, 88(2):359. PMID: 9254079. [CrossRef]

- Debrun, G.M., Aletich, V.A., Kehrli, P., Misra, M., Ausman, J.I., Charbel, F. Selection of cerebral aneurysms for treatment using Guglielmi detachable coils: the preliminary University of Illinois at Chicago experience. Neurosurgery 1998, 43(6):1281-95. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199812000-00011. PMID: 9848841. [CrossRef]

- Murayama, Y., Viñuela, F., Tateshima, S., Viñuela, F. Jr., Akiba, Y. Endovascular treatment of experimental aneurysms by use of a combination of liquid embolic agents and protective devices. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000, 21(9):1726-35. PMID: 11039357; PMCID: PMC8174846.

- Macdonald, R.L., Mojtahedi, S., Johns, L., Kowalczuk, A. Randomized comparison of Guglielmi detachable coils and cellulose acetate polymer for treatment of aneurysms in dogs. Stroke 1998, 29(2):478-85. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.478. PMID: 9472893. [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.C., Kim, K.S., Lim, S.M., Shi, H.B., Choi, C.G., Lee, H.K., Seo, D.M. Technical feasibility of embolizing aneurysms with glue (N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate): experimental study in rabbits. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003, 24(8):1532-9. PMID: 13679265; PMCID: PMC7973981.

- Fries, F., Tomori, T., Schulz-Schaeffer, W. J., Jones, J., Yilmaz, U., Kettner, M., Simgen, A., Reith, W., Mühl-Benninghaus, R. Treatment of experimental aneurysms with a GPX embolic agent prototype: preliminary angiographic and histological results. J Neurointerv Surg 2022, 14(3), 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017308. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka F, Kawai N, Sato M, Minamiguchi H, Nakai M, Nakata K, Sanda H, Sonomura T. Balloon-assisted packing of wide-neck aneurysms with a mixture of n-butyl cyanoacrylate, Lipiodol, and ethanol: an experimental study. Jpn J Radiol 2015, 33(8):517-22. doi: 10.1007/s11604-015-0451-0. Epub 2015 Jul 4. PMID: 26142254. [CrossRef]

- Hama, M., Sonomura, T., Ikoma, A., Koike, M., Kamisako, A., Tanaka, R., Koyama, T., Sato, H., Tanaka, F., Ueda, S., Okuhira, R., Warigaya, K., Murata, S., Nakai, M. Balloon-Assisted Embolization of Wide-Neck Aneurysms Using a Mixture of n-Butyl Cyanoacrylate, Lipiodol, and Ethanol in Swine: A Comparison of Four n-Butyl Cyanoacrylate Concentrations. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2020, 43(10):1540-1547. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02567-6. Epub 2020 Jul 16. PMID: 32676961. [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, A.J., Cekirge, S., Saatci, I., Gál, G. Cerebral Aneurysm Multicenter European Onyx (CAMEO) trial: results of a prospective observational study in 20 European centers. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004, 25:39–51.

- Suh, D.C., Seo, D.M., Yun, T.J., Kim, K.S., Park, S.S., Noh, H.N., Kim, J.K., Kim, S.T., Choi, C.G., Lee, H.K., Song, H.Y. Evaluation of characteristics of cyanoacrylate-lipiodol mixtures injected in the different flow layers. J Korean Radiol Soc 1997, 37(6), pp.969-973. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S., Suh, D.C., Park, S.S., Bae, S.J., Kim, D.E., Kwon, J.S., Kim, K.S., Kim, D.H., Choi, C.G., Lee, H.K. Reaction difference of Glue-Lipiodol mixture according to the different lot number. J Korean Radiol Soc 1998, 39:277–281.

- Lord, J., Britton, H., Spain, S.G., Lewis, A.L. Advancements in the development on new liquid embolic agents for use in therapeutic embolisation. J Mater Chem B 2020 23;8(36):8207-8218. doi: 10.1039/d0tb01576h. PMID: 32813005. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).